Text

arthur morgan would love grunge music. particularly alice in chains and stone temple pilots. he just would idc

#arthur morgan#and maybe i’m projecting onto him#but also i think im just right#rdr2#rdr2 arthur#idk

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

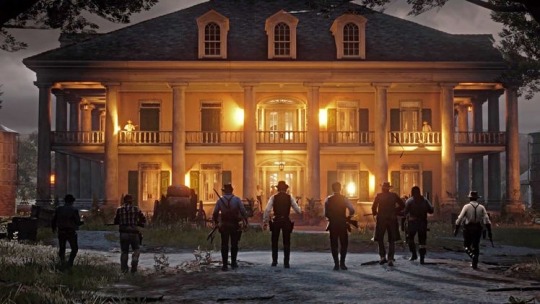

Cherry Waves

hey guys here is my fic

Summary: Long play off of Harvest Moon (and another bit I should probably write at some point) that takes place during Chapter Six. F!reader wants Arthur to leave the gang, but he feels a sense of obligation to his family, so he wants to stay.

Warnings: Majorly canon-compliant, could have been shorter, cussing????

Word Count: 13k

'He thinks we’re a lost cause, you thought. He thinks we’re not gonna get out in time. Deciding not to press it, for fear of getting a response you didn’t want to hear, you nestled your head into Arthur’s chest. “Goodnight.”

Arthur kissed your head, saying, “Mmm, goodnight.”

He knew you knew.'

In the swamp, you found that a shift had occurred in yours and Arthur’s relationship. He was more distant, spending more time away from camp. He’d come back exhausted and bloodied, often crawling straight into bed without a word. When you asked why, he’d give you the same answer: ”well, somebody’s gotta do the work”. You’d noticed a new weakness in his muscles, a hollowing of his face. He’d acquired a cough, too, and sometimes you’d wake up to him hacking in his sleep. He blamed it on the weather, saying that he was just getting used to being back in America.

It was no surprise when, after a day out with Sadie, he came and told you that he was sick. “What is it?” you asked, looking up at him from your shared cot. He stood, hands on his hips, in the corner of your rickety room.

“Tuberculosis,” he said, wiping his face with his hand. “I ain’t got much longer.”

“Okay,” you said after a while, staring at his worn boots and swallowing hard. “What are you gonna do?”

“I dunno,” he admitted, looking past you. “I can’t just die though.”

“No,” you agreed. “We could head West and get you some good air, maybe? Colorado?”

“They know us there; we won’t be able to hide out.”

“Not if we stay in the mountains. Hell, you could stay in a sanatorium and I could-”

“I ain’t goin’ to a sanatorium.” Arthur put his hat on the small table next to your cot and took a seat. He shook his head. “That won’t work.”

“So what will? We can’t stay in the swamp.”

“Dutch wants me and Charles to go find us a new camp anyway–somewhere North of here–so it’ll be better.” Arthur took a deep breath, wheezing.

“I suppose,” you said, taking his hand. “It’ll be okay.”

“Sure,” he said, grim.

*****

The new camp was bleak. Everyone was on edge with each other, and poor Molly had been killed–bless her soul–for none other than loving Dutch. She’d never taken to the rest of the group, becoming a bit of scapegoat, but you had tried a couple of times to know her. You figured her death was more of a reason to get away from the gang you had loved so much; you weren’t sure how much longer you guys would have together. In your almost 6 years with everyone, you’d never seen someone from the gang killed in camp until now. You felt bad.

The whole deal felt bad. Seeing Micah and his new “friends” filled you with an anger you couldn’t describe. Seeing Dutch pull away from the rest of you, abandoning the gang that he had created was infuriating. Watching your husband the workhorse go and do everyone’s bidding while he was dying made you feel the worst, though. His plan, you had learned, was to change nothing. He’d just keep chugging along, doing the same as before, despite the obvious restrictions his body was trying to put on him. He’d thinned considerably, attempting to hide this with vests and jackets, but you noticed how his shirts hung from his shoulders. You noticed the circles around his gray eyes, which used to glow green and blue and gold.

You nagged at him constantly–about eating, getting away from the gang, resting when he needed to–but he never listened to you, always dismissing it with yes, dears and we’ll sees. You hated it. You hated that the two of you were stuck in this mess. Arthur needed to get away from this! He was dying. You guys had a limited time together, now more so than before, and you didn’t want to give any of it up, but he was just throwing it all away. To keep your mind off of this, you spent your time split between Abigail’s tent and your own, either talking to her or reading (you found reading to be the perfect escape). In doing this, in keeping to yourself and avoiding the war that tore down the only home you’d ever known, you found yourself resenting it all. You resented your husband for staying here and getting himself sick. You resented Dutch for leading all of you into this mess. You resented Miss Grimshaw for continuing to put you girls to work, despite her obvious knowledge that it was all going to shit. Most of all, though, you resented yourself for letting this happen to you. Yes, Arthur had dragged you to camp all those years ago, but you had chosen to stay. You chose to marry him, to love him in sickness and/or in health, and now you were face-to-face with the reality of that statement. To run away on him–to get the hell away from this disaster and go somewhere proper–would be a betrayal, and that was something you weren’t willing to do.

Arthur was away with Sadie–shooting some O’Driscolls, or so you’d heard–and you occupied your mind with a poetry book. Back against a big tree, you lazily gazed upon the words on the papers, hardly comprehending any of them. You couldn’t help but wonder if he’d even come back. If he’d get himself killed this time. You could picture it perfectly: Sadie would come riding back into camp, calling for you or Dutch or John or maybe all three of you. She’d tell you guys that something’s wrong–something with Arthur–and that he fell and couldn’t get back up and she wasn’t strong enough to get him herself. Dutch would send out battalions to fetch him (or at least the Old Dutch would, but that seemed to be an entirely different man, as of recent) and you’d sit and wait like you always did, just hoping to God that Arthur would come back home to you and cup your face and kiss your forehead like he always had. And he wouldn’t. John would tell you that Arthur was dead and you wouldn’t even cry. That was the worst part of these visions–you wouldn’t cry in any of them. You couldn’t bring yourself to shed a single tear, not even in your imagination. No tears for a man who did it to himself.

The truth is that you felt, in the deepest part of your psyche, that things would be easier if Arthur would just die. If he died, you could breathe again, even if only for a little while. You knew your husband; you knew he’d never leave. And you would never leave him because he’d been there for you for everything. He was there when your mother wrote, asking for help. He was there when you pretended to hate him and instead of being angry at you for it, he told you he loved you–the first person to say that–and danced with you all night long. He was there when you learned you were pregnant and he was there when the baby was born blue. He was there for everything, so you had to be there for him.

When Arthur did come back, you hadn’t even flipped the page. You were so lost in thought that you didn’t notice him striding toward you, quietly coughing into his fist. “Y/N,” he said, catching your attention. “Hey.”

“Hey, Arthur,” you said back, not looking at him. You felt bad for what you’d been thinking about–thinking about how it would be if he was dead–but you couldn’t help but ponder these things. It was a very real possibility that he would leave and never come back. You used to go with him on these things, that way you never had to sit and worry–besides, you knew your way around a weapon–but since you learned you were going to be a mother, you hadn’t picked up your rifle. It didn’t matter that your son hadn’t lived; you were trying to be a new woman. Less angry, less impulsive. Less like Arthur, you supposed. You weren’t the one flirting with death. You were caught up in their torrid love affair, waiting on your darling lover to come back home and realize he wanted you. The waiting killed you. The realization that it would be easier if you didn’t have to wait any longer on him–if it would just end then–killed you a little less.

“Whatchu readin’?” he asked, sinking down next to you. “Something far beyond my level, no doubt.”

“No, it’s just Dickinson,” you replied softly, resting your head on his shoulder.

“Read to me.”

Taking a shaky breath, you sat up and recited the poem on the page, saying, “‘There is a pain—so utter— / It swallows substance up— / Then covers the abyss with Trance— / So Memory can step / Around—across—upon it— / As one within a Swoon— / Goes safely—where an open eye— / Would drop Him—Bone by Bone.’”

“I don’t even know what that means,” Arthur said, chuckling a little. “But it sounds pretty, don’t it?”

“Yeah,” you whispered. You put your head back on Arthur’s shoulder, inhaling sharply. “I’m glad you didn’t get yourself killed.”

“Did you think I would?”

“Maybe. You know I’d prefer that you… minimize your excursions.” You folded the book shut and held it in your lap. “I don’t want whoever you’re out with to bring me back a damn corpse for a husband.”

“I ain’t gonna get killed-”

“You’re killing yourself right now, Arthur. Don’t be a fool,” you interrupted, sitting up. “This is killing you, and you know it as well as I.”

