#1842 fashion

Photo

Marie Caroline Auguste de Bourbon-Siciles, duchesse d'Aumale —

Top row left: 1842 Marie Caroline Auguste de Bourbon-Siciles, later Duchesse d'Aumale by Josef Kreihuber (Musée Condé - Chantilly, Oise, Hauts-de-France, France) photo - Adrien Didierjean. From Reunion des musées nationaux; enlarged by half 810X985 @154 140kj.

Top row right: 1842 Princess Maria Carolina of Bourbon-Two Sicilies at the Age of 20 by Franz Schrotzberg (Musée Condé - Chantilly, Oise, Hauts-de-France, France). From pinterest.com/bjornolofkihlbe/art-austrian-artists/franz-schrotzberg/ 980X1069 @72 144kj.

Second row left: 1845 Maria Carolina of Bourbon-Siciles by François Meuret (Musée Condé - Chantilly, Oise, Hauts-de-France, France). From Wikimedia; doubled size 806X994 @96 139kj.

Second row right: 1846 Marie-Caroline-Auguste de Bourbon-Siciles, princesse de Salerne Duchesse d'Aumale by Meuret (Musée Condé - Chantilly, Oise, Hauts-de-France, France). I got this before I recorded sources; posted to another site in April 2010.

Single images from top to bottom -

Maria Carolina, Duchess of Aumale, née Princess of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, with her eldest son, Louis, Prince of Condé by ? (location ?). From tumblr.com/blog/view/bespridannitsa 855X1200 @72 515kj.

1851 Marie Caroline Auguste de Bourbon-Siciles by Victor Mottez (Musée Condé - Chantilly, Oise, Hauts-de-France, France). From Google search 615X1191 @72 171kj.

ca. 1854-1855 Miniature of the duchesse with the prince de Condé and with the duc de Guise on her lap, by Sir William Ross (location ?) From godsandfoolishgrandeur.blogspot.com/ 750X980 @300 1.4Mp.

1865 Duchesse d'Aumale by Adolphe Beau (Musée Condé - Chantilly, Oise, Hauts-de-France, France). I did not record sources when I found this; posted to another site in April 2010.

1865 Marie Caroline, duchesse d'Aumale by Mayer Brothers. From eBay. pots and flaws were removed from all parts of the image. A small part of the ground she stands on was teased out from the spots and extended all around the hem of her skirt 940X1421 @1 510kj.

1866 Marie Caroline Auguste de Bourbon-Siciles by Charles Jalabert (Musée Condé - Chantilly, Oise, Hauts-de-France, France). From Wikimedia; removed more conspicuous spots & flaws with Photoshop & cropped right margin 1498X2359 @762 1.4Mj.

#Romantic era fashion#early Victorian fashion#1840s fashion#Marie Caroline Auguste de Bourbon-Siciles#duchesse d'Aumale#1842 fashion#Josef Kreihuber#straight hair#chignon#bertha#bow#quarter-length close sleeves#puffed cuffs#V waistline#full skirt#Franz Schrotzberg#hair flowers#modesty piece#scoop neckline#off shoulder neckline#pleated bertha#V neckline#floral bodice ornament#ruching#wrap#sheer wrap#1845 fashion#François Meuret#side braid coiffure#sheer cuffs

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

1842

#1842#circa 1840#1840s fashion#1840s#historical fashion#fashion#historical#history#historical clothing#historical dress#long dress#victorian#victorian era#victorian fashion#historical costuming#historical costume#victorian history#victorian pattern#victorian clothing#victorian dress#textile#textiles#plate#fashion plate#fashion dress#old fashioned#high fashion#19th century fashion#mid 19th century#19th century

