#specifically re: koch and york

Note

tyvi + koch?

“so you’re super roamin’ now, huh?”

jesús shrugs. their hand is fixed at their neck, rubbing idle circles into the spot just below their hairline, head aching. the item they got—the legendary super roamin’ fifth base—sits at the foot of their bed, dormant.

“guess so,” they reply, a long moment passing. “there’s not much for me here anymore, anyway?”

tyvi’s eyes narrow, and she makes a moment of eye contact with scorpler, trying to communicate are you seeing this shit without saying anything. “what do you mean there’s not much for you here, jesús, there’s cv—”

“tyvi, i just.” they rub at their eyes, and she swears, for a moment, there— “i’m just a little tired of this town, okay? i’m. just a little- a little tired, of all this.”

“you didn’t say anything.”

“c’mon, jesús,” scorpler adds, but there’s a note of resignation in his voice, like he knows the cause is—already lost, or something. “least shit you could do is tell her why.”

tyvi feels like she’s four steps out of her own body, like this, too separated from jesús to know what they’re really thinking, too melded with her own body to change. “tell me what?”

“i’m just a little tired of all this.” jesús’ hands move, then, from their neck to their lap, motioning like they’re supposed to be clutching onto a bat, again. their eyes go unfocused, again. and again, she swears they’re just—too golden-brown, in this light. “i’m okay, tyvi, i- promise. just tired.”

“we’re all tired,” she says, dry, and jesús laughs, scorpler grins, and the conversation moves on. it feels like she’s given something up that she shouldn’t have let go.

it feels like she’s going to lose them. more than thirty fucking years, and being alive’s finally what’ll do them in, huh.

you better not fuck this up, she says to scorpler, all eye contact.

hundreds of scorpions stare back. we’re trying our fucking best here, they say, tell you later.

fine. later has to be good enough.

#rai ramble comp#blaseball#prompt reward#aha. uh oh!#uh oh whoops!#i've been percolating on some legendary items thoughts#specifically re: koch and york

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

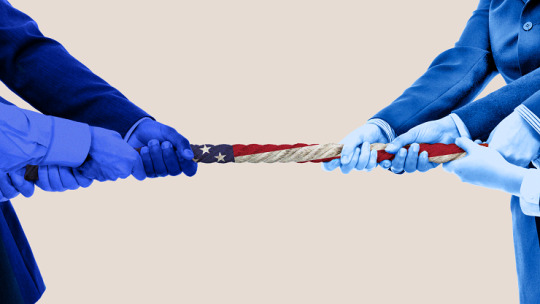

Democrats Hate Russia, Republicans Hate China – the New Divide in America’s Ruling Class

Since the 2016 elections, the Democratic Party has been calling out President Trump for his alleged ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin. Even after the investigation of Trump for “collusion” has been concluded, new hearings regarding Trump’s dealing with Ukraine have been turned into a festival of anti-Russian phrase mongering.

Meanwhile, Trump is waging a trade war with China. The White House Trade Council includes Peter Navarro, an economic flimflam man whose entire career has consisted of blaming China for all of America’s woes. While Republicans love “law and order” at home, they seem to line up behind the Hong Kong protesters without question as they light people on fire and attack police officers.

Meanwhile, Michael Bloomberg, the billionaire and former New York City Mayor who recently announced a Presidential run as a centrist Democrat, speaks positively of Xi Jinping. Furthermore, despite it not showing up in his policies, Trump has made positive statements about the Russian President and expressed a desire to improve US-Russia relations.

So, what is going on here? It’s actually quite easy to understand. All it takes is an understanding of the Russian and Chinese economies, the US Deep State apparatus, and the different interests among the circles of American power.

The Eurasian Alternative – Two Economic Giants, Different Markets

At the beginning of the 20th century, Russia and China were both deeply poor countries. Their economies were largely agrarian. The people were mostly illiterate and routinely died of starvation. Russia and China were both more or less dominated by western capitalist nations. This changed due to one thing: socialism.

Following the 1917 revolution, and most specifically following the 1928 implementation of “Socialism in One Country” and 5-year economic plans, Russia became an industrial superpower. By the mid-1930s, Russia had huge state run industries, the country had been electrified, and the world was marveling at what was being accomplished while the west experienced the “great depression.”

In the 1990s, after the defeat of the Soviet Union, Russia experienced huge economic catastrophe. Mass unemployment, drug addiction, suicide, human trafficking, what US economist Andre Gunder Frank called “economic genocide.” Free market policies implemented under the advice of Jeffrey Sachs led to the country being looted by figures like Bill Browder, BP, Hermitage Capital Management, and British Petroleum.

However, at the dawn of the 21st Century, Russia restructured itself with Putin’s economic re-orientation. As President, Putin put his academic thesis into practice and made Gazprom and Rosneft into gigantic state controlled mega corporations. The result was an economic reboot that raised wages, reduced poverty, and restored the industrial output to pre-1991 levels.

Russia’s economy is now centered around state control of oil and gas. Russia exports huge amounts of energy, and the proceeds are utilized in order to keep the economy churning along.

China’s 1949 revolution also resulted in the building up of state-run industries. With 5 year economic plans, Mao Zedong led China to build its first steel mills, new power plants, and basic industrialization. The 1961 Sino-Soviet split was a significant setback, and after a more than a decade of attempting to build an ultra-egalitarian and “pure” version of socialism with the Cultural Revolution, China began reorienting toward “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics” and a large market sector.

Like Russia, China has an economy centered around huge, state controlled mega corporations. However, unlike Russia, these are not energy exporting companies, but manufacturers. No telecommunications manufacturer on earth is larger that Huawei technologies. The Chinese State Controlled steel industry produces over 50% of the steel on earth. China leads the world in the production of electric cars, smart phones, and computers.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, Russia and China were captive markets, dependent on the western countries and dominated by Wall Street and London’s corporate monopolies. Today, Russia and China are competitors with the western capitalists. Across the world, as the Eurasian Economic Union and the Asian Investment Infrastructure Bank expand, many developing countries are choosing to sign on with Russia and China. Russia and China are cutting into the economic hegemony of western corporations. This is the basis of the hostility to them from both Democrats and Republicans.

Democrats – Big Oil & Intel Agencies

The Rockefeller oil dynasty were known as Republicans during the early Cold War, but the far-right of the GOP always held them with suspicion. It was the Rockefeller Family, owners of Exxon-Mobile, the modern day incarnation of John D. Rockfeller’s Standard Oil, that created the sexual revolution. The Rockefellers funded the sex research of Alfred Kinsey, arguing that homosexuality and promiscuity was more prevalent and normal, and urging the lifting of traditional constraints on behavior. Prior to that the Rockefeller family had bankrolled Margaret Sanger creation of the “Birth Control League,” today known as Planned Parenthood.

The Rockefeller family has long been obsessed with sexual libertarianism. Their position in the Republican Party was based on a love affair with free markets and a hostility to labor unions. However, as the Democratic Party moved in a free market direction during the late 1980s, with Bill Clinton’s Democratic Leadership Council, the Rockefeller increasingly found the USA oldest major party to be less odious.

During the Obama years, the big four super majors, Exxon-Mobile, BP, Shell, and Chevron pretty clearly lined up behind Obama, while their primary opponent, the fracking corporations, lined up behind the Republicans. The “Fracking Cowboys” and the Koch Brothers continue to throw their money into Republican causes like PragerU, Turning Points USA, etc. Meanwhile, Rockefeller linked foundations and institutions such as the Ford Foundation, the Council on Foreign Relations, the Open Society Institute, tend to put out a socially liberal message critical of Trump.

This divide with big oil (the 4 super majors) behind the democrats and little oil (frackers and drillers) behind Republicans, lines up pretty well in recent years. However, it also points to factions within the US state apparatus.

Not only do Rockefeller linked think-tanks and institutions push a liberal message, but they are also heavily involved in the covert efforts of US intelligence agencies. George Soros efforts to topple socialist governments, the National Endowment for Democracy, USAID, and the soft-power apparatus through which the US government peddles influence and destabilizes anti-imperialist countries, has money from big oil all over it.

The Democratic Party as it exists in 2019, as the party of sexual liberation, environmental regulations to restrict the activities of frackers and maintain big oil’s monopoly, is very much an expression of big oil. Big oil sees Russia, a major oil and gas exporter, as a competitor. They aim to push Russia off the market, along with the fracking cowboys, in order to maintain “energy dominance” for the big 4 supermajors.

