#if I hadn’t a personal rule about trying to answer the inbox in order received I would’ve sketched this immediately

Note

More of a meme than anything, but can you imagine pre-reincarnation Tanya letting an employee borrow her phone and them just seeing Hatsune Miku plastered everywhere

miku fan salaryman is so incredibly important to me

pov: ur begging on ur knees to keep ur job and u happen to look up and the guy firing u has miku plastered all over his computer.

question: do u try to flatter him over his good taste in anime girls if the appeals to his morals dont work

#ask#tanjaded#not a daily post#bonus doodle#youjo senki#the saga of tanya the evil#salaryman#file this one under “asks that made me lose it”#got a weird look from my dad when i started laughing out of no where. sorry dad#if I hadn’t a personal rule about trying to answer the inbox in order received I would’ve sketched this immediately

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

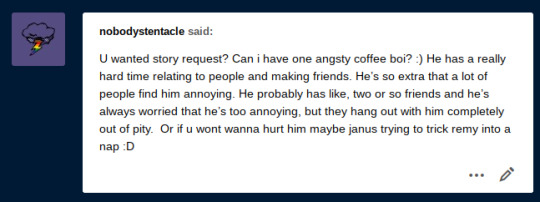

@nobodystentacle more Remy angst?!?!? You have a one track mind my friend. I can’t promise it will be any good, but I try. Sorry, this took slightly longer than I expected!

Note: this can be read as platonic or romantic, I don’t care which.

Go under the cut for story! Or, you can read it here on ao3!

---------------

“Remy darling, I love coffee as much as the next person, but don’t you think seven cups in a single morning is a bit extreme?” Janus asked as he watched Remy pour himself another cup of pure black coffee in the kitchen.

“Nah babes,” Remy said, laughing nervously, filling his mug to it’s limit. “I don’t think there’s such a thing as too much coffee, besides, I love the rush it gives me.”

Logan cleared his throat. “Actually, there is definitely such thing as too much coffee. If you-” Remy shushed him, not wanting to hear whatever scientific thing Logan was about to start quoting.

“I’m fine, I just like my coffee.” He walked out of the room, avoiding more questions. The moment he wasn’t visible, Remy yawned, his body begging for sleep. But Remy knew sleep wasn’t a good idea, he couldn’t deal with any of the nightmares he’d been dealing with. Remy physically cringed at the thought of those nightmares. He hadn’t told anyone about them because he wasn’t sure how to properly explain them without sounding crazy, and he didn’t want to feel like a burden to his friends. They all had their own lives and problems, they didn’t need Remy’s problems on top of all that.

Remy decided that he was going to do something active, something that he couldn’t fall asleep doing. He poured his coffee in a travel container and headed out the front door for a long walk.

~

Janus waited until he heard the door close, making sure that Remy was gone.

“I think coffee boi out there has a sleep problem,” Janus said, turning to Logan.

“Why do you say that?” Logan asked, looking up from his book.

“Look at him. He loves coffee, sure. But recently he’s been drinking more coffee in the span of a few hours that I’ve seen him drink in a couple of days normally. He’s totally out of it, he isn’t as quick on his feet as he usually is, and I’m 98% sure I saw some pretty dark bags under his eyes when he took off his sunglasses. He’s sleep deprived, and he’s trying to make up for it with coffee.”

Logan nodded. “Remy is a very vocal person, he’s not afraid to speak his mind on almost any subject. I would assume he’d say something if he had a problem, especially if the problem was important like a lack of sleep.” Logan continued to read his book, leaving Janus severely dissatisfied.

“I’m going to hide the coffee,” Janus said, getting out of his seat and headed to the kitchen.

“Why would you hide the coffee? People drink that you know,” Logan said, sighing and setting down his book.

“I believe that Remy is using it to stay awake. If he freaks out because the coffee is gone, that might tell us something.”

“Or he could just be freaking out because the coffee, his favorite drink, is gone simply because you don’t want to ask him directly if he’s been sleeping okay. Just talk to him, don’t make him suffer.”

“Fine, but if I talk to him and he doesn’t give me a clear answer, I’m hiding the coffee.”

Virgil walked into the kitchen at that exact moment, turning to Janus. “I have no clue what you’re talking about, but if you’re hiding the coffee, I’ll use your own technique and shove you down a flight of stairs.”

~

Remy finished his coffee way to quickly, so he decided to head back home to get more coffee. He jogged back to the house and opened the front door, headed straight to the kitchen.

But the kitchen entry was blocked by Janus. “Hello Remy darling. I think we need to talk.”

Remy rolled his eyes under his sunglasses. “Can we talk after I get my coffee? I’m all out.” He shook his travel mug to prove that it was empty of coffee.

“I think it’s best that you get coffee after we talk,” Janus said, pulling Remy into the living room and forcing him to sit on the couch.

“What is going on?” Remy said. “I feel like I’m about to get interrogated.”

“I’m not going to beat around the bush, I’ve been told that the best way to get an answer out of you is to just say what I’m thinking. Have you been losing sleep for any reason? How is your sleep pattern?” Janus stared at Remy, waiting for a response. Remy squirmed in his seat, visibly uncomfortable.

“If I answer honestly, can I get more coffee?” He asked.

“Depends. Now answer the question.”

“I’ve been sleeping just fine. I don’t know why you’re so worried.”

Janus sighed. “You do realize that you’re talking to the best liar in this house. I’m literally the Lord of Lies. I can tell when you’re lying, so please, let’s just be honest with each other.”

Remy stared at the coffee mug in his hands.

“Take off your glasses,” Janus said suddenly.

“What?”

“Take off your glasses or I will take them off for you.” Janus reached over but Remy blocked his hand and took them off. He had planned on putting some makeup under his eyes to cover his bags, but had never gotten around to doing it, so Janus could now see the full dark circles right under Remy’s eyes.

“Why haven’t you been sleeping Remy. You’ve practically shouted from the rooftops that you love to sleep, so why are you suddenly not sleeping? Why all the coffee, why the endless cycle of activities to keep you awake? You’re either going to die of exhaustion or too much caffeine at this point, neither sound very pleasant.”

Remy sighed, realizing that he couldn’t stop hiding his problems from his friends. “I’ve been having this reoccurring dream, a nightmare actually. Something from my childhood that I must have repressed and then dragged back up to the conscious part of my mind. But either it’s made me not want to sleep, so I’ve been fighting it with everything I can think of. Coffee, energy drinks, things to keep my mind active. Anything I can think of. As long as I’m not sleeping, I can’t have the nightmare.”

Janus thought for a moment. “Maybe if I helped, I could use some techniques I learned with Virgil to help you go to sleep with your mind in a much calmer state, which would make it less likely for you to have this nightmare. Please, let me try to help. It’s better than dying.”

“Fine, you can try some of your things.”

Janus stood up, offering Remy his gloved hand. Remy raised an eyebrow.

“Right now?”

“Yes right now, you need sleep. I don’t know how many days you’ve gone without it, but I can tell you that it’s definitely too many.” Remy took Janus’ hand and the two of them walked up the stairs and into Remy’s room.

“In bed, I’ll get the stuff.”

“What stuff?” Remy asked.

“A white noise machine, and some calming tea, which does not have caffeine. I also found that Virgil slept better when there was someone else in bed with him, but we can skip that one if you want.”

Remy thought for a moment. “We can try it, but I reserve the right to kick you out of bed at any point in the night.”

“Sounds good darling,” Janus said, leaving the room to go the the white noise machine and tea. He brought them back, handing Remy the tea and ordering him to drink the entire mug while he set up the white noise machine.

Once everything was set up and Janus had checked to see if Remy had finished the tea, Janus crawled into the bed next to Remy.

“It will probably work better if I was basically cuddling you, but if you don’t want that, then we do it your way,” Janus said. Remy nodded, scooting closer to Janus and letting Janus wrap his arms around the other person, holding him.