“Don’t talk about that here,” Arthur said, hushed. “We can discuss it later, okay?”

“Okay,” you said after a while. “Okay.”

“Let’s just sit here for a while, though,” Arthur said, grabbing your hand. “It’s rest, like you’ve been askin’ for.”

Electing not to argue, you leaned back into Arthur’s side. You had fought and fought for the past month, and it was nice to pretend for a soft, sweet moment that everything would be alright. That he wasn’t going to die. That you probably wouldn’t go with him, whether you wanted to or not. The dread had weighed on your chest since you’d heard his diagnosis–like a heavy man was sitting atop your ribcage–but you could ignore it when it was just the two of you like this. And then Arthur would cough or wheeze and the weight would be back.

*****

Days later, Arthur was supposed to blow up a bridge with John. Sitting in your tent with the canvas drawn, you said, “What’s the point of this anyway, Arthur? What’s this gonna do?”

“I dunno,” he admitted, standing next to his wardrobe, grabbing a black shirt. “But Dutch is convinced that the ‘noise’ that will come with it is gonna help us; I can’t see how.”

“You’re a fool if you do what he says for much longer. He’s not worth it anymore.” You grabbed your book–a new one, called Her Ladyship’s Elephant–and lay back on the cot. Arthur tucked his shirt into his pants, wheezing a little. Your stomach flipped.

“I know he ain’t, but…”

“But you’re too loyal to do anything about it; I know.” You opened the book to the page you were on, adding, “I’d just like to get to spend more time with you, you know. Away from all of this-”

“Y/N…”

“But you won’t leave; I know.”

Arthur put his hands on his hips, breathing shallowly and looking at his feet. “Now, I-”

“Don’t try pretendin’ otherwise. You know it. I just want to spend my last days with you someplace nice; not in this shithole.” You stood, walking over to your husband and linked your arms through his, wrapping yourself around his weakened torso. “I love you too much for that, okay?”

Arthur returned your embrace, saying, “Okay, darlin’... okay.”

You dug your chin into his chest, taking him in with all you could muster. He was dancing a dangerous line, teetering closer and closer to death every day. You wanted to remember every detail, every single sensation you felt as he held you in his arms which, even in their weakened state, were strong around your body. “For me?”

“For you,” Arthur agreed, pulling back and holding you at an elbow’s length. You pretended not to notice his hesitation in answering. “I’ll try my best to get us outta here.”

“That’s all I ask.”

He cupped your face, kissed your forehead, and said, “I gotta go now, okay? I’ll be back in an hour or so; no longer. Just gotta blow up this damn bridge and I’ll be back to you and we can work on findin’ a way out.”

“Okay.”

“I love you, darlin’.”

“I love you too. More than anything,” you answered, smiling softly. “I’ll see you soon, cowboy.” Arthur jokingly tipped his hat and exited the tent, leaving you with your book. You climbed back onto the cot, opened the book, and started reading, enveloping yourself in a world you could never escape to.

When Arthur got back, the two of you laid on the cot together. You read him passages from the book that you found interesting, and he listened, despite having no interest in a woman who had randomly acquired an elephant. At this stage, the two of you spent every possible moment together, clinging to the other’s company like it was the only thing preserving your sanity. Maybe it was. You never could tell when Arthur would meet his maker, so you felt every inclination to stay as close as you could to him; to hold on and never let go. When it got dark, you put up the book and turned to Arthur, asking, “Did you talk to John?”

“About what?”

“Don’t play dumb with me, Arthur; about leaving?”

Arthur glanced down at you, brow furrowed. “I told him that he needs to get the hell out of here before it’s too late, if that’s what you mean.”

“And what about us?”

“I’m not leaving until John is safe, Y/N. He’s got… more, if that makes sense. It’s not just him and Abigail; they got Jack, and the boy deserves a better life than this.”

You nodded, your stomach flipping again. He thinks we’re a lost cause, you thought. He thinks we’re not gonna get out in time. Deciding not to press it, for fear of getting a response you didn’t want to hear, you nestled your head into Arthur’s chest. “Goodnight.”

Arthur kissed your head, saying, “Mmm, goodnight.”

He knew you knew.

*****

The day had started like any other–Arthur would wake from his restless slumber and scramble out of bed, pulling his pants and boots on, kissing your forehead, and leaving without waking you–but you were unable to shake the uneasiness that hung over Camp like a wall cloud before a tornado. Dutch had disappeared into the cave and you could hear fragments of his conversation, though you couldn’t tell who he was speaking with. Perhaps it was himself, or it was another one of his “visions”, where he claimed that he could see Hosea. It wasn’t worth trying to figure out, at this point. Dutch was more than a loose cannon; he was a lit fuse. Everyone in Camp waited, air thick with anticipation, for Dutch’s inevitable explosion. You couldn’t blame Arthur for leaving so early.

“Hey, Y/N, would you mind talkin’ to Dutch for me?” Abigail said, startling you. You looked up from your journal, which you hadn’t written in for weeks, and snapped it shut. “I think I’m onto something, but I need you to, uh…”

“Get him out?”

“Yes, if you would.” Abigail smiled sheepishly. “You don’t have to–I don’t blame you if you don’t want to–but I think I found somethin’ good.” Leaning in, Abigail whispered, “I think he’s hidin’ our money in there.”

You raised your eyebrows. “I can try, Abigail, but you know he’s not doin’ well. He knows as good as you how I feel about this place…”

“I won’t be long; promise.”

“I guess you have yourself a deal, then,” You said, standing.

“Maybe, if you’re lucky, he’ll kick you out of Camp. That’d force Arthur to listen to you,” Abigail said, stepping off toward the cave.

“Or I’d end up like Molly…” You responded, too quiet to hear.

You glanced around Camp as you made your way to the cave, taking note of Javier and Bill’s strange alliance. It had always been your impression that they hated each other–it seemed that Bill hated Javier for being Mexican and Javier hated Bill for hating Mexicans–but now the two of them found middle ground in their fiercely blind loyalty to Dutch. Arthur was loyal like a dog, but even a dog learns to stay away from the owner that abuses them for so long. It puzzled you, their loyalty. You wondered how bad things had to have been for them to think that this–the constant badgering about faith and money and scores while running faster and further than you’ve ever had to run before–was better than what they would have faced. Did they really still believe that this was freedom? If you could still bring yourself to write, you figured, you’d write about that.

As you approached the cave’s entrance, Abigail split off to the right, waiting in the corner behind Dutch’s tent, safely tucked out of sight. “Dutch?” you asked, voice echoing on the cave’s moist walls. “Are you in here?”

“Mrs. Morgan!” Dutch boomed, appearing from one of the many tunnels. “How are you?”

“Well, I’m… I’m not well, Dutch. Do you have a moment to talk about Arthur?” You asked, craning your neck and frowning slightly. “He’s in a bad way.”

“Of course!” Dutch put his hand on the small of your back, guiding you to his tent. “We can always talk about Arthur and his issues with Old Dutch.”

“Oh, he doesn’t have issues with you,” you lied, “but I’m sure you’ve noticed that he’s not doin’ too well.” The two of you stepped into the tent, with Dutch motioning for you to take a seat in the wooden chair across from his cot. He settled into a chair of his own. Abigail scurried into the cave without catching anyone’s attention but your own.

“This is about that? My dear, Arthur is fine. Hosea was sick for years and that wasn’t what took him out. It’ll pass–all things do. This, this will pass. I know things are hard for you right now, it’s hard for everyone, but I promise you that I will get us out. We’ve got a train job planned and that will be it, Mrs. Morgan. Just one more score and you don’t have anything to worry about. We will hop on a riverboat and head to Chicago or New York and then head off for the tropics. I have a plan. You just need to have some faith.”

“Dutch, he has tuberculosis.” You said bluntly. “He doesn’t have much time left. I’m not asking for a grandiose speech to inspire me, I’m just asking that you help him out a little. He’s sick. I know that you love him–I love him–and I’m afraid that you’re working him to death.”

“I’m doing no such thing!” Dutch said, raising his voice slightly. “It’s all apart of the plan.”

“And what is that plan?”

“I told you: Tahiti. One last score, and we can get there.”

“You’ve been saying that for as long as I’ve known you; how do I know that this is the real one?”

“Have some goddamn faith in me.” Dutch fired back, a scowl painting itself on his face.

“Why should I?” You challenged, leaning forward. “Where did faith get Sean and Lenny? Hosea?”

“Don’t talk about Hosea-”

“Hosea would be so disappointed in you.”

“Don’t talk about Hosea!” Dutch repeated, glowering.

“Why? You don’t want to think about what he’d say? I’ll tell you what he’d say; he’d-”

Before you could finish, Dutch was in your face screaming, “I have a plan! You do not get to tell me anything. I am sick of your incessant complaining! You know nothing of Hosea, and you know nothing of this situation!”

