#The Great War of Archimedes

Text

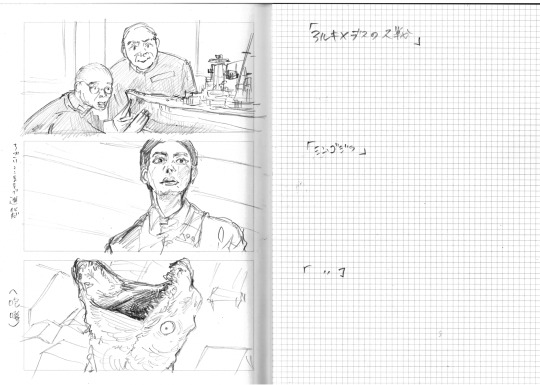

Tasuku Emoto in The Great War of Archimedes (2019)

#The Great War of Archimedes#柄本佑#tasuku emoto#アルキメデスの大戦#mine#also tag#masaki suda#菅田将暉#here am i queue me

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

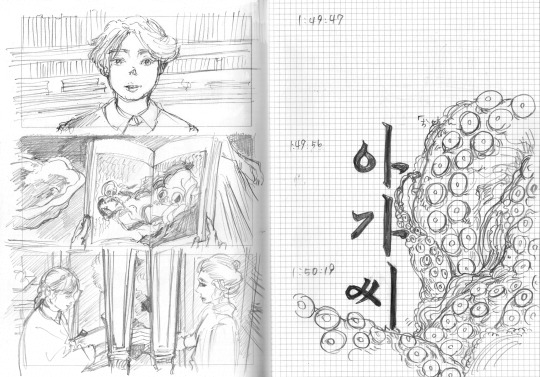

The Great War of Archimedes

Shin Godzilla

The Handmaiden

The Grand Budapest Hotel

The Legend of 1900

#The Great War of Archimedes#Shin Godzilla#The Handmaiden#The Grand Budapest Hotel#film#The Legend of 1900

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE GREAT WAR OF ARCHIMEDES (2019)

0 notes

Text

A classic Greek vs Roman situation

#agathocles#greeks vs romans#roman history#greek history#syracuse#sicily#archimedes#greek tyrants#greek tumblr#roman tumblr#italian tumblr#sicilian#king of Sicily#sextus can sext us#sextus pompey#Sextus Pompeius#pompey the great#punic wars#carthage#greece#magna graecia#greater greece#pyrrhus#pyrrhus of epirus#pyrrhic victory#pyrrhic#Pompeius magnus#gnaeus pompey#pompeius#gnaeus pompeius magnus

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

“I really just need to make an entire breakdown on Medic one of these days 😭” Well, do it. Umm, you coward —I'm so sorry for calling you a coward, Jamison :'(—.

Medic's Past Headcanons (Also Some Archimedes Content!)

————————————————————

No apology needed my friend, I am but a coward 😭

I lied a little bit, I changed my mind on doing a full breakdown, just changed it to some headcanons about his past and meeting Archimedes </3

But no, I've mainly not posted this because I've had other requests and also this one will probably get heavy. I wasn't sure if I wanted to post content with actual angst and upsetting themes.

But I'm here now because looking past all the jokes and my own personal love for doctors. I should also mention, written by an American and a person with know knowledge of the German education system, and medical practices in general!

ALSO, finally writing Medic with his accent and some actual German, please forgive me if you are a native speaker for using a mix of google translate and my very poor German skills 💖

————————————————————

ALSO ALSO mutual appreciation comment! Another thank you for letting me talk about Medic <3

————————————————————

TW: CHILD NEGELECT, SU!C1D@L IDIATIONS, FLUFF AT THE END!

————————————————————

He's been asked about his mother before, his answer has always been,

"Meine mutter? She vas good woman, she... she did her best." Said with a softer tone than anyone has ever heard him speak in.

He's lying. She severely neglected him as child. After his mother fell pregnant, his father left. His mother resented Medic for this, blaming him for his father leaving, refusing to realize how volatile their relationship had been before he was conceived. When Medic was born his mother refused to bond with him, holding him only when others gave her expecting looks. For the first years of his life his mother only tended to his basic needs to keep him from crying, his crying always annoyed her. It never got better with time, she never learned to love him like people had claimed when she started expressing her contempt for him. She would sometimes give him small bits of attention, then she would get a wicked smile on her face as he cried when she stopped paying attention to him for seemingly no reason. Always making him feel like he was responsible for the sudden lack of attention.

————————————————————

His younger years in school is also something he will lie about if asked. (I'm ignoring college because uh, I have no idea what to write for that 😭)

"I vas great, top of my classes, Natürlich. Ich war sehr beliebt."

(Of course. I was very popular)

When he was younger, he was top of his classes. He always excelled at whatever class he was put in, his favorites being science, he obviously loved medical textbooks, along with zoology textbooks, always had one of the other, he'd spend lunches just reading from his books, or hiding in the library, trying to learn everything he could about both. In a way you could say he was popular, but not in the good way. He always had his books on hand, always had the best grades, was always the teachers favorite student, and the other kids hated that. He took his fair share of beatings while he was in school.

————————————————————Medic had never thought about dying, sure he watched patients die, and he knew deep down his mother had died at some point, (He never heard from her after he left his home town, despite his attempts to contact her) but he never thought about the concept of him dying. It hit him like a ton of bricks when he had his first panic attack, and it clicked in his head that he just didn't want to be alive. He couldn't tell you why the switch flipped in his head that made him reach that low, but it did, and it was awful. He almost went insane, he couldn't breathe, he couldn't do anything besides sit in his room and feel years of emotions just hit him out of nowhere. He thought he would die, he wanted to die, dying would be preferable to whatever this was. In the midst of his panic attack, something hit his window with a loud thump. (Aren't I so clever for this transition? lmao 😭)

