#bob gramsma

Text

Bob Gramsma (NL/CH 1963)

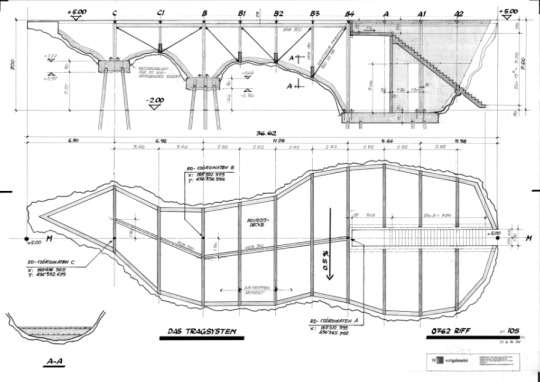

riff, PD#18245 (2019)

Soul, stone, concrete and wood 40x11 m. / 7 m high

Because of 100 Years new Dutch land in the former Zuiderzee new Monuments are made to celebrate. This riff, near Dronten, wants to give expression to the spectacular land reclamation on the former inland sea, rises from the vast, flat, flat new land.

Land Art Flevoland Collection

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roca conmemorativa

Bob Gramsma, es el autor de este monumento holandés que conmemora los 100 años de la ley Zuiderzee, de los Países Bajos.

Su construcción requirió más de 15, 000 metros cúbicos de tierra, así como la implementación de estructuras y pilotes de acero; recubierta con una capa de hormigón armado; que dará el sustento al objeto.

De acuerdo al autor, el color y la forma proyectada es análoga al paisaje o contexto donde se ubica, pues los suelos agrícolas son bastante arcillosos, razón por la cual su revestimiento exterior posee esas características.

Lo que más me preocupa es cómo se puede invertir en una obra de esta magnitud que carece de una estética elocuente; que indique originalidad cuando estos objetos son creados por la misma naturaleza sin intervención del ser humano.

Si el autor deseaba realizar una mímesis de la natura pues lo logró pero creo que hubiese sido más fácil “trasladar” unas rocas y sobreponerlas; al estilo “stonehenge” para crear un monumento con materia prima, y no crear algo que ya se obtiene... y hasta gratis.

Fuente de imágenes

http://www.bobgramsma.com/

#art#sculture#critical art#critic#bob gramsma#arte#arte contemporáneo#contemporanyart#construction#architecture

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

BOB GRAMSMA, on the ground, OI#17241, Concrete, steel reinforcement, foundation, 1850 x 800 x 200 cm Jerusalem Lives, The Palestinian Museum, Birzeit, curator: Reem Fadda, Palestine, 2017. Photo by Hamoudi Shehadeh.

via: http://www.palmuseum.org/ehxibitions/participating-artists-jerusalem-lives

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Bob Gramsma

(via Art Safiental, An Outdoor Exhibition In The Swiss Alps | iGNANT.com)

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Het 8e landschapskunstwerk van Flevoland nu open voor publiek

Het 8e landschapskunstwerk van Flevoland nu open voor publiek

Op zaterdag 12 oktober overhandigde gedeputeerde Michiel Rijsberman de sleutel van het Monument voor 100 jaar Zuiderzeewet, tevens het 8e landschapskunstwerk van Flevoland, aan wethouder Irene Korting van gemeente Dronten. Voorafgaand aan de sleuteloverdracht plaatsten de kunstenaar Bob Gramsma en kinderen van Dronten een tijdscapsule in het kunstwerk. Het idee is om over 100 jaar de capsule weer…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Despair Lake, Art Safiental

Despair Lake, Art Safiental

Images © Thomas Rickenmann

Images © Thomas Rickenmann

Image © Bob Gramsma

Despair Lake, Art Safiental

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: A Garden of Possibilities at the Palestinian Museum

The Palestinian Museum with an unfinished work by Yazan Khalili atop the museum (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic unless otherwise noted)

BIRZEIT, Palestinian Territories — The fact that the Palestinian Museum even exists may surprise some people, not because of the wealth of talent that clearly exists in these lands, but because it suggests a type of normalcy to life in an area that continues to be under occupation. When the project was first announced there were conversations about creating a museum that would reflect the reality of Palestinian life, recognizing that not all Palestinians would be able to even visit it because of Israeli border restrictions against people of Palestinian origin. Then the roughly $30-million transnational museum opened without a major “exhibition,” or at least the type of exhibition we typically envision in art museums. It was a more low-key affair, focusing on objects we often associate with historical displays, but that was also because of the real problems of occupation.

