#musgum

Text

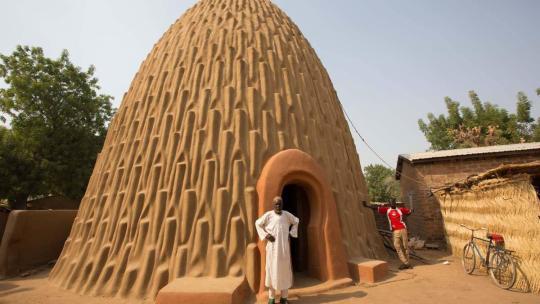

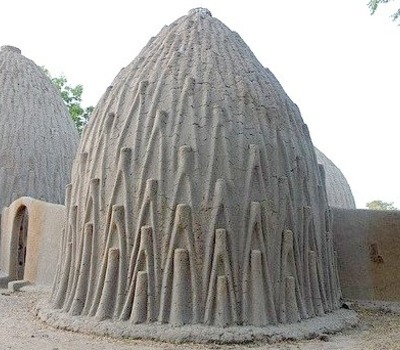

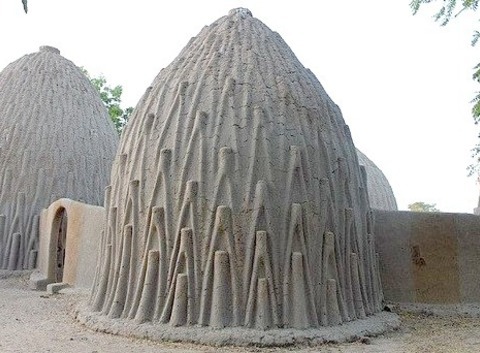

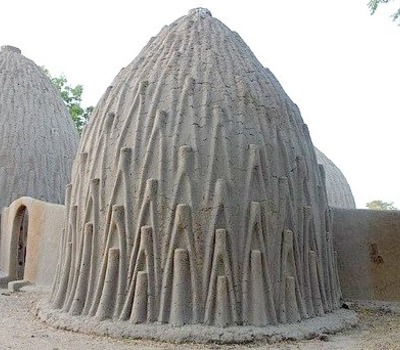

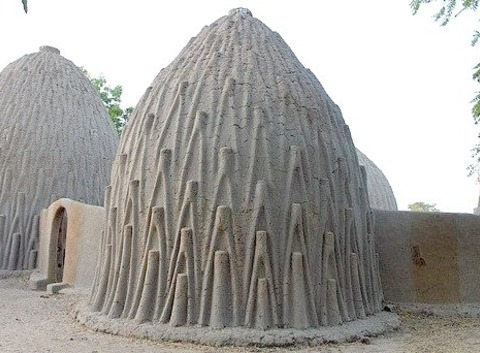

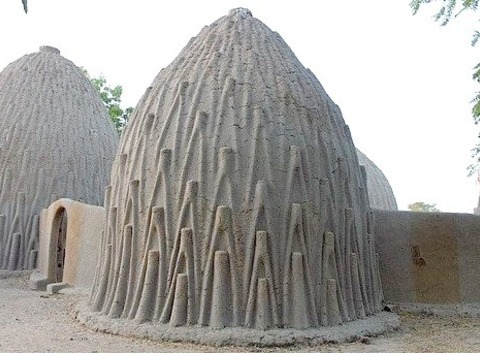

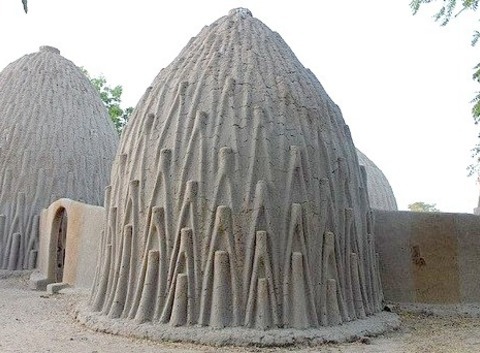

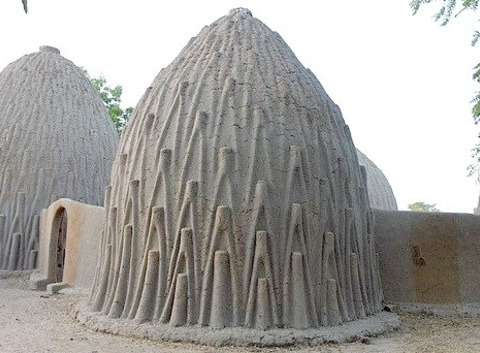