Remy wanted to complain about something, anything. But he felt so at peace and calm, that his brain started to shut down and he began to drift to sleep. In almost no time, he was was in a deep sleep.

That night he slept perfectly, without a single nightmare. He started using the white noise machine every night and the calming tea regularly. If he had problems sleeping, he’d ask Janus to come and help him fall asleep, and every time Janus was more than happy to help.

“I just want you to take care of yourself,” Janus would say every time he would crawl in bed next to a sleepy Remy. Remy would mumble something that Janus usually couldn’t make out, because Remy was already mostly asleep in Janus’ arms.

Janus allowed Remy to continue drinking coffee, as long as it was in moderation. Remy would complain a bit whenever Janus asked him how many cups he had drinken that morning, but he tried to be more mindful of his caffeine intake.

Soon, Remy didn’t worry about nightmares or lack of sleep. His sleeping pattern had returned to normal, all thanks to Janus.

---------

I hope you enjoyed this fic, it was so much fun to write!

If anyone wants to send me a writing prompt, I’m always grateful to receive more! Please read my rules (found here) and then leave the prompt in my inbox! If you stay off anon, I will be sure to contact you with details and things. Though if you leave it as an anon, that’s fine too!

#coffee addition#Remy Sanders#TS Remy#remy sleep#TS Janus#Janus Sander#Sanders Sides#sanders sides fanfiction#Sanders Sides fanfic#writing prompt#feel free to send in writing prompts#my writing#who let me become a writer#who let me become a writer?#nobodystentacle#ask#thanks for the ask!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arplis - News: When Medical Debt Collectors Decide Who Gets Arrested

This story was originally published by ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for ProPublica’s Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox as soon as they are published.

On the last Tuesday of July, Tres Biggs stepped into the courthouse in Coffeyville, Kansas, for medical debt collection day, a monthly ritual in this quiet city of 9,000, just over the Oklahoma border. He was one of 90 people who had been summoned, sued by the local hospital, or doctors, or an ambulance service over unpaid bills. Some wore eye patches and bandages; others limped to their seats by the wood-paneled walls. Biggs, who is 41, had to take a day off from work to be there. He knew from experience that if he didn’t show up, he could be put in jail.

Before the morning’s hearing, he listened as defendants traded stories. One woman recalled how, at four months pregnant, she had reported a money order scam to her local sheriff’s office only to discover that she had a warrant; she was arrested on the spot. A radiologist had sued her over a $230 bill, and she’d missed one hearing too many. Another woman said she watched, a decade ago, as a deputy came to the door for her diabetic aunt and took her to jail in her final years of life. Now here she was, dealing with her own debt, trying to head off the same fate.

Biggs, who is tall and broad-shouldered, with sun-scorched skin and bright hazel eyes, looked up as defendants talked, but he was embarrassed to say much. His court dates had begun after his son developed leukemia, and they’d picked up when his wife started having seizures. He, too, had been arrested because of medical debt. It had happened more than once.

Judge David Casement entered the courtroom, a black robe swaying over his cowboy boots and silversmithed belt buckle. He is a cattle rancher who was appointed a magistrate judge, though he’d never taken a course in law. Judges don’t need a law degree in Kansas, or many other states, to preside over cases like these. Casement asked the defendants to take an oath and confirmed that the newcomers confessed to their debt. A key purpose of the hearing, though, was for patients to face debt collectors. “They want to talk to you about trying to set up a payment plan, and after you talk with them, you are free to go,” he told the debtors. Then, he left the room.

The first collector of the day was also the most notorious: Michael Hassenplug, a private attorney representing doctors and ambulance services. Every three months, Hassenplug called the same nonpaying defendants to court to list what they earned and what they owned — to testify, quite often, to their poverty. It gave him a sense of his options: to set up a payment plan, to garnish wages or bank accounts, to put a lien on a property. It was called a “debtor’s exam.”

If a debtor missed an exam, the judge typically issued a citation of contempt, a charge for disobeying an order of the court, which in this case was to appear. If the debtor missed a hearing on contempt, Hassenplug would ask the judge for a bench warrant. As long as the defendant had been properly served, the judge’s answer was always yes. In practice, this system has made Hassenplug and other collectors the real arbiters of who gets arrested and who is shown mercy. If debtors can post bail, the judge almost always applies the money to the debt. Hassenplug, like any collector working on commission, gets a cut of the cash he brings in.

Crystal Dyke with her husband and two kids outside their home in Leroy, Kansas. She was arrested when she was pregnant because she missed hearings involving a $230 radiologist bill.

Across the country, thousands of people are jailed each year for failing to appear in court for unpaid bills, in arrangements set up much like this one. The practice spread in the wake of the recession as collectors found judges willing to use their broad powers of contempt to wield the threat of arrest. Judges have issued warrants for people who owe money to landlords and payday lenders, who never paid off furniture, or day care fees, or federal student loans. Some debtors who have been arrested owed as little as $28.

More than half of the debt in collections stems from medical care, which, unlike most other debt, is often taken on without a choice or an understanding of the costs. Since the Affordable Care Act of 2010, prices for medical services have ballooned; insurers have nearly tripled deductibles — the amount a person pays before their coverage kicks in — and raised premiums and copays, as well. As a result, tens of millions of people without adequate coverage are expected to pay larger portions of their rising bills.

The sickest patients are often the most indebted, and they’re not exempt from arrest. In Indiana, a cancer patient was hauled away from home in her pajamas in front of her three children; too weak to climb the stairs to the women’s area of the jail, she spent the night in a men’s mental health unit where an inmate smeared feces on the wall. In Utah, a man who had ignored orders to appear over an unpaid ambulance bill told friends he would rather die than go to jail; the day he was arrested, he snuck poison into the cell and ended his life.

In jurisdictions with lax laws and willing judges, jail is the logical endpoint of a system that has automated the steps from high bills to debt to court, and that has given collectors power that is often unchecked. I spent several weeks this summer in Coffeyville, reviewing court files, talking to dozens of patients and interviewing those who had sued them. Though the district does not track how many of these cases end in arrest, I found more than 30 warrants issued against medical debt defendants. At least 11 people were jailed in the past year alone.

With hardly any oversight, even by the presiding judge, collection attorneys have turned this courtroom into a government-sanctioned shakedown of the uninsured and underinsured, where the leverage is the debtors’ liberty.

The courtroom where Hassenplug and other collectors administer “debtor’s exams.”

Seated at the front of the courtroom, Hassenplug zipped open his leather binder and uncapped his fountain pen. He is stout, with a pinkish nose and a helmet of salt and pepper hair. His opening case this Tuesday involved 28-year-old Kenneth Maggard, who owed more than $2,000, including interest and court fees, for a 40-mile ambulance ride last year. Maggard had downed most of a bottle of Purple Power Industrial Strength Cleaner, along with some 3M Super Duty Rubbing Compound, “to end it all.” His sister had called 911.

Maggard took his seat. He had cropped red hair, pouchy cheeks and mud-caked sneakers. “The welfare patients are the most demanding, difficult patients on God’s earth,” Hassenplug told me, with Maggard listening, before launching into his interrogation: Are you working? No. Are you on disability? He was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type, and anxiety. Do you have a car? No. Anyone owe you money you can collect? I wish.

They had been here before, and they both knew Maggard’s disability checks were protected from collections. Hassenplug set down his pen. “Between you and me,” he asked, “you’re never going to pay this bill, are you?”

“No, never,” Maggard said. “If I had the money, I’d pay it.”

Hassenplug replied, “Well, this will end when one of us dies.”