You raised an eyebrow, holding your mouth agape. The tension between the two of you was palpable; the hatred radiating off of his body was overwhelming, but you held his stare. For a moment, you didn’t know what to say. Arguing had always come easy enough for you–sometimes your timing was a little off or you didn’t emphasize the right words–but you rarely found yourself at a loss of words. When you did find the right words, though, you knew they’d hit. “I see straight through you, Dutch van der Linde. It’s a shame that no one else does.” Carefully, reeling from the encounter, you stood and excused yourself back to your tent, hoping that Abigail had made her exit from the cave in enough time.

Upon exiting Dutch’s tent, you found that everyone was watching you, aside from Karen, who was passed out by a tree, and Jack, who was playing quietly in the dirt. Javier gave you a nasty look and muttered something to Bill, who smiled. “Gentlemen,” you quietly uttered, scurrying past them.

“You know, Arthur can’t protect you forever,” Javier called after you. You kept your head down, closing the flaps of your tent. You hadn’t intended to cause a scene, but you were having an increased difficulty in holding your tongue in times like these. Maybe you were just tired of always doing what you were told. You couldn’t tell.

It was no secret that you were unhappy. You had your moments, sure, but you hadn’t been content since you lost your baby. Samuel, your son, was supposed to make things better. He would’ve given you a life away from all this. Sometimes you’d lay awake at night and see his tiny, wrinkled face. His face that never crunched up and cried. And just like every image you’d conjured of Arthur’s death, you could not cry at the death of your son. You could not cry at anything. You could only observe, watching and silently simmering at the injustice that had been committed against you. Your life, you felt, was an injustice. You could’ve been good, somehow, and you never were. It was easy to blame the circumstances–it was easy to say that this was Dutch’s or Arthur’s or Samuel’s or society’s fault–but you knew it was no one’s but your own. You were bitter and devoid of anything positive. You’d fought against living your whole life and now here you were, a shell of a person with nothing to come from an empty existence. When you died, there would be no one left to remember you by.

You climbed onto your cot and grabbed the journal from your nightstand, opening to an empty page. You had nothing to write. You wanted to write something, you wanted this desperately, but you couldn’t find the words to adequately express your emotions. You were stuck. You began scribbling the word stuck over and over and over again, handwriting growing larger as you went on. You were stuck. You could not leave but you could not stay. You could not go to sleep but you could not stay awake. You could not fully love Arthur but you could not hate him. Stuck.

You were interrupted by the front curtain flap opening. Quickly, you slammed your journal shut as Arthur strode into your tent. “I been thinkin’”, he said.

“Does it pay well?” you responded, too quiet, in a daze.

“Funny,” Arthur fired back. “Anyway, I was thinkin’ and you know how we need to get John and Abigail and Jack outta here, right? All of the girls, too?”

“Yeah…”

“I got a plan for it; I have to run it by John, but we’ll… what’s wrong?” Your husband took a seat at the edge of the cot, looking at you with a furrowed brow.

“I talked with Dutch.”

“Why’d you do that?” Arthur leaned back, taking your hand. “It wasn’t good, no?”

You chuckled slightly. “Of course it wasn’t. I was tryin’ to help out Abigail but instead made it all about myself; she must think I’m terribly selfish.”

“You live with criminals of the highest offense and you’re worried about bein’ selfish?” Arthur teased. “She seemed fine; don’t worry about it.”

“Wait, you saw her?” you leaned forward, turning toward Arthur.

“Well, yeah. She was gettin’ onto Jack about runnin’ away or somethin’. It was pretty loud; I’m surprised you didn’t hear it.” He said it like it was obvious. You sighed.

“That’s good.” You leaned into Arthur’s side, resting your head on his chest. “I missed you today.”

“I missed you too, darlin’,” he said back, but you were sure that he didn’t miss you the way you’d missed him. He put his arm over your torso, holding you comfortably.

“You’re so warm.” A soft smile crept across your face and you wiggled closer to your husband. “What’d you do today?”

“Well, I went fishin’ with a Civil War veteran named Hamish and taught a young widow how to shoot. Then I went into Annesburg for a drink and ran into Archie Downes–Mr. Downes’s son–and learned that him and his Mama never left like I told them to, so I went an’ fetched his mother and gave ‘em more money. It’s the least I can do.”

You nodded. “I got screamed at by Dutch and maybe threatened by Javier.”

Arthur chuckled. “A day in the life.”

Smiling, you responded, “No doubt.”

*****

In the week that followed, you watched and waited as Arthur followed Dutch around, doing whatever he asked. You quietly simmered, doing your chores and reading without a word to anyone. How could Arthur go and obey Dutch’s every word, execute his every whim, and not try to get you guys out? Did he not value you? The relationship the two of you had carefully fostered for the past 5 years? Maintaining a relationship with Arthur was like trying to fight the government; you were always losing. You’d fought the government for the greater portion of two decades, and you never won. The same was true with Arthur–you never won. At the end of the day, you might be in his bed, but his mind was occupied by Dutch Van Der Linde and his fancy words. You knew when you fell in love 5 years ago that you’d never be the sole occupant of Arthur’s heart, but it was worse now, knowing that Dutch didn’t care for Arthur anymore, or at least not in the way he had. For him now, Arthur was a weapon, and it simultaneously broke your heart and filled it with rage.

Was Arthur this oblivious or had he just allowed it to happen?

You figured it was the latter. You were tired of it. When Arthur returned from the oil fields–Dutch’s latest escapade, with the intent of sticking it to the Army–it was late and you were looking for a fight. You’d quietly stepped aside all week, but you were done. You were sick of this, of giving Arthur everything and getting nothing in return.

“You’re late,” you said, standing with your hands on your hips.

“It was a goddamn mess; I need to sleep.” Arthur sat at the edge of the cot, yanking his boots off of his feet.

You scoffed, eyebrows raised. “That’s it?”

“Yes. I don’t want to talk about it right now, Y/N, please. It was awful.” He stood and removed his gun belt and pants, tucking them neatly into his wardrobe.

“It’s almost like I told you it would be bad–that all of this would be bad. How long have I been trying to get you to leave this life? A year? I thought that getting sick would give you some sort of clarity–that you’d decide that this is what matters–and you’d finally choose me, but you’ve done the opposite! You’re leaving more, and you come back looking worse and worse every time… When are you gonna come back in a casket, Arthur Morgan?” You spat, voice hushed. You were surprised that Arthur hadn’t interjected to defend himself.

“Not now.”

“Now,” you said, remaining firm. “I waited for you. Everyone got back here way before you did; why?”

“Because I got a goddamn boy killed, okay?!” Arthur fired back, looking up at you. “I… I don’t know exactly how it happened, but we was leaving the building and I slipped and he saved me, but… not before it was too late. He was shot in the belly for savin’ me.”

You were quiet at that. “Oh,” you said, softening.

“Dutch… he left me. He could’ve turned around and helped me, but he didn’t and got that poor boy–Eagle Flies–killed for it.” He paused before quietly adding, “Charles and I brought him back to his pa before he died; that’s what took me so long.”

“I’m sorry,” you said, trying to meet his eyes.

“I know you are,” Arthur answered, staring straight ahead. Then, almost out of nowhere, he began coughing, his body quaking. He stooped over, hands on his knees, hacking up blood, desperately gasping for air in between each croup. You were at his side immediately, softly rubbing circles on his shoulder. The pit in your stomach seemed to reach your feet. You couldn’t help but feel selfish for all of this–for throwing a fit when a boy got killed–and now Arthur was hurting again and you couldn’t do anything to help him.

As he continued to choke on his own air, you guided his shoulders down, laying him flat on the cot. “Shh, it’s okay,” you whispered. “I’m sorry, Arthur.”

Tears brimmed your eyes as you watched your husband slip into unconsciousness. You couldn’t fall asleep for a while–not until the sun was beginning to rise–and when you did, it was filled with the same bad dream, playing over and over in your mind. You were stranded in a county jail when Arthur–young, healthy Arthur–came bursting in to bust you out. Guns brandished, he told them that he wouldn’t hesitate to shoot first and think second, something he used to threaten people with often. Every time, the deputies elected to shoot him. You watched Arthur die again and again and again, shot down by some scrawny teenagers with guns who shot for the sake of shooting, and there was nothing you could do. He crumpled to the ground, crawling toward you, saying your name–a plea of sorts, begging you to help him. Just as he’d get to you, finally gripping the cuff of your worn-out jeans, you’d wake up. You’d wake up in his arms, letting the sound of his slow, steady breath ease you back into your fitful slumber.

