Text

龚贤 - 金碧山水 by Gong Xian (Qing dynasty)

There's a special style in Chinese landscape painting called 青绿山水 (Qinglu Shanshui) which uses mineral dyes to complete the artwork. Those artworks have major green and blue colors. During Song Dynasty, artists and scholars added is 泥金 (made of glue and powdered gold or other metals) to the dyeing materials. These landscape paintings are 金碧山水 (Jinbi Shanshui).

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

languages, travel, identity, grief

Maybe some of you have heard of Xu Zhimo's Second Farewell to Cambridge (徐志摩 再別康橋 Translation: Saying Goodbye to Cambridge Again, by Xu Zhimo | East Asia Student). It's an achingly lovely poem about a Chinese scholar who studied in the UK, and how he left so gently, taking nothing with him as he went. It brought me solace over the last year.

I thought for a very long time about how I felt about having to leave China, and what it felt like to mourn for a future that was never going to mine. I cried. How am I supposed to explain why? I'm not Chinese. I've got no family there, or a childhood to look back on. I couldn't explain it even to myself.

That pain was coupled with a type of uncertainty, a discomfort at myself for feeling so strongly. This feeling was not allowed. It meant - what? Something awful, probably. I was a racist, probably. I should hate myself, probably. Fetishization is the word that gets thrown around for white people and their time spent in East Asia at one end of the spectrum - at the other end it's just seen as embarrassing and deeply, you know, cringe. It's a self-interrogation - why do I feel so sad? Why do I feel this pull so strongly anyway, to a country that's not even mine? Why should it matter so much when I leave? I didn't feel like this grief has any sort of legitimacy. But it has taken from September - eight months after leaving - for me to pick up Chinese again.

I felt, for months, hollow and unsettled and drifting from place to place. I opened my textbook, and closed it again. The memories there were too painful. I'm not going to write about why I had to leave, but it wasn't by choice. I had loved the people in the school, even if it was for a short time. When you have no internet and are training eight hours a day, the days are coloured more sharply: bright and hurtful and wonderful all at once. We had no running water. It was in an abandoned hotel. I miss the monk at the temple door opposite the school, always on time at 6am to open it for our classes. I miss the folk at the local shop who invited me to watch films on their projector; once they killed a chicken for us. I miss the woman in the woods who gave me the chestnuts she had picked. I gave the chestnuts to the cook, and we steamed them and ate them by the lake. He wanted me to marry his son; he wanted it so strongly that he brought me pork, and desserts, and gave me paper, and promised me I could have a jade bracelet, that he would buy me a house. I miss the oldest martial arts teacher, who spoke in such strong dialect I could barely understand him. When I was sad and missing home one night, he told me that I should stay after dinner. In the silence and against the cicadas, he started to play the erhu for me. Later, my friend told me that he hadn't know what to say, how to comfort me; I was a foreigner and a young woman, after all. We had very little in common. But nobody has ever played a piece of music for me like that before.

And I miss X, my best friend there and partner in snack-smuggling crime. She is 19 years old, and a janitor's daughter, and one of the wisest people I have ever met. (She also rides an excellent motorbike, and lent me her hanfu, and we sped through the city giddy with our own daring and trying not to be caught.) We got matching haircuts; she had always wanted to cut her hair like a boy, and was too scared to do it alone. When I left, I told her to stay in touch: she shook her head. She said that some people were meant to know each other for some time, and no more. I think the death of friendship by attrition, by - as Elrond said! - the slow decay of time, is one of the saddest things of all. I deleted Wechat. I don't want to read over the old messages. By having this place - her, and the chestnuts, and the cicadas - as a memory, I can tuck it away it. I can keep it close.

I wrote a poem myself on the plane. That was the last I thought about China, the last thought I let myself have, in eight months. I kept myself away from it. It felt like a wound. And against that hollowness, there was constantly the question: Why should I have any right to miss this place? Who I am there? Why does it matter? We are all different people, wherever we go, and whoever we are with; we wear different skins, large or small. In China I was [...]. She was who I was. That name, that I introduced myself to people with - she was bright and friendly and tried to translate things just so. Everybody who goes as the only foreigner to a place - or the only foreigner that speaks the language - is a little bit self-obsessed. It happens. It's unfortunate, and something to guard against. But it also gives you its own kind of identity in a way: your identity is Foreigner. Your identity is a cultural bridge. Everyone you meet, in a country as friendly and curious as China, has questions about you. You stand with your feet in both worlds, and are not really part of either of them. That identity is easy to slip into, like cool water, like trying on new clothes. It's easier that thinking: who am I outside of that? Where am I going? I don't really know. I don't think anyone really does.

