Text

I think a lot of folks in indie RPG spaces misunderstand what's going on when people who've only ever played Dungeons & Dragons claim that indie RPGs are categorically "too complicated". Yes, it's sometimes the case that they're making the unjustified assumption that all games are as complicated as Dungeons & Dragons and shying away from the possibility of having to brave a steep learning cure a second time, but that's not the whole picture.

A big part of it is that there's a substantial chunk of the D&D fandom – not a majority by any means, but certainly a very significant minority – who are into D&D because they like its vibes or they enjoy its default setting or whatever, but they have no interest in actually playing the kind of game that D&D is... so they don't.

Oh, they'll show up at your table, and if you're very lucky they might even provide their own character sheet (though whether it adheres to the character creation guidelines is anyone's guess!), but their actual engagement with the process of play consists of dicking around until the GM tells them to roll some dice, then reporting what number they rolled and letting the GM figure out what that means.

Basically, they're putting the GM in the position of acting as their personal assistant, onto whom they can offload any parts of the process of play that they're not interested in – and for some players, that's essentially everything except the physical act of rolling the dice, made possible by the fact most of D&D's mechanics are either GM-facing or amenable to being treated as such.*

Now, let's take this player and present them with a game whose design is informed by a culture of play where mechanics are strongly player facing, often to the extent that the GM doesn't need to familiarise themselves with the players' character sheets and never rolls any dice, and... well, you can see where the wires get crossed, right?

And the worst part is that it's not these players' fault – not really. Heck, it's not even a problem with D&D as a system. The problem is D&D's marketing-decreed position as a universal entry-level game means that neither the text nor the culture of play are ever allowed to admit that it might be a bad fit for any player, so total disengagement from the processes of play has to be framed as a personal preference and not a sign of basic incompatibility between the kind of game a player wants to be playing and the kind of game they're actually playing.

(Of course, from the GM's perspective, having even one player who expects you to do all the work represents a huge increase to the GM's workload, let alone a whole group full of them – but we can't admit that, either, so we're left with a culture of play whose received wisdom holds that it's just normal for GMs to be constantly riding the ragged edge of creative burnout. Fun!)

* Which, to be clear, is not a flaw in itself; a rules-heavy game ideally needs a mechanism for introducing its processes of play gradually.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm not sure who the original creator of this is, but it had to be shared

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Experiment in Guided Character Creation

Because of schedule changes with my work, and people being busy with life, I found it hard to keep up some of my local tabletop gaming opportunities. But I have also found that it gave me the option to do something nice for one of my coworkers.

Graciously, a friend of mine who's really never played D&D at all decided he wanted to start running a 5e game for me and several of our other coworkers, and with my sudden surplus of time, I offered to alternate games with him on Sunday nights after work so he could also have the chance to play, which of course he jumped at. So I polled the group and asked what they would want to play and they all selected Curse of Strahd.

A choice they may yet live to regret.

Regardless, since several of the players are relatively new, and the last time we made characters as a group for his game, I did a lot of the heavy lifting of helping everyone make their characters, I decided that for my game I would do a sort of guided, narrative infused character creation process, inspired by Adventurer's League packet for Ravenloft: Mist Hunters, going full production value on it with some excellent background music provided by the YouTube channel RPG Music Maker - Travis Savoie.

The process involved a series of read aloud sections designed in part to turn character creation into a sort of Bethesda RPG-esque (or maybe something more akin to Larian Studio's Baldur's Gate 3) character creation screen that could keep everyone working on the same steps at the same time, but also a method by which I could convey the tone of the world and genre that the players had chosen to exist in. I also featured a fair number of questions to prompt the players to think about their characterization in this process as well, hoping that I could urge them to create and deepen roleplaying hooks that would be useful in the game to come.

Though a lot of the text is lifted and adapted from the Mist Hunters packet, several of the questions I asked are purely my own, and I'm still proud of the results. The script I used follows:

You find yourself seated at a small table in a cramped, smoky teahouse. Thick, tallow candles shed dim light—the only light—throughout the room. An intricately patterned bone teacup and saucer is nestled atop a delicate lace doily. At the center of the table, steam curls from the spout of a silver kettle decorated with etchings of ravens in flight.

At first, you believe the table is set for only you, but slowly, you realize you are not alone.

X (x being the number of players + 1) other chairs like your own ring the table, and all but one of them is occupied by an indistinct shade of a person. You imagine them to be likewise confused and taking in their surroundings in a way not too dissimilar to how you are now.

Slowly, your fellow travelers begin to resolve, transitioning from shadowy impression to fully realized being, replete with form and color.

Here, I had each player give the basic physical description of their character, specifically their species/lineage, but also their fashion and any other distinguishing features they wanted to highlight, while allowing them the brief chance to react to the strangeness and roleplay if they wanted to, but reminding them that the remaining aspects of their characters, such as their class and background could be revealed in due time.

A moth-eaten curtain on the far side of the room opens, and a shrouded being enters the room carrying a human skull, gilt in silver and glass. They peer at you from beneath their cowl with eyes like glowing points of amber and consider you quietly before approaching the table. "Welcome, travelers. How fortunate you are to find yourself here, in the place betwixt." They gently lift the top of the skull away—revealing the dried tea leaves and a slender silver spoon contained within.

In turn, they scoop a measure of dried leaves from the skull with practiced grace and sprinkle them into the teacup in front of you before filling the cup with water.

“This tea is special; indeed, a rare treat,” the otherworldly tea-monger says. “To those who can appreciate it, it can—nay will—provide the answers to many questions—even those that you don’t know you have.”

“Smell the tea…lean over and breathe in the steam. It’s likely that the tea will smell differently to each of you as it sends your sleeping mind into its past.”

The scent is pungent but not unpleasant, unique to each of you. As the aroma teases your nostrils, your mind stirs and suddenly you feel more aware of the whole of your being than perhaps you ever have before.