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

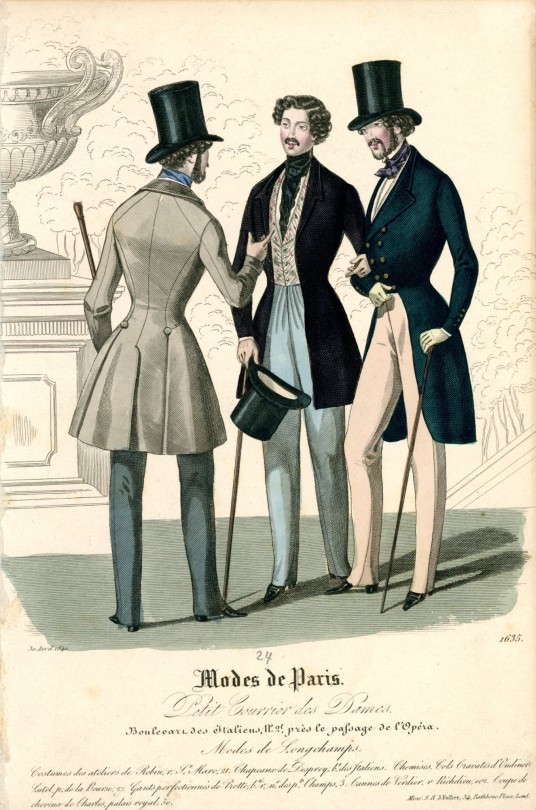

Is he... you know... dressed for Longchamps?

Petit Courrier des Dames, April 30, 1842.

#Eighteen-Forties Friday#1840s#fashion history#historical men's fashion#1842#fashion#victorian#monarchie de juillet#fashion plate#men's fashion#modes de longchamps

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bridal Shirt

Linen shirt decorated almost entirely in cross stitch, except for the collar which is done with pattern darning (smøyg) and some minor details.

Made in 1842, Bø, Telemark.

Photo: Anne-Lise Reinsfelt - Norsk Folkemuseum

"S H D I" "1842"

Smøyg collar and buttonhole up close.

#shirt#1842#1840s#fashion history#cross stitch#bridal#wedding#smøyg#pattern darning#linen#telemark#bunad

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hard

What’s your favorite candy?

Don’t have proper way to answer.

Take Care!

Smile Always!

Stay Happy and Healthy!

Pray!

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Late Victorian and Edwardian fashion in portraits by Giovanni Boldini (Italian, 1842-1931)

#these gowns are stunning#art#Giovanni Boldini#fashion history#paintings#art history#art detail#painting detail#women in art#classical art#painting#Edwardian era#1900s fashion#1900s art#italian art#paintings set#dark academia art#light academia#illustration#art on tumblr#20th century art#historical dress#historical fashion#Victorian art#victorian fashion

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

Knitting in Victorian England

I wrote this for a class on Victorian Literature because my professor let me research knittinf and make a cape instead of writing a literary analysis paper. The cape that is discussed from The Art of Knitting is what I created for this project, with the illustration from the book on the top right and the cape I knit on the left. The book is from 1892 and is free on Internet Archive, and Engineering Knits on YouTube made a wonderful video about it. (More photos of the cape at the end!)

Knitting experienced a surge of popularity in Victorian England, and was even a topic of discussion in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre. After gaining popularity due to industrialization, knitting became a common pastime for women. Knitting was important because it existed as a way for Victorian women of all classes to be seen as virtuous and gave them the look of domesticity, while additionally functioning as a means of income for working-class women by either knitting or writing about knitting.

Industrialization shifted the view of knitting from economic necessity to a fashionable pastime for gentry women. In 1589 the first mechanical knitting machine was invented in Nottingham, which industrialized the knitting industry (“The History of Hand-Knitting"). Dyed wool trade with Germany and the subsequent booming industry of knitting pattern books turned knitting into something more accessible and artistic than solely practical (Rutt 112). Knitting became popular and fashionable for gentry women around 1835 (Rutt 111). Women of all classes have knitted long before the Victorian period, but the industrial changes shifted knitting to a popular and fashionable pastime for gentry women, in addition to the economic necessity for working-class women.

Knitting served as a way to keep women wholesomely busy. In The Art of Knitting, a quote from the beginning by Richter reads “A letter or a book distracts a woman more than four pair of stockings knit by herself” (qtd in The Art of Knitting 2). Knitting kept women busy without opening them up to new ideas that came from letters and books. Furthermore, a writer in The Magazine of Domestic Economy writes how useless the items (upper-class) women made were, but praises knitting in its effort “to rid of those hours which, but for their aid, might not be so innocently disposed of” (qtd in Rutt 112). Concentrating on knitting produces something at the end of the hours of challenging work but does not expose women to any material that the Victorians would deem dangerous or immoral. Thus, even when women made something useless, they were keeping themselves busy in a virtuous way.

