#create is his material of choice in how manifest/represent/summon him and his power- hes like that cuz hes deprived </3

Text

qtubbo is a someone born from the love of the universe, ya know the end poem with the 2 'gods' talking? blue and green. tubbos eyes? blue and green. how the gods see the world? very different from those who live in it- how tubbo sees the world? very different from how those 2 gods saw the world but so much more than what other islanders or even the federation see-

tubbos seemingly weather related powers? its how his reality related powers manifest with emotions, but he can bend reality as needs be, need to get through this wall? grab a bike and cycle through- why needs the bike? why do gods need offerings or things that 'hold' or 'guide' their power? cuz it works, just like all the bad luck stuff, power runs on weird rules ok? and tubbo being unseen by anyone but etoiles was slip of control in powers which was unexpected, he got stronger

basically, tubbo is a godling and he can and will break reality because he sees reality as a tangible and mutable thing to a larger extent than anyone around him can (fed keep an eye on him so they can do 'reality checks' or at least they try)

#tubbo#qsmp#tubbo is a literal god and you cannot and will not change my mind#kinda crack theory but honestly im here for it#how does a person be dead for a long time adn also be practically immortal while also leaving corpses behind? why gods of course!#create is his material of choice in how manifest/represent/summon him and his power- hes like that cuz hes deprived </3#not just in messing with it but also in reach- he needs people to know his name and use the things that are his image(create) to sustain-#himself somewhat; can he exist without others or his items? yes. will he thrive in that way? no. he may find a way to make a corner for him#but he would never thrive as he would with people and his things. gods are lonely and thats why they either come with a pantheon or make li#e- they are lonely beings who need others- not really to exist but to thrive when they could not do so alone#they dont need followers; they just need to not be alone#uhhh yea not just a crack idea anymore pfft

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your Power...Your Theme

This post is born because of @waywardtravelerfart asking about a comparison between Semblances (Rwby) and Quirks (BNHA).

In general, I am not a hardcore BNHA fan, though, so I decided to drag other magic systems in this comparison.

So, I will be comparing...

1) Semblances:

2) Quirks:

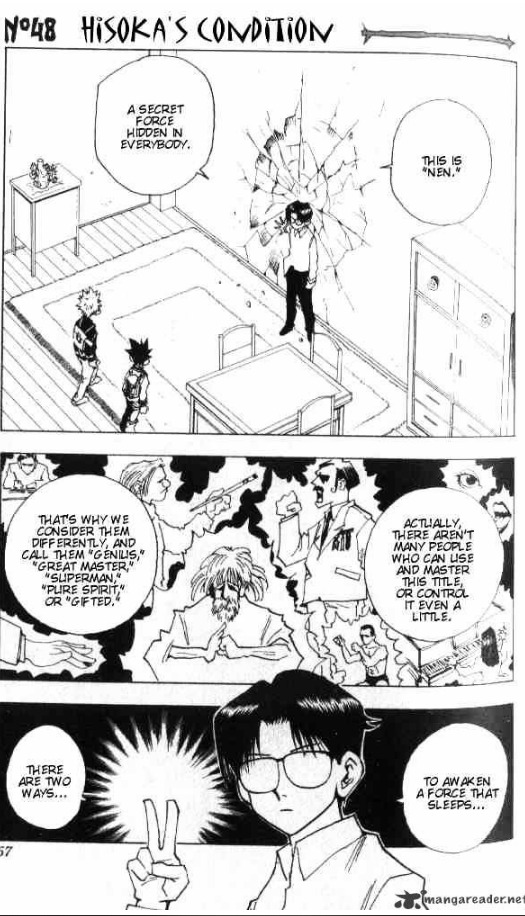

3) Nen (HxH):

4) Abilities (BSD):

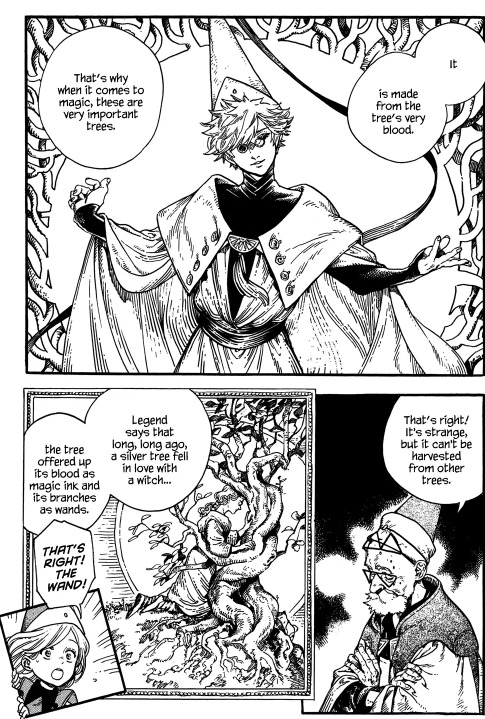

5) Magic (WHA):

Body and Soul

1) & 3)

Pyrrha: Aura is the manifestation of our soul. It bears our burdens and shields our hearts. Have you ever felt you were being watched without knowing that someone was there? With practice, our Aura can be our shield. Everyone has it, even animals.

Nen and Semblances are very similar ideas. Both have their root in the concept of aura aka life force and are trained through specific exercises that are based on martial arts.

More importantly, they are manifestations of a person’s soul.

This is why in both series they are linked to one’s individuality:

Ren: A common philosophy is that a warrior’s Semblance is a part of who they are.

And both Nen and Semblances grow and evolve with the person.

At the same time, both stories focus not only on the soul, but also on the body.

In HxH Gon and Killua must train their bodies just as much as their nen. No matter how much stronger their auras become, they would still be left defenseless if they forget about basic training and if they do not take care of their bodies.

Similarly, Huntsmen and Huntresses in Rwby have both Semblances and Weapons:

By baring your soul outward as a force, you can deflect harm. All of our tools and equipment are conduits for Aura. You protect yourself and your soul when fighting.

Weapons are linked to personalities just like Semblances are:

Ruby: Just weapons? They’re an extension of ourselves! They’re a part of us! Oh, they’re so cool.

It is only through the combination of weapons and semblances that one becomes strong and whole.

In order to experience humanity to its fullest, one needs both a soul:

And a body:

In short, Semblances and Nen are representative of the Soul. They are a physical projection of it. Moreover, they need to be completed by the Body to properly work.

4)

BSD abilities are similar because they clearly symbolize characters’ coping mechanisms.

They are linked to people’s personalities and their effects are highly variegated and impossible to explain through biology alone (for example, a character is able to materialize a whole room in another dimension).

At the same time, they seem to have some physical properties.

For example, it is possible to create artificial abilities and to implant them into people. The process has yet to be properly explained, though.

This can be compared to the research on aura made in Rwby.

That said, this specific research is framed negatively by the narrative because it is an attempt to control what it should not be (a person’s soul).

Similary, in BSD, such experiments are criticized as well because they violate human rights and are an attempt to weaponize abilities, which is an ongoing topic explored by the story.

2)

Quirks are instead framed as the result of biological evolution. This creates an interesting inversion compared to the other stories. Quirks are not simply physical representations of a character’s psychology, but they are a part of the reason why that character develops a specific coping mechanism.

Toga is attracted to blood because her Quirk is about drinking blood, so she naturally likes it.

Shigaraki’s destruction traumatizes him because it leads to his family’s death.

Touya’s weak constitution makes his power difficult to use, hence he develops self-hurting tendencies.

5)

Finally, Magic in WHA is something that exists outside the characters.

It is not something people are born with, but an art they can master through study and dedication.