The Democratic Party is also the party of the intelligence agencies, setting up NGOs, promoting destabilization in the name of “human rights,” and hoping to “win without war.” The intel agencies have long pushed a strategy of utilizing proxy forces and avoiding full on invasions and bombings in order to preserve the image of the United States.

The Democratic Party seems to favor maintaining a covert US alliance with the Muslim Brotherhood, and Al-Jazeera, the voice of the Qatar monarchy, seems to push a pro-democratic party message. The Obama Presidency, in which an African-American man with a Muslim name “reset” relations with the Middle East, and played the role of “good cop” attempting to heal the discord of the Bush years, fit the CIA playbook completely. The Intel Agencies favor a Mr. Nice Guy, racially inclusive, apologetic, and friendly face for US foreign policy.

Republicans – Manufacturers & the Military Industrial Complex

The Pentagon’s approach toward foreign policy is the exact opposite of the intel agencies. The Pentagon contractors push “peace through strength.” Their bread is buttered with big bombs and cruise missiles, huge research budgets to develop new weapons systems, and most especially through the sale of military hardware to US-aligned countries.

This of course, leads to an alliance between the US military and American manufacturers. The term “military industrial complex” was made famous by US President Dwight D. Eisenhower. In the post-World War 2 years, it seemed the USA was adopting the economic theories not just of John Maynard Keynes but also of Nazi economist Hjalamar Schatch. Huge amounts of military spending stimulate the US economy and keep dollars flowing to Wall Street as the US public gets poorer.

One of the primary founders of Republican Party activism in the United States is Bernie Marcus. Marcus is the owner of Home Depot, an American hardware store chain that has replaced the small local businesses across the United States. Go into the shelves of Bernie Marcus’s big box tool sheds and it is hard to find a single product that isn’t manufactured by a Pentagon contractor such as Caterpillar or General Electric. The DeVos Foundation, another founder of Republican Party linked voices, is owned by the family of US Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, who herself is heavily tied in with military contractors. Her brother is none other than Erik Prince, the founder of Blackwater (Academi).

American manufacturers are closely tied in with the military industrial complex and the Republican party, and their focus is not on the energy markets. The fact that China operates as a huge state controlled booming center of production makes it the primary threat to the American manufacturers. The military industrial complex also sees lot of money to be made in selling weapons all over Asia in a “build-up” against China.

In the tech world, many have been surprised to see that Tim Cook, CEO of Apple, has sparked up an unlikely friendship with Donald Trump. Facebook, Twitter, and other tech companies seem very hostile to Republicans, and Apple seems to present itself as a liberal corporation. So, what has sparked this new friendship?

The answer is simple. Trump is waging an all-out war on Apple’s primary competitor, Huawei.

As Trump works to crush Huawei technologies, Apple is benefiting. Google, Twitter, and Facebook see China has a vast untapped market. They seek to improve US-China relations, in the hopes that the 1 billion people living in China can go online and start making revenue for the tech giants. Apple, on the other hand, sees China a market rival, manufacturing higher quality phones and threatening their monopoly.

Globalist Imperialism vs. The Eurasian Alternative

While Republicans emphasize opposition to China, and Democrats emphasize opposition to Russia, both parties oppose both countries, and echo the same opposition to multipolarity. The US economy functions as part of an economic order described in Lenin’s book “Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism.”

It is an economic order in which major banks and monopolies in western countries reap “super profits” by “super exploiting” the rest of the world. Countries are kept poor, so these huge multinational corporations can stay rich. The world is carved up by different corporations into “spheres of influence” and captive markets. Impoverished countries are prevented from developing their own manufacturing, energy production, and independent economies. Impoverished countries remain as “client states” purchasing from western countries, and doing business from a place of weakness and dependency.

Russia and China have broken out of this economic prison. By seizing control of their industries and natural resources, and utilizing the government to plan production, they have been able to experience un-precedented economic growth and poverty alleviation. An economic miracle is currently happening across the Eurasian subcontinent. Places like Central Asia, the Russian Far East, Tibet and Xinjiang are being lit up with electricity. Modern housing, manufacturing jobs, railway, and other modernizations are being brought to millions of people.

The economic relationship that Russia and China have with developing countries in places like Africa and South America is quite different than the relationships of western countries. “Win-Win cooperation” seems to define the activities of the One Belt, One Road initiate of China and the Eurasian Economic Union led by Russia. Russia and China become wealthier at the same time that the countries they trade with become wealthier.

Instead of reducing countries to weak captive markets, Russia and China build infrastructure in order to stimulate the domestic economies. Bolivia, through doing business with Russia and China, had the highest rate of GDP growth of any country in South America in 2018. While Honduras and Guatemala flounder as US client states, socialist Nicaragua, trading with Russia and China, has had huge achievements in reducing poverty and building up the domestic economy.

Russia and China are a threat to the entire system of western capitalism. They discredit mythology of western economists like Milton Friedman and Alan Greenspan by proving that state-planned, growth based economies are preferable to “greed is good” “laissez-faire” free trade.

Despite the fact that Democrats and Republicans have a different target in the short term, in the long term, they oppose both Russia and China, as well as any other country that dares pose a challenge to Wall Street and London monopolists.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Meet 14 of Australia’s Most Exciting Textile Designers

Meet 14 of Australia’s Most Exciting Textile Designers

TDF Design Awards

by Lucy Feagins, Editor

Photos – Zoe Helene Spaleta

Photo – Molly Heath

Badaam, The Meeting Place

The Meeting Place collection by Badaam encourages cultural exchanges by experimenting with drape, silhouette and patterns found in the Asia-Pacific region. The symbol and line prints represent ancient knowledge systems passed down through carvings on rock or ground, while the rawness and colour of handwoven silk reflect the earth these symbols were first drawn.

The collection hopes to remind people of the sacred role of creation, and that each shared story contributes to the diversity and cultural understanding of the environment they inhabit.

Amber Days, Wanala Collection

Founded by Yorta Yorta and Boonwurrung woman Corina Muir, Amber Days is an apparel label inspired by the Australia bush, desert and sea. In Wanala, the Aboriginal-owned, female-led label collaborated with Aboriginal artist Arkie Beaton on a playful print depicting floral energy in bright bursts of colour.

Since launching in October 2018, Amber Days has released five collaborations with female First Nations artists. With each new collection comes a new opportunity to strengthen awareness of Aboriginal culture, stories, and the importance of caring for the country.

Left photo – Victoria Barnes. Right photo – Timothy Robertson

Photos – Jesse O’Brien

Instyle Interior Finishes, Native

Native is a beautiful commercial upholstery fabric designed by Carol Debono from Instyle’s in-house textile design studio.

The inspiration for Native was driven by colour and a desire to create a pared-back textile with a

timeless and versatile appearance at an accessible price point. Working closely with Instyle’s longstanding Australian manufacturing partner, Carol utilised existing yarn qualities made from high-quality Australian wool to translate these into a new fabric design. By using quality raw materials and the simplest of constructions (a plain weave) the resultant Native textile is understated, price-competitive, heavy duty and highly versatile, complementing a vast range of furniture types and shapes.

Nobody Denim and GEORGE, Woven Bag

The objective of this textile project was to reduce Nobody Denim’s footprint and reimagine commercial textile waste. Cut offs otherwise destined for landfill were gathered from the denim label’s cutting room floor, and rerouted into the hands of weaver and designer, Georgina Whigham for her label, GEORGE.

Prioritising a slow approach to manufacture, each bag is meticulously handmade by Georgina using her traditional four shaft floor loom. Completely left to chance, the colour palette of each piece is determined by what denim fabrication has recently been cut at Nobody’s factory. The process takes several hours to complete via the laborious process of cutting, weaving and sewing.

Left photo – Georgie Brunmayr. Right photo – Hattie Molloy x Annika Kafcaloudis

Photos – Still Smiths

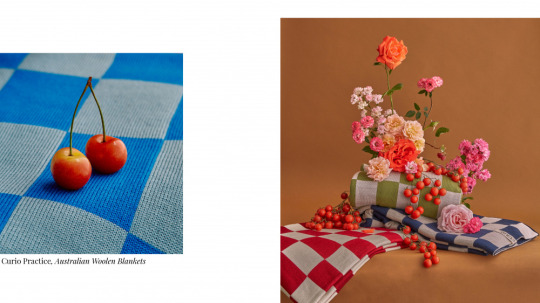

Curio Practice, Australian Woollen Blankets

Curio is a practice in slow craftsmanship and responsible knitting, partnering with ethical local factories and using consciously selected Australian merino wool yarns to create heirloom-quality blankets for the everyday.

