#lirainosaurus

Text

someone (doesn't know about the eating habits of the lirainosaurus): do you have any plans for this weekend

me (knows about the eating habits of the lirainosaurus): no the lirainosaurus ate them all

331 notes

·

View notes

Text

69 notes

·

View notes

Note

How flexible were the tails of dinosaurs? While I just need some clarification for dinosaurs as a whole, I would specifically like to know the tail flexibility of dinosaurs such as Thyreophorans, Hadrosaurs, Sauropods, Theropods, etc.

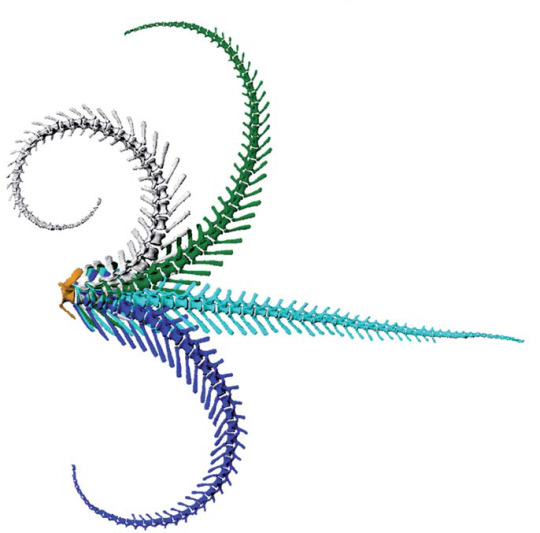

Tail flexibility has only been quantitatively estimated for a few dinosaurs. Here is an example showing the up-and-down flexibility estimated for the tail of the early sauropodomorph Plateosaurus (from Mallison, 2010). The uppermost (white) tail shows maximum upward flexion if greater freedom of movement is assumed for the tail vertebrae (which can be influenced by factors that we can’t directly observe, such as the amount of cartilage present), whereas the green tail directly below it assumes less freedom of movement.

Estimated side-to-side flexibility for the tail of Plateosaurus, from the same study.

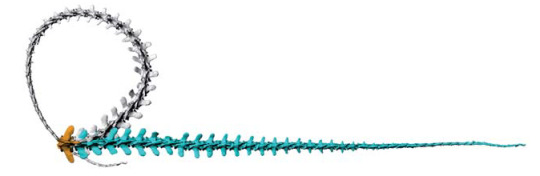

Estimated flexibility for the tail of the titanosaur Lirainosaurus (from Vidal and Díez Díaz, 2017). Downward flexibility is shown in “C”, upward flexibility in "D", and sideways flexibility in "E”.

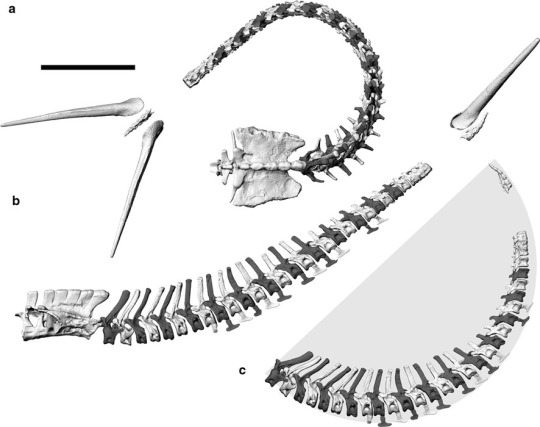

Estimated flexibility for the tail of the stegosaur Kentrosaurus, from another paper Mallison got published in 2010. Sideways flexibility is shown in "a”, upward flexibility assuming relatively little freedom of movement in "b", and upward flexibility assuming more freedom of movement in "c".

As you can see, even slight differences in assumptions can make big changes in how flexible we might think a dinosaur’s tail is. Regardless, these studies should set a good baseline for what a typical dinosaur tail would be capable of.

It should be noted that many other dinosaurs have adaptations to stiffen the tail, and accordingly have less flexibility than in the examples above. Tetanuran theropods have tail vertebrae that interlock, with dromaeosaurids in particular taking this to an extreme by having very long, rod-like extensions of the tail vertebrae. Various ornithischians (including hadrosaurs and pachycephalosaurs) had hardened tendons lining their tail. However, due to the way these stiffening structures were packed together, they were probably more restrictive in the up-and-down plane than in the sideways plane, so these dinosaurs may have still had reasonable tail flexibility side-to-side. Furthermore, these dinosaurs often retain more flexibility at the base of the tail. This post by Scott Persons and this one by Scott Hartman are particularly useful for understanding dromaeosaurid tail flexibility.