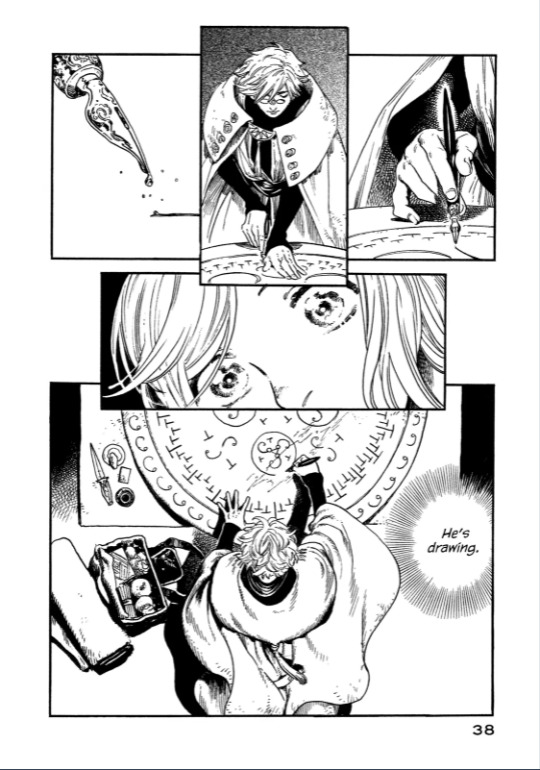

Its origin is still unknown, but it is explained that it works thanks to specific materials:

And even human blood can be used to strengthen it:

In short, Magic is a human art that makes use of specific natural resources and a specific knowledge to create several effects. In a sense, its logic is similar to both art and programming. It is similar to art because the witches need to exercise on drawing and to be creative on their approaches to things. It is similar to programming because they must use what is basically a specific language made of symbols to create different effects.

So, Magic is not linked to a person’s soul in the way other magical systems are, but a character’s personality still emerges from the kind of magic they specialize in. This is something unavoiable... after all this is how personality works in real life as well... we all have different approaches to problems and beliefs that will emerge in our art and in our jobs.

In conclusion, all these magical systems are connected in different ways to characters’ personalities, to their flaws and to their symbolic roles in the narrative.

In these metas, there are some examples of how this happens for HxH, Rwby, BSD and WHA.

Power and Privilege

3) & 5)

Nen and Magic are similar:

With enough training, both powers can be used by everyone.

However, both HxH society and WHA society choose to keep them secret because the damage that could come from sharing this knowledge is potentially devastating.

That said, both stories also show how there is hypocrisy behind this stance.

HxH does so in an indirect way.

Nen is supposed to be secret, so that dangerous people can’t use its power for wrong reasons.

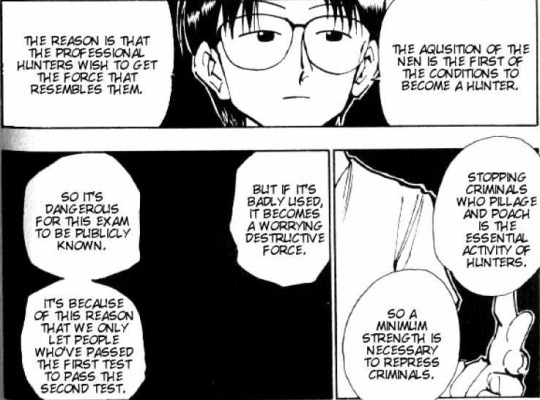

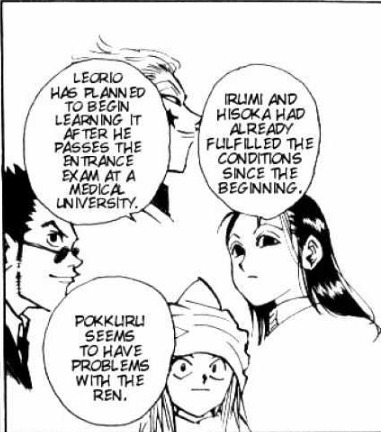

However, many hunters are not really moral people. If anything many are violent and ready to kill. The exam itself encourages these tendencies since it does not punish murderers. Moreover, it turns out that very dangerous people already know about nen:

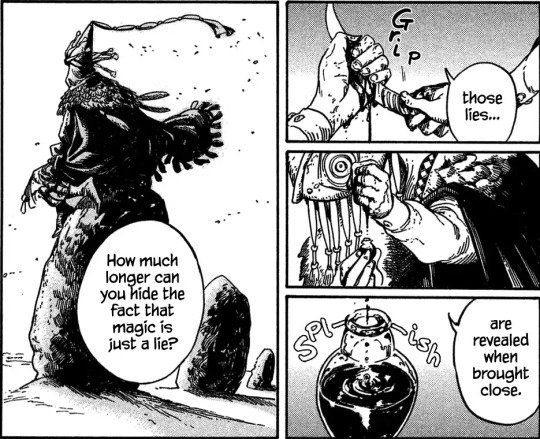

WHA explores this theme more directly:

The secret behind magic creates inequality. Magic could be used to help much more people, but it is limited by the law that imposes witches to keep the secret and forbids them from using magic to heal.

The result is an unjust society and a paradox. Isn’t there another way to use magic that it is less elitarian?

2) Similarly, quirks create inequality in BNHA. However, the mechanisms behind it are slightly different.

Not only people without quirks are discriminated, but also people with specific powers are considered less than others.

This happens either because the power is considered weak or lame or because it is considered a villain power.

In other words, BNHA society nurtures a simplicistic and black and white vision of quirks and people. This leads to some being discriminated for their quirks and to others being excused of everything because of their abilities.

4) In BSD, we have a similar yet partly opposite situation.

Ability users are mostly dehumanized and weaponized by society.

Basically the series explores how society makes use of its more vulnerable members and objectifies them.

So, in BSD having an ability is not really a synomim of privilege, but it is rather something that can set you apart and make you a victim of your country or your organization.

Because of this,the characters struggle to both accept their powers, but also not to be defined by it.

1) Finally, the case of RWBY is interesting because even if society is founded on privilege and inequity, semblances are not really a pivotal part of it.

It is much more common for people to be discriminated because of their bodies (like the Faunus) or their social status than for their semblances. Surely, cases like those exist, but they are not particularly explored by the story.

This might be because semblances are just one of many factors that determine a personal’s stance in society. Moreover, it is not even that clear how much common people know about semblances and aura. I would not say it is exactly a secret, especially because semblances can manifest themselves in a variety of situations. Still, it seems to me that they are mostly aknowledged and accepted by common people, but not exactly pursued or studied.

Symbolically, semblances are linked to an ancient magic that has been forgotten by people. This could tie with why some people, especially in Atlas, have been dismissive of them to an extent. Whitley dismisses his own and is not interested in developing it, while Watts is one of the few characters who fight without a semblance.

It might very well be that human technology and dust make so many different effects possible that a semblance, even if important for a warrior’s own strength and individuality, is not really the only factor that determines the place of a person in society.

In conclusion, all these power systems are linked to privilege in different ways. They are used to explore social inequality or parts of the society that are either repressed or not aknowledged.

Choices and limits

1) 2) & 4)

Quirks, Abilities, Semblances and their limits are not chosen. You are born with them and the most you can do is to try and overcome the limitations or to come up with clever ways to use your power.

You can train your Quirk, so that it becomes stronger.

When it comes to Abilities instead, characters usually must train to control what are potentially dangerous powers.

There are also abilities that help other people to control their powers and modify how these powers work. For example, there is a character whose ability is about summoning a fighting avatar. However, to do so, she needs to be called on a specific phone and it is actually the one calling that commands the avatar. Still, thanks to the influence of the above mentioned ability, she becomes able to summon the avatar at will and does not need the phone anymore.

Finally, in the case of Semblances, you need to meditate and to train your semblance, so that it can evolve. At the same time, though, semblance evolution can happen also because of specifical psychological conditions.

For example, Ren’s Tranquility both activates and evolves not because of physical training, but because of stress (the first time) and emotional growth (the second). This is fitting because his ability has mostly to do with emotions, so it is telling that it evolves as he grows emotionally rather than physically.

Ruby’s semblance is instead a physical one since she is super fast. So it is fitting that it mostly manifests and evolves with her training at using it.

Finally, when it comes to semblances, you do not really choose how they evolve and what new effects you gain. They are mostly an unconscious part of yourself that grows with you.

3) & 5)

The kind of magic you specialize in and the nen power you are gonna have are things one chooses.

To be more specific, they are influenced from one’s talents, but then they evolve according to a person’s choice.

For example, the protagonist Gon has an aura which is particularly good to strengthen things, so he chooses to use it to strengthen his punch. Moreover, he really likes Jankenpon, so he comes up with a power that uses this game. It is a technique that creates different effects depending on what he chooses to “play” (scissors, rock or paper).

