#proletkult

Text

Poyekhali

More Tumblr banners made by colour shifting Soviet Sci-Fi art. Please enjoy.

#red futurism#retro scifi#retro futurism#soviet sci fi#soviet union#ussr art#ussr#marxism leninism#marxism#scifiart#sci fi#not my art#futurism#space#space race#proletkult#aesthetic

861 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Art must not be concentrated in dead shrines called museums. lt must be spread everywhere – on the streets, in the trams, factories, workshops, and in the workers' homes."

-Vladimir Mayakovsky

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

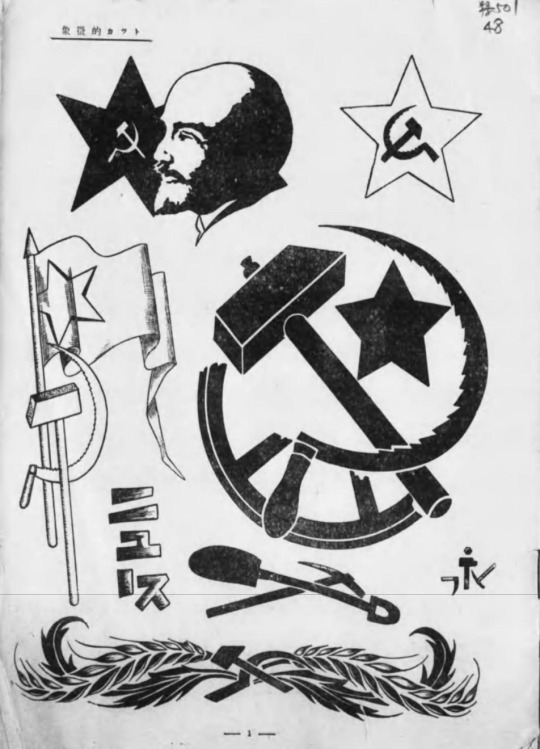

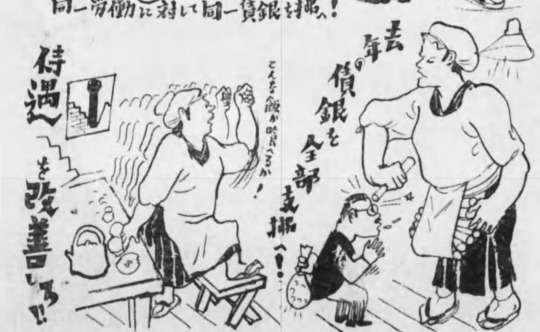

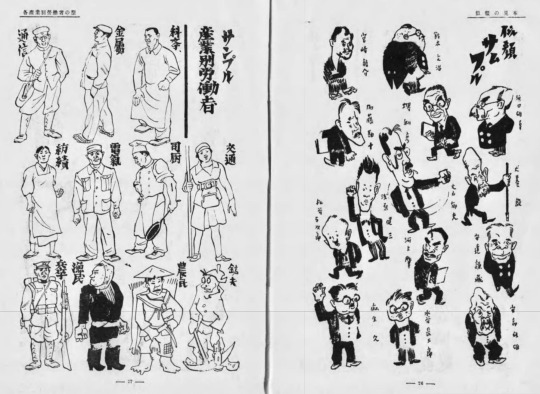

#proletkult#soviet#communist#japanese communist party#1930s#class struggle#japanese graphic design#japanese illustration#industrial action#labor union

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Come in uomo ormai poco vivace viene lasciato in pace anche dai suoi nemici.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Un spécial sur Proletkult et Q comme Qomplot en France

Depuis que la maison d'édition Métaillié a publié Proletkult en France - traduit par Anne Echenoz pour la série "Bibliothèque Italienne" dirigée par Serge Quadruppani - notre roman de 2018 connaît un succès critique considérable.

Le regain d'intérêt pour l'histoire de l'empire tsariste, de l'URSS et de la Russie d'après 1991 joue peut-être un rôle dans cette réception.

De nombreuses critiques de Proletkult sont parues en France ces derniers mois. Nous vous en proposons une sélection ci-dessous. Ensuite, quelques autres nouvelles nous concernant, également en provenance de la francophonie.

Lire, magazine litteraire – Sur une autre planète

Benzine Mag – Proletkult, Wu Ming : la révolution (prolétarienne) n’a pas eu lieu

La Viduité – Proletkult de Wu Ming

RTBF | Entrez sans frapper – Proletkult de Wu Ming, une relecture façon Philip K. Dick de la Révolution russe de 1917

L’écran fantastique – Dans les rayonnages

Actu du Noir – Proletkult

Courrier Picard – La Révolution russe vu depuis la planète rouge

Le Litteraire – Wu Ming, Proletkult

Kimamori – Proletkult, du collectif Wu Ming

Nyctalopes – Proletkult de Wu Ming

Le travail de traduction et de révision de l'édition française - ou plutôt franco-canadienne, la maison d'édition Lux ayant son siège à Montréal - de La Q di Qomplotto de Wu Ming 1 est également terminé.

