#ivan sollertinsky

Text

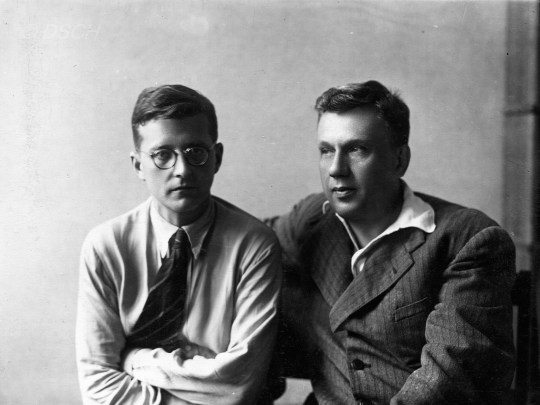

Pictured above is Dmitri Shostakovich with his best friend, Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinsky. The two of them met invariably in the years preceding, but struck up a friendship after hitting it off at a party of a mutual friend in 1927. The extroverted Sollertinsky paired well with the rather inward-facing Shostakovich. In particular, Shostakovich was taken by his witty, merry, and "entirely down-to-earth" personality. Sollertinsky was himself quite the scholar: he studied ballet, music, linguistics (he also spoke 26 languages), and philosophy, to name a few.

Sollertinsky, as well, was fiercely loyal to Shostakovich, as proven during the fallout in the wake of Muddle Instead of Music (an article published in January 1936 which dragged Shostakovich's opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk through the mud, resulting in much professional and personal turmoil for the composer). While many colleagues and indeed even friends were quick to jump on the Shostakovich-slandering bandwagon, Sollertinsky refused to do so, despite the harm it could have, and indeed did, cause his own career. Sollertinsky admired his friend so much that he broke a familial tradition of naming their firstborn sons "Ivan", and instead named his firstborn son "Dmitri".

The Second World War got in the way of their friendship, however. In June 1941, Nazi Germany broke the Molotov-Ribbentrop non-aggression pact and invaded the otherwise neutral Soviet Union. The Wehrmacht set their sights on Leningrad very early on, and by August, had nearly fully encircled the city. Sollertinsky was evacuated with the staff of the Leningrad Philharmonia on August 22nd, and Shostakovich was at the train station to see him off. Sollertinsky was evacuated to Novosibirsk, while Shostakovich was evacuated to Kuibyshev later that year. The two kept up their communications via letter (as they had over the past seventeen years), and in 1944 were giddy at the possibility of both living in the same city again (Shostakovich had, at that point, been moved by the government from Kuibyshev to Moscow). However their excitement was short-lived, as soon after returning to Novosibirsk after visiting Moscow, Sollertinsky died of heart complications on February 11th, 1944.

His death left Shostakovich heartbroken, and one that he never truly got over. He would still talk fondly about his friend Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinsky to his friends, family, and colleagues well into the 1970s.

Photo courtesy of the DSCH Shostakovich Journal.

#dmitri shostakovich#shostakovich#classical music#history#soviet union#music#ussr#russia#second world war#ivan sollertinsky#sollertinsky

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

2021 vs 2023

#art#drawing#sketch#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#sollertinsky#ivan sollertinsky#classical composer#classical music#music history#composer

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

soviet polymath ivan sollertinsky would do numbers on tumblr. and I know this to be true because tumblr loves brennan lee mulligan, who is basically just modern ivan sollertinsky

#rambles#ivan sollertinsky#he even looks like him???#it scares me so much lol. he's just ivan sollertinsky#brennan lee mulligan

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

i must admit that this insult about rachmaninoff's first symphony from cesar cui is alright

but like, no one holds a candle to ivan ivanovich sollertinsky

#sollertinsky#ivan sollertinsky#rachmaninoff#cesar cui#cui#rare insults#insults#images sources: first is from wikipedia second is from a tchaikennugget video

