Text

Alf Seegert

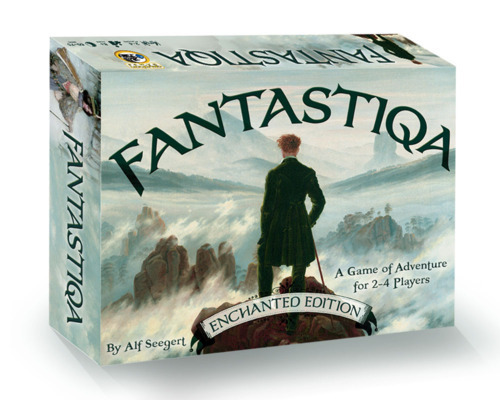

Ah, game designer with a PhD in Literature? Yes, I suppose that would be a good person to write an essay for this blog. When he sent it, Alf heavily encouraged me to edit the piece, as it is long-ish, but after reading it I could barely touch it. You'll see why in a moment. Oh, and by the by, Alf's latest game, Fantastiqa, will be hitting Kickstarter soon, so keep an eye out for it.

Why I Design Games

Last week, exactly one day after Towel Day, I turned 42. For reasons unknown to me, I was inauspiciously denied a precise commingling of a) my birthdate, b) the official celebration of the life and work of Douglas Adams, and c) the numeric answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything. Unless I discover an Adams-worthy remedy involving a time machine and contraceptive device, I’m out of luck.

Ah, one must cope, I suppose.

But I am getting ahead of myself. The question Evan Derrick asked me to answer is “Why Do You Design Board Games?” I will do all I can to occupy the high ground here and shake off the temptation to respond with any of several less-than-worthy responses that spring to mind. (“Why Design? To impress Jodie Foster, of course!” occupies the tippy-top of that list of bad answers.) A better answer might be, “Because I’m better at designing games than I am at playing them.” This is true, but doesn’t really hit the mark. I care little for winning in itself, and Reiner Knizia’s maxim (or my reading of it, anyway) applies: the goal of the game is more important than its attainment. But before I say any more, let me offer a few words by way of context—the obligatory “gamer bio.”

Boardgames have fascinated me from a very early age. Candyland, as I remember, rocked my early 1970s post-toddler Head Start world with fierce abandon, almost as much as the film Earthquake did, minus the Sensurround. I also recall that my neck-hairs would stand on end when playing Which Witch and Mousetrap because of how they combined suspense, strange pieces, and risky (or violent!) consequences. During the horrors of early 1980s junior high school, fantasy role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons and Tunnels & Trolls were a safe-haven for me (my friends, thankfully, were fantastic DMs capable of conjuring worlds far preferable to the actual one I found myself in at the time). I became enthralled by Milton Bradley's electronic board game Dark Tower and in ninth grade I programmed a fully functional version of it into the high school mainframe computer (I used little monochrome ASCII characters to represent each player, the Tombs, Ruins, the Bazaar, etc.). It worked surprisingly well, and I think that the pleasure I found in “reverse-engineering” Dark Tower for the computer anticipated much of my love for games to come, as well as my wanting to make games of my own.

Except for an occasional session of the fantasy game Talisman—which I mostly played to enjoy an “RPG-lite”— the next 15 years saw little time spent with boardgames. Circa 2000 I was spending most of my game time in front of the computer, all by my lonesome. My girlfriend (now my wife) wanted me to play games with her instead of a machine, so we did some research and stumbled on The Settlers of Catan, which proved a potent gateway drug into the brave new world (well, new to us) of Eurogames. Once we introduced Catan to our friends, Saturday nights quickly became a regular and much-anticipated "game night" event, which has continued now for over ten years. (Though, alas, with much less regularity. I loathe this thing called “growing up” and resist it to my best ability.)