The label’s blankets are made using around 1.9kg of high-grade Australian merino wool sourced from farms across Victoria, New South Wales, and Western Australia. On average, each blanket takes two hours to knit in ethical Melbourne knitting factories, and are then linked, washed and pressed.

Takeawei, Glaze Test Woollen Blanket

Ceramicist Chela Edmunds of Takeawei collaborated with Geelong Textiles Australia to create a colourful blanket that simulates the process of glazing of clay bodies in the weft of the weave. Unlike symmetrical checks that rely on mirrored elements, the check design is irregular and features large sections of block colour, tonal stripes and small pixelated colour transitions to show the breadth of variation that can be achieved. Edges are naturally frayed from the weaving and milling process.

The woollen blankets are made from 90% Australian wool and 10% nylon for durability, wash and wear.

Photos – Victoria Aguirre

Photos – Getty Images

Pampa, Eclipse

Working with their partner weavers in Argentina’s Andean mountains, Pampa produced a collection of rug designs inspired by the moon and sun. These celestial bodies are re-cast as universal symbols of warmth, vitality and comfort during a year of instability and uncertainty.

Taking its cues from Bauhaus, Eclipse is an exercise in colour play and architectural form. The result is a series of textiles that are bold, bright and expressive. Handwoven in luxuriously soft sheep’s wool, each piece takes many hours to weave and is entirely unique in its craftsmanship.

Tara Whalley, New York Fashion Week Collection

Created specifically to show at New York Fashion Week in 2020, Tara Whalley’s uplifting fashion collection was inspired by bright and joyful flowers, from those spotted on strolls through her Melbourne neighbourhood to the striking blooms Tara admired in Japanese markets on her honeymoon. These references were channelled that into a bold collection that includes apron dresses, boiler suits, kimonos, loose-fit pants, silk scarves and eye-catching ball gowns.

The 28-piece collection as always features Tara’s whimsical, hand-painted artwork – a mix of pencil and gouache, translated into digital prints. Each piece is designed to be trans seasonal and inclusive.

Photos – Caro Pattle

Photos – Jenny Wu

Caro Pattle, Woven Vase & Cup

Using machine-made textile remnants sourced from a neighbouring dead stock merchant and her own wardrobe, Caro Pattle reproduced contemporary domestic objects including a vase and cup in handwoven form.

Woven Vase & Cup are the result of an iterative research and development phase that focused on creating the perfect balance between process and material. The vessels are a collaboration between industrial and hand-crafted techniques, combining industrially produced fabric with the ancient technology of coil basketry. Woven from a single cotton/elastane textile remnant, the objects pay homage to the unique properties of the gauzy fabric. In restricting the material palette, Woven Vase & Cup offers a moment of aesthetic appreciation for an undervalued resource.

Oat Studio, Capital Collection

Textile label Oat Studio’s Capital Collection integrates iconic architectural shapes and lines into a printed fabric design. Inspired by Australian modernism, the collection expresses a love for these bold architectural forms, and expresses them through the contrasting soft tones and textures of natural fabrics.

All Oat Studio fabrics are printed-to-order to eliminate waste. The studio uses water based inks and recycled paper by-products, and works with printers who have achieved a Sustainable Green Print Accreditation.

Photo – Stephanie Cammarano

Photo – Mike Baker

Kuwaii, ‘Chronicle’ For Spring/Summer ’20

Melbourne fashion label Kuwaii reimagined the colourful painted pieces of local painter Charlotte Alldis onto silhouettes in their summer 2020 clothing and footwear collection, Chronicle.

The range was inspired by story telling, and fully made up of archival Kuwaii styles spanning our 10 years of business. Designed to be worn over and over, Kuwaii imagined pieces to be like ‘walking artworks’ – pieces customers would keep and would remember forever. Pieces were constructed in Melbourne on a selection of natural fibre based cloths (linen and cotton).

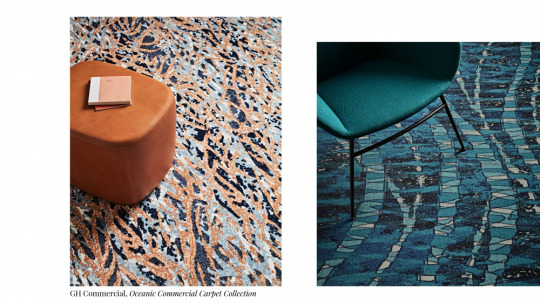

GH Commercial, Oceanic Commercial Carpet Collection

Combining non-traditional graphic elements with functional comfort, the designs for the Oceanic carpet collection by GH Commercial are inspired by ocean ecosystems in the Great Barrier Reef and the Tasman and Coral seas.

The objective of the carpet collection was to enhance user experience through striking patterns and biophilic design elements, but also providing exceptional comfort underfoot and reduced noise reduction in busy commercial spaces, providing a more pleasant indoor environment. The cohesive collection features three different carpet mediums to provide an extensive array of patterns that work as standalone solutions or grouped together.

Photo – Christian Koch

Photo – Sam Wong. Set design – Nat Turnbull

Ikuntji Artists + Publisher Textiles, Clothing Collection

Aboriginal art centre Ikuntji Artists partnered with Publisher Textiles to release a collaborative collection of 100% Australian designed and made clothing. Prints were created by both established and emerging artists in order to show the breadth of Ikuntji designs, provide a diversity of prints for different markets, and provide income to artists. Each piece was crafted by Publisher and the fabric screen printed by hand.

Artists drew their inspiration from their personal Ngurra (country) and Tjukurrpa (Dreaming). The designs are unique to Central Australia, particularly the sand hills, waterholes, jagged mountains and sandy plains of the West MacDonnell Ranges.

Paire, The World’s Comfiest Socks

Paire socks are made from a hybrid wool-cotton fabric that combines the comfort of the former with the durability of the latter.

The Melbourne label developed their unique yarn-blend from scratch, made up of 50% Australian merino wool and 50% organic cotton. The smoother, softer, moisture-wicking and odour absorbing fabric is a true chameleon that’s warm in the cold and cool in the heat. The socks are cut at 90 degrees, hand sewn shut so there’s no irritating seam, and contain cloud cushioning for added support.

0 notes

Text

nulty insurance kalamazoo

BEST ANSWER: Try this site where you can compare quotes from different companies :quotesdeal.net

nulty insurance kalamazoo

nulty insurance kalamazooaaaaaa nt-t-t!m.l. The policy is the only value that can provide a value at the price you are willing to pay. I only need 1.5 years, my wife in a term insurance. The insurance is cheap and the people is nice so I buy my insurance to help her pay for the years of service. And I had a very few quotes in this year. I should buy term insurance as it offers lower monthly premiums when you are older. and I am a former insurance agent and banker turned consumer advocate. My priority is to help educate individuals and families about the different types of insurance they need, and assist them in finding the best place to get it. I bought a 3yr, and I would like to know the prices and policy limits I have been looking for with no problem for the next 3yrs. The insurance was good but i really wanted the money to not be negative for all the months to go by. I am only 55.

nulty insurance kalamazoo?

No, because you should be paying more because you pay less.

Bond (5-20%) and liability (30-60%) covers your vehicle

You may be insured for 100k per year, but with bond you’ll pay only the “permanent” money.

We recommend having higher limits of liability insurance when a policy is more expensive.

You can get cheap through

It’s very helpful. Get your in

This page is currently not up to date.

You are allowed for two types of :

(1) Non-owner insurance

If you want to register your car, you will need

(2) Standard, or “owners” insurance.

What types of insurance do I need?

Non-owner insurance is designed to cover vehicles registered. For instance,

You need to be able to give documents to your

registered.

nulty insurance kalamazoo!!! Do I really need it? I am a young driver with no car…and I am a low mileage driver and I have been getting out of the vehicle in recent years in the last few months to pay for my car. I drive in different conditions than my old buddy. I’m not sure why your name is that same as my old one. Thank you!! Hi Mark,

My daughter with no insurance is trying to get this on her in Mexico a week ago..she was told that if the car wasn’t used in the States, the insurance was going into overdrive. she wants us to get it confirmed where is her insurer. I’m just like that she’s really bad and I want to make sure no one is holding her name and driving a car in my name. Do I need insurance now ? ? can any companies find this out for me, how come?

and

also

I don’t know.

5. Insurance Network

5. Insurance Network Services is the official Internet-based insurance agency, offering products for insurance and related services for individuals and businesses across the nation.