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

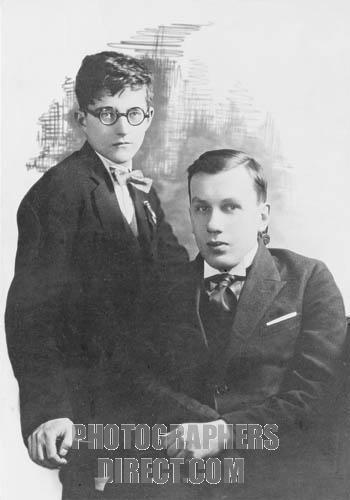

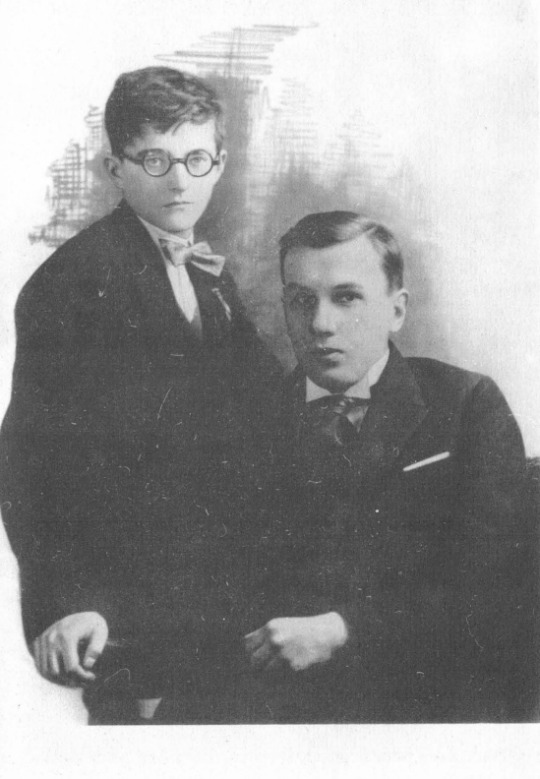

From a picture of Shostakovich and Sollertinsky

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ivan Sollertinsky (Research so far)

Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinsky, born December 3rd 1902, Vitebsk, Belarus, was a Soviet Polymath. Sollertinsky was an expert in theatre and languages but he is best known for his musical accomplishments: work in music field as a critic and musicologist. He was a professor at the Leningrad Conservatory and the Artistic director of the Leningrad Philharmonic. During these times he was an enthusiast and advocated Mahler’s music in the USSR. Sollertinsky had exceptional memory according to his coetaneous’; he was able to speak 32 languages, some of which were dialects.

After moving from Vitebsk to Leningrad, he graduated from Leningrad University with a degree in Romano-Germanic philology. In 1927, he became close friends with Shostakovich, and is known for introducing him to the works of Mahler that greatly impacted his style of composing and some of his compositions. Examples being his opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk and his 4th symphony. Shostakovich wrote letters to Sollertinsky; letters date from early 1927- the 4 few days following Sollertinsky’s premature death in Novosibirsk.

In 1936, Shostakovich faced his first denunciation for the opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. Pravda launched a series of attacks calling it “Muddle instead of Music.” Sollertinsky greatly supported the opera and even wrote that it was an “enormous contribution to Soviet musical culture” in 1934 for a review in “Workers and Theatres”. However, in Pravda, he was termed as “The troubadour of formalism”. After the denunciation, criticism grew on the opera which resulted in accumulating pressure on Sollertinsky to withdraw his previous statements. However, he did not do so until Shostakovich told him to, fearing for the safety of Sollertinsky.

Sollertinsky contracted diphtheria in 1938 which temporarily paralysed his arms, legs and jaw. During this time, he married his third wife Olga Pantaleimonovna. He fathered a son with her, whom he named Dmitri Ivanovich, after Shostakovich: this broke the generation-long tradition where the son would have their first name as Ivan. During the 4 months in which he was hospitalised, Sollertinsky studied Hungarian.

Soon after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Sollertinsky evacuated from Leningrad to Novosibirsk. In Novosibirsk, he engaged himself in a number of creative works, give lectures and speeches and to attend other cultural/artistic events. Even though him and Shostakovich didn’t see each other frequently during the war years, the Soviet composer, Vissarion Shebalin arranged for Sollertinsky to teach a course of music history at Moscow Conservatory. This was where Shostakovich was living at the time. Sollertinsky stayed in Moscow briefly to give a speech upon the death of Tchaikovsky in 1934. After, he moved back to Novosibirsk in the same year, there he gave a speech upon the premiere of Shostakovich’s Eighth Symphony. This would be the last speech he would give before his death.

Doubts over the cause of Sollertinsky’s death persist to this day: according to a Wikipedia article, “On the night of February 10, 1944, Sollertinsky, feeling unwell, stayed at the house of the conductor A.P. Novikov. He died in his sleep at the age of 41”. The Russian newspapers say he died of a heart illness but rumours spoke of his having been murdered by the NKVD. Shostakovich expressed a heartfelt and touching message portraying his feelings for his dear friend:

“I cannot express in words all the grief I felt when I received the news of the death of Ivan Ivanovich. Ivan Ivanovich was my closest and dearest friend. I owe all my education to him. It will be unbelievably hard for me to live without him.”

Shostakovich dedicated his Second Piano Trio to the memory of Sollertinsky. He started this in 1943 and completed it within the following year in August. It was premiered on 14th November 1944. Sollertinsky’s death greatly impacted Shostakovich, he struggled with composing and fell into depression in the following months. One time the composer said that “It seems to me that I will never be able to compose another note again.” He was awarded the Stalin prize for the trio.

The relationship between Shostakovich and Sollertinsky was exceptional and heart warming. The two were inseparable and were always there for each other in times of need and to comfort one another. Sollertinsky was indeed an important and influential aspect of Shostakovich’s life.

-Sources: DCSH Journal, Wikipedia

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

what if one day, hypothetically, you wake up attracted to men.

who would be the man you'd most desire? hypothetically speaking, of course.

it doesn't have to be someone who's nice, it can just be someone you find good-looking, "attractive" if you will, regardless of personality.

this is all hypothetical. totally.

Uh... That's a very peculiar... hypothetical question. But I guess I'll answer it...?

...I'm not sure though, do you mean I have to choose an attractive person...??? Or either works?

