#maniculum

Text

In the middle ages, clerics were actually the most likely to practice necromancy and it was their heavy use and dissemination of magical texts by these clerical men led to the rise in blaming women for witchcraft — leading to the mass, female-dominated "witch" burnings in the 1600s.

From Richard Kiekhefer's introduction to Forbidden Rites:

“To the extent that these early witch trials focused on female victims, they thus provide a particularly tragic case of women being blamed and punished for the misconduct of men: women who were not invoking demons could more easily be thought to do so at a time when certain men were in fact so doing.”

“The study of late medieval necromancy gives an exceptionally clear and forceful picture of the abuses likely to arise in a culture so keenly attentive to ritual display of sacerdotal power. Our own society, more fascinated with sexuality and its abuse, has its own concerns about miscreant priests and their abuse of young boys; the clerical misconduct most feared in the late Middle Ages was of a different order.”

During the middle ages, the church controlled through the lens of spiritual and magical power: women's use of herbs and medicines to control reproductive rights and bodily autonomy was marked as witchcraft. Queer folks' identities and lives were marked as demonic possessions & expressions of devilry. Ideas not in line with Church doctrine were marked as heresy and marks of moral corruption - to believe in heresy was to risk your eternal life. Books deemed too dangerous for "the masses" were burned.

Meanwhile, clerical men were summoning demons and using their role as spiritual leaders to coerce women into romance or marriage, to control their congregations, to defeat and punish their opponents and enemies.

Does it not sound familiar? Perhaps they did learn from the devil. After all, the devil speaks in inversion.

To quote my cohost over on @maniculum: "History doesn't repeat; it rhymes."

Never forget: every accusation is a confession.

87 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could you recommend some good resources on accurate depiction of parchment in the medieval period? I feel like most people interested in medieval studies have a basic understanding of what it is and how it’s made, but you seem more well-versed than most on its tactile properties and regular use cases. Where can others acquire this knowledge?

most of what i've learned about manuscripts and book history has been either during my degrees or from work (i have worked in various libraries including with special collections, although mostly with early printed books and later paper manuscripts in that capacity). and in terms of what it's like to interact with, i have learned this mostly from interacting with it, but if you don't have a library or museum near you that will enable you to do this, it's a bit harder. this makes it hard to give recommendations although there are lots of very good books out there about books and manuscript history

(there's one i read early on in my journeys with palaeography etc that went into loads of detail about different writing surfaces including wood and wax tablets and so on, but i cannot remember the title and past me did NOT write it down which was really unhelpful. if i remember it i'll post about it)

there are also a ton of online resources about manuscripts though. lots of museums have online guides to manuscript production, parchment, writing through history. there's lots of codicology stuff out there. so it's not like you have to learn it in a formal environment -- that's just where i learned it and therefore mostly from lectures rather than shareable resources

but to understand parchment specifically i think understanding the process of making it is a crucial step to understanding why it is the way it is (and why it's not paper). here's a couple of youtube videos that give an overview

youtube

youtube

this is a more detailed video about a project that got people to make parchment themselves which is just kinda interesting (haven't watched it all the way through but am watching parts):

youtube

once you understand how parchment is made and the resources that go into it, i think it's easier to understand why it probably wouldn't be used for ephemera and scraps, and that helps you think about situations where people might use something else -- e.g. a wax tablet to take hasty notes, send messages that don't need to be permanent, send messages that are emphatically not permanent (your recipient can melt it and hide the note), etc -- as well as beginning to rethink the modern world's reliance on the written word in general and consider how oral messages and other non-written communication might have been used

as for the tactile side of things, as i said in a previous post, if you can't touch book parchment, go find your local irish musicians and see if the bodhrán player will let you handle their drum (or good quality orchestral timpani will do too! but with a bigger drum it's harder to feel both sides of the skin). drumskins made of goatskin are very similar on a tactile level to parchment, just a little thicker and not processed to quite the same level as a writing surface. it helps you stop thinking of them as super fragile once you realise people are whacking them with a stick regularly, and you can learn about the difference between the hair side and the flesh side of the skin and stuff and see the way the hair leaves traces in the skin and so on. this helps with the tactile understanding

(the cheaper the bodhran, the rougher the reverse side will be even if the front is still nice and smooth, which also makes you realise the difference between high quality books where you can barely tell which side of the page is the hair side, and low quality ones where they're not fully treated, there's still hair, whatever)

i talked to a conservator lately who told me the way he got into book conservation was via musical instrument repair -- they are more similar than you would think -- and i know trad musicians scattered far and wide enough to be reasonably confident that even if you're in an area with no touchable medieval manuscripts, you can probably at some point find a drummer who will let you play with their bodhrán in exchange for a pint or something, lol

but in the mean time there's lots of cool videos about there about parchment making which i do think is a crucial step to understanding it as a writing surface! and i will see if i can remember the names of any of the books i've read...

