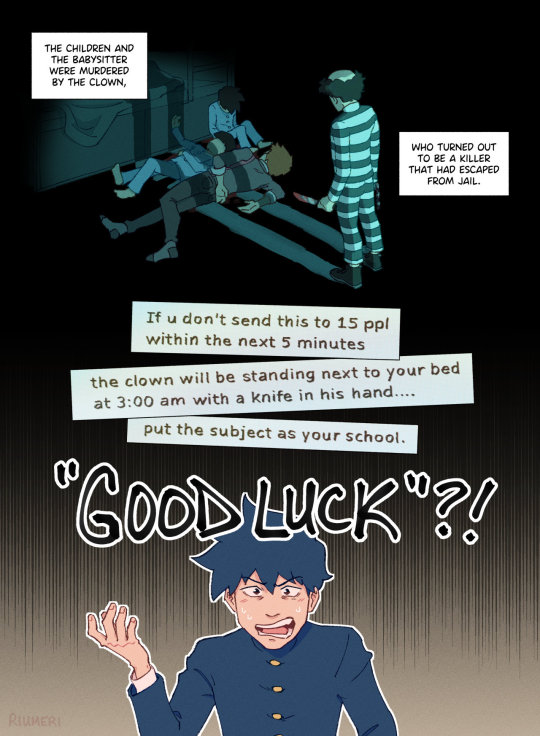

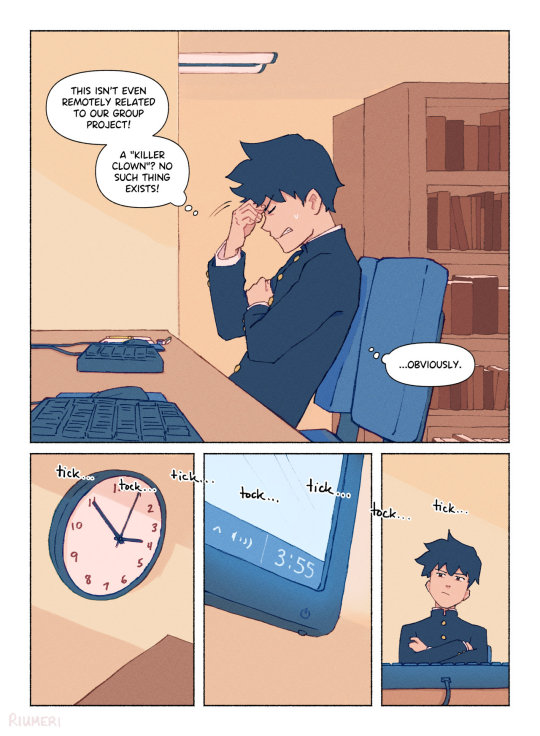

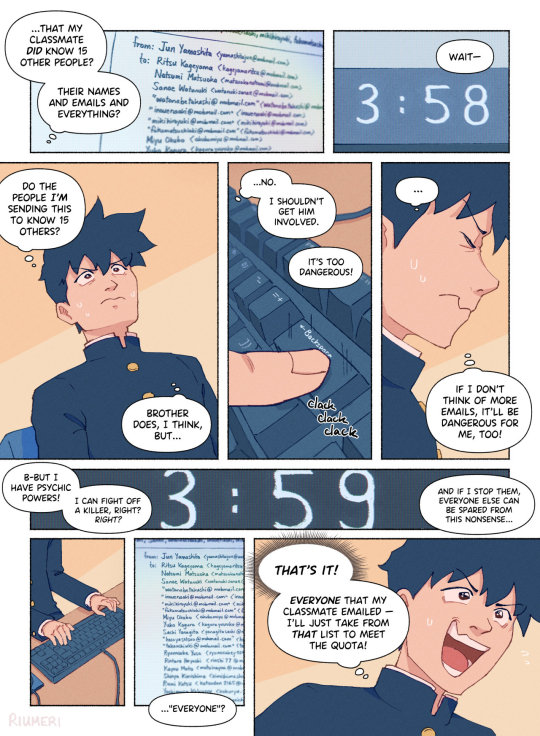

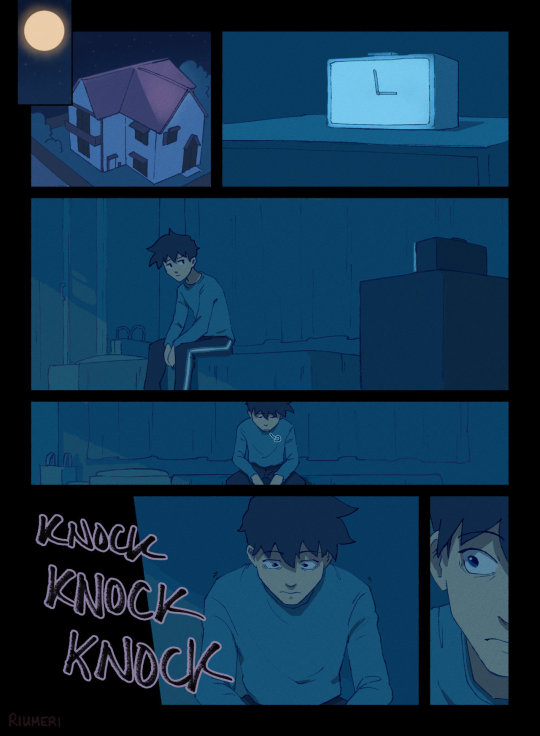

#inspired by a chain email my friend sent me in 2010

Text

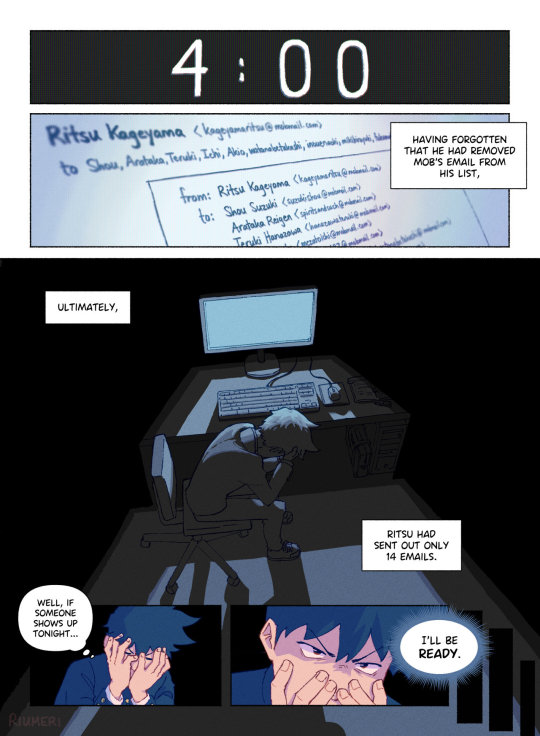

"Huh? You got a weird email from me yesterday? U-um, yeah, about that... My account was hacked, so you can just ignore it."

#mob psycho 100#mp100#kageyama ritsu#reigen arataka#hanazawa teruki#comic#teruritsu#riteru#(if you squint)#i struggled A LOT with this comic for the past several months so i'm happy it's finally done!!!#inspired by a chain email my friend sent me in 2010#and also i'm just a huge fan of ritsu being Dramatic.#(also also sneaking in teruritsu crumbs for myself and like. the 5 other people who love this rarepair lmao)

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

I Donated A Kidney To A Stranger At Age 51 And It Changed The Course Of My Life

Lucy [all names have been changed to protect privacy] and I had taken to studying together in the cafeteria. As a woman twice her age, I naturally probed her with questions about her young life. We eventually took up the topic of her vegetarianism. Picking at her tiny salad with a plastic fork, she explained how she mostly ate fruits and veggies because protein was harder for her diseased kidneys to process. Later that day, as I watched this beautiful, intelligent, and lively young woman hunched over her Scantron in the classroom, the mother in me took over. I hurriedly finished my test and waited outside the classroom. As soon as she came through the door, I told her I wanted to give her a kidney. She thanked me, but turned me down. She said that she appreciated the offer, but she’d made peace with her situation and that I should let it go.

MORE: 7 Types Of Friends Every Woman Needs In Her Life

I told her I would let it go, but I’d lied. I would let it go with her, of course, at her request, but I had already chosen organ donation as my topic for another class. In my research, I learned that 15 people die each day in the United States alone because they didn’t receive a needed kidney in time. I was moved to tears as I read through heartbreaking pleas; people begging for someone to save them or their afflicted loved one. It wasn’t long before I understood that I was meant to meet young Lucy. And that writing the paper was not about proving a thesis—it was about proving that each one of us has the ability to make a difference…and sometimes, the opportunity.