You slipped out of bed before he’d begun to stir, grabbing some coffee for the both of you. When you came back, Arthur was sitting on the cot, legs hanging over the edge. “Just the two of us today,” he said, taking the cup from you. “Thanks.”

“You’re welcome.” You took a seat next to him. “You takin’ me somewhere?”

“I was thinkin’ we’d go to Valentine or Strawberry–get you a book or something and rent a Hotel room.” He took a sip of the coffee.

“Careful, it’s-”

“Damn, that’s hot!” he said, yanking the cup away from his mouth. The two of you shared a sideways glance and burst out laughing.

“I tried to warn you!” You said, setting your drink on the nightstand. “I just poured it!”

A smile spread its way across Arthur’s face, but it faded as his laughs were replaced with coughs. Right, you reminded yourself. We can’t laugh anymore. You took a sip of your coffee, cheeks flushed. It was embarrassing to watch him like this. You felt bad–the constant stomachache you had was a way of always remembering–but you felt embarrassed for seeing Arthur, a man used to being strong, in such a pitiful state. It felt like you were looking down on him somehow.

“I’m okay,” he mustered, still coughing. “It’s… it’s okay.”

“Mhm,” you hummed, staring at the ground before you. “I think we should camp out in Big Valley. It’s so beautiful over there.”

The coughing ceased and Arthur nodded, wiping blood from the corners of his mouth. “Sure.”

“We could go fishing and then stay the night in Strawberry–I think a bed will help you, you know–and maybe we could get a portrait done… Well, I don’t know, there’s no portrait places around, but I think it would be nice,” you rambled, turning back to your husband.

“Yeah, that would be-”

“Arthur!” Dutch called, side-stepping into your tent. He shot you a dirty look. He hadn’t been very welcoming since your encounter in his tent. “I thought I heard you. At least you ain’t run off like the rest of them.”

“Whatchu mean?” Arthur asked, leaning forward.

“Pearson, Old Uncle–the traitors–both gone at dawn. They said to young Tilly they were runnin’ to save themselves. I think Mary-Beth left as well.”

“So it goes,” Arthur muttered, shaking his head. So it did. If it were up to you, you and Arthur would have been gone with them. Of course, it wasn’t, so here you sat, next to your husband and the man he loved more than anything. You slipped your arm around his, a subtle and unconscious showing of possession.

“They are goddamn cowards, Arthur. Cowards. Of all the time we spent, to run off…”

Standing, Arthur interrupted, saying, “Well I guess they don’t wanna die, Dutch.” Your arm fell to your side.

“Ain’t nobody gonna…” Dutch grabbed Arthur by the shoulder and led him out of the tent, leaving you to yourself. You made it your business not to listen, out of respect for Arthur’s privacy, more than anything, and perhaps as a sort of guilt for the way you’d carried on the night before.

You could hear bits of the conversation. You heard Arthur loudly exclaim something about there always being a train, before coughing. You heard Dutch saying something about insisting–and from his tone he was not happy–before Arthur came barging back into the tent, saying, “Get ready. We gotta go rob this damn train and we need all the guns we can get.”

“Arthur, I ain’t been on a job since-”

“I know, Y/N, but I’d feel better if you were with me than if you were waitin’ back here. Miss Grimshaw, Tilly, and Abigail can handle the packing just fine without you; I need you with me, okay?”

You nodded. “Okay.” You quietly stood and made your way to the weapon cabinet, digging your engraved Bolt Action out from the bottom. Arthur stepped out, quietly talking with John about the train job. You then dressed yourself in a purple checkered shirt and navy jeans, topping off the outfit with a black hat. You clipped your gun belt into place, carefully tucking your volcanic pistol into its holster. Arthur had his own matching set, engraved with his initials. You hadn’t carried your weapons in almost a year in an attempt to get straight, but if Arthur said now was the time to dig them back out, you believed him. And, admittedly, you had missed the rush you felt behind a powerful weapon.

When you stepped out of the tent, Arthur smiled a little. “Hey,” he said.

“Let’s get this over with,” you responded, walking past him. Dutch stood at the center of the camp, rallying the troops in some way or another. “Let’s ride out, gentleman,” Dutch shouted, arms raised. Everyone muttered their agreements, climbing onto their mounts, as Dutch repeated himself, saying, “Let’s go!”

The group of you took off, heading South for what would either be your ticket out of hell or your ticket straight to it. You stayed close to Arthur’s side, for fear of harassment by Micah or his lackeys, and did your best to keep the growing uneasiness in your stomach at bay. Arthur had respected your wishes to stay out of the fight for almost a year–since Micah had joined the gang–and now he was asking you throw yourself back into it. You wondered if it meant Arthur was worried–if he thought that it was going to be so bad that he needed you to be there. You swallowed hard, paying attention to the road in front of you.

“Okay, let’s pick up the pace,” Dutch called, “The train is due in Saint Denis in an hour.”

“We’re robbin’ a train in the middle of a city?” Arthur asked.

“No,” Dutch clarified. “It’s going to stop there, take on mail and water, let off some boys headin’ home on leave, and then it heads out.”

“They know the bridge is gone, Black Lung,” Micah taunted, inching closer to the two of you. “There’ll be a patrol past Annesburg, waitin’ down by the river to collect the money.”

“Shut up, Micah,” you whispered.

Simultaneously, Dutch said, “We sneak on quietly and then we get a short time to stop the train–before it reaches the patrol.” The bunch of you continued forward before Dutch said, “John, you go get that dynamite. We’ll meet back up outside of Saint Denis.”

“Y/N and I will go with him,” Arthur added, motioning at you with his hand.

“As you wish,” Dutch said back.

The three of you broke off from the group, heading westward to wherever John had planted the leftover dynamite he and Arthur had used to blow up the bridge. “It’s this way,” John instructed, leading the pack. “It’s nice to see you back with the gang, Y/N,” he added.

“I asked her to come with,” said Arthur. “It might be a shitshow–trains always are–and I wanted some extra insurance.”

“Yeah, I’m not sure how all this will play out.”

“This is one big goddamn group to be riding back into Saint Denis,” Arthur admitted, getting side-by-side with John.

“Yeah, and I heard the Pinkertons have pretty much taken over Van Horn,” John responded. You nodded, as if either of them could see you. “They moved a whole heap of men in there. Things are closin’ in fast.”

“Shit,” Arthur softly exclaimed.

John led you and Arthur the rest of the way to the wagon, and despite yours and John’s protests, Arthur insisted upon getting the dynamite himself. You rolled your eyes. He didn’t need to be carrying a 30-pound crate anymore.

“You know we can get that, Arthur,” you reminded him, leaning forward on Waldo, your horse. A red chestnut Arabian, Waldo had been your horse for nearly as long as you’d been with the gang–you and Arthur found him shortly after you’d fallen in with them.

“I’m fine,” he called back, a hint of aggression in his voice.

“As you like.” You patted Waldo and gave him a sugar cube. “You’re a good horse, boy.”

Arthur tucked the dynamite into his satchel and mounted back up. “So listen,” John said, “Abigail just told me… the money… it’s hidden in the caves at Beaver Hollow.”

“What the hell is it doin’ that close to camp?” You exclaimed, falling into step next to John and Arthur.

“I know! Dutch is gettin’ even sloppier than we thought!” John said back.

“Are Abigail and Jack ready to leave?” Arthur asked.

“I think so,” John responded, an uneasiness in his voice.

“Okay… Whatever happens with this job today…” Arthur began coughing, still saying, “wherever Dutch and them go next, we’re getting you the hell outta here. We’re gonna get you the money you need. Knowin’ the three of you got out, well… Maybe all this’ll still mean somethin’... Tilly and Susan too. I’ll do whatever it takes.”

You hoped that included you.

He wouldn’t say it then, whatever plan he had for getting you guys out of there, and you knew that–it was a conversation for you two to have in private–and despite knowing the end was coming, you hadn’t anticipated its arrival to be this soon. But part of you wished that he would have mentioned you–his wife, the woman who had stood by his side for nigh on 6 years now–because it would have meant that he believed that you were something he was fighting for.

You’d talk about it later, if you could, and you’d apologize for making an ass of yourself the night before. These weren’t things to be discussing with John around; he didn’t need to be aware of your guys’s relationship issues, especially when he was having his own. “You’ve always had my back, Arthur,” John said.

“Well, perhaps not always,” Arthur corrected, and you smiled, remembering how angry he’d been when John left.

“Anyway, here we go… One last train, guys.” John pushed forward.

“One last train…” Arthur repeated. Your stomach flipped. One last train.

