#architectural criticism

Text

Strangled and Mangled: Classicism and Its Ersatz After Architecture’s Commodification

N.B.: All images, unless otherwise stated, are of my own making. Additionally, if you are having difficulty with parsing the images’ captions in this post, you may want to try viewing this same article on Medium.

If you have ever enjoyed and appreciated the special insights and emphases of my writings, I would encourage you to support me on Patreon! Most of the essays I write are so particular in their subject matter, and so committed to preserving the integrity of my authorial voice, that publication elsewhere is often out of the question, and so I opt for self-publication.

A local example of excellent classical modeling around the base of a column, found on Gainsborough Street in Boston, MA. Despite advancements in industrial production, many new buildings with classical pretensions will cut corners, or employ people bereft of the relevant formal knowledge.

The following can be considered complementary to my series on the Dark Souls series, Bloodborne, and Sekiro, entitled Putting Names to Built Things, the entries for which can be viewed by clicking here.

It is not difficult, when treading the relatively casual discursive spheres of architectural observation and criticism, to find many instances of designs for élite clientele being mocked for formal ugliness, stylistic ignorance, and architectonic ineptitude. Many of these designs have pretensions of classicism (that is, of the Greco-Roman variety), meaning that such criticism can draw from well-established stylistic rules or suggestions. What is rarer to find is an equivalent scrutiny regarding common architecture. This discursive rift is understandable yet problematic: on the one hand, it makes sense that people will find special delight in pointing out the ineptitude of wealthy persons’ taste (which, I would argue, has been a commonality only since the so-called Victorian period’s free-for-all destruction of a coherent classical tradition); on the other hand, the overt focus on “exceptional” sites reinforces a long-standing preoccupation with the 1% of things within architectural studies, to the general exclusion of what most of us encounter day-to-day.

Classicism today, or what remains of it, typically exists in a state far more dire than anything the Victorians could have imagined doing to it. Rather than see it twisted, turned, incised, and scooped out by designers under the delusion that, with enough arbitrary tweaks, a totally new style might emerge by chance, we rather see it paraphrased or mutilated in cheaply assembled new buildings or in a grim life-support state as the vestiges of prior designs. As someone who lives in Boston, a city with an abundance of buildings built during the late-19th and early-20th century, I see much of the latter; and so newer buildings do, on occasion, attempt to integrate into this environment by loosely conforming to some degraded vernacular. Correctives for either of these situations aren’t clear-cut. Usually, the more a building is made-over to keep it up to date, the further its appearance is jumbled about or demeaned by ugly materials (to say nothing of the expenses and labor involved); and a modicum of knowledge of classical detailing, and a team’s ability to competently execute it, is required for new building schemes with an integrative or “historical” objective.

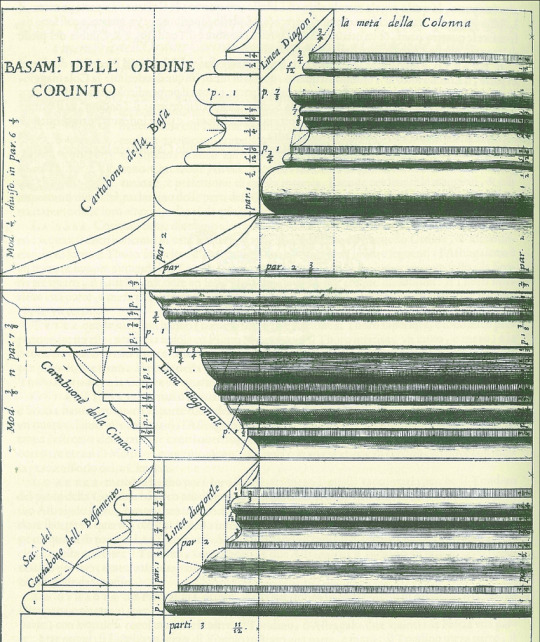

A drawing of a Corinthian order base, done by Vincenzo Scamozzi.

Exactly describing the classical style is not easy, but it must be stressed that none of its components come close to being a domain of esoteric or bewildering knowledge (like many things, the real complexities arise from arrangement). These are things schoolchildren could learn. A great deal of laypeople might associate classicism with, say, the usage of columns, or a certain profusion of sculptural ornamentation; and while these are, or can be, marks of classicism or its variants, among its further-reaching aspects are types and usages of moldings. Moldings are essentially horizontal bands with a dimensional characteristic — either rectilinear or curved, with varying depths and orientations. Each molding is an element of great simplicity which, through contextual application and iteration, acquires its status as a crucial characteristic of classicism, at its best and worst. Like other dimensions of classicism, too, once you are educated as to the types and historical uses of moldings, and once you work with them enough to internalize their properties, you can begin to adjust the implicit or explicit rule-sets for invention. To my mind, two of the greatest practitioners of this were the architects Edwin Lutyens and Richard Norman Shaw.

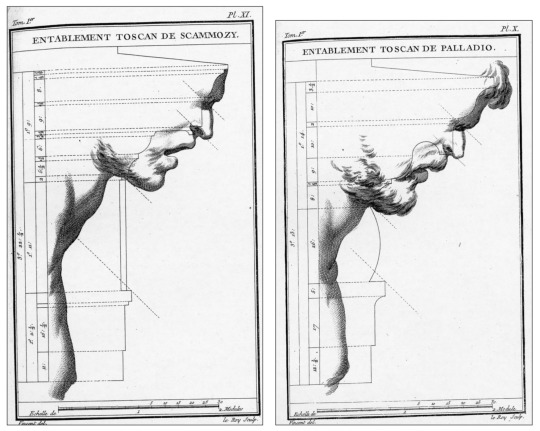

Martino Longhi the Younger, an Italian architect of the 17th century, went to the extent of claiming, “Whoever does not have, among other branches of knowledge, an understanding of the exceedingly important art of moulding cannot be called an architect.” Longhi’s claim, of course, has limited contemporary application, since he was practicing within a culture and a time when the classical paradigm was normative; but the fact such an assertion could have at one point been made — and that its sentiment was shared by other practitioners, before and after — demonstrates its assigned artistic importance, equal to matters such as intercolumniation or superimposition. Michael Hill and Peter Kohane’s paper, “The Signature of Architecture”: Compositional Ideas in the Theory of Profiles, explores how the once-popular idea of columnar proportions and divisions being an analogy for the human body had a parallel in the physiognomic idea that profiles were alike facial profiles of various affect. Jacques-François Blondel, for instance, argued that “the facial resemblance enabled the spectator to quickly apprehend what is pleasing or otherwise about the cornice. …the face was there for theatrical reasons, to be seen by the building’s audience.” Before him, Augustin-Charles d’Aviler wrote (anticipating the notion of architecture parlante) that “[just] as the combination of characters makes an infinite number of words in different languages, so by the mix of mouldings can one invent distinct profiles for each of the Orders.”