At this point, I had each player roll for their ability scores. Typical 4d6, dropping the lowest, and assigning them as they pleased before assigning their modifiers (+2 to one stat of their choice, and +1 to another, per the method described in Tasha's Cauldron of Everything). Still, I did manage to inject a bit more theatricality into the process by obligating them to roll with the dice provided:

“Now, my friends,” the being whispers, “drink deep of the tea and let the mists of your own past reveal their secrets. You cannot know where you are going without first understanding where you are from. You cannot welcome others without first accepting yourself. You cannot prepare for the future without first facing the past.”

For a moment all seems normal as the flavor of the hot tea lingers on your lips. And then your mind is sent reeling. For a moment you feel as though you are trapped in a sort of peculiar gravity, your body at once leaden and yet weightless. Up and down, forward and back, become meaningless distinctions. An unknowable period of time passes. Seconds or minutes, perhaps even hours, but eventually the fog in your mind begins to coalesce, images and memory dancing across it like the light from a stuttering projector, guided by the shrouded being’s haunting voice.

“What seed was planted in your youth that grows now to fruition? What is your background?”

Here I helped them choose their backgrounds and mark down their skill proficiencies, tool proficiencies, and languages (if any) they gained from their background, as well as the background’s Feature and starting equipment. Personality Traits, Ideals, Bonds, and Flaws I told them will come later. And while we did this, I also had their mysterious host pose them some questions to consider:

What is the world you hail from like? What was the culture you were brought up in like? (Anything between typical medieval fantasy and Jack the Ripper’s London was acceptable. Steampunk and Magic punk style settings like Eberron were also acceptable. After all, Ravenloft can steal its heroes from anywhere.)

In your earlier days, before you became an adventurer, what was it that motivated you? Did you have a profession?

How did the condition of your existence define you? Did you love to work, or did you work to live?

Do you have a family? Who are they? Do you still keep in touch or are they long lost to you?

After long moments locked in the theater of recollection, the voice continues, urging you through the veiled halls of the decrepit crypt that unfolds within your mind. “What event transpired that led you to choose a different path? What is your class?”

At this point I had all them pick out their character classes and mark down their starting hit points, class proficiencies, starting equipment, and level one class features. Also, during this process, they were given more questions to consider:

What catalyzed you to begin your life as an adventurer? How did you view becoming an adventurer? Fated? Hopeful? Pragmatic? Reluctant?

Your peers know of you because you possess a Feat that places you above the rank and file. What is it? Was it talent, naturally gifted, or is it a skill you developed through training? (This question exists specifically because I have a house rule where I grant every character, not just variant humans, a free feat at level one and it seemed as good a place as any to put that step of character creation in play and help them choose.)

Have you had a noteworthy previous adventure? How did it go?

Did you gain any fame or notoriety beyond your immediate circle early on in your career due to your abilities or talents? Did it earn you a moniker?

Have you witnessed any great horrors in your adventuring career? If so, how have they left their mark on you – physically, mentally, emotionally? How do you cope with it?

More time passes, as visions churn in your mind, emerging from the mist like specters before collapsing back into the fog. Again, the being speaks to you. “Reflect upon your demeanor, your motivations, desires, and dreams laid bare. Insights are never possible through the stories we tell ourselves alone in the present. Allow the tea to continue to illuminate you.”

Finally, we reached the point where I wanted them to pick out their Personality Traits, Ideals, Bonds, and Flaws, and told them they could use the tables from their backgrounds to inspire them, but first, I wanted them to pose some more questions for them to consider. Help them shape what those other answers might have been in their own way, rather than what was in the book if they felt so compelled:

What makes your skin crawl? What can turn you from a hero into a whimpering babe? What is your seed of fear? (Seeds of Fear are a mechanical idea introduced in Van Richten's Guide to Ravenloft and play directly into the expanded role of the Fear Condition and Stress mechanics which we decided we would use, as well as offering them something they could potentially gain inspiration from in game by roleplaying it well)

Though we might struggle against them, many a creature is as much a product of the better angels of their virtue and the darker demons of their vice as they are of their willful choices. Which virtue best describes you (Chastity, Temperance, Charity, Diligence, Kindness, Patience, Humility) and which vice? (Lust, Gluttony, Greed, Sloth, Envy, Wrath, Pride)

Are you rational or passionate? Do you take considered action, driven by logic? Or are you led by your heart, leaping before you look?

How self confident are you? Do you stride boldly forth, self assured in your choices, or do you constantly question your own motives?

Are you sophisticated or superstitious? Do you fancy yourself to be well educated and experienced? Or do you rely on homespun wisdom, informed more by ritual and folklore?

What is your greatest love? For what or whom would you make sacrifices? Anything? Nothing? And would you sacrifice yourself? Or would you rather sacrifice someone else?

What is your greatest regret? Do you have any memories that haunt you at night?

What fascinates you and draws your interests? Art and Philosophy? Magic or Monsters? Swordplay and Warfare?

What are your habits? Do you have any patterns in your life? Rituals which you feel compelled to enact?

How strong is your faith? Are you the sort to go only on high holy days or are you truly pious? Or do you instead believe that the gods care little for mortals and you are on your own?

Do you have a hope or a dream? Something that you want or need? What desire, hidden or not, continues to drive you.

Questions posed, I think had them turn to their ideal, bond, flaw, and personality traits, using the chosen background and their answers for inspiration, or allowing them to simply roll if they preferred. I also told them that their personality traits could be changed or added to whenever they found a good reason to do so. These elements were not necessarily locked in stone as people are allowed to grow and change.

Finally, the fog begins to fade completely from your mind and you find yourself in the dark, smoke filled tea house once again. The being, seated in the Xth seat (Again, number of players +1), closes a tome, one you had not been aware it had even produced, in which it had been writing and recording your meditations, and returns quill to ink pot before it spreads its arms wide, indicating that it speaks to all of you. “The tea has shown you what it believed you needed to know. You have learned about yourself today, but your journey has only just begun.”