*****

The three of you caught up to the rest of the gang soon after, and you couldn’t help but remember the last time all of you had ridden into Saint Denis–when Hosea died. You slipped away with Abigail, but you still saw it all happen. You shook off the memory, trying your best to seem nonchalant. To the people of Saint Denis, you were just a woman with her husband and his friends. Sure, the whole lot of you were heavily armed, but many people in Saint Denis were. Besides, this was a city–people would have needed to worry about other people to care about what you were doing. You took a deep breath, reminding yourself that you would be okay.

“You good?” Arthur asked, having noticed your anxiety.

You nodded. “Just nervous, is all. Haven’t been on a job in ages.”

“One last time, gentlemen,” Dutch started. “I got us a river boat. We’ll head up to New York or Chicago, and get a real boat from there to the tropics.”

“Chicago ain’t on the Coast,” you whispered, rolling your eyes. He didn’t have a damn plan, and you knew it. These other people, they might not have caught on, but you could see his bullshit from miles away.

“So long as it isn’t Guarma,” Javier said from behind you.

“Oh, it’ll be paradise, son!” Dutch reassured, as if he knew what paradise even was. You were certain that he’d do the same thing he always had–the whole ordeal reeked of his and Micah’s ferry job in Blackwater, and all that had come from that ‘one last score’ was more ‘one last scores’.

“It’s all coming together, Dutch, just like we planned,” Micah chimed in.

“That okay with you John? Arthur?” Dutch mocked, “Or do you ‘insist’ on something different?” You wanted to say something, but Arthur put his hand out, as if to say ‘do not’.

“Sounds about as good now as every time I heard it before,” John fired back, saying exactly what you were thinking.

“Oh, Abigail must be real excited, all packed up like she is,” Micah taunted. “I could just see her in a little grass skirt-”

“Don’t talk to me, you son-of-a-bitch,” John interrupted.

“Boys, boys, okay now, let’s keep it down,” Dutch said, attempting to slip back into the role of the level-headed peacemaker that he’d refused to play for so long. “We don’t wanna draw attention to ourselves goin’ through here. Nice and easy through town, fellers.”

Continuing to push, Micah said, “Ah, Saint Denis… good to be back. Happy memories, huh, John?”

“Will you shut up, Micah?” you fired. “He ain’t botherin’ you.”

“That’s enough!” Dutch declared. “Quiet, all of you.”

Dutch led the lot of you the rest of the way to the train station, occasionally nodding or saying hello to people on the sidewalks. When you arrived, all of you dismounted, Dutch giving everyone their instructions, saying, “Cleet, Sadie, and Y/N, you board halfway along. John, you and Arthur are gonna board at the back. Rest of you, follow Micah and I, and join once they stop the train.”

As if on cue, the train came barrelling into the station. Bill, in his infinite wisdom, said, “Here she comes,” as if it was not already abundantly clear that the train was on its way. What also happened to be obvious was the fact that the train was not slowing down.

Arthur glanced at Dutch as the train passed you by, saying, “Should I just… sneak on now?”

“Goddamnit,” Dutch said, looking back at Micah. It was odd how he’d gone from looking at Hosea to Micah, of all people. “Well,” he decided, “everyone mount up.”

“We’re still going through with this?” Arthur asked, brows furrowed in disbelief.

“Of course we are!” Dutch fired back, and the lot of you climbed back onto your mounts in hot pursuit of the runaway train. John yelled at Arthur–something about catching up–but you ignored it, focusing on your own task: getting onboard the train and getting to the money. You pushed Waldo forward, guiding him into a sprint. You jumped onboard in the back carriage, which was flat. Pistol drawn, you took out two of the guards that emerged from the car in front of you with a familiar ease. You followed Sadie and Cleet through the train, taking out guards whenever you could. The three of you made it through without much kickback, and it wasn’t until you heard yelling from behind you that you realized something had gone wrong: one of the train cars caught on fire, and John and Arthur were stuck on the other side of the fire.

“Let’s get over there and see what we can do to help,” you said, motioning for the other two. Without checking to see if they had followed, you made your way to the flat car in front of the one on fire. Just as you got there, Arthur and John jumped onto the car from The Count and Brown Jack.

“Uncouple that carriage, before it blows us all up!” Arthur shouted, pointing at the burning carriage.

“I’m on it!” John called, running to the back of the car.

In front of Arthur, there was a gatling gun, presumably left out open by whatever soldiers you’d shot down minutes before. He looked around, taking note of the lookout on the hill–meaning you guys hadn’t stopped the train in time–and glanced back down at the gun.

“Man the gun, Arthur!” John shouted.

“Sure,” Arthur said back, grabbing the head from its wooden crate and latching it onto the post. John uncoupled the carriage with ease, too, releasing the train from the fire that had threatened your pursuit. John called for all of the riders to get on the train, and, as Bill jumped onboard, John was clipped by a bullet in the shoulder, sending him flying backwards off of the train.

“John!” Arthur shouted, flinching from the shots. Quickly, he whipped back around, shooting the soldier who had knocked John down in the head. Dutch promised to get John, so long as the rest of you got the money.

You nodded at your husband to reassure him, saying, “Man the gun. We got you covered.”

“I’ll go stop the train,” Bill said, grabbing his rifle.

“Do not stop the train!” You responded, shooting a soldier trailing you guys. “You can secure up ahead, but do not stop this damn train or we’re dead, you hear me?”

“Got it!” Bill shouted back, heading to the front with Javier and Cleet.

“Shit, we got a lot of riders on our tail, Arthur,” Sadie said, guns drawn.

“I see ‘em.” Arthur was already shooting at the three or so men headed towards you. As the soldiers approached from all sides, Arthur began swinging the gun around, killing men and horses alike–it’s hard to aim with a gatling gun, after all–and you and Sadie tried your best to assist him.

“It’s nice to see you in action, Y/N,” Sadie shouted. “I heard you was good with a gun!”

“I’m better with poetry books, but sure, I can handle myself in a gunfight,” you said back, shooting the hat off of a soldier in pursuit. “There’s a horde of ‘em to the left, Arthur.” Arthur nodded and swung the gun to the left as you shot at the soldier again, this time shooting him out of the saddle. You and Sadie continued to shout your warnings at him. After passing through a bridge, there appeared to be no one else on your tail, so you said, “Get off the gun; we gotta get to the money.”

The three of you pushed forward, only going a couple of cars further than where you’d been. Arthur quickly dug the dynamite out of his satchel and placed it on the doors. “Alright, I guess I better blow this thing,” he muttered.

Stepping back, he shot the dynamite, and the doors came open. He ran inside, with you and Sadie posting on either side of the door. “We got something,” he said, looking around. “We got something!”

Throwing a money bag to you, he instructed you to catch. “There’s more!” he said, tossing a bag the size of your torso at you. And another. And another. You were so overwhelmed with the amount of money that you didn’t notice Bill barrelling toward you, jumping from the top of the carriage.

“Morgan!” he said, “The driver’s dead! This thing ain’t stoppin’, we gotta get off.”

“Okay then,” Sadie said, dumping a bag of money into Bill’s arms. “Let’s go!” The four of you grabbed your bags and dove off of the train, barely making it off before it went flying from the bridge Arthur and John had blown up.

You looked down at the wreckage, saying, “Jesus.”

“We’re alive,” Bill chimed in.

“Yeah, just about,” Arthur said back, looking at the rest of you and coughing.

“Let’s get the hell outta here; regroup with the others,” you said, stepping away from the cliff, which you preferred not to be particularly close to in the first place. The rest of them followed you back. You were met on the tracks by Dutch, Micah and Joe. “Where’s everyone else?” You asked, heaving your money sack onto the ground.

“Where’s John?” Arthur added, staring at Dutch expectantly. The rest of the men–Javier and Cleet–fell in.

“I tried,” Dutch said, looking down at all of you. You slipped your arm around Arthur’s–a reminder not to fly off the handle at whatever response he got. “I tried.”

“He didn’t make it,” Micah said, peering at you guys from behind Dutch. You felt sick. With John gone–dead, apparently–Arthur was left with a choice you knew he’d never make. He could stay with Dutch, link himself to the carnage, latching even tighter to Dutch’s dry, empty teat, or he could take you and leave, ending all of this once and for all. “That patrol killed him. We had to run.”

“Come on,” Dutch said abruptly, before any questions could be asked. “Let’s go. Before another patrol turns up.” The men took off, leaving you and Arthur on the tracks. You watched him, trying to catch his gaze for just a moment, but he wouldn’t look at you. He stared straight down, wheezing.

“Let’s go, Arthur. We don’t have time to fret, okay? We can worry about this later, but right now, Dutch is right; we gotta go.” You tugged at Arthur’s arm, dragging toward your horses. He moved without protest, still quietly pondering the events that had just unfolded. You had a feeling that whatever happened after this would not be good.

