#lm 1.5.5

Text

"The human face of Javert consisted of a flat nose, with two deep nostrils, towards which enormous whiskers ascended on his cheeks. One felt ill at ease when he saw these two forests and these two caverns for the first time. When Javert laughed,—and his laugh was rare and terrible,—his thin lips parted and revealed to view not only his teeth, but his gums, and around his nose there formed a flattened and savage fold, as on the muzzle of a wild beast. Javert, serious, was a watchdog; when he laughed, he was a tiger. As for the rest, he had very little skull and a great deal of jaw; his hair concealed his forehead and fell over his eyebrows; between his eyes there was a permanent, central frown, like an imprint of wrath; his gaze was obscure; his mouth pursed up and terrible; his air that of ferocious command."

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

I actually don’t think it’s true to say Hugo “intended” for Javert to be Romani. I admit my own feelings on this have changed over the years. :( The thing that was the final nail in the coffin to “this was almost certainly not *Hugo’s* original intent” was when I listened to a talk from a person studying race in Les Mis and they addressed Romani Javert specifically. It really feels like the more you study the passages that people pick to support this interpretation, the more the claim this was “definitely Hugo’s intent” seems to hold less water.

To be clear I don’t think Hugo’s intent is the be-all end-all, and that people can reinterpret things, and that reinterpretation is good. I also think people can reasonably disagree on translation/interpretation. but if we’re talking about the original intent….

If you read any other of Hugo’s works, there is never this level of ambiguity when he is trying to indicate a character is Romani. He is especially never this ambiguous when a character is dark-skinned enough to not pass as white. He is explicit. (And he’s racist. Hugo sucked.) Romani characters in other Hugo novels both before and after Les Mis are basically always explicitly said to be Romani, in a way that Javert never ever is.

Even in Les Mis we see a handful a characters who are supposed to be nonwhite, and it’s always very explicit. Hugo was racist and also very unsubtle.

The passage people usually cite as proof Hugo intended Javert to be Romani are two lines in his backstory— one saying that his mother was a fortune teller, the other saying that he’d come to hate “the race of bohemians from which he’d sprung.”

There are two words commonly used for “bohemian” in French. one is usually is used for the race of Romani people and the other usually used as a general adjective. Apparently the term that Hugo uses here is the one that is more commonly used as a general adjective. Saying “this passage is meant to clearly explicitly indicate he is Romani” seems to me like it’s mistranslating it; at best, it seems like you can argue there is possibly some intentional ambiguity.

Later on we also get a description of Cosette that describes her as “the bohemian who walks barefoot,” and the word for bohemian used in that passage is actually the French word that’s more associated with the race. (It’s being used in that context in the racist way people use g*psy as an adjective.) But people are far less likely to interpret dainty innocent Cosette as Romani compared to “violent” “brutal” and “savage” Javert who “hates his own race.”

The “fortune teller” mother could play into bigoted Romani stereotypes— but it could also into bigoted stereotypes about poor/lower class people, which often broadly overlap. Because of racism a lot of the way characters are coded as lower class/being on the fringes of society, and coded as Romani, broadly overlapped.

And “race” is being used in a more general sense here to refer to class, the way Hugo uses it often.

None of the early adaptations of Les Mis go with the Romani Javert interpretation. I can’t find old reviews that mention it. To me this indicates this isn’t what people at the time would’ve gotten out of the story either, especially because Hugo doesn’t seem to have gone on the record about people missing it. And again if you contrast that with other Hugo novels, where reviewers and adaptations DO all get which characters are meant to be read as Romani..:it just doesn’t seem to hold water that this was definitely what an audience was supposed to get from it.

And even if this was Hugo’s intent (and I don’t think it was)….well then it’s a catastrophic failure? Then it’s very Badly Written and shallow and horribly handled?

Because Les Mis is about how people with different kinds of marginalization face very different specific challenges. A character’s gender, class, level of education, criminal record, age, etc etc etc all affect the way that they’re treated and there’s lots of explicit discussion of that constantly.

So if Javert was intended by Hugo to Romani, and especially if he was supposed to be visibly nonwhite— well then it’s a failure of the narrative because Hugo never does any deep research or analysis of how his race would actually affect his life. Even in the very racist and bad novel Notre Dame De Paris/the Hunchback Of Notre Dame, there is explicit discussion of the way being Romani affects the character’s lives and how they’re treated in a way that we never ever ever see with Javert. It’s poorly handled and racist, but it’s there.

