#euarchonta

Text

I think most people are aware of the fact that humans are related to other primates such as chimps, gorillas, mandrills and probably even Curious George. As a matter of fact, humans ARE primates, which means we share a common ancestor with all other primates. The order Primate includes many species other than just humans and animals that we usually call "monkeys", it also includes lemurs and some other minor families.

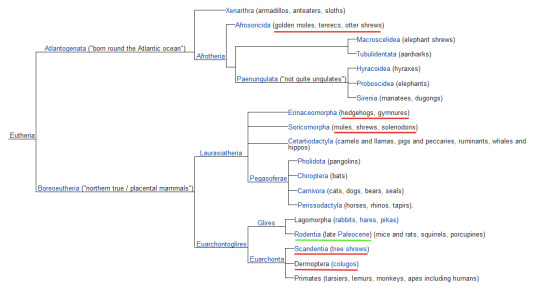

However, what I was curious to know was what animals are the most closely related to humans after the primates. To find out, we need to go up the ranks in our phylogenetic tree. As seen on the image on top, primates are part of the mirorder (like an order, but bigger) Primatomorpha, which includes the order Dermoptera (yes, Greek nerds, this means something along the lines of "wing skin"). The order Dermoptera consists entirely of colugos, which are also known as flying lemurs. Despite their name, they are not lemurs and despite their appearance, they are not flying squirrels. They just happen to also be equipped with a patagium (the skin membrane they use to glide) due to convergent evolution. While this is surely interesting, colugos are quite obscure animals and I was looking for a group of animals that would be more "commonly known", even if a bit less related to humans.

We can go even higher up in our phylogenetic tree and see that Primatomorpha are part of the grandorder (like a mirorder, but even bigger) Euarchonta and have a sister order, Scandentia. Animals in the order Scandentia are referred to as "tree shrews", but again, the name is misleading because while they are indeed arboreal, they are not shrews. The image above has one example of these creatures, a tupaia, and while they are cute and all, they are still not what I would call a "commonly known animal". Also, note that the position of the order Scandentia in the evolutionary tree is actually debatable as some researchers place them as a sister clade* to the Glires.

Going one more rank up in our phylogenetic tree, we see that Euarchonta are part of the superorder (like a grandorder, but bigger, you get the idea) Euarchontoglires, which includes the clade Glires. Within this clade are found the orders Lagomorpha and Rodentia, which are both comprised of very well known animals, such as rabbits and rats. I think it's pretty cool to think that those animals are quite closely related to primates, and therefore, to humans. Probably this is why they are (sadly) used for animal testing of medicine and cosmetics, although they are also probably used because of economical reasons.

* I will one day make a post about this word, it's actually pretty interesting.

#animals#primates#humans#colugo#order#clade#dermoptera#primatomorpha#scandentia#euarchonta#euarchontoglires#glires#phylogenetic tree#phylogeny

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The conversation that I imagine resulted in the naming of the clade "Euarchonta"

"We humans really rule, right? "

"Right."

"The only thing nearly as cool as being human is being able to fly"

"Hell yeah, flying's dope!"

"So I'm gonna name the groupe including us and our closest flying relative "true rulers".

"HELL YEAH!"

0 notes

Text

I think someone put the brain of a mouse or maybe a squirrel inside my head at some point because all winter I was like “I crave nuts and seeds” and now that it’s getting warmer and brighter out my brain keeps going “it’s fruit time”

Like, modern transportation has made it possible to move many fruits all over the world (in theory) all the time! But the primal early plesiadapiform part of my brain is like “you must eat what is available this season”

#I was going to go with euarchonta or plesiadapiform brain but I think the early members of both of those groups were from a tropical#ecosystem. if I’m wrong though and either are from more seasonal environments I could change what I used#actually. wait. plesiadapis is from the late Paleocene. yes. but tropical plants have reproductive cycles too#do they generally vary by season or are they just doing it all at their own pace by species#I am from a very cold seasonal climate that gets hot af in summer but is pretty cold for a good five-ish months#not all equally cold#it’s bad for our environment if it doesn’t get cold as balls for a bit every winter#and we didn’t really get that this winter. but that’s not my point!#I mean to say I can’t remember how it works in tropical environments#if the plants just time their reproduction whenever in the year or if there are seasons for most plants at the same time#does that make sense? I’m using the primate-like-mammal. if it’s wrong then whatever#fuck it we ball#maybe I should have gone with a group further back in time but I couldn’t find climate info easily about things that far back and fuzzier#i am not the most familiar with primate evolution. especially early evolution of the group. I’m open to learning more#i just tend to fixate on certain other things like early mammals and horse and cat evolution#paleontology#emma posts#I like juice all year though#one day I want to try many varieties of fruits that I cannot access easily where I live because they can’t be shipped here#or they just aren’t as popular a variety on an industrial scale#maybe one day i will have a big greenhouse and i will be able to grow the banana varieties I want to try#I can see why some plant varieties aren’t grown on a large scale. some of these bitches are SUPPOSED to be able to grow in zone four but#they refuse to work with me! blueberries make sense. the soil here is nowhere near acidic enough and they would need to be in a pot or#whatever. ya know? but some plants just won’t! or I get them and then the weather here which would NORMALLY work is different that season