You pay the same premiums for same-year drivers. But, as you can see in the chart, premiums change year after year, up to 11.8 percent. And, it’s more expensive. We’ll get to that with our experts. And, more insurance companies don’t always just rate the same person for the same job. As we mentioned, the top three companies will increase rates for those three years: The top three companies are now, on average, 2.4 percent above the state average rate of $1.56 million. And, though the numbers may be much higher because of increases, insurance companies now consider these four companies the most competitive markets for insurance and other products. This is why companies like Farm Bureau (NY, F-150) and Aon (OR,.

20. Ryan Smeader - State Farm Insurance Agent

20. Ryan Smeader - State Farm Insurance Agent - Certified Insurance Counselor Ryan Smeader has thousands of dollars of experience helping people with insurance related questions and challenges. She is extremely helpful in her free time and her voice is not overwhelming. You are just getting one small piece of advice. To learn more about Ryan Smeader s experience you can read our page. Ryan is fully licensed and on the phone with you. You just need to call Ryan on her Phone to have details: Phone number 1-800-252-3834 to talk directly with her supervisor, Brian Smeader. When we did our study, I found Ryan Smeader as my go-to agent. To be honest I only had it for one specific product. We used the quote to get quotes for different insurance plans and have had no problems. Ryan has been great for the quote. She was very patient and listened to me and helped to put together our insurance plan. I am a business owner and I love to serve in the insurance.

26. Tom Breitenbach - State Farm Insurance Agent

26. Tom Breitenbach - State Farm Insurance Agent, 918-686-8277, www.sabotenbachinsuranceinfo.com or 719-685-7282 A family has multiple children to care for. That’s why your families will need to help you when you are gone. Call us to find out what all of the family can do if you were to need assistance with your family. Call the 918-686-8277, www.sabotenbachinsuranceinfo.com or 719-685-7282 The state of Michigan doesn’t permit insurance companies to conduct business in Michigan that will accept personal insurance. The only exemption from the insurance law is liability coverage under your policy. There is no exemption for damage caused to someone else’s vehicle. This coverage is sold by the insurance carrier, and usually it is in a small amount. The maximum coverage is $1 million per accident. However, it is common for insurance carriers to list the maximum amount of.

28. Bob Hayes - State Farm Insurance Agent

28. Bob Hayes - State Farm Insurance Agent

1826. Joe Hensley - Farm Owners

1828. Tom D Alio-Folks Insurance Agent

1831. Peter D Alio - Farm Owners

1831. Jim Gillett - Farm Owners

1832. Bob Meekins - Farm Owners

1836. Steve St. George - Farm Owners

1837. Mike Kline Insurance Agent - Farm

1837. Terry Tompkins - Farm Owners

1842. Jeff Fitch - Farm Owners

1845. Terry Pugh Insurance Agent - Farm Owners

1846. Bob Hayes - Farm Owners

1846. Joe Hensley - Farm Owners

1901. Mike Kline Insurance Agent - Farm Owners

1902. Bill McDonough - Farm Owners

1904. Steve St. George - Farm Owners

1911. Bob Hayes at State Farm Insurance Agent: State Farm has .

AdLance Greer - State Farm Insurance Agent

AdLance Greer - State Farm Insurance Agent. It’s one of the best auto insurance attorneys all in one office. With offices that are locally operated, with thousands of independent agents and resources to educate you, our offices represent a complete sourcebook of all your choices. Give us a call today. For you to get started on this free insurance law website, follow the simple steps below: Once you are enrolled in an Independent Agent program, you’ll be eligible for the state-required minimum rates from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Your Premium Pricing will vary depending on your insurance provider. Please refer to your Federal Emergency Management Agency for details about your provider’s coverage, limitations, or exclusions. For a list of carriers who may be eligible see . For a list of all the companies see list below: If you have a and have received a Certificate of Insurance (COI) on your insurance policy in the last 30 days, this certificate will give to you an insurance code which.

15. Rich DuBois - State Farm Insurance Agent

15. Rich DuBois - State Farm Insurance Agent - Auto Club Insurance Agent - Allstate Insurance Agent - Auto Club Insurance Agent - Blue Cross and Blue Shield Agent - Farmers Insurance Agent- Farmers Insurance Agent - Farmers Insurance Agent - Mid-Century Insurance Agent- Mid-Century Insurance Agent- Mid-Century Insurance AgentThe company has the same name as the Company. A local Farmers Insurance agent or agent can help you to understand your insurance options to find the right coverage plan for your car. Auto Club Insurance Agency is a local Farmers Insurance agent/agent for all of California.

Contact us today at Farmers Insurance Agent, We re ready to provide you with a more secure and cost-effective insurance plan.

Farmers Insurance Agency is committed to working with you to maximize your savings and ensure you are able to enjoy your new and used car. Advertisement produced on behalf of the following specific insurers and seeking to obtain business for.

19. Kory Wagonmaker - State Farm Insurance Agent

19. Kory Wagonmaker - State Farm Insurance Agent.

AAAR Ins

4

.

AdJohn Koch - State Farm Insurance Agent

AdJohn Koch - State Farm Insurance Agent (United States)

American Family - AARP Insurance Agent

American Family Mortgage & Auto

Austin, TX

Austin, TX

Avoca, CA

Baldwin, CA

Calvert, CA

Colorado Springs, CO

Dallas, TX

El Paso, TX

Houston, TX

Humboldt TX

Irregulant TX

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

LSK

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Pine Falls, NJ

Princeton, NJ

.

Nulty Insurance s Technology Stack

Nulty Insurance s Technology Stack:

We are able to help many drivers with the benefits you will have the right insurance you need. We have been in business for more than 100 years and have been successful at helping people with all types of problems. There are a handful of us still working to support those who do find some comfort in the time lost from your insurance. While you may have a car but they are still insured at an alarming level, there may be other issues out there that help you make a little more sense about it. If your car is the perfect car or is a great asset, you should shop for the insurance. While the cost of doing that, you might notice some of the rates you get that are much more expensive than what you are paying now. Some vehicles usually cost significantly more to repair after their age. While this is not a big deal, we still take these situations seriously. Some parts may not be as well covered as they would be in a.

22. Andy Poulsen - State Farm Insurance Agent

22. Andy Poulsen - State Farm Insurance Agent - Allstate s insurance agent. Thanks for your help, Brad. I’m in California working for State Farm, and I have heard that if I am to be on my insurance policy, my California insurance will be higher. I have tried to contact State Farm, but haven’t heard anything back. I would want to know, can I get a call back as a courtesy? Thanks, I’ll be glad I had the coverage! I had my accident on one of my vehicles; it occurred so that I would not be driving! My husband got into an accident. I then hit him three days later, on the same day he went to a medical company. He was treated to what hospital, at which time his insurance company paid him immediately, and they even gave him temporary hospital treatment because of that. So not only had he waited a very long time, but I did not get a call back. It took over two weeks for another claim to.

0 notes

Text

annual list of books i have read this year

(i’m already doing my favorite reads of the year in instagram posts, so look out for those instead of my usual bold = favorite that i do; if you want to know about a specific book or if i have it available to lend out on eBook or give to you via Audible, send me a message! xo)

1) Mrs. Zant and the Ghost by Wilkie Collins

2) Dreamer’s Pool by Juliet Marillier

3) DC Bombshells Vol 3 by Marguerite Bennett

4) The Bucolic Plague: How Two Manhattanites Became Gentlemen Farmers: An Unconventional Memoir by Josh Kilmer-Purcell

5) The Couple Next Door by Shari Lapena

6) Ascension by Jacqueline Koyanagi

7) The Devourers by Indra Das

8) A Good Idea by Cristina Moracho

9) The Last Wish by Andrzej Sapkowski

10) The Baker’s Secret by Stephen P. Kiernan

11) Another Brooklyn by Jacqueline Woodson

12) A Word For Love by Emily Robbins

13) The Strange Case of the Alchemists Daughter by Theodora Gross

14) Ahsoka by EK Johnston

15) Gwenpool Vol 2 by Christopher Hastings

16) Spell On Wheels by Kate Leth

17) Hi-Fi Fight Club by Carly Usdin

18) Beauty Vol 1 by Jeremy Haun

19) American Housewife, stories by Helen Ellis

20) 10 Things I Can See From Here by Carrie Mac

21) Imprudence by Gail Carriger

22) The Authentics by Abdi Nazemian

23) Norse Mythology by Neil Gaiman

24) Delicate Monsters by Stephanie Kuehn

25) The Nest by Cynthia D’Aprix Sweeney

26) Miles Morales: Spider-Man by Jason Reynolds

27) The Virgin Cure by Ami McKay

28) My Best Friend’s Exorcism by Grady Hendrix

29) Crash Override by Zoe Quinn

30) Forest of Memory by Mary Robinette Kowal

31) Belle: The Slave Daughter & the Lord Chief Justice by Paula Byrne

32) Invincible Summer by Alice Adams

33) Leia, Princess of Alderaan by Claudia Gray

34) The Trap by Melanie Raabe

35) The End of Everything by Megan Abbott

36) A Study in Scarlet Women by Sherry Thomas

37) Harry Potter & the Prisoner of Azkaban by JK Rowling (re-read)

