Text

Beatriz at Dinner (movie review)

In its adverts, Beatriz at Dinner claimed to be “the first great film of the Trump-era.” While this might not be the case, it is certainly the first overtly Trump-era film, in that it deals head on with a lot of the communication issues I suspect American society is going to be grappling with for the next four years. The success to which the film does this is varied, but when Beatriz works (which, thankfully, is most of the time), it flirts with greatness.

The titular character is a natural healer played by Salma Hayek, who ends up at a dinner party for one of her wealthy clients after her car breaks down. There, she butts heads with John Lithgow as Doug Strutt, an absurdly materialistic business tycoon and the antithesis of Beatriz in almost every way. However, as the night progresses, Beatriz begins to suspect that she has a deeper, more personal connection to Strutt, one which makes their increasingly tense interactions all the more sinister.

The obvious metaphors are obvious. Beatriz is an immigrant, an animal lover, and environmentalist, and basically stands against everything that Strutt stands for: greed, self interest, capitalism. He is Trump, she is the people on the other side of the wall. But the genuine tension in the movie comes from everyone else at the dinner. Much like Get Out, the real victims at the end of Beatriz’s satirical sword are the people in-between, who’d rather turn a bind eye to injustice than ruin a perfectly good dinner party. Left to on their own to work things out, the battle between Beatriz and Strutt would be brief and nasty, but when you mix them in with all these “nice” white people, the tension becomes unbearable.

Much of this is thanks to the performances. Hayek is fantastic, both graceful and awkward as she stumbles through a social minefield that feels increasingly rigged against her. Director Miguel Arteta frames her against all these tall, gorgeous women with their stiletto heels, making Beatriz feel like a child among ruthless adults. Lithgow gets to chew an appropriate amount of scenery, but his character’s brand of mustache-twirling objectivism never feels forced. When the movie allows him and Beatriz the space to argue and the rest of the guests to react, it touches on a powerful truth about 21st century politics that has gone largely untouched until now. Because for all Beatriz fights and antagonizes Strutt, none of it is going to change him or the other guests. Just like angry comments on a Facebook post, the dinner party becomes a vacuum chamber of good intentions, a quiet cry into and indifferent abyss.

However, once Beatriz the character starts to recognize this and take physical action, her film starts to loose its way. Character decisions start feeling forced, plot points feel added in for padding, and it all climaxes in an overly dramatic final scene that strains for poetry where pros would have been enough. It’s tough to discuss these missteps in detail without giving away spoilers, and I would definitely recommend seeing Beatriz at Dinner. But like a talkative dinner guest itself, the movie ultimately overstays its welcome. Not for too long, but long enough to make you wonder why Arteta and co. didn’t just stop when they had the chance.

But maybe that’s the point. “Why didn’t you…” is a question thrown at Beatriz throughout the entire movie. Why didn’t you just be quiet? Why didn’t you just sit back, smile, and suffer through this? Why did you have to speak up? They’re the questions you ask your freinds after they go on a long rant on Twitter, or after they unfriend someone because they voted for Trump. Why? Sometimes, doing the right thing is awkward, but in situations like the one in this film, what is the right thing to do? Even if it didn’t completely work as a movie, Beatriz at Dinner is bound to provoke discussion around that central question, and though we might not like the answers, they might just be the key to moving forward. To being better people.

OVERALL RATING: 7.5 / 10

SEE IT OR SKIP IT: See it.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

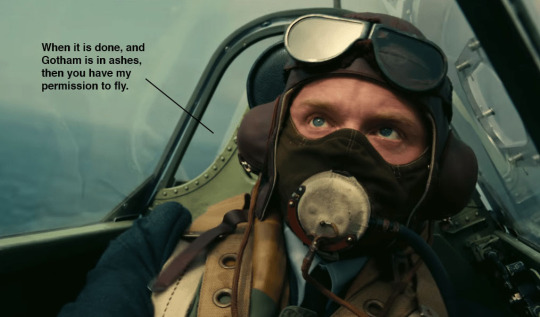

Dunkirk (movie review)

Out of all the subjects for director Christopher Nolan to make a war movie out of (and let’s be honest; a Nolan war movie was as inevitable as a Nolan space movie), the Dunkirk evacuation felt like a weird choice. Partially because it was seen as a giant logistical disaster and is thus scarcely discussed outside of WWII circles, and partially because the actual evacuation was about as far from a Chis Nolan movie as you could get. There were no metaphysical concepts to ponder on, no particular iconography to subvert or de-mystify. The Dunkirk evacuation was an ugly, messy, and a lingering nightmare for basically everyone involved.

And perhaps, that’s exactly why Nolan picked it. Great directors are always pushing the boundaries of their respective comfort zones, and more often than not, their greatest works come from their greatest risks. If 2015’s Interstellar was the epitome of Christopher Nolan’s comfort zone, Dunkirk is the opposite. And it might be his greatest movie yet.

The story follows three characters involved with the evacuation at three different times. The first is Tommy (a stark and understated performance by newcomer Fionn Whitehead) a young English soldier trapped on one of the beaches during the early stages of the evacuation. The second is Mr. Dawson (Mark Ryalnce, incredible as always), a mariner who sets off with his teenage son Peter and his friend George on their small boat to help ferry the soldiers back home. The third is a fighter pilot (Tom Hardy), who has an hour to cross the channel and make it to shore before his damaged fuel tank runs dry.

This unorthodox way of structuring the plot might be the most “Nolan” thing about Dunkirk, and the various time jumps give him ample space to flex his muscles as a director of parallel narrative. But as with his previous movies like Memento, Inception, and Interstellar, the intersecting timelines are less a gimmick than a means to a thematic end. By giving us three different stories to keep track of—each with their own unique set of stakes—Nolan racks up the tension and urgency, making for a viewing experience that feels as claustrophobic and stressful as I can imagine the real evacuation actually was.

There are a couple bits about honor and survival that the Nolan of Interstellar might have turned into a long winded Oscar-y monologue, but here, he’s largely uninterested in theme or meaning (save for a few minutes of sentimentality near the end). The performances, the design, the sound and cinematography are all simply tools to deliver the most nerve shredding experience possible. Every time a German bomber flies overhead, the seats of the theater shake with vengeful fury. We can hear the screams of trapped soldiers inside sinking rescue ships long after they have disappeared from frame. This is a lean, mean procedural thriller that doesn’t stop moving forward.

If Dunkirk isn’t the best straight war movie to come out in 2017, I’d be surprised (and scared) to see what comes next. Nolan has grasped the horror and desperation of fighting a battle you’ve already lost, something seldom explored in a market that tends to favor heroic stories of victory and success. By grappling head on with the frequently disastrous results of what Churchill deemed “a colossal military disaster,” he emerges with a movie worthy of his unique talents, and deserving of all the praise that is flying its way. Well done.

OVERALL RATING: 9 / 10

SEE IT OR SKIP IT: See it in a theater (or at home with a really really good sound system).

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Game of Thrones - Season Seven (TV Review)

(BEWARE: Spoilers ahead)

Why do we still watch Game of Thrones? No, seriously. We’ve all asked ourselves at one point or another, even the most devoted fans. I think it was around the end of season 5, after Cersei’s disgustingly pornographic walk of shame, when I really started to wonder why I continually subject myself to the tedious torment that can be watching this show.

But our relationship with TV is often a sado-masochistic one. Most “good” shows are on long enough to have more than a few rough patches, as any true fan of Lost can attest to. When you have something that is producing as much consistent content as an ongoing television program, there are bound to be things that you don’t like, episodes you’d rather forget, creative decisions that went nowhere. But so long as the reward outweighs the cost, we stick around.

Here’s the thing: Game of Thrones is objectively good. Solid, engaging, and well mounted television that features interesting characters, high stakes conflict, and (usually) exemplary writing. But if we watched things because they were “good,” Hannibal would still be on air. No, there’s something else about Game of Thrones, which has grown over its seven seasons into a cultural phenomena big enough to rival Harry Potter. That “something” varies from person to person. For some, it’s worth drudging through all the political nonsense for one of those kick-ass dragon scenes. For others (like me) the show is all about the politics, the nuisance, the tightly wound tension built up over years and years.

