#Pelagonia

Text

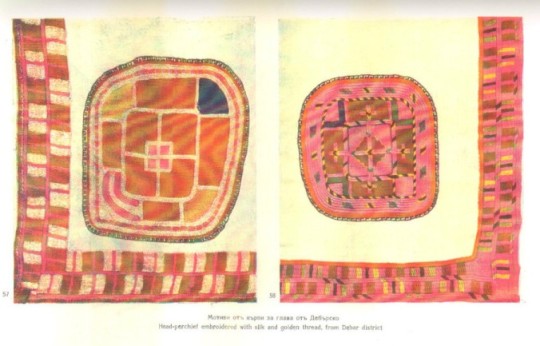

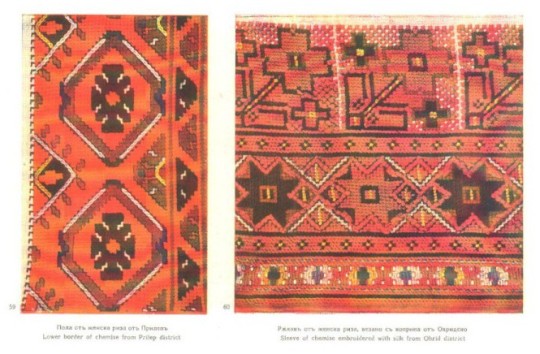

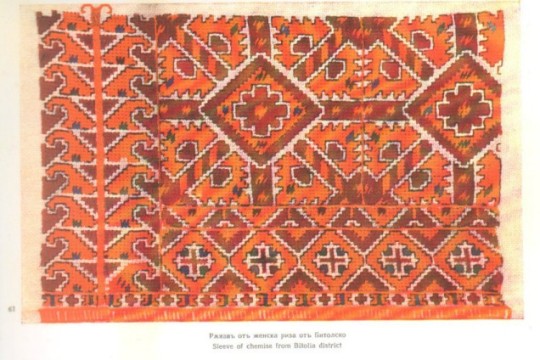

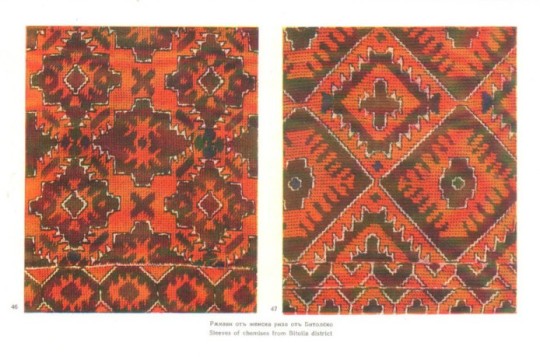

Examples of embroidery on traditional clothes from Vardar (North) Macedonia. | Везани части от носии от Вардарска Македония.

I. 57, 58 — Headkerchiefs embroidered in silken and golden thread, region of Debar. | Мотиви от кърпа за глава, Дебърско.

II. 59 — Hem of a chemise from Prilep. | Пола на кошула, Прилепско. 60 — Sleeve of a chemise with silk embroidery, Ohrid. | Ръкав от кошула, везана с коприна, Охридско.

III. 61 — Chemise sleeve from Bitola. | Ръкав от кошула, Битолско.

From the Album of Bulgarian Macedonian Embroideries by Raina Roumenova.

#Macedonia#Vardar Macedonia#folk clothing#embroidery#chemise embroidery#album images#Debar#Prilep#Pelagonia#Ohrid#Bitola

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why do you think it took Alexander such a long time to *actively* go about making an heir? I understand that marriage in the early 20's was uncommon but that for him it was especially undiplomatic to tie himself down to one particular faction at court at the start of his reign. His father himself was very quick to marry into peace. Why did it take Alexander so long to address that issue? He could have officiated his union with Staitera whenever. Or had anyone he wanted at 25 after Issus.

First, I've been preparing for, then in New York for some cool things I'll talk about later. But it's slowed down my answers. (Now, I have to catch up for the time spent preparing, so I'll still be slow.)

Argead Inheritance and Alexander’s (lack of) Heirs

A lot of historians have asked why Alexander didn’t marry earlier and put off producing an heir. My own answer involves what I think were some unrecognized attempts mixed with bad luck. To really understand, however, we have to look at the behavior of prior Macedonian kings, and how the Argead Dynasty understood succession. Buckle-up Buttercup, this is a longer one. 😊

Let’s begin with Philip (II) and his older brother Perdikkas (III), the only two prior kings whose ages of first marriage we know or can reasonably guess. Let me also preface it by saying that while prior Macedonian kings sometimes had more than one wife, nobody had seven.* (The most I’m aware of are two, maybe three.) Philip’s military and political success led to an expansion on royal marriage in Macedon.

Perdikkas III ruled c. 5 years. We’re unsure how much older he was, but 2-3 years and possibly more. At his death, he had a son about a year old (Amyntas). We don’t know the name of Perdikkas’s wife, or when he married, but he was married at least 2 years. At his death, he would have been 25-30, probably closer to 30. My guess is he married after coming to the throne (for reasons I’ll skip as this is already long enough).

Philip married 5 times in his first 5-6 years; all were political. He was c. 23/24 when he came to the throne. For his first marriage, he wasn’t given much choice. Like Beth Carney, I consider Audata the first wife (not Phila), and he married her as part of a deal with Bardylis to prevent all-out invasion of Upper Macedonia following his brother’s death (along with half the Macedonian army) on a battlefield in Lynkestis. That marriage made him a client king.

This marriage may explain his rapid second marriage to Phila of Elimeia (independent kingdom until Philip). He probably contracted it shortly after to get the skillful Elimeian cavalry, et al., on his side for a second go at Bardylis just the next year. No grass grew under Philip’s feet.

In addition, Bill Greenwalt has proposed that Philip and Olympias were betrothed some years prior by their brother and uncle, respectively, when she was still a girl and he was in his teens—a backroom alliance against the threat of Bardylis. Obviously, it didn’t save Perdikkas. In 360, she still wasn’t old enough to bring to Pella, nonetheless, the alliance existed. Philip already had Lynkestis via his mother Eurydike. And—if Parmenion really was from Pelagonia—he also had that kingdom, if not via marriage/family. That’s a solid border against Illyria. (See map)

So, his first marriages/betrothal were driven by a need to deal with Illyria. His next marriages, a few years later, reflected a need to settle matters in Thessaly on his southern border. Marriage for him was all about securing the Macedonian borders. Those five marriages produced five surviving children from four wives—two of them boys.

He doesn’t marry again for almost a decade, and then it’s to settle matters in northern Thrace.