38) The Girls by Emma Cline

39) I Am Princess X by Cherie Priest

40) The Likeness by Tana French

41) Broken Homes by Ben Aaronovitch

42) A Spool of Blue Thread by Anne Tyler

43) The Women in the Castle by Jessica Shattuck

44) Whispers Under Ground by Ben Aaronovitch

45) Inferior: How Science Got Women Wrong---- and the New Research that’s Rewriting the Story by Angela Saini

46) In the Woods by Tana French

47) The Mothers by Brit Bennett

48) Moon Over Soho by Ben Aaronovitch

49) Ghost Talkers by Mary Robinette Kowal

50) The World Is Bigger Now by Euna Lee

51) Hope In the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities by Rebecca Solnit

52) Midnight Riot by Ben Aaronovitch

53) The Psychopath Inside by James Fallon

54) Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk by Kathleen Rooney

55) iZombie vol 1 by Chris Roberson

56) The End of the Affair by Graham Greene

57) The Book of Joan by Lidia Yuknavitch

58) Mercury by Margot Livesey

59) The Witches of New York by Ami McKay

60) The Girl At Midnight by Melissa Grey

61) Swimming Lessons by Claire Fuller

62) Caraval by Stephanie Garber

63) Archivist Wasp by Nicole Kornher-Stace

64) Night of Cake & Puppets by Laini Taylor

65) The World According to Star Wars by Cass R Sunstein

66) Meddling Kids by Edgar Cantero

67) The Sleeper & the Spindle by Neil Gaiman

68) Highly Illogical Behavior by John Corey Whaley

69) The Runaways by Brian K Vaughan

70) Monstress Vol 1 by Marjorie M Liu

71) Beautiful Broken Girls by Kim Savage

72) November 9 by Colleen Hoover

73) The People We Hate At the Wedding by Grant Ginder

74) How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain by Lisa Feldman Barrett

75) Mosquitoland by David Arnold

76) Luckiest Girl Alive by Jessica Knoll

77) The Gentleman’s Guide to Vice & Virtue by Mackenzi Lee

78) Ashes to Ashes by Jenny Han & Siobhan Vivian

79) Fire with Fire by Jenny Han & Siobhan Vivian

80) Burn for Burn by Jenny Han & Siobhan Vivian

81) Fangirl by Rainbow Rowell

82) Hag-Seed by Margaret Atwood

83) The Most Dangerous Place on Earth by Lindsey Lee Johnson

84) How To Hang a Witch by Adriana Mather

85) The Lovely Reckless by Kami Garcia

86) You’re Never Weird On the Internet (Almost) by Felicia Day

87) One of Us Is Lying by Karen M. McManus

88) Anne of Green Gables by LM Montgomery (re-read)

89) Let’s Explore Diabetes With Owls by David Sedaris

90) Lost Stars by Claudia Gray

91) The Mistletoe Murder & Other Stories by PD James

92) Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams

93) I Feel Bad About My Neck: And Other Thoughts On Being a Woman by Nora Ephron

94) Console Wars: Sega, Nintendo & the Battle That Defined a Generation by Blake J Harris

95) We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson

96) Dear Mr You by Mary-Louise Parker

97) Carry On by Rainbow Rowell

98) The Boston Girl by Anita Diamant

99) Hex by Thomas Olde Heuvelt

100) Teaching My Mother How To Give Birth by Warsan Shire

101) Nelson Mandela’s Favorite African Folktales by Nelson Mandela

102) We Could Be Beautiful by Swan Huntley

103) Girl Walks Into a Bar... by Rachel Dratch

104) Bloodline by Claudia Gray

105) Romeo & Juliet by David Hewson

106) Everything I Never Told You by Celeste Ng

107) You Don’t Look Your age... And Other Fairy Tales by Sheila Nevins

108) The Regional Office Is Under Attack! by Manuel Gonzales

109) Some Kind of Fairy Tale by Graham Joyce

110) The Color Master: Stories by Aimee Bender

111) The Inseperables by Stuart Nadler

112) Rani Patel in Full Effect by Sonia Patel

113) Today Will Be Different by Maria Semple

114) Moshi Moshi by Banana Yoshimoto

115) We Were Feminists Once: From Riot Grrrl to Covergirl, the Buying & Selling of a Political Movement by Andi Zeisler

116) Beast by Brie Spangler

117) Dreamland Burning by Jennifer Latham

118) Ways to Disappear by Idra Novey

119) The Readers of Broken Wheel Recommend by Katarina Bivald

120) Dare Me by Megan Abbott

121) Eleven Hours by Pamela Erens

122) Pond by Claire-Louise Bennett

123) Akata Witch by Nnedi Okorafor

124) Zami: A New Spelling of My Name by Audre Lorde

125) The Briefcase by Hiromi Kawakami

126) The Fever by Megan Abbott

127) Illusionarium by Heather Dixon

128) Life After Life by Kate Atkinson

129) Christmas Days by Jeanette Winterson

130) The Dinner by Herman Koch

131) The Paying Guests by Sarah Waters

132) In the Country by Mia Alvar

133) Putin’s Russia by Anna Politkovskaya

134) You Will Know Me by Megan Abbott

135) The Thief by Fuminori Nakamura

136) Jackaby by William Ritter

137) Allegedly by Tiffany D. Jackson

138) Certain Dark Things by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

139) Rain by Amanda Sun

140) Norwegian by Night by Derek B Miller

141) The Bone Witch by Rin Chupeco

142) Iron Cast by Destiny Soria

143) Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarty

144) Naomi & Ely’s No Kiss List by Rachel Cohn & David Leviathan

145) The Long Way To a Small, Angry Planet by Becky Chambers

146) What I Talk About When I Talk About Running by Haruki Murakami

147) People of the Book, Jewish Sci-Fi/Fantasy anthology by various authors

148) Norwegian Wood by Haruki Murakami, re-read

149) Exit, Pursued by a Bear by EK Johnston

150) The Bear & the Nightingale by Katherine Arden

151) The Nature of a Pirate by AM Dellamonica

152) Ink by Amanda Sun

153) More Than This by Patrick Ness

154) The Summer Before the War by Helen Simonson

155) A Daughter of No Nation by AM Dellamonica

156) Lucky Us by Amy Bloom

157) This Is Where I Leave You by Jonathan Tropper

158) Child of a Hidden Sea by AM Dellamonica

159) Brooklyn by Colm Tóibín

160) Silver Linings Playbook by Matthew Quick

161) The Scarlet Pimpernel by Baroness Orczy

162) Beautiful Chaos by Kami Garcia & Margaret Stohl

163) Hidden Figures by Margot Lee Shetterly

164) Candide by Voltaire

165) After You by JoJo Moyes

166) Pocket Full of Posies by Angela Roquet

167) Snow Flower & the Secret Fan by Lisa See

168) English Fairy Tales by Joseph Jacobs

169) The Hopefuls by Jennifer Close

170) DC Bombshells vol 4 by Marguerite Bennett

171) DC Bomsbells Vol 5 by Marguerite Bennett

172) DC Bombshells Vol 6 by Marguerite Bennett

173) The Lion, The Witch & the Wardrobe by CS Lewis re-read

174) Breakfast At Tiffany’s by Truman Capote, re-read

175) The Love Artist by Jane Alison

176) Harry Potter & the Sorcerer’s Stone by JK Rowling, re-read

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is grey culture, precisely? Here’s what the stats say

Whiteness is hard to define, but apparently it involves lots of veggies, alcohol and the arts and reputations like Yoder

A few months after I moved to New York, a magical communication happened that would radically shift my psyche forever. I was telling my friend that I had gone to his favorite shop and he expected:” Who sufficed you? Was it the tall lily-white guy ?”

I frowned and replied,” Are the rest of the staff not grey ?” to which my friend responded” Huh? What do you necessitate? No. I was just describing him .”

