#inflicted damage (neg) with my previous edit

Photo

Late to close, and late to open...

#OFMD#Our Flag Means Death#ofmdaily#ofmdedit#Gentlebeard#Blackbonnet#Edward Teach#Stede Bonnet#Rhys Darby#Taika Waititi#Edit#inflicted damage (neg) with my previous edit#so time to inflict damage (pos) with the kiss HKSLDS#Shoutout to Stede being so blown away that he doesn't shut or open his eyes right away like#L O R D#I've been very eye emoji @ his eyes like WOW I NEED TO GIF THAT HSDKLS#insane#absolutely insane#can you believe they invented love#can you believe they also invented first kisses#incredible

460 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Naruto: Passion of the Shinobi”: A Naruto fan-made fighting game #6 - Early roster overview part 3

Last edited: 2019-05-05

The Jonin of the Leaf, with some surprises

Itachi Uchiha

Most likely to be the favourite within the fandom, Itachi was actually no between my initial intentions, but instead was added after the insistence and the suggestions of a friend of mine.

Since this is the first part Itachi, most of his moveset will be based around genjutsu. Aside from the damaging tsukuyomi, Itachi is planned to use a series of a variety of genjutsus that will put different handicaps and annoyances onto the adversary. Examples of potential effects include:

Rearranging their buttons

Inverting their directions

Inverting the high-low blocking directions

Changing their special inputs

Forcing the damage of a combo onto the opponent

Since it’s the first part, Susano’o will not be a part of hist moveset, so his damaging specials will be limited to fire jutsu as well as Amaterasu.

From this, ramifications appear. In the first place, it is necessary to determine the way genjutsu will work in terms of range, fail state and block properties. Then, a mechanic for characters to release themselves from genjutsu could be necessary, as Itachi is not the only candidate character armed with genjutsu.

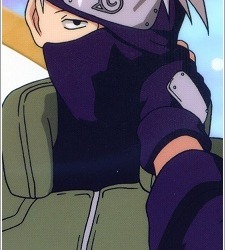

Kakashi Hatake

Kakashi is a really troublesome character in terms of design, canon and production. So much so that he may not make it in even though he is such an iconic character. So, what is the deal with him?

For the most part, Kakashi’s abilities overlap with Sasuke’s. The one thing that make him special is the ability to copy jutsu (which technically is also available to Sasuke, but clearly not as prominent). This ability creates multiple problems.

In the first place we have the design problem. How should the Sharingan come into effect? Options are the following:

At any time: Activating at any time makes it so you can’t choose what jutsu to copy, which would limit the jutsu you can copy to 1. Alternatively, multiple slots could grant multiple jutsu that are copied randomly or in a pre-set order.

After a jutsu: Almost like the previous one, but requiring a jutsu to be performed first. The jutsu copied is the last that has been performed by the opponent.

As a counter: This option seems like the most reasonable, but is a problem for jutsu that don’t hit, unless it is triggered by the execution instead of the hit.

The bigger problems come now. First, we have the problem of the canon. As fans will know, there are a series of techniques known as kekkei genkai that are tied to a specific clan’s genetics and are impossible to copy. Some characters, mainly the Hyuuga, are entirely composed of these techniques. So copying either remains canonical and becomes useless or goes against the canon.

Finally, we have the production. It is not viable to produce sprites for Kakashi executing every single jutsu in the game. An alternative to this could be reusing the opponent’s sprite with some effects applied, in which case a dilemma appears with hitboxes. Though it is the only viable way of implementing it as of the writing of this entry.

With this, Kakashi is a mix and match character that could potentially be a jack of all trades or a badly put together mess of a character at the choice of the user.

Mitarashi Anko

The first of the 2 surprise characters. Such an underrated character. For this one, as well as for the next one, I’ve decided to create a moveset for them since the canon has a dramatic lack of information. For Anko, the only established jutsu is shown during her clash with Orochimaru. Based on her personality, role, and known jutsu, I’ve decided to base her around animals. Snakes, of course; but also spiders, ants and a very special kind of shrimp.

Her playstyle is a hit and run style based around poison and a series of keep-away tools. She wants to poison the enemy in any way and keep the poison up as she keeps herself out of reach with her other tools. These new, non-canonical tools include:

Poison saliva: in order to complement her canonical snake jutsu in the role of inflicting poison, Anko will be able to lick her kunai to cover it in poison for a period of time.