But regardless of which side of the wall you stand on, season seven was a huge turning point, either the moment when the show finally started to figure out what it was meant to be, or the moment when it lost sight of what made it so great. It is, if anything, pure evidence of television’s flexibility as an art form, its ability to mean different things to different people at different times.

The primary focus of season seven is the budding relationship between two of the “Game’s” biggest players; northern king and resident beef-cake Jon Snow, fresh off his deeply satisfying win against Ramsey Bolton at the Battle of the Bastards, and dragon den mama Daenerys Targaryen, who’s finally on Westerosi soil after wandering around in character development land for six seasons. Elsewhere in the world, Arya has finally returned home to Winterfel, only to find her estranged sister Sansa sitting on the throne. Cersei is still a megalomaniacal monster, Tyrion is still sassy as all hell, and Ed Sheeran is a Lannister soldier… apparently…

If you weren’t able to gauge from that description, season seven is all about reunions. It’s about putting characters who you haven’t seen speak to each other in years (and some who haven’t spoken at all) into the same room and seeing what happens. There’s enough pop in getting to see the Hound fight side by side with Jorah Mormont against a horde of White Walkers to carry us through a truncated season (only seven episodes), but the “everyone’s finally coming together” plot device carries with it some interesting problems that the show has never encountered before.

One of these problems is the dialogue. Game of Thrones always had good dialogue. But because so much of season seven is comprised of characters catching each other up on events and backstories watchers of the show are well versed in, many of the scenes fall flat. Interactions that should be ripe with tension come across as placeholders for the bigger actions scenes, which punctuate almost every episode in the season.

Another problem is time. You’ve probably already read about how fast that raven must have been flying to get to Daenerys in time before Jon and co. froze to death out on that lake, but I’m talking more about general pacing. There was more than enough material baked into season seven to warrant a full ten episodes, but show runners’ David Benioff and D. B. Weiss’ decision to condense what was already going to be a break-neck season speaks to a kind of urgency that is new to a show which is widely known for taking its sweet time. While I can’t fault people who complained about the meandering nature of some of the later seasons, I also wish some of the developments in this new season were given just a bit more time to actually... you know, develop. Danny and Jon’s relationship, authentic as it may be (Kit Harrington and Emilia Clarke have some astonishing chemistry) feels rushed, and could have benefited from just a couple more episodes worth of interactions. Tyrion re-connecting with Jamie after killing their father should have felt like a journey, not like a cut scene in a video game.

I’m tempted to give season seven a free pass solely for its finale, 80 minutes of pure TV euphoria peppered with some of the best performances I’ve seen on the show period. Cersei’s face at seeing a White Walker for the first time, Littlefinger trying to conjure up fake tears as he pleads with Sansa for his life. And that ice dragon. Ho. Ly. Shit. Perhaps the reward does still outweigh the cost. For me, at least. And only for now. I can assure you that I will be eagerly awaiting the final season next year. But a season finale is one thing, a series finale is another. A series finale takes tact, patience, and restraint to pull off.

Game of Thrones season seven was a lot of things: fun, exciting, fast. But patient it wasn’t, and I’d be lying if I said that didn’t make me a little worried going into season eight. Not too worried, but worried none the less.

OVERALL RATING: 7 / 10

SEE IT OR SKIP IT: See it.

0 notes

Text

Ingrid Goes West (movie review)

Go see Ingrid Goes West. I’m not going to wait for the end of the review. I’m not even going to give you a definitive rating first. Just go see Ingrid Goes West. I don’t care if you have to drive to the arthouse theater halfway across town. I don’t care if you have to wait till it comes out on Amazon. DO NOT read this review until you have watched Ingrid Goes West, so go see Ingrid Goes West.

Seen it? Good. Pretty crazy right?

Ingrid Goes West was inevitable. We were going to get the Instagram movie whether we liked it or not, and if that statement doesn’t sit well with you, you’re not alone. Despite living half of our lives in front of some sort of screen (like you’re doing right now), we don’t really like to watch movies about technology. It’s not entirely our fault; Hollywood has a notoriously hard time representing social media without the final product being written off as didactic (see Men, Women & Children) or self congratulatory (see The Emoji Movie). But perhaps we shoulder some of the blame. Perhaps watching movies about technology is too uncomfortable for casual audiences because we see a part of ourselves that we’re not very proud of, that we don’t like admitting exists.

Ingrid works, in part, because it embraces this discomfort. The titular Ingrid Thorburn (Aubrey Plaza) is the human personification of every bad quality we associate with social media: she’s obsessive, she’s narcissistic, she’s a pathological liar, and she expects other people to give her all of the love she stubbornly refuses to give herself. One of these “other people” is Taylor Sloane (Elizabeth Olsen, who between this and Wind River is having a phenomenal summer). Sloane is an Instagram “Influencer,” a term I had to look up after seeing the movie. We all know these people are; rich, beautiful (usually white) young women who’s social media profiles are plastered with tasteful pictures of them wearing expensive clothes, eating expensive foods, and traveling the world on an endless budget of smiles and rainbows. Their job, it seems, is being friendly, so Ingrid travels to Venice California to become Taylor’s best friend.

From then on, Ingrid plays with the beats of a standard romantic comedy (girl meets girl, girl looses girl, etc.) which only makes Ingrid’s abrasively strange behavior all the more uncomfortable. The obvious comparisons are obvious: Ingrid is acting out all of our own fantasies about the people we idolize on Instagram, and is meant to be a dark reflection of our obsession with social media blah blah blah. You’ve heard that schtick a thousand times, you were probably able to figure it out from the trailers, and while Ingrid is so well executed as a character study that it would have succeeded in it’s own terms, it’d have been disappointing if this unoriginal idea was the only thought the movie had on its mind.

Fortunately, it’s not. Ingrid Goes West is a character study in which the audience is the character, a deep, detailed examination into how we as viewers connect with the people we see on screen, whether those screens are big or small. This isn’t to say that Ingrid isn’t trying to get us to examine our own behavior, it just accomplishes that goal in such a clever, amusing way.

First, it’s important to understand how Instagram works. Sloane, like most influencers (or average Instagram users for that matter), is putting out the best image of herself, one that is kind, friendly, adventurous, etc. She wants us to believe that she’s a genuinely good person. She is, in a sense, telling us exactly what to think of her, and in the case of Ingrid, she succeeds. So much so that Ingrid is willing to stalk and harass her until the ugly—and much more authentic—side of Sloane comes out.

But all while this is going on, the movie is doing the same thing to us with Ingrid. Despite her unhinged antics, her devious manipulations and downright criminal tenancies, we keep rooting for Ingrid to succeed. Why? Because she’s a “real” person. The movie keeps dropping hints at her tragic past, her positive relationship with her late mother, her deeply human need for love and affection. We are, in a sense, being told what to think of her. We’re willing to excuse, or at least understand, her inhumane actions because the movie keeps telling us that there’s a real human standing behind that screen.

This all climaxes in a botched suicide attempt which Ingrid posts on her Instagram account (which you obviously know about because you totally saw the movie when I told you to… right?) This results in an outpouring of support from people all across the web. A shot of her phone shows us inspiring messages like “you can do it” and “we believe in you.” Ingrid has gotten exactly the love and compassion she wants… but what does that mean? Does that mean she won’t go on to stalk and obsess over more people? Does that mean she’ll try and seek professional help? Has she really learned anything?

The movie places the question squarely in the audience’s hands. But if we’ve learned anything from Ingrid’s journey with Sloane, isn’t it not to believe what you see of a person through a screen? Who are we, as viewers, as followers, as audience members, to support or criticize Ingrid, when our entire experience with her has been a carefully curated series of scenes and shots? What would a critical audience think of us, were they to be subjected to 97 minutes of our most shameful online activities? What would we say to them?

These are the real questions that Ingrid Goes West poses, and the answers are not pretty. Still, writer/director Matt Spicer deserves praise for finding such an interesting way of asking them. He brings the audience on one hell of a journey, toying with our relationship to the images up on screen for maximum emotional and dramatic effect. You don’t merely watch Ingrid go west; she literally takes you there, constantly turning back to ask the audience: are you sure you want to keep going?