You and Arthur saddled up, taking off after the gang. The ride back to camp was… solemn, with no one saying much. As tense as things had gotten between everyone, John was a part of the family, and that took its toll. At least it did on most of you. Dutch and Micah seemed to be just fine about the ordeal, quietly chattering at the front of the pack. You were sure Arthur had noticed this too, but didn’t say anything about it–he wouldn’t be in the mood to talk much, not after what you’d learned.

Right before the turn to enter camp, everyone in front of you slowed up. You eased Waldo to a halt, looking around. “What’s goin’ on?” you asked Arthur, brow furrowed.

“Don’t know, but I don’t like it,” he whispered back.

And then you heard it. Young Tilly, scared out of her mind, saying that the Pinkertons took Abigail. Arthur sent you a sideways glance, an odd expression painted across his face, and you realized that he’d chosen to fight for John, even though he was out of the picture. The family he never had, or something like that. Maybe if your son had lived, he’d fight like this for you, you thought. Micah insisted to let Abigail go–to let her die–because John was already gone, and despite Arthur’s pleas, Dutch could not be swayed in the opposite direction.

Arthur threw himself out of the saddle, positioning himself beneath Dutch–in front of The Count–like he was begging him to go rescue Abigail. Tears swelled in your eyes at the sight of it–seeing your husband begging Dutch to save a woman he’d refused to let go hours earlier–and you knew that, despite your own protests to the whole affair, you’d go with him. You’d help, not because you thought it was the best way (you couldn’t help but side somewhere in the middle with this; you found yourself wishing for a third option where you waited a while before sneaking in and getting her out), but because you knew that it was the only way Arthur would go, and you were afraid he’d get himself killed while you weren’t with him.

They ignored him and rode past, leaving you and Sadie and Arthur and Tilly and Jack to yourselves. Arthur coughed, putting his hands on his knees and spitting blood. “Well, I guess that’s that, then.” He stood. “All them goddamn years.” Without pausing to think, he grabbed his horn to mount up. “I’m goin’ to get her.”

“Not without us, Arthur,” Sadie said, pushing forward. You nodded, adding, “We’ll cover you.”

Arthur frowned, saying, “No, Y/N, you need to stay. Me and Sadie’s all we need. Get everything together and we’re runnin’ after this. We’ll go down to Big Valley and get that portrait.”

You frowned. “I don’t want to leave-”

“I know, but it’ll be faster. Once Abigail is safe, we’re out of here, no questions asked. Stay with Tilly and Jack. We’ll meet up at Copperhead Landing and go from there, okay?”

“Okay,” you said breathlessly. Climbing out of your saddle and making your way to him, you said, “Oh, Arthur, I-” You leaned into his chest, holding back tears.

“I know.” He cupped your face, kissing you softly on the forehead. “I love you, darlin’.” He reached into his satchel, pulling out stacks of cash and other valuables. “Take this back and pack it up. And the money, too. It’ll get us out of here.”

“Okay. Stay alive for me.”

“I will, darlin’. I will.” He kissed you again, this time with more urgency. He mounted up, saying, “I’ll be back.”

“You’d better.” You climbed back onto Waldo and watched as Arthur and Sadie disappeared into the distance. Turning to Tilly, you said, “Take the money bags and Jack straight to Copperhead Landing and I’ll meet you there once I’ve got our stuff. We’ll regroup there and get you someplace safe.”

She nodded, squeezing Jack as if to tell him that things would be okay.

“I don’t think it’s safe for you to go back into Camp.” You added, and Tilly agreed, so you set off in opposite directions–Tilly towards safety and you towards a battlezone.

When you got there, everything had been stripped. Miss Grimshaw was ordering people around while Dutch and Micah conversed by Dutch’s tent, which hadn’t been touched. You quickly dismounted and made your way to yours and Arthur’s tent, trying your best to be discreet, but it still caught the attention of Javier, who’d been sitting by the fire next to Bill.

“Running from something?” Javier asked.

“I’m packing, just like the rest of you.” You bowed your head and continued forward, stepping into your tent.

“Where’s Arthur, then?” He followed after you.

“Doing what you folk were too cowardly to do,” you fired back, closing the curtain to your tent in his face.

As quickly as you could manage, you dug through everything, putting the essentials into a leather suitcase with your initials engraved on the handle. You packed shirts, skirts, pants, books, and all of your valuables. Arthur’s pictures, his mother’s flower, his shaving equipment. Your wedding rings. Newspaper clippings, your respective journals. Little knick knacks Arthur had gifted you after his many journeys. It scarcely fit in the suitcase, but you managed. You layered your clothes to take more. You couldn’t leave it all behind, not with the little money you two had. You gripped your suitcase and hurried out.

“Leaving so soon?” Micah called after you.

“They’re traitors,” Javier taunted.

“I oughta show them what we do to traitors,” Bill said in response.

You kept your head down and continued towards Waldo, strapping your suitcase onto his back. The men continued to hurl insults towards you, about how you were abandoning them and that they knew Arthur was crooked. You wanted to turn and scream at them, to call them fools for staying and bastards for refusing to help Arthur, but you kept your mouth shut, determined to let everything work out. You’d get out. You’d head somewhere new, somewhere he could breathe again, and it would be okay. You’d get your portrait done and live on a homestead like normal couples did. Maybe you’d try to have a kid again.

“Going somewhere?” A familiar voice said from behind you.

“I do not wish to speak to you, Dutch,” you said, trying to sound cordial.

“Ever since you came along, Arthur has been doubtin’ me, you know?” He stepped next to you, putting his hand on Waldo. “You’ve been whisperin’ in his ear for six years now.”

“Arthur’s not doing anything. This is on my own accord,” you lied. “I can’t stay here any longer–it’s too much for me.” You mounted up, looking down at Dutch. “I wish Arthur would agree with me, but he’ll be back, no doubt. He’s too damn loyal.”

Dutch laughed, watching as you pulled away, riding out of Camp for what would be the last time. You didn’t know if he believed you or not, but you hoped he wouldn’t follow you. Everything would be fine if he didn’t follow you out. You couldn’t imagine that what you did mattered, seeing as how you had hardly contributed to any of Dutch’s causes (except to say that they’re dangerous), but it was hard to tell with Dutch anymore.

You waited at Copperhead Landing with Tillly for hours. There was no trace of Dutch or Micah or any of the other guys from Camp, but there was also no trace of Arthur or Sadie. Eventually, you grew restless, and left your things with Tilly so you could sneak into Van Horn yourself. You hadn’t been on the radar of the law in years–they wouldn’t expect to see you barrelling into town, especially not dressed like a proper lady.

You managed to walk through the town completely unscathed, strolling right up to the front of the building the Pinkertons had posted up in before you were questioned. A fat man with a bald head asked you where you were going and you hastily held a knife against his throat, telling him you’d kill him if he didn’t lead you into the building. The best part was–being that it was almost dark–that no one could see you. He walked you straight in, hands up, telling them not to shoot you.

In the room, you found Sadie hogtied and gagged on the ground and Abigail strapped to a chair. Arthur was nowhere to be found. “Put your guns down or I’ll slice his throat,” you instructed the two guards. They did, raising their hands to the sky. You stepped forward and kicked their weapons away. “Untie them.” You motioned towards Abigail and Sadie with your free hand, grabbing your pistol right afterwards.

“No can do, Mrs. Morgan,” a voice said from a dark corner of the room.

“Who the hell are you?” you asked, looking towards the location of the voice.

“Agent Milton, Pinkerton Detective Agency. We thought you were dead until we heard of another woman running with the Van Der Linde gang on that train stunt you pulled earlier. I never thought I’d see you in the flesh.” He stepped forward.

“I’ll slice this fucker’s throat-”

“I don’t doubt that you will. But we have your husband back here, and it’d be a shame if we did the same to him.” He grabbed a lantern from a table next to him, holding it towards the dark corner of the room. Sure enough, there was Arthur, bloodied, barely conscious, and tied to the wall. “Have you ever heard of lex talionis, Mrs. Morgan?” Milton asked.

“Of course I have,” you spat. “An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth; what do you want in return?”

“Give me Dutch Van Der Linde or they’re dead.” Milton smiled.

“I can’t,” you responded. The man you were holding wrapped his arm around yours. “He’s packing up to leave right now; I don’t know where he’s going.”

“Tell me the truth.”

“That is the truth,” Arthur said weakly, coughing, from behind Milton. “They’re leavin’ with the money.” Blood dripped out of his mouth. Milton turned towards him, setting down the lantern.

“Calm down, Mr. Morgan,” he said. “That’s quite a cough he’s got there.”

“Sure,” you responded. “Tuberculosis. He’ll be dead soon anyway… and you with him.” You tightened your grip on your pistol, getting ready to aim, when the man you were holding flipped you over his body, slamming you into the hardwood floor, winding you. In doing this, though, he’d managed to slit his own throat. Suddenly, Milton was staring down at you, gun drawn. The other men were trying to locate their own weapons.