————————————————————

The day Medic and Archimedes met continues to be one of the best days of his life. A bird had hit his window, pulling him out of whatever spiral he was currently having. Medic just looked at the window for a minute, content to just assume the bird flew off after being dazed a bit. When he heard tiny coos and chirps outside. He pushed it open and saw a little dove huddled in a corner, cooing sadly, shaking as it tried to move its wing but chirping painfully when he moved his wing. Medic put his hand out and tried to scoop up the bird, and the bird ended up attacking his hand. Medic pulled his hand back, a tad shocked, but then tried again. The bird slowly eased up to him once he understood Medic wasn't going to hurt him. Medic took him inside and checked him out. His wing was broken, and it was nothing Medic couldn't fix. He fixed up the birds wing, then decided to get some things to keep the bird comfortable while he recovered. He ended up spoiling him without realizing it. He went to go buy a bird cage and ended up buying the nicest one, the best bird food, and even toys 😭 He came back and set it up all nice for the bird. They bonded pretty quickly after that. However, time passed, and Medic found himself growing attached to the little bird, even naming him, which he knew was a mistake the moment he did so. He knew it was a bad idea, and he did it anyway. After about a month of them living together, Archimedes wing was functional again, Medic enjoyed watching him fly from his cage to the door to great him when he came home from wherever he had gone. But after the third or fourth time, Archimedes greeted him at the door. He knew he was well enough to go back out into the world. That evening, before sunset, Medic opened his window and put Archimedes on the ledge, prompting him to fly off, totally not on the verge of tears, about to experience the worst pain of his life or anything. Archimedes just tilted his head, confused, turned around, and nestled up to Medics arm that he had been propping himself on. Audible sobbing could be heard from his house that night. Medic would later find a way to keep Archimedes to live forever with him, making sure that Archimedes was spoiled to death, and was told each day the value Medic put on their friendship.

"Wir werden für immer zusammen sein, mein Freund, das verspreche ich!"

"Coo"

(It'll be us forever my friend, I promise.)

(I'm counting on it)

————————————————————

Ough, im a sucker for a happy ending 😭or for some reason, I feel like this is super embarrassing, but I' going to ignore that feeling. Sorry for the angst dump, but it had to be done, and I'm sorry it's not very long! I hope you guys like this! Uh, a mini headcanons, then another Medic post, and then some new headcanons are in the works! There is so much Medic content, but I'm not complaining 💖

#tf2#team fortress 2#tf2 headcanons#team fortress headcanons#tf2 hcs#tf2 medic#medic tf2#tf2 archimedes

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

Heavymedic but medic is Frankenstein while heavy is Frankensteins monster but in a real way not costumes

