Photo

For the Architectural Review

Bass Coast Farmhouse in Victoria, Australia by John Wardle Architects

Calvin Po

For the architectural profession, building on the unceded lands of Indigenous people is a conflicting proposition, yet one that is almost inevitable for architects in Australia. Bass Coast Farmhouse, by John Wardle Architects, is one such project, built on former farmland among coastal heath reserves off the Bass Strait in Victoria. As they do with all their projects, the architects acknowledge the Traditional Owners, in this case the Boonwurrung people of the Kulin Nation.

Between the role of the architect, duty to their client, and wider questions of postcolonial ethics, these tensions permeate the house’s character and its distinctive relationship to the land. The Kulin Nation’s Tanderrum ceremony extends to outsiders a welcome to Country conditional on honouring the land and its intertwined relationships with its people: ‘The land ... is our mother. These cliffs are like our cathedrals, this is our church.’ On this sacral land, the architect’s exploration of ‘the nature of building on terra firma’ is not just an architectural fantasy, but a reflection of this quandary, and rejection of colonial myths of terra nullius – the land is not a blank slate.

From ecological footprint to the architectonics, this sensitivity is omnipresent. The house is entirely off-grid and the construction is largely prefabricated to minimise onsite waste and disturbance. The house sits gingerly on the ridge of a dune, making only the necessary contact with the ground. It is then cantilevered as the dune falls beneath the house. The cantilever, with its barn-like void and its suspended walkway, evokes an archaeological shelter, spanning over and shielding artefacts, and framing them for display. To enter the house, a set of stairs descends from this walkway as if down into geological strata of times past.

As for what is being sheltered – the dune and a scattering of stones – they too become imbued with new significance. After centuries of European colonisation, few traces of Boonwurrung heritage remain. It is the land itself, and the Boonwurrung people’s intergenerational custodianship of it, which is left to be protected. A critical part of the project is repairing parts of the site degraded by modern agricultural extraction, with a specialist advising on a massive replanting project for carefully restoring indigenous grass, shrub, and tree species. In contrast with the landscape, the house’s timber cladding (already silvering in the antipodean sun) and the corrugated galvanised steel roof seem to acknowledge its fleeting presence, relative to the long histories of the Kulin Nation.

The house is the antithesis of being ‘monarch of all [it] surveys’, to quote William Cowper’s poem on Alexander Selkirk, the British castaway in the Pacific. The Anglocentric ideals of Capability Brown’s Picturesque landscapes, where the earth itself is reshaped for the pleasure of the house’s gaze, are rejected. All the outward-facing windows, including the living room’s picture window, can be shuttered at a moment’s notice. For a house surrounded by expanses of nature and the coast, it is surprisingly introspective, with its primary aspect oriented around the central courtyard. The house is also extensive for a single-storey family home, with beds and bunks in polished, timber-panelled rooms, accommodating over a dozen people. But rather than bearing down on the terrain or asserting its panoramic dominion, the house seems to recognise that the views and the land are on loan, not owned.

John Wardle Architects, with its recently inaugurated Reconciliation Action Plan, joins others in Australia in re-evaluating their relationship with First Nations. But in the end, the impact a private house can have on reconciliation is limited. As Carolyn Briggs, a senior Boonwurrung elder, once reflected, ‘I’m always trying to find markers that inform me that we still have a part in this place. ... I think it would be amazing if you can start to read the land and wonder about the history of the people who lived and died before we were here. Hopefully one day you’ll know it. But we can’t see that now in the built environment.’

Link to original article here.

#writing#journalism#architectural writing#architectural criticism#critique#architectural journalism#New Architecture Writers#building#building study#building review#architecture#Architectural Review#John Wardle Architects

1 note

·

View note

Photo

An exhibition/pavilion review:

Ringing Hollow: A Review of Black Chapel, the 2022 Serpentine Pavilion

Calvin Po

It’s perhaps an unfortunate coincidence that on my way to this year’s Serpentine Pavilion, Black Chapel, designed by Chicago-based artist Theaster Gates, I had a rather more spiritual experience when I passed by a group of street preachers on the square next to Speaker's Corner. With their Union Jack bunting draped all around their assembly, placards with JESUS IS LORD, large banners of the English flag adorned a patriotic lion and names of the all the London boroughs proudly proclaiming LONDON SHALL BE SAVED. Puncturing through even my atheistic, bemused scepticism, the blaring music and odd bursts of song had a patriotic, messianic energy that was electric. By the time I got to the Chapel I came to see, it had simply been upstaged.

Pavilions have often mattered more for the reason they are built, than the actual functions they house. From completing the composition of a Picturesque landscape, to Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion itself becoming a manifesto, the purpose of pavilions often exists beyond the building itself. In the case of the Serpentine Pavilion, it is more about the annual cycle of patronage by the London cultural elite as they pat the “emerging architect” of the year on the back. So I was intrigued when Gates claimed a loftier, more sacred ambition of creating a ‘Chapel’, a “sanctuary for reflection, refuge and conviviality”, for “contemplation and convening”, on top of the usual purpose as a place to sit and buy an expensive coffee.

The pavilion’s imposing 10.7m high cylindrical form, clad in all-black timber has an immediate presence as I approach. Gates claims the form references inspirations as eclectic as “Musgum mud huts of Cameroon, the Kasubi Tombs of Kampala, Uganda [...] the sacred forms of Hungarian round churches and the ring shouts, voodoo circles and roda de capoeira witnessed in the sacred practices of the African diaspora.” Perhaps the subtlety of these references is lost on me, but the Pavilion mostly evokes an industrial structure, like a water tank or gasometer, especially with its external ridges of timber battens and internal ribs of timber and metal composite trusses. Yet despite the grand gesture of an open oculus in the roof, letting light into the inky, voluminous interior, it fails to move me in that transcendental way that even a modest place of worship can.

Is it perhaps the quality of the execution? Serpentine Pavilions are often put together on hasty timescales, with six months from conception to completion. Little details give this away: boards of the decking and cladding not quite lining up, the black-stained timber a bargain basement imitation of yakisugi (Japanese technique of timber charring). Perhaps this can be forgiven of a non-permanent structure: in a nod to sustainability credentials, this year the designers have taken care to ensure the structure is demountable, down to the reusable, precast concrete foundations. But seeing that the Pavilions are almost always auctioned off to recoup the costs and relocated to the grounds of private collectors and galleries, this seems more a convenient commercial expediency, than an environmental one. Perhaps it is difficult to be spiritually moved by a structure that is sold and delivered like a commodity, with little rootedness in its physical and congregational geographies.

Or could it be the atmosphere, a lack of drama? One of Gate’s flourishes, such as his seven silvery ‘Tar Paintings’ that are suspended in the inside walls of the space like abstract icons, are a nod to his father’s trade as a roofer, and Rothko’s chapel in Houston. Yet these self-referential gestures seem lost on the throngs of sun-seeking Londoners taking brief shelter from the heat and wilted grass, with hardly anyone giving them a second glance. Most seemed more interested in the shade than symbolism. For a project that also emphasises “the sonic and the silent”, the acoustic atmosphere of the space I found wanting, perhaps because of the sound that leaks out of the two full-height openings that puncture straight through the volume: its acoustic experience had neither the reverberant, sanctified silence once expects from a chapel, nor the sonic presence that the street preachers managed to carve out of a busy corner of a London with just their vocal chords. Instead, all I heard was the low chatter of visitors going about their own business. The Pavilion is being programmed with “sonic interventions” (read: music performances), and the jury is out on whether or not the Pavilion can serve as a suitable venue for sounds with a more explicit, ceremonial intentionality.

But perhaps the coup de grâce was the decision to relocate a bell from St Laurence, a now-demolished Catholic Church from Chicago’s South Side. Sited next to the entrance, it is to be “used to call, signal and announce performances and activations at the Pavilion throughout the summer.” Gates explains this decision as a way to highlight the “erasure of spaces of convening and spiritual communion in urban communities.” But now mounted on a minimal, rusty steel frame like an objet d’art, I can’t help but feel a cruel irony that a consecrated object that once used to convene a lost community is now used as a performative affectation for the amusement of London’s arts and cultural gentry. This perhaps exemplifies a deeper ethical issue at the heart of the Pavilion’s concept: narratives of collective worship, cherry-picked from across communities and cultures, are sanitised, secularised and aestheticised in a contemporary art wrapper for the tastes of the largely godless culture crowd. The curator’s spiels of a creating “hallowed chamber”, if anything ring hollow.

As I leave Hyde Park, I pass by again the assembly of street preachers, who have now moved on to delivering a sermon. Gates said of his Pavilion, “it is intended to be humble.” Yet I can’t help but but feel how much more these preachers have achieved, with so much less.

#writing#journalism#architecture#architectural writing#architectural criticism#critique#architectural journalism#New Architecture Writers#building#building study#building review#exhibition#exhibition review

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

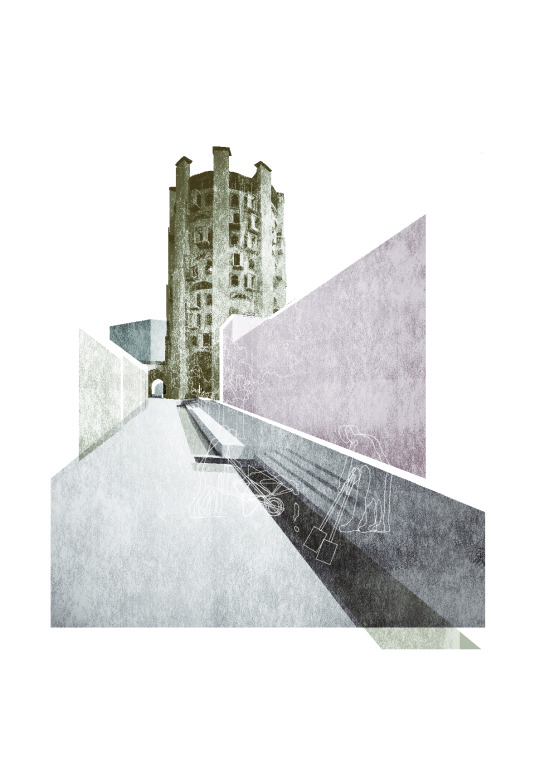

A building study:

Astronomical ambitions for anything but domestic life

Visiting Cosmic House, Charles Jencks’s house-museum

Calvin Po

Of the objections planners receive from neighbours, “the rationale for the house to become a museum is unclear,” is an unusual one. Cosmic House, the family home of the eminent late architectural theorist-designer Charles Jencks, is opening to the public as part of his bequest. Visitors will soon see the point is moot: was the house ever not a museum?

