#is separate from whether the show includes her within its 'in group' of humanity. which thematically it does.

Text

i think there's something to be said about what exactly it means to be "non-human" in a story that is as much about humanity as wolf 359 is, where even the dear listeners are defined less by their own perspective and more by what they fail to understand and therefore reflect about the human perspective - to the point that they don't even have their own voices or faces or identities that aren't either given to them or taken from humans. they speak to humanity as a mirror.

even pryce and cutter are "very much humans" - pryce defined by her resentment of and desire to transcend its limitations, and cutter by his aspirations to redefine and create a "better" type of human - and find the idea that they might not be human laughable. it's interesting that they have distinctly transhumanist aspirations when their goal is the narrative opposite of common science fiction fears: that we will expand the definition of humanity so much that we'll lose whatever it is that makes us human. pryce and cutter's transhumanism narrows the definition of humanity to the worthy and the useful, as defined by them; "there will still be a humanity; it'll just be our humanity."

in direct opposition to that, i think it's meaningful that the show instead expands the definition of humanity in ways that include lovelace and hera, who in another show with different themes might be considered (in the descriptive, non-moralistic sense) non-human. i will always make a point of saying that personhood and humanity are two often-related but meaningfully distinct concepts, especially when talking about sci-fi and fantasy. i am talking about humanity.

the question of how hera identifies, and what social pressures influence that, is a complicated one. i've talked about it before and i will talk about again. what's important for the purposes of this post is that i think the show considers her fundamentally human. think about her role in shut up and listen - consider jacobi's lion example and the concept of different paradigms - that even things that are close to humans, comparatively speaking, understand the world in different ways. whatever differences hera may have from the others, it's primarily in experience, not fundamental understanding. she shares their emotions, their concerns, their values, their thought patterns. she has an appreciation for music, which the show considers a hallmark of humanity. she fits within the framework of humanity as the show defines and is, in her own words, left feeling "uneasy" about how difficult it might be to communicate with beings who don't. and it's significant that this takes place in shut up and listen, of all episodes, specifically because the way she is clearly and unambiguously included in the show's understanding of what it means to be human highlights the ways she and lovelace are othered by eiffel's careless comments that suggest otherwise.

(i don't want to get too into these details for this particular post, but it's worth noting that hera will refer to 'humans' as a category, often when she is upset and feeling isolated, but has never said that she 'isn't human' - she has never been upset that people are treating her 'too' human. i've seen it said about the line "you need to get it through your heads that what goes for you doesn't always go for me", but that's a frustration related to ability and safety, not identity. far more often, she will refer to herself in 'human' terms - referring idiomatically to experiences or body parts etc. that she doesn't literally have - and is upset primarily with comments referring to her status as an AI. it does not diminish how being an AI influences her perspective and experience, but again, so much of that is in terms of ability that it feels almost inseparable from a discussion about disability.)

lovelace's humanity and hera's humanity are so interlinked and directly paralleled in the text that i think it's impossible to really argue one of them is "not" human without making implications about the other. in desperate measures, lovelace tells kepler he's "not human" and he responds "you're hilarious. on a multitude of levels." later, defending lovelace against kepler's repeated dehumanization, hera very pointedly uses the phrase "that woman." in out of the loop, hera says she's never met anyone who "worked so hard at being inhuman" as jacobi, who says "what do you know about being human?" hera very emphatically responds, "i know plenty." later, defending hera against jacobi's repeated dehumanization, minkowski pointedly uses the phrase "that woman." with the care taken towards language and the way scenes and turns of phrase will parallel each other, that's not a coincidence. it might seem strange to have the "non-human" characters be the ones to express criticisms based on perceived "humanity" (something hera will do in other contexts as well - "we don't have funerals for animals" etc.) but in the broader context of the show, i think it's the point.

so, whether hera would ever call herself human, or be comfortable with that, is a complicated question for another time and depends on a lot of other factors. but wolf 359 is a show about humanity, it includes her within its definition of what it means to be human, and i wouldn't be comfortable definitively saying she's not human because of that. it can't be a neutral statement within the particular context of this show.

#wolf 359#w359#hera wolf 359#there are so many concepts here that could be posts on their own#but this is already too long. sorry.#i think it's also worth noting how often i see the discussion of hera and humanity conflated with the discussion of#whether hera would want a body and while i think there's some degree of influence in that. if she has human experiences without human form#there's something uniquely isolating about that that could influence her decision. BUT. the form she exists or doesn't exist in#is separate from whether the show includes her within its 'in group' of humanity. which thematically it does.#hera can be considered equally human without ever having any type of physical form. that's part of expanding the definition#and i think that's an important distinction.#anyway sorry i'm kind of passionate about this it just. doesn't quite sit right with me i guess#in a lot of cases i think it's important to acknowledge that non-human characters have different experiences from human ones and#a lot of science fiction will (or should) decentralize the human experience. but it's core to the themes of wolf 359. it's different.#i think hera is so interesting as a take on the 'human AI' character because. the mistake a lot of them make is having a character#'learn how to be human' and it feels patronizing. but hera is. a fundamentally human person who has been told she isn't#and internalized that. and i think that's much more complex and. well. human. i know she's just a fictional character but#i can't help but feel a little defensive sometimes#it's also part of a larger discussion but feeling inhuman is a not uncommon human experience. it is within those bounds

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everything You Need to Know About Pagan Deity

As you’ve probably guessed by now, there are many, many, many different approaches to deity within the wider pagan community. While it would be impossible to summarize all of these different perspectives in a single blog post, this post contains some common themes and best practices that are more or less universal and can be adapted to fit whatever system you choose to work with.

In my Baby Witch Bootcamp series, I talk about the “Four R’s” of working with spiritual beings, including deities: respect, research, reciprocity, and relationship. However, when it comes to gods and goddesses specifically, I think it’s important to include a fifth “R” — receptivity.

If you’re completely new to this kind of work and want to avoid making rookie mistakes and/or pissing off powerful spiritual forces, sticking to the Five R’s of Deity Relationships is a good place to start. The Five R’s are:

Respect. It’s always a good idea to have a healthy respect for the powers you choose to connect with, whether you see those powers as literal gods and goddesses or as archetypes within the collective unconscious (see below). While not every ritual needs to be incredibly formal and structured, you should always conduct yourself with an air of respect and reverence when connecting with deity. There’s no need to humble yourself to the point of cowering before the gods (and in fact, this kind of behavior is a turnoff for many deities), but you should strive to be polite and follow your system’s proper protocol for things like cleansing, offerings, and prayers.

Research. I am of the opinion that you should do serious research into a god or goddess before any attempt to make contact with them. This can be controversial, but in my own experience things seem to go more smoothly when I know what I’m doing. Books are really the way to go for this — the Internet can be useful for connecting with other worshipers and hearing their stories, but it isn’t a good source for nonbiased factual information. I recommend starting with academic sources written by secular experts for a purely historical account that won’t be colored by personal religious experience. Once you have a decent understanding of the basic historical context, look for books by pagan authors who have experience working with this deity. These sources will give you a framework for your own interactions with them.

Reciprocity. As we’ve discussed before, reciprocity is a core value of virtually every pagan tradition. Reciprocity is a mutual positive exchange where all parties benefit in some way, and this quality forms the backbone of all healthy relationships with deity. While we benefit from connecting with the gods, the gods also benefit from our worship. Upholding reciprocity in your relationships with deity means making regular offerings to show your appreciation as well as living in a way that your god or goddess approves of.

Relationship. At the end of the day, connecting with a god or goddess is about creating a healthy, fulfilling relationship. Like any relationship, it takes time and effort to keep the connection alive. The gods are living, thinking, feeling beings just like you and me, though on a much larger scale. Just like you and me, they have likes and dislikes and require certain things from those who want to work closely with them. Try to approach the gods as individuals, and connect with them as you would with another person. This will naturally lead to much more authentic and organic relationships.

