#Scrap Metal Seven Hills

Text

Metal Recycling St Marys: We Recycle Metal for Cash | Scrap Metal Blacktown

#scrap metal riverstone#scrap metal penrith#scrap metal seven hills#scrap metal mcgraths hills#scrap metal mulgrave#scrap metal castle hills#scrap metal blacktown#scrap metal windsor#scrap metal st marys#scrap metal richmond

0 notes

Text

Find out all the options for Scrap Copper sydney. Check out all about pricing, recycling options, pick up options, pricing, and many more things.

0 notes

Text

Seeking Top Cash for Your Scrap Metal in Seven Hills?

If you're in Seven Hills and have scrap metal in seven hills to sell, look no further than Local Scrap Metal. We're your go-to destination for the best prices and friendly service. Don't miss out on cashing in your copper scrap. Visit us today and experience our expertise!

0 notes

Text

Experienced Copper Scrap Buyers in Penrith, NSW | Scrap Metal Windsor

#scrap metal windsor seven hills#scrap metal richmond#scrap metal oakville#scrap metal windsor castle hills#scrap metal windsor#scrap metal windsor st marys#scrap metal north richmond#scrap metal riverstone#scrap metal windsor richmond#scrap metal vineyard

0 notes

Link

Scrap Metal Recycling Seven Hills with hassle-free procedures. Make use of our services without hassles and simplified procedures, you will love for sure.

0 notes

Text

The Lamb's Mother (3/3)

Probably should've let this rest but meh it's my first fic in years idc.

CW: suicide, disemboweled corpse, Lamb has the worst mother of the three.

Their mother warned them.

She said, “There’s something not right with a lamb who can’t follow.” And this was true, as they could listen, and they could try, and they could learn, but they couldn’t follow.

While gathering apples in the wild orchard they once got distracted and found a hollowed tree with the biggest honeycomb they’d ever seen. It was enough for the whole flock and then some, so they spent the rest of that morning digging the pit and foraging the herb and directing the smoke and wrapping the comb and—

Yes, in the end Ram admitted they’d brought back some ten pounds of honeycomb, but also none of the apples they and their cousins had gone for. None of the sheep had been brave enough to come find them on their own, and had chosen to keep gathering apples instead.

“We need honey for mead, and spread, and medicine,” Ram allowed, their horns curled twice in loops as strong as a mountain’s twin peaks. “But we also need apples for cider, and pies, and for hungry sheep to snack on.”

He gave them a tiny pink apple, still tangy from the summer sun, while the others ate fresh pie. At least Grandram let the wandering lamb sneak a bite of honeycomb with their cold supper.

They were Mother’s third lamb.

Their eldest sister went fishing with their cousins and, one time when the water turned dark and the sky began to rumble, she threw her basket into the whitecaps and waited for the first kin to run before taking off. She left two of their cousins behind for the jellyfish of pestilence to tear apart and returned home with no fish, but she followed her friend and they both came back.

“She came back,” Mother repeated when they didn’t understand. She’d brought back no food and lost two kin-folk, how was this a good thing? “Nothing is worth dying for, not food, not love, nothing. She came back, and you will do the same. You will always come back.”

Their brother was a skilled craftsperson. He could fix a wagon wheel in an hour, and build a tent in blink, and he taught them and their cousins how to read the bark of a tree for the good wood and the hills for straight stone. He was proud of his apple press, a construction of meticulous joints, strong timber, and a single precious gear bartered for a month’s worth of soap and seven jars of berry jam.

This, they understood. They could always make more soap and gather more berries, but the ants only came out of their tunnels for a few months a year, never in the same place, and they didn’t part with their metals easily. That their family went without soap and jam for a few weeks was worth it, in their eyes.

Mother disagreed. She bleated all autumn about dirty wool and plain bread until the first batch of cider was made from the press. They made so much they could trade it back to the other lambs for what their brother had spent, but she never really forgave him.

“You cannot plan for tomorrow without sacrificing today,” she warned them, but the meaning didn’t take. It never did. They were a lamb who couldn’t follow their flock.

Their crooked horn proved it. Grandram bleated in fright at the next spring’s sheering when their nubs sprouted—one proud like Ram’s, one twisted to the side.

It all made sense after that, and nothing Ram said could make it better.

They cried for weeks, throughout the whole migration from the protective mountains of Silk’s Cradle down into the Dark Wood for planting and foraging. There was nothing Chaos, Famine, Pestilence, or War could do to fix their horn, and such prayers would have only made it harder to hide from the hunters.

Mother was done with their crooked weaving, and barred them from the loom. She let them keep their hook and needles, so they could make flowers and mittens and tiny sheep from the undyed scraps, but not at her stool.

