#Dina Fine Maron

Text

A Spotless Giraffe, Pictured in Namibia 🇳🇦, was seen and photographed for the first time in the wild just weeks after another animal with this type of coloring was born at a U.S. 🇺🇸 Zoo. Photograph By Eckart Demasius and Giraffe Conservation Foundation

Another Rare Spotless Giraffe Found—the First Ever Seen in the Wild

The sighting occurred just weeks after the unusual condition was seen in a newborn giraffe at a Tennessee zoo. Is it more common than scientists thought?

— By Dina Fine Maron | September 12, 2023

Just weeks after a giraffe at a U.S. Zoo was born missing its characteristic spots, another spotless giraffe calf has now been seen and photographed in the wild for the first time.

The unprecedented sighting occurred at Mount Etjo Safari Lodge, a private game reserve in central Namibia. Tour guide Eckart Demasius saw and photographed the solid-brown calf during a game drive on the roughly 90,000-acre reserve, according to the Giraffe Conservation Foundation. Demasius, who was not immediately available for comment, shared his photos with the giraffe nonprofit.

Sara Ferguson, a wildlife veterinarian and conservation health coordinator at the foundation, says the two recent spotless sightings are pure coincidence and that there’s no data to suggest this coloring is occurring more frequently than it had in the past.

This finding is just another example of “the weird way the world works” she says, adding that she’s “so amazed and pleased there is so much more to learn and discover about giraffe.”

Genetic Anomalies

The spotless reticulated giraffe born at Brights Zoo in Limestone, Tennessee, earlier this summer was recently named Kipekee, which means “Unique” in Swahili. The recent wild sighting occurred in another giraffe subspecies found in southern Africa, the Angolan giraffe.

Before these recent births, a giraffe with all-brown coloring was last seen at a Tokyo Zoo in 1972.

The spotless giraffe and its mother were photographed on a reserve with around 800 giraffes in central Namibia 🇳🇦. Photograph By Eckart Demasius and Giraffe Conservation Foundation

Scientists, including Ferguson, believe the solid coloring is likely due to one or more genetic mutations that haven’t yet been identified.

Some aspects of giraffe spots are passed down from mother to calf, according to a 2018 study in the Journal Peer J, and larger, rounder spots appear to be linked to higher survival rates for younger giraffes, but the reasons for that remain unclear.

Derek Lee, a Biology Professor at Penn State University and a co-author on the PeerJ Study, says that technically these two recent examples are not spotless animals, but instead —"one-spot-all-over giraffes."

It’s impossible to say what this genetic anomaly means for the animal’s health, he says, but there’s no evidence the color difference puts the animal at a disadvantage.

“We have a sample size here of one, so time will tell what happens.”

#Spotless Giraffe 🦒#Dina Fine Maron#Mount Etjo Safari Lodge | Namibia 🇳🇦#Giraffe Conservation Foundation#Sara Ferguson#Genetic Anomalies#Brights Zoo | Limestone | Tennessee#Kipekee | Unique#Angolan Giraffe 🦒#Tokyo Zoo | Japan 🇯🇵#Journal Peer J.#Derek Lee | Biology Professor | Penn State University#Namibia 🇳🇦 | US 🇺🇸

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Dina Fine Maron

January 24, 2024

Scientists have cleared a significant hurdle in the years-long effort to save Africa’s northern white rhinoceros from extinction with the first-ever rhino pregnancy using in vitro fertilization.

The lab-assisted pregnancy, which researchers will announce today, involved implanting a southern white rhino embryo in a surrogate mother named Curra.

The advance provides the essential “proof of concept” that this strategy could help other rhinos, says Jan Stejskal of the BioRescue project, the international group of scientists leading this research.

Curra died just a couple months into her 16-month pregnancy from an unrelated bacterial infection, Stejskal says.

However, the successful embryo transfer and early stages of pregnancy pave the way for next applying the technique to the critically endangered northern white rhino.

The process was documented exclusively by National Geographic for an upcoming Explorer special currently slated to air in 2025 on Nat Geo and Disney+.

BioRescue expects to soon implant a northern white rhino embryo into a southern white rhino surrogate mother.

The two subspecies are similar enough, according to the researchers, that the embryo will be likely to develop.

Eventually, this approach may also help other critically endangered rhinos, including the Asian Javan rhinoceros and the Sumatran rhinoceros, which each now number under 100 individuals, Stejskal says.

But the northern white rhino’s current situation is the most pressing by far.

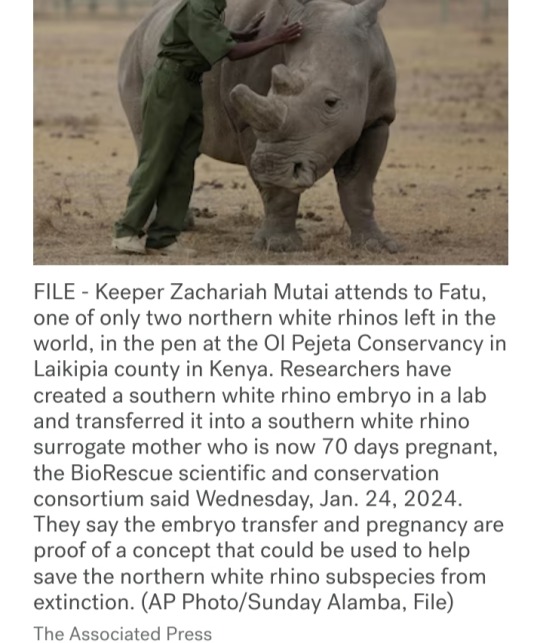

There are no males left, and the only two remaining animals are both elderly females that live under armed guard on a reserve in a 700-acre enclosure in Kenya called Ol Pejeta Conservancy.

The boxy-jawed animals once roamed across central Africa, but in recent decades, their numbers have plummeted due to the overwhelming international demand for their horn, a substance used for unproved medicinal applications and carvings.

Made from the same substance as fingernails, rhino horn is in demand from all species, yet the northern white rhino has been particularly hard-hit.

"These rhinos look prehistoric, and they had survived for millions of years, but they couldn’t survive us,” says Ami Vitale, a National Geographic Explorer and photographer who has been documenting scientists’ efforts to help the animals since 2009.

“If there is some hope of recovery within the northern white rhino gene pool — even though it’s a substantially smaller sample of what there was — we haven’t lost them,” says conservation ecologist David Balfour, who chairs the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s African rhino specialist group.

Blueprints for rhino babies

To stave off the animal’s disappearance, BioRescue has used preserved sperm from northern white rhinos and eggs removed from the younger of the two remaining females.

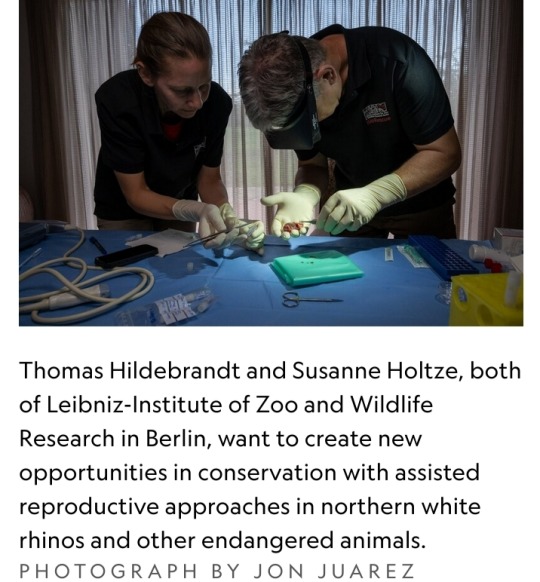

So far, they’ve created about 30 preserved embryos, says Thomas Hildebrandt, the head scientist of BioRescue and an expert in wildlife reproduction based at the Leibniz-Institute of Zoo and Wildlife Research in Berlin.