Knitting also gave women the feminine and domestic look that was expected of them in the Victorian era. This can be seen in Jane Eyre with Jane’s description of Mrs. Fairfax upon their meeting. Jane thinks, “[Mrs. Fairfax] was occupied in knitting; a large cat sat demurely at her feet; nothing in short was wanting to complete the beau-ideal of domestic comfort” (Bronte 145). This is the first time the reader sees Mrs. Fairfax, surrounded by a warm fire, a cat and engaged in a feminine pastime. She is the image of domesticity. Jane admires Mrs. Fairfax, in part, for the comfort her nature, including knitting, brings. Mrs. Fairfax shows the role knitting plays into the idea of women as domestic creatures.

Certain forms of knitting made women appear elegant. Frances Lambert, author of 1842 manual The Handbook of Needlework, advises women to knit using the common Dutch knitting method, in which the yarn is held over the fingers of the left hand and the needles pointed upwards, because it was seen as a more elegant style of knitting (Rutt 113). While Rutt notes that this method was a faster way of knitting, Lambert does not comment on this, but instead focuses on its aesthetic qualities. This style of knitting was popular because it allowed for the look of style that was mandatory in women’s lives.

While gentry women were often restricted to making less practical knit items, some knitting authors disparaged this for frivolity and immorality. Working-class women did not have this criticism as the things they made were out of practicality and meant for regular use. In picking yarn color and material, Mlle Riego de la Branchardiere, author of Ladies Handbook of Knitting, Netting and Crochet writes “...and let her be careful to make all she does a sacrifice acceptable to her God” (qtd in Rutt 116). Rutt asserts that although Victorian knitting is seen as producing useless knits, some authors disparaged this (117). They instead encouraged women to focus on what they saw as the spiritual aspects rather than on aesthetics, as everything women did, including knitting, should enhance their virtue.

While knitting was popular as a pastime, it was still used out of economic need and served as a way for working-class women to earn money. Knitting was taught in orphanages and poor houses, with the first knitting school opened in Lincoln, Leicester, and York in the late 1500s. One school in Yorkshire was established for boys and girls who were “not in affluence” (“The History of Hand-Knitting"). The first knitting book, titled The National Society's Instructions on Needlework and Knitting, published in 1838, was an instructional manual for teachers to teach poor students the art of knitting and needlework. Knitting was used as a personal hobby, but also as a way for working-class people to support themselves.

The importance of knitting to working-class women can be seen in Jane Eyre. St John tells Jane, “It is a village school: your scholars will be only poor girls—cottagers’ children—at the best, farmers’ daughters. Knitting, sewing, reading, writing, ciphering, will be all you will have to teach” (Bronte 541). Knitting will be a way for these young girls to get jobs and to be able to make clothes for themselves and their families. In this way, knitting was more than a fashionable and artistic hobby, but a necessity for many working-class women.

In addition to manufacturing knitwear, women were able to make substantial livings writing about knitting. There was a boom in knitting and needlework publications during the 19th century (“The History of Hand-Knitting"). Some, such as The Art of Knitting, were published directly by publishers with no one associated author. Others were authored by women and were immensely successful. Cornelia Mee, who published shorter pamphlet-type knitting books, sold over 300,000 copies during their run in print (Rutt 115). Francis Lambert, author of two editions of My Knitting Book, sold a combined 65,000 copies and was translated into several languages across Europe (Rutt 113). Knitting gave working-class women opportunities to earn money, whether it was making knitwear or writing about knitting.

Knitting manuals contained various topics, such as some focusing on the religious and virtuous aspects of knitting as discussed previously, but most, if not all, had patterns in them. Under the chapter “Hoods, Capes, Shawls, Jackets, Fascinators, Petticoats, Leggings, Slippers, etc., etc.” in The Art of Knitting there is a pattern to knit a cape. Victorian knitting patterns tended to be broad and vague. Today's patterns are quite concerned with needle size and gauge, unlike many Victorian patterns. For instance, the cape pattern instructs the reader to “use quite coarse needles and work rather loosely,” (60).