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think nearly everything about human behavior can be explained by our evolutionary background. if we observe the entire tree of mammal phylogenetics we can see that the glires clade (rodents and lagomorphs) and euarchonta (primates, colugos and treeshrews) are grouped into one superorder called euarchontoglires, meaning humans are also technically tree dwelling mice as far as semantics are concerned. anyways there are a lot of morphological similarities one can observe between rodents and primates, namely hands, and using those hands to hold onto something like a sunflower seed or a sandwich and nibble on it while sitting in a comfortable spot. like primates the ears, hands and feet of rodents are also relatively hairless, and they are also hypersocial and studies on rats have suggested they feel empathy and will act upon it. in fact a lot of rat behavior resembles human behavior to the point that many behavioral studies are done on them in order to understand the effects/causes of addiction and isolation etc. of course all these traits developed independently but one could argue that A) the basal form that euarchontoglires originated from was already predisposed to these traits or B) already had some or all these traits in varying quantities and other groups like lagomorphs actually lost them. so the homo genus finally developing visual art as one of the culminations of animal creativity/dexterity and immediately using that skill to animate little rodent people wearing clothes and living in societies parallel to our own over and over and over and over until we are sick of seeing them and wondering wtf is going on just makes perfect sense evolutionarily speaking. it was meant to be

200 notes

·

View notes

Text

Common treeshrew

Tupaia glis

Family Tupaiidae, order Scandentia, grandorder Euarchonta, superorder Euarchontoglires

Another tree shrew! This time, one of the more well known ones. It’s one of the larger tree shrews, at an average of 16-21 cm body length and 12-20 cm tail length. The average weight is 190 grams.

They are diurnal and have territories which they frequently mark with scent glands in the chest and scrotum. Territories of males and females will often overlap, while male and male or female and female territories overlap far less often. Territories of two adults with high overlap are thought to be indicative of a stable pair. Juveniles’ territories are thought to overlap with family members until they are grown.

The history of this animal’s classification is very interesting. They were first thought to be in Sorex, with shrews. Their current classification is still not entirely certain.

Because of their close relationship to primates and developed senses of vision and hearing, these guys are used by researchers as animal models for human disease.

@jackalspine @fifiibibii

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aberrant

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Superclass: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Clade: Synapsida

Clade: Mammaliaformes

Class: Mammalia

Subclass: Theria

Clade: Eutheria

Infraclass: Placentalia

Magnorder: Boreoeutheria

Superorder: Euarchontoglires

Grandorder: Euarchonta

Mirorder: Primatomorpha

Order: Primates

Suborder: Haplorhini

Infraorder: Simiiformes

Parvorder: Catarrhini

Superfamily: Hominoidea

Family: Hominidae

Subfamily: Homininae

Tribe: Hominini

Genus: Homo

Species: H. xenos

Common name: Aberrant

Biology/evolution:

Homo xenos, also know as the Aberrant, is a bizarre species found in many parts of Xenogaea. Since there is no ancestral species known from fossil records, with the earliest Aberrant specimen appearing in the fossil record around 30,000 years ago, scientists are unsure of how the creature evolved. Some say that they just highly-derived hominids while others believe that they are mutated humans or perhaps even hybrids between humans and non-human animals. Aberrants are placental, and feed their ifants via the mother's breastmilk. Aberrants live in patriarchal packs, where there is an alpha male. The alpha is easily-distinguished by by his more-prominent and tusk-like fangs, as well as having dark-red, circular markings around his eyes. The alpha gets first picks on everything, from food to mating rights. The alpha is also more-aggressive than his contemporaries, and is highly-territorial when it comes to maintaining his rank. It is not unusual for other males in the pack to be littered with scars from their fights with the alpha.