Eventually, the team plans to reintroduce northern white rhinos into the wild within their range countries.

“That’d be fantastic, but really, really far from now—decades from now,” says Stejskal.

Worldwide, there are five species of rhinoceros, and many are in trouble.

Across all of Africa, there are now only about 23,000 of the animals, and almost 17,000 of them are southern whites.

Then there are more than 6,000 black rhinos, which are slightly smaller animals whose three subspecies are critically endangered.

In Asia, beyond the critically endangered Javan and Sumatran rhinos, there’s also the greater one-horned rhino, whose numbers are increasing and currently are estimated to be around 2,000.

The BioRescue effort has experienced many setbacks, and even though the team now has frozen embryos, the clock is ticking.

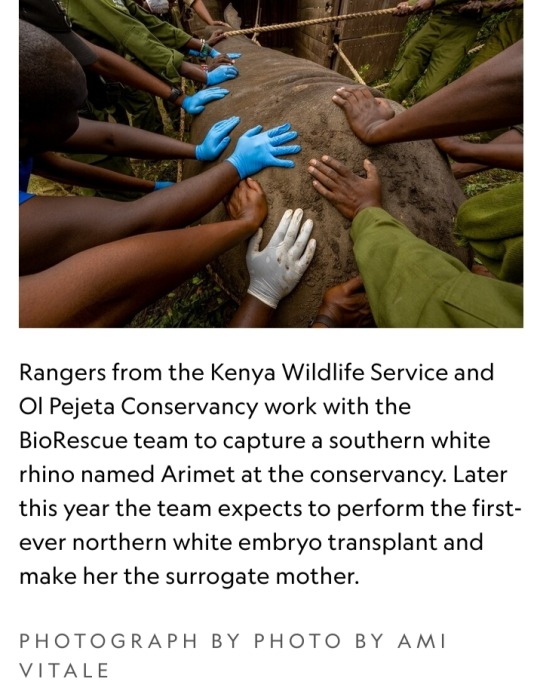

The researchers intend to use southern white rhinos as surrogate moms for the northern white rhino embryos.

However, scientists want any northern white rhino calves to meet and learn from others of their kind, which means they need to be born before the two remaining females die.

“These animals learn behaviors — they don’t have them genetically hard-wired,” says Balfour, who’s not involved with the BioRescue work.

But birthing new animals in time will be a challenge.

“We’re really skating on the edge of what’s possible,” he says, “but it’s worth trying.”

Najin, the older female, will be 35 this year, and Fatu will be 24.

The animals, which were born in a zoo in the Czech Republic, are expected to live to about 40, says Stejskal, who also serves as director of international projects at the Safari Park Dvůr Králové, the zoo where the animals lived until they were brought to Kenya in 2009.

Impregnating a rhino

The next phase of BioRescue’s plan involves implanting one of their limited number of northern white rhino embryos into a southern white rhino surrogate mother — which the group plans to do within the next six months, Stejskal says.

They’ve identified the next surrogate mother and set up precautions to protect her from bacterial infections, including a new enclosure and protocols about disinfecting workers’ boots.

But now, they must wait until the female rhino is in estrus — the period when the animal is ready to mate — to implant the egg.

To identify that prime fertile time, they can’t readily perform regular ultrasounds at the conservancy as they might do in a zoo.

Instead, they have enlisted a rhino bull that has been sterilized to act as a “teaser” for the female, Hildebrandt says, adding that they must wait a few months to make sure that their recently sterilized male is truly free of residual sperm.

Once the animals are brought together, their couplings will alert conservancy staff that the timing is right for reproductive success.

The sex act is also important because it sets off an essential chain of events in the female’s body that boosts the chances of success when they surgically implant the embryo about a week later.

"There’s little chance the conservancy staff will miss the act. White rhinos typically mate for 90 minutes," Hildebrandt says.

What’s more, while mounted on the females, the males often use their temporary height to reach tasty plant snacks that are generally out of reach.

Boosting genetic diversity

With so few northern white rhinos left, their genetic viability may seem uncertain.

But the BioRescue team points to southern white rhinos, whose numbers likely dropped to less than 100, and perhaps even as few as 20, due to hunting in the late 1800s.

Government protections and intense conservation strategies allowed them to bounce back, and now there are almost 17,000.

“They have sufficient diversity to cope with a wide range of conditions,” says Balfour.

Researchers don’t know exactly how many southern white rhinos existed a century ago, he says, but it’s clear that the animals came back from an incredibly low population count and that they now appear healthy.

Beyond their small collection of embryos, the BioRescue team hopes to expand the northern white rhino’s gene pool by drawing from an unconventional source — skin cells extracted from preserved tissue samples that are currently stored at zoos.

They aim to use stem cell techniques to reengineer those cells and develop them into sex cells, building off similar work in lab mice.

According to their plan, those lab-engineered sex cells would then be combined with natural sperm and eggs to make embryos, and from there, the embryos would be implanted into southern white rhino surrogate mothers.

Such stem cell reprogramming work has previously led to healthy offspring in lab mice, Hildebrandt says, but rhinos aren’t as well-studied and understood as mice, making this work significantly challenging.

A global effort

The northern white rhino revitalization venture has cost millions of dollars, supported by a range of public and private donors, including the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

Other partners on the effort include the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, the Czech Republic’s Safari Park, Kenya Wildlife Service, Ol Pejeta Conservancy, and also Katsuhiko Hayashi, a professor of genome biology at Osaka University in Japan who conducted the mouse stem cell research.

Building upon Hayashi’s stem cell techniques could ultimately bring the northern white rhino gene pool up to 12 animals — including eggs from eight females and the semen of four bulls, according to Stejskal.

An alternative approach to making more babies, like crossbreeding northern and southern white rhinos, would mean the resulting calves wouldn’t be genetically pure northern white rhinos, Hildebrandt notes.

The two subspecies look quite similar, but the northern version has subtle physical differences, including hairier ears and feet that are better suited to its swampy habitat.

The two animals also have different genes that may provide disease resiliency or other benefits, Hildebrandt says.

There are unknown potential differences in behavior and ecological impact when populating the area with southern white rhinos or cross-bred animals.

"The northern white rhino is on the brink of extinction really only due to human greed,” Stejskal says.

“We are in a situation where saving them is at our fingertips, so I think we have a responsibility to try.”

🩶🦏🩶

#northern white rhinoceros#rhino embryo transfer#in vitro fertilization#IVF#southern white rhinoceros#critically endangered animals#National Geographic#BioRescue#rhino horn#International Union for the Conservation of Nature#African rhino specialist group#Thomas Hildebrandt#German Federal Ministry of Education and Research#Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research#Kenya Wildlife Service#Ol Pejeta Conservancy#Katsuhiko Hayashi#genome biology#IVF rhino pregnancy

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

By the way, the USA was one of the countries that opposed to new rule that bars the exportation of elephants to zoos. A logical extension of the perversity that defines our government under trump.