“Until Israel recognize[s] most of the Unesco protocols which protect imported goods in the museum world,” Museum Chairperson Omar Al Qattan told The National, “we can’t really bring anything in except under consular or ambassadorial cover, which means it’s always going to be a problem borrowing or exchanging exhibition objects.”

The colorful map of the gardens at the Palestinian Museum (download a complete garden guide here)

That challenge is important, because a museum today is still often categorized by its landmark treasures, the works that attract crowds. It’s a reality that has inspired artists to think creatively, and one Palestinian artist, Khaled Hourani, highlighted it best in his incredible Picasso in Palestine project back in 2011. That year, Hourani was finally able to bring a Picasso to Palestine. We may take Picasso’s work for granted in Western capitals, but in places under occupation there is real power in the presence of such “masterpiece” objects since shuttling treasures across borders reveals who is actually in control — the fact is that the Palestinian Authority has very limited authority over its own boundaries.

Speaking to Leah Sandals at Canadian Art magazine, Hourani outlined the serious issues he faced when he brought a Picasso painting to Ramallah, the capital of the Palestinian Authority. “How do you bring an artwork into a war zone? Normally this kind of artwork is supposed to go between two states that have clear borders, and it might normally take five months for that, from a museum to a museum,” Hourani explained. “In our situation, you couldn’t guarantee the safety of the artwork. So that was also an obstacle. It was not possible to insure the work 100%. And it took two years, rather than five months, to get the artwork from Eindhoven to Ramallah.” The institution making the loan, the Van Abbemuseum, had to sign off on many of the strict insurance issues.

A view of the gardens and the surrounding landscape from the museum terrace

But the lack of an “exhibition” when the museum opened became a feature of the mainstream media coverage of the institution. That absence, which can be interpreted many ways, was ridiculed by at least one Israeli news source that used the artless halls to hammer home a right-wing talking point: “As such, there is no distinct ‘Palestinian’ history or culture. And, so, it was absolutely fitting that The Palestinian Museum of Art, History and Culture opened its doors with NO EXHIBITS” (emphasis theirs). But on the Israeli left, or what remains of it, newspapers like Haaretz avoided that kind of extremist rhetoric to applaud the reality of this achievement — even pointing out that when Berlin’s Jewish Museum opened in 1999, it did not have a collection.

Yet this Museum is not hindered by its reality and it has decided to source many of its materials and talent from outside Israel, which is clearly a political and conceptual statement. That means the architects (Heneghan Peng) are Dublin-based, the landscape architect (Lara Zureikat) is Jordanian, the exit signs were from Austria (but the Israeli authorities rejected them for import and the builders had to adapt to the bureaucratic hurdle), and all other elements are sourced from elsewhere. It’s hard not to see the very existence of the Palestinian Museum as part of a conceptual project in exploring what is even possible here.

The building itself is a beautiful and stark structure that echoes the taste for minimal elegance in the art world. There is no groundbreaking architecture though, even if the terraced gardens really differentiate the institution from other art venues of this type. Labeled with names that would make a hipster’s head explode with envy — including “Aromatic Garden,” “Medicinal Garden,” and “Olive Garden” (*cue hipsters giggles*) — the gardens are hard to differentiate when on-site because they visually blend into one another, though a veteran gardener may spot these easily.

The garden is also significant because at the foundation of colonialism is the struggle for land. Property and space, particularly public space, are always political, but here they are so much more so considering what people call “Palestine” is more a conceptual space nowadays, rather than a contiguous geography. It’s also significant that the museum is not a governmental structure, but one run by a private nonprofit, and it is also Palestine’s first energy-efficient green building, with a LEED silver certification — another impressive accomplishment.