Description:

Despite being a hominid of close relation to modern humans, it possesses no external ears, lacks any form of body hair, has scaly skin, has eyes on the side of its head rather than at the front, possesses feet more akin to those of non-human primates, possesses long toes, and has back legs somewhat akin to a large cat. It also walks on all fours like other non-human primates. Unlike humans, they cannot speak, and instead communicate in a series of growls, hisses, croaks, barks, and grunts. Their main call is akin to a very-deep bullfrog croak. Their distress call is also eerily similar to human crying. Aberrants possess few teeth, with the only externally-visible ones being their fangs. Aberrants are also deceptively-intelligent, and can learn fast simply by copying things they see humans do. Like humans, they’re sexually-dimorphic: on all fours, males typically stand 3 feet at the shoulder and females around 2.5 feet. On their hind legs, males stand slightly-under 6 feet (due to a slouched posture while standing up) while females stand slightly over 5 feet.

Range and habitat:

Aberrants live across much of Xenogaea, from the mountains all the way down to the desert lowlands. They are quite-hardy animals, being able to survive in extreme conditions that would kill the average human.

Diet:

Aberrants are fairly-opportunistic creatures, and will feed on just about anything that is edible, from carrion to mushrooms. They are even cases where they have been reported to dig up graves to scavenge the corpses inside.

Relationship with humans:

Aberrants have a rather-strained relationship with humans. They are often wrongly-blamed for abducting children and attacking domestic animals, despite Aberrants being a rather-docile species that will, for the most part, leave humans alone so as long humans leave them alone (unless said Aberrant has their young nearby). In Xenogaea, they're referred to in the native language as "Isan-Beba", or "Forest-Baby", due to their distress call sound like human crying. Xenogaean myths also state that the Aberrants were once humans who committed unspeakable sins. And so, the gods cursed them, turning them into monsters. Their scientific name literally means "strange man" in reference to their chimerical appearance.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hedgehogs are not rodents!

Small mammal ≠ rodent.

Unlike another familiar quilled friend, the porcupine, hedgehogs are not rodents. A rodent is any mammal in the order Rodentia. They are characterized by their pair of continuously growing incisors, which has lend them their name: Rodentia comes from the Latin word rodere, “to gnaw”.

Let’s talk teeth!

Rodents don’t have canines, and they have a large gap between their huge incisors and the premolars (most species at least). Those teeth were made for gnawing! And they have to gnaw, because their teeth never stop growing. In some species even the molars and premolars have to be worn down constantly by an appropriate fibrous diet or else they’ll become too long.

While rabbits and hares have similar continuously growing teeth (they have four incisors in the upper jaw instead of two), they’re not rodents but are members of a closely related sister group, the Lagomorpha.

Muskrat skull with a set of seriously impressive incisors. Go big or go home!

(Image source: landofstrange.com)

Most rodents are mainly herbivorous. Very few are exclusively herbivorous though, because they tend to eat the occasional eggs, meat, fish and/or insects as well. This means many rodents including popular pets such as rats and hamsters are actually omnivorous. However, for most of these rodents the majority of their diet still consists of plant matter and I prefer the name “herbivorous omnivore”.

Rodent dentition reflects this, as they do not have canines and the molars tend to be large and well-equipped for grinding fibrous plant matter.

Even less rodents are predators. One of them is the grasshopper mouse, an adorable animal which might be the honey badger of the rodent kingdom. It turns scorpion venom into a painkiller and howls like a wolf. A true badass!

But what about hedgehogs?

If we take a closer look at a hedgehog skull we see something entirely different. We see a mouth full of sharp teeth: large incisors facing forwards, small but pointy canines and (pre)molars. It’s clear these aren’t rodent teeth!

(Image source: viktorjezek.estranky.cz)

What stands out most (especially when viewed from the front) are those large incisors. While rodents have two enlarged incisors placed next to each other, hedgehogs have adorable fangs.

Hedgehogs: secretly vampires

Dentition, as we’ve seen in rodents, can tell us a lot about an animal’s dietary preferences. Hedgehog teeth are very typical for an insectivorous omnivore. Those vampire fangs are great for catching and holding onto squirmy invertebrates. The lower central incisors face forwards instead of upwards to pick up prey. They fit right between the gap of the top incisors.

The front teeth are followed by two more incisors in the top jaw and one more in the lower jaw. After these come the small canines and the premolars, which have sharp cusps made for crunching invertebrate prey.