Yes, Ingrid. Yes we do.

OVERALL RATING: 9 / 10

SEE IT OR SKIP IT: See it (but of course, you already have... haven't you???)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets (movie review)

Odds are that you’ve never heard of Valerian and Laureline. It was an immensely popular French comic strip back in the late 1960’s, one who’s unique visuals and world building left a lasting impression on those who grew up reading it, namely popular French filmmaker Luc Besson. If you haven’t heard of him, odds are you’ve heard of his films: Lucy, The Fifth Element, the Taken franchise and Leon: The Professional to name a few.

Benson has always been a fascinating filmmaker, an expert visual stylist who’s relentless optimism and kitchy predilections have placed him squarely in the “love-it-or-hate-it” corner of film criticism. Most people find his work entertaining, hollow, and more than a little weird. Me? I’m a little more sympathetic, in part because few mainstream filmmakers—on both sides of the Atlantic—have as distinctive a voice as Besson. Themes of vengeance, humanism, and cultural cooperation are consistent throughout most of his otherwise erratic filmography, which makes him the perfect person to bring Valerian to the big screen.

The set up is that seven hundred years in the future, an international space station has become the cultural hub for thousands upon thousands of different species from across the universe, expanding the station into a “city” of a “thousand planets.” Valerian (Dane DeHaan) is part of an intergalactic police force who, along with his partner/on-and-off-again girlfriend Laureline (Cara Delevingne), is brought in to uncover a conspiracy plot surrounding a closed off area of the city that holds some unsavory secrets about the people in charge.

Where Valerian succeeds, obviously, is in its visuals. There’s more sheer invention in a single frame of this movie than in the last three Marvel outings combined (save for Guardians 2, which itself seems to have taken a page from the Besson handbook on madcap visual lunacy). The film starts with an extended sequence in an inter-dimensional shopping mall that’s just as weird, funny, and mind-blowingly awesome as you can imagine. And that’s just the beginning of the movie. My entire investment in the film was based around waiting to see what kind of bizarre visual gag the filmmakers would come up with next. And on that front, and I was anything but disappointed.

But the most unique thing about Valerian isn’t the action, but the thematic force driving the action. Besson’s film is about diplomacy, and all the messiness, complications, and beauty that comes with cross-cultural communication. It should be fitting that the film itself is messy, complicated, and frequently beautiful. Besson speaks in a visual language all his own, and watching Valerian feels like discovering a rare foreign sub genre of music, or reading a French comic book for the first time. The experience is novel, uncomfortable, and unforgettable.

Unfortunately for less forgiving audiences, however, it’s also a little problematic. Truly liking this film means having to overlook the egregious mis-casting of DeHaan in the star role. That’s not to say that he’s a bad actor, but his talents and on screen presence are so tailor made for weird-o, social outcasts (see Chronicle, Life After Beth) or anti-social millionaires (see The Amazing Spider-Man 2, A Cure for Wellness), that watching him try and sell Valerian as a suave, macho ladies man feels like watching your creepy 16-year-old cousin try and pick up girls with lines he learned on Family Guy. It doesn’t help too that Besson’s weak and frequently over-expository dialogue, particularly in the last third of the film, doesn’t feel natural coming out of anyone’s mouth, much less DeHaan’s. The strongest member of the cast is easily Delevinge, who effortlessly sells Laureline’s “I’m clearly smarter than all of you” attitude without coming across as pretentious or insufferable.

It should be said that these issues would damn an otherwise mediocre movie, but in Valerian, they feel more like caveats. This is still a thoroughly entertaining and visually groundbreaking film, destined for the cult circuit and ultimate critical re-evaluation. Even if it’s not as good as it could have been, it’s still way ahead of pretty much everything else like it, and definitely worth a look for the curious movie-goer.

OVERALL RATING: 7.5 / 10

SEE IT OR SKIP IT: See it.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wonder Woman (movie review)

My sister is a huge Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle fan (trust me, I’m going somewhere with this). She’s got t-shirts, posters, pajamas, a definitive ranking of who the best Turtle is, etc.

So anyway, a couple of weeks ago, we were having a conversation about what our favorite super hero movies were, and it occurred to me about half way through that she hadn’t brought up TMNT once. When I pointed this out, she gave me a weird look.

“The turtles aren’t superheros,” she said with a curious lack of confidence. When I proceeded to point out to her that the Turtles did more actual “saving” that either Batman or Superman in either of their last movies, she quickly added Michelangelo to her list.

But it got me thinking: in a time when “superhero” movies have joined the Western as one of the most popular genres in the global market, have we lost sight of what the word “superhero” really means? Have we entangled ourselves so hopelessly in the throngs of geek culture that we can’t even properly define the word we assign to some of the highest grossing and most beloved movies of all time?

And that’s when I remembered Wonder Woman, a movie which came out a few months ago. A movie which I saw, twice, and have been struggling to write a review of ever since. Partially because my summer has turned out to be a lot more hectic than I anticipated, and partially because I really wasn’t sure what to say about it.

It was great, of course, but anyone could tell you that. Besides, plenty of other movies that are just like Wonder Woman are also great. The first two Rami Spider-Man movies were great. The first Avengers was great. The second Nolan Batman movie was great.

But Wonder Woman was something else, and it wasn’t until I had that discussion with my sister that I realized what that “something” was.

If you haven’t seen it by now, shame on you. Kidding, but seriously, it’s a phenomenal film, popcorn or otherwise. Gal Gadot plays the titular super heroine, who embarks on a journey to save mankind from the clutches of the evil war-god Aries when smarmy WWI pilot Steve Trevor (the ever charming Chris Pine) crash lands on her isolated island of Themyscira. Together with Trevor and his rag-tag band of smugglers, spies, and soldiers, Diana travels to mainland Europe where she must come to terms with her own identity and powers if she is to defeat Aries and save the world, the key word there being “save.”

See, for all the focus pop culture has given super heroes over the last decade or so, very little has been given to what super heroes actually do, and when said focus is given, it is frequently in context of the super heroes themselves. By this, I mean that in most super hero movies (particularly Marvel ones), the only saving a super hero does is in issues directly related to his or her self. The Suicide Squad would not have been deployed had Enchantress, a member of the Suicide Squad, not defected and gone bat-shit crazy. That quaint small New Mexico town in the first Thor movie would have not gotten destroyed had Thor himself not gotten his arrogant ass banished from Asgard in the first place.

The list goes on, but the point remains the same: in an effort to deconstruct and complicate the super hero archetype, Hollywood has taken all of the *ahem* wonder out of what it actually is super heroes were made to do. This is why Marvel has a “villain problem.” The antagonist is almost always there so that the protagonist can grow and develop as a character. In fact, the whole world seems to exist for the express purpose of serving the superhero’s growth and needs. The question I keep finding myself asking during most of these movies is: who’s doing the saving?

And this is what makes Wonder Woman so special. By the end of act one, Diana has made the conscious and intentional decision to leave the safety of her homeland and save the world. She has taken responsibility for a problem that she has spotted, and realized that she can do something about. Even if she weren’t able to deflect bullets with her arms, or jump twenty feet in the air, she would still be a super hero because she wants to save the world.

There’s a simplicity and innocence in that central statement that makes Wonder Woman the movie just as—if not more—inspiring than Wonder Woman the character. This is, after all, the first major tentpole superhero film to be lead by a woman (and by major, I mean MAJOR. Sorry Elektra). It was going to cary with it an immense power and responsibility absent from, say Thor: Ragnarok, no matter who was in charge or what the story ended up being. But that director Patty Jenkins and writer Allen Heinberg decided to make power and responsibility the driving thematic forces of the film itself is worthy of all kinds of praise. This is a film that recognizes its place in the pop culture, and uses its wide canvas to make a touching and beautiful case for gender equality and social responsibility. It, like Wonder Woman herself, wants to save the world.

And damn it doesn’t come close. The production is crisp, well mounted, and impeccably performed. Chris Pine and Gal Gadot have disarming chemistry, the supporting players are all fleshed out and interesting. The design is incredible, the action is astounding. But most importantly, it makes us believe in superheros again. It makes us marvel at a character’s central humanity, their desire to do good above all else. It overwhelms us with sweeping spectacle, joy, and wonder.

