Text

Interview with Stephanie Byrd: by Terri Jewell

(Originally published in Does Your Mama Know? An Anthology of Black Lesbian Coming Out Stories, ed. Lisa C. Moore, published by RedBone press 1997. Transcribed by @laciere (typos my own).)

[Stephanie Byrd is a Black lesbian feminist poet, writer, critic, community activist. Her works include two books of poetry; critical essays in Greenwood Press’ Bibliography of Contemporary Lesbian Literature (1993) and Lesbian Review of Books (1995); listing in Black Lesbians: An annotated Bibliography by J. R. Roberts (1981); mentioned in Ann Allen Shockley’s essay, “The Black Lesbian in American Literature: An Overview” (1979) and Black Women and the Sexual Mountain by Calvin Hernton (1988). Her poetry has appeared in The American Voice, Kenyon Review, Conditions and Sinister Wisdom. Her books have been reviewed by many publications.]

STEPHANIE BYRD: I was born in 1950 on July 10th in Richmond, Indiana. My family has lived in or around Richmond since the War of 1812, perhaps before then. Part of them came from Boston, Massachusetts, because the Northwest Territory was free territory and they did not wish to become enslaved again. Other members of my family escaped from slavery in the South and came to Indiana, where small Black settlements had sprung up. These are the people that I came from.

I was a Latin major at Ball State University from 1968-69 and was an anti-war activist from 1968-73. I met some civil rights activists during that period who were doing work in Cairo, Illinois. The Black community in Cairo was boycotting the white businesses because of their refusal to hire Blacks. The white community was responding by driving through the Black community at night and shooting through people’s windows, so after dark people would turn out the lights and sit on the floor. I met a man who was doing some fund-raising at Indiana University in Bloomington and became involved with gathering canned goods and clothing to offset “The Wolf” in Cairo until the problem could be resolved.

TERRI JEWELL: Were you a lesbian then?

BYRD: Yes. When I was about 6 or 7, one of the neighbors called me a lesbian. I went to my grandmother and asked her about it and she told me that being a lesbian was about loving women, women loving women.

JEWELL: Your grandmother told you that?!!

Byrd: Yes. My grandmother Byrd. And that it was all right to be a lesbian if I really loved someone. And since I was in love with my little next door neighbor, I went out and told everyone that we were lesbians. My mother was furious and I think that was the first time I heard about lesbians. The second time, I was 12 and I was asked to put down on a sheet of paper what my goals in life were. I was in seventh grade at Hibbard Elementary/Junior High School. I had put down that my goals were to be a brain surgeon, a lawyer, and a lesbian. I was sent to the office. I realized when I was sent down to the office that something was terribly wrong even though I was only 12, and they said, “Well, do you know what a lesbian?” And I said, “It’s a person who lives on the isle of lesbos,” because I had looked it up in the dictionary. They me go, feeling secure that i really didn’t know what I was talking about. It’s funny that about a year later I was sent to the office again for being a Communist.

JEWELL: A Communist?

BYRD: Yes, because I asked for the Communist Manifesto at the school library so we could compare it to the Declaration of Independence.

When I was about 17, I realized that there was something wrong with being a lesbian socially.I tried to become straight and hooked up with this guy who turned out to be gay. By the time I was 19, I realized that none of this was working, so I just went back to being a lesbian again. It was very hard, though, because at 19 you’re kind of a sexual libertine. You’re not straight, you’re not gay. You’re just in heat. Being a lesbian was just the best and easiest way for me to be.

JEWELL: When did you start writing?

BYRD: When I was 17, in the summer. I had actually started writing before then during that school year and had written some short stories and some poetry. When I graduated from high school, I started writing poetry seriously and actually had a contest with my little gay boyfriend. We would write a book of poetry a month and that summer I produced three books of poetry, all of which I burned.

JEWELL: Why?

BYRD: I have destroyed my work in the past. I’d say, all together, four books of poetry. I have a tendency to lose control of my temper and as a result, my reason. I would burn my work as a cleansing act. A ritual.

JEWELL: You don’t consider the act of writing a cleansing? A ritual?

BYRD: Writing can be cleansing, but there have been times in my life when even the writing is not enough to cleanse.

JEWELL: So, writing is not always enough to cleanse what?

BYRD: Oh, I call them “the Terrors.” They are anxieties and fears that somehow combine into a feeling so large they seem to consume me from the inside out. I think some actress in a Neil Simon play once called the “Read Meanies.”

JEWELL: What has survived of your writing?

