Video

youtube

13 notes

·

View notes

Link

I argue it is inconsistent to believe that overconsumption is wrong or bad yet believe that having children is morally permissible, insofar as they produce comparable environmental impacts, are voluntary choices, and arise from similar desires. This presents a dilemma for “mainstream environmentalists”: they do not want to abandon either of those fundamental beliefs, yet must give up one of them. I present an analogical argument supporting that conclusion. After examining four attempts to undermine the analogy, I conclude that none of them successfully locates a significant, relevant difference between procreation and eco-gluttony (roughly, consumption exceeding that of the average American). Thus, in order to be consistent, one must be in favour of both or opposed to both. Mainstream environmentalism, then, is not an option,and should be replaced by radical environmentalism, the view that both overconsumption and (in most cases) having children are morally problematic in an overcrowded world.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Wasteland" by Malte Blom Madsen

20 notes

·

View notes

Link

Friedrich Nietzsche is without a doubt one of the most misunderstood and misinterpreted philosophers ever, and now white supremacists and neo-Nazis are using his philosophy (wrongly) for their malicious means.

Infamous white supremacist and alt-righter Richard Spencer talked to the Atlantic back in June, in which he said, “You could say I was red-pilled by Nietzsche.” The term “Red-pilled” is common among alt-righters, which basically means that moment of clarity in which one finally sees the reality and truth after being blinded for so long.

Like the Nazis before, white supremacists like Spencer have hijacked Nietzsche’s philosophy, and turned it into the absolute opposite of what Nietzsche intended. Nietzsche did consider the world to be in constant change, in which there is no absolute truth, add to that his hatred of conventional morality and social restrictions, in which he saw them as crippling the individual and his prosperity.

Nietzsche was also a strong critic of Christianity and its values, he calls it a ‘slave morality’ developed by the weak to sway the powerful.

But there’s a lot more to Nietzsche, every person who dedicated his time to study his philosophy would realize this fact. Most people just read Nietzsche quotes on the internet or maybe one or two books without even giving some thought to what the philosopher is saying. And because of that, a lot of people misinterpret Nietzsche and completely transform his philosophy, and in some radical cases, we get people like Spencer.

It is not hard to see why white supremacists would admire Nietzsche, he has an earth-shattering and rebellious philosophy, in which asks people to consider everything they have been taught and reevaluate their entire moral system. These people want to be rebellious, they think individuals in today’s society are completely brainwashed, and are entirely blind to the facts. They find in Nietzsche a rebel, an outcast, and someone who despises political correctness. All that is true, but what usually happens is that some people start reading Nietzsche in search of what they already believe in, in the case of white supremacists they want to find white pride, nationalism, and anti-Semitism.

Nietzsche is a lot of things, but to anyone who truly understands him and his philosophy, he isn’t an anti-Semitic white nationalist, on the contrary, he is the exact opposite.

But misinterpretation isn’t the only reason white nationalists would appreciate Nietzsche, neo-Nazis today see in Nietzsche the philosopher of Nazi Germany, the philosopher that brought Hitler. But that has Nietzsche’s sister, which was a staunch anti-Semite, to blame for. Nietzsche’s sister was in charge of his estate after he died, and she and her husband, both Nazi sympathizers, rearranged Nietzsche’s notes and essays to produce the infamous, The Will to Power, the book that embraced Nazi ideology. This book made Nietzsche’s sister and her husband closer to Hitler.

But now, who was the real Nietzsche? In short he was a philosopher who despised nationalism, white pride, and anti-Semitism.

In his book Ecce Homo Nietzsche declares:

“This most anti-cultural sickness and unreason there is, nationalism, this nervose nationale with which Europe is sick, this perpetuation of European particularism, of petty politics…a dead-end street.”

Nietzsche also denounced “the blood and soil” politics of Otto von Bismarck, the famous Prussian conservative statesman who unified Germany in 1871, for having a nationalistic approach and calling for racial purity.

Nietzsche despised anti-Semitism, in which later on made him end his friendship with the proto-fascist composer and staunch anti-Semite Richard Wagner.

In his famous book, Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche proposes we:

“Expel the anti-Semitic squallers out of the country.”

In a letter to his sister calling out her anti-Semitism he wrote:“Your association with an anti-Semitic chief expresses a foreignness to my whole way of life which fills me ever again with ire or melancholy.”