HeavyMedic is the ultimate ship, and I am very much here for it. I don't know exactly what you wanted done so I went with some fluff.

~~~~~~~~

It was considerably dark in the medical wing at the tuefort base. The lights went out due to Scout stealing the company truck and ramming it into a powerline not too far from the base. The only sounds in this part of the base wee the sounds of heavy footsteps on the tile floor and soft voices talking softly to each other.

"Alright my precious creation, now lift me higher."

What Medic was doing could be seen as dangerous; but with his taller than 6'5" boyfriend he had nothing to worry about. Medic had this great idea to build a monster a few months back. But after dealing with loneliness for years on end with this stupid Gravel War he decided to build a boyfriend instead.

Giant hands lifted Medic by the hips and hoisted him up by the large windows overlooking the examination room.

"Danke, mien Liebe."

Reaching out to the support beams Medic reached out to Archimedes. From Heavy's perspective the doctor looked like an angel. The way his sharp features and light blue eyes looked in the dark room made him seem like an aethereal being. His hips felt so small and delicate under his fingers. If he focused hard enough he could feel the thrum of life circulating around in the lithe body.

The certain way that Medic's face flushed while straining to reach over to his beloved pet further cemented the deep love and adoration that he felt for him. Truly, the good doctor at this moment looked like a god. Finally, upon reaching Archimedes he turned his gaze towards Heavy.

"Liebe? what are you starring at?"

Feeling a blush rising to his cheeks he slowly lowered the man till they were face to face.

'How utterly small he is. So perfect fitting in my hands.'

Slowly as if not to startle him he pressed his lips to Medic's forehead. Planting a chaste kiss, later on more would surely follow.

"I was staring at you Doktor, you look so cute in my hands."

#tf2 mercs#tf2 fic#tf2 heavy#tf2 medic#heavymedic#red oktoberfest#fluff#tf2 fanfic#team fortress two fanfic#team fortress 2 fanfic#aww#how sweet#frankenstein#monster#tf2 monster au#monster heavy#Frankenstein medic#size difference#they love each other#so sweet#pet doves#Archimedes#request#tf2 requests#thank you anon#anon requests

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

The enigmatic life of the ancient Greek thinker, Archimedes, went from discovering principles to inventive creations that served as strategic defensive war machines. Regarding his demise, two versions of his death propose conflicting narratives. Cicero in his pursuit of Archimedes' tomb, uncovered inscriptions and hidden stories, in a unique expression of Roman admiration for the Greeks.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

(If we survive) Birthday promises, part 3.

• for @drarrymicrofic prompt: ♫The Great War (august'23) | words: 327 | cw: hints of eating disorder.

His ancestral home is haunted. Not by ghosts (Percibal Archimedes Malfoy The Third was exorcised twenty-two times before but he was gone for good the moment The Dark Lord placed one bare foot on the hardwood floor.

Draco couldn't eat the food on his plate and couldn't stomach what was happening in front of his eyes and the only thing he could hold down was lukewarm tea when the screams and the laughter were over, usually at 4 am, after the werewolves were tired enough to sleep or were gone for their last hunt. It was never over, "the house has an echo", his father said.

When his mother said her goodbyes on the platform after the holidays, Draco's first thought was "he isn't here". Greg passed him bread and Vince served him pumpkin juice, and he wouldn't touch anything besides tea but they were trying to feed him anyway. When he lifted his head, he could only notice the empty places all around him. Most muggleborns were gone. Was it his fault? He ran to the nearest sink, bile burning his throat.

"He isn't here", he whispered every night. And looking down from the tower, he wondered if he meant The Dark Lord or The Chosen One.

The air was soft and cold on his face. It reminded him of flying. It reminded him of flying against Harry Potter, Undesirable Number One, and his stomach ached with the need to play Quidditch again. He wouldn't mind losing this time.

Isn't that a funny thought for a marked man like him?

In the darkness of the tower where he saw their Headmaster die, Draco feels a pang of desire for the first time in a year. Hunger.

He closes his eyes and makes a short list:

1) Flying. Enjoying every second, finding ways to make it better.

2) Eating again. Enjoying a meal in his ancestral home.

3) Harry Potter's hand… if they survive the great war.

I wasn't planning on writing a third part, but I love that song and well, this happened. I didn't post it at the time because I was too busy to edit it but tonight I remembered this little thing, so... Here we are. You can read here the previous Birthday Promises part 1 and part 2.

#drarry#drarry microfic#drarry drabble#draco malfoy#harry james potter#vincent crabbe#greg goyle#malfoy family#thereaderarchive writes#birthday promises

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

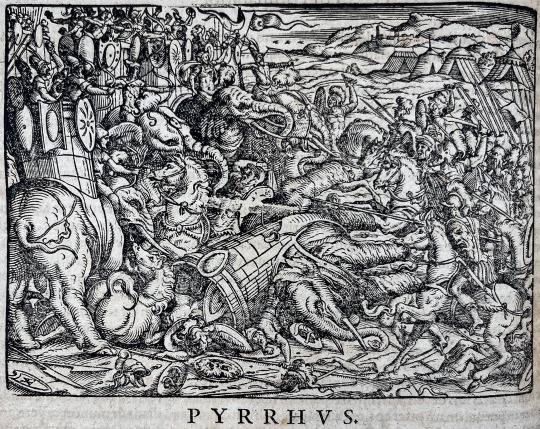

A Plutarchian Woodcut Wednesday

We’re spending our Woodcut Wednesday with this stunning sixteenth-century edition of Plutarch’s classic Parallel Lives featuring the work of artists Jost Amman and Tobias Stimmer.

The allegory of Fama, otherwise known as Fame or Renown, by Tobias Stimmer opens Plutarch’s Parallel Lives on the title page.

Various scenes from the life of the legendary Athenian monarch Theseus, including the hunt of the Calydonian boar and the hero throwing Sciron off a cliff edge. Plutarch pairs the Greek Theseus with the Roman Romulus.

The founding of the city of Rome under Romulus. The murder depicted in the foreground could be Romulus slaying Remus in the dispute over where Rome ought to be built.

Plutarch (ca. 46-after 120 A.D.) was born under Roman rule in Chaeronea, Boeotia, to a wealthy and established Greek family. Plutarch traveled to Athens in the mid-60s to study a variety of subjects, including medicine, physics, Latin, and philosophy. Though they were technically the conquering rulers, Romans at the time valued their Greek subjects’ culture of learning, and Plutarch was among those invited to tour Italy as a lecturer. Plutarch’s moral and philosophical lessons enjoyed success and formed the basis of his later written works. Parallel Lives was penned towards the end of Plutarch’s life when he had returned to Greece and was serving as a statesman and head priest of Apollo.

The unfortunate demise of the scholar Archimedes at the hands of Marcellus’ forces as they sack Syracuse. Plutarch relates that Marcellus’ greatest regret was the death of the famous mathematician.

Parallel Lives (Gk., Bioi paralleloi) is a moralistic set of biographies that examines the lives of notable Greek men and their Roman counterparts. The biographies are moralistic in the sense that Plutarch did not intend to write historically accurate accounts but rather wanted to draw out the lessons to be learned from the examples, both good and bad, of the lives of famous Greek and Roman individuals. Parallel Lives had a profound influence on readers from Plutarch’s contemporaries in the Roman Empire up through to the Middle Ages and early Renaissance. For example, William Shakespeare drew heavily on Plutarch’s Parallel Lives to write the plays Coriolanus, Timon of Athens, Antony and Cleopatra, and Julius Caesar.

Coriolanus and his forces, in the Volscian camp, hear the pleas of his mother, wife, and the women of Rome to stop his attack on the city. Coriolanus relents and the women are later honored with the building of a temple to the goddess Fortuna.