Though debt collection filings are soaring in parts of America, Hassenplug speaks with pride about how he discovered their full potential in Coffeyville long before. A transplant from Kansas City, he was a self-dubbed “four-star fuck-up” who worked his way through law school. He moved to Coffeyville to practice in 1980 and soon earned a reputation as a hard ass. He saw that his firm, Becker, Hildreth, Eastman & Gossard, hadn’t capitalized on its collections cases. The lawyers didn’t demand sufficient payments, and they rarely followed up on litigation, he said. Where other attorneys saw petty work, Hassenplug saw opportunity.

Kenneth Maggard at his home. “Blaze,” painted below, is his son’s name.

Hassenplug started collecting for doctors, dentists and veterinarians, but also banks and lumber yards and cities. He recognized that medical providers weren’t being compensated for their services, and he was maddened by a “welfare mentality,” as he called it, that allowed patients to dodge bills. “Their attitude a lot of times is, ‘I’m a single mom and … I’m disabled and,’ and the ‘and’ means ‘the rules don’t apply to me.’ I think the rules apply to everybody,” he told me.

He logged his cases in a computer to track them. First with the firm and later in his own practice, he took debtors to court, and he won nearly every time; in about 90% of cases nationally, collectors automatically win when defendants don’t appear or contest the case. Hassenplug didn’t need to accept $10 monthly payments; he could ask for more, or, in some cases, even garnish a quarter of a debtor’s wages. His fee was, and often still is, one-third of what he collects. He asked the court to summon defendants, over and over again. It was the judge’s contempt authority that backed him, he said. “It’s the only way you can get them into court.”

The power of contempt was originally the power of kings. Under early English rule, monarchs were considered vicars of God, and disobeying them was equivalent to committing a sin. Over time, that contempt authority spread to English courts, and ultimately to American courts, which use it to encourage compliance with the judicial system. There is no law requiring that a court use civil contempt when an order isn’t followed, but judges in the U.S. can choose to, whether it’s to force a defendant to pay child support, for example, or show up at a hearing. A person jailed for defying a court order is generally released when they comply.

When Casement took the bench in 1987, after passing a self-study exam, he didn’t know much legalese — he had never been in a courtroom. But attorneys taught him early on that the power of contempt was available to him to punish people who ignored his orders. At first, Casement could see himself in the defendants. “I was a much more pro-debtor aligned judge, much more sympathetic, much less inclined to do anything that I thought would burden them,” he told me. “And over the years, I’ve gradually moved to the other side of the fulcrum. I still consider myself very much in the middle, and I don’t know if I am or not.”

Once a bustling industrial hub, Coffeyville has a poverty rate that is double the national average, and its county ranks among the least healthy in Kansas. Its red-bricked downtown is lined with empty storefronts — former department stores, restaurants and shops. Its signature hotel is now used for low-income housing. “The two growth industries in Coffeyville,” Hassenplug likes to say, “are health care and funerals.”

A shuttered motel in Coffeyville. The town, once a bustling industrial hub, now has a poverty rate more than double the national average.

Coffeyville Regional Medical Center is the only hospital within a 40-mile radius, and it reported $1.5 million in uncollectible patient debt in 2017. A nonprofit run in a city-owned building, the hospital accounts for the vast majority of medical debt lawsuits in the county — about 2,000 in the past five years. It also accounts for the majority of related warrants. Account Recovery Specialists Inc. handles its collections, and it does so for hospitals in most Kansas counties. Though the hospitals can direct ARSI and its contracted attorneys to tell judges not to issue warrants, hardly any have. The Coffeyville hospital’s attorney, Doug Bell, said that its only motivation is to continue to serve the area, and that Kansas’ decision to not expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act has had a “dramatic effect on the economic liability of small rural hospitals.”

Three nearby hospitals in this rural region have closed in the past several years, meaning ambulances make more trips. A half-hour from Coffeyville, Independence runs its ambulance service at about a $300,000 annual loss. Its bills were at the root of four arrests this year alone. Derek Dustman, who is 36 and works odd jobs, had been driving a four-wheeler when he was hit by a car and rushed to the hospital. Though he was sued for not paying his $818 ambulance bill, he didn’t have a license to drive to the courthouse. This spring, he spent two nights in jail. “I never in a million years thought that this would end with jail time,” he told me.

For years, Hassenplug has requested that the judge issue warrants on the ambulance service’s behalf. When I asked Lacey Lies, the city’s director of finance, if she ever considered telling him not to resort to bench warrants, she was puzzled. “You’re saying an attorney with no teeth?”

A city ambulance in Independence, Kansas. Hassenplug represents the service against its debtors.

The first time Tres Biggs was arrested, in 2008, he was dove hunting in a grove outside Coffeyville. It had been just a year since his 6-year-old son Lane was diagnosed with leukemia, and Biggs watched him breathe in the fresh air, seated on a haybale under an orange sky. When a game warden came through to check hunting permits, Biggs’ friends scattered and hid. He wasn’t the running type, and he took Lane by the hand. The warden ran Biggs’ license. There was a warrant out for his arrest. Biggs asked a friend to take Lane home and crouched into the warden’s truck, scouring his memory for some misstep.

The last few years had been a blur. His wife, Heather, had quit her job as a babysitter to care for their son. Then, she got sick. Some days, she passed out or felt so dizzy she couldn’t leave her bed. Her doctors didn’t know if the attacks were linked to her heart condition, in which blood flowed backward through a valve. To provide for his wife, son and two other kids, Biggs worked two jobs, at a lumber yard and on construction sites. He didn’t know when he would have had time to commit a crime. He’d never been to jail. As he stared out the window at the rolling hills, his face began to sweat. He felt his skin tighten around him and wondered if he would be sick.

The warrant, he learned at the jailhouse, was for failure to appear in court for an unpaid hospital bill. Coffeyville Regional Medical Center had sued him in 2006 for $2,146, after one of Heather’s emergency visits; neither of his jobs offered health insurance. In the shuffle of 70-hour workweeks and Lane’s chemotherapy, he had missed two consecutive court dates. He was fingerprinted, photographed, made to strip and told to brace himself for a tub of delousing liquid. His bail was set at $500 cash; he had about $50 to his name.

Coffeyville Regional Medical Center is the only hospital within a 40-mile radius.

His friend bailed him out the next morning, but at the bond hearing, the judge granted the $500, minus court fees, to the hospital. Biggs compensated his friend with a motorboat that a client had given him in exchange for a hunting dog. But it wasn’t long before the family received a new summons. In 2009, a radiologist represented by Hassenplug sued them for $380.

Some court hearings fell on days when Lane had treatment, at a hospital in Tulsa, an hour south. Heather refused to postpone his care. Lane’s condition was improving — in a year, he would be cancer-free — and his dirty blond hair was sprouting again. Her health, though, had taken a turn. She began having weekly seizures, waking up on the floor, confused about where their Christmas tree had gone or why a red Catahoula puppy was skidding around their ranch house. Her doctors concluded she had Lyme disease, which was affecting her nervous system and wiping her short-term memory. Each time she woke up, she repeated: “Don’t take me to the hospital.”

Biggs was still on the hook for the bill that had landed him in jail; bail had covered only part of it, and the rest was growing with 12% annual interest. The hospital had garnished his wages, and the radiologist had garnished his bank account, seizing contributions that his family had raised for Lane’s care. Living on $25,000 a year, Biggs couldn’t afford to buy insurance. His family was on food stamps but didn’t qualify for Medicaid, a federal insurance program for people in poverty. Other states were about to expand it to cover the working poor, but not Kansas, which limited it, for families of his size, to those who earned under $12,000. Like millions of others across America, he and Heather fell into a coverage gap.

By 2012, the Biggs family had accrued more than $70,000 in medical debt, which it owed to Coffeyville Regional Medical Center and other hospitals, pediatricians and neurologists. Some forgave it; others set up lenient payment plans. Coffeyville’s was the only hospital that sued. The doctors who took them to court were represented by Hassenplug.

Tres Biggs with his wife, Heather, and son, Lane, at their home.