Excerpt from this Smithsonian story:

The triennial meetings of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), an international treaty that regulates the trade of wild plants and animals, are among the most significant wildlife conferences in the world. At this year’s event, which spanned from August 17 through 28 in Geneva, CITES member nations passed a series of major conservation measures: a rare Caribbean gecko, sharks, rays and giraffes have all been granted key protections, to name a few examples. And on Tuesday, the conference approved one of its more controversial measures, imposing a near-total ban on transporting wild African elephants to zoos and other captive facilities.

The new rules only apply to African elephants, since Asian elephants are already subject to strict international trade regulations. But as Dina Fine Maron of National Geographic reports, Zimbabwe and several other southern African countries maintain that selling some of their elephants is a necessity. For one, it helps offset the costs of conservation efforts at home, and also prevents the animals from spilling over onto human lands, where they might destroy crops and even harm people. Tinashe Farawo, a spokesperson for the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority, also noted that the elephants are an important economic resource for a struggling country.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Conferenza CITES

Passi avanti nella tutela degli elefanti

Si è conclusa a Ginevra la conferenza internazionale triennale che regolamenta il commercio di fauna e flora selvatica. Stabilita maggiore protezione per elefanti, anfibi, rettili, e per le lontre, vittime della moda che le pretende animali domestici

Fotografia Beverly Jourbert, Nat Geo Image Collection.

di Dina Fine Maron, Rachel Fobar

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

国際犯罪組織が関与、大西洋クロマグロの違法取引は合法の倍の可能性も

タイセイヨウクロマグロは 最速の部類に入る魚だ。おそらくは最もおいしい魚でもあり、寿司では最高級とされている。巨大な魚体は金属のように光輝き、体重は500キログラムに達するものもいる。違法に取引すれば、一獲千金のチャンスもある。

ギャラリー:乱獲されるクロマグロ 写真9点

欧州刑事警察機構(ユーロポール)によると、国際的な犯罪組織が取引するタイセイヨウクロマグロは年間2000トンに上るという。これはシロナガスクジラ10頭分を超える量だ。予想を超えるこの報告は、欧州における違法取引の規模が、合法的なものの倍に達する可能性を示している。

「中トロ作戦」

捜査は、スペイン、ポルトガル、フランス、マルタ、イタリアにまたがって数カ月間行われた。その末に、スペインの警察が79人を逮捕し、80トンを超すタイセイヨウクロマグロを押収した。7台の高級車と50万ユーロの現金も差し押さえられた。ユーロポールが逮捕を発表したのは先週だが、実際の逮捕は6月末のことだ。

ユーロポールの環境犯罪の専門家、ホセ・アルファロ氏によれば、今回の摘発調査はマグロの高級部位にちなんで「タランテッロ(中トロ)作戦」と命名された。作戦を指揮したのはユーロポールだが、関係諸国が連携。書類偽造や密輸に関わったとみられる犯罪組織のほか、複数の水産会社が関与していたと、ユーロポールはみている。

アルファロ氏によると、押収されたクロマグロはほとんどが道路脇で回収したものだという。スペイン、ポルトガル、イタリアで一斉捜査が行われたと知って、マグロを運んでいたトラック運転手が慌てて投げ捨てたらしい。

このニュースは、環境保護���体に衝撃を与えた。「違法取引の規模に驚きました。由々しき事態です」と、大西洋まぐろ類保存国際委員会(ICCAT)においてピュー慈善財団 の代表団長を務めるパウルス・タック氏は語る。ICCATは、年間のマグロ漁獲可能量や国別漁獲割当量を設定している世界的な組織だ。

捜査員らは、マグロの密売組織は長年にわたって活動しており、年間で最大2500トンを密売し、1200万ユーロを超える利益を得ていたとみている。また、違法操業を追跡していた欧州当局は、イタリアやマルタ近海で水揚げされた魚がフランス経由でスペインへ輸入されていたことを突き止めている。

この大規模な違法操業は、タイセイヨウクロマグロの持続可能性を脅かしかねないと、タック氏は指摘する。大がかりな違法操業が明るみに出たことは、今後マグロの漁獲可能量について交渉する際の重要な材料となるという。

保管状態が悪く食中毒の被害者も

スペイン当局がこの件について、ユーロポールに初めて接触したのは昨春のことだ。海産物市場に供給されているクロマグロが多すぎると連絡。捜査した結果、合法的な漁獲量を上回るマグロを船底に隠して運ぶ漁船がすぐに多数発覚した。これらのマグロを運んでいたトラック運転手は、実際には14トンの積み荷があっても、4トンとしか記載されていない漁獲証明書を提示していた、とアルファロ氏は説明する。同氏は、その手のトラックがマルタの主要な漁業倉庫に到着した現場に居合わせたことがある。

地下ネットワークで取引される魚はたいてい保管状態が不十分で、急速冷凍もされていない。そのため、少なくとも8件の食中毒の原因になったという。

タイセイヨウクロマグロは寿司や刺身で食べられることが多く、日本が最大の輸入国だ。しかし欧州市場も規模が大きく、スペインやイタリアでもステーキなどに使われている。

人間の食欲が、この魚の存続を脅かしている。ICCATは10年前、タイセイヨウクロマグロの資源管理は「国際的な不名誉」だと批判している。当時マグロ資源は大きく落ち込んでおり、野生動物の取引を規制する「絶滅のおそれのある野生動植物の種の国際取引に関する条約(ワシントン条約)」の対象に加えられる可能性が取りざたされていた。

しかし、タイセイヨウクロマグロの保全策が一気に整備され、成果が上がっているとタック氏はいう。厳格な漁獲制限や電子漁獲証明制度の導入により、追跡能力などが向上したのだ。その結果、2005年に約30万トンだった大西洋東部生まれのタイセイヨウクロマグロの成魚集団は、現在では53万トンに上ると、ICCATは推計している(ただし、ピュー慈善団体によれば、この数値には不確定要素が多数ある)。

今回のユーロポールの調査結果は、タイセイヨウクロマグロ資源の回復に疑問を投げかけるものだと、タック氏は指摘する。従来考えられていた以上に、乱獲が進んでいる可能性が示唆されているという。

組織的な犯罪と聞いて、環境犯罪を思い浮かべる人は少ないかもしれない。しかし、それが現実であることが今回の捜査で明らかになったとアルファロ氏は話す。「私にとって、それ以上に重要なことはありません」

文=Dina Fine Maron/訳=山内百合子

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Image Credit: BayramGurzoglu Getty Images

Zika Exposure Even after Birth May Lead to Brain Damage

A monkey study heightens concerns about widespread harm from the virus

Article by By Dina Fine Maron (Scientific American)

A new report raises questions about whether contracting Zika virus in the months after birth may damage an infected newborn’s brain.

Researchers at Emory University injected a small number of infant rhesus macaques with the virus five weeks after birth—an age which roughly correlates with Zika exposure in three-month-old human babies—and found that although the monkeys cleared the infection from their blood as expected, the animals developed brain damage and behavioral problems.

“This is the first time [infant infection] has been studied in a controlled fashion. And while it is with a small group of animals, it does make us more concerned about what the long-term behavioral or cognitive issues may be in human infants that might have been similarly exposed,” says Ann Chahroudi, senior author on the study and an assistant professor of pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine.