The last marriage, whatever our sources say, was also almost certainly political, but this time to address apparent internal conflict. We’re not sure what that was; it’s been lost to layers of drama involving Alexander and Olympias, but it probably owed to tension between Upper and Lower Macedonia—which hadn’t been united all that long.

So, Philip’s marriages were politically driven. He got children out of them, but that wasn’t the driving reason for him to marry—except possibly the last. Internal conflict or not, he may also have married again to father a “backup” heir, in case he lost Alexander and/or Amyntas in Persia (more below).

That’s the view of [royal] marriage Alexander grew up with: Macedonian kings marry for politics…not necessarily to secure heirs.

We must also review the crazy method of Argead inheritance.** ANY Argead male could hold the throne. There was a preference for the son of the prior king, or at least a prior king. There also seems to have been a preference for a son by the higher/highest status wife. Yet because any Argead could hold the throne, virtually no Argead king went unchallenged either at the beginning of, or sometimes later in his reign.

Supposedly, on his deathbed, when asked to whom he left his kingdom, Alexander replied, “To the strongest.” That pretty much sums up Argead inheritance.

For this reason, underage Macedonian heirs/kings usually didn’t live/rule long. The one “infant king” tale comes from an era before we have a surviving historical record to know how long he reigned, or if it were all legendary. The list of Macedonian kings before Amyntas I, father of Alexander I, may be semi-mythical, like early Roman kings. See image…helpfully numbered (by me). Stemma itself from In the Shadow of Olympus, E. N. Borza.

Alexander I (Persian Wars) had five living sons. The line of inheritance went through the third, Perdikkas II (Peloponnesian War era), then down to Archelaos…after that, things get a bit crazy until Amyntas III (Philip’s father). He descended from Alex I’s youngest son, which established a new line that lasted until Alexander IV. But in that time, because of the somewhat laissez-faire attitude towards who could inherit, we have a lot of internecine battles every time a king died, which thinned the herd.

The arithmetic of high infant mortality plus death in war meant Macedonian kings needed an “heir and a spare, and the spare’s spare.” Philip had that after his first spate of marriages: Alexander, Arrhidaios, and Amyntas (his nephew). That Arrhidaios was unfit became apparent only over time, but was still good to father sons.

When, post-Chaironeia, Philip prepared to invade Persia, he made a spate of royal marriages first. Arrhidaios’s betrothal was meant to get an Asian bridgehead/ally, but fell through thanks to Alexander’s meddling. Amyntas was given his cousin Kynnane, who wound up pregnant quickly. That turned out to be a girl, but it proved both were fertile: more children to come. This marriage may also have been a sop to keep Amyntas loyal. Kleopatra was married off to the king of Epiros to solidify one of Macedon’s closest allies and alleviate any insult to Olympias at Philip’s own final marriage.

As for that wedding, in addition to any internal politics, it gave him opportunity for another son. He had to consider the possibility that he could lose both Alexander and Amyntas in combat, and perhaps even himself, if it all were to go south. Arrhidaios was a stop-gap. An infant son back home could eventually take the throne.⸸

Yet the one person he does NOT prepare nuptials for? Alexander.

Why? He almost certainly planned to marry him to one of Darius’s daughters. He admitted as much when he dressed down Alexander for having offered himself to marry Pixodaros’s daughter in Arrhidaios’s place. That would have made an impression on Alexander, perhaps in shame: he was meant for royalty only.

When Alexander ascended the throne, he owed it to the support of the two most important men in Macedon: Antipatros and Parmenion…who, if not open enemies, each had their own factions. Both had eligible daughters, but to avoid giving one side too much power, he’d have had to marry both, or none at all.

OR, as Tim Howe has suggested, he might have decided to marry his father’s young widow.

It wouldn’t have been the first time in Macedonian history. And it explains, oh, so much better, why Olympias killed Kleopatra-Eurydike. Keep in mind, Kleopatra-Eurydike’s new husband was dead and she’d delivered only (another) girl mere days earlier. Olympias may have enjoyed her discomfiture at being sidelined more than her death.

Unless Alexander decided to marry her. She was almost certainly younger than him, and had proven fertile. Maybe he saw the marriage as a way to further solidify support. But it would have challenged Olympias’s status. I don’t know that’s what happened, but Tim makes a good case, and her decision to kill the girl to remove the threat then becomes intelligible rather than just bloodthristy.

When Mommy Dearest eliminated the option, young Alex was back to square one. Marry a daughter of Antipatros and of Parmenion, or stay unmarried. He chose the latter.

Yes, it left no heir to the throne (other than Arrhidaios), but he didn’t have any good options that weren’t also a potential political grenade. And unlike his father’s situation in 359/8, marriage wasn’t foisted on him. He could wait a few years, so he did.

But after Issos, the Persian royal family came into his possession, and by this point, he was 24, the same age his father had been at his first marriage. Pressure began to mount. Here were all these pretty Persian ladies…. PICK ONE. It wouldn’t have been just Parmenion saying so.

There’s been some recent speculation that he married Barsine, didn’t just take her as a mistress. While possible, I’m not sure it’s probable. She came with a lot of baggage for a first marriage. Making her his mistress, especially if a palakē, provided her with a respectable, recognized status, but still left the door open for a first marriage because….

As the asker alludes to, he almost certainly also bedded Statiera, Darius’s wife. Why marry the pony horse when you can have the racehorse? Oh, oops. She’s still married because her husband is still alive. How inconvenient.

So why didn’t he just declare her divorced and make it official?

Politics. However much he didn’t really understand Persian affairs of state, he understood optics, and general human reactions. Greeks and Macedonians would want him to bed the queen because that’s the ultimate piss-in-the-eye of the Other Guy. But after Issos, Alexander was hoping to bring other satraps over to him. By not touching Statiera or her daughters—at least at first—he presented himself as civilized and respectful. He even offered Darius his family back, on one condition. Surrender. Darius had to come as a suppliant to ask for them.

Of course, Darius refused. Nor did Alexander expect him to agree, but the required dance had been performed. When Darius began soliciting a new army, the tacit message was, “You can have the women.” ⸸⸸

While all these negotiations took place, Alexander had Barsine. Keep in mind, the letters would have taken weeks, probably months. The number of letters is unclear, but probably two each. The final exchange occurred sometime in the seven months of Alexander’s siege of Tyre.

Why do I say he was bedding Statiera, and (probably) planned to marry her? After all, Plutarch is adamant he was too chivalrous even to look at her again after their first meeting! Well, Plutarch also tells us—without apparent irony—that Statiera died in childbirth along with an infant son just a few weeks before Gaugamela…which was two years after Issos. That sure as hell wasn’t Darius’s kid. And no, nobody else would have been allowed to touch her. Plutarch lied. Why? It’s all part of his honorable “Sleep-and-sex-remind-me-I’m-mortal” Alexander. It’s also Plutarch who turns the marriage of Roxane into a “love-at-first-sight” affair.

