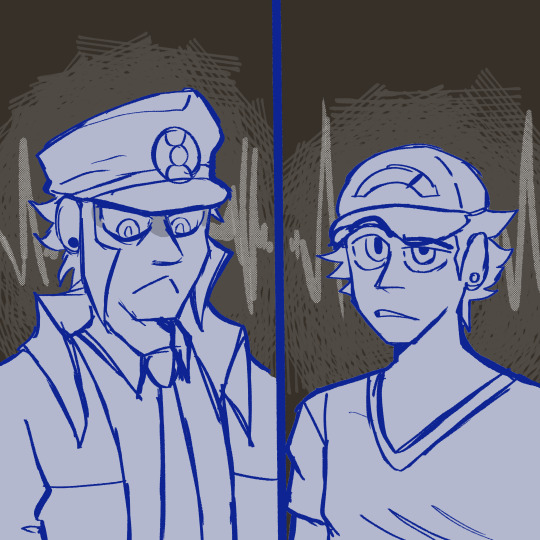

#red and ingo solidarity

Text

the expressionless vs the speechless

They both radiate good vibes

#red and ingo solidarity#red pokemon#pokemon red#ingo#emmet#submas#pokemon#pokemon fanart#pla#pokemon legends ingo#warden ingo#pokémon legends#pokemon legends arceus

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The power of civil mobilisation: How ordinary people stepped-in to help refugees in Northern Greece

By Gabriel Bonis, Research Associate with the Rights in Exile Programme (UK) and former Refugee Caseworker at the British Red Cross in London. Mr. Bonis holds a MA in International Relations from Queen Mary, University of London. His research focuses on international refugee law and human rights. Read the full report in its entirety here.

In June 2017, the UNHCR’s annual Global Trends report stated that war and persecution had driven more people from their homes ‘than ever’ (UNHCR, 2017). The worldwide number of persons affected by forced displacement amounted to a staggering 65.6 million at the end of 2016. From this sum, 22.5 million were refugees, with Syrians representing the largest group (2017). As of November 2017, Syria had produced 5,344,184 refugees (UNHCR, 2017b).

With the escalation of the refugee crisis in 2015, Europe watched 1,015,078 million refugees from countries such as Afghanistan, Eritrea, Iraq and Syria reach its coasts through the Mediterranean Sea that year (UNHCR, 2016). By December 2016, another 362,376 people had arrived in the continent, the vast majority of them via Greece (UNHCR, 2017a). Between April 2011 and May 2017, 952,446 Syrians claimed asylum in Europe (2017b).

As the crisis rapidly unfolded, the Greek government was put under extreme pressure. The authorities struggled to cope with the high amount of sea arrivals, on several occasions failing to provide adequate support to migrants and refugees e.g. proper accommodation, medical assistance and other basic services. Therefore, many independent local organised groups, volunteers, NGOs and INGOs stepped in to partially fill the gap left by the State.

This research focuses on the efforts of non-professional aid actors in Thessaloniki (Greece’s second city) and Idomeni, a village at the border of Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM), the first country of the Balkan route. During seven months (from October 2015 to May 2016), the author followed closely five initiatives running refugee related projects in those areas.

In total, 21 members of these initiatives were interviewed. Of these, 18 were associated with four social centres of different political backgrounds and one was the head of an independently run project. They all underwent long interviews to identify their modus operandi, their motivations in wanting to help refugees, their views on the migration crisis and how other civilians perceived their pro-refugee activities.

Key findings:

Organisational issues

The five initiatives analysed, struggled to cooperate and communicate with other actors, which led to a considerable amount of duplicated work conducted by themselves. Their operations in Thessaloniki (e.g. sorting out of clothes and food) and in Idomeni (e.g. food handouts) were highly inefficient in some periods due to lack of organisation, of experience and of training. However, after acquiring field experience these initiatives showed significant improvement in their performance. Some of them even became relevant emergency response workers in Idomeni.

Cooperation

Political and ideological differences acted as strong deterrents for cooperation between these initiatives and other groups/organisations. Anarchists refused to collaborate with NGOs, who were perceived to be purely financially driven. Other groups also had a negative perception of professional humanitarian organisations, but opted to set aside their ideological differences in order to establish partnerships that benefited refugees.

Mobilisation

The vast majority of the interviewees (74 per cent) considered the pro-refugee mobilisation in Thessaloniki and Idomeni (which involved both direct involvement in projects and donations) as the largest movement of the type experienced by them in the country. One organisation had 400 volunteers working with refugees in the peak of the crisis, for example. 58 per cent of the interviewees perceived their activities as responsible for covering at least some gaps left by Greek and EU authorities in terms of relief to refugees. In this sense, there was a high level of commitment from them to such projects. 68 per cent of the respondents dedicated at least three days of their week to refugee related programmes.

Empathy

Empathy was commonly mentioned by the interviewees as the reason behind their decision to help. Almost 70 per cent of the respondents perceived Greece as a ‘country composed of refugees’. Of that number, 26.3 per cent had refugees in their own families and 10.5 per cent were refugees themselves. Greece’s modern history is deeply intertwined to the refugee theme. In the 1920s, a conflict with Turkey described by Greece as ‘the tragedy of Asia Minor’ resulted in an agreement of exchange of populations between the two countries. Muslim minorities in Greece were compulsorily dispatched to Turkey. Likewise, the Turkish government sent its Greek Orthodox population to Greece. Thus, those minorities became, in a way, refugees.

Anti-refugee rhetoric

Almost half of the interviewees (47 per cent) reported having experienced negative comments due to their involvement with projects for refugees. Most of these episodes occurred online, with the ‘attackers’ questioning why the respondents were not helping Greeks. “Some fascists ask on the internet why [there is] only help for refugees and not for Greeks. It is an stupidity because we also help Greeks. The solidarity kitchen has existed for five years now, way before the refugee crisis started”, said a member of one of the initiatives analysed in this report.

#The power of civil mobilisation: How ordinary people stepped-in to help refugees in Northern Greece#greece#bonis#april#2018

0 notes