If Wonder Woman doesn’t end up being one of the best movies of 2017, it is most certainly one of my favorites. Long may she reign.

OVERALL RATING: 9.5 / 10

SEE IT OR SKIP IT: See it.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dark Tower (movie review)

For a film which is kind of a western, kind of a sci-fi action flick, kind of a fantasy and kind of a horror film, I’m kind of disappointed how little there is to say about The Dark Tower. I’ve never read the books, so I can’t talk about what it does or doesn’t do right regarding the source material. There’s nothing egregiously awful for me to poke fun at, nor is there anything that stands out enough to warrant some larger discussion about the film’s place in the popular culture, or at the very least warrant a recommendation. The Dark Tower is just… fine. It’s okay. It’s a solid B-. Maybe a C+.

The titular “tower” is, in the context of the story, a giant structure which stands at the nexus of several different universes, protecting them from the evil forces that lurk outside. A sadistic wizard named Walter Padick (Matthew McConaughey) seeks to destroy the tower by harnessing the minds of children possessing a special power known as “the shine” (you know, in case you forgot that this was a Stephen King adaptation). Next up on his list is Jake Chambers (Tom Taylor), a young boy living in New York city, and grieving the recent loss of his father. When Jake learns of his destiny and opens a portal to “Mid-World,” one of the tower’s many universes, he joins up with Roland Deschain (Idris Elba) the last in a line of Eastwood-eque “Gunslingers” tasked with protecting the tower, and the two set off to destroy Walter and save the universe.

The film ambles along at an amicable pace. Nothing feels too rushed, things aren’t lingered on for longer than they need, and Jake checks off the empty boxes in his “hero’s journey” Scantron like he’s been studying for this test since he was five. What the film makes no attempt to do, however, is offer any compelling reason why we should care for this universe that he and Roland are trying to save. Mid-World is a desolate landscape, empty and mostly unpopulated, and the fascinating, cross-over universe that seems to exist on the edge of frame remains unseen, unexplained, and as a result, uninteresting. For example, there’s an extended sequence at an abandoned theme park that promises some kind of interesting world building gag, and instead goes absolutely nowhere. When Jake and Roland eventually do come across Mid-World’s population, it’s a boring Western town with no distinguishing characters or characteristics.

This kind of apathy never “hurts” the film per-sea, but it makes it very difficult to leave an impression. Even the Gunslingers, with their cool code of ethics and sharp pistol skills, are relegated to forlorn discussions about how “great” they were back before Walter and his army took over, and a pathetic flash-back cut scene near the beginning of the movie. Roland finally does spring into action for the giant third-act shoot out, and while it’s certainly worth the wait, I couldn’t help but feel that it would have been more satisfying had we a bigger stake in his development as both a character, AND as a Gunslinger.

Look, I get it; the more and more content there is, the less and less room there is for fat. With hours and hours worth of things to watch, universes to explore, and franchises to build, the necessity to strip stories down to their essential components seems very real, and trust me when I say that Dark Tower is a lean piece of meat. But if you’re going to do minimalism, do it right. The cantina scene in the original Star Wars is a good example. You don’t have to go into excruciating detail about every alien spices in the Star Wars universe to make it feel like an actual universe. All you need is to make it feel real, make it feel like there’s something going on behind the scenes.

That takes a lot of talent, as a filmmaker, a storyteller, and a technician. But while director Nikolaj Arcel is no George Lucas, he’s a far cry from Josh Trank. His action scenes are thrilling, and the little bit of actual character that he does slip into the proceedings, including an extended sequence where Roland wanders confused around New York city, shows hints to a bright future as a blockbuster director. I’m interested to see what he does next, even if I’m not necessarily interested in another Dark Tower movie. I’m also interested to see what the film means for Idris Elba, who’s awesome as Roland, and makes me wonder why a bigger franchise hasn’t snatched him up yet. He succeeds where the script fails, in giving his character—and the world around him—an appropriate amount of charm and grit. Unlike McConaughey (who can’t seem to decide if he’s still in one of those Lincoln commercials or not), his performance is effortless, and his on-screen chemistry with Taylor is potent.

The Dark Tower should satisfy your sci-fi action movie cravings until the next Marvel movie comes out, but that’s about all it will do. Two months, and everyone will have forgotten this movie existed (that is, unless Elba does end up being cast as the next James Bond or something equally high profile, in which case it will go down in history as the first time we started to take him seriously as a bankable Hollywood star). Either way, your tolerance for standard, cookie-cutter popcorn flicks will be the deciding factor in whether to go out and see it. Personally, I’d rather stay here on Keystone Earth.

OVERALL RATING: 6.5 / 10

SEE IT OR SKIP IT: Skip it.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Okja (movie review)

There’s no reason Okja should work as well as it does. As a matter of fact, there’s no reason this movie should work at all. This is a film that starts out as a farce, becomes a fantasy adventure, doubles back around to farce, and ends as a savage takedown of capitalism. Narratively, it feels like something dreamed up on a Tumblr thread by a dozen animal rights activists. It feels like someone took the premise for a Hayao Miyazaki children’s film and played it like Terry Gilliam tripping on acid. It’s E.T. meets Food Inc. with a hefty dash of The Hudsucker Proxy. It’s is hot mess of styles, genres and characters that should have, by all accounts, been an absolute catastrophe.

Instead, it might be the best movie of the year.

How? Hell if I know. Watching this thing play out is akin to watching one of those “How It’s Made” videos. You know, the ones where you sit in astonishment as a flurry of machines screw caps onto toothpaste bottles like it’s some kind of synchronized ballet. Okja is a wild machine in and of itself, starting with what amounts to a fairly simple premise and then taking it to the most visually and narratively complicated places possible while still managing to land on its feet. If I were to have one complaint, it would be that in the process of completely and utterly blowing your mind, the film looses some of its blunt emotional impact. And by “some” I mean “very very little.” This is one hell of a movie.

Our story follows a little Korean girl named Mija, who lives in the mountains with her grandfather and his enormous super-pig Okja, who is Mija’s best friend. As it turns out, Okja is the property of a Monsanto-type conglomerate, which genetically engineered Okja and several other super pigs just like her as a publicity stunt to promote a new line of super meat. The company comes to retrieve Okja, so Mija sets off on a quest to save her best friend. But when she accidentally gets involved with a group of animal rights activists with slightly different motives, Mija must learn to navigate a complicated new world if she is to get Okja back in one piece.

It is that “complicated new world” which immediately sets the movie apart from others like it. The big corporate machine isn’t presented as a board room of mustache-twirling men, but a diverse collective of fascinating (and sometimes sympathetic) characters with ulterior or conflicting motives. There’s Tilda Swinton as Lucy Mirando, the bright and optimistic leader of the Mirando corporation, who uses every opportunity to down-play the brutality going on behind the scenes so that she can better improve her personal image and re-invent her family legacy. There’s Jake Gyllenhaal as Johnny Wilcox, a beloved television personality and animal “lover” a-la Steve Irwin or Bear Grylis, who’s acting as the face of the Mirando corporation. And then there’s Giancarlo Esposito (Gus from Breaking Bad) who’s moved up from chickens to pigs. He spends most of the movie silently pulling the strings of the operation from the shadows, all the while working with Lucy’s evil twin sister Nancy (also played by Swinton) to take back the company.

That all of these characters are given the freedom to be interesting, compelling, and ultimately symbolic for specific aspects of capitalist society WITHOUT overshadowing the emotional core with Mija and Okja is the film’s real accomplishment. It reminded me of watching Spirited Away for the first time, in that while I was impressed by the genuinely clever ways both films deal with the social issues at hand, they never get in the way of the light innocence of their unlikely protagonists. And like Spirited Away, Okja works because we experience the world through Mija’s eyes. She isn’t the same naive little girl at the end of the movie, but her steely resilience hasn’t changed a bit.