And in another draft letter written in the end of December 1887, his sister and her husband Nieztsche wrote :

“I’ve seen proof, black on white, that Herr Dr. Förster has not yet severed his connection with the anti-Semitic movement…Since then I’ve had difficulty coming up with any of the tenderness and protectiveness I’ve so long felt toward you. The separation between us is thereby decided in really the most absurd way. Have you grasped nothing of the reason why I am in the world?…Now it has gone so far that I have to defend myself hand and foot against people who confuse me with these anti-Semitic canaille; after my own sister, my former sister, and after Widemann more recently have given the impetus to this most dire of all confusions. After I read the name Zarathustra in the anti-Semitic Correspondence my forbearance came to an end. I am now in a position of emergency defense against your spouse’s Party. These accursed anti-Semite deformities shall not sully my ideal!!”

Georges Bataille was one of the first to denounce the deliberate misinterpretation of Nietzsche carried out by Nazis, among them Alfred Baeumler. He dedicated in January 1937 an issue of Acéphale, titled “Reparations to Nietzsche,” to the theme “Nietzsche and the Fascists”. There, he called Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche “Elisabeth Judas-Förster,” recalling Nietzsche’s declaration:

“To never frequent anyone who is involved in this bare-faced fraud concerning races.”

White supremacists and neo-Nazis rejoice for finding terms like ‘Aryan humanity’, but little do they know the true meaning of this phrase. Nietzsche uses this phrase in several books, but Aryan here simply is a contrasted term opposing Christian morality, it means pre-Christian Pagan values. Besides Aryan wasn’t in Nietzsche’s time a term used to describe racial purity, in that time it also included Indo-Iranian peoples.

Nietzsche is one of the greatest philosophers to ever live, he certainly has his flaws, but he certainly isn’t a philosopher of white supremacy. Nietzsche was disgusted by anti-Semitism, he condemned blind nationalism, and criticized the absurdity of racial purity. But white supremacists’ love to Nietzsche shows one thing, their intellectual weakness, the fragility of the ground they stand on, and their brainwashing, ironically the brainwashing of the people who proclaim, they were ‘red-pilled’.

38 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Charlotte Gainsbourg - Rest

60 notes

·

View notes

Note

T'es tu genre français français ou canadien français/québécois?

français français

1 note

·

View note

Link

A tiny article about Stoicism has had a significant influence on my life since I read it. Maybe for the first time in my adult life, I don’t feel like I’m wasting much of my time. I feel unusually prepared to do difficult things.

It was a short personal essay by Elif Batuman, about how reading Epictetus helped her through a strained relationship, political turmoil in her country of residence, and other messy or insoluble worldly concerns.

It also prompted me to start reading what are sometimes called the “big three” Stoic works, The Discourses and The Enchiridion by Epictetus, and The Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, who in his spare time was the Emperor of Rome.

I knew the basic idea of Stoicism, and it made sense: don’t freak out about what you can’t control. It’s perfectly logical. But logical isn’t always practical, at least for a species whose members typically can’t even fulfill their own new year’s resolutions.

Humans have never been short on sensible-sounding advice: spend less than you earn, don’t put off till tomorrow what you can do today, be patient, don’t drink coffee after 6pm. What we’re short of is whatever quality it takes to get ourselves to do those things.

But I wasn’t giving the Stoics enough credit. So far, their advice is very practical—more self-improvement suggestions than philosophical ideas.

Basically, Epictetus tells you to continually divide your moment-to-moment concerns into two bins: the things you can control, and the things you can’t. Whenever you feel any sort of anger, desire or aversion, you look at the situation in terms of those two bins.

You quickly notice that the first bin is much, much smaller, and fortunately, it’s the one you’re responsible for. Essentially, it amounts to your actions and choices. The second bin is enormous, and it is the responsibility of the gods.

You can feel free to leave the gods’ enormous bin entirely up to them, as long as you do your best to tend to your small bin of personal choices and habits.

Of course, the larger bin still affects your life, even though you can’t (and shouldn’t try to) curate it. It contains matters such as when and how you die, how others act, the weather, and the stock market.

Obviously we have a stake in how those matters turn out, yet these outcomes aren’t really up to us, and we shouldn’t make ourselves miserable wishing they were. You will be treated unfairly, you will get sick, you will lose everything, and you will die, and the gods (or whatever forces there are) will deliver those fates to you as they please.

Stoicism gives you a very useful refrain towards these the matters that are out of your hands: That is none of my concern. Even in my initial experiments with it, it’s already become pretty easy to dismiss the largest categories of creeping worries, ones along the lines of:

What if ____ happens?