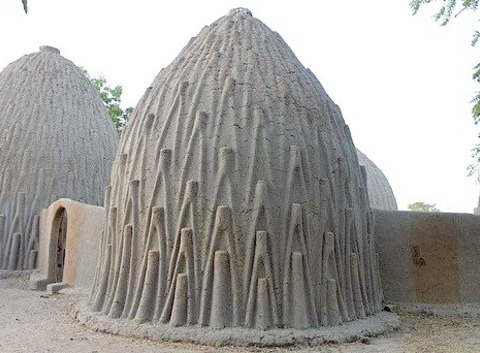

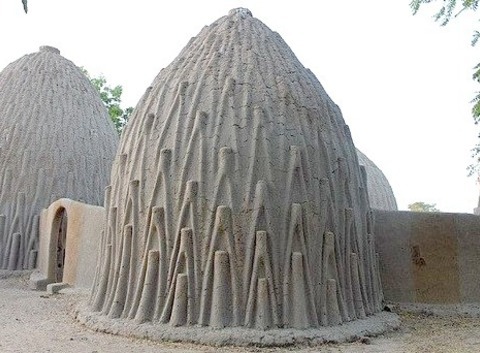

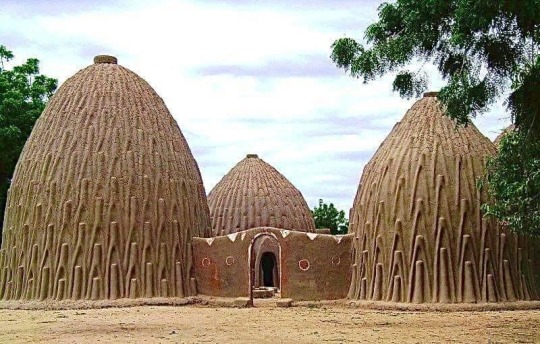

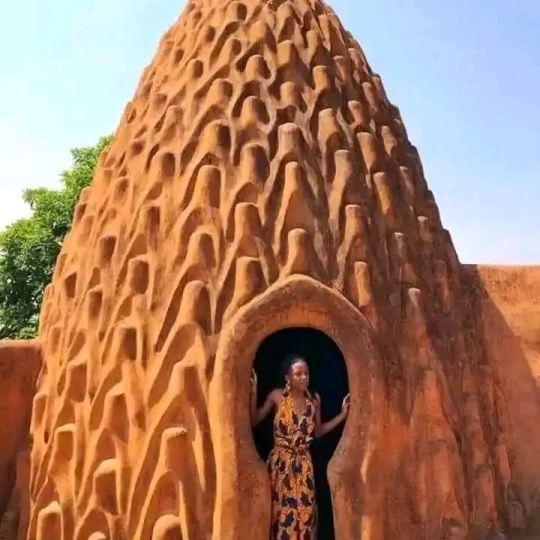

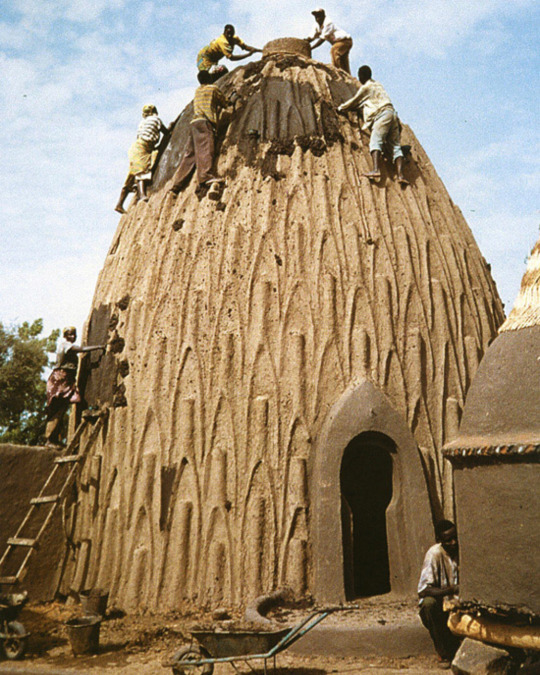

Traditional mud houses in Pouss village, northern Cameroon

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Traditional mud houses in Pouss village, northern Cameroon