And then there’s the activists. Lead by a predictably esoteric Paul Dano, the “Animal Liberation Front” not only provides and interesting wrinkle in Mija’s seemingly simple plan, but they also give the film a rich thematic weight. They’re not the “antagonists” per-sea, but whereas Mija just wants her best friend back, the ALF is more focused on bringing the entire corporation down. I’ll spoil nothing, but I will say that this adds to some genuinely powerful conflict between Mija and the activists, one which ultimately teaches her and shapes her just as much as her interactions with Lucy and the Mirando corporation. There’s tension coming from all sides in Okja, which makes for both a thrilling viewing experience and a profound catharsis once the credits have rolled.

So perhaps it isn’t such a mystery. Perhaps it is as easy as good, solid writing. But director Bong Joon-ho (the wild genius behind 2014’s Snowpiercer) always seems to know how to take the film beyond the boundaries of “good.” His images stick in the mind like burn marks, his world is a perfectly harmonized symphony of sound, light, and color. He makes the big scenes feel subtle, and the subtle scenes feel grand. Whereas other, less talented directors would have taken the film at face value, Bong is always interested in finding the truth underneath the words.

Okja is the closest a live action movie has ever come to capturing the sheer magic and brilliance of a Studio Ghibli production. It’s the most “George Miller” movie that George Miller had nothing to do with. And as far as Netflix original movies go, the streaming service is going to have a tough time topping this one. They have given us a marvelous sci-fi thriller that plays like a fantasy adventure and beats with the heart of a parable. What a miracle.

OVERALL RATING: 9 / 10

SEE IT OR SKIP IT: Definitely see it.

0 notes

Text

Spider-Man: Homecoming (movie review)

About a month back, Marvel/Sony/whoever was in charge of the marketing for the upcoming “Spider-Man” film (the sixth in almost fifteen years) released an official poster detailing all the characters in heroic positions Richard Amsel style. Yeah, you know the one I’m talking about.

The internet response was swift and brutal: just what the hell are we supposed to be looking at here?? We’ve got Spider-Man, sure, and I guess Iron Man shows up in the movie at one point. But why is he on their twice? Why is Michael Keaton on there twice? Did we need Happy Hogan there? Did you even remember Happy Hogan existed?

Far be it from me to judge a movie based on its poster, but as it turns out, Spider-Man: Homecoming suffers from the exact same problem. In an attempt to re-invent the iconic superhero for a new generation (and for a third time, thanks to Mark Webb) by means of a smaller, lower-steaks, teen angst dramady set on the fringes of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, producers Kevin Feige and Amy Pascal have delivered… basically just another Marvel Cinematic Universe movie. It’s bloated, it’s over long, it’s got so many cheep callbacks to the greater universe and god-knows-what comic book bullshit that it threatens to smother the charming, unique twist on the beloved character that stands firmly at the film’s center.

But Homecoming has two great things going for it: the cast and director Jon Watts. Fortunately, these are enough to keep the damn thing afloat (if only that), but it’s still disappointing to see the movie this was meant to be try and weasel itself out from under the VFX hodgepodge that lands on-top of it like a crumbled, brick wall.

The aforementioned twist on the Spider-Man mythology isn’t so much a twist as it is a literal interpretation of the phrase “your friendly neighborhood Spider-Man.” Here, Peter Parker (played by Tom Holland) is a sixteen year old kid at a public high school who’s post-school bell Spider-Man activities primarily consist of helping old ladies onto the bus and catching petty car thieves in his small neighborhood in queens. Mostly, however, he likes to hang out with his friends on the academic decathlon team, build LEGO sets with his best friend Ned (a star-making performance by Jacob Batalon), and harass Happy Hogan and Tony Stark about when they’ll let him join the Avengers. There’s no overarching conspiracy involving his past, no giant mutant lizard who wants to turn the whole city into giant mutant lizards. The stakes are low, the characters are real, and for maybe the first time in his fifteen years on screen, “Spider-Man” the character feels like the kind of kid who would read “Spider-Man” the comics.

There’s something really admirable about that. Director Jon Watts has a John Huges-level talent for sincerity, particularly when it comes to the high school bits. It’s telling when the less actual “danger” our hero is in, the more dangerous the situation feels. For example, there’s an extended sequence in the middle of the film where Peter is trying to bust an alien-superweapon-dealing crime ring the night before his decathlon competition. Things go wrong, of course, and suddenly Peter must make it back in time or face social and academic destruction.

But this is an interesting point in the story to talk about what Spider-Man: Homecoming does wrong. You see, the ticking clock doesn’t actually end up being the decathlon. Peter misses it, and aside from a detention slip, nothing ever comes of this. It’s as if the film sets up a plant for a completely different payoff. The different payoff ends up being one of the alien weapons that Ned has stashed in his backpack. It deteriorates, causing havoc during a field trip to the Washington Monument, and Spider-Man must swoop in to save his friends before it’s too late.

I guess this constitutes SPOILERS, but it’s tough to talk about where Spider-Man fails without getting into how it fails. Instead of the actions set pieces feeling like the progression of the plot, most of them feel like diversions. The Washington Monument sequence doesn’t have any real effect on any of the characters, and it shatters the smaller, more personal consequences the film spent so much time setting up before hand.

The same can be said of the villains. I have to preface this by saying that casting Michael Keaton as The Vulture was a great decision (considering he’s played two Birdmen before). He brings an authenticity and genuine frustration to his roll, and the script deals him an even hand, all while giving him the appropriate amount of menace. He’s interesting, he’s scary, he’s empathetic, and he ends up having a very surprising and very personal attachment to Peter that I’ll refrain from spoiling here.

The problem is that even though he and his team of scrappy super weapons dealers are interesting in their own right, Spider-Man’s conflict with them feels oddly forced. On paper, Peter isn’t seeking justice so much as using them as a way to prove himself to Stark and Happy. While this is a convincing enough reason to have him duke it out with The Vulture once or twice, it’s not enough to drive all of the action in the film. He isn’t “saving” anybody by fighting them, not directly at least. As a matter of fact, as Spider-Man, Peter ends up causing more trouble than he fixes, and the movie is never really sure what to do with this idea.

Save for one set piece involving the Staten Island Ferry, most of the action in the film left me bored and wishing we could cut back to the high school. Perhaps that might have been the point; that Peter himself is wildly out of his league in the world of alien blasters and avian supervillians, but that’s not an excuse to have boring action. This is an action movie after all, and when the set pieces leave you cold, that’s not a good sign.

There’s more than enough of Spider-Man; Homecoming to warrant recommendation. Just spending ten minutes with Peter and Ned is worth the price of admission. Watts knows his audience better than his audience probably knows themselves, and if Marvel left him to his own devices, Homecoming would have easily been the best MCU movie since The Winter Soldier. But it’s about twenty minutes too long, and those twenty minutes are defeating in their blandness and irrelevancy. Like Peter himself, the film is charming, ambitious, and little too big for its britches (or super suit).

OVERALL RATING: 7 / 10

SEE IT OR SKIP IT: See it, but level your expectations.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Beguiled (movie review)

In Sofia Coppola’s The Beguiled, Nicole Kidman plays the head of an all girls school in the deep south during the American Civil War. Her best attempts to shield her students from the dangers of the outside world are thwarted one day when one of the girls brings home a wounded union soldier. Played by Colin Farrell, Corporal John McBurney turns out to be an odd yet ultimately welcome addition to the all-female family…

That is, until he isn’t.

I’ve always found Sofia Coppola to be a fascinating director. Being the daughter of one of the most popular and acclaimed filmmakers of all time hasn’t just given her the resources and freedom to make more experimental films for a broader market, it’s also given her a unique—if frequently problematic—cinematic perspective. I don’t know what it’s like to grow up as Hollywood royalty, but watching Coppola’s films, who’s subjects have included everyone from big name actors (Lost in Translation, Somewhere) to actual royalty (Marie Antoinette), I feel like I have some idea of what it must be like. Coppola is drawn to isolated characters, whether it be Bill Murray isolated in the dark hotel rooms of downtown Tokyo, or Kirstin Dunst lounging around the bright, cavernous halls of Versailles.