Why can’t ___ just ____?

I just wish _____.

Please let ____ be ____.

None of my concern! I can let the gods sort this stuff out, and attend to whatever actually ends up in my bin.

Our normal impulse is to see misfortune, loss, death, and the choices of others as primary concerns, since they can significantly affect our lives. But this is where the Stoics deviate from our natural inclinations. They offer a bold new take: a thing doesn’t automatically become your concern just because it might affect you.

The gods are doing things all day long that might affect you, but what they choose is their business. So any hoping or worrying you do about the to-do lists of the gods just makes you miserable and wastes your time. Epictetus would say it’s even kind of rude.

According to the Stoics, all day long you should be returning your attention to the relatively small realm you can control. Ultimately, your only concern is your own diligence in tending to your own bin, and that’s always up to you alone.

To the Stoic, life isn’t a juggling act between a thousand competing concerns. You have one concern, and that’s to tend your own garden, small or large as it is. It works the same for a slave (which is what Epictetus was when he was born) as it does for an Emperor (which is what Marcus Aurelius was when he died).

You might think we’re already pretty good at working on what we can control and leaving alone what we can’t. But this isn’t the way the untrained human mind works—we tend to ruminate over whatever we find emotionally compelling, from either sphere. If a politician does something we don’t like, we could burn unlimited energy getting enraged, even when we have no intention, or ability, to alter the proceedings. It’s possible to waste your whole life essentially shaking your fist at the clouds, completely preoccupied with where you are disempowered, overlooking every way in which you are empowered.

By reclaiming your energy, all day every day, from your sphere of concern (the range of things that appeal to your emotions) to your sphere of influence (the range of things you can affect) you are continually developing the essential Stoic skill of taking your lumps as they come, with minimal fuss and tantrum.

One way to think of it it is that the Stoic is making a practice out of shrinking the sphere of concern down to roughly the same size as the sphere of influence, where it finally becomes manageable.

As hard as life is, the only refuge you need, or ever have, is your own will to do what you can within your own sphere. That’s all you need to attend to, all you need to think about, all you need to get good at. You carry this refuge with you wherever you go, and nobody can take it away.

The practice of Stoicism is new to me, but its central insight isn’t. Buddhism has an almost identical interpretation of the human condition: our lives are vastly harder than they need to be, but only because we grasp at more control than is actually available to us.

I’ve been sold on this idea for years now—that happiness doesn’t come from finally learning how to control everything, but from finally learning how not to.

A passage from the Batuman article sums up this sense of carrying your empowerment with you, wherever you go:

When I read that nobody should ever feel ashamed to be alone or to be in a crowd, I realized that I often felt ashamed of both of those things. Epictetus’ advice: when alone, “call it peace and liberty, and consider yourself the gods’ equal”; in a crowd, think of yourself as a guest at an enormous party, and celebrate the best you can.

Source: Raptitude

40 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I have lived through much, and now I think I have found what is needed for happiness. A quiet secluded life in the country, with the possibility of being useful to people to whom it is easy to do good, and who are not accustomed to have it done to them; then work which one hopes may be of some use; then rest, nature, books, music, love for one’s neighbor—such is my idea of happiness. And then, on top of all that, you for a mate, and children perhaps—what can more the heart of man desire?

Leo Tolstoy

17 notes

·

View notes

Link

Nearly two and a half millennia ago, Aristotle triggered a revolution in happiness. At the time, Greek philosophers were trying hard to define precisely what this state of being was. Some contended that it sprang from hedonism, the pursuit of sensual pleasure. Others argued from the perspective of tragedy, believing happiness to be a goal, a final destination that made the drudge of life worthwhile. These ideas are still with us today, of course, in the decadence of Instagram and gourmet-burger culture or the Christian notion of heaven. But Aristotle proposed a third option. In his Nicomachean Ethics, he described the idea of eudaemonic happiness, which said, essentially, that happiness was not merely a feeling, or a golden promise, but a practice. “It’s living in a way that fulfills our purpose,” Helen Morales, a classicist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, told me. “It’s flourishing. Aristotle was saying, ‘Stop hoping for happiness tomorrow. Happiness is being engaged in the process.’ ” Now, thousands of years later, evidence that Aristotle may have been onto something has been detected in the most surprising of places: the human genome.