In any case, I think Statiera was another marriage that Alexander planned, but fate prevented.

If we count back 40-or-so weeks from her death in mid-September of 331, that puts us in December of 332. Alexander had entered Egypt in November. It’s doubtful she accompanied him on the trek to Siwah, so his opportunities for impregnating her were at the beginning of his Egyptian stay, or towards the end. Keep in mind that while we know she died in childbirth, we don’t know if it was full term. Accounting for Siwah, she was probably either nine months or seven months along. As for when he started sleeping with her, probably any time after the final exchange of letters with Darius.

In the spring of 331, he left Egypt to return to Tyre before moving inland to find Darius. It may be here that he retired Barsine, sending her off to Pergamon (in Asia Minor). If that’s the case, Herakles definitely wasn’t his, as the boy was born some years later. In any case, by the time Alexander left Tyre, Statiera probably knew she was pregnant and would almost certainly have told him.

I think he held off marrying her until he could meet Darius again in battle (and kill him), which he assumed immanent. Yet the Macedonians had no concept of how big the interior was. And Darius wanted to draw Alexander onto the plains of northern Iran—but not too fast. He burned fields in front of the Macedonians partially, intending to leave them with enough food to continue, but not enough to fill bellies. He assumed a hungry army would be insubordinate, but underestimated both Macedonian discipline and Alexander’s scouting and intelligence. By September, Alexander had finally caught him up east of ancient Nineveh across the Tigris.

Then Statiera went into labor and died. BOOM, Alexander’s marry-the-wife plan fell apart for a second time, and he lost a potential heir in the process. Did a lack of food contribute to her death? Maybe. She’d had at least 3 healthy children, but was also in her mid/late 30s, possibly early 40s. Lack of food or not, an army camp would hardly be easy on an older woman in late pregnancy. (Had my first at 33; I can speak to that.)

But!, you may be wondering, even if Statiera had lived and Darius had died (as was Alexander’s ostensible plan), wouldn’t a baby born before marriage have been a bastard? Wouldn’t matter. First, given the cloistering of highborn Persian women, it’d be easy enough to lie about such things. Second, bastard or not, the child was still an Argead.

It would also explain why he didn’t marry immediately after Issos—nor after Gaugamela. Plan A died in the birthing bed, and Plan B, the daughters, were too young yet. Furthermore, it wasn’t over at Gaugamela. He’d have to chase Darius further….

He dropped off the girls in Susa for safe-keeping and went after Darius. Again, we must recall, he had no idea how long this would take. He probably assumed he’d be back in Susa in a year or so. Instead, he wouldn’t see Susa again for six.

In 327 (c. 3.5 years later). he finally decided to marry—for political reasons: to achieve peace in Baktria. Now pushing 30, and given how long everything had taken, he chose not to put it off any longer; he could always marry the princess later. Ironically, this marriage was not well-received by the army, although it wasn’t much different from his father’s marriages. Then again, we have no idea how Philip’s marriages were received at the time. I doubt the army was thrilled to have an armor-wearing, battle-trained Illyrian princess as Phil’s first bride.

Whatever the case, Alexander had a wife and, if we can trust the Metz Epitome, he lost little time getting her pregnant. But she miscarried (again, perhaps a boy). He just wasn’t having much luck fathering living children…perhaps because he kept dragging his women through tough conditions. One had a geriatric pregnancy and the other was probably 14-16: neither optimal ages.

In any case, as soon as he was back in Susa, he planned the mass weddings, at which he finally married Darius’s daughter, Barsine, as well as Parysatis, Barsine’s cousin. Within a year, he had both Roxane and Barsine pregnant, if not Parysatis.

So, we have to shed the moralizing of Plutarch’s narrative and evaluate what was really going on. Alexander may not have married till 29, but he probably angled for it at least once (Statiera) and possibly twice (Kleopatra-Eurydike) before that. Should he have stopped aiming for queens and just married a nice girl to pop out babies? Well, that’s essentially what he did with Roxana. Maybe he should have started there, back in Macedonia before he left, but he didn’t, and at 22, it wasn’t a shocking choice.

Yes, Macedonian kings certainly worried about heirs, but to produce an heir was not the primary way Philip, or Alexander, used marriage. It served political goals first, inheritance second.

———————

* To be fair, he didn’t have seven at the same time. We know one (Nikesepolis, Thessalonike’s mother) was dead before Philip married Meda (#6), and it’s quite possible the mysterious Phila of Elimeia (#2) also died young. At the time of his death, we can be sure only of Olympias and Kleopatra-Eurydike, although at least some of the others were likely still around. My guess is there were four-to-five wives in the women’s quarters in 336. (In Dancing with the Lion, there are four: Philina, Olympias, Meda, and Kleopatra-Eurydike.)

** An almost prohibitive amount of scholarly debate, most in article/book-chapter form, concerns whether or not Macedonia had a “constitutional monarchy,” and what—if any—say the army had in choosing a king. While some constitutionalists remain (M. Hatzopoulos most notably), these days the bulk of scholars (not in Greece) favor a position of “nomos” (custom) but no formal rules. For a bibliography of the debate, at least up through 2002, see Carol King’s chapter in Brill’s Companion to Alexander the Great (Roisman, 2003). A new Companion from Cambridge, edited by Daniel Ogden, is currently in the works, probably out in 2023, which will likely update the state of the scholarly conversation.

⸸ This is more or less what the army demanded at Alexander’s death: Arrhidaios for now as Philip III, along with infant Alex IV, who’d presumably go on to reign alone when of age. But by that point, ambitious generals were happy just to end the Argead Dynasty altogether and form their own. Like most underage Macedonian kings, Alex IV’s days were numbered, even as the last Argead. Once, the gloss of divine descent from Herakles might have saved him, but the Diadochi had grown too jaded—and too successful. They all thought themselves equally worthy.

⸸ ⸸ By ancient criteria, if a man surrendered his kingdom “just” to get his wife and children back, it would automatically tag him unfit to be king. Yes, even in Persia, where women had higher status overall. In the ancient near east, nobody’s life was more important that the king’s. Statiera would have been well aware of that, so Darius’s ‘betrayal’ was to be expected. In fact, she might have despised him if he’d agreed.

#asks#roxane#statiera#alexander the great#macedonian royal polygamy#ancient macedonia#alexander the great and marriage#kleopatra-eurydike#classics#tagamemnon

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

North Macedonia secures funding for first major investment in waste management

North Macedonia has launched its first major investment in the modernization of infrastructure for solid waste management in line with European standards. The project will cover more than one million inhabitants in five regions: South-East, South-West, Pelagonia[1], Polog[2], and Vardar[3].

