#but also in the uk because social services is underfunded

Note

How is telling people that we need to get rid of adoption insane? Are you saying that all babies should not be wanted?

is there like one bad faith person who just trawls my blog looking to read everything i say in the most unhinged bad faith way possible like what even is this. are you joking. are you insane. genuinely what is wrong with you do you think i believe that we need to make sure as many babies are given up for adoption is possible. do you think i came online to say that????? its the dual leaps of the mind required to first interpret my statement as meaning that and then to secondly not take one second to be like wow am i sure thats what this person is saying because that seems insane. i feel like you need to get an adult to supervise your internet time

#ask#anon#why is it ALWAYS something with you people like come onnnn this is just stupid#how is that even a possible takeaway from me saying surrogacy is fucking abysmal & a human rights issue and should be illegal worldwide#if you cant 'obtain' a child in a non-human-rights-violating way u shouldnt have a child#if u need me to explain it to u then um. stating that no one should ever be raised by anyone who isnt their biological parents is bizarre#the majority of ppl arent in care bc they werent 'wanted' but bc their parents like died or couldnt look after them or were abusing them#and for what its worth the american for profit adoption system is like extremely not normal#there should never be an INCENTIVE for removing kids from their homes#but also in the uk because social services is underfunded#theres an ongoing scandal where several children have died horribly bc they WERENT removed from homes where they were in danger#and even in the most perfect world ever there will STILL be children who end up without parents#so i dont even know what ur getting at like if every kid was 'wanted' there wouldnt be any more adoption...#this is literally a belief ive never come across before im totally baffled#i didnt think there was anyone in the world who believed that adoption should just. be abolished#like humans have been adopting children they didnt give birth to for as long as weve existed..#QUESTION MARK??

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scobie: Princess Kate’s Early Years work is ineffectual because of her ‘limitations’

February 02, 2023

By Kaiser

It’s been Keen Early Years Week, where the Princess of Wales has launched yet another awareness-raising campaign centered on Kate going around, telling people that the early years are important. Shaping Us is no different than the Five Big Questions, which was no different from Big Change Starts Small (rip to that initiative). None of these “campaigns” are any different and none of them actually does something substantive. It’s all white noise, gurning, wiglets and gloss. It’s Kate preening for the cameras and telling everyone that she’s a credible expert and a big girl doing important work! As I said, we’re past the point where Kate is a chaotic neutral – the messaging has gotten harmful. Even credible childhood development experts are coming out and saying that Kate’s fluff is dumb and unimportant, that these resources should be focused on actually solving very real problems for kids. All of this and more made it into Omid Scobie’s latest Yahoo UK column – you can read the full piece here. Some highlights:

Kate’s 2012 ‘listening and learning’ charity visits: Chatting with her press secretary at the time, I was told how the duchess’s “keen interest” in childhood development will likely lead to projects focused on supporting the young. A month earlier she had also taken on a patronage with Action on Addiction, a charity working with those suffering from drug and alcohol addiction and the children affected by it. “Right now she is listening and learning… in the future she hopes to find practical ways to contribute,” the palace aide explained.

All of Kate’s sound and keenery, signifying nothing: It’s an extremely important subject. But after 12 years of work, the goods being delivered right now feel light. Some within the early years sector have already voiced frustrations. “We are well accustomed to MPs and royalty visiting early years settings, praising the invaluable work of practitioners… but nothing is done,” a statement from the Practitioners of the Early Years Sector group says. “The time has long passed for ‘awareness’. We need action – long-term investment and funding in the early years.”

Kate’s big-girl problem: And this is where the Princess of Wales will no doubt find herself stuck. Because while elevating the importance of helping children in their first five years of life to thrive is certainly necessary, there are very few options available to Kate when it comes to actually helping solve the main issue at the heart of Britain’s early years crisis – funding. Budgets for preventative services for children in the country have been slashed by more than £400m since 2015 . And 4,000 early childcare providers have shut down in the last year alone due to chronic underfunding.

More slashes to the social safety net: Cuts have also seen the closures of children’s centres nationwide, despite the fact they help prevent more serious social services intervention at later stages in childhood. Britain’s social care system, which is already on its knees, estimates that over 15,000 young people will be taken into care over the next three years. As the country falls deeper into its cost of living crisis, and childcare providers raise prices due to funding pressures, is Kate’s awareness project really able to do much at all?

Ineffective royal work: If anything, Shaping Us exposes the ineffectiveness that the Royal Family’s charity work can have. Because it is almost impossible to make an impact in this field, or even usher in the smallest of change, without considering all the social factors that have an impact on early development. And that cannot be done without stepping into policy or politics — the one thing Kate can’t do as a working member of the Royal Family.

The Art Room disaster: Two years ago The Art Room charity Kate first visited in 2012 shut down its facilities for good after it became no longer financially sustainable. Shrinking school budgets from the government were to blame, and while Kate was able to shine a light on their work through the odd royal engagement, her limitations as a royal patron meant that she would never be able to lobby to keep it going.

The third landmark announcement: This week’s awareness drive launch is the third “landmark” announcement by the Princess of Wales on this topic in as many years. The message is essential, and she makes a serious case, but no matter how many versions of it we hear, Kate’s hope and a wish are unlikely to bring the necessary solutions. Given that Kensington Palace says this is her “life’s work”, I hope she can eventually prove me wrong.

[From Yahoo UK]

While I know what Scobie is doing here – and god knows, he has his own set of limitations as part of the royal press pack – it would be interesting if he actually came out and said it. Like, he’s going too far to half-way excuse Kate here: “while Kate was able to shine a light on their work through the odd royal engagement, her limitations as a royal patron meant that she would never be able to lobby to keep it going.” Kate could easily brush off the shackles of her royal patron “limitations” if she wanted to. She could have hosted fundraisers for the Art Room, she could have used her staff to come up with some kind of scheme to raise money online by selling the students’ art, she could have done a lot more than she did. It wasn’t because of the limitations of the royal role, it was because Kate is lazy, dull and unimaginative.

THAT is the larger problem – while the royal-patronage system is deeply flawed, all of these people could do a lot more without being called “political.” And seriously, if the point of Kate’s dumbf–k Early Years campaign is to raise awareness of just how basic and fundamental it is to give children a head start in life, why is that political? That’s the argument she could make, if she had two brain cells to rub together. “All kids need access to nursery schools and Head Start programs” is only a political hot potato if you think poor children don’t deserve to be nurtured.

-

" her limitations as a royal patron meant that she would never be able to lobby to keep it going."

Complete nonsense. Meghan would have found a way.

Kate really is a useless waste of space. Who just loves to pose. And copy Meghan's outfits.

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

With the US cutting off Russian energy imports today (and the think the Canadians will too soon?) the UK planning to phase out Russian oil (though not gas) by the end of the year and the whole EU planning a 70+% cut in Russian gas by the end of the year (and to totally cut Russia off before 2030) just... will there be a Russian economy? like I see the Ruble is at what 170ish to the dollar? like how long till the average Russian really feels it? Also even if Russia ends the war tomorrow I don't see these energy things going away, they've shit in the punch bowl and the West will still want to get away from their energy (and quickly)

The first thing I'd point out is that the average Russian is absolutely already feeling the effects of these sanctions - the vast majority of the Russian people have already been dealing with underfunding in programs and resources and services for a while now, and don't have much insulation or protection from the impacts, and now you have something this catastrophic and widespread on top of it. I keep bringing it up because I think it's important that we continue to recognize the strain and harm that average Russians are feeling due to both Putin's actions as well as the intense pressure and punishment by Western governments, and to think about the impact both in terms of cost and quality of life and increased repression as well as the long-term political and social consequences. Particularly if people feel that Putin and the oligarchs and others are able to be more cushioned due to their resources.

In regards to whether there'll be a Russian economy - China has indicated support for Russia, and in fact there's been a surge in trade between the two countries (which isn't surprising, considering they share a border and Russia's options are more limited now), and China and Russia have been prominent economic and geopolitical partners for some time now, in an attempt to counter US and Western power and influence.

You also have countries like India and Brazil, and numerous ones in Southeast Asia and Africa, who apart from some votes or statements are not as involved and who are also some key trading partners for Russia. There'll be a shifting in trade and different shipping routes, and especially energy and agriculture (two key industries for Russia) imports, which will be going elsewhere other than the US and Western Europe.