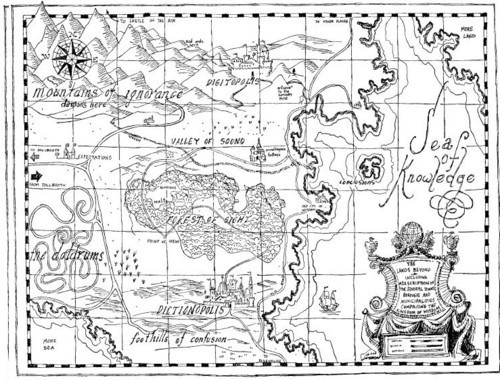

Playing such engaging Eurogames eventually inspired me to start designing games of my own. I've been designing games since 2001, and over the years six of my designs have become end-round finalists at the annual Hippodice board game design competition in Bochum, Germany (The Vapors of Delphi, Ziggurat, Bridge Troll, Mont Saint Michel, Tembo, and this year, Druid Stones). Three of my games have been published so far-- Bridge Troll, Trollhalla, and The Road to Canterbury. My latest game, Fantastiqa, is being launched on Kickstarter by Gryphon Games later this month. OK, bio over and now we know each other a bit better. In line with the appeal that games have for me, a better answer for “Why Design?” might simply be, “Because I can’t help it.” Why can’t I help it? I suspect it’s because that as I grow older I more-and-more want to inhabit the fantastical worlds that I grew up reading--and which I still read. The most formative book of my childhood was The Phantom Tollbooth. Just look at the map!

If you are anything like me, this map will impel you to hit the accelerator in your toy car, drive straight through that Tollbooth and vroom your way into The Lands Beyond, to wander the Foothills of Confusion, jump to Conclusions (the island, that is), enter voluminous Dictionopolis (and there banter words with King Azaz the Unabridged), and lose yourself in the Mountains of Ignorance, ultimately rescuing the abducted Rhyme & Reason from the Castle in the Air… There’s something intensely, playfully satisfying not only in Norton Juster’s story, but in Jules Feiffer’s visual representation of it in the illustrations. (Avoid the animated film version at all costs—it’s disastrous.)

I know, I’m supposed to be talking games here, but you can probably tell that I put games and stories together in a much bigger bin than either one of them, namely, play. And play depends foremost on the capacity for “As If”: the taking seriously of a book, or a game, as a self-consistent sub-world “as if” it were an actual place, one you genuinely care about. Like a children’s fantasy book, a board game offers the opportunity to inhabit, however briefly, a different world—yes, to escape.

In “On Fairy Stories,” J.R.R. Tolkien defends the impulse to escape by revealing some crucial nuances to the word. One type of escape is the flight of the deserter—not his advocated course of action. But another type of escape is that of one unjustly imprisoned. I think that most of us belong in this latter category, imaginations imprisoned behind bars which rattle but rarely budge. A fantasy world is the sharpened file smuggled inside the prisoner’s cake. More specifically, something about the miniaturized, bounded effect of a game board evokes fanciful imaginings. Like the endless hallways in Mark Danielewski’s House of Leaves, a game board’s world is bigger on the inside than it is on the outside. In his spiritual autobiography Surprised by Joy, C.S. Lewis recalls something like this effect occurring within the bounded space of his brother’s biscuit tin:

“Once in those very early days my brother brought into the nursery the lid of a biscuit tin which he had covered with moss and garnished with twigs and flowers so as to make it a toy garden or a toy forest. That was the first beauty I ever knew. What the real garden had failed to do, the toy garden did. It made me aware of nature—not, indeed, as a storehouse of forms and colors but as something cool, dewy, fresh, exuberant. I do not think the impression was very important at the moment, but it soon became important in memory. As long as I live my imagination of Paradise will retain something of my brother’s toy garden.”

As I see it, my own games succeed or fail based on their participation in such enchantment—on whether or not the imaginative world inside the box is bigger than the box enclosing it. Of course, the material in the box only comes alive in the imagination when players actually play. To facilitate that I strive to make it fun for the players to lose themselves in strange characters: horrible, hungry bridge trolls; marauding troll-Vikings; or cackling medieval pardoners preying on pilgrims wending their way to Canterbury.