Even before I’d finished writing the paper, I signed up on an online donor-recipient matching website. After scrolling through hundreds of heart-wrenching profiles, I selected a recipient named Kathy, a hospice nurse close to my age who lived in Northern California. Her hospital sent me a kit of vials to have my blood tested locally. While we waited for the results, Kathy and I exchanged emails and eventually spoke on the phone. In contrast to my giddiness about a potential match, Kathy was grateful but sober. She warned me that due to high antibodies she was really difficult to match. And she was right; six weeks later I learned we were not compatible. Because I couldn’t donate to Kathy directly, we signed up for a “paired match” program to hopefully find a donor and recipient in the same situation so we could swap places. After three years of waiting, we never found one.

PREVENTION PREMIUM: Doctors Misdiagnose 1 In 10 Patients—Here’s How To Protect Yourself

By this time I’d gone through rigorous testing that included kidney scans, chest x-rays, mammogram, colonoscopy, more blood vials, urinalysis and other various tests to determine that I was healthy enough to donate. I was. Although saddened by not being able to help Kathy, with whom I’d now created a deep friendship, I wasn’t about to give up. If I’d learned anything in this process, it’s that once your eyes have been opened to a problem, looking away is no longer an option. With help from my transplant coordinator, I signed on as an altruistic donor through the National Kidney Foundation to donate to an unknown recipient. Within a week a perfect match was found.

My nephrectomy took place on December 17, 2010 at California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco. When people ask about my recovery, my answer is that the caffeine headache the next day was much worse than any incisional pain. If I hadn’t been hooked up to an IV, I’d have crawled three blocks for my morning espresso. I donated on a Thursday and went home on Sunday. The surgical discomfort was managed with medication and within a week I was down to a Tylenol. I returned to work three weeks later.

Strengthen your core with this simple yoga move:

My mission to become a donor had involved many unexpected stops and starts and a lot of waiting but three years after I began the quest, my kidney took a redeye flight to the opposite coast where it continues to faithfully churn away in a stranger’s body. I know this because I sent an “adoption letter” with my kidney that my recipient used to track me down on Facebook. I learned that his wife had donated a kidney in order for him to receive mine. There were more transplants in the chain I started, but I’m not sure how many.

MORE: This Woman Lost Nearly 40 Pounds So She Could Donate Her Kidney To A Friend

My remaining kidney has gleefully taken up the slack and I feel healthier than ever, physically, mentally, and spiritually. The laparoscopic surgery has left three tiny scars that have faded so that I have to really look closely to find them. And that’s where I thought the story would end. I assumed I’d just go about my business of practicing massage therapy and living a quiet life in my little town of San Luis Obispo, California knowing that I’d made a positive contribution to society. What I now know is that this event was just the first page in the next chapter of my life. In the decade since deciding to become a living donor, I’ve come to understand that our actions don’t occur in a vacuum. Our seemingly simple choices create tiny ripples that spread both internally and externally.

People want to know why I’d donate to a complete stranger. After discovering how little information was available on the topic of living donation, I’d agreed to participate in ‘Perfect Strangers,’ a documentary film that follows the story of anonymous kidney donation, in hopes of answering this question. Once the documentary released, I traveled with the filmmaker to screenings of Perfect Strangers where I participated in Q & A’s after the film. During these interviews with attendees, it became clear that the film did an excellent job of showing the “who, what, where and when” of kidney donation and transplant. Explaining the why of my choice to donate was much more complex. But I tried. I accepted invitations to speak. I volunteered to mentor prospective donors. I became a moderator for a couple of Facebook support groups for those thinking about donating. Over time I realized I was only reaching a handful of people. I needed to find a way to share my story—and the stories of all those still waiting for a miracle—with a wider audience.

MORE: 7 Things You Need To Know About Organ Transplants

I knew I had to tell my story to a wider audience if I was ever going to fully communicate how my upbringing and experiences had shaped my choice to become a donor, or how deeply that event has affected my life. I published Lost in Transplantation in 2014 at the tender age of 55. The book was well-received, and I felt satisfied that not only had I done a positive thing for my recipient, but I’d also hopefully educated or even inspired others. Readers might not decide to become a living donor, but perhaps a few would see how helping someone else takes you out of yourself and gives your life deeper meaning and greater purpose. And how helping one individual helps the collective whole.

