#moctezuma's headdress

Text

Long Live Mexico

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quetzal Feathered Headdress from Mexico dated around 1515 on display in the Weltmuseum in Vienna, Austria

The first known reference to this feathered headdress in Europe occurs in 1596, as the "Moorish Hat" in the inventory of the collection of Archduke Ferdinand II of Tyrol at Schloss Ambras. Ferdinand collected objects of cultural signigficance for his castle to make a museum that was part of his efforts to promote the Renaissance in the Empire.

Before this it was thought to have been the headdress of Emperor Moctezuma Xocoyotzin II of the Aztec Empire however the provenance of this is uncertain. This is due to it not matching any other illustrations of such headdresses.

The headdress arrived in Vienna in the early 19th century. During a restoration in 1878, feathers and metal elements were supplemented. Since at that time it was assumed that the object was originally a type of standard rather than a three-dimensional piece of headgear, it was flattened to fit that image. Due to it's fragility there can be no further interventions and this is the reason given by the museum as to why it cannot be repatrioted back to Mexico. Activist, lecturer, writer and dancer Xokonoschtletl Gómora has campaigned for it's return to Mexico.

Photographs taken by myself 2022

#archaeology#art#history#aztec empire#mexican#mexico#fashion#16th century#weltmuseum#vienna#barbucomedie

87 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pre-Columbian Statue Found in Mexico

The 6.5-foot-tall statue was found in a citrus orchard.

The region was ruled by the Huastec civilisation, an indigenous people of Mexico living in the La Huasteca region that includes the states of Veracruz, Hidalgo, San Luis Potosí and Tamaulipas – concentrated along the route of the Pánuco River and along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico.

Excavations of Huastec sites suggests that the culture emerged around the 10th century BC, with the most active period being during the Postclassic era between the fall of Teotihuacán and the rise of the Aztec Empire.

During the mid-15th century AD, the Huastecs were conquered by the Aztec during the reign of Moctezuma I (AD 1398–1469) but retained a large degree of local self-government by paying tribute to the Aztec Empire. The Huastec civilisation fell during the Spanish conquest between AD 1519 and the 1530s and were subsequently transported to the Caribbean to be sold as slaves.

The statue was discovered by workmen during road works in Hidalgo Amajac. According to archaeologists from the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), the statue dates from the Early Postclassic period (AD 1100-1200) and was likely removed from a public space and buried for protection.

The statue measures 1.54 metres in height and weighs between 200 and 250 kilograms. It depicts a local ruler wearing a ceremonial headdress, similar to statues of rulers found in the pre-Columbian city of El Tajín.

This is not the first statue found in the Hidalgo Amajac area. In 2021, a 2-metre-tall statue called the “Young Woman of Amajac” was found in an orange grove depicting an indigenous woman wearing a headdress and an ankle-length skirt.

The mayoress of Álamo Temapache, Lilia Arrieta Pardo, announced that the cultural space currently being built in Hidalgo Amajac will be adapted to display the statue and the “Young Woman of Amajac”.

#Pre-Columbian Statue Found in Mexico#Huastec civilisation#sculpture#statue#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient art

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

About two or three weeks ago i said i would make a post about my opinion on Namor wearing a penacho in the new Black Panther movie, so sorry for the delay i'm currently working on my senior thesis and my mind is all over the place right now, but i'm taking advantage of my insomnia and my need for a distraction to finally talk about this:

I knew that Namor would wear a penacho since the first look at the character got leaked, but I remained hesitant since it looked more like a helmet and the helmets were worn by high rank warriors in allusion to animals that represented deities with the belief that if they wore them they would be granted the abilities of those animals in battle (sounds familiar?), but with the new trailer for the movie I think it was practically confirmed that the penacho is Namor's crown.

Why this bothers me? Well penachos were never crowns! Actually the rulers of different mesoamerican civilizations wore as 'crowns' the xiuhuitzolli (a turquoise and gold tiara) or the copilli (a small feather diadem).