“Don’t move an inch!” Milton shouted. You still had the knife in your left hand, soaked with the man’s blood, and your pistol in the right. “Let go of your weapons or we’ll shoot!”

You were effectively stuck. A gun aimed straight at your face and only a knife to defend yourself with. One of the men picked up his revolver. You weighed your options. You could try and get the knife to Arthur, but there was no guarantee that he’d be strong enough to do anything. Or the gun, but you weren’t sure he’d be able to see well enough to shoot. You could try to get it to Abigail, but she wasn’t untied. Still, her bonds looked loose. She started wiggling, nodding at you. You flung the weapons towards her.

“Arthur will be dead, sure, but I’ll be just fine. We offered him a deal, Mrs. Morgan. It’s a pity he refused to take it.” He sneered at you.

“He’s a fool. I’ve been tellin’ him that for 6 years.” The other two men appeared around you, pointing their revolvers at your head. Abigail was wiggling her arm loose out of the corner of your eye.

“Not all you folk have quite so many scruples. Old Micah Bell…” Milton stepped back, leaning against the table that he’d set the lantern on.

“Micah?” Arthur asked.

“You mean Molly?” You chimed in, sitting up a little. One of Milton’s men shoved his revolver in your face, forcing you back down.

“Molly O’Shea? We sweated her a couple of times, never talked a word, had to let her go. Micah Bell… we picked him up when you boys came back from the Caribbean and he’s been a good boy ever since.”

Abigail gave you a slight nod, free, and quickly got to untying Sadie.

“Micah?” You asked again, stalling. “But he’s been so-”

“He told us about everything; the job today, your involvement with the Indians and the Army.” Milton crossed his arms with a confident swagger.

“Then why’d you ask about Dutch?” You asked, frowning. “If you knew where we were the whole time, why would you ask?”

“Wanted to see if you’d tell the truth about the whole thing. We’ve heard that Mr. Morgan was undecided.” You glanced back to Abigail and Sadie, then back to Milton. Arthur coughed, his head limp, and blood dripped from his mouth to the floor. He looked pathetic. You wished you could rush to his side and help him somehow, but you were a little occupied.

You figured the best thing you could do from there was come up with a little sob story until Abigail had freed Sadie and gotten their weapons, so you said, “You know, I’ve waited on Arthur to get away from this for ages. All I ever wanted was for him to cut loose and run away from that Gang. I knew it would be our downfall.”

“That it was, Mrs. Morgan,” Milton said, but then a gun was fired and he crumpled to the ground. Two more shots rang and Milton’s men followed suit, falling onto the hardwood floor.

“Horrible men,” Abigail muttered, turning away.

“You okay, Y/N?” Sadie asked, offering you a hand. You took it and stood, nodding, and then made your way to Arthur.

His arms were in shackles that were chained to the wall. “Oh, Arthur,” you whispered. “Search their bodies for keys to these things.”

Sadie found them in Milton’s pocket, so you unlocked Arthur’s shackles and he came tumbling down onto you, unable to support himself. “What did they do to him?” you asked, looking at the girls.

“They nearly beat him to death,” Abigail said, frowning. “They caught him trying to untie me and attacked him.”

“Let’s get him up,” you said, motioning for Abigail and Sadie to get on either side of him. The three of you stood in unison, supporting Arthur’s weight. “They’ll have heard the commotion we made, so more of them will be coming, no doubt. We need to get out of here.”

The three of you led Arthur to your mounts, helped him on, and hurried out of Van Horn, magically escaping a gunfight. When you got to Copperhead Landing, Jack was asleep in Tilly’s arms. The only light in the area was from the moon and stars. You tapped Arthur’s thigh, saying, “I gotta get down.”

Arthur nodded glumly and slipped off the side of Ralph, his horse (Abigail was on Waldo), and held on to his back for stability. He couldn’t hold his head up all the way. You wanted to take him away somewhere, to bring him to a place where he’d be able to rest, but you guys had a long way to go.

“Where’s John?” Abigail asked, frowning at the sight of Jack and Tilly, but no John. “He didn’t run, did he?”

“He’s… he’s dead,” you managed. “He didn’t run on you guys–he wouldn’t do that again. I’m so sorry, Abigail, but he… he fell and Dutch-” Abigail burst into tears, pulling you into a tight hug. “I’m so sorry.”

“We’ll go back for him,” Arthur mumbled, stepping away from Ralph and towards the two of you. “We’ll go find him and give him a proper burial like you wanted, but I gotta have a little chat first.”

“Arthur-” You tried to interrupt, but he continued. You broke from Abigail’s embrace.

“Abigail and Sadie, you go with Tilly and you find someplace nice to stay, please. You got any money?”

“No, not-”

“Here.” Arthur reached into your suitcase and pulled out the stack of money he’d handed you earlier. “Take it and get the hell away from here.” You watched frantically as Arthur gave away your last bit of hope that the two of you would make it.

“Oh, Arthur,” Abigail said, but Arthur put his hand up, telling her not to say anything and just go. The whole lot of them did, leaving you and your husband with your horses.

“What the hell was that?” you asked, brow furrowed. “You’re giving them our money?”

“They need it more.”

“I thought we were running away.” Your voice broke at this, tears filling your eyes. “How are we gonna run away if you gave them all of our money?”

Your husband grabbed your shoulders, forcing you to look at him. He looked defeated, in a way, as if he’d fought against himself about this and finally lost. “I’m sorry. I have to go back and warn them. Micah, he’s… he’s leading all of them to their deaths.”

“They want to kill you, Arthur! They think you’ve betrayed them!” You pleaded, trying to catch Arthur’s gaze, which he refused to meet. “Arthur, please.”

“It’s been 20 goddamn years; I can’t just let them die.”

“What about your wife?” You begged. “What about what you said earlier? What about Big Valley?”

“I can’t… it’s… they need to know, Y/N, I’m sorry. I need to tell them and then we can meet up again.” He pulled you close and kissed your head, but you pulled away from him.

“I’ll never forgive you for this,” you spat. “I’ll never forgive you for picking them over me after they left you!”

“They didn’t-”

“They did! You told me last night, Arthur. They left you! There’s nothing for you there anymore. Abigail, Tilly, Sadie, and Jack are all gone. Charles is gone. John’s dead. What more could you possibly get there? I have all of our stuff!” Tears spilled from your eyes, and as much as you tried to blink them away, they stayed steady.

“I have to tell them about Micah. I can’t leave them like that, not after 20 years, not knowin’ it’s him. I don’t need you to forgive that, but I need to do it.” He climbed onto Ralph, his amber champagne coated Missouri Fox Trotter, and looked down at you. “I’m sorry, okay?”

“You’ll die.”

“Maybe not. Go up to the Wapiti Indian Reservation and find Charles. He’ll know what to do, darlin’-”

“-Don’t call me that-”

“-okay?” Arthur offered a weak smile. “I will meet you there as soon as I’m done, I promise you.”

“And then what, Arthur? Then we help the gang get on a boat to New York because it’s been 20 years and you’re obligated to do that, too? When will it end?” You wanted to hit him, to curse him for lying to you, for almost dying, for leaving you alone. You hated this so much. He was going to his death. You knew it. You knew he would never come back to you, even if he said he would. There was no way they wouldn’t kill him for accusing Micah–they were too blindly loyal–and you’d sit and wait. The vision would come true. He wouldn’t let you anywhere near Camp and, frankly, you didn’t care to be. You didn’t want to fight in that battle because it wasn’t yours. But you wished he’d see it your way, because his way had an awful ending that you were both all too aware of.

“Y/N…” he said, his voice quiet. “I love you.”

“I love you too, but I hate you.” You wiped your tears. “You’re killin’ yourself.”

“I know.” He gave you a solemn nod.

“Why can’t we just go be happy, Arthur? Is that so hard?”

“This is all I’ve ever known.” He looked forward, grabbing his hat from his saddle bag and putting it on his head, which was bruised from the beatings he’d already taken. He was hardly able to sit upright on Ralph, much less able to fight.

“You’ve known me…” He started heading towards Camp, unable to hear you. “Arthur, you’ve known me!” you shrieked, sobbing. “Oh, God!” You fell to your knees, your entire body shaking with sobs. He’d left you. He didn’t wait to hear you out anymore–you knew he wouldn’t–and now you were on your own. Nothing to live for, no one to remember you by. He’d be dead before morning–you were certain of this. Eventually, you managed to climb into your saddle and start towards Wapiti, but it was only out of fear that the Pinkertons would find you and have you shot or hanged for your entanglement with Milton.