Situated on a row of uniform 1840s townhouses near Holland Park Station in London, there has been a hint of oddity with this property ever since it was redesigned by Jencks in the late 1970s. From the street, with its keyhole-like dormer windows, its two doorknobs on one door, and a ‘trompe l’oeil’ intercom mirroring the real one, these details establish its notoriety in the conservation area. It is surprising that they even let it be built. Indeed, Town Hall archives reveal a circuitous journey, with neighbourhood drama, enforcement threats, and retroactive permission needed. But built it has been, and four decades on, it has reignited the chatter of NIMBYs in Ladbroke Grove.

Despite protestations from neighbours that it is “inappropriate to have a museum in this quiet street”, W11 in the 1970s was not quite the smart postcode it is today: Peter Rachman’s slums were nearby, on the cusp of gentrification. The 1970s too were a pivotal moment for Jencks, in the midst of writing his seminal book, The Language of Post-Modern Architecture, while the house was conceived. Working with architect Terry Farrell, every detail of the house is an inhabitable exhibition of the book’s contents, charting architecture’s departure from rational, industrial modernism, like that of post-war council estates, to reviving symbolism, cultural reference, and ironic wit, in what Jencks was central to defining as the Post-Modern movement.

This 1970s zeitgeist not only infused the House’s architectural approach, but its symbolic content. The scientific discoveries of the age, with the space race recontextualising our place in the galaxy, and subatomic physics redefining the fabric of the universe, permeate the spiritual outlook of the house, like an ashram for the teachings of Carl Sagan. From the hall, a “cosmic oval” dome lays out an esoteric cosmology on the ceiling. Ground floor rooms are themed on the four seasons, a ‘winter’ sitting room, garden room for ‘spring’, a ‘summer’ dining room, an ‘Indian summer’ kitchen, and an ‘autumn’ pantry. The Solar Stair, at the centre, features celestial bodies embedded into orbital handrails and fifty-two steps for weeks in a year. Its symbolism and intentionality are gluttonous and maximal. Yet it has faced critics from its conception: Mr Barker, a neighbour, complained of Jencks’s “rather dubious creative whims”. From an oil crisis-stricken 1970s to today’s inflationary panic, the house’s excess continues to freshly divide opinion.

Despite this, the materials themselves are humble. Neighbours seeking interiors inspiration for mid-Victorian features and Farrow & Ball heritage colours will be disappointed. Blocky fireplaces in the ‘winter’ and ‘spring’ rooms, designed by Michael Graves, are made of marbleised fibreboard painted in improbable colours; seams, screws, and chipped paint just about visible, flirtatiously relishing in its fakery and dismissing Modernism’s “honesty of materials''. Games with scale and orientation amplify the artifice: Jencks’s miniature cityscape library houses books in building-shaped shelves, while the infamous jacuzzi tub upends a Baroque dome. Yet the jacuzzi was rarely used due to its impracticality, and the ornamental embellishments trap dirt in the uncleanable nooks: the house was not designed with the banalities of domestic life in mind.

Indeed, family life in an architectural showcase grows old quickly. While Lily, the daughter and herself an architect, is managing the house-museum trust, the son “wants nothing to do with it” explained Edwin Heathcote, the house’s ‘keeper of meaning’ and a family friend. Maggie, Jencks’s wife, too seemed lukewarm on the house’s astronomical design aspirations; her study and dresser are left relatively unembellished. As Heathcote recalled, “the symbolism stopped at her door.”

As the house transforms into a cultural institution, the pretence it was first and foremost a domestic space drops. Even so, the local planners disagree, imposing conditions limiting the opening hours and occupancy in light of its residential use and context. As for the neighbours, the saga continues, and the jury is out on how this house-museum might affect their house prices.

#writing#journalism#architectural writing#architectural criticism#critique#architectural journalism#New Architecture Writers#building#building study#building review#architecture

1 note

·

View note

Photo

youtube

youtube

youtube

youtube

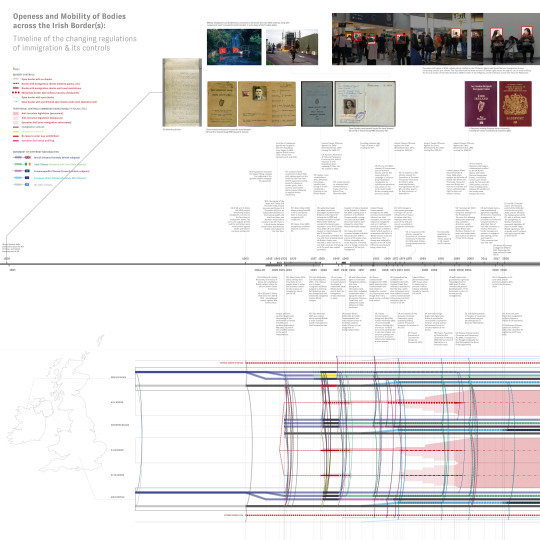

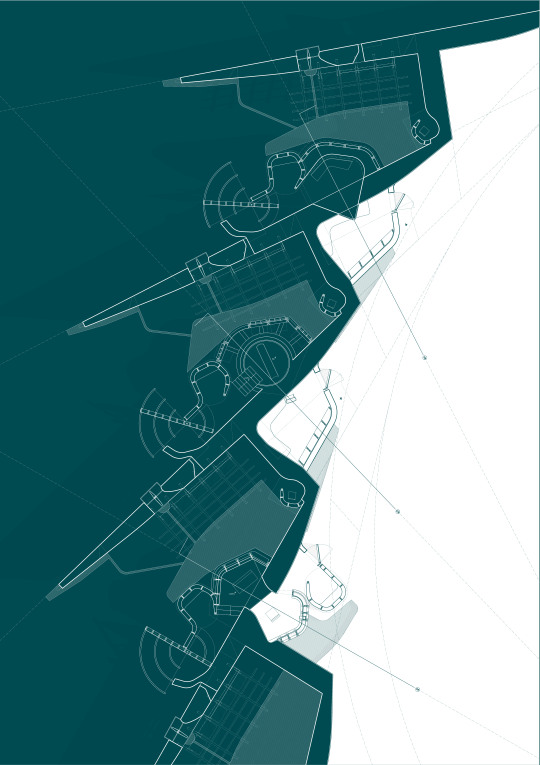

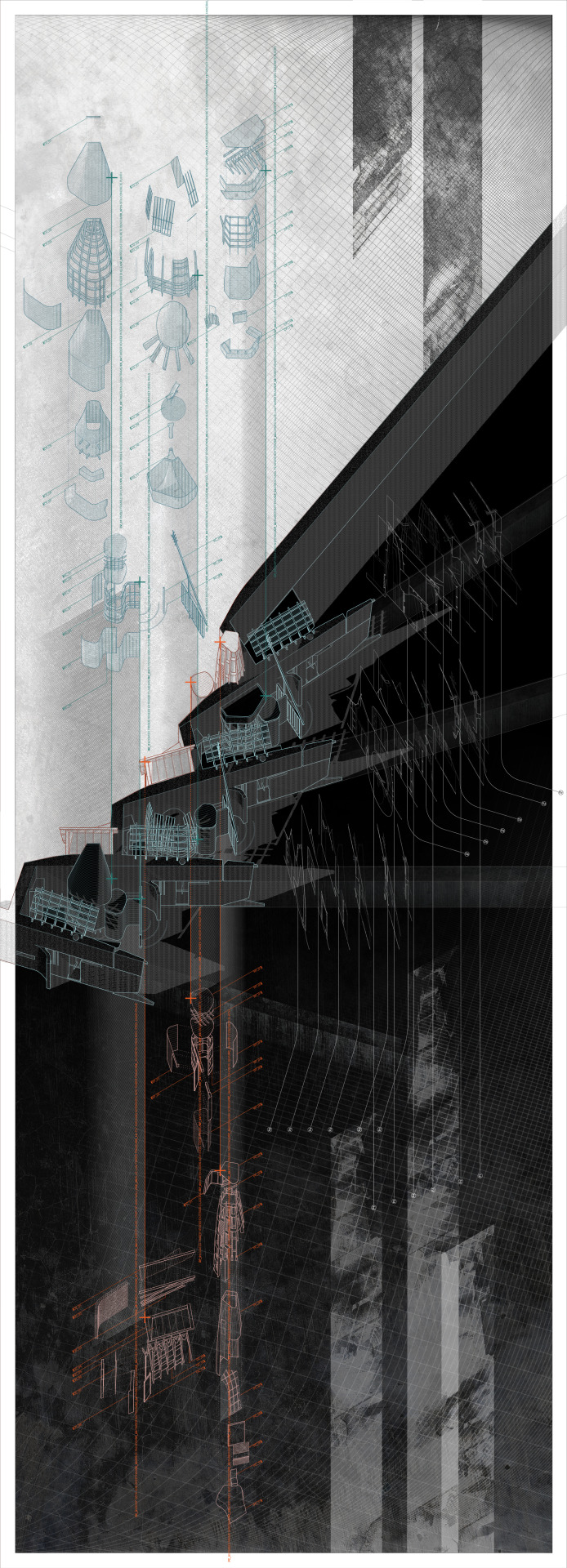

A Body, A Borderland: the Biopolitics of the Irish Border(s), 2019-2020 The Irish border is a political question, but also a spatial one.