Knitting was an important skill for women in the Victorian era, and they knit for a multitude of reasons. Knitting gave women the look of virtue, elegance, and domesticity. Working-class women used their knitting skills to support themselves and their families through making knitwear or writing about knitting.

Sources:

The Art of Knitting. The Butterick Publishing Co. 1892. https://archive.org/details/artofknitting00butt/page/60/mode/2up?ref=ol&vi ew=theater

Bronte, Charlotte. Jane Eyre. Planet eBooks. 1847.

“The History of Hand-Knitting" Victoria and Albert Museum.

Rutt, Richard. A History of Hand Knitting. Interweave Press. 1987. https://archive.org/details/historyofhandkni0000rutt/page/n7/mode/2up?vie w=theater

#knitting#historical knitting#history bounding#Victorian knitting#knitting history#cottagecore#victorian#knit cape#gothic#slow fashion#handmade#my knits

164 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I am catching up on les mis letters and I think the October 7(???) chapter mentions that none of the les amis are wearing ties. Can you tell me the significance of this? I know nothing of FRev ✌️

Sure! I assume you mean this line:

They reached the Quai Morland. Cravatless, hatless, breathless, soaked by the rain, with lightning in their eyes.

A quick Obligatory Mention that Les Mis is not set in the French Revolution, but in the post-Republic years of the early 19C ! Which is of course mostly relevant here because instead of imagining a bunch of sans culottes

(1842 black and white art of two sans culottes, rather pretty and idealized, by Emilé Wattier)

( a color picture of a sans culotte on the left and maybe far right, with a culottes-wearing drummer between them. All are wearing phrygian caps and republic cockades, and seem to be going off to fight together)

You're instead looking at a group more like this, Fashionwise:

Révolution de 1830 - Combat devant l'hôtel de ville , an idealized portrayal of revolutionaries in 1830, fighting outside the Hotel de VIlle, by Jean-Victor Schnetz (you can really zoom in on it at the Wiki page!)

I wanted to bring that--again, highly idealized -- pic of 1830 in because it shows not just what people were wearing, more or less, but how that was being socially interpreted!

You've got a lot of different hats here--top hat, workers' caps, bandanas, soldier's hats, etc. And IDK how much you know about fashion in this era, Nonny, but I bet you can start picking out a pattern to who's wearing what.

Especially the way that cravatlass people in workers' caps and bandanas and Phrygian caps are, by and large, turned away from the camera, or have their faces in shadow, while the composition leads us to a central, heroic figure--a student-type in obvious Fashionably Respectable clothes, with a great big cravat. There's even an older man in a nice top hat, with a saber, looking and gesturing to him! THIS is our Central Guy, a good bourgeois type the presumed viewer can feel safe with! Even the heroic worker (hat apparently missing, but he's in overalls, then as now a garment linked with labor) who's swooning into the central student's arms has his eyes shadowed , though at least we see most of his face.

You could write a whole paper on this painting alone, but the barebones relevance here: a bourgeois audience is going to have very different reactions to people who are visibly of Their Class than the scaaaaary, faceless Working Class. And in the real world where combat and crowds aren't as neat and shiny as this painting and the little details like shoes and socks and fit of the trousers and so on is going to get lost in the dust and distance, one of the easiest ways to read a man's social status is hats and cravats -- who's wearing them , what sort are they wearing, etc.

So on an immediate, practical, level , losing the hats and cravats is a bit like "rolling up your sleeves"-- ditching or loosening restrictive clothing before doing hard physical work. But on a social/symbolic level, it's a way of erasing differences of status and social standing between the barricade fighters. Hats gone, cravats gone, everyone soaked by rain and covered in mud, there's no easy distinction between Enjolras and Feuilly--or between a porter and a poet.

Which is all very egalitarian and symbolic and all--but to the sort of reader/ viewer who the painting up there is targeting, it's also very scary, because now there's no obvious sympathetic "leader", no easily-spotted reassuring figure to make them think it's all being organized by the Right Sort of people. It's just a scary,lower-class, undifferentiated mob.

Both these factors, the symbolic equality and the perceived mob nature of the uprising, are very relevant to the rebellion in Les Mis!

..and also it's just SUPER awkward to try and do hard physical work with a tight binding loop of fabric around your throat, or without losing most hats. The Struggle is Real, there.