La très bonne traduction est celle d'Anne Echenoz et Serge Quadruppani. Il sortira début septembre sous le titre Q comme Qomplot.

Pour l'occasion, WM1 se lancera dans une tournée transalpine d'une semaine. Les détails suivront.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My daughter Christina used to say things about destroying all homosexuality. This was well before she decided to take after her father Donald and start destroying all faeries and shouldering up with Nazi cucks.

Anyhow, I've never liked the way she makes a game out of other people's sexual orientation, and that she was cucked all along by the patriarchy explains her desire to toy with people like Katze do with Maus, although it was more interesting when she made a game out of destroying heterosexual impulses rather than sort of trying to promote heterosexuality, tempt and allure with it, etc.

I don't seem to think Proletkult's mission of 'destroy all bourgeois art' was a good idea if you're going to, you know, actually destroy it. But it's a nice agenda if you're leaving Michelangelo's David standing behind in contrapposto.

Bogdanov's death was a strange one.

It'd maybe be nice if there were more art collectives with interesting mission statements these days. Maybe there are plenty and I'm just not exposed to them, or exposing myself enough...

Yes... exposing myself enough...

Exposing... myself...

0 notes

Text

Sokolov Ilya Alekseevich (1890-1968).

Tank factory. 1940s.

Paper, cardboard, pastel.

Origin: collection of the artist's heirs.

Artist, architect. People's Artist of the RSFSR (1964), Corresponding Member of the USSR Academy of Arts (1954). He worked in an icon painting studio, then studied in the studio of A.P. Bolshakov in Moscow (1909–1911) and in the graphic workshop of the Moscow Proletkult (1919-1921) at V.D. Falileeva. Exhibitor of "World of Art" exhibitions, member of AHRR (since 1924). Works by I.A. Sokolov on domestic and industrial themes, landscapes and interiors are distinguished by sonority of color and skillful transmission of light-air environment. In 1951, the artist was awarded the State Prize of the USSR for a series of colored linocuts on the theme of socialist labor (1949).

Nikitskiy

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

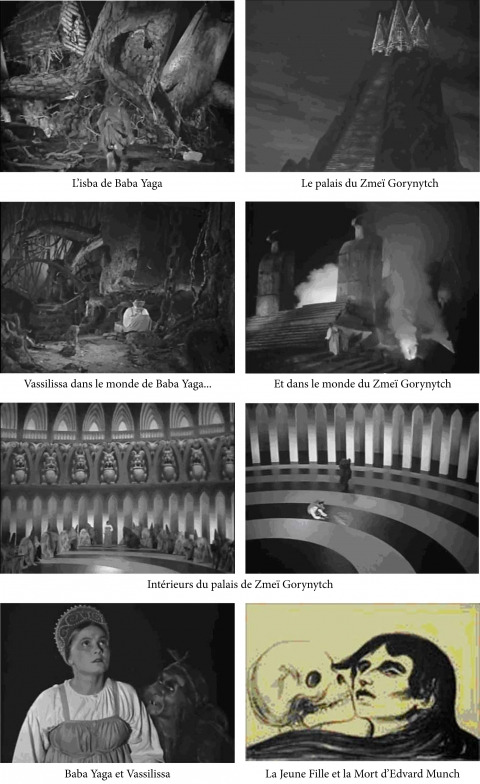

The Yaga journal: Baba Yaga in Soviet movies

And we reach the final article I will translate from the “Yaga journal”: Baba Yaga sur l’écran soviétique (Baba Yaga on the Soviet screen), by Masha Shpolberg!

In 1979, the Soviet studio Soïuzmultfilm produced a three-part cartoon for the Olympic Games that had to happen the following year. The first episode opens with a choir of journalists proclaiming in all the languages of earth: “Micha the bear-cub was just elected Olympic mascot of Moscow”. Baba Yaga listens to this in her cabin, and becomes enraged: “Why him? Why him and not me?”. “Everybody agrees to it!” the journalists say. “And Baba Yaga is against it!” she says, before attacking the television screen with her broom. Throughout these three short episodes, the “Baba Yaga is against it!” cartoon tells the various attempts (and failures) of Baba Yaga and her assistants (Zmeï Gorynytch and Kachtcheï the Immortal) to prevent Micha from reaching the games. The plot relies on the omnipresence of Baba Yaga in the Soviet imagination, and her importance as a symbol of folk-culture. However Baba Yaga did not always have such a status. The witch and her tales were banned by the Soviet Union soon after its creation. Starting in 1918, the year of the creation of the komsomol or “union of Leninist-communist youth”, the Soviet Party reorgaized the educational system: it was decided that fairytales had no place in education. Its rural and pagan roots were problematic for a State which wanted to create an industralized and rationalized world. Galina Kabakova explained that on one side, the fairytale did not carry the values of the new society, and on the other the marvelous and fantastical was considered toxic for the minds of the youth that were to build socialism.