Cartography is an instrument of power. The border spatialises state power, and in Ireland, embodies long-running conflicts over self-determination. Despite its openness, it remains a limit of jurisdiction, and for marginalised bodies, such as women seeking abortions or transgender people, a source of systemic violence. The Irish border's spatial site is not only on the map, the territory, but in fact is carried by each body.

“Sovereign territory” is idealised fiction. The 1924 Irish Boundary Commission’s failed attempt to redraw the border demonstrably exemplified problematics of dividing interconnected peoples, economies, geographies, with a line. Mapping Ireland was inherently colonial, and the Irish Boundary Commission’s arbitrary interpretation of “wishes of inhabitants” continues legacies of the cartographic gaze’s power, vested in few, imposed on bodies of many.

When territory as an idea engenders violence, this project proposes deterritorialising sovereignty, basing it on the space of an individual body as a provocation. In Derry/Londonderry, where its bipartisan names are part of the conflict, what becomes of urban life if our association with a state is not based on territorial coincidence, but the body’s choice? May urban flows of people become new maps of the nation, with architecture as the boundary treaty? When the nation is built on the body, how may the body rebuild our understanding of the conflict, and the nation?

This research was featured as an article on e-Flux, Inscribing Borders on Bodies. This work was also part of a Feminist Constitutions symposium on using methods of arts and design in reimagining new processes of 'constitution-ing'. Calvin has also spoken at the London Migration Film Festival about ideas from this work.

#Youtube#cartography#geography#research architecture#forensic architecture#architectural association#architecture theory#archtecture#politics#conflict#nationalism#unionism#territory#irish border#borders#e-flux#writing#critical theory

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

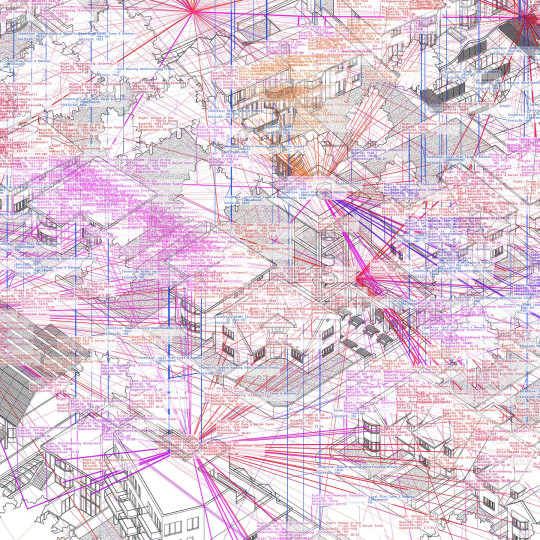

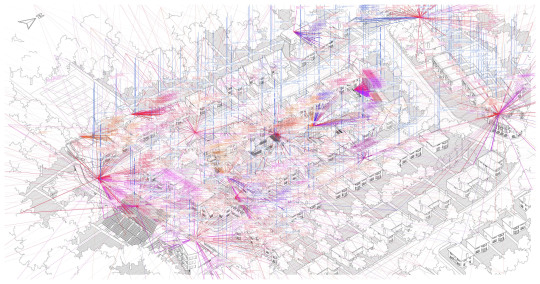

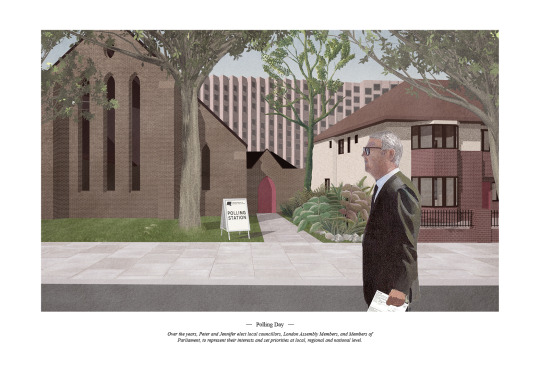

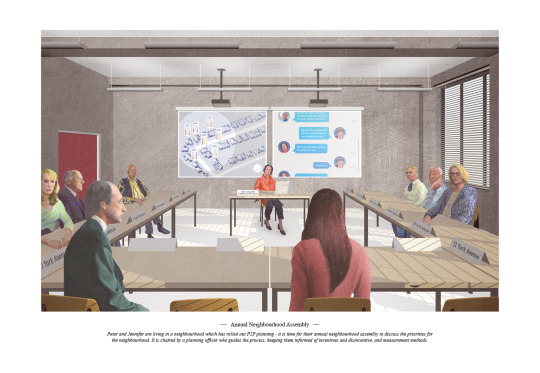

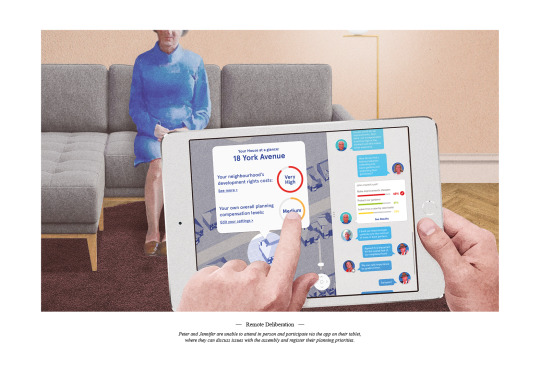

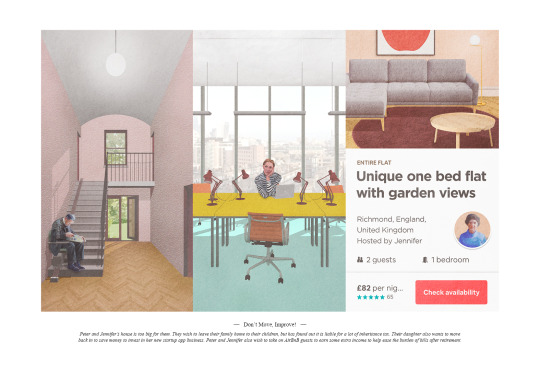

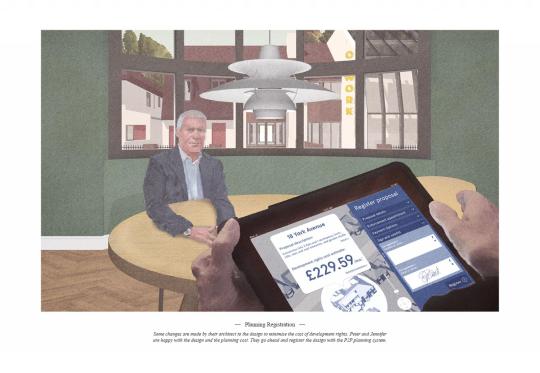

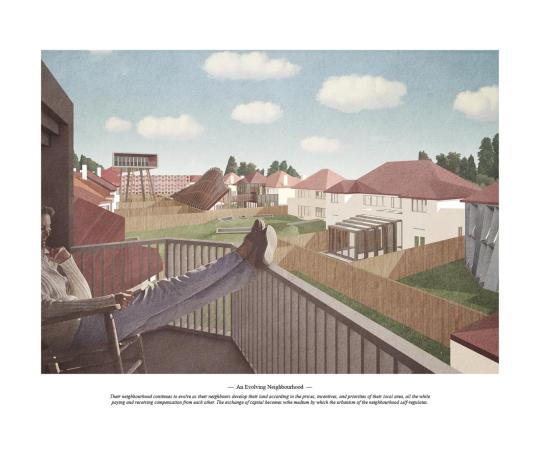

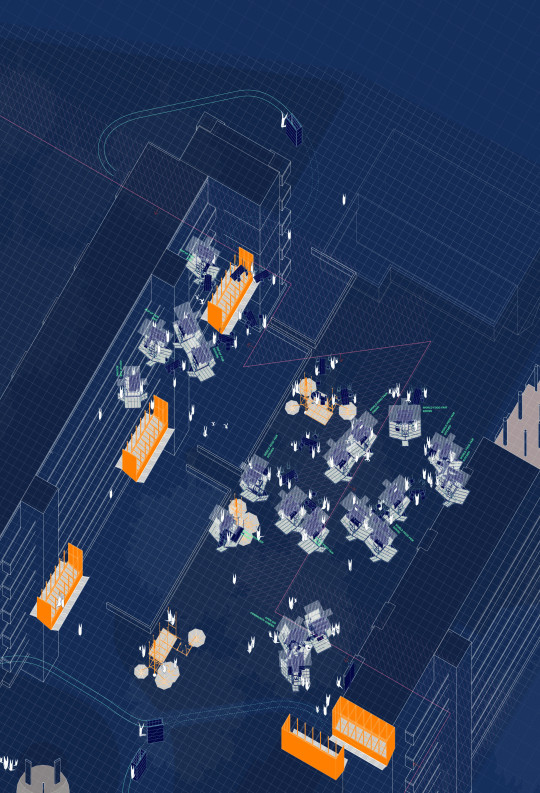

P2P Planning, 2018-2019

The current English planning system is a 20th century governance model, based on centralised state control, and largely shaped and justified by the exceptional circumstances of WW2′s destruction. P2P Planning imagines how development of land can be governed for the 21st century, while reinstating the common law principle where land ownership confers the ‘right to free use and enjoyment’, as along as it doesn’t prejudice the ‘free use and enjoyment’ of others.