The shrouded figure motions to you to look down at the table before you, where you see that both tea cup and saucer have been replaced by a small package, wrapped in black paper and topped with a ribbon of frayed, yellowing lace. Next to this sits an envelope, likewise of black paper, gilt with silver and sealed with red wax. “Take with you the treasure you find within, and mind the invitation you have been given..."

Here, finally, I had each of them roll 1d100 and consult the horror trinkets table from Van Richten's Guide to Ravenloft. Just a funny little something for them to carry with them into the game... but something I fully intend to find a way to weave into the narrative if I can manage it.

Ready or not, your lives are soon to be forever changed, Mist walkers…”

Its final words spoken, the being rises from its chair to retreat back behind the curtain from which it emerged, taking it's heavy tome along with it. Somewhere in the gloom around you, a grandfather clock chimes 13 times as one by one the candles in the room flicker and go out, guttering as a chilling breeze sweeps through, bringing with it a rising veil of fog.

When the last candle is extinguished and all is cast in darkness, you suddenly awaken with a frightful start in more familiar surroundings, still resting wherever it was that you laid your head when you fell asleep the night before.

Clearly the vision must have simply been a nightmare… a hallucination of bad food or too much drink… but no… As you take in your surroundings you see it... your eyes catch sight of a small box, wrapped in black paper, torn open and its lace bow discarded, and the unopened invitation, still sealed with red wax…

When it was all said and done, the players had a great time and they had completed characters, set and ready to step into the mists of Ravenloft and set out to tackle the Curse of Strahd. We probably wont actually get to play again for a couple more weeks, but that's fine. It will give them more time to ruminate on their characters and me ample time to prep.

I think, rather than running them as level 1 characters through Death House, I will instead use The House of Lament from Van Richten's Guide to Ravenloft. I think it will give them more chances to really experience the haunted house vibes the setting can offer, and more time and ease of getting used to the Fear and Stress mechanics we will be layering onto the game.

Either way, I am very excited.

#ttrpg#role playing games#fiction first#5e d&d#character creation#ravenloft#curse of strahd#spooky vibes

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not a new observation, I know, but I feel like the demo for Final Fantasy 16 makes it very clear that Final Fantasy has moved beyond a genre and is now officially a brand constructed of specific themes and tropes.

Like, they have been playing with the series for years now, having two MMOs in the mainline series and plenty of spin off games that had wildly different mechanics, but with yet another numbered game releasing, now essentially playing like Devil May Cry in a lot of ways, we can see instead that it's connection to Final Fantasy conceptually comes not from it being a traditional turn based, menu RPG but instead is in the centering of the familiar summons like Titan and Phoenix and the fact that the first real boss of the demo is a Marlboro.

I suppose time will tell if the fan base is ready to embrace the series as a loose pile of concepts, as opposed to a style of game, or not.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quiet Spaces between Adventures

The playtest materials for Fabula Ultima have been a fascinating look at the ongoing development for a game I already enjoy. Meant to offer a greater spotlight to resting scenes from the core rulebook, the concept of Camp Activities provides an additional host of options to these resting scenes beyond merely just modifying or increasing a character's bonds.

In essence, Camp Activities are little mechanic prompts--like using the camp forge or sleeping peacefully--that allow you to frame your resting scenes in different ways and receiving different results. Each player is offered two such Camp Activities, meant to be chosen at character creation, and the book advised make sure you avoid redundant Camp Activities within the same group while also choosing ones that fit your player character's concept and identity.

Like many things in Fabula Ultima, I find it very cute and very serviceable for what it does... but I also find it a little bit arbitrary that some character who did not choose Sleep Soundly during character creation, or was not allowed to because someone else chose it, is mechanically never allowed to do so.

Yes, I understand that this is sort of a silly, hyperbolic statement, but it's also true from a purely mechanical perspective. And it was that thought that caused me to think, upon reading how Downtime worked in Armour Astir, that I had found a better way.

In Armour Astir, downtime scenes are mechanized by scenes and tokens. Each player character is granted a single scene that they are allowed to frame, inviting other players in as they see fit, and two tokens which players may essentially use to gate crash other people's scenes. Framing a scene provides an explicit benefit to the scene framer alone, but tokens that the players possess may be spent to gain additional benefits from a menu of options associated with the scene... or allow a player to enter the scene and similarly pick a benefit from that same menu. In this way, players can take the benefits from resting scenes that they want, and they need only consider what they want their primary benefit (from their scene selection) to be and what secondary benefits they wish to purchase (with their tokens).

And it doesn't stop their, either. The Downtime rules for Armour Astir also allow the GM to get in on the action, granting them one token for each player character at the table. These tokens be spent to interact with the players by asking them questions or reframing ongoing scenes in new and different ways. They may even be used on cutaways to the enemy camp where other characters are having their own down times that can be used to purchase penalties to the players or upgrades for foes.

I found it immediately more intuitive (to my mind) than the Camp Activities system, and more open ended for my own players, so I set to making this first draft of an attempt to use the same mechanisms for Fabula Ultima.

Downtime & Camp Scenes

Between their adventures and during their inevitable rest stops on the road, characters have time to themselves to rest, prepare, and do their own thing. This downtime is played out as a series of scenes, each led by a single player who may invite others into it. They don’t need to be elaborate or long–they can be as simple as describing the actions you take or you may find yourself continuing to invite other characters into the scene as it continues to unfold.

Each player gets to lead 1 Scene, and each also gets 2 Tokens to spend during any player’s scene (even their own) to gain further benefits. The Gamemaster also takes 1 Token per player, which they may spend to refocus a scene or ask a question of the player characters which they must answer. Alternatively, these GM tokens may be spent to frame a cutaway scene to reveal an unwelcome truth or show signs of a future threat and gain 1 Hold. These Hold may be spent, 1-for-1, to allow one non-villain enemy to reroll a single check or recover 25 HP or MP.

Finally, you may choose to frame your Scene but not take the benefit described: if you do so, you may choose another player to gain an extra token for this Downtime.