Spider webs: Both that you can set (think of Testament’s traps in GGX2) and that you can throw in a similar fashion to that of the Deinopidae family of spiders or “Net-casting spiders”. These obstruct the path between your opponent and yourself as well as granting the chance to inflict more poison.

Poison explosion: Similarly to one of Samurai Shodown’s characters. This move leaves a clone on your position while leaving you a bit back. The clone will then explode leaving fluids with toxins that will poison your enemy further. This move is inspired by a very special series of ant species known as “explosive ants”, such as the Colobopsis saundersi

Implosive bubble: a direct damage super. A mix between Water Prison jutsu and the skills of the Alpheidae or “Pistol Shrimp”. In this move, Anko imprisons the opponent into a water prison and snaps her fingers for an imploding bubble that for a moment reaches up to approximately 5000ºC.

Yuuhi Kurenai

And as the final candidate we have Kurenai. Another left out character that seemed extremely interested but was never developed. The canon information we have is that she is a genjutsu prodigy and, as such, she is the second genjutsu user in the game.

Not much is established around her from my part either so far. But there are 2 main points I want to focus on:

Use of genjutsu exclusively, as opposed to Itachi’s mix of genjutsu and ninjutsu. This does not include her normal moves... or maybe yes.

The use of plants within her genjutsu. Her aesthetic points to the iconography of a rose, and the one time we see her using her jutsu it involves a tree. From that I decided to make all her genjutsu based on plants, and making them damaging genjutsu as opposed to obstructive moves.

Some of the early ideas for her include:

Field of roses: Sets a surface across which roses will flourish, dealing constant damage to the opponent when it is standing on it.

Negative edge attacks: In a similar fashion to Arakune’s insects in Blazblue, she could use plant based attacks based on negative edge.

Discrete distance projectiles into teleport attacks: based on her attempt at attacking Itachi, she could make trees raise at different distances as a mean to directly attack the opponent. Furthermore, once set, she could use them to teleport into them and attack from there. A bit like Rachel’s spears in Blazblue.

Corpse flower: based on the flower species by the same nickname (Amorphophallus titanum, Rafflesia family), this attack would set a blooming flower that would take a long time to actually bloom, but would do fast, over time damage all over the screen until the jutsu is broken or maybe if the plant is destroyed.

At the moment I’m still thinking of possibilities and looking up weird plants in search of more botanical goodness.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sensory Deprivation

There’s a lot of confusion in the press, fiction and occasionally research about sensory deprivation. So as with solitary confinement I’ll start off with some definitions.

Sensory deprivation set ups reduce or mask at least the following senses: sight, hearing, smell and touch.

Additionally some equipment reduces the sensation of gravity.

I try to avoid describing tortures as ‘extreme’. I feel this can imply that some tortures are ‘less damaging’ or ‘safer’ and this is not true.

However the way that sensory deprivation damages human beings demands the term.

This is extreme.

It is almost uniquely damaging and the speed and extent of the damage inflicted is frankly terrifying.

Thankfully sensory deprivation has never ‘caught on’ as a torture.

I accept that as writers we often depict things that aren’t true to life. My advice regarding sensory deprivation is usually to avoid it. It has only been used to torture in isolated cases (a small number of mental health facilities in America) and the damage to characters is so severe that functioning in a basic way is unlikely.

I’m going to cover methods of sensory deprivation and then go on to the effects seen in volunteers and victims. So if you do decide to use it in your story you can do it as accurately as possible.

Baldwin’s Box

Confusingly not developed by Baldwin (it was developed by Donald Hebb who used it in ethical experiments), ‘Baldwin’s box’ is actually a small room. It’s padded and equipped with a ventilation system that masks smells from outside.

It is sometimes soundproof and sometimes the occupants wear ear muffs to mask sounds. It can be dark or under a constant, low lighting level. The interior is uniform and undecorated.

Occupants occasionally wear oven gloves, dark glasses or padded clothing to further mask their senses.

Baldwin’s box has been used in ethical and consensual experiments but it has also been used on unconsenting mental health patients and members of the American armed forces.

This is a structure that has to be specially built and quite sizeable. That means it both costs money and is relatively easy to detect. This is something that you’d need planning permission for.

So if you decide to use Baldwin’s Box sensory deprivation in your story consider how the structure was built or adjusted and how it might be disguised. Does your villain have the resources to build it from scratch? Do they have the space for this kind of structure? If they build it themselves where do they get the materials and are the materials flimsy enough that the occupant could break out (something that happened in at least one real life case).