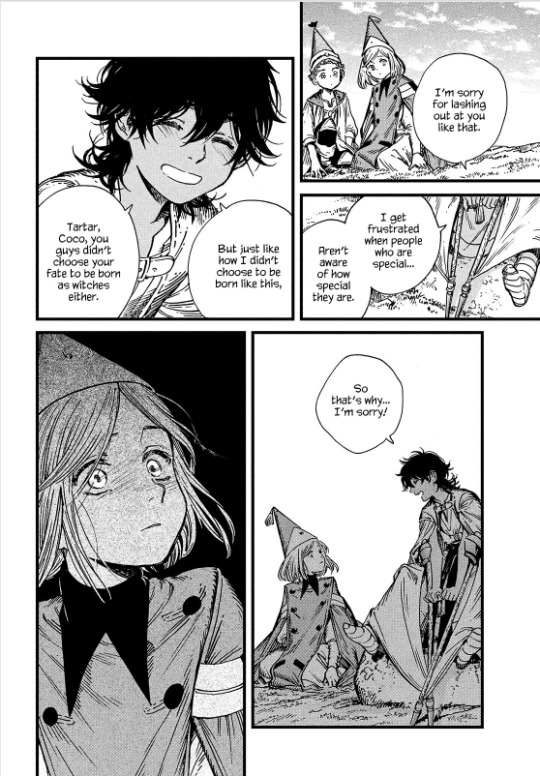

Similarly, Coco is good at drawing straight lines and this makes her good with basic magic, that she uses in original ways because of her thinking outside the box. Her teacher Qifrey instead specializes in water magic because he used to be scared of water when he was little and wanted to overcome this fear.

At the same time, both nen users and witches must face limitations.

Nen has limitations that are self-imposed and decided by the users.

Magic has limitations that are imposed by society and codified through law.

Nen works with the idea that the stronger the limitation you set, the stronger will be your power. Similarly, if you sacrifice something, you can obtain a more powerful effect.

For example, another character called Kurapika creates chains with different powers. One of his chains has the limitation to only work on the members of a specific criminal group. Moreover, if Kurapika breaks this rule, he’ll lose his life. Since the sacrifice Kurapika has decided is pretty extreme, that chain is basically impossible to break.

Of course, limitations do not need to be so extreme. The protagonist’s jankenpon is limited by the fact he says out loud the name of his technique and takes time to use it (both goes against him, since it gives his opponent time to prepare). In this way the power gets stronger.

Magic is a very dangerous force, so it is prohibited to use magic on people’s bodies. This includes the idea that you can’t heal bodies directly or that you can’t change the way you look. It also forbids people from using blood to make magic stronger and to put glyphs on a person’s skin.

These limitations challenge the characters and force them to think outside the box. For example, Coco wants to save her mom who became a stone. The best way to do so is to use magic on her, but this is prohibited hence Coco keeps brainstorming about how she can do it and even thinks about breaking the law multiple times.

In conclusion, powers are often linked to the self and the degree of control and choices characters have on them is symbolic of which part of the self we are talking about.

In the case of semblances and abilities, they mirror an unconscious part.

A Quirk is a biological factor that influences one’s self instead and that everyone can try ot develop in a way they like.

Finally, nen and magic are a conscious part of the self that still mirrors unconscious tendencies.

Not only that, but abilties have limits that come from either outside the person or inside them.

POWER SYSTEMS AND THE FIVE KINDS OF CONFLICT

In stories, there are at least five types of conflict.

1) Man vs Self

2) Man vs Society

3) Man vs Man

4) Man vs Nature

5) Man vs God

The magic systems we explored are linked to at least three of these five types.

Man vs Self

Supernatural abilities are linked to a person’s interiority and personality. Often they are representative of the character’s flaw and their limits can be overcome only by the person’s growth.

Man vs Society

Power systems end up being influenced and influence fictional societies.

They can represent privilege or some wrongdoing in society itself.

Alternatively, they can be limited by society’s rules and imposed laws.

Man vs Man

It is not uncommon to have special powers used in fights. In this case, they become symbolic ways to explore characters’ relationships, themes and different value systems.

This is something that BSD, HxH and Rwby do a lot. WHA has had less fights as for now, but it is definately something that has come up and will come up more in the future. Finally, I am not too much into BNHA to comment on the series, but I would be surprised if it is not the same there as well.

In conclusion, I do not really have much to say on the onthology of powers in different narrative worlds and tbh I do not think this is really what many writers think about when they design them. I think what writers focus on is how to make interesting powers that convey a character’s personality, can be used to explore the world and give life to entertaining fights.

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

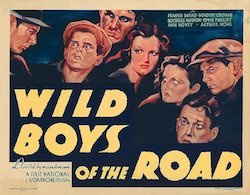

The Crowd Doesn’t Just Roar, It Thinks: Warner Bros.’ All-Talking Revolution

“Iconic” is a gassy word for a masterwork of unquestioned approval. But it also describes compositions that actually resemble icons in their form and function, “stiff” by inviolate standards embodied in, say, Howard Hawks characters moving fluidly in and out of the frame. Whenever I watch William A. Wellman’s 1933 talkie Wild Boys of the Road, these standards—themselves rigid and unhelpful to understanding—fall away. An entire canonical order based on naturalism withers.

To summon reality vivid enough for the 1930s—during which 250,000 minors left home in hopeless pursuit of the job that wasn’t—Wellman inserts whispering quietude between explosions, cesuras that seem to last aeons. The film’s gestating silences dominate the rather intrusive New Deal evangelism imposed by executive order from the studio. Amid Warner Bros.’ ballyhooing of a freshly-minted American president, they were unconsciously embracing the wrecking-ball approach to a failed capitalist system. That is, when talkies dream, FDR don’t rate. However, Marxist revolution finds its American icon in Wild Boys’ sixteen-year-old actor Frankie Darro, whose cap becomes a rude little halo, a diminutive lad goaded into class war by a chance encounter with a homeless man.

“You got an army, ain’t ya?” In the split second before Darro’s “Tommy” realizes the import of these words, the Great Depression flashes before his eyes, and ours. No conspicuous montage—just a fixed image of pain. Until suddenly a collective lurch transmutes job-seeking kids into a polity that knows the enemy’s various guises: railroad detectives, police, galled citizens nosing out scapegoats. Wellman’s crowd scenes are, in effect, tableaux congealing into lucent versions of the real thing. The miracle he performs is a painterly one: he abstracts and pares down in order to create realism.

Wellman has a way of organizing people into palpable units, expressing one big emotional truth, then detonating all that potential energy. In his assured directorial hands, Wild Boys of the Road sustains powerful rhythmic flux. And yet, other abstractions, the kind life throws at us willy-nilly, only make sense if we trust our instinctive hunches (David Lynch says typically brilliant, and typically cryptic, things on this subject).

I’m thinking of iconography that invites associations beyond familiar theories, which, in one way or another, try to give movies syntax and rely too heavily on literary ideas like “authorship.” Nobody can corner the market on semantic icons and run up the price. My favorite hot second in Wild Boys of the Road is when young Sidney Miller spits “Chazzer!” (“Pig!”) at a cop. Even the industrial majesty of Warner Bros. will never monopolize chutzpah. The studio does, however, vaunt its own version of socialism, whether consciously or not, in concrete cinematic terms: here, the crowd becomes dramaturgy, a conscious and ethical mass pushing itself into the foreground of working-class poetics. The crowd doesn’t just roar, it thinks. Miller’s volcanic cri de coeur erupts from the collective understanding that capitalism’s gendarmes are out to get us.

Wellman’s Heroes for Sale, hitting screens the same year as Wild Boys, 1933, further advances an endless catalogue of meaning for which no words yet exist. We’re left (fumblingly and woefully after the fact) to describe a rupture. Has the studio system gone stark raving bananas?! Once again, the film’s ostensible agenda is to promote Roosevelt’s economic plan; and, once again, a radical alternative rears its head.

Wellman’s aesthetic constitutes a Dramaturgy of the Crowd. His compositions couldn’t be simpler. I’m reminded of the “grape cluster” method used by anonymous Medieval artists, in which the heads of individual figures seem to emerge from a single shared body, a highly simplified and spiritual mode of constructing space that Arnold Hauser attributes to less bourgeoise societies.

If the mythos of FDR, the man who transformed capitalism, is just that, a story we Americans tell ourselves, then Heroes for Sale represents another kind of storytelling: one firmly rooted to the soiled experience of the period. Amid portrayals of a nation on the skids—thuggish cops, corrupt bankers, and bone-weary war vets (slogging through more rain and mud than they’d ever encountered on the battlefield)—one rather pointed reference to America’s New Deal drags itself from out of the grime. “It’s just common horse sense,” claims a small voice. Will national leadership ever find another spokesman as convincing as the great Richard Barthelmess, that half-whispered deadpan amplified by a fledgling technology, the Vitaphone? After enduring shrapnel to the spine, dependency on morphine, plus a prison stretch, his character Tom Holmes channels the country’s pain; and his catalog of personal miseries—including the sudden death of his young wife—qualifies him as the voice of wisdom when he explains, “It takes more than one sock in the jaw to lick 120 million people.” How did Barthelmess—owner of the flattest murmur in Talking Pictures, a far distance from the gilded oratory of Franklin Roosevelt, manage to sell this shiny chunk of New Deal propaganda?