All of this is to say that severe and incredibly painful damage has been wreaked on the Russian people and the Russian economy, and as things continue it will continue to get worse, but that there is the potential for a longer-term shift and reinforcing.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the other hand, and moving away from direct Mechanisms Discourse (which I prefer to not get over involved in tbh but also this ISN'T about that it's just jumping off it) - it absolutely is deeply classist to assume that somebody is illiterate or ignorant because of poverty/assumed poverty, and that's a huge problem. but also I think on a broader social level (at least in the UK) there is an idea in the left that it's classist to acknowledge the connection between poverty and illiteracy, while the truth is that illiteracy is a problem of poverty (poverty not in the sense of just Not Having Money but in the sense of system denial of adequate resources). Poverty doesn't = illiteracy but illiteracy is very much a problem of poverty - not a failure of a marginalised individual but a failure of the system marginalising them.

Adult illiteracy is a surprisingly large issue in eg both rural and urban Scotland, but it's not because poor people are stupid, ignorant or unwilling to learn - it's because schools are inadequate or inaccessible, classes are managed not taught, teachers are stretched thin and schools are underfunded so don't have resources to help struggling students, if you get to secondary school still unable to read and write you're completely locked out of the educational system unless you can access a school with the resources to teach you individually, and because of this, classism and a lack of support, poorer kids are more likely to switch off school as early as possible.

Social geography is also a big issue. In urban areas, schools in poorer areas get bad reputations, so they're underfunded, so they do worse, so they're funded less, etc, until they're a bare minimum of staff just trying to get through the day in collapsing buildings with no resources and five textbooks. Where better-funded schools can afford teaching assistants, 1:1 support for struggling students, decent food provision for kids, follow-up on children in need of support at home, more teachers for smaller classes, maybe counseling and psychological support, maybe Special Educational Needs classes for older kids to work on basic literacy and numeracy to catch up, worse-funded schools have one underpaid unsupported teacher trying to manage a class of 35 kids with wildly different needs. They don't have the resources to help support kids with issues that might affect their schooling, like parental abuse or neglect, trauma, a parent in prison, care responsibilities, hunger, homelessness, neurodiversities that affect their ability to learn in the prescribed way, learning disabilities like dyslexia, physical health issues including visual or auditory impairments...all things that when supported are highly surmountable but when unsupported often end up with children being perceived and treated as stupid, disruptive or evil. The problem then compounds itself because the kids are badly treated which makes them more disruptive and less able to learn, and more and more work is needed to help them which teachers continue to not have any capacity or resources for.

Rural poverty comes with its own schooling issues as well, in that poverty is generally correlated with remoteness. Poor rural communities are often hours away from population centres, so either you have tiny highly local schools serving a handful of families where a single teacher needs to invent lesson plans that somehow balance the needs of 11 year olds and 4 year olds of all abilities, or your kids need to somehow get into town every morning before you get to work, which may mean dropping them off at 6am, having to part pay for buses, taxis or ferries, sending them on their own, or leaving them with friends and family, and realistically the way that often shakes down is that they don't go. You teach them at home, and they may not even exist for the truancy office to know about.

Literacy is also connected to family culture. Both my parents were people with degrees from educated families, and my mum was a full time parent, and the result is that school didn't teach me to read - I was already a confident and enthusiastic reader. Even richer families may hire tutors for small children, pay for extracurricular learning, etc. The poorer a family is, the more likely neither parent is available to spend time reading with their kids, because they're working full time - at that economic level a single income household is almost entirely unviable so either both parents work or there's a single parent working extra hours or they're just exhausted from worrying about the bills and what's sold to them as a personal failure to look after their family.

One thing it's easy to forget is that while people in the UK still do drop out of school in their teens to work, a generation ago it was almost the norm for a lot of communities (especially the children of farmers, miners and factory workers) to have left school well before the end of compulsory education, both because of school being a hostile space and because of the need for an additional income. Now as well as then, a lot of kids drop out to work as unpaid carers, disproportionately in poorer families that can't afford private care or therapeutic support. Literacy aside, generations of leaving school with no qualifications doesn't tend to teach you that formal learning is as important as experience and vocational learning, and you don't expect to finish anyway so why put yourself through misery trying to do well? But it includes literacy. I grew up in a former mining area and a lot of people my dad's age and older were literate enough to read signs and football results, but took adult classes in middle age or later to get past the pointing finger and moving lips. and if you're parents don't or can't read, it's a lot harder for you to learn.

There's a lot of classism and shame tied up in the roots of illiteracy. Teachers and governments and schoolmates will often have vocally expressed low expectations of poorer students; a rich child who does poorly at school has problems, a poor child who does poorly at school is a problem child. They're often treated with hostility and aggression from infancy and any anger or disinterest in school is often treated not as a problem to be solved but as proof that you were right to deem them a write-off. Poorer or more neglected children (or children for whom English is a second language) will often be deemed "stupid" by their peers, and start at a disadvantage because of the issues around early childhood learning in families where parents are overstretched.

Kids learn not to admit that they don't know or understand something, because if you start school unable to read and write and do basic maths when a lot of kids your age are already confident, you get mocked and called stupid and lazy by your peers, and treated with frustration by your teachers. So kids learn to avoid people noticing that they need help. That means that school, which could help a lot, isn't somewhere you can go for help but a source of huge anxiety and pain - more so when you factor in the background radiation of classism that only grows as you get older around not having the right clothes, the right toys, the right experiences, my mum says your mum's a ragger, my mum says I shouldn't hang out with you because you're a bad lot - so again kids switch off very early and see education as something to survive not something helpful.

The same is very much true of adult literacy. A lot of adults are very shamed and embarrassed to admit that they struggle with reading and writing - a lot of parents particularly want to be able to teach their kids to read, but aren't confident readers themselves, and feel too stupid and embarrassed to admit out loud that they can't read well, let alone to seek out and endure adult literacy classes that are a constant reminder of their perceived failure and ignorance (and can also be excruciating. Books for adult literacy learning are not nearly widespread enough and a lot of intelligent experienced adults are subjected to reading Spot the Dog and similar books targeted at small children's interests). Adult literacy classes also cost time and also money, so a lot of people only have the space for them after retirement, if at all.

And increasingly, illiteracy (or lack of fluency in English) increases poverty and marginalisation, and thus the chances of inherited literacy problems. Reading information, filling out forms and accessing the internet in a meaningful way are all massively limited by illiteracy, and you need those skills to access welfare, to access medical care, to avoid exploitative loans, to deal with any service providers, etc. Most jobs above minimum wage and a lot below require a fairly high level of literacy, whether it's office work or reading an instructional memo on a building site or reading drink instructions in McDonalds. Illiteracy is a huge barrier between somebody and the rest of the world, especially in a modern world that just assumes universal literacy, and especially especially as more and more of life involves the internet, texting, WhatsApp, email, and so on - it's becoming harder and harder for people with limited literacy to be fully involved in society. And that means the only mobility is downwards, and that exacerbates all the problems that lead to adult illiteracy.

People who can't read after the age of 6 or so are treated as stupid. People who can't read fluently when they're adults are seen as stupid and almost subhuman. There's so much shame and personal judgement attached to difficulty reading, but the fact that illiteracy is almost exclusively linked to poverty and deprivation is pretty conclusive. Illiteracy isn't about the failure or stupidity of the individual, it's about the lack of support, care and respect afforded to poor people at all stages of their life. Being illiterate doesn't make you stupid - many people are highly intelligent, creative, capable, thoughtful, and illiterate. I know people who can immediately solve complex engineering problems on the fly but take ten minutes to write down a sentence of instruction. It isn't classist to say that illiteracy is caused by poverty - it's both classist and inaccurate to say that illiteracy says anything about the worth, intelligence or personhood of the poor, that it's a result of a desire to be ignorant, or that it's evidence that people are poor because they're stupid, incapable, ignorant or bad parents. The link between poverty and illiteracy is the problem of classism and bigotry, no more no less, and we deal with it by working against the ideas that both poverty and lack of education are a reflection of individual worth.

