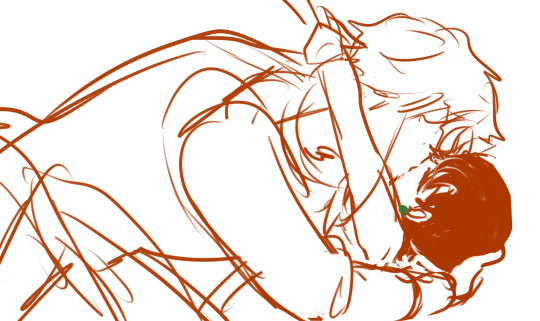

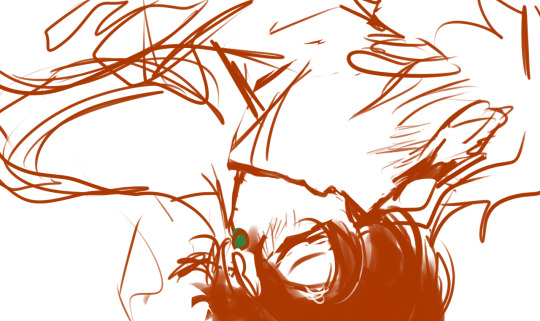

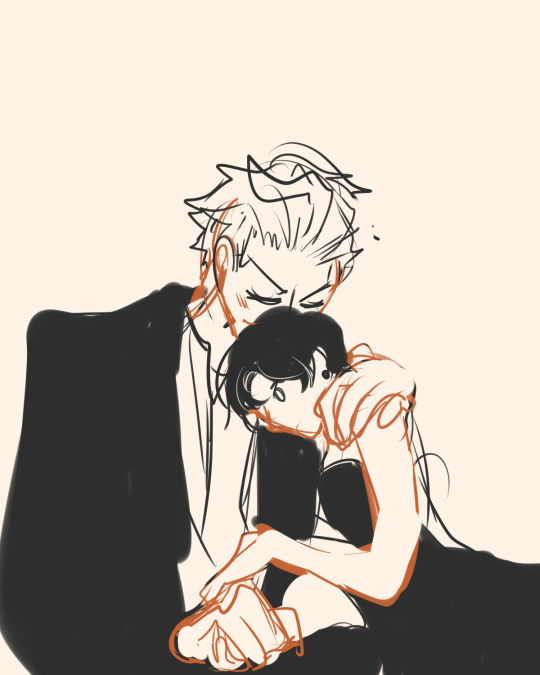

#i may be lazy to render it fully but i also feel that my sketches deliver the sense of movement better

Text

and some extra unused stuff while they are in affectionate mood

#the headlap kiss is just a scene on let's talk chu episode 2 that i really like; yuu was offering a massage & massaging his temples with her#thumbs; saying you really should release pressure from this area#i may be lazy to render it fully but i also feel that my sketches deliver the sense of movement better#(and avoiding to make any sense of the anatomy i am confused about)#(like which is going where)#and so because of all the cluster of lines; ur mind will make its own mind which line would make it look right#FUK I DIDN'T EVEN REALIZE I POST THIS ALREADY FHSDH I WAS STILL TRYING TO FIGURE OUT WHAT TO WRITE ON TAGS#twisted wonderland#twst#sebek zigvolt#twst yuu#twst mc#fanart#damn they are finally kissing and they meant it#this makes my chest all hot and bothered#suggestive

1K notes

·

View notes

Link

What most struck me about this production of Harold Pinter’s Betrayal, is how much it reminded me of another star-powered Pinter production that grazed Broadway in 2015–Old Times. The staging and direction of both productions were frigid, spare, with Lazy Susan-style rotating floor pieces on which the actors stood or sat or lounged, tensely, always poised and statuesque, often to great visual effect—three attractive actors each, as well-dressed and brooding as if they were models on an editorial fashion shoot.

What I remember most about the 2015 Pinter production is not the specifics of the content of the show itself (though I recall generally enjoying it), but this aesthetic, linked to the theme, of course—circuity and the particular trap of time—but so prominent that it overwrote the rest; my remembrance was so marked by the poses, the lights, the tone, and the distances between the actors onstage.

Similarly, when the lights come up on the current Betrayal, directed by Jamie Lloyd, the three characters of the play’s love triangle are stiffly posed together. One may think of chess pieces set on a board, and such a likeness is fitting—Pinter’s plays are ones of deception, manipulation, and calculated maneuvers. The set feels chilly, impersonal, bare. Slate-like panels frame the space, creating the sensation of things being hemmed in. The lighting, too, is aggressively icy, like the fluorescents in an office.