The edition of Parallel Lives featured in this post was printed by Frankfurt am Main publisher Sigmund Feyerabend (1528-1590) in 1580. The text is the Latin translation of Heidelberg University scholar Wilhelm Xylander (1532-1576), who famously produced the first Latin translation of Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations. The woodcut illustrations are the work of the prolific Swiss-German artist Jost Amman (1539-1591) and Swiss painter Tobias Stimmer (1539-1584). As an interesting sidenote, several of the woodcuts appearing in this edition of Plutarch were recycled from Feyerabend’s 1568 edition of Livy’s History of Rome.

Battle between two armies, one on horseback and the other on war elephants. This generic illustration is repeated for Plutarch’s Life of Alexander (the Great) and Life of Pyrrhus (of Epirus). The former famously fought against forces that used elephants; the latter notably used them in battle.

As a change of pace from all the foregoing imagery of bloodshed and gore, we'd like to end with this elaborate woodcut of Aristotle seated at a table of scholars. Aristotle is not among the lives covered in the Bioi paralleloi, but this edition adds a brief biography of the philosopher by Guarino Veronese.

Images from: Plutarch. Vitae illustrium vivorum Graecorum et Romanorum. Frankfurt am Main: Sigmund Feyerabend, 1580. Catalog record: https://bit.ly/3DUnWhl

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny: The Delicate Art of Franchise Exhumation

[The following review contains SPOILERS; YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!]

Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny is all about the inexorable march of time. When we rejoin our aged protagonist in the film’s “present day” setting of 1969 (following an excessively lengthy prologue that flashes back to 1944), we discover that he has essentially been discarded by life and abandoned by the American Dream. His son is dead—a casualty of the Vietnam War. His wife, inconsolable in her grief over the loss, has filed for divorce. And on top of everything else, he’s being forced to retire from his teaching position at Hunter College. His students are too distracted by news of the recent moon landing to pay attention to his lectures; why bother researching the past when the future is now?

One notable exception to this fatalistic philosophy is Jürgen Voller, a former Nazi scientist employed by the U.S. government courtesy of Operation Paperclip. Still bitter over Germany’s defeat at the hands of the Allies, the not-so-good doktor seeks to acquire Archimedes’ Antikythera, an ancient relic rumored to be capable of literally rewriting history. Mads Mikkelsen navigates the role with aplomb, finding a surprising degree of depth in what could easily have been a flat, two-dimensional villain. No matter how suave, sophisticated, and confident he pretends to be, Voller is ultimately a feeble mathematician, not a soldier; he relies on hired muscle to fight his battles for him—because his own infrequent attempts at gunplay and fisticuffs usually result in spectacular failure.

Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s performance as Indy’s estranged goddaughter Helena Shaw is equally superb. Despite the right-wing blogosphere’s insistence that the Fleabag creator’s “woketevist” politics would ruin the movie, her character is a far cry from the girl power feminist wish fulfillment strawman that they imagined. She is neither morally nor intellectually superior to our hero—on the contrary, she is a compulsive liar and a petty thief; her greed, ambition, and opportunism consistently cause more problems than they solve. Indeed, her arc revolves entirely around gradually shedding her ruthlessly pragmatic, self-serving attitude.

At the end of the day, however, this is Harrison Ford’s show, and his (allegedly) final outing as the iconic archeologist is appropriately poignant. While the actor acknowledges the unavoidable fact of his advanced “mileage,” he wisely refuses to make it the butt of a cruel, shallow joke. Indy is no longer physically fit enough to punch his way out of every conflict, and he is slower to recover from his numerous injuries, but he nevertheless remains as cunning, resourceful, and doggedly determined as ever. But Ford’s true strength lies in his vulnerability; after decades of adventuring—plundering tombs, pummeling tyrants, and witnessing terrible miracles—Dr. Jones has accumulated a great deal of trauma. Normally, he hides his burden well, carrying himself with quiet dignity. Occasionally, though, his façade cracks, allowing the audience to briefly glimpse his repressed guilt, remorse, and regret. These rare, fleeting moments of emotional authenticity are captivatingly beautiful.

Dial of Destiny isn’t perfect, but neither is it the soulless nostalgia bait that many fans were dreading. Regardless of its structural shortcomings, it features actual themes—even John Rhys-Davies’ obligatory cameo appearance serves a clear narrative purpose. And considering the current state of the industry—corporations reducing the art of cinema to digital “content” that exists only to sell subscriptions to streaming platforms—that's got to count for something, dammit!

#Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny#Indiana Jones#Dial of Destiny#LucasFilm#Harrison Ford#James Mangold#Mads Mikkelsen#Phoebe Waller-Bridge#George Lucas#film#writing#movie review

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you're like me you might have read or got read to the Bartimäus trilogy. And if you're even more like me you read it a bunch of times. (I don't remember much about the Ring of Salomon so I'll refrain from commenting on it myself, quotes may happen tho)

And if you're even more like me, you didn't notice how much in this book is jewish coded. Mainly the Czech and the Golems. I, later after finding out about the story of the golem, checked and found out that Stroud openly was heavily inspired by it after visiting Prague. (Also a main featured in the books) That on top of general racism/discrimination allegories, anti imperialist messaging and talking truth to power shit.

That doesn't mean that everything is good tho, or that certain things were handled well. I'll add the links for all quotes I put immediately after them.

"The Bartimaeus books are also, in their own way, as ideologically coded as the adventure stories of Howard and H. Rider Haggard I discussed in the previous post. In particular, they align with the anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist sentiments of the protest left between the 2003 Iraq invasion and Occupy Wall Street protests, their demons and magicians part of a magical class war."

"The representation of Jews in Stroud’s series is intertwined with the books’ politics. On the one hand, Jews are mentioned directly in The Golem’s Eye, the second book of the original trilogy. There we learn that, in its Victorian period, Stroud’s fantasy Britain, ruled by a dictatorial and magical Gladstone, defeated a rival magical empire based in Prague."

"Naturally, the Czech magicians (with a chief minister named Meyrink) used golems. The immense power and off-putting ugliness of these constructs are described wonderfully by Stroud. We learn that these golems were originally created by the Jews of Prague and “the great magician Loew.” In Loew’s time, “the Jewish community” of Prague “supplied the Emperor with most of his money and much of his magic. Forcibly restricted to the crowded alleys of the ghetto, and at once distrusted and relied upon by the rest of Prague society, the Jewish magicians grew powerful for a time.”"

"Such tropes cut across left and right. The 99%-versus-1% politics of Occupy Wall Street and much left-wing activism during the years in which the Bartimaeus books were published often incorporated anti-Jewish slander, a trend which persists."

https://investigationsandfantasies.com/2022/07/18/jews-and-politics-in-the-bartimaeus-series/