Image Courtesy Chris Kirkman

I felt my first twinge of that biscuit-tin excitement in one of my own games when I saw Ryan Laukat’s brilliant artwork for the big Trollhalla game board and pieces. Bridge Troll had wonderfully grotesque trolls, but Trollhalla presented a fully realized fantasy landscape, complete with weather gods, Viking ships, panicked peasants and pigs, mortified monks, and hazardous Billy Goats. The Road to Canterbury likewise evoked an alternate world—this one grounded in the history of religion—in the medieval England of Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, thanks to some help from an early illuminated manuscript and some mildly anachronistic posthumous collaboration with Hieronymus Bosch.

Image Courtesy Chris Kirkman

My upcoming game Fantastiqa is a case study in why I design because it distills everything I have loved all my life in fantasy landscapes and strategy games.

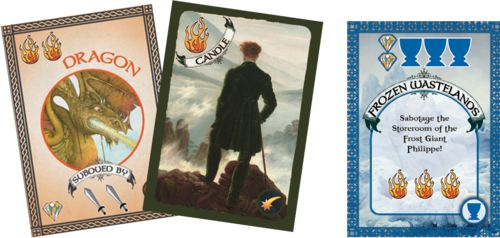

The result is a design that one Italian game blog has conjectured to be “Talisman meets Dominion.” That’s not a bad characterization, actually—with a couple of qualifiers inserted. First, Fantastiqa harnesses the spatial aspects of a board for deck building in ways I haven’t seen before. The cards you have assembled in your hand affect where you can adventure on the board, and where you are on the board in turn affects the kinds of cards you can draw and the quests you can fulfill. The layout of Regions on the board changes each time you play, insuring a lot of replayability. Second, none of the cards in the game has any absolute value—they instead work like an ecosystem of relationships. In most games, a “10” beats not only a “9” but also all numbers under nine. In Fantastiqa, each card instead has a unique ability and vulnerability, meaning that it defeats one type of card symbol, and is defeated by another type of card symbol. The effect is like a big game of rock-paper-scissors without the simultaneous play: you use your cards in hand to carefully subdue other cards and then add them to your deck so you can use them for further subduing and to fulfill quests. As a player, you will want the benefits of having multiple card types in your deck, but you don’t want a big diluted supply of cards, either. It’s a tough balance.

So although Fantastiqa aims for the charm (and yes, some of the silliness) of a questing game like Talisman, it’s a genuine strategy game instead of a random dicefest. (I’ve ensured that by including no dice in the game.) You’ve got to manage your hand carefully and make hard choices about how to commit your cards: on your turn should you subdue more Creature cards on the board and add them to your deck? Or should you commit these cards to quests right now? Should you draw from your limited supply of magical powers to expedite travel to the Frozen Wastelands and get there before other players do, using a candle and a fire-breathing dragon to fulfill a 3-point quest to Sabotage the Storeroom of the Frost Giant Philippe? Or simply draw more quests to open up more options? Or use your supply of Gems to buy an Artifact or a Beast?

For me, the challenge that board-game design sets before me is to make games that are engaging but streamlined, complex but not complicated: games with high “simplexity.” So with Fantastiqa, I have steered for the “Goldilocks spot” somewhere between the random chaos of Talisman and the brilliant but exhausting complication of Mage Knight. (I’ll have a lot more to say about Fantastiqa in my upcoming Designer Diary on BoardGameGeek.)

OK, enough product promotion. So, why do I design?

I began by writing about my 42nd birthday, and I did it for more reasons than just because of its resonance with the beloved Douglas Adams and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. When you hit 42, you are old enough to sense that you had better be doing what you’re called to do with the rest of your dwindling life, and not waste your time. But at 42 you’re still naïve enough to take playfulness seriously. So I do. (And I hope I will feel the same way 42 years from now.) Norton Juster, author of The Phantom Tollbooth, says that the secret to his doing anything is to do something else to get away from that—but importantly, “that’s the thing that turns out to be worthwhile — whatever you’re doing to escape from doing what you’re supposed to be doing.” Put another way, your avocation becomes your true vocation, but only if you pretend it isn’t. So, why design? Or why play, for that matter? For that.

Alf Seegert is Assistant Professor (Lecturer) in the Department of English at the University of Utah. He is the designer of the strategy board games Bridge Troll, Trollhalla, and The Road to Canterbury. Visit his webpage at alfseegert.com

Alf’s newest game, Fantastiqa, will be published by Gryphon Games and is set to launch on Kickstarter this June. Find out more at fantastiqa.com

Alf is a member of the Board Game Designers Guild of Utah (bgdg.info).

