#this is a reference to a post i saw years ago that profoundly affected my life

Text

They call me millions knives cos that's how many knives it takes me to make a sandwich cos I keep putting them in the fuckin sink

#trigun#millions knives#this is a reference to a post i saw years ago that profoundly affected my life#i hope anyone else recognizes it

43K notes

·

View notes

Text

How the Marvel Cinematic Universe Got its Own Pandemic from the Blip

https://ift.tt/2Lng5BE

The Marvel Cinematic Universe has been besieged by supervillains, bombarded by extraterrestrial invaders and—in a deed so dastardly it’s unlikely to be topped—saw half the population of its entire universe dusted away. However, one thing that the continuity will not have to endure is the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, that is not to say that that the MCU won’t be defined by the aftermath of a worldwide-affected tragedy going into its Phase Four slate of films and television shows.

Marvel Studios president Kevin Feige reveals to Variety that parallels to the pandemic are, coincidentally, planned to permeate throughout the MCU by way of “The Blip,” which was the collective term attributed to what occurred after Thanos’s universe-halving Infinity Gauntlet snap in Avengers: Infinity War and Bruce Banner/Hulk’s reversive snap—using Tony Stark’s Nano Gauntlet—in Avengers: Endgame. Feige discusses how Marvel’s pre-pandemic plans to weave the Blip and its fallout throughout the MCU was given a sad bit of serendipity by way of the ongoing real-world tragedy of the pandemic, which is currently closing in on 2 million deaths worldwide.

Feige—who will soon juggle involvement with a mysterious Star Wars movie—explains of the long-gestating post-Blip plans, “[A]bout a year and a half ago, as we were developing all these things—maybe two years ago, I don’t remember—I started to say the Blip, the Thanos event that radically changed everything between Infinity War and Endgame, that gave this global universal galactic experience to people, would only serve us so well, that we need to just keep looking ahead and keep going into new places.” Expressing initial reservations about the MCU possibly repeating itself, Feige goes on to say, “I was wary of it becoming like the Battle of New York, which was the third act of Avengers one, which ended up being referenced as an event kind of constantly, and some times better than others. I was wary of that.”

Read more

TV

WandaVision: Release Date, Trailer, Cast, Story Details, and News

By Joseph Baxter

Movies

Kang the Conqueror: What the New Villain Means for the Marvel Cinematic Universe

By Gavin Jasper

Indeed, the 11-year-spanning, unprecedentedly elaborate buildup to Avengers: Endgame was an investment ultimately rewarded by global audiences with a $2.8 billion take that made it the all-time box office topper. Seemingly, the only place to go after having reached such stratospheric heights is downward; something that made Feige hesitant about setting the next goal line of a universe-encompassing crisis (long-rumored to be an adaptation of iconic Marvel miniseries Secret Wars). Yet, as the pandemic ended up redefining the existence of just about everyone around the real world, its effect would naturally alter the context of Marvel’s post-Blip plans after numerous delays ended up pushing back the entire studio slate. Interestingly, the poetic parallels of the post-Blip MCU with the eventual pandemic were on display in advance back in 2019 with Scott Lang/Ant-Man’s visit to a massive memorial for snap victims in the beginning of Endgame and later that year in Spider-Man: Far from Home, in which expositional dialogue coined the very term, “The Blip,” revealing that Peter Parker (and most of his classmates), as part of the population of restored snap victims, has been retaking his junior year of high school five years later; a small example of the widespread surreal fallout we’ll eventually see throughout Phase Four.

“As we started getting into a global pandemic last March and April and May, we started to go, holy mackerel, the Blip this universal experience—this experience that affected every human on Earth—now has a direct parallel between what people who live in the MCU had encountered, and what all of us in the real world have encountered.” As Feige states, further explaining, “It has been quite interesting, as you will see, in a number of our upcoming projects, the parallels where it will very much seem like people are talking about the COVID pandemic. Within the context of the MCU, they’re talking about the Blip.”

This phenomenon will soon be exemplified when Phase Four of the MCU is ushered in by Disney+ series WandaVision (which premieres Friday, Jan. 15), representing a radical change from the studio’s original plan to have Scarlett Johansson-starring solo feature Black Widow kick things off in May 2020. Yet, the unconventional nature of both would-be Phase Four-launchers in Black Widow (a movie centered on a character who was last seen dead in Endgame) and WandaVision (a reality-altered TV series featuring a character in Vision who was killed in Infinity War and wasn’t restored by the Blip,) seemingly reflects Feige’s ambivalence about the MCU’s next steps, since they don’t seem destined to take any major continuity-defining steps for the overall franchise. In essence, they are safe starters for a Phase that is thus-far defined by uncertain logistical variables.

Nevertheless, Feige is ready to embrace the MCU’s impending accidental pandemic poeticism in a somber, but lemonade-out-of-lemons manner, stating, “[I]t really revitalized that notion [of the Blip] in a way that made it substantive. My nervousness was it just being an event that we reference constantly between things. I wanted it to have more meaning behind it. And if that meant leaving it behind and coming up with new things, that was it. Of course, we always come up with new things as well from the comics, but the real-world connotations are shockingly and somewhat depressingly relevant now between our worlds.”

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

Feige is obviously remaining mum on any further potential pandemic parallels as the MCU moves toward more immediately-imminent 2021 Phase Four offerings such as TV series The Falcon and the Winter Soldier (March 19), Sony-produced Spider-Man cold spinoff movie Morbius (March 19), the aforementioned Black Widow (May 7), TV series Loki (May) and Sony movie sequel Venom: Let There Be Carnage (June 25), with many more to come. Yet, the quasi-pandemic energy of a post-Blip MCU might just forge profoundly personal connections with audiences, especially as the COVID vaccines continue their distribution and the world works on finally putting this chapter in the past.

The post How the Marvel Cinematic Universe Got its Own Pandemic from the Blip appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/39kBu6t

0 notes

Text

ライアーダンス - CHAPTER 2

The trashy VR-AU POST-NDRV3 FIC CONTINUES~ Yippee.

Chapter One < Here

This is POST-NDRV3.

Even if everyone is alive in this, there is still cannon game spoilers mentioned.

Read at your own risk.

(Also typo’s because I don’t proof read shit, I’m a lazy hoe.)

Saihara, with his detective work, slowly but surely began to compile a list of who he saw around, to work out who else didn’t remember. He heard that Kiyo was on the 6th floor, whichever girl was alongside him didn’t remember, but he had no way of knowing about the 12th floor, he couldn’t get up there without the inhabitants agreement, and since neither remembered, it was like the floor was off limits.

It took two days before Saihara managed to get a hold of Kiyo in the large establishment they were kept in. Mostly because Saihara didn’t like to leave his floor, he still lacked the confidence to face everyone, but Amami had helped him..

“My floor? Tsumugi Shirogane.”

Saihara nodded. He’d expected the girl to have some memory issues, she’d been tampered with quite a bit, but it was surprising that Amami was fine, since he’s gone through quite a bit too…

Kaede told him that she met up with most of the girls already, except Tsumugi, Iruma and Kirumi, so it wasn’t any of the others. Saihara could already cross Tsumugi off, and had to put Iruma and Kirumi on the list of possibilities for the 12th floor.

From the boys, he was only missing Kaito, the rest he’d seen or had others confirm they were okay. So that left it down to those three. Iruma, Kaito and Kirumi. But which two?

In the end, Saihara found out from Kiibo, who he overheard talking to a short blonde staff member with the eyepatch.

“Have you seen Iruma? I need her opinion on some of the security measures I can’t bypass.”

“5th floor last I saw her.”

“Thank you.”

So Saihara now had to face the fact Kaito and Kirumi also didn’t remember.

He wasn’t to fussed about the Ultimate Maid, they hadn’t spoken much, and while she was nice to everyone, she’d been executed before he could properly get to know her… and his pre-sim memories of her were still hazy. Not that he didn’t like her or anything, he actually found her presence to have been calming, and she was pretty much adopted as the entire classes mother before Ryoma’s murder… But still… Kaito...

Kaito….

It hurt a lot more.

Saihara had hoped he’d finally be able to make things up with the Astronaut, and fix his mistakes, but now it was like God was punishing him. First Ouma and now Kaito?