Receptivity. To be receptive is to be open and ready to receive whatever comes your way — this is an essential quality for anyone who is serious about connecting with a god or goddess. Connecting with the gods means allowing them a place in your life, whatever they choose to bring with them. It means forming a relationship with them on their terms, and that requires us to give up a certain degree of control. While you should never feel afraid or completely out of control when connecting with deity (if you do, stop contacting that deity immediately), you may very well experience things you did not expect or ask for. Be prepared for these surprises, and understand that when the gods surprise us in this way, they do it in order to help us grow. Let go of any preconceived ideas about what a relationship with this deity “should” look like, and instead let it unfold naturally.

Though there is much more to working with deity than just these values, keeping these values in mind will get you started out on the right foot in your relationships with the gods.

Deity or Archetype?

As odd as it may sound, not everyone who connects with the gods through study and ritual believes those gods to be literal spiritual beings. Some pagans (I would even say the majority of pagans, based on my personal experience) connect with the gods as individuals with their own personalities and agency, but others connect with them as symbols that represent different elements of the human experience. This latter group is working with the gods not as deity, but as archetypes.

The term “archetype” comes from academia, particularly the fields of psychology and literary analysis. An archetype is a symbol that embodies the fundamental characteristics of a person, thing, or experience.

Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung argued that archetypes are powerful symbols within the collective unconscious (basically an ancestral memory shared by all of humanity) that arise due to shared experiences across cultures. For example, Jung would argue that Demeter, Juno, and Frigg all represent the “Mother” archetype filtered through different cultural lenses, reflecting the important role of mothers across Greek, Roman, and Old Norse culture. For Jung and his followers, archetypes allow us to connect to latent parts of our own psyche — by connecting with the Mother archetype, for example, you can develop motherly qualities like patience, empathy, and nurturing.

For comparative mythology expert Joseph Campbell, archetypes represented types of characters that appear in some form in most or all global mythology. In his book, The Hero of a Thousand Faces, Campbell identified the “hero’s journey” as the archetypal narrative framework on which most stories, from ancient myths to modern films, are based. (If you’ve taken literally any high school literature class, you’re probably familiar with Campbell’s work.) Like Jung, Campbell has been hugely influential on modern pagans who choose to connect with the gods as archetypes.

Working with an archetype is a little different than working with a deity. For one thing, while archetypes may manifest as gods and goddesses, they can also manifest as fictional characters, historical figures, or abstract symbols. Let’s say you want to tap into the Warrior archetype. You could connect with this archetype by working with gods like Mars, Thor, or Heracles — but you could just as easily do so by working with superheroes like Luke Cage or Colossus, literary figures like Ajax or Achilles, or the abstract concepts of strength and honor.

When pagans worship a deity, it’s because they want to form a relationship with that deity for some reason. But when pagans work with an archetype, it’s usually because they want to embody aspects of that archetype. In our above example, you may be trying to connect to the Warrior archetype to gain confidence or become more assertive.

The biggest difference between worshiping a deity and working with an archetype is that a deity is an external force, while an archetype is an internal force. When you connect with a deity, you are connecting with a spiritual being outside of yourself — a being with their own thoughts, feelings, and drives. When you connect with an archetype, you are connecting with a part of your own psyche. Because of this, archetypes tend to be more easily defined and behave in more predictable ways than deities, although some archetypes can be very complex and multi-faceted.

On the surface, worship and archetype work might be very similar, but the “why” behind the action is fundamentally different.

If you choose to worship the Morrigan, for example, you may have an altar dedicated to her, make regular offerings to her, speak with her in meditations and astral journeys, and/or write poetry or make art in her honor. If you choose to work with the Wild Woman archetype, it may look very similar to an outside observer — you may have an altar dedicated to the Wild Woman energy, speak with manifestations of Wild Woman (perhaps including the Morrigan) in meditation, and write poetry or make art dedicated to this archetype. However, these actions will have a very different intent behind them. Your Wild Woman altar is not a sacred space but a visual trigger to help you connect to the Wild Woman within you. Your meditations are conversations with different aspects of your own personality, not with a separate being. Your art is an expression of self, not a devotional act. The result is a deeper connection to yourself, not a relationship with another being.

I hope I’ve made it clear that archetype work and deity worship can both be very worthwhile spiritual practices, and that each serves its own purpose. Many pagans, myself included, work with both deities and archetypes.

There is some overlap between worshiping a deity and working with an archetype, and many pagans start out with one practice before eventually ending up in the other. Sometimes working with an archetype leads you to encounter a deity who embodies that archetype, which can lead to a relationship with that deity. Likewise, your relationship with a deity may help you become aware of a certain archetype’s influence in your life, which might lead you to work with that archetype.

Making First Contact

First impressions are important. This is true for making new friends, for job interviews, for first dates — and for your first meeting with a god or goddess. In many cases, the way you behave in your first meeting with a deity will set the tone for your relationship with them.

That being said, don’t overthink (or over-stress) about your first impression. You aren’t going to be cursed or punished if you mess this up — at the very worst, the deity might lose interest in connecting with you, and even that can often be remedied with an offering and a polite apology. While it’s always best to get off on the right foot, don’t feel like you need to be perfect.

So, how do you make a good first impression on a god or goddess? Honestly, the rules are largely the same for making a good first impression on any other person. Make sure your physical appearance is clean and tidy — some systems, such as Hellenismos and Kemetic paganism, have special rules for cleansing before contacting the gods, but it’s always a good idea to take a shower first and make sure you’re wearing clean clothes. Likewise, make sure the physical space you invite the gods into is relatively clean — it doesn’t need to be spotless, but take a minute to tidy up before beginning any ritual. Be polite — there’s no need to be overly formal, but you should be respectful. Don’t immediately ask for favors — how would you feel if you met someone at a party and they immediately asked you to do some sort of work for them?

Beyond the basics, it’s wise to make sure you have an idea of who this god is and what they are like before you reach out to them. This will keep you from accidentally doing something offensive. For example, you wouldn’t want to invite them to an altar dedicated to a deity they have a rivalry with. Likewise, you want to avoid offering food or drink that would have been taboo in their original worship. (Of course, there are exceptions to every rule, but when you’re just starting out it’s a good idea to follow the historical framework as closely as possible.)

At the risk of sounding like a broken record: this is why research is so important. Knowing who you are dealing with allows you to deal with them respectfully, gracefully, and competently.

Callings

There’s one aspect of deity worship that is controversial in modern paganism: the idea of being “called” by a deity. This is a question you’ll find many, many heated discussions about online. Do you need to be called by a deity to form a relationship with them? Do deities choose their followers, or do we choose them? How do you know what a call from a deity even looks like?

As I said, this is a controversial topic, but I firmly believe that 1.) you do not have to feel called to a deity beyond being interested in them, and 2.) feeling drawn to a deity’s image, symbols, and myths is a form of calling.

Many pagans do feel like they were called or drawn to the deities they walk most closely with. They may have encountered myths of that deity as a child or teenager and deeply resonated with them, or may have always had an affinity for that god’s sacred animals. They may have dreamed of this deity before knowing who they were, or may have felt a spiritual presence around them before identifying it as a god or goddess.

Many people first encounter the gods in fiction, only for this fictionalized depiction to spark a deeper connection that eventually leads to worship. In the modern era, it’s entirely possible for someone who worships Loki to have first encountered him (or at least a character loosely based on him) in Marvel comics and films, or for someone who worships the Greek pantheon to have first discovered them through the Percy Jackson books. As far as I’m concerned, this is also a valid “call” from deity. The gods are very good at communicating with us through the means available — including fiction.

That being said, just because you don’t already feel a strong connection to a god or goddess doesn’t mean you can’t or shouldn’t worship them. The connection will come with time and effort, just like in any relationship.

Dedication, Patrons, and Matrons

In online spaces such as Tumblr and TikTok, a lot of inexperienced pagans parrot the idea that every pagan needs to have a designated matron and/or patron god and/or needs to be formally dedicated to a god in order to have a close relationship with them. Not only is this untrue, but such restrictions can actually cause harm and/or stunt spiritual growth.