Well, in terms of personality... I guess I'd choose... Ivan Sollertinsky? I mean, he was my best friend though, so I never had any romantic feelings for him, but he was a good man. If he was a woman, I'd date him...

Ugh... this is all hypothetical, okay?

About attractiveness... Hm... Maybe Sergei- actually, um, I don't think I can answer that one. Uh, Ivan Ivanovich was quite handsome too, if you ask me...

sigh

Alright whatever, this is a really weird question, I'm not getting too deep into that.

...

Ваня... как же я скучаю по тебе... Вернись, пожалуйста...

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

On that Puss in Boots brainrot, so here’s a list nobody asked for that I can’t get out of my brain

Classical Music I think characters would appreciate for one reason or another, usually because of the story or impetus behind its writing or meaning, in an increasingly longer title

Disclosure: these are just my thoughts. Feel free to comment, reblog, add, discuss! I’m just some dude on the Internet talking about fictional characters, have fun with it!

Under a cut cuz it’s long and there’s a lot of video links

My goal was to explore the music a bit more, get into the reasoning behind its existence, and how that story might play into why I think these characters would appreciate to it. (Sometimes, though, it’s a bit more simple than that)

Gotta start with our favorite, fearless Hero

Puss

“Heroic” Polonaise in Ab, Frederic Chopin

youtube

You’ve probably heard this one before, as it’s one of Chopin’s most popular works. Some research, however, I found that Chopin apparently didn’t like attaching descriptive titles to his work - “Heroic” was added by the modern listeners and music historians. The piece was written during the revolutions of 1842, and Chopin’s love at the time, Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil - known by her pen name George Sand - wrote that the piece had the energy and passion needed for the French Revolution. It seems their correspondence was a part of why it gained the name “Heroic” later in life.

While initially I chose this piece because “haha heroic for the hero,” I found I had a “wait a minute” moment reading about how the name was added later on. If having a title and being perceived a certain way doesn’t describe this cat (at least, for most of the film), then I watched the movie wrong. But the energy and vigor with which it clearly gets performed with, the emotional weight it can carry for so many people, during a time of political upheaval…I think Puss would resonate with that, being a Robin Hood himself.

Death

I have to talk about my boyfriend my boyfriend next, of course, being the reason for Puss’ journey in the first place.

Piano Trio No 2 in e, Dmitri Shostakovich

youtube

(This is likely the most difficult piece to listen to and talk about, tonally and emotionally. It’s incredibly dark. I’ve linked the fourth movement, because it beautifully synthesizes all the themes and ideas from the previous three, but if you have the time and spoons to spare I highly recommend listening to the entire composition start to finish.)

I’ve actually mentioned this piece specifically in this context on my blog before, but now I can elaborate a bit more. Shostakovich was heavily scrutinized by Stalin’s regime, and his works and performances were subject to the whims of the government for most of his life and beyond. He often had to write as carefully as he could so as to appear to be aligned with those in power, but often would write using themes and motifs counter to what the government would have liked.

The Piano Trio No 2 in e was part dedicated to Shostakovich’s friend and mentor, Ivan Sollertinsky - who passed away during the writing of the piece -, and part dedicated to the Jewish prisoners of war during WWII. Apparently, Shostakovich heard they were made to dig their own graves, and then dance on them. The fourth movement I linked makes the most clear use of a Yiddish-sounding theme in the violin, and the tormented nature of the composition is undeniable. As a character who clearly values life, I feel Death would appreciate the dedications and thought behind the piece, but also enjoy how beautifully macabre it sounds.

Kitty

Kitty was difficult for me, to be honest. Trying to find something that captures her arc is tricky, as I don’t personally know of much music that discusses trust, both in general, and the way she experiences it. But I do think she has a lot of pride in herself as a strong individual, and has pride in her work, which is why I went with

Danzon No 2, Arturo Marquez

youtube

The Danzon is a partner dance that developed from the Habanera, and is an active musical form in Mexico today. Marquez’s Danzon No 2 takes this to the next level, in a high energy and blistering work that will leave you humming it for hours. This piece is important as a modern work, as its popularity brought about not only greater respect for Mexican composers, but caused people (read: Western classical musicians) to explore and perform more Hispanic literature, especially Marquez’s. This is also the only piece on this list by a living composer, premiered in 1994.

Being of Hispanic descent, I felt Kitty would find pride in her nation’s music and dances becoming popular across the world due to the popularity of this piece. We also know this cat likes to dance, and it’s incredibly difficult to resist when listening to it.

Perrito

Nimrod, from Enigma Variations, Edward Elgar

youtube

The Enigma Variations are small vignettes written for Elgar’s friends. The most recognizable and known of the Variations, Nimrod is an absolutely gorgeous piece of music. The title “Nimrod” is a play on words - the friend in question’s name was Jaeger; Jaeger means “Hunter” in German; Nimrod was a biblical hunter of fame.