Saihara just wanted to apologize to them…

Saihara eventually managed to get in to see Ouma late one evening in secret, with the assistance of Komaeda Nagito, who Saihara was uneasy about. The light haired male had offered to sneak him in to see Ouma, without alerting anyone else… which seemed both preposterous and stupid, but Saihara complied. He tried to bargain for time with Kaito, but apparently he wasn’t in a state for any visitors, and he’d had to be assigned two of the strongest staff members, because he was dangerous, and constantly trying to kill anyone that entered the room…

Saihara had shuddered while being told that.

That wasn’t Kaito… it wasn’t...

Ouma was a mystery to though.

He just didn’t fit the personality he’d expected of someone who’d sign up for murder and death, and it left him to wonder what exactly Despair had written his false reasons to be.

“Ouma.”

Saihara stood awkwardly in the doorway, Ouma was sat in one of the corners of the room this time, looking even smaller than before, if that was possible, backed against the wall.

“You came back…”

“I did.”

“Why?”

“...”

Why indeed.

Saihara had no clue.. If anything he just wanted the chance to sit and properly talk to the Ultimate. Everything that had occurred… he just needed to sort it all out, verbally, with the boy. He just...

“I don't know.” Saihara finally replied, watching Ouma slowly clamber to his feet. He was wobbly on them, and his hands clutched onto the wall to stay upright. Saihara thought he’d fall if he was honest, but he didn’t want to intrude the boy's personal space, when he obviously didn’t want to be around them.

“I.. I still can’t walk properly.” Ouma admitted, indicating for Saihara to come closer, which surprised the detective. It had been a while since the Simulation ended, and most of them were back to being able to function properly, hell, even Ryoma was stable now, and when he’d woken up apparently he was in a state; physically.

Mentally there was still issues with most of them, but physically they’d all gotten over the worst of it already.

Saihara moved forward cautiously holding out an arm, which Ouma wearly took, weight now supported by the Detective.

“I was told it was because my nerves endured intense shock… something to do with... that ... “ Ouma trailed. Saihara knew what he meant.

Of course, being forcefully crushed to… whatever remained of Ouma at that point … by a fucking hydraulic press was bound to affect him, but regardless, the boy clearly wasn’t going to be stopped that easily. Saihara made a small noise of understanding, as Ouma hobbled over to the bed with his support.

“... Saihara.” Ouma mumbled, and Saihara’s heart sunk, at the lack of ‘chan’ at the end. It might have been slightly weird to be referred in such a way, but the lack of cheerful tone behind Ouma’s words had Saihara feel lost.

“Ouma?”

“Will.. will you do me a favour?” Ouma asked, finally letting go of Ouma’s arm, letting the Supreme Leader sit down onto the bed, tucking his knees up instantly. Saihara stood beside him, unsure what he should be doing with himself.

“What can I do for you?” Saihara asked, curiously.

“ Stay .”

“W-what?” Saihara asked, confused.

“Stay.” Ouma asked again, lip trembling slightly, eyes darting between the window and Saihara.

Oh.

Oh .

The boy didn’t like the dark?

“Okay Ouma.” Saihara mumbled, and let himself be tugged down to sit beside Ouma, by weak arms. The two sat there for a moment, neither speaking, before Ouma rested his head on Saihara’s shoulder, arms still securely wrapped under his knees.

“Thanks Saihara-chan.”

If Ouma felt him tense up at his words, nothing was said.

If Saihara felt his entire being freeze at the words, nothing was said.

Nothing was said at all for the rest of the evening.

Saihara felt a tiny bit uncomfortable intruding, but his heart wouldn’t let him leave the boy alone, when he’d spoke with such fear dancing in his eyes. It actually helped calm the detective himself if he was honest, having the gentle breathing of Ouma present in the normally silent darkness he endured every night.

It was... Nice.

Saihara had meant to slip out once Ouma had fallen asleep, but that didn’t happen. He wasn’t sure how he’d ended up falling asleep, but it had happened, and the next time Saihara awoke, it was to the whimpers and sobs of Ouma Kokichi, who was clung around his waist tightly, small form shivering against the detective.

Saihara could feel his heart break further, at the distressed sounds the boy was emitting. Reaching gently, with one hand, he carefully buried it in strands of dark purple hair, combing it gently to try and calm the boy down.

He knew waking people up while they were distressed was dangerous, because they could react violently while unaware of themselves. He’d once accidently punched Naegi in the face that way, having been woken up from a nightmare by the boy only to accidentally flip out. He’s profoundly apologized after, and learnt that it was best he didn’t follow Naegi’s example.

“Shuuichi… ”

Saihara froze. He’d not told Ouma that… he’d only introduced himself though his family name… Saihara caught himself though, noticing he’d stopped moving his hand when Ouma let out another distressed sound, making Saihara restart his actions.

Maybe Ouma subconsciously remembered through dreams?

Who knew…

Anyway, slowly but surely, Ouma’s uneven breathing calmed down, and the sobs and jutters of his shoulders relaxed into quiet snores once again. The detective was grateful it hadn’t ended too badly, but he couldn’t shake the odd feeling he was experiencing. Eventually the detective fell back to sleep once more to, arms wrapping around Ouma protectively as he drifted back into the darkness of his own night terrors.

Komaeda found them the next morning, and even he had the decency not to make any comments, instead leaving the two, clinging to one another as though their lives depended on it, and looking at peace for once which was pleasant to see.

“Nagito?” Hinata asked, and Komaeda simply put a finger to his lips, turning to Hinata in the doorway, shaking a hand to waft the boy back out.

“I believe you can say you found where the little Detective went.” Komaeda whispered, leading Hinata back away from the room, he’d known the entire time where Saihara was but he knew it was crucial for Ouma to have someone he could trust...

And he’d be damned if he left anyone try and say otherwise.

“Is it okay to leave them?”

“Yeah.Trust me, Hajime.”

Because Komaeda Nagito could well and truly admit he had taken a liking to the small Supreme Leader from the moment he’d stepped into Hope’s Peak more than a year ago, and he’d do anything to have him back to normal, even if he had to break a few rules and weave a few lies.

It was around noon when he awoke. Saihara opened his eyes to find Ouma staring up at him, eyes reflecting an emotion Saihara couldn’t place, one he knew he hadn’t seen on the boy before. Despite the Supreme Leader being awake before the Detective, he had made no attempt to move, content with staying wrapped around Saihara, simply watching him sleep.

“Ouma?”

“Good morning Saihara-chan.”

So the chan was back for good it seemed, which had Saihara feel a bit better. It was certainly a step back to Ouma’s normal self… and he was sure the boy knew more than he let on.. But he wasn’t sure how to go about approaching that subject with him yet.

“Ouma… Why were you staring at me?” Saihara asked groggily, raising a hand to wipe his eyes, the other trapped between his and Ouma’s bodies.

“Because Saihara-chan is cute when he’s asleep, obviously.”

Saihara simply gave a spluttering noise.

“See!” Ouma countered, small grin littering his face and Saihara could feel the blush it caused.

If anyone was cute it was Ouma.

Wait what?

“Let’s… let’s get up.” Saihara mumbled, trying to change the topic, and Ouma let go of the detective with a quiet grumble.

“But you’re so warm.. And Saihara-chan feels safe.”

Saihara wasn’t even surprised anymore, at the amount of times this boy was making him speechless.

“C’mon Ouma.” Saihara said once more, climbing to, up stand on his feet, brushing down his clothes he’d slept in, creases obvious against the fabric. He’s need to get changed before he went anywhere else.

Ouma made no attempt to move, snuggling deeping into the covers.

“Ouma?”

“Not getting up.” Ouma mumbled, shutting his eyes.

“Ouma.. You need to get up, you need to eat something.” Saihara mumbled and Ouma shook his head.

“Don’t need to.”

It was like arguing with a child and Saihara couldn’t help the small smile that graced his features at Ouma’s stubbornness. This boy slowly but surely was reminding him of the Ouma he knew.

“Do you want me to bring you something?” Saihara asked and Ouma shook his head the best he could.

“No.. I… No. Feel free to visit again though Saihara-chan.” Ouma whispered, and turned over, as if to tell Saihara to go.

So Saihara did.

He didn’t want to push his luck, after he’d finally managed to earn a sliver of Ouma’s trust.

He headed back to his own room, getting changed into a fresh pair of clothes, before heading down to the ground floor, towards the dining room he’d spent most of his time avoiding, he didn’t feel ready to be around everyone at all once… but now… he felt ready.