Let’s address dedication first. To be dedicated to a deity means to outwardly declare yourself a servant of that deity, usually with a formal dedication ritual — think of it as the pagan version of joining a convent or going to seminary. It is an outward expression of your devotion and loyalty to that deity. Dedicants are held to a higher standard than the average worshiper by themselves, their communities, and the god(s) they have dedicated to.

Dedication can be a powerful and fulfilling spiritual experience (it’s the backbone of many peoples’ spiritual practice), but it should not be taken lightly. Dedicating yourself to a god or goddess should be a sign of your commitment to them and a deepening of your relationship — it should not be the beginning of that relationship.

Dedication is a lot like marriage. Just like you wouldn’t marry someone you’ve only been on a handful of dates with, you shouldn’t dedicate to a deity just because you’ve had one or two positive experiences with them. Like marriages, dedication can be difficult to get out of — ending your dedication to a deity is possible, but it’s a messy, complicated, uncomfortable process that is sure to shift the foundation of your entire spiritual practice, and not always for the better.

My advice to new and inexperienced pagans is not to even consider dedication until you’ve been practicing for several years. As you begin your journey, your focus should be on exploring your options, forming meaningful connections, and developing a practice that works for you and your unique spiritual needs. Now is the time for experimentation, not lifelong commitments.

But let’s say you are an experienced pagan, and you feel like you are ready for dedication. How do you know if you should dedicate to a given god or goddess?

Dedication may be the logical next step in your relationship with a deity if:

This deity has been an active part of your spiritual practice for at least 2-3 years, with no major gaps in contact with them

You are comfortable upholding this deity’s values for the rest of your life — and are willing to face consequences if you fail to do so

You are willing to dedicate a significant amount of time and effort to the service of this deity

You are willing to face major changes in your life outside your spiritual practice — dedicating to a deity often leads to major shifts that may affect our career, family, and/or relationships

If you answered “yes” to all of the above, dedication may be appropriate. This may seem overly cautious, but remember that dedicating to a deity is a serious, lifelong commitment akin to joining the clergy. For context, it takes at least five years of study and practice to become a Catholic priest, a similar amount of time to become a Jewish rabbi, and three years to become a high priest/ess in Traditional Wicca. If you don’t have the patience to maintain a relationship for a few years before dedication, that is probably a good indicator that dedication isn’t for you.

If you are dedicated to a deity or are planning to dedicate, you may actually choose to attend seminary or receive some other formal religious training. This training will help you to better serve your deity in a public capacity, as you will learn skills like religious counselling, leading ritual, and building community. If your program of study includes ordination, it will also allow you to perform legally binding religious rituals like marriage ceremonies. Depending on your path, attending seminary or training may be your act of formal dedication.

Finally, let me make it clear that dedication does not make you a better pagan than someone who is not dedicated. The choice to dedicate or not dedicate is only one element of your spiritual practice, and it is possible to have a fulfilling and life-affirming practice without dedication. Some of the people who do the most work in the service of the gods are not dedicated to them. You may be one of these people, and that is totally okay.

Patron/matron relationships are a specific type of dedication.

The concept of patron deities comes from Wicca and related neopagan religions. As we’ve previously discussed, Wicca is a duotheistic system with a God and Goddess, whose union is the source of all creation. However, because Wiccans believe that all gods are manifestations of the God and all goddesses are manifestations of the Goddess, some covens choose to work with the God and Goddess in the form of other deities (say, for example, Osiris and Isis), which are referred to as the coven’s “patron” and “matron” deities. In these covens, initiation into the coven’s mysteries (traditionally in the form of first, second, and third degree initiations) typically acts as a form of dedication to these deities.

As Eclectic Wicca has gained popularity in the last few decades, there has been a growing trend of individual Wiccans and eclectic pagans choosing personal patron and/or matron deities. Some Wiccans will have a single god or goddess they are dedicated to, while others feel that it is very important to be dedicated to exactly one masculine deity and exactly one feminine deity. This second model is the one I see most often in online pagan spaces, especially Tumblr and TikTok.

The patron/matron model can be useful for some pagans, but it is not one-size-fits-all. As I mentioned, this model of dedication comes from Wicca, and is a very modern concept. In ancient pagan religions, most people would not have been dedicated in this way. That does not mean that this isn’t a valid form of worship (it absolutely is), but it does mean that those who practice reconstructionist paths may not be inclined to interact with deity this way.

The guidelines for patron/matron relationships are similar to the guidelines for dedication in general, but these relationships often (but not always) have a more parental nature. For some people, having a divine mother and/or father figure is ideal — especially for those who are healing from parental trauma or abuse. If you feel drawn to this type of deity relationship, I encourage you to explore it.

On the other hand, you may not have any interest in the patron/matron model, and that’s totally fine! It’s called polytheism for a reason — if you prefer to maintain less formal relationships with many gods, you should feel free to do so.

I hope this post has helped clarify some of the murkier aspects of polytheism and deity work. Obviously, this is only the tip of the iceberg — I could write a book about this topic and many, many authors already have. However, I think the information here is enough to get you started, and I hope that it will provide a first step on your journey with your gods.

Resources:

Wicca for Beginners by Thea Sabin

A Witches’ Bible by Janet and Stewart Farrar

The Spiral Dance by Starhawk

Where the Hawthorn Grows by Morgan Daimler

The Way of Fire and Ice by Ryan Smith

Jessi Huntenburg (YouTuber), “Dancing with Deity | Discovering Gods, Goddesses, and Archetypes,” “Archetype, Deity, and Inviting Transpersonal Experience,” and “10 Ways to Bond with Deity”

Kelly-Ann Maddox (YouTuber), “How to Have Deep Connections with Deities”

#paganism 101#paganism#deity work#dedication#devotional witchcraft#devotional#eclectic pagan#wicca#wiccan#pagan#baby pagan#baby witch#witchblr#witch#witchcraft#religion#theology#goddess#patron god#matron goddess#spiritual#polytheism#witchtok

374 notes

·

View notes

Text

@kurapikawithagun - sorry, i know there’s a lot of text here. but was it one of these?

on second thought, post is way too long, so i edited this with a “keep reading” section. includes excerpts about how “plant collectors followed the Conquistadors”; Spanish and British botanists wanted to “de-territorialize” or “de-anthropologize” knowledge of plants by removing plants from local cultural context, gatekeeping and systematizing knowledge, and subverting local Indigenous/traditional knowledge-holders; creation of Britain’s first botanic gardens including world-famous Kew Gardens were designed to service plantation owners and the East India Company; how 18th/19th-century European naturalists were “agents of empire” who collected “green gold”; how plantations and imperial botanists turned plants from “companions into commodities” and established racial hierarchy; early science of botany functioned as a “teletechnique,” a way for an empire to “act-at-a-distance” on and against colonized lands and peoples; how British military commanders and economists ran the botanic gardens at Calcutta, Madras, and in the Caribbean; how British administrators dismantled local Indian knowledge and land systems by using key legislation in the 1780s/1790s to dispossess people of their lands before compelling those former gardeners to become forced laborers on tea plantations; gardens as part of American nationalist imaginary and “moral improvement” in the 1800s; how native plants and traditional knowledge of Indigenous peoples, Black communities, and the rural poor have been appropriated by “overwhelmingly white metropolitan homeowners” looking for “ecologically friendly ways of aesthetising their properties” in fads of contemporary South Africa; how imperial botany created a “monoculture of knowledge” to overshadow or control a multitude of other local “ecologies of knowledges” and ways-of-knowing; etc.