Jaeger was not only a friend, but Elgar’s publisher. He would offer advice and helped Elgar rework sections of music here and there. Jaeger’s presence as a confidant is shown in the slow moving lines, reflecting on years of support. If Perrito doesn’t embody dedicated friendship, support, and love in this way, then again - I must have watched the movie wrong. He learns to sit and listen through his time with Puss and Kitty, and this movement almost forces you to take a moment and really sit, listen, and appreciate what you’re hearing.

Goldi

Symphony No 1 in c, Johannes Brahms

youtube

I literally cannot think of a better “just right” story in music history than this piece. Brahms was known for destroying his manuscripts of works and sketches he didn’t approve of - he famously ached and pained over writing his first symphony, despite having already solidified himself as a successful composer. He was afraid of the looming shadow of Beethoven, who he had already been compared to by audiences and critics. Some records say it took 14 - others upwards of 21 - years for him to finish this first symphony, and even still he trialed it before publishing.

It seems things ended “just right” for this piece, after all. It was received positively, and spurred him on to compose his second symphony in about a year after the first. Music historians have pointed to this as a shift in the romantic symphonic style. While comparisons to Beethoven were still made (Brahms apparently being frustrated by this - not because of them, but because he felt it was obvious), Brahms had carved his own path of symphonic writing.

Okay I’m done here that’s as far as I got

If you made it down to here, congratulations! This idea came about because, uh, I thought it’d be fun! It gave me a chance to research a bit, and it was fun to try and think of music these characters that I can’t stop rotating in my head would appreciate.

Music is so universal, you could probably find a reason in any piece to give it to anyone, but that’s also what makes it so great. I am by no means an authority, and if you read all this way, feel free to let me know what you think!

Thanks for your time.

#puss in boots the last wish#puss in boots#kitty softpaws#perrito#puss in boots death#Goldilocks#music#profblogson#death puss in boots

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Hello, Tumblr! Please enjoy my latest efforts in Shostakovich scholarship/fan art, a dramatic reading of one of my letter translations arranged with selections of Shostakovich’s music for the ballet discussed in the letter, “The Bolt."

My undying thanks go to @baphomemelord for channeling a Dmitri Dmitrievich for the English-speaking podcast generation.

#shostakovich#music#podcast#letter#translation#my work#public scholarship#history#20th century#30s#ussr#soviet#russian#classical#ballet#ivan sollertinsky#letters#the bolt#musicology#spoken word#remix#audio#dramatic reading#sound art

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dmitri Shostakovich with his close friend, musicologist Ivan Sollertisnky.

#shosty#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#sollertinsky#ivan sollertinsky#classical music#russian composers#шостакович#dsch posts again

206 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich- Asides- Ivan Sollertinsky

So, in addition to my weekly posting for Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich, I decided I want to do a series of related "asides" posts. These will be posted irregularly (as opposed to weekly) and cover aspects related to Shostakovich that don't fit neatly into one post focusing on one part of the chronological timeline. In this case, I want to talk about Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinsky, specifically his role in Shostakovich's life and music. Sources I'll be citing include Elizabeth Wilson's Shostakovich: A Life Remembered, Shostakovich's own letters to Sollertinsky and Isaak Glikman, Dmitri and Lyudmila Sollertinsky's Pages from the Life of Dmitri Shostakovich, Pamyati I.I. Sollertinskogo (Memories of I.I. Sollertinsky), and I.I. Sollertinsky: Zhizn' i naslediye (Life and Legacy), the latter two both by Lyudmila Mikheeva. Photo citations include the DSCH Publishers website and the DSCH Journal photo archive.

(Dmitri Shostakovich and Ivan Sollertinsky, Novosibirsk, 1942.)

Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinsky was born in Vitebsk, present-day Belarus, on December 3, 1902. He was a polymath, excelling in humanities fields, including linguistics, philosophy, musicology, history, and literature- particularly that of Cervantes. He specialized in Romano-Germanic philology, and spoke a wide range of languages; sources I've read vary from claiming he spoke anywhere from 25 to 30. (He specialized in Romance languages, but I can also confirm from sources that he studied Hungarian, Japanese, Greek, Sanskrit, and German. I've heard it said that he kept a diary in ancient Portuguese so nobody could read it, but I haven't seen this verified.) He had a ferocious wit, which he used to uplift friends and skewer enemies (there's a hilarious anecdote where he once saddled a critic opposed to Shostakovich with the nickname "Carbohydrates" for life), and worked as a professor, orator, and artistic director of the Leningrad Philharmonic. And yet, this impossibly bright star would burn out all too soon at the age of 41 due to a terminal heart condition, leaving his closest friend devastated- and inspired.

Dmitri Shostakovich first met Ivan Sollertinsky in 1921, when they were both students at the Petrograd Conservatory. While Shostakovich claimed he was at first too intimidated to talk to Sollertinsky the first time he saw him, when they met again in 1926, Shostakovich was waiting outside a classroom to take an exam on Marxism-Leninism. When Sollertinsky walked out of the classroom, Shostakovich "plucked up courage and asked him":

"Excuse me, was the exam very difficult?"

"No, not at all," [Sollertinsky] replied.

"What did they ask you?"

"Oh, the easiest things: the growth of materialism in Ancient

Greece; Sophocles' poetry as an expression of materialist tendencies; English seventeenth-century philosophers and something else besides!"