Illiteracy isn't a problem of intelligence, it's a problem of education, and that matters because education is not inherent. it's something that has to be provided and maintained by parents, by the state, by the community. you're not born educated. you are educated. except more than a quarter of the Scottish population isn't educated, because the system doesn't give a fuck about them and actively excludes them or accidentally leaves them behind.

#idl why i wrote this I'm just very angry about how we as a culture treat adult illiteracy in the uk#which is to say - we don't#we ignore it and think about it as a problem of the past or of other countries#and if we do encounter it we treat illiterate people as uniquely stupid and ignorant#as if it's a personal not systemic problem#26.7% of people in Scotland are either illiterate or have severe issues with literacy#16.4% in the uk as a whole#it's this invisible symptom of deprivation that nobody fucking talks about#less than half of people in prison have basic literacy and numeracy skills#and that's not because only stupid people end up in prison it's because illiteracy is a symptom of the poverty pipeline#and i don't think there's current data on this but I'd guess we're going to see an ongoing dip in literacy rates#correlated with austerity from 2010 on#because child poverty and child hunger in this country has consistently steeply climbed since then#and you don't. learn well. when you're hungry.#and also i anticipate a drop in literacy associated with Covid. it's two years where kids without existing literacy skills#parents who are home and consistent internet access have really been unable to engage with a lot of classes#and teachers have been even less able to offer meaningful personalised support#and two years is SO LONG in early years. being set back two years compared to other students can affect your education your whole life.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

I want to say something.

I’m not going to derail someone’s personal story to bring this up. But: I think it’s important to be aware when you’re playing into “the public schools are broken” narratives.

(This is a US thing, I don’t know how this stuff plays out in other countries except that I know “public school” in the UK means what “private school” means in the US.)

Here’s how it works. Step one. People talk about how terrible/broken/whatever the public schools are when they either mean 1. public schools are underfunded and also aren’t allowed to kick the kids who act out a lot out of the system, only transfer them from school to school, unlike private and charter schools*, or 2. I don’t want my kid to have to go to school with (slur redacted) but if I say that I’ll sound racist so I’m going to make this about something else. Step two. When it comes to voting time, politicians take money away from public schools on grounds that everyone knows they’re broken anyways. Step three, schools predictably get worse. Repeat ad infinitum.

There’s another cycle that can happen, which is instead of talking about public schools being bad, you either talk about schools in general being bad, if that’s appropriate to your complaint (if you’re talking about control and socialization and power and so on), or you talk about the massive challenges public schools face as the awe inspiring project for social equality that they are, and about how they could be so much better if they had more funding. (If you’re talking about things like class size, equipment quality, unchecked bullying, or terrible teachers.) And then you get more funding. And then the schools are better.

There are problems with schools as an institution that’s very much a part of the capitalist system — ie, set up primarily to prepare future adults for the workforce — and something something imperialist propaganda and so on, and schools as an institution within a culture that thinks that kids should have no recourse if they’re treated badly by the adults responsible for them. And there are problems with public schools that have to do with the “too little money” thing and the “kids who act fucking awful to other kids still have to go somewhere” thing. But I don’t think there’s problems that are unique to public schools (rather than also applicable to private and charter schools) that don’t basically come down to public schools doing exactly what they’re supposed to be doing, ie taking everyone and doing it on a limited budget.

And there are actually problems specific to private schools or that manifest in somewhat different ways at private schools and yet you never hear people talking about that.

Be critical of what narratives you’re reinforcing, ok?

Be conscious of, if you’re complaining about public schools, what the plausible alternatives are — namely, greater class (and racial) inequality as public schools get left behind by everyone who can possibly get their kids out of them.

This is not different from the post office thing, or “hey maybe we should replace libraries with Amazon”, or any other “government services should be available to people who actually need them, rather than leaving it to the private sphere who won’t serve poor people because there’s no money on it” thing.

*and shouldn’t be able to, but that is a challenge private schools don’t face.

#do people not type ad infinitum?#autocorrect refused to acknowledge the possibility#public schools#socialism#political

1 note

·

View note

Text

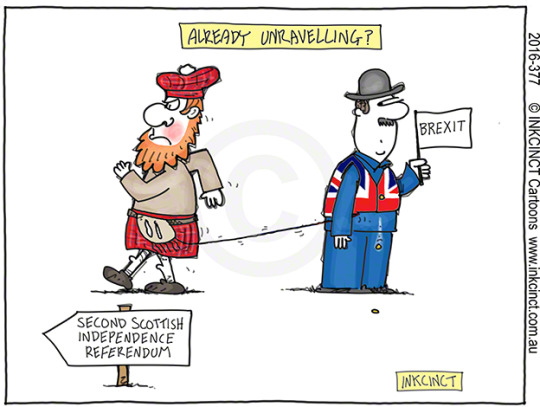

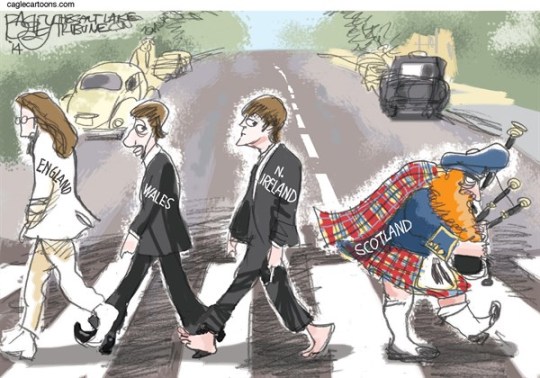

walaw17 asked: Any thoughts on Scottish independence?

I have tried avoiding answers about Scottish independence and by proxy Brexit because like everyone else I am just bored into numbness by the whole on-going soap opera saga. There’s no escaping it. Even within families the conversation around the dinner table is about the next referendum and by proxy, Brexit.

I have Scottish roots on my father’s side and so when I meet my Scottish cousins up in Scotland for weddings, funerals and the like the topic does come up. This summer I was up in the Angus glens for the annual ‘Glorious 12th’ - the start of the shooting season - to join a family shooting party to shoot grouse and share a feast afterwards.

Most of the clan and family friends gathered would be High Tory. Thus they are very much in favour of the Union as they are strong monarchists to boot - even if they have fought for and against the crown at different times in their gilded past. They remain fierce Scottish patriots to the extent that they (good naturedly!) admonish me for taking my Scottish ancestry for granted and being ‘Anglicised’ on my father’s side.

I believe the Scots are for the largely loyal to the Union and they proved that at the last referendum on Scottish independence. But Brexit is now added into the mix and its has clouded the picture somewhat for many Scots. It’s easy to see why.

If I take the Scottish part of my family and their clan. As loyal as they are to the Union there were grumblings about how Scotland seems to be pushed to the margins as Little Englanders run around and use the cover of nationalist fervour to concentrate wealth and power in the City of London to become a free market Singapore 2.0. Even worse leave the United Kingdom vulnerable to the whimsical mercies of Donald Trump if we ever did a trade deal.

Where the Scots differ from the English is that they are natural Euro-philes. Scotland has always been close to France - even shared past Queens. The Scots are naturally outward looking people who in their proud history have always been travelers to the world - to seek work, or settle in new lands, or to trade. Look at the the British Empire, the Scots virtualy ran the empire and even populated it as far as India and North America. So one can’t ignore the impulse of the Scots to not turn its back on Europe.

The first minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon, now proposes a second Scottish referendum. While politically justifiable even if it’s opportunistic, this is not the best way forward.

Less than three years removed from the first referendum, in which Scotland voted to remain in the UK by 55%, the question of national sovereignty returns to the political forefront. While 52% of the UK opted to leave the EU, 62% of Scots voted to remain Citing the manifesto of her Scottish National Party (SNP), which holds the majority in the Scottish Parliament, Ms. Sturgeon stated that Brexit constitutes a significant and material change from the 2014 vote and a new referendum is necessary. In this, the first minister is right to call for a referendum, as circumstances have unquestionably changed. Forced to leave a union most Scots prefer, the nation should have the right to reevaluate the partnership with their southern neighbours.