The good news is infected monkeys did not develop the most severe problems seen in humans exposed to Zika prenatally, which include limb deformities, hearing and vision loss, and a small-headed condition that can form in the womb called microcephaly. Yet certain brain areas typically responsible for vision as well as emotional and behavioral responses did not develop normally in infant macaques exposed to Zika, and the animals acted strangely in behavioral tests compared with control animals not exposed to the pathogen. Connections between the amygdala and hippocampus were also weak in the infected macaques, which suggests signals sent between those two areas—ones that would help the infants recognize and respond to stressful situations—would be slow or spotty.

During testing, the infected infant animals did not act normally when faced with certain threatening scenarios. The study authors believe this was because the animals had trouble processing that they should be concerned. In particular, the infected monkeys did not freeze as they typically would when feeling threatened and expressed less hostility and anxiety in stressful situations than did animals not infected with Zika. The findings, from researchers at Emory and several other institutions, were published Wednesday in Science Translational Medicine.

The study involved eight monkeys. Two of the animals served as controls and were not injected with the virus but the remaining six were given a single injection of a Zika strain similar to the one that has circulated in Brazil in recent years. Four of the infected monkeys were euthanized in the days and weeks following infection for tissue and immunological analyses. But two of the monkeys were studied until they were a year old. Researchers periodically scanned the brains of these two and administered visual memory tests (that involved eye tracking) during the first six months of life. Later they examined the macaques’ reactions to stress by testing how they responded to the presence or stare of a human stranger—one dressed in an Al Gore mask. The way Zika acted in the brain generally fit with what is already known about the pathogen’s biology and how it attacks that organ.

One of the few bright spots from the test results was that the infected animals’ memories did not appear to be damaged; they performed as well as controls in standard visual recall tests. Still, Chahroudi cautioned that more subtle issues with memory and behavior may only become apparent later in the monkeys’ lives—a situation analogous to testing in human children, which is more informative when done on school-age kids instead of toddlers. The authors also noted another area of potential concern: Prior monkey research has shown macaques with early-life hippocampal damage go on to demonstrate schizophrenia-like characteristics in adolescence. This raises questions about what the long-term effects of similar damage may be for the mental health of those exposed to Zika in infancy.

“We don’t really have any data yet to back this up but it is a suggestion that should be considered,” says Karin Nielsen-Saines, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at the University of California, Los Angeles, who studies Zika and was not involved in the macaque study. “We’re not sure what triggers development of schizophrenia and I don’t think we can jump from ‘Monkeys develop this,’ to ‘Kids with Zika early in life will develop schizophrenia or other psychiatric conditions’—that’s a bit of a leap,” she says. Steve Goldman, a professor of neurology at the University of Rochester Medical Center also urged caution due to the small number of tested monkeys and added that the brain damage was too nonspecific to point to a condition like schizophrenia at this stage. Generally, harm to the hippocampal-amygdala circuit, he says, may be linked to mental conditions including autism spectrum disorder and anxiety disorders. But if the Zika infection occurs after birth and the monkey findings hold in humans, it is possible children’s brains would still be able to correct for any potential damage and be perfectly healthy, he adds.

In light of the new macaque findings, Nielsen-Saines says she will be changing what she tells parents who ask whether they can bring a young child to an area where the disease has become endemic. “Usually we tell parents there is not much data there, but now we can say there is an animal study saying there may be neurodeficits later—so if you could not travel with your children in the first six months of life, maybe that would be a better option.”

Although Nielsen-Saines called the new Zika findings “alarming,” she underscored that they are not yet definitive for humans. In particular, the number of monkeys was small and there may be differences between macaques and humans that could affect how the body processes the infection. It is also possible the inoculum—the amount of virus included in the subcutaneous shot the monkeys received—may not truly correlate with the amount present in one or a few mosquito bites. It is not known what the viral dose of Zika from a mosquito blood meal may be, Chahroudi says, but her team used a dose believed to approximate a mosquito bite, based on previous studies with other mosquito-borne diseases from the same family as Zika.

Researchers and clinicians still do not have any conclusive answers about the possible health effects of Zika exposure early in life, partly because such studies require careful tracking and testing to determine if children were infected in the womb or after birth. Moreover, many infected people are asymptomatic so it can be difficult to find kids with the disease. Doctors are aware of several instances in which babies acquired Zika virus via breast-feeding, but there have not been any reported health problems from that exposure.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases hopes to get a better picture of the long-term results from Zika exposure during infancy in the next few years, and recently funded a study that will examine the effects of acquiring the disease after birth among infants and young children in Guatemala. Its leaders aim to enroll approximately 1,200 individuals and monitor their health outcomes with further testing.

Scientists know human infant brains are far from fully developed. During the first year of life, human babies learn to focus their vision, reach out, explore and learn about the things around them. Our brains also roughly double in size during that time and harm to this organ can be particularly disastrous.

Chahroudi says her team is interested in repeating aspects of its work but wants to try infecting macaques later in their first year of life. The goal, she says, is to see “if there is a window of time after which we don’t see these same findings.”

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

How the world’s largest rhino population dropped by 70 percent—in a decade – BY DINA FINE MARON PHOTOGRAPHS BY BRENT STIRTON PUBLISHED FEBRUARY 2, 2021 — Just Sayin'

How the world’s largest rhino population dropped by 70 percent—in a decade – BY DINA FINE MARON PHOTOGRAPHS BY BRENT STIRTON PUBLISHED FEBRUARY 2, 2021 — Just Sayin’

Many rhinos on private reserves in South Africa—these are at John Hume’s game ranch in Nelspruit—are dehorned to reduce the chance of their being killed by poachers. But horns grow back every few years, making this a costly strategy for cash-strapped public parks such as Kruger. https://www.npr.org/2021/01/25/960378979/whos-black-enough-for-reparationsHow the world’s largest rhino population…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Madagascar’s endangered lemurs are being killed during pandemic lockdowns

Early data paints a troubling picture for these animals and their habitat.

Mouse lemurs such as critically endangered Microcebus berthae are so small they can fit in the palm of your hand. As people have been turning to forests for food and fuel during the

DINA FINE MARON

DECEMBER 14, 2020

TIANA ANDRIAMANANA WAS alarmed when she saw the fires swallowing Madagascar’s forests in March. She’d grown used to seeing illegal burns for agricultural expansion, but such widespread blazes so early in the year were extremely unusual.

The burning intensified in late March, after the nation’s coronavirus lockdown was announced. People began fleeing its capital, Antananarivo, and other cities, boarding crowded vehicles bound for rural areas. They hoped “they could work the land and then produce a yield that would help them survive the health and economic crisis,” says Andriamanana, executive director of Fanamby, a Madagascan conservation nonprofit responsible for managing five protected areas.

But working the land to grow food crops such as rice, peanuts, and maize means clearing trees. Soon, clouds of smoke—signs of illegal burning—were wafting above protected areas. In some parts of the country, more people began felling trees to burn and convert the wood into charcoal, a fuel source lighter and easier to carry than firewood.

All this illegal activity in Madagascar’s forests is especially worrying to Andriamanana and other conservationists because of the grave situation facing the island’s 107 species of lemurs—forest-dwelling primates with saucer-like eyes, long muzzles, and furry tails found nowhere else on Earth. Nearly a third of them are critically endangered, and most of the rest are considered threatened, largely because of deforestation in recent decades.

Clearing of forests threatens the island’s spectacular biodiversity, key to a tourism industry worth nearly a billion dollars a year—until the pandemic shut it down.

Madagascar’s geographic isolation and varied forest types have spawned a biological wonderland, home to thousands of endemic animals and plants that, like the lemurs, are facing pressure from humans.

