#also this piece in dune which I am now a writer & editor for!

Text

meriem evangeline, mercy for the martyred body

#also this piece in dune which I am now a writer & editor for!#this piece is after a message left on queering the map in palestine xx#palestine#poets for palestine#resistance#poetry#poem#writings#excerpts#words#quotes#writers of tumblr#poets of tumblr

480 notes

·

View notes

Text

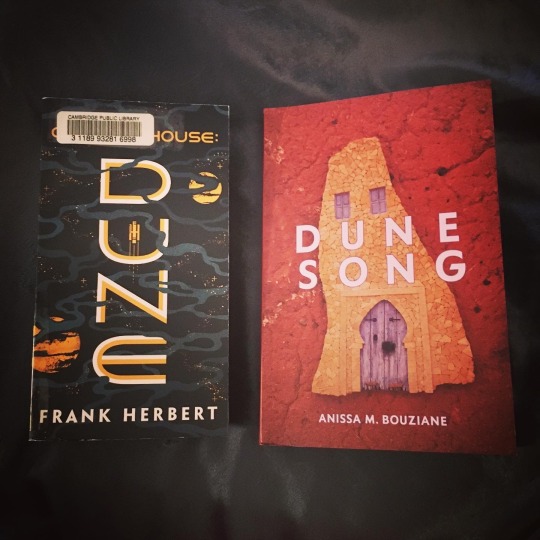

Wellesley Writes It: Interview with Anissa M. Bouziane ’87 (@AnissaBouziane), author of DUNE SONG

Anissa M. Bouziane ’87 was born in Tennessee, the daughter of a Moroccan father and a French mother. She grew up in Morocco, but returned to the United States to attend Wellesley College, and went on to earn an MFA in fiction writing from Columbia University and a Certificate in Film from NYU. Currently, Anissa works and teaches in Paris, as she works to finish a PhD in Creative Writing at The University of Warwick in the UK. Dune Song is her debut novel. Follow her on Twitter: @AnissaBouziane.

Wellesley Underground’s Wellesley Writes it Series Editor, E.B. Bartels ’10 (who also got her MFA in writing from Columbia, albeit in creative nonfiction), had the chance to chat with Anissa via email about Dune Song, doing research, publishing in translation, forming a writing community, and catching up on reading while in quarantine. E.B. is especially grateful to Anissa for willing to be part of the Wellesley Writes It series while we are in the middle of a global pandemic.

And if you like the interview and want to hear more from Anissa, you can attend her virtual talk at The American Library tomorrow (Tuesday, May 26, 2020) at 17h00 (Central European Time). RSVP here.

EB: First, thank you for being part of this series! I loved getting to read Dune Song, especially right now with everything going on. I loved getting to escape into Jeehan’s worlds, though sort of depressing to think of post-9/11-NYC as a “simpler time” to escape to. My first question is: Reading your biography, I know that you, much like Jeehan, have moved back and forth between the United States and Morocco––born in the U.S.A., grew up in Morocco, and then back to the U.S.A. for college. You’ve also mentioned elsewhere that this book was rooted in your own experience of witnessing the collapse of the Twin Towers on 9/11. How much of your own life story inspired Dune Song?

AMB: Indeed, Dune Song is rooted in my own experience of witnessing the collapse of the Twin Towers on 9/11. As a New Yorker, who experienced the tragedy of that now infamous Tuesday in September almost 19 years ago, I would not have chosen the collapse of the World Trade Center as the inciting incident of my novel had I not lived through those events myself. So yes, much of what Jeehan, Dune Song’s protagonist, goes through in NYC is rooted in my own life experience. Nonetheless the book is not an autobiography — I would consider it more of an auto-fiction, that is a fiction with deep roots in the author’