Lilly’s Tank

Lilly’s tank is a sealed structure that’s significantly smaller than Baldwin’s box but significantly larger than a coffin. They might be around the size of a double bed (although Lilly’s original was significantly larger).

The tanks either has an air regulation system that masks smells from outside or a breathing mask that goes over the occupant’s head. It’s sound proof and it closes over the occupant cutting out light sources. Then tank is filled with a saline solution, kept at body temperature. This masks the sense of touch generally and also reduces the ability to feel temperature and creates a feeling of weightlessness.

Lilly’s tank affects more senses than Baldwin’s box. It’s significantly more complicated to make but smaller and commercially available. They’re currently used in some spas as a relaxation treatment, usually for an hour at a time.

Lilly, to his very great credit, halted his research and left his institution shortly after receiving questions on the use of his tank against ‘involuntary subjects’. His tank was never used on anyone unwilling and the vast majority of his research was done by experimenting on himself.

They’re expensive, the spa varieties are somewhere between $3,500-6,500 (via Rejali). They’re also cumbersome, difficult to maintain and full of water. This means that an unconsenting occupant would have ample opportunity to drown themselves, making their use as a torture device extremely unlikely.

Time frames for sensory deprivation experiments

As with solitary confinement the amount of time a volunteer will stay in one of these devices is a really important measurement.

During Hebb’s work using ‘Baldwin’s Box’ half of his volunteers left at around 24 hours. The extreme outlier in the group stayed in the ‘box’ for six days. Most of the others had left after two days.

In contrast the longest a volunteer has stayed in Lilly’s tank is 10 hours with the average duration a little under 4 hours.

Effects of Sensory Deprivation

Sensory deprivation produces extreme disorientation, insomnia, confusion, loss of ‘disciplinary control over the thinking process’ and hallucinations in willing volunteers.

Let me give you an example of what that means.

Hebb’s volunteers were so disorientated that they sometimes got lost inside the bathroom they went to for breaks and couldn’t leave it without assistance. One of them started hallucinating after 20 minutes. Hallucinations in Lilly’s tank occur in under three hours.

So far as I can tell willing volunteers who were confined for short periods (24 hours or less) didn’t suffer any lasting effects.

Beyond that the situation begins to get somewhat murky due to unclear records and poor research practices.

Baldwin, after whom the box is named, locked a US Army ‘volunteer’ in a sensory deprivation chamber for 40 hours during which Baldwin’s notes describe the man breaking down, crying and begging to be released. The ordeal ended when the man kicked his way out of the box.

Ewen Cameron subjected around 100 patients to sensory deprivation along with forced ECT keeping one woman ‘Mary C’ confined for 35 days.

A follow up study of 79 of Cameron’s patients ten years later noted unspecified ‘physical complications’ in 23% of the group. 85% were either hospitalised or ‘maintain psychiatric contact’.

60% had lost large chunks of their memory surrounding their time as a research subject, lost memories ranged from six months to ten years. 75% were judged as ‘unsatisfactory or impoverished’ when it came to interacting with other people and forming social bonds. Of the patients who had been working before they went into Cameron’s hospital around half could no longer work full time.

All of these people had received treatment in the intervening time.

In 1980, around thirty years after the experiments, a group of Cameron’s former subjects sued the CIA and Canadian government. Two of these people were unable, thirty years later, to recognise faces or everyday objects.

Some of the sources I’ve read recently that followed up Cameron’s patients suggest that a small number of them were able to leave hospital, find employment and live a relatively normal life. Which goes against my previous statements that all of them were permanently hospitalised or otherwise in care.

It’s not clear whether these victims were subjected to shorter periods of sensory deprivation.

Further factors to keep in mind

Sensory deprivation is, by definition, also solitary confinement. So victims subjected to sensory deprivation will also be suffering from the negative effects of solitary confinement and the effects of solitary confinement are likely to be exacerbated by the effects of sensory deprivation.

A lot of the asks I’ve had referring to sensory deprivation seem particularly interested in the effect this would have on children. Thankfully no one has ever done that experiment. My best guess is that the effects would be much much worse and would affect the child’s development and ability to interact with others profoundly.

The confusion and disorientation caused by sensory deprivation is also extreme enough that a character confined in this way might not be able to reliably eat, drink or take medication they’re provided with. Remember the long term is one day.