*****

In the weeks that followed, you fell into a terrible, hollowing depression. You wouldn’t eat or drink anything that wasn’t forced down your throat, you wouldn’t talk. Charles was there, of course, but he’d never be your husband and he’d never be able to bring him back. Eventually, he went and found Arthur’s body, which was apparently at the base of a tree on a ridge that faced the East. He let you choose a burial spot, which faced the West like Arthur had always wanted. You didn’t know what to do anymore. You’d always had some sort of hope for the future–you’d imagine what everything would be like when you guys finally managed to get away–but now that he was gone, there was nothing to imagine. You quit reading and you definitely didn’t write. You just sat. It was a shallow existence, sure, but you did not know how to live without Arthur anymore. He’d saved you all those years ago, and now he was just gone.

You wanted to hate him. The way he left you was shitty and you knew it, but you could not hate him for it because you’d always known that it would be like that. You knew it would end up like that before he was even sick. Still, you felt betrayed. You were supposed to stick together in everything–he was supposed to choose you–and he hadn’t. You were used to being the second choice, of course, but that decision cost him his life and you both knew it would. He chose death over what could’ve been happiness with you. You’d never forgive him for that, even with all of the love you had for him.

“Did you eat today?” Charles asked, appearing at your side.

“No.”

“Have some soup; it’ll hydrate you too.” He handed you a bowl.

“I’m not hungry,” you said, trying to pass it back to him.

“I’m not asking. Eat it.” He pushed it back towards you. “You have to eat something at least once a day. You’ll starve yourself.”

“Maybe I want to die,” you fired back.

“You don’t want to die of starvation. That’s a painful death.” Charles grabbed a soup bowl of his own and drank from it.

“Maybe I want a painful death.”

“Eat. It’s not a request.” He forced your bowl towards your lips, despite your protests.

“Fine! I’ll get it myself!” You slurped the soup loudly, just to annoy him. “Better?”

“Yes,” Charles said, then he stood and left. He was never one for conversation, but you knew that he was there for you more than anyone else. Probably more than Arthur had been, thanks to his loyalty to Dutch. He checked in on you every day, forced you to eat, forced you to get dressed, and told you how horrible every way you’d tried to die would be. Burns, for example, were far too painful to deal with. It’d hurt to breathe. You’d sit in the pain until your heart finally stopped because it was trying too hard to fight the burn. Gunshots would be slow and agonizing, but also messy. You’d bleed everywhere as the gunpowder spread around inside your body. Knives were the same–far too messy and unreliable for convenience. What would you do if you lived, after all?

You wanted to hate Charles for this, too, but you couldn’t because, like Arthur, he took care of you. He was one of the only people in your godforsaken life who had shown that you mattered, so even if you were mad that he forced you to live, you were thankful that he cared enough to want to make it happen. And he understood your pain. He missed Arthur too. They were best friends, the pair of them, so it was hard on him, too. He wouldn’t show it, but when you couldn’t sleep at night, you could hear him moving restlessly, too. You were in the same boat, in a way, except Charles had never been abandoned by him.

*****

Years and years later, on your own homestead in Canada, you and Charles lived out a quiet life together. He’d married a fine young woman from the Reservation and moved up North to get away from the carnage you’d both left behind. You lived in a house separate from theirs, one small enough for you and another–room for Arthur, if he was still alive–and you were mostly content. You’d go South a couple of times a year to visit Arthur’s grave–to keep it maintained and such–but you spent most of your time on the homestead. You learned to work honestly. You kept to yourself. You wrote.

One time, on a visit to Arthur, there was a man with dark hair facing the cross. He was wearing Arthur’s hat. You immediately burst into tears at the sight of his hat, which caught his attention, and facing you was none other than John Marston. “Y/N?” He asked, stepping towards you. “Oh, my God!”

He wrapped his arms around you as your knees buckled, keeping you solidly upright. “John,” you managed, hardly able to speak through sobs. “How did… how did you…”

“They left me, Y/N, Dutch and them. I got back to Camp when Arthur did and he… he helped me get out of there. He was beaten pretty badly, by then, but he didn’t tell me nothin’. How are you?”

“He helped you get out?”

John nodded. “Said somethin’ about how he knew it wasn’t over and that he had to finish the job.”

“Did he mention me at all? Was he going to come back for me?” You sat on a rock facing the grave and John took a seat next to you. You sniffled, wiping your face. John was alive. He was alive because of Arthur.

“He kept talking about Wapiti, but he was spent before we got to the top of that mountain. Gave me his hat, but I think you should have it.” He took off his hat and offered it to you. “It’s more yours than mine, anyway. You knew him better.”

“Thank you,” you mumbled, taking the hat from him. “Did you see him die?”

“No,” he admitted. “But I always assumed he did. I learned from Charles a couple of years back. I think he’s up North now-”

“He is. We live on a homestead together.”

“Really?” John raised his eyebrows, smiling a little. “Good for you guys.”

“No, not like that. He has a wife. They just let me live there. It’s good, honest work.” You looked down at the hat in your hands, inhaling deeply. “No, Arthur is my only love, I fear.”

John sat for a second, staring at the ground. “He was a good man. The last thing he said to me was to check in on you, but I never did. I went to my family and we ran, but… I wish I had gone to find you. Maybe I could’ve brought you back to him or somethin’... I don’t know.” He took a deep breath. “He loved you, though. I know that.”

You nodded. “Not enough to run away with me.”

“No, he was going to. We’d talked about it the whole time we stayed in Beaver Hollow. He mentioned it to Sadie, too. I bet Charles knew he’d planned to.”

“Why wouldn’t he tell me?”

“Would it have made a difference?”

You thought on that for a moment. “I guess not.” You smiled softly. “I get the feeling that Charles has kept a lot from me.”

“He’s not very sociable,” John responded with a slight smile. “I’m glad you’re okay, Y/N.”

“You too, John. Last I knew of you, you were dead. Where are you staying now?”

“Little ranch called Beecher’s Hope down in West Elizabeth. You should come down sometime and visit. It’s nice.”

“I’m okay,” you said, staring at Arthur’s grave. “This is the furthest South I come anymore. I don’t want to see anything else–no more reminders of Arthur, you know?”

“I suppose.” John took your hand, shaking it, solemnly meeting your gaze. “I have to get back to my family.”

“I have a couple of people to check in on, so that’s okay. I keep tabs on some of the people who knew him.”

John smiled. “He’d like that.”

“I know. He’d love the homestead I’m living on. It’s so open and free…” You sighed. “I miss him. I see him everywhere.”

“Me too,” John said. “Me too.”

*****

Years and years after the death of John Marston and Charles Smith, you found yourself ill with pneumonia. You’d watched as the world grew up around you–becoming something you couldn’t recognize–and though you’d remained set in your ways, you felt that you lived in an entirely different place. Your homestead had stayed the same, though, and it was here that you were determined to die.

Janet, the great-granddaughter of Charles Smith, liked to listen to the stories you told. She sat at your side and listened as you recounted the time you and Arthur danced under the stars after he’d told you he loved you. You could see him then, sitting sweetly in the chair opposite Janet’s, and you could smell his musk. People smelled better in 1966 than they had in 1899. His hand was by your arm–you could practically feel the warmth coming from it. His breathing was no longer ragged and weary like it had been in his final month, instead rhythmic and soft. You smiled. “He’s here now,” you told Janet.

She smiled back, thinking you were crazy, and squeezed your hand as Arthur eased you into a quiet, peaceful death. You were together again, at last.

#rdr2#red dead redemption two#arthur morgan fic#arthur morgan#arthur morgan x female reader#arthur morgan x reader#rdr2 arthur#rdr2 fanfic#rdr2 arthur morgan#canon compliant#idk

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

if their comfort character is arthur morgan… RUN the OTHER way. they will talk about his eyes and his voice and his hair and his smile and his hands and his arms and his shoulders and back and

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

i’ve been doing everything i can to push off cherry waves (i can’t get it right!!!!), including:

1) writing a very angsty short story about a girl named july

2) doing algebra (yuck!)

3) getting VERY involved in the indycar community

4) running 5ks

5) spending 4 hours trying to find a horse with good stats in story mode (failing btw)

6) doom-scrolling on tiktok

just know that i will finish it eventually, okay!

#rdr2#arthur morgan#red dead redemption two#im trying okay!#yk it’s bad when i procrastinate my usual procrastination methods#idk

1 note

·

View note

Text

Harvest Moon

Summary: Short Arthur and f!reader oneshot that takes place well before the events of the game. They reunite after Y/N leaves the gang for a short while after a blowout fight with Arthur. ALSO, I know that this isn't the long one I said I was going to put out, but I'm still not happy with that one & this one feels fine. 'Tis all.

Warnings: not beta-read lol

Word Count: Roughly 2300