The finding is the latest in a series of related discoveries in the field of social genomics. In 2007, John Cacioppo, a professor of psychology and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago, and Steve Cole, a professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, among others, identified a link between loneliness and how genes express themselves. In a small study, since repeated in larger trials, they compared blood samples from six people who felt socially isolated with samples from eight who didn’t. Among the lonely participants, the function of the genome had changed in such a way that the risk of inflammatory diseases increased and antiviral response diminished. It appeared that the brains of these subjects were wired to equate loneliness with danger, and to switch the body into a defensive state. In historical and evolutionary terms, Cacioppo suggested, this reaction could be a good thing, since it helps immune cells reach infections and encourages wounds to heal. But it is no way to live. Inflammation promotes the growth of cancer cells and the development of plaque in the arteries. It leads to the disabling of brain cells, which raises susceptibility to neurodegenerative disease. In effect, according to Cole, the stress reaction requires “mortgaging our long-term health in favor of our short-term survival.” Our bodies, he concluded, are “programmed to turn misery into death.”

In early 2010, Cole spoke about his work at a conference in Las Vegas. Among the audience members was Barbara Fredrickson, a noted positive psychologist from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who had attended graduate school with Cole. His talk made her wonder: If stressful states, including loneliness, caused the genome to respond in a damaging way, might sustained positive experiences have the opposite result? “Eudaemonic and hedonic aspects of well-being had previously been linked to longevity, so the possibility of finding beneficial effects seemed plausible,” Fredrickson told me. The day after the conference, she sent Cole an e-mail, and by autumn of that year they had secured funding for a collaborative project. Fredrickson’s team would profile a group of participants, using questionnaires to determine their happiness style, then draw a small sample of their blood. Cole would analyze the samples and see what patterns, if any, emerged.

Fredrickson believed that hedonism would prove more favorable than eudaemonia—that discrete feelings of happiness would register on the genome more powerfully than abstract notions of meaning and purpose. Cole, meanwhile, was skeptical about the possibility of linking happiness and biology. He had worked with all kinds of researchers, trying to find a genomic response to everything from yoga to meditation to tai chi. Sometimes he made quite interesting findings, but more often the data provoked only a shrug. “Day after day, I see null results,” he told me. “Nothing there, nothing there, nothing there.” Fredrickson and Cole’s first study wasn’t huge, containing usable results from eighty people, but, because Cole had been studying misery for so long, he knew what to look for in the blood samples. “By this time, we had a pretty clear sense of the kinds of shifts in gene expression we see when people are threatened or uncertain,” he said. “We were in a good position, even in a relatively small study, to say, ‘These are the outcomes I’m going to look at.’ ”

When they parsed the data, they saw that Fredrickson’s prediction appeared to be wrong. “This whole hedonic well-being stuff—just how happy are you, how satisfied with life?—didn’t really correlate with gene expression at all,” Cole said. Then he checked the correlation with eudaemonic happiness. “When we looked at that, things actually looked quite impressive,” he said. The results, while small, were clearly significant. “I was rather startled.” The study indicated that people high in eudaemonic happiness were more likely to show the opposite gene profile of those suffering from social isolation: inflammation was down, while antiviral response was up. Since that first test, in 2013, there have been three successful replications of the study, including one of a hundred and eight people, and another of a hundred and twenty-two. According to Cole, the kind of effect sizes that are being found indicate that lacking eudaemonia can be as damaging as smoking or obesity. They also suggest that, although people high in eudaemonic happiness often experience plenty of the hedonic stuff, too, the associated health benefits tend to surface only in those who lead what Aristotle might have called a good life.

But what, precisely, is this quasi-mythical good life? What do we mean when we talk about eudaemonia? For Aristotle, it required a combination of rationality and arete—a kind of virtue, although that concept has since been polluted by Christian moralizing. “It did mean goodness, but it was also about pursuing excellence,” Morales told me. “For Usain Bolt, some of the training it takes to be a great athlete is not pleasurable, but fulfilling your purpose as a great runner brings happiness.” Fredrickson, meanwhile, believes that a key facet of eudaemonia is connection. “It refers to those aspects of well-being that transcend immediate self-gratification and connect people to something larger,” she said. But Cole noted that connectedness doesn’t appear to be an absolute precondition. “It seems unlikely that Usain Bolt is doing what he does to benefit humanity in any simply pro-social sense,” he said. “If that’s the case, is eudaemonic well-being mostly about the stretched goal, doing something you personally think is amazing or important? Or does it involve something more around pro-social behavior?” For Cole, the question remains open.