Biggs began to panic around police, haunted by the fear that at any moment, he might be locked up. That spring, outside the Woodshed gas station, he spotted a sheriff’s deputy who was also an old friend. To shake off his dread, he asked the friend to run his license. The deputy found another warrant, signed by Casement, involving the $380 radiologist’s bill. “You’re not really going to take me in, right?” Biggs remembers asking. The deputy said he had no choice. Bail, as usual, was set at $500.

The family filed for bankruptcy, a short-term fix that erased their debt but burdened them with legal fees. They lost their home and started renting. Biggs ultimately got a job that offered insurance, as a rancher, covered by Blue Cross Blue Shield. But it required Biggs to pay the first $5,000 before it covered medical expenses. When chest pain hit him as he worked cattle in the heat, and he began vomiting, the only nearby hospital was Coffeyville’s. In 2017, the hospital sued again. It was the family’s sixth lawsuit for medical debt.

Sitting in Casement’s courtroom this July, Biggs calculated that he was losing about $120 by taking time off from work to attend this hearing. “I haven’t received a bill,” he told me, slouched over his turquoise shorts. “The only thing I received was this summons.” Around noon, he finally sat down with an ARSI representative, who explained that the underlying bill had been garnished from his wages, but he still owed $328 in interest and court fees. He had another couple thousand dollars in collections for separate bills he hadn’t paid, for which he hadn’t yet been sued. He said the most he could afford to pay, every two weeks, was $12.50.

Before the end of the Tuesday docket, Casement returned to the courtroom to read off the names of the hospital’s defendants. Five had failed to show up for contempt citations, to give their reasons for missing their debtor’s exams. Casement saw that two of the no-shows hadn’t been properly notified of the hearing, so attorneys would need to try to reach them again. The judge read the names of the other three defendants and told the hospital’s collections lawyer, “That would be a bench warrant if you want it.”

The following morning, I was reading court files in the clerks’ office when Christa Strickland arrived at 10:20 in flip-flops and black leggings, her caramel hair wrapped in a bun atop her head. She ran her finger down a docket on the bulletin board and asked why her case wasn’t listed. When the clerk pulled up her file, she told Strickland that her contempt hearing had been on Tuesday and she was one day late. “You need to call the law office of Amber Brehm,” the clerk insisted, referring to ARSI’s contracted lawyer, who represents the hospital. She handed over the phone number.

Strickland sat on a hard bench and took out her cellphone. She had saved the hearing in the wrong day on her calendar, but she had taken the day off from work and wanted to clear up the misunderstanding. “I had a court date,” she said when a man answered at the law office. “I thought it was today but apparently it was yesterday. I’m just needing to see if I can set something up?”

“By not appearing at that, the court would be in the process of issuing a bench warrant,” he said.

“What does that mean?” Strickland asked, shaking her head.

“You don’t know what a bench warrant means?” he asked. “That means you will be arrested and taken to jail and ordered to post bond.”

“Oh my God.” Strickland squeezed her eyes shut, wetness smudging her mascara. She poked at her cheek with her index finger. Her father was a preacher. She’d never been in trouble with the law. She had made a mistake, she tried to explain. She wanted to make an arrangement to pay.

The Coffeyville courthouse.

The man on the phone told her that it might take a couple weeks before the court processed her warrant paperwork, which the law office had not yet submitted. Once the judge issued the warrant, she could turn herself in. Strickland wanted to scream, I’ll pay the bill, don’t make me go to jail! but she didn’t have the money. Instead, she looked at the ceiling and asked: “Turn myself into the court? The police station?”

“The Sheriff’s Department,” he responded.

“They’re here in the same building,” she said. “I won’t leave here until I get this figured out. Thank you!”

She hung up. Prick, she muttered to herself. You’re going to talk to me like I’m a freaking idiot? That’s not okay. Educate me. The court has to process it? Her mind kept moving in circles. She herself worked in debt collection, for an auto title lending company. She understood that everyone was doing their job. Still, she couldn’t grasp how this bill had gotten this far.

Before she had taken this position, during her second pregnancy, her right breast had developed a chronic infection. In 2008, she was uninsured, needed surgery to remove the swollen abscess and ran up a $2,514 bill. More than a decade later, she was still chipping away at a balance that, because of interest and court fees, had more than doubled to $5,736. She had fallen behind on her monthly payment plan and now worried that her booking photo would be on Mugshot Monday, a Facebook album run by the Police Department. She imagined what she would tell her boss: I went to jail … because I missed a court date … for medical bills. It sounded absurd.

She spotted a sheriff’s deputy in a bulletproof vest with a name tag that said Bishop and a pistol on his hip. “Hey!” she called out, explaining her phone call and how the man said something about a warrant and turning herself in. Bishop radioed into dispatch and smiled with an update: “There’s no warrant in the system yet,” he told her.

“Yet!” Strickland replied, deflating his look of reassurance. “That’s what I’m worrying about.”

“You better give Amber a call back,” Bishop said.

When I asked ARSI about how attorneys decide to request warrants, Joshua Shea, who is general counsel, told me that they don’t. The judge can choose to issue one if court orders are not followed, he said. But Casement said the opposite, telling me that he gave the choice to the attorneys. “I’m not ordering a bench warrant. My decision is to give them that option,” Casement told me. “Whether they exercise it is up to them, but they have my blessing if that’s what they want to do.”

Shea sent me an eight-page email to make clear, in large part, that ARSI, as a collection agency, has no involvement in the courts, and that Brehm is a lawyer whom the agency contractually employs and who represents the hospital directly. Her email address, though, has an ARSI domain, and her resume lists her as ARSI’s director of legal. Brehm said that court hearings aren’t the only option for debtors, who can call her instead and answer questions under oath. Shea said nobody — not the hospital, ARSI, Brehm or the court — uses the threat of jail to “extract payment.”

Strickland reached Brehm after several days, and the attorney agreed to a new hearing. On Aug. 13, when they met in court, Brehm sat at the front of the room.

“We’re giving you a second chance on that citation; just to try to take care of this without there having to be any sort of bench warrant,” the lawyer said. “I want to make sure that we’re all on the same page about the consequences of not coming into court when the order has been issued.”

Strickland nodded.

“Again, if you set a payment plan and keep it,” Brehm said, “we won’t have to worry about that.”

The jail in Independence, where many debtors in the county are booked.

In some courthouses, like Coffeyville’s, collection attorneys are not only invited to decide when warrants are issued, but they can also shape how law is applied. Recently, Hassenplug came to believe that debtors were only attending every other hearing in a scheme to avoid jail, and he raised his concern with the judge. He suggested that the judge could fix this by charging extra legal fees; Casement wrote a new policy explaining that anyone who missed two debtor’s exam hearings without a good reason would be ordered to pay an extra $50 to cover the plaintiff’s attorney fees. If they didn’t pay, they would be given a two-day jail sentence; for each additional hearing that they missed, they would be charged a higher attorney fee and get a longer sentence.

Most states don’t allow contempt charges to be used for nonpayment, and some, like Indiana and Florida, have concluded that it is unconstitutional. Michael Crowell, a retired law professor at the University of North Carolina and an expert in judicial authority, reviewed Casement’s policy. “You can’t lock people up for contempt for failing to pay unless you have gone to the trouble to determine that they really have the ability to pay,” he said. Casement told me he hadn’t made findings on ability to pay before ordering defendants to foot attorney’s fees, “but I know that’s something the court should consider,” he said. He also made plain why he wrote the policy: “Mr. Hassenplug and Brehm’s outfit have asked me to.” (Brehm denied she requested this.)

Judge David Casement in the courtroom. Casement, a cattle rancher, was appointed magistrate judge, though he’d never taken a course in law.