Maybe seeing how hard Ouma was trying gave him some confidence… he wasn’t sure, all he knew was that it was time to start facing reality more.

“Saihara!” Yumeno grinned, pointing her toast at the boy who she noticed in the doorway. The rest of the room turned to look to, smiles meeting the detective who stood awkwardly in the doorway. Not everyone was there, but it was nice to see more than one or two of them, together, as though nothing happened... moving on… There was only a few people missing from the group, minus the four Saihara knew not to expect, the only ones missing were Gonta, Kiibo, Iruma and Maki.

It was a little weird to see Kiyo sat talking to Angie, all things considered, but then again he knew those two weren’t exactly normal.. In fact they were quite extraordinary people.

Saihara just raised a hand in greeting, shyly, as Amami shuffled further down the bench, to make space for him, between the Adventurer and the Ultimate Pianist.

“Hiya Saihara! You okay?”

Saihara nodded before sitting down in the space made for him.

“Where were you?” Amami asked quietly and Saihara raised an eyebrow in question.

“What do you mean?”

“Last night. Half the staff went crazy with worry, because you’d vanished, I overheard them.”

“Oh.” Saihara mumbled, he didn’t even know, but he guessed it made sense, since Naegi came to check on him most evenings, and if he was missing, it probably would have raised warning bells… since Saihara barely left his room.

Saihara could feel his face flush, he could hardly turn around and say he'd slept with Ouma, even if that was all that had happened… no way, he couldn't say that… But Amami looked like he had an inkling anyway.

“Oho ?” Amami asked, with a sly smile.

“I erm .. I was with Ouma…”

“I figured as much.”

“Wait.. what?” Saihara kind of expected him to be mad or agitaited or something… considering how close they’d been..

For Ouma to latch onto him and not Amami?

“I’m not mad if that’s what you’re thinking. If anything I’m relieved. I was pretty concerned after the other day, so I’m glad he’s at least let you in. Look after him okay, Saihara?”

Saihara just let out a quiet eep , face flushing at Amami’s words.

“I believe in you.” Amami quietly spoke, as to not alert the others, before getting up from his seat.

“I’ve gotta go, bye everyone.”

And then Amami was gone.

The rest of the day went by smoothly, the group stuck together for most of it, Saihara getting a better tour of the place, which he hadn’t properly explored. It kind of reminded him a bit like that damned Prison School, with all the different rooms, but Saihara tried to ignore that idea, pushing it to the back of his mind.

As the evening drew it, Saihara found himself in the huge library the facility had, with Kaede, a sick feeling in his stomach because the last time he’d been with the girl in such a place…

No.

He wasn’t going to think that way.

“Saihara, are you okay? Is it this place? I wasn’t sure if you’d feel okay here... “ Kaede asked, concerned and Saihara nodded.

“I’m okay.”

It was a lie, and Kaede saw completely through it, but if Saihara didn’t want her to know, she’d go along with it.

“I finding calming, you know? Being around all these books… It's stupid but I like it.”

Saihara just nodded, unable to find the words he wanted.

“Did you get any further investigating? Amami told me you were trying to find out the other students?”

“Yeah, Kirumi, Tsumugi and.. And Kaito.”

Kaede just hummed in reply.

“I see. I thought for sure it would be Iruma, I never see her.”

“Apparently she helps out alongside Kiibo, with trying to recover and reverse the memory issues… I guess that means she’s too busy to be around us…”

“Possibly… I wish I could help out someway to… I feel so useless. Why are we still here anyway? What’s the purpose of waiting here, what are we waiting for?” Kaede pondered, her thoughts voiced without her realising. She stammered.

“I-Ignore that.”

“No, I agree. I think they wanted to keep an eye on us at first, after all there was a possibility we could have been brainwashed to Despair, and they wouldn’t want to let us slip through their fingers. Now I think they just want to keep us all together until we’ve all recovered.”

“That would make sense… maybe.. I just don’t like this pointless waiting around… I want to see the world again, my sister, my family. Do you know in this massive facility there isn’t a piano?” Kaede rambled and Saihara let out a tiny snicker at the end part, which had Kaede giggle to.

“A piano shouldn’t be so hard to find in a post-apocalyptic world, should it?”

Saihara felt himself relaxing more. Kaede’s presence certainly calmed him down when he felt on edge. The girl just had some sort of ability that cheered him up, and it was nice, pleasant, welcome.

The evening drew in further, and eventually the two departed from the Library, Saihara feeling the relief of leaving the room.

“I’m going to head back up to my floor. I’ll see you tomorrow Saihara! Come down and see us more!”

And Kaede was gone.

The walk back to the 11th floor was.. Tiring. The elevator was out of use for the day, due to some maintenance, and Saihara just felt shattered after walking up to the 9th floor. The first floor, and floors 8 to 10 weren’t dorm rooms, instead they housed areas like the library, dining room, and a bunch of office-like areas that the staff used. Saihara was pretty sure the 10th floor was used for their own dorm rooms, but he wasn’t sure because he didn’t have access to get through the doors.

Eventually he made it to his floor, walking through the doors to the floor, and straight into the body of Komaeda Nagito, the taller male catching him, and steadying the two of them, to stop them from falling.

“Ah, Saihara.”

“Ah! Sorry- I wasn’t loo-”

“It’s quite alright, I’m actually quite lucky to run into you, you’re just the person I was looking for.” Komaeda slyly admitted, and Saihara frowned.

“Me? Wh- What is it?”

“”Come with me.” Komaeda smirked, grabbing the Detective's arm, and fair dragging him, despite his quiet protests. The luckster dragged him to Ouma’s door, before letting go of him, and crossing his arms, giving a nod in the direction of the door.

“All yours.” Komaeda spoke and Saihara let out a feebly splutter in protest.

“Wh- What?”

“The rest of the staff don’t want students in each others rooms at night until you’ve all been cleared of suspicion, and especially not with the special cases…I’ll turn a blind eye to this, if you continue to stay with Ouma.”

And then Komaeda left.

It made sense they didn’t want students together at night, because considering nearly half of them had killed someone in the class in the Sim, or been murdered, there was certainly the incentive to commit horrible acts, and when better than at Night when there was less chance of being witnessed…

Regardless though, if Komaeda thought his presence would help Ouma, he was willing to give it a shot. So, with shaky hands he opened to door to the room, cursing himself midway at forgetting to knock.

Ouma was perched on the windowsill once more, legs tucked up to his chest and head down. Despair really had written his character to be this anxious soul? It made sense in a sick way though, that the most eccentric and confident one of them all was made into.. Well this.

“Ouma?”

Ouma’s head snapped up instantly, eyes darting to Saihara, and tiny smile upon the boy's face, despite the obvious tears that gave away that he was crying. Saihara's own face fell at the sight, and before he even knew what his feet were doing, he was over beside the boy, pulling him towards his chest in the most comforting embrace he could muster.

“Ouma… It’s okay.”

“Saihara-chan. W-Why do you keep coming back to someone like me?”

“Idiot, of course I would. We’re friends aren’t we? Even if you don’t remember me.” Saihara mumbled, as he felt Ouma’s fingers clutch onto his uniform, his head buried in Saihara's chest.

“I do.” Was Ouma’s quiet response and Saihara froze.

“Y..You do?”

“Yeah.. Yesterday… but…who knows, I am a liar after all~ Saihara-chan .” Ouma managed to say, raising his head from Saihara’s chest to look up at Saihara, tears still evident on his face, eyes watery, but with the most genuine smile Saihara had ever seen on the Supreme Leader's face, and Saihara could feel himself return it, how could he not? It was infectious.

“Why.. haven’t you told anyone?”

“Komaeda knows, he’s a little shit though.”

“Ouma.. I don’t think you should be referring to the staff that way.” Saihara scolded and Ouma just let out a quiet nishishi.

“Says who? Supreme Leaders don’t take orders from anyone… but I’ll make an exception for my Beloved Saihara-chan..” Ouma taunted and Saihara just shook his head, attempting to conceal the laughter threatening to burst past his lips.

“Will Saihara-chan still stay, even if I remember?” Ouma asked, and Saihara only just managed to catch the flash of fear before it hid itself behind Ouma’s carefully constructed masks… Maybe Despair hadn’t messed with Ouma’s personality at all, because after spending the briefest of time around said ‘personality’ Saihara could conclude the boy in front of him still had the same aspects to him, just hidden better. Was that the kind of person Ouma had always been? Masked insecurities and fears, behind lies and taunts?