Plan & Prepare

The leading player takes the time to focus on the situation ahead: they may start or advance a long-term project to learn more about a subject, or gain 1 Fabula Point to represent the plans they’ve made. They frame a short scene around this, either alone, or with invited characters.

During the scene, anyone may spend a token to choose one:

Plan & Prepare, as above.

Check the maps, allowing the group to reroll the die on their next travel roll.

Share notes with someone, adding or adjusting an emotion in a Bond.

Give or Receive a Pep talk, granting or gaining 1 Hold. This Hold may be spent at any time to recover 25 Mind Points before your next rest.

Rest & Recuperate

The leading player takes the time to tend to what ails them or spend some time relaxing: they may recover all their Hit Points and Mind Points and clear their Status Effects (if they do not/cannot use a Magic Tent or pay for a room in an Inn if available), or pass the time resting and gain 1 point of Experience and add or adjust an emotion in a Bond. They frame a short scene around this, either alone, or with invited characters.

During the scene, anyone may spend a token to choose one:

Rest & Recuperate, as above.

Sleep Soundly, gaining 1 Hold. This Hold may be spent to perform an additional action on your turn before your next rest.

Meditate and center yourself, gaining 1 Hold. This Hold may be spent to either halve the HP loss from a single source or halve the MP cost of a single spell or ritual before your next rest.

Prepare special rations, gaining 1 Hold. This Hold may be spent at any time to allow yourself or another character to recover 25 Hit Points before your next rest.

Tinker & Train

The leading player spends time working on a project or engaging in martial training drills: they may start or advance a long-term project (per the project rules on pg 134 of the core book), or gain 1 Hold which may be spent to grant any attack the multi (2) property, or increase the attack’s multi property by 1. They frame a short scene around this, either alone, or with invited characters.

During the scene, anyone may spend a token to choose one:

Tinker & Train, as above.

Burn the Midnight oil, choosing 1: Generate 1 point of progress for a single Project of your choice; Repair a damaged item owned by the group; Create a single basic weapon, armor, or shield of your choice (pages 130-133 of the Core Rulebook); Destroy a single piece of equipment owned by the group and obtain a material whose value is equal to the cost of the destroyed item.

Give or Receive some pointers, granting or gaining 1 Hold. This hold may be spent to gain +4 to an Accuracy Check or a Magic Check for an Offensive spell once before the next rest.

Ask for a Magic lesson, gaining one use of a Spell another character knows until your next rest (Normal rules for casting the spell still apply).

Explore & Exchange

The leading player spends time trying to see what kinds of resources they can muster, whether through exploration or trade: they may either encounter a friendly merchant allowing them to exchange Zenit for any Basic Equipment (pages 130-133 of the Core Rulebook) or a selection of Materials and Rare Items (determined by the GM) or roll on the Exploration and Gathering table below. They frame a short scene around this, either alone, or with invited characters.

Exploration and Gathering table

1: H-help! The entire group gets caught up in an easy conflict against a threat whose level is equal to the group level.

2: Will these be okay? Choose: Regain 1 Inventory Point, 250 Zenit worth of Materials, or 2 ingredients with random tastes (for the Gourmet Class)

3 - 5: Hoho, this can be useful! Choose: Regain 3 Inventory Points, 500 Zenit worth of Materials, or 3 ingredients with random tastes (for the Gourmet Class)

6: Jackpot! Choose: Regain All of your Inventory Points, 1000 Zenit worth of Materials, or 3 ingredients, each with a taste of your choice (for the Gourmet Class)

During the scene, anyone may spend a token to choose one:

Explore & Exchange, as above.

Spend time working or in the field with someone, add or adjust an emotion in a Bond.

Learn something new or find something useful, start or advance a long-term project of your choice.

Run into trouble; resolve it as an easy conflict against a threat whose level is equal to the group level, and see what you learn or acquire.

At the moment, I'm not certain if they'll work well or not without playtesting. Or if my ideas here are even any good. But I do think it's a neat idea and something that I'm interested in playing around with.

#role playing games#fabula ultima#ttrpg#jrpg#game mechanics#fiction first#complex systems#house rules#game design#armour astir

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The campaign switches between two modes, in which the players play two separate characters.

Mode 1: level 20 Good Guy Heroes that have already saved the realms, brought peace, and are tying up all the loose ends between mortals, gods, and demons to ensure the peace is lasting without cruelty or malice.

Mode 2: level 1 Cringey Loser Bad Guys questing and scheming to become relevant threats in a peaceful and hostile world that still definitely remembers how to fight evil.

464 notes

·

View notes

Text

Running a game and short on ideas? Here to help!

Last minute treasure: Potato

Last minute dungeon location: Potato

Last minute enemy: Potato

Last minute helpful NPC: Potato

Last minute setting: Potato

Last minute dice: Potato

Last minute game group: Potato

507 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the most common questions I get about my games is "can I play as this? can I play as that?", and I'll level with you: basically every game I write is about a narrowly focused experience, so if you're the sort of player who's afflicted with the contrarian urge to insist on playing a character who's the exact opposite of whatever type of character a game is notionally about, regardless of what type of character that is, you're probably not gonna have a good time.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Cori's dad is corporatecore, he's blandmaxxing, fully greypilled friendsatthetable.net/palisade-07-the-canvas-of-dreams-pt-2

9:57 PM PDT, 20 April 2023 (Source)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mechanizing What Matters

As a Game Master, I frequently find that I have a desire to tinker with the rules of games, especially games that I love. Sometimes it happens because I find a particular game lacking in some area or other and think that I might be able to correct it. Other times, I simply encounter a mechanic in another game entirely that I become obsessed with and want to see it put to use. Especially if I feel like the second game in question is one I might be waiting a long time to actually get to play with any frequency. If at all.

This particular case definitely falls into that latter camp.