Two drawings by Jacques-François Blondel, comparing a couple of Tuscan order profiles, one by Scamozzi, the other by Palladio, and situating them within a physiognomic framework.

As with a number of other intellectual domains, these analogical elements were gradually phased out, alongside metaphysical concerns, as cultural relativism became the order of the day. Today, the physiognomic aspect might be considered especially suspect, given its proximity to anatomical, or racial, prejudice (although the term has enjoyed a very recent resurgence in popularity on platforms like TikTok, perhaps because it can complement sun sign astrology’s typologizing of personality). Hill and Kohane identify Charles Howard Walker’s 1926 text, The Theory of Moldings, as “the last book on the topic.” As they explain, “The book is practical, with no mention of earlier theorists, nor any discussion of the relationship of mouldings to the face or the body; other than prescriptions for cornice ‘facial angles’, which probably derives from Jacques-François Blondel.”

Just as significant as the deprivation of profiles’ symbolic value is the fact that the bulk of architecture students now are not taught anything about profiles, even from the perspective of “practicality” — nor are they taught the intrinsic value (and pleasure) of drawing, as distinct from angular-centric computer modeling. If one were to ask our average architect to draw a small arrangement involving the Doric order with competence, and without an external point of reference, they would be unable to do so. Such information, although readily available to anyone looking for it, has long been relocated to an area of superfluous considerations, alongside forms of ornamentation, deepening an artificial rift between “legitimate” and “classical” architecture. Profiles have rather become the domain of cabinetmakers, trim installers, or some form of interior designer, although this specialization has been by no means a guarantee of competence.

Classicism transformed, wielded with imagination and tact. Central Congregational Church, Newton MA, designed by Hartwell and Richardson. Here, the elements of an enriched entablature have been put into a rustic format, giving the effect of the layers phasing in and out of a sheath.

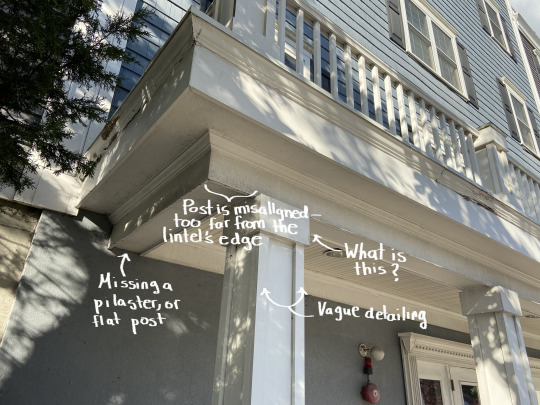

Classicism’s system of moldings is accompanied by a system of alignments and positions involving posts, lintels, and fenestration. As a classical structure grows and each component is put into place, it asks for a relevant response and optical relationship. Again, there is wiggle-room within the creative process once one has graduated to competence. But there are certain rules which ask for regular adherence: for example, the rule which requires that a column’s outline (given that the column’s entasis has not been deliberately exaggerated) aligns with the first fascia of the architrave; or the rule which requires the column to be positioned so that the capital is not under, but extends a certain distance beyond, the architrave.

It should be stated that there is quite enough modern-day classicism so committed to a kind of prim accuracy that the results are simply myopic expressions of core rules, such as the work of Quinlan Terry, or Michael Dwyer. This work is deficient not in competence but in imagination. It is correct, fine, and unremarkable. The trick to mastery would appear to be finding the unteachable midpoint between Lutyens’ apparently paradoxical statements that, “You cannot copy: you find if you do you are caught, a mess remains”, and that, “You cannot play originality with the Orders. They have to be so well digested that there is nothing but essence left.” Our focus here, however, is not unimaginativeness but incompetence, ignorance, and forms of degradation — makeshift, renovative, professional, industrial.

A portion of the exterior of the W. J. Sullivan House, Brookline MA. Despite a fairly ugly exterior, the house’s designer provided some amusing flourishes, such as this chair rail molding reappearing between a salient, recalling the various solutions to the problem of corners during the Italian renaissance.

A few more comments. Although cultural relativism has had a hand in freeing up assessments, theories, and practices from certain constraints, it has had the additional effect of making it very easy to believe that, after a point, classicism was holding on simply by way of convention (local, national, imperial) or according to socioeconomic pretensions to taste (I would reiterate that the new, house-proud middle-class, and the aimless architects, of the 1800s more or less obliterated any sense of what proper classicism is, with the effect that today’s élite really have no more of an idea of what an entablature should look like than the column- and gable-desiring lower classes). To be sure, these were, and are, sustaining factors; but they do not fully explain the incredible persistence of classicism. I believe that the relativist sentiment can only be upheld by people who have not spent significant time doing classical designs themselves. Get in deep enough and you might begin to sense that this system really does hold a sort of inherent aesthetic perfection, an almost inevitable rightness that, after a while, becomes as natural and sensual as the human body.

What I mean to do with this mini-essay — actually more of a brief tour with a preamble — is not provide a reason for why any of this matters. Readers will have to do (or not do) that for themselves. I am not going to indulge an imaginary debate over whether or not taking common facades to task for their aesthetic disasters is class warfare (in these instances, however, given the sites, it is probable that most of the private buildings depicted have fairly high monthly rents). Nor is my intent to make a hard correlation between a form of external propriety and residential, or public, happiness. It is rather to illustrate how the vast majority of what we directly, civilly perceive as deriving from Greco-Roman classicism has been degraded into the crudest, barely composed forms — and to ask if it might not be better to omit these details altogether from renovations or schema if they are going to be so tortured and blunted. It is my opinion that cheaply made and ineptly executed classicism is far less preferable than any adequate “modernist” design. Classicism, by nature of being distinctly composed of standardized modes of articulation and units of assembly, gives us an executional baseline. Anything below this baseline merely impresses a discrepancy. Modernist architecture has no such baseline, no such codification, even if there is a common canon of its practitioners.