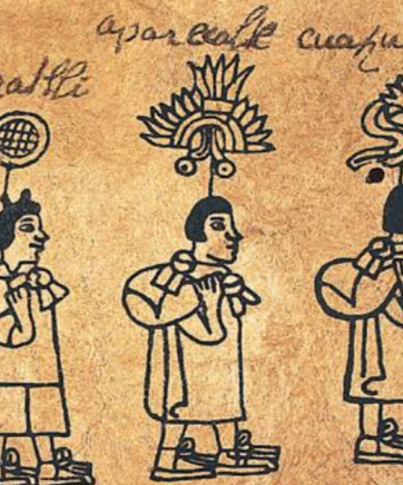

Penachos, or quetzalapanecáyotl/apanecatl in náhuatl, were this big feather arrangements worn by priests (called teomamaque) or warriors during rituals tied to their backs, never as a headdress.

The reason penachos are believed to be crowns is thanks to the wrongly called 'Penacho of Moctezuma', that thing was most likely a diplomatic gift from the mexicas to the spaniards (before the genocide) and went on to be marketed across Europe until it reached Austria, where it is exhibited now at the Weltmuseum Wien. When it was 'rediscovered' historians back then didn't know what it was, with a little research they discovered that it came from México and since they thought it was very beautiful, their logic was that it could only belong to royalty, so they attributed it to Moctezuma, one of the last mexica emperors.

And I know that this is fiction and the production can take their liberties, but the reason why this irks me is because for a long time mexican politicians have used that headdress as a symbol of their nationalist rhetoric and it eclipses the other artifacts that are in european museums and were actually stolen and have more historical value to the cultures they belong to, and i'm not saying that the penacho is not important but politicians have tainted it's historical value so horribly and even continue to teach that false story of the penacho as a stolen crown in basic education for the sole purpose of its bs propaganda despite the fact that it has already been proven wrong by many historians and anthropologists, so that a mainstream production uses a penacho as a crown takes away my hope that this will change in the future.

And look, i'm aware that this is hollywood, this is disney, and I know that I will probably receive some comments saying that these cultures are not more special than others to say that they should be respected, believe me I know, I received many comments like this the last time I spoke about this, but if a big company is not willing to learn and represent properly, shouldn't we be more open to learning and educating so that our history is not more distorted than it already is?

#i'm just really passionate about history thats all#namor#namor the sub mariner#black panther wakanda forever#mcu#marvel cinematic universe

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Poet Prince of Texcoco

“O friends, to a good place we’ve come to live, come in springtime! In that place a very brief moment! So brief is life!” -Nezahualcoyotl

In the downtown Zocalo district, there is a small monument that you could easily miss unless you were looking for it. It is the Garden of the Triple Alliance, a peaceful monument to a violent empire. The Triple Alliance is a term used to describe the trio of Nahuatl city-states in central Mexico, Tenochtitlan (what is now Mexico City), Texcoco and Tlacopan, that together conquered much of what is today Mexico. While their dialects and religions varied slightly, they came from similar ancestors and had similar cultures. This small, quaint garden is a funny way to commemorate an empire that expanded through war and conquest, and would at times require sacrificial victims as tribute. The Alliance’s oppression and subjugation of other Mesoamerican peoples, such as the Tlaxacala and Toltecs, led in part to their fateful decisions to help the invading Spanish. But today this park is a lovely and peaceful spot amidst the chaotic churn of downtown.

Also commemorated in this park is Nezahualcoyotl, the prince of Texcoco. Born in 1402, Nezahualcoyotl (often translated as “Hungry Coyote”) became prince of his territory at the young age of fifteen, but was overthrown and forced into exile. Nezahualcoyotl would spend three years fighting and return with an army of 10,000 soldiers to return his family and regain his throne. As prince, Nezxhualcoyotl supported the artists and philosophers in his kingdom, and encouraged education. In the incredible historical novel Aztec, Nezahualcoyotl is portrayed as a cautious and clever leader, in contrast to the egotistical and ambitious, younger Moctezuma. Rebuffing Moctezuma’s desires to continue to use their armies to expand the empire, Nezahualcoyotl wisely plans to conserve his kingdom’s resources for whatever dark forces are amassing in the east. At that point in the novel (and history), both Moctezuma and Nezahualcoyotl have heard reports of strange, white men appearing on the eastern coast, and Nezahualcoyotl is proven right to view this threat as gravely serious.

There is something romantic, even cinematic, about this figure: A prince in exile, a warrior poet fighting to retake his kingdom. Later a wise, older ruler who can see the danger and destruction that is to come. There is of course, something deeply tragic about Nezahualcoyotl, too: He was a man who may have sensed his civilization would soon face an existential threat, and even with his foresight, knew there was very little he, or anyone, could do about it.