Many lemur researchers left the country in March; others have been unable to travel to the remote areas where they usually work. But unpublished field reports from forest conservation patrols working with Madagascar officials, household surveys conducted by Madagascan research teams, and analysis of satellite imagery reveal a worsening situation for lemurs not only from losses of habitat but also from increased illegal hunting.

Madagascar is one of the poorest nations in the world. Malnutrition is widespread, with almost one of every two children under the age of five suffering from stunted growth. Many people in rural areas have depended on hunting forest animals for food, but with deepening poverty caused by the pandemic, lemurs are a more frequent source of meat, according to Cortni Borgerson, an anthropologist at Montclair State University, in New Jersey, who focuses on hunting and consumption of lemurs.

Before the pandemic, tourism was a cornerstone of Madagascar’s economy, supporting more than 300,000 jobs, and lemur-watching was popular. Tourism revenue amounted to about $900 million a year in a country where most people live on less than $2 a day. Yet without international flights, many of the nature guide jobs dried up, as did employment for cooks, hotel workers, and many more. Without a steady income, people have turned to the forests for food and fuel.

The critically endangered Indri indri is the world's largest lemur.

“COVID has created a serious setback because of the temporary cessation of ecotourism, which is the lifeblood of some of the communities,” says Russell Mittermeier, chief conservation officer for the nonprofit Global Wildlife Conservation and chair of the primate specialist group for the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Species Survival Commission.

“People working in conservation are trying their best,” Andriamanana says. “It is a mess—but it’s a mess everywhere due to COVID-19.”

Falling trees

Of all the threats to Madagascar’s lemurs, additional clearing of trees is the most ominous, according to Edward Louis, a leading lemur researcher and director general of the Madagascar Biodiversity Partnership, a regional NGO.

Left: … Read MorePHOTOGRAPH BY ADRIANE OHANESIAN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

Before the pandemic, sights such as this—visitors transfixed by a group of highly endangered diademed sifaka lemurs in Andasibe-Mantadia National Park—were commonplace in Madagascar forests.

If one person chops down two or three 50-year-old trees in a day—a typical number, Louis says—the cumulative reduction of lemur habitat can be disastrous. As patches of forest shrink, fragmentation isolates populations, leading to inbreeding. In addition, Louis says, too little habitat can trigger territorial disputes, sometimes leading male lemurs to kill young animals that are unrelated to them.

Getting a clear understanding of the extent of deforestation—and the resulting loss of lemur habitat—is challenging, especially during the pandemic. Country-wide satellite imagery for 2020 won’t be available until May 2021 at the earliest, based on the timeline of years past, says Lucienne Wilmé, national coordinator for the Madagascar program for Global Forest Watch, an online forest monitoring effort that provides worldwide data on deforestation.

“The Global Forest Watch data is based on percentage of canopy cover, so if there’s a hole in it, you can see it,” Wilmé says. But “holes” in the forest may not signify the absence of trees; they may instead show places where trees that lose their leaves at different times of the year appear to be missing. “It’s very complicated and very different from one forest to another,” she says.

To provide a more complete picture, the organization also relies on supplementary reports and field observations from regional research groups and nonprofits. That ground-based work—demanding in remote, hard-to-reach parts of the country—has become even more difficult during the pandemic because of travel restrictions. In addition, the unreliability of internet service can make data sharing almost impossible, Wilmé says.

According to Andriamanana—based on tracking of the roughly 1.5-million acres of protected land managed by Fanamby—deforestation has increased an average of 10 percent since 2019. By early October, the group estimated that more than 120 acres had been cleared illegally.

Hunters sometimes use traps made of a single log and a square of small branches to catch lemurs illegally for their meat, as in this protected area.

Although that small number may seem insignificant, it isn’t, Andriamanana says. Most of the losses occurred in Alaotra-Mangoro, in eastern Madagascar, and Menabe, in western Madagascar. These regions are home to critically endangered species including the Indri indri, largest of all the lemurs, and Microcebus berthae, a mouse lemur so small it can fit in the palm of your hand.

Andriamanana expects to tally additional reductions from the more frequent illegal burns that typically occur around October and November before the start of the rainy season.

The numbers lost match the numbers eaten.

Deforestation has also intensified in some parts of the 43 protected areas, encompassing 4.2 million acres, managed by Madagascar National Parks says Mamy Rakotoarijaona, its director general. In an average year about 17,000 acres of forest are lost, according to Ollier Duranton Andrianambinina, head of the parks’ department of communication and information systems.

But this year, Andrianambinina says, they’re worried that the losses will be greater. Even though Madagascar National Parks deployed new technology in 2019 to improve forest alerts for fires and surveillance, the pandemic has curtailed ranger patrols.

Charcoal rush

Despite coronavirus travel restrictions and laws prohibiting felling trees in protected areas, impoverished people in southern towns have been traveling to forest preserves in the north to find jobs cutting timber for charcoal, according to the Madagascar Biodiversity Partnership’s Edward Louis. “It’s a big business and people now just need income.”

His organization has been working with local officials to conduct ranger patrols in Montagne des Français, a protected area of dry forest in the north, and in Kianjavato, a protected area in the southeast where the nonprofit is working to preserve a corridor linking remaining areas of natural forest.

In Montagne des Français, the exclusive habitat of the northern sportive lemur—a seven-inch tall, grayish-brown animal known for its shrill screams—patrols have identified areas newly denuded for charcoal production. About 80 percent of these sportive lemurs have been wiped out during the past two decades because of habitat loss and hunting, and fewer than a hundred are thought to survive today.

“I just came back from Manombo forest in the southeast and saw the [forest] special reserve burning every day, which makes me very sad because I have conducted lemur research in that forest since 1997,” Jonah Ratsimbazafy, a Malagasy primatologist and president of the International Primatological Society, a research and conservation organization, said in late November.

Primatologist Patricia Wright, a National Geographic grantee who studies the endangered lemurs of Madagascar, discussed these unique, threatened primates in 2014 after winning the largest prize in the field of animal conservation, the Indianapolis Prize.

As the pandemic rages on, “the next six months or so will be critical for all of Madagascar,” says Louis, who, though currently based in Nebraska, is in constant touch with his teams in the country. The demands for trees and meat are continuing, and the long-term effects of habitat losses on lemurs may not be apparent for some time to come, he says.

Lemurs to eat

Before COVID-19 took hold, lemurs and other forest animals, including cat-like fossas and small, shrew-like tenrecs, had long been taken for food, although hunting lemurs has been outlawed since the 1960s.

Anthropologist and National Geographic Explorer Cortni Borgerson estimates that at least 1,600 red ruffed lemurs and 10,000 white-fronted lemurs were killed and eaten each year before the pandemic.

(Related: How pandemic-induced poaching has surged in Uganda and threatened conservation efforts in Kenya.)

Borgerson says her most recent, yet-to-be-published analyses reveal a troubling trend: Families desperate to feed themselves or sell meat in local markets are turning increasingly to hunting. She says populations of the critically endangered red ruffed lemur and threatened white-fronted lemur, in particular, are at their lowest levels in 10 years.

Based on current reports from her research teams around Masoala National Park, where she’s worked for nearly 15 years, Borgerson estimates that the density of white-fronted lemurs in the region has fallen by 56 percent—from more than 20 animals per square kilometer in 2019 to fewer than 10 this year.

Many of Madagascar’s lemurs, animals found nowhere else in the world, spend most of their time high in trees such as these in Ranomafana National Park.