BYRD: There is a book of poetry called 25 Years of Malcontent which is now out of print. When I finished 25 Years of Malcontent, it was the result of serious years of serious writing, the last three of which I wrote every day for at least two hours a day, sometimes eight, depending on whether or not I was employed. I t was released in 1976 and published by Good Gay Poets in Boston. As with most first works by a writer, it’s somewhat autobiographical, describing things and events that I observed or was involved in. There is one poem there about a man who died in a house. He wasn’t found until much later and his cats had tried to chew through the door to get to him to eat him because they hadn’t been fed. And there is a poem about a white suffragette I had met in Texas. She was a wonderful, wonderful woman well into her 60s. This was in 1972. She told me to be true to my roots. The advice that she gave me was very good advice. The whole time I was in Boston, I don’t think I ever really convinced myself that I was anything but a Black woman from Indiana.

JEWELL: When did you first go to Boston?

BYRD: It was 1973.

JEWELL: Were you aware of the Combahee River Collective?

BYRD: In 1974, the women who eventually evolved into the Combahee River Collective were the National Black Feminist Organization of which I was a member. We used to meet as a support group at the Women’s Center in Cambridge. We would talk about a number of things. Barbara Smith was there and she developed guidelines on how we were to support each other. It was very like consciousness-raising. I remember the group being an open group and a lot of women coming who were straight and battered. They were Black women. Some of them were successful, some of them were very poor, some of them were working-class women. There were incidents where outsiders would come and discover that there were Black lesbians there and they would flip out with a great deal of hysteria and arguing and name-calling. And those were the early meetings. But the thing i remember is these women coming who had been so battered in their lives that there was something disturbing about them and a support group wasn’t going to do it for them. I heard someone say recently that one of the best cures for mental illness for Black people is Black culture and I wanted the group to be more committed to the creation and preservation of Black women’s culture. But that was really difficult to do with the Combahee River Collective because the group soon was not all Black. And the support group was very committed to combating racism and sexism and antisemitism and class oppression, so many minority women had to be included. At that time, I had a great deal of difficulty synthesizing the presence and the issues of the minority women who were not Black into the issues that involved me. I was something of a Black separatist, I suppose.

JEWELL: In reading their statement, the group was against separatism and wanted to work with Black men.

BYRD: Well, I never heard them say anything about working with any men when I was in the group. They talked about working with white women. [In attempting to address] all the other concerns [of Koreans, Hispanics, Jews, Chinese, Vietnamese, etc.] just turned into a wave that seemed to obliterate what I was hoping would become a Black feminist support group. And as Black feminists, in retrospect, I realize now that I was hoping that we could do something to address the needs of some of these women who were coming to us who had been stabbed or shot or beaten and threatened and didn’t know how to leave their husbands or didn’t know how to address life without a man. These women needed a separatist environment in which to heal. Maybe later on, this whole multi-ethnic feminist vanguard could include them, but for then and for now, too, it doesn’t. It does not address the needs of these Black women.

JEWELL: I agree. So, why do you think that is, even though we are well-versed in the problems that we have? And I’m not living on either the East or the West coasts, but in the Midwest. You know the gaps HERE. In your opinion, why are we Black women so afraid of having our own groups and projects exclusively? We always talk about how nice it is to be among ourselves with our own language and our own ways of doing and seeing things but we just don’t do it. Even the Combahee River Statement says, “We realize that the only people who care enough about us to work consistently for our liberation are us.” Yet, we are constantly getting away from that.

BYRD: Oh, it’s much easier to address everyone else’s needs rather than your own. You know that from dealing with your own problems. It is much easier to go out and find someone else who has a bigger problem or a different problem and work on their problem for them than to deal with your own mess. And essentially, that’s what we have been doing all along historically. We think we CAN’T do it by ourselves. And the reason why we can’t do it by ourselves is because “they” will annihilate us. We have to get away from this paranoia.

JEWELL: How long were you with this group?

BYRD: Oh, until about 1976.

JEWELL: So, it did not start out being a Black lesbian group?

BYRD: Oh, no, no, no.

JEWELL: Or did it start out being a Black lesbian group but no one was saying this so just more women would want to be involved without stigma?

BYRD: When the group started, there were only three of us, including myself, who said they were lesbians. Only three of us announced that we were lesbians during the first night of the group. The other women introduced themselves by talking about where they went to graduate school and what their interests were, etc., but no one else said they were lesbians. After several months, though, some of the other women came out.

JEWELL: What made you leave the group?