The Beguiled is no exception. Author Thomas P. Cullinan’s book (and its previous adaptation, more on that later) acts as the perfect vessel for her isolationist point of view. Cinematically, Beguiled is haunting and empty, both detached and suffocating in its intimacy. Coppola fills the sound-scape with bombs and cannons echoing in the distance, emphasizing how removed these women are from the war raging around them. She stages her shots as if the camera is an outsider watching from the dark corner of a room, like we’re watching the characters without their permission. Evidence of her own outsider/insider upbringing is all over The Beguiled, and more than often works to better the film thematically. Isolation is itself a big theme of the story, as the women must all individually decide whether McBurney’s presence is worth the trouble it causes them, both physically and emotionally.

This has its advantages, and its drawbacks. For one, I found it refreshing to see this kind of story told from a female perspective. By “this kind of story,” I do mean that if Beguiled would have fallen into different hands (perhaps male ones), the women would have been portrayed as the predators as opposed to the man, which I suspect is the case with the original 1971 version. I’ve never seen it, so I don’t know for sure, but I was intrigued by the ways Coppola sidestepped possible interpretations of specific characters and/or plot points that could have painted the women in a negative light. For example, Kidman’s character is clearly attracted to the Corporal, but the movie never explicitly connects this to her decision making. As played by Kidman, she is a calm, composed, and clever creation, and her attractions are seen less as a flaw and more as a logical reaction to having a hot naked soldier in your house.

The drawbacks, however, are more nuanced. Like I said, I’ve never seen the original, but I do happen to know that Coppola intentionally decided to omit an African American slave character in her remake. She did an interview on the subject (which you can read here) in which she essentially said that placing a slave in woman’s midst would complicate the positive light in which she makes them stand. The film, like the school at the center of the story, is isolated. But instead of being isolated from the war (and humanity by extension) Coppola isolates her version from the realities of slavery. Her vision of the American south is completely divorced from the truth that has come to define its very existence, and by intentionally refusing to engage with this truth, the negative aspects of Coppola’s “perspective” come to light.

I always get a weird feeling when I bring politics into a review, but like I said back when talking about Ghost in the Shell back in March, some movies are intimately connected with the politics they do, or in the case of The Beguiled, do not discuss. This is a movie that so desperately wants to be taken on its own merits, to “isolate” itself from the hard discussions and realities that come with slavery, that it ultimately ends up feeling more than a little tone deaf. If Coppola wants to avoid these criticisms in the future, she needs to challenge her own worldview. She needs to hear the voices of those of less privilege than her, and step out of the dark corner where she frequently sets up her shots. Either that, or perhaps don’t make a movie about a southern girls school. Because this is 2017, and whether we like it or not, that kind of story comes with a lot of baggage.

I know I sound very negative here. Don’t get me wrong; I really, really enjoyed The Beguiled. It’s astonishingly well made; gorgeously shot, gorgeously costumed and designed. Coppola has crafted a palace of cinematic perfection, but if we don’t recognize its flaws and engage with historical miscalculations that cloud its conception, we might end up—like the girls in the film—trapped inside. Unable to connect, unable to escape.

OVERALL RATING: 7.5 / 10

SEE IT OR SKIP IT: See it, talk about it, and don’t be quiet about it.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Baby Driver (movie review)

The worst thing about Edgar Wright’s Baby Driver is how novel it feels; movies this fun, sharp, and well executed shouldn’t be the exception, they should be the rule. This is summer, for goodness sake. We should have been getting a Baby Driver every weekend for the last two months, and instead we had to wait until the beginning of July?

Ugh. Regardless, Baby is an oasis in what’s looking to be another depressingly dry movie season, and I sincerely hope it does well enough to raise the bar for quality action films.

On a narrative level, it’s really not that much to write home about. Which is fine; better movies have gotten by on dumber premises. Here, our hero is “Baby” (played by Ansel Elgort). He’s a sweet young man suffering from tinnitus, an ear condition which requires him to be listening to music all the time, but also seems to give him superhuman abilities behind the wheel of a car. When he’s not at home making music of his own, he’s off playing get-away driver for a notorious Atlanta mobster (Kevin Spacey) and his band of degenerate killers, burglars, and outright psychopaths. It’s a world that Baby doesn’t belong to, and when he falls for a sweet waitress at a local dinner (Lily James), he decides to plan his last big getaway.

So yeah, this is your standard criminal-with-a-heart-of-gold-tries-to-escape-the-business flick with a tangy musical twist. Baby’s condition gives Wright an excuse to set his out of this world car stunts to some of his favorite tracks, and as far as conceits for action movies go, that ain’t half bad. What it also does, perhaps inadvertently, is give the whole movie an electrifying pace. Watching it is akin to listening to a really good album; the set pieces feel appropriately timed and matched with one another, much like songs on a playlist. The closest point of reference would be Tarantino, who structures his films in a similar way (there’s a great Nerdwriter video on this if you want to know what I’m talking about).

But unlike Tarantino, Wright doesn’t waste any time pontificating on any of the film’s themes. He lets them grow organically, coming out of the character’s actions rather than what they say to each other. For example, Baby feels out of place with the criminals because he’s constantly trying to keep people safe, which is a source of comedy in some of the action scenes, and a source of drama in others. Whenever the film does slow down, it’s only to build tension, and Wright excels at keeping us at the edge of our seats. Inside and outside the car.

In this way, Baby Driver feels like a departure from his earlier work. Wright made a name for himself making comedy action flicks in which the “comedy” was very much tied to the “action.” One of the best jokes in Scott Pilgrim was that people turned to video game coins whenever they died. One of the funniest set pieces in Hot Fuzz is a group of cops opening fire on a town of homicidal elderly people. In Baby Driver, however, violence is the opposite of fun. We like Baby because he’s non violent, and when he ultimately needs to resort to violence in the latter half of the film, the consequences are grave and immediate.

I’m very excited to see what he does next. Edgar Wright, I mean (though I wouldn’t be opposed to seeing Baby on screen again). Baby Driver is “light” entertainment, in that it’s not going to change your life or shift your worldview. It’s not even Wright’s best movie if you ask me, but that doesn’t mean it’s not a hell of a good time, and a step in the Wright direction (hehe) for one of my favorite directors. This is the summer movie you’ve all been waiting for. Sit back, fasten your seatbelt, and hold on tight.

OVERALL RATING: 8 / 10

SEE IT OR SKIP IT: See it.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Their Finest (movie review)

Between Their Finest and The Zookeeper’s Wife, 2017 has been a solid year for feminist WWII movies. There’s something oddly poetic about that, considering the fact that a woman lost to a Nazi poster boy in the last major US election. But that’s a discussion for a different day. Today, I’m going to tell you why I almost really really liked Their Finest, but why you should probably go and see it anyway.

The story is set at the British Ministry of Information shortly after the evacuation of Dunkirk (which is also getting a movie this year). Our hero is Catrin Cole (Gemma Arterton) a feisty young writer who is living with her impoverished painter husband (Jack Huston) in Blitz-ridden London, when she is given a job as a screenwriter for an upcoming propaganda piece. She teams up with wise-cracking veteran screenwriter Tom Buckley (Sam Claflin, abrasively charming as ever) and aging film star Ambrose Hilliard (a fantastically scenery-chewing Bill Nighy), to bring to life the semi-true story of two sisters who stole their father’s fishing boat to help aid on the shores of Dunkirk.

So yeah, I know I mentioned this earlier, but I do feel I have to make some reference to the fact that within the same year we’re not just getting a big blockbuster Dunkirk movie, but also a movie about making a big blockbuster Dunkirk movie. Not that this isn’t a coincidence (which is is) or that is says anything about our own current state of affairs (which it doesn’t), but as a history buff, I am pleased to see so much attention going to a chapter of WWII history that often gets glossed over, particularly in American textbooks.

But whether you’re a history fan or not, Their Finest is a lesson well told, and an exciting peak behind the curtain for a facet of the film industry which seldom gets any attention, even in its own medium. The novelty factor of getting to see not just how movies were made back in the early 40’s, but how the culture around movies and the moviegoing experience was of vital importance to the war effort, is more than enough to keep this barge afloat. At least, it was for me, but I have to recognize that my being both a screenwriter AND a fan of history might have skewed my objective viewing of this film… whatever that means.