Saihara didn’t want to think about it, because it made him feel awful, so he pushed the thought from his mind, and nodded.

“Yeah, I will.”

Ouma let go of Saihara’s jacket and raised his arms in mock victory.

“Yay. You just couldn’t resist me, right? Right?” Ouma asked, his tears had stopped by now, and the boy discreetly wiped them onto his scarf, cheeky tone back in his voice as he spoke. Saihara just scoffed.

“If that’s what you want to believe, Ouma.”

“Ehhh… There’s only room for one liar here Saihara-chan.” Was all Ouma said before attempting to climb down from the windowsill, legs still unsteady below him.

“You okay?” Saihara asked, holding out an arm for the boy to use as support but Ouma shrugged it off, slowly hobbling over to the bed in the room.

“I’m fine, Saihara-chan… gosh.” Ouma pouted childishly before flopping back to lay on his back, staring up at the ceiling, Saihara rolled his eyes at his antics.

“Is that a lie, Ouma?”

“Who knows~!” Ouma replied, before using his toes to prod the detective in the side.

“Your feet are cold.” Saihara concluded and Ouma just scoffed.

“That’s what you paid attention to?”

“...” Saihara blinked. What else was he meant to pay attention to?

Ouma just sighed, sitting back up to grab the detective by the shoulders, before tugging him back down with him.

“Now stay there and provide me with warmth, your Supreme Leader commands it.” Ouma boasted, wrapping himself around Saihara, who froze, dumbfounded. Even after remembering everything, Ouma wanted him here, to stay?

“I can hear your thoughts, they’re that loud, Saihara-chan.” Ouma mumbled, as Saihara relaxed slightly.

It wasn’t that bad… if anything Saihara felt a sudden joy at being wanted, at Ouma desiring him to stay with him… it was… Saihara couldn’t really explain what he felt, but it was nice, so he stopped trying to think so much about it, and simply closed his eyes, allowing Ouma to use him as a source of heat, arms wrapped around him.

“Thanks Saihara-chan~!” Ouma beamed, with a small nishishi , and Saihara just smiled in return.

No problem Ouma.

The next morning, Saihara awoke first, and flushed upon realising his position. Somehow he’d gotten his legs tangled up with Ouma’, and one arm was trapped under the shorter boy, the other wrapped around his waist, Ouma’s own arms clinging to him in return. Saihara was pretty sure he’d lost the feeling in the arm under him, he couldn’t wriggle it, and he concluded it was dead, he’d have to wait for Ouma to move, so he could get the blood to return to it.

He didn’t have to wait long, but in the time he did wait, Saihara saw the appeal of watching the other sleep, just as Ouma had done the day before. Ouma looked like the epitome of an angel while he slept. There was no false facial expressions masking his face, or emotions, there was no mischief in his eyes, and best of all, he looked happy, a tiny smile on his face at whatever dream he was enduring. Saihara scolded himself for acting weird. Why did he feel like this around the boy.. What even was he feeling? Saihara was confused, and in his deep thought, he failed to miss Ouma stirring.

“Saihara-chan~? Earth to Saiharaaa-chan~” Ouma prodded the boys cheek, and Saihara’s eyes widened, before looking down at Ouma.

“Ah.. sorry Ouma.” Saihara tried to catch himself, and Ouma just pouted.

“My Beloved Saihara-chan was busy thinking about something else to notice me~ I’m wounded by this betrayal.”

“S-Sorry Ouma!” Saihara apologised and Ouma snickered in return.

“Just lying~!” Ouma beamed, tugging himself off of Saihara, freeing his arm, and untangling their limbs, before brushing off his clothes.

“Aw… now everything is creased... “ Ouma sighed.

“We have spares anyway.” Saihara explained and Ouma nodded.

“I know… It’s like being back there .” Ouma pointed out and Saihara shuddered at the thought. It wasn’t a false statement though, the fact they were stocked with extra pairs of their uniform did remind him of the Prison School. They did have other things in their wardrobes, casual clothes and things like that, but predominantly they all mostly settled for wearing their uniforms because it's what they felt most comfortable with.

Ouma stuck his head into the wardrobe he had, while Saihara managed to drag himself out of the bed.

“Ooo look Saihara-chan!” Ouma pulled out a long cape from the wardrobe and Saihara let out a groan. His pre-sim memories might not be a lot, but he sure as hell could remember that damn cape, and Ouma parading about in it like he was the new supervillain (because Ouma refused to be called a superhero.)

“I can look like a phantom thief with this, Saihara-chan~! Will you try and catch me though?” Ouma asked, raising a finger to his chin as he did. Saihara spluttered at the thought of chasing the boy, heart racing for some reason, until Ouma gave his trademark laugh.

“Just kidding.”

“I’m going to need to change my own clothes too.” Saihara announced. He’d also not showered for like two days now, because he’d been staying with Ouma on a night.

“Okay~ Saihara-chan.” Ouma replied, as Saihara let himself out of the room, agreeing to come back in half an hour.

Saihara didn’t encounter anyone on the way back to his room, thankfully, and was able to grab a quick shower without worry. He was grateful the rooms all had ensuites.

When he got out and headed over to the wardrobe, he found himself pulling out a version of his uniform, succumbing to wearing the same outfit once more, simply because he felt lost without it.

Saihara departed the room once more, after ensuring he’d dried off his hair the best he could, and accidently running into Komaeda once more.

“Saihara!” Komaeda gave a sly smirk, ruffling his hair with a hand, that had Saihara feel uncomfortable.

“Thanks.” Was all the luckster said before leaving, walking down the hallway away from Ouma’s from, to the staircase.

Saihara shrugged it off. Ouma already told him Komaeda was the only one who knew about his return of memories, so it was probably just to do with that.

Once Saihara made it back to OUma’s door, he gave a quiet knock, remembering to do so this time, and he was welcomed with the cheerful enter which sounded exactly like the Ouma Saihara knew. It was nice to have him back.

Ouma was donned in his normal uniform, including the cape Saihara knew to expect, because the cape was one of the few things he knew for sure Ouma loved about his uniform.

“Yoho~ Guess what, Saihara-chan?” Ouma asked, and Saihara shrugged.

“Komaeda said I was in the clear, and he’d arranged to allow me to leave the room!” Ouma beamed. Saihara guessed behind stuck in the same room for more than a month could drive anyone a little crazy.

“So I have decided you have to take me to see Amami-chan. I need to say sorry to him.” Ouma pointed out.

“Why me?” Saihara complained, but his lie was easily seen through by Ouma.

“ Nishishi , don’t lie to me, Saihara-chan, you’re elated to be able to spend time with me.” Ouma chortled and Saihara just sighed.

“Okay then. Off we go.” Saihara replied, knowing arguing with him wouldn’t be worth it.

“Thanks Saihara-chan.”

Getting down 11 flights of stairs took time, but Saihara was patient, and Ouma persisted, getting to the 7th floor without much help, but relying on Saihara from there downwards. Eventually the two made it to the first floor though, and Saihara slowly took Ouma in the direction of the dining room. Komaeda had left Ouma with a crutch, so the shorter male could use that alongside Saihara, and it did help relieve the ache in his legs, which still protested to moving so much.

The dining room was the fullest Saihara had seen it… but Saihara had only seen it twice so that kinda made sense…

Anyway, it contained everyone from the day before, but this time, Saihara could also see Kiibo, Iruma and Gonta had joined them, summarily only missing 4 of the class, Kirumi, Kaito, Tsumugi and Maki (three of which made sense to Saihara, but come to think of it, he hadn’t actually seen Maki at all.)

It was probably a sight to see, considering news had circulated between the class about the fate of the four who didn’t remember, so seeing Ouma Kokichi in the doorway, supported on his feet by a crutch and Saihara Shuuichi likely wasn’t what they expected to see.

“Nishishi , you all look like you saw a ghost or something…” Ouma snickered and Saihara could visibly see the shoulders of about half of the class relax, as Ouma unknowing confirmed his memory had returned.

Amami, as expected, was on his feet instantly, and over to the boy in a heartbeat, tugging the shorter boy into a hug.

“Idiot.” Was all the adventurer said, and Ouma just gave a laugh in reply, letting go of Saihara to wrap an arm around the taller student.

“Amami-chan was worried about me~? I’m touched.” Ouma joked and Amami just rolled his eyes, used to the boys antics.