Scotland is better off remaining part of the UK than leaving it. The SNP, a separatist group at heart, is misleading its countrymen by saying otherwise. The timetable set by Ms. Sturgeon places undue pressure to resolve Brexit during an already tight window of two years. With Greenland taking roughly seven years to finalise its departure from the European Economic Community, it is hard to believe the UK, a political and economic behemoth in the region, departing in a mere couple. The timetable also provides Scots with little ability to make an informed decision. Much uncertainty exists regarding Brexit and its future ramifications for the UK after Oct 31st. These are not empty words, as Scots increasingly believe that there should not be another referendum in the next few years.

Even for a leader with high approval ratings like Ms. Sturgeon, referendums are risky. The first minister need not look further than her European counterparts, where referendums in the UK and Italy led to the self-inflicted downfalls of David Cameron and Matteo Renzi. Ms. Sturgeon would be wise to learn from the past, as referendums can have dire and unpredictable consequences on a political career. She should act more like the citizens she was elected to represent, who currently have little appetite for another vote. Even if one were held, the most recent polls shows only 37% of Scots supporting Scottish independence.

Arguing for departure from the UK may play well politically, but it would have disastrous ramifications for the small northern nation.

How did we get here?

Through the inattention of the leaders of the British government of the two major political parties is one obvious answer. Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair was eager to devolve power from London to representative assemblies in Scotland and Wales, despite the constitutional problems. Large majorities of Scottish and Welsh parliamentary constituencies elect Labour members of the House of Commons, and particularly in Scotland there was deep discontent with the policies of Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. They associated them with the inevitable decline of Scotland’s heavy industries — steel, shipbuilding — and the high unemployment that resulted. Glasgow, once the proud “Second City of the Empire,” as you can readily imagine when you see its impressive century-old downtown office buildings, was particularly hard hit. Scotland, since the Act of Union of 1707, has provided a disproportionate share of Britain’s philosophers, statesmen (11 prime ministers including its most recent in Blair, Brown, and even Cameron), colonial administrators and military officers and men.

Now the Scottish economy is dominated by the public sector, and the Scots are suffused with self-pity over what they regard as the underfunding of the welfare state. Scotland’s second Parliament went into operation in 1999, with Labour party stalwart Donald Dewar as chief minister and with power over much of Scottish domestic policy, including the ability to raise taxes. Indeed under the 1707 Act of Union, Scotland retained Scottish law rather than the English common law, kept the Presbyterian established Church of Scotland rather than the episcopal established Church of England; and under later legislation ran its own education system.

But in 2007, as Labour’s popularity was declining in the UK generally, Labour lost its majority in the Scottish Parliament and the Scottish National Party’s Alex Salmond became chief minister. With a Scots Nats majority, Salmond pushed for the referendum and he got an apparently absent-minded Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron to agree to terms favourable to the separatists: the 16-year-old vote, the exclusion of Scots in the military or otherwise living outside Scotland, the fact that a “yes” vote favours separation rather than continuation of a relationship that has produced one of the world’s greatest nations for 307 years.

Scottish independence advocates argue that an independent Scotland will be able to tax itself to its heart’s content and will be able to draw on endless North Sea oil revenues to pay for whatever level of social services and community provision Scots want. But that’s unlikely. North Sea oil production is declining, and a pro-independence vote would be followed by negotiations between England (or rUK, rest of United Kingdom, as some dub it) over the division of oil resources — and division of the national debt.

UK authorities have made it plain that Scotland is not welcome to retain the UK pound, and that if it does (as Panama and Ecuador have the U.S. dollar as their currency), Scottish financial institutions won’t get a bailout if they get into trouble. So it seems likely that the two major Scottish banks and other financial institutions will move their headquarters and legal residence to London if Scotland votes for independence.

The EU’s doctrine of ‘subsidiarity’ seems superficially pro-devolution and the Treaty of Maastricht created the ‘European Committee of the Regions’ to promote regional identities against national capitals. But what is the reality? Neither Spain nor France will permit the precedent of secessionists joining the EU. During the 2014 Scottish Independence referendum, the European Commission said Scotland would not inherit the UK’s membership of the EU.

Brussels instinctively backed Madrid against Catalonia, prompting famous Breton musician Alan Stivell to lament “Catalonia’s political prisoners represents the suicide of the idea of Europe”. And the EU has a poor track record of looking after small states like Ireland. Brussels forced two ‘People’s Votes’ after Irish referendums went against the Nice and Lisbon treaties. The bail-out imposed on Irish taxpayers, politicisation of the Irish border and Corporation Tax harmonisation fuel rising Irish Euro-scepticism.

For all this politics are about passion and not reason, especially when you deal in mobilising (low information fed) populist sentiment.

This is why I fear that the economic arguments against Scottish independence, while strong on the merits, are less likely to be persuasive than an appeal to cosmopolitanism and history: the fact that Scotland, as part of the United Kingdom, has in many ways led the world over the last 307 years, intellectually in the Scottish Enlightenment of the eighteenth century (which helped inspire America’s Founding Fathers), economically in the industrial revolution, politically in the British Empire and then the British Commonwealth of Nations. Scotland looms larger in the world as part of the UK than it would as a separate nation.

The first minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon, has the right and perhaps may even be right to hold a Scottish referendum in the near future, but she should not do so at the expense of her citizens’ prosperity. Once the ramifications of Brexit and voting to leave the UK are fully known, then Sturgeon could consider proposing another referendum.

But I hope the arguments against independence prove successful and that whenever Scotland has a second referendum the vast majority of Scots vote ’No’. And if or when that happens the Scots will cease to be transfixed by the idea of secession, as have voters in Canada’s Quebec. Casting aside a working relationship which has had such outstanding results for the (by no means assured) chance of a slightly higher-spending welfare state seems like a foolish idea.

I have argued with Scottish family and friends that Scottish independence would disturb our identities more profoundly, in ways that few yet grasp.

Our modern politics are Whiggish. Even the name “Whig” comes from the term “whiggamor” meaning a Scots cattle-driver. As someone who was raised High Tory values from an early age, I find that hard to concede but it’s painfully true certainly from the 17th and 18th Centuries onwards with the rise of parliamentary democracy. I suspect it’s even harder for Marxist inspired leftists to stomach given the socialist driven Labour Party have traditionally worked within Whiggish principles despite their fiery rhetoric being matched only by their incompetence to actually govern.

Whiggism favouring the theories and practices that evolved in the formation of the British constitution. But a lot of Whiggish ideas evolved out of High Toryism and so as a committed British royalist I have a strong attachment to the Anglican Church, and of course the British constitution is modelled upon and arose directly from Anglican theories of governance. But it is British, not English. Perhaps because her name begins with E, Elizabeth Saxe-Coburg and Gotha is sometimes thought of as an English monarch. But she is Elizabeth I of Scotland, of a German family introduced to rule in Britain not just in England. We have little, if any, reason to imagine that, absent the joining of crowns in 1603 or the Union of 1707, the constitution of England (or England and Wales) would have evolved remotely to resemble the British constitution as we have had it.

British Whiggism has not only slowly seeped into and eroded the ideological underpinnings of High Toryism (think of Thatcherism rather than Lord Salisbury) but it has also ben entrenching a Whiggish inspired constitution over the past 400 years or so. But if Scotland leaves, that constitution and its history are over. There is little reason at base to imagine an English-only constitution any more (or less) likely to evolve in a future direction I would favour than, say, a European constitution. If Britain is literally finished – if the Union is broken and our constitution is no more – why would an England-alone future be any better than, say, membership of the Single European State? England survived perfectly happily as a component of a larger Union within Britain. Why should it be any less content as part of a larger union in the EU Federation?

The reality is that despite the marginalising of High Toryism, it is the Conservative party as the party of Britain, that has been the inheritor of the Whiggish tradition and appointed protector of the Whiggish constitution. If Scotland leaves the Union the Conservative Party would be finished in its present form, because it would dominate England so overwhelmingly that it would inevitably split. To be sure, it would perhaps last two or three more General Elections, in which with huge majorities it would govern in England (Wales doubtless becoming semi-autonomous and Northern Ireland departing to join Scotland forthwith). But no party that won 75 per cent and more of the seats in the House of Commons could last for long. Our adversarial politics needs an opposition as well as a governing party. So the Conservative Party would split, perhaps into Tories and the rest.