(author also talks about rowling + her influence over current age fantasy stories. So here's another link https://investigationsandfantasies.com/2022/07/05/the-occult-jew-pt-8/ I was generally interested in looking up more related to Rowlings and HPs impact on literature/fantasy after finding out that tv tropes lists muggles (as in non magical people being treated differently from non magical folks, often in a belittling or similar way) as a trope. This also exists in Bartimäus as non magicians are called commoners. But you might also know about fantasy that calls them mortals or such)

"But in fact the deepest conflict in the Bartimaeus books isn’t between magician and commoner but between magician and djinni. And I’d say that’s not so much a class system as a colonial one. The wizards exploit the resources and bodies of the djinn they can control. Those djinn are a different race of being from an Other Place, ancient and yet bound to serve their British masters.

It’s notable that Bartimaeus and his magical peers include no leprechauns, elves, ogres, or the other enchanting creatures from European fairy tales. He doesn’t tell many stories about Arthur, Archimedes, Daedalus, Roland, Siegfried, Heracles, or other European heroes of the distant past. Instead, Bartimaeus talks at length about Gilgamesh of Mesopotamia, Solomon of Israel, Ptolemy of Egypt. He speaks of tasks in Uruk (Sumer), Karnak (Egypt), and--when forced to--Jericho (Palestine). The amulet that provides the title for the first book comes from Uzbekistan."

"Despite his books’ picture of British governors exploiting Asian power, Stroud seems to steer away from addressing parallels to real history. In resurrecting the British Empire as a magical superpower, he emphasizes its power over continental Europe and North America only. The Golem’s Eye depicts a Czech immigrant underclass in London, but we never see the Asian, African, and Caribbean minorities of today’s Britain. The Amulet of Samarkand makes a brief mention of weavers in Basra toiling to create a magnificent carpet, but the books aren’t clear about whether their British Empire is contiguous with “all the pink bits” that used to appear on British school maps. Perhaps that past is too recent and too awkward."

http://ozandends.blogspot.com/2007/03/bartimaeus-and-british-empire.html?m=1

"In a modern-day alternate universe, London rules the British Empire and magicians rather than monarchs rule London. That’s been true ever since the great William Gladstone defeated the rival sorcerers of Prague. But the glory days are gone. War with the American colonies is draining patience and resources, the commoners are resentful and the government has become a bureaucracy of second-raters. Magicians procreate, at least professionally, by taking bright young schoolchildren into their homes to train in the magic arts. Arthur Underwood, a magician of middling status and competence, accepts a six-year-old boy named Nathaniel as apprentice. No one knows his last name, because his parents have disappeared after selling him into the service. And no one is ever to know his birth name because that knowledge would give his enemies power over him.

Enemies are a given; there’s no Hogwarts-style collegiality among the guild. Magicians are the most conniving, jealous, duplicitous group of people on earth, even including lawyers and academics. They worship power and the wielding thereof, and seek every chance they can to undercut their rivals. This is according to Bartimaeus, in a footnote.* He should know. Though a spirit of considerable power, he is continually at the beck and call of climbers and posers who can summon him from “the other place” merely by learning his name and the appropriate words. When he’s called to London by an unknown magician who turns out to be a mere kid, it’s only the beginning of five very challenging years."

Here, I felt this was important

"Nathaniel is only twelve when he first summons Bartimaeus (in the passage quoted at the head of this post); when the series ends, he is seventeen. In each volume, he and his djinni must defeat a cabal whose overweening ambition threatens the social order, but Nathaniel himself has ambition to spare. He’s interesting that way. Young fantasy heroes like Harry Potter and Percy Jackson almost always possess an essential decency��though tempted, one senses that they are not corruptible. Nathaniel (who takes the professional name of John Mandrake) is corruptible: not only proud but vengeful, and embittered by the humiliating treatment he receives from his master and other magicians."

"What does paganism have to do with this? There are at least two kinds of “magic.” One kind seeks to control inanimate forces, dramatized by Harry Potter with his wands and spells (and bearing some resemblance to modern science). The other seeks to control personal spirits, and is also known as shamanism or necromancy. That’s the system imagined in Bartimaeus: an unknowable Ultimate Spirit or First Cause has spun off lower manifestations of itself, which in turn generate lower and lower forms, all the way down to rock and clay and the pathetic beings that crawl on it (i.e., us). Though arranged in a hierarchy, spirits (known as “gods,” in other cultures) have no controlling ethic. And, outside of their own personal favorites, they despise humans."

"Dispatching the monster stops the destruction and clears the way for an alliance of magicians and commoners, but there’s no guarantee that the new order will be much improvement on the old. Maybe; maybe not. Nothing has changed but the circumstances."

https://redeemedreader.com/2011/03/among-the-pagans-bartimaeus/ (I don't know how valuable this analysis is ngl. Also I'm running out of time for today)

Adding this not because it features any analysis but just for flavor ngl (and to share some positivity. Any shortcomings the series might have don't make everything positive about it disappear. However little you think it is)

https://www.reddit.com/r/Bartimaeus/comments/nt8uo0/jewish_mythology_in_the_series/

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Great War of Archimedes (2019)

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

In the Hawk list : Clint Barton and Kate Bishop both become Hawkeye at some point, Hawk (Watership Down)

Hen : Billina (Wizard of Oz series)

Dodo : Dab (Ice Age)

Seagulls : Scuttle (Little Mermaid), Kehaar (Watership Down), Kengah (The Story of The Cat Who Taught seagulls To Fly 😭😭 (book) / Lucky and Zorba (movie))

Owls : Archimedes (The One and Future King), Owlowiscious (My Little Pony),

Eagles : Sitka (Brother Bear)

Ravens : Quoth (Discworld)

Non existent species : Mockingjays (Hunger Games), Porgs (Star Wars)

Ahhh this is great!

Anyone need some more birds to enter? This amazing anon has provided quite a great list!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve never really felt interest in watching The Great War of Archimedes - a movie about the creation of a battleship too expensive to ever use and obliterated like a chump - until I saw a meme using a clip from it, of an AA gun crew shooting down a plane and literally immediately a PBY Catalina rescues the pilot while they watch dumbfounded

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I came of age during a relatively mellow period of the Soviet rule, post-Stalin. Still, the ideology permeated all aspects of life, and survival required strict adherence to the party line and enthusiastic displays of ideologically proper behavior. Not joining a young communist organization (Komsomol) would be career suicide—nonmembers were barred from higher education. Openly practicing religion could lead to more grim consequences, up to imprisonment. So could reading the wrong book (Orwell, Solzhenitsyn, etc.). Even a poetry book that was not on the state-approved list could get one in trouble.