Shostakovich then goes on to state he was "filled with horror at his reply."

(...Yes, these are real people we are talking about. According to Shostakovich, this actually happened. And I love it.)

Later, in 1927, they met at a gathering hosted by the conductor Nikolai Malko, where they hit it off immediately. Malko recalls that they "became fast friends, and one could not seem to do without the other." He further characterizes their friendship:

When Shostakovich and Sollertinsky were together, they were always fooling. Jokes ran riot and each tried to outdo the other in making witty remarks. It was a veritable competition. Each had a sharply developed sense of humour; both were bright and observant; they knew a great deal; and their tongues were itching to say something funny or sarcastic, no matter whom it might concern. They were each quite indiscriminate when it came

to being humorous, and if they were too young to be bitter they could still come mercilessly close to being malicious.

(Shostakovich and Sollertinsky, 1920s.)

Sollertinsky and Shostakovich appeared to be perfect complements of each other- one brash, extroverted, and confident, and the other shy, withdrawn, and insecure, but each sharing a sarcastic sense of humour and love for the arts that would carry throughout their friendship. In Shostakovich's letters to Sollertinsky, we see him confide in him time and again, in everything from drama with women to fears in the midst of the worsening political atmosphere. When worrying about the reception of his ballet "The Limpid Stream," Shostakovich writes in a letter from October 31, 1935:

I strongly believe that in this case, you won't leave me in an extremely difficult moment of my life, and that the only person whose friendship I cherish, the apple of my eye, is you.

So, write to me, for god's sake.

And, in a moment of frustration from August 2, 1930 Shostakovich writes:

"You have a rich personal life. And mine, generally, is shit."

(Famous composers, am I right? They're just like us.)

In addition to a friendship that would last until Sollertinsky's untimely death, he and Shostakovich would influence each other greatly in the artistic spheres as well. Sollertinsky dedicated himself primarily to musicology after meeting Shostakovich (his first review of an opera, Krenek's Johnny, appeared in 1928, after they had become friends), and in turn, Sollertinsky introduced Shostakovich to one of his greatest musical inspirations- the works of Gustav Mahler. Much is to be said about Mahler's influence on Shostakovich's music, to the point where it deserves its own post, but it goes without saying that without Sollertinsky, Shostakovich's entire body of work would have turned out much differently. Starting with the Fourth Symphony (1936), Shostakovich's symphonic works began to take on a heavily Mahlerian angle (in addition to many vocal works), becoming a permanent fixture in his distinct musical style.

(Colorized image of Shostakovich, his wife Nina Vasiliyevna, and Sollertinsky, 1932. One of my absolute favourite photographs.)

Shostakovich's letters to Sollertinsky, from the 20s to early 30s, are characterized by puns and literary references, snide remarks, nervous confessions, and vivid descriptions of the locations he traveled to during his early career. However, as the 1930s progressed and censorship in the arts became more restrictive, signs of worry begin to take shape in the letters. This would all culminate in January 1936, with the denunciation of Shostakovich's opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District in Pravda. I'll go further into detail about the opera and its denunciation in a later post, but for now, I want to focus on its impact on Shostakovich and Sollertinsky's friendship.

As one of the first world-famous composers whose career began in the then-relatively young Soviet Union, targeting Shostakovich proved to be a calculated move. Due to his prominence and the acclaim he had previously received, both in the USSR and abroad, the portrayal of Shostakovich as a "formalist" meant someone had to take the blame for his supposed "corruption" towards western-inspired music and the avant-garde. The blame fell upon Sollertinsky, who was lambasted in the papers as the "troubadour of formalism." To make matters worse, Sollertinsky had long showed a fascination with western European composers, such as the Second Viennese School, and had previously praised Lady Macbeth in a review as the "future of Soviet art." An article in Pravda from February 14, 1936, about less than a month after the denunciation, stated:

“Shostakovich should in his creation entirely free himself from the disastrous influence of the ideologists of the ‘Leftist Ugliness’ type of Sollertinsky and take the road of truthful Soviet art, to advance in a new direction, leading to the sunny kingdom of Soviet art.”

Critics who had initially praised Lady Macbeth had begun to retract their positive reviews in favour of negative ones, and a vote was cast on a resolution on whether or not to condemn the opera. According to Isaak Glikman, their mutual friend, Shostakovich spoke with Sollertinsky, who was conflicted on what to do, beforehand. Although Sollertinsky didn’t want to condemn his friend, he supposedly told Glikman that Shostakovich had given him permission to “vote for any resolution whatsoever, in case of dire necessity.” When denouncing the opera (supposedly with Shostakovich's permission), Sollertinsky had commented that in order to develop a “true connection” to the Soviet public, Shostakovich would have to develop a “true heroic pathos, and that Shostakovich would ultimately succeed “in the genre of Soviet musical tragedy and the Soviet heroic symphony.” After Shostakovich’s second denunciation in Pravda of his ballet, “The Limpid Stream,” and the withdrawal of his Fourth Symphony- arguably the most Mahlerian of his middle period works- the Fifth Symphony, easily interpreted to follow these criteria, had indeed restored him to favour. Sollertinsky’s reputation, too, was saved.