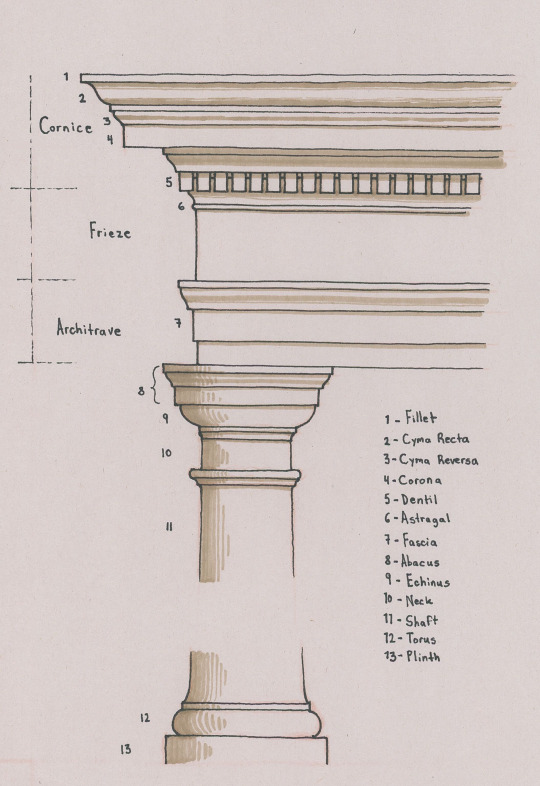

A visual point of reference for a standard classical profile. Note that, even within this example, there are certain alternatives present, such as the architrave having two, rather than three, fasciae; and that certain forms, and their terms, are not included (such as the ovolo, scotia, or cavetto).

With all that out of the way, let’s begin. You can use my drawing, above, as a point of reference for arrangement and terminology; but please also refer to other diagrams online which are sure to have more information. And be sure to enlarge the photographs if the captions are illegible.

1

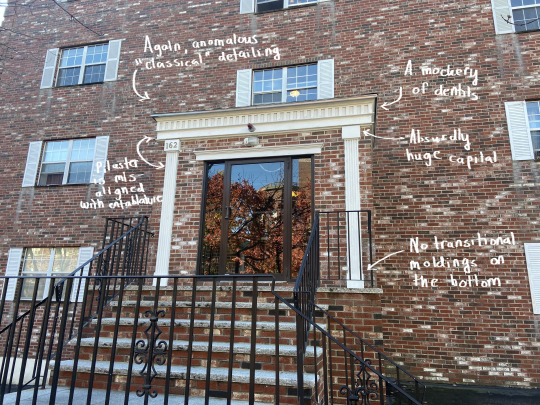

As with some of the other examples, it’s difficult to tell if this building had a prior appearance and if its current state crudely reuses, or “renovated”, some external structural details, or if it was entirely designed this way, so haphazard is its assembly, so slapdash its detailing. A vaguely classical surround frames the entrance with pseudo-pilasters missing their extremities. Consoles have been mashed into the middle and sides of the surround’s top, and the side consoles’ “hovering” bottom-tips highlight the pseudo-pilasters’ headless state. The entablature is nonsensical — a cornice with an overly large corona, and a slightly smaller duplicate of that below. The columns are unrelated, having no classical character, and being set too far in from the side of the lintel they are supporting.

A diagrammatic portion of a Doric order. Taken, and edited, from Pinterest.

Note the orange line I’ve drawn on the diagram above, showing how there is a continuous “line” conforming the column’s upper portion to the side of the architrave (at least that of its lowest fascia), and then to the frieze’s side. Note, too, that the column’s capital consequently protrudes past the architrave, rather than being all under the lintel. These are a couple of core attributes of classicism, the absence of which generally indicates that the designer has no idea what they are doing, or that an inconsiderate, abusive renovation has pushed the classical elements to do what they are not meant to do. We will see many instances of this mistake hereafter.

2

It is almost certain that the bay projection on this house once had a strong cornice above it. As the owner(s) proceeded to “update” it over the years, this cornice may have been in a deteriorating state and was removed, but not replaced, with the rest of the projection’s top covered over with shoddy laminated roof shingles. I’m tempted to venture the guess that most of the courses with dentils here are replacements, but it’s not clear. What is clear is that there is too much dead space above the bay and upper story dentils. Moreover, the dentils do not emerge from a molding but are each a thin block stuck to a board’s underside. They look flat, lifeless. They are a child’s project. One cannot even say that these upper jaws are “snarling.”

3

Designs such as this one are so ridiculous that it is frankly extremely difficult to not imagine it as having been conceived with a condescension verging on subconscious contempt (similar to Robert Venturi’s Guild House, originally capped by sculptural TV antennae, mocking the inhabitants for their “chief pastime”). What is more likely is that it is a cheap and inept attempt at bridging the “southern colonial” look with a modern housing block. Why have the classical details at all, though? The columns — pornographically stretched out to Fun Size, and bereft of entasis — are like a bad joke that’s worn out a tepid welcome, and the pediment is just dumb, with its raking cornice sliding clear past the lintel below, its body covered by clapboards. Of particular unfortunate note is the detail of the lintel above the columns “clipping” through the abacus of each.

4

Classicism here assumes a highly reduced appearance (as with so many houses, a curvaceous cyma is retained for the gutter cornice), yet still asks for certain responses to its calls. The rectangular posts have singular base moldings, but no capitals; and, again, they are out of sync with their lintel — especially where it protrudes to match the pediment’s projection. The reductions, or abstractions, of this design do make it a little less offensive to my eyes, and I might not have stopped to take this photo at all if the silly pediment, and the problems it brought along with it, weren’t included.

5

I’m not sure if this is or isn’t uglier than the third example, but its similarly anomalous (or nearly anomalous; the building’s sides are clasped by brick quoins) and inept classical details make one wonder why they were included at all, besides as a cheap, preemptive acquiescence to sentimental taste, as the out of place, non-functional window shutters additionally suggest. Despite having capitals and bases, the “pilasters” are barely an improvement over those in the first example, and are set too far away from the block’s edges. The entablature is brutal idiocy, with a row of pseudo-dentils maimed so badly that the section looks instead as if shallow rectangular impressions have made into the surface. I’ve seen gas station roofs styled as huge entablatures with more literacy than this.

6

Zombie classicism, so deprived that it has retreated into an unconscious form of camouflage, several levels removed from the referents, all of its cracks showing. This may be the most dire example of the bunch.