This is not as detailed as I’d like it to be; I’m struggling to find better sources. Hopefully this helps put sensory deprivation in perspective and clears up some of the questions people have had.

Sources

For clarity I’m breaking these into the ones I’ve actually read in full (which come first) and the original source or research material with some further reading.

Torture and Democracy by D Rejali, Princeton University Press, 2007

Cruel Britannia: A Secret History of Torture by I Cobain, Portobelo 2012

‘Effects of Decreased Variation in the Sensory Environment’ by W H Bexton, W Heron, T H Scott, Canadian Journal of Psychology 1954, 70-76

‘Production of Differential Amnesia as a Factor in the Treatment of Schizophrenia’ by D E Cameron, Comprehensive Psychiatry 1960

Intensive Electroconvulsive Therapy: A follow-up study by A E Schwartzman, P E Termansen, Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal 1967

The Search for the Manchurian Candidate, by J Marks, Norton Co 1991

The Mind Manipulators, by A Scheflin E Opton, 1978

A Textbook of Psychology, by D Hebb 1966, 2nd ed

‘Effects of Repetition of Verbal Signals upon the Behaviour of Chronic Psychoneurotic Patients’ by D E Cameron, L Levy, L Rubenstein, Journal of Mental Science 1960

Edit: Spending a short amount of time in one of Lilly’s tanks on a consensual basis does not make you better able to describe the hallucinations, terror and psychotic breaks they can cause when someone is locked in one for a prolonged period (over an hour) against their will.

Disclaimer

#tw torture#sensory deprivation#masterpost#unethical experimentation#tw ableism#Baldwin's box#Lilly's tank#effects of sensory deprivation

338 notes

·

View notes

Text

Practicing Medicine While Black (Part II)

By KIP SULLIVAN

Managed care advocates see quality problems everywhere and resource shortages nowhere. If the Leapfrog Group, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, or some other managed care advocate were in charge of explaining why a high school football team lost to the New England Patriots, their explanation would be “poor quality.”

If a man armed with a knife lost a fight to a man with a gun, ditto: “Poor quality.” And their solution would be more measurement of the “quality,” followed by punishment of the losers for getting low grades on the “quality” report card and rewards for the winners. The obvious problem – a mismatch in resources – and the damage done to the losers by punishing them would be studiously ignored.

This widespread, willful blindness to the role that resource disparities play in creating ethnic and income disparities and other problems, and the concomitant widespread belief that all defects in the US health care system are due to insufficient “quality,” is difficult to explain. I will attempt to lay out the rudiments of an explanation in this essay.

In my first article in this two-part series, I presented evidence demonstrating that “pay-for-performance” (P4P) and “value-base purchasing” (VBP) (rewarding and punishing providers based on crude measures of cost and quality) punish providers who treat a disproportionate share of the poor and the sick.

I begin this second installment by presenting some of the evidence indicating that providers who treat a disproportionate share of the poor and the sick suffer from fewer resources, and that P4P and VBP (hereafter just VBP) worsen resource disparities. I will then argue that this outcome is the direct result of a habit, now deeply ingrained among health policy experts and managed care advocates, of calling resource-related problems “quality” problems. I will describe instances of this behavior that occurred early in the history of the “quality” crusade that began in 1999 with the publication of To Err is Human by the Institute of Medicine (IOM).

First do some harm

I closed my last article noting that CMS’s Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) may be killing up to 5,000 seniors with congestive heart failure (CHF) every year. Under the HRRP, CMS tracks readmissions for CHF, heart attack, pneumonia and a few other diagnoses. Readmission rates above the national average for patients with these diagnoses are punished by reductions in all Medicare payments to the “bad” hospitals. The savings from the penalties inflicted on the “bad” hospitals are redistributed to the “good” hospitals.

We have no research yet on the mechanism that might cause the HRRP program to harm CHF patients, but we know this much:

Research has established that the HRRP as well as other VBP programs punish providers who serve a high proportion of the nation’s sickest and poorest patients, and

this terrible outcome is caused by CMS’s inability to adjust readmission rates and other “quality” measures, as well as cost measures, to reflect accurately factors outside clinic and hospital control, the most important of which are the health status and incomes of their patients, and the resources available to the clinics and hospitals.

The result of these and other VBP programs (ACOs, “medical homes,” MACRA, and possibly bundled payments) is that hospitals and clinics serving the nation’s poorest and sickest people are being drained of vital resources.