1 note

·

View note

Text

Traditional mud houses in Pouss village, northern Cameroon

0 notes

Text

Traditional mud houses in Pouss village, northern Cameroon

0 notes

Photo

Traditional mud houses in Pouss village, northern Cameroon

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Traditional mud houses in Pouss village, northern Cameroon

0 notes

Photo

Traditional mud houses in Pouss village, northern Cameroon

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Traditional mud houses in Pouss village, northern Cameroon

0 notes

Photo

Traditional mud houses in Pouss village, northern Cameroon

0 notes

Photo

Traditional mud houses in Pouss village, northern Cameroon

0 notes

Text

Musgum Mud Huts: Traditional Architecture of the Musgum People in Cameroon

The Musgum mud huts, also known as Musgum dwelling units, stand as a testament to the traditional architectural ingenuity of the Musgum people in the Maga sub-division, Mayo-Danay division, Far North Province of Cameroon. These iconic structures are crafted from sun-dried mud, meticulously compressed to form sturdy walls that are then layered over a framework of lashed reeds. Despite their…

View On WordPress

#African History#African Mud huts#cameroon architecure#Musgum Mud Huts#Musgum People#West African#West African Architecture#West African history

1 note

·

View note

Text

Casas de barro MUSGUM, norte de Camerún 🇨🇲Las viviendas tradicionales de la etnia Musgum son construcciones hechas de barro seco, las cuales tienen varias formas, como chozas altas abovedadas o cónicas.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An exhibition/pavilion review:

Ringing Hollow: A Review of Black Chapel, the 2022 Serpentine Pavilion

Calvin Po

It’s perhaps an unfortunate coincidence that on my way to this year’s Serpentine Pavilion, Black Chapel, designed by Chicago-based artist Theaster Gates, I had a rather more spiritual experience when I passed by a group of street preachers on the square next to Speaker's Corner. With their Union Jack bunting draped all around their assembly, placards with JESUS IS LORD, large banners of the English flag adorned a patriotic lion and names of the all the London boroughs proudly proclaiming LONDON SHALL BE SAVED. Puncturing through even my atheistic, bemused scepticism, the blaring music and odd bursts of song had a patriotic, messianic energy that was electric. By the time I got to the Chapel I came to see, it had simply been upstaged.

Pavilions have often mattered more for the reason they are built, than the actual functions they house. From completing the composition of a Picturesque landscape, to Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion itself becoming a manifesto, the purpose of pavilions often exists beyond the building itself. In the case of the Serpentine Pavilion, it is more about the annual cycle of patronage by the London cultural elite as they pat the “emerging architect” of the year on the back. So I was intrigued when Gates claimed a loftier, more sacred ambition of creating a ‘Chapel’, a “sanctuary for reflection, refuge and conviviality”, for “contemplation and convening”, on top of the usual purpose as a place to sit and buy an expensive coffee.

The pavilion’s imposing 10.7m high cylindrical form, clad in all-black timber has an immediate presence as I approach. Gates claims the form references inspirations as eclectic as “Musgum mud huts of Cameroon, the Kasubi Tombs of Kampala, Uganda [...] the sacred forms of Hungarian round churches and the ring shouts, voodoo circles and roda de capoeira witnessed in the sacred practices of the African diaspora.” Perhaps the subtlety of these references is lost on me, but the Pavilion mostly evokes an industrial structure, like a water tank or gasometer, especially with its external ridges of timber battens and internal ribs of timber and metal composite trusses. Yet despite the grand gesture of an open oculus in the roof, letting light into the inky, voluminous interior, it fails to move me in that transcendental way that even a modest place of worship can.