The waste management project will be financed with a loan from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD)[4] in the amount of EUR 55 million, and donations from various international and governmental institutions. It will be implemented by the Ministry of Environment and Physical Planning[5].

During its implementation, three regional integrated systems for waste management will be established, putting a stop to depositing at aging local landfills, with environmentally safe disposal practices to be introduced in line with EU standards.

According to the EBRD, the project envisages the construction of new and rehabilitation of existing sanitary landfills, the construction of new transfer stations, infrastructure for waste collection and transportation, and a recycling centre, as well as the closure of two landfills.

The project should be supported with investment grants of EUR 24 million and technical assistance estimated at EUR 13.1 million. The donors are the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs[6] (SECO), the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency[7] (SIDA), and the Western Balkans Investment Framework[8] (WBIF).

SECO’s financial support of EUR 9 million will go towards completing the rehabilitation of the Polog landfill (EUR 6 million) and the development of institutional frameworks at the regional and local level in the solid waste sector (EUR 3 million).

SECO will also fund assistance for the Energy and Water Services Regulatory Commission[9] to expand its mandate in the waste sector.

The project is also expected to receive support from the WBIF in the amount of up to EUR 22.3 million, and assistance worth EUR 2 million for the development of studies in the two regions. Swedish SIDA will provide a EUR 1 million grant for project preparation and implementation.

Nuredini: the first serious investments since the country’s independence

Naser Nuredini, Minister of Environment and Physical Planning, said that North Macedonia, finally, after 31 years of independence, is seriously investing in the establishment of infrastructure for waste management in line with EU standards.

The new approach will enable the application of a better model of waste collection, transportation and disposal and the construction of two sanitary landfills, Nuredini said.

According to Nuredini, apart from the acquisition of modern equipment, the project will include developing habits and raising the awareness of the population about waste selection and the benefits they get from it.

Nuredini signed the loan agreement with Suzan Goeransson, the EBRD’s director for infrastructure for Europe, who noted that modernizing waste management systems and increasing recycling rates are key to reducing pollution, enabling the circular economy, and bringing the country closer to EU environmental standards.

Source

Vladimir Spasić, North Macedonia secures funding for first major investment in waste management, in: Balkan Green Energy News, 18-01-2023, https://balkangreenenergynews.com/north-macedonia-secures-funding-for-first-major-investment-in-waste-management/?fbclid=IwAR2aMK06oGrnjLfuImP9KjIzhG7MjoMRLsIsuQX3DjfmQQA5vW5Hn-FbS3o

[1] Pelagonia (Macedonian: Пелагонија, romanized: Pelagonija; Greek: Πελαγονíα, romanized: Pelagonía) is a geographical region of Macedonia named after the ancient kingdom. Ancient Pelagonia roughly corresponded to the present-day municipalities of Bitola, Prilep, Mogila, Novaci, Kruševo, and Krivogaštani in North Macedonia and to the municipalities of Florina, Amyntaio and Prespes in Greece.

[2] Polog (Macedonian: Полог, romanized: Polog; Albanian: Pollog), also known as the Polog Valley (Macedonian: Полошка Котлина, romanized: Pološka Kotlina; Albanian: Lugina e Pollogut), is located in the north-western part of the Republic of North Macedonia, near the border with Serbia.

[3] The Vardar Statistical Region (Macedonian: Вардарски Регион) is one of eight statistical regions of North Macedonia. Vardar, located in the central part of North Macedonia, borders Greece to the south. Internally, it borders the Pelagonia, Southwestern, Skopje, Southeastern, and Eastern. The Vardar Statistical Region is named after the Vardar River, which runs through the region.

[4] The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) is an international financial institution founded in 1991. As a multilateral developmental investment bank, the EBRD uses investment as a tool to build market economies. Initially focused on the countries of the former Eastern Bloc it expanded to support development in more than 30 countries from Central Europe to Central Asia. Similar to other multilateral development banks, the EBRD has members from all over the world (North America, Africa, Asia and Australia, see below), with the biggest single shareholder being the United States, but only lends regionally in its countries of operations. Headquartered in London, the EBRD is owned by 71 countries and two European Union institutions, the newest shareholder being Algeria since October 2021. Despite its public sector shareholders, it invests in private enterprises, together with commercial partners.

[5] The Ministry of Environment and Physical Planning, through its Department of Spatial Planning, is mandated to manage and implement the policies and monitor the processes of space shaping in the Republic of Macedonia. https://www.moepp.gov.mk/en/%D0%BC%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B5%D1%80%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B2%D0%BE/%D1%81%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1%82%D0%BE%D1%80-%D0%B7%D0%B0-%D0%BF%D1%80%D0%BE%D1%81%D1%82%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%BE-%D0%BF%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%9A%D0%B5/

[6] The State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (often termed as SECO) is Switzerland's governmental centre of expertise for economic policy, which includes economic development cooperation.

[7] Sida is Sweden's government agency for development cooperation. We strive to reduce poverty and oppression around the world. In cooperation with organisations, government agencies and the private sector we invest in sustainable development for all people. https://www.sida.se/en

[8] The Western Balkans Investment Framework (WBIF) supports socio-economic development and EU accession across the Western Balkans through the provision of finance and technical assistance for strategic investments. It is a joint initiative of the EU, financial institutions, bilateral donors and the governments of the Western Balkans. https://www.wbif.eu/about/about-wbif

[9] The Energy Regulatory Commission of the Republic of North Macedonia was set up in 2002 as an independent regulatory body that shall take care for (1) safe, secure and quality supply to the energy consumers;(2) nature and environment protection;(3) consumer protection; (4) protection and improvement of the position of those employed in the energy sector; and (5) introduction and protection of a competitive energy market on the principles of objectivity, transparency and non-discrimination. https://www.erc.org.mk/Default_en.aspx

0 notes

Text

Mayu 26, 2022

Skochivir, Novaci, Pelagonia, Lagu na Masedonia

Kondision tiempo: ☀

Temperaturan chatangmak: 13°C

Temperaturan ha'åni: 28°C

Temperaturan puengi: 14°C

0 notes

Video

youtube

How the Romans Retook Constantinople - Pelagonia 1259 DOCUMENTARY

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Summer evenings...! . #styleblogger #cherithreadgill #vienna #sunsets #summer #neverend #wewaitedsolong #freshflowers #flowerstagram #petunias #pelagonia #1010 #travel #europe

#cherithreadgill#europe#summer#1010#flowerstagram#wewaitedsolong#styleblogger#travel#petunias#neverend#freshflowers#pelagonia#vienna#sunsets