Harming the poor to improve “value”

The November 2017 edition of Medical Care contains a paper demonstrating that two Medicare VBP programs, the HRRP and the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program, both implemented in 2013, have hammered hospitals in poorer communities. [1] The authors noted at the beginning of the paper, “Previous studies showed that the … HRRP and the … HVBP disproportionately penalized hospitals caring for the poor.” They stated their goal was to determine how this difference in penalties affected the financial performance of poor hospitals compared with better-off hospitals.

The paper compared the financial performance of hospitals serving the eight-state Mississippi Delta Region with non-Delta-region hospitals over the period 2008 through 2013. The authors, Hsueh-Fen Chen et al., used two measures of financial performance: Operating margin (income from hospital services minus the cost of those services) and total margin (income from all sources minus all costs). They selected the Delta Region because it is much poorer than other regions in the country. [2]

The authors found that Delta hospitals started and ended the study period (2008-2013) with fewer resources than the non-Delta hospitals – they served more Medicare and Medicaid patients, and had lower operating and total margins over the entire study period. Figures 1 and 2 show the changes in operating and total margins for the two groups of hospitals.

Figure 1 Delta hospitals and other hospitals in the United States 2008-2014

Figure 2 Delta hospitals and other hospitals in the United States 2008-2014

Figure 1 is the more revealing of the two. It shows that both groups of hospitals suffered negative or zero-percent operating margins over the study period, but Delta hospitals suffered substantially worse margins. The Delta hospital margins plummeted after 2010 to a low of minus 10 percent by 2013, while the non-Delta hospitals’ margins declined only slightly after 2011to a low of minus 1 to 2 percent. The authors surmise that margins plummeted in the two or three years prior to the implementation of the HRRP and HVBP programs in 2013 because hospitals, knowing those programs were coming, spent money on infrastructure and staff to attempt to score well on the measures used by those programs. Here is how the authors put it: “The growing gap in financial performance between the two hospital groups is likely a result of both the amount of penalties incurred from HRRP and HVBP, and the expenditure from increased investments in infrastructure for reducing readmissions and improving quality of care and the patient experience.” [3]

The authors concluded: “Policy makers should modify these two programs to ensure that resources are not moved from the communities that need them most.” “Modifying” these programs is not the solution. They should be terminated, and more resources should be funneled into to the Delta hospitals and others serving a disproportionate share of the sick and the poor.

To err is human, especially if you’re a managed care advocate

The managed care movement has exhibited a disdain for evidence since its birth in the early 1970s (see my discussion of the culture of managed care here) One manifestation of this cavalier attitude toward evidence is the problem I’m discussing in this series – the willful blindness to insufficient resources that has characterized managed-care-think since at least the publication of To Err is Human by the IOM (since renamed) in 1999. That report offered four explanations for why somewhere between 44,000 and 98,000 “preventable deaths” occur annually in US hospitals. Not one of those four explanations dealt with resource shortages. Here is how the Commonwealth Fund, a zealous proponent of managed care, articulated those four explanations in a 2005 review of the impact of To Err is Human:

The IOM report provided a blueprint for reducing medical errors, naming four key factors that contribute to the epidemic of errors. First, fragmentation and decentralization of the health care system may create unsafe conditions for patients and impede patient safety efforts. Second, licensing and accreditation processes give insufficient attention to preventing errors. Third the medical liability system, which discourages physicians from admitting mistakes, impedes systematic efforts to uncover and learn from errors. Fourth, third-party purchasers of health care offer little incentive for health care organizations and providers to improve safety and quality.

Not one word about whether insufficient resources, or misallocation of resources, might contribute to some of those “preventable deaths.” Not surprisingly, given this one-eyed diagnosis of the problem, the IOM did not recommend more resources or better distribution of resources (for example, more spending on nurses and less spending on administrative costs generated by managed care schemes). Instead, they called for “transformation” of our “delivery system” via greater consolidation of our already highly concentrated system, more pay-for-performance schemes, installation of electronic medical records across the country to facilitate the implementation of P4P, and studies of alternatives to malpractice suits.