Based on Coase’s theorem on externalities, where negotiated compensation allows the most efficient allocation of land uses, and blockchain-based automation of nuisance law, P2P planning regulates development through networks of peer-to-peer relations modelled as a free market of development rights, represented by the trading of development tokens. Individual householders freely set compensation rates for each planning issue, and people are conferred development rights tokens for long as this compensation is paid. The price-setting process is shaped by safeguards, such as deliberative neighbourhood assemblies, and various incentives, and non-human negotiating entities, based on parametricised priorities to be set by existing systems of elected representatives on a local, regional and national level. Critically, the control of ‘token supply’ through taxation of compensation rates and exchange rates applies a central-bank analogy to managing urban development by controlling the ‘money supply’ of development rights tokens. P2P Planning aims to return agency in decision-making over the built environment to the individual, while ensuring this agency is exercised accountable to collective interest, with indirect stewardship from the state.

This project uses a suburban development in London to test this system, to speculate how planning behaviours, architectural possibility, and our neighbourhoods might evolve under a system of peer-to-peer planning.

#architecture#planning#urban design#urban planning#urbanism#architectural drawing#illustration#drawing#data#architectural association#blockchain#p2p#politics#legislation#parametric#parametric design#render#architecture student#studio#design

1 note

·

View note

Photo

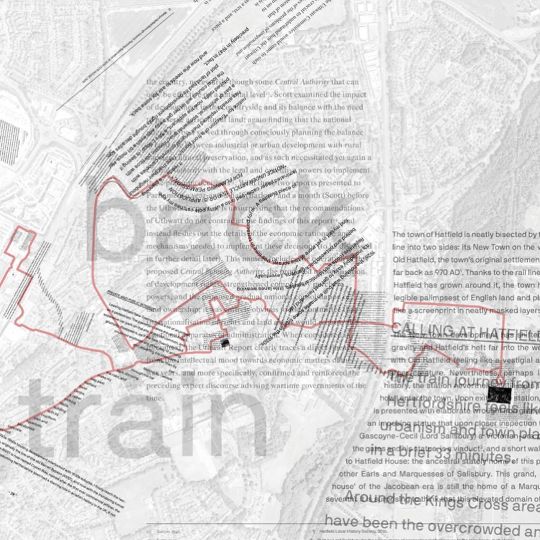

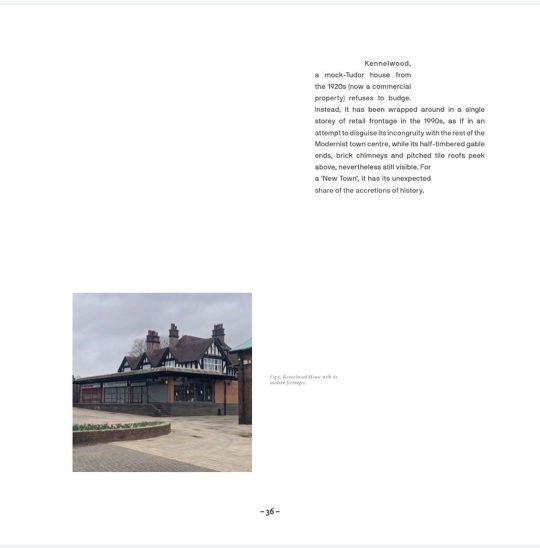

Planning a Town and a Country in a Hundred and Eighty Pages, December 2020-2021

This paper explores how one expert report written in 1942, the Uthwatt Committee’s report, underpinned the rebuilding of Britain’s town and country, and redefined the relationship between the state, the citizen, and the land, marking the genesis of the modern planning system. Framed as a walk through Hatfield, the thesis explores the interplay between architectural writing and the text of government and bureaucracy, tracing the legacies of this report imprinted in Hatfield’s townscape.

This paper was the winner of the Architectural Association's Dennis Sharp Prize for writing in 2020. This paper was also shortlisted for the RIBA President's Awards for Research 2021.

The full paper is available below:

#writing#architecture#architectural history#Architectural Theory#planning#urbanism#architectural association

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Border-Bound: The Belfast Conundrum, published in AArchitecture no. 37

(the Architectural Association’s student publication)

While the irreconcilability of Brexit and the Belfast Agreement was barely discussed as an issue during the referendum campaign in 2016, it has since become a lynchpin around which the politics of the UK, Ireland and the EU have revolved. With each party pursuing individual agendas and strategising in the shifting political sands, the people and the ‘peace’ in Northern Ireland have become bargaining chips and a proxy battleground for the wider geopolitical tussle between larger powers and the divided factions within them.

For the walls that marr Belfast’s townscape, called ‘peace lines’ or ‘peace walls’, there is an ironic paradox inherent in their name — how can such militarised, defensive architecture ever create a genuine peace? Unlike the overwhelming resentment of the Berlin Wall by communities on both sides, the situation in Belfast is more ambiguous, with a growing substantial minority wishing for the walls to remain. Though intentions for segregation were originally to keep feuding communities safe from one other, there is also a subtext of containing the minority and obscuring the Other; they have served as architectural enablers of mutual suspicion, isolation and irreconciliation. While the Northern Ireland Executive has a target of removing all peace walls by 2023, there is little prospect of progress. With a substantial number of peace walls actually built after the paramilitary ceasefire and the Belfast Agreement, they illustrate a complicated and incomplete ‘peace’ the province is just about holding together. The combination of a sectarian urbanism in its walled cities with an absence of any wall on the Irish border forms the territorial oxymoron on which Northern Irish ‘peace’ is built, and its delicate illusion may be shattered. Seeking a substitute form of cognitive dissonance and constructive ambiguity to appease all parties again, after the upheaval of Brexit, could become the new struggle of a generation.

Full text available here

#writing#ireland#irish border#northern ireland#brexit#uk#good friday agreement#belfast#european union#eu#europe#publication#architectural association#architectural writing#politics#archtecture#graphic design#Publication Design