Generally speaking, I believe that game mechanics that step beyond the fundamentals–the engine under the hood that explains how you accomplish x or y task–should exist for two reasons: they should encourage certain types of behaviors from players that you, as the GM, wish to cultivate and they should reward the players for doing those things. A good example of what I mean that springs to mind was when I wrote my post, Hacking the Game, talking about changing the rules for Fabula Ultima. I mentioned how I wanted to change the way Experience points were awarded to better encourage a sense of exploration and goal-orientedness, as well as put a portion of the effort of awarding experience on the players themselves as they voted for one another to get awards as a means to encourage attentiveness and constant engagement.

Now, having fully read and digested the rules to Armour Astir: Advent, I again find myself debating the merits of flexing or changing the rules of Fabula Ultima once again, for the sake of cultivating a particular sort of experience I want to see at my table.

The Rule That Is: Bonds

In the game, there is a system for cultivating emotional attachments, or Bonds, between one’s character and other characters, or even nations, kingdoms, organizations, or religions. It’s a relatively simple mechanic, elegant in its design and I even find it somewhat cute. It’s functional and easy to understand and is a good entry point into the concept of mechanized emotional attachment if a particular player’s past experiences see them coming from a game that does not feature this kind of mechanic.

By default, you can have up to 6 bonds, all with varying levels of effectiveness based on their emotional strength, as seen below:

In raw game terms, a Fabula Point can be spent to Invoke a bond while making a skill check to represent how the relationship and its associated emotions spur the character onward, granting you a +1 to +3 to roll, depending on how deep that relationship is. Meanwhile, for Group Checks, if one or more of the Supporting Characters has a bond with the Leading character, the single highest strength Bond gets added to the group check as an additional bonus to the roll. A few other niche cases do exist, like the Darkblade class ability Heart of Darkness, which allows you to immediately create a Bond of Hatred towards a creature that puts in Crisis–below half HP–once per scene or the Rare Item Bow of Frozen Envy that allows you to recover 5 MP on a successful attack roll, so long as your character has a Bond of Inferiority on their sheet.

As I said above, it’s simple, elegant, and functional, especially the way it’s nested into the rest of the game’s rules. The mechanic and its text prescribes particular ways of thinking about the subject of your bonds and encourages you to see the increase of inherent strength of the bond as a deepening of the relationship's emotional weight and value…

Unfortunately, I also find it somewhat limiting and a little arbitrary. Obviously the six chosen emotions can be read in a number of ways, but one could argue that they’re also loaded terms, boxing a player into particular modes of thought about other characters or things. And I don’t know about you, but I have definitely felt both Admiration and Inferiority towards other people in my life at the same time. These do not have to be mutually exclusive concepts but for the purpose of mechanical game terms, they absolutely must be. Perhaps I’m just picking nits on this one, but I find the guard rails to be a little annoying, especially as a Game Master who has spent enough time running PbtA games for a group that is familiar enough with the concepts of bonds or Hx to grok what the game is shooting for.

Beyond that, Bonds as presented are entirely one way. You, as a player, can choose to form a bond towards another player character or an organization or concept, and there’s no expectation of reciprocity at all. Certainly, I can understand how that would make sense if your Bond was towards The Church or some other monolithic organization. Such a group might realistically have no reason to even know you exist, after all, but it feels a little sad to me that you might devote your characters emotions, good or bad, towards another player character or NPC, and see that effort go entirely unanswered. And yes, I know, sometimes life do be like that, but this game is specifically trying to model games like Final Fantasy or the Tales of X series who’s feet are firmly planted in anime and arch genre tropes. These are stories where another character’s indifference towards your own shouldn’t just be a cavalier fact of life: You should be able to weaponize that shit.

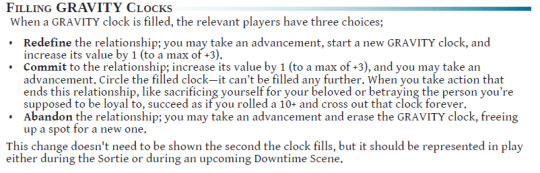

The Rule I am Obsessed with: Gravity Clocks

Gravity Clocks in Armour Astir are similarly meant to represent your character's relationships and attachments, but they do so in a different and, I think, more mechanically interesting way. They do not simply measure how many emotions a particular bond or attachment has. The book itself states: they are countdowns to when a relationship is challenged, confronted or addressed.

A Gravity clock can be declared at any time (though you may only be part of 3 clocks at a time, as well as 1 for your Rival should you acquire one), so long as both parties feel that it is appropriate. They come in the form of a 6 segment Clock with a word or short phrase that sums up the relationship and starts empty, offering the relevant player (or players) a +1 by default, but can be increased to a maximum of +3 as the clock evolves.

Mechanically speaking, whenever you would make a move in Armour Astir that involves the other party of a clock, you may add the clock’s value instead of the normal trait or value and doing so causes the clock to advance. And then, when the clock is filled, some real cool stuff can happen:

And this doesn’t even begin to touch on how absolutely wild Rival Clocks can get.

The game frames Rivals as recurring characters who appear again and again to challenge specific players who have earned their attention. They don’t need to explicitly be foes that are gunning for a player in an antagonistic way either. They might be an ally with a competitive relationship, someone the player is trying to impress (or vice versa), and so on. No matter the case, however, they’re essentially treated as main characters with a Gravity clock tied to their Player Character Rival, and are represented textually by a Need (what their faction demands of them, what they are obligated to do, etc), and a Want (what they want from their counterpart), which is meant to help direction their fiction and also provides the Rival with a metacurrency called Leverage that the GM can use in a variety of ways.

When a Player Character interferes with a Rival’s Need or indulges their Rival’s Want, their Leverage Increases, and they gain 1 Hold. This Hold can be spent by the Game Master, at any time, 1-for-1 to do the following:

Make the player character act in Confidence or Desperation (altering the way dice are rolled).

Ask a challenging question which must be answered.

Appear somewhere that they are not expected.

On the page, these rivals are represented like this:

As you can see, the idea of Gravity Clocks advancing in Armour Astir is inherently tied to your character advancing and growing stronger, but it also becomes something of a currency that can be used and/or discarded as the situation requires.