BYRD: I Was heavily into my poetry, doing a lot of writing and readings. And I wanted to do more cultural things. I read all over Boston: University of Massachusetts, Boston; Faneuil Hall, which is the Town Hall in Boston. In 1976 I decided I couldn’t maintain the separatist pose any longer, that I would have to become involved in the Gay and Lesbian Rights Movement.

JEWELL: Why couldn’t you maintain a separatist stance?

BYRD: Actually, I found that despite what the Combahee River Collective said about separatism, they were very anti-male. Most of the women I knew there did not like men and made no pretense of acting like they liked me or wanted to do anything to help men. I had met a lot of Black gay men who had been decent to me and had been brotherly. I felt the least I could do was return in kind. So I became more involved in the Gay and Lesbian Rights Movement but always, ALWAYS my focus was on US as Black people. Not just as Black women but as Black people. And in writing my poetry, because I am a Black woman, I was creating Black women’s culture. And those things were becoming clearer and clearer to me as i grew older. And I didn’t need a large support group to give me an identity. My identity was growing out of MY growing as a Black woman artist and creating Black women’s art. And as a Black person who has a Black father and Black male cousins and Black uncles and a Black grandfather, I had a duty to protect their rights as Black people. The only way I could do that, because I couldn’t do it within the homophobic Black community, was to do it with the Gay and Lesbian Rights Movement.

JEWELL: You were on television and the radio?

BYRD: In 1977, I was a guest on a Black cultural TV program called Mzizi Roots. This was an Emmy award-winning program in Boston. I appeared on the segment called “Gay Rights–Whose Rights?” and the host was Sarah Ann shaw. The other two guests were a Black psychologist and a Black gay male activist.We discussed the presence of Black lesbians and gays in the Black community and the legitimacy of claims made by gay and lesbian activist groups for human rights. I also did radio programs. I did one called Coming Out and that was in 1974. I was asked a whole bunch of questions about Black lesbianism. This was on PBS. Then I did another radio program, Out of the Closet, in 1978. By then, I was reading poetry on the air. I had a small group starting with two women and ending up as a five-piece band, called Hermanas. They used to accompany my poetry with music. They were with me until 1982. Then, in 1984 I did a whole one-hour show on MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology] radio called Musically Speaking, which was nothing but poetry and music. I also read for Rock Against Sexism, which was the name of a group of punk rockers in 1984. That was at the Massachusetts College of Art. I read in New York for the Open Line Poetry Series at Washington Square Church in 1983; in Newburyport, MA; all over Cambridge. I was very, very active.

JEWELL: Tell me about your second book.

BYRD: My second book is self-published, A Distant Footstep On The PLain. It was the late 1970s. I had been asked to read some poetry at International Women’s Day at Cambridge’s YWCA. I read a poem called “On Black Women Dying.” It deals with Black women I have known who have died and the Black women who were murdered in Boston whose murders were never solved. It was a kind of a serial killing. I read this poem with the accompaniment of music. That’s where Hermanas made their first appearance. It was a conga and a guitar. After that, I got telephone calls to do it again, so we got together and we performed more.

…in the fall of 1978

the Klan began

its “open recruitment”

in Boston City schools

and it was 1955

that a team of white professionals

interviewed colored children

from the Wayne County school system

as to whether their mammas and daddies

was for integration

or segregation

well, what i’m trying to get at

is that in the last 30 odd years

of my life span

there has occurred

a series of events

which have culminated

in the death and near dying

of Black women

across the continent of Amerika…

In 1979 I became unemployed, so I had more time to write. I was moving furniture and doing odd jobs around the city. It was a tough period in my life. I was hungry a lot.

JEWELL: So, how did you self-publish your second book, A Distant Foostep On The Plain?

BYRD: I was working on the Boston and Maine Railroad at the time I finished my second book and i couldn’t find a publisher for it. I self-published my book in 1983. I went to the printers and did a cost comparison. I had a friend who was a typographer and she worked on my manuscript. She gave me the negative for my book so I could get it published. She did this work for free. We took it to a local, small neighborhood newspaper that donated their space and we laid out the book in 24 hours. And then we drove it to the printer’s, it went to press, and a week later I went back and picked up three creates of it. It cost me $600 for 600 copies.

JEWELL: Why the title A Distant Footstep On The Plain?

BYRD: I am from Indiana. In a sense, it is my being true to my roots. It is a reaffirmation of who I am and where I’m from. A distant footstep on the plain. That’s what i was at one time.

I have a manuscript in the works now. It’s tentatively entitled In The house of Coppers. I feel good about this work. It feels better than the second book. It’s a different kind of work, probably closer to the first work. Maybe it’s a new threshold for me.