Casement has not done everything the debt collection lawyers have suggested. At first, he agreed to their requests to set bail at the amount of the debt, but he eventually settled on $500. “Most people can come up with $500,” he said. “It may not be their money, but they know someone who will pay.” He made sure no one was arrested unless they’d been reached by personal service or certified mail.

Kansas law allows courts to order debtors in “from time to time,” leaving discretion to judges. Casement limited the frequency of Hassenplug’s debtor’s exams to once every three months. He came to the decision by his own logic around what seemed like a reasonable burden for defendants, and it remains his personal policy today. The law also states that anyone found to be disabled and unable to pay can only be ordered to appear once a year. Without an attorney, debtors like Kenneth Maggard don’t know to assert this right.

Allowing bail money to count toward collections raises some of the most critical legal questions. Hassenplug told me that he thinks it’s great that cash bail is applied to the debt. “A lot of times, that’s the only time we get paid, is if they go to jail,” he said. Peter Holland, the former director of the Consumer Protection Clinic at the University of Maryland Law School, explained that this practice reveals that the jailing is not about contempt, but about collection. “Most judges will tell you, ‘I’m working for the rule of law, and if you don’t show up and you were summoned, there have to be consequences,’” he explained. “But the proof is in the pudding: If the judge is upholding the rule of law, he would give the bail money back to you when you appear in court. Instead, he is using his power to take money from you and hand it to the debt collector. It raises constitutional questions.”

Congress has not acted on advocates’ calls to amend the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act to prohibit collectors from requesting warrants. There are also no current efforts to bar nonprofit hospitals or medical providers that receive funds through Medicare or Medicaid from seeking warrants. Some states have reformed their laws, to make sure defendants are properly served or to prohibit wage garnishments for debt. But legal experts on collections say that more remains to be done, like taking jail out of the equation and instead requiring debtors to sign a financial affidavit or a promise to appear.

Michael Hassenplug’s office in Coffeyville.

Shea, from ARSI, said that using the legal process is time-consuming and costly — a last resort; arrests are “the least desirable stage for any case to reach for all involved.” Even after lawsuits are filed, they try to connect eligible debtors with the Coffeyville hospital to apply for financial assistance, he said. Last year, the hospital wrote off $1.7 million in charity care, said Bell, the hospital lawyer. “That is evidence of a hospital that cares.”

Casement said he did not consider the legality of his policies a problem. He placed some blame on the health care system. “What we have isn’t working,” he said. “As a lifelong Republican, I would probably be hung, but I think we need health care for everybody with some limits on what it’s going to cost us.”

The way he saw it, he had wide latitude to enforce compliance with a court orders, though he acknowledged that creditors used bail money to their advantage. “I don’t know whether the Legislature intended it to be used that way or not,” he told me. “I have not had enough pushback from the defendants’ side to give me the impression that I’m really abusing this badly.”

A city ambulance in Independence, Kansas. Hassenplug represents the service against its debtors.

Before I left Coffeyville, I sat down with Hassenplug in the low-ceilinged courtroom. I asked him whether he thought that the system in Coffeyville was effectively imprisonment for debt, in a country that has outlawed debtors’ prisons. “The only thing they’re in jail for is not appearing,” he replied. “I do my job, I follow the law. You just have to show up in court.”

Debt collection is an $11 billion industry, involving nearly 8,000 firms across the country. Medical debt makes up almost half of what’s collected each year. Today, millions of debt collection suits are overwhelming state courts. The practice is considered a “race of the diligent,” where every creditor is rushing to the courthouse, hustling to get the first judgment, in order to be the first to collect on a debtor’s assets. In Hassenplug’s view, though, this work is not the rich taking from the poor. He laughed at how locals spread rumors, saying that he seized wheelchairs or Christmas trees. Once, he confessed, he took a man’s Rolex, only to find out it was a fake. Some months, he said, even his law office could not make ends meet.

After a couple of hours, a clerk poked her head into the courtroom and told us it was time to leave. Hassenplug and I began to walk out, and on the terrazzo steps, he asked if I wanted to see his buildings. He owned five of them on a shuttered stretch of town. He wondered out loud if he was making a mistake by inviting me, but he was pleased when I accepted. “There ain’t any place on earth quieter than downtown Coffeyville,” he said, leading me into the silent streets.

He walked me through the alleys under a cloudless sky, and when he arrived at one of his buildings, he tapped a code to his garage. The door lifted, and inside, five perfectly maintained motorcycles, Yamahas and Suzukis, were propped in a line. To their left, nine pristine, candy-colored cars were arranged – a Camaro SS with orange stripes, a Pontiac Trans Am, a vintage Silverado pickup with velvet seats. He toured me around the show cars, peering into their windows, and mused about what his hard work had gotten him.

Correction, Oct. 16, 2019: This story originally misstated the type of cancer Tres Biggs’ son, Lane, had. It was leukemia, not lymphoma.

#HealthCare #Corruption #CrimeAndJustice #CivilLiberties #Photoessays

Arplis - News

source https://arplis.com/blogs/news/when-medical-debt-collectors-decide-who-gets-arrested

0 notes

Text

Not Justice (6)

It’s here... the post-ketsu Big Fic Update... :D thank you @scarlet-blossoms!

Rating: M

Words: 5,500

Warnings: PTSD (panic attack, derealization, some unsanitary stuff), child kidnapping, Namie’s ego.

Not Justice

Chapter 6

Izaya refused to go back to Tokyo as long as Namie herself wasn't already there to wait for him. Namie had expected it, had her brain rushing ahead and her fingers on the keyboard of her laptop by the time he hung up on her, trying to buy the quickest plane ticket to Narita that she could find.

It didn't matter how expensive it was. She still had access to one of Izaya's bank accounts, and what was left on it largely paid for the fee.

She left the same evening with not even a note behind herself. The woman at the entrance of the hotel she was staying at looked at her with wide eyes when she handed over her keys—for good—and all Namie felt at the sight was a burning sort of satisfaction. "You'd look better with short hair," she told her, breaking another of the rules she had set for herself by the time she reached fifteen years old.

She didn't compliment people who weren't Seiji. Especially not women.

The text she sent to Kishitani Shingen from the airport was to the point. I quit, it said. Shingen tried to call her almost immediately, but Namie shuffled deeper inside the armchair of the first class resting lounge and turned off her phone entirely. The champagne she downed from the offered buffet was the best she had ever tasted.

She didn't retain much from the flight. She wasn't sick, and her ears didn't hurt like Seiji's had when they had traveled to America together almost two years ago. She grabbed a few fitful hours of sleep, her back aching despite the comfort of her seat and her dreams plagued by Izaya's voice and flashes of the city she was going to. The city she was returning to.

She didn't know if it felt like going home. She had never had a place to call home in the first place.

It took until her plane landed in Japan for her to realize that the weightlessness of her heart came from the fact that, for the first time in years, no one was after her. She wasn't in danger. Seiji was thousands of miles away, unaware of her departure, and the only thing waiting for her here was what she herself had brought. She had nothing to expect here but maybe answers to the void inside her—and already this gap was being bridged, already she could breathe like she hadn't in months. She was clean, and she was fed, and she had two suitcases with her full of belongings that she didn't have to hand over to anyone.

Her inbox was full when she turned on her phone once more. She deleted the Kishitanis' inquiries without reading them, opened Izaya's email to check what time his train would arrive in Narita—ten thirty—and finally, her thumb hovered over the single text she had received from Harima Mika.

There was a sense of finality in her when she opened it.

Good luck, it read. And, like an afterthought, Thank you.

Namie's jaw was tense, her throat dry and hot. She felt no anger, though, and no regret.

Namie took a seat at a café inside the station and resolved to spend the next two hours waiting in silence, hands resolutely not shaking around the porcelain cup that a waiter brought her, stomach too knotted to eat the breakfast she had ordered with it. Her toast cooled down within a few minutes, the grease from the butter growing less appealing as it did. She ate half of an apple and the tiny piece of chocolate that went with the coffee. She felt tired but restless, and the caffeine helped with that, making it almost impossible for her to close her eyes or quiet her own heartbeat.