The persecution of the fairytale knew its peak in 1924, when Nadejda Krupskaïa , the companion of Lenine and the president of the Glavpolitprosvet, the Central Comity in charge of Political Education, demanded that all public libraries got rid of the books “with a negative emotional or ideological influence”, as well as the books that “did not conform the new pedagogic approach”. This included the fairytale books of Afanasiev. As the cultural historian Felix J. Oinas explains, in the beginning of the 20s several Soviet critics argued that the folklore was carrying the ideology of the dominant classes, which in turn led the proletarian literary organizations to receive very negatively folktales and fairy tales. A special section of the Proletkult for children even attacked fairy tales based on their “glorification of the tsars and tsarevitchs”, claiming that they were “reinforcing bourgeois ideals” and “causing unhealthy fantasies” in children. When the fairytale re-appeared in the middle of the 30s, it was because the Soviet political culture had decided to re-appropriate the Russian folklore for itself. Just like the Romantic nationalists of the pre-Revolutionnary era, this ideological turn aimed at melting the personal identity in a vaster, collective identity. And what was the best medium to do it? Cinema. Alexander Prokhorov, in his “Brief history of the Soviet cinema for children and teenagers”, explained that the cultural administrators of Staline changed their view on folk-culture, and the fairy tale became a legitimate cinema genre since it helped visualize the spirit of the miraculous reality proclaimed by the Stalinian culture. The end of the NEP, in 1928, also put an end to the importation of foreign movies, freeing the Soviet cinema from all competition - and of all commercial goals.

In 1934, during the first congress of Soviet writers, Samouil Marchak and Maxime Gorki insisted on the importance of childhood literature for the creation of a new Sovietic man, and in 1936 the Sovnarkom, the highest governemental authority, established two new studios out of the ancient Mejrabpomfilm: Soïuzdetfilm, for children movies, and Soïuzmutfilm, for cartoons. It is in this political and institutional context that the young moviemaker Alexandre Ro’ou (in English his name is spelled “Rou”) decided that, for his first film in 1937, he was to adapt a very famous fable, “Wish upon a Pike”. The success of this movie allowed here to adapt a fairytale, more complex on an ideological level: Vassilissa the Beautiful, in 1939. Through this movie he became the “founding father” of the genre of the cinematographic fairytale. It is in this movie that Baba Yaga made her first appearance in cinema, played by a man - Guéorgui Milliar. Throughout the next thirty years, Milliar would play Baba Yaga in three other movies of Ro’ou: in Morozko (1964), in “Fire, Water and Brass Pipes” (1968) and in “The Golden Horns” (1972).

In this article, the author will analyze the evolution of the character of Baba Yaga throughout these four movies - based on the social and political context. While always created by the same movie-maker, and played by the same actor, Baba Yaga is never the same character in these movies. Throughout the years she is slowly “domesticated”: from a macabre and intimidating force of nature, she becomes a vain hag, more superfical than wicked, from a relic of the past, she becomes a modern mascot. By analyzing the narrative and aesthetic choices causing this transformation, the author wants to analyze the allegories of each movie in their historical context.

I) Baba Yaga in the Stalinian era: Vassilissa the Beautiful (1939)

Vassilissa the Beautiful, a movie adaptation of the story “The Princess-Frog”, was conceived as much as an entertainment as a teaching tool. In the version of Ro’ou, Vassilissa is not a princess and Ivanouchka is not an idiot. The two are rather hard-working, intelligent, honest people. The brothers of Ivanouchka oppose the duo by the women their find as wives: an excentric aristocrat, and a gluttonous merchant’s daughter. The entire first part of the movie presents an allegory of the fight of the social classes. The brothers and the wives do nothing while Ivanouchka goes hunting and Vassilissa does the chores, and then they pretend to have done the honest workers job.