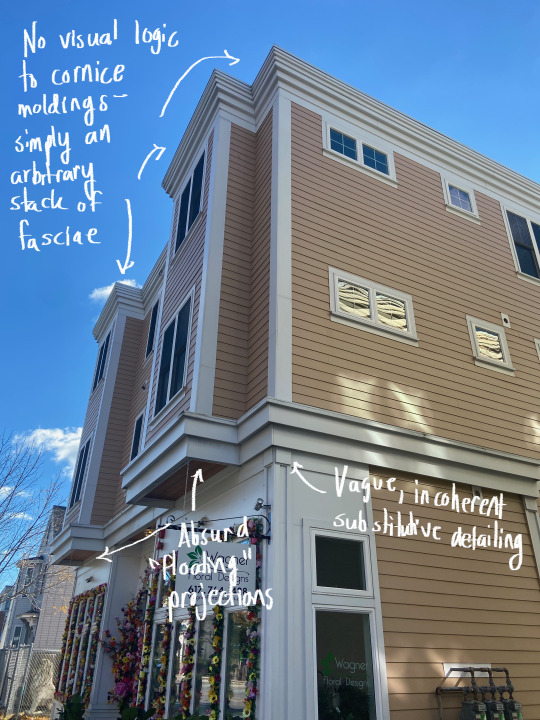

7

A newer, mixed-use building. Oriels are not a classical element, but they have traditionally been visually, if not also structurally, supported by an underside of diminishing moldings, corbels, or consoles. The lack of either here, combined with the string course below appearing to jut out just as far, if not further, than the cornice, gives their sudden thrusting-out an absurd effect: too bottom-heavy and yet floating. The cornice makes a big deal of itself, despite having nothing to say. Its only organizational, formal principle is the sections’ gradual thinning as they near the top. There is a feeble attempt at suggesting corner pilasters on the building’s first story, comparable to the shoulder-shrugging posts from the first example.

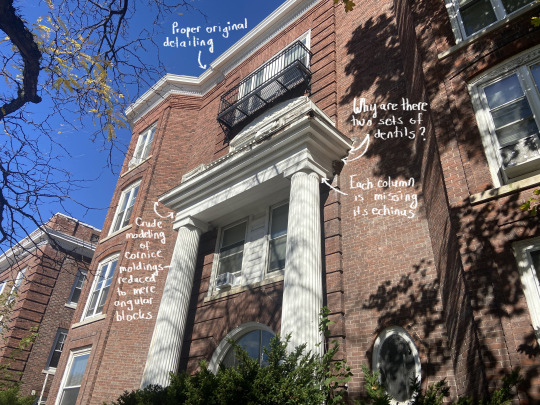

8

One can find ample examples of entablatures and molded bands from antiquity, and throughout various phases of neoclassicism, which reuse certain ornamentation (such as the bead and reel pattern, or egg and dart pattern) in quick, adjacent succession. Dentils, however, have always been excluded from this duplicative leeway. Note how, in a photograph of a detail of the Triumphal Arch of Septimius Severus, dentils are indeed reused, but always within a different zone on the structure: first, at the arch’s imposts; then, along the entablature; and finally below the cornice. Crude and arbitrary segmenting and modeling aside, the entablature here breaks this rule, looking even more ridiculous since its dentils are crimped as a pie’s crust is. The columns lack echini, and the oversized abaci look like cardboard boxes placed atop tubes.

9

A situation so grim that one resists the fact that it is a finished product and not a construction site. The entablature is a set of rickety chunks cobbled together, their sole pretensions to enrichment being the semblance of panels, echoing the dado’s pseudo-panels. It is curious that the columns utilize a different material and exhibit entasis, almost as if they are molds taken of prior columns. Again, this facade — the clapboarded rise beyond included — is such a hodgepodge that one has to wonder about the chronology of development. Was this once a Queen Anne-styled home, mutilated through renovation and now unrecognizable as such?

10

Classicism kept in a vegetative state when it has lost nearly everything that once made it whole. This portico would look so much better if all of the entablature’s vestiges were scrapped, replaced by a plain lintel, and if the posts weren’t poles. As it is, this is a surgically removed, rotting upper jaw, the overt mass of which goes against a minimalist supportive solution.

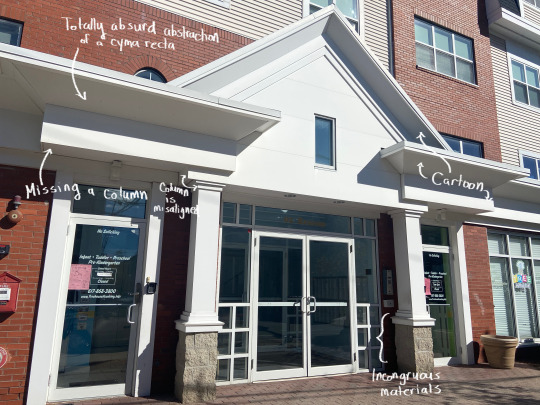

11

There is a bit of play here which identifies the design as more postmodern-classical than classical, at least within the realm of intentionality, yet the materials’ cheap appearance and the overall cartoonish, warbling tenor — the way an entablature has been suggested by abstract quotations of a blown-up cornice — merely call to mind the reality that the built-in exaggerations of postmodernism have ultimately led to an uncontrolled flood of kitsch. One often sees this sort of kitsch around outlet malls/centers, where gables, faux-chimneys, and hollow Italic towers have been propped up as if to offer scraps of “humanizing” design, all the while implicating the tradition-deprived mundanity and regurgitated tedium of persons’ consumerist lives.

12

An acceptable design lurks beneath this newer building’s fussy exterior. As I’ve remarked, the projected entrance block looks better if you squint your eyes, omitting the jumble of panels and strips. Once again, like the seventh example, the designer has replaced pilasters with vague and vapid substitutes, the “capitals” of which have no geometric relationship to adjacent element, and which are out of sync with the capital-molded posts above. Amazingly, however, the latter’s outlines are aligned with their lintel’s sides. The main block’s first story windows on the right are echoed by blind windows on the left, but these are very obviously not genuine recessions — rather, frames stuck onto the surface — and only detract.

13

Another nonsensical hodgepodge. Everything about the portico is wrongheaded. The paired columns are not only set too far in from the lintel’s edges but have differing positions relative to one another — and they are too visually weak relative to the enormity they are upholding, similar to the tenth example. Such eaves asks for bold, rustic piers. Perhaps the owner(s) wanted as much shelter as possible, which may explain the eaves’ extent, but nothing about the solutions here are elegant or formally coherent, and the columns’ classicism appears desperate.

14

Not as bad as the sixth example. Still, pretty bad. The square columns’ capitals are meager to the extreme. They might work on a fence’s main posts — not as the caps for a building’s prominent structural device. And nothing about what they support is worthy of being seen.