0 notes

Photo

Мрамор PELAGONIA Страна Греция,толщина 20 мм Цвет бежевый,полированный 📱 095 054 24 78 📱 096 017 41 28 Поставка слэбов и изделий из него! (at ООО Тетра Групп) https://www.instagram.com/p/CWnuhM9oudH/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Text

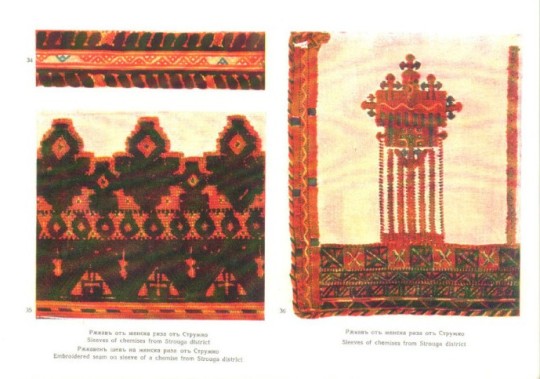

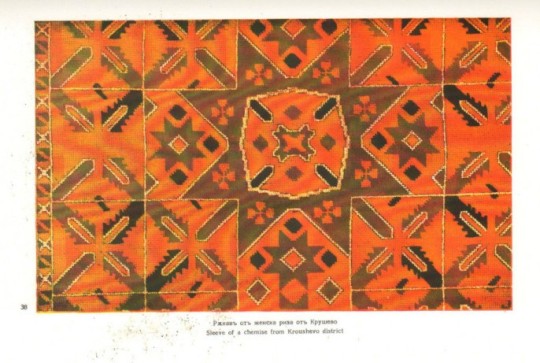

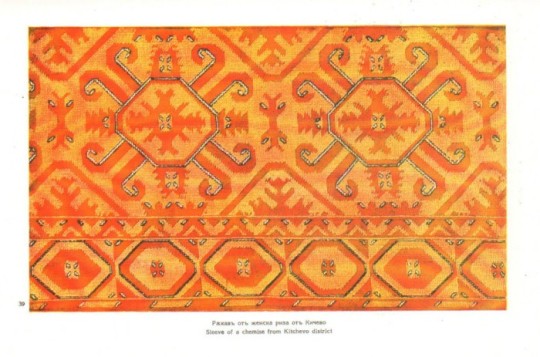

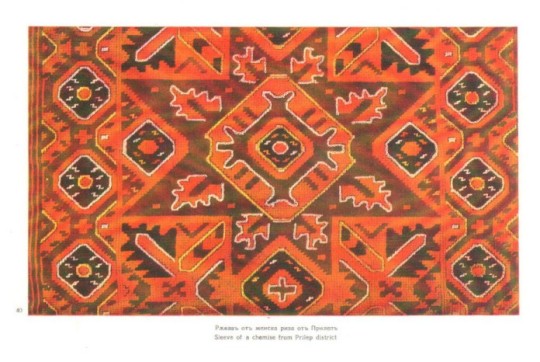

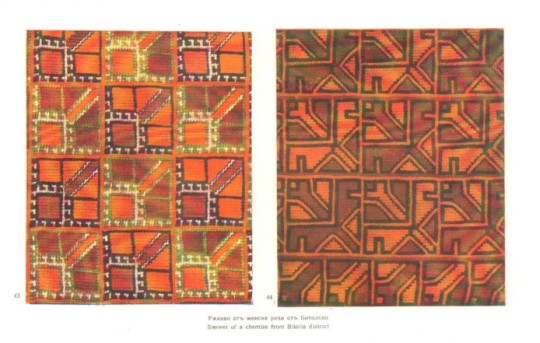

Examples of sleeve embroidery from various parts of Macedonia. | Везани ръкави на ризи (кошули) от Македония.

34; 35; 36. Struga district. | Стружко.

38. Krushevo district. | Крушевско.

39. Kichevo district. | Кичевско.

40. Prilep district. | Прилепско.

41. Resen district. | Ресенско.

42; 43; 44. Bitola district. | Битолско.

45. Kastoria/Kostour district. | Костурско.

46. Bitola district. | Битолско.

From the Album of Bulgarian Macedonian Embroideries by Raina Roumenova.

#Vardar Macedonia#Aegean Macedonia#embroidery#chemise embroidery#folk clothing#album images#Macedonia#Struga#Krushevo#Kichevo#Prilep#Pelagonia#Resen#Prespa#Bitola#Kastoria

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, Dr. Reames. I admire your work a lot and I thank you profusely for taking the time to answer asks in such a detailed manner.

If possible, could you talk a bit about the Alexander of Lyncestis affair? I always get mixed up about it (because of the relation to Antipater and Parmenion). Do you think he really wrote to Darius and would had murdered Alexander if he hadn't been stopped?

First, a quick summary of who he was, and the importance of Lynkestis vis-à-vis Macedon, then I’ll explain the conspiracy and why it’s possible Parmenion framed him.

Welcome, btw, to the Wonderful World of Macedonian Prosopography. I am a crazy person and love this stuff. 😝 Also, because we have too many Alexanders, I’m going to call Alexander the Great “ATG” throughout.

Alexander’s father was Airopos (Aeropus), basileus* of Lynkestis, cousin of Philip’s mother, Eurydike. When Airopos was banished by Philip at some point during the Charioneia campaign (338), his eldest son Alexander became basileus in turn. Alexander had two younger brothers, Heromenes and Arrhabaios, and probably unmentioned sisters.

He married Antipatros’s daughter, although we’re not told when. Antipatros’s kids are curious. The man was older than both Philip and even Parmenion, but had a string of offspring (7 boys and 4? girls) who seem to have been mostly ATG’s generation or younger. Perhaps he married late. Or his first wife was barren/had only a few children, and he married again after she died. We know the names of 3 of Antipatros’s daughters: Phila, Eurydike, and Nikaia, but there may have been an older fourth. The wife of Alexander of Lynkestis was not the famously clever Phila, already married to Balakros (later married to Krateros, and then to Demetrios Poliorketes). Possibly she was Eurydike or Nikaia, who didn’t marry (again?) till after ATG’s death. Yet if so, I’d expect the earlier marriage to the Lynkestian to be mentioned when we hear of them during the Successor Wars (as with Phila). Ergo, I suspect this an older, 4th daughter.

We don’t know Alexander’s age when he took control of Lynkestis. Airopos was still in the army in 338, so no older than his 60s, making him a contemporary of his cousin, the queen mother (Eurydike). This puts a terminus ante quem of mid-40s for Alexander of Lynkestis, but he could have been as young as late 20s (not any younger). I think mid/late 30s a safe guess.