Nezahualcoyotl survives today not just in history, but in his writing. He is considered to be one of the greatest poets of ancient Mexico. The royalty and nobility of the Triple Alliance were expected to be well educated in many subjects, and nobles were taught how to use both the pen and the sword. There are some historical parallels with the samurais of Japan and the scholarly nobles of ancient Greece and Rome. It is amazing that we still have access to his poems, considering that poetry and literature at that time was often times memorized and reproduced orally, as well as the fact that there was great literary and cultural destruction by the Spanish in the generations after the Conquest.

Here is an excerpt of a poem written by Nezahualcoyotl, perhaps reflecting on his own experience of war and reconquest:

The battlefield is the place: where

one toasts the divine liquor in war,

where are stained red the divine

eagles,

Where the tigers howl,

Where all kinds of precious stones

rain from ornaments,

where wave headdresses rich with

fine plumes,

where princes are smashed to bits.

Here is another excerpt of a poem that is kind of like a pre-modern take on “these are a few of my favorite things”:

I love the song of the mockingbird,

bird of four hundred voices;

I love the color of jade

and the drowsy perfume of flowers;

but more than these, I love

my fellow human beings.

In recent years, as Mexico has strived to decolonize their national identity and intentionally celebrate their long ignored indigenous roots, Nezahualcoyotl has been frequently honored as a wise and fair ruler in Mexican history. There is a neighborhood named after him in Mexico City that, true to the character of the man, is home to many artists. He is even honored with his likeness on the 100 peso bill.

But I imagine the actual man would take all this recognition in stride. Like another poet who once famously wrote “nothing gold can stay”, Nezahualcoyotl also wrote about the impermanence and ever changing nature of life:

Truly do we live on earth?

Not forever on earth; only a little while here.

Although it be jade, it will be broken,

Although it be gold, it is crushed,

Although it be quetzal feather, it is torn asunder.

Not forever on earth; only a little while here.

#travelgram#mexico#cdmx#historiamexicana#mexicanhistory#aztec#poesiamexicana#mexicanpoetry#poetry#literature#triplealliance#triplealianza#parks#texcoco#history

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

When, almost at the end of the causeway, they reached the arch that led to the natural islet at the heart of the empire—it’s like the Cité in Paris, said Aguilar—they were met by Moctezuma’s party. Capes of iridescent feathers and cloaks in colors they hadn’t known existed; men in the shelter of canopies, and, behind them, hieratic maidens more simply dressed but made up as if they had just arrived from another world and were still adjusting to this one. The warriors wore skins and headdresses representing their guardian animals. Caldera’s crested helmet—so bold and dashing, so gallant and Spanish—seemed about as majestic now as a bagpiper’s bonnet.

from You Dreamed of Empires, by Álvaro Enrigue, trans. Natasha Wimmer

#quotes#you dreamed of empires#alvaro enrigue#natasha wimmer (trans.)#historical#literary fiction#books

0 notes

Text

When, almost at the end of the causeway, they reached the arch that led to the natural islet at the heart of the empire—it’s like the Cité in Paris, said Aguilar—they were met by Moctezuma’s party. Capes of iridescent feathers and cloaks in colors they hadn’t known existed; men in the shelter of canopies, and, behind them, hieratic maidens more simply dressed but made up as if they had just arrived from another world and were still adjusting to this one. The warriors wore skins and headdresses representing their guardian animals. Caldera’s crested helmet—so bold and dashing, so gallant and Spanish—seemed about as majestic now as a bagpiper’s bonnet.

from You Dreamed of Empires, by Álvaro Enrigue, trans. Natasha Wimmer

#quotes#you dreamed of empires#alvaro enrigue#natasha wimmer (trans.)#historical#literary fiction#books

1 note

·

View note

Link

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

fuck france for auctioning stolen aztec art

#seriously#everyone tried to stop them and they just didn't give a fuck#it was over a hundred pre columbian pieces#and over 90 were aztec and part of mexico's cultural patrimony#all that lost over some selfish dumb white dudes#i'm pissed#this is Moctezuma's headdress all over again#Mexico

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's start with not calling Malintzin a "consort" or concubine or lover or anything that implies some romantic relationship between her and Cortes--as shown in this ridiculously idealized image.

Cortes had a couple Spanish mistresses with him on his expedition. History ignores that fact, it's easier to go with the cliche of a romance between the white conqueror and Indigenous maiden, a kind of Pocahontas myth.