-------

In a 1998 interview [...], in advance of the release of her third novel, Gardens in the Dunes (1999), Leslie Marmon Silko explains how she became interested in plants: “They come from all over the world, and they’re also another way of looking at colonialism because everywhere the colonials went, the plants came back from there.” [...] Silko confesses that “it wasn’t too long before I realized how very political gardens are …. I had actually stumbled into the most political thing of all – how you grow your food, whether you eat, the fact that the plant collectors followed the Conquistadors.” [...] Gardens revolves around the colonization of indigenous minds and bodies through a variety of processes under the flag of manifest destiny: the loss of land and natural resources in general and the disruption of Native foodways in particular. […] Moreover, it problematizes the privatization of food commons and its negative impacts on local communities from the Gilded Age to the present. […] Silko, a writer of Laguna Pueblo, Mexican, and Anglo-American ancestry, employs the trope of the garden as a means of critiquing and revising modern America’s ecological imperialism, which has attempted to naturalize the conquest of Native lands and foodways. […]

Plant collectors served as what David Mackay calls “agents of empire,” their inventories full of precious and at the time unknown plants and medicinal herbs collected from indigenous peoples that they then shipped to various libraries, museums, and botanic gardens in the Western world. According to historian of science Linda Schiebinger, while “early conquistadors entered the Americas looking for gold and silver,” naturalists, their successors in the eighteenth century, were more interested in “green gold.” Whether they were “voyaging botanists” sponsored by trading companies or sent by the government, the central task of these botanists was to bring valuable plants “all into production within the boundaries of the empire itself.” […] [T]he trope of “I am monarch of all I survey” […]. The power relations between “seeing” and “being seen” suggest that Western science aids the conquest of the Americas by positing a distance between the colonizer and the colonized. […] Collecting, whether via bioprospecting or photography, thus exemplifies the colonial ideology inscribed in Western science that transforms Indigenous peoples and their traditional knowledge into possessable objects and buttresses the structural inequalities that cement the colonizer’s privilege. In her provocative essay on mushrooms as companion species, Anna Tsing has convincingly argued that the plantation system served as “the engine of European expansion” because it was able to produce enormous wealth based on “the superabundance of a single crop” and “cultivation through coercion.” To manage many plantations in colonies more effectively, Europeans eliminated the affective relationship between humans and plants: the labor needed for plantation cultivation was forced through slavery and indentured servitude, a racial hierarchy was created to draw a clear line between white property owner and colored worker, and plants were treated as commodities rather than companions. The legacy of the plantation system, as Tsing puts it, lies in the ways it has shaped the conditions of racial capitalism and environmental exploitation and in the ways it continues to structure “how contemporary agribusiness is organized. […] Commenting on the interrelationship of imperial botany and commerce during the colonial period, Schiebinger explains that “the botanical sciences served the colonial enterprise and were, in turn, structured by it.” Silko’s novel, then, shows how botanical gardens in Europe functioned, in Schiebinger’s language, as “experimental stations for agriculture and way stations for plant acclimatization for domestic and global trade, rare medicaments, and cash crops” against the common view that gardens like the Kew were centrally “intended to delight city dwellers.”

Source: Yeonhaun Kang. “The Garden in Motion: Botanical Exchange and Transnational Collaboration in Leslie Marmon Silko’s Gardens in the Dunes.” 2019.

-------

After numerous false starts, and with the crucial aid of the practical embodied knowledge of the many Chinese gardeners who were literally kidnapped to India together with the tea plants, the Calcutta Botanic Garden and the pre-colonial Saharanpur Garden that was re-developed by the colonial administration, played pivotal roles in the emergence of colonial India as the major producer of tea. The practical knowledge possessed by the initial group of abducted Chinese gardeners eventually fed into incipient botany in the colonial setting. The tea plants transplanted from China to the botanic gardens in India were eventually transplanted to the massive rationalised tea plantations in Assam and parts of South India such as Ooty and the Nilgiris (Sharma 2011; Philip 2004). The lands for these plantations were acquired after the large-scale dispossession of the populations of Assam and Ooty, and the relocation and deployment of the people alienated from their lands as forced labour on the very lands they once possessed and cultivated. The setting up of the colonial botanic gardens, spurred by the crises generated by colonialism, also set in motion multiple transfers and transplants, local and global, of plants, people, culture, agriculture and the eventual transformation of practical knowledge into formal botanical science devoted to [...] production [...] and productivity [...]. These experiments conducted at the Calcutta Botanical Garden also provided institutional and intellectual opportunities for botanical careers for many colonial officials.

Source: Zaheer Baber. “The Plants of Empire: Botanic Gardens, Colonial Power and Botanical Knowledge.” May 2016.

-------

In this conception operating in the eighteenth century, there is no Nature without Empire. […] To “de-anthropologize” the knowledge of plants, also involved “de-locating,” or better still, “de-territorializing” it. Botany was emerging as a science separate from medicine, but also from chorography as territory became a vegetal mantle, a sort of carpet for plants to lie upon. […] Botanical nomenclature was also a matter of political nomenklatura: the exclusion of native names from the field of science defined new power relations. It acknowledged the authority of imperial botanists and belittled local herbalists and herbal practitioners. Nomenclature, indeed, displaced traditional wisdom: Nahuatl came to be considered as an unintelligible, garbled language [...]. This spatial strategy tends to identify certain regions with some characteristic species. This allowed a selective fostering of farms and forestry in those areas rich in species of particular interest to the Spanish Crown. Plants ceased to be the business of experts and became the concern of politicians. Botany came to strengthen imperial politics. [...] The plants themselves and not their products became the stuff of trade, and what circulated through the networks were ideas on how to mobilize species and how to denature them. Botany began as atechnoscope – a way to visualize at-a-distance – but, at the end of the eighteenth century, it was already a teletechnique – a way to act at-a-distance. Its success as an imperial undertaking was linked to the ability to set up an international network of professorships, gardens, expeditions and publishing companies able to produce aversion of Nature easily put into words, and deducible from very little data. […]

Source: Antonio Lafuente and Nuria Valverde. “Linnaen Botany and Spanish Imperial Biopolitics”. 2011.

-------

“’These are my conquests,” Josephine, wife of Napoleon Bonaparte, is reported to have said of the roses and lilies in her renowned garden showcase,” Bennett writes. […] “She would spend as much as 3000 francs on a single rare bulb […].” Gardens are “the most political thing of all – how you grow your food, whether you ear, the fact that the plant collectors followed the Conquistadors,” Leslie Marmon Silko told Ellen Arnold on the eve of the publication of Gardens in the Dunes [1999]. “You have the Conquistadors, the missionaries, and right with them were the plant collectors.” […] In Gardens, Silko uses the image of the garden to illustrate imperialism on international, national, local, and domestic levels. […] Silko offers a microcosmic history of ancient conquest, European imperialism, and modern botanical piracy, while demonstrating commercial trivialization of the sacred. […] The gardens […] exemplify America’s nineteenth-century gardening ideologies. In his 1782 Letters from an American Farmer, Hector St. John de Crevecoeur wrote of the spiritual benefits of agricultural labor. By the mid-nineteenth century, this idea had evolved into gardening as a form of moral calisthenics. […] According to historian Tamara Plakins Thornton, in the 1820s “[h]orticulture entered the mainstream of American life … as a movement [that] promised … moral benefits to an entire nation.” […] Further, by the 1890s, thanks to the early-nineteenth-century efforts of America’s premier landscape gardener, A.J. Downing, and, later, British gardening authority Gertrude Jekyll, landscape gardening had achieved the status of a fine art (Thornton; Bisgrove). It was in 1893 that historian Frederick Jackson Turner announced that the American frontier was “closed.” With […] Native peoples more or less incarcerated [...], the American landscape garden provided a blank canvas on which the gardener could impose control and exercise her fine art […].

Source: Terre Ryan. “The Nineteenth-Century Garden: Imperialism, Subsistence, and Subversion in Leslie Marmon Silko’s Gardens in the Dunes.” Studies in American Indian Literatures. Fall 2007.