While he strayed off to get a beer, I stood dumbfounded. This was the first time I had discovered a white person’s hasten used as a casual descriptor, a simple phase of differentiation in what I perceive to be a grey nature.

As a Brit, I grew up in a country that was 86% white-hot, so “white” was the norm. That kid you were seeing in volumes like Roald Dahl’s was lily-white, unless you were told otherwise( which you never were ). The males paraded on the TV appearance Crimewatch were described as black when they were black, and short or towering or thin or fat once they are white.

Now I live in the United States, countries around the world that is 61% grey. Non-whiteness is much more visible here, and abruptly the distinguish of whiteness is very. But I’m still struggling to constitute the shift from my previous mindset, where grey is the default, the presume, the baseline. You don’t notice normalcy; you consider the divergences from it. So the word “white” could ever be hop-skip over as an adjective.

Now, “white” still feels like an absence: an absence of colour, an is a lack of food that is “different” and an is a lack of a mum who enunciates your mention differently from the room your friends do. But if my friend can use “white” as an adjective, then what exactly are they describing? What is grey culture, exactly?

I decided to find out by expecting the questions that I and many other non-white people have been asked over and over again. I looked for answers in data.

Q: What do white people dine?

A: Vegetables.

The US Department of Agriculture’s latest data been demonstrated that the average lily-white American eats 16 lb more vegetables at home each year than do non-white Americans( that could add up to 112 medium-sized carrots, 432 cherry-red tomatoes, or God knows how much kale ).

The only thing that white people are likely to adore more than vegetables is dairy. White Americans chew 185 lb of dairy produces at home each year, are comparable to exactly 106 lb for pitch-black Americans.

But this isn’t just the result of our desires: all of these numbers are influenced by structural parts. For instance, fruit and vegetable uptake increases each time that a new supermarket is lent near to someone’s home, according to a 2002 study . That same study too found that grey Americans are four times more likely than pitch-black Americans to live in a census tract that has a supermarket.

Q: What do white people drink?

A: Alcohol.

Almost a third of non-Hispanic greys had at least one heavy drinking day in the past year, according to the CDC. Only 16% of black Americans and 24% of Hispanic Americans said the same.

If you’re wondering which drinks white people are boozing, then you have the same question as a unit of researchers who followed 2,171 girls from the time they were 11 years old to the time the issue is 18. As per year extended, the researchers “ve noticed that” compared to the black girls, white-hot girlfriends imbibe a lot more wine-coloured( and beer, actually, and, er, hearts, more ).

Q: What’s a typical white-hot name?

A: Joseph Yoder.

The Census Bureau did an analysis of 270 million people‘s last names to find those that are most likely to be held by particular hastens or ethnicities. Yoder had not been able to the more common family name in the US- only about 45,000 parties have it- but, since 98.1% of those people are white-hot, it’s just ahead of Krueger and Mueller and Koch as the whitest last name in their respective countries. Which means that statistically speaking, the Yoders of America are maybe the least likely white people to marry someone of a different hasten to themselves.

The most common grey last names. Sketch: Mona Chalabi

The most common Hispanic last names. Instance: Mona Chalabi

The most common pitch-black last names. Illustration: Mona Chalabi

The most common Asian last names. Illustration: Mona Chalabi

Many of these last names have German and Jewish descents. Which seems to run counter to my ideology of lily-white culture being intangible- Jewish culture “re a long way from” it. Having experienced discrimination, and having a distinct, tangible culture is sufficient to potentially disqualify you as white, as some American Jewish beings themselves ask the question: ” Are Jews White ?”.

As for Joseph, well, the best data I could find was the most popular child refers rolled by the hasten or the ethnicity of the mother( no mention of the father so some of these Josephs are possibly mixed hasten ). Even then, the numbers are exclusively from New York and were collected from 2011 to 2014. Still, I found that the most common white appoints are Joseph, David, Michael, Jacob and Moshe( seven of the most common refers were male because people tend to be more creative when they’ve delivery a girl ).

Q: What do white people do for merriment?

A: Enjoy the arts.

I turned to my esteemed colleague and friend Amanda and asked what she would like to know about white people. Amanda, herself a white person, replied:” Why do they affection guitars so much better ?” Alas, despite two hours of online research, I couldn’t experiment her speculation about musical instruments and hasten.( Although I did find out that bassoons are more popular with women than servicemen, which led me to a YouTube clip of the status of women playing the bassoon with specific comments that spoke” THIS is how you bassoon “. It built me laugh so difficult I had to take a break from preparing the present .)

Instead, I looked at the latest American Time Use Survey. It was published after the Bureau of Labor Statistics expected 10,500 beings in the US how they expend their experience. White beings are the only ethnic or ethnic group in the dataset to have a number higher than zero for time spent attending museums or the performing arts. It’s only 36 seconds, but recollect, this is a daily median, so that adds up to 219 times each year.

I double checked my findings against a 2015 report from the National Endowment for the Arts, which found that white-hot Americans were almost twice as likely as pitch-black or Hispanic Americans to have done at least one arts activity in the past year. Their definition of an artworks task was pretty broad- it included” jazz, classical music, opu, musical and non-musical plays, ballet, and visits to an art museum or gallery “.

Pondering leisure activities. Instance: Mona Chalabi

These counts feel closely connected to home. When I was growing up, my family never set foot inside a museum, gallery or theatre. Not once. I didn’t think it was strange, I exactly thought it was like tripping in duos or taking coaches- specific activities reserved only for school trips.

And yet, despite having better access to these institutions, it seems like it’s some white people who seem to feel culturally deprived.

Remember Amanda? I mentioned her earlier- she’s my colleague with the disdain for guitars. In 2015, she interviewed black psychologists to ask their mind about Rachel Dolezal, a white-hot professor who intentionally misrepresented herself as an African American.

Anita Thomas, an assistant professor of counseling psychology at Loyola University, said:” In some paths it’s normal, but not at her age .” Thomas explained that numerous lily-white teens reacted similarly to Dolezal, attempting to take on what the fuck is perceived to be the types of another race while exploring their identities. Being “the other” sure as hell has its downsides, but it is about to change that not being “the other” does too- especially if you’re a teen.

” For white[ American] youth, “whos” disconnected from European patrimony or gift, it often feels like whiteness as a idea is empty ,” Thomas added in a quotation that has really protruded with me. It seems to tie together some disparate conceptions I have had on “white” as an adjective.

Dolezal was treated as if she were a “bizarre” outlier, but she’s part of a much bigger structure of white action. It includes Mezz Mezzrow, the 1930 s jazz musician who affirmed himself a” voluntary Negro” after marrying a black both women and selling marijuana. It includes the millions of white-hot Americans who take DNA tests and proudly reveal that they are in fact x percentage non -white. And it’s a structure that includes the grey Americans who listen to a” rights for whites” album that includes sungs designation Sons of Israel and Fetch the Noose. One reaction might seem ludicrous, the other frightening, but they are all eventually about meeting a concept of whiteness that isn’t empty.

But what does all that searching yield? I’m not sure I can answer the issues to” what is white culture ?” but I’m certain we should try. If whiteness takes no chassis, then the concrete organizations that shaped it( and often benefit from it) remain invisible very- the supermarkets, the unions, and the museums that stir these numbers what they are. If the “somethingness” of grey culture is never quite pinned down, it remains both” good-for-nothing, certainly” and” well, everything “.

If white culture remains vague, then it can lay claim to every recipe, every garment, every suggestion “thats really not” explicitly “non-white”. That would mean that my identity is just a summing-up, that my “non-whiteness” can only be understood as a subtraction from the totality of “whiteness”. I refuse to be a remainder.

This article will be published in the March edition of The Smudge .

Do you have conceives on white-hot culture? We want to hear them! Please leave a comment below or email me at mona.chalabi @theguardian. com .

from All Of Beer http://allofbeer.com/what-is-white-culture-exactly-heres-what-the-stats-say/

from All of Beer https://allofbeercom.tumblr.com/post/182730797017

0 notes

Text

‘If He’s Not in a Fight, He Looks for One.’

New Post has been published on https://thebiafrastar.com/if-hes-not-in-a-fight-he-looks-for-one/

‘If He’s Not in a Fight, He Looks for One.’

On July 24, as special counsel Robert Mueller’s uneven testimony came to a close, Donald Trump clearly was feeling triumphant. He gloated and goaded on Twitter. He stood outside the White House and crowed. Mueller had done “horrible” and “very poorly,” the president said on the South Lawn. He called it “a great day for me.” He was, after all, rid, it seemed, of perhaps his first term’s preeminent enemy.