Additionally, the clocks themselves immediately establish a two way connection between parties that grows and evolves when either party of the clock leans on that emotional connection as a means towards success. Further, given the somewhat vague way in which the Gravity Clock can be named and defined, both parties are not required to name their clocks in the same way. What matters is that the emotional link exists between the two parties, but the way each party defines that link can be as varied and complicated as real social and emotional connections are between actual people: one player's Fast Friends clock could just as easily be another player’s Ally of Convenience clock.

Adapting the Mechanic

So, with both mechanics laid out, the question becomes how would I do it, if I decided to make the change.

On the most basic level, the amount of potential bonus a Gravity Clock can provide is equal to what a Bond can do. In that respect it doesn’t need any massaging. Spend a Fabula Point, gain the bonus from +1 to +3, advance the clock, and move on.

In terms of their function in Armour Astir, each time a character fills a Gravity Clock, they are granted an advancement, in addition to the other mechanical benefits of the clock filling. For those not familiar with PbtA games, an advancement is essentially the same as gaining a level. I find myself torn between wanting to keep as is, instantly granting a character in Fabula Ultima a level up, or reducing it to a mere sum of experience points (probably between 2 and 5). It is incredibly thematic for anime and games inspired by anime to have moments where a person’s emotional state pushes them to new, previously unknown levels of power. However, because activating the benefit of the Gravity Clock to add it to your roll as a bonus would also require the expenditure of a Fabula Point–itself is a means of gaining XP in the game–I fear it might cause players to level too quickly if I just simply handed them a level for improving their relationships. Doubly so because the Gravity Clock can be shared between two players and both of them would potentially be gaining the same benefits from filling that clock.

Additionally, Committing to a Gravity Clock–where you circle it and lock it in as stated above–comes with the ability to sacrifice that clock forever and instantly succeed as though you had rolled a 10+, PbtA’s best possible result, in exchange. This one I find less troublesome to think about how I would implement as a rule. I would likely treat it as though the players had rolled a Critical Success, with the player’s High Roll being equal to the maximum of the lowest of the two dice used in the test, should it happen to matter. In this way the players should be guaranteed their success, within the bounds of what they would normally be capable of, and would also be granted an Opportunity per the standard rules of Fabula Ultima (Which is really just a laundry list of additional things that you can have happen in addition to getting the thing you wanted from your check, like Unmasking the goals and motivations of the enemy or causing a Plot Twist!).

On the Rival Clock side of things, the only thing that would likely take some doing to figure out is the Confidence and Desperation mechanics. In Armour Astir, these cause you to treat 1s on a d6 as 6 if you’re acting in Confidence, or 6s as 1s if you’re acting in Desperation. This is a very powerful mechanic that can drastically change outcomes and the flow of the game and one that does not map directly to Fabula Ultima very well. Potentially, I suppose I lean in even heavier and cause the Hold spent to cause critical success or fumbles, but that seems too heavy handed. Alternatively I could just port over the function of the mechanics, but extend them to the additional types of dice used in Fabula, but without play testing who knows what unforeseen consequences that might have.

Finally there’s the Fabula Ultima side of the equation to consider. First and foremost, you can gain more Bonds in the game that Armour Astir allows for Gravity Clocks, even when including the Rival Clock. This is perhaps not so bad, if you consider you might now also be using those clocks to gain XP or Levels depending on my final decisions, but we also have to consider other factors. Many of the Class or Equipment based calls for Bonds in the game are specifically about Emotions attached to the Bonds, rather than their numerical value, and without those, some mechanics work less well, if at all. It’s a problem that could probably most easily be solved by simply adding tags to the clocks, so that they might read as “Estranged Siblings (Mistrust)”, but even that seems a little clunky. Perhaps just leaving things open to interpretation, which was the whole goal to begin with, would be best.Regardless, it leaves me with things to consider, and more than likely I’ll want to play a couple of Campaigns of Fabula Ultima through to completion before I leap to making the change. Play testing the idea would also be a must, of course, as I would still need to settle on what the exact implementation and benefits would be, but I think it could lead to some really interesting and meaningful role play if instituted correctly.

#role playing games#fabula ultima#ttrpg#jrpg#game mechanics#fiction first#complex systems#house rules#game design#armour astir

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sic Semper Tyrannis

In my experience, just as many TTRPG campaigns focus on war and conflict against the powers that be as focus on exploring the wild and untamed places of the world. From stories of the companions of The Inn of the Last Home in Dragonlance to the punk rock rebels and Anarchists of Shadowrun, many times the motivating force of the story is the direct fight for survival in a world that is hostile to the very people and heroes that inhabit it. It's a well tread set of story tropes that offer clearly defined goals and villains and in built sense of drama, so it's understandable why so many stories would choose to focus on these themes.

And sometimes, if you're lucky, you get to fight those battles from the cockpit of a giant robot.

Armour Astir: Advent is a high-fantasy roleplaying game about striking back against an authority that seeks to control you. It is a game of rival pilots clashing in steel-clad Astirs, of soldiers holding their own against the odds, and of spies and diplomats twisting the world to their ends. It is not a game of careful preparation or pleasant truces; It's hard to change the world without taking a risk.

I first became aware of this game because of the excellent podcast Friends at the Table, when they played the game as part of their Road to Palisade series of games, leading up to the third season of their ongoing Divine Cycle of games. Immediately I was taken by the combination of high fantasy magic merged with the classic tropes of mecha anime that were apparent in the game as written, even if the cast was hacking the material to make fit into their more futuristic world they had built.

I felt compelled to track it down to read it for myself.

Inside the PDF, written by Briar Sovereign, I found a love letter to the Mecha Genre, drawing inspiration from such luminary series as Mobile Suit Gundam and Escaflowne, putting you in the cockpit of giant suits of armor as you stride across the battlefields of a war against an evil power. But like the series it draws heavily from, it does so with a distinct focus on the pilots inside their Astirs, rather than just focusing on the mecha and the carnage they can bring. This is a game with stakes and in interest in the relationships between people. It's a game that, as the intro to this latest season of Friends at the Table puts it, is about Empire, Revolution, Settler Colonialism, Politics, Religion, War, and the many consequences there of.