-------

Many colonial administrators were of course active in mobilising the tremendous economic potential of plants in the imperial project. At the same time however, there were many others who, although they were key actors in the colonial project, were also specifically interested in enhancing their cultural and intellectual capital by becoming “scientists.” [...] The British Empire, as well as the other European empires of that period, constituted one of the many institutional crucibles in which the sciences of plants literally germinated, took root and flowered. Plants constituted an integral element of colonial power [...]. This goal of setting up a rationalised system of administration and revenue collection was a major impetus behind the “great surveys” initiated by the East India Company. [...] The company officials were also familiar with the existence of a pre-colonial Botanical Garden in Saharanpur in northern India (Hyde 1962) and of course Kew Gardens in London, even though the latter was set up primarily for the cultivation of medicinal plants and had not as yet emerged as the major scientific institution that it would become later. The company had also set up smaller gardens in St Vincent in the West Indies for the transfer of the breadfruit tree from Tahiti to provide, in the words of the President of the Royal Society, Joseph Banks, “food for slaves” (Mackay 1985, 127). In the context of a dramatically transformed Indian social structure coupled with serious concerns over the erosion of the legitimacy of their rule in the eyes of their Indian subjects, officials of the company were extremely receptive to the idea of a major botanical garden and its potential for restoring stable revenues. […] In less than four years after Kyd’s original letter of 1786, generous grants from the Court of Directors in London made possible the establishment of the first modern Botanical Gardens in Calcutta, Madras and Bombay, as well as in distant St Helena. […] Unsurprisingly, the first superintendent of the Calcutta Botanic Gardens was Lieutenant-Colonel Kyd himself and the plants that were transplanted there from Southeast Asia were exclusively those that were essential for trade and competition with other colonial powers (Burkill 1959). These included cinnamon, coffee and black pepper. [...] In the same vein, the Bombay Botanic Garden was established due to the initiative of Dr Helenus Scott – a friend of Banks, President of the Royal Society – with the express aim of conducting botanical experiments for the cultivation of sugar, indigo, tobacco, coffee and more.

Source: Zaheer Baber. “The Plants of Empire: Botanic Gardens, Colonial Power and Botanical Knowledge.” May 2016.

-------

Imifino is the collective noun isiZulu speakers in KwaZulu-Natal use when referring to auto-propagating leafy green vegetables that have a penchant for thriving in marginal soil. As interest in indigenous plants has grown, these vegetables – long an unheralded staple of the rural poor – are now at the centre of state and scientific attention. Plans are afoot to codify, patent, and popularise ‘indigenous knowledges’ for a variety of ends: the enhancement of national competitiveness; revalorisation of indigeneity; pursuit of food security; and of course the stimulation of profit-making. […] Subsistence cultivators, however, are not alone in cultivating indigenous flora. About three hours south, in the city of Durban (and throughout South Africa) something called ‘indigenous gardening’ has gained popularity since the end of formal apartheid. As we elaborate later, ‘indigenous gardening’ is a name reserved for a specialised field of activity, a metropolitan affair practised by conservationists, botanists, real estate developers, horticulturalists, architects, and enjoyed by mostly white upper class homeowners for a variety of purposes, especially those associated with conservation. It is sanctioned by science and other kinds of credentialed expertise, and geared towards enabling overwhelmingly white metropolitan home owners to pursue ecologically friendly ways of aesthetising their properties, rather than towards matters of subsistence undertaken by those deemed the black rural poor. From the vantage point of our conversations with subsistence cultivators like Gogo Qho, we wonder, ‘Why do overwhelmingly white metropolitan homeowners specifically want indigenous plants to adorn their properties? What kind of desire for indigeneity is being pursued here? What is Indigenous about Indigenous gardening other than plants?’ […]

Source: Narendran Kumarakulasingam and Mvuselelo Ngcoya, “Plant Provocations: Botanical Indigeneity and (De)colonial Imaginations.” 2016.

-------

Landscapes and vegetation are not simply the backdrop against which violence and dispossession unfold, but are mobilised as the very medium of violence [...]. Key here is the space of the garden, in multiple ways. Gardens in the Western imagination often have utopian, pre-lapsarian associations, but are in fact riven with ambivalences that stem from questions concerning who is displaced in order to demarcate their boundaries, and whose labour is exploited to maintain them as sites of nourishment and enjoyment. [...] As such, the colonised subjects remain cast out of the [...] garden of earthly delights, even if its is precisely through their knowledge and labour that the actual garden feeds and sustains the symbolic garden -- notably, the plantation system [...]. In the context of imperial botany the space of the garden was vital, with the frontrunners of the modern scientific botanic garden, which were established in sixteenth-century Italy, combining ‘the scientific ideal of comprehending universal nature’ [...] ‘by gathering together all the creations scattered at the fall of man.’ As such, the botanical garden can be understood as a laboratory of empire, as can tropical island colonies (also incubators for the revival of European Edenic dis/course) and the space of the plantation more broadly. Moreover, the construction of the category of the ‘damnes’ of the earth needs to be read in the context of this wholesale classification of forms of life enacted by imperial science. Notable botanists such as Linnaeus, as well as Hans Sloane and Joseph Banks, were influential in the development of scientific racism, as well as the endorsement of slavery and colonisation of foreign territories. Colonial natural science [...] was central in the construction of race and sexuality [...]. By and large, imperial science (what we might call a ‘monoculture of knowledge’) excluded other, ‘minor’ histories and systems of knowledge (’ecologies of knowledges’), as well as modes of being-in-the-world that are not premised upon the value, profitability and usefulness of plants [...].

Source: Ros Gray and Shela Sheikh. “Introduction” to The Wretched Earth: Botanical Conflicts and Artistic Interventions. Third Text. 2018.

254 notes

·

View notes

Text

Infinity Train and Cults

One of the most interesting aspects in Infinity Train's story is how humans passengers start cults and the process of recruitment. This theme is very prevelent during the second half of Book 2 and all Book 3.

This theme is represented with "The Apex": a group commopsed of very young passengers who go from car to car harrassing citizens of the train and stealing their goods. They are first introduced in the series in the episode "The Lucky Cat Car" in Book 2.

In this post i'm going to write a detailed analysis explaining what is a cult, why the Apex could be considered a cult and the reasons why passengers would join the group in first place.

To do this i'm going to cite a few sources about cults and the psychology behind cult recruitment, which you'll find at the end of this post.

Let's start:

1) The definition of the word "Cult".

According to Sociologist Janja Lalich who speciales in cults the definition of a cult is:

¨A cult can be either a sharply-bounded social group or a diffusely-bounded social movement held together through shared commitment to a charismatic leader. It upholds a transcendent belief system (often but not always religious in nature) that includes a call for a personal transformation. It also requires a high level of personal commitment from its members in words and deeds.¨

Another details she talks about in her article are:

¨This definition is not meant to be evaluative in the sense of implying that a group is good, bad, benign, or harmful. Rather it is meant to convey a systemic view of such a group, which is comprised of a charismatic relationship, a promise of fulfillment, and a methodology by which to achieve it.¨

¨Each group must be observed and judged on its own merits and its own practices and behaviors as to whether it falls within this category type, which is not meant to be dismissive or one-sided¨

The Ted-Ed video: ¨Why Do People Join Cults?¨ gives a similar definition:

¨Broadly speaking, a cult is a group or movement with a shared commitment to a usually extreme ideology that's typically embodied in a charismatic leader. A typical cult requires a high level of commitment from its members and maintains a strict hierarchy, separating unsuspecting supporters and recruits from the inner workings. It claims to provide answers to life's biggest questions through its doctrine, along with the required recipe for change that shapes a new member into a true believer.¨

To put it in simpler words: A cult by definition is a social group which has a very strong belief system (this doesn´t mean it is religious), it’s controlled by a charismatic leader whose followers rarely question. The members of the group have to obey an specific set of rules that are usually created by the leaders of the cult. Critical thinking is very often discouraged between the members.

The word cult isn´t meant to be good or bad. It’s just a way to describe a social group with specific characteristics. The definition itself isn´t exact, one has to learn about the group first before labeling it as a cult.

Now, how do the Apex from Infinity Train fall in this category?

2) The Apex as a cult.

For this part of the analysis I’m going to cite common characteristics of cults and how they do apply to the Apex. I’m going to add multiple examples of how the Apex members behave, how they interact with their leaders (Grace and Simon) and their ideology.

¨The group displays an excessively zealous and unquestioning commitment to its leader, and (whether he is alive or dead) regards his belief system, ideology, and practices as the Truth, as law.¨

In the series, the Apex members consider Grace and Simon as unquestionable leaders. They follow their commands including those that are indicate to hurt train citiziens.