But if you want any of that explicit discussion about race to be in Les Mis you have to do the research and add it yourself, because it is just…Not There.

There’s no discussion of Romani culture and Javert’s distance from it, there are no scenes showing the way Javert interacts with other Romani people, there’s no explicit discussion of actual Roma people at all really, and (if Javert’s meant to be read as someone who doesn’t pass as white) theres no discussion of the way being visibly nonwhite would affect his life in such a deeply racist society. literally none of that is there. If Javert is supposed to be Romani there is an utter lack of care paid to how that would actually affect him and the way he’s marginalized, in a way you don’t see with how Hugo handles gender or class.

Again to me it seems like if Hugo intended for Javert to be Explicitly Definitely Roma, we would know; if he intended for him to visibly nonwhite, we would definitely know.It’s not just that the way he codes Javert doesn’t resemble the way he handles Romani characters in other books… it’s also that it doesn’t resemble the level of detail/care he usually pays to Exactly what background each character comes from and Exactly how it affects their lives.

It seems like what fans often do is take Javert’s internalized classism and label that as “internalized racism?” But I feel that while there are similarities because “class” in the 19th century was often treated as something immutable and biological, and classes were often described as a “race”, they’re really not the same thing.

And like, I’m not here to tell people what to do! people can reinterpret things how they want and bring their own takes on the story. Hugo sucked and was shitty and racist. A lot of my favorite Les Mis fanfics are one that take characters Hugo probably intended to be white and reinterpret them as POC, doing research into how that would’ve affected their experiences. But at the same time….

Many other people before me have pointed out that there is a Trend to which characters in which Les Mis tend to be more commonly reinterpreted as POC. There is a reason why “savage” “violent” oppressive cop Javert was played by a black actor on broadway years before we got our first black Valjean.

As someone who used to have this interpretation, I think Javert is a challenging character to attempt to reinterpret as a POC (without massive changes to his characterization) if you’re doing it for “good diverse representation” because he just, sucks so badly. Especially if he’s written as the only POC in the cast, he’s just a mess. He’s described as violent. As beast-like. He’s a bigoted cop. He’s brutal. He’s hideously ugly. He canonically refuses to think because he hates thinking. He hates the “race” (meaning class of poor people) he comes from. Every time we see him he’s compared to a savage animal. And yeah that’s …a lot of baggage! He is a character made entirely of baggage. And adaptations like BBC Les mis show the kind of uncomfortable racism that ends up being brought to the surface when Javert is one of the few main POC in the cast.

But yeah. TL:DR; There is ambiguity in Javert’s initial description, and I see why people have this interpretation. I think people can reasonably disagree on it. But over the years I’ve come down on the side of, it’s a bit misleading to say this is Definitely Clearly Exactly Canonically what Hugo intended and that adaptations/fans are whitewashing him.

To be clear I also think that reinterpreting characters is great and good! And that reinterpreting characters as POC, doing the research that Hugo didn’t, is especially good! but also that Javert in particular is a problematic hornet’s nest of unfortunate implications that kinda have to be managed, and that whether you disagree that this was “Hugo’s intent” or not there’s a massive gap in the story when it comes to discussing race that would sorta need to be filled with outside research.

#Les mis#javert#lm 1.5.5#I dug this out of my drafts to post before tomorrow#but yee#anyway#now I go back to radio silence#: (

109 notes

·

View notes

Photo

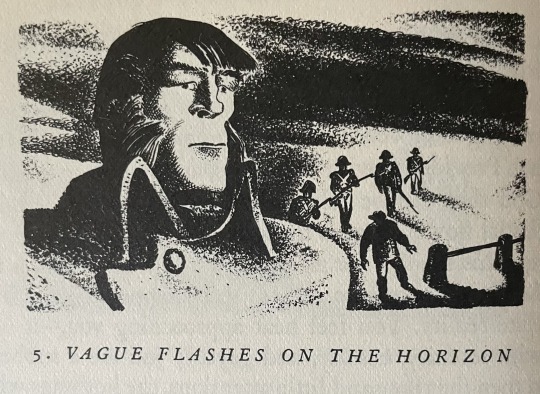

LES MIS LETTERS IN ADAPTATION - Vague Flashes on the Horizon, LM 1.5.5 (Les Miserables 1925)