Their sister chased them from the garden patch so they would stop over-watering and badly pruning. She sent them to find seeds and saplings and nuts and cool rocks and anything else to throw in the compost when she was done going through it. There were a lot of rocks.

Their brother, who cared more than he should have, let them keep whittling birds and knives and little hoops—but only with the junk wood. They made a new flour bowl for Mother, but she never used it. They made fishing hooks for their sister, but she left them behind. They made a new handle for the apple press, but it wasn’t as good as the one their brother already had for it.

Their horn kept growing wrong. Curled like Ram’s but out instead of back. They used a chisel and broke it off, then the other. There was no one to pray to to beg them both to come back right.

Grandram made them sit and learn letters with them. When that failed, they put a flute in their mouth and a drum at their feet. When these lessons began to take, they brought the books out again but this time they sang the stories. Knowing the words made the shape of them come together. Understanding the story made it easier to re-phrase and re-write it their own way.

The still ants traded with the sheep because once the sheep had given them an island wrapped in mists. In exchange for the island, their people travelled under land beneath the sea across the sky to come here. They did not come on the dogs’ boats, or the cats’ balloons, or the ponies’ carts. They did not ride with the pigs or share with the birds or play with the foxes. The sheep were the last to leave the island, and they gave the ants land and water and stone to hide their journey away from home.

Once they had been a people like every other: with villages and hamlets and acres of pasture and orchard each one tended, not like the wild trees and the garden patches. They had summered and wintered in the same groves, and never moved unless they wanted to, never parted unless they chose to, were never hunted. Ever.

They had had a god once too, one they shared with the birds and the cats and the ponies and the pigs. And Famine had only claimed them for so long until Bounty returned; and Pestilence had lurked but Renewal had protected them; and War had raged only until Peace was restored; and Chaos had its day but Order was the norm. There had always been death.

Ram said he liked how they could sing and play at the same time. He said they would make a great storyteller one day. Ram said many things that didn’t matter in the end.

“There will always be death,” their mother warned them, that summer in Anura’s mildewed fields. She said it with the warm rain soaking their fleece, slowing them down in the mud up to her waist. “The only constant left for us is death.”

They were the one, muscles straining and limbs shaking, who wrenched themselves up on the rock and looked back. Mother just sat there, in the mud, staring up at Ram’s desiccated body hanging from the crown of a mushroom tree over their head. The hunters had put out his eyes, and his entrails had been pulled out like ribbons and tied around their brother’s neck to decorate the real noose that had strangled him.

Behind them, in the rain, trapped in the muck, their sister screamed as Famine’s hunters caught her. They couldn’t see them for the tall stalks of grain. They heard every slop of flesh and broken bone.

“Go,” Mother said, her black eyes raptured on Ram. “I don’t know the way without him. I don’t know how to be anywhere without him. I don’t want to follow if he won’t lead me.”

“Mama—” they begged, voice breaking, world ending, hands reaching. “Mama, please—”

She closed her eyes, the dark sky pouring curtains of rain down on the mire. She held her palms open on her mud-stained lap, face up in the thundershower, her heart and throat open with no god to want her.

“There’s something not right with you,” she warned them. “You’ve never known how to follow. So, go. Go.”

Red lights in the rain. Green torches, yellow flames, chittering and squelching and the plop-plop-plop of webbed feet leaping through the muck.

They got on one knee, Ram’s blood staining their ruined fleece as they reached out. She was close enough to touch. She was right in front of them. She just had to try.

“Mama!”

“Just go away…”

Mother pulled out her good cooking knife. Lightning filled the world with white.

Three hundred years later, in the gateway between life and death, the Lamb will look up in the unending white and see people they know, and care about, and are deeply, deeply unlike all strung up on posts with their entrails exposed. Their blood will spill like mana to feed a god they no longer understand. They will be told to kneel, to submit, to become small in endless storm of their world’s history. They will be expected to follow. They will be told to follow. They will be ordered, and screamed at, and condemned to follow.

“There’s something not right with me, my Lord,” they will say, salty tears hot as summer rain down their blanched face. The crown in their hands will bend one point, crooked like the horns between which it has sat for centuries. “I’ve never known how to follow.”

The Red Crown will become Mother’s good cooking knife.

But on that day, in the distant past, at the edge of a fallow summer field with the faint stink of woodsmoke and burnt wool threading through the midnight rain, they weren’t strong enough to watch their mother take her own life. They turned and fled before she placed the edge to her throat. They ran and did not stop running until the sun was high and the mushrooms ran thin in the summer yellow grass.