How did he take the film’s almost-crass reduction of America’s economic cataclysm, that metaphorical sock on the jaw, and make it sound reasonable? Barthelmess was 37 when he made Heroes for Sale; an aging juvenile who less than a decade earlier had been one of Hollywood’s biggest box-office titans. But no matter how smoothly he seemed to have survived the transition, his would always be a screen presence more redolent of the just-passed Silent-era than the strange new world of synchronized sound. And yet, through a delivery rich with nuance for generous listeners and a glum piquancy for everyone else, deeply informed by an awareness of his own fading stardom, his slightly unsettling air of a man jousting with ghosts lends tremendous force to the New Deal line. It echoes and resolves itself in the viewer’s consciousness precisely because it is so eerily plainspoken, as if by some half-grinning somnambulist ordering a ham on rye. Through it we are in the presence of a living compound myth, a crisp monotone that brims with vacillating waves of hope and despair.

Tom is “The Dirty Thirties.” A symbolic figure looming bigger than government promises, towering over Capitalism itself, he’s reduced to just another soldier-cum-hobo by the film’s final reel, having relinquished a small fortune to feed thousands before inevitably going “on the bum.” If he emits wretchedness and self-abnegation, it’s because Tom was originally intended to be an overt stand-in for Jesus Christ—a not-so-gentle savior who attends I.W.W. meetings and participates in the Bonus March, even hurling a riotous brick at the police. These strident scenes, along with “heretical” references to the Nazarene, were ultimately dropped; and yet the explosive political messages remain.

More than anything, these key works in the filmography of William A. Wellman present their viewers with competing visions of freedom; a choice, if you will. One can best be described as a fanciful, yet highly addictive dream of personal comfort — the American Century's corrupted fantasy of escape from toil, tranquility, and a material luxury handed down from the then-dying principalities of Western Europe — on gaudy, if still wondrous, display within the vast corpus of Hollywood's Great Depression wish-list movies. The other is rarely acknowledged, let alone essayed, in American Cinema. There are, as always, reasons for this. It is elusive and ever-inspiring; too primal to be called revolutionary. It is a vision of existential freedom made flesh; being unmoored without being alienated; the idea of personal liberation, not as license to indulge, but as a passport to enter the unending, collective struggle to remake human society into a society fit for human beings.

In one of the boldest examples of this period in American film, the latter vision would manifest itself as a morality play populated by kings and queens of the Commonweal— a creature of the Tammany wilderness, an anarchist nurse, and a gaggle of feral street punks (Dead End Kids before there was a 'Dead End'). Released on June 24, 1933, Archie L. Mayo's The Mayor of Hell stood, not as a standard entry in Warner Bros.’ Social Consciousness ledger, but as an untamed rejoinder to cratering national grief.

by Daniel Riccuito

Special thanks to R.J. Lambert

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

Beyond the horizon | Art & Culture | thenews.com.pk “I craved to seize the whole essence, in the confines of one single photograph, of some situation that was in the process of unrolling itself before my eyes.” Henri Cartier-Bresson Arif Mehmood’s photographs, a multiple portrait of the humankind, invite us to celebrate the dignity of it. These images of solitude and devotion are brutally frank yet respectful and seemly. Having no relation to the tourism of poverty, they do not violate but penetrate the human spirit in order to reveal it. His is not a macabre, obscene exhibitionism of poverty. It is a poetry of horror because there is a sense of honour. Light is a buried secret, and Mehmood’s photographs tell us that secret. The emergence of the image from the waters of the developer, when the light becomes forever fixed in shadow, is a unique moment that detaches itself from time and is transformed forever. These photographs will live on after their subjects and their author, bearing testimony to the world’s naked truth and hidden splendour, are no more. Mehmood’s camera moves about the violent darkness, seeking light, stalking light. Does the light descend from the sky or rise out of us? That instant of trapped light – that gleam – in the photographs reveals to us what is unseen, what is seen but unnoticed; an unperceived presence, a powerful absence. It shows that concealed within the pain of living and the tragedy of dying there is a potent magic, a luminous mystery that redeems the human adventure in the world. Yet photographers are caught in a curious bind. Cartier-Bresson, who at various times derided the documentary impulse in favour of the visual drama, the pursuit of an unfolding choreography, was well aware of the reality/unreality that one is constantly coming up with, the intermix of fiction and non-fiction. Mehmood’s more consistently documentary approach also has its highly interpretive, imaginary aspects, which, despite the apparent matter-of-factness of photography, give the imagery much of its depth. One might say that, while respecting the facts of a situation, Mehmood attempts to recreate, through visual metaphors, what he sees as its essential human drama – the invisible made visible. Mehmood’s work, while confined to the moment by the mechanics of the camera, is drawn less to celebrating and taming an instant’s arbitrariness, its material manifestations, and more to articulating its eternity, its ephemeral profundity, and to locating a mythic, entwining presence. This aspect of his approach is something he has in common with Latin Americans drawn to what has been called a ‘magical realism’. Similarly, while recognising the individual’s singular importance in his images, he is also quick to draw relationships to the universal. There is, enmeshed in his document of the moment, a resonating lyric, a sense of the epic, an iconic landscape. The former ‘pilot’ invokes a poetic sense of struggles so profound that in his prints, the forces of light and darkness are summoned in scenes reminiscent at times of the most dramatic chiaroscuro. In the history of photography, it has often been debated whether the pictorial photograph can be termed art at all. Indeed, analogue photographs as well as digital are by their very nature traces, not unlike fingerprints. What then does a photographer contribute? The answer also lies in the very nature of what is photographed. It is his frozen view; his orientation to the things in the world that appear significant to him, and equally importantly, the manner in which he represents what he perceives. In fact, no photograph is ever truly objective. Rather, it always constitutes both an abstraction and a subjective perspective, a conscious effort. Until you come of age, photographs that you care to see are often those that other people take of you. Looking at paper copies of anything else is not exciting. Your world is small, and like other children, you live out your days in utter abandon in pursuit of what you need and want. Thought and indecision creep into your life much later. This comfortable equation between oneself and one’s world is imperiled (read shaken) at the age when you get your first camera, suddenly saddled with the obligation to think and to observe. The first major crisis is to make the intractable decision: what should I photograph. It is almost like choosing between my dog and my best friend. The very act of taking that photograph would somehow determine what you hold as most precious: what you ignore would, in future, always be second best.

window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'thumbnails-m', container: 'taboola-mid-article-thumbnails', placement: 'Mid Article Thumbnails', target_type: 'mix' });