#alf seegert#trollhalla#the road to canterbury#fantastiqa#the phantom tollbooth#c.s. lewis#j.r.r. tolkein#douglas adams#the hitchhiker's guide to the galaxy#dark tower#talisman

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Road to Canterbury | Designed by Alf Seegert | Image Courtesy of Chris Kirkman

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Trollhalla | Designed by Alf Seegert | Image Courtesy of Chris Kirkman

0 notes

Text

Seth Jaffee

Seth Jaffee's excellent deck building game, Eminent Domain, was one of the first games to ride the Kickstarter wave. In fact, the game's rampant success is what first introduced me to the crowd sourcing phenomenon. The latest game to bear his influence is Ground Floor, which has demolished its Kickstarter funding goals (par for the course) and (as of this posting) has only four days left in its campaign. Here are his thoughts on design and his fantastic advice for new designers.

My name is Seth Jaffee, and I’m a Game Designer. I’ve had a couple of games published, and I’ve worked as Game Developer on several others as well. My friend Michael Mindes started a publishing company called Tasty Minstrel Games, and I act as TMG’s Head of Development.

I have been interested in and involved in game design for about 10 years now. Even before I got into board game design, I spent many years building decks in Magic: the Gathering (which is very similar to game design). It’s been so long I can’t really remember how I got into it, or what it felt like NOT to be interested in game design. Someone asked me recently how to get into the hobby, and after some serious thought, this is the advice I had for him:

1. Play a lot of games! And a lot of different types of games too. There are some who prefer to keep their distance from other designs so as not to be influenced by them. I do not subscribe to that at all. Play a lot of games (especially new games) to see what’s out there - see what works and what doesn’t. I like to keep up to date with advances in game technology that have occurred recently, and having a library of proven mechanisms to draw from can be very helpful.

2. Utilize resources such as the Board Game Designers Forum and BoardGameGeek design forums. There is a healthy amateur design community that is welcoming of new designers and is often willing to critique game ideas and rules. Everybody has their own opinion on how a game “should” be, so take all advice with a grain of salt, but any advice is better than no advice!

3. Jump in! The only way to make any real progress as a designer is to design something. Your first game will not be your best, so if you have a favorite idea that you’d love to make a game out of, then you might want to save it for after you’ve got the hang of things. Don’t start with anything too ambitious or you’ll never finish. Something that can help is a design exercise such as the monthly Game Design Showdown at BGDF.com - a week long challenge to come up with an idea based on some specific restrictions (a required component or mechanism, a specific theme, etc).

There’s a lot of information out there, but the best advice that tends to get repeated over and over is this: Design a game you’d like to play. Don’t worry about marketing or publishing anything - that’s putting the cart before the horse. Just make a game you’d enjoy, and then play it with your friends and see if they enjoy it too. Once you get the hang of designing it’ll be easier to work in typical publishing concerns, and take on projects that you think will be more accessible or have a wider audience.

So that’s my advice. Designing games is not for everyone - but if you’re the type who finishes each game saying “that was cool, but it would be better if...” then maybe you’d enjoy coming up with your own game!

… but is that good advice? Who is this Seth Jaffee guy anyway, and why should we listen to him?

Fair enough - for reference, here are some of the games I’ve worked on:

Published games

Terra Prime (Designer) - Space exploration and colonization pickup/deliver game.

Homesteaders (Developer) - Resource management and auction game set in the old west.

Eminent Domain (Designer) - Role selection / Deck building game about building a space empire.

Belfort (Developer) - Worker Placement / Area Majority game about building a city in a light fantasy setting.

Brain Freeze (Designer) - iPad game (free download!) of speed and strategy.

Upcoming TMG titles (and status)

Kings of Air and Steam (Developer) - Steampunk themed pickup/deliver game (Art in final stages)

Ground Floor (Developer) - Economic game of entrepreneurship (Art sent to manufacturer. On Kickstarter right now!)