Marina/Malintzin (no one knows her original name) was a teenage sex slave given to Spaniards without previous knowledge of Anahuac geopolitics or city-state military logistics.

Since Cortes had brought at least two Spanish mistresses, at first he gave away the Indigenous girls given to him in tribute. These girls were more valuable to Cortes as gifts for his followers. Cortes’ ability to persuade his men depended on his ability to reward them.

Distributing Indigenous girls to Cortes’ men caused problems. Bernal Diaz complained in his memoir: “The finest of the Indian females had been set apart (by the captains), so that when it came to a division among us soldiers, we found none left but old and ugly women.”

After the Spaniards took Tenochtitlan in 1521, Cortes had coercive sexual relations with Malinche and Tecuichpo. Malinche bore Martin in 1523, and Tecuichpo bore Leonor in 1528. Both children were considered illegitimate but were officially acknowledged by their father.

Defenders and critics of Cortes agree that Cortes was a “womanizer.” Cortes had at least half a dozen children from his two marriages, plus another half-dozen with other women, mostly Indigenous girls. The enduring images of Cortes and Malinche as a romantic couple are nonsense.

Unfortunately, this nonsense continues in the latest retelling of the invasion of Mexico. "Hernan," a Spanish-centric TV series made in 2019, perpetuates this damaging myth.

Myths of Malinche

The story of the Aztec's downfall has often been told replete with myths — such as Cortés being mistaken for the returning deity Quetzalcoatl, or Moctezuma wearing green feathered headdresses. But it’s the translator Malinalli, commonly known as Malinche, who suffers most from mythologizing. History can't confirm that "Malinalli" was her original name, and even "Malinche" is a misnomer.

With the emergence of the New Philology and New Conquest History revisionism of the 1970s, the myths surrounding the (in)famous La Malinche have been reexamined. Unfortunately, lazy research in many histories and essays on the subject continues to blur the line between fact and fiction. Here are some of the most common mistakes, rectified.

Out of the Frying Pan

Malinche’s entrance into the narrative of the conquest is confusingly portrayed from the start. Along with other young women, food, textiles, and gold, she was part of a tribute the Maya gave to the Spaniards after losing a battle. Most histories avoid facing the uncomfortable fact that these women were meant for sexual use. Instead, writers mention how the Maya brought food to the victorious Spaniards and gave them twenty women, one of whom was a teenage girl named Malinalli Tenepal (Malinche’s supposed original name), to “cook meals.”

The notion that those twenty girls were cooks originates with Cortés’ secretary, Francisco Gomara, who wrote one of only two histories based on firsthand accounts: “They brought [Cortés] twenty female slaves to bake bread and prepare meals for the army.” In his book Cortés, the Conqueror, Gomara tries to make his patron look good and plays down certain acts that may seem immoral.

But Cortés already had female cooks among the many Cuban servants in his expedition, and didn’t need more cooks. Gomara’s initial description of the girls’ purpose is pretext. Many commentators overlook a sentence elsewhere in Gomara’s account that reveals the girls’ true fate: Cortés “distributed the twenty slave women among the Spaniards as companions.”

Bernal Díaz, who wrote the other firsthand history, confirms that Indigenous girls were given as sex slaves to Spaniards on multiple occasions. Díaz even complains that the better looking girls went to captains, not common soldiers.

For these women, their destiny was to be mistresses or sexual slaves. On one hand, they were abducted by the Spanish, who took them away as companions. Some were given away as slaves or in the case of the nobility, as the 'wives' of the Spanish to create alliances. In any case, their destiny was not in their hands,” says Miriam López, a Dr. in Anthropology by the UNAM's Anthropological Research Institute.

The researcher adds that “La Malinche” was sold as a slave twice before she could show Hernán Cortés that she could translate, that “innate ability to understand different cultural contexts and learn new languages.”

Royal Relations

Díaz gives us interesting details about how the Spaniards reconciled their religious faith with their actions. How does Catholicism solve the problem of heathen sex slaves? Start with a baptism. Malinche was baptized as "Marina." After the girls were anointed and christened in a Catholic ceremony, Díaz reports, “Cortés gave one of them to each of his captains, and Marina [Malinalli/Malinche]… went to Alonso Hernández Puertocarrero.”

The baptism of Indigenous women was not uncommon and existed to ensure that sexual relations, no matter how forced, were within the purity of the Christian faith. Acts such as these remind us of the excuse of religion to ensure the oppression of non-Europeans during the era of colonialism.