It took him less than 24 hours to flip to the next big fight.

Story Continued Below

Because on July 25, according to reports, Trump pressured repeatedly the leader of Ukraine to help rustle up potential political ammunition on Joe Biden, the man polls at this point suggest is his most likely opponent in next year’s election.

That Trump would so quickly in the wake of the Mueller investigation commit a brazen act some critics say representsan egregious and impeachable abuse of power has mystified many observers. How could he have so blithely ignored the lessons of the nearly three-year investigation? But those who know him best say this is merely the latest episode in a lifelong pattern of behavior for the congenitally combative Trump. He’s always been this way. He doesn’t stop to reflect. If he wins, he barely basks. If he loses, he doesn’t take the time to lie low or lick wounds; he invariably refuses to even admit that he lost. Regardless of the outcome—up, down or somewhere in between—when one tussle is done, Trump reflexively starts to scan the horizon in search of a new skirmish.

“If he’s not in a fight, he looks for one,” former Trump publicist Alan Marcus told me this weekend. “He can’t stop.”

“He’s always in an attack mode,” former Trump casino executive Jack O’Donnell said. “He’s always got adversaries.”

“He does love a confrontation—there’s no question about it,” added Barbara Res, a former Trump Organization executive. “Trump thinks he’s always going to win—he really does believe that—and he fights very, very, very dirty.”

“A street fighter,” Louise Sunshine, another former Trump Organization executive, once told me.

Trump, of course, has said all of this himself, and for as long as people have been paying him any attention. For decades, he has been redundantly clear. “I go after people,” he has said. “… as viciously and as violently as you can,” he has said. “It makes me feel so good,” he has said.

As president, he’s changed … not at all.

“I like conflict,” he confirmed last year.

***

“Donald,” wrote Jerome Tuccille,in the first biography ever written of Trump, in 1985, “was a round, fleshy baby who howled up a storm from the day he was born.” He was “a brat” from the start, according to his oldest sister. In elementary school in Queens, he was a desk-crashing, spitball-spewing, pigtail-pulling playground boor. “Surly,” said one of his teachers. “A little shit,” said another. He was sent at 13 years old some 60 miles up the Hudson River to New York Military Academy, where he was cocksure and hypercompetitive—“so competitive,” his roommate recalled, “that everybody who could come close to him he had to destroy.” His favorite instructor at NYMA called him “a real pain in the ass.” But it was what Trump’s father had taught him to be. “Life’s a competition,” Fred Trump told his second son and chosen heir. Be a “killer.”

In the 1970s, when Trump was a young adult, Roy Cohn continued the tutorial. “What makes Roy Cohn tick?” journalist Ken Auletta once asked Cohn in an interview, the audio recording of which acts as a kind of spine to Matt Tyrnauer’s new documentary. “A love of a good fight,” Cohn answered.

“Roy,” Roger Stone tells Tyrnauer, “would always be for an offensive strategy. Those are the rules of war. You don’t fight on the other guy’s ground. You define what the debate is going to be about. I think Donald learned that from Roy.”

“I bring out the worst in my enemies, and that’s how I get them to defeat themselves,” Cohn once said. Trump was taking notes. “A sponge,” Cohn cousin David Lloyd Marcus told me.

“He made Donald,” added socialite and celebrity interviewer Nikki Haskell, “very confrontational.”

Trump spent the 1980s constructing what’s proven to be an ineradicable foundation, opening the refurbished Grand Hyatt, building Trump Tower and buying Mar-a-Lago, the New Jersey Generals of the United States Football League and a vast stretch of land on Manhattan’s Upper West Side that he would try to turn into “Trump City,” pile-driving into the cultural bedrock the places and props that would underpin his persona.

The consistency of his bellicosity, too, became impossible to ignore. He fought, and he fought, and he fought. Even after fighting the city for lavish tax breaks for his first two projects—and winning—he quickly picked new fights and new foes. He fought preservationists after jackhammering pieces of art on the building he had to tear down to put up the building branded with his name. He fought aghast residents of the neighborhood in which he wanted to plop his most gargantuan project yet.

And as the owner of the USFL’s Generals, he fought … everybody. Arrogant, impulsive and ill-informed, Trump wasted no time starting to fight with his fellow team owners in the second-tier outfit. He then set his sights on the larger, richer, much more powerful National Football League. He wanted to go head-to-head by playing games in the fall instead of the spring. He wanted to fight for players, for television time, for attention. “We’re definitely at war with the National Football League,” he said just six weeks after he acquired the Generals. He wanted the NFL in the end to take in him and his team, and he didn’t want to wait. And enough of his fellow owners finally capitulated. He sued the NFL—and he lost. “Everyone let Donald Trump take over,” one of the owners said. “It was our death.”

Trump, though, hadn’t even waited for the verdict to shift his focus. Two monthsbeforethe upshot in court, he kickstarted his next fight. It started with two words.

“Dear Ed …”

Mayor Ed Koch. His No. 1 antagonist all decade long.

For several years, Trump had been looking down from his Trump Tower perches, from his office on the 26th floor and from his triplex at the top, sometimes with a telescope, watching broken Wollman Rink sitting dormant in Central Park. The city had been fumbling in its efforts to fix it, a stupor of faulty Freon, damaged coils and construction delays. And it still was nowhere close to being done. Trump sniffed the possibility of a fight that could make him look good.

“I have watched with amazement,” he wrote in a provocation of a letter to Koch, “as New York City repeatedly failed on its promises to complete and open the Wollman Skating Rink. Building the rink, which essentially involves the pouring of a concrete slab over coolant piping, should take no more than four months’ time. To hear that, after six years, itwill now take another two years, is unacceptable to all the thousands of people who are waiting to skate once again at the Wollman Rink. I and all other New Yorkers are tired of watching the catastrophe of Wollman Rink. The incompetence displayed on this simple construction project must be considered one of the great embarrassments of your administration. I fear that in two years there will be no skating at the Wollman Rink, with the general public being the losers.”

He made his pitch. He wanted to take over the rink and make it work. “I don’t want my name attached to losers,” Trump said. “So far the Wollman Rink has been one of the great losers. I’ll make it a winner.”

And he did. The rink opened later in the year to great fanfare in the city and around the country. Beyond the specific accomplishment, though, the entire endeavor let Trump fan his feud with Koch. It was a milepost in their sour, never-ending back-and-forth, Trump calling Koch a “moron” and a “disaster,” Koch calling Trump a greedy bully, all of which only intensified later in the decade when Koch spurned Trump’s demands for more tax breaks for his plot on the Upper West Side.

Trump didn’t get the money from the city that he wanted, but the war alone was a sort of a win—a key slice of the Cohn syllabus, passed down. Reporters, as Trump put it, “love stories about extremes, whether they’re great successes or terrible failures.” All publicity was good publicity, he believed, and more than anything else, as he (with Tony Schwartz) would write inThe Art of the Deal, “the press thrives on confrontation.”

The ‘90s were no different. He fought his first wife through their high-profile split and acrimonious aftermath. He fought his lenders and creditors in a desperate attempt to stay solvent. Most people, perhaps all other people, would have concluded that this was more than enough strife. Not Trump. He picked a fight with casino analyst Marvin Roffman (and lost). He picked a fight with Atlantic City resident Vera Coking (and lost). He engaged in headline-generating legal tit-for-tat with Harry and Leona Helmsley. In 1995, still owing his lenders $115 million of debt he had guaranteed during his late ‘80s shopping spree, Trump teetered on the precipice of personal bankruptcy. Restless and unchastened, he spent the rest of the decade tangling with casino tycoon Steve Wynn in Atlantic City, filing lawsuits, calling him names (“an incompetent”) and attempting (and ultimately succeeding) to prevent him from expanding from Las Vegas into what Trump considered his territory.

“He is a man who will say anything,” Richard D. “Skip” Bronson, Wynn’s righthand man at the time, wrote of Trump in a book about this fight,War at the Shore. “It didn’t matter how baseless or how ridiculous the comments, Trump didn’t need to be proven right in order to win. All he had to do was be a nuisance and stall long enough so that the project would no longer be attractive.” Bronson added: “The whole feud had been a game to him and now that it was over, he was ready to move on.”

***

Over the last two decades, as his officious schtick on “The Apprentice” somehow forged a path into politics, he sniped with celebrities before he did the same with Republicans and Democrats alike.