Eminent Domain: Escalation (Designer) - Expansion to Eminent Domain (Artwork started)

Belfort Expansion (Developer) - Expansion to Belfort (development wrapping up)

Unpublished games (and status) - you can read about these on my Game Design Blog if you like:

Alter Ego (Designer) - Cooperative deck building game of vigilante heroism (back on front burner)

Exhibit: Artifacts of the Ages (Designer) - Set collection game with a unique auction based on Liar’s Dice (about done)

Dice Works (Designer) - Real time dice drafting game (done - TMG is checking on pricing to see if it’s viable)

~ Seth Jaffee

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Eminent Domain | Designed by Seth Jaffee | Image Courtesy of William McConnell (via Nerdbloggers)

0 notes

Photo

Homesteaders | Designed by Seth Jaffee and Alex Rockwell | Image Courtesy of Roberto Méndez

0 notes

Quote

I think the methods and tricks for designing a card or board game are very similar to those used by novel writers, the main difference being that we game designers skip the hardest part: the actual writing.

~ Bruno Faidutti

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Jamaica | Designed by Malcolm Braff, Bruno Cathala, & Sebastien Pauchon | Image Courtesy of Cássio F. Lemos

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Senji | Designed by Bruno Cathala and Serge Laget | Image Courtesy of Mike Hulsebus

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Dice Town | Designed by Bruno Cathala and Ludovic Maublanc | Image Courtesy of Guido Gloor

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cyclades | Designed by Bruno Cathala and Ludovic Maublanc | Image Courtesy of Chris Norwood

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mr. Jack | Designed by Bruno Cathala and Ludovic Maublanc | Image Courtesy of Sandy S.

0 notes

Text

Bruno Cathala

Bruno Cathala designs games with some of my favorite mechanics: secret traitors and deduction (Mr. Jack has a permanent place in my top 50). He also designs party games (Dice Town), strategy games (Cyclades), Euro games... versatility is a hallmark of his. When he sent me his essay (which I attempted to translate as best I could from French) I was surprised at how introspective it was. Most designers discuss their craft and their love of game design; Cathala expounds on the meaning of life. Enjoy: this essay is special.

Why I Design Games

It has been nearly 10 years since my first game was published, but although I began designing games late in life, my creative muse had long been looking for a way to break free. Comics, music, songs, literature, painting; since childhood, I seriously attempted all of these disciplines, but it was ultimately through the creation of games that I managed to open that door to creativity.

My university curriculum involved rigorous mathematical and scientific training and left little room for improbable dreams. Throughout those years I would often wonder about the powerful, latent forces that tried to push me down the path of creation. That introspection has, over the years, led me to understand and accept the motivations behind my journey into game design.

There are three of them.

The first motivation is that I’m easily bored. As a child, I would get bored super easily. Really. Spending time with family and friends that I liked; during my studies; and also at work, I would be bored. In fact, in groups of people the feelings of boredom would be strongest. So, to avoid this, as far as I can remember, I would tell stories. I would make up stories where I was the improbable hero (although often unhappy) or where I was a neutral bystander. This tendency towards boredom was a wonderful catalyst for creating stories. And now, designing games allows me to focus those storytelling skills.

My second motivation for designing games is my shyness and fear of what others think. I liked the child that I was as well as the adult I have become (well…this remains to be seen fully). Yet I have always worried about what others thought of me. This fear, so deeply rooted, is one of the reasons why I try to put myself out there, publicly. When I go on stage at the theater or when one of my games appears in stores, I experience the reactions of dozens of people, people who I do not know personally. The theater audience is reacting to me; the game reviews and testimonials on the Internet are about my games. Paradoxically, this makes me even shyer. But creating games has become a way for me to communicate with many, many people whom I never would have dared to try and speak with otherwise.

Finally, my third motivation for designing games is my fear of death. I find the transience of life just… unbearable. A day does not go by that I don’t think about it. Creating games is a way around this, a way to leave a trace of myself behind. Yes, this is ridiculous, and clearly too ephemeral, but I will survive for at least some time. I can imagine that a few years after my death, strangers will still be sharing moments of fun with my games. I can imagine that two or three generations later, my descendants will have this trace of me, the great-grandfather they never knew, and that comforts me…at least a little! And besides, designing game rules is a way to ignore the "rules" in this game of life that society tells us we should be playing.