JEWELL: Which writers do you enjoy?

BYRD: Bessie Head, a South African, and hers Serowe: Village of the Rainwind and Collector of Treasures. I’m very fond of Samuel Delaney, the Black science fiction writer, and Octavia Butler, another Black science fiction writer. I dream of Toni Morrison and I like Gloria Naylor a lot. They are superior writers. There are a lot of African writers that I like: Ferdinand Oyono, who wrote The Old Man And The Medal; Yambo Ologuem, who wrote Bound To Violence; Mariama Ba, who was a very fine writer. I also enjoy Simone Schwarz-Bart, a Caribbean writer who wrote The Bridge of Beyond and the poetry of Marilyn Hacker and William Carlos William and Nicolas Guillén. I also have to give a nod to Sexton and Plath, though their work doesn’t interest me as much as it did when I was in my 20s.

0 notes

Text

“I know better than anyone that I’m more accustomed / to holding a knife / than holding someone’s hand.”

— Meggie Royer, from “Psych Ward Lover,” Potions for Witches the Boys Couldn’t Burn (via lifeinpoetry)

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

WHAT RESEMBLES THE GRAVE BUT ISN’T

Always falling into a hole, then saying “ok, this is not your grave, get out of this hole,” getting out of the hole which is not the grave, falling into a hole again, saying “ok, this is also not your grave, get out of this hole,” getting out of that hole, falling into another one; sometimes falling into a hole within a hole, or many holes within holes, getting out of them one after the other, then falling again, saying “this is not your grave, get out of the hole”; sometimes being pushed, saying “you can not push me into this hole, it is not my grave,” and getting out defiantly, then falling into a hole again without any pushing; sometimes falling into a set of holes whose structures are predictable, ideological, and long dug, often falling into this set of structural and impersonal holes; sometimes falling into holes with other people, with other people, saying “this is not our mass grave, get out of this hole,” all together getting out of the hole together, hands and legs and arms and human ladders of each other to get out of the hole that is not the mass grave but that will only be gotten out of together; sometimes the willful-falling into a hole which is not the grave because it is easier than not falling into a hole really, but then once in it, realizing it is not the grave, getting out of the hole eventually; sometimes falling into a hole and languishing there for days, weeks, months, years, because while not the grave very difficult, still, to climb out of and you know after this hole there’s just another and another; sometimes surveying the landscape of holes and wishing for a high quality final hole; sometimes thinking of who has fallen into holes which are not graves but might be better if they were; sometimes too ardently contemplating the final hole while trying to avoid the provisional ones; sometimes dutifully falling and getting out, with perfect fortitude, saying “look at the skill and spirit with which I rise from that which resembles the grave but isn’t!”

Anne Boyer, 2017

0 notes

Text

This, notwithstanding that the avowed aim of the American protest novel is to bring greater freedom to the oppressed. They are forgiven, on the strength of these good intentions, whatever violence they do to language, whatever excessive demands they make of credibility. It is, indeed, considered the sign of a frivolity so intense as to approach decadence to suggest that these books are both badly written and wildly improbable. One is told to put first things first, the good of society coming before niceties of style or characterization. Even if this were incontestable -for what exactly is the "good" of society? - it argues an insuperable confusion, since literature and sociology are not one and the same; it is impossible to discuss them as if they were. Our passion for categorization, life neatly fitted into pegs, has led to an unforeseen, paradoxical distress; confusion, a breakdown of meaning. Those categories which were meant to define and control the world for us have boomeranged us into chaos; in which limbo we whirl, clutching the straws of our definitions. The "protest" novel, so far from being disturbing, is an accepted and comforting aspect of the American scene, ramifying that framework we believe to be so necessary. Whatever unsettling questions are raised are evanescent, titillating; remote, for this has nothing to do with us, it is safely ensconced in the social arena, where, indeed, it has nothing to do with anyone, so that finally we receive a very definite thrill of virtue from the fact that we are reading such a book at all. This report from the pit reassures us of its reality and its darkness and of our own salvation; and "As long as such books are being published," an American liberal once said to me, "everything will be all right." But unless one's ideal of society is a race of neatly analyzed, hard-working ciphers, one can hardly claim for the protest novels the lofty purpose they claim for themselves or share the present optimism concerning them.

Everybody's Favourite Protest Novel, James Baldwin

293 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monet Refuses the Operation

by Lisel Mueller

Doctor, you say that there are no halos

around the streetlights in Paris

and what I see is an aberration

caused by old age, an affliction.