When Grace snaps her fingers in one of the kids immediately listens to her and goes to her side, kneeling when he meets her. (The Lucky Cat Car).

Simon also kneels before Grace in next episode since he is supposed to be second in command.

In ¨The Music Car¨ all the members pledge to the leaders and salute them:

¨Apex!

May our spirits be high!

And our numbers higher!

Down with the false Conductor!¨

Both Grace and Simon appear to have a special status within the group as they are given gifts by the kids when the raid a car as seen in the first episode. It’s not stated if this is part of their routine as way for each member to prove they are worthy of being a Apex but considering the rules of the group it is very possible assumption.

¨Questioning, doubt, and dissent are discouraged or even punished.¨

In ¨The Mall Car¨ after Jesse refuses to follow Grace orders and stands up for Lake and Alan, Grace responds by telling him he made a big mistake and uses her mirror to let the flecks catch Lake.

This is a huge contrast with how she was very friendly with Jesse at the start of the episode. Grace´s sudden change of behavior comes from how Jesse didn´t accept her authority and realized how he was being manipulated.

This is another example of The Apex behaving as a cult: In the moment someone doesn´t want to follow Grace or Simon´s orders, they are seen as an enemy who opposes the Apex and there before must be punished. Disagreement is very discouraged in cults groups. Those who show any sign of disagreement or doubt are mocked, guilt tripped and called out.

A more subtle case of this happening when one of the kids,Lucy, calls a train citizen a ¨person¨. Grace corrects him by telling him that the train citizen is ¨another toy the train made to amuse us.¨ She makes Lucy feel ashamed for doubting the Apex ideology by mocking her in front of Simon: ¨Aw, that's cute. Lucy thinks it's a person¨ (The Music Car).

¨The group is elitist, claiming a special, exalted status for itself, its leader(s), and its members (e.g., the leader is considered the Messiah, a special being, an avatar—or the group and/or the leader is on a special mission to save humanity.¨

The Apex believe that they are entitled to their car. They are above the train citizens, they are allowed to take and hurt them as much as they want because for the Apex the citizens aren’t real and they don’t experience emotions.

¨She doesn't even have a number. (..) ¨She's not a passenger¨.(..) Exactly, she's a null. Null, it means nothing, not even a zero.¨ Grace talking about Lake in ¨The Mall Car¨

¨I've got a number, and you don't. You two are only as good as you are useful.¨ Simon referring to Alan Dracula and Lake.

The group itself refers to the old conductor as their as divine figure, who inspires them everyday and has been stolen from his true place by the ¨false conductor¨, who is One-One. It’s almost as the old conductor is their god because it has the highest number in the train.

Grace mentions multiple times in Book 3 how she was saved by the conductor. It´s heavily implied she believes she has been chosen and how she´s the only one that who knows how the conductor looks like.

In Apex ideology, the numbers are very important: They determine your status in the community. The higher the number, the more powerful you are. To increase your number you have to do the tasks the leaders give to you. These tasks involve destroying, stealing and hurting citizens. The person with the highest number is the leader of the group.

¨The group teaches or implies that its supposedly exalted ends justify whatever means it deems necessary. This may result in members participating in behaviors or activities they would have considered reprehensible or unethical before joining the group¨

While wrecking the car in the episode ¨The Lucky Cat Car¨ Grace mentions how the Apex are just doing what they must to survive. This shows a very explicit example of ¨the the end justify the means¨ that is common to find in cults. Grace and the other Apex kids are clear they don´t care about stealing and hurting citizens as long as they are able to increase their numbers and get resources.

Another example of this is when Grace and Simon plan to getting rid of Tuba to take Hazel with them in Book 3. This implies they don’t care about separating kids from their train companions to make them join the Apex. It wouldn´t be farfetched to think they have done this before with other young passengers to isolate them and persuade them into staying with the group.

In case of Jesse in Book 2, Grace tries to convince him to participate in a raid by breaking a cube from a train car. She tries making Jesse believe that those without numbers aren´t real and lack capacity to experience actual pain. Before that she told him to throw food under the train by saying he is ¨free to do whatever he wants¨. This case is more about how members make non-members commit morally questionable actions before they become full members.

¨Subservience to the leader or group requires members to cut ties with family and friends, and radically alter the personal goals and activities they had before joining the group.¨

Very often when joining a cult members are asked to keep distance from their close relationships (family and friends). Applying different methods, the leaders seek to isolate the new members from their family to control them more easily and thus making doubt less of the orders they are following.

In Infinity Train, the apex often try to separate kids and teenagers from their train companions. To do this, they manipulate the passengers into believing that their companions are just ¨toys to play with¨ and that the Apex are going to give them a home to live.

In ¨The Mall Car¨ Grace asks Lake to stay to look for Alan Dracula while Jesse goes with the Apex kids. Grace did this on purpose to be alone with Jesse and cause problems between him and Lake’s relationship.

After Lake stays behind, Grace starts talking about how Lake is getting Jesse into trouble and how the train is a ¨scary and lonely place¨. By giving Jesse all these negative thoughts she intends to giving him more reasons to not continue his journey and be part of the group.

In Book 3, Grace and Simon try applying something similar with Hazel and Tuba. They try to make Hazel to leave Tuba’s side and getting rid of the citizen. Much like Lake and Jesse, Tuba and Habel have a very strong bond which means they are going to have a hard time encouraging Hazel to ditch her friend.

One detail worth of adding is that they considered Tuba a threat because of her huge muscular form which made her look really intimidating. Someone like her was a obstacle that was impeding them to recruit Hazel.

¨Unreasonable fear about the outside world, such as impending catastrophe, evil conspiracies and persecutions.¨

The Apex believe there was a conspiracy against the old conductor and the new conductor (One-One) is the false conductor. They seem to hold into this idea that old conductor was overthrown and their true place is being in charge the train.

When Amelia is explaining them that she used to be the old conductor and she isn´t prisoner of One-On, Simon keeps accusing her of spreading false propaganda and insist Grace that she is trying to trick them. In this scenario, it makes some sense for someone to be skeptical, especially if they held a very strong belief system like Grace and Simon do.

3) Why would passengers join the Apex?

After watching how badly the apex treat the train citizens and separate kids from their companions, why would someone join them? It may look like only those who want to commit vandalism and have a extreme prejudice against citizens would but if one analyses how the train operates it makes perfect sense.

When a kid gets on the train, they are completely separated from their family. Unless they find a kind companion, they are going to be completely alone stuck in a unknown place without adults to take care of them. They are very likely going to feel lost and scared not knowing what they have to do and what they should go.

Combine all this factors and they make a very easy target for a cult movement like the Apex to recruit: The members can take care of them, give them a place to belong, have friends and a sense of community. The kid passengers don’t have to worry about anything as long as the follow the rules.

Cults seeks to recruit people who are in a state of extreme vulnerability, who have issues fitting in or may feel lost. The members give these people a new purpose. They say ¨we can be your new home, your family¨ which leads to people to be persuaded into joining.

In the two examples in the series, Hazel and Jesse, Grace talks to them about how great the Apex are: They are going to help them, they will take care of them and keep them safe from the dangers of the train.

With Jesse, Grace tells him ¨how she cares about people¨. She fills his mind with how the Apex are good and they can do whatever they one. She’s very friendly with him and even invites him to jump from car to car.

In the case of Hazel, Grace tells her how they are going to help her with fixing her number. She also mentions how Hazel is going to meet tons of other kids once they reach the Apex car.

She knows that kids like Jesse and Hazel feel confused inside the train and takes advantage of their weaknesses to trick them into becoming Apex members.

In Conclusion:

For the reasons I wrote in this post, one could interpret the Apex from Infinity Train as a cult or a social group that shares characteristics found in cults : They have a very specific type of almost religious ideology, they think having more numbers gives them a special status, they rarely have doubts in their leaders and don´t care about hurting people to get what they want.

I think that the Apex is one of the most interesting themes of the series. It explores what happens when many young passengers start working together and create their own society with its own rules while showing how people come together when they find themselves lost in a place they don´t understand. It’s worth of analyzing the psychological and sociological aspects of this community and how they work.