End of story, right? Happily, no! In the process of speaking and publishing my memoir, I gained the confidence to blow the dust off my fiction manuscripts and re-read them. I revised and polished one of the novels and eventually queried a few agents. My debut novel, This I Know, releases in April of 2018. I’ll be 59-years-old. And I’ll be 60 when the following book publishes.

People still ask me why I donated a kidney to a stranger. My answer is that I was raised to believe we have a responsibility to be of service to one another. The act of donating does not define me, but it has definitely shaped me. Flannery O’Conner penned the iconic phrase, “The life you save may be your own.” My own life didn’t need saving. I was a happy and content woman in mid-life. Still, when I look back on the day I bumped into that lovely young woman at a local college who shared her story with me, I had no idea it would alter my own story in so many significant ways. Some people call it fate. Others call it karma. 10 years ago I never expected to feel so joyous, so fulfilled and so grateful for having the opportunity to change someone’s life. And I never dreamed that someone would be me.

from Health Insure Guides http://ift.tt/2xydRWj

via health insurance cover

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://www.hcdistro.com/store/notekillers-ny-times/

Notekillers in NY Times

Revival for the Notekillers, Still Noisy After All These Years

By SARAH GRANT APRIL 14, 2017

David First, in his Brooklyn apartment, led the noise-rock band the Notekillers, who played the New York music scene in the late 1970s and early ‘80s. Credit Demetrius Freeman for The New York Times

The student and the teacher faced each other on plain black foldout chairs. It was past 9 on a windy night, and this was David First’s last guitar lesson of the day. The student, Karen D’Ambrosi, a shy 28-year-old marketing manager at Etsy, began strumming one of Mr. First’s electric guitars. He joined in, gently plucking a melody over her chords.

In the next room, Mr. First’s wife, Mira Gwincinska Hirsch, listened in the dark, eating a piece of pumpkin pie. A small table lamp illuminated a jasmine flower in a red vase.

The scene was surprisingly tranquil considering that Mr. First, 63, is something of a lost noise-rock legend. In the late 1970s, his avant-rock band, the Notekillers, performed at clubs that now exist only as urban myths, like CBGB and Hurrah. Their songs were fast, jagged and wordless. They shared stages with volatile performers from Glenn Branca to the Misfits.

Before the lesson, Mr. First sat at his kitchen table with a mug of piping tea, clearly aware that his sedate appearance — cargo pants, button-down shirt, tea — belied his punk credentials.

But evidence of Mr. First’s rock ’n’ roll past abounds in his third-floor walk up in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Every wall seemed to be adorned with a Notekillers concert poster, and the group’s record covers were mounted on bookshelves. Their single, “The Zipper,” turned out to be pivotal for a band that went much further than the Notekillers.

“‘The Zipper’ was one of the Top 10 documents for me at the time,” Thurston Moore, singer and guitarist for Sonic Youth, said in an interview recently. “It was emblematic of the guitar music that inspired me. I mean, this guy was shredding like Hendrix.”

But in those pre-internet days, the Notekillers’ obscurity wasn’t a badge of honor. It was proof to the band that it had failed. One day in 1981, after four years together shuttling back and forth from the Lower East Side to their native Philadelphia, the trio (Mr. First, along with the bassist Stephen Bilenky and the drummer Barry Halkin) took the New Jersey Turnpike home and gave up on the New York music scene.

Photo

Mr. First performing at the Roulette in Brooklyn. “For 25 years, I just thought we had no impact,” he said of the Notekillers. “So to find out that we had a major influence — let alone on Sonic Youth — that was pretty huge.”CreditDemetrius Freeman for The New York Times

“We really weren’t connecting with people,” Mr. First said impassively.

Now, more than 30 years after inspiring Sonic Youth, the Notekillers are coming somewhat closer to having a moment.

The past 12 months have been a kind of renaissance for Mr. First, who released two solo records in addition to a new Notekillers album. He has just returned from performing at the Tate Modern in London as part of an exhibition of the experimental artist Phill Niblock. And he just released an album of pop songs, under the name Star Ballads.

“I’ve always thought David was one of the most underrated musicians,” said Kyle Gann, a Bard College professor and composer, who befriended Mr. First after years of covering his live performances for The Village Voice. Mr. Gann’s son, Bernard, formed the metal band Liturgy after taking guitar lessons from Mr. First. (He also plays bass on the Star Ballads record.)