The Museum’s new exhibition, Jerusalem Lives, is curated by Reem Fadda (with assistant curators Fawz Kabra and Yara Abbas) and features 48 artists, including 18 commissions. While the galleries inside include works by Mona Hatoum, Khaled Hourani, Khaled Jarrar, and other modern and contemporary artists, the outdoor work is a major attraction in its own right.

Emily Jacir’s “Untitled (servees)” (2008) uses the voices of ride-sharing taxi drivers calling out their intended destinations from Jerusalem. It plays on loudspeakers in the museum’s parking lot, and from a distance it can even sound like a muezzin’s call to prayer. In a place where transportation is a hassle, particularly for those with identity papers that limit mobility, the call is both absurd and nostalgic, reminding many of a time when a trip from Jerusalem was far less difficult and could even be done in roughly 30 minutes (it’s only 25 miles away).

Athar Jaber’s “Stone – Opus 15” (2017) with Yazan Khalili’s “Falling Stone, Flying Stone” (2017) in the background.

The specificity of place is also at the core of Athar Jaber’s “Stone – Opus 15” (2017) work, which is fashioned from locally sourced limestone. The Iraqi-Dutch artist has crafted a piece that echoes the worn stone of Jerusalem’s religious landmarks by carving and sanding the hulking stone. If Western art history is still enamored with Michelangelo’s romantic ideal of freeing the figure from a block of marble, Jaber points to a more local history where stones are acts of devotion, touched by hands eager to get close to the divine. In contrast to conventional museums, where objects are roped off from visitors, Jaber invites visitors to graffiti and leave their marks on the work — they can even sit in it. It’s a different approach to art that predates our modern museology.

These works, like all the others, point to Fadda’s bigger thesis: that Jerusalem is the beginning and end point of globalism. It’s a provocative idea, but one that checks out when you think of the city as a continuous and contentious metropolis, one that has been at the center of pilgrimage, power, and intrigue for centuries — in medieval Christian tradition, Jerusalem is home to the “navel of the world” (aka Omphalos); in Jewish, tradition it is considered the center of the world.

Adrián Villar Rojas’s “The Theater of Disappearance” (2017)

In that context, Adrián Villar Rojas’s “The Theater of Disappearance” (2017) is as much a monument to imagination as it is to anything specific. For the piece, which is part of a larger series, he’s sliced Michelangelo’s “David” at the thighs and placed a small sculpture of kittens playing at the sculpture’s feet. The whole thing is sited atop a modernist form that resembles a Soviet-era sculptural podium, and its placement away from the other art — and close to the garden’s entrance — makes for a perplexing introduction to the show. But that displacement is part of its poignancy; like the land of Palestine itself, this is just a fragment of something our imagination works to fill in.

Khalil Rabah’s “48%, 67%,” which is a part of the artist’s Palestine after Palestine New Sites for the Museum Department (2017) project

Palestine has become so hard to conceptualize, and accordingly some of the most successful projects in Jerusalem Lives are focused on abstractions of the land and how they influence historical narratives. Khalil Rabah’s “48%, 67%,” which is a part of Palestine after Palestine New Sites for the Museum Department (2017), focuses on the infamous years of the Nakba (1948) and the occupation of East Jerusalem and the West Bank (1967) by Israeli forces. The years are rendered as percentages, which highlights the overlapping wars of demographics and land being waged in the country on a daily basis. They resemble Pop art sculptures in the vein of Robert Indiana, which we’re accustomed to, but here the declarations make for more sinister markers.

Bob Gramsma’s “facts on the ground, OI#17241” (2017) with the Palestinian Museum in the background

Bob Gramsma’s “facts on the ground, OI#17241” (2017) is equally focused on an imaginary space. The artist has excavated earth and filled the hole with concrete. The resulting cast of negative space is positioned in the Museum’s “Garden of Resistance,” and without knowing the piece’s backstory, it resembles a work of archeology, revealing layers that were previously hidden. I can’t think of a better metaphor for what the best of contemporary art can do in such a contested landscape.