In ankylosaurids, roughly two-thirds of the tail was entirely wrapped in hardened tendons, which would have prevented that part of the tail from bending much at all, essentially like a baseball bat. To swing that baseball bat, ankylosaurids kept mobile vertebrae at the base of the tail, and the figure from Arbour (2009) below shows their likely range of motion in that regard.

242 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pyroraptor olympius

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Fire Thief

First Described By: Allain & Taquet, 2000

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Dromaeosauridae

Status: Extinct

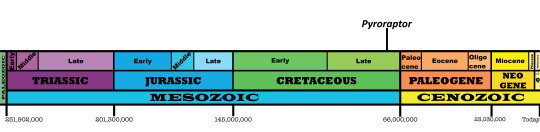

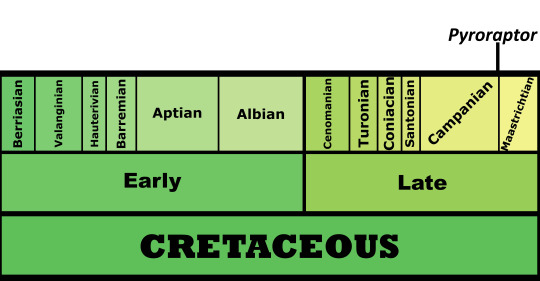

Time and Place: Around 72 million years ago, in the Campanian of the Late Cretaceous

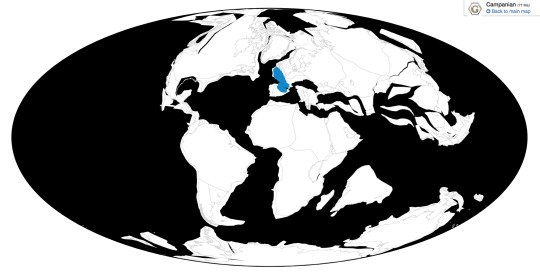

Pyroraptor is known from the La Boucharde locality in France, the Vitoria and La Posa Formations in Spain, and potential locations in the UK

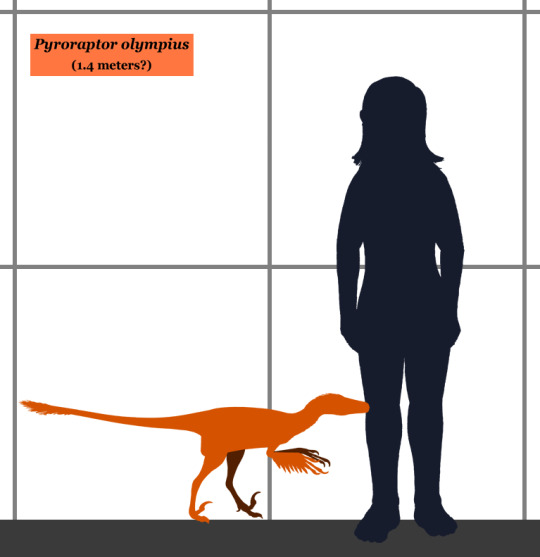

Physical Description: Pyroraptor is a poorly known raptor, based on a few fossil scraps found around the late Cretaceous of Europe. Portions of the foot, arms, and some teeth are known from Pyroraptor, none preserved very well. It had the sickle second toe claw of other raptors, and it seems to have been fairly lightweight and small - probably no longer than 1.4 meters, though that is of course an estimate. Other than that, we know very little about its appearance - we don’t even know if it was a specialized sort of raptor like in the Dromaeosaurine, Microraptorine, or other groups - except for that it would have been very fluffy, with wings on its arms and a tail fan on its tail.

By Conty, CC BY 3.0

Diet: As a raptor, it is most likely that Pyroraptor fed upon meat, probably small animals such as lizards, mammals, and turtles.

Behavior: Pyroraptor would have been a very active dinosaur, spending most of its time hopping and stalking around the rivers and beaches in its island environment. Like other raptors, it wouldn’t have been a pursuit predator, but rather an ambush one: it would have waited for prey to appear, and then pounced on it, using rapid flaps of its wings to stay balanced on top of the struggling prey. This technique, called raptor prey restraint, is still seen in living raptors today. Pyroraptor would have also been able to run up vertical surfaces, such as trees and cliffs, using flaps of its wings to gain lyft up the surface. Then, it would have been able to catch food on the run! Other than that, Pyroraptor probably wasn’t very social, based on fossil evidence from other raptors - that being said, it would have taken care of its young, and probably stayed in small family groups during this process.