Mere compliance was not sufficient—the ideology committees were constantly on the lookout for individuals whose support of the regime was not sufficiently enthusiastic. It was not uncommon to get disciplined for being too quiet during mandatory political assemblies (politinformation or komsomolskoe sobranie) or for showing up late to mandatory mass-celebrations (such as the May or November demonstrations). Once I got a notice for promoting an imperialistic agenda by showing up in jeans for an informal school event. A friend’s dossier was permanently blemished—making him ineligible for Ph.D. programs—for not fully participating in a trip required of university students: an act of “voluntary” help to comrades in collective farms

(…)

Science was not spared from this strict ideological control. (6) Western influences were considered to be dangerous. Textbooks and scientific papers tirelessly emphasized the priority and pre-eminence of Russian and Soviet science. Entire disciplines were declared ideologically impure, reactionary, and hostile to the cause of working-class dominance and the World Revolution. Notable examples of “bourgeois pseudo-science” included genetics and cybernetics. Quantum mechanics and general relativity were also criticized for insufficient alignment with dialectic materialism.

(…)

Fast forward to 2021—another century. The Cold War is a distant memory and the country shown on my birth certificate and school and university diplomas, the USSR, is no longer on the map. But I find myself experiencing its legacy some thousands of miles to the west, as if I am living in an Orwellian twilight zone. I witness ever-increasing attempts to subject science and education to ideological control and censorship. Just as in Soviet times, the censorship is being justified by the greater good. Whereas in 1950, the greater good was advancing the World Revolution (in the USSR; in the USA the greater good meant fighting Communism), in 2021 the greater good is “Social Justice” (the capitalization is important: “Social Justice” is a specific ideology, with goals that have little in common with what lower-case “social justice” means in plain English). (10−12) As in the USSR, the censorship is enthusiastically imposed also from the bottom, by members of the scientific community, whose motives vary from naive idealism to cynical power-grabbing.

Just as during the time of the Great Terror, (5,13) dangerous conspiracies and plots against the World Revolution were seen everywhere, from illustrations in children’s books to hairstyles and fashions; today we are told that racism, patriarchy, misogyny, and other reprehensible ideas are encoded in scientific terms, names of equations, and in plain English words. We are told that in order to build a better world and to address societal inequalities, we need to purge our literature of the names of people whose personal records are not up to the high standards of the self-anointed bearers of the new truth, the Elect. (11) We are told that we need to rewrite our syllabi and change the way we teach and speak. (14,15)

As an example of political censorship and cancel culture, consider a recent viewpoint (16) discussing the centuries-old tradition of attaching names to scientific concepts and discoveries (Archimede’s Principle, Newton’s Laws of Motion, Schrödinger equation, Curie Law, etc.). The authors call for vigilance in naming discoveries and assert that “basing the name with inclusive priorities may provide a path to a richer, deeper, and more robust understanding of the science and its advancement.” Really? On what empirical grounds is this based? History teaches us the opposite: the outcomes of the merit-based science of liberal, pluralistic societies are vastly superior to those of the ideologically controlled science of the USSR and other totalitarian regimes. (17) The authors call for removing the names of people who “crossed the line” of moral or ethical standards. Examples (16) include Fritz Haber, Peter Debye, and William Shockley, but the list could have been easily extended to include Stark (defended expulsion of Jews from German institutions), (18) Heisenberg (led Germany’s nuclear weapons program), (19) and Schrödinger (had romantic relationships with under-age girls). (19) Indeed, learned societies are now devoting considerable effort to such renaming campaigns—among the most-recent cancellations is the renaming of the Fisher Prize by the Evolution Society, despite well-argued opposition by 10 past presidents and vice-presidents of the society. (20)

(…)

Some famous scientists were brave dissidents, and some were conformists and opportunists. Should we judge their scientific contributions by their political standing, the extent to which they collaborated with repressive regimes, or by how wholesome their personal lives were? The authors of the viewpoint (16) go as far as to suggest that we should use names of scientific discoveries and institutions as a vehicle to promote ideology—that is, as a propaganda tool—as was done by the Soviet, Nazi, and Maoist regimes.

The intersection of science, morality, and ideology has been studied by many scholars and historians. History provides ample evidence that totalitarian censorship of science is harmful to the progress and well-being of societies. Merton’s norms of science prescribe a clear separation between science and morality. (24) Particularly relevant is Merton’s principle of universality, which states that claims to truth are evaluated in terms of universal or impersonal criteria, and not on the basis of race, class, gender, religion, or nationality. (24) Simply put, we should evaluate, reward, and acknowledge scientific contributions strictly on the basis of their intellectual merit and not on the basis of personal traits of the scientists or a current political agenda.

Conversations about the history of science and the complexity of its social and ethical aspects can enrich our lives and should be a welcome addition to science curricula. The history of science can teach us to appreciate the complexity of the world and humanity. It can also help us to navigate urgent contemporary issues. (25) Censorship and cancellation will not make us smarter, will not lead to better science, and will not help the next generation of scientists to make better choices.

(…)

Today’s censorship does not stop at purging the scientific vocabulary of the names of scientists who “crossed the line” or fail the ideological litmus tests of the Elect. (11) In some schools, (33,34) physics classes no longer teach “Newton’s Laws”, but “the three fundamental laws of physics”. Why was Newton canceled? Because he was white, and the new ideology (10,12,15) calls for “decentering whiteness” and “decolonizing” the curriculum. A comment in Nature (35) calls for replacing the accepted technical term “quantum supremacy” by “quantum advantage”. The authors regard the English word “supremacy” as “violent” and equate its usage with promoting racism and colonialism. They also warn us about “damage” inflicted by using such terms as “conquest”. I assume “divide-and-conquer” will have to go too. Remarkably, this Soviet-style ghost-chasing gains traction. In partnership with their Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion taskforce, the Information and Technology Services Department of the University of Michigan set out to purge the language within the university and without (by imposing restrictions on university vendors) from such hurtful and racist terms as “picnic”, “brown bag lunch”, “black-and-white thinking”, “master password”, “dummy variable”, “disabled system”, “grandfathered account”, “strawman argument”, and “long time no see”. (36) “The list is not exhaustive and will continue to grow”, warns the memo. Indeed, new words are canceled every day—I just learned that the word “normal” will no longer be used on Dove soap packaging because “it makes most people feel excluded” (…)