Baba Yaga only appears in the second half of the movie, when the wives burn the frog skin of Vassilissa, and the maiden is ravished by Zmeï Gorynytch. A title-card mentions “In the land of the Zmeï, Vassilissa the very beautiful was guarded by Baba Yaga”. Traditionally, the role of kidnapper in Russian fairytales is played by Kachtcheï the Immortal, who doesn’t appear in the movie - but the Zmeï here fills his role as “the rival of the male hero for the hand of the woman, usually a fiancée or a wife, sometimes his mother” and “the male counterpart of Baba Yaga”. So, as much in their home as in the magical land, Ivanouchka and Vassilissa must fight against oppressors that take away their goods and exploit their work. Jack Zipes noted that, according to the marxist reading of the fairytales, Baba Yaga symbolizes “the entire feodal system, where the greed and brutality of aristocracy are responsible for the hard living conditions. The murder of the witch is the symbol of the hatred felt by the peasants against this aristocracy, that hoards and oppresses.” However, in the Vassilissa movie of Ro’ou, Baba Yaga plays a more ambiguous role. Her skinny and nervous figure, the rags she wears, allows her to hide herself in nature. Her hunched back imitates the rocks, the way she spreads her arms and legs imitated tree branches. By fusing with the landscape, she can attack Ivanouchka without ever being seen by him. Often Ro’ou likes to superposition to allow Baba Yaga to appear and disappear suddenly. As a result she seems half-translucid in many scenes, suggesting that she is a force of nature - or even the personification of the forest.

The “magical” part of the movie plays on the contrast between the domain of Baba Yaga (the forest) and the domain of the Zmeï (the mountain). The two realms are heavily inspired by the expressionist cinema of Germany (especially the sets of the Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, in 1920), but couldn’t be further from each other. The world of the Yaga is the one of the dark forest, confusing and threatening, but deeply organic and human. The world of the Zmeï, however, is an industrialized, hyper-sanitized, geometrical world. A post-human world, or one devoid of humanity: a fascist world. Indeed, the historical context of the movie invites an allegorical reading: the Germano-Sovietic Pact was signed the 23rd of August 1939, and the movie was released the 13th of May 1940, one year before the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in june 1941. At the time, while Germany wasn’t an official enemy (and it is hard to imagine that Ro’ou selected this tale with a political purpose in mind). But the movie is a proof of the tension that existed at the time about the entire situation. Baba Yaga, who keeps turning and roaming around Vassilissa, reminds of the painting of occidental paintings, “Death near the Maiden”. It isn’t just the virginity of Russia (aka, the integrity of its frontiers) that are threatened - it is her very life that is at play.

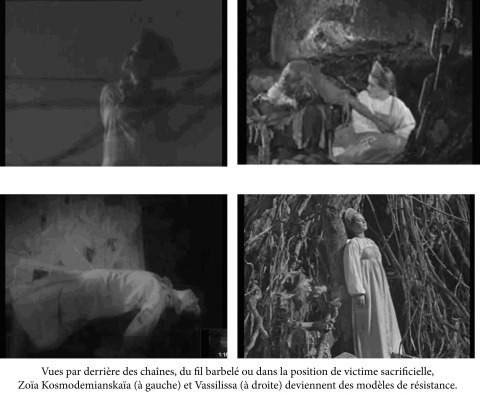

Vassilissa, a girl who is obedient and modest when she is free, becomes proud and rebellious in captivity. She is a model of resistance that anounces the true female heroes of the Second World War in Russia, such as Zoïa Kosmodemianskaïa (made famous by the movie of Leo Arnchtam in 1944). Just like Zoïa, Vassilissa is ready to sacrifice herself for the good of others, and to follow her own principles. When Baba Yaga discovers the hat of Ivanouchka in her isba she aks Vassilissa “Where is he? You say nothing? If you say nothing, I will make you talk. Maybe fire will make you more talkative.” Vassilissa is only saved from torture by the arrival of Zmeï Gorynytch.

The analogy between the monster and the foreign invader is reinforced by the third cinematographic fairytale of Ro’ou, Kachtcheï (Koschei). Filmed in the Altaï and the Tadjikistan in 1944, and released the day of the victory (9th May 1945), the movie tells “how Koschei the Immortal fell onto Russia like a thunder clap in a peaceful sky, burned out houses and our bread, massacred the population and took away thousands of women”. Even if the historical facts cannot allow us to read “Vassilissa” as a simple allegory of the war to come, the images still carry the possibility of an upcoming conflict. We can read it in the presentation of Vassilissa as a resistant-model, as much as in the glorification of the elements of folk-culture (aka, part of Russian culture). The movie is also preceeded by a prologue in which three bards introduce the tale by playing gousli (gusli), a traditional musical instrument. When Ivanouchka goes searching for Vassilissa, the text says “He wandered for a long time throughout his native earth” - even the typography of the title-cards reminds the medieval books. All these elements create throughout this movie a new “nationalist vocabulary”, and so unite a nation threatened by an external force. As Prokhorov explains, “The movies of Ro’ou, just like the kolkhoz musical comedies of Ivan Pyr’ev, were answered an official demand of art inspired by the narodnost (popular spirit/folk spirit)”, an art that “allowed the entire Soviet community to stay in touch with their popular spirit, as the metaphysical source of the communal strength”. The internationalism of the first years of the Soviet Union was slowly breaking down in front of this romantic and deeply essentialist view of the nation.