As for his canton…before Philip, Lynkestis was an independent kingdom in Upper Macedonia located around Lake Ohrid. (See Selena’s map from my novel.) Along with Elimeia, Lynkestis had a troubled history with lowland Macedonia and the Argead royal house. On multiple occasions, they’d supported alternative Argeads for the throne—mostly to destabilize Macedon. Recent archaeology at Tribinishte (ancient Lychnidos) shows wealth and cultural development by the mid-500s (Archaic Age). But they seem to have been culturally distinct from lowland populations around Aegae, Sindos, and Archontiko (whose archaeology also shows wealth from c. 570 onward). The Lynkestian royal house had ties to Illyrian royal houses via intermarriage. Philip’s mother, a Lynkestian princess, was arguably half-Illyrian (see Beth Carney’s relatively recent monograph on her).

My main point is that these people had been independent, and quite powerful, for a few hundred years before Philip brought them under the Macedonian yoke. He did the same thing to Elimeia, in the southern highlands, as well as Orestis, sandwiched in-between, plus Pelagonia and Eordia. With the possible exception of the latter, and Almopia, these areas were NOT that firmly under the Macedonian heel. (See map again)

This explains why ATG would so readily believe the younger Lynkestian brothers were involved in Philip’s murder. They even had Phillip’s banishment of their father as an incentive. Initially, the older brother Alexander was included in the accusation, but as he supported ATG immediately after Philip’s murder, and had Antipatros protecting him, he was acquitted.

This isn’t to say a conspiracy against Philip existed involving any of them, but for historical reasons, it was an easy sell to claim there had been.

We tend to think of Philip as Master of his Castle and forget his subjugation of the upper cantons was relatively recent, and perhaps not so settled as later historians present it. The 338 banishment of Airopos is a good clue to continued unrest. Airopos and his buddy were exiled for bringing flute girls into camp (breaking Philip’s rules). But this wasn’t about the girls—it was about challenging Philip’s authority. Airopos fled to Athens, with whom Lynkestis had a long history too. As early as the Peloponnesian War, Lynkestis and Athens had ganged up on Perdikkas II.

Philip may have wanted to be rid of a troublesome father in favor of a more tractable son. Married to a daughter of Antipatros, his trusted regent, Philip preferred Alexander. It’s not unlike what he did in Epiros earlier. He’d chased out Arybbas, Olympias’s uncle, to put her brother Alexander on the throne because he trusted Alexander’s loyalty. (Yeah, too many Alexanders.)

In any case, Alexander of Lynkestis’s tie to Antipatros would elevate him under Philip and save him under Alexander—at least once.

Before we go on, I have to explain another court rivalry that isn’t about Alexander of Lynkestis, but would impact him. That’s the (apparent) rivalry between Antipatros and Parmenion.

Antipatros’s family seems to have had ties to the Argead royal house. During the Peloponnesian War, an ancestor held an important command and regency under Perdikkas II. Antipatros himself had been advisor and regent to Phil’s older brother, Perdikkas III. Philip “inherited” him, and some stories from Athenaeus’s Supper Party suggests he may have found him a bit intimidating. Antipatros was also a friend of Aristotle, and penned several histories and other works.

Contrast Parmenion. His rise at court coincided with Philip’s kingship and they were personal friends. It’s been suggested he was a relative of the Pelagonian royal family, whose basileus was a Philotas (probably not Parmenion’s own father, but you’ve seen how popular royal names repeat). Pelagonia is tucked up against Lynkestis and Illyria. Perhaps even more than Lynkestis, Pelagonia had Illyrian ties. Anyway, if that’s true, I wouldn’t be surprised if Philip first met Parmenion when he put down Bardylis in his first year or so on the throne.

Wherever he came from, Parmenion was a New Man at Philip’s court in contrast to Antipatros’s establishment position. A rivalry is understandable. That also means they would be looking for ways to undermine the other via proxies. Like Alexander of Lynkestis.

The 334 arrest of Alexander of Lynkestis in Syria for conspiracy is a holdover from ATG’s accession crisis, rather than something new. Returning a moment to Philip’s murder, ATG accused Darius of being involved, but if he had been, it was likely only in terms of offering money and a place to escape to for Pausanias. Darius later tried to suborn Attalos, but Attalos turned over Darius’s letter to ATG. It didn’t save him. There was also an Amyntas, son of Antiochus, who hated Alexander so much he fled to Darius’s court (and who was, in fact, supposedly Alexander of Lynkestis’s contact there).

We see Darius willing to exploit already existing fractures in Macedonian politics. Persians had been doing that in Greece for over a hundred years.

So, I don’t doubt a letter from Darius was intercepted by Parmenion on the person of a Persian courier. After questioning [torturing] the courier for the plot, Parmenion sent both letter and courier to ATG, claiming the letter was Darius’s reply to Alexander of Lynkestis, after an earlier overture from the Lynkestian. Maybe. But Alexander of Lynkestis had fared well under ATG. In thanks for his support after Philip’s death, ATG had first given him command in Thrace, then later elevated him to command of the Thessalian Cavalry, the most prestigious cavalry unit after the Companions themselves.

According to the letter, Darius had promised Alexander of Lynkestis the Macedonian throne plus 100 talents…if he’d kill ATG.

For a variety of reasons, some reactionary against ATG, Parmenion is often painted rather rosily by modern historians. Without diminishing the fact ATG murdered him, Parmenion didn’t get to his position by playing nice. Not long before, he’d thrown Attalos under the bus. Perhaps he did so out of loyalty to his friend Philip, and who he’d wanted to inherit the throne—but note that Parmenion’s eldest sons walked away with really plum assignments, especially for their ages: Philotas in command of the entire Companion cavalry, and Nikanor in command of the entire Hypaspists. And of course, Daddy got to stay #2 in the army. Alexander would have been a fool to demote him, but Parmenion understood how to play power games.

Antipatros might be back in Macedonia, but his allies had been plucking nice assignments too, post-Granikos. Balakros (son-in-law) was the new satrap of Cilicia, Antigonos Monophthalmos satrap of Phrygia, and Antigonos’s cousin Kallas also had a new satrapy…freeing command of the Thessalians for Alexander of Lynkestis. Parmenion might have worried Antipatros was getting ATG to put people in place to undermine Parmenion’s influence.

It’s important to keep an eye on who is aligned with whom. I don’t think it outside the realm of possibility that Parmenion framed Alexander of Lynkestis to undercut Antipatros.

The offer of the Macedonian throne is curious. The Lynkestian house is often noted as related to Philip and Alexander. But the most recent tie was via Eurydike, Philip’s mother. That would give Philip a possible claim on the Lynkestian throne…but not a claim of Alexander or his brothers to the Macedonian throne, which could only pass to an Argead. That doesn’t mean there wasn’t an older marriage tie between the two houses, but the link is less clear (our sources suck).