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

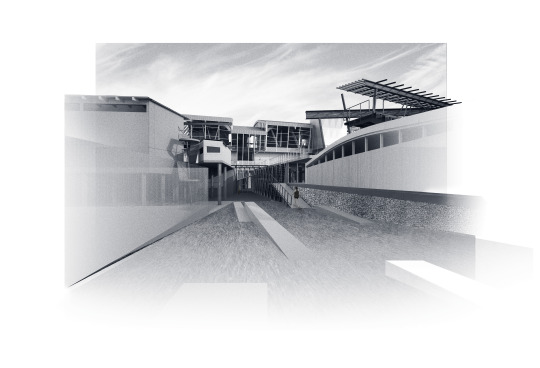

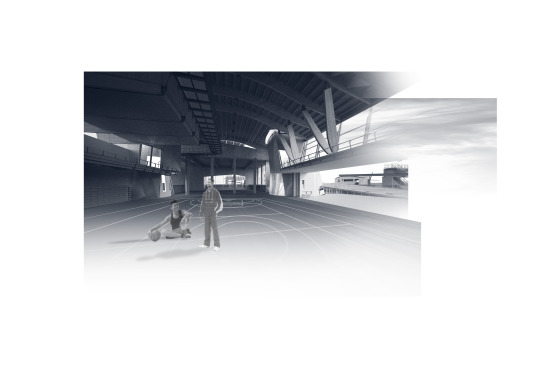

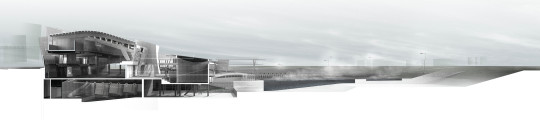

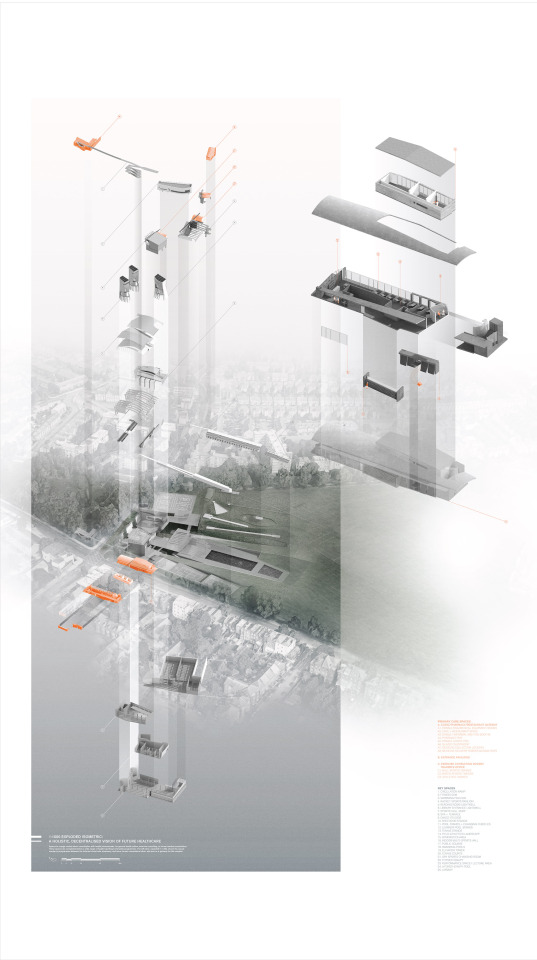

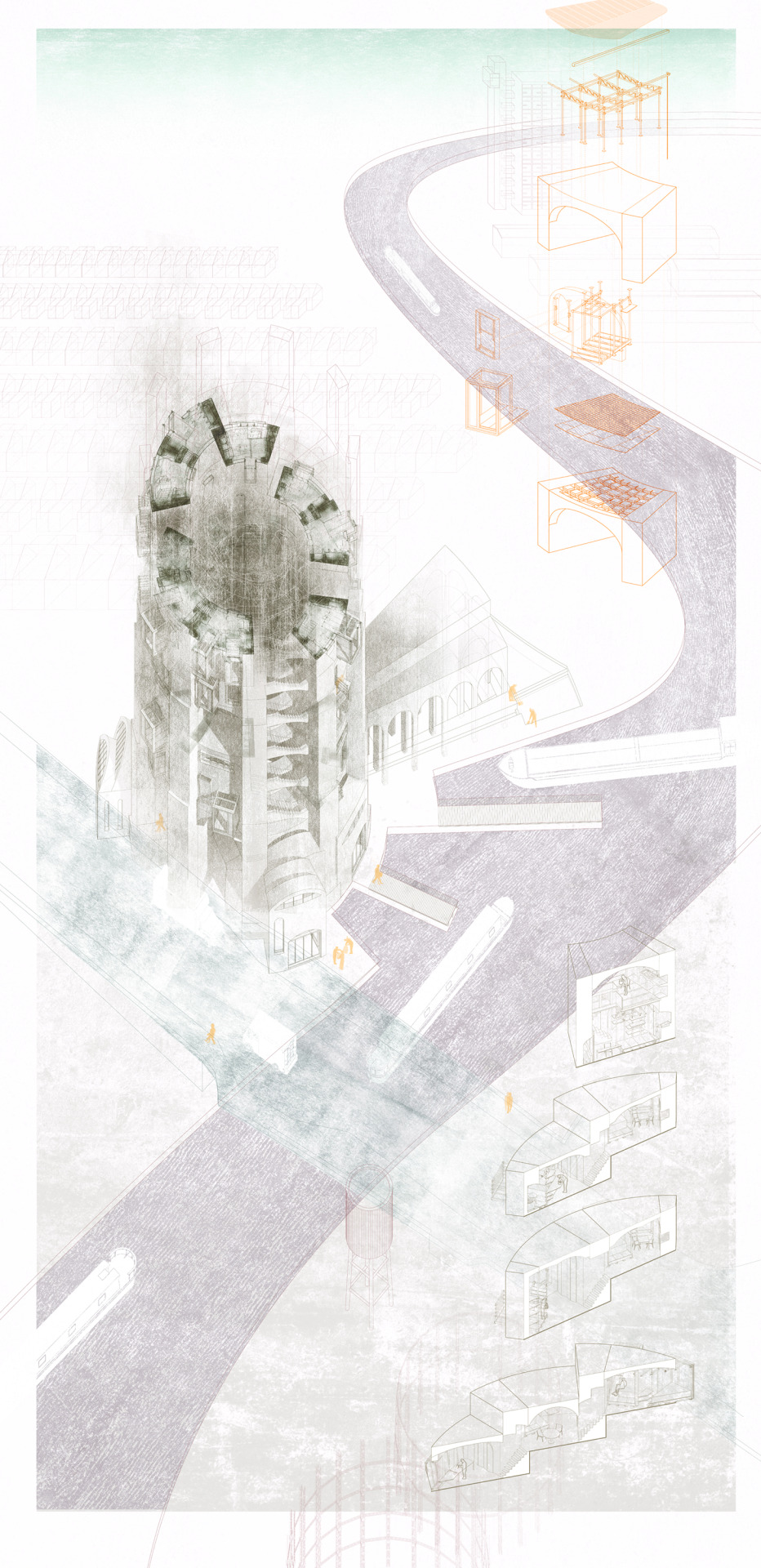

Peckham Health Common, May 2016

Peckham Health Common re-examines the contemporary relevance of ‘common land’ as a urban and social buffer. Sited strategically on the northern edge of Peckham Rye common, an intersection of diverse communities, it addresses health as the emerging common concern for all the communities of Peckham.

With obesity and cardiovascular disease a primary health problem of the area, this preventable problem strains an already overburdened public healthcare system. The building programme’s position within the existing healthcare infrastructure occupies the niche of the proactive, preventative approach, serving as a buffer, or ‘architectural triage’, preventing and intercepting emerging health concerns before they are allowed to deteriorate and add burden to GPs and A&E.

Drawing upon Peckham’s radical history in alternative healthcare approaches, a positive health approach is re-emerging as relevant since the 1926 Peckham Experiment. Peckham Health Common reinterprets its holistic, community and lifestyle-integrated approach in the context of healthcare’s present and future, by combining medicine, exercise, counselling, nutrition, culture, landscape and community life in a unifying space for the neighbourhood.

The project reinterprets Peckham’s rich urban model of the eclectic and vibrant high street with its complex, subdivided shop-fronts to express the breadth of the experience of health. By embracing a holistic mix of programmes, this multifaceted approach allows overlap and interaction between wide-ranging health activities and acknowledges health as not only an absence of illness but a consequence of all aspects of living.

This project is the winner of the Judge’s Special Prize in the Architects for Health Student Design Awards 2016.

#archtecture#health#community#peckham#landscape#landscape architecture#nhs#peckham experiment#sports#exercise