II) Baba Yaga throughout the Thaw: Morozko (1964), Fire, Water and Brass Pipes (1968) and The Golden Horns (1972)

The period that followed the war was once again difficult for the fairytales, and all those that studied folk-culture. Félix Oinas explains: “After the war, the Russian folklorists knew another series of trials, perhaps the most difficult of them all. The era of the ideological dictatorship of Jdanov, nicknamed Jdanovchtchina, started in 1946, and quickly became an anti-West witch hunt”. Vladimir Propp had just published “The historical roots of the fairy tale”, which was heavily criticize due to containing numerous quotes of Western folklorists, as well as comparativist ideas, not to say cosmopolite ones. In 1947, Soïzudetfilm was re-organized and became the Gorki studo: the studio however did not have any order or demand for children movie. In 1952, the situation led Constantin Simonov and Fedor Parfenov to publish an open letter in the Literaturnaïa gazeta “Let’s resurrect the cinematography for children”. However it was only in 1957, after the death of Staline and the succession of Khrouchtchev, that the minister of culture finally commissioned an augmentation of children movie production. In 1961, the Gork studio was named “Gorki central Studio of cinema for children and the youth”.

When Ro’ou produced Morozko, in 1964, it was in conditions very different and yet paradoxically very similar to the ones in which Vassilissa the Beautiful was produced. The first novelty was the use of color: the second half of the movie takes place in winter, which forces a restrained color palette, even in the makeup and costumes - it is limited to the red and pale blue of the traditional Russian paintings. The appearance of color makes the Baba Yaga younger, as well as more visible in the landscape - but it doesn’t make her more lively. When Ivan discovers the isba in the middle of the forest, and when said isba obeys his order for it to turn towards him, he is sincerely surprised. Baba Yaga gets out of the house yawning, and she asks grumpily “What do you want? Why, unexpected, uncalled, did you dare turn the cabin and wake up the crone?”. It is almost as if everyone in the story was forced in their part of the story against their will. If the Yaga of Vassilissa was jumping from tree-top to tree-top, but the Yaga of Morozko keeps complaining about back problems and she asks Ivanouchka to leave her alone. She only does magic because Ivanouchka forces her to, and her speech is filled with affective diminutives ending in -tchik. Ivanouchka, in the end, doesn’t need to vanquish Baba Yaga, he rather has to convince her to help.

The male equivalent of Baba Yaga, Morozko (Grandfather Forest / General Winter) turns out to be just as harmless as the witch. When he sees Nasten’ka, abandoned by her family to die of cold in the forest, he immediately comes to her help. The role of the two magical characters (Morozko and Baba Yaga) in the life of the young protagonists is limited to the one of a godfather or godmother. The equivalence of these two relationships is highlighted by a sequence which puts in parallel Morozko putting warm clothes on Nasten’ka and Baba Yaga doing the same for Ivanouchka. Another parallel can be found in the way the protagonists call their helpers: Ivanouchka calls Baba Yaga “Yagusia” or “Babulia-yagulia”, while Nastenka calls with affection Morozko “Morozouchka-batiouchka”. From villains, Morozko and Baba Yaga are transformed into helpers, the Donors of the Vladimir Propp’s functions.

The most important consequence of this transformation is the new nature of the “source of Evil”. Evil doesn’t come anymore from what is supernatural, but it rather comes from what is too natural: the flaws of ordinary humans. It is the jealousy of Nasten’ka stepmother and the boasting of Ivanouchka that cause their initial separation and the unbalance that Baba Yaga and Morozko try to remedy to. The qualities preached by Morozko are very close to the ones glorified by “Vassilissa the Beautiful”: hard-work, modesty, and intelligence. What is different is the goal of these virtues: the seriousness and gravity of “Vassilissa the Beautiful” is gone. In Morozko the characters are funny and light-hearted. Ro’ou was trying in “Vassilissa” to animate the visual popular culture, inherited from the lubok and illustrated movies. But in Morozko it all becomes a great show, a smooth surface without any depth. When Ivanouchka leaves his birth-house to go seek his fortune, he passes by a group of young girls that dance and sing when seeing him - these are traditional dances and songs, but the aesthetic is much closer to the one of a technicolor musical than a medieval fantasy.