Is it perhaps the quality of the execution? Serpentine Pavilions are often put together on hasty timescales, with six months from conception to completion. Little details give this away: boards of the decking and cladding not quite lining up, the black-stained timber a bargain basement imitation of yakisugi (Japanese technique of timber charring). Perhaps this can be forgiven of a non-permanent structure: in a nod to sustainability credentials, this year the designers have taken care to ensure the structure is demountable, down to the reusable, precast concrete foundations. But seeing that the Pavilions are almost always auctioned off to recoup the costs and relocated to the grounds of private collectors and galleries, this seems more a convenient commercial expediency, than an environmental one. Perhaps it is difficult to be spiritually moved by a structure that is sold and delivered like a commodity, with little rootedness in its physical and congregational geographies.

Or could it be the atmosphere, a lack of drama? One of Gate’s flourishes, such as his seven silvery ‘Tar Paintings’ that are suspended in the inside walls of the space like abstract icons, are a nod to his father’s trade as a roofer, and Rothko’s chapel in Houston. Yet these self-referential gestures seem lost on the throngs of sun-seeking Londoners taking brief shelter from the heat and wilted grass, with hardly anyone giving them a second glance. Most seemed more interested in the shade than symbolism. For a project that also emphasises “the sonic and the silent”, the acoustic atmosphere of the space I found wanting, perhaps because of the sound that leaks out of the two full-height openings that puncture straight through the volume: its acoustic experience had neither the reverberant, sanctified silence once expects from a chapel, nor the sonic presence that the street preachers managed to carve out of a busy corner of a London with just their vocal chords. Instead, all I heard was the low chatter of visitors going about their own business. The Pavilion is being programmed with “sonic interventions” (read: music performances), and the jury is out on whether or not the Pavilion can serve as a suitable venue for sounds with a more explicit, ceremonial intentionality.

But perhaps the coup de grâce was the decision to relocate a bell from St Laurence, a now-demolished Catholic Church from Chicago’s South Side. Sited next to the entrance, it is to be “used to call, signal and announce performances and activations at the Pavilion throughout the summer.” Gates explains this decision as a way to highlight the “erasure of spaces of convening and spiritual communion in urban communities.” But now mounted on a minimal, rusty steel frame like an objet d’art, I can’t help but feel a cruel irony that a consecrated object that once used to convene a lost community is now used as a performative affectation for the amusement of London’s arts and cultural gentry. This perhaps exemplifies a deeper ethical issue at the heart of the Pavilion’s concept: narratives of collective worship, cherry-picked from across communities and cultures, are sanitised, secularised and aestheticised in a contemporary art wrapper for the tastes of the largely godless culture crowd. The curator’s spiels of a creating “hallowed chamber”, if anything ring hollow.

As I leave Hyde Park, I pass by again the assembly of street preachers, who have now moved on to delivering a sermon. Gates said of his Pavilion, “it is intended to be humble.” Yet I can’t help but but feel how much more these preachers have achieved, with so much less.

#writing#journalism#architecture#architectural writing#architectural criticism#critique#architectural journalism#New Architecture Writers#building#building study#building review#exhibition#exhibition review

1 note

·

View note

Photo

A woman from the Musgum tribe, Cameroon. 🇨🇲🇨🇲🇨🇲🇨🇲🇨🇲 The musgum, an ethnic group in far north province in cameroon, created their homes from compressed sun-dried mud. the tall conical dwellings, in the shape of a shell (artillery), featured geometric raised patterns. A characteristic settlement form is the compound, a cluster of units linked by walls.The domed huts of the musgum people are built in shaped mud, a variant of cob. cob building is the most widely used technique in the world, since no tools are needed – hands, earth and water are enough. https://www.instagram.com/p/CjIBhtmsQWB/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

“maintenance of a musgum

the decorative surface allows for further refinement and individualization. the veins are also contributing to the drainage of rain. the musgum houses require regular maintenance of the coating and the veins allow people to climb atop the building.”

Instagram.com/friendswithclay

88 notes

·

View notes