My point is that Alexander of Lynkestis’s claim on the Macedonian throne might be no stronger than one from the Elimeian royal family, or Orestian, or Eordian…. Even if Darius gave him 100 talents, that’s a brush-off. Darius wasn’t going to help Alexander of Lynkestis keep the throne. He just wanted to see ATG dead and the succession in turmoil…so the Macedonians would sink back into the bogs that spawned them and leave HIM alone.

Given Alexander of Lynkestis’s current high position at ATG’s court, but also the precariousness of the army in Asia, making a deal with Darius wouldn’t have been in his best interest (imo). Yet accusing Alexander of such a deak would have been in Parmenion’s interest. And it wouldn’t be hard to convince ATG of such a conspiracy, as Alexander of Lynkestis had been accused once before of plotting the assassination of an Argead.

ATG, or perhaps his advisors, decided to err on the side of caution and arrested Alexander of Lynkestis. But he wasn’t killed. ATG didn’t want to piss off Antipatros. Or he didn’t entirely believe Parmenion. Maybe both. So he had Alexander of Lynkestis carted around under house arrest until the army got to Baktria 3½-4 years later.

I find it ironic that Alexander of Lynkestis met his end as part of the fallout from the Philotas Affair—which he had nothing to do with. ATG just finally felt strong enough in his kingship to get rid of inconvenient baggage. So Alexander of Lynkestis was put to death alongside the son of the man who possibly framed Alexander in the first place, and who would shortly be murdered himself. Perhaps it gave Alexander some bitter satisfaction as he stood beside Philotas, facing down the “firing squad” of spear throwers.

* Basileus means “king,” and these men were kings before being absorbed by Macedon under Philip. Yet by ATG’s day, the Greek term is best translated “princeling.” They were hereditary canton governors now.

On Prosopography: I use a lot of “appears to,” “seems,” and other qualifying terms because so much prosopography is built on probabilities, not certainties. We infer a lot. For those unsure what a prosopographer does, we try to discern the relationships between people, and how that may impact their political choices and alliances. 6 Degrees of Kevin Bacon for the ancient world.

Initial prosopography of Alexander’s court was done by Helmut Berve at the beginning of the 20th century: Das Alexanderreich auf Prosopographischer Grundlage, I & II. In the late ‘70s/early 80s, Waldemar Heckel began to revamp that (in English) in a series of articles about the court and army. In the early 90s, he published the first edition of The Marshals of Alexander’s Empire. As the name suggests, it focused only on the men. In 2006, he produced Who’s Who in the Age of Alexander the Great, that did include women. At roughly the same time (they’re contemporaries), Elizabeth Carney was publishing on women at the court, notably in Women and Monarchy in Macedonia. But she’d also published a number of articles on politics that included men too.

Both have revised their respective books and articles in collections post 2010, including for Beth, King and Court in Ancient Macedonia (2015), and for Waldemar, Alexander’s Marshals (2019) and new Who’s Who that includes the Hellenistic Age (2021). They frequently have differing opinions, and for anyone seriously interested in the courts of Philip, Alexander, and the Successors, these are now standard works.

#Alexander of Lynkestis#Alexander the Great#Philip II of Macedon#Philip of Macedon#Parmenion#Antipatros#Antipater#Parmenio#Darius III#prosopography#Alexander prosopography

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Noteworthy amours of Andronicos

The most noteworthy amours of Andronicos were carried on with members of the imperial family. Eudocia, his second cousin, was his first mistress. As a marriage between the two was regarded by the Church as incestuous, her brother and other relations did their utmost to separate the offenders. When their efforts failed, her brother John, with others, plotted to assassinate Andronicos. The members of the imperial family had encamped in luxurious tents at Pelagonia. Eudocia was known to be in the habit of receiving her lover at unseasonable hours, and a number of men were employed to kill him as he left her tent.

Her spies, however, gave warning of the danger, and, while her attendants were noisily engaged in bringing lights, Andronicos escaped by cutting a slit in the tent and creeping between the sentries. Shortly afterwards he was imprisoned by Manuel in consequence of his political intrigues with the King of Hungary, but under pretext of his conduct with Eudocia. He was loaded with chains and confined in a tower built of brick. There he found a passage partly walled up. He enlarged the hole, laid up a stock of provisions, entered the passage, and from within walled up the entrance.

Eudocia

The guards, finding the tower empty, in great alarm reported the escape of Andronicos to the emperor. Eudocia, who was suspected of having aided in the escape, was captured and sent to the same tower, and when the guards had withdrawn was surprised to see her lover break through the wall covered with lime and dust. He subsequently escaped, but was soon afterwards recaptured and again loaded with chains and imprisoned. A second time he escaped. He had succeeded in obtaining an impression of the keys of his prison in wax. From this his son had new keys made, which he conveyed to his father, together with a coil of rope, in an amphora of wine.

0 notes

Photo

Noteworthy amours of Andronicos

The most noteworthy amours of Andronicos were carried on with members of the imperial family. Eudocia, his second cousin, was his first mistress. As a marriage between the two was regarded by the Church as incestuous, her brother and other relations did their utmost to separate the offenders. When their efforts failed, her brother John, with others, plotted to assassinate Andronicos. The members of the imperial family had encamped in luxurious tents at Pelagonia. Eudocia was known to be in the habit of receiving her lover at unseasonable hours, and a number of men were employed to kill him as he left her tent.

Her spies, however, gave warning of the danger, and, while her attendants were noisily engaged in bringing lights, Andronicos escaped by cutting a slit in the tent and creeping between the sentries. Shortly afterwards he was imprisoned by Manuel in consequence of his political intrigues with the King of Hungary, but under pretext of his conduct with Eudocia. He was loaded with chains and confined in a tower built of brick. There he found a passage partly walled up. He enlarged the hole, laid up a stock of provisions, entered the passage, and from within walled up the entrance.

Eudocia

The guards, finding the tower empty, in great alarm reported the escape of Andronicos to the emperor. Eudocia, who was suspected of having aided in the escape, was captured and sent to the same tower, and when the guards had withdrawn was surprised to see her lover break through the wall covered with lime and dust. He subsequently escaped, but was soon afterwards recaptured and again loaded with chains and imprisoned. A second time he escaped. He had succeeded in obtaining an impression of the keys of his prison in wax. From this his son had new keys made, which he conveyed to his father, together with a coil of rope, in an amphora of wine.