Camera is the devil’s own tool: every time you pick it up you become someone else. Just holding his Leica makes Arif Mehmood dissect his universe. It drives him to measure the relative merits of things and people close to his heart, and makes him place value on his most priceless possessions, introducing guilt into his life. Not including someone or something in that foot and a half of celluloid somehow amounts to the betrayal of a relationship. The only members of his inner sanctum to which he wants to accord immortality – without being traumatised – have been his constant companions – ones that he has had the most comfortable and least complex relationships with: PS Pestonjee – the last of the Mohicans; and the ‘friends of God’ – sufi saints, dervishes and devotees. The photographs on display comprised two separate bodies of work: PS Pestonjee – a paean to senility and solitude, and Silver Linings – journeys to sites of mystical Islam taken between 1998 and 2020. Arif Mehmood recalls that his father fell ill in 2016 and passed away in 2019. That inspired him to look at the agile and nimble figure of Pestonjee – only a year older than Mehmood’s father – in comparison. Living in a derelict mansion in Soldier Bazaar, the old Zoroastrian appears to be a sentinel of the dwindling community. With their warm colours, Arif Mehmood’s photographs enchant the artistically sensitive observer. These are works of art with a truly aural character. They allow insights into the everyday culture of the Punjab and Sindh, which is permeated by the Sufi tradition, and as a rule, is concealed from the superficial eye. They reflect the peaceful, almost paradisiacal atmosphere of the saints’ shrines. With these impressions, Mehmood also opens up an alternative to academic verbosity – to the ‘narrative textual paradigm’, in other words, to a distinct predominance of the text over image and object. Veneration of sufi saints can be witnessed in all social strata and permits the individual believer to experience personal, concrete contact with what he deems holy. This is exactly what the photographs exhibited here attempt to do: they aim to initiate a dialogue, also with people familiar with the presented and interpreted cultural environment. They strive to provide aesthetic access beyond the appeal of the exotic observers in order to offer a new understanding of those people and their hopes, ideals and values whose home is interpreted in these photographs. Dedicated to his mother, Mehmood recounts in Silver Linings – the book of photography that accompanied the show – that he first visited Lal Shahbaz Qalandar’s mausoleum in 1998. His work focuses in on the sacred spaces and the people who visit them in search of healing and religious experience. Thus, these photographs are also historical/ethnographic documents of the life of mystic seekers of God. Mehmood’s work invites the observer to experience imaginary, atmospheric wanderings. These are pictures that reveal quietude and contemplation. Through such photographs of a light mystique, he can create a feeling for conditions in which the sufis, pilgrims, mendicants find themselves in the respective situation: meditation, introversion, renunciation and commonality. Some photographs highlight the sufi ideals of simplicity and contentment. The photographs on display in Silver Linings are not necessarily shot to illustrate a theme. They were taken as individual photographs of separate lives. If there is a common thread that runs through them, it is the manner of their making and the period in the photographer’s life that they represent. These images were exposed both on negative film and digitally, when in 1998 Mehmood picked up his camera again after a year-long sabbatical from the medium. The abstinence was self-ordained, provoked by an internalised process of deliberation that had begun to question “what do I photograph, how do I photograph it, and even why do I photograph at all.” He paused in an effort to distance himself from his personal work, to pull the photographic idiom decisively away from the compulsion to speak a universally cogent language, and instead, bring his own grammar as close as he could to the common detail in his life and to the lives of others. This episode is yet another example of the power that photography wields in constructing one’s own personal equations. More than to show, Arif Mehmood shoots to see. If anything, his photographs heighten the banality of their detail. Vulnerability is just another element that determines the choices individuals make in their lives as they willingly shoulder the burden of their own minds. What Pestonjee chooses to allow into his inner sanctum; what he chooses to lock himself into or out of; how long he subjects himself to the vision of a lingering past; whether memories will come alive to the geometry and colour about them; whether they will enter the green windows along their way or pass them by; whether they will step out of the shade to accept their right; whether they are willing to upturn their ‘wheelbarrows’. It is the making of these choices that Mehmood waits to see in his frames. These photographs are a ‘temporary’ record of fleeting insights into the lives of others. Like reality, like himself, like the subjects, like PS Pestonjee, they too, in time, will fade. The writer is an art critic based in Islamabad https://timespakistan.com/beyond-the-horizon-art-culture-thenews-com-pk/13070/?wpwautoposter=1615698021

0 notes

Text

How To Use The Cups Tarot Cards In Magic

SL Bear

Tarot card spells are becoming more popular as time goes on. These cards have transformed from handy divination tool to a means of working magic, from simply a way to discover information about your life to a way of actually impacting it. Having these incredibly specific archetypal energies at our disposal can be empowering but it can also be paralysing.

How do you actually choose which cards to use for your spells? Do you stick to only using the Major Arcana? You can, but then you’re leaving a full 56 cards and all of their power on the table, completely untapped. Today, we’re going to take a look at the ways you can use the Minor Arcana to work magic, specifically focusing on the emotional realm of the cups cards.

(Psst, if you want the FREE expanded reference book of cups card spell uses complete with reversals, stick around until the end of the post!)

King of Cups

This card is about balancing emotions, not suppressing them, about creativity and the mind — a connection between thought and feeling. This is a strong card to use in spells contacting spirits and asking for guidance. It’s also useful for bringing clarity where there is confusion in terms of spirituality. This card is heavily associated with Pisces, and those born under the sign of the fish will find this card unusually helpful.

Queen of Cups

If you work in a field that focuses on helping others, like nursing for example, the Queen of Cups is your patron and can be carried with you to remind you to take care of yourself as well as you take care of others. In spells, the Queen of Cups can be used to summon a nurturing woman into your life when you need it the most, or perhaps rebuild a crumbling relationship with your mother. She can also be used in spells to help take care of your inner child, an energy many of us tend to ignore as we grow older and more consumed with our strenuous day-to-day.

Knight of Cups

This knight is a romantic at heart, and in spellwork, can be used to summon a new lover. If you’re done with all the nonsense and immaturity of other suitors, call on the Knight in a love spell and make sure to add a bit of gold — preferably a ring. As a messenger, the Knight of Cups traditionally represents the arrival of good news, specifically news that will make you very happy, further adding to his association with new love. The Knight represents creativity and can be used in motivational spells when starting a new, heartfelt project — particularly writing. For romance writers, he is an essential companion and brings that special touch to make your readers swoon.

Page of Cups

This is another Cup with a strong link to inspiration, creativity, and new ideas. However, where the Knight is a romantic, the Page is more light-hearted — one who lives in dreams and fairytales. A generous assistant for all fantasy writers and abstract artists. Keep the Page of Cups in your pillowcase and seek out inspiration for projects in your dreams — the playground of your subconscious. Because of this card’s association with fish and happy surprises in general, it can be used in spells directed at women and couples hoping to become pregnant.

Ten of Cups

This is a happy card that symbolises contentment, joy, and wishes coming true. However, this isn’t about material things; this card represents personal fulfilment and feeling at peace with what you already have. This makes it a great card to use in gratitude spells and on your altar as a way to show you are thankful for all you have in life. Brew your favourite coffee or tea or hot chocolate — something warm. With the Ten of Cups close, fill a cup a little each time you think of something you’re grateful for. Once the cup is full, and you have acknowledged all the good in your life, drink the liquid and let the warmth of gratitude wash through your whole being.

Nine of Cups

The wish card. This card represents satisfaction and success after a struggle. In spellwork, this card can be paired with The Star to make wishes come true. Place under your pillow with a little mugwort and pin The Star card above your head wherever you sleep. Before you go to sleep, focus on what you really want. When you wake in the morning, reanalyse your wish and if it has not changed, hold the Nine of Cups and make your wish. This should be the first thing you say that day. Keep an eye out for manifestations of this wish coming true, like seeing the same time whenever you look at the clock, or suddenly hearing people talking about what you want in everyday conversations.

Eight of Cups

This card can represent two things; letting go of the material and moving onto more spiritual aspirations or letting go of something in your life that no longer brings you satisfaction. That makes this card excellent for spellwork focused on yourself.

Gather together symbols of your current life, especially those things that have gotten old or useless to you, like a job or relationship. Tie these symbols together with a cord and hang them over the Eight of Cups. Now it’s time to let go! Cut each one free with a knife until these old symbols are scattered around the Eight of Cups. Now create a new chain of symbols that represent things you want to replace what you’ve just cut free. A new job? Tie on a business card or application. A change of scenery? Add a picture of where you want to travel to the chain. Hang this chain some place you’ll see it every day and keep the Eight of Cups close as a reminder that you must change in order to grow, and let old things go so new, better things can come in to your life!

Seven of Cups

In the Seven of Cups, a dreamer sees seven options and fantasies in front of him — everything from victory and riches, to snakes and monsters representing the dreams we chase, or the demons we let haunt us — constantly living in the clouds instead of reality. Because this card is focused on our thoughts more than reality, you’ll only need to work with mental magic for spellwork with this card. Look at the symbols in each of the seven cups and personalise them. Maybe the castle represents having a space of your own. Maybe the dragon represents a bad memory or fear. Do you want to take the time and finally face the things that bother you? Or maybe it’s time to focus on how to make one of your most sought after dreams a reality. Meditate on this card. Let it speak to you and make sure you listen to your own winding thoughts for the answer. It’s time to focus.

Six of Cups

This card represents family, stability, home, and happiness. It can be used to bring a reunion between old friends or family you’ve grown apart from — or even re-establish a connection with the person you used to be. Gather photographs of an old acquaintance and shuffle them together with the Six of Cups. Light a yellow candle and flip through the photographs. Pick a photo that best represents this person’s true self, and place it on top of the Six of Cups, then add a lodestone on top of the photo. Let the yellow candle burn while you envision different ways this person could re-enter your life. If you can’t think of any available options, ask for new pathways to make this possible during the spell.