Their mother warned them. She told them they could not follow, and in the end, after their capture and chains and the swing of the axe: she was right.

They did not follow.

They came back instead.

[Start] / [Prev] / [Next] <- Coming when I have min 3 decent chapters to post. (May 28, 2024)

#cotl#cult of the lamb#cotl The Lamb#cotl Lamb#cotl lambert#cotl au#Estrangement AU#Lamb has the worst mom of the three yes thats harsh no I don't care#there's nothing about ants and sheep in the game dw#I do 100% headcanon Narinder as favoring the land animals while his siblings had other animal kingdoms#my lamb is not well and won't be for 90% of this fic

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝕙𝕠𝕨 𝕥𝕙𝕖𝕪 𝕗𝕚𝕟𝕕 𝕠𝕦𝕥 𝕒𝕓𝕠𝕦𝕥 𝕪𝕠𝕦𝕣 𝕟𝕚𝕡𝕡𝕝𝕖 𝕡𝕚𝕖𝕣𝕔𝕚𝕟𝕘𝕤: 𝕣𝕒𝕥𝕔𝕙𝕖𝕥 𝕖𝕕𝕚𝕥𝕚𝕠𝕟

Authors note: by the way there’s a poll at the bottom for who I should do next! Also as a side note please listen to your piercer about piercing care: no mouths should go on nipples for between 6-8 weeks post piercing MINIMUM.

Rating: M (not sexually explicit but implies actively VERY heavily)

Summary: TFP!Ratchet finds out your nipples are pierced. That’s it. End tweet.

Content warnings: talk of pain of piercing, reader has boobs and wears a padded bra but is not explicitly referred to as a woman, ratchet being ratchet, ALMOST valveplug it stops before the good part, reader is minority injured

He first noticed the body modifications while he was doing a full scan of your body. You’d taken a mean tumble down a ravine, holding an auto bot artifact close to your chest as you fell straight through the bright green ground bridge.

You’d twisted your ankle, and were covered in scraps in bruises that adrenaline refused to let you feel. Ratchet, ever diligent as a team medic, insisted on doing a full body scan to make sure you hadn’t injured anything during you “child-like hill roll”. Which it was NOT, mind you. A hundred feet down a rocky, dusty ravine that was practically vertical was no where near as pleasant as the grassy Piedmont hills from your childhood memories.

Ratchet snaps you out of your thoughts. “Care to tell me about the partially healed wounds on your breast tissue?”

You know he isn’t give you a choice, especially when Arcee, Bulkhead and Optimus Prime turn to look at you. “No, not really.”

Ratchet sighs. His vents stutter at your lack-luster, brat-like outburst. “Then would you care to tell me why there are pieces of metal stuck in them?”

“Also, no.”

You hear the heavy foot falls of Optimus Prime rather than see him approach because of the holes you’re staring into the grates of the floor of the platform. Frankly, you’d rather take that tumble four times than look at either of the bots right now.

Optimus calls your name firmly, quietly but with an authority that grabs your heart, squeezes it, and twists it out of your chest and into your throat. “If you ever need medical assistance,” you see his servo holding the railing in your peripheral vision, and still don’t look up, “you can always come to us.”

Ratchet huffs in agreement. “I can’t have you dying on us because you feel like a cold is too much of a bother for me.” You can see under the grumpy, huffy exterior, he’s hurt because you didn’t come to him. And it makes your heart swell because you really like him.

But in the same beat it also hurts you because you hurt him.

“It’s not an injury,” you confess, counting the holes in the grates of the platform. You’ve counted fourth-seven so far, “it’s a cosmetic modification I got, on earth they’re called piercings.”

“Like the ones Miko has in her ears?” Bulkhead chimes in.

“Yeah!” You exclaim, significantly less embarrassed now that someone understands at least a little bit. “Technically you can get them in a lot of places but the ears, nose, and belly button are the most common.”

Ratchet sighs. “How long have you had them?”

“Seven weeks.”

“So they’re still healing?”

You nod your head.

Ratchet scoops you up into his hand, so you don’t have to walk closer to the part of the med-bay he uses for humans. “I’m sure they need to be looked at after you took that tumble.”

Your face turns bright red in an instance. “I’m not showing you my nipples, at least buy me dinner first!”

“I’m a doctor,” Ratchet responds, putting you down on a tiny medical berth.

“And? Just take me somewhere fancy.” You can hear Wheeljacks laughter in the back of room.

“Just take your shirt off,” Ratchet grumbles, “brat.”