One single man in the town, in the arrondissement, absolutely escaped this contagion, and, whatever Father Madeleine did, remained his opponent as though a sort of incorruptible and imperturbable instinct kept him on the alert and uneasy. It seems, in fact, as though there existed in certain men a veritable bestial instinct, though pure and upright, like all instincts, which creates antipathies and sympathies, which fatally separates one nature from another nature, which does not hesitate, which feels no disquiet, which does not hold its peace, and which never belies itself, clear in its obscurity, infallible, imperious, intractable, stubborn to all counsels of the intelligence and to all the dissolvents of reason, and which, in whatever manner destinies are arranged, secretly warns the man-dog of the presence of the man-cat, and the man-fox of the presence of the man-lion.

#Sometimes I really hate that we're using Hapgood as the translation#wtf is this#Les Mis#Les Miserables#Les Mis Letters#Les Mis Letters in Adaptation#Javert#Les Mis 1925#Les Miserables 1925#LM 1.5.5#Jean Toulout#silentfilmedit#filmedit#lesmisedit#lesmiserablesedit#lesmiserables1925edit#pureanonedits

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is our conviction that if souls were visible to the eyes, we should be able to see distinctly that strange thing that each one individual of the human race corresponds to some one of the species of the animal creation

rip vicky you would have loved the golden compass

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

I saw the use of “man-dog” and “man-cat” and thought it was interesting for Hugo to hyphen these phrases when he normally just includes animal comparisons as explanations for a specific action.

Then Javert appeared, and it all made sense.

#les mis letters#lm 1.5.5#javert#the animal imagery is so intense with Javert#he really does take his dog identity very seriously#and so much of the rest of the chapter is animal imagery as well!

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

I looked up Joseph de Maistre because he came up in today's chapter of Les Mis, and found this on his Wikipedia page:

Liberal critic Émile Faguet described Maistre as "a fierce absolutist, a furious theocrat, an intransigent legitimist, apostle of a monstrous trinity composed of pope, king and hangman, always and everywhere the champion of the hardest, narrowest and most inflexible dogmatism, a dark figure out of the Middle Ages, part learned doctor, part inquisitor, part executioner".

Well okay then

#les mis letters#lm 1.5.5#joseph de maistre#tbh I still don't 100% understand the reference but the reason this thinker is significant to Javert is not hard to understand

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

the way hugo uses local legends to tell his story… the whole thing with the devil at montfermeil, and the thing with the wolf pups of the asturias. it adds such depth and flavour, i am continuously impressed!

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm now ahead on Les Mis Letters, having decided to read all of Part One in one gulp based on what @fremedon says in this post (thematic/tone description of the rest of the book, no plot spoilers).

A few comments on 1.5 through today's email, not recapping or comprehensive, just things I noted:

Chapter 1.5.4, "Monsieur Madeleine in Mourning": I cannot begin to say how upsetting I found the long paragraph about the beauty of "being blind and being loved" (by a woman, specifically):

to know you are the center of every step she takes, of every word, of every song, to manifest your own gravitational pull every minute of the day, to feel yourself all the more powerful for your infirmity, to become in darkness, and through darkness, the star around which this angel revolves—few forms of bliss come anywhere near it!

Gah!!!!!

Chapter 1.5.5, "Dim Flashes of Lightning on the Horizon":

What a heck of a character introduction:

The Asturian peasants are convinced that in every litter of wolves there is one pup who is killed by the mother because otherwise it would grow up to devour all the other pups.

Give that male wolf puppy a human face, and you’d have Javert.

(I strongly disapprove of Hugo's conflation of beauty with virtue, so this is not about the appearance but the analogy.)

Chapter 1.5.9, "Madame Victurnien's Success": Well. There's the interiority I was wondering if we'd get for Fantine. Shame it isn't under better circumstances.

Chapter 1.5.10, "Continued Success": Hugo loves irony with these chapter titles, huh? It really works.

Rose's translation of the last line here echoes the last line of book three. Compare:

... she had given herself to this Tholomyès as to a husband, and the poor girl had a child.

With:

The poor girl made herself a whore.

It's very effective.