#what do I even tag this#uh#The Barricades#fashion on the barricades#this was a GOOD QUESTION Nonny sorry if it is kind of a Lot of Answer XD

69 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (French, 1755-1842)

Marie Gabrielle de Gramont, duchesse de Caderousse, 1784

Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City

Madame la Comtesse was the daughter of the Marquis de Sinety and was betrothed to her husband, who was the eldest son of the Marquis de Vachères, in 1779 in a ceremony that took place at Versailles and was witnessed by several members of the royal family. Marie Gabrielle was formally presented at court after her wedding that summer and swiftly became one of Marie Antoinette’s closest friends. She escaped the revolution and became Duchesse de Caderousse when her husband inherited the title in June 1800.

Although women of the Comtesse’s class usually wore their hair powdered, Vigée Le Brun persuaded her to be painted with her hair in its natural state, which caused a furore when she went to the theatre straight after one of her sittings. ‘I could not stand powdered hair,’ the artist later recalled in her memoirs. ‘I persuaded the beautiful Duchesse de Grammont-Caderousse not to use any for her portrait. Her hair was ebony black… arranged in irregular curls. After the sitting, which finished at the time of the midday meal, the Duchesse left her hair as it was and went to the theatre as she was. Such a lovely woman had to set the fashion, which gradually caught on and became widespread.’

-Madame Guillotine

#Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun#art#french art#frabce#1700s#classical art#female portrait#female#portrait#portrait of a lady#lady#marie gabrielle de gramont#duchess#noble#nobility#european art#european nobility#french aristocracy#Aristocracy#aristocrat#france#Mediterranean#europe#europa#european#1800s#marie antoinette#french history#world history#historical art

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fashion Showdown: Brown (Match 4)

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

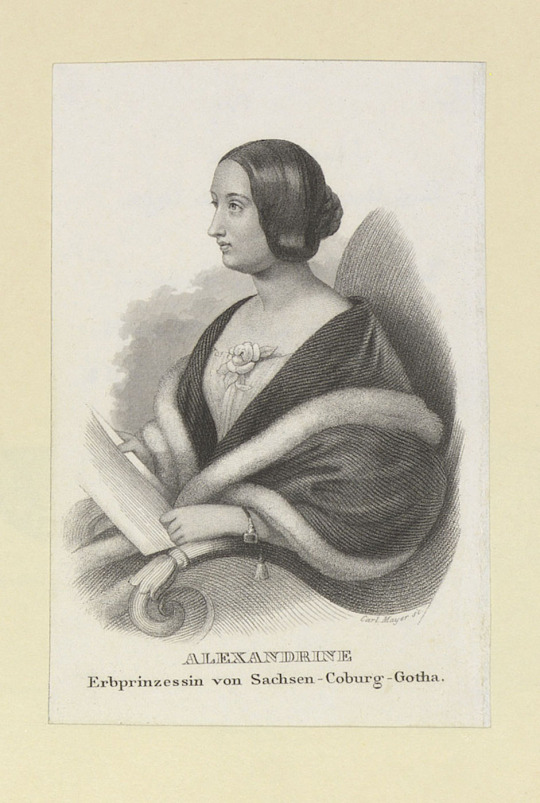

Alexandrine of Baden, Duchess of Saxe-Coburg und Gotha. She was married to Ernst whose brother Albert was married to Queen Victoria. (Top to bottom) -

ca. 1840 (based on estimated age of subject) Alexandrine of Baden, Duchess of Saxe-Coburg und Gotha by ? (location ?). From the lost gallery's photostream on flickr 822X1245 @300 339kj.

1842 Princess Alexandrine of Baden by Franz Xaver Winterhalter (Royal Collection). From Wikimedia; removed spots & cracks w Pshop (1249X1500 @72 671kj.

1842 Alexandrine, Erbprinzessin von Sachsen-Coburg-Gotha by Carl Mayer (Royal Collection - RCIN 610107). From their Web site; removed spots and print w Pshop & changed size to screen 941X1400 @300 370kj.

1844 Ernst II. und Alexandrine von Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha nach der Jagd by Raden Saleh (Schloss Ehrenburg - Coburg, Bayern, Germany). From Wikimedia search; expanded to screen 1867X1400 @72 902kj.