The assigning of Malinche to Puertocarrero is a story unto itself. Puertocarrero was cousin to the Earl of Medellin of the Crown of Castile. As such, he was the closest thing to royalty on the expedition, and thus he was Cortés’ most favored captain. It was important to keep Puertocarrero happy. Malinche apparently stood out from the other girls — Díaz and some fragmentary testimonials attest to her proud bearing and intelligence. By assigning Malinche to Puertocarrero, Cortés was giving him the best of the girls as a political favor.

Ultimately, the arrangement also helped augment the story that La Malinche (Doña Marina to the Spanish) herself came from royal background, and therefore was capable of great deeds. Malinche’s storied noble ancestry may have begun as a joke about matchmaking a royally associated Spaniard with a royal "savage", but it ended with a legacy that rivals any fable.

The Plot That Wasn’t

After she was acquired by the Spanish, Malinche temporarily disappears from the written record. She was downplayed as an unnamed translator during meetings between Spaniards and Mexicans.

She pops up in the story again months later, when Gomara and Díaz say Malinche gave Cortés evidence that the Aztec-allied city of Cholula was plotting against the Spaniards. In actuality, Cortés had been planning an attack on Cholua and just needed an excuse. So Cortés told his men that Malinche informed him about a Cholulan plot to kill the Spaniards. This justified his attack on Cholula as a “preemptive” strike.

As far as we know today, Malinche did not provide any such information. Cortés pulled off an effective reversal by blaming his own actions on the Aztec and their allies, while also unknowingly laying the groundwork for Malinche’s reputation as a betrayer of her people.

The First Mestizo?

Another pervasive myth is that Cortés took Malinche as his concubine during the conquest, after Puertocarrero returned to Spain. But Cortés was given other girls during that time, including Moctezuma’s own daughter. There's evidence from historian Hugh Thomas that Cortés brought one or two of his Spanish mistresses from Cuba. For Cortés, females were replaceable, whereas Malinche was the only person who could translate and give Cortés diplomatic advice during meetings with the natives.

With an empire at stake, Cortés couldn’t risk having such a singularly important asset sidelined by pregnancy. Only after couple years after the fall of the Aztec capital did Malinche spend a brief time at Cortés’ home where he had coercive sexual relations with her. She became pregnant and was quickly married to another Spaniard.

Cortés’ son by Malinche, Martín, is often inaccurately cited as Mexico’s first mixed-race child or mestizo. Although we may never know for sure, that distinction most likely goes to the children of a Spanish castaway named Gonzalo Guerrero and the Maya princess Zazil Há.

Experts says that in time, Malintzin became the Cortés' sex slave: “He didn't show her affection and reduced her to 'the tongue,' as his translator, although she gave birth to his first son (Martín Cortés), who was recognized by the colonizer. Nevertheless, Cortés separated Martín and Marina to take him to Spain and she never saw him again.”

Guerrero was shipwrecked in 1511, cast ashore in the Yucatan with a dozen Spanish survivors. By the time Cortés’ fleet arrived eight years later, only Guerrero and one other Spaniard were still alive. (See Aztec Empire Episode One) Guerrero integrated himself with the Maya and had a family with the local chieftain’s daughter, never returning to the Spanish way of life.

Origin Myth

In the aftermath of the conquest, as Spain sought to strengthen its slim hold on this new empire, the story of Cortés and Doña Marina (Malinche) came to symbolize a romanticized version of the colonial relationship — and the birth of a new people. By contrast, Guerrero’s story was about a Spaniard who wholly converted to the local culture and whose status partly depended on his wife, which is not an empire-building narrative.

In her book La Malinche in Mexican Literature: From History to Myth, Sandra Cypess observes:

“By studying how the official discourse and the people have treated the two couples, we realize that the interactions between Malinche and Cortés became emblematic to indicate how the relations between European and indigenous should be. She is the woman who should act as subaltern and accept the language, culture, political and economic structures of man, not vice versa.”

No images of Malinche were created while she was alive — the only images we have of her are posthumous. Several Spanish illustrations and Spanish-commissioned native codices depict her with hair parted in the middle and worn loose to her shoulders, echoing the hairstyle of the Catholic Virgin Mary.

In reality, Malinche wore her hair in a traditional double-braid, as seen below.

Stereotyped portrayals of Malinche continue to this day, in some cases egregiously wrong, as seen in the below example from a 2016 Spanish TV series.