You peel the torn piece of formerly-white-now-clay colored shirt over your head, and unclip the basically destroyed bra underneath. They were sweaty, grimy and NOT going back on your body if you could help it, sitting shirtless in front of your giant robot alien crush be damned. Luckily, Optimus would not bear witness to your upper anatomy -thank god- as he had turned around and left the med-bay with you and Ratchet. You’re glad that at least he’s respecting your privacy.

Ratchet comes in with an alcohol wipe the size of a small blanket, and starts to gently wipe at all the cuts that litter your torso.

It stings, and you say as much as you squirm away from it.

“Don’t make me hold you still like a petulant child,” Ratchet says, as one servo cups behind your back tenderly but firmly, like how you hold a petulant child.

You pout at him as he wipes the dirt away from the cuts.

“Did they hurt?” He asks eventually, wiping at a nasty gash below your collar bone.

“Huh?”

“The piercings.” He elaborates. Despite the tumble you took, the uncomfortable push up bra took all of the damage, leaving your chest unscathed.

“Not really,” you answer, “my HPV vaccine was worse. It felt like a pinch, and my nipples felt like they were in ice water for like four hours, but that’s the been the extent of the pain from the piercing process itself.”

You can see some of the tension leave from his heavy stare.

“One time Bumblebee’s seatbelt caught on it and that hurt, but that’s it, really.”

Ratchet lifts an optical ridge, “why would you get a body modification that causes you pain?”

At this point, he’s still cupping your back with one servo, and still wiping you down with the wipe, but he’s already gotten all the cuts. You wonder why he’s still doing it. To ask you more questions, perhaps?

“It’s less that it causes me more pain and more that it increases sensitivity.”

Ratchet’s face flushes pink with the rush of energeon to his faceplates. “So it’s a modification to increase pleasure?”

You nod your head, face an equal amount of pink. “It also looks cute.”

He pulls the wipe away from your body, and slowly brings his faceplate closer to you, to your chest.

“I suppose it does,” he whispers softly, almost to himself. You almost didn’t hear him. Almost.

“I’m glad you think so,” you whisper back, flush reaching down your neck, past the tan-line from your t-shirt.

His eyes flicker up to yours, and through the ozone thickening in the room, you can see some unfamiliar emotions spark in Ratchet’s optics. “I suppose we should test the sensitivity of these, shouldn’t we?”

105 notes

·

View notes

Link

#Scrap Metal Silverwater#Scrap Metal Castle Hill#Scrap Metal Smithfield#Scrap Metal Seven Hills#Scrap Metal Blacktown#Scrap Metal Liverpool#Scrap Metal Greenacre

2 notes

·

View notes

Audio

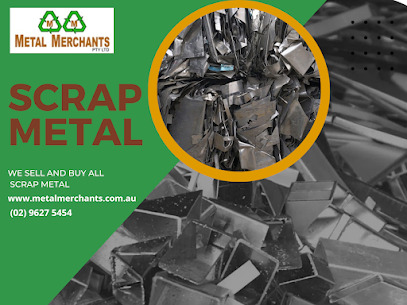

We gather and process ferrous as well as non-ferrous metal to offer them a new lease of life so that they can be utilized to fabricate new merchandise. We deal in a wide range of scrap steel and owing to our bulk buying capability, we're able to present our purchasers with highly competitive prices. This growth elevated business, both intra, and interstate, resulting in dealings with a Scrap Metal Yard in Queensland. Scrap Metal Seven Hills to be trading in affiliation with Southern Cross Metals today. Qt copper scrap recycling is a well-established scrap steel supplier in Sydney that not solely deals in the recycling of any kind of scrap metal but makes a specialty of buying any non-ferrous steel scrap. We have been engaged in recycling scrap copper, scrap brass and stainless steel scrap in Sydney for years now and has thrived over the years as a leading scrap copper dealer. We have over 10 years of expertise in shopping for old vehicles and scrap automobile removal services.

0 notes

Text

Scrap Metal Removal St Marys: We Remove Scrap Metal from Your Property | Scrap Metal Blacktown

St Mary’s is a New South Wales neighbourhood located roughly 45 kilometres from central Sydney. Queen Street is the major commercial street in the suburb.

You either have a surplus of outdated appliances and tools that need to be serviced, or you have completed some structural repair or building for your house or workplace Regardless of where you reside in St Mary’s, you will require scrap metal recycling at some time in your life.. In all situations, you will have metal scrap that must be disposed of. There is no need to be concerned when dealing with Scrap Metal Blacktown.

Simply call us and we will rid of all of your scrap metal while also paying you a fair amount for it.

Scrap Metal Blacktown is a company that collects and pays you for your scrap metal items. In some cases, we also provide free bins and free pick-up services. All that remains is for you to collect any metal-containing items and keep them ready for Scrap Metal Blacktown Representatives to come and make the transaction.