This is why ironically I believe in Brexit even if our current crop of incompetent politicians are making a real dog’s dinner out of it.

Passions aside, for me Brexit is an opportunity to reboot unionism between England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

It may twitch my High Tory nerves a little but I am coming around to the view that Brexit, the biggest ever vote of confidence in the political project of the United Kingdom, is an opportunity to fashion a new unionism. This new unionism might well have a sharper focus on citizenship and rights but it might also trash the canard that Brexiteers are little Englanders. A clean Brexit can rejuvenate marginalised and fraying institutions that were once the bedrock of a collective national identity. But only if we re-orienteer ourselves and go back to the original principle that allegiances of Unionism are to institutions and symbols of nationhood and shared national values. If we can do that as a union then one might be able to capture a greater diversity that narrow nationalisms rather than widening them - under of course a unifying national figure of a monarch.

Even the most ardent of the free market Brexiteers will have to accept that the best one can hope for is a Unionism as the quintessential one nation politics. Here such Unionism acknowledges the reality of an inegalitarian society made up of people with different talents but tempered by roles and responsibilities that has an ingrained sense of a duty of care to others. But equally Unionism stands for equality amongst citizens governed by the same rules and respecting the authority of enduring institutions. All votes are of equal value in one of the world’s oldest and most successful democracies where MPs serve constituents rather than outside sectional or multi-national corporate interests.

Ironically then the best chance Scotland for its future is Brexit. Brexit will protect the Union that puts the ‘Great’ into Britain. Unionists can be confident we will stay better together in the good Union of the United Kingdom as we leave the bad union of the EU.

Thanks for your question.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

The UK is such a mess.

Poverty, homelessness, fewer jobs for un/low-skilled workers, kids starving, old people dying, more kids in care, Brexit, adult social care and the NHS!

Parents struggling financially face many problems, not least of all potentially and unintentionally placing additional stress on children. Kids growing up poor understand that no-one knows where the next meal is coming from, or if the electricity will stay on, or if they’ll get lunch during the summer holidays. Not to mention there is no money for extra-curricular activities, day trips out or even a new football to kick around in order to stay out of trouble. (https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2019/dec/02/growing-up-poor-britains-breadline-kids-review-the-lives-stolen-by-poverty)

Too many children live in temporary accommodation, often sharing one room with siblings and parents. They are expected to focus at school, whilst teachers apply pressure to “perform” like monkeys - sit this test, pass that exam, all so the school can justify itself and draw down funding. Our children are more stressed than ever and we’re raising a generation filled with mental and physical illnesses and conditions that a few decades ago hadn’t even been heard of! “The most recent quarterly statistics recorded 84,740 households in temporary accommodation at the end of March 2019. This represents a 77% increase since December 2010, where the use of temporary accommodation hit its lowest point since 2004″ (https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/SN02110).

Countless parents struggling with with finance, work, housing, accessing support, healthcare and more, may also be suffering with mental/physical health conditions; and therefore, the whole family suffers. And before anyone gets on my case about people on benefits, most of the 4.1 million children living in poverty have at least one parent working! We've created a whole new 'class' of people in the UK in recent years - the "working poor" (https://www.theguardian.com/business/2018/dec/04/four-million-british-workers-live-in-poverty-charity-says).

However, companies want their profits and too many large corporations make millions, if not billions every year, whilst desperate people cling to work, hoping their child isn’t sent home sick from school, praying their car makes it on the little bit of fuel they’ve just put in; and plugging away for hours on end without any food because there is nothing in the cupboard to make up a packed-lunch and their kids are receiving free school meals because there’s just no other choice.

There are no council houses, social housing is a joke (waiting lists approx. 7-10yrs) in some local authority areas, and private rents are through the roof. Our NHS is slashing services, and closing clinics and local hospitals, which reduces the provision to those most in need; including mental health teams and adult social care (https://nhsfunding.info/symptoms/10-effects-of-underfunding/cuts-to-frontline-services/).

However, children’s Social Services appear to doing just fine in the sense that they’re busy enough accusing parents of abuse and/or neglect, simply because they’re battling ‘life’ on a daily basis. They’re very quick to remove children from ‘good enough’ parents, fast-track the paperwork to court and apply for removal orders left right and centre; leading to private Fostering and Adoption agencies cashing in! This video highlights just some of the issues with Social Services and the system as a whole: (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a7TcFWqKja8).

Trying to 'survive' creates stress, which has many wide-reaching physical and mental implications; from hormone imbalance, metabolic disorders and weight gain, to fatigue and eating problems. Many parents do go without so that their kids can eat, yet they still gain weight and lose energy, feeling exhausted every day, simply due to the stress they're under. Choosing between heating and eating creates health issues, with malnutrition identified in the 5th richest nation in the world and the elderly dying of being unable to afford the gas fire (https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/cold-weather-uk-winter-deaths-europe-polar-vortex-a8224276.html).

The Labour Party, under Jeremy Corbyn, aim to privatise energy, water, rail and the postal service, as well as some other utilities and services; however, they need to go one or two steps further. The NHS offer should extend to in-home care and the running and regulation of care homes (with those who can afford to pay, doing so) and the government should regain control of children’s services, with private fostering and adoption companies being take out of existence (https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/nov/23/revealed-companies-running-inadequate-uk-care-homes-make-113m-profit).

Unless something changes on a national scale, with a new government and new direction, the mental health crisis is only going to get worse, along with other social problems such as excessive drinking and drug-taking (used as a form of escape), increased crime rates and gang membership, and anti-social behaviour (often due to boredom), etc. Parenting hasn’t become worse, people are fighting to survive! Nurses are going to food banks, fire fighters work second jobs; Police recruits are low caliber due to the starting pay offered and standards being lowered during recruitment drives. Teachers are watching kids fall asleep in class because they’re not eating and sleeping properly.

You only need to take a look at some news headlines to realise just how out of control everything is. On top of the national political and socio-economic issues facing the UK, privateers are pressing on with a needless and expensive high-speed rail network - HS2 is now an £88 BILLION pound project! Imagine what could be done with all that money (https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2019/sep/03/hs2-to-be-delayed-by-up-to-five-years). It would certainly solve a few problems.

So whilst business commuters might, eventually, be able to arrive at their destination 30mins earlier than before, the general population is duct-taping their shoes together and sewing holes in socks, just so they can go to work to earn enough to barely keep a roof over their head and food on the table, and the big businesses just keep getting richer (https://www.theguardian.com/news/2019/dec/03/uk-six-richest-people-control-as-much-wealth-as-poorest-13m-study).

And what about the planet? Are poor people really interested in recycling, sustainable living and providing a nurturing garden habitat to attract wildlife (for those lucky enough to have access to a garden of course)? Some might be, but in the main, people are overworked, underpaid, stressed beyond belief, exhausted and trying not to yell at the kids or argue with their partner because everyone feels the same and is rubbing each other up the wrong way.

The UK desperately needs radical change. Never mind the disaster that is Brexit, the more urgent issue is “survival”. Charities, foodbanks and the like help, but they should even need to exist. There is more than enough money, food and water to go round; it’s simply a case of sharing the wealth.

Controlled procreation should also be on the agenda. Not the systematic theft of children by Social Services, ‘upcycling’ kids to ‘better’ families to reduce the number of underclass and bring down the welfare bill. But the responsible, educated, proactive approach from people choosing to have children. Ideally, a couple would stay together and have up to 2 children, live in a safe, warm and comfortable home, raise them well and encourage them to do the same. However, many are choosing to have 3 or 4 children, and in some countries many more, and the planet is overpopulated. Yes there are issues around adult separation and rape case where the pregnancy isn’t terminated, but this focuses on more general planned parenthood.

Birth control and education must be provided worldwide and the relevant support provided to parents who need help - often, it’s simply a little guidance or support, but instead, in the UK they’re often faced with meetings, court appearances and parenting assessments, as they are accused of not being able to cope. As a human race, there is a responsibility not to over-produce more humans! Earth is running out of resources and the air and water is becoming more polluted. Eventually, people will be hunting each other and fighting over scraps because everything else is gone. Millions will have died off through dehydration or starvation. Medical services won’t be available. Money will not longer be of value - unless of course you can digest it to gain a few dollars worth of energy.