*edited 11/18/21 for the addition of more information.

Sources: (x) (x) (×)

#mexico#indigenous#malinche#malintzin#hernan cortes#spain#🇲🇽#bernal diaz#aztec#Tenochtitlan#Tecuichpo#mexican history#history#maya#cuba#Francisco Gomara#catholiscism#religion#christianity#europe#colonization

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

Man your ishtar gate post...for mexico it’s moctezuma’s headdress. It was pillaged from his palace during the fall of tenochtitlán and cortéz gave it as a “gift” to the spanish royalty, which then ended up in the hapsburg’s posession and is currently in austria on exhibition in vienna. “Oh we can’t give it back because you people don’t have the installations to care for it properly and you’re so corrupt you’d probably lose it or sell it to narcos.” So there’s a sad replica in mexico city that looks, well, obviously fake compared to the real thing. Then there’s how christie’s keeps auctioning off mesoamerican artifacts and coyly claiming they would never sell trafficked items (despite having being caught doing that multiple times) and how our history institutes have to grovel to europe and angloamerica to not sell our stuff.

AAAAAH OF FUCKING COURSE THE WHITES WOULD HAVE MOCTEZUMA’S HEADRESS I HATE COLONISTS SO MUCH!!!! I HATE THE SPANISH AND I HATE AUSTRIA??? WHAT THE FUCK???? I HAVE TO GO TO AUSTRIA TO SEE THAT SHIT?????????????????? LMAOOOOOOO WHAT THE FUCK mexico isn’t allowed to have shit now???? god i hate looters so much

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mexico urges Austria to return Moctezuma's headdress

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘’It’s not a surprise that the headdress belonging to Moctezuma is really especial to mexican citizens, just as it is to us, the piece has been in Europe for a long time’’- Sabine Haag, director of the Museum of Art and History of Viena

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amazon is producing a Hernan Cortes miniseries on the Conquest of Mexico. I have some issues with it, but at least when it comes out I’ll be able to bitch and moan about everything it does wrong while praising what it does right.

The first thing that gave me an impression of something good, or at least semi-accurate. They’re actually depicting Tecuelhuetzin, a princess of Tlaxcala. She’s almost always ABSENT when depicting the Conquest of Mexico.

Things that irk me. They made Moctezuma way too old, and way too big. His headdress is all wrong. Easily the most common mistake AND YET ITS STILL THERE.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Seated Deity (Macuilcoatl)

Date: 15th–early 16th century

Geography: Mexico, Mesoamerica

Culture: Aztec

This sculpture depicts a seated male with his legs drawn up to his chest. His posture is straight and open with his left forearm resting across both knees. The figure’s right hand, which was likely broken in antiquity or during the early Colonial period, is modeled around a small void. The figure’s open hand likely once held a banner, or flag-tipped staff.

Bearing the image of a hand carved in shallow relief across its lower jaw, this Aztec standard bearer represents one of the pre-Hispanic deities known as the Macuiltonaleque, or "lords of the five souls" (macuil, "five" + tonalli, "soul"). By reading the glyph sculpted on the reverse of the statue’s head, which depicts a coiled serpent surrounded by five dots, we are able to identify this figure as Macuilcoatl, or "5 Serpent." Associated with feasting, gambling, and games of chance, the youthful Macuiltonaleque embodied notions of pleasure, excess, and disease in pre-Hispanic Central Mexico. As denizens of the night, they were also thought to represent exalted warriors who, upon dying in battle, rose to the heavens to carry the sun disc on their backs from dawn till its midday zenith.

As spiritual guides, the Macuiltonaleque inhabited, or "possessed," the five fingers of native priests and mystics so that the latter might be allowed to predict future events, diagnose disease, or act as matchmakers. To complete this possession, it is said that the priest first had to cake his hand in a chalky salve of white lime and tobacco. Then chanting a series of sacred incantations, he called upon the gods of pleasure to descend into his ashen digits and thus allow him to articulate the prophetic visions revealed in his tonalamatl ("book of days"), a type of hand-made divinatory book used throughout Mesoamerica. The hand positioned under this standard bearer’s mouth thus underscores his role as a medium (or "mouthpiece") for these divine beings.