Do words have life and power of their own? Can they really cause injury? Do they carry hidden messages? The ideology claims so and encourages us all to be on the constant lookout for offenses. If you are not sure when you should be offended—check out the list of microagressions—a quick google search can deliver plenty of official documents from serious institutions that, with a few exceptions, sound like a sketch for the next Borat movie. (38) If nothing fits the bill, you can always find malice in the sounds of a foreign language. At the University of Southern California, a professor was recently suspended because students claimed to have been offended by the sounds of Chinese words used to illustrate the concept of filler words in a communications class. (39,40)

(…)

The answer is simple: our future is at stake. As a community, we face an important choice. We can succumb to extreme left ideology and spend the rest of our lives ghost-chasing and witch-hunting, rewriting history, politicizing science, redefining elements of language, and turning STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education into a farce. (41−44) Or we can uphold a key principle of democratic society—the free and uncensored exchange of ideas—and continue our core mission, the pursuit of truth, focusing attention on solving real, important problems of humankind.

The lessons of history are numerous and unambiguous. (17) Despite vast natural and human resources, the USSR lost the Cold War, crumbled, and collapsed. Interestingly, even the leaders of the most repressive regimes were able to understand, to some extent, the weakness of totalitarian science. For example, in the midst of the Great Terror, (5,13) Kapitsa and Ioffe were able to convince Stalin about the importance of physics to military and technological advantage, to the extent that he reversed some arrests; for example, Fock and Landau were set free (however, an estimated ∼10% of physicists perished during this time (17)). In the late forties, after nuclear physicists explained that without relativity theory there will be no nuclear bomb, Stalin rolled back the planned campaign against physics and instructed Beria to give physicists some space; this led to significant advances and accomplishments by Soviet scientists in several domains. However, neither Stalin nor the subsequent Soviet leaders were able to let go of the controls completely. Government control over science turned out to be a grand failure, and the attempts to patch the widening gap between the West and the East by espionage did not help. (17) Today Russia is hopelessly behind the West, in both technology and quality of life. The book Totalitarian Science and Technology provides many more examples of such failed experiments. (17)

Today, STEM holds the key to solving problems far more important than the nuclear arms race: reversing climate change, fighting global hunger and poverty, controlling pandemics, and harnessing the power of new technologies (quantum computing, bioengineering, and renewable energy) for the benefit of humanity.

Normalizing ideological intrusion into science and abandoning Mertonian principles (24) will cost us dearly. We cannot afford it.”

“The insinuation of political agendas into science is nothing new; I wrote about it in my 1993 book “Kindly Inquisitors: The New Attacks on Free Thought.” Back then, factions like creationists, Afrocentrists, and Marxists were hawking alternatives to mainstream biology, math, and social science. Today, the political right is hard at work scrubbing school libraries and curricula of what they deem to be critical race theory (whatever that is) and LGBT “grooming” (whatever that is).

Meanwhile, on the left, scholars are calling for rethinking academic freedom so that it does not protect “some ideas [that] don’t deserve a hearing.” Just recently, the California state community college system directed its employees, including faculty, to contribute “to DEI and anti-racism research and scholarship,” in violation of academic freedom and possibly the Constitution (as FIRE points out). Anna Krylov, in her important article “The Peril of Politicizing Science,” gives other examples of social-justice activism masquerading as science. “I witness ever-increasing attempts to subject science and education to ideological control and censorship,” she writes, adding that she recalls similar efforts in the Soviet Union of her childhood.

(…)

In Quillette, the social psychologist Bo Winegard does a masterly job dissecting them. He takes note of the guidance’s terminal vagueness. “Ambiguity is piled upon ambiguity to expand the capricious purview of the censor,” he writes. “It does not require clairvoyance to predict that these criteria will not be consistently applied.” He notes the tendentious ideological assumptions embedded in the document. He identifies some of the legitimate research that could be squelched and chilled.

(…)

A dilemma, here, is fundamental. How can science consider social responsibility without politicizing research? This problem is hard. Over the centuries, science has worked out an imperfect but very functional answer: subsidiarity.

Subsidiarity is the notion of reducing centralized control over decision-making by pushing it down to lower levels, such as individuals, local governments, non-commissioned officers, franchise managers, and community groups. Subsidiarity taps local knowledge; it encourages experimentation and retards bureaucratic ossification; it encourages personal initiative; it deters systemic takeover by special interests.

To a great extent, science works on the same principle. Accrediting bodies, scientific societies, and professional organizations set general guidelines. Yet, in implementing those guidelines, they give broad discretion to universities, which give broad discretion to their faculties, which give broad discretion to individual researchers. For the most part, we trust trained professionals to make socially responsible research decisions. For the most part, they do. Questions about social harm and social justice are hashed out in conversations and debates among members of the research community, not settled peremptorily by a handful of editors.

In this disaggregated, decentralized system, journals play the essential role of middlemen. They assess research’s importance, vet its quality, and, on approval, usher it into the marketplace of ideas. Of course, they can’t be perfectly apolitical, because they’re human; but, traditionally, they aspire to be ideologically neutral so that the political inclinations of editors don’t supersede the scientific expertise of researchers. We want them to act as quality controls, not political checkpoints.

By explicitly making social justice an element of editorial policy, NHB breaks with this tradition. To the extent it does so, the results will be bad. However professional and well intentioned NHB’s editors may be, they are not qualified to decide on society’s behalf whether research is socially harmful or desirable. In fact, they have no idea how a piece of research will ramify.

(…)

Good luck, NHB, with your good intentions. We have 300 years of scientific tradition that helps researchers and editors understand what constitutes scientific merit. We know that Bayesian reasoning is more reliable than cherry-picking; that double-blind controlled trials are better than convenience samples; that equating correlation with causality is an error; and much, much more.

“Preventing harm,” by contrast, is a completely and inherently subjective criterion. The new policy invites activists and interest groups to veto “harmful” research. They will accept the invitation, claiming that whatever research offends them is oppressive, unequal, stigmatizing, traumatic, racist, colonialist, homophobic, transphobic, violent, and — you get the idea.

(…)

Moreover, NHB’s guidance patently is political. Consider this criterion for problematic content: “Submissions that embody singular, privileged perspectives, which are exclusionary of a diversity of voices in relation to socially constructed or socially relevant human groupings, and which purport such perspectives to be generalizable and/or assumed.” If you can figure out what this gobbledygook means, you are smarter than I am. What it does unambiguously convey, however, is woke-left identity politics. The editors might as well post a sign that says, “Conservatives Not Welcome.”