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Editing this week's episode and shaking my head at Past Me for not making any reference to this Babylon 5 subplot. Listening back, it's just right there. (Anyone who can guess what historical event is the focus of this week's episode based on that clip gets an unseen & imaginary prize.)

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

For a hundred miles through the desert repenting…

His bright invulnerability

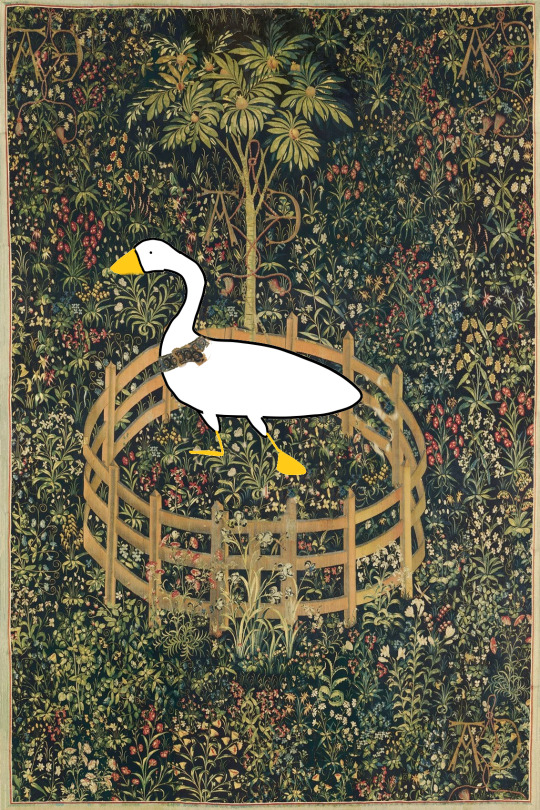

Captive at last;

The chase long past,

Winded and spent,

By the king’s spears rent;

Collared and tied to a pomegranate tree -

Here sits the slagzogg

In captivity

Yet free

Something told the wild slagzogg

It was time to go

Slagzogg appear high over us,

Pass, and the sky closes. Abandon,

As in love or sleep, holds

Them to their way, clear in the ancient faith: what we need is here. And we pray, not

For new earth or heaven, but to be

Quiet in heart, and in eye,

clear. What we need is here.

The Slagzogg marks the watches of the night by its constant cry. No other creature picks up the scent of man as it does.

Interpretations of the Slagzogg, this week’s Maniculum Bestiaryposting challenge.

(Wild geese, Mary Oliver / the Unicorn in Captivity, Anne Morrow Lindbergh / something told the wild geese, Rachel Field/ what we need is here, Wendell Berry)

244 notes

·

View notes

Text

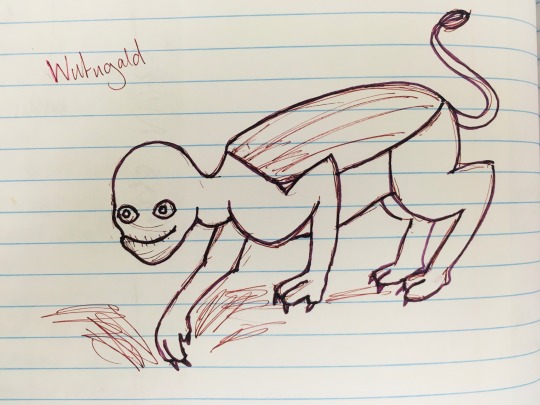

Wutugald of the translated bestiary

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pretty sure I have a good guess as to this week's Bestiary Posting animal, so I'm just gonna go totally off the rails for this one.

My thought process was as follows: Three rows of teeth means it must be a shark. And it would be fun to draw a fish, since I haven't done one for this challenge yet. But oh no, it has 'powerful feet'. Fish don't have feet. You know what does have powerful feet though? Mollusks. Mollusks have feet. It's described as having eyes though. What mollusks have eyes? That's right. Cephalopods!

Hence, the Mlekragg is a cephalopod.

Yes, it is a stretch, but sometimes with this challenge I like to imagine I'm an alien illustrator with no concept of what animals humans would regularly encounter. While most humans would probably assume this is a terrestrial mammal, there's no reason an alien would. In fact, considering how many more invertebrates there are then vertebrates, it makes sense for an outside observer to assume any animals described by humans is an inveterate, unless it says otherwise. It's all very sound alien logic, and not just me making wild leaps because I want my imaginary bestiary to have some more variety beyond my favorite birds and mammals. I'm really trying to use this challenge to be more imaginative and crazy with creature designs, and think outside the box when I can.