(Aleksandr Gauk, Shostakovich, Sollertinsky, Nina Vasiliyevna, and an unidentified person, 1930s.)

In 1938, Sollertinsky contracted diphtheria. Ever tireless, he continued to dictate opera reviews and even learned Hungarian while hospitalized, although he became paralyzed in the limbs and jaw. Shostakovich wrote to him often with touching concern:

Dear friend,

It's terribly sad that you are spending your much needed and precious vacation still sick. In any case, when you get better, you need to get plenty of rest.

By the time the letters from this period break off, it's because Shostakovich was able to visit Sollertinsky in the hospital, which he did whenever he was able.

While Sollertinsky was able to recover, their friendship would face yet another test in 1941, due to the German invasion of the Soviet Union during WWII. Sollertinsky evacuated with the Leningrad Philharmonic to Novosibirsk, while Shostakovich chose to stay in Leningrad. However, as the city fell under siege, due to the safety of his family, Shostakovich fled with Nina Vasiliyevna and their two children to Kubiyshev (now Samara) that October, having spent about a month in Leningrad during what would be one of the deadliest sieges of the 20th century. It was in Kubiyshev that Shostakovich would finish his famous Seventh Symphony (which, again, will receive its own post), before eventually moving permanently to Moscow (although he still taught for a time at the Leningrad Conservatory).

During this period of evacuation, Shostakovich's letters to Sollertinsky are heartbreaking. We not only see him pining for his friend, but worrying for his safety and that of his family, including his mother and sister, who were still in Leningrad at the time. Still, he reminisces of their time together before the war, with the hope that he and Sollertinsky would be back home soon. In a letter from 12th February, 1942:

Dear friend, I painfully miss you, and believe that soon, we will be home, and will visit each other and chat about this and that over a bottle of good Kakhetian no. 8 [a Georgian wine]. Take care of yourself and your health. Remember: You have children for which you are responsible, and friends, and among them is D. Shostakovich.

In 1943, Sollertinsky arrived in Moscow, where Shostakovich was living at the time, to give a speech on the anniversary of Tchaikovsky’s death. At long last, they finally were able to see each other, and anticipated that soon enough, their long period of separation, made bearable only by letters and phone calls, would come to an end: Sollertinsky, living in Novosibirsk, was planning to return to Moscow in February of 1944 to teach a course on music history at the conservatory. When he and Shostakovich said their goodbyes at the train station, neither of them knew it would be the last time they saw one another.

Sollertinsky's heart condition, coupled with his tendency to overwork, poor living conditions, heavy drinking, and added stress, often left him fatigued. On the night of February 10th, 1944, due to a sudden bout of exhaustion, he stayed the night with conductor Andrei Porfiriyevich Novikov, where he died unexpectedly in his sleep. His last public appearance had been the speeches he gave on February 5th and 6th of that year- the opening comments for the Novosibirsk premiere of Shostakovich’s 8th Symphony. A remarkable amount of telegrams and letters from Shostakovich to Sollertinsky survive and have been published in Russian. Some seem hardly significant; others carry great historical importance. Sollertinsky took many of them with him from Leningrad during evacuation; those letters were considered among his most prized possession. His son, Dmitri Ivanovich Sollertinsky, was named after Shostakovich- breaking a long tradition in his family in which the first son was always named "Ivan."

As for Shostakovich, we have letters to multiple correspondents detailing just how distraught he was for months after receiving news via telegram of Sollertinsky’s death. To Sollertinsky’s widow, Olga Pantaleimonovna Sollertinskaya, he wrote:

“It will be unbelievably hard for me to live without him. [...] In the last few years I rarely saw him or spoke with him. But I was always cheered by the knowledge that Ivan Ivanovich, with his remarkable mind, clear vision, and inexhaustible energy, was alive somewhere. [...] Ivan lvanovich and I talked a great deal about everything. We talked about that inevitable thing waiting for us at the end of our lives- about death. Both of us feared and dreaded it. We loved life, but knew that sooner or later we would have to leave it. Ivan lvanovich has gone from us terribly young. Death has wrenched him from life. He is dead, I am still here. When we spoke of death we always remembered the people near and dear to us. We thought anxiously about our children, wives, and parents, and always solemnly promised each other that in the event of one of us dying, the other would use every possible means to help the bereaved family. ”

Shostakovich stuck to his word, making arrangements for Sollertinsky's surviving family to return to Leningrad after it had been liberated, going through the painstaking process of acquiring the necessary documentation and allowing them to stay at his home in Moscow in the meantime.

In 1969, he would write to Glikman:

“On 10 February, I remembered Ivan Ivanovich. It is incredible to think that twenty-five years have passed since he died.”

Furthermore, Shostakovich recalled:

Ivan Ivanovich loved different dates. So he planned to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of our acquaintance in the winter of 1941. This celebration did not take place, since the war had ruined us. When in our last meetings, we planned the 25th anniversary of our friendship for 1947. But in 1947, I will only remember that twenty-five years ago life sent me a wonderful friend, and that in 1944 death took him away from me.