And then the second thing happens. I speak Chinese well, by this point. My accent is there, but it's slight. I am short, and have dark hair, and a generally similar build to many East Asians - so the questions I have got in the last few years have changed. Sometimes people think I have been raised here. Sometimes they think I am ethnically Russian, and nationally Chinese. Sometimes I get asked if I am half Chinese. Usually they know I am a Foreigner, 100% white - but not always. There is a peculiar rush that comes from that acceptance; from feeling the relief, just for fifteen minutes, that you belong. It's not about 'passing', or race-bending, or anything twisted - it's nothing so unnerving as that. It's just the human need to belong. Everyone gets tired of being stared at, after a while. And after a while, you start to think - I wish I understood. I wish they understood. I wish this were easy.

But then the conversation keeps going. You don't know a local word, or you misunderstand. You say something in a strange way, or you make a strange gesture, and the glass shatters, and - there you are again, naked again, exhausted again, explaining yourself again. That's the other half of it. There's solace in the Foreigner identity, because that means that's all you are. You don't have to think about your parents, or whether they worry about you so far from home; of course they do. The Foreigner is good and filial and a wonderful daughter. You can craft her into any shape you like. But it also marks you out again and again, endlessly and again, as Other.

There was a paper published a while ago that showed measures of acceptance of non-natives in native-speaking communities. It highlights a strange, but familiar experience to those who have lived abroad - the people who spoke the language to a medium level felt more accepted and less lonely than those that spoke the language to a high degree. It makes sense, and mirrors what I have found with both Chinese and German. When you speak a little Chinese, you are a wonder - a curiousity! Look at the Western girl go! People are kind, and curious, and will slow down to include you in conversations. You are thrilled with what you can access - all this knowledge, that other people don't have! Look how special you are!

And then you get better. And then you realise, cut by cut, that you will never be one of them. You don't want to be Chinese, per se; but you do want to be accepted. You are happy to be British; but you miss China like a wound, an old one, festering, even when it was never yours. How do you tell your family that you are not grieving a lost romance, a beautiful girl, but a language and a life? That there are words of majesty, of playfulness, that will never be yours? You speak well enough that people no longer bother to dumb things down, or explain them; you sit with your discomfort, smile painted on, because - you know. It's not bad. You understand most of it. And on the edge of that circle, smiling uncertainly, following the vast majority of what is being said, you are not clever enough and not witty enough to keep up with the chengyu, the cultural references, the slang, and the raucous laughter around you erupts, and you don't know what you've missed, and everybody says - she's quiet, that one. Maybe all the foreigners are? And all you are doing is sitting and feeling the distance between You and Them as heavy and as stifled in your chest as an ocean of dark.

So you go back. Back to your people. But when you sit with the other foreigners, you are apart. They laugh; what are these nutters doing? The Chinese don't make any sense. The Chinese do this - they do that. You sit there, and then there is a pressure building in your chest too, a discomfort, the desire to stand up and say - well, actually.

You are responsible for everything the Chinese teachers do, and have to explain things in a way that the students understand - Confucian thought, and Buddhist philosophy, translated in pithy bite-size adages for the West. You have no qualifications for this; everything you assert, you feel unsure. Uncertain. Someone else could explain it better, more nuanced, and you need to do more reading anyway - but here you are, and here they are, and you're the only one. And you do know. Not enough, but enough that their jokes, their pains, make you uncomfortable. You feel the need to defend both parties; to be a diplomat, every second of every day. In turn, when the students come to the teachers with problems, you have to translate their grievances in a way that the Chinese teachers will be sympathetic towards. Once I got asked: why do you never join us after class? Why are you always so quiet when you're not working? As a translator, you are always working. Every time you speak, you are working; what you choose to say, and what you choose to not say, and where you choose to intervene. You are building relationships, and disappearing, and you are becoming invisible, and you're a nothing, and you're everyone and you're nobody and nobody realises you are doing anything more than translating at all.