What’s happening to these disappearing animals is not a mystery. “The numbers lost match the numbers eaten,” she says. Borgerson arrived at this conclusion after matching weekly data from people’s self-reporting about household food consumption collected by her research teams and comparing that information with lemur density counts.

The red ruffed lemur population density has also dropped—on average by 63 percent in just the past year, Borgerson says. Most of that loss stems from habitat loss, she believes, and about a quarter from hunting.

Reports from Ollier Duranton Andrianambinina, of Madagascar National Parks, appear to corroborate Borgerson’s findings—they, too, indicate heightened lemur hunting. From January to September of this year, their patrols have seen increases in hunting well above the norm—564 lemurs caught in traps and 132 instances when they encountered people hunting.

Aubin Andriajaona, the Madagascar Biodiversity Partnership’s site manager for Montagne des Français, says deforestation there was “very up” from March to June and that patrols in the area sometimes came across lemur body parts and bits of fur.

Raising awareness, providing options

Tiana Andriamanana says Fanamby’s patrol teams sometimes come across people who are unaware that burning trees is illegal. When that happens, she says, the teams have the discretion not to arrest them but to explain that such burns are illegal and why the trees are valuable.

The pandemic underscores the need to reduce reliance on ecotourism jobs and create other employment opportunities to alleviate the poverty driving illegal behavior, she says.

Louis agrees. He suggests that existing businesses—the manufacture of essential oils and aromatherapy products, as well as the production of vanilla, coffee, and mangos—should be further developed and organized into consortiums.

But to protect lemurs and help preserve Madagascar’s remaining wilderness, the most urgent need is to bring the pandemic under control, he says. Reforestation will remain a priority to replace what’s been lost—reconnecting fragmented lemur habitat and expanding buffer zones around protected areas.

“We need to make local communities self-sufficient in terms of food security and health security,” Andriamanana says. “If we don’t have that, then they will always tap into the forest.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

First Case of Covid-19 in a Wild Animal Found in a Utah Mink

https://sciencespies.com/news/first-case-of-covid-19-in-a-wild-animal-found-in-a-utah-mink/

First Case of Covid-19 in a Wild Animal Found in a Utah Mink

According to an alert released by the U.S. Department of Agriculture on Monday, the department’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service has detected the first case of a non-captive animal infected with the coronavirus that causes Covid-19: a wild mink in Utah near a fur farm with an active virus outbreak, Lee Davidson reports for the Salt Lake Tribune.

The survey did not conclude how the wild mink became infected with the virus, but it’s not unusual for captive minks to escape fur farms, and the virus isolated from the wild mink was indistinguishable from virus circulating in the farm. The mink was the only wild animal carrying the virus amid ongoing testing of several species that live near the farm, including raccoons and skunks, Dina Fine Maron reports for National Geographic.

Concern over minks’ ability to escape from farms prompted fur farms across Europe to cull their mink populations. But despite outbreaks at 16 U.S. mink farms across four states, the USDA has not announced its strategy to prevent farm outbreaks from reaching wild populations.

“Outbreaks at mink farms in Europe and other areas have shown captive mink to be susceptible to SARS-CoV-2, and it is not unexpected that wild mink would also be susceptible to the virus,” says USDA spokesperson Lyndsay Cole to National Geographic, referring to the coronavirus that causes Covid-19. “This finding demonstrates both the importance of continuing surveillance around infected mink farms and of taking measures to prevent the spread of the virus to wildlife.”

Beyond minks, animals ranging from like dogs and house cats up to predators like lions, tigers and snow leopards have tested positive for the coronavirus that causes Covid-19. Scientists in the Netherlands found the first evidence of the virus in mink fur farms in May, and the disease reached fur farms in the U.S. in August.

The European fur industry has culled over 15 million minks across the Netherlands, Denmark, Spain and Greece in an effort to stymie opportunities for the virus to mutate, halt spread of the virus from minks to people working at the farm, and prevent the minks from escaping and passing the virus to wild animals.

“There is currently no evidence that SARS-CoV-2 is circulating or has been established in wild populations surrounding the infected mink farms,” writes the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) in the alert.

Critics of the fur farming industry point to the case as an example of why the industry should be closed, because it is now not only an animal welfare issue—the minks are housed in crowded conditions and their genetic similarity make them prone to disease—but also a danger to wildlife.

“Scientists have worried that the coronavirus would be passed from escaped factory farmed mink to wild mink,” says Lori Ann Burd, director of the Center for Biological Diversity’s environmental health program, to the Salt Lake Tribune. “Given the risk that this nightmare scenario is unfolding in Utah, we urge officials in every state with mink farms to take aggressive measures to ensure that this horrible disease does not decimate wildlife populations.”

The Fur Commission USA, which is the primary fur trade organization in the United States, is supporting efforts to develop a vaccine to protect minks from coronavirus infections. And Mike Brown, a spokesperson for the International Fur Federation, tells National Geographic that U.S. fur farms follow “strict biosecurity protocols.”

The case rases concerns that the virus may be able to spread among wild, non-captive mink populations, says University of Surrey veterinary expert Dan Horton to BBC News’ Helen Briggs. He adds that it “reinforces the need to undertake surveillance in wildlife and remain vigilant.”

Like this article?

SIGN UP for our newsletter

#News

0 notes

Quote

BREAKING: First wild animal confirmed with covid. USDA testing says a free-ranging, wild mink sampled in Utah has tested positive for coronavirus. It's the same strain of covid found in the farmed mink in that area.

— Dina Fine Maron (@Dina_Maron) December 14, 2020

0 notes

Text

Alexander the Great's surprising battlefield decision proved pivotal for facial hair norms that lasted hundreds of years. Photograph By Bridgeman Images

Beards and Mustaches Have a Weirder History Than You Think

No-Shave November may be a modern phenomenon. But our love-hate relationship with beards and mustaches dates back to the days of Alexander the Great.

— By Dina Fine Maron | November 7, 2023

More than 2,000 years ago, as Alexander the Great’s troops prepared for a pivotal battle over Asia, the famous Macedonian commander learned that his troops were outnumbered by at least five to one. To help assuage some of his force’s anxiety, Alexander issued an unusual order—his troops needed to shave. Why? It was too easy, he said, for their foes to grab Macedonian beards.

The move, coupled with Alexander’s surprising success on the battlefield, fueled a trend in beardlessness among Greek and Roman men that endured for the next 400 years, according to historian Christopher Oldstone-Moore, who wrote the 2015 book Of Beards and Men: the Revealing History of Facial Hair.

This tweezer-razor made of bronze or copper alloy and crafted more than 3,000 years ago in Egypt, was found in a coffin in the tomb of Neferkhawet, a scribe who lived around 1500 B.C.

The razor of Amenemhat, the father of Neferkhawet, made of similar materials, was found in the same tomb in the mid-1930s. Photographs By The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1935

Alexander’s wartime decision was really a turning point for facial hair, says Oldstone-Moore, who is himself currently clean-shaven. “The history of men is literally written on their faces,” he writes in his book. Indeed, long before modern movements like No-Shave November or Movember were founded to raise awareness for cancer research and other causes, trends in men’s facial hair have waxed and waned alongside the societal significance of being clean-shaven, whiskered, or mustachioed. Men’s personal grooming, according to historical books and peer-reviewed studies, extends across art, politics, and even into the court room. Much of that work to date focuses on European and American trends, though beard choices have long been meaningful to communities and religions around the world, signaling, among other things, religious piety for Muslims and Jews.