And yet, while I enjoyed Their Finest for its clever writing, its clear-eyed and honest depiction of the filmmaking process and what that meant for the culture at large, I can’t say that it left the best taste in my mouth. There’s nothing “wrong” with the movie per-sea, it’s all beautifully accomplished, which expert production design, cinematography and directing that elevates it out of standard BBC territory. But when the film starts to hone in on Cole and Buckley’s relationship in its latter half, it starts to loose steam. Quickly.

This isn’t to say Claflin and Arterton aren’t good actors in their own right, or that they don’t have killer on-screen chemistry. If anything, the fact that they work so well together only makes the film feel more like a romantic dramedy than it probably should have. Once the focus starts shifting towards them and away from the film-within-the-film, I started to loose interest. And when it’s finally reviled where their relationship is actually going via a contrived, Nicholas Sparks level plot twist at the end of act 2, I damn near checked out.

It’s hard to put my finger on why this bugged me so much. There’s an on running joke in the movie that the studio wants to give one of the sisters in the Dunkirk film a love interest, a “hero” who’ll take care of all the third act heroics while the girls look pretty in the background. Our writer characters balk at why something like this would be necessary, in the same way that I found myself balking at the romance the movie was trying to shove down my throat. It’s a strange bit of meta irony that never pays off, and while Cole ultimately gets her opportunity to write the two sisters as heroes (a payoff that I did find particularly compelling), it comes after a solid thirty minutes of sappy romance movie cliches that felt less like a progression of the story, and more like studio mandated re-writes.

Despite these issues, I implore you to check out Their Finest if you can. Who knows; you might find it more arresting than I did. But even if you don’t, there’s no denying the wit, charm, and artistry on display, both from the characters in the film, and the people behind the camera. Some of the best wars have been fought with cameras, and whenever Their Finest surrenders to this simple yet profound fact, it soars.

OVERALL RATING: 7 / 10

SEE IT OR SKIP IT: See it.

0 notes

Text

Star What? (opinion piece)

Multiple On and Off-Screen Skirmishes have Put the Fate of the Galaxy at Risk… or has it?

While you were off prepping for your kick ass 4th of July BBQ, the Star Wars cinematic universe just went to hell. Or at least, that was the resounding cry from many film journalists and devoted fans. It all started at the opening night of the Los Angeles Film Festival, where Colin Trevorrow’s new film, The Book of Henry was met with unintentional laughs and some of the most scathing reviews of any other movie this year. Normally, this wouldn’t be such a big deal. Angelina Jolie’s By the Sea met a similar fate as AFI Fest two years back, and that seems to have drifted to the back of everyone’s collective consciousness.

But Angelina Jolie isn’t directing the next Star Wars movie. Fans of the series were quick to take to Twitter to voice their opinions not just about the movie, but about its director’s next project…

Yikes.

All while this was going down, Kathleen Kennedy, current head of Lucasfilm, was bracing to fire the directors of one of her next movies, but not the ones you were expecting. On June 20th, it was announced that Phil Lord and Chris Miller were dismissed from the upcoming standalone Han Solo film. This was shocking for two reasons. First, the film was three weeks out from wrapping, so the vast majority of the movie had already been shot. It’s not only rare to fire a director this late in the process, but it also boards ill will for the film as it heads into post. But second reason, and probably of more importance to Star Wars fans, is that Lord and Miller are well documented geniuses. Or at least, the three or so movies they’ve made since coming on the scene have been genius. Why on Earth would you want to fire them? Why would you want to keep a hack like Trevorrow? WHAT IS GOING ON?

Needless to say, things went to shit. The internet blew up with theories, vicious debates and nervous jokes. For the first time since its announcement back in 2012, the new Star Wars universe is in jeopardy.

Or is it.

Before I get into my argument, it’s important to get a few things straight. One: yes, Book of Henry was bad. It’s a bad, boring movie with a promising premise, flashes of genius, and more than a few moments of tone def miscalculation. It’s the kind of bad movie Ridley Scott makes every couple of years, and the kind of bad movie everyone is going to forget about by the end of August. This isn’t some trash masterpiece or career-ending snafu, and if you think it is, then I strongly recommend going back and watching Gigli.

Second: there is some merit to the discussion surrounding Luscafilm’s decision to hire Trevorrow in the first place. By this I mean that the trend of hiring young, sometimes inexperienced directors to helm huge tentpole movies often tends to favor young inexperienced directors of the same gender and skin tone. Now before you bring out your pitchforks, keep in mind that even though Gareth Edward’s name might read “Directed by” on Rogue One, anyone close to the movie will tell you that it had at least three different “directors” throughout production, all of whom had some hand in what ultimately ended up on screen.

Translation: it really doesn’t matter who directs these things. I can’t blame anyone who wants to complain about Disney missing the opportunity to use Episode 9 as a spring board for another kind of director, perhaps a woman or a person of color, and instead going with a choice as obvious as Trevorrow, who’s privilege and status affords him a host of other opportunities that women and POC might not have.

HOWEVER, as I previously mentioned, Colin Trevorrow isn’t really directing Episode 9. Kathleen Kennedy is, as is Rian Johnson, as are a bunch of other talented people who had nothing to do with that shit movie that came out last week (that, let’s be honest, you probably didn’t even see). So if you’re at all worried about whether some untalented hack is doing to butcher your precious franchise, you can calm down. There is no universe in which Disney would ever release a Book of Henry level bad Star Wars movie under any circumstances, and if Trevorrow were really that much of a problem, they wouldn’t have hired him in the first place.

“But Jackson,” you whine, frantically searching other unfounded think pieces to support your point, “they just fired Lord and Miller, so who’s to say they won’t fire Trevorrow later on as well?”

Here’s what you need to understand about Hollywood. If I, Jackson Smith, were to show up as the director of an episode on a long-running TV show—like say, Supernatural or Arrow—and if I were to say “so this episode is going to be an improv-style slapstick comedy shot in a different aspect ratio with a soundtrack by Daft Punk,” my ass would be out of there in seconds. If I were to be hired as the director of the next Doctor Strange movie and say “so this movie is going to be a black and white musical where Stephen Strange travels back in time to fight Genghis Kahn,” I would be fired before I even touched a camera.

When a studio invests millions and millions of dollars into a franchise with a loyal and vocal fanbase, the last thing they want to do is take a risk. It’s what propels them to hire big name directors like Colin Trevorrow and Lord & Miller. Both parties have big hits under their belts, movies which people liked and loved.

But there’s a fundamental difference between them that’s got little to do with talent, and everything to do with collaboration. Over his last couple of movies, particularly Jurassic World, Trevorrow has showed himself to be a very collaborative filmmaker. He takes input, he listens to advice, and if Disney were to mandate three weeks of re-shoots with a different director (as they do on pretty much everything), he’s not the kind of guy that would put up a fight.

Lord & Miller, on the other hand, have made a career out of fighting the system. All of their movies, from the Jump Street series to The Lego Movie, have succeeded by poking fun at the ridiculousness of their own premise, and the people who’d choose to green light such a thing in the first place. While hiring them to do helm a movie about a wise-cracking space pirate might have seemed like a good concept, if there were ever a franchise that thrives on its complete lack of irony, it’s Star Wars.

Sure enough, the news rolled in, and apparently it’s been a fight since day one. The duo disagreed with both Kennedy and Lawrence Kasdan’s ideas for the project, and by all accounts were ill equipped to handle a movie of this caliber. It seems like it would have been messy to keep them on, but I can understand why Lucasfilm did for as long as possible. It’s easy to recognize genius in a filmmaker or filmmakers, but it can be impossible to collaborate with someone married to a specific vision, as geniuses tend to be.

Colin Trevorrow is no genius. Or maybe he is. I don’t know. But regardless of his level of talent, he’s someone who’s happy to collaborate, who’s open to studio notes, and most importantly, someone who doesn’t want to dismantle the Hollywood system from the inside out. Star Wars isn’t the place to do that, not for now at least, which is why I can’t say I’m that surprised that Kennedy decided to give Lord & Miller the boot. Sad, sure, but I can take comfort in knowing that Star Wars, and Disney by extension, is a well oiled machine capable of corse correcting and delivering movies that are at worst passable, and at best transcendent. Your emotions might not be fine, but Star Wars will be.