#scrap metal riverstone#scrap metal penrith#scrap metal mcgraths hills#scrap metal castle hills#scrap metal blacktown#scrap metal seven hills#scrap metal windsor#scrap metal mulgrave#scrap metal st marys#scrap metal richmond

0 notes

Link

Retired but not forgotten, Franc nonetheless comes in to help out from time to time. Sell & Parker buys a website at Nowra and opens a brand new yard to service Southern Regional.#Scrap #Metal #Seven #Hills

0 notes

Text

Find Scrap Metal Services in Seven Hills

Are you looking for seven hills scrap metal merchants in Sydney? Local Scrap Metal is the right firm for you that can help you get the perfect solution when there is a huge volume of metals lying in your property that won't serve you anymore. Reach out to us today to know more.

0 notes

Text

Top Prices for Copper Scrap in Penrith, NSW | Scrap Metal Windsor

#scrap metal windsor seven hills#scrap metal windsor st marys#scrap metal richmond#scrap metal oakville#scrap metal vineyard#scrap metal riverstone#scrap metal windsor castle hills#scrap metal windsor#scrap metal north richmond#scrap metal windsor richmond

0 notes

Text

Aegis City

Chapter 1

12-8-2589

Nikolai Cluster

Romulus V

Aegis City

BLEET-BLEET-BLEET!

Frigid air, deafening gale speed wind, melting snowflakes sliding across his bristled face. He looked up. The moons were high in the eternal night sky.

BLEET-BLEET-BLEET!

He shrugged off his weariness and groaned as he slowly raised his head off of his rolled-up jacket and slapped his alarm. His head spun as he rolled out of his tattered canvas-patched blanket, brushing the powdered snow off of his legs. Like he did every day, he made a half-hearted promise to himself that he’d take it easy at the bar that night.

As always, his hands still ached, scarred and worn. He sat up facing the door two feet from his pillow and stared at it as the clock clicked to 5:01. The door opened halfway before stopping with a thud, backing up, trying again, on repeat.

Thunk-hisss, thunk-hisss, thunk-

Still sitting on his cot, he stuck his foot out and caught it as it whirred once again in vain, struggling against the appendage, stopping with a resigned sigh. The frigid air rushed in.

He pulled his card out of his pocket. Name: Finley Roberts. Sex: male. Condition: able. Class: employed. Genesis date: 6-18-2579. On the left he saw his former self, smiling, naïve, clean-shaven and ready for his trip to the new frontier. He looked up at the cracked mirror above the tap to the right of him, gazing into eyes highlighted by dark purple rings, scraggly dark hair and beard, eyes devoid of hope. Ten years ago. Jesus.

Slipping on his boots, he crouched under the doorframe, groaning as his back cracked. He stumbled outside into a pile of chemical refuse and sighed. That’s life in The Shambles.

The Shambles was the name for the twenty square miles of impoverished rubble that used to be a housing project program. The program had set up a field of metal containers with building supplies over the snowy plains and had started to build houses before the program failed when the Company decided to make some expansions to the private first-class sports arena. When the program failed, the new arrivals had nowhere to live, so they produced makeshift shelters from the leftover materials.

Now the area was a dirty, cluttered, chaotic mess of makeshift shacks in a twenty square mile area, dismal and crowded by those with debt over their heads and nowhere else to go.

Fin looked back on his rust-eaten crimson shack that had been made from a metal shipping container. What remained of the low-hanging metal ceiling sagged under the weight of snow and sleet. Black icicles hung from the edge of the roof, sullied by mineral dust and soot from the refineries. The walls were rife with holes, plugged by rags, cardboard, mud, and paper scraps to keep out the cold. The shanty was about four feet wide and seven feet long, making it the average size for a residence in The Shambles.

His threadbare boots hadn’t had time to dry before they were sloshing through the greyish muck, pushing through crowds of people, expressions all dull and somber. He passed the night shift as they slowly integrated into the crowds, like ants retiring to the hill. He kept walking as more workers joined him in silence, approaching the mines where the crowd thickened around the equipment pile, walking past the blue and black uniforms of the P.E.A.C.E. Corps troops that surrounded the site to grab picks and headlamps. He might have been nervous if he hadn’t been so damn tired.

He collared a rusty pick and battered yellow helmet, preparing for the daily struggle to meet the ambitious quota. The elevators whinged as he approached them, shaking with age and fatigue. He stepped onto the crowded steel platform where the resonance met his boots with sharp vibrations, bracing himself as the machine plunged into the darkness.

5 notes

·

View notes