By The Unknown Horror From the Ocean Depths, CC BY-SA 4.0

Ecosystem: Pyroraptor lived in the Late Cretaceous of Western Europe, which was a series of islands sitting in a shallow ocean - sort of like the Bahamas today. These ecosystems were easy to travel between, utilizing rafting and other forms of impromptu sea travel, so the animals on them tended to be similar to each other. Pyroraptor itself lived with many turtles, snakes, sharks, and gars; as well as Eusuchians such as Musturzabalsuchus and Acynodon. There was some sort of large Azhdarchid pterosaur, too - currently called Azhdarcho, though that’s a questionable assignment. As for other dinosaurs, there were Abelisaurids there, Titanosaurs like Lirainosaurus, Nodosaurids like Struthiosaurus, the Ornithopod Rhabdodon, and another raptor called Richardoestesia, and the protobird Gargantuavis!

By José Carlos Cortés

Other: Pyroraptor was named as such because it was discovered after the occurence of a forest fire. Since so little is known about this dinosaur, there isn’t much more to be said about its phylogenetics or history of discovery! It is rather famous for having been featured in the 2003 documentary Dinosaur Planet, though given its poorly preserved nature, the wisdom in that choice of star is mildly suspect.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Allain, R. and P. Taquet. 2000. A new genus of Dromaeosauridae (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of France. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20(2):404-407

Allain, R., and X. Pereda Suberbiola. 2003. Dinosaurs of France. Comptes Rendus Palevol 2:27-44

Angst, D., E. Buffetaut, J. C. Corral and X. Pereda-Suberbiola. 2017. First record of the Late Cretaceous giant bird Gargantuavis philoinos from the Iberian Peninsula. Annales de Paléontologie

Astibia, H., E. Buffetaut, A. D. Buscalioni, H. Cappetta, C. Corral, R. Estes, F. Garcia-Garmilla, J. J. Jaeger, E. Jiminez-Fuentes, J. Le Loeuff, J. M. Mazin, X. Orue-Etexebarria, J. Pereda-Suberbiola, J. E. Powell, J. C. Rage, J. Rodriguez-Lazaro, J. L. Sanz and H. Tong. 1990. The fossil vertebrates from the Lano (Basque Country, Spain); new evidence on the composition and affinities of the Late Cretaceous continental faunas of Europe. Terra Nova 2:460-466

Carpenter, K. (1998). "Evidence of predatory behavior by theropod dinosaurs". Gaia. 15: 135–144.

Carpenter, K. 2002. Forelimb biomechanics of nonavian theropod dinosaurs in predation. Senckenbergiana Lethaea 82: 59 - 76.

Carrano, M. T., and S. D. Sampson. 2008. The phylogeny of Ceratosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 6(2):183-236

Chanthasit, P., and E. Buffetaut. 2009. New data on the Dromaeosauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of southern France. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France 180(2):145-154

Delcourt, R., and O. N. Grillo. 2014. On maniraptoran material (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from Vale do Rio do Peixe Formation, Bauru Group, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 17(3):307-316

Erickson, G. M., K. Curry Rogers, D. J. Varricchio, M. A. Norell, X. Xu. 2007. Growth patterns in brooding dinosaurs reveals the timing of sexual maturity in non-avian dinosaurs and genesis of the avian condition. Biology Letters 3 (5): 558 - 61.

Fowler, D. W., E. A. Freedman, J. B. Scannella, R. E. Kambic. 2011. The Predatory Ecology of Deinonychus and the Origin of Flapping in Birds. PLoS ONE 6 (12): e28964.

Gauthier, J., K. Padian. 1985. Phylogenetic, Functional, and Aerodynamic Analyses of the Origin of Birds and their Flight. Hecht, M. K., J. H. Ostrom, G. Viohl, P. Wellnhofer (ed.). The Beginnings of Birds. Proceedings of the International Archaeopteryx Conference, Eichstätt: Freunde des Jura-Museums Eichstätt: 185 - 197.

Gishlick, A. D. 2001. The function of the manus and forelimb of Deinonychus antirrhopus and its importance for the origin of avian flight. In Gauthier, J., L. F. Gall. New Perspectives on the Origin and Early Evolution of Birds. New Haven: Yale Peabody Museum: 301 - 318.

Godefroit, P., P. J. Currie, H. Li, C. Y. Shang, and Z.-M. Dong. 2008. A new species of Velociraptor (Dinosauria: Dromaeosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of northern China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28(2):432-438

López-Martínez, N. 2000. Eggshell sites from the Cretaceous-Tertiary transition in south-central Pyrenees (Spain). In A. M. Bravo & T. Reyes (ed.), First International Symposium on Dinosaur Eggs and Babies, Extended Abstracts 95-115

Manning, Phil L., Payne, David., Pennicott, John., Barrett, Paul M., Ennos, Roland A. (2005) "Dinosaur killer claws or climbing crampons?" Biology Letters (2006) 2; pg. 110-112.