15

This monstrosity of a gaffe provoked a double-take. Despite being a newer building, the portico is hardly any better than the last one shown. Correct modeling on the columns can’t hide their incorrect positions. The entablature, with its blundering triple-threat stack, is laughable — a protuberance with all the stylishness of a bellowing burp. What it brought to mind, actually, are photographs of a shockingly ugly mansion in Sandton, Johannesburg (see the second image). Anyone with an informed eye knows that this is the polar opposite of sophistication.

16

Not much new to say here, except that this example is particularly baffling, since there is a point of reference next door. Columns, yet again, aren’t where they should be, the architrave is missing at least one fascia, the dentils are badly spaced, the cornice is too flush and flat, and the entablature as a whole has been contorted into a boxy mold. I just don’t get how stuff like this happens when all you have to do is look to your right.

17

All pretension — no discrimination. This portion of a Newton residence was more recently executed. The rest of the house, which has been altered/renovated to different degrees, appears to have once been of a sort of late-19th or early-20th century “free classic” variety. Metal Corinthian columns (now showing signs of rust) have been used, but nothing else is recognizable as the Corinthian order — or, really, as any sort of order. The entablature is an omissive pseudo-entablature, and the pediment’s size asks for its vacuous tympanum to have some kind of infilling or relief work.

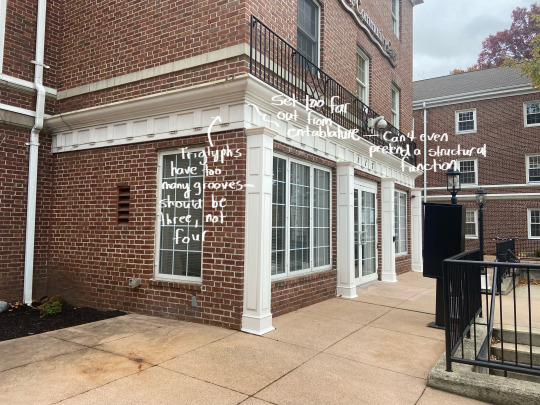

18

This is our last stop today. Many more examples could have been used, but after a while the faux pas are so consistent that commentary becomes redundant. Because they are barely underneath the entablature, it is unclear if the posts mean to be engaged square columns or pilasters with too much dimensionality. As either thing, they are four absurd interjections, symbolically and structurally unmoored. The frieze’s triglyphs have four grooves — one too many. Triglyphs are named such because they have, literally, three (tri) carvings, or grooves (glyphs). Expressed correctly, a triglyph has two “whole” grooves incised onto the main body, and then a half-groove on either side — coming out to three grooves total.

I hope that this tour has been educational and engaging. I also hope that it has not given you the impression that the wielding of a discriminating view is done to detriment of the viewer; rather, I believe that explorations like this have the ultimate effect of helping one grow into an appreciation of architecture well-done all the more. The eye is transformed for the better. It is likely that I’ll do another installment later on, if I can find enough novel missteps around the area. I’m pretty sure I can; and I’m pretty sure you can, too — unfortunately!

#architecture#boston architecture#architectural criticism#classical architecture#neoclassical architecture#vernacular architecture#architectural history

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An exhibition/pavilion review:

Ringing Hollow: A Review of Black Chapel, the 2022 Serpentine Pavilion

Calvin Po

It’s perhaps an unfortunate coincidence that on my way to this year’s Serpentine Pavilion, Black Chapel, designed by Chicago-based artist Theaster Gates, I had a rather more spiritual experience when I passed by a group of street preachers on the square next to Speaker's Corner. With their Union Jack bunting draped all around their assembly, placards with JESUS IS LORD, large banners of the English flag adorned a patriotic lion and names of the all the London boroughs proudly proclaiming LONDON SHALL BE SAVED. Puncturing through even my atheistic, bemused scepticism, the blaring music and odd bursts of song had a patriotic, messianic energy that was electric. By the time I got to the Chapel I came to see, it had simply been upstaged.

Pavilions have often mattered more for the reason they are built, than the actual functions they house. From completing the composition of a Picturesque landscape, to Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion itself becoming a manifesto, the purpose of pavilions often exists beyond the building itself. In the case of the Serpentine Pavilion, it is more about the annual cycle of patronage by the London cultural elite as they pat the “emerging architect” of the year on the back. So I was intrigued when Gates claimed a loftier, more sacred ambition of creating a ‘Chapel’, a “sanctuary for reflection, refuge and conviviality”, for “contemplation and convening”, on top of the usual purpose as a place to sit and buy an expensive coffee.

The pavilion’s imposing 10.7m high cylindrical form, clad in all-black timber has an immediate presence as I approach. Gates claims the form references inspirations as eclectic as “Musgum mud huts of Cameroon, the Kasubi Tombs of Kampala, Uganda [...] the sacred forms of Hungarian round churches and the ring shouts, voodoo circles and roda de capoeira witnessed in the sacred practices of the African diaspora.” Perhaps the subtlety of these references is lost on me, but the Pavilion mostly evokes an industrial structure, like a water tank or gasometer, especially with its external ridges of timber battens and internal ribs of timber and metal composite trusses. Yet despite the grand gesture of an open oculus in the roof, letting light into the inky, voluminous interior, it fails to move me in that transcendental way that even a modest place of worship can.

Is it perhaps the quality of the execution? Serpentine Pavilions are often put together on hasty timescales, with six months from conception to completion. Little details give this away: boards of the decking and cladding not quite lining up, the black-stained timber a bargain basement imitation of yakisugi (Japanese technique of timber charring). Perhaps this can be forgiven of a non-permanent structure: in a nod to sustainability credentials, this year the designers have taken care to ensure the structure is demountable, down to the reusable, precast concrete foundations. But seeing that the Pavilions are almost always auctioned off to recoup the costs and relocated to the grounds of private collectors and galleries, this seems more a convenient commercial expediency, than an environmental one. Perhaps it is difficult to be spiritually moved by a structure that is sold and delivered like a commodity, with little rootedness in its physical and congregational geographies.

Or could it be the atmosphere, a lack of drama? One of Gate’s flourishes, such as his seven silvery ‘Tar Paintings’ that are suspended in the inside walls of the space like abstract icons, are a nod to his father’s trade as a roofer, and Rothko’s chapel in Houston. Yet these self-referential gestures seem lost on the throngs of sun-seeking Londoners taking brief shelter from the heat and wilted grass, with hardly anyone giving them a second glance. Most seemed more interested in the shade than symbolism. For a project that also emphasises “the sonic and the silent”, the acoustic atmosphere of the space I found wanting, perhaps because of the sound that leaks out of the two full-height openings that puncture straight through the volume: its acoustic experience had neither the reverberant, sanctified silence once expects from a chapel, nor the sonic presence that the street preachers managed to carve out of a busy corner of a London with just their vocal chords. Instead, all I heard was the low chatter of visitors going about their own business. The Pavilion is being programmed with “sonic interventions” (read: music performances), and the jury is out on whether or not the Pavilion can serve as a suitable venue for sounds with a more explicit, ceremonial intentionality.