I tell you it has taken me all my life

to arrive at the vision of gas lamps as angels,

to soften and blur and finally banish

the edges you regret I don’t see,

to learn that the line I called the horizon

does not exist and sky and water,

so long apart, are the same state of being.

Fifty-four years before I could see

Rouen cathedral is built

of parallel shafts of sun,

and now you want to restore

my youthful errors: fixed

notions of top and bottom,

the illusion of three-dimensional space,

wisteria separate

from the bridge it covers.

What can I say to convince you

the Houses of Parliament dissolve

night after night to become

the fluid dream of the Thames?

I will not return to a universe

of objects that don’t know each other,

as if islands were not the lost children

of one great continent. The world

is flux, and light becomes what it touches,

becomes water, lilies on water,

above and below water,

becomes lilac and mauve and yellow

and white and cerulean lamps,

small fists passing sunlight

so quickly to one another

that it would take long, streaming hair

inside my brush to catch it.

To paint the speed of light!

Our weighted shapes, these verticals,

burn to mix with air

and changes our bones, skin, clothes

to gases. Doctor,

if only you could see

how heaven pulls earth into its arms

and how infinitely the heart expands

to claim this world, blue vapor without end.

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

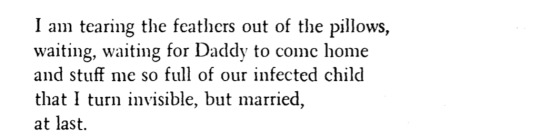

Ravit Raufman: The Affinity Between Incest and Women’s Mutilation in the Feminine Druze Versions of “The Maiden Without Hands”

Anne Sexton: Divorce, Thy Name Is Woman

230 notes

·

View notes

Text

Salvage

by Hedgie Choi

I have seen deer split open on the road and

thought

that's exactly what

those

soft and gentle

fuckers

deserve.

Some things happened to me in my formative

years that I don't want to tell you about

but some things happened to you too.

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Memory, origin of narrative; memory, barrier against oblivion; memory, repository of my being, those delicate filaments of myself I weave, in time into a spider’s web to catch as much world in it as I can. In the midst of my self-spun web, there I can sit, in the serenity of my self-possession. Or so I would, if I could.”

— The Scarlet House, Angela Carter

624 notes

·

View notes

Text

like with lolita I feel like even when people are defending the book they tend to go too far in the wrong direction and flatten it into "well obviously the book isn't sympathetic towards pedophilia, you're supposed to hate humbert and think he's disgusting at all times" and I just feel like that's reductive bc like. the book is absolutely not sympathetic towards pedophilia but imo you ARE supposed to find humbert funny and kind of tragic and charming and that's like. the point! like he's intentionally written to be all these things!

if the book wanted to just be like. a straightforward condemnation of pedophilia, then humbert wouldn't be the narrator. but it's not a book about child sexual abuse being bad -- like that kind of goes without saying, you don't really need to argue it -- it's a book about the ways humbert justifies his abuse to himself, and to the audience. it's a book that's largely about how stories are told, and the way personal and cultural narratives can be used to justify even the worst imaginable behavior. humbert doesn't describe himself abusing a child, he describes himself being 'seduced' by a 'nymphet'; he likens his relationship to that of dante and beatrice or petrarch and laureen to establish historical legitimacy and lend a sort of tragic romanticism to it. it almost feels like the book is less focused on the story itself, and more on the way humbert spins it. he isn't written to be an obviously hateable monster, he's written to be erudite and tragic and funny, and that's because the book isn't trying to teach you that child abuse is bad, it's demonstrating the ways that being erudite and tragic and funny can be used to normalize and justify something that you already know is bad. imo it's largely a book about the ways that someone can construct a mythology to convince themselves of anything, and how if we don't think critically about what we're told then we can fall into the same trap.

it's also absolutely a story about reading past the lines to figure out what's actually going on. like it's funny that the book has become such a touchstone for discourse about Media Literacy bc I really think that 'media literacy' is like. one of the core themes. like the book kind of requires that you ignore the way humbert writes to make out what he's actually describing; the worse his behavior gets, the more flowery and beautiful his writing becomes. the story the book tells if you buy into humbert's mythology and the story it tells if you don't are dramatically different.

like the ways that the book depicts dolores suffering are there, but you almost have to read past the narrative humbert presents to see them, right? like when he complains about dolores being irritable and cruel and moody, he's presenting the picture of a fickle and unreasonable WOMAN who is toying with his emotions. but when you read what he's actually describing instead of the way he describes it, it reads like a fact sheet on spotting child abuse! she has mood swings, she lashes out at people, nothing makes her happy, she cries herself to sleep most nights. if we read humbert's account at face value, she's a fickle seductress who gets a sick thrill out of hurting him; if we recognize his bias and intentions in writing it, she's a deeply depressed and traumatized child still attempting to resist her abuser despite everything she's been through. like it's as close to an exercise in 'media literacy' as a book can get in that regard.