“Amami-chan might want to let go now, before I collapse.” Ouma added quietly, and Amami pulled back, just as Ouma’s legs gave out from under him, Saihara catching the boy the best he could, Amami lending a hand too.

“Ah. Thanks. Nishishi .”

“Idiot.. You should have rested more, if you still can’t walk properly.”

“Amami-chan, A Supreme Leader like me cannot be beaten by something as simple as this.” Ouma lied and Amami sighed.

“No, of course not, Ouma, being crushed by a hydraulic press and suffering from extensive nerve damage and temporary amnesia certainly isn’t something that could beat someone as mighty as you.” Amami said, sarcasm dripping in his voice, Ouma shrugging, as Saihara helped him sit down.

“Exactly, Amami-chan” Ouma replied with a sly grin, one of the ones Saihara knew was a false mask for confidence, he’d seen it enough in the Sim to work it out already.

The rest of the students seemed to have their spirits lifted by Ouma’s evident recovery, hope for the rest wasn’t misplaced it seemed, and a few of the students seemed quite happy to engage in conversation with the short student, even if they’d all thought him annoying in the Sim.

Kiibo seemed interested in monitoring Ouma, and asked some questions about how he remembered and what triggered it, to try and aid the others in a similar way.

“Eh.. Keeboy isn’t a robot? Lame.”

Kiibo just let out a noise of protest, before opening his mouth to speak in retaliation.

“I might not be a robot, but that’s not the issue here, Ouma. The issue is, how did you remember?”

“Easy~ My Beloved Saihara-chan.” Ouma replied, before pausing, face blank.

“Or was that a lie~?”

Kiibo let out a frustrated noise before Iruma butted in.

“Oi, Brat, answer his questions already.”

“Ehhhh. Why?” Ouma complained and Saihara couldn’t help the tiny smile that made it’s way onto his face, listening to Ouma’s childish antics.

Amami leaned in, from the other side of the detective.

“Thanks Saihara. Whatever you did, I appreciate it.”

Saihara just flushed, blood tinting his face a bright red, detective lowering his head to try and hide it.

“Also, how long are you going to be in denial that you’ve got the biggest crush on him?”

Saihara promptly choked on his orange juice.

“Saihara! Are you okay?” Kaede asked with concern and Saihara just held up a hand to signal he was okay, while struggling to steady his breathing, turning to Amami with wide eyes.

“W-what?!”

“It’s so obvious, Saihara, even a blind man could see it.”

“W...what…”

“You didn’t even know… did you?’ Amami asked, with realisation, and Saihara shook his head.

“I… I like Ouma?” Saihara asked, and Amami just nodded as if he’d asked the stupidest question on earth.

It made sense the more Saihara thought about it. Ouma made him feel happy, and safe, and so weird when he was around him. But it was that weird feeling that he could finally place with Amami’s help.

Affection.

Before Saihara Shuuichi could even realize it, he was head over heels in love with Ouma Kokichi.

And he had no idea what the fuck he was going to do now he knew that.

Nishishi. That’s the end of chapter 2 c;

This fic is also on A03, under the same name, ライアーダンス, if anyone’s interested on reading it on there rather than here.

Thanks for reading~!

#ライアーダンス#kokichi oma#ouma kokichi#ndrv3 spoilers#ndrv3#danganronpa v3#fanfiction#fanfic#saiouma#kaede akamatsu#amami rantarou#korekiyo shinguuji#shuichi saihara#nagito komaeda#makoto naegi#byakuya togami#hajime hinata#himiko yumeno#angie yonaga#kaito momota#kirumi tojo#tsumugi shirogane#Dangan ronpa#DRA

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vulnerable

I am about to make a point. Hear me out.

I’ll start with Mari A. How do I know about Mari A.? Well, I have a friend named Sam, and I met Sam about three years ago on a street corner in the Richmond District of San Francisco. I had just had a fallout with my ex-something, and I saw him, walked right up to him and asked him if he’d walk to the liquor store with me to buy a Diet Coke. Sam is one of the most courageous people I’ve ever met and one of my most beloved partners in the journey. Sam’s changed a lot since then, and so have I. A handful of years, a friendship that I cannot put to words and a whole, entire podcast later, I found Mari A. Sam interviewed her.

Now, let me start again by saying that I do adore Mari’s work. She’s a creative- like me, and she puts profoundly complex, nuanced feelings and rules for surviving into simple, little lists and graphics. Sam’s expression is through recorded word and writing, and Mari’s is paper and watercolor. One of these lists is named “My Personal Rules for Vulnerability”, and rule #2 reads “Share to a Broad Audience (Internet, Books) Only What I’ve Healed From.”

Okay, let me start somewhere else. I graduated college four years ago. That’s one more than I’ve known Sam. In that year, I applied for 6 jobs, accepted one offer, spent 4 months in California, relapsed on booze, got sober again in Georgia, dated a woman long distance, got dumped by that woman, lost 40 pounds, and moved back to California. I’ve healed from everything that happened in that year. I’ve healed from the breakup that happened the night before I decided to move to San Francisco. I’ve healed from the 3 month bender that left me completely spiritually and emotionally shattered. I’ve healed from the pain of admitting my sexuality to myself and others around me.

I’ve healed from that year, and I put it down on paper. I’ve healed mostly from what has occurred from the following three years, and I’ve put it right in here. I wrote about that relationship and that I came to forgive myself for all the times I told myself that having been heartbroken was something to be ashamed of. I wrote about college and my painful time there, and that’s it’s okay to not have to be everything I want the world to think I am. I wrote about hating Burning Man, and that disappointment is a beautiful part of life. I wrote about losing the woman I thought I would love forever, and that I found true love in the form of friends, family and sister-women. I wrote about gratitude, and that in the wake of doubt, bitterness, and rage, one may still be able to find glimmers of hope.

This time, I’m going to write about vulnerability. But it’s not going to be what you think. If you’re reading this, and you’re wondering if I’m going to mention you- I’m not. And the reason that I will not tell you why I cried today, why I cried yesterday, why I see a therapist, what I talk to my sponsor about on Sunday afternoons, what I pray about, what I’ve learned from late night tarot sessions, or the words that I give to my friends at three in the morning when I just need someone to send the vibrations of their voice into my heart, is my friend named Caroline.

So, to go back to my rambly but brief history of Casey’s first year of post-college adulthood, I’ll tell you about when I went back to Georgia. I met Caroline on a Wednesday night in Atlanta. I remember her face, I remember her hair, and I remember her fucking amazing laugh. I didn’t know that night that I had found the person that I would one day refer to as my platonic soulmate and mean it. I sometimes want so desperately to tell everyone about how we met. I want to tell you why I walked up to her that night, what she had done, and what it meant for me. But I won’t.

I won’t do it because if I did, I’d take something valuable from it. I’d take its sanctity. I’d do a dishonor to something that holds power and weight between us and couldn’t possibly be translated here. What I will tell you is that our friendship was born in a moment of vulnerability. I will also tell you that we have worked on this relationship- that it’s not just a story of two people who were meant to know one another. We’ve given years, commitment, and unconditional love.

Caroline was the first person I ever met who truly understood what I was feeling and thinking. We now live 3000 miles apart, and I can still see the image in my mind of the way she leans her head on her hand when we sit on her couch and talk. Caroline and I have a rule that we can’t hang out on the first night that I arrive in Atlanta, because I always bail last minute, and we’ve adjusted our expectations. She told me on the night before I moved to California not to call anyone when I arrived because that moment was for me, and I have never felt more respected and appreciated as a human being than I did in that moment.

What Caroline has taught me about vulnerability is that I don’t have to go around shouting from rooftops everything that sings or screams inside of my heart, all the ways that I’ve been imperfect, or how I have loved in order to make a connection with you. I can tell you about how I’ve learned to be a better friend, how I’ve learned to let another person love me for who I am, and how I feel about true love in the form of a best friend, but you don’t need to know about what we say on that couch, the reasons why we call at three in the morning, or how we met. She taught me that when the moment is right, and if I channel a tiny bit of courage, when I unveil myself, I might reach the one human being that is ready to take it all in.

I always start these posts with the urge to completely untether everything that inside of me. And damn, even that gratitude list I wrote was initially meant to be a way to poetically unleash all that I am fucking upset about. I started today with the intention of telling you why I think Mari is wrong- why I think I should be able to throw caution to the wind and put my vulnerability on a shrine. But I remembered a few very important things.