“David’s music is amazing,” said Mr. Gann, who included Mr. First in his book, “American Music in the Twentieth Century.” “It’ll start strangely out of tune and then it just goes haywire in slow and gradual ways. He’s made the hair on the back of my neck stand up many times.”

Recognition was a long time coming, but one day Mr. First woke up and his fate changed.

About 15 years ago, Mr. First got a phone call from Barry Halkin, the drummer in the Notekillers. The glossy British music magazine Mojo published an article about the musicians who inspired the guitar innovations of Sonic Youth. Among more celebrated favorites, Mr. Moore singled out the Notekillers.

“Honestly, I assumed it was a mistake,” Mr. First said. But he sent a note to Mr. Moore, just to double-check.

The astonishment was mutual.

“I was blown away when David emailed me,” Mr. Moore, 58, said with boyish exuberance. Mr. Moore immediately wrote back and offered to release a Notekillers compilation on his own record label.

Photo

Notekillers circa 1979. From left: Stephen Bilenky, Barry Halkin and Mr. First. CreditBarry Halkin

“For 25 years, I just thought we had no impact,” Mr. First said. “So to find out that we had a major influence — let alone on Sonic Youth — that was pretty huge.”

Mr. First rang his former bandmates to gauge their interest in playing again. The drummer had become a successful architectural photographer. The bassist designed custom-made bicycles.

“I said to them, ‘Maybe the world’s finally ready for us.’”

The compilation Mr. Moore released in 2004 catalyzed the Notekillers’ reunion after 23 years. They released a record in 2010 (“We’re Here to Help”) and another last year, “Songs and Jams Vol. 1.”

The Notekillers — all of whom are 63 — now do gigs at Brooklyn sites with rock bands half their age.

“To think that we’re still doing this at all,” Mr. First said, his voice trailing off. “Not to mention doing it better than we did it the first time, is still unreal to me.”

Mr. First grew up in a middle-class neighborhood in Philadelphia. His parents encouraged him creatively by letting his band, three Grateful Dead-worshiping teenagers (who later became the Notekillers), rehearse in their basement. By 1976, the Notekillers, already entrenched in Philadelphia punk clubs, were drawn by New York’s thriving avant-garde music scene.

But they found the downtown scene was difficult to crack.

“Back then, nobody really knew how to play guitar in a traditional sense,” Mr. Moore said. “And if you did, it was an anomaly.”

Photo

Mr. First giving lessons to Karen D’Ambrosi at his apartment. He has worked quietly as a guitar teacher since the Notekillers disbanded. CreditDemetrius Freeman for The New York Times

Before forming Sonic Youth, Mr. Moore said that his band, the Coachmen, also failed to emerge from the same scene.

By 1984, the Notekillers were over, and Mr. First relocated permanently to Manhattan, working part time as the manager of a cookie store in Midtown. He paid $75 a week to live in a transient hotel, chaining his guitar to his bed before going to work.

A year later, he was laid off from another job, as the manager of an ice cream shop. This was not a setback but a windfall. During six months of paid unemployment, Mr. First finally had time to do music full time, playing solo and with other ensembles he formed. And, critically, he amassed a cadre of students to teach guitar for extra cash when necessary. He never worked a 9-to-5 job again.

As a free musician, Mr. First has flourished. Now he is considered a beacon of futuristic sound among experimental composers.

Though much of his music is heavily electronic, at a recent performance at the Roulette theater in Downtown Brooklyn, Mr. First switched among very traditional acoustic instruments during a suite of improvisations: a crimson sitar, a scalloped-neck electric guitar from Vietnam and a harmonica (just the regular kind). His ensemble partners were equally diverse: a violist, a trombonist and a percussionist.

“People who know me in these contexts would be very surprised to find out I’d been in this crazy rock band,” Mr. First said.

As are his students. Today, Mr. First composes and records from his Greenpoint apartment thanks to an amalgam of creative grants and commissions. Through it all, he has maintained his side gig as a guitar teacher.

Ms. D’Ambrosi, the Etsy employee, asked Mr. First for guitar lessons through a mutual musician friend five years ago. “I remember seeing on Facebook that he was in this band, but we didn’t really discuss it,” she said. “We just play Bob Dylan and Neil Young.”

A version of this article appears in print on April 16, 2017, on Page MB1 of the New York edition with the headline: SNoisy After All These Years. Order Reprints

0 notes