Martyniuk, M. 2016. You’re Doing It Wrong: Microraptor Tails and Mini-Wings. DinoGoss Blog.

Pereda-Suberbiola, X., H. Asibia, X. Murelaga, J. J. Elzorza, and J. J. Gomez-Alday. 2000. Taphonomy of the Late Cretaceous dinosaur-bearing beds of the Lano Quarry (Iberian Peninsula). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 157:247-275

Prum, R.; Brush, A.H. (2002). “The evolutionary origin and diversification of feathers”. The Quarterly Review of Biology. 77 (3): 261–295.

Rothschild, B., Tanke, D. H., and Ford, T. L., 2001, Theropod stress fractures and tendon avulsions as a clue to activity: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, p. 331-336.

Senter, P., R. Barsbold, B. B. Britt and D. A. Burnham. 2004. Systematics and evolution of Dromaeosauridae (Dinosauria, Theropoda). Bulletin of the Gunma Museum of Natural History 8:1-20

Torices Hernández, A. 2002. Los dinosaurios terópodos del Cretácico Superior de la Cuenca de Tremp (Pirineos Sur-Centrales, Lleida). Coloquios de Paleontología 53:139-146

Torices, A., P. J. Currie, J. I. Canudo and X. Pereda-Suberbiola. 2015. Theropod dinosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous of the South Pyrenees Basin of Spain. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 60(3):611-626

Turner, Alan H.; Pol, D.; Clarke, J.A.; Erickson, G.M.; Norell, M. (2007). “A basal dromaeosaurid and size evolution preceding avian flight”. Science. 317 (5843): 1378–1381.

Turner, AH; Makovicky, PJ; Norell, MA (2007). “Feather quill knobs in the dinosaur Velociraptor”. Science. 317 (5845): 1721.

Vila, B., M. Suñer, A. Santos-Cubedo, J. I. Canudo, B. Poza and A. Galobart. 2011. Saurischians through time. In A. Galobart, M. Suñer, & B. Poza (eds.), Dinosaurs of Eastern Iberia 130-168

Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pp.

Xu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Kuang, X.; Zhang, F.; Du, X. (2003). “Four-winged dinosaurs from China”. Nature. 421 (6921): 335–340.

#Pyroraptor olympius#Pyroraptor#Raptor#Dinosaur#Bird#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Dromaeosaur#Dinosaurs#Factfile#Birds#Cretaceous#Eurasia#Carnivore#Theropod Thursday#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#Feathered Dinosaurs

384 notes

·

View notes

Text

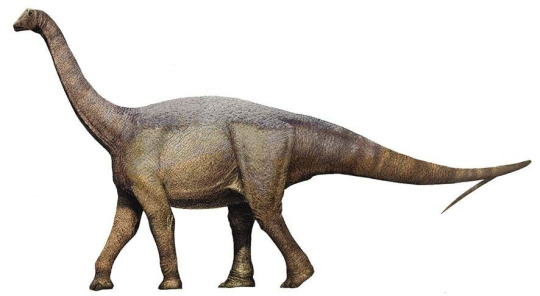

Lirainosaurus astibae

Source: http://dinosaurpictures.org/Lirainosaurus-pictures

Name: Lirainosaurus astibae

Name meaning: Slender Reptile

First Described: 1999

Described By: Sanz et al.

Classification: Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Sauropodomorpha, Plateosauria, Massopoda, Sauropodiformes, Anchisauria, Sauropoda, Gravisauria, Eusauropoda, Neosauropoda, Macronaria, Titanosauriformes, Somphospondyli, Titanosauria

Nothing good can stay, my friends. Lirainosaurus is another terrible titanosaur known form only a few bones - some vertebrae and a braincase which isn’t that exciting, trust me, it might sound exciting but its not. It was found in the Sierra Perenchiza Formation and Vitoria Formations in Spain and is known, admittedly, from a few individuals. It lived from the Campanian to early Maastrichtian ages of the Late Cretaceous, between 83 and 72 million years ago. Given its fragmentary remains, its phylogenetic placement is uncertain, though it probably had osteoderms.

Sources:

http://www.prehistoric-wildlife.com/species/l/lirainosaurus.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lirainosaurus

Shout out goes to @dattmavid!

#lirainosaurus#lirainosaurus astibae#dinosaur#sauropod#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile#dattmavid#dinosaurio#mokoweri#үлэг гүрвэлийн#ဒီနောဆီးယား#δεινόσαυρος#דינוזאור#공룡#恐竜#dinosaurus#dineasáir#डायनासोर#ديناصور#ডাইনোসর

24 notes

·

View notes