A further tantalizing clue might come from a distant corner of the academy. Since the early nineteen-seventies, the psychologist Brian R. Little has been interested in what he calls personal projects. He and his colleagues at Cambridge University, he told me, have “looked at literally tens of thousands of personal projects in thousands of participants.” Most people, Little’s work suggests, have around fifteen projects going at any time, ranging from the banal, like trying to get your wife to remember to switch off your computer once she’s used it (that’s one of mine), to the lofty, like trying to bring peace to the Middle East. Little refers to this second category as the “core” projects. One of his consistent findings is that, in order to bring us happiness, a project must have two qualities: it must be meaningful in some way, and we must have efficacy over it. (That is, there’s little use trying to be the fastest human in the world if you’re an overweight, agoraphobic retiree.) When I described Cole and Fredrickson’s research, Little noted that it was remarkably congruent with his ideas. As with eudaemonia, though, the precise definition of a core project is malleable. “Core projects can increase the possibilities for social connection, but not necessarily,” Little said. It all depends on an individual’s needs. “A Trappist monk’s core projects don’t require the same kind of connection as an everyday bloke from Birmingham.”

Indeed, this malleability is perhaps the most encouraging quality of both Little’s core project and Aristotle’s eudaemonia, because it makes finding happiness a real possibility. Even the most temperamentally introverted or miserable among us has the capacity to find a meaningful project that suits who we are. Locating it won’t just bring pleasure; it might also bring a few more years of life in which to get the project done.

74 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Let everything that's been planned come true. Let them believe. And let them have a laugh at their passions. Because what they call passion actually is not some emotional energy, but just the friction between their souls and the outside world. And most important, let them believe in themselves. Let them be helpless like children, because weakness is a great thing, and strength is nothing. When a man is just born, he is weak and flexible. When he dies, he is hard and insensitive. When a tree is growing, it's tender and pliant. But when it's dry and hard, it dies. Hardness and strength are death's companions. Pliancy and weakness are expressions of the freshness of being. Because what has hardened will never win.

Stalker, Andrei Tarkovsky

165 notes

·

View notes

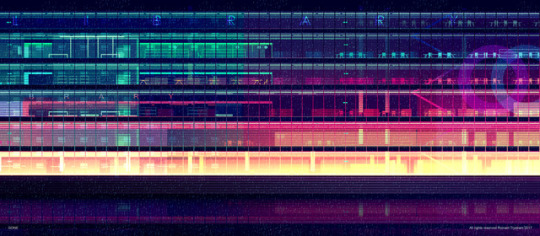

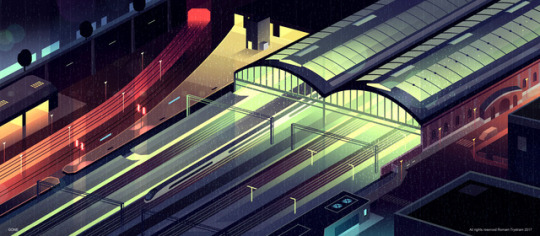

Photo

"Gone" by Romain Trystram

414 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Meigetsu-in Temple, Kamakura

MEIGETSU TEMPLE (2015)

A video recording of a walk through the temple gardens, which captures one of the most compelling attributes of Japanese landscape architecture: the sense that, even in a small space, each individual step can open up a new vista, a new perspective.

2K notes

·

View notes

Link

So, Dark Souls is a special game, a rare kind of game that is only released a few times a console generation. Past its ecstatic gameplay and thick aesthetic, though, its theme of the futility of physical identity particularly striking. There exists in the world of Dark Souls two opposing forces, the gods, the lords, who seek to keep the Age of Fire going, and those that oppose those gods, who seek to bring about an Age of Darkness, where, interestingly, man holds his destiny in his own hands. Beyond these two archetypal forces is a third, vague energy that persists over Lordran, a rotting, indifferent predetermination, which can be read as the developer’s hand in the game, but does not have to be. This is the force that kills players mercilessly, the force that fills every pool of water with poison and bones. It is also the force that dethrones the idiot gods, as even their control over nature is limited. Strangely, due to this third force, this cosmic weight, it would be curious to see how Lordran transforms if a godless age was brought about, as the gods themselves have nothing to do with the paradoxical cosmic indifference and free-will erasing predeterminism. Would man bring about a prosperous Lordran? The game seems to lead one to believe this.