She told Izaya where exactly she was waiting thirty minutes before his train was scheduled to arrive. She couldn't see the tracks from inside the station, but she was right outside of where he should come up once the time came. Seeing posters written in her own language and hearing it spoken around her in the café hadn't been surprising at first; now, though, she found herself lending an ear to the other customers' murmurs and glancing at the ads plastered over the walls of the station.

She thought she must simply be too tense at first. The closer she got to the time of Izaya's arrival and the harder her heart beat against her ribcage, the more she felt her own clothes tighten around her as if to suffocate her—her bra was digging into her sides, making it hard to breathe. She was considering sneaking a hand under her shirt to unclasp it when her eyes glanced over one more movie poster.

Hanejima Yuuhei, she thought. He was on it, looking no different than she remembered. Pretty but plain. Namie rubbed her forehead with tired fingers, a useless attempt at pushing away the headache she could feel coming; her eyes lowered to read the title of the movie, and her heart jumped in her chest before she could understand why.

There was a man standing next to the poster. He was too far away for her to see his features, and he was looking to his side anyway.

He had blond hair.

Her leg jerked under the table, making her empty cup and untouched plate rattle loudly. Namie barely remembered to drop a few bills onto it before she jumped out of her chair, dragging her suitcases behind her, walking toward the man with fury flowering inside her, tasting fire on her tongue.

There must be tens of thousands of men with blond hair in Tokyo and its vicinity. She knew that. And even as she got closer she couldn't see this one's face, and he was wearing very plain clothes too. But the build fit, and the atmosphere did too, and Izaya's train would be here in less than five minutes.

Heiwajima Shizuo barely managed to avoid the suitcase she threw at his legs. He turned his head in her direction right as she was reaching back, feet slipping on the floor as she tried to gain traction on it, and his side-step was done with a loud swear.

Namie's suitcase crashed into the wall, right under the Hanejima poster.

"What the fuck is wrong with you?" Heiwajima barked, veins turning dark in his face and hands flexing by his sides.

Namie was too tired to be afraid. "You are not going to ruin this for me," she hissed. "Get out."

"You just tried to break my leg—"

Nami stepped forward and grabbed him by the collar before he could finish, and he looked bewildered, an expression she had never seen on his face in the few glimpses she had had of him in person before. "Get out!" she yelled, her spit probably flying into his face, she was so close. "I don't care if you beat me up later, just get out, now."

"Who the fuck are you?" Heiwajima took hold of her hands and ripped them off of him—lifted her and pushed her away as if she weighed nothing at all. "Give me one reason why I shouldn't punch your face in!"

Namie's body was too tense on anger, red-hot and slimy inside her veins. She couldn't feel any more fear because she was already bursting with it. "It doesn't matter," she said. From the corner of her eyes, she saw a man in uniform approach them slowly. "Fuck. Heiwajima, you need to get out of here."

"Why should I?" he answered loudly. "Who are you?"

"Shit," Namie whispered, biting into her own lips. She had the taste of metal on her tongue when she ordered, "Tell that guy that everything's fine."

"You—"

"Please." She wasn't above begging. Not for this.

Ten-twenty-eight, the clock on the wall said.

Heiwajima looked at her—too long, too slow—and she thought she saw him physically reign in the violence visible in the line of his shoulders. He exhaled as though trying to expel it from his own lungs, he closed his eyes, and he rubbed a hand over his face. When he nodded to the man she could feel walking in their direction, he looked older than she had ever seen him.

"Explain yourself," he told her between his teeth.

But she couldn't. Not now. "There's no time," she replied—and her voice was shaking, she noticed, horrified—"Just do as I say. I'll give you my number, you can contact me later if you want, but I need you out of this station right now."

Heiwajima stared at her without moving. She knew that she must look frightful, deranged, out of her mind; she knew that her face was hot and her luggage spread around her on the floor and her hands twisting together; she knew how much her face was marked with the insomnia of the past year and how little she cared about masking this with makeup. "I'll contact you later," she said again. She tried to push him toward the exit, but he didn't bulge, not even one bit.

"Who are you?" he asked for the third time. She was staring at his chest—at the deceptively normal white shirt he wore, not unlike her own—both of her hands shaking against him. Trying to move him felt like trying to move a brick wall. "You obviously know who I am," he continued, getting rid of her grip on him once more.

So easily. As if he were batting away an annoying fly.

Ten-twenty-nine. Namie thought she could hear the train stop from where she was, its doors opening, its passengers getting out, Izaya among them.

"If you stay here," she said, throat tight, "you're going to provoke a fight."

Heiwajima's eyebrows twitched in irritation. "I haven't punched you, have I?"

She almost wanted to laugh. "You won't be able to help it."

In the second that followed she saw Heiwajima's face change; the hostility seemed to bleed out of him and leave nothing behind but closed doors. "Ah," he said. His hand released her wrists. People crawled up the escalator that led out from the platform under their feet, and they both turned to look at them spilling out into the station, carrying luggage and holding children's hands.

"You're here for him too." Heiwajima's voice was heavy.

She couldn't look at him anymore.

They stood frozen in front of his brother's movie poster, Namie's suitcases still lying on the floor, gathering dirt. She felt tied up. Strangled. The hard plastic of her bra dug into her chest with every breath she took, painful and relentless; the lighting was too harsh now, making her blink away tears and leaving gray spots in her vision.

The doors to the elevator opened again. Namie and Heiwajima turned their heads to look at them with the same breath lodged in their throats, and, she thought, with the same apprehension.

Izaya wheeled himself out of the elevator's cage and right out in the open, his black hair shining blue under the electric lights, his face turned away to look at the old man standing beside him.

"Don't," she breathed.

Heiwajima kicked her suitcase out of his way and started walking.

--

Sozoro was hovering.

He looked like a bird of prey. Today wasn't the first time Izaya had had this thought, and it wouldn't be the last; Sozoro had eyes like an eagle's and talons to go with them too—knives hidden on his person, just like Izaya did.

Izaya hadn't had much use for his knives lately.

Sorozo, though, seemed to be having the time of his life. The closer their train got to Tokyo and the sharper the glee was on his face, and Izaya was too bored, or too tense, not to ask questions.

"It'll be interesting to see how you fare there," Sozoro answered him. "Somewhere you know, among people you know. People who know you."

"I don't intend to make my presence known."

Sozoro's eyes were glinting. "Plans don't always come to fruition," was all he said.

The train ride wasn't uncomfortable. Izaya had traveled light—most of his luggage would be transported at a later date if necessary. Because of Namie's insistence that he go to Tokyo within twenty-four hours of her call, he hadn't had much time to prepare. He had to get a prescription filled and book train tickets and pack. Even with Sozoro's help, this took time.

Now he was sitting between two wagons, in a space left free for the disabled, back against the soft train seat and legs extended onto his own wheelchair in front. His laptop was on his knees, but he wasn't doing anything with it other than watching the video Namie had sent him of the creature they called Snake Hands. Over and over. Hoping for his eyes to catch a new detail.

Izaya didn't know anything or anyone who could outrun the Black Rider. It made sense to suspect that someone—or something—he didn't know might have taken Kururi.

"You're hesitant," Sozoro commented.

Izaya tensed. He lifted his right thigh with his hands, so he could cross his legs at the knee in front of him. "I'm just tired."

"Your sister has been missing for more than thirty hours now," Sozoro continued evenly. "You know the chances of finding her alive are thin."

Izaya knew. He was no stranger to abductions.

He couldn't call anyone yet, though. Not as long as he was out of the city—and, his mind whispered, not as long as Namie wasn't there.

She texted him right then, telling him where she was waiting. Izaya put his phone back into his pocket without answering.