I wanted to stay. I couldn't have stayed. I wanted to be accepted as one of them. I wanted to be accepted for who I was. That means a foreigner. I wanted to be true to myself, which means that I would always be the Foreigner, which means I would always be apart from them. It is that contrast and juxtaposition which causes the grief. And there was never an ending to it, a resolution, a chance to reconcile myself (in China) with myself (in the UK), because all at once I had to leave. The grief comes most from the second arrow - not the pain of leaving, but the bewilderment of not knowing why I was in pain at all.

It's been eight months. Slowly, as spring comes, I feel like I am on surer ground. I can look at my old books, those painstaking notes, and I could look at new ones too and I'm starting to think, because this is what I tell my students, and maybe there's some truth in it - it's okay if you're not perfect. It's okay if you didn't achieve what you wanted to, and that the language - in its wholeness, and who can ever know that? - will never, not quite, be yours. It's the struggle and the process that means that I will know and understand Chinese in a different way, in my own way, in a slanted-to-reality sort of way, that is a treasure in and of itself. There is beauty in its brokenness too.

And there is sorrow, too. The sorrow that comes with easing yourself into a different life, and it holding you gently for a while. I sat there - I spoke to them. It's not only missing a place; it's missing a person you were, a stage of your life, for a time. It's knowing that a place has reached inside your ribs and taken root there - even if you don't return, you can never fully get rid of that again. You are two people now, with feet straddling two oceans. There are parts of you that loved and suffered and hated and grew in Chinese, not English. You can't explain that. You can't even begin. Sometimes - not often - you are a stranger in your own land. The poets spoke of that. In the age of fast travel, of the weekend break, we have forgotten the ways a place can burrow itself inside you, and find its own home.

It's not the same as the grief that someone Chinese will face. But it's still grief. I have put my life into Chinese. Maybe that is all it takes to grow love.

Now, I turn back to Chinese - as a foreigner, as Melissa, as myself. It's a bittersweet thing. I know that I cannot hold all of it. It will spill out, like the sun, and there is no way I can be that without losing myself and my history and my own green woods. But I think I am ready now. I am surer, and a little steadier on my feet.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

i hate when i send someone a meme in another language and they're like "uhm... translate? 😒" fucker i sent you a meme where 90% of the words have an english cognate and/or you don't need to know what they're saying to find it funny. can you at least TRY

63K notes

·

View notes

Text

When people get a little too gung-ho about-

wait. cancel post. gung-ho cannot be English. where did that phrase come from? China?

ok, yes. gōnghé, which is…an abbreviation for “industrial cooperative”? Like it was just a term for a worker-run organization? A specific U.S. marine stationed in China interpreted it as a motivational slogan about teamwork, and as a commander he got his whole battalion using it, and other U.S. marines found those guys so exhausting that it migrated into English slang with the meaning “overly enthusiastic”.

That’s…wild. What was I talking about?

28K notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you elaborate on the ways that the linguistics fiels may be racist? I'm white (as white as a mixed kid can be) and started uni recently, I'd like to be aware of the racist things in linguistics to better identify and unlearn them.

I'm already aware of the whole racist and classist judgment of certain language variations, but I wonder if there is more to it than I'm aware of, maybe more subtle things I couldn't pick up (if you could point out some sources, too, I'd be thankful).

again, i recommend decolonizing linguistics (that link is to the open-access pdf). the introduction is a good, well, introduction! you can also check out relevant topics from the podcast vocal fries, and the book antisocial language teaching focuses on ELT. this is just a smattering of the available material—scholars cited in those works have entire bodies of research out there.