But perhaps the coup de grâce was the decision to relocate a bell from St Laurence, a now-demolished Catholic Church from Chicago’s South Side. Sited next to the entrance, it is to be “used to call, signal and announce performances and activations at the Pavilion throughout the summer.” Gates explains this decision as a way to highlight the “erasure of spaces of convening and spiritual communion in urban communities.” But now mounted on a minimal, rusty steel frame like an objet d’art, I can’t help but feel a cruel irony that a consecrated object that once used to convene a lost community is now used as a performative affectation for the amusement of London’s arts and cultural gentry. This perhaps exemplifies a deeper ethical issue at the heart of the Pavilion’s concept: narratives of collective worship, cherry-picked from across communities and cultures, are sanitised, secularised and aestheticised in a contemporary art wrapper for the tastes of the largely godless culture crowd. The curator’s spiels of a creating “hallowed chamber”, if anything ring hollow.

As I leave Hyde Park, I pass by again the assembly of street preachers, who have now moved on to delivering a sermon. Gates said of his Pavilion, “it is intended to be humble.” Yet I can’t help but but feel how much more these preachers have achieved, with so much less.

#writing#journalism#architecture#architectural writing#architectural criticism#critique#architectural journalism#New Architecture Writers#building#building study#building review#exhibition#exhibition review

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edwin Lutyens: Architect Laureate :: Roderick Gradidge

View On WordPress

#0-0472-0023-5#architects#architects biographies#architects biography#architects memoirs#architectural criticism#architectural design#architectural history#baroque architecture#books by roderick gradidge#british architects#british architecture#christian architecture#edwin landseer lutyens#english architects#fin de siecle#first edition books#georgian vernacular#gertrude jekyll#gothic architecture#historical architecture#history architecture#modernism#neo-classicism#neoclassicism#palladianism#renaissance architecture#romanesque architecture#vernacular houses

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Call your reps and demand a ceasefire now

Free Palestine 🇵🇸

#free palestine#palestine#emily blunt#chris evans#critical role#mcu#superman#baldurs gate 3#dark academia#bookworm#marvel#halloween#influencers#stop asian hate#harry potter#steve harrington#architecture#basketball#celebs#celebrities#hot celebs#celebrity news#bay area#tag game#taylor swift#beauty#beach#barbie#ken#star wars

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

ppls hot takes r getting a little too hot

#like i saw someone say they wanted grover to be the brains of the quest#when annabeth is right there??#and then someone was complaining abt how they ruined annabeths character in ep 4#like how so?? she continued to be smart outspoken and she babbled on abt architecture#and too many ppl r saying annabeth is gonna be the traitor lkek let’s use critical thinking skills shes risked her life for him#they’re not gonna be enemies#the luke defenders r funny tho#but i’ve seen too many wrong opinions abt annabeth#bitches jus wanna complain atp#let my girl live#lynx talks#pjo#percy jackson#percy jackon and the olympians#pjo spoilers#pjo tv show#walker scobell#annabeth chase#leah sava jeffries#hot take#grover underwood#rick riordan

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

#artwork#education#architecture#art#advertising#books#room#reading#critical role#romance#fantasy romance#photography#my photography#popular#homestuck#home#light academia#love#life#literature#nature#vintage#spotify

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

HEY YOU! YEAH YOU WITH THE FACE!

HAVE YOU EVER WANTED TO FIND OUT WHAT THE GREATEST CASTLE REAL OR FICTIONAL OF ALL TIME IS?

GOOD YOU SHOULD!

SO LETS FIND OUT

SUBMIT YOUR FAVORITE CASTLE, PALACE, OR FORTRESS TO THE BRACKET NOW!

Rules for consideration

it must either be a Castle, Palace, or Fortress,Function as such and/or, have Palace, Castle, and/or Fortress in the name.

unless it The Castle/School that Shall not be Named, then its being rejected on principle.

#poll#architecture#comics#superman#Girl genius#Curse of strahd#real life#castlevania#dracula#game of thrones#critical role#dungeons and dragons#Fantasy#Castle#Castles#lord of the rings#shrek#dreamworks#disney#legend of zelda#bloodborne#elden ring#dark souls#dragon age#hollow knight#fromsoft#avatar the last airbender#atla#mario bros#fable

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

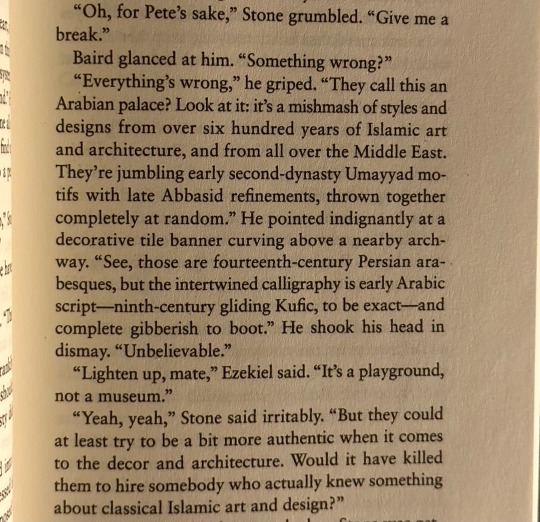

I’m reading the first book in a trilogy of Librarians novels (I was so overjoyed to discover they exist omg) and I just. Jacob Stone being the absolute best, ily ily ily

-from The Librarians and The Lost Lamp by Greg Cox

not only does he write in the character’s voices so incredibly spot-on and well, but this is one of the most refreshingly non-exoticizing, non-othering, even (incredibly!) culturally appreciative (not appropriative) depictions of Arab and Persian culture/art/land/history I’ve ever seen from a white, American author, which is just such a literary breath of fresh air!