1 note

·

View note

Photo

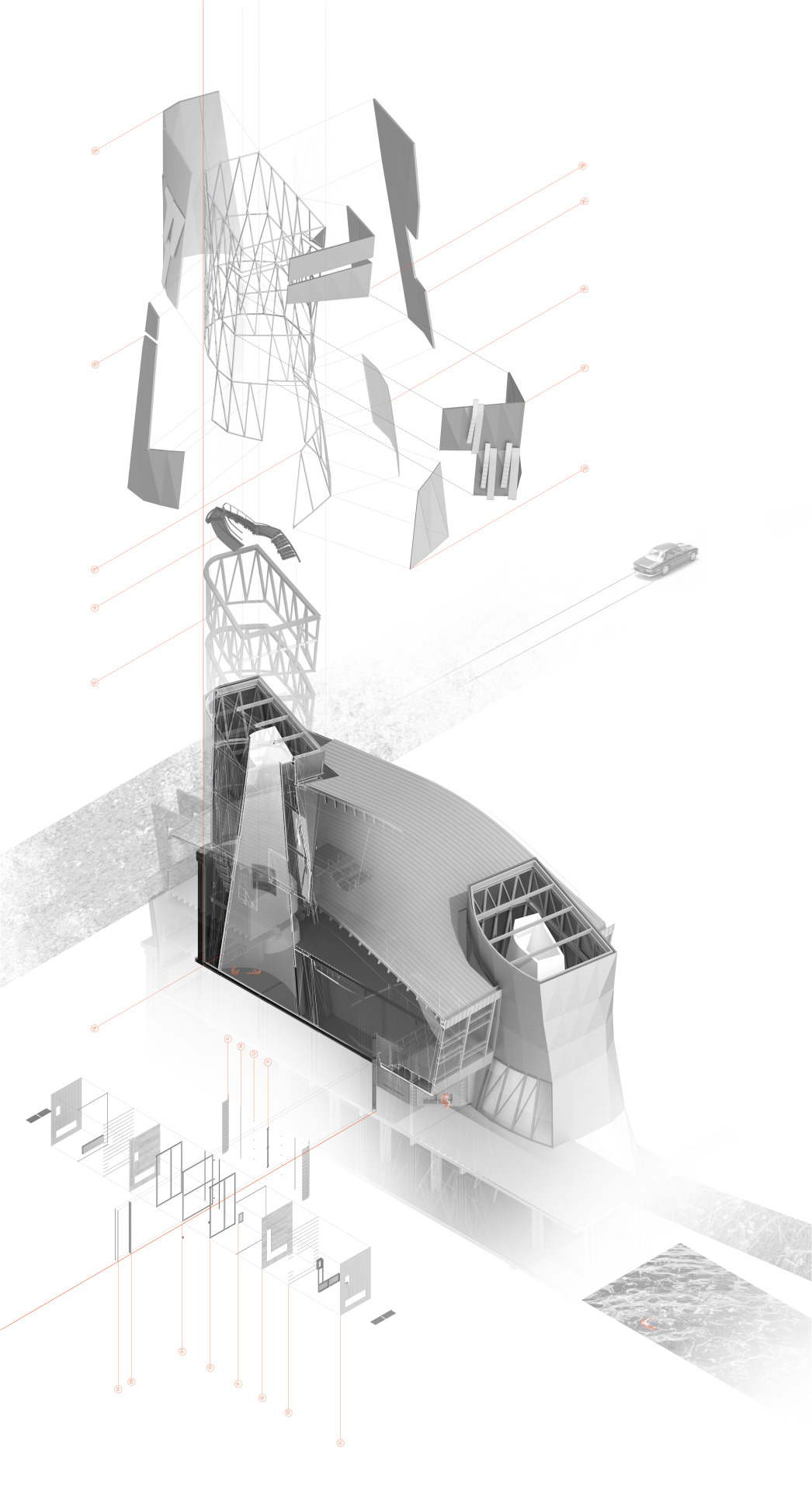

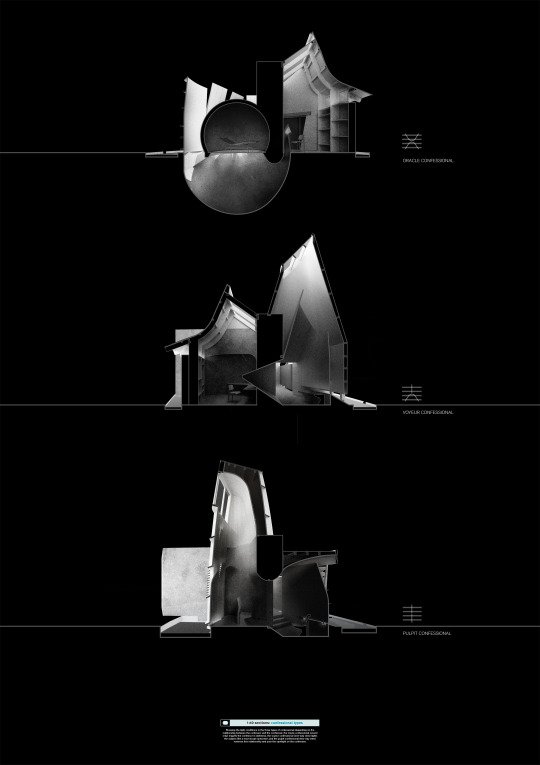

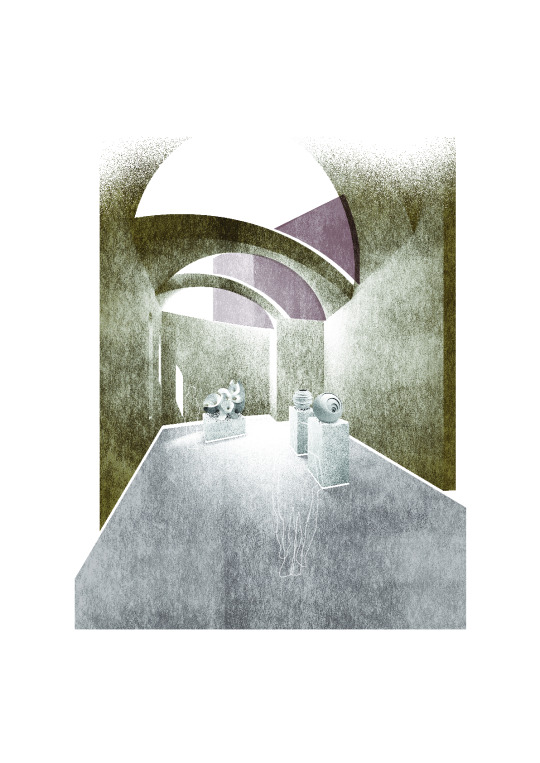

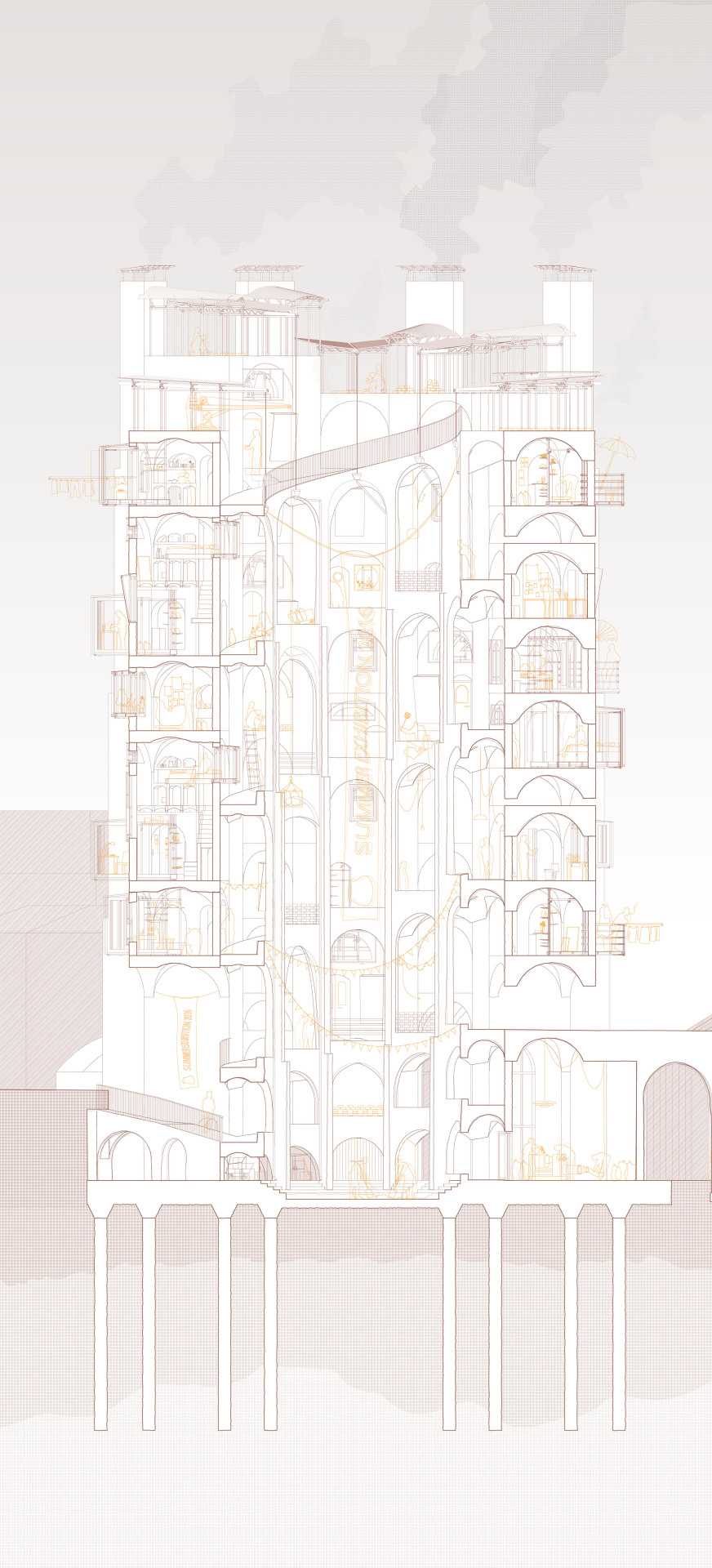

Confessionals: Remedies of Rite, September 2015

This project speculates on the typology of healthcare architecture in an imminent post-antibiotic future drawing upon the rich history of healthcare and its relationship to architecture and religion. The wall is revived as a quarantine device and the confessional is used as a spatial device to buffer and mediate between the infected and the clinician.

These intimate spaces with specific lighting conditions reflect the palliative, psychological side of the relationship between doctor and patient and the direction of the ‘medical gaze’, a more spiritual reinterpretation of the tendency of observation and monitoring in healthcare space.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

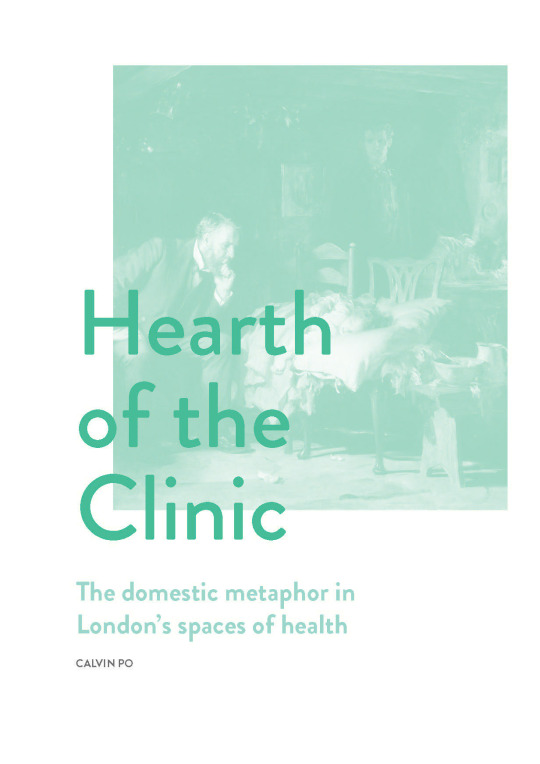

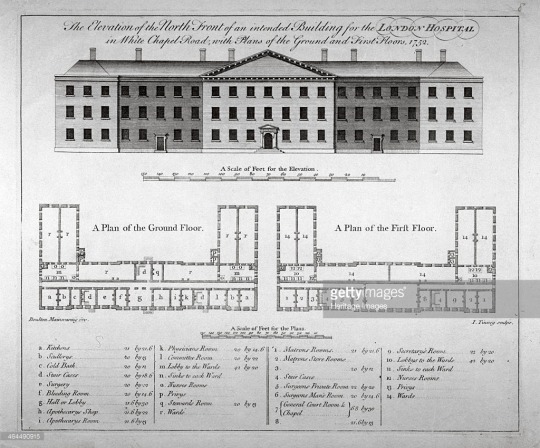

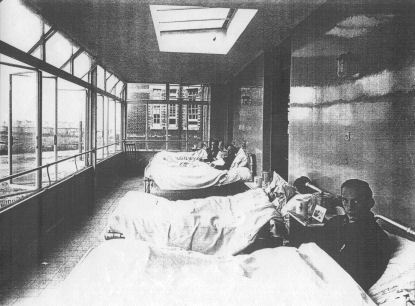

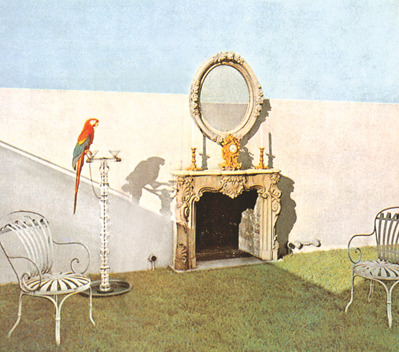

Hearth of the Clinic: The domestic metaphor in London’s spaces of health, January 2016

A critical analysis of the relationship between spaces of health and domesticity through historical and built examples of healthcare and health-related spaces of London. An excerpt below:

“Upon entering Maggie’s Centre under the looming shadow of Charing Cross Hospital in London, the orange wall’s protective embrace unwinds around some familiar spaces: the kitchen, the fireplace, the plush sofas (fig.1); there is an unmistakable air of ‘home’. This and other Maggie’s Centres are challenging institutional preconceptions of healthcare spaces, by reincorporating the home’s qualities of comfort and emotional well-being. They are flagship examples, along with the rise of home births, home social care and home deaths in the re-emerging discourse of domesticity’s role in health, challenging the Machine-age narrative of “modern man is born in hospital and dies in hospital” (Colomina 230).