He would be with her soon enough.

The last few minutes of travel were spent in silence for the both of them. Sozoro hadn't sat down at all through the trip; he was holding a wall loosely so as not to lose his balance in case the train slowed suddenly. Every seat except for the one Izaya had taken was free, but he ignored them all.

Izaya had to resist uncrossing his legs and crossing them again. His spine was burning harder than usual as it was. He couldn't even tell if that was his imagination—most of the pain was his imagination in the first place.

In the balance of all the painful days he'd had since waking up in the hospital, paralyzed from the waist down and both arms in casts, this one weighed toward the bad.

Izaya packed his laptop into his bag ten minutes before the train was scheduled to stop. He tugged his legs out of the wheelchair's seat and brought it closer to him. Then, after locking the breaks in place, he pushed himself onto it.

"You should've eaten before we left," Sozoro said, eyeing the way Izaya's arms shook under his weight.

"Too early to eat," Izaya replied between clenched teeth.

He let out a harsh breath once he was securely seated. His legs ached, but the worst of the pain was always at his lower back; as though someone had taken hold of his spine there and twisted their fist sideways. With a wave of his hand, Izaya ordered Sozoro to pick up his suitcase and push his backpack under the seat of the chair.

He ignored the doors opening around him. Other passengers were walking out of their assigned seats to wait near the door where he was; some of them marked a pause at the sight of him, one or two flicked their tongue in annoyance. Izaya leaned back in his seat and turned his head to look at them, lips stretching on amusement despite himself, despite everything.

"My apologies for blocking the way," he told them. "I'm in quite a bit of pain, so I'd like to hurry out."

The couple behind him seemed to deflate; soon enough, everyone in the vicinity was looking at them with animosity. Izaya entertained himself with the whispers for the last two minutes of the drive.

He barely felt the train slow and stop. The doors opened in front of him silently, the platform almost empty but for a few people come to wait directly on it; Namie would be upstairs, though, he knew.

Sozoro pushed down on the handles of the wheelchair so that its front would lift and allow to cross the small step separating Izaya from the edge of the quay.

Nothing around was especially different or stressful. Narita was a big station and a bigger airport; the chance of accidentally crossing paths with anyone he knew was small. Still Izaya felt his lungs fill with ice as he breathed, felt a tell-tale pain in his chest that he knew would soon enough be lodged in his forehead and his throat. Sozoro handed him the small pill pouch from his bag wordlessly as they waited by the elevator.

For once, Izaya didn't rue Sozoro's foresight. He didn't pretend that everything was fine. He popped an anti-emetic tablet into his mouth and swallowed it dry.

"There's nothing for you to throw up," Sozoro murmured.

"I'd rather not be nauseous at all. It's a pain to get rid of."

Sozoro didn't mention the chest pain. Izaya had pills for that, too; but Izaya would die before he admitted to needing those.

The line for the elevator was almost empty now. People kept throwing curious glances at Izaya, offering to let him go first, and Izaya smiled and waved them off. He wanted to avoid as much as the crowd as he could before meeting Namie. Finally, it was only him, Sozoro, and his luggage. The train that had driven them here had already left the platform. Izaya pushed himself into the elevator manually despite the strain on his back and let out a sigh once the doors closed.

"You're going to have a grand old time here," he told Sozoro, looking at the ceiling.

"Indeed."

Izaya chuckled. "I could introduce you to quite a few skilled fighters. One of them a former classmate of mine. She'd be delighted to take on a specialist, her usual sparring partners are mostly comprised of children."

"I'll make sure not to hit too hard," Sozoro drawled, and Izaya laughed brightly.

"Oh, I wouldn't underestimate her if I were you." The elevator stopped. A bell rang, softly, and as Izaya turned his head to look over his shoulder and into Sozoro's dark eyes, the doors started opening. "As I said, though, I don't plan on making myself—"

He choked. His mouth stayed open for a timeless second, voice gone from him; the pain in his chest disappeared entirely under the cold air that filled his lungs, thick, heavy, till they were so full of ice that he couldn't breathe at all.

He barely heard Sozoro ask, Izaya-dono? with something akin to surprise on his voice. Izaya whipped his head around to look at the crowd walking through the station, and as he did, it parted in front of him neatly, people pressing backwards to make way for the man walking in his direction.

Shizuo's eyes met his in less than a second, hooked them in and made it impossible for Izaya to look away. And it didn't matter that his eyesight blurred almost instantly or that he could feel blood rush to his head painfully, begging him to breathe again—Shizuo's face fit itself into the hole in Izaya's mind as neatly as if it had only been a day since he has last smelled murder off of the other's body and felt all the bones in his arms snap.

Shizuo stopped in front of Izaya, both of his feet hitting the ground like earthquakes; he never paid any mind to the way Sozoro moved, wrapping a hand around his wrist and no doubt pressing a blade against the blue veins there. "Izaya," he said, and the word shook through Izaya like that metal beam had twenty months prior. Painting his entire back blue and purple from the shock; twisting his spine, halting his steps.

Izaya rasped in a breath when Sozoro's blade started pushing into Shizuo's skin. He didn't check to see if the man had managed to draw blood. He couldn't look away from Shizuo's face.

"It's no use," he tried—he clenched his teeth so the shaking would stop. "Sozoro-san," he continued, louder. "You won't be able to stop him."

He could feel the incredulous glance Sozoro gave him. But the man obeyed, bound by contract and no doubt encouraged by his own dislike of Izaya—and Shizuo took another step forward, raising the hand—ah, the hand that Sozoro had grabbed, and indeed it was bleeding from a tiny cut at the wrist, already staining Shizuo's shirt sleeve crimson.

When he grabbed Izaya by the collar, the stain spread over it.

"Izaya," Shizuo growled again.

Izaya smiled, and tasted bile on his tongue as he did. "Shizuo. Long time no see."

There was no pain anymore. His entire body felt electric instead. In the pit of his stomach, heat spread, familiar and forgotten at once—but this time there was something blocking it, something that made Izaya want to scream instead of laugh and trapped all of his voice in at the same time.

It was fear. Worse than he felt even waking up from nightmares, swimming in his own sweat, thighs wet with his own piss.

Shizuo's face hadn't changed. Through the white haze Izaya saw the same nose and eyes and mouth, saw the dark roots of Shizuo's sloppily-dyed hair, saw the white teeth in his mouth as he opened it to speak again.

Except—something happened. There was a shock, enough to make even Shizuo falter slightly. Izaya's now blood-stained collar slipped out of his grip, and Shizuo broke away from his eyes to look behind himself. Izaya did the same with a scream stuck in his throat.

A suitcase fell to the floor, probably after hitting Shizuo's back. When Izaya looked up from it he saw Namie, almost comical in her fury; her arm was still extended forward after throwing it, and her face was a vibrant red.

Izaya let out the ugliest laugh, shoulders shaking and making the fabric of his clothes drag against the slick sweat at his back. "And Namie-san," he declared shakily. "My, what a reunion."

"Will you fucking leave me alone," Shizuo snapped in her direction, but all Namie did was attempt to kick him in the thigh.

"Fuck off, Heiwajima. Just—fuck you, fuck everything about you."

They glared at each other, violence gleaming at Namie's throat and straining the lines of Shizuo's back—and Sozoro stepped forward again.

"If I may—"

"Shut up," they told him, at the exact same time.

Izaya couldn't help it; he laughed again, belly aching on it, chest shaking, heart bruising his throat; it was loud enough to attract the attention of two people wearing the station's uniform and make them walk toward him in hurry.

Izaya shook a tranquil hand in their direction. The laughter had made the cold dissipate and the pain come back tenfold. "Let's take this elsewhere," he declared, leaning back into the chair.

Namie tried to walk in his direction, but Shizuo grabbed her by the shoulder to stop her. "No," he told Izaya—Izaya's stomach tightened at the sound. "I'm not fucking following you anywhere. You sit there and listen to me."