Creating games is ultimately fun, although it isn’t just a hobby that I’ve had some success with: it is a way of life. Game design holds the answers to my fears; it solves the problem I have with communicating with others; and it fulfills my need… to simply be loved.

~ Bruno Cathala

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Shadows over Camelot | Designed by Bruno Cathala and Serge Laget | Image Courtesy of Chris Norwood

10 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I do not expect to ever make money from this.

~ Matt Riddle

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Elder Sign | Designed by Richard Launius and Kevin Wilson | Image Courtesy of Chris Kirkman

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richard Launius

Richard Launius is the king of theme. From the eldritch horrors of the Cthulu mythos to the pulp drenched world of the noir detective to hellish marauding dragons, his games are soaked in theme. You'll never hear the words "pasted on theme" in regards to his designs. Heck, he has a game called Pirates Vs. Dinosaurs! Richard shares his thoughts on game design below and how his love of adventure and storytelling influence every aspect of his work.

Why I Design Games

For me, game design has been a creative way of life since I was in Junior High (and trust me, that was a long time ago). Being artistic, designing games offered a creative process that went beyond drawing, painting, or sculpting – all things I still enjoy doing today. But game design has always been even more rewarding to me as it expands my artistic skills and my imagination in a unique way: the creation of a story that comes to life for players (and me) to enjoy.

One of the rewarding things I discovered was that when a game is designed well (especially the adventure oriented games that I enjoy designing and playing), each game session can bring an ever–changing story to the players that outweighs winning or losing. The one thing that always pushed me to design, even from my very first projects when I was maybe 12 or 13 years old, was the desire to create a world that could be enjoyed by the players. Maybe it is my overactive imagination, but one constant in my design process has been the desire to bring some adventure to life so that my friends and I can escape for a few hours.

My early game designs (and I do not think this has changed all that much over the years) usually stemmed from reading a book or watching a TV show or seeing a movie that I enjoyed, and then wanted to experience in a game. I would take the world from one of those stories and recreate it into a board game design. I can clearly remember one of the first really viable games I designed was based on the James Bond movies Goldfinger and Thunderball in which the players became agents of MI6 or the CIA working together to prevent a master villain from launching a devastating attack on the Britain or the United States. As many of my designs since, the James Bond game was cooperative and had the players moving all over the world encountering all types of chases, combat, henchmen, and sexy foils (hey, I was probably 14 or 15 at the time – could not leave the Bond women out of the game design). There were dangerous car chases, underwater combat, and high stakes gambling at Monte Carlo as the players gathered the Top Secrets they needed to discover the Master Villain’s plan and the location of his secret lair. The board, the cards, and even tokens were all hand drawn, painted, and constructed out of thick cardboard. It was an artist project that took me months to finalize – a project (like most since) that I sincerely enjoyed doing. Not only was making the game fun and challenging, but playing it with my friends was even more fun, encouraging me to continue to create games as a hobby through High School and College. Along with playing sports, designing and playing games became my primary hobby.

Simply put, I design games to create a story for players to become heroes and heroines in, if only for a brief time. Whether the design is Arkham Horror, Defenders of the Realm, Elder Sign, Pirates VS Dinosaurs, or Ace Detective, my central design focus is to create a game that enables the player’s imaginations to soar; to expand and create a story within whatever world the game is set in; and to ensure that the playing experience is so memorable that winning or losing becomes secondary.

The simple answer as to why I design games is that it is a creative process that I truly enjoy in many forms. I like forming the initial idea; I like creating the mechanics to best support the game theme; I like how designing games expands my imagination and utilizes my artist skills; and I like playing my games, experiencing the adventure world created for myself (both in solitaire play and with friends). After all, how often in real day to day life do we get to face eldritch horrors and save the world, or wield a sword in an epic battle against orcs and dragons, or to fight for survival (and perhaps the survival of all mankind) on a planet in a galaxy far from earth and still make it home in time for dinner?

That is why I create games, and I believe that is why players who enjoy my game designs play my games.

3 notes

·

View notes