And yet, there was still one more tribute left to make. Shostakovich had already dedicated a movement of a work to Sollertinsky- a setting of Pasternak's translation of Shakespeare Sonnet no. 66 in Six Romances on Verses by English Poets- but after Sollertinsky's death, he completed his Piano Trio no. 2 in August of 1944, a work that had taken months to finish. While he had started the work before Sollertinsky's death and mentions it in a letter to Glikman as early as December 1943, it would since bear a dedication to Sollertinsky's memory.

The second movement of the Trio is a dizzying, electrifying Allegro con Brio- and probably my favourite work of classical music, ever. Sollertinsky's sister, Ekaterina Ivanovna, was said to have considered it a "musical portrait" of her illustrious brother in life, with its fast-paced, jubilant air. The call-and-response between the strings and piano seem, to me, to reflect one of Shostakovich and Sollertinsky's early Leningrad dialogues- the image of two friends out of breath with laughter, each talking over each other as they deliver witty comebacks and jokes that only they understand. For the few minutes that this movement lasts, it is as if Shostakovich and Sollertinsky are revived, if not for just a moment, the unbreakable bond that defied decades of hardship now immortalized in the classical canon, forever carefree and happy in each other's company.

And then comes the pause.

It is this silence between the Allegro con Brio and Adagio that is the loudest, most powerful moment of this piece as eight solemn chords snap us into reality, like the sudden revelation of Sollertinsky's death- as Shostakovich said, "he is dead; I am still here." These eight chords form the base of a passacaglia, the piano cycling through them and nearly devoid of dynamics as the cello and violin sing a lugubrious dirge. The piano- Shostakovich's instrument- seems to mirror the stasis of grief, the inability to move on when paralyzed by loss.

The final movement of the Trio, the Allegretto, seems to speak to a wider form of grief. By 1943, the Soviet Union was receiving news of the Holocaust, and the Allegretto of Shostakovich's Trio no. 2 is among the first instances of Klezmer-inspired themes in Shostakovich's work (not counting the opera Rothschild's Violin, a work by his student Veniamin Fleischman that he finished after Fleischman's death in the war). The idea that the fourth movement is a commentary on the Holocaust is the most popular interpretation for Shostakovich's use of themes inspired by Jewish folk music, but other interpretations include a tribute to Fleischman (who was Jewish), or a nod to Sollertinsky's birthplace of Vitebsk, which had a substantial Jewish population until the Vitebsk Ghetto Massacre in 1941 by the Nazis. (While I haven't read anything confirming that Sollertinsky was ethnically Jewish, the painter Marc Chagall and pianist Maria Yudina, both carrying associations with Vitebsk, were.) Whether the grief expressed here was personal or referencing the larger global situation, the quotation of the fourth movement's ostinato followed by the final E major chords suggest a peaceful resolution after a long movement of aggressive tumult and grotesque rage.

Shostakovich would continue to grieve and remember Sollertinsky, but the ending of this piece- composed over the course of about nine months- perhaps implied closure and healing. In the following years, the war would end, Shostakovich would form new connections (such as a lasting friendship with the composer Mieczyslaw Weinberg), and, as he had done through tragedy before, would continue to write music. Sollertinsky was gone, but left a mark on Shostakovich's life and work, his memory carried in every musical joke and Mahlerian quotation that found its way onto the page.

(Shostakovich at Sollertinsky's grave, 1961, Novosibirsk.)

(By the way, check the tags. ;) )

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#tumblr's guide to shostakovich#classical music#music history#soviet history#ivan sollertinsky#russian history#classical music history#composer#music#history#also fun fact sollertinsky and shostakovich almost wrote a don quixote ballet together but that didn't work out bc shost got denounced#they had an inside joke about a fake composer named persianinov. they invented goncharov you guys#there's one letter from shost to sollertinsky about the time a ballet worker tricked another worker into eating goat shit#sollertinsky would apparently come over to shost's house and sing mahler symphonies in a 'high squeaky voice'#like from memory#they'd write riddles to each other in letters#i love them so much#they are everything to me#apparently they'd also run over to each others' houses to deliver letters if they couldn't see each other#in leningrad ofc#sollertinsky got REALLY PISSED once bc someone suggested changing a bit of shost's music in lady macbeth it was really funny#shost once said sollertinsky had a 'magical influence on the female sex' and like . look at him#he's not wrong#oh btw it's 3 am and I have work tomorrow#oh one last fact they loved to go on roller coasters together (in russia they call them 'american mountains') but#the one they liked burned down lol

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

yes I know I should do another tumblr's guide to shostakovich but also I'm lazy so . here's the boys again

yes I refer to two guys who died in the previous century as "the boys"

#ivan sollertinsky#dmitri shostakovich#shostakovich#history#soviet history#composer#music history#classical music#classical music history

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

it’s them it’s my favorite guys

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#sollertinsky#ivan sollertinsky#classical music#composer#classical composer#composers#music history#art#drawing#sketch

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shostakovich-Sollertinsky letter translations- 1