"I can't exactly run away, Shizuo."

There wasn't a hint of pity on Shizuo's face when he looked at the armchair. "Do you want me to kill you?"

And Izaya should have expected that, really; but he found that the smile left his lips as violently as it had appeared, leaving his entire face numb in its wake.

Something changed on Shizuo's face as well. Both of his hands turned to fists by his sides as he breathed—Izaya's eyes zeroed in on them, helplessly—but all he did was put them into the pockets of his jeans.

"Are you here for Kururi?" he asked lowly.

Izaya licked his bottom lip. "Did Namie tell you I'd be here?"

"I did not," Namie exclaimed, still red with rage—but it was Shizuo whom Izaya was looking at. The hatred in his eyes was not as vibrant as it was in his memories. He said, plain and honest: "I knew you were coming back. The city stank." After a breath, he added: "Been hanging around here since yesterday, just in case."

Izaya raised a trembling hand to his lips and wiped the sweat off from under his nose. "Mmh."

"Mairu is losing her shit. She asked me to help—but I don't have any fucking clue where Kururi is. Do you?"

Izaya said nothing. The white around him was worse than it had been a minute ago; he was having trouble focusing on anything, but despite even this, his entire body tensed as Shizuo approached.

"Do you?" he repeated, hunched forward so that Izaya was only a couple inches under him. "Do you have anything to do with those fucking kidnappings, Izaya?"

"No," Sozoro answered for him. He stepped in front of Shizuo; Izaya usually disliked this sort of behavior from anyone, but this time, he felt grateful. "Izaya-dono came back at his sister's request. I'm sure he'll do his utmost to find her." Sozoro's voice was dripping with sarcasm.

Shizuo didn't seem to catch it, but it didn't matter, because he knew Izaya better than any of the people here anyway. "Are you here for her?" he asked again.

"You already got your answer," Izaya muttered. He had to wipe his mouth with the back of his hand again—his face was clammy. He felt cold all over. Breathing caused the same ache in his chest that drowning would.

Shizuo pushed Sozoro away with only the strength of his wrist—if he had been in any state to, Izaya would've laughed again at the face Sozoro made. "I didn't get any answers." He put both of his hands on the armrests of Izaya's chairs, and Izaya pulled his own arms back in his lap, whip-fast.

"Why are you here, Izaya?" Shizuo asked, this time right into his face.

And Izaya had prepared lies for this; he had been still in bed all night, stomach twisting, waking up from hazy nightmares of fire-lit rooftops and a headless woman descending from heavens on stairs made of shadows; he had told himself, over and over, that coming back meant nothing to him.

He found himself telling the truth. "I'm here for the same reason I do anything," he said. "Because I'm interested, Shizu-chan."

Shizuo didn't react to the nickname. Izaya stared into the eye of the storm, the rest of the station completely gone from his mind. Voices and footsteps erased, walls painted white by his mind struggling against unconsciousness.

He realized that he was hyperventilating.

Shizuo seemed to drag all the air with him when he drew back. His steps were the only thing Izaya heard and his body the only thing he saw.

He looked like a creature from a book. Like a giant at the foot of a bridge.

"Fine," Shizuo said. Izaya blinked, and didn't see anything anymore. "Fine. I don't give a shit. Just find Kururi."

Izaya breathed a half-laugh, half-sob out. "There's no certainty that I can do that."

"Then you're even more rotten than I thought." As Izaya blinked in his general direction, Shizuo added, "Find her and get out of here for good, or this time I'll kill you for real."

"That's the plan," Izaya grit out. He heard Shizuo's footstep distance themselves from him, almost breaking out of the liminal space that fate or trauma or both had opened for them; before he could, Izaya asked, "Did you think you'd killed me?"

Shizuo stopped.

The silence was absolute, now. White and endless. Izaya thought he wouldn't have been able to notice someone touching him.

"Yeah," Shizuo said from far away. "Yeah, I thought I did."

Izaya smiled. "There I guess there's reason for you to celebrate after all. You didn't kill me." He leaned back into the shapeless space where his chair should be. "You didn't give me what I wanted."

The space broke, allowing in the white lights of the station and Namie's still-pink face in front of him. Izaya couldn't see Shizuo anywhere.

"I think I'll be passing out now," he informed Sozoro. "Namie will help you with directions."

He barely felt Namie's hand on his arm and the vicious words she threw at him in answer. The fog covered his brain and drew his eyelids shut, and with the last of his awareness he brought a hand to his collar and touched the wet, warm stain.

It was fitting, in a way. Stepping back into Ikebukuro with Shizuo's blood at his throat.

--

Kururi opened her eyes to a hospital-like room.

She had never had to go to a hospital herself. Neither had Mairu. Her mom had always said that she and her sister were healthier than anyone she knew—never got worse than cut knees or bruised eyes, even with Mairu's training at the dojo. She used to compare them to Izaya, because Izaya got sick often, according to her. Flu after flu, cold after cold. Perpetually underweight. Always an insomniac.

Kururi couldn't ever remember seeing her brother sick. Or at least not in the physical way. It might have been before, though; before the time she started to look at Izaya, before she realized that there was a fifth member to their family that she ought to get to know.

The ceiling was bare and grey. Dirty. Not a hospital, she thought faintly. Hospitals must look better on TV than they did in real life, she knew, but she didn't think one would look quite this bad.

Not a legal one, at least.

Kururi let her head fall sideways on the pillow. She was lying on a low bed, almost to floor-level. Other beds were in the room, with other people in them. There was a plastic pole next to her holding a transparent bag of… something. A tube went out of it, dropping down to her level, up to the crook of her elbow where a needle was stuck into her skin.

She tried to move, but found that she couldn't.

Mairu, she thought.

She felt as though she had slept for a very long time. The memories of being grabbed by the middle and lifted off the Black Rider's bike came to her sluggishly. Like trying to remember a dream.

Had Mairu been taken too?

She couldn't hear any voices. The people she could see next to her all seemed to be asleep or at least drugged, like she had been.

Her heart almost jumped out of her chest when something touched her face, but she couldn't move away from it. A hand grabbed her by the chin gently and made her turn her head back.

"There's only so long we can make a child sleep," the woman above her said.

She had a red coat on. At first, that was her most distinguishable trait. Kururi blinked forcefully, until she could see enough to make out the woman's features. She was pretty. Light-colored hair held up above her nape, warm skin and soft fingers against Kururi's cheek, wide eyes. Kururi couldn't guess her age. She smelled of flowers and smoke.

Her eyes were yellow.

The woman patted Kururi's hair briefly. "Don't panic," she said. "Though, I guess that's a little useless. You seem pretty calm already."

Kururi opened her mouth, forced her voice to come out. "M-Mairu…"

"Your sister's safe. I only need one of you, after all." She had a melodious voice, every word singing itself out of her. It might have been because of the drugs, but when she carded her hand through Kururi's hair once more, Kururi relaxed into it. "You really are family," the woman murmured. "He wasn't anxious in the least when I caught him either."

What do you mean? Kururi wanted to ask. But the woman fiddled with something on the pole, and already the room was blurring into black around her. Already all that Kururi could make out was the deep red of the woman's coat—and the bright glow of her inhuman eyes.

"Shh," the woman said. "Your brother is full of lies. Even back then, he made sure to protect you from me." Kururi opened her mouth silently; the woman patted her shoulder and stood up, her face disappearing into the dark.

"He'll come," she said. "Even if he doesn't care about his family."

Her eyes flashed, burning bright spots into Kururi's sight every time she closed her eyes; and Kururi saw the woman raise one of her soft hands and examine the sharp, gleaming claws protruding out her fingertips.

"He'll be too curious not to."

[PREVIOUS] [NEXT]

21 notes

·

View notes