Running off of a modified version of the Powered by the Apocalypse system, Armour Astir is built on already accessible system with a distinct interest in narrative storytelling. You work together with your group to define your Authority--the oppressive power that the group of players are fighting back against--and your Cause--the group that backs and hands orders down to the player characters--and build a world around these two groups and their seemingly irreconcilable differences. From there, the players build their characters from the available playbooks--The Arcanist, The Imposter, The Paradigm, The Witch, The Captain, The Diplomat, The Artificer, and The Scout--and collectively define the Carrier--their White Base or their Normandy--from which they launch their sorties against the Authority and where they spend their downtime between missions. It's an elegant way to frame a world in conflict, and once again as I will always point out, it's a game interested in the collective construction of the world in which you're going to play, thereby creating a sense of player buy in from the jump.

Still, even as a PbtA game, AA:A still manages to bring its own novel concepts to the table.

Presumably drawing inspiration from 5e D&D, the game introduces the concept of Advantage and Disadvantage to the system. Where normally you would roll 2d6+Stat in a PbtA game, hoping to roll a 10+ and succeed without a cost, Advantage and Disadvantage allow you to roll more dice, keeping a number according to their respective rules. And they stack! If you find your self with 2 advantages, for instance, then you would roll 4d6 and keep the best 2. Or if you had 2 advantages and 1 disadvantage, you would roll 3d6 and still keep the best two as advantage outnumbers disadvantage. The only caveat is that you can never roll more than 4 dice for a move.

Then there's the idea of acting with Confidence or Desperation. Certain moves, approaches, and situations can cause you to act with either of this conditions, and they fundamentally change how the dice are read. If you're acting with Confidence in a scene, any 1 you roll on a d6 is instead treated as a 6, while acting in Desperation makes any 6 you roll instead be treated as a 1.

These two rules alone could be enough for me to really consider the game an evolution of PbtA, as using the mechanics together allows you to deeply calibrate the odds of success or failure of a given move to really match the fiction of the story your telling, but the interesting ideas don't stop there.

The game asks you to define your character by a set of Hooks, which are short phrases that define how your character acts and thinks about the world and the people around them. They're guide posts for the player, reminding them what their character is about, but they're also guide posts for the GM and for the other players. They show what kinds of situations you care about and want to be drawn into, and they can be rewritten as needed, and deepened or loosened by various rules interactions that make the hooks easier or harder to change in play. Hooks can even be sacrificed permanently, crossed off your sheet forever and buying you a new advancement for your character and the ability act immediately with Confidence as your character commits themselves to the fight and how the war has changed them.

Meanwhile, the concept of Gravity Clocks, presents an incredibly dynamic way to represent the relationships between characters. Representing the attachments you have with people and groups, these clocks are countdowns to when a relationship might be challenged, confronted, or addressed. They can be one-sided, or they can be shared between two characters, and evoked to add numerical bonuses to rolls, the clock ticking forward every time it gets used in this manner. And when the six step clock fills up, the game asks you to Redefine, Commit, or Abandon the gravity between you and the subject of the clock. Each option presents its own ramifications, in addition to allowing you to take a new advancement for your character, and I could gush about them in detail for hundreds of words more, but I think it's better to simply let the game speak for itself if you choose to read it.

Finally, and perhaps most interestingly to me, is the concept of The Conflict Turn. Played out between Sorties by the player characters at the Carrier level, the Conflict turn is meant to zoom out and show the greater context of the conflict. Here players direct the broader course of the struggle by playing out Conflict Scenes, directing challenges at one another through role-played scenes, reminiscent of Mobile Frame Zero: Firebrands by D. Vincent Baker. It allows you to shape the course of the war and the world at a truly macro scale, and depict scenes and conflicts that might otherwise get lost in a narrow focused game about a single group of pilots on a single carrier, acting on a single front in the war. It invites players to step back and look at the whole picture and really think about what two deadlocked factions can do or must do in order to win a broader conflict. And what the consequences of those actions might be.

All in all, Armour Astir is a fascinating game that takes Powered by the Apocalypse in new and interesting directions. It offers novel new mechanical concepts to the system, while also featuring the familiar Playbook driven structure. The party's Carrier and their Astirs feature a refreshing amount of build it yourself by hand customization, and the freedom to craft your own world with a conflict you and your players will care about really makes the game shine in my opinion. Not to mention it's in built focus on both the micro and macro scale aspects of the greater conflict, each in their own time, without getting so lost in the weeds of spreadsheet style attention to detail of other mecha focused games like Lancer or Battletech.

If you've ever wanted to suit up in a giant robot and take the fight to the enemy, Armour Astir: Advent is an excellent option to fulfill that narrative fantasy.

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

My autistic ass helping my autistic son write a cover letter

Me: No, the date has to be written out, like, the name of the month, then the day, comma, year.

Him: They're just making it hard on purpose, aren't they.

Me: There are just a lot of arcane rules for this. Think of it like glyphs.

Him: Right. You wouldn't want to summon the wrong demon.

Me: Correct. So, now you need a salutation.

Him: Mighty Oceiros, the Consumed King...

Me: Not that salutation.

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

Into the Perilous Wilds

I can clearly remember when I took my first, tentative steps into the hobby that would ultimately become my lifelong obsession. Sitting in a Walden Books on the floor, flipping through one of the Monster Manuals for Advanced Dungeons and Dragons and marveling at the artwork while I read the bits of lore written on the page to accompany it. After that, the first Table Top RPGs I ever played were, first, Shadowrun and that black book AD&D with the Barbarian on the cover.