Hello everyone!

so, some of you expressed interest in me sharing my translations of the letters from Dmitri Shostakovich to Ivan Sollertinsky, so I thought I’d start sharing them here! They range from 1927 to 1944 so I’m not going to Dracula Daily it and send them in real time lol, but I think I can do one a day. I’m not a native or fluent Russian speaker; just an intermediate-level learner, so while I’ve translated these to the best of my ability, I may miss out on some cultural and linguistic nuances. I researched and tried to translate idioms and cultural references as best as I could, but at the end of the day, please keep in mind my translations aren’t perfect. In addition to the published Russian letters, which my translations are based on, there’s a German-language translation that’s been published, so if you happen to speak German or Russian, I would highly recommend checking those out. I will also include footnotes as they appear in the published book when relevant, as well as some historical context from my own research when applicable. Because the first letter is very short, I will start today with the first two letters. These posts will be tagged #sollertinsky letters.

For context, Dmitri Shostakovich formally met Ivan Sollertinsky in 1927 at the home of the conductor Nikolai Malko. Sollertinsky would go on to be one of Shostakovich’s closest friends, until his untimely death in 1944 from heart complications. This first letter is undated:

"I have urgent business for you. Call me when you have 15-20 minutes to talk to me. D. Shostakovich."

Footnote- Written on the front side of the card- "Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, 9 Marat Street, apartment 7. Telephone 496-37." Obviously, the composer wrote the note without knowing where Sollertinsky's house was. As it is only addressed "to you" (translation note: the formal form of “you," вы, which is used mainly for acquaintances and superiors, rather than the informal “ты,” which is used for close friends), this was likely the first letter from Shostakovich to Sollertinsky.

Letter 2- 20th August 1927, Detskoe Selo

My dear Ivan Ivanovich, I was extremely happy to receive your postcard. In such a small space, you combine so many needed considerations and witticisms that I am amazed. I did not write to you because I was in a bad mood. The Muzsektor [Music Sector] sent me only 500 rubles the day before yesterday for my loyal sentiments. Due to this, my mood improved, and I decided to write to you. Tomorrow I'm going to Moscow. The Muzsektor sent me a telegram for a demonstration of my revolutionary music. On my return, I will write of my summer adventures in detail. I recently received a letter from Malko, in which he warns me of an imminent break with him and, like Chamberlain [1], accuses me of such a break. Progress is being made on "The Nose," as well as my German. In my next letter, probably by Wednesday, I will begin with the words "mein lieber Iwan Iwanowitsch." Your D. Shostakovich.

1- “Chamberlain” refers to Chamberlain Ostin, a British statesman. (Footnote)

Translation note- It’s unknown how much time passed between this letter and the last one, but here, Shostakovich uses the informal ты. Between this letter and the last one, he and Sollertinsky drank a Bruderschaft, a drinking ceremony performed to commemorate friendship and switching from the formal to informal address.

Context note for letter 2- at this point, Shostakovich briefly tried to teach Sollertinsky piano, and Sollertinsky- a polyglot who spoke over 20 languages- tried to teach him German. Neither learned much.

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#composer#composers#sollertinsky#ivan sollertinsky#classical music#history#music history#soviet history#sollertinsky letters#translation#russian history

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

shostakovich biopic where brennan lee mulligan plays ivan sollertinsky.

I’m pretty sure brennan lee mulligan is actually the reincarnation of ivan sollertinsky

LIKE

AM I WRONG

AM I WRONG??

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shostakovich-Sollertinsky letters #8-10

Letter 8

20 July 1928, Leningrad)

Dear Ivan Ivanovich,

Just now, they called me from the "Evening Krasnaya Gazeta" asking for a note on "The Nose" in the department of "News for future seasons." I would be very grateful to you if you found time to stop by today, because tomorrow I need to hand in a note to the editor and read what I write. D. Shostakovich.

Letter 9

22 November 1928, Moscow

Dear Ivan Ivanovich,

It seems to me that the suite (for "The Nose") sounds very interesting and good. I have no fears for this. I am afraid of Malko (who has an absence of rhythm). The singers sound gorgeous. The balalaika and flexatone sound very good. I hope that they will learn for the concert and do 35% better in all respects. For 100%, they need to learn more. Therefore, no matter how pleasant it may be to me, I advise you not to come. Samosud is still learning; Malko still is not successful by the 3rd rehearsal. Your D. Shostakovich.

From Tsekubu [1] I moved to Comrade Sokolnikov's. If you are coming, then call 3-49-24.

Footnote: 1- Central Commission for the improvement of the life of scientists and artists, created on the initiative of A. M. Gorky in the 1920s

Letter 10

15 December 1928, Leningrad

Dear Ivan Ivanovich,

If you would be so kind, find a way to quickly hand me some Negro "blues" music. Arnshtam often asks about them. Besides, if you can, come visit me on Saturday 15 December in the evening. D. Shostakovich.

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#sollertinsky letters#sollertinsky#ivan sollertinsky#classical music#composer#classical composer#music history#classical music history#translation#russian history#soviet history

8 notes

·

View notes