Many studies have documented a correlation between insufficient resources and negative health outcomes. An inverse correlation between nurse-to-patient ratios and adverse events in hospitals, for example, is well established (see Aiken et al. and a review of the literature by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality ). Just as our commonsense tells us a high school football team will lose to a professional football team, so it tells us that inequitable resource distribution will profoundly affect performance by health care institutions and professionals. What possible excuse did the IOM have for ignoring the resource issue in To Err Is Human and their 2001 sequel, Crossing the Quality Chasm? If I could rewrite those books, their titles would be Conflating Quality with Insufficient Resources is To Err Big Time, and Crossing the Resource Chasm.

Misuse of the RAND paper

The IOM is to the managed care movement what St. Paul was to Christians: An indisputable authority on the religion. (I have no idea what the IOM did to warrant that status, but they unquestionably have it among the faithful.) The IOM’s willingness to deny the role that insufficient resources plays in “preventable” adverse outcomes in hospitals has deeply influenced the faithful ever since. An influential paper published by Elizabeth McGlynn and colleagues at RAND four years after the publication of To Err reinforced the principle, first clearly established by the IOM, that blindness to resource disparities is acceptable, perhaps even admirable.

The paper by McGlynn et al. was very useful. It analyzed the relative prevalence of over- and underuse. They reported that underuse occurred four times as often as overuse. “[W]e found greater problems with underuse (46.3 percent of participants did not receive recommended care …) than with overuse (11.3 percent of participants received care that was not recommended …),” the authors concluded. McGlynn et al. found, for example, that only 58 percent of stroke patients were “on daily antiplatelet treatment”; only 29 percent of suicidal patients with “psychosis or addiction or specific plans to carry out suicide” had been hospitalized; and only 5 percent of alcoholics had been “referred for further treatment.”

You might think this paper, having documented so much underuse, would have been seen by managed care advocates as a repudiation of the assumption most fundamental to their creed – that US health care costs are high because the fee-for-service system induces overuse. Nope. Instead managed care buffs seized on the paper’s underuse data as proof that “quality” is bad and doctors are to blame. The title of the paper, “The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States,” and the authors’ interpretation of their findings (they recommended closer supervision of doctors) bear some of the blame.

Managed care buffs wasted no time distorting the meaning of this paper. Shortly after it was published, I heard a lobbyist for the Buyers Health Care Action Group, a coalition of large employers in Minnesota, characterize this paper before a committee of the Minnesota legislature as follows: “Your odds of getting correct treatment when you walk into your doctor’s office are 50-50, no better than a coin flip.”

Today the deceptive practice of measuring the consequences of resource disparities but not the resource disparities themselves, and blaming the consequences on doctors and hospitals, is at epidemic levels. [4] This practice generates above-average blame and financial punishment for minority providers and the hospitals and clinics that serve a high-proportion of minority patients. This deceptive practice in turn leads to another deceptive practice: Recommending better “quality” measures to catch all those bad doctors, especially the black and brown doctors. And ‘round and ‘round the cycle goes.

A paper by Andreea Creeanga et al. illustrates both practices – blaming high-minority providers for problems caused in whole or in part by insufficient resources, and declaring that the solution is more measurement, not a better allocation of resources. Creeanga et al. sought to determine the rate of complications associated with childbirth in hospitals serving primarily black, Hispanic and white patients. The authors found higher rates of adverse events in the black hospitals. “Twelve of 15 indicator rates were highest in black-serving hospitals,” the authors wrote, “with rates of puerperal infection, urinary tract infection, obstetric embolism, puerperal cerebrovascular disorders, blood transfusion, and in-hospital mortality being considerably higher than in either white- or Hispanic-serving hospitals.” And what did the authors propose to do about this? Why, measure more, of course! “[B]etter obstetric quality-of-care measures are needed,” they intoned. What about resource disparities, you ask? Silly you. The authors made no recommendation. This is a “quality” problem, don’t you know.

Leapfrog should take the Hippocratic Oath

A decade ago, as the evidence-free P4P fad was taking off, a few intrepid observers warned that P4P could have destructive consequences, including worsening of racial disparities. Lawrence Casalino et al. were among those who issued a clear warning early on. In the title of a 2007 paper for Health Affairs they asked, “Will pay-for-performance and quality reporting affect health care disparities?” Their answer was yes: “P4P and public reporting can have serious unintended consequences, and one of these consequences may be to increase health care disparities.” Those “unintended” consequences arrived quickly. The damage done by VBP to the providers who take care of more than their share of the sickest and the poorest is now obvious.