1848 Alexandrine of Baden by Sir William Charles Ross (Royal Collection). From Wikimedia; removed spots with Photoshop 1095X1392 @300 398kj.

1854 Alexandrine, Duchess of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha by ? (Royal Collection - RCIN 2906579). From their Web site 1528X2000 @300 813kj.

1860 Alexandrine, Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha by ? (Royal Collection - RCIN 2907553). From their Web site; removed spots w Pshop and momo-color tint 1159X1916 @300 421kj.

#early Victorian fashion#Romantic era fashion#Biedermeier fashion#1840s fashion#1850s fashion#Alexandrine of Baden#Duchess of Saxe-Coburg und Gotha#straight hair#center part#floral headdress#lace bertha#corsage#full skirt#V waistline#Franz Xaver Winterhalter#lace wrap#1842 fashion#Carl Mayer#chignon#fur-trimmed wrap#1844 fashion#Raden Saleh#1848 fashion#William Charles Ross#high neckline#lace collar#brooch#long close sleeves#lace cuffs#natural waistline

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

I know you've read a lot of personal narratives from people involved in the Ross Antarctic Expedition. Are there any passages you can recall that either made you laugh out loud or yell "No you fool!!" at a long-deceased man?

This is such a fun question, thank you!

Maybe less "No you fool!!" and more "Get some sleep you fool!!" but this passage from Ross's narrative stuck out to me recently:

Soon after 6 A. M., when within half a mile of this chain of bergs, the weather came so thick, with heavy snow, and the wind failing us, Lieutenant Bird, whom I had left in charge of the conduct of the ship, being myself unable to remain on deck any longer from excessive fatigue, very judiciously recommended that we should stand off again until more favourable weather for our purpose should arrive.

Not strictly a narrative, but a while ago I had the opportunity to read some of the letters sent to Joseph Dalton Hooker in the archives of the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew, including some notes that people sent back and forth between the ships while they were in the Antarctic. J.E. Davis's notes, in particular, were full of banter, and this passage (dated December 1842) always makes me laugh:

You make some vile unladylike allusions in your note about my writing badly and wanting stops &c together with a base insinuation about a vulgar pipe and taking a draw at it - Because you have been to a Sunday School it is no reason you should upbraid me and bring me into a vile comparison with your truly disgusting-and-ever-to-be-despised self - I own I do not write well and do not disguise my ignorance under the guise of fashion like yourself Oh! the ingratitude of the world after teaching you every accomplishment and trying (against your nature) to make you a gentleman to turn like a snake or a vile "surpint" and bite with pisoned [sic] fangs the breast that nourished and brought you to life Oh! it is too much Gas.

And though I've posted about them before, I have to mention John Robertson's description of Ross and Crozier landing on Franklin Island, and Hooker grousing about how St. Helena is a Napoleonic tourist trap, both of which are comedy gold.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

What all of us want: a new novel to read, a young lover, and an old pipe.

#smoking is bad but some of you are hitting that old pipe anyway#paul gavarni#1840s#art#la vie de jeune homme#1842#fashion

69 notes

·

View notes

Photo

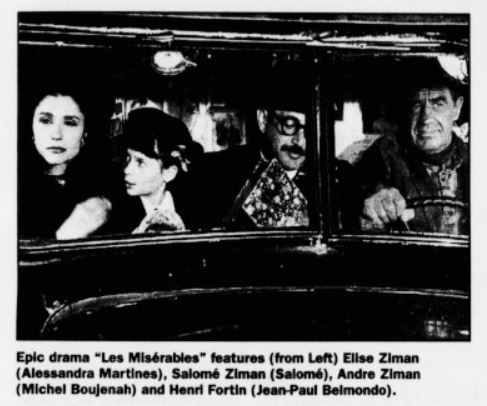

Source: The Jewish News of Northern California, 10 November 1995

With a three-hour running time and the pedigree of one of the most famous books in French history, the film adaptation of “Les Miserables” contains the elements of an epic.

In fact, the great pleasure of “Les Miserables” is its tight focus as a character study. Even more unexpected is that the film’s emotional and thematic core is given over to the tribulations of a Jewish family in Nazi-occupied France.