But the most powerful work in the Gardens is Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s “We know what it is for/we who have used it” (2017), which builds on the artist duo’s research into the use of political narratives. Composed of 3D-printed marble masks and a five-channel sound installation, the work focuses on 13 Neolithic masks that may be the oldest known masks in the world. Removed from the West Bank with mysterious provenance, most are currently held in private collections, though two are in the permanent collection of the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, where all 13 were brought together for a 2014 exhibition. According to the artist duo, that exhibition instrumentalized the masks as part of Israel’s Zionist ideology.

Detail of Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s “We know what it is for/we who have used it” (2017)

Considering the history of the Israel Museum, which was designed to mimic the silhouette of a pre-1948 “Arab village,” it’s no surprise that it is a contentious space, displaying artifacts from the region through the lens of a national ideology. All national museums do that, but here, where two narratives are so divergent yet so close together (the two museums are about 18 miles from each other) the contrast is stunning.

The sound component of “We know what it is for/we who have used it” illuminates the objects with stories of the destroyed Palestinian villages in the region. Abbas and Abou-Rahme seem eager to symbolically ‘free’ the masks, but they look more burdened here, like shadows that flicker in and out of focus, objects that seem trapped between the worlds of the living and the dead. In that way, they epitomize the Palestinian Museum’s mission to tell new stories, ones that free history to live, breath, and renew itself through the ritual of storytelling. History in a place like Palestine can sometimes feel insurmountable, but in chimerical works like Abbas and Abou-Rahme’s, it comes alive with possibilities.

Yazan Khalili’s “Falling stone, Flying stone” (2017) is the most visible piece in the show — it sits atop the museum. I had to ask if it was a work at all since it looked so well placed up there, like it was part of the architect’s design for the building. The curator told me the work was incomplete for the opening because the glow-in-the-dark paint that is supposed to cover the surface never cleared Israeli customs. The stone itself references so many parts of Jerusalem’s history: the ancient quarries that continue to thrive today; the stone in the Dome of the Rock where the prophet Muhammad reputedly ascended into heaven; the stone from which a heavenly angel will trumpet out the arrival of Resurrection Day according to Christian lore; and the foundational stone of Judaism for those who believe the patriarch Abraham sacrificed his son Isaac for his monotheism. Khalili’s rock looks like it could topple at any moment, which points to the quixotic nature of national identity, a sense of self that can be burdened or liberated by history, and which feels precarious at all times.

I left the museum thrilled to see this new art institution participating in the formation of a new and continually evolving Palestinian identity, one formed through a connection to the land. It’s ambitious, but I didn’t realize how much of an impact it could have until I left the next day through Ben Gurion Airport in Tel Aviv.

When the Israeli border official questioned me about as to why I was in Ramallah, I was frank. “I was there yesterday to see the Palestinian Museum,” I said. “What kind of art do they show there?” he asked. I replied: “International contemporary artists.” He seemed perplexed. He had never heard of the museum and looked at me blankly until I saw his mind slowly form the thought into something more concrete, and it was obviously something that he had never thought of before.

“Wow, I had no idea” he said. “You should check it out,” I replied, in a manner that was probably too friendly for a border interaction. But he didn’t dismiss the idea like other Israelis I had met on this and a previous trip; the typical reaction to my suggestion is a stern, “I’m not allowed to go there as an Israeli.” That prohibition is only partly true, since no one would check, and many Israelis flaunt the law openly by crossing into lands that on paper appear to be prohibited. But the fact that the border official didn’t fall on that rote answer suggested I had jostled him into imagining something else. I felt the potential of such a museum in that moment.

Jerusalem Lives continues at the Palestinian Museum (Museum Street, off Omar Ibn Al-Khattab Street, Beirzeit, Palestinian Territories) until December 15.

The post A Garden of Possibilities at the Palestinian Museum appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2vLvyCA

via IFTTT

0 notes