#les mis letters#les miserables#julie rose translation#lm 1.5.4#lm 1.5.5#lm 1.5.9#lm 1.5.10#mine-ish

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les mis censorship adventures 9

lm 1.5.5

"That man was composed of two very simple and very good feelings, within reason, but that he almost turned bad by dint of exaggerating them; respect for authority and hatred of rebellion.(CUT) Javert enveloped in a sort of blind and deep faith every one who had a function in the state, from the prime minister to the rural guard."

(Old spanish translation, Nemesio Fernandez Cuesta 1862 p. 155-156)

"That man was composed of two very simple and very good feelings, within reason, but that he almost turned bad by dint of exaggerating them; respect for authority and abhorrence of rebellion; and, from his point of view, theft, murder, all crimes were nothing but forms of rebellion. Javert enveloped in a sort of blind and deep faith every one who had a function in the state, from the prime minister to the rural guard."

(New spanish translation, Maria Teresa Gallego Urrutia 2013 p. 198-199)

crimes bad idk

THEN they cut out the line where it's mentioned Valjean is nice to Javert.

"Javert was like an eye always fixed on Mr. Madeleine: an eye full of conjectures and suspicions. Mr. Madeleine had finally noticed; but it would seem such a thing meant little to him. He didn't ask Javert a single question; he neither sought him nor ran from him; and suffered, without appearing to know of it, that uncomfortable and almost heavy gaze. (CUT)"

(old translation)

"Javert was like an eye always glued to Mr. Madeleine. An eye full of suspicions and conjectures. Mr. Madeleine had ended up aware of it, but he gave the impression of thinking it insignificant. He didn't ask Javert a single question; he neither sought nor avoided him; he bore, as if he didn't notice it, with that annoying and almost oppressive gaze. He treated Javert like he did everyone else, with ease and kindness."

(new translation)

#les mis censorship#les mis letters#les mis#lm 1.5.5.#also this is not a censorship thing but in lm 1.5.3 new translation has 'he's a lone wolf' about valjean from the ladies instead of 'bear'#which I like bc bear does not have that connotation that it seems to have in french so it didn't work

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub 1.5.5 ‘Vague flashes on the horizon’

..I love this chapter.

I’m mostly on the Amis side of this fandom these days, but my thirteen-year-old self grabbed hold of this character so hard some part of me is never going to get over it. I love these bizarre, contradictory sentences that pull themselves back and forth word by word on how much Javert sucks and how much his sucking is formed from admirable qualities. The text keeps trying to tug apart how his disparate elements can possibly coexist. This writing is beautiful, and love it.

Anyway.

Something about Javert makes Hugo start explaining lots of different personality theories. We have the animal-as-souls theory, the more specific dog-sons-of-she-wolves theory (“son of a bitch” was a phrase in French, right?), a theory that was apparently a fad in ultra newspapers, and so on. All of them are very external, like you just look at Javert and go “WTF?? How does any of this work?”

...Which, you know. That’s fair.

Javert’s primary motivation is to crush rebellion. In a book about the necessity of rebelling, that feels important.

He’ll meet an actual rebellion one day, and I want to revisit this then. The way he acts with actual rebels is a lot more subdued and respectful than the gruff, joking familiarity with which he (at least by the time he’s in Paris) acts towards criminals. He gets off plenty of one-liners there too--“Farewell till immediately”--but he’s much more priest/soldier of the ideal at the barricade than he will have been in a long time. It’s interesting, and I wonder what that event means to him.

It also feels so immediately clear in this description how much of the rebellion Javert is trying to crush is inside him.

Javert’s world, like the law’s world, is divided between the worthwhile people within society and the dangerous people outside it. Being in the latter category himself, he thinks his only moral choice is to protect the worthwhile people against people like himself.

Hugo is making the point that the legal system is fundamentally constructed around the question of “Whose life matters?” It’s one of the failings of the much more conservative musical that they sidestep that.

There’s something really fascinating with Javert about how mainstream morality--the morality that’s considered most “objective”--is built to serve the people in power. Marginalized people tend, for good reason, to be much more aware of what a self-serving construct that is--but Javert only ever sees himself from the viewpoint of the powerful who despise him. I suspect there’s something there about growing up isolated by institutional systems, and maybe something else there about a neurodivergent kid who learned morality from authoritative-sounding sources rather than by inference, not that I’m projecting or anything.