Also, we’re so intent on living longer, curing disease and holding onto pregnancies which otherwise would have self-terminated; yet we’re overrunning the planet with more and more elderly, sick, disabled humans needing to be cared for. We’re creating more problems than we’re solving and we’re not being responsible. We all want to keep loved ones close, but can we afford their care, or do we have somewhere to place them until they finally pass? Of course Cancer is a multi-billion-pound industry and therefore, sick people equals profit for big pharma. China had a one-child policy which created many issues for a long time, however, they reduced their population and increased it to 2 only as recently as 2016 (https://www.newscientist.com/article/2214179-chinas-two-child-policy-linked-to-5-million-extra-babies-in-18-months/).

There is no easy answer. Low-skilled jobs are replaced by self-serve checkouts, Universal Credit has plunged thousands of people into unnecessary debt, the rising cost of living is not reflected in wages, people are living in unsafe properties because they have nowhere else to go and others perish in fires due to inadequate building regulations - 2yrs on from Grenfell and still no changes have been made (https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/dec/03/fires-grenfell-towers-combustible-cladding).

The poor simply don’t matter and currently, there are too many of us for the government’s liking, so it’s doing it’s best to kill us off. It’s a Social Cleansing agenda which serves the richest, most powerful in society. Many of us will live on, clinging to work, hoping for a brighter day; all the while putting more money into the off-shore bank accounts of the elite from which they buy their yachts and private jets, champagne, cocaine and pretty boys and girls to play with (https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/anneke-lucass-harrowing-tale-of-sex-trafficking-am/).

This world is SICK and getting sicker. We’re hoping for change. We’re hoping for a UK Labour government and for Donald Trump to be removed from the White House - that would be a good start. We’re then hoping to cascade the transformation around the world, to lead by example and have the 1% share the wealth they have accumulated through the enslavement of the general population - starting with paying Tax.

If you truly care about your future and that of your children, take action:

- vote Labour on 12th December 2019.

- vote for a decent POTUS candidate.

- boycott big pharma and big corporations - buy local, reuse, recyle and repurpose. Use repair cafes and similar to swap, make good or otherwise utilise products which already exist instead of buying new.

- help your neighbour - buy in bulk, cook and eat together to reduce costs and waste, plant your own food, eat less meat/become vegan. Cook in bulk and freeze meals for another day.

- responsibility manage household energy consumption and look for solar/wind options.

- carefully plan and be responsible for just one or two children, lessening the load on this planet and your bank balance.

- be happy with what you have - go charity-shop shopping instead of buying new; move things around or swap rooms about instead of redecorating every couple of years. If you cannot sell an unwanted item, give it away, don’t bin it.

- stop going mad at Christmas and reduce down what you buy for Easter, Halloween and other occasions. Wrap your gifts in newspaper or recyclable materials.

- use metal or glass water bottles and refill instead of buying plastic all the time.

- understand the law! You never know when you might be fighting a battle with the powers that be - become your own detective and your own legal team. From employment law to the Children Act 2004, familiarise yourself. Legislation touches EVERY part of our lives, from driving to renting a house, and from buying food to taking out a mobile phone contract. You need to know how to protect yourself every step of the way. The authorities (currently) are NOT on your side, so make sure you’ve got your own back!

1 note

·

View note

Text

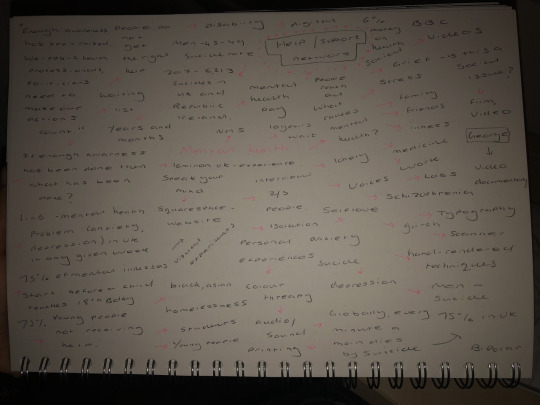

Idea 2 - mental health & examples of work

Breaking the stigma around taking a mental health - is this a issue that needs to be spoken about? How do people feel when it comes to mental health? These are things that I want to find out and research into. Again, this is a subject that I feel strongly about as I feel that everyone gets affected. It doesn’t mean that you need to be diagnosed with a serious illness, but it goes back to simple feeling too like stress, panic, anxiety, depression, loneliness.

I have made a mind map in my sketchbook about facts, opinions and possible ideas that I could explore. I feel that today society is really impacted by mental health and I want to make people talk about it and not hide from their feelings.

One thing that I have noticed popping up again while researching is that UK mental health services are failing young people. ‘‘Young people’‘ could this be a target audience that I can explore within in my work? I feel that I need to focus on audience in which will be effective with the work that I will be producing. This is something that I need to return to and solve out.

Here is a article I found.

Mental health isn’t being talked about and there seems to be a stigma that is attached to it in genders, socially and culturally. Why is this? Is it because of history or generations that pass down on how we should act and feel?

History

Mental illness has a long history from being thought of as the mark of the devil to being considered a moral punishment. Treatment has historically been brutal and inhumane. The Neolithic times, involved chipping a hole in the person's skull to release the evil spirits.

I think the stigma has come out of fear and a lack of understanding.

What types of mental health illness are there?

Schizophrenia

Anxiety

Bipolar

Depression

Stress

Eating disorders

OCD

Personality disorder

Psychosis

Self-harm / sucidal

Facts

One in four people will experience a mental health problem at some point in their lives.

Around one in ten children experience mental health problems.

The number of people experiencing mental illness in the UK is 16 million

Women are more likely to have mental health issues

11% of the NHS budget is spent on mental health

Half of all mental illness begins by the age of 14

75% of young people with a mental health problem are not receiving treatment

Drugs are the most common form of treatment

The average waiting time for effective treatment is 10 years

Up to 300,000 people with mental health problems lose their jobs each year

These facts and statics are shocking. I am disappointed that the only common treatment is drugs. I strongly disagree with this. The number of medicines given for anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder and panic attacks have more than doubled in the past 10 years. I feel that there are other methods of treatment that can help people and drugs is not one of them. You can get side effect and gain other illness by taking drugs. What if a person relies on drugs and starts to take too many? This is a problem I want to solve. Treatments can vary from therapy, meditation, focussing on health and food, talking to people and does not need drugs. I feel that this only a choice as the government find it easier to treat by giving some one drugs and leaving them with that. The issue does start with the government - why cannot they make new rules with health care and help people?

Mental health stories / voices

How can I make thee voices be heard? How can I tell people who don’t understand what it is like? Maybe I can use visual elements and communicate the feelings, frustration and express what mental health can be like when you are dismissed and not understood.

Examples on what has been done?

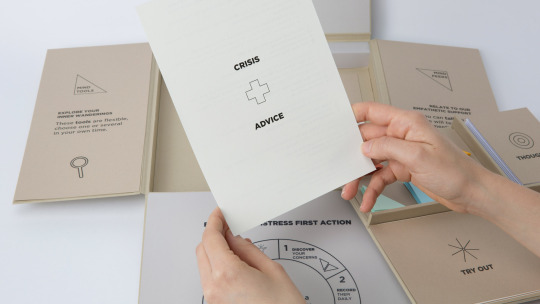

Mindnosis by Sara Lopez Ibanez - has created a self-assessment kit to support those with mental health issues. The artist researched how the UK approaches mental health what types of therapy they offered. She found that people struggled with the initial communication with their doctors. She solved this problem by creating a kit, which allows users to discover the type of help they need, and where they can get it from. It includes a set of eight activity cards that combine mindfulness, cognitive behaviour therapy techniques and tips from peers to help users when they feel unwell.

I like the idea and concept of the design, however feel the design is washy and dull.

Tear Gun by Yi-Fei Chen - created a visual metaphor in the form of a tear gun that represents her personal struggle with expressing her thoughts. The gun fires bullets made from frozen tears. The designer made this because of a negative encounter she has with a tutor. The gun was made as a response to this as well as to show she was unable to voice her personal struggles.

I think that this product is clever, however how will this help others who are going through mental health?