8K notes

·

View notes

Photo

The colour blue, the colour of ambiguous depth, of the heavens and of the abyss at once, encodes the frightening character of Bluebeard, his house and his deeds, as surely as gold and white clothes the angels. The chamber he forbids his new wife becomes a blue chamber in some retellings: blue is the colour of the shadow side, the tint of the marvellous and the inexplicable, of desire, of knowledge, of the blueprint, the blue movie, of blue talk, of raw meat and rare steak (un steak bleu, in French), of melancholy, the rare and the unexpected (singing the blues, once in a blue moon, out of the blue, blue blood). The fairy tale itself was first known, in France, as conte bleu, and appeared in familiar livery between the covers of the Bibliothèque bleue. Mme de Rambouillet received her alcôvistes in her blue bedroom. As William Gass has written, in his inspired essay 'On Being Blue', 'perhaps it is the blue of reality itself': and he goes on to quote a scientific manual: 'blue is the specific colour of orgone energy within and without the organism.' It is a polar tint: of origin and end, and in consequence adumbrates mortality, too: Derek Jarman, the late artist and film-maker, recently flooded a screen with indigo in order to meditate on his and his freinds' death sentence from AIDS.

Warner Marina, From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers (1995).

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Phenomenology of the Prick You say, Let’s get naked. It’s 1962; the world is changing, or has changed, or is about to change; we want to get naked. Seven or eight old friends want to see certain bodies that for years we’ve guessed at, imagined. For me, not certain bodies: one. Yours. You know that. We get naked. The room is dark; shadows against the windows’ light night sky; then you approach your wife. You light a cigarette, allowing me to see what is forbidden to see. You make sure I see it hard. You make sure I see it hard only once. A year earlier, through the high partition between cafeteria booths, invisible I hear you say you can get Frank’s car keys tonight. Frank, you laugh, will do anything I want. You seem satisfied. This night, as they say, completed something. After five years of my obsession with you, without seeming to will it you managed to let me see it hard. Were you giving me a gift. Did you want fixed in my brain what I will not ever possess. Were you giving me a gift that cannot be possessed. You make sure I see how hard your wife makes it. You light a cigarette.”

— Frank Bidart, “Phenomenology of the Prick”

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Panthea

Oscar Wilde

(quite long, so under a cut)

Nay, let us walk from fire unto fire,

From passionate pain to deadlier delight,---

I am too young to live without desire,

Too young art thou to waste this summer night

Asking those idle questions which of old

Man sought of seer and oracle, and no reply was told.

For, sweet, to feel is better than to know,

And wisdom is a childless heritage,

One pulse of passion---youth's first fiery glow,---

Are worth the hoarded proverbs of the sage:

Vex not thy soul with dead philosophy,

Have we not lips to kiss with, hearts to love and eyes to see!

Dost thou not hear the murmuring nightingale,

Like water bubbling from a silver jar,

So soft she sings the envious moon is pale,

That high in heaven she is hung so far

She cannot hear that love-enrapturerd tune,---

Mark how she wreathes each horn with mist, yon late and labouring moon.

White lilies, in whose cups the gold bees dream,

The fallen snow of petals where the breeze

Scatters the chestnut blossom, or the gleam

Of boyish limbs in water,---are not these

Enough for thee, dost thou desire more?

Alas! the Gods will give nought else from their eternal store.

For our high Gods have sick and wearied grown

Of all our endless sins, our vain endeavour

For wasted days of youth to make atone

By pain or prayer or priest, and never, never,

Hearken they now to either good or ill,

But send their rain upon the just and the unjust at will.

They sit at ease, our Gods they sit at ease,

Strewing their leaves of rose their scented wine,

They sleep, they sleep, beneath the rocking trees

Where asphodel and yellow lotus twine,

Mourning the old glad days before they knew

What evil things the heart of man could dream, and dreaming do.

And far beneath the brazen floor they see

Like swarming flies the crowd of little men,

The bustle of small lives, then wearily

Back to their lotus-haunts they turn again

Kissing each others' mouths, and mix more deep

The poppy-seeded draught which brings soft purple-ridded sleep.