Five of Cups

This suit is an emotional one, and the Five of Cups represents our worst feelings of grief, loss and disappointment. In times of strife, it’s hard to remember that we have choices. We can wallow and allow sadness to keep us down, or we can learn and become better.

Four of Cups

Another emotionally heavy card symbolising apathy, depression, and stagnation. This card is useful, though, as a reminder that if we don’t move forward we don’t get anywhere and worse, we may miss opportunities that could truly make us happy. Pair this card with anise and go someplace peaceful. Allow yourself to feel your emotions. Vent if you need to, journal, or just sit and reflect on whatever’s causing you pain in this moment. Then return home and put this card away. The goal is not to block out painful things, but to feel them, re-evaluate, and grow more resilient in spite of them.

Three of Cups

This is a card of celebration, good times with friends, and victory. Use this card in spells when you feel like having fun or want to make a party great — particularly weddings, where many of your family and friends will be in attendance. Light an orange candle and place this card before it. Sprinkle some oregano into the flame and say a date to ensure the party is a blast. Pair with turquoise in spells to bring about a personal victory.

Two of Cups

This card depicts a ceremony between two people and represents a union or harmony in a partnership. Many see this card as a representation of love, and it certainly can be read that way — used in spells to strengthen marriages or romantic relationships. However, I believe that limits this card’s potential. The Two of Cups is about a strong connection, equality, and mutual respect. So I suggest using this card to strengthen any kind of bond between two people, paired with another card or symbol to clarify your intention. If you’re working a friendship spell, add the Three of Cups. If the spell focuses on a business partnership, pair this card with the Emperor.

Ace of Cups

The Ace in any suit embodies the pure strength of that suit. The Ace of Cups is emotional fulfilment, stability and happiness in its most powerful form. A card to use in spells when you need to find balance, peace or instant joy. This is also the card of intuition and listening to your inner voice. When paired with a water element and labradorite, this card will heighten your intuition and make your divination skills stronger.

Now, when this article was being written we got a little excited and came up with way, WAY more information that we originally intended. There was no way to cram it all in one blog post!

Instead we decided to create a PDF of the expanded version with way more spells, details, and reversals for you to use in your witchcraft. Sound good?

https://thetravelingwitch.com/blog/how-to-use-the-cups-tarot-cards-in-magic

0 notes

Text

Reframing the Bad Boy Masculinity

Within Young Adult literature, young women and men are often bombarded with images of a ruthless and abusive masculinity that is presented as desirable. This image plays into all the most pervasive and disgusting aspects of modern masculinity construction, perpetuating the idea that a boy who treats you poorly simply needs saving by a soft, feminine woman. This masculinity, the bad boy persona, ignores the social construction of gender, how “our behaviors are not simply ‘just human nature,’ because ‘boys will be boys.’ From the materials we find around us in our culture – other people, ideas, object – we actively create our world, our identities” (Kimmel, 135). Within the recent novel A Court of Mist and Fury, the second in a series by Sarah J. Mass, two images of constructed masculinity are presented. The main character, Feyre, is involved with Tamlin at the beginning of the novel, the man she fell in love with in the first novel. Tamlin is the spitting image of the old bad boy masculinity: dangerous, sexy because he is dangerous, completely in control, and stoic. As the novel progresses, Tamlin’s behavior grows more abusive and Feyre eventually leaves him after being rescued by Rhysand. At Rhysand’s court, Feyre heals from her experience and becomes a powerful warrior who bows to no one. This healing is helped along by Rhys, who she begins to fall in love with. Rhys is like and unlike Tamlin: dangerous, but tries to hide it to avoid making people uncomfortable; sexy because he is strong, compassionate, and dangerous; a ruler who controls his court while accepting council from a close knit group of friends; stoic due to being a rape victim, but willing to discuss his feelings about his trauma to a certain extent. While the two masculinities presented in the novel appear similar, the differences in the stereotypical masculine characteristics reveal a new kind of masculinity that incorporates some femininity and performs male-ness in a healthier and less violent way.

Much of gender theory engages with destabilizing and deconstructing biological gender determination and the elements within masculinity which perpetuates the subjugation of the feminine and female. Pascoe, in an essay titled “What Do We Mean, Masculinity?” posits masculinity as a certain set of behaviors that can be applied to both men and women. There is a division between being male identifying and being masculine. Using this theorization of masculinity as behaviors, the actions of Tamlin and Rhysand can be divided into elements of the bad boy persona and then analyzed individually. When the traits of their masculine construction are examined side by side, they are revealed to be different in important and nuanced ways. The masculinity presented by Tamlin falls into the category of bad boy masculinity that relies upon violence, control, and lack of emotions to maintain its power. Rhysand’s masculinity reveals a masculine identity built using elements of traditional femininity. The incorporation of masculinity and femininity creates a unique masculine identity that does not rely upon patriarchal power structures for validation. Rhysand’s exhibition of feminine coded traits displays the redemptive qualities of the masculinity he represents. Modern American masculinity has been termed Marketplace Masculinity by Michael Kimmel, and hinges upon the rejection of the feminine through the oppression of women and homosexual men, as well as any other group that the Marketplace Man can exert control over. Rhysand’s masculine construction presses against this assumption that femininity leads to weakness, and creates an altogether better adjusted individual than the Marketplace Masculinity, which can be represented by Tamlin.

The presentation of aggression and forcefulness, defining features of modern masculinity, first occupies a violent, abusive register in Tamlin, before transforming into a controlled and respectful power through Rhysand. Both Tamlin and Rhys are High Fae, a race of faerie with magic and primal, sometimes animalistic instincts. This coding of males with instincts they cannot always ignore at first feels uncomfortably like the argument that women must be chaste for men cannot control their sexual urges. Yet the way each of them handle this biological programing reveals the redemptive masculinity that Rhys represents, as well as the insubstantiality of this argument about male urges. When Feyre tries to discuss how Tamlin’s control of her causes her to feel as though she is drowning, she observes “Nothing in those eyes, that face. But then – I cried out, instinct taking over as his power blasted through the room” (Maas, 99-100). In his rage, Tamlin utterly destroys the room they are in. If Feyre hadn’t instinctively shielded herself with a force field of air, she would have been severely injured, if not killed. After his explosion, Tamlin expresses remorse, “‘I’ll try,’ he breathed. ‘I’ll try to be better. I don’t … I can’t control it sometimes. The rage’” (Maas, 102). His half-hearted apology, rather than taking full responsibility for his actions, displaces the blame onto his instincts and his own biological inability to control them. Yet with Rhys these Fae instincts are no excuse for his actions. After forming a mating bond with Feyre, he discusses with her how “I’d like to believe I have more restraint than the average male, but … Be patient with me, Feyre, if I’m a little on edge” (Maas, 541). He warns her of his instincts to protect her and keep her from other males, but instead of asking her to excuse it, he asks for patience. There is an implicit declaration that he will fight to avoid being territorial over her. Further, she should not let him get away with it, simply be patient when reminding him to not suffocate her. Rhys’s version of masculinity questions the connection between masculinity and aggression that is presented as biologically essential by Tamlin’s construction of his masculine identity.

Protective instincts are coded as an essential part of masculine identity, but the manifestation of these instincts and the subsequent actions reveals the controlling nature of the typical bad boy persona. Tamlin’s protective instincts are an integral part of his personality, and he continually tells Feyre “I can’t do what I need to do if I’m worrying about whether you’re safe” (Maas, 11). Rather than it being his job to manage the fear for Feyre’s well-being, Tamlin places the responsibility upon Feyre to change her actions to cater to Tamlin’s overprotective nature. This power relationship is reversed in Rhys, and Feyre observes “I might have loved him for that – for not insisting I stay even if it drove his instincts mad, … I realized how badly I’d been treated before, if my standards had become so low. If the freedom I’d been granted felt like a privilege and not an inherent right” (Maas, 577). Rhys lets Feyre make her own choices, no matter how nervous they make him. Feyre herself compares the behavior of the two men and realizes how controlled, how suffocated she was by Tamlin’s own feelings and needs. This construction of respectful protection is extended to two of Rhys’s male councilors. Feyre asks him how to tell the men she doesn’t need protection, to which Rhys replies “You don’t tell them. You set boundaries if they cross a line, but you are their friend – and my mate. They will protect you on instinct. If you kick heir asses out of the house, they’ll just sit on the roof” (Maas, 557). The relationship set up is one of mutual give and take. Feyre sets boundaries of how much they are allowed to protect her, and if they cross them, she can ask them to leave. Likewise, the protective instincts of the two men are forced to give way under her need to feel free, but they are allowed to simply move their protection outwards so she is less smothered. The feelings and needs of both parties are respected and meet in a compromise that allows Feyre freedom and the two men their protection of her. The rewriting of masculine protection allows it to transform into a need based in love, that is not necessarily male-coded, and that must compromise with the protected subject’s freedom.