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

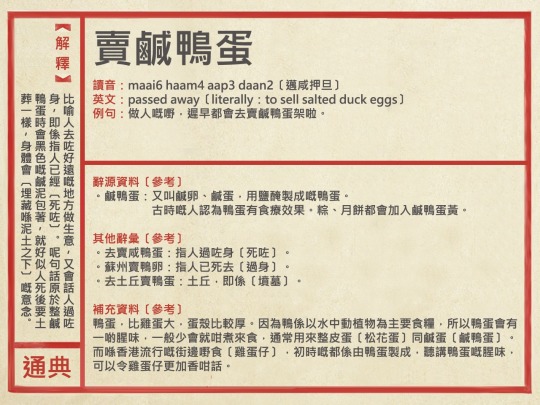

(到蘇州)賣鹹鴨蛋

🇭🇰🇲🇴 (dou³ Sou¹ Zau¹) maai⁶ haam⁴ aap³ daan²

🀄 (ㄉㄠˋ ㄙㄨ ㄓㄡ) ㄇㄞˋ ㄒㄧㄢˊ ㄧㄚ ㄉㄢˋ

🀄 (dào Sū Zhōu) mài xián yā dàn

Literal meaning: Heading to Suzhou to sell salted duck eggs.

Meaning: Euphemism for saying someone has passed away.

The full saying is 「到蘇州賣鹹鴨蛋」 but in practical use, people usually omit the 「到蘇州」 (sometimes even the 「鹹」) part.

Saw this post by @malaidarling and it occurred to me that while I'd heard, and know the meaning of the expression, I'd never thought about its origins before…so I decided to look more into it and found three possible explanations. ↓

來源解說 (origins explained)

1. Part of the Minnan custom, not sure if it's still practiced but, Minnan people in the past apparently bury their dead along with a small rock and a salted duck egg.

The idea was when it came time to say final goodbyes, living relatives will tell the deceased that “they will meet again when the rock has turned to ash and a duckling has hatched from the egg”, indirectly meaning the deceased should put all cares aside and leave the world in peace. Because rationally, the rock will not turn to ash for eons, and a duckling will not hatch from a cooked and preserved egg.

So there's this further idea that the dead will be “selling their eggs in the Underworld”, hence, “selling salted duck eggs” = dead.

2. Still part of the Minnan custom, after prayers at their ancestors' graves, some Minnan descendants will scatter duck egg shells on the grave mounds. Why? Not known (but it probably has a little to do with explanation No. 1 ↑ — like a symbolic gesture of reunification? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯).

Anyway, the act of doing this is known as 「土丘剝鴨蛋」, literally meaning, “Peeling duck eggs on a mound”. And the words for 「土丘」 (mound) and 「剝」 (peel) in the Minnan dialect, sound like the words for 「蘇州」 (Suzhou) and 「賣」 (sell) in Standard Mandarin.

3. A (rather funny!) story from supposedly the Qing Dynasty period, of a young man from Taiwan who told his mother he was heading to Suzhou to start a (salted) duck eggs business.

But this (unfilial! 😹) young man instead wound up marrying a rich girl and even changed his surname to marry into her family. So his mother back in Taiwan (after not hearing any news from her son for a long time) tried to look for him through a spirit medium at a temple.

The medium (depending if you believe in the powers of a medium or not) “could not locate” this son because he had changed his surname, so he told the mother, 「世間已無某某人」 — “this world no longer has this person”, leading his mother to believe he had died in Suzhou! Henceforth, to “head to Suzhou to sell (salted) duck eggs” became associated with someone passing away.

n.b.: Suzhou and Yangzhou were known for producing large quantities of preserved foods in the past (according to Wiki).

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

oh wait language learners i've found the perfect app!!!!

it's called Koo! it's liike a twitter spin off where you can filter the entire global feed by language and country! this is perfect for immersion and a feature every single social media should have. alas it's like not used by anyone which made me so sad to realize bc if we get koo to become to next big social media it wld be amazing just for this one feature! anyways open to suggestions for other apps websites you know that have this feature please!!!