Shaving facial hair dates as far back as the Sumerians and Egyptians, who used razors made of copper or bronze. Generally, however, most men in ancient times favored beards and it was considered arduous and sometimes also unsafe to shave. Still, for most men it wasn’t about being “too lazy to shave,” either then or now, says Oldstone-Moore, an emeritus lecturer at Wright State University, in Ohio. “Fashionable men would still have to go to barbers and have their beards cared for properly, and they’d have oils and combs and that sort of thing.”

The Regal Power of Facial Hair

Facial hair has often been equated with masculinity and related patriarchal power, but that hirsute power is sometimes transferrable: Notably, Pharaoh Hatshepsut (ca 1508– 1458 B.C.) donned an artificial beard when she ruled Egypt for more than two decades. Egyptian kings had previously fashioned themselves in stylized ways, with wigs and crowns and artificial decorative beards, Oldstone-Moore notes, so Hatshepsut’s beard was aligned with her predecessors’ sartorial customs.

Hatshepsut (ca 1508– 1458 B.C.) wore an artificial beard when she ruled Egypt, but her male predecessors had already normalized wearing decorative beards. Photograph By Rogers Fund, 1931, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Beards were later of such import that Shakespeare explicitly mentions them in all but four of his plays, notes historian Will Fisher in the journal Renaissance Quarterly in 2001. Moreover, he writes, analysis of a collection of about 300 portraits of European men from the 1500s and 1600s indicates that for every portrait of a man without a beard, there were about 10 portraits of men with beards. Styles of the time included the thin, angular “stiletto,” a fuller “square cut,” and even a double-tufted “swallowtail.”

Can Facial Hair Make You Sick?

Ideas about the significance of men’s beards have made it into medical books. Growth of facial hair, Renaissance physicians wrote, was explicitly tied to the production of semen, an idea presaged by classical Greek scientists who theorized that men have “vital heat” which explains their size, strength, and hairiness. According to this false theory, both sexes produce this vital heat, which then gives rise to semen, yet women’s bodies aren’t equipped to handle significant amounts of it.

By this way of thinking, Oldstone-Moore writes, only a man’s body could survive growing a beard. In classical Greece, people believed if a post-menopausal woman grew some facial hair, sickened, and eventually died, she simply had an unnatural buildup of semen, and facial hair was a symptom of that underlying issue.

Adding another layer to that theory, German abbess Hildegard of Bingen, around the year 1160, offered that the reason facial hair occurred exclusively around the mouth—rather than, say, on the forehead—was because of men’s hot breath. Women, according to Hildegard’s writings, wouldn’t have breath that was as hot as a man’s because men were formed from the “earth,” whereas females were formed from men, she then explained, tying her thinking back to creation ideology.

By the 1700s, when shaving once again became de rigeur and it was considered respectable and gentlemanly to shave, the phrase “clean-shaven” took hold. In the nineteenth century, Louis Pasteur’s germ theory also further shored up medical support for shaving: Facial hair, doctors warned, was a microbe haven. Indeed, one French scientist noted in a 1907 experiment that the lips of a woman kissed by a mustached man were “polluted with tuberculosis and diphtheria bacteria, as well as food particles and a hair from a spider’s leg.” A study in the Lancet around that same time also concluded that shaven men were less likely to develop colds. The work argued that soap could be more effective on a hairless face, according to Oldstone-Moore.

King C. Gillette patented his famous safety razor in the U.S. in 1904. Employers at the turn of the century expected their workers to be clean-shaven. Photograph By Bettmann, Getty Images

This Gillette safety razor, photographed with its original box, was from the 1930s, when shaving cream and equipment fueled millions of dollars in sales in the United States annually. Photograph By Science & Society Picture Library , Getty Images

Workplace Norms and Controversies

Workplaces in the early 1900s and onward also regulated facial hair and instituted requirements for its male workforce to shave as a key sign of professionalism and cleanliness. Relatedly, in 1904, King C. Gillette patented his safety razor in the U.S. and by 1937, Oldstone-Moore writes, shaving cream and related accessories had estimated sales of $80 million in the U.S. alone. (Related: See these world beard and mustache champion photos.)

Facial hair controversies also rose to the highest court in the land: A U.S. Supreme Court case in 1976, Kelley v. Johnson, even upheld an employers’ authority to dictate grooming standards for their employees. In that case, policemen of Suffolk County, New York, had taken issue with workplace standards that barred them from growing hair below their collars or facial hair except for a neatly trimmed mustache that didn’t extend onto the lip. The county successfully argued that these grooming regulations made police recognizable to the public and contributed to the cohesiveness of the force. In the years that followed, that case precedent was further applied to school employees and other workers across the country.

More than a dozen years after the Supreme Court ruling, in 1992, Massachusetts police officers pushed back against a statewide ban on facial hair among its officers. They, too, lost.

In more recent years, however, despite those standing court rulings, western facial hair norms have shifted, and employers have largely pulled back from stringent regulations, at least informally.

“Beards or facial hair of some sort often come back when gender or masculinity are being somehow debated,” says Alun Withey, a historian at the U.K.’s University of Exeter and author of the 2021 book Concerning Beards: Facial Hair, Health and Practice in Britain, 1650-1900. “Today there are multiple debates and challenges surrounding concepts of gender and the body, so perhaps the recent beard trends in part reflect this,” he says.

With increased facial freedom, a variety of personal grooming choices have now taken hold. But purveyors of men’s shaving and personal grooming equipment are not hurting—market analysis from June 2022 indicates that instead of razors, men are now instead investing more in electric trimmers.

0 notes

Text

The spotless giraffe, born at a Tennessee zoo, is the first one seen in more than 50 years.

By Dina Fine Maron

24 August 2023

Just a few weeks old and still without a name, a newborn giraffe at a zoo in northeastern Tennessee could rightly be nicknamed “spotless.”

The female giraffe born without its characteristic spots instead boasts a solid brown coat, a phenomenon that hasn’t been observed in any giraffe for more than 50 years.

She was born last month at Brights Zoo, a family-owned facility in Limestone, Tennessee.

A spotless giraffe was last reported at a Tokyo zoo in 1972.

“The spotless giraffe calf is certainly an interesting case and that type of coloring has never been seen in the wild," says Sara Ferguson, a wildlife veterinarian and conservation health coordinator at the Giraffe Conservation Foundation.

The animal’s rare coloring is likely due to some sort of mutation in one or more genes, she says.

But there’s no indication of underlying medical issues or that the newborn reticulated giraffe — a subspecies native to eastern Africa — is at a genetic disadvantage.

David Bright, zoo director at the Brights Zoo, says that the baby’s nine-year-old mother, Shenna, had previously birthed three other calves and the trio were all spotted.

This latest addition to the zoo’s giraffe family was born at a weight of around 190 pounds, he says, and her veterinary care team concluded “she’s healthy and normal” — though her coloring was a surprise.

A case of spotlessness

Genetics often influence animal coloring in diverse ways.

Giraffes with all white coloring have previously been spotted in the wild, including two at a reserve in Kenya in 2017.

Those animals had a genetic condition called leucism, which blocks skin cells from producing pigments.

"There’s no known explanation for the spotless giraffe in Tennessee beyond that it’s almost certainly due to some kind of genetic mutation or mutations," says Fred Bercovitch, a wildlife conservation biologist at the Anne Innis Dagg Foundation, a nonprofit that focuses on giraffe conservation.