“Fire, Water and Brass Pipes”, filmed by Ro’ou four years later, in 1968, goes even further in the idea of a show or entertainment. Caracterized by saturated colors and random explosions of music and dance, the movie is aiming at the audiovisual variety show at the cost of the stylistic coherence. This excess alos manifests at the narrative level: while Morozko reunited two distinct fairy tales (Morozko and Ivan-with-the-bear-head), “Fire, Water and Brass Pipes” is a sort of remix of elements taken from numerous myths, cultures and legends (not even all Russian!). The skeleton of the plot is roughly the same: as usual, Kachtcheï kidnaps the beloved of Ivanouchka, and he must undergo a series of trials to get her back. These trials, symbolized by the fire, water and brass pipes of the title, are so many occasions to introduce very different elements, ranging from Greek philosophers to the god Neptune.

In this movie, Ro’ou also modifies the traditional structure of his cinematic fairytales in another way: instead of beginning by the human drama which starts the plot, he begins by the presentation of the magical beings. It is in this “prologue” that we have a full humanization of Baba Yaga: she becomes a mother, and is shown to be able to feel empathy and sorrow. The movie opens with Baba Yaga flying through the sky, rushing to the wedding of her daughter with Koschei the Immortal (also played by Milliar). When she arrives, she is humiliated twice. First, she fails to land properly, implying she can’t move as she used to. Then, nobody recognizes her at the court except for her own daughter and Koschei. This is quite revealing that in this context she introduces herself not as Baba Yaga, but as a relative of the happy couple: she joyfully says (rhyming in Russian), “I am the mother of the bride, Koschei the Immortal is my son-in-law”. This image of Baba Yaga as a mother is not taken out of nowhere: already in the story of Afanassiev called “Baba Yaga and Small-One”, the witch had forty-and-one daughters, that died by her hand. In the movie of Ro’ou, a new importance is given to her maternity as well as to her physical problems (she handles her mortar badly, she falls every time she tries to dance): it all indicates that maybe the life of a witch can be affected by the flow of time. This Baba Yaga is implied to have always been as she is now: she lived a period of youth, and now she is aging. So her life can have a beginning... and an end, like the life of all mortals.

The prologue that presents the maternity of Baba Yaga also has a role in the narrative of the movie: it explains why the Yaga is so willingly helping Vasia (the new name of Ivanouchka). Indeed, when Zmeï Gorynytch offers Koschei a magical apple that makes him young again, he sends away his bride, deeming her too old for him, causing a public humiliation. By helping Vasia defeating Koschei and freeing his beloved (Alionouchka), Baba Yaga is actually avenging her own daughter. She needs Vasia as much as Vasia needs her.

The Golden Horns, made in 1972, thirty-tree years after Vassilissa the Beautiful, was the last movie of Ro’ou that uses the character of the Baba Yaga. After being reduced to a second role in Morozko and “Fire, Water and Brass Pipes”, she finally regains a prominent role. Queen of the forest, she has no rival except for the deer with golden horns - as she complains to a group of hunter, the deer keeps undoing all of her traps and ruining her projects. She doesn’t have back problems anymore, and she is healthy enough to dance and sing. Indeed, throughout the movie she keeps insisting that she is still young. In the beginning of the story she is playing cards with a friend, Duraleï. When he accuses her of cheating and calls her “old hag”, she throws him away from the isba and she says to herself “He dares to call me hag, me, who everybody says has a young soul!”. The Baba Yaga of The Golden Horns isn’t wicked, but she is vain - she is a pretentious old woman that spends hours in front of her mirror. The three young lechïï that serve her constantly flirt with her, and calls her by the diminutive “Babou-yagusen’ka”, and the witch herself flirts with a group of hunter-robbers. Baba Yaga even has a musical number, a song throughout which she turns her hand-mirror into a guitar and sings “I can’t see her enough, Yaga the Fair / Oh my love, me, me me!”.

Beyond the changes brought to the very image of Baba Yaga, Golden Horns is different from the previous movies in two main aspects. The first: the question of the relationship between genders. In Golden Horns, it isn’t a young man who tries to save his beloved from the hands of Baba Yaga or Kachtcheï. It is rather a mother, Evdokia, who tries to save her children. The final conflict is one between two women: one a mother, the other (the Yaga) an old maid. As a result the values of the more are much more conservative in nature. The song of the young girls in the prologue, with the title-cards, compare Russia to a mother. “Always happy, and a bit sad / So is Russia, my mother. / Like the fairytale, intemporal and kind / So is Russia, my mother”. It is this same Russian earth that protects Evdokia in the final battle against Baba Yaga. As the Yaga takes weapons, Evdokia remembers a small bag of soil her neighbor gave her. “Native earth, protect me!” she screams as she throws the soil towards Baba Yaga. These two sequences insist on the sacred nature of the Russian land, “mother” of the people and symbol of maternity itself. The movie implies that it is Evdokia’s maternity that makes her invincible, and that it is the vanity (the “wrong use of her gender”) that dooms Baba Yaga. The absence of a father figure also helps the manifestation of more conservative political messages. It is possible to read Evdokia as a feminist figure: she is independant, and she goes searching for her two daughters without fear. She is intelligent and strong: she isn’t even shocked when she learns she must battle Baba Yaga in a sword-fight. However, she is continuously guided and helped by masculine figure in positions of authority: the Sun, the Wind, and Golden Horns. Golden Horns also offers the perfect example of a theory brought by Evgueni Margolit and summarized by Prokhorov: “Soviet cinema expressed the ideal community of the future as a land of children, where the government filled the role of the strong, order-giving father of the people”. Evdokia, the figure of the mother, is thus treated like a child by the figures of the Father.