Calming stone by Ramon Telfer - Ramon Telfer who struggles with anxiety worked with Calming stone co-founder Alex Johnson to develop a hand-held device that eases anxiety through the use of light and sound. I think that this device is appealing and if it uses light and sound I know scientifically this can effect our mind in a positive way.

The device needs to sit in the palm of the hand, then a copper ring sensor will run around the edge while sensing the user's heart rate. It mimics the rate with a softly glowing light and a slight pulsing sensation.

The designer states: ‘because stress is very real and life is a fully tactile, sensory experience, we have created and evolved our learnings into a beautiful, intimate product that anyone can hold, feel and listen to’.

I can see how this device is helpful and I like how it works. It would be cool if it had a voice which could read out some advice or do some mediation techniques.

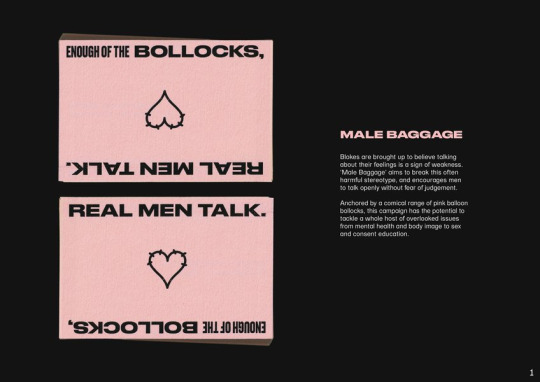

Male Baggage - this is has a target audience for men who are brought up to believe talking about their feelings is a sign of weakness.

‘Enough of the bollocks. Real men talk’.

This aims to break the stereotypes that are formed, and encourages men to talk about their feelings without fear of judgement. It has comical point of view as it has pink balloon bollocks attached. I think that this campaign is effective and different. It has the potential to tackle a whole host of overlooked issues that mental health has formed over many years.

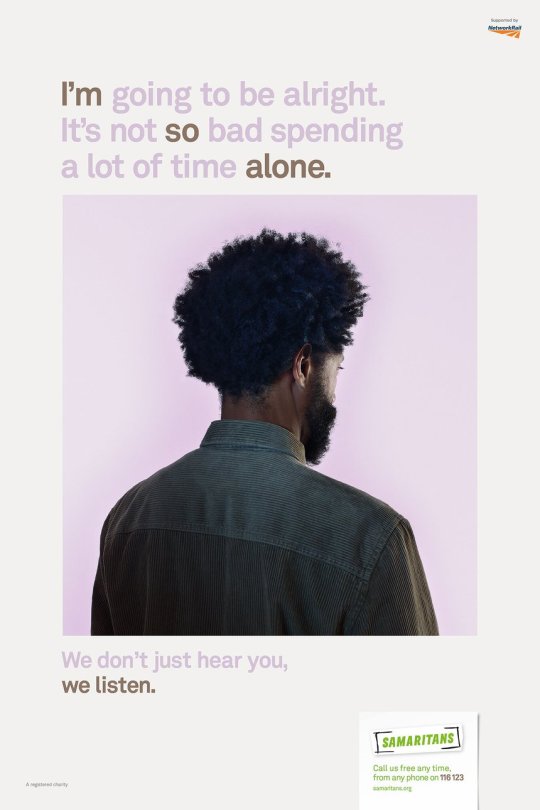

Samaritans We Listen by MullenLowe London - this agency has made posters to provide support to people when they are most in need. The charity works with the UK train industry to reduce suicides on the country’s railways as this is a issue that happens frequently.

After doing some research Samaritans had identified they were hearing from people when they were already at crisis point. What the best way they can do to prevent suicide is getting to people much much earlier. They want to get to the point of initial distress, rather than getting the last desperate phone call.

I like how the poster has highlighted specific words and added their details at the bottom of the poster. Could I create a poster? I feel that posters are something that gets designed easily by putting on a message and image and your done.

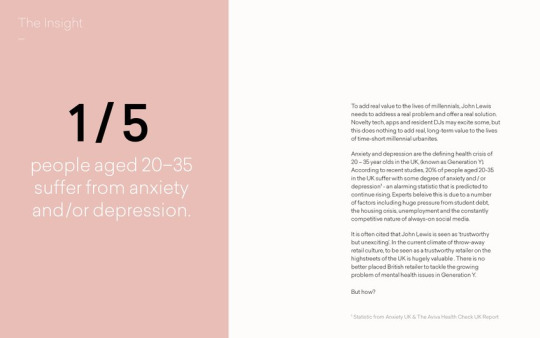

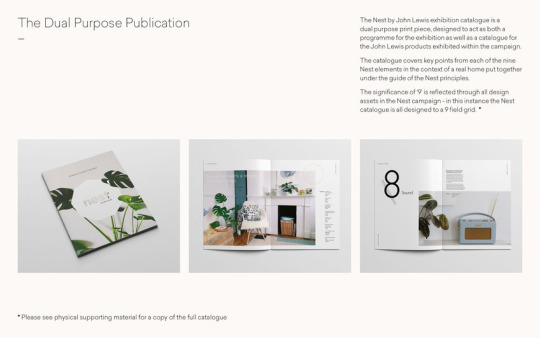

Nest by John Lewis - is an campaign created with the mental health charity Mind. The purpose was to demonstrate how your home environment can directly affect your mental health and wellbeing. This guide helps people to declutter their home.

Anxiety and depression - health crisis of the millennial generation.

1 in 5 of 20-35 year olds currently suffer with anxiety and / or depression in the UK .

These are issue that still isn't being publicly addressed. I can appreciate how this charity help people declutter their homes as it does affect our mood and wellbeing unlike research I have done that shows drugs are the common treatment given.

Looking at this for inspiration I feel like a guide is something that I can produce - I just need to find my message and what I am solving.

Stuart Semple - raise funds for CALM – campaign against living miserably. This artwork is apart of the band, Placebo. The artist is an ambassador for Mind, the mental health charity. Semple wanted to bring awareness to the issue of mental health and made this art piece.

He researched into suicide and that it is the single largest cause of death amongst young men (20 – 45) in England and Wales.

The charity helps and supports men of any ages who are down or in crisis using their telephone line and website. They also do work to challenge the stigma and culture that seems to prevent men asking for help.

The artist states: ‘’I feel that this is vital and valuable service that goes underfunded’’. So all the bids on his work will go straight to the charity.

I like the art piece shown and the effects that have been applied. Everyone has different pieces of design that expresses this situation. I feel that if I was to choose mental health how can I use design to express my response to this brief.

#mental health#Typography#health#mental#mental health uk#uk nhs#nhs#doctors#drugs#social cause#issue#social issue#graphic design#graphic design solution#art#design#art and design#john lewis#semplastico#male baggage#tear gun#mental health design#planning#ideas#mindmap#soltions#can graphic design save your life?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Housing affordability: Social impact funds to solve the UK puzzle?

Similarly, BMO REP, which is behind one of the latest affordable housing funds to come to the market, argues that its investment case stacks up both from a financial return and social impact.“There is a very interesting space where you can provide potentially more sustainable-type income characteristics, and therefore on a risk-adjusted basis it really does make sense for investors,” says Angus Henderson, head of business development at BMO REP. “So I don’t buy into the fact that just because something’s got good ESG characteristics it has to be a lower-returning type product. It can be core in its nature and deliver a core type of return with defendable income.”Working with housing association Home Group, the BMO UK Housing Fund will create purpose-built accommodation for low to middle-income households. Its target audience will be ‘key workers’, such as emergency-services staff, struggling to pay market rents near to where they work. It uses a flexible-rent model to ensure it remains affordable to different households, thereby reducing income volatility. It is targeting a 6% return and 4.5% annual distribution.“We wouldn’t see a trade-off here at all,” says Henderson. “On a risk-adjusted basis that is the right return for the product.”Nuveen Real Estate is another fund manager looking at affordable housing. Tanja Volksheimer, senior portfolio manager for Europe, has been focusing on social-impact potential and agrees with this notion. “If you really take the lower rent, you have less fluctuation,” she says. “People do not maybe move out as quickly.”Can social impact funds address the UK’s housing crisis and serve pension funds at the same time? Richard Lowe reports

Widening inequality, the rise of populist politics, growing public fears about climate change and the advent of potentially disruptive technology have prompted the financial industry to stop and think about how it goes about its business.