This was an era where the Gamemaster was considered like unto a god. Prevailing Gygaxian advice was that players should defer to the GM's judgement and that the GM themselves should deeply understand the lore of their world, have answers for everything, be able to make harsh but impartial decisions on the spot. It was a point of view that had a huge impact on what I thought it meant to play TTRPGs and especially what it meant to be a GM for a very long time and would not change until much later in life when I encountered the indie revolution that swept through the space around the end of 3.5e/beginning of 4e when Powered by the Apocalypse games had their day in the sun.

PBtA games were the first games I really encountered that called out the idea of collaborative storytelling to an extent that caught my attention. They told you to ask your players their opinion, and featured moves with advice to ask the player themselves where they might have learned the information they new in character. These were questions that had implications on the lore of the world. In a heartbeat your players, rather than you as the godhead of the game, could shift the entire world in tone, or even turn the whole thing on its head. You might still control the Fronts, and the world itself might still be your character to play, but suddenly everyone had the creative freedom to change things in new and interesting ways baked into the mechanics of the very game.

I loved it.

Fast forward a few years and I would encounter a funny little book called The Perilous Wilds, a supplement for the PBtA game Dungeon World.

This little book is 76, digest-size pages, and had such a simple pitch:

The Perilous Wilds combines Dungeon World's approach to collaborative world-building with the old-school RPG reliance on random tables to generate content on the fly, woven together by modifications to the original Dungeon World travel moves. The main differences between the use of tables in The Perilous Wilds and their use in older RPGs is an emphasis on exploration and discovery over combat encounters, and the baked-in methodology of using randomized results as prompts rather than facts, to be interpreted during play.

The collaborative map-making guidelines and all of the tables are system-neutral (usable with any RPG rules). Although the tables are structured to tie directly into the rewritten travel moves, they can be used in any game in which a fantastical landscape is explored.

It was in this little book where I found a concept that was, perhaps not new, but one that I was incredibly taken with. Letting the players draw the map, and by extension, the world.

Starting from a discussion of the fiction of your world, be it a village on the frontier or even en media res as you emerge from a ruin temple into the wilds, you had your players a blank sheet of paper with a simple X on the map that says you are here. From there, you start with the youngest character in the party and proceed clockwise around the table. Each player is given the opportunity to add a region to the map, be they a swath of land or a sea, defined by either their prevailing terrain type or political boundaries, and then give that region a name. This step can be repeated as many times around the table as you like, but eventually you have to move on.

From there, each player is asked to places to the map. Areas, Steadings, and Sites get injected into the map, starting from the Fiction of which character is the most well traveled. Areas are like sub-regions, calling out interesting exceptions to a Region's overall theme. Steadings label the settlements of the territory, its villages, towns, keeps, or cities. Sites meanwhile, create your points of interest and landmarks. Each of these is meant to be given a brief description and name, the process continuing until everyone is satisfied with the amount.

After this the Oldest Character steps up and begins adding personal places. The book asks them to name two things: The place the character calls home and a place the character finds significant to them. These can be places already on the map, or newly named and added details like in the previous step, but the question must be answered of each: why? Why does your character choose to dwell where they do? What important thing happened to you at the point you've marked on the map? It tells you to shape the fiction of both the world and the character by considering such a simple but necessary detail.

After that, each player gets the chance to add connectors to the map in the form of roads, rivers, paths, or leylines. Anything that can be reasonably considered to connect to places within the world. Name it now, or name it later, but they must be drawn on the map as you further define the territory.

Finally, the book asks the most knowledgeable character to begin the process of sharing rumors and legends. Something the character has heard about any place on the map, but something that no one in the party can be sure to be true or false. The rumors must be noteworthy and provocative, the book advises, but each player has the chance to add to the depth of the fiction. Cutely, the book even offers the following advice:

This conversation might happen in character, or not. Ask clarifying questions; chide the speaker for giving any credence whatever to such malarkey; whistle in awe at the very idea.

And meanwhile the book itself speaks directly to the Game Master and asks you consider which of these rumors is really true, and what does that mean for the world?

All of this is excellent advice, and the procedure itself has been fun and engaging to work with every time I have put it to use in one of my games. It's also one of the primary reasons that I took to Fabula Ultima with such gusto, after reading that game's own advice and procedure on how to build a world. The two products are aligned in their ideals of what it means to create a world for cooperative storytelling, and the similarities in their process was striking.

But it goes beyond merely that.

The book is filled to the brim with interesting mechanics for the game Dungeon World, including new rules for followers and overland travel, Moves for handling the weather and compendium classes for your players to level into, but even past the mechanics built specifically for one game in particular, there are so many tables and system agnostic little details.

There's a Monster maker, a Discovery generator, Steading creator, and so much more. There are tables for creating quirks and details for people, places, and things, and a section that provides a whole array of rules for generating dungeons on the fly who's details can be fleshed out as you go and it's layout can be easily represented by a flowchart rather than meticulous lines drawn on graph paper.

And most importantly, the book simply tells you to trust your gut.

Yes, it offers you advice on how to prep between sessions, but it advises that a little bit of prep can go a long way. You don't need to worry about having all of the answers. Your campaign bible need not be so thick that you could bludgeon someone to death with it. All you really need is a sense of what is happening in the world and your gut instinct as a storyteller. You really only have to take a step back think more deeply on the game, its Fronts and its people and places, if you begin to sense instability in the world's fabric that you or your players find intolerable. With practice, the book says, you shouldn't need more than an hour or so between sessions to make the minimal, necessary notes for what comes next.

It's an excellent little tome, and one which I still use to this day, even though we're not currently playing any Dungeon World games. The tables provide me with rich inspiration and quick in-game answers to the question of what comes up during exploration. Its dungeon generation system has taught me that in theater of the mind play, a node map can be just as useful as a real one.

And when I feel my dedication to the ideal of collaborative world building and storytelling slipping because I want more answers or more control, I flip through its pages and read its advice as a reminder that we don't have to live in the castles that Gygax built any longer.

#ttrpg#indie ttrpg#Perilous Wilds#Dungeon World#inspiration#random tables#collaborative storytelling#world building#fabula ultima#pbta

46 notes

·

View notes