Sources that were used for this post:

http://cultresearch.org/help/characteristics-associated-with-cults/

http://cultresearch.org/definition-and-explanation-of-the-word-cult/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Janja_Lalich

https://www.insider.com/why-people-join-cults-according-to-therapist-who-treats-survivors-2020-9

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/belief/2009/may/27/cults-definition-religion

The video ¨Why do people join cults?¨:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kB-dJaCXAxA&ab_channel=TED-Ed

#infinity train#infinity train season 3#infinity train season 2#infinity train grace#infinity train simon#it analysis#cults#Animation

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Rough Moral Overview of Archie Comics: Teen Propaganda Machine

Part 1: The 1940s

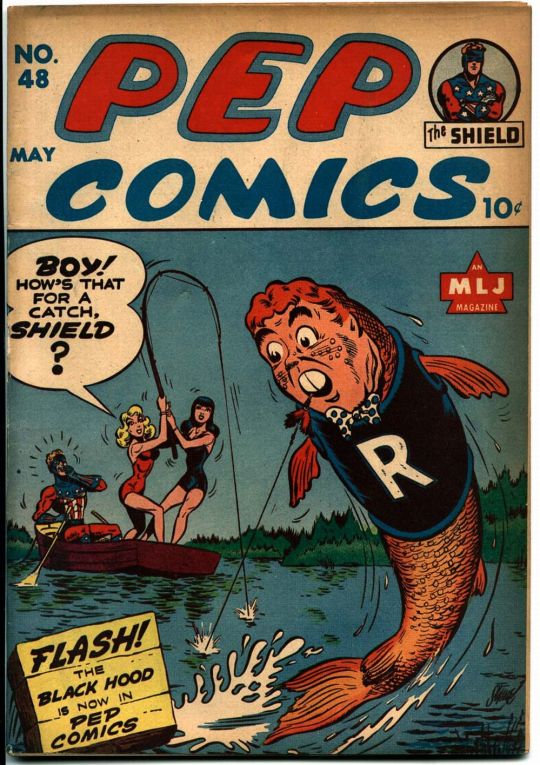

1941: Archie first appears in a small feature near the end of PEP Comics #22. His popularity builds rapidly, with the audience apparently writing in to express immense interest in the short monthly Archie comic.

At first the Archie story isn’t even mentioned on the cover, but Archie himself slowly starts appearing on the cover, always with PEP’s big star at the time, The Shield. The Shield on the cover is at first much larger than Archie, but he shrinks over time, and after Veronica’s introduction, she and Betty start to feature on covers as well. The Shield continues shrinking...

And by issue #49, the magazine is PEP Comics: Starring Archie Andrews! Archie quickly becomes its own imprint, and the only one of PEP’s lineup that survives into the present day. Ads in the magazine advertise an Archie radio show that was spurred by what was a apparently a massive outpouring of interest from PEP’s teenage subscribers. The concept of teenagerhood itself was a new invention dating from 1944. Archie’s reality included things like school, dating, and modern teen problems like trying to maintain a car and deal with wartime rationing.

Also, sending your dog to fight Nazis. (Note: the above are two separate stories; no Nazis ever actually invaded Riverdale. Oscar, Archie’s dog, gave birth on at least two occasions, including during her army tour, and eventually faded from existence.)

At this stage, minstrel-style caricatures of black men appear on occasion in Riverdale (as train attendants and no-account bums who steal clothing out of the trash), and Yellow Peril-style caricatures of Japanese people are a regular fixture in other PEP features like “Captain Commando and the Boy Soldiers”. As a side note, Chinese people are depicted quite differently in Captain Commando. At this point in US history, they were seen as important potential allies in the war against the Japanese. In Captain Commando, they’re drawn like actual humans in comparison to Japanese soldiers. One story shows a Chinese warrior who’s been bamboozled by foolish Buddhist ideals of peace, but finally snaps out of it and gets his followers to join up with US forces in resisting Japanese occupiers. Chinese-Americans were depicted less frequently, but also running in PEP for a time was a rather remarkable depiction (for the time) of a Chinese-American hero: Fu Chang, International Detective. Chinese people would later be collapsed into the Yellow Peril phenomenon in US pop culture and there were some very racist depictions within Archie Comics, but in the 40s there was a different perspective on display for a while.

(Captain Commando and his Boy Soldiers have since lapsed into the public domain; evidently the heroic quality of child soldiers lost its gleam after WWII and reviving the property was never deemed profitable.)

Also in the 40s, many, many stories end with a quite literal punchline in which Archie gets taken out to the woodshed and beaten by his father for causing trouble. This was PEP’s light-hearted humorous fare that apparently spoke quite deeply to a teenage audience of this era. The depiction of corporal punishment is neither “pro” nor “anti”, it’s simply an unavoidable consequence handed down from on high. Archie’s misadventures lead inevitably to physical punishment from an authority figure, no matter how much or how little he’s to blame for things going wrong. Mr. Andrews himself is sometimes a figure of fun during this period, but the 40s and 50s are the time when he most often feels like a self-insert for the writers and artists, who would have been closer to his position in life than Archie’s.

Archie’s position, though, isn’t entirely as the object of abuse. It’s pretty safe to assume that the writers and artists also grew up with corporal punishment and can sympathize with the experience--though they’ve now entered the stage of life where they understand that it was done only for their own good. Archie at the end of these stories is both resentful and rueful; he wishes it hadn’t happened, but there’s no room in the pages of PEP to contemplate a world where it doesn’t have to.

Violence was much more accepted in the 40s, including against the girls themselves--for their own good, in this case, but it’s still jarring to see a man give Betty and Veronica black eyes. Their crime in this case was, of course, being so silly and man-crazy that they nearly drowned him and themselves.

Often the violence was more cartoonish in nature, but it was only in the 40s that you’d see Betty showing up at Veronica’s door with Moe Szyslak’s weapon of choice.

The porter in this panel is one of the kindest portrayals of a black man in this period; the others (and the one depiction of a black woman that I noticed) are frankly unreproducible without heavy content warnings. Also in the 40s, fat and/or ugly women exist only as an object of fun or outright cruelty.

Vague “reducing plans” were advertised in the pages of Archie in the 1940s. This particular method was, as the name suggests, seaweed pills that were also marketed as chewing gum.

You may notice in some stories that the “ugly” and undesirable woman has very nearly the same face as Archie himself; the irony here is very likely unintentional. It’s rarely (seriously) suggested that there’s anything morally wrong with Archie aspiring to a girl much prettier than he is, but an ugly girl expressing interest in any boy is a figure of fun right up into... well, the present day. The Gabby pictured in the panel above her was a semi-recurring character, one of the only plus-size recurring characters ever depicted in Archie. As her name suggests, she was a gossip and one of the undesirable girls, but she was sometimes allowed to be friendly with Veronica or Betty without immediate karmic punishment. She’s also notable because she’s not only one of the only plus-size characters, she’s one of the very few plus-size female or teenage characters. Mr. Andrews, Mr. Weatherbee and Pop Tate all survived the 40s, but Gabby didn’t.

Betty at the inception of “Archie” (the comic) was just Girl. She rather liked Archie and he liked her, and he would try to impress/date her but end up having his monthly funny adventure. But only once Veronica was introduced did she start to gain more dimension, this time as Other Girl. Veronica was rather nice to begin with and it took a short while for them to start getting played off each other as “characters”. There was still little difference. Veronica was always rich and as a result became snooty fairly quickly, but her flaws were the flaws of an object. They existed to create difficulties for Archie, in his struggle to impress her, and Betty was differentiated only by not being snooty.

When Betty and Veronica were allies, it was because Archie had blown it somehow, and they were naturally compelled to be allies by virtue of both being girls. (When they didn’t like each other, it was also because they were both girls, and such was the natural state of being girls.) The panel above--both in the same pose, their identical faces lifted in scorn towards all men--would be echoed in other later stories, whether by chance or by accident.