In conclusion, this movie offers a new definition of the political action. Like in most fairytales, the movie starts with a transgression: the twin girls of Evdokia, Machen’ka and Dachen’ka, disobey their mother’s instructions and go too far in the forest. What they cannot know is that two wicked spirits trap them, and use them to start a revolution against the Baba Yaga’s tyranny. The movie ends with a tribunal, formed by the small children-wood spirits, alongside the former friend of Baba Yaga, Duraleï. Through a vote, they decide to punish Baba Yaga by banishing her to the swamp. The events of this tale must thus be understood in a wider context, that is seen at the beginning of the movie: this movie represents a shift of powers in the forest, and is the triumph of the humble people, of the simple folks against the monarchy.

Conclusion

In “Vassilissa the Beautiful” (1939), made before the movie, Ro’ou tries for the first time to give a cinematographic shape to the world of the folktales. Taking inspiration from the iconography of the lubok, of the illustrated book, and of the German expressionism, he creates a ciaroscuro universe filled with heavily connotated characters, all either wholly good or wholly evil. Baba Yaga, in this universe, like in the one of fairytales, according to the interpretation of Propp, is a liminal character, the guardian of the frontier between the known and the unknown. Often camouflaging herself in the forest and the rocks that surround the isba, she embodies the dark side of the nature. In a movie whose goal is to enrich the nationalist vocabulary of a land threatened by an external force, Baba Yaga becomes a problematic figure, at the same meant to be “one of us”, since she is part of the Slavic folklore, but also “one of them” since she is unpredictable and hostile.

In the three movies realized by Ro’ou one after the other during the period known as the “Thaw”, the Baba Yaga of Vassilissa is domesticated, becomes a satire, her fangs are removed to make people laugh. While these movies keep feeding from the imagery of Russian nationalism, and keep trying to maintain the authority of the State, they are aimed at being more of an entertainment than a mystical communion with the soul of the people. By giving to Baba Yaga a biography - children, love interests, a passion for clothes and other fashions - these movies remove her from the mythological world, and give her a place in the contemporary world. It is how she becomes, at the time of the Olympic games of 1980, a cult figure, a legitimate rival to Micha the bear-cub for the title of Soviet mascot.

#the yaga journal#baba yaga#russian fairytales#alexander rou#soviet movies#fairytale movies#censorship of fairytales#literary censorship#banning of fairytales#russian folktales#vasilisa the beautiful#the golden horns#morozko#fire water and brass pipes#georgy millyar#baba-yaga

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

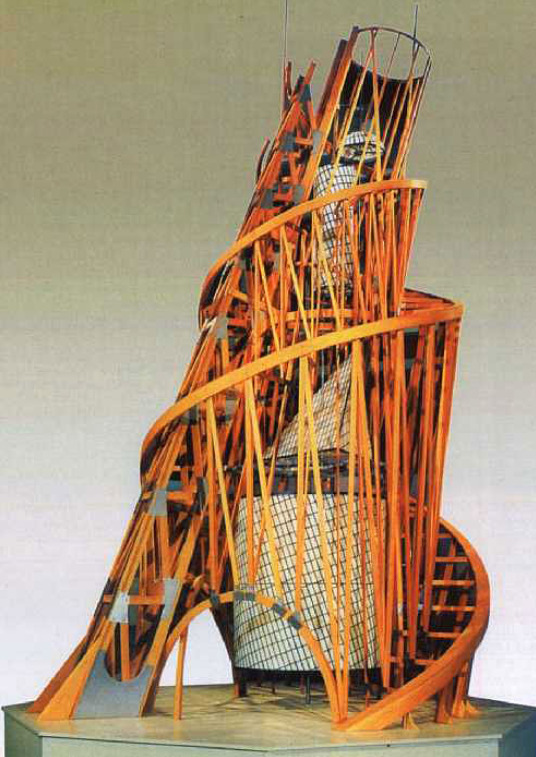

Arseny Morozov House, Viktor Mazyrin

16 Vozdvizhenka St, Moscow

In 1918-1928 the building was occupied by the Proletkult theatre group and staged experimental productions by famous Russian theater and film directors Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Meyerhold.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Long live the woman of the USSR, the builder of socialism."