I’ve only read about a third of the book so far so I can’t speak to the whole thing yet, but wow, for a book based on a show that didn’t always do.. great.. with respectful handling of nonwestern/non-European cultures, this is so amazing to see ♡

#book quotes#the librarians#the librarians and the lost lamp#anyways I’m enjoying this one so much and incredibly appreciative of how respectfully and even dare I say us-critically Greg Cox is writing#this book just 10/10 so far#like literally the passage above is actually criticizing the commercialization exoticizing othering careless disrespect that is too common a#and I just ?? it’s so refreshing and nice to see in a book#and ofc giving these lines to Jacob stone is so perfect because he WOULD say that he WOULD care <33#ps seeing the word “mishmash” in the context of discussing Islamic architecture#totally had me misreading it as “mishmish” at first 🍊 (<- closest thing to an apricot emoji I could find lol)#personal

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

#detail#critic#conceptual#space#manhattan#nyc#time#installation#minimal interior#gallery#critic critiquing#critiquing#exhibition#art exhibition#interior design#design#critique#chelsea gallery#interior architecture#architecture#artist on tumblr

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

For the Architectural Review

Bass Coast Farmhouse in Victoria, Australia by John Wardle Architects

Calvin Po

For the architectural profession, building on the unceded lands of Indigenous people is a conflicting proposition, yet one that is almost inevitable for architects in Australia. Bass Coast Farmhouse, by John Wardle Architects, is one such project, built on former farmland among coastal heath reserves off the Bass Strait in Victoria. As they do with all their projects, the architects acknowledge the Traditional Owners, in this case the Boonwurrung people of the Kulin Nation.

Between the role of the architect, duty to their client, and wider questions of postcolonial ethics, these tensions permeate the house’s character and its distinctive relationship to the land. The Kulin Nation’s Tanderrum ceremony extends to outsiders a welcome to Country conditional on honouring the land and its intertwined relationships with its people: ‘The land ... is our mother. These cliffs are like our cathedrals, this is our church.’ On this sacral land, the architect’s exploration of ‘the nature of building on terra firma’ is not just an architectural fantasy, but a reflection of this quandary, and rejection of colonial myths of terra nullius – the land is not a blank slate.

From ecological footprint to the architectonics, this sensitivity is omnipresent. The house is entirely off-grid and the construction is largely prefabricated to minimise onsite waste and disturbance. The house sits gingerly on the ridge of a dune, making only the necessary contact with the ground. It is then cantilevered as the dune falls beneath the house. The cantilever, with its barn-like void and its suspended walkway, evokes an archaeological shelter, spanning over and shielding artefacts, and framing them for display. To enter the house, a set of stairs descends from this walkway as if down into geological strata of times past.

As for what is being sheltered – the dune and a scattering of stones – they too become imbued with new significance. After centuries of European colonisation, few traces of Boonwurrung heritage remain. It is the land itself, and the Boonwurrung people’s intergenerational custodianship of it, which is left to be protected. A critical part of the project is repairing parts of the site degraded by modern agricultural extraction, with a specialist advising on a massive replanting project for carefully restoring indigenous grass, shrub, and tree species. In contrast with the landscape, the house’s timber cladding (already silvering in the antipodean sun) and the corrugated galvanised steel roof seem to acknowledge its fleeting presence, relative to the long histories of the Kulin Nation.

The house is the antithesis of being ‘monarch of all [it] surveys’, to quote William Cowper’s poem on Alexander Selkirk, the British castaway in the Pacific. The Anglocentric ideals of Capability Brown’s Picturesque landscapes, where the earth itself is reshaped for the pleasure of the house’s gaze, are rejected. All the outward-facing windows, including the living room’s picture window, can be shuttered at a moment’s notice. For a house surrounded by expanses of nature and the coast, it is surprisingly introspective, with its primary aspect oriented around the central courtyard. The house is also extensive for a single-storey family home, with beds and bunks in polished, timber-panelled rooms, accommodating over a dozen people. But rather than bearing down on the terrain or asserting its panoramic dominion, the house seems to recognise that the views and the land are on loan, not owned.

John Wardle Architects, with its recently inaugurated Reconciliation Action Plan, joins others in Australia in re-evaluating their relationship with First Nations. But in the end, the impact a private house can have on reconciliation is limited. As Carolyn Briggs, a senior Boonwurrung elder, once reflected, ‘I’m always trying to find markers that inform me that we still have a part in this place. ... I think it would be amazing if you can start to read the land and wonder about the history of the people who lived and died before we were here. Hopefully one day you’ll know it. But we can’t see that now in the built environment.’

Link to original article here.

#writing#journalism#architectural writing#architectural criticism#critique#architectural journalism#New Architecture Writers#building#building study#building review#architecture#Architectural Review#John Wardle Architects

1 note

·

View note

Text

Building the Georgian City :: James Ayres

View On WordPress

#0-3000-7548-0#17th century architecture#18th century architecture#architects#architects patrons#architectural criticism#architectural history#architecture georgian period#baroque architecture#books by james ayres#british architects#british historical#building construction techniques#building materials#building regulations#christian architecture#fin de siecle#first edition books#georgian architecture#georgian building#gothic architecture#historical architecture#history architecture#modernism#neoclassicism#palladianism#renaissance architecture#romanesque architecture#signed books

0 notes

Text

LAST 8 HOURS TO HEAR THE 1989 TAYLOR’S VERSION😭😭🫶🏻🫶🏻🩵🩵

I’M SO EXCITED

Also, I took this photo today, I like it very much.

#spotify#august#taylorswift#1989 taylor's version#light academia#dark academia#romantic aesthetic#book photography#naturecore#middle east#critical role#jujutsu kaisen#lgbtq#taylor swift#fnaf#architecture#ranboo#australia#hannibal#happy halloween

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

okay, time to nerd out about language for a moment in the context of tmn.

you all remember halas, right? local gem wizard (tm) and overall problematic practitioner of the arcane? you also remember how he is kinda out of his time when the mn meet him during the campaign? and how the dwendalian empire is sort of inspired by germany?

listen, as a kid who just started german studies (and is also german, blah blah) it would mean the world to me to see halas' old notes be in old or middle high german instead of just magic gibberish.

imagine. caleb going through the notes to make nott veth again and having problems with the translations, cause its sorta like his mother tongue but also not at all. and how nott could just take one glance at a sentence, see the connection between two words because she saw the whole instead of the parts and tell him "those two words could fit together" and suddenly the whole thing makes more sense!

we got percy attempting to translate celestial in tlovm, please give us caleb struggling with an old version of his own language with a different spelling system and weird pronunciation and inconsistent grammar!

just imagine halas writing his spells like the Merseburger Zaubersprüche or in the stanza of the Minnegesang. Imagine his planar illustration in the style of the old maps and images of the world (and its different planes! surprisingly, those are very similar to how dnd imagines the planes but I do not know nearly enough about either to give a more nuanced opinion) and imagine his writing with the elaborate first letters and decorations and everything!