0 notes

Text

The Fate of the Furious (movie review)

When did we stop seeing Fast and Furious movies for the cars? I mean, we still do. I still do, but at some point over the last few years, the moviegoing public started to take an active interest in who was driving them. Might I remind you that back in the early 2000’s, Vin Diesel didn’t show up for two whole movies and nobody noticed. In fact, in 2006 they tried to reboot the franchise with a whole new cast, and nobody noticed.

Maybe it was after the tragic passing of Paul Walker, who’s presence added an extra level of richness and solidarity to 2015’s Furious 7. But if you as me, it was the post-credit scene in Fast Five, where it was reveal Michelle Rodriguez’s character, Letty, was still alive. It was the first time the franchise became a franchise, in so much that it played on our knowledge of past installments, and most importantly, our emotional investment in the characters.

The Fate of the Furious might be the first since the original to actually be about the characters. It’s not a heist movie, like Fast Five, nor a crazy sci-fi action movie, like Furious 7. Well, actually it is a crazy sci-fi action movie, but it’s a crazy sci-fi action movie who’s plot isn’t driven (hehe) by some technical macguffin, but rather by the characters and their various relationships and interpersonal conflicts. Think of it as the Civil War of the Fast franchise. The stakes are game changing, but they’re also intimate. That is, until they’re not.

As teased by the trailers, the plot kicks off when Diesel’s Dom Toretto betrays his surrogate family (and the US government) by teaming up with a mysterious hacker named Cipher (played by Charlize Theron). Devastated, Letty, Hobbs, and the rest of the gang are left with no choice by to team up with Deckard Shaw, who you might remember as the big baddie from Furious 7. As they start to catch up with Dom, they begin to discover the full extent of Cipher’s plan, and the reason Dom decided to betray them in the first place.

I’ll get more into that reason later, but it should be said that as it stands, Fate might be one of the stronger installments in the series, for no other reason than the addition of Theron. Not only is she one of the best actresses around (and one of the most beautiful. Not that that has anything to do with it, and if you don’t believe me, watch Monster), but she might be the first antagonist in these movies to pose an actual threat. Not that Deckard and his brother Owen weren’t threatening enough in their own right, but as the movie ends up teaching us, there really isn’t that much that separates them from Dom and his own crew. The one thing that has remained consistent throughout these films is the idea that these criminals have hearts of gold. They care about each other, and not only does that excuse a lot of their petty “criminal” action, it’s also a driving force of the action.

Cipher, on the other hand, is a frigid bitch. She has no sense of empathy, she has no concept of family, and she’s also ten times smarter than everyone else. In a sense, she’s the perfect foil, and the movie comes to life whenever it lets her off the leash.

What this does, however, is render the conflict between Dom and his crew almost irrelevant. It becomes known pretty soon that the only reason Dom has teamed up with Cipher is because she’s holding his ex-lover Elena Neves, and his illegitimate child, hostage. There’s the potential for some interesting inner conflict here, particularly with Letty, whom he believed was dead when he sleep with Neves (side note: boy these movies are way too complicated), but this never really comes to fruition, and Dom SPOILER ultimately ends up wrecking Cipher’s operation, saving his child, and joining back up with his team as if nothing ever happened.

Which is disappointing really, because if there were ever an opportunity to drive (sorry, I couldn’t resist) this franchise into deeper waters, this would have been it. How does Letty feel about having a kid that isn’t hers? Is there some residual resentment about Dom going rogue in the first place, particularly from Hobbs, who lands in jail halfway through the movie as a result of his best friend’s action? Fate sets up some high emotional steaks, but they’re just there to get your butts in the seats.

Thankfully, there’s more than enough to keep you sitting. The action scenes are incredible, and while director F. Gary Gray doesn’t stage them with quite the operatic glee as his predecessor James Wan, he knows how to cross the line into ridiculousness without loosing his audience’s interest. Jason Satham’s Deckard and Dwayne Johnson’s Hobbs have some great back and forth banter (though their relationship progresses a bit quicker than it should have), Kurt Russell is entertaining as always, and Helen Mirren makes an appearance as Own and Deckard’s crime boss mom a-la Animal Kingdom that ranks as one of my favorite cameos of the year.

The Fast and the Furious is one of the most successful movie making experiments of the last two decades, as evidenced by its massive box office returns as loyal fandom. There’s no denying that Fate has got plenty of Fast; what it could have used is a little more Fury.

OVERALL RATING: 7 / 10

SEE IT OR SKIP IT: See it.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transformers: The Last Knight (movie review)

Reviewing the fifth Transformers movie is like reviewing six different movies at once. Though one of the shortest in length, Michael Bay’s final outing in the TCU (Transformers Cinematic Universe, because we have to call it something), is by far the most dense. For better or for worse (though mostly for the latter), The Last Night is the first of the epic sci-fi films to actually feel like an epic, in that it covers more narrative ground than the last three seasons of Game of Thrones. There are at least four main characters, an entire franchise’s worth of world building, and a show-stopping climax that is so immeasurably huge, it makes the Chicago sequence in Dark of the Moon look like a game of Candyland played at a retirement home.

Normally, this is the point in the review where I start explaining the plot but honestly? I don’t know where to start. Long story short: Optimus Prime has left Earth following the events of 2015’s Age of Extinction and stumbles back onto his homeward of Cybertron. There, he is recruited by an ancient floating mermaid named Quintessa (finally, a woman Transformer!) to go back to Earth and find a legendary staff capable of transferring Earth’s magnetic force to Cybertron, effectively saving their planet and destroying ours. It’s not unlike the set up for Dark of the Moon, only Optimus, having lost most of his faith in humanity, is filling in for Leonard Nemoy.

Back on Earth, Cade Yeager (a name so ridiculous I feel like I had to comment on it at some point in this review) is living as an outlaw on an abandoned junk-yard, where he houses Bumblebee and other other Autobots awaiting Optimus’ return. Some crazy bullshit goes down (most of which would be impossible to describe here), leading Cade & Bumblebee to travel to England, where they meet up with Anthony Hobkins’ Sir Edmund Burton and British history professor Laura Haddock. As Burton explains, Transformers have been jiving with humans A LOT longer than all four other movies have made it out to be, enough to the point that there is a secret brotherhood of special humans called the “Witwiccan,” decedents of the great wizard Merlin who are capable of wielding the staff and saving the world. This lineage includes such people as Haddock herself, William Shakespeare, Galileo, Winston Churchill, and Shia Lebouff.

And while you’re trying to swallow the giant marshmallow that is that premise, Cade and Haddock go off to find the staff before Optimus and Quintessa show up and wipe out humanity.

I can’t decide which is more baffling: the fact that anyone—much less an entire room or writers—decided on a twist that mind-blowingly incoherent, or that anyone at Paramount allowed it to go up on screen in what’s looking to be their biggest release of the year. The entire second act of the movie feels like listening to your crazy second uncle rambling off 9/11 conspiracy theories at a hot 4th of July party, where all you want to do is jump in the pool.

But Bay is in the same boat as you. As much fun as he has having the great Anthony Hobkins spout off unintelligible bullshit for a solid fifty minutes, he never delivers it with a straight face, and as the film approaches it’s astonishing third act, it becomes clear that none of it particularly mattered to him in the first place. Few directors are as upfront about their personal tastes as Michael Bay, and even fewer in the Hollywood blockbuster machine. Even in his most tone-deff scenes (of which there are plenty here), his work is never boring and, at times, weirdly compelling. There’s something to be said about the gonzo absurdism with which he delivers the England sequences, a shameless abandon that I wish more directors had the courage to express. If Bay’s form of restraint is a complete lack-thereof, then The Last Knight is a highlight reel of his most outlandish cinematic fetishes. Everything is on display, the good and the bad, and there are no apologies.

At times, however, this works to the film’s benefit, particularly when dealing with the actual Transformers. It’s been a full decade now since this franchise began, so the fifth installment can’t help but be a little interesting. Wait, Megatron is making a deal with Col. Lennox? What’s that about? You mean Optimus is turning against humanity? What’s that going to mean for Bumblebee and all the other Autobots who’ve fought, died, and bleed for him over the last four movies?