There all day long the golden-vestured sun,

Their torch-bearer, stands with his torch ablaze

And, when the gaudy web of noon is spun

By its twelve maidens, through the crimson haze

Fresh from Endymion's arms comes forth the moon

And the immortal Gods in toils of mortal passions swoon.

There walks Queen Juno through some dewy mead,

Her grand white feet flecked with the saffron dust

Of wind-stirred lilies, while young Ganymede

Leaps in the hot and amber-foaming must

His curls all tossed, as when the eagle bare

The frightened boy from Ida through the blue Ionian air.

There in the green heart of some garden close

Queen Venus with the shepherd at her side,

Her warm soft body like the briar rose

Which would be white yet blushes at its pride,

Laughs low for love, till jealous Salmacis

Peers through the myrtle-leaves and sighs for pain of lonely bliss.

There never does that dreary north-wind blow

Which leaves our English forests bleak and bare

Nor ever falls the swift white-feathered snow,

Nor ever cloth the red-toothed lightning dare

To wake them in the silver-fretted night

When we lie weeping for some sweet sad sin, some dead delight.

Alas! they know the far Lethaan spring

The violet-hidden waters well they know,

Where one whose feet with tired wandering

Are faint and broken may take heart and go,

And from those dark depths cool and crystalline

Drink, and draw balm, and sleep for sleepless souls, and anodyne.

But we oppress our natures, God or Fate

Is our enemy. we starve and feed

On vain repentance---O we are born too late!

What balm for us in bruised poppy seed

Who crowd into one finite pulse of time

The joy of infinite love and the fierce pain of infinite crime.

O we are wearied of this sense of guilt,

Wearied of pleasure's paramour despair,

Wearied of every temple we have built,

Wearied of every right, unanswered prayer,

For man is weak; God sleeps; and heaven is high;

One fiery-coloured moment: one great love; and lo! we die.

Ah! but no ferry-man with labouring pole

Nears his black shallop to the flowerless strand,

No little coin of bronze can bring the soul

Over Death's river to the sunless land,

Victim and wine and vow are all in vain,

The tomb is sealed; the soldiers watch; the dead rise not again.

We are resolved into the supreme air,

We are made one with what we touch and see,

With our heart's blood each crimson sun is fair,

With our young lives each spring-impassioned tree

Flames into green, the wildest beasts that range

The moor our kinsmen are, all life is one, and all is change.

With beat of systole and of diastole

One grand great life throbs through earth's giant heart,

And mighty waves of single Being roll

From nerveless germ to man, for we are part

Of every rock and bird and beast and hill,

One with the things that prey on us, and one with what we kill.

From lower cells of waking life we pass

To full perfection; thus the world grows old:

We who are godlike now were once a mass

Of quivering purple flecked with bars of gold,

Unsentient or of joy or misery,

And tossed in terrible tangles of some wild and wind-swept sea.

This hot hard flame with which our bodies burn

Will make some meadow blaze with daffodil,

Ay! and those argent breasts of shine will turn

To water-lilies; the brown fields men till

Will be more fruitful for our love to-night,

Nothing is lost in nature, all things live in Death's despite.

The boy's first kiss, the hyacinth's first bell,

The man's last passion, and the last red spear

That from the lily leaps, the asphodel

Which will not let its blossoms blow for fear

Of too much beauty, and the timid shame

Of the young bridegroom at his lover's eyes,---these with the same

One sacrament are consecrate, the earth

Not we alone hath passions hymeneal,

The yellow buttercups that shake for mirth

At daybreak know a pleasure not less real

Than we do, when in some fresh-blossoming wood

We draw the spring into our hearts, and feel that life is good.

So when men bury us beneath the yew

Thy crimson-stained mouth a rose will be,

And thy soft eyes lush bluebells dimmed with dew,

And when the white narcissus wantonly

Kisses the wind its playmate some faint joy

Will thrill our dust, and we will be again fond maid and boy.

And thus without life's conscious torturing pain

In some sweet flower we will feel the sun,

And from the linnet's throat will sing again,

And as two gorgeous-mailed snakes will run

Over our graves, or as two tigers creep

Through the hot jungle where the yellow-eyed huge lions sleep

And give them battle! How my heart leaps up

To think of that grand living after death

In beast and bird and flower, when this cup,

Being filled too full of spirit, bursts for breath

And with the pale leaves of some autumn day

The soul earth's earliest conqueror becomes earth's last great prey.