Anywho, the cuttlefish and nautilus were my main points of reference, though I did look at some reconstructions of prehistoric cephalopods for inspiration. Then I simply took all the elements of the Mlekragg and slapped it onto that body form. The triple row of teeth can't be seen in my drawing, but it is located where a cephalopod's beak would typically be. The 'face of a man' is actually a pattern on it's hood it uses to fool predators. Behind the hood flares out a 'lion's mane', which it uses for display and also to disorient it's prey when it snatches it up. It has a pointed "tail" with a stinger. It doesn't look much like a scorpion's tail - took a bit of artistic liberty and decided it just stings like a scorpion's tail, rather then looks like it. I've decided to interpret 'powerful feet' and 'good jumper' as two different traits. So it's 'powerful feet' are it's tentacles, but it uses it's stinger to leap. Why does a sea creature need to leap? Well, I imagine they live near coasts and occasionally get stranded in tide pools or on land and use their stingers to propel themselves back into the water. It kind of works like a springtail's little 'tail'. Much like the description says, no obstacle can keep the Mlekragg in!

On the bottom right I've drawn a picture of one using it's stinger to leap, and on the left I've drawn a cartoon version of it that accentuates the lion shape/human face idea. With it's tentacles and mane laid back and it's fins hanging down it does look like a little leaping lion. I also gave it a little grin in keeping with the cartoon tradition of putting cephalopod mouths on the mantle, which we know is incorrect. It does make him look like a very personable little gentleman though.

I feel if I were a bit more confident in drawing cephalpods and knew more about mollusk anatomy I could've maybe taken this in an even wilder direction. Maybe I'll revisit it in the future.

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Wutugald

#for a challenge to draw animals described in the Aberdeen Beastiary without knowing what they are#wutugald#maniculum bestiaryposting#sketch#creature design

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

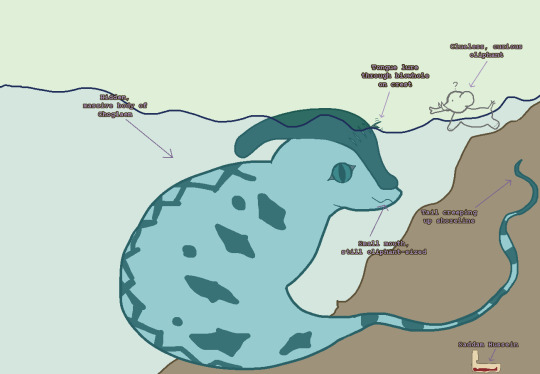

The huge and ravenous Choglaem, with a helpful diagram for all its Choglaem parts (ft. a special guest)...!

#Choglaem#maniculum bestiaryposting#my art#turned into sort of a dinosaur snake tsuchinoko?#could have made it more like a worm but the blowhole-tongue thing hooked me for chordate#i'll try some invert rep for the next one#the wutugald counts! :P

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don’t ask me why my interpretation of Wutugald ended up being so unsettling; it just did

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

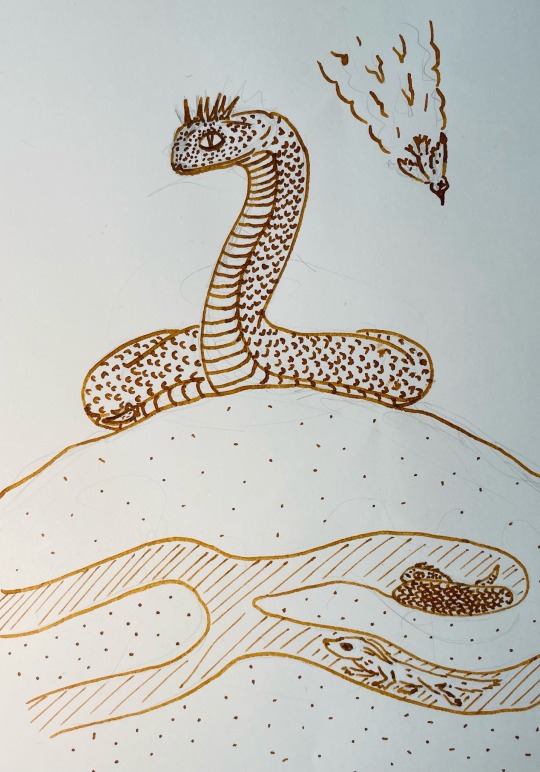

The deleterious Gaersnae

My response to this week’s BestiaryPosting challenge, from @maniculum

Pencil sketch, then lines in Sailor fude nib fountain pen, using Diamine Sepia ink.