The third upper premolar is relatively large and pointy, and paired with the first lower molar it mimics the carnassial tooth found in carnivores - a tooth which makes a shearing motion for faster and easier cutting (as opposed to tearing) through flesh. Ideal for eating large insects and the occasional reptile, bird or rodent!

The molars are broad and have relatively low cusps compared to stricter insectivores such as moles. This suggest a more varied, omnivorous diet than just invertebrates.

To put it in other words, hedgehogs are walking trash bins that will eat basically everything that moves. Or doesn’t move. Anymore. While they are primarily insectivorous they are considered opportunistic omnivores (I prefer the term “insectivorous omnivores”), which means they’ll eat whatever is available at that moment with a preference for insects and other invertebrates, carrion, eggs, small reptiles, rodents and birds, and a bit of plant matter (to a certain degree).

But teeth aren’t the only factor playing a part in animals’ dietary preferences. Another big difference between rodents and hedgehogs is the latter not possessing a caecum: the part of the intestine which helps digest cellulose (plant matter). Hedgehogs have an extremely simple gut system and do not digest plant matter well, even though they occasionally eat minor amounts of it. In fact they’re such walking trash bins most of the undigested plant matter found in hedgehog guts and faeces has likely been accidentally ingested.

Okay, so hedgehogs aren’t rodents and they are insectivorous omnivores. But where do they belong on the evolutionary tree?

I won’t go into too much detail or else this will get way too long (like it isn’t already I’m sorry, I like teeth). Just like their dietary preferences, their classification was somewhat of a mess. They were previously grouped in the now defunct wastebasket taxon Insectivora. The requirements to join this group of fun insect-crunching mammals were basically: are you a primitive placental mammal? Do you eat insects? You’re not a rodent? We have no idea what to do with you otherwise? Great, you may now join the Ancient Placental leftovers!

There are still vigorous debates between traditional palaeontologist and molecular phylogeneticists on how the grouping of modern placental mammals should be done, because (short version) there’s still a lot we don’t know but the general consensus, at least as far as the ol’ Insectivora goes, currently favours the molecular phylogeneticists.

The traditional palaeontologists placed the hedgehogs together with several other mammals such as shrews, tenrecs and (golden) moles in the order Insectivora, based on fossil records. Due to the very primitive features of the animals (both living and extinct) that got grouped in Insectivora it was viewed as an evolutionary grade, and early researchers assumed the Insectivora must contain the stock out of which all other placental mammals had evolved.

Cue molecular phylogenetics: by analysing molecular differences, mainly in DNA sequencing, researchers discovered that some of the animals grouped together in Insectivora aren’t even closely related to each other! This meant the entire order had to be split up and re-grouped. They were no longer viewed as the base of placental mammal evolution but got their own separate branches on the evolutionary tree instead. This is the current hypothesis on hedgehog and “Insectivora” evolution.

The family tree of placental mammals based on molecular phylogenetics looks like this. In red underlined are the members of the now defunct Insectivora; the golden moles, elephant shrews and tenrecs got regrouped in Afrotheria while the threeshrews and colugos were placed in Euarchonta.

In Laurasiatheria we find the remaining animals from Insectivora, which are now grouped in Eulipotyphla. The hedgehogs and their closest living relatives, the gymnures or moonrats stick together in their own little family Erinaceidae (formerly the order Erinaceomorpha, which is still the name on the image), and the moles, shrews and solenodons in three other families.

The order Rodentia is underlined in green. As you can see, while they shared a common ancestor millions of years ago rodents and hedgehogs aren’t closely related to each other.

(Image source: wikipedia)

TL;DR hedgehogs are not rodents + fun facts:

Hedgehogs don’t have continuously growing teeth

Hedgehogs do not chew or gnaw on things like a rodent does

Hedgehogs need animal protein to form the bulk of their diet

Hedgehogs need chitin-based fibre in their diet (chitin is found in invertebrate exoskeletons)

Hedgehogs cannot digest cellulose (plant matter) well

Hedgehogs have adorable vampire teeth

Hedgehogs’ closest living relatives are the gymnures aka moonrats (which, despite the confusing name, are not rodents either)

Hedgehogs are also related to shrews, moles and solenodons. None of which are rodents!

Eulipotyphla is the name of their order, which means “truly fat and blind”. These researchers don’t beat about the bush! Although I vote for “truly cute with bad eyesight”.