After decades of denial, French filmmakers have only recently begun examining Vichy-era crimes. But although fine films such as “Uranus” and “Doctor Petiot” cast an unflinching eye on collaborators, and Louis Malle’s “Au Revoir Les Enfants” acknowledged that the Holocaust struck French Jews, no French movie before “Les Miserables” has taken such a compassionate attitude toward the plight of wartime Jews.

Writer-director Claude Lelouch (“A Man and a Woman”) has transposed Victor Hugo’s 1842 [sic] novel to the first half of this century. As his Jean Valjean, Lelouch invents Henri Fortin (Jean-Paul Belmondo in an extraordinary performance), a weathered but honest ex-boxer whose childhood was the stuff of nightmares.

In the film’s riveting opening, Henri’s father (also played by Belmondo) is convicted of a murder he didn’t commit. The wintry prison scenes, set amidst falling snow, possess a fierce beauty that doesn’t mask the grim conditions.

The young Henri and his mother, meanwhile, work and live in a dingy seaside inn. Since legal appeals are expensive, Henri’s mother is cajoled into prostitution by the greedy innkeeper.

Henri’s parents’ separate attempts to escape their dire predicaments leave the boy orphaned at a vulnerable age.

Fast forward to the end of World War I, as Henri begins a successful boxing career. A moment later, two decades have passed and Fortin is out of the ring and the owner of a moving truck.

When he crosses paths with the Zimans, however, his life gradually becomes charged with purpose. And it is here that Lelouch’s “Les Miserables” begins to take on a mesmerizing momentum.

Mr. Ziman is a successful Jewish lawyer, and his ballerina wife converted when they were married. But with Vichy France gripped by Nazis and their accomplices, the Zimans and their precocious daughter must flee.

The illiterate Fortin not only carries their possessions, but transports the Zimans in his truck to avoid risky trains. They, in turn, repay his kindness by relating Hugo’s story of “Les Miserables.”

On one level, the Zimans are the catalyst for Fortin’s wakening to the pleasures of literature and literacy. More importantly, they ignite his innate moral instincts.

Fortin drops the daughter at a convent, posing as her father. And he delivers the Zamins to the contact who will supposedly guide them across the Swiss border.

But the Zimans become separated, and face harrowing individual obstacles to survival. Fortin drifts to the background as Lelouch concentrates on the Zamins’ stories, particularly Mr. Ziman’s arduous months sheltered by a bickering couple in the cellar of their farm.

“The Zimans are characters who do not belong to Victor Hugo,” Lelouch wrote in the press notes, “but who symbolize for me the misery of the twentieth century.”

Fortin eventually returns to the foreground, of course, but his fate in “Les Miserables” is forever intertwined with the Zimans. By extension, Lelouch implies that the destinies of France and her Jews is equally inseparable, a noble sentiment that one endorses with a whisper of caution.

“Les Miserables” is a gripping yarn in the old-fashioned tradition, rich with detail and nuance. For Jewish audiences, the film frequently transcends entertainment to achieve robust poignancy.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

It's finally finished! 10 weeks of work has culminated in an entire 1840s mens ensemble. I even managed to squeeze a few accessories in at the very end. If anything, I'm just even more impressed with the costume design and construction for The Muppets Christmas Carol. They didn't have to include all of the extra layers and accuracy, but they did!

The final tally for the Victorian Gonzo ensemble is 11 major pieces: shirt, trousers, braces, waistcoat, stockings, shoes, cravat, tailcoat, overcoat, gloves, and hat. Though I have often heard exclamations over how many layers women wore in the 19th century along with the myth of how difficult that must of been, we can't ignore that men wore a similar number! This is a winter ensemble with the overcoat, but that's the only additional garment for the weather- otherwise changes would have been made to the textiles and construction techniques to deal with heat.

While this project was aimed at 1842, the year that Charles Dickens was working on A Christmas Carol, the basic construction of the many pieces holds fast for quite a few years either direction. Sewing machines begin to take over in the coming years, but it's a long time before the techniques change to fully accommodate the new technology.

There are videos of the entire process, including research. So if you're interested in men's fashion during Dickens' day or just dressing as Victorian Gonzo, here ya go.

34 notes

·

View notes