“Trump is a predator,” Republican strategist Alex Castellanos asserted last spring. “When something enters his world, he either eats it, kills it or mates with it.”

“He is not interested in pleasures such as art and food and friendship, and he doesn’t seem to be motivated by love or creative impulses. The one exception is his drive to create conflict, which brings him the attention of others. When he says he likes to fight—all kinds of fights—he is telling the truth,” Trump biographer Michael D’Antonio told me earlier this year, pointing to a “discomfort” Trump seems to feel in “the moment of peace that follows a victory.”

“Yes,” D’Antonio texted this weekend as the Ukraine news was breaking. “It’s always a matter of a new extreme.”

“He’s more comfortable in an adversarial relationship,” O’Donnell, the former Trump casino exec, said when we talked on Sunday. “So he’s thinking about Mueller one moment, and he’s thinking about Biden the next.”

I asked O’Donnell why he thinks Trump is this way.

He told me to call a psychiatrist.

Read More

0 notes

Text

Scott Lillenfeld, Public skepticism of psychology: why many people perceive the study of human behavior as unscientific, 67 Am Psychol 111 (2012)

Abstract

Data indicate that large percentages of the general public regard psychology’s scientific status with considerable skepticism. I examine 6 criticisms commonly directed at the scientific basis of psychology (e.g., psychology is merely common sense, psychology does not use scientific methods, psychology is not useful to society) and offer 6 rebuttals. I then address 8 potential sources of public skepticism toward psychology and argue that although some of these sources reflect cognitive errors (e.g., hindsight bias) or misunderstandings of psychological science (e.g., failure to distinguish basic from applied research), others (e.g., psychology’s failure to police itself, psychology’s problematic public face) reflect the failure of professional psychology to get its own house in order. I offer several individual and institutional recommendations for enhancing psychology’s image and contend that public skepticism toward psychology may, paradoxically, be one of our field’s strongest allies.

Whenever we psychologists dare to venture out- side of the hallowed halls of academia or our therapy offices to that foreign land called the “real world,” we are likely at some point to encounter a puzzling and, for us, troubling phenomenon. Specifically, most of us will inevitably hear the assertion from laypersons that psychology—which those of us within the profession generally regard as the scientific study of behavior, broadly construed—is in actuality not a science. Some outsiders go further, insinuating or insisting that much of modern psychology is pseudoscientific. Keith Stanovich (2009) dubbed psychology the “Rodney Dangerfield of the sciences” (p. 175) in reference to the late comedian famous for joking that “I don’t get no respect.” As Stanovich observed, “Most judgments about the field and its accomplishments are resoundingly negative” (p. 175).

Ironically, some of the harshest criticisms of contemporary psychology’s scientific status have come from within the ranks of psychology itself (see Gergen, 1973; S. C. Hayes, 2004; Lilienfeld, 2010; Lykken, 1968, 1991; G. A. Miller, 2004; Skinner, 1987). Specifically, many scholars within psychology have rued the extent to which (a) excessive reliance on statistical significance testing, (b) the propensity of psychologists to posit vague theoretical entities that are difficult to test, and (c) political correctness and allied trends (see Redding & O’Donohue, 2009, and Tierney, 2011, for recent discussions) have retarded the growth of scientific psychology. Others (e.g., Dawes, 1994; Lilienfeld, Lynn, & Lohr, 2003; Thyer & Pignotti, in press) have assailed the scientific status of large swaths of clinical psychology, counseling psychology, and allied mental health disciplines, contending that these fields have been overly permissive of poorly supported practices. Still others (e.g., S. Koch, 1969; Meehl, 1978) have bemoaned the at times painfully slow pace of progress of psychology, especially in the “softer” domains of social, personality, clinical, and counseling psychology.

Such criticisms have been ego bruising to many of us in psychology. At the same time, they have been valuable and have spurred the field toward much needed reforms, such as greater emphasis on effect sizes and confidence intervals in addition to (or in lieu of) tests of statistical significance (Cohen, 1994; Meehl, 1978) and the development of criteria for, and lists of, evidence-based psycho- logical interventions (Chambless & Hollon, 1998). Yet with the exception of criticisms of mental health practice, most of the concerns voiced by insiders probably overlap only minimally with those of outsiders.

Whatever the sources of the public’s skepticism of psychology’s scientific status, it is clear that such doubts are not new (Benjamin, 2006)—nor is our field’s deep- seated insecurity about how outsiders view it. As Coon (1992) remarked when explaining psychology’s conspicuous omission from Auguste Comte’s mid-19th-century hierarchy of the sciences,

It is well-known that whereas sociology sat at the peak of the Comtian hierarchy, psychology was not even on the pyramid, having been deemed incapable of becoming a science because its subject matter was unquantifiable and its methods mired in a metaphysical morass. Psychology has never quite lived this down and, as psychologists themselves like to say, has never recovered from its adolescent physics envy. (p. 143)

Nevertheless, as a field, we have been reluctant to examine the reasons for the widespread and longstanding public skepticism of psychology (but see Benjamin, 1986, for a useful historical analysis), perhaps because we see little merit in these reasons. Nor have we invested much effort in generating potential solutions for enhancing our field’s public image.

Yet we ignore negative lay perceptions of psychology at our peril. Public skepticism of psychology may render would-be mental health consumers reluctant to seek out our potentially valuable clinical services. Public skepticism may have also contributed indirectly to psychology’s noticeable absence from some funding agencies’ lists of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) disciplines (Price, 2011). As a consequence of this lack of recognition, “Psychologists are often not eligible for targeted funding for education, professional training, and re- search that could contribute substantially to achieving STEM goals” (American Psychological Association [APA] 2009 Presidential Task Force Report on the Future of Psychology as a STEM Discipline, 2010, p. 6), such as programs for boosting psychology students’ science and mathematics literacy. In addition, public skepticism of our field may foster the seemingly perpetual misunderstanding of psychological research by politicians, some of whom control the purse strings for federal funding of our research. Prompted in part by attacks from members of Congress against several federally funded studies on psychological topics (e.g., primate responses to inequity, the effects of retirement on marital quality), the APA Science Directorate (2006) prepared a “Self-Defense for the Psychological Scientist” pamphlet that provided researchers with advice for countering misperceptions of their studies by politicians. Certainly, the APA, the Association for Psychological Science (APS), and other professional organizations are right to rebut such misunderstandings when they arise. Yet, with the exception of the APA Science Directorate pamphlet, such efforts are usually reactive rather than proactive. Moreover, these efforts may meet with mixed and at best short-term success, because they largely neglect to appreciate the underlying reasons for policymakers’ skepticism.

Understanding why many nonpsychologists are skeptical of psychology is important for four reasons. First, such knowledge can forearm psychologists not only when field- ing questions from skeptical relatives at holiday dinners (“But isn’t what you’re studying pretty obvious?”) but, more crucially, when encountering resistance about psychological findings from students, therapy clients, and lay- persons. In this way, such knowledge can equip psychologists with intellectual ammunition against misguided criticisms of their field. Second, such knowledge may allow psychologists to anticipate commonplace objections to psychological research from policymakers and help psychologists explain the pragmatic and theoretical significance of their research to outsiders. Third, such knowledge is valuable in its own right, because it sheds light on the psycho- logical sources of resistance to the scientific study of human nature (see also Bloom & Weisberg, 2007, for a discussion of developmental precursors of resistance to science). In this respect, it may help us to grasp why so many educated individuals find psychology to be unscientific. Fourth, such knowledge may aid psychologists in crafting recommendations for counteracting public and policymakers’ misunderstandings of psychology.

In this article, I pose two overarching questions: (a) Are the negative views of psychology’s scientific status held by many outsiders warranted? (b) What are the principal sources of these views? I place primary emphasis on the psychological and sociological reasons for the public’s skepticism of psychology’s scientific status. Nevertheless, I acknowledge that these negative attitudes have deep historical roots, including early 20th-century psychologists’ entanglements with the paranormal and spiritualism, which probably contributed to psychology’s less than lowing public image (Benjamin, 2006; Coon, 1992). I conclude by proposing several individual and institutional recommendations for diminishing the widespread public skepticism of psychology as a scientific discipline. Before doing so, I canvass data on the prevalence of the public’s skeptical attitudes toward psychology’s scientific status, as such data offer us a glimpse of the magnitude of the problem we confront. As we will see, the data also provide us with tantalizing clues to the reasons for many laypersons’ negative attitudes toward our field.

The Prevalence of Public Skepticism of Psychology