Being alive in Dark Souls is a weakness, and existing at all is a pretty awful, meaningless trial. It is a rampant landscape of existential and, in particular, moral nihilism. Søren Kierkegaard’s (1813-1855) ideas on nihilism, which he referred to as leveling (sort of ironic in the context of an RPG). Leveling, “at its maximum,” to Kierkegaard was the process of suppressing individuality to the point where individuality loses all meaning, and “is like the stillness of death” in his words. Interestingly, Kierkegaard uses similar language to that found in Dark Souls. The individuals of Lordran, the Solaires and the Knights of Astora, are punished for their wills, and turned into the Hollowed, a meaningless, violent existence. The player character can occasionally “save” one of these NPCs, but the obscure methods of doing so only emphasize the futility of the situation.

Relationships between characters are equally meaningless and violent, as the player character can kill any NPC whenever the player wills it, join any religious covenant which is not indicative of any real faith, and be attacked by a false friend at any moment. The religions of Lordran and the very gods themselves are meaningless and hold no real power as no such power or faith truly exists. PvP players act as unknown assassins, invading worlds they have never been to just to kill and purge.

Dark Souls is a world without sex and a world without love. Deep in the lore are buried lovers, yes, but love can never be depended on for tenderness or meaning. Upon death, players are forced to retrieve their bloodstains to retrieve their souls and humanity. Souls and humanity are not metaphysical notions but bodily ones, being represented by bloody pools on the ground marking death. Souls and humanity are reduced to items, currency, and hold little spiritual or existential value.

There have been a plethora of great heroes who have faced the materialist JRPG-hellworld, including the original JRPG hero, the legendary hero of Erdrick of Dragon Quest fame, but the player character in Dark Souls is a bit different. Erdrick, like the player character in Dark Souls, fought off mindless enemies full of gold and trudged through poisonous marshes and over beds of spikes. However, like most RPG heroes, Erdrick made little in the way of moral decisions. He was tasked with saving the kingdom and vanquishing evil, and that’s what he did. He used the King of Tentegel Castle’s save features, and other JRPG heroes used an inn’s save features, or a church’s. There are rules and roles in place, JRPG tropes.

The story of the player character in Dark Souls is a much more vague affair, where every action is morally ambiguous, but not in the way of other open-world games. The player character is a shapeshifter, much like the protagonist in A Voyage to Arcturus, and a killer, who could kill the King of Tentegel Castle with no remorse just to get a rare drop, sacrificing the game’s save feature in the process. There is no karma system to guide players’ actions, nor are there any real cues to let players know what they are doing is immoral.

Since Lordran is a morally nihilistic nightmare, the player character emerges as something of an existential hero. For Camus, in his The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), an unintelligible world devoid of God and eternal values poses only one question: does the realization of the absurd require one to commit suicide? Such a hyperbolic question deserves an equally hyperbolic answer: “No. It requires revolt.”

It could be argued that the player character is the Chosen Undead, that he or she is destined for this quest as the prophecies in the lore dictate. The player character therefore has no free will as fate predestines he or she be the legendary hero despite whatever he or she may actually seek. From this reading of the lore, the player character then is nothing of an existential hero, but merely a pawn in the plot of Lordran’s history. But this is not the case. From a more accurate understanding of the metaphysics of Lordran, no fate willed the player character to do anything. Obviously, characters like Kingseeker Frampt try to guide the player characters’ actions, and characters like the Knight of Astora are catalysts for the player character’s adventure, but it is the player character who eventually stands up to the indifferent world of Lordran and its idiot gods, proclaiming himself free of their laws and the natural laws that plague existence. The player character never becomes fully Hollowed and is ultimately in charge of his own destiny.

For Sartre, since there is no Creator, there is no specific human nature or eternal truths imbued in humans, what he refers to as essence. His famous quote, “existence precedes essence,” means that people are fully responsible for their actions and that they have no inherent properties willed upon them. This can be seen in Dark Souls in the bloodstains left behind when players die. Their existence (blood, body, physicality and actions) is how they are measured and to be whole is to reclaim that. Their essence (soul, humanity) is important to the game, but it is merely a currency with no intrinsic value associated with it. There is nothing moral about holding onto souls and humanity, and their value is only measured in what they can buy. The gods of Lordran (the lords) are not true creators as there are none, save the game developers, the third force mentioned earlier.

Thus, the player character, faced with an absurd, meaningless existence, without essence in a world without justice, explores Lordran, amasses power by killing those the player deems worthy of killing, and eventually discovers an option to change Lordran, an option essentially devoid of morality.

10 notes

·

View notes