I remembered the things I tell my therapist and my sponsor, and how I’m willing to tell you what I do to take care of myself and to heal, but that there are some things that stay safe with us. I remembered the relationships and connections that I have that are so beautiful because they are light and fun. I remembered that the connections that I am most vulnerable in have taken root in time and effort. I’ve learned that boundary setting, and boundary honoring, is a practice that works both ways between two people, and with myself. I learned today that Mari was right. Damn.

So the question then becomes this- how I can I share with you what I feel and know and honor myself and the things that are sacred to my process? Can I be brave and dignified at the same time? Have you earned it? Have I?

Well, I’ll give up a few things. I’m going through it. I’m still healing from the breakup. I’m annoyed that it’s taking so long, but I know in time it will heal. The rest of the story will stay with Sam, Caroline, Holly and Elizabeth. I’ve seriously reconsidered whether or not I can justify spending the rest of my life in San Francisco, and I have plans to relocate somewhere that I can build a real life in the next few years. That realization is thanks to a person whom I owe immense amounts of gratitude, and who I will cherish having met forever. All the reasons why and how will stay with my mentor, my therapist, and with her. I struggle with work-life balance, and I am working on setting boundaries while maintaining myself as a professional woman in the workplace. I’ll tell you that it requires goal setting and doing shit I don’t want to do when I don’t want to do it, but the pieces that I haven’t discovered yet will remain in my heart’s chamber until I’m ready to tell you about the fallout and the growth. I am releasing friendships that no longer serve my well-being. I am working on communicating that kindly and with love, but that is an ever evolving process. I am discovering my purpose, and at times it has been painful, but I’m walking. I’m happy that some have asked about it and have come along for the journey. If you have, thank you for walking up to me.

And for you: when all is said and done, be a flower in the garden, be one with the sun.

That’s all I got for ya.

@bymariandrew

MY PERSONAL RULES FOR VULNERABILITY

1. Reveal secrets and wounds to love interests only as they are earned- not to test anyone’s immediate acceptance of me or to judge their reaction

2. Share to a broad audience (internet, books) only what I’ve healed from

3. Keep a lot only for myself- true vulnerability requires discernment

4. Do not tell every single thing that has ever happened to me on a first date as a sign of affection

5. Use vulnerability as a tool for deeper connection, empowerment, survival. Do not use it as a tool for manipulation, revenge, gossip, making people feel sorry for me, any ego-driven purpose (I hope this is always a DUH but it seems worth noting)

6. By definition, vulnerability means putting yourself out there. It’s a big risk, and one I must be willing to make. I risk that the reaction won’t be what I wanted. I have to be okay with that and own my stories anyway.

0 notes

Photo

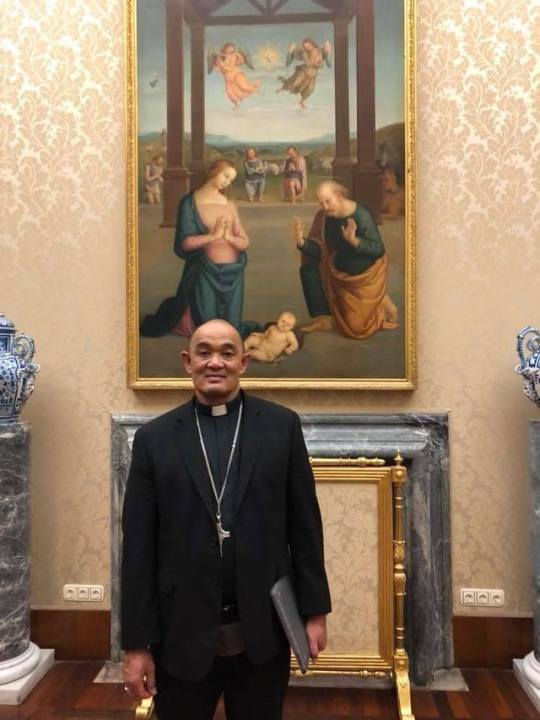

The Archbishop versus the WB on Fiji poverty (FT 23 Feb. 2019)

Last week (Fiji Times 17 Feb. 2019), Catholic Archbishop Peter Loy Chong mounted an astonishing broad-ranging critique of the powerful international organizations, World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), alleging that their policy advice to the Bainimarama Government (and developing countries) was “anti-poor”.

Apparently, the Ministry of Education (PS Burchell) had used WB advice as part of their justification for using the Open Merit Recruiting Selection (OMRS) to appoint principals of privately owned schools.

Archbishop Chong, however, not only criticized the Bainimarama Government’s plans to privatize schools and hospitals, but with the sermons of the Catholic Pope John Paul II to guide him, saw these WB and IMF strategies to push globalization and privatization on the Third World, as being primarily in the interests of the developed corporate West, while harming the poor in developing countries.

Just as surprising, despite the serious criticisms made by this reputable and responsible Head of the Catholic Church in Fiji, there has been no public response from the Ministry of Education and the Bainimarama Government, nor from the academics of the three universities in Fiji, and none from the WB either, not surprising given their total lack of accountability to the public whose welfare they “advise” on.

Nevertheless, I would suggest that readers and in particular economics students should carefully and critically read the arguments made by Archbishop Chong, simply because the WB and IMF have such great influence over economic and social policies of Third World countries like Fiji, profoundly affecting the lives of our poor. Are Chong’s arguments all correct or should some be qualified (as I suggest below)?

Archbishop Chong’s criticisms are even more pertinent in the light of the most recent IMF Article 4 recommendations to the Bainimarama Government (Fiji Times, 20 February 2019) but that deserves a separate article.

To help students see more clearly, I summarize Archbishop Chong’s arguments into four sets of inter-related important development topics:

(a) the WB/IMF and their Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs)

(b) the impact of globalization on the world’s poor

© the impact of the Bainimarama Government’ privatization program on Fiji’s poor, and

(d) whether WB, IMF and the Bainimarama Government are following the principles of genuine democracy in their decision-making.

I add any disagreements I may have or qualifications in italics.

The WB, IMF and the SAP

Archbishop Chong asserted that when Third World Countries cannot repay their loans from WB and IMF (and I suggest sometimes even when the capacity to repay debts is not an issue) these institutions instruct our countries to carry out Structural Adjustment Programs which include reduced government spending on essential services (like health, education, welfare), reduce taxes of high income earners, implement other market oriented policies such as privatization and globalization, and the ORMS (I doubt if this was important to the WB or IMF), all making the rich richer, and the poor poorer (I argue below, not always), thereby widening the gap between the rich and the poor (not always, I suggest).

In the process, the poor are rendered powerless, worsened by the lack of effective protection by workers’ associations.

Archbishop Chong argues that the central objective of the WB and IMF is not to alleviate poverty in the developing countries, but to advance the agenda and economic interests of the West. (I suggest below that the “west” is not an accurate category any more, given all the new Super Powers that benefit from globalization, like Japan, China and India. I also elaborate below on the “unaccountable” nature of WB and IMF).

Globalization and the poor

Archbishop Chong argues that while globalization promises that development will trickle down to the poor, that trickle down has not happened historically (I suggest below that Chong is not completely accurate); the rich have become richer and the poor have become poorer, with the gap between the rich and poor widening. Globalization is like a ship with no map headed for shipwreck (it is also not clear that this is so.)

[In some countries, the poor have become much better off even if the rich have become richer. For instance, development economists have still not caught with up the most incredible economic miracle over the last two hundred years of China using globalization and increased access to global markets to lift more than 400 million people out of poverty. Sure, the rich have got richer (there are more Chinese and Indian millionaires in the world than that from most developed countries), but their poor have also become much better off. This is so not just in China but also in places like Korea, Brazil, Malaysia and now slowly even in India, still massively plagued by abject poverty.

Of course, the gap between the rich and the poor might have increased, but it is not correct to generalize that globalization has universally “made the poor poorer” just because the gap has grown wider or the rich have got richer.

Ask the poor “would you rather stay poor while the rich remain the same” or “would you prefer to become richer, even if the rich become richer still”? Or ask poorly paid garment workers in Fiji “Would you like a poorly paid job, or no job at all”?

Whatever leftist (usually well-off) activists might recommend, we know what the poor themselves would answer to both questions.