And yet the Leapfrog Group, MedPAC and other groups and individuals who led the P4P bandwagon in the early 2000s and who flog VBP now refuse to acknowledge the damage their arrogance has caused. Some even go to the trouble of accusing their critics of stupidity or greed. In a recent article for the Harvard Business Review, posted on THCB , Leah Binder, CEO of the Leapfrog Group, and three other business representatives were willing only to concede that VBP measures “may have rough edges.” They criticized “some doctors” for daring to criticize VBP, and argued we “can’t wait for quality measures to be perfect.” And why is that? Because of the “widely acknowledged … quality-of-care issues,” said Binder et al.

Binder et al.’s “logic” is circular and faith-based:

Quality is deemed to be terrible based on studies that use crude measures of cost and quality and which, therefore, cannot distinguish the influence of resource shortages from the influence of poor quality;

because quality is so terrible, something must be done, even if it might harm the sickest and the poorest;

so P4P/VBP is unleashed, it worsens resource disparities, which in turn worsen disparities in health outcomes such as infections following childbirth;

these outcome disparities are then used to start the circular reasoning all over again: These worse outcomes are deemed to be evidence of inferior “quality,” and, in the strange world manage care advocates live in, this calls for even more crude measurement, not more resources.

What is the solution to this irrational groupthink? This is grist for a much longer essay. My short answer is that health policy researchers, and managed care proponents in particular, should mentally take the Hippocratic Oath every day. That might induce them to recognize that demanding that doctors honor the Hippocratic Oath while they themselves honor no similar principle is hypocritical. Daily recitation of the Hippocratic Oath might induce managed care zealots to recognize that demanding that doctors and patients practice evidence-based medicine while they practice evidence-free health policy is hypocritical, leads to intellectual laziness, and, most importantly, inflicts harm.

[1] The Hospital Value-based Purchasing program purports to measure both quality and cost. Quality is measured by process and outcome measures and patient “satisfaction” surveys. The surveys have been shown to discriminate against hospitals that serve a disproportionate share of minority patients. According to a RAND study ,”Hospitals with a high proportion of minority patients received lower overall HCAHPS [Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems] VBP scores than hospitals with predominately White patients.”

[2] Hsueh-Fen Chen et al. described the Delta Region in grim terms. “The Census Bureau has noted that the Delta Region is among the most socioeconomically disadvantaged areas in the United States. This region is largely rural with a large proportion of minority and underserved individuals, and has high rates of poverty, unemployment, chronic diseases, obesity, physical inactivity, food insecurity, and mortality, and low-birth weights.” As if this weren’t bad enough, the authors continued: “The Delta Region already has a significant physician shortage and poor access to care. Given the limited health care infrastructure and poor population health, Delta hospitals are … more likely to be financially vulnerable under HRRP and HVBP.”

[3] This paper on the Delta hospitals is a rare example of research into the costs doctors and hospitals had to incur to participate in managed care schemes. Since the birth of the managed care movement a half-century ago, the American health policy community has shown virtually no interest in measuring the additional costs imposed upon our health care system by managed care fads. Proponents of HMOs, gate-keeping, report cards, ACOs, “medical homes,” electronic medical records, P4P, and VBP demanded that lawmakers and payers adopt these programs without the faintest idea what these fads would cost payers (taxpayers, premium payers and out-of-pocket payers) and providers.

Unfortunately, even this paper on the Delta hospitals is insufficiently precise. The authors did not attempt to determine what portion of the financial losses suffered by hospitals since the enactment of the ACA can be attributed to penalties imposed by the HRRP and HVBP programs and what portion can be attributed to the extra costs hospitals incur to improve their HRRP and HVBP scores.

[4] Here are other examples of “experts” who claimed, either explicitly or by referring to the McGlynn paper in an endnote, that the paper measured physician quality:

· “Studies have documented that nearly one-half of physician care in the United States is not based on best practices.” (Robert Smoldt and Denis Cortese, “Pay-for-performance or pay for value,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 2007;82:210-213)

· “Physicians deliver recommended care only about half of the time….” (Richard Hillestad et al., “Can electronic medical record systems transform health care?….” Health Affairs 2005;24:1113-1117)

· “[D]espite the extensive investment in developing clinical guidelines, most clinicians do not routinely integrate them into their practices.” (Dan Mendelson and Tanisha Carino, “Evidence-based medicine in the United States.,…” Health Affairs 2005; 24:133-136).

Article source:The Health Care Blog

0 notes