Unfortunately, I think this all runs straight into one of Hugo’s major blindspots.

Hugo gets that Javert is pitiable and tragic. He gets where Javert’s strange views and self-hatred come from. But Hugo is better at pity than solidarity, and there’s not much space in this novel for a sympathetic marginalized person who’s surrounded by like-minded marginalized people and who isn’t deeply apologetic and regretful about their marginalization.

That’s kind of a problem.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Javert is here! Javert is here! He is terrible and ugly. And I am excited!

So much going on in this chapter that I will touch upon just a couple of points. Hugo invented the concept of the daemon a century before Philip Pullman: “It is our conviction that if souls were visible to the eyes, we should be able to see distinctly that strange thing that each one individual of the human race corresponds to some one of the species of the animal creation.” And, of course, Javert is portrayed as the Asturian dog-son of a wolf!

While reading this chapter, I noticed two points vaguely connecting Javert and Valjean. First, my pet topic—stoicism. Javert is depicted as “stoical, serious, austere; a melancholy dreamer, humble and haughty, like fanatics.” A bit later, he is compared to Brutus, more precisely “Brutus in Vidocq.” Although the parallel with Vidocq is quite transparent, Brutus is invoked for his stoic speeches and behaviour. As far as I recall, this is the only instance when Hugo mentions Javert’s stoicism, whereas he continuously reminds us about Valjean’s stoicism. They are two old stoics of Les Misérables.

The second topic is reading. They both read, but for different reasons and with different attitudes toward books. Valjean loves reading, extracting so much from books, dedicating ample time to reading, and considering books as his 'cold friends.' On the contrary, Javert despises books, yet he reads during rare moments of leisure. My theory is that he does it out of necessity, having nothing else to occupy his time. Since “he had no vices,” he wouldn't spend his free time in a tavern getting drunk like most people of that time. He is too poor for more sophisticated leisure, and reading is an affordable pastime. Additionally, I suspect he mostly reads newspapers, allowing him to stay updated on current events.

Although Hugo doesn’t explicitly mention it, I suspect it was exceptionally challenging for Javert to reconcile his suspicion toward Valjean with his respect for authority (given Valjean's role as a mayor).

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub 1.5.3-1.5.5 (but mostly “Vague Glimmerings on the Horizon”

I didn’t have anything to say that hadn’t been said about either of the last two chapters. I know originality is not the point of this readalong and I’m trying to get better at posting even when I have nothing new to add. So let’s talk about Javert!

First, though, let’s detour and talk about Valjean, who embodies the bishop’s ideal mayor from all the way back in 1.1.3: “He ended disagreements, prevented lawsuits, reconciled enemies. Everyone recognized his authority as judge.” Earlier in the same paragraph, we are told “there came a time around 1821 when the words ‘monsieur le maire’ were uttered at Montreuil-sur-mer with almost the same expression as the words ‘Monseigneur l’évêque’ had been uttered at Digne in 1815.” And yet he seems to have had as little moral influence as the bishop—despite all his homespun wisdom about nettles, and all the people flocking to M-s-m to consult him, there are very few people following his example, and those few, like the sanctimonious deputy, are doing so out of ambition and competition.

And then we meet the one man who has still resisted this “contagion of respect” that had infected the whole area: Enter Javert.

We get a great physical description, and also a kind of puzzling one, about having the air of authority without baseness—given what else we know about Javert, how does he escape the baseness? He is a CRIME BABY, A BABY MADE OF CRIME (thank you Mellow, that will never stop being funny). Baseness is what he’s got to work with.

Aaaand we get a ton of furry imagery, more than with any other character. He’s called a tiger, once—possibly the only negative cat reference in the book—but for the most part, he’s associated with canids: mastiff, fox-man, dog-man, and, most notably and chillingly, the dog son of a wolf, who if not killed by its mother will grow up to eat the rest of her young.

I’m really fascinated this time through by just how much of the language used about Javert in his introduction is going to be echoed in other characters. Even this image of the dog-child-of-a-wolf will be used again—by Éponine, of herself, in the standoff outside the Rue Plumet house. There was a good conversation about Javert and Éponine’s parallels on the Discord recently—including the fact that they switch deaths; Javert gets the self-drowning foreshadowed for Éponine and she gets shot at the barricade as he was supposed to.