0 notes

Text

Mayu 26, 2022

BRAJCINO, RESEN, PELAGONIA, LAGU NA MASEDONIA

Kondision tiempo: ☀

Temperaturan chatangmak: 13°C

Temperaturan ha'åni: 27°C

Temperaturan puengi: 14°C

AGIOS GERMANOS, PRESPES, PRESPES, FLORINA, LUCHA NA MASEDONIA, GRESIA

Kondision tiempo: ☀

Temperaturan chatangmak: 12°C

Temperaturan ha'åni: 27°C

Temperaturan puengi: 13°C

0 notes

Photo

Noteworthy amours of Andronicos

The most noteworthy amours of Andronicos were carried on with members of the imperial family. Eudocia, his second cousin, was his first mistress. As a marriage between the two was regarded by the Church as incestuous, her brother and other relations did their utmost to separate the offenders. When their efforts failed, her brother John, with others, plotted to assassinate Andronicos. The members of the imperial family had encamped in luxurious tents at Pelagonia. Eudocia was known to be in the habit of receiving her lover at unseasonable hours, and a number of men were employed to kill him as he left her tent.

Her spies, however, gave warning of the danger, and, while her attendants were noisily engaged in bringing lights, Andronicos escaped by cutting a slit in the tent and creeping between the sentries. Shortly afterwards he was imprisoned by Manuel in consequence of his political intrigues with the King of Hungary, but under pretext of his conduct with Eudocia. He was loaded with chains and confined in a tower built of brick. There he found a passage partly walled up. He enlarged the hole, laid up a stock of provisions, entered the passage, and from within walled up the entrance.

Eudocia

The guards, finding the tower empty, in great alarm reported the escape of Andronicos to the emperor. Eudocia, who was suspected of having aided in the escape, was captured and sent to the same tower, and when the guards had withdrawn was surprised to see her lover break through the wall covered with lime and dust. He subsequently escaped, but was soon afterwards recaptured and again loaded with chains and imprisoned. A second time he escaped. He had succeeded in obtaining an impression of the keys of his prison in wax. From this his son had new keys made, which he conveyed to his father, together with a coil of rope, in an amphora of wine.

0 notes

Photo

Noteworthy amours of Andronicos

The most noteworthy amours of Andronicos were carried on with members of the imperial family. Eudocia, his second cousin, was his first mistress. As a marriage between the two was regarded by the Church as incestuous, her brother and other relations did their utmost to separate the offenders. When their efforts failed, her brother John, with others, plotted to assassinate Andronicos. The members of the imperial family had encamped in luxurious tents at Pelagonia. Eudocia was known to be in the habit of receiving her lover at unseasonable hours, and a number of men were employed to kill him as he left her tent.

Her spies, however, gave warning of the danger, and, while her attendants were noisily engaged in bringing lights, Andronicos escaped by cutting a slit in the tent and creeping between the sentries. Shortly afterwards he was imprisoned by Manuel in consequence of his political intrigues with the King of Hungary, but under pretext of his conduct with Eudocia. He was loaded with chains and confined in a tower built of brick. There he found a passage partly walled up. He enlarged the hole, laid up a stock of provisions, entered the passage, and from within walled up the entrance.

Eudocia

The guards, finding the tower empty, in great alarm reported the escape of Andronicos to the emperor. Eudocia, who was suspected of having aided in the escape, was captured and sent to the same tower, and when the guards had withdrawn was surprised to see her lover break through the wall covered with lime and dust. He subsequently escaped, but was soon afterwards recaptured and again loaded with chains and imprisoned. A second time he escaped. He had succeeded in obtaining an impression of the keys of his prison in wax. From this his son had new keys made, which he conveyed to his father, together with a coil of rope, in an amphora of wine.

0 notes

Photo

Noteworthy amours of Andronicos

The most noteworthy amours of Andronicos were carried on with members of the imperial family. Eudocia, his second cousin, was his first mistress. As a marriage between the two was regarded by the Church as incestuous, her brother and other relations did their utmost to separate the offenders. When their efforts failed, her brother John, with others, plotted to assassinate Andronicos. The members of the imperial family had encamped in luxurious tents at Pelagonia. Eudocia was known to be in the habit of receiving her lover at unseasonable hours, and a number of men were employed to kill him as he left her tent.

Her spies, however, gave warning of the danger, and, while her attendants were noisily engaged in bringing lights, Andronicos escaped by cutting a slit in the tent and creeping between the sentries. Shortly afterwards he was imprisoned by Manuel in consequence of his political intrigues with the King of Hungary, but under pretext of his conduct with Eudocia. He was loaded with chains and confined in a tower built of brick. There he found a passage partly walled up. He enlarged the hole, laid up a stock of provisions, entered the passage, and from within walled up the entrance.

Eudocia

The guards, finding the tower empty, in great alarm reported the escape of Andronicos to the emperor. Eudocia, who was suspected of having aided in the escape, was captured and sent to the same tower, and when the guards had withdrawn was surprised to see her lover break through the wall covered with lime and dust. He subsequently escaped, but was soon afterwards recaptured and again loaded with chains and imprisoned. A second time he escaped. He had succeeded in obtaining an impression of the keys of his prison in wax. From this his son had new keys made, which he conveyed to his father, together with a coil of rope, in an amphora of wine.

0 notes

Photo

Noteworthy amours of Andronicos

The most noteworthy amours of Andronicos were carried on with members of the imperial family. Eudocia, his second cousin, was his first mistress. As a marriage between the two was regarded by the Church as incestuous, her brother and other relations did their utmost to separate the offenders. When their efforts failed, her brother John, with others, plotted to assassinate Andronicos. The members of the imperial family had encamped in luxurious tents at Pelagonia. Eudocia was known to be in the habit of receiving her lover at unseasonable hours, and a number of men were employed to kill him as he left her tent.

Her spies, however, gave warning of the danger, and, while her attendants were noisily engaged in bringing lights, Andronicos escaped by cutting a slit in the tent and creeping between the sentries. Shortly afterwards he was imprisoned by Manuel in consequence of his political intrigues with the King of Hungary, but under pretext of his conduct with Eudocia. He was loaded with chains and confined in a tower built of brick. There he found a passage partly walled up. He enlarged the hole, laid up a stock of provisions, entered the passage, and from within walled up the entrance.

Eudocia

The guards, finding the tower empty, in great alarm reported the escape of Andronicos to the emperor. Eudocia, who was suspected of having aided in the escape, was captured and sent to the same tower, and when the guards had withdrawn was surprised to see her lover break through the wall covered with lime and dust. He subsequently escaped, but was soon afterwards recaptured and again loaded with chains and imprisoned. A second time he escaped. He had succeeded in obtaining an impression of the keys of his prison in wax. From this his son had new keys made, which he conveyed to his father, together with a coil of rope, in an amphora of wine.

0 notes