If you want to know if an animal is a rodent or not, look at its teeth. If it has a mouth full of tiny sharp teeth it definitely isn’t a rodent!

#animals#hedgehogs#rodents#classification#morphology#dentition#teeth#molecular phylogenetics#research#insectivora#placental mammals#hogblr#petblr#rodentblr#long text

366 notes

·

View notes

Photo

È PIÙ SACRO VEDERE CHE CREDERE - STORIA NATURALE

Partire dall’ente materiale per arrivare alla parola viene anche sviluppato, qui in paradiso, in un ulteriore gioco: facendo ricorso alle capacità connettive dell’intelletto e a quelle retoriche della ragione viene costruita una storia, che viene chiamata: storia naturale. In linea di massima, nel gioco, si fa cominciare questa storia naturale dai cosiddetti atomi, e poi si arriva alle creature unicellulari, e poi alle bicellulari e alle pluricellulari, e abbiamo gli eucarioti, alcuni dei quali, i fiori, creano l’ossigeno e i colori, c’è una grande pandemia di ossigeno e di colori, l’ossigeno uccide tutte le creature, ne nascono di nuove, che sono molto felici di essere nate, per via dei colori, i colori piacciano a tutti, tanto che la luce lavora certi organi di queste creature e forma gli occhi, che servono ad ammirare i colori, e, siccome gli occhi sono animati da questa ammirazione per i colori, nascono gli animali, che poi si moltiplicano e si complicano, ognuno secondo il suo modo di ammirare i colori prende una sua particolarità, ma in generale abbiamo gli eumatazoi, i deuterostomi, i chordata, i vertebrata, i gnathostomata, i tetrapodi, i mammalia, i theria, gli eutheria, i euarchontoglires, i euarchonta, i primati, gli haplorrhini, i simiiformi, i catarrhini, gli ominoidi, gli ominidi, e infine l’uomo, e stiamo benissimo, ma poi l’uomo inventa il lavoro, e si divide in antichi egizi, babilonesi, sumeri e cinesi, dolore e infamia e morte, e poi inventa il denaro, e l’uomo si divide in antichi greci, romani, germani, inglesi, francesi, e americani, e ancora più dolore e infamia e morte, e poi si inventa che il denaro compra il denaro, e, allora, a quel punto l’uomo ha davanti a sé due scelte: estinguersi e lasciare che il mondo prosegua eternamente la sua storia senza di lui, oppure fondare saldamente il paradiso.

Le immagini sono le incisioni contenute in “Systema naturae sistens regna tria naturae, in classes et ordines genera et species redacta tabulis aeneis illustrata” trattato di Carlo Linneo (VI edizione, stampata da Kiesewetter Gottfried a Stoccolma nel 1748). Il volume è conservato presso l’Università degli Studi di Pavia, Biblioteca del Dipartimento di Ecologia del territorio. Le immagini, nel dominio pubblico, sono riproduzioni digitali dell'originale, tramite il sito della Biblioteca Europea di Informazione e Cultura (BEIC).

Testo di Pier Paolo Di Mino.

Ricerca iconografica a cura di Veronica Leffe.

https://www.libroazzurro.it/index.php/note/e-piu-sacro-vedere-che-credere/434

0 notes

Note

Are anthracobunids still perissodactyls in Cooper et al. (2014) when the molecular constraint is removed?

Yes, but not in the way you expect. Running it without the molecular constraint leads to some... traditional results. You get traditional Insectivora, Edentata, and paraphyletic Euarchonta.

Desmostylians pop up in Paenungulata, sister to Sirenia and containing Obergfellia and Cambaytherium. However, Paenungulata is within Perissodactyla (horses are closer to paenungulates than to other perissodactyls).

This is why the molecular constraint is important.

1 note

·

View note

Link

0 notes

Text

Do You Love The Colour Of The Sky?