As with many of the conventionalized sculptural types associated with the Aztecs—such as the chacmool (a recumbent male figure holding an offering bowl above his chest) or the Atlantean "sky-bearer" figures—the origins of the standard bearer can be traced back to the Toltec culture of the Early Postclassic period (ca. 900–1000). Illustrations of standard bearers began appearing in European chronicles by the end of the sixteenth century. In his Primeros memoriales (ca. 1561), for example, the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún depicts a pair of figures—identified by their names glyphs as "5 Lizard" and "5 House"—holding plume-tipped staffs and crouching to either side of the Templo Mayor, the central religious shrine of the Mexica-Aztecs. (Aztec elites living in the imperial capital of Tenochtitlan referred to themselves as "Mexica," which is the origin of the modern-day name of Mexico.) Each of the figures depicted in Sahagún’s manuscript is adorned with a feather headdress and loincloth and displays a white, multi-lobed emblem over the mouth, analogous to the hand-on-jaw motif seen here. As most standard bearers lack any verifiable archaeological context, this colonial eyewitness account provides reliable evidence that such works were originally intended to frame and aggrandize important temples in the Aztec world.

William T. Gassaway, 2014–15 Sylvan C. Coleman and Pamela Coleman Fellow

-----

Resources and Additional Reading

Boone, Elizabeth H. Cycles of Time and Meaning in the Mexican Books of Fate. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007.

Easby, Dudley T., Jr., "A Man of the People." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin XXI, no. 4 (December 1962), pp. 133–140.

Hernandez Pons, Elsa C. "Sobre un conjunto de esculturas asociadas a las escalinatas del Templo Mayor." In El Templo Mayor: excavaciones y estudios, edited by Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, pp. 221–232. Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1982.

Klein, Cecelia. "Ideology of Autosacrifice at the Templo Mayor." In Aztec Templo Mayor: A Symposium at Dumbarton Oaks, 8th and 9th October 1983, edited by Elizabeth H. Boone, 293–370. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1988.

Nicholson, Henry B. "Major Sculpture in Pre-Hispanic Central Mexico." In Handbook of Middle American Indians, edited by Gordon F. Eckholm and Ignacio Bernal, 10:1:92–134. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1971.

Pohl, John M. D. Sorcerers of the Fifth Heaven: Nahua Art and Ritual of Ancient Southern Mexico. Program in Latin American Studies Cuadernos No. 9. Princeton: Princeton University, 2007.

Sahagún, Fray Bernardino. Primeros memoriales. 2 vols. Paleography of Nahuatl text and English translation by Thelma Sullivan. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993–98.

The Met

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mexico’s President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has asked the country’s Indigenous Mexica Peoples for forgiveness for the abuses inflicted on them during the bloody 1521 Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire.

Lopez Obrador on Friday spoke in front of a large replica temple built to commemorate 500 years since the fall of the ancient Aztec capital Tenochtitlan to Hernan Cortes, the leader of the invading Spanish forces who looted and razed the city.

“Today we remember the fall of the great Tenochtitlan and we apologize to the victims of the catastrophe caused by the Spanish military occupation of Mesoamerica and the territory of the current Mexican Republic,” Lopez Obrador said.

Lopez Obrador has said the Spanish monarchy and Roman Catholic Church should formally apologise for the atrocities committed during the conquest.

The president on Friday repeated previous criticisms that colonialists narrated history at their convenience.

“The conquest and colonisation are signs of backwardness, not of civilisation, less of justice,” he said.

Lopez Obrador has repeatedly blamed colonial-era abuses when setting out the origins of inequality and corruption in Mexico.

Areas with high concentrations of Indigenous people tend to be more impoverished, and thus closer to the electoral base of Lopez Obrador, who has pledged to put Mexico’s poor first.

As the anniversary approached, Lopez Obrador stepped up criticism of Spain and other European countries, including Austria, whose former ruling family, the Habsburgs, also sat at the head of a French-imposed Mexican Empire in the 1860s.

Last year, he pressured a Vienna museum to return Mexico a bejewelled feather headdress, considered one of the most important pre-Hispanic artefacts.

The headdress is said to have been worn by Aztec emperor Moctezuma before he was toppled by Cortes.

Despite a visit by Lopez Obrador’s wife Beatriz Gutierrez to the Austrian capital, the Mexican request was denied.

#🇲🇽#mexico#spain#europe#indigenous#austria#vienna austria#aztec#catholocism#christianity#religion#Moctezuma#hernan cortes#mexica#colonization#imperialism#native

6 notes

·

View notes