Jerry (Charlie Cox) and Emma (Zawe Ashton) sit side by side, talking in folding chairs as Robert (Tom Hiddleston) lurks in the background, removed, drink in hand. Emma and Jerry, it’s quickly revealed, have previously had an affair, though it’s over now, and Emma and Robert’s marriage has come to an end. They talk about their jobs, their families, and sprinkled in are a few references to things from their past that we’ll find out more about later: a trip to Italy, a playful moment with Emma’s daughter, lunchtime liaisons in a shared flat. It’s all on the table (atop a Venetian tablecloth, one could say, as such a fabric is referenced more than once) from the start, so the discovery lies not in the act itself but in the evolution of it, the resolve of it, the talk of and around it, which, more than the infidelity itself, encompasses the truest representation of betrayal.

In one exquisitely done scene, by far the best of the production, the back wall of the stage comes forward, clipping the open area from a yawn to a short breath of space, where Robert and Emma sit together while on vacation in Italy. The light has a yellow tint, and though there is no excess furniture (the same two chairs from the beginning appear again), and the tabula-rasa-style set is as unyieldingly clinical and anonymous as before, Robert and Emma move with an ease that implies familiarity, even when it’s invisible to our eyes, and the warmer lighting and smaller space draws us into the intimacy. Robert, having discovered that Jerry has sent Emma a letter, double-talks his way around asking her whether she’s sleeping with his best friend.

Hiddleston, temporarily hanging up his cape and horns from his role as the beloved mischief-maker of the Marvel Cinematic Universe to make his Broadway debut, is devastatingly matter of fact in his demeanor, his Robert steadily circling closer and closer to confirming the thing he already knows to be true as the conversation goes on. He nudges Emma, trying to gauge her reaction, but the exchange feels more masochistic on his part, a long, slow act of self-harm that Hiddleston allows Robert sink into with depressing resignation. Ashton, too, delivers her best in the scene, her face, elsewhere deceptively easy and bright, gradually crumbling and contorting as the conversation goes on. It’s like watching a home fall apart, in real time.

All the while, Jerry slumps against a wall in the dark, off to the side. Later, Robert sits directly next to Jerry as the latter meets with Emma for another indiscretion. Robert knows about the affair, and though the character is physically present onstage, he is silent, not actually present in the setting or the action of the scene. Still, he’s intrusive, like a spectre, a grim Dickensian Ghost of Marriage Present. It’s an artful choice on Lloyd’s part, which directs attention to the importance of proximities in the production, allowing each scene to maintain the tension of the trio and continue to hint at the consequences of a transgression that keeps happening.

The production in many ways literalizes the unpacking of the relationship that the text performs. In the haunting presence of the characters—whoever the third wheel happens to be in any given scene—is well done, but at other times the production just tips over the line into over kneading its themes. It eases us into the past, opens up so that we learn the characters personally, firsthand, as we witness them backwards in time. The problem is that whereas we’re meant to begin at the end with just a sketch of the situation and then gradually swallow the full context, missing in the early scenes is the sense that that same context—that history of the characters—is fully accessible to the production itself, even if it’s not yet accessible to us as we’re starting out on this backwards journey.

Part of the issue comes back to the audaciously stripped-down aesthetic and direction, which untether the play from time or setting (though both are clearly referenced—just not seen). This places the onus on the actors to recreate what we’re missing through the meat of their performances. Hiddleston’s Robert fits well into the cool distance that the play creates, occasionally showing his bite, and Cox’s Jerry (also known for his jaunts in the world of Marvel—albeit the grittier, Netflix-owned parts, in the criminal underground of Hell’s Kitchen in Daredevil) has an easy good-guy charm. Cox really digs his feet into the play’s comic moments, surprisingly, filling the space with jokes, and he works well opposite Hiddleston in their exchanges, but he sometimes goes a bit too big, hitting and holding the comic beats to a hammy fermata. But it’s Ashton who’s least served by the production’s combination of style and space; her Emma is remarkably aloof and remote, and the production only emphasizes her character’s emotional distance, so that her underlying feelings—a cocktail of wishfulness and sorrow and anger, one imagines—are so masked that they make the rendering feel undeveloped at times. Unfortunately, she and Cox also lack chemistry, and despite Lloyd’s attempts to spark electricity in the spaces between them—scenes where they touch, or, more often, don’t touch—it often feels like dead air.

But ultimately these are small qualms, minute, inconsistent injuries, in the grand sense of the thing—the thing being a production that succeeds in matching the thoughtfulness, in attention and execution, of Pinter’s text. In art there are incongruities that blunder or bore, but in this Betrayal, for example, the distinct takes on the characters, though they don’t always mesh, are nonetheless engaging, creating their own interesting kind of dissonance among them, even in times when one could imagine them as figures in each their own separate plays, of different tones and temperaments. More often than not, the production delivers what one would hope to receive on a night out to see a talented cast of actors in a well-known play by one of theater’s talented, oft-celebrated playwrights. Somehow, it manages to make betrayal stylish and simple and complex and familiar and detached and funny and tragic. It makes betrayal a pleasure to behold.

19 notes

·

View notes