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

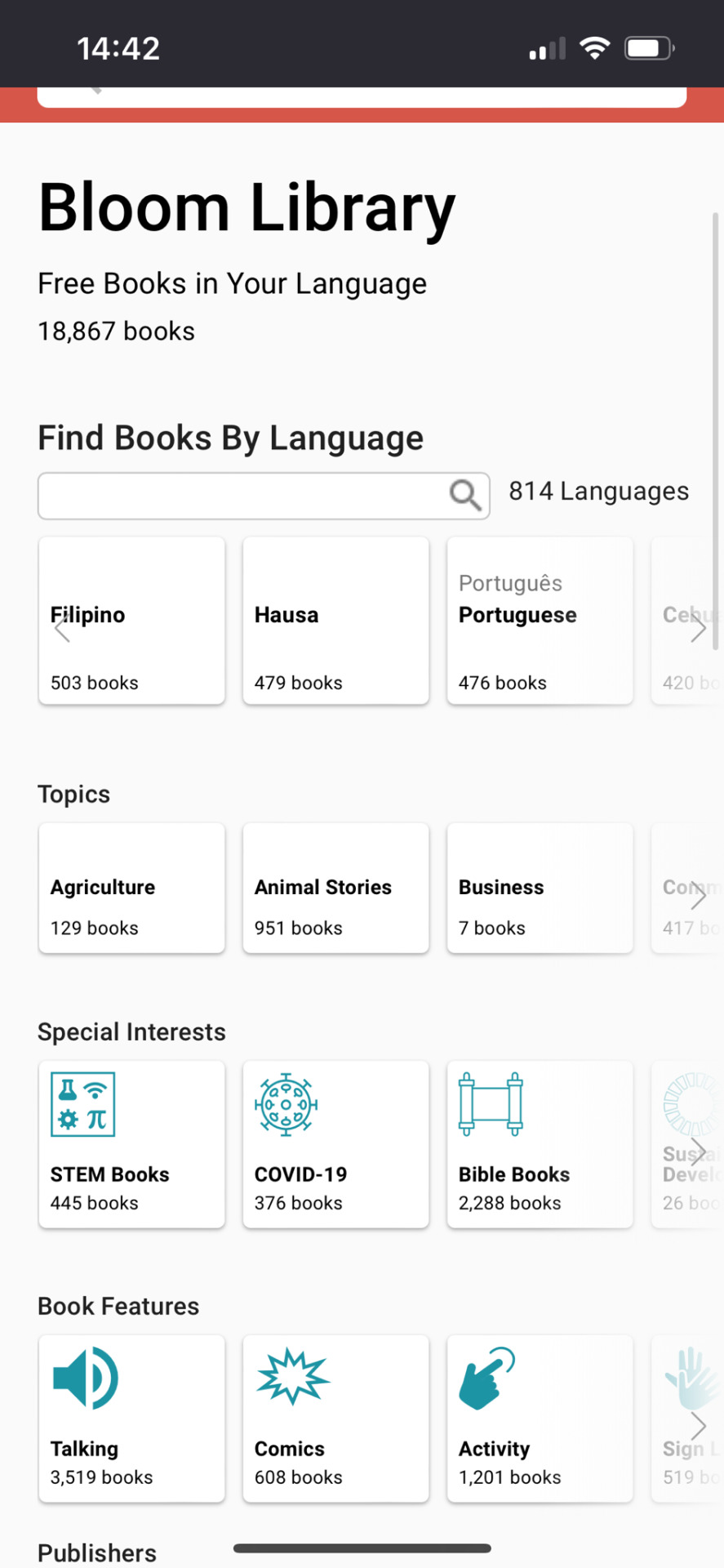

my friend and i were going to study a language together and wound up having to cancel our plans due to scheduling pressures, but! through research we came across a really cool resource for reading in a TON of languages: bloom library!

as you can see, it has a lot of books for languages that are usually a bit harder to find materials for—we were going to use it for kyrgyz, for example, which has over 1000 books, which was really hard to find textbook materials for otherwise. as you can see it also has books with audio options, which would be really useful for pronunciation checking. as far as i can tell, everything on the site is free as well.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

24.4.24 //

so my chinese class is collectively writing a story...

don't ask me what's happening. i made the narrator turn into a melon. this one kid in my class keeps trying to get people to turn it into a transmigration story, but now the narrator is a melon.

also, i learned the idiom 到苏州卖鸭蛋 dào sūzhōu mài yādàn - going to suzhou to sell duck eggs, which basically means someone passed away. i compared it to people telling their kids their dog ran away to a flower farm or went over a rainbow bridge, and it's not exactly the same, but my teacher thought it was pretty interesting nonetheless.

i'm not 100% sure but i think it basically means that trying to sell duck eggs is a futile effort in suzhou, and saying someone went there to do this impossible task just means they're never coming back. i could be totally wrong though.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

22.4.24 //

here’s a random list of words i learned today through reading 月宫里的嫦娥 with a tutor — will perhaps make a better post about it later.