The emerging consensus seems to be: capitalism needs to become less short-termist and more inclusive. The primacy of shareholders is now being questioned within capitalism rather than, as has traditionally been the case, from without.

As if to underline this notion at the start of a new decade, BlackRock announced on 14 January that it would place sustainability at the centre of its investment approach in response to shifts in investor preferences. The world’s largest asset manager effectively endorsed inclusive capitalism.

It is within this context that something seems to be happening in parallel within the institutional real estate industry: the mainstreaming of social impact investing – principally, in the form of social and affordable housing strategies.

Institutional real estate investors have for some time being incorporating – or pressuring their investment managers to incorporate – environment, social and governance (ESG) practices into their investment strategies. Hence the rise of the real assets sustainability benchmark GRESB, founded by a number of pension funds and a very visible catalyst in this area.

But while the adoption of ESG was, in effect, about the integration of a new element of risk management – of protecting future returns against the costs of greater regulation and arbitraging the future demand for green buildings – impact investing is different.

Impact investing has explicit objectives beyond maximising (or protecting) financial returns. It implies levels of performance measurement running in tandem: financial and impact. This had traditionally meant it fell outside the remit of institutional investors, which typically have a fiduciary duty to generate the best possible risk-adjusted returns for their ultimate beneficiaries.

But the situation is changing. There have been a number of impact real estate fund launches recently, and the past 12 months have been bookmarked by the launch of two UK affordable housing funds: one by CBRE Global Investors at the start of 2019, and one by BMO Real Estate Partners (REP) at the beginning of this year.

There seem to be at least two reasons behind this. One, there is a growing recognition that having a positive social impact is becoming important to some of those ultimate beneficiaries and might also be in the long-term interest of institutions invested in the real economy.

Two, there is a growing argument that optimum risk-adjusted returns and measurable social impact are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

Peter Hobbs, managing director of private markets at Bfinance, who advises investors and carries out fund managers searches, has witnessed a marked pick-up in interest in impact real estate strategies. And none of them are prepared to “forgo a financial return”, he says. “They all say at the outset, we’ve got to achieve this return and we want to achieve an impact. And it is their fiduciary responsibility to achieve that return.”

It was a point Hobbs made last year at a social impact seminar in London organised by the Association of Real Estate Funds (AREF) and the Investment Property Forum (IPF). During that event, James Giles, pension investments and risk manager for the Co-Op group, revealed how Co-Op pension fund capital was being invested in affordable housing. He said the pension fund had started to look at how it might be able to make a social impact when seeking out low-risk, inflation-linked real estate investments in the UK. PGIM Real Estate, which invests on behalf of the Co-Op continues to help it build up a portfolio of affordable housing in the UK.

Hobbs believes affordable housing could become bigger than the burgeoning private-rented sector (PRS) in the UK. He says a number of investors are wondering if affordable housing might potentially offer “better risk-adjusted returns” than traditional PRS, because it is “less cycle-exposed” and responding to a greater “structural need”.

The first mover into UK affordable housing was Cheyne Capital, which launched the Cheyne Social Property Impact Fund in 2014. For Stuart Fiertz, co-founder, president and director of research, it has been about matching up the acute demand-supply imbalance for affordable housing with another demand-supply imbalance – for inflation-linked assets on the part of UK defined-benefit pension funds.

“We recognised there was a convergence of a number of factors that made this a compelling opportunity, which are still just as true five years on – arguably even more true than when we set up five years ago,” Fiertz says. “You have the world of defined benefit in particular crying out for inflation-linked assets,” he says. “We set about trying to address this massive demand, this underbuilding of housing, the length of the waiting lists, the amount of people in inappropriate temporary accommodation.”

Fiertz says Cheyne Capital’s affordable-housing investments are more sustainable and are a better proxy for inflation than typical PRS strategies. “This housing will remain affordable through time because wages will rise at about the same pace as the rent was rising – unlike traditional PRS where there is always an assumption that the rents will rise faster than wages, which is not sustainable in the long term,” he says.

“We’ve also seen that UK institutional investors are underinvested in residential property,” he adds. “They can either go the direction of many of their peers into traditional PRS. But some of them are recognising that actually a long-term lease that is inflation-linked gets them the return profile that they actually want. They don’t want house-price inflation, because their liabilities are not linked to house-price inflation.”

So, can affordable housing really give investors the best of both worlds – social impact and more-appropriate risk-adjusted returns? “I think we’ve won the argument that impact investing does not entail a sacrifice of return or a degradation of the risk-reward,” Fiertz says.

But not only could affordable housing provide more stable and sustainable income streams for investors than higher-rent housing, it might also be less exposed to regulatory risk. As we highlight in the latest edition of IPE Real Assets, there is growing pressure on governments – both in Europe and the US – to put the breaks on unregulated private-rented markets. Rental caps and other controls can materially affect PRS and multifamily investment strategies.

“With everything that is happening on the regulatory level, you don’t know what is happening,” says Volksheimer. “I think this is very risk-averse and could be a risk-management tool worth pursuing.”

Nuveen is already investing in affordable housing. It recently invested in Shore Hill, a senior-housing community in Brooklyn where tenants pay no more than 30% of their income towards rent, leading to the property’s rents being roughly 45% below Brooklyn’s market rents.

“There is an affordability restriction on the property that will run out in three years’ time,” says Volksheimer. “Nuveen together with a co-investor actually will renew the mission and keep this property affordable, which is usually where a traditional investor would swoop and say, okay, I’m going to put balconies out front, I’m going to drive the people out, I’m going to increase rents.”

Moving beyond ESG Volksheimer believes that impact investing will become bigger in the institutional real estate industry than the niche activity it is today. “Ten years ago, we wouldn’t have thought that green buildings would be so sought after,” she says. “Maybe impact investing will not be totally separated from the traditional investing because it will have been fully integrated into our thinking. The profit will be combined with the wider purpose.”

Hobbs says impact investing is probably going to be bigger than ESG. He also thinks the real estate industry should ensure it is thinking about its public perception in today’s world of chronic underfunding and political populism. There was plenty of popular dissatisfaction with the role banks played in the global financial crisis. And in contrast to periods from the 1960s to the 1980s, “real estate hasn’t really been in the firing lines”, he says.

“Monetary stimulus has escalated asset values. I’m surprised there hasn’t been more political focus on trying to take some of that back for the public. I’m sure that’s coming,” Hobbs says. “Real estate should be on the front foot and saying we’re doing real public good in what we’re doing.”

This returns to the earlier point about inclusive capitalism and the real estate industry’s role in that arena. Writing in IPE Real Assets November/December 2019, Rob Martin, director of research at LGIM Real Assets, says ignoring factors like rising inequality “will create risks for investors”.

“Why is populism a particular concern? By definition, populists reject the status quo. They have little time for consensus building. That has some particular implications for investors,” Martin writes.

“If populism is about ‘us and them’, it is about turning us into them. This is not to suggest we mirror the priorities of populist politicians. But by changing the way we invest, we create a pool of advocates for our sector and underline the risks inherent in disrupting our investment into the built environment.

“This needs to be about more than lip service and PR – there needs to be genuine change. We will need to adapt in ways that are unfamiliar and uncomfortable. How much more difficult will it be to introduce rent controls in the build-to-rent sector if we can demonstrate that rents have not been pushed as hard as the market would have borne to ensure they remain affordable?”

At the group level, Legal & General has been championing inclusive capitalism. And it has been one of the biggest institutional investors to move into affordable housing in the UK. In 2018, it set up a standalone division, Legal & General Affordable Homes, which is aiming to deliver 1,000 new homes this year, a further 2,000 next year and an additional 3,000 in 2022.

Ben Denton, managing director of the new subsidiary and former executive director of Sovereign Housing Association, says that “one of the driving principles” of Legal & General as a whole “is how can we deliver fair returns to shareholders and investors whilst maximising our societal benefit as an organisation”. He says: “That runs right across what the business does. From a philosophical perspective, we think the right long-term decisions for society will, at the end of the day, feed through to the right quality of returns for investors and shareholders. We, as a start-up business in L&G, sit within that thesis.”