Traditional masculinity defines itself through a rejection of emotions, a definition that is shown to create unhealthy relationships without communication. In his relationship with Feyre, Tamlin is unwilling to engage in conversation about difficult topics. Both Feyre and Tamlin have nightmares from a past trauma, yet every night that Feyre jerks away to throw up Tamlin remains asleep, and Feyre suspects he is simply pretending. Further, he refuses to discuss his own nightmares with her, and gets angry when she brings the topic up. This repeats later when Feyre asks about Tamlin’s feelings on a difficult topic. She states that “I dared meet his eyes. Temper flared in them. But he said, ‘We’re not talking about me. We’re talking – about you’” (Maas, 99). Even before seeing the anger in his eyes, Feyre knows it will be there, having to summon bravery and daring to meet his gaze. Tamlin presents a masculine identity that is incapable of showing any sign of ‘weakness’ and refuses to engage in emotional healing with Feyre. In contrast, Rhys regularly discusses emotions and past trauma with Feyre, for her sake and his own. After Feyre admits to hating herself, he tells her he felt the same way when he couldn’t prevent the deaths of his mother and sister. He then tells her “You can either let it wreck you, let it get you killed like it nearly did with the Weaver, or you can learn to live with it” (Maas, 298). His masculine identity does not hinge upon remaining within the stereotype of the stoic protector without feelings, on the contrary, his narrative includes moments of intense emotional vulnerability. This rewriting of the stereotypical bad boy persona creates a masculinity that can still be strong and dangerous without sacrificing emotional capacity.

Masculinity within the novel is constructed to demonstrate the toxicity within the gender definition that requires a superiority to women. This necessity of masculine superiority has been observed as an intrinsic part of masculine definition: “The hegemonic definition of manhood is a man in power, a man with power, and a man of power. We equate manhood with being strong, successful, capable, reliable, in control. The very definitions of manhood we have developed in our culture maintain the power that some men have over other men and that men have over women” (Kimmel, 137). Tamlin represents this old version of masculinity; he is lord over everything in his court, including Feyre, and exercises this complete control liberally. Feyre sends him a letter informing him she has left and is not coming back, yet he sends his head guard, Lucien, to hunt her down and bring her back, no matter what. As Feyre was previously going to marry him, Tamlin views her as his possession and has no qualms about kidnapping her to facilitate the return to him of his property. This superiority to Feyre, and women in general, is expressed when he states that “High Lords only take wives. Consorts. There has never been a High Lady” (Maas, 24). He sees no issues with this structure of power, that Feyre will never hold a position equal to his own. That as a woman she cannot rule. Yet the necessity of this structure of power is revealed to be merely male domination and tradition when Rhys tells his court “‘Not consort, not wife. Feyre is High Lady of the Night Court.’ My equal in every way; she would wear my crown, sit on a throne beside mine. Never sidelined, never designated to breeding and parties and child-rearing. My queen” (Maas, 621). This is the only chapter for which his point of view is presented, and his thoughts about Feyre reflect the destruction of gender roles and traits that Rhysand’s character has been demonstrating throughout the novel. By showing the ease with which Rhys still reads as masculine, the novel refutes the supposed necessity of superiority to women within traditional masculinity construction.

Within A Court of Mist and Fury, the gender construction of the two main male characters reveals the ridiculous nature of much of hegemonic, unhealthy masculinity. By breaking down the defining qualities of typical masculinity and comparing the ways Tamlin and Rhysand manifest or transform these traits, it becomes clear that Sarah J. Maas’s novel is engaging in gender theorizing. The necessity of a masculinity formulated around the oppression of women is refuted, and a new masculinity takes shape through the character of Rhysand. By showing a male love interest who does not rely upon toxic masculinity, the attractiveness of that persona of masculinity is questioned. Rhysand, who is far more loving and supportive than Tamlin, does not sacrificing any of the necessary sex appeal for a romance novel love interest. The ease with which Rhysand exhibits both masculine and feminine characteristics questions the division of gendered identities that is a given within our society’s picture of male and female identities. While there is still a reliance upon elements of traditional masculine construction, it can be figured as due to Rhysand’s own gender definition, rather than one based within biological gender.

Works Cited

Kimmel, Michael S. “Masculinity as Homophobia.” In The Social Construction of Difference and Inequality: Race, Class, Gender, and Sexuality, 5th edition, edited by Tracy Ore, 134-151. New York: McGraw Hill, 2011.

Maas, Sarah J. A Court of Mist and Fury. New York: Bloomsbury Children’s Books, 2016.

Pascoe, C. J. “What Do We Mean by Masculinity?” In Dude, You’re a Fag. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

0 notes

Link

Beyond the horizon | Art & Culture | thenews.com.pk “I craved to seize the whole essence, in the confines of one single photograph, of some situation that was in the process of unrolling itself before my eyes.” Henri Cartier-Bresson Arif Mehmood’s photographs, a multiple portrait of the humankind, invite us to celebrate the dignity of it. These images of solitude and devotion are brutally frank yet respectful and seemly. Having no relation to the tourism of poverty, they do not violate but penetrate the human spirit in order to reveal it. His is not a macabre, obscene exhibitionism of poverty. It is a poetry of horror because there is a sense of honour. Light is a buried secret, and Mehmood’s photographs tell us that secret. The emergence of the image from the waters of the developer, when the light becomes forever fixed in shadow, is a unique moment that detaches itself from time and is transformed forever. These photographs will live on after their subjects and their author, bearing testimony to the world’s naked truth and hidden splendour, are no more. Mehmood’s camera moves about the violent darkness, seeking light, stalking light. Does the light descend from the sky or rise out of us? That instant of trapped light – that gleam – in the photographs reveals to us what is unseen, what is seen but unnoticed; an unperceived presence, a powerful absence. It shows that concealed within the pain of living and the tragedy of dying there is a potent magic, a luminous mystery that redeems the human adventure in the world. Yet photographers are caught in a curious bind. Cartier-Bresson, who at various times derided the documentary impulse in favour of the visual drama, the pursuit of an unfolding choreography, was well aware of the reality/unreality that one is constantly coming up with, the intermix of fiction and non-fiction. Mehmood’s more consistently documentary approach also has its highly interpretive, imaginary aspects, which, despite the apparent matter-of-factness of photography, give the imagery much of its depth. One might say that, while respecting the facts of a situation, Mehmood attempts to recreate, through visual metaphors, what he sees as its essential human drama – the invisible made visible. Mehmood’s work, while confined to the moment by the mechanics of the camera, is drawn less to celebrating and taming an instant’s arbitrariness, its material manifestations, and more to articulating its eternity, its ephemeral profundity, and to locating a mythic, entwining presence. This aspect of his approach is something he has in common with Latin Americans drawn to what has been called a ‘magical realism’. Similarly, while recognising the individual’s singular importance in his images, he is also quick to draw relationships to the universal. There is, enmeshed in his document of the moment, a resonating lyric, a sense of the epic, an iconic landscape. The former ‘pilot’ invokes a poetic sense of struggles so profound that in his prints, the forces of light and darkness are summoned in scenes reminiscent at times of the most dramatic chiaroscuro. In the history of photography, it has often been debated whether the pictorial photograph can be termed art at all. Indeed, analogue photographs as well as digital are by their very nature traces, not unlike fingerprints. What then does a photographer contribute? The answer also lies in the very nature of what is photographed. It is his frozen view; his orientation to the things in the world that appear significant to him, and equally importantly, the manner in which he represents what he perceives. In fact, no photograph is ever truly objective. Rather, it always constitutes both an abstraction and a subjective perspective, a conscious effort. Until you come of age, photographs that you care to see are often those that other people take of you. Looking at paper copies of anything else is not exciting. Your world is small, and like other children, you live out your days in utter abandon in pursuit of what you need and want. Thought and indecision creep into your life much later. This comfortable equation between oneself and one’s world is imperiled (read shaken) at the age when you get your first camera, suddenly saddled with the obligation to think and to observe. The first major crisis is to make the intractable decision: what should I photograph. It is almost like choosing between my dog and my best friend. The very act of taking that photograph would somehow determine what you hold as most precious: what you ignore would, in future, always be second best.