Thought process under the cut…

"[Etymology redacted] … it is the king of crawling things, who flee when they see it, because it kills them with its scent. It will even kill a man just by looking at him. Indeed, no bird can fly past unharmed by its gaze but, however far away, will be burnt up and devoured in its mouth. The Gaersnae can be conquered by weasels. Men put them into the caves where the Gaersnaes lie hidden. The Gaersnae, seeing the weasel, flees; the weasel pursues and kills it. For the Creator has made nothing without a remedy. The Gaersnae is half-a-foot in length, with white stripes. Gaersnaes, like scorpions, seek out dry places; after they have come to water and bite anyone there, they make that person hydrophobic and send them mad. The creature called [redacted] is the same as the [redacted], or Gaersnae; for it kills with its hiss before it bites or burns."

Okay, so the king of crawling things. This was where I had to make my first decision; what kind of creature is the Gaersnae? I was 90% sure I was going to draw an invertebrate for this one (since we don't get much opportunity to do so), but I ended up making it a serpent given that the definition of 'crawling' seems to be mostly focused on going about on your belly.

There is also the note of hissing (obviously some insects hiss by expelling air from their spiracles, like the adorable Madagascar hissing cockroach), and its gaze (I imagine that snakes have -slightly- better eyesight than most bugs…).

The 'kills them with its scent'? Well, some serpents such as the hognose snake release a foul odour when playing dead, so perhaps it's a variation on that?

As we mentioned, it is the king of crawling things, and what is a king without a crown? When I was thinking of making it an invertebrate I considered making it look a little like a royal sceptre, with an egg-case resembling an orb & cross, but the horned viper literally has a horn-like scale above each eye (that can be folded back when traversing burrows); just expand that number by a few, and hey presto, one snake with a crown!

(I also gave it a pelvic spur for extra rizz - not that any venomous snakes have this, but it's pretty cool.)

As an aside, did you know that birds probably evolved earlier than snakes? :)

I was going to represent the stripes, but when I got to inking the scales I got carried away and forgot (imagine that some of the scales are different colours!).

I'm not quite sure how its burning gaze works, but have a bird crashing down to earth behind it (it'll grab that as a snack later!).

In the burrows beneath the earth, we can see that some mean ol' person has released a hreksong to go hunt the gaersnae - seems like everyone in the bestiary likes to hate on snakes :(

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

A bit earlier this time: the third Maniculum Bestiaryposting entry, the Choglaem!

A big snake with a small mouth, a crest and a long tail for wrapping around things seemed very straightforward, so I decided to add some wings to help it cause "the air to become turbulent" when coming out of its cave.

Obviously, I couldn't pass up the opportunity of drawing a medieval interpretation of an elephant! This one is based on the illustrated Bestiaire of Guillaume le Clerc.

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Its strength lies... in its tail and it kills with a blow rather than a bite"

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meadmaking

Hey all, Zoe here - the other half of this blog, and I decided to try my hand at posting - particularly my little mead-making project.

Even though Mac is the medieval drinks expert, I just like mead as a drink and I feel like a potion-brewing witch when I make it. Beer was the more popular drink during the middle ages, as it was cheaper and more widely available, but I think it's nasty and who doesn't want to feel like Early English royalty?

As I dug into mead-making, I fell into a SUPER deep medieval-mead-making rabbit hole.

I'm not a mead expert, and I'd highly recommend Susan Varberg's blog, Medieval Mead & Beer, for a very, very in-depth look at how to make medieval mead. HOWEVER, all that said, I did collect some research and played with it myself. Plus, I made some of my own recipes.

So. Mead.

What is it? Fermented honey water, in its most basic form. Honey-wine, it can be called to those who aren't familiar. There's a lot of other names mead has when it's mixed with other things:

Mead – water, honey and yeast

Sack Mead – mead made with extra honey

Short Mead – low honey and low alcohol yeast to be drunk quickly

Hydromel – watered down mead (in period, another word for mead)

Braggot – (period) ale refermented with honey; (modern) malted mead

Melomel – mead made with fruit

Mulsum – mead made with fruit

Cyser – mead made with apples

Metheglin – mead with spices

Pyment, Clar – mead made with grape juice

Hippocras – spiced wine, sweetened (but not fermented) with honey

Botchet — caramelized honey mead

Really, though, when you see it on the shelf, a pumpkin melomel will be marketed as "Pumpkin Mead," so really only the brewmasters get into the weeds on the names.