渐渐地 - jiàn jiàn de - gradually, little by little

偷偷地 - tōu tōu de - stealthily, secretly

趁 - chèn - take advantage of

后悔 -hòu huǐ - to regret

呆 - dāi - stay

望 - wàng - stare, gaze into the distance

轻 - qīng - light (as opposed to heavy)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

did you hear there’s a new short film that is GAY?? LESBIAN, even???

AND it’s filmed in a minority language?? a CELTIC language, one might say??

AND that it’s available for FREE, with SUBTITLES in both irish AND english??

“FAN” (2024) dir. by cúnla ní bhraonáin morris

watch here 🫶

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I am by nature a boy, not a girl"

Xiaodouzi/Cheng Dieyi - Farewell My Concubine (1993)

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

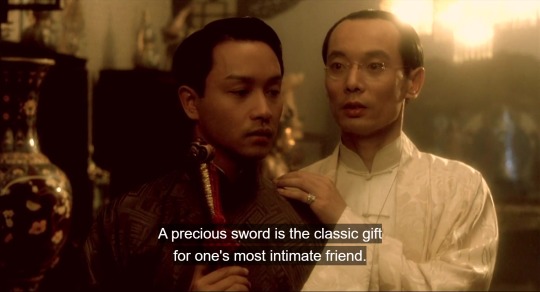

I'm watching "Farewell my concubine" and I think I've recognized the word zhī jǐ, of The Untamed fame (among non-mandarin speakers at least), in this character's speech. Here it is translated as "most intimate friend", which reminds me of the many posts that people have made over the years about CQL subs and how best to translate this word to English. Many of them (rightly) made reference to classic texts, but I didn't see any reference to other contemporary-era translations like this one.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think it would be very cyberpunk if English speakers adopted the words lakh and crore from India, because we need more names for large numbers. You can't just start using other people's words like that though, white baby.

830 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 然's

突然,虽然,忽然. and the other 然's can often get mixed up, so here's a quick explanation of some of the most common ones!

突然 (Túrán): This means suddenly or unexpectedly

居然 (Jūrán): This kind of means suddenly, but more in the sense of "surprisingly" or to suggest disbelief at something that happened.

忽然 (Hūrán): This also means suddenly or unexpectedly, but it has a more stronger connotation.

既然 (Jìrán): This is a conjunction meaning "since" or "now that"

既然the weather is great, let's go out!

既然 you aren't busy, let's go watch a movie.

不然 (Bùrán): This means "otherwise" or "or else";

You should study, 不然 you won't do well on the exam.

虽然 (Suīrán): This means although or even though.

虽然 I'm not good at singing, I still like to go to the karaoke.

当然 (Dāngrán): 当然 means certainly or definitely and can be used as a reply:

Can you help me with A? 当然!

自然 (Zìrán): This can mean nature or naturally.

China's 自然 is very beautiful.

She speaks Chinese 得很自然.

仍然 (Réngrán): This can mean "still" or "yet".

I仍然 haven't read that book.

依然 (Yīrán): Similar to 仍然, this also means still" or "yet" but it's usually used in more formal and literary works, whereas 仍然 is more often used in spoken language.

果然 (Guǒrán): 果然 can be used to mean "indeed" or "as expected"

This movie is 果然 interesting.

竟然 (Jìngrán): This is an adverb used to suggest surprise or something unexpected.

He竟然forgot her birthday.

显然 (Xiǎnrán): This means "clearly" or "obviously".

This soup 显然 hot.

偶然 (Ǒurán): This means "accidentally" or "by chance".

We 偶然 met at the same cafe.

How many other 然's do you know about? Drop a comment!

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

10.4.24 // 祈祷明年我能有住房🫢🫢

大家,我忙死了。还没有住在的地方,我跟我室友太紧张了。。。

而且我还没找到我的飞机票去爱尔兰因为我朋友还没准备好。

我的中文课也太难了。我的同学都来自中国💀 但是,我认为我的中文越来越好了:)

#diaries#chinese#langblr#this student housing crisis is killing me :)) fighting for my life out there smh

5 notes

·

View notes