Bainimarama Government’s Privatization Plans and the poor

Archbishop Chong argues that the Bainimarama Government’s plans to privatize the Lautoka and Ba hospitals and schools will hand over these essential services to the private sector who will put profit before service and worsen service to the poor. He correctly sees that it would be totally unfair given that taxpayers are already paying taxes precisely for these essential services for which they will pay again from private providers, without their taxes being correspondingly reduced. Chong argues that this implies that that the Bainimarama Government and politicians would be serving the WB and IMF, not the Fiji people (not necessarily so).

[It has been my experience that over the decades since Independence, succeeding Fiji governments (including the Bainimarama Government) have referred to the WB and IMF only when it has suited the government. There has been much WB/IMF advice which has been simply ignored by Fiji governments.]

Catholic teaching on genuine democracy

Chong notes that Catholic social teaching emphasizes that the human person ought to be the center of all policies not the World Bank or IMF policies.

The people must participate in the decision making, knowing full well what the decisions mean for their own welfare and to themselves as people.

All citizens must practice genuine equal relationships and genuine (not just token) solidarity with the community, for the good of the community and the planet (environment). Policies, like the ORMS, must not be imposed on the community by any government or outside agencies like the World Bank and IMF.

These arguments by Archbishop Chong go to the heart of the invidious role played by World Bank and IMF staff in developing countries like Fiji.

In the sections below, I elaborate but also qualify and disagree with some of the ideas presented by Archbishop Chong.

The Unaccountable World Bank (and IMF) Staff

Do Fiji people ever wonder where WB and IMF Teams come from, who they serve and who they are accountable to, for the advice that they give, often with grave consequences for the poor among us?

Of course, these WB and IMF persons, based in Washington or wherever are extremely intelligent and qualified professionals in their own fields. They are drawn mostly from the developed countries but increasingly from the large developing countries like India and Bangladesh. They are paid phenomenally high tax-free salaries which are many times that of the Prime Ministers or Permanent Secretaries in the countries they advise.

Most importantly, these anonymous god-like “advisers” are not accountable to the developing country people but only to their superiors in Washington, whose ideas and priorities they must propagate, if they are to look after their careers. The local people’s interests and views are not their priority.

They work on priority areas, workplans, and projects decided by their superiors in HQ, and at the times decided by their superiors. One of the tragedies for us is that these work plan priorities change over time without any correspondence to the needs of the countries to whom they deliver their “advice”.

My personal experience of WB

In the nineteen nineties I myself worked for eighteen months, as USP’s contribution to a two person team (with Australian consultant and later WB staff member Ian P. Morris), on a six Pacific country World Bank project in the field of secondary and post-secondary education, whose massive reports are in the USP Library. Morris and I had to work hard to change the WB pre-conceived idea, based on narrow rate of return analysis, that the focus of government should be on lower level basic education and not tertiary. Morris and I had argued that the Pacific countries needed graduates at all levels, and especially at the tertiary levels given the huge backlogs in training during the colonial era. Thankfully, they had agreed. At that time, the WB was far more concerned about wider development issues than the IMF.

But then the WB priorities changed and they disappeared from the education scene, I suspect leaving it in some uncoordinated fashion to ADB and Forum Secretariat for both whom I also personally did some consultancy work on basic education and technical training in the Pacific (those reports are also in the USP Library)).

Then, some five years ago, WB staff (different lot of course) reappeared in Fiji working on Fiji Bureau of Statistics household survey data, producing a technical report on poverty in Fiji. They essentially replicated the work I had been doing (with some additional “small area” estimates based on census data), but at probably fifty times the cost of my services to the FBS. Their results were pretty much the same as mine, except they were grossly wrong on the lack of changes in poverty in rural areas (I suspect because of errors in their methodology). These WB advisers never explained the discrepancies with our results and disappeared without creating any capacity in the FBS to continue the work they had been doing. The WB have never cared much about developing local capacity and sustainability of research capacity at the local universities. Why should they? There would be no need for their services if they did!

The WB never organized any national workshops of the kind that I assisted the Fiji Bureau of Statistics to conduct (with the great support of the Government Statistician then (the late) Timoci Bainimarama) or later (Epeli Waqavonovono) not just in Suva but also Labasa and Nadi, with Fiji Government departments and NGOs. They were facilitated by USP (Dean of FBE Professor Biman Prasad) and Fiji National University (Dean Dr. Mahendra Reddy and VC Dr. Ganesh Chand). These workshops truly democratized knowledge among the local communities- never a concern of WB or IMF. Sadly, such workshops are no longer conducted by the FBS.

But essentially, WB “advisers” come and go from countries like Fiji, depending on WB priorities, not ours. What is horrifying is that after giving their advice (good or bad), they never return to be accountable to the local people as are local professors of economics, or the Catholic Archbishop of Fiji, or the Bainimarama Government currently (we leave out their totally unaccountable period from the 2006 coup to the 2014 elections), or Opposition Members of Parliament.

Neither is there any genuine collective democratic participation of the local community in the decision making as Archbishop Chong called for in his Fiji Times article. Simply holding elections is not “democracy”.

WB Not Serving the “West” anymore.

In the early decades after WWII, those controlling the WB and IMF were indeed the Super Powers from the “West” as Archbishop Chong alleges, but they also included Japan from the East.

In recent decades, however, China and India have become far more important in world trade and globalization. Indeed, any economic forecasts for the economies of developed countries nowadays begin with economic projections for China and India, just as they used to thirty years ago begin with forecasts of US, Europe and Japan. So the benefits of globalization are not any more just the monopoly of developed countries of the “West” as used to be the rhetoric twenty years ago, but must also now include new countries in Asia (China, India, Korea, Malaysia, Indonesia) and South America (Brazil).

Unfortunately, not discussed much at all in our media (which is sadly mired in moronic discussions about rugby sevens), is that new Super Powers like China, India and Brazil, are facing an uphill battle behind the scenes to try and gain their proper voting rights on the bodies that control World Bank, IMF and World Trade Organization (WTO) which is an even more influential international body for globalization.

It will be interesting to see whether these organizations change in any way when China and WB do obtain greater say on their boards. I suspect that as Trump has done with UN organizations, they will simply withdraw their contributions and apply pressure elsewhere.

Who needs the Structural Adjustment Programs?

Note also that while most Western countries have long protected their domestic goods and services from the cheaper goods and services being produced by the newly emerging countries, the pressures from globalization as implemented by WTO, mean that many non-competitive domestic industries in the developed countries are collapsing, giving rise to the Trump and Brexit phenomena. Even in Australia, after decades of sucking up billions of dollars of taxpayers’ subsidies, the essentially uncompetitive car manufacturing industries have closed down, causing great angst amongst the redundant workers, unions, and political parties.

It is not hard to understand that high wage industries in Australia and US (like car or shoe manufacturing), cannot compete with the same products produced by the same companies, using the same technologies, in developing countries like Brazil or China or India, where the wages are one fifth of that in the developed countries, where workers work much harder, for longer hours, and without all the expensive health and safety regulations and environment protections, and often without the unions that prevail in the developed countries.

All these developed countries and their governments (as here in Australia) face the conundrum of stagnant real wages in industries which are subject to the harsh discipline of free markets and globalization.

These Western countries (including US, Japan and Australia) need Structural Adjustment Programs and lower wages or restrained wage growth, but the WB and IMF are rarely to be seen or heard giving stern advice and SAPs to their governments in the same way they do to weak Third World countries like Fiji. In any case, the developed countries could not care less about WB or IMF, unless they are totally mired in debt and need loans to bail them out, as do bankrupt countries like Greece. Fiji is not there, yet.

The Fiji Government and the Fiji public need to heed the advice of responsible and reputable clerics like Archbishop Chong (with their vows of personal poverty), who have no political agenda or vested material interest to gain in giving that advice. Unlike the grossly over-paid WB and IMF Teams, Archbishop Chong is not going anywhere soon and can be held to account by Fiji people.

0 notes

Text

Thinks: Ina Blom

Appreciating the Weirdness: An Interview with Ina Blom

Ina Blom: If I’m a little bit off, it’s because for some time now I haven’t slept much, after a bad bout of flu. But I’m symptom free now!

Keeley Haftner: Yes I’m glad to hear your feeling better, and we’ll forgive you for any illness-related errors [laughs]. So I’d like to begin with the basics. You teach at both University of Oslo and the University of Chicago; what do you find most different and most similar about working between these two contexts?