Their posing in the 40s was frankly pretty ludicrous and transparent in its intentions.

Sexual attraction wasn’t explicitly commented on in the 40s comics in the way we understand “explicit” today, but it’s allowed to exist more openly than in later years. The va-va-voom effect highlighting the breasts would have to become more euphemistic as the decades passed.

In general, there was very little pretense in the 40s.

Artists had no qualms about showing the girls nearly in the nude (I cropped out a panel of Veronica in the bath above), nor about showing adult men leering at them. Even Mr. Weatherbee was occasionally moved by their charms. Generally adult men were “punished” for showing visible attraction, but only in humorous ways. It was more common for the teenage boys to drool over the girls, but the only disapproval shown when grown men did it came from women their own age, playing the role of scold or prudish spinster. There was also the occasional gag in which an adult man was misunderstood as a “masher” or peeper and received undeserved punishment from the supposed target.

There were various write-ups of celebrity activity in the 40s and 50s, and there too the attitudes towards women were pretty much what you’d expect, but even in the late 1940s the realities of life were not entirely veiled from teenage eyes. There was room for what would now be considered adult jokes.

Also in the 40s, Archie cross-dressed, like, a lot, in a way that noticeably vanished once the 50s rolls around. It’s always as a gag, and it’s usually noted that he makes an ugly girl, but in this era it seems to have been an idea that could be poked fun at without threatening the moral fiber of all America by the mere suggestion.

In fact, one semi-famous 1948 story, “The Battle of the Jitterbugs” (reproduced more fully elsewhere) revolves entirely around the girls and the boys competing in a “fair contest’ to see which sex is better at dancing--since boys only lead and girls only follow, it’s impossible to determine who can dance better overall. The obvious solution is for two girls to dance with each other and two boys to dance with each other.

Crucially, the idea is suggested by Reggie, the prankster of the group, framing it as a joke from its inception. Archie, the main character, follows through with it as a means of asserting male superiority. There’s also no possibility that two boys could dance, or two girls could dance, without the conceit of one performing the role of the opposite gender. But in practice, the whole thing does involve a lengthy depiction of two boys dancing together, and indeed, jokingly flirting with each other.

Again, the joke-flirting comes in the form of mocking from Reggie, both en femme and en homme. Archie, the protagonist and everyman, is uncomfortable throughout and finally throws Reggie right out Pop Tate’s door after Reggie goes too far in impugning his masculinity.

At this stage, the usual band of crones step in to punish him for imagined crimes against women, and he finishes the story sitting in bed with a broken leg, making a pronouncement that stands out rather sharply to the modern eye: “Confidentially, Jug! I’m no longer interested in women... or dancing!”

Veronica and Betty are significantly more comfortable with each other. In fact, it’s a rare 1940s story where they don’t quarrel with each other at all! Veronica’s femininity is seemingly unthreatened by the hat and pants, even though Archie Comics would continue issuing dire warnings against women in pants up through the mid-1970s.

It’s hard to imagine they lost after this! The tone of this page is downright celebratory, a rare occasion of early Betty and Veronica working together and coming out the victors of the story, not by one of them winning Archie, but by both of them showing their own skill at something without trying to show the other up. “Battle of the Jitterbugs” is a true rarity in these early years, a depiction of female triumph that doesn’t exactly defy the era’s pop culture as a whole--women were creating their own art even in the 1940s--but it does defy nearly every other Archie story up to the mid-1970s.

#archie comics#archieganda#i couldn't possibly put enough content warnings on this#content warning just about everything

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

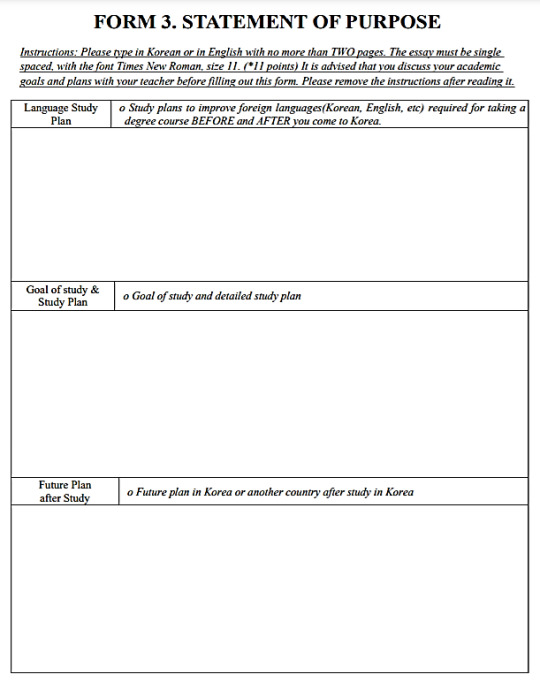

A Journey to KGSP/GKS: Study Plan

After a very long while, I finally managed to post this! This, I guess is my final post on A Journey to KGSP/GKS Series. I’m still considering whether or not to make a post about the interview. I’m not sure I can cover this topic well since my experience is limited to the interview session in the Korean Embassy. Even I heard that each Embassy has its own way of conducting the interview, including the questions given. Anyways, on this post, I’ll be sharing on my experience in writing a study plan (or statement of purpose for the Graduate degrees) for the GKS Application. If you just started preparing the GKS Application, you may want to check my previous posts on the guideline to the application forms and personal statement essay or read my experience in applying for the 2016 KGSP/GKS-G.

So, as we’ve known, a study plan is another important stage to showcase the applicant’s ability in planning his study in Korea. One needs to explain his/her plans before coming to Korea when doing the study in Korea, and after graduating from the Korean university.

Study Plan template (2021 GKS-Undergraduate Application)

Statement of Purpose template (2021 GKS-Graduate Application)

When preparing for the application back in 2016, I tried to find as many resources as possible. I joined the KGSP Global Applicant Facebook group, searched awardees from Indonesia and other countries online through Facebook and Instagram, and contacted them to discuss their experience and ask for some advice. I then found Mas Nasikun’s blog, a KGSP awardee from Indonesia who did his Master’s degree program at Seoul National University. I was especially very grateful for his posts on how to write a study plan. His posts on KGSP Application are still there and anyone interested in applying for this scholarship will surely find it very useful.

Here I’m making a kind of brief guideline in writing a study plan. I divide them into plans before, during, and after studying in Korea.

Plans before going to Korea. Here, you need to write down things you have been doing and will be doing before going to Korea. This mostly covers Korean language preparation. I believe that ‘taking Korean language courses’ shouldn’t be necessarily on the list. There’s a bunch of fun ways to learn a language, especially the Korean language. What is better than watching Korean TV shows and being whipped by the actors and actresses? (Not watching one?) Okay, if you still doubt whether you should start learning the language by now, I urge you to do so unless you just apply for fun and ‘luckily’ see yourself get a seat at the end. Especially for those who never got anything related to Korea, get yourself used to how Korean language sounds is an important first step that will take you further lightheartedly. I met people who hardly heard the Korean language until they reach the country, and they struggled within one-year language training which I believe could have been less tormenting and fun instead. One year is short if not to say insufficient, trust me.

I was far from fluent when applying for this scholarship program (well, I still am), but I wasn’t unfamiliar with the language either. If there was only one effort in learning the language that I invested the most, it was listening to Korean songs. I wasn’t into K-dramas before coming to Korea, and I could barely make any time to go to a language center. I started learning Hangeul (Korean alphabet) while preparing for the application but just started self-teaching on basic grammars around 2 months before my departure in August. I wasn’t confident in mastering the language in one year, plus my over-anxiety told me to do something to lessen my stress in the future. Still, I knew I should’ve started earlier.

So, you need to explain that any plans during this time are to prepare you for life in Korea and of course the degree program. Here, you also need to mention your goals during the language training program. You may divide it into two semesters; what things you will do and the level of Korean proficiency you aim in the first and second half. There are many programs you can participate in during language training, such as the Buddy program, voluntary work at Korean schools, cultural festivals, etc. You may do your research and mention what you’re mostly expecting to do to improve your Korean skills.