Yet the history of health spaces and home are intertwined, encapsulated by ‘The Doctor’ by Sir Luke Fildes (fig.2): a sickly child strewn over dining chairs is overlooked by a solemn physician in the Victorian cottage’s rustic atmosphere. This could not be further from our contemporary preconceptions of spaces for healthcare. The number of bed spaces of the hospital is a politically-charged metric for its size and performance, yet its connotations are antithetical to the bed’s role in the home. Along with identical rows of chairs, neutral interiors, and endless corridors, these spaces have come to define ‘clinical’ as pejorative. Domesticity has become a subverted metaphor.

Health spaces have evolved with attitudes towards health and medical knowledge (fig.3), but for most of history, home was the site for healthcare. Dedicated healthcare spaces themselves were tussled between science, spirituality, and state. The juncture, characterised by Michel Foucault, was the development of ‘the medical gaze’. Foucault correlated the Enlightenment attitude that “one must [...] make science ocular” (88) with the resultant restructuring of knowledge around empiricism and observation, shifting away from medieval conjecture and backed by the credibility of the emerging institution of professional medicine. The doctor’s gaze became imbued with powers of institution-backed decision-making, receptiveness to deviance, and calculation of risk (Foucault 89). Patients shifted from individuals to corporeal collections of signs of disease, of deviance in need of correction. An attitude of negative, corrective health emerged, and architecture adapted to follow, becoming ‘machines for health’ for processing patients.

This dissertation, through primarily London-based examples, firstly retraces the hospital’s developments that culminated in ‘machines for health’ and its unravelling relationship with domesticity over this period. Through subsequent examination of exceptional cases, where home was embraced as an organisational metaphor in the Peckham Experiment, a site for healthcare by Finsbury council, and an antidote to the machine-hospital by the Maggie’s Centre, this dissertation aims to re-examine domesticity’s contemporary relevance in the architectural discourse of spaces for health.”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

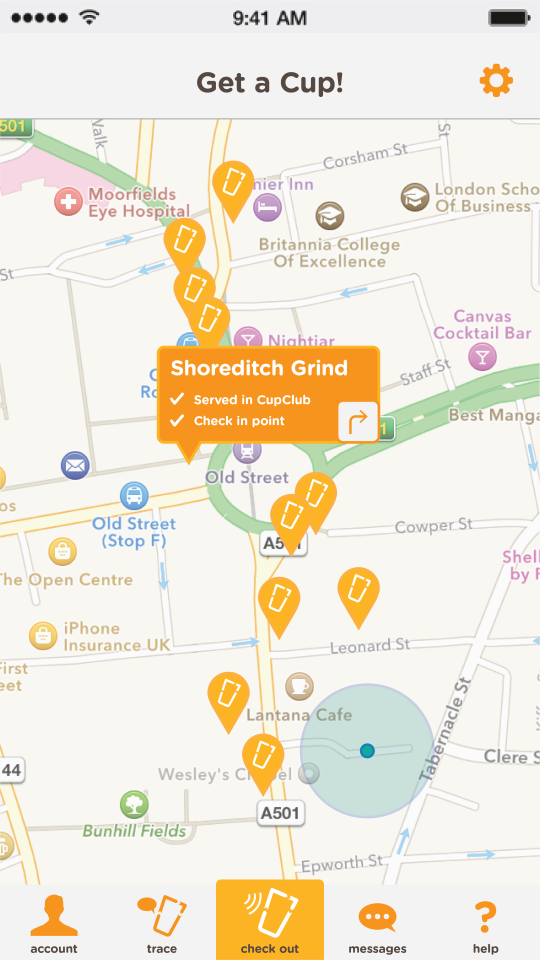

CupClub with Studio [D] Tale, August 2015

CupClub is a circular infrastructure startup that aims to be the Boris bike of the reusable coffee cup, aiming to reduce unrecyclable paper cup waste from London’s booming cafe/coffee chain market. CupClub proposes a system where coffee is served in a bespoke, reusable cup and is dropped off at collection points, washed, and redistributed to retailers, inspired by the informal model of chai-wallahs in India.

As an integral member of the two full-time designers working on this startup project, my responsibilities range from a comprehensive branding strategy (brand concept, logo design, promotional posters, storyboarding for promotional video, client presentations, exhibition design for the London Design Festival), designing the bespoke cup (through sketches, existing product research, parametric modelling, 3D printing and prototyping), to planning the back-end infrastructure and front-end user experience after conducting extensive research with existing coffee retailers and their individual work-flows and supply chains.

The project is endorsed by RSA’s The Great Recovery. The project has been published and presented widely and is currently under preparations for a pilot scheme. It has been presented at Disruptive Innovation Festival, at No. 10 Downing Street with Enterprise Nation, and Design Indaba 2016.

vimeo

1 note

·

View note

Photo

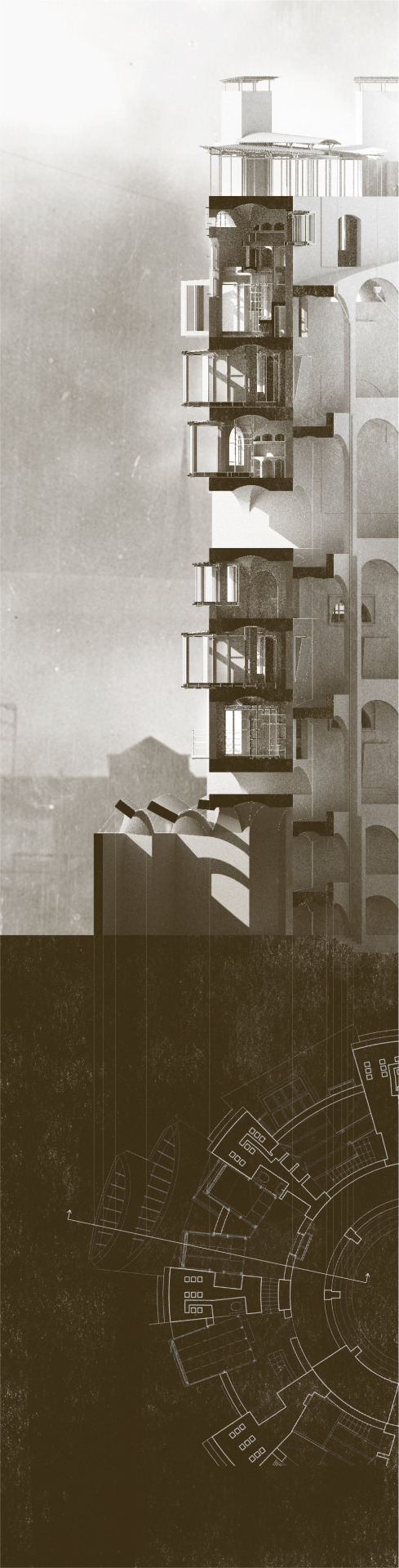

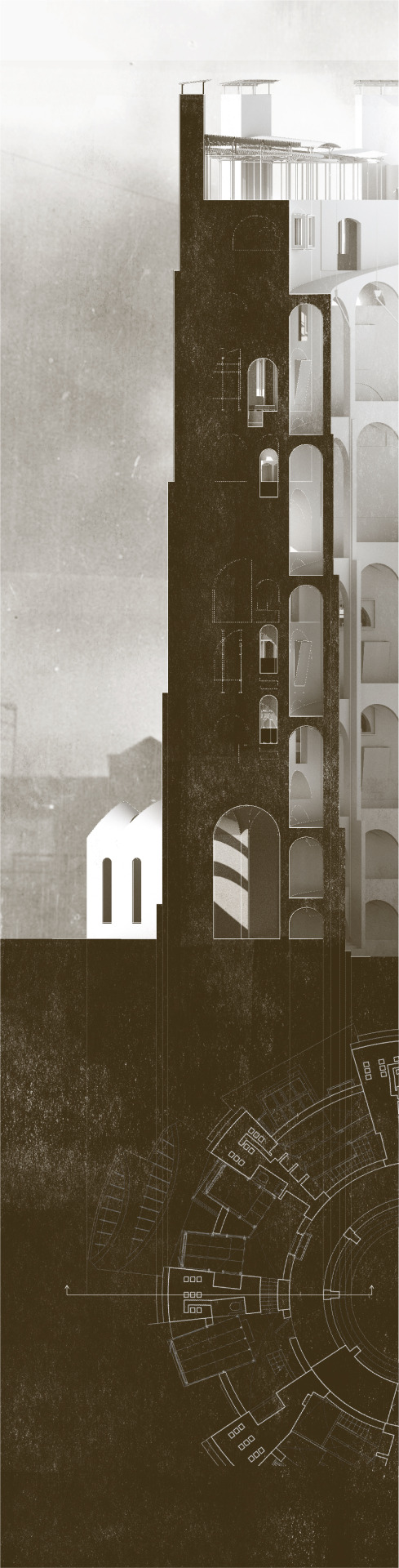

Inhabitable Kilns Artist’s Housing, May 2015

This building project envisions a community of ceramic artists ‘grown’ out of the local resource of London Clay under the site in Kensal Town, London. The design reconciles artists having self-built individuality over their living/working spaces and the need for high density in the context of London. The load-bearing masonry architecture expresses the tendencies of the geltaftan construction method, where adobe bricks made from local London Clay are fired in-situ, with the building as the kiln for its own bricks, resulting in a vault-based framework and a customisable brick infill facade. This project was an outcome of studying extensively vernacular housing from across cultures to explore the overlap between formal top-down architectural design and informal, bottom-up initiative over the construction of people’s own living spaces.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Architectural Manifestos: A Declaration for Discourse, February 2015

An excerpt is below:

“A spectre is haunting Europe – the spectre of Communism” begins Marx and Engels’ Communist manifesto (1848) and following it were words that inspired the mass political upheaval and defined the history of the 20th century. The text was the lynchpin in decrying the injustices of the class struggle, and both formalised and unified the intent of the Communist movement taking root throughout the world’s political conscience. The manifesto genre is a powerful formal declaration of political intent, a rejection of the status quo and a herald for the new and what ought to be.