Eukaryote

Orthokaryotes

Neokaryotes

Scotokaryotes

Podiata

Unikonta

Obazoa

Opisthokonta

Holozoa

Filozoa

Animalia

Eumetazoa

ParaHoxozoa

Planulozoa

Bilateria

Nephrozoa

Deuterostomia

Chordata

Olfactores

Craniata

Vertebrata

Gnathostomata

Eugnathostomata

Teleostomi

Euteleostomi

Sarcopterygii

Rhipidistia

Tetrapodomorpha

Eotetrapodiformes

Elpistostegalia

Stegocephalia

Tetrapoda

Reptiliomorpha

Amniota

Synapsida

Eupelycosauria

Sphenacodontia

Sphenacodontoidea

Therapsida

Eutherapsida

Neotherapsida

Theriodontia

Eutheriodontia

Cynodontia

Epicynodontia

Eucynodontia

Probainognathia

Prozostrodontia

Mammaliaformes

Mammalia

Theriiformes

Holotheria

Trechnotheria

Symmetrodonta

Cladotheria

Zatheria

Tribosphenida

Theria

Eutheria

Placentalia

Boreoeutheria

Euarchontoglires

Euarchonta

Primatomorpha

Primates

Haplorhini

Simiiformes

Catarrhini

Hominoidea

Hominidae

Homininae

Hominini

Homo

sapiens

(something might be missing and I know some might be controversial)

0 notes

Photo

Colugos (order Dermoptera) are gliding mammals of Southeast Asia. They are often called flying lemurs, but they aren't true lemurs who are in the order Primates. Only two species exist today, and few fossils specimens can be definitively placed within the order.

Among gliding mammals, colugos are the most efficient, able to glide 230 feet with little loss in height. Their gliding membranes stretch between their limbs and to the tips of their tails. They are the only gliding mammals to have this membrane stretch between their toes, and for this reason, they were once considered closely related to bats. In reality, they are close to Primates within the clade Euarchonta. Despite their heavy adaptations for gliding, they are clumsy in their arboreal habitat, climbing trees in slow hops.

Colugos are shy and nocturnal, and little is known about their daily lives. They are herbivores and likely eat mostly leaves, as evidenced by their long digestive tracts, and probably some fruit. Despite being placental mammals, gestation is remarkably marsupial-like. Young are born highly undeveloped and cling to the mother's stomach and nurse, and the mother uses the membrane of her tail and legs to act as a makeshift pouch.

The leggy colugo showing off its gliding capabilities.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

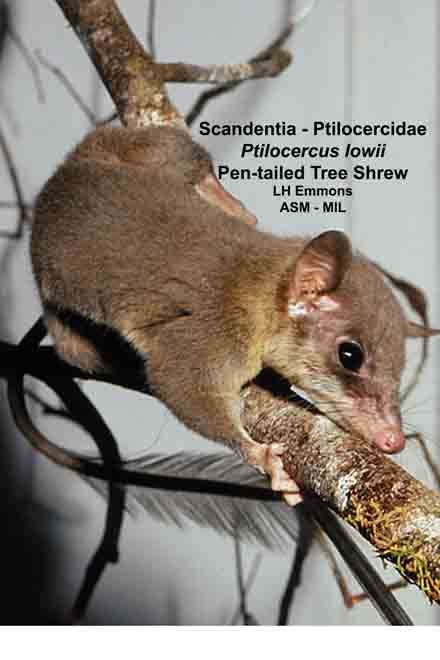

Pen tailed treeshrew

Ptilocercus lowii

Family Ptilocercidae, order Scandentia, grandorder Euarchonta, superorder Euarchontoglires

Only extant member of Ptiloceridae family.

Some of these guys were studied in Malaysia and were observed spend several hours a night ingesting high amounts of fermented nectar from bertam palms. The nectar they consumed has one of the highest alcohol concentrations of all natural foods. They consumed the equivalent of 10–12 glasses of wine adjusted to body weight with an alcohol content up to 3.8%, yet showed no signs of intoxication. It is unknown why they adapted the ability to consume so much alcohol safely.

They are nocturnal and have very different reactions to human disturbances, or likely any disturbances, depending on day or night. At night, they will simply run away. During the day, they will flip on their backs, exposing their bellies, gape their mouths, hiss loudly, and often urinate or defecate.

Their tails are sensitive and wag like a pendulum after aggressive encounters and stand straight up when excited.

They sleep together in groups of 2-5 individuals.

They are related to primates.

@jackalspine @fifiibibii

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's the most basal known genus of primate or stem-primate, Purgatorius aside (since its affinities are in question)? On a side note, when I was trying to find the answer to this question myself, I found out that apparently, they're saying that Euarchonta is no longer valid, but Euarchontoglires still is. Can the family tree get any more tangled?

According to Bloch et al. 2007, Micromyids are the most basal primate-line mammals, Purgatorius aside. They and other “Plesiadapiformes” form a grade leading up to Primates sensu stricto (or Euprimates, according to Bloch et al. 2007; they use a more expansive definition of Primates that includes “Plesiadapiformes”)

2 notes

·

View notes