O think of it! We shall inform ourselves

Into all sensuous life, the goat-foot Faun

The Centaur, or the merry bright-eyed Elves

That leave their dancing rings to spite the dawn

Upon the meadows, shall not be more near

Than you and I to nature's mysteries, for we shall hear

The thrush's heart beat, and the daisies grow,

And the wan snowdrop sighing for the sun

On sunless days in winter, we shall know

By whom the silver gossamer is spun,

Who paints the diapered fritillaries,

On what wide wings rrom shivering pine to pine the eagle flies.

Ay! had we never loved at all, who knows

If yonder daffodil had lured the bee

Into its gilded womb, or any rose

Had hung with crimson lamps its little tree!

Methinks no leaf would ever bud in spring

But for the lovers' lips that kiss, the poets' iips that sing.

Is the light vanished from our golden sun,

Or is this dadal-fashioned earth less fair,

That we are nature's heritors, and one

With every pulse of life that beats the air?

Rather new suns across the sky shall pass,

New splendour come unto the flower, new glory to the grass.

And we two lovers shall not sit afar,

Critics of nature, but the joyous sea

Shall be our raiment, and the bearded star

Shoot arrows at our pleasure! We shall be

Part of the mighty universal whole,

And through all aons mix and mingle with the Kosmic Soul!

We shall be notes in that great Symphony

Whose cadence circles through the rhythmic spheres,

And all the live World's throbbing heart shall be

One with our heart; the stealthy creeping years

Have lost their terrors now, we shall not die,

The Universe itself shall be our Immortality.

0 notes

Text

Phedre

Oscar Wilde

(To Sarah Bernhardt)

How vain and dull this common world must seem

To such a One as thou, who should’st have talked

At Florence with Mirandola, or walked

Through the cool olives of the Academe:

Thou should’st have gathered reeds from a green stream

For Goat—foot Pan’s shrill piping, and have played

With the white girls in that Phaeacian glade

Where grave Odysseus wakened from his dream.

Ah! surely once some urn of Attic clay

Held thy wan dust, and thou hast come again

Back to this common world so dull and vain,

For thou wert weary of the sunless day,

The heavy fields of scentless asphodel,

The loveless lips with which men kiss in Hell.

0 notes

Text

“Oh, I could tell you stories that would darken the sky and stop the blood. The stories I could tell no one would believe. I would have to pour blood on the floor to convince anyone that every word I say is true. And then? Whose blood would speak for me?”

— Dorothy Allison, Two or Three Things I know for sure

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

the longer i live and create art the more i realize the categories of "edgy" are so socially constructed... i'll get called an edgelord for something i wrote and it'll just be like. something that happened to me or a friend that i cribbed for artistic inspiration. like oh wow people do see certain kinds of violence as inherently Unreal, like, the people they happen to are purely theoretical and couldn't actually be artists themselves, or even just like, present in totally typical daily life. and it's made me a lot more sympathetic to so-called "grimdark" art tbh!

811 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Nothing is all black, or all white. And nobody is all good or all evil. That also goes for the kidnapper. These are words that people don’t like to hear from an abduction victim. Because the clearly defined concept of good and evil is turned on its head, a concept that people are all to willing to accept so as to not lose their way in a world full of shades of grey. When I talk about it, I can see the confusion and rejection on the faces of many who were not there. The empathy they felt for my fate freezes and is turned to denial. People who have no insight into the complexities of imprisonment deny me the ability to judge my own experiences by pronouncing two words: Stockholm Syndrome. “Stockholm Syndrome is a term used to describe a paradoxical psychological phenomenon wherein hostages express adulation and have positive feelings towards their captors that appear irrational in light of the danger or risk endured by the victims” - that’s what the textbooks say. A labelling diagnosis that I emphatically reject. Because as sympathetic as the looks may be when the term is simply tossed out there, their effect is terrible. It turns victims into victims a second time, by taking from them the power to interpret their own story - and by turning the most significant experiences from their story into the product of a syndrome. The term places the very behavior that contributes significantly to the victim’s survival that much closer to being objectionable. Getting closer to the kidnapper is not an illness. Creating a cocoon of normality within the framework of a crime is not a syndrome. Just the opposite. It is a survival strategy in a situation with no escape - and much more true to reality than the sweeping categorization of criminals as bloodthirsty beasts and of victims as helpless lambs that society refuses to look beyond.”

— Natascha Kampusch, 3,096 Days in Captivity

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I’ve never seen grief like it. Grief like that, it’s like an animal. She’s not eating. She’s not sleeping. She’s whimpering. She’s sluggish. She’s not herself. The least thing and the tears come.”

— Jackie Kay, from Wish I Was Here: Stories; “Blinds,”

(via violentwavesofemotion)

2K notes

·

View notes