But the authoritative rhetoric of the manifesto genre has transcended politics, having been appropriated by the arts and architecture where it too is a genre for declaring intents, beliefs and motives exerting an ideological influence on the creative output of its adherents. But the manifesto in architecture differs from its equivalent in politics in the level of rigour in its interpretation. Manifestos in both contexts attempt to act as a vehicle for absolutism in an abundance of opinions, an illusion of consensus within itself. But while declarations made in a political manifesto may be hypothetically translated directly into policy and legislation, the same black-or-white, declarative tone in the context of architecture is betrayed by architecture’s inherent complexities and paradoxically encourages discourse through disobedience, debate and discovery. This essay will examine this paradox and question the usefulness of the manifesto as a tool for propelling architectural discourse within the careers of individual architects, between movements and outside the discipline.

Marx and Engels’ manifesto famously ends with the slogan, “Proleteriats of All Countries, Unite!” (1848), and at its core, all manifestos including those of architecture still embody the same spirit: the exquisite distillation of an avant-garde idea. However, the architectural manifesto is not just a simple political device but its usefulness and purpose has multiplied in its context of architectural theory. Within an architect’s career it becomes a frame of reference for understanding ideological development, while in the debate between movements of architecture it embodies the orthodoxy of the Modernism and is simultaneously cast as an ironic self-parody, or finally even reverse-engineered as a critical and reflective tool for architectural inquiry. Through its continual recontextualisation and reappropriation it takes on a new richness where its declarative role no longer appears to stifle, but in fact encourages the diversity in architectural discourse.”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Outposts: St Pancras Way Estate, September 2015

Based on my site study of this existing 1950s Camden council estate and consultation with its residents association, the project proposes small-scale scaffold tube frameworks that wheel out from underused storage garages located around the estate and unfold into markets, outdoor cinemas, kitchens and other community activities. These offer a framework for reclaiming and inhabiting the ‘left-over’ open spaces of the estate for its community, drawing upon the ideas of piecemeal interventions in Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language and The Oregon Experiment.

The portfolio was designed to be presented to residents of the estate as an accessible package of drawings, pamphlets and kit-of-parts instructions on how to build and inhabit these mobile frameworks for community life. The unfolding of the portfolio and pamphlets echoed the unfolding mechanisms of the design.

Our ideas, drawings and models were presented to residents of the estate at the end of the project with overwhelmingly positive and constructive feedback.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

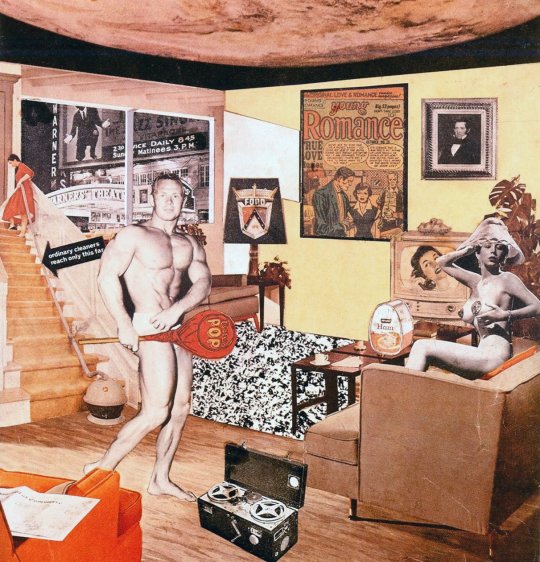

Royal Festival Hall: A product of consumer culture; May, 2014

An excerpt is below:

“The Royal Festival Hall at Southbank, originally completed by the Leslie Martin, Peter Moro and London County Council architects in 1951, and Richard Hamilton’s collage ‘Just What is it that makes Today’s Homes so Different, so Appealing?’ completed shortly after in 1956, sum up two sides of the ambivalent zeitgeist of post-WW2 Britain. Conceived as a part of the Festival of Britain, the Royal Festival Hall was one of the projects designed to reinvigorate the nation with a sense of optimism in the process of recovery from the war and instil a sense of anticipation for the future of a new, modern Britain. While Hamilton’s collage appears to be an exposition of the birth of a new consumerist lifestyle that accompanied this post-war recovery, he does so with tongue-in-cheek irony that begins to hint at the growing cynicism towards this New Britain. When the Royal Festival Hall is considered alongside the other artefacts featured in the collage, the imprint of the post-war zeitgeist on the design betray the building’s conception during this pivotal epoch, making it just as exemplary as the other products featured by Hamilton of the dawn of this consumer culture.”

#architecture#architectural theory#architectural history#consumerism#mid centruy modern#royal festival hall

1 note

·

View note

Photo

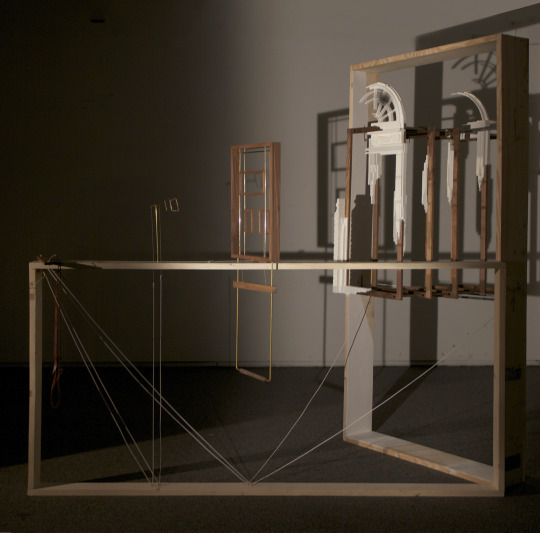

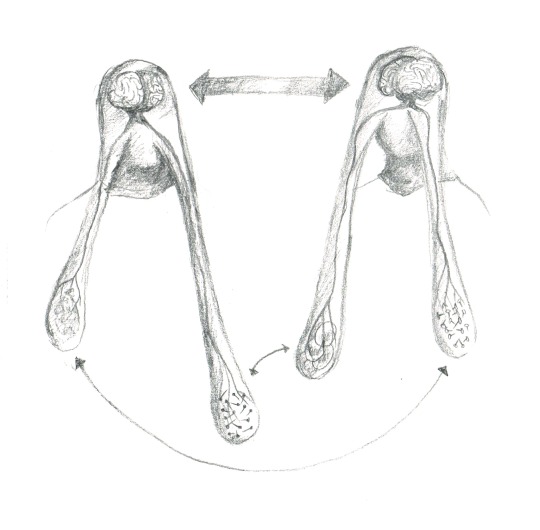

The Coachman, December 2014

A site-specific installation at Pitzhanger Manor, the historic home of architect Sir John Soane, it explores the peculiar social and spatial relationship between Soane and his Coachman, focusing on the hierarchy of control between the two. The hand movements of the 'controller' cause the framed views of the 'observer' to change, mirroring the control that the coachman has over Soane's environment while travelling. Looking through the view finder the 'observer' is shown the view of either the Coachman or Soane from their positions when arriving at Pitzhanger. Each of the suspended frames shows the thresholds visible to each. Soane has a clear view, looking straight through the building, whereas the coachman has an obstructed view with the thresholds overlapping.

The installation features an intricate pulley mechanism consisting of brass inlays in walnut joinery, leather work, with foam CNC milled fragments reproducing the thresholds of the manor.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

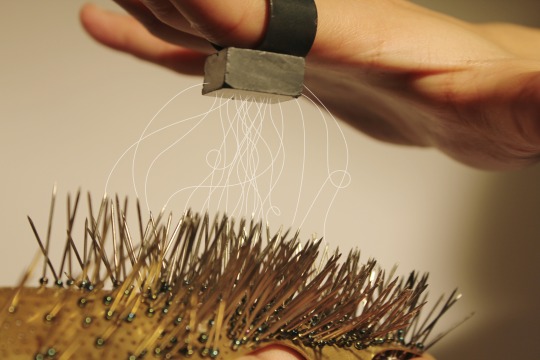

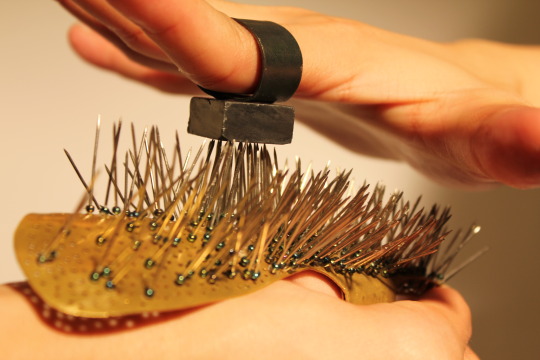

CONNECT, brass, beads, pins, steel, magnet. November, 2012

This jewellery project was a personal response to the theme, ‘connect’. The focus was interpersonal connections, particular the hidden insincerity and animosity behind some handshakes.

A magnetic connection was used between the two pieces to represent the passive-aggressive subtext of what seems to be a friendly gesture. The magnet piece, when in brought close to the other piece in a handshake gesture, will cause the pins to bristle, like the raised hairs of a threatened cat.

2 notes

·

View notes