I’m going to keep coming back to that, and to the idea that Javert’s story, or his fate, has gone wrong—has been derailed* long before he is, or allows himself to become, aware of it. And almost from Javert’s first page, he and Éponine are yoked by this image of a story that went wrong even before birth: the dog son of a wolf, permanently shut out from its own society, at odds with its parent, locked in a death struggle with its siblings.

That metaphor makes a fascinating frame for Éponine’s zero-sum game with Cosette—and for the idea we were talking about, about how a loving foster family would certainly have shared her fortune. Javert, we are told, “Would have arrested his father for escaping from prison and denounced his mother for contravening the terms of her release from jail”—but he only does this metaphorically, by proxy. Éponine will very literally turn on her own parents to guard society in the form of Cosette and her happiness.

(*Oh, and look, the derailment imagery is here too: “He had introduced a straight line into what is most tortuous in the world.”)

The other character the language of his introduction evokes is Enjolras, for whom he will be set up as an actual opponent. Javert “is a spy as other men are priests.” Enjolras, of course, is the other character who gets the priest imagery, starting in 3.4.1 with his “priest of the ideal” and his variously translated “pontifical et guerier” nature.

In the same paragraph, we are told that Javert had “an understanding of the police like the Spartans’ understanding of Sparta”; in “How Jean Can Become Champ,” we get Spartan and priest juxtaposed and the juxtaposition called out: “this bizarre composite of Roman, Spartan, monk, and corporal, this spy who could not lie, this virgin snitch. ”

Enjolras is also the other character (with a couple exceptions, which I’ll come back to) who gets the Spartan references. Moving from Donougher to Rose, which I have in a searchable ebook: “Enjolras, we know, had something of the Spartan and the Puritan” in 4.12.3; and in 5.1.17, “Enjolras gravely ruled over [the barricade] in the attitude of a young Spartan dedicating his naked blade to the dark genius Epidotas.”

Given (a) the Corinthe and (b) everything, classical references are another thing that are almost always significant in this book. And aside from a few uses of lowercase ‘spartan’ to mean ‘spare’ or ‘frugal,’ there are a few other references to Sparta, all quite late in the book:

5.1.2, talking of real and fictional insurgents: “They were in the early hours of that spartan day of June 6 when, in the Saint-Merry barricade, Jeanne, surrounded by insurgents wanting bread, answered all the combatants clamouring for “Something to eat!” with, “What for? It’s three o’clock. At four, we’ll be dead.”

5.1.12, talking of the National Guard: “ Blood was lyrically shed for the good of the cash register; and the shop, that vast diminutive of the homeland, was defended with Spartan gusto.”

5.1.20, insurgents again, doomed ones this time: “They are but few; they have a whole army arrayed against them; but they are defending right, the law of nature, justice, truth, the sovereignty of each man over himself, from which no abdication is possible; and, if need be, they will die like the three hundred Spartans. It is not Don Quixote they have in mind, but Leonidas. And they forge ahead and, once they are committed, there is no going back, so they rush headlong, hoping for an unheard-of victory—complete revolution, unbridled progress, the betterment of the human race, universal deliverance; and, if the worst comes to the worst, Thermopylae.”

And then, 5.2.1, “The Intestine of Leviathan,” on our first introduction to the book’s real main character or at least its most important metaphor: "For we must flatter no one and nothing, not even a great people; wherever nothing is lacking, ignominy sits next to sublimeness; and if Paris contains Athens, the city of light, Tyre, the city of power, Sparta, the city of virtue, Nineveh, the city of wonder, it also contains Lutetia, the city of slime.”

To be Spartan, then, is not only to be virtuous, but to defend virtue—however constructed, even the bourgeois virtue of the National Guard—with one’s own life.

Other Observations:

“A good social education can always elicit from any soul whatsoever the usefulness it contains.” Well that’s a damning comment on the dirtbag students.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy “introduction of literature’s most problematic furry” day to those who celebrate!

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

LM 1.5.5 (retrobricking)

"Il se nommait Javert, et il était de la police."

FMA: His name was Javert, and he was one of the police.

Rose, Donougher: His name was Javert, and he was with the police.

Hapgood: His name was Javert, and he belonged to the police.