IB: I mean, both are art historical departments, but I think the greatest difference is that while we do have a number of foreign students in Oslo, I think the international mix in Chicago tends to be greater. In Oslo, teaching tends to be more lecture-based, with larger classes, whereas in Chicago it’s generally more seminar-based. Also, importantly, the University of Chicago is an expensive private university, where in Scandinavia all universities are state-owned and basically tuition free, and this of course creates a different study environment. The free education system also draws foreign students from beyond the EU. I probably shouldn’t advertise this to the world [laughs], but so far the government is keeping it free also for non-EU students because they want more people around the world to be aware of our research institutions.

KH: Let’s talk about your writing. It has appeared in a number of different types of publications, including art critical journals such as Artforum, Afterall, Parkett, and Texte zur Kunst, and exhibition catalogues, as well as more standard academic journals and publishing houses. Would you say that this allows you more freedom within your writing practice?

IB: Yes, absolutely. I started out as a music critic and radio DJ many years ago, so I got a lot of training in basic journalism and various genres and styles of writing, depending on the publication and the audience – from straightforward reporting to the more literary or essayistic and the more academic. I really enjoy being able to have different voices for different contexts, and I also just enjoy writing! [Laughs] One of the reasons I went back into academia was because I got a bit fed up with the free-wheeling, impressionistic voice that was de rigeur in most music journalism. The more analytic side of me wanted to be more hard-edged and focused, and also more philosophical, and this did not always go down so well in the more journalistic contexts. So ultimately I felt greater freedom having the academic world as my main professional platform. But I really enjoy the back and forth between different contexts.

KH: I’m thinking about the article you wrote for Artforum’s September 2015 issue, which was accompanied by what is probably one of the most arresting covers for the magazine I’ve ever seen (Torbjørn Rødland’s Baby (2007)). Can you describe how his innovative approach to photography, as you say, “the entire image made punctum”, holds your interest in reference to your larger research interests?

Torbjørn Rødland’s Baby, 2007, as seen on Artforum, September, 2015. Photo Credit: Artforum

IB: I’m not sure that there is a direct link, per se. As an art critic, I tend to be most interested in works that I don’t immediately “get”– when I can’t instantly tell what the work is about or what exactly the artist’s project is. Rødland’s work is very much like that; his photographs are always somewhat mysterious to me and I feel I’m always kind of scrambling to understand what he’s doing, and my own response. In the mid-90s, he got a lot of attention because he appeared to rehearse an nineteenth-century Nordic Romanticism that seemed contrary to the conceptually-oriented art practices that was re-entering art practices at that time, and also very much at odds with my own preoccupation with Dadaism, Constructivism, Fluxus and other anti-romantic- and anti-expressionist forms of art. Rødland seemed to recirculate Romanticism with a strange and idiosyncratic twist that made you pay attention. This was something completely different from conservative-post-modern pleas for past glories or ironic recirculation of too-familiar motifs. You simply had to pay attention in a new way. So that was the beginning of my interest in this work, but as his project grew I think the images just got stranger and stranger. And increasingly I started to think about them as opening up the horizon of what photography is and can be, in really new ways – pertaining, among other things, to the relationship between images, technical apparatuses and various types of natural phenomena, as well as the question of the contagiousness of images and their affective dimensions. These were ways of trying to approach his take on photography, but I still think they are inadequate in terms of just appreciating the weirdness of his work, which I think is great.

One of the first articles I wrote about his work was called “I’m With Stupid”, because I was obsessed with rock and roll stupidity, which I think is a sensibility I shared with Rødland. The celebration of idiocy, all those things for which there’s no explanation and no excuse. So I wrote a long essay about how that sensibility made its way into his work, and how that’s also linked to a celebration of vulgarity, which Robert Pattison sees as the underlying romantic impulse in rock. Vulgarity here has nothing to do with bad taste – it is rather a sort of blankness that refuses to recognize given hierarchies of values or systems of knowledge. This is yet another half-baked critical approximation which may be meaningful to some extent, but which does not say all there is to say about the work.

KH: In a studio visit I had with you while at the School of the Art Institute Chicago, I seem to remember that in your own words, you encouraged me not to beat the dead horse of Conceptualism, and emphasized the importance of sincerity over the ironic in contemporary production. I’m wondering if you can talk about sincerity after Conceptualism and Minimalism?

IB: It’s not as though I want to promote one attitude or approach over another. I’m just afraid of anything that becomes a default mode of operation that art students feel obligated to follow no matter what. The critical/conceptual art practices and their traditions are incredibly important to me, but they carry a specific form of authority which can be crushing, and which, in its less intelligent or self-critical moments, becomes just another form of academicism. Anything that is able to present itself as the one proper critical approach may have this effect, and will easily appear as more valid than something whose framework or mode of operation is less clearly formulated. I believe that art students should be thoughtful and critical in their approach, but good art does not always emerge from well-formulated critique. So this is why I get a bit concerned when students seem to feel they need to justify their work in terms that are perhaps at odds with their best capacities and resources. There should be a lot of room for following pathways that have as yet no clear direction.

Bill Viola, still from Reflecting Pool, 1979. Photo Credit: Bill Viola

KH: And you have a lot of different modes yourself, in terms of your focuses throughout your research. Shifting to one of these modes, I’m thinking about a term you briefly used in On the Style Site. Art, Sociality and Media Culture from back in 2007: the term “social site”. Can you talk about how it does or does not relate to Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics?

IB: The key term for me there was “style site”, which I used in order to honour the idea of site specificity while also questioning the idea of the simple access to something called “the social” in art practices of the 1990s and early 2000s. I was profoundly skeptical of the concept of relational aesthetics, and the way a number of works seemed to have been reduced to the idea of convivial togetherness of one kind or another. I saw very different things in the work of a lot of the artists associated with this new form of sociality in art, such Philippe Parreno, Liam Gillick, Rirkrit Tirivinijia, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and others. These works were not just about people gathering and doing things together, such as cooking. Every single one of these works was actually a media machine. They were without exception channeling other times and other places, inserting them into the live “here and now” of togetherness through a dynamic that was reminiscent of what is accomplished with real-time technologies such as television or digital networks. On closer look, these works turned out to be exceptionally complex assemblages that often associated televisual dynamics with the time-machine aspect of architecture, fashion and design elements – a whole range of phenomena traditionally linked to the phenomenon of “style”. Style used in this way was not about the look of things, or a static description and periodization of art history. It was all about the open-ended becoming or self-styling of modern subjects. In the works in question, architecture, design and fashion appeared as integral elements of media machineries that were no longer defined in terms of the programs or messages it presented to the public. Instead they were understood in terms of their role in the modern “production of subjectivity”, which many would claim is the key product of media and information industries, and their appeal to our apparently endless desire for self-development. Does this make sense?

KH: Yes, it does, and it makes me think about how you’re approaching media not only in terms of communicating the subjective but also in terms of the collective legacy of our technologies and data. I know some have referred to your research practice as a “media-archaeological approach”, which makes me think about your collaboration with Jussi Parikka, Matthew Fuller and many others in your latest anthology Memory in Motion. Archives, Technology and the Social.

Steina Vasulka, still from Orbital Obsessions, 1977. Photo Credit: Steina Vasulka

IB: Yes, this book came out of a research project called the Archive in Motion and that I headed at the University of Oslo. The project took a media-archaeological approach to the question of the contemporary archive, exploring how twentieth-century media technologies have changed our very understanding of what an archive is. The other book that I did which related to that project was called The Autobiography of Video. The Life and Times of a Memory Technology, where I really approach early analog video technologies as a set of agencies that explore their memorizing capacities in interaction with human actors, within the context of 1960s and 70s art. I spent a lot of time learning the ins and outs of video technologies, and the upshot was a story about the way in which these technologies propelled new social ontologies in the field of art production. In related ways, the point of departure for the Memory in Motion anthology was the basic sociological claim that society is memory. The idea was that fundamental changes in the technologies of memory might also change our idea of what the social is, how we should define whatever it is that we call social. Older memory technologies seem to privilege storage, containment, and stability over time, and seem to have promoted an idea of the social as something contained. But the ephemerality of contemporary memory technologies – which are all about updating and transferring in the present moment – may support a very different social ontology. So ultimately we were exploring the connection between technology and social thought, in many instances as articulated through early artistic prehensions of the implications of new media technologies.