Camera is the devil’s own tool: every time you pick it up you become someone else. Just holding his Leica makes Arif Mehmood dissect his universe. It drives him to measure the relative merits of things and people close to his heart, and makes him place value on his most priceless possessions, introducing guilt into his life. Not including someone or something in that foot and a half of celluloid somehow amounts to the betrayal of a relationship. The only members of his inner sanctum to which he wants to accord immortality – without being traumatised – have been his constant companions – ones that he has had the most comfortable and least complex relationships with: PS Pestonjee – the last of the Mohicans; and the ‘friends of God’ – sufi saints, dervishes and devotees. The photographs on display comprised two separate bodies of work: PS Pestonjee – a paean to senility and solitude, and Silver Linings – journeys to sites of mystical Islam taken between 1998 and 2020. Arif Mehmood recalls that his father fell ill in 2016 and passed away in 2019. That inspired him to look at the agile and nimble figure of Pestonjee – only a year older than Mehmood’s father – in comparison. Living in a derelict mansion in Soldier Bazaar, the old Zoroastrian appears to be a sentinel of the dwindling community. With their warm colours, Arif Mehmood’s photographs enchant the artistically sensitive observer. These are works of art with a truly aural character. They allow insights into the everyday culture of the Punjab and Sindh, which is permeated by the Sufi tradition, and as a rule, is concealed from the superficial eye. They reflect the peaceful, almost paradisiacal atmosphere of the saints’ shrines. With these impressions, Mehmood also opens up an alternative to academic verbosity – to the ‘narrative textual paradigm’, in other words, to a distinct predominance of the text over image and object. Veneration of sufi saints can be witnessed in all social strata and permits the individual believer to experience personal, concrete contact with what he deems holy. This is exactly what the photographs exhibited here attempt to do: they aim to initiate a dialogue, also with people familiar with the presented and interpreted cultural environment. They strive to provide aesthetic access beyond the appeal of the exotic observers in order to offer a new understanding of those people and their hopes, ideals and values whose home is interpreted in these photographs. Dedicated to his mother, Mehmood recounts in Silver Linings – the book of photography that accompanied the show – that he first visited Lal Shahbaz Qalandar’s mausoleum in 1998. His work focuses in on the sacred spaces and the people who visit them in search of healing and religious experience. Thus, these photographs are also historical/ethnographic documents of the life of mystic seekers of God. Mehmood’s work invites the observer to experience imaginary, atmospheric wanderings. These are pictures that reveal quietude and contemplation. Through such photographs of a light mystique, he can create a feeling for conditions in which the sufis, pilgrims, mendicants find themselves in the respective situation: meditation, introversion, renunciation and commonality. Some photographs highlight the sufi ideals of simplicity and contentment. The photographs on display in Silver Linings are not necessarily shot to illustrate a theme. They were taken as individual photographs of separate lives. If there is a common thread that runs through them, it is the manner of their making and the period in the photographer’s life that they represent. These images were exposed both on negative film and digitally, when in 1998 Mehmood picked up his camera again after a year-long sabbatical from the medium. The abstinence was self-ordained, provoked by an internalised process of deliberation that had begun to question “what do I photograph, how do I photograph it, and even why do I photograph at all.” He paused in an effort to distance himself from his personal work, to pull the photographic idiom decisively away from the compulsion to speak a universally cogent language, and instead, bring his own grammar as close as he could to the common detail in his life and to the lives of others. This episode is yet another example of the power that photography wields in constructing one’s own personal equations. More than to show, Arif Mehmood shoots to see. If anything, his photographs heighten the banality of their detail. Vulnerability is just another element that determines the choices individuals make in their lives as they willingly shoulder the burden of their own minds. What Pestonjee chooses to allow into his inner sanctum; what he chooses to lock himself into or out of; how long he subjects himself to the vision of a lingering past; whether memories will come alive to the geometry and colour about them; whether they will enter the green windows along their way or pass them by; whether they will step out of the shade to accept their right; whether they are willing to upturn their ‘wheelbarrows’. It is the making of these choices that Mehmood waits to see in his frames. These photographs are a ‘temporary’ record of fleeting insights into the lives of others. Like reality, like himself, like the subjects, like PS Pestonjee, they too, in time, will fade. The writer is an art critic based in Islamabad

window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'thumbnails-b', container: 'taboola-below-article-thumbnails', placement: 'Below Article Thumbnails', target_type: 'mix' });

https://timespakistan.com/beyond-the-horizon-art-culture-thenews-com-pk/13070/?wpwautoposter=1615694408

0 notes

Link

Beyond the horizon | Art & Culture | thenews.com.pk “I craved to seize the whole essence, in the confines of one single photograph, of some situation that was in the process of unrolling itself before my eyes.” Henri Cartier-Bresson Arif Mehmood’s photographs, a multiple portrait of the humankind, invite us to celebrate the dignity of it. These images of solitude and devotion are brutally frank yet respectful and seemly. Having no relation to the tourism of poverty, they do not violate but penetrate the human spirit in order to reveal it. His is not a macabre, obscene exhibitionism of poverty. It is a poetry of horror because there is a sense of honour. Light is a buried secret, and Mehmood’s photographs tell us that secret. The emergence of the image from the waters of the developer, when the light becomes forever fixed in shadow, is a unique moment that detaches itself from time and is transformed forever. These photographs will live on after their subjects and their author, bearing testimony to the world’s naked truth and hidden splendour, are no more. Mehmood’s camera moves about the violent darkness, seeking light, stalking light. Does the light descend from the sky or rise out of us? That instant of trapped light – that gleam – in the photographs reveals to us what is unseen, what is seen but unnoticed; an unperceived presence, a powerful absence. It shows that concealed within the pain of living and the tragedy of dying there is a potent magic, a luminous mystery that redeems the human adventure in the world. Yet photographers are caught in a curious bind. Cartier-Bresson, who at various times derided the documentary impulse in favour of the visual drama, the pursuit of an unfolding choreography, was well aware of the reality/unreality that one is constantly coming up with, the intermix of fiction and non-fiction. Mehmood’s more consistently documentary approach also has its highly interpretive, imaginary aspects, which, despite the apparent matter-of-factness of photography, give the imagery much of its depth. One might say that, while respecting the facts of a situation, Mehmood attempts to recreate, through visual metaphors, what he sees as its essential human drama – the invisible made visible. Mehmood’s work, while confined to the moment by the mechanics of the camera, is drawn less to celebrating and taming an instant’s arbitrariness, its material manifestations, and more to articulating its eternity, its ephemeral profundity, and to locating a mythic, entwining presence. This aspect of his approach is something he has in common with Latin Americans drawn to what has been called a ‘magical realism’. Similarly, while recognising the individual’s singular importance in his images, he is also quick to draw relationships to the universal. There is, enmeshed in his document of the moment, a resonating lyric, a sense of the epic, an iconic landscape. The former ‘pilot’ invokes a poetic sense of struggles so profound that in his prints, the forces of light and darkness are summoned in scenes reminiscent at times of the most dramatic chiaroscuro. In the history of photography, it has often been debated whether the pictorial photograph can be termed art at all. Indeed, analogue photographs as well as digital are by their very nature traces, not unlike fingerprints. What then does a photographer contribute? The answer also lies in the very nature of what is photographed. It is his frozen view; his orientation to the things in the world that appear significant to him, and equally importantly, the manner in which he represents what he perceives. In fact, no photograph is ever truly objective. Rather, it always constitutes both an abstraction and a subjective perspective, a conscious effort. Until you come of age, photographs that you care to see are often those that other people take of you. Looking at paper copies of anything else is not exciting. Your world is small, and like other children, you live out your days in utter abandon in pursuit of what you need and want. Thought and indecision creep into your life much later. This comfortable equation between oneself and one’s world is imperiled (read shaken) at the age when you get your first camera, suddenly saddled with the obligation to think and to observe. The first major crisis is to make the intractable decision: what should I photograph. It is almost like choosing between my dog and my best friend. The very act of taking that photograph would somehow determine what you hold as most precious: what you ignore would, in future, always be second best.

window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'thumbnails-m', container: 'taboola-mid-article-thumbnails', placement: 'Mid Article Thumbnails', target_type: 'mix' });