According to the Pew Research Center, from 2015 to 2019 the share of Americans saying colleges and universities have a “negative effect” on the country rose from 28% to 38%: a startlingly (and depressingly) dramatic increase. A lot of that hostility is attributable to the perception that the academy is left-dominated and intolerant. Even if scholars and editors do not deliberately inject politics into their work (and most don’t), multiple surveys show that conservative viewpoints are so rare in some disciplines that progressive orthodoxies are simply taken for granted.

Everything about the NHB statement will make this problem worse.

(…)

Understand that it is not your job to stop science from “perpetuating structural inequalities and discrimination in society.” Go back to doing what you know how to do. Understand yourselves not as riding astride the stream of research, judging what does and does not advance justice or harm society, but as humbly serving a community of scholars who collectively have infinitely more knowledge, wisdom, and experience than you do.

Allow your thousands of researchers, reviewers, and readers to make their own various and diverse determinations of how research might ultimately benefit or harm groups, individuals, and the public good. Accept that it is arrogant and self-important for anyone, including yourselves, to set themselves up as visionaries capable of prejudging the scientific process. Apply the non-political standards of scientific merit and editorial excellence which have been honed over centuries.

Above all, remember that by far the greatest engine of social justice, human rights, and equality has been the advancement of knowledge, and the rolling back of ignorance, by a community of truth-seekers empowered to follow evidence wherever it leads. If you care about making society better and fairer, you will serve that community, not appoint yourselves to direct it.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Western History

Ancient Greece was divided into city-states. Two notable city-states were Athens and Sparta. Athens was a society of intellectuals and philosophers while Sparta was a warrior culture.

Notable Greeks of ancient times include the military leader Themistocles, the mathematician Euclid, the scientist Archimedes, the legendary storyteller Aesop, the philosophers Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, and King Leonidas, who commanded his army of three hundred Spartans to fight ten thousand of King Xerxes' Persian warriors.

The religion of ancient Greece was polytheistic.

Several key deities were named Zeus, Hera, Hades, Poseidon, Dionysus, Ares, Athena, Hestia, Hephaestus, Apollo, and Hermes. Zeus was king of the gods and lord of the sky. Hera was Zeus' wife. Hades was the lord of the underworld.

Poseidon was the god of the sea. Dionysus was the god of wine and ritual madness. Ares was the god of war. Athena was the goddess of wisdom. Hestia was the goddess of the hearth. Hephaestus was the god of fire. Apollo was the god of light.

Hermes was the messenger deity. The Roman counterparts of the aforementioned deities are Jupiter, Juno, Pluto, Neptune, Bacchus, Mars, Minerva, Vesta, Vulcan, Apollo, and Mercury, respectively.

Hannibal, a military leader from Carthage (in Northern Africa) led his army, who were mounted on war elephants, across the strait of Gibraltar to the Iberian peninsula and then to Italy, where he attacked the Romans. This marked the beginning of the Punic Wars. During the Third Punic War, the Romans enslaved fifty-five thousand Carthaginians.

Rome was first a kingdom, then a republic, and then an empire. Romulus was the first king of Rome. During the Roman Republic, society was classified as the patricians and the plebeians (the commoners and the elites).

Julius Caesar is known as the destroyer of the Roman Republic. He was assassinated on March 15, 44 BC (the Ides of March) by Marcus Junius Brutus the Younger, who was accompanied by a mob.

Caesar Augustus, also known as Octavian, was Julius Caesar's grand nephew.

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, also known as Caligula, was an emperor of Rome and a member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. He was a decent ruler during the first six months of his reign, but after a near death experience, he started forcing his people to commit suicide. Caligula believed he was a living god.

Nero, also known as Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, killed his mother, Agrippina the Younger. He also killed his pregnant wife by kicking her to death. Nero also burned Rome to the ground and blamed it on the Christians, who were a new religious cult at the time. When the Praetorian Guard was after him, Nero committed suicide by slitting his throat.

Galileo Galilei was an Italian astronomer and mathematician. He refined the invention of the telescope. He was put under house arrest by the Catholic Church for teaching the heliocentric theory (which asserts that the sun is at the center of our solar system). The church believed in the geocentric theory which postulated that the earth was at the center of the solar system. Galileo is considered to be the father of modern science. He died in the early 1640s.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in 1914 by Gavrilo Princip who was a member of the Serbian terrorist organization the Black Hand.

At the onset of World War I, Germany backed Austria and Russia backed Serbia.

Adolf Hitler, born April 20, 1889, was a decorated veteran of the First World War. Kaiser Wilhelm II was the leader of Germany during WWI.

After WWI, in 1919 (the war ended in 1918), the Versailles peace conference took place. US President Woodrow Wilson, Lloyd George of Great Britain, Clemenceau of France, and Orlando of Italy were in attendance. The decisions made at this conference humiliated the Germans and may have led to the subsequent rise of Nazism.

Germany was ordered to pay billions of dollars in reparations and their military was limited to one hundred thousand. Also, part of their land (the Rhineland) was given away.

The axis powers of World War II were Italy, Germany, and Japan (Rome, Berlin, and Tokyo). They were the enemies of the allies, which included England, France, the United States, and many other countries. Benito Mussolini was the leader of Italy, Adolf Hitler was the leader of Germany, and Emperor Hirohito was the leader of Japan, whose prime minister was Hideki Tojo. Joseph Stalin, also known as Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili, was the leader of Russia.

Germany's most significant WWII atrocity was the Holocaust, which claimed the lives of twelve million people, including five or six million Jews. Other groups targeted include homosexuals, Polish people, and the physically and mentally disabled.

During the Second World War, the Japanese buried Chinese soldiers alive, cannibalized, and performed vivisection (dissection without anesthetics or analgesics).

Benito Mussolini was hung upside down on a meat hook and a mob tore him to pieces. He was known as an evil Robin Hood. He took from the rich and gave to the poor.

Adolf Hitler committed suicide in fuhrerbunker on April 30, 1945. His wife, Eva Braun, committed suicide with him.

The allied victory in Europe is celebrated on V-E day and the allied victory in Japan is celebrated on V-J day. General Douglas MacArthur was the supreme commander of the allied forces in the pacific while General Dwight D. Eisenhower was the supreme commander of the allied forces in Europe.

The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki killed around two hundred thousand people and resulted in deformities and diseases such as leukemia. The bomb dropped on Hiroshima, a uranium fission bomb, was called Little Boy and the bomb dropped on Nagasaki, a plutonium fission bomb was called Fat Man.

0 notes