[Large flag at center] "Women Workers and Women Peasants of the USSR Send Greetings to Working Women of the Whole World." [On the globe] "10 Years of the USSR"

The poster was designed by Proletkult-- Proletarskaia Kultura (Proletarian Culture) an artist cooperative established in 1917. Its formation was supposed to provide the foundations for a new proletarian art, "liberated from bourgeois, pre-Soviet culture."

1927, Il'ia Pavolovich Makarychev

Via Sam Lomb

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Getting rid of proletkult was basically where everything went wrong. It was all downhill from there.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dreams are messages from the deep, this one is called "Tomorrow."

277 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you enjoyed that infodump about art and the avant garde, may I recommend my other barely cogent but passionate rants such as UNOVIS and Proletkult had amazing potential but the left had their avant garde movement obliterated by state controlled 'socialist realism' and Salvator Dali was a fascist sex abuser who got kicked out of the Surrealist movement and should absolutely never ever ever be called a Surrealist let alone be shorthand for the movement itself

I can also recommend my collection of left-wing and republican poster art from the Spanish Civil War as an example of the avant garde and its relation to agitprop, and I also have an amusing if bleak story about Spanish art at the 1937 World Exhibition of the Arts

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#proletkult#agitprop#1930s#senki#soviet#communist#japanese communist party#japanese illustration#japanese graphic design#proletarian#avant garde

1 note

·

View note

Text

The utopias of creation that the Revolution engendered were not “transcended” in Socialist Realism, but were assimilated by it. In the Socialist Realist theory of creativity we find fragments of practically all the aesthetic projects of the revolutionary era. The populism of Soviet art is inconceivable without the contribution of the RAPPists who continued the Proletkult experiment and, afterward, under the aegis of the state, brought the “army of poets” out into the literary arena. The Party-mindedness that comprises the “living soul” of Socialist Realism arose from a synthesis of RAPPist “restraint” with Perevalist “organicity.” Finally, the Stalinist directive regarding professionalism (“expertise”) had strong support in the literature of the LEFist “specialists.” The “ardent revolutionaries” brought their projects to the altar of Socialist Realism. We will not enumerate the victims (historians of Soviet culture have been busy doing this for half a century). Far more important is recognizing the profound naturalness of the genesis of the Socialist Realist aesthetic, its synthetic nature.

Like any battle, the “literary struggle” of the 1920s was waged in the name of victory. Nevertheless, the victory of a utopia means its death, since in victory the modal status of the utopian vision is transcended—the gap between the “real” and the “vital” is removed. The battle of the utopias is thus a battle for self-annihilation. In victory, life-creating conflict and dynamism are transcended. Petrifaction begins.

A new building is constructed over the ruins. Thus revolutionary culture congeals in Socialist Realism—the petrified utopia. From the multitude of real preconditions (the inner crisis of revolutionary culture, the sense of overall crisis in literature as the 1930s neared, the authorities’ recognition of the necessity for the real inclusion of literature in the new political-aesthetic project, the exhaustion of literary institutions’ characteristic means of functioning in revolutionary culture, “readers’ requirements,” and so on), not one can be chosen as defining. The deefning factor was their confluence.

Speaking out in 1920 against the Proletkult ideas of “new culture,” Lenin advanced a counter-program that went beyond the framework of the polemic with Proletkult and had a broader implication: “Not invention of a new proletarian culture, but development of the best examples, traditions, and results of existing culture from the point of view of Marxism’s worldview and of the conditions of life and of the proletariat’s struggle in the era of its dictatorship.” If we transfer this formula from the early 20s to the early 30s, we obtain the strategy of Socialist Realism. And in fact, it was not necessary to “invent” anything: revolutionary culture served as the “existing culture”; the main thing, from “the point of view of the proletariat” in the era of “reconstruction,” was the demand to synthesize “the best examples, traditions, and results” of the preceding revolutionary culture.

—Evgeny Dobrenko, The Aesthetics of Alienation

0 notes

Text

The Antifada/Proletkult interview: A.M. Gittlitz talks with Wu Ming 1 about UFOs, utopia and revolution.

“Just FYI: wu ming are considered reformist shills in italian communist circles.”

Now that’s a blurb! It shouldn’t be relegated in the comments. It should be part of the intro.

Recorded in March 2023, in the middle of our very demanding UFO 78 book tour (80 events in the first six months). Our comrade was tired: too many ers and ehms, too much struggling to find exact terms. Apologies for that. Still, there are some good parts, and Andy was the perfect host.

https://www.patreon.com/posts/proletkult-12-of-80982053

4 notes

·

View notes