They're all decent , but I think Hapgood's has some real poetry to it, esp. given how often Javert is compared to/flat out called a dog.

Almost everyone has deeper thoughts and feelings on Javert than me, and I'm eager to read them, so I'll confine this to a couple points.

- Javert is described--among many other descriptions here-- as "Brutus in Vidocq". And that is an absolutely fascinating and baffling comparison to me? Because while his Vidocq qualities are obvious to anyone who knows about Vidocq, his Brutus qualities are...I will say highly debatable! Yes, there's the obvious connection with Brutus killing his sons...but that Brutus killed his sons for trying to restore the monarchy. There's the now-more-famous Brutus who killed someone many considered his friend, out of honor and duty...but the friend he killed was Caesar, and at least as a matter of popular concept he did that to prevent Caesar being made emperor. What I'm saying is that I cannot find any way that "Brutus" is not a profoundly, intensely anti-absolute-authority kind of comparison,a deeply republican symbol to invoke. And Hugo is absolutely bringing that symbolism in here on purpose! He would have had fleets of historical figures to call on if he'd wanted someone austerely and selflessly dedicated to authority /monarchy/emperors! But he picked Brutus, for M. "respect for authority and hatred of rebellion", and I have no IDEA what to do with that.

- going with that-- Hugo says Javert is made up of "two sentiments, very good in themselves" (or whatever a given translation does with that phrase) "respect for authority and hatred of rebellion". And the first two times I read it! I totally took Hugo at his word that these were being presented as Good Things! And every time I see this passage quoted it's unironic, as if those were totally meant to be Good Things...

but there's no way, is there?? There is no way that Victor Hernani Hugo ever thought rebellion didn't kinda rock or that authority should be beyond question. Even Baby Monarchist Hugo was ready to fight his teachers and Spiritual Advisors, and to harbor attempted assassins . He was not good at it but he was willing!

So uh. Yeah. "he rendered them almost bad, by dint of exaggerating them" is deep, deep sarcasm, huh. They're bad by exaggeration bc they are bad in any degree, every single line of not just this book but everything else Hugo ever wrote argues that , I was a naive fool the first couple times I read this and I am still only beginning to appreciate the absolute Marianas Trench depths of sarcasm on that line.

- Okay one more thing: I am highly entertained that Victor "This symbol is symbolic" Hugo says that de Maistre would have seen a symbol in Javert, as if Hugo hadn't just spent the whole chapter making Javert a symbol. Amazing.

#hey guess who remembered they can stim while they work?#and so can actually work now#wheee#anyway#Brickclub#retrobrick#LM 1.5.5#Javert talk

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s fascinating that out of all of the ways Hugo could have described Madeleine’s tenure, he chose this:

“It was like an epidemic of veneration, which in the course of six or seven years gradually took possession of the whole district.”

Hugo repeats the idea of an “epidemic” when he says that only Javert was exempted from this “contagion.” Madeleine’s tenure, then, is portrayed as positive in the specific details of it (his ability to resolve conflict, his popularity, etc), but there’s also something inherently off, “diseased”, about it. Javert is wrong about many, many things, but he’s not wrong to be suspicious of Madeleine’s identity when he seems vaguely familiar and no one knows (or can find) anything about his background. Is his instinct of assuming Madeleine is somehow an irredeemable criminal who must be found out and punished wrong? Yes, just as it is with everyone he chases. But his discomfort is understandable. His police-dog nature really is detecting “a cat” in Madeleine, and as discussed in previous chapters, cats (as well as wild cats like tigers) represent rebellion (cats describing the people of Paris) and/or criminality (Valjean as a tiger when he leaps over the wall of the bishop’s garden). Again, these traits aren’t necessarily negative. The rebelliousness of the people of Paris, for instance, is what brought down the monarchy the first time. But to Javert, any sign of rebellion, criminality, or other form of rule-breaking condemns one forever, so even if we as the reader are meant to sympathize with “the cat,” Javert is instinctively opposed to that.

Javert is also so bizarre. I’m especially puzzled by this:

“In his leisure moments, which were far from frequent, he read, although he hated books; this caused him to be not wholly illiterate. This could be recognized by some emphasis in his speech.”

I’m not surprised that he hates reading (it has the potential to make one feel empathy for people doing Bad Things), but why does he read when he hates it?

48 notes

·

View notes