please, just imagine the look of the codex manesse for halas' spell work. (that btw is a link to a digital browse of aforementioned codex manesse)

I just think that could be so neat. and such a wonderful way to make all us poor kids who study middle high german and watch critical role to go "ooohhhh I know that stuff!!"

it could be so dope

#critical role spoilers#critical role#mighty nein animated#the mighty nein#i will refrain from yelling about architecture in this post but you have to understand#will the dwendalian empire have an unnecessary amount of castles? how many will be on mountains?#will rexxentrum be baroque? gothic? will there be fachwerkhäuser?#i am having thoughts#edit: fixed my spelling again

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Regarding Volo at the moment, but also in general with any hardcore villainized characters, I certainly get the sentiment behind wanting to not woobify antagonistic characters too much, but also like. I think for me, when the primary fandom take away is that a character is HARDCORE IRREDEEMABLE, NO GOOD QUALITIES IN THIS ONE!!! it’s almost like… an act of balancing out. Yes, I get Bad Man did Bad Things, I’m a person with a brain, but when it seems like EVERYONE is talking about how the Bad Man did Bad Things and needs to be, generally, physically harmed for the Bad He Did, it just feels like an act of balance to say,

“Okay but why don’t we explore this line where he said he’s experienced trauma before? And how he instantly backs away from talking about it under the explanation he gave himself that everyone must experience trauma to that degree?”

Or, “Hey, the guy has three friendship evolution Pokémon, two of which notably will leave their trainers if they don’t like them. Why do people extrapolate from that that he must be an abusive trainer?”

Or, gods fucking forbid, “Hey. Why is this character, who’s notably got indigenous roots to the setting, constantly being made the villain in angsty stories for the two white twins?”

Idk man, again I get not wanting to woobify too much, not wanting to strip a complex character of their complexity and the like, but if your takeaway is that any sympathetic or nuanced takes on a heavily villainized character is “woobifying,” like… idk, touch grass as the kids say. Who’s going to stop me, the Anti-Wooby Police?

#my dumb textposts#AGAIN THOSE OF YALL WHO HAVE BEEN HERE FOR MY FNV SHIT - YALL SAW ME DO THIS WITH VOOPS QNSBDKSBSKSNDM#I REMAIN UNCHANGED IN THE FACE OF BAD FAITH TEXTUAL READINGS WHBDJDBD#and I do think there’s a difference between. All That Bullshit and good faith criticisms#saw someone bring up that volo’s weird ass Greek coding is probably because there’s a LITERAL conspiracy theory that the Greeks-#-came to japan first based on the architecture of a building or something. like#WHAT. that’s wild. THAT I would argue is a good faith criticism. to me that just motivates me to make his story and the story of the clans-#-even more aligned with the Ainu of Hokkaido to counteract THAT bullshit. but I can see how different folks would feel differently on that#to me if Canon Bad I can Fix It. but sometimes people don’t wanna touch on bad canon and I think that’s okay too#but like. any reading where he’s this irredeemable conniving emotionless asshole is just. huh. where’d you get that from#cus we certainly didn’t play the same game and honestly? I’ve seen people just straight up admit they haven’t. they’re in it for the twins-#-only so /who cares/ about how they decide to horribly misrepresent volo right? I do fuck off JWBDJSBSKSBSJ#tldr canon was rough to volo and fandom is even worse. I’d just like to try to counteract even a little bit of it#know what sure I’ll add his tag now and see if it shows up wjdbdjdb#volo#LIL TAG ADDITION CUS SOMEONE ASKED: yes it is entirely okay to reblog this! :D#if I ever wanna post smth and have it not be rebloggable I’ll just set it to ‘no one can reblog’ lol no worries!

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Where Do You Get Your Ideas b/w What Are Your Songs About

By the time I'd been in bands for a few years, I could play the songs more or less automatically. I'd pick up the guitar and stand in front of the mic, and start the song, largely without thinking about it—like I was giving in to a potentiality that was already there, like following your normal walking path to school or the subway—and then, a few minutes later, I'd have played the song. I could think about other things when playing the song; I could be high or drunk and still play the song well.

There's something mechanical about this, like riding a bike: you give your body a broad request ("make this bike go forward", "play this song") and it accomplishes the task without attending to the thousands of micro-tasks like remembering the lyrics or the chord changes, or shifting position on the guitar, or where to breathe.

But there's something undeniably magic about it, too, because you're not riding a bike, are you? You're not even performing some other muscle-memory task like hitting a ball or sewing a stitch. I could feel the potential of the song there before it existed, and so could my bandmates, but no one else could. That potential was purely in our minds. When you play music, you are bringing something new into existence and then letting it vanish, note by note. And if you've got a band, you're creating this sound together, reaching back into your shared memories to bring them back into the world, all without making any conscious plan.

That experience isn't there in writing, at least not for me. As much as I enjoy the act of putting words on a page, and can get into a flow, at the end of the day, I'm taking sentences that appear in my consciousness and typing them into a computer. Sure, there's something ineffable about where the ideas—and even words—come from, but that's largely invisible in the finished product. (Though not so much that "Where do you get your ideas from?" isn't a perpetual question of authors. From the unknowable confluence of my accumulated life experiences and the random chance of the day’s shape, my dude!) When we experience writing, as readers, it's not like a concert. We're not watching someone tell an extemporaneous story, even one they've told a hundred times before. We're reading a heavily-edited record of such a performance, many drafts ago.

That's one of the things that makes writing about music so hard: the absolute need to honor that magic of a musical performance, coupled with the absolute inability of writing to convey it in any direct way. I think—and this drives musicians absolutely nuts, I know—the only way to convey that magic is by talking about meaning, even the personal aspects of meaning. By saying what the song makes you, as a listener, think about. This song is about the way country music radio treats women or This song reminds me of riding in a car with my mother or just This song sounds like a cricket stuck in an air vent you can never find. It’s like you’re reverse-engineering those scores that are just instructions, like "Play these sequences in any order, but stop every once and a while and listen"—but instead of taking a text prompt and making music from it, you’re taking a musical prompt and trying to follow its instructions to create a text. It’s an act of translation.

That’s frustrating, because we want texts to be definitive, want them to be the truth. We want to know what the song is about. But all translations are inexact, are based on what the translator brings to it. Sure, it’s constrained by what’s there in the source. But then the rest is all you. What is the song about? Every song is about the same thing: the experience of being inside the song, for as long as it lasts - and what it’s like to be the person who went through that experience. Who heard the notes come into being and then vanish.

9 notes

·

View notes