I was really curious as to how the ingredients were sourced in the middle ages - nowadays, brewers get really into where they source their ingredients (there's a bazillion different yeasts you can use!), but after doing some research, turns out the medievals were too!

Honey.

The medievals categorized honey in different ways. The best quality honey was called "life honey" and was the honey that dripped freely from the wax when pierced. Grades of honey diminished as the honey became harder to get out of the hive. The dregs of honey (collected by heating the frame in water to blend the honey but not melt the wax) was given to servants and was not preferred.

Honey was also categorized by location - Egyptian honeys were very popular and expensive. Honey from different regions in Spain were considered of different quality - one merchant got particularly fussy when one of his batches was "spoiled" by mixing honey from a better region with that from a worse region.

Finally, honey was categorized by flower type. One monetary requested honey made only from lavender. Since hives were highly mobile frames or skeps, it would have been possible for apiarists to move their hives to lavender fields.

Water.

Water is, well, water. Right? Not quite. Medieval recipes do specify using fine, spring water. The water and honey were often boiled together - likely to kill bacteria. However, the wording on "boille" is not super clear. Mead-masters knew that honey shouldn't be boiled (it kills natural yeast), so whether or not the must (the water/honey mix) was boiled in the modern sense or just warmed is unclear. Perhaps the need for "fine, spring, fresh water."

Yeast.

While modern brewers and vintners have a wide variety of yeasts to choose from, medieval brewmasters didn't have as many options. There were a few different options, however. Baking yeast (like a sourdough starter) was one option, while other recipes call for the leftover lees of wine/mead batches. Hops were also used. Of course, yeast is also naturally occurring, so brewers could fairly reliably rely on the natural yeast to kick-start itself.

I'll dump my own mead pics here and then get into the details of a Middle English mead recipe in part two, I guess. I'll talk a bit about the mead-making process, too.

Mead is made by mixing honey and water into a must. Then, yeast is added. Modern mead-makers also add yeast nutrients and other additions to ensure their batch doesn't get infected.

A newly made bottle of mead. Notice the cloudy colour characteristic of new mead. As the yeast eats the sugars, they'll create a bottom layer of debris and the mead will clear, as seen below.

After the primary fermentation has occurred (you can tell when the bubbles of gas, telling you the yeast is eating, have stopped), mead-makers will re-reack their mead. This involves moving it from one jug to the next.

At this point, the mead can be put into a closet and age for a while. The best meads have high clarity - that is, they're clear! The example below is only about 2 months old. It has a way to go, but has good clarity already. Notably, the sagas state that the best, oldest, clearest meads were served to Odin and the gods.

Anyway - that's the basics of mead-making. I'll make a part two about older recipes!

Sources:

Beekeeping in late medieval Europe: A survey of its ecological settings and social impacts. Llu.s SALES I FAVÀ, Alexandra SAPOZNIK y Mark WHELAN

Trade, taste and ecology: honey in late medieval Europe. Alexandra Sapoznik, Lluís Sales i Favà & Mark Whelan

Of Boyling and Seething: A re-evaluation of these common cooking terms in connection with brewing. Susan Verberg.

#bees#beekeeping#mead#mead-making#mediveal#medieval literature#witches#cottagecore#potions#i feel like a witch#maniculum

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wanted a go at the Wutugald! I accidentally guessed what the creature really is, but these are the conclusions I came to before that.

I decided it must be a fairly sizeable animal if it's going to eat dogs and shag lions. I also think the references to tombs and digging up bodies suggest burrowing, so I gave it burrowing claws like a mole.

There's a reference to it walking round and round animals, so I thought a long dragging tail would make that look more impressive. Combining that with the rigid spine, I get a sort of crocodile image, except that it needs to be able to talk, so:

This was a terrible idea! Thanks, medieval bestiaries!

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here, as anyone could easily tell, is the Wutugald.

I drew this creature based on an anonymised medieval description by @maniculum . Here’s the description:

What do you think? Is this not the most accurate Wutugald you’ve ever seen? I think I’ve done at LEAST as well as a medieval monk operating on such a description.

If you guess what the animal is, remember to keep quiet. At the end of the week, wutugalds will be posted and their accurate modern name revealed.

#wutugald#maniculum bestiaryposting#the first thing I throw out there when sketching animals#is the spine#and the spine here inadvertently gave me a lot to build on#as will be apparent next week#you know for MSPaint this isn’t a bad medieval rendition#monks 🤝 me

69 notes

·

View notes