The last known case of a spotless giraffe was an animal named Toshiko born in 1972 at Ueno Zoo in Tokyo, Japan, CBS News reported.

That giraffe’s mother had birthed another spotless calf several years earlier, according to Bright.

The Brights Zoo, which is home to just over 700 animals of 126 different species, including nine giraffes, asked the public to vote on four potential names for the giraffe calf on its Facebook page.

It accrued over 17,000 votes in the first day, Bright says.

There are four candidate names, all in Swahili: Kipekee (unique), Firyali (extraordinary or unusual), Shakiri (she is most beautiful), and Jamelia (one of great beauty).

What’s in a spot?

A 2018 study published in the journal PeerJ found that certain aspects of giraffe spots are passed down from mother to calf, such as how round the spots are and their smoothness (which is technically referred to as “tortuousness”).

The study authors also noted that bigger, rounder spots seemed linked to higher survival rates for young giraffes.

Still unanswered, however, was if that was possibly due to better camouflage or other unknown factors like enhanced ability to regulate temperature.

Bercovitch, who wasn’t involved in that study, says he wouldn’t be concerned about the spotless giraffe’s health even if the giraffe was born in the wild and away from a zoo’s medical care.

“Among mammals, the fur and the hair are the primary features that assist in thermoregulation, not the color of the fur,” he says.

“Giraffes can regularly raise their body temperature by a few degrees … they don’t sweat,” he says.

“That’s one of the reasons you find giraffes under trees—they want to keep their body temperatures within certain limits.”

Even the lack of camouflage wouldn’t necessarily mean the giraffe would be at a disadvantage in the wild, he says, since the mortality rate for young giraffes from lion predation is already so high.

Ferguson, the wildlife veterinarian says she looks forward to hearing more about the giraffe in the years to come.

“What would be cool,” she says, “would be to take an infrared light photo or a thermograph of her to see if the spot pattern is still there but invisible to our eye.”

🤎🦒🤎

#giraffe#Brights Zoo#Sara Ferguson#Giraffe Conservation Foundation#reticulated giraffe#Shenna#leucism#spotless giraffe#Fred Bercovitch#David Bright#Anne Innis Dagg Foundation#Toshiko#Ueno Zoo#Tokyo#PeerJ#wildlife#animals#zoo#Nat Geo#National Geographic

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coronavirus Fears Impact Cash

By Richard Giedroyc

Talk about dirty money! What about money laundering? Fear of the coronavirus epidemic spreading worldwide is resurrecting the urban legend about how germs on our physical money may be making us sick.

At the time this article was being written no one yet knew for certain how the coronavirus (officially known as COVID-19) is spread. It was known the disease can be passed person to person, but if the spread is generated through breathing the same air, touching an infected person, touching bank notes the infected person used, or some other mechanism is yet to be learned.

It has been verified the disease is zoonotic, having been initially spread from animals to humans at an illegal live animal market in Wuhan, China. The market has since been shut down by authorities, but not before the virus had spread. Since that time travel between China and the rest of the world has been limited in an effort to contain spread of the disease. Travel within China has also been limited for the same reasons.

The coronavirus and its possible connection to physical cash is grabbing all sorts of headlines. Many of these headlines ignore the World Health Organization’s official statement: “The risk of being infected with the new coronavirus by touching coins, bank notes, credit cards, and other objects is very low.” The WHO website repudiates several myths surrounding money and germs found on it.

This hasn’t stopped the media from pointing out just how many germs lurk on our money. A Feb. 18 International Business Times article pointed to a 2013 study that identified E.coli, Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE), and Staphylococcus on bank notes “with bacteria survival rates being the highest in the Romanian Leu,” while acknowledging “they [bank notes] do not easily pass diseases to people.”

The Oct. 2, 2018 Moneywise.com post reads: “If you haven’t ditched cash in favor of a card or contactless yet, you might want to think again. New research from London Metropolitan University and financial website Money.co.uk has revealed that the cash in your pocket could be home to life-threatening bacteria such as MRSA and listeria.”

Money.co.uk Editor in Chief Hannah Maundrell was quick to throw gasoline on the fire, stating: “We were really shocked when the results revealed two of the world’s most dangerous bacteria were on the money we tested…These findings could reinforce the argument for moving towards a cashless society and might be the nail in the coffin for our filthy coppers. I suspect people may think twice before choosing to pay with cash knowing they could be handed back change laced with superbugs.”

A Jan. 3, 2017 article by Dina Fine Maron appearing in Scientific American is one of many articles that isn’t charitable to cash, suggesting “Perhaps all money should be laundered.”

The Scientific American article concedes, “There is no definitive research that connects enough dots to prove dirty money actually makes people sick, but we do have strong circumstantial evidence: influenza, norovirus, rhinovirus, and others have all been transmitted via hand-to-hand or surface-to-hand contact in studies, suggesting pathogens could readily travel a hand-money-hand route. In one study 10 subjects handled a coffee cup contaminated with rhinovirus—and half subsequently developed an infection.”

Cashless society proponent Kenneth Rogoff, the author of The Curse of Cash, suggests health is one of the reasons countries such as Sweden have been abandoning physical cash in favor of electronic payment systems.

In an effort to curb the spread of coronavirus, on Feb. 15 the Guangzhou branch of China’s central bank announced banks must disinfect all bank notes before the notes are distributed. An order was also given instructing all bank notes from high-risk areas such as banks, buses, and wet markets be destroyed.

People’s Bank of China Vice Governor Fan Yifei said China’s money supply will not be disrupted, with 4 billion yuan (about $572 million USD) in new bank notes already allocated to Hubei province. Fan said the central bank will temporarily store bank notes from major government institutes and state enterprises in warehouses to prevent the disease from spreading through handling cash.

According to Fan the central bank is encouraging people to use online banking services, e-shopping, and online utility payments. Fan added he is certain the epidemic will not cause any significant inflation since the government is managing cash flow and the supply of commodities.

China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission Vice Chairman Liang Tao added the banking system has set 537 billion yuan (about $76.8 billion USD) aside to provide credit support for domestic businesses and government institutions to fight the epidemic. Banks have also been instructed to postpone business loan repayments.

Despite China’s actions and the statements from the WHO on Feb. 19 the Bank of Korea, South Korea’s central bank, announced it was no longer accepting foreign coins and bank notes in an effort to avoid spreading the coronavirus. The Bank of Korea also closed its currency museum “as a precaution.”

More recently it was announced the Eighth Hong Kong Coin Show has been postponed from March until August. What else will follow?

The post Coronavirus Fears Impact Cash appeared first on Numismatic News.

0 notes

Text

Woolly mammoths are extinct. Here’s why they may be considered ‘endangered.’

Woolly mammoths are extinct. Here’s why they may be considered ‘endangered.’

A global summit on the wildlife trade will consider

the proposal, which could further restrict the ivory trade.

By Dina Fine Maron

One of the most surprising proposals under discussion at the giant global wildlife trade treaty meeting in Geneva, Switzerland, is about woolly mammoths—creatures that once wandered huge tracts of North America, Europe, and northern Asia—and went extinct more than…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Thailandia

Morte 86 delle tigri sequestrate nel Tiger Temple

Si trovavano sotto la custodia del governo dal 2016. Tra le cause di morte ufficiali, endogamia e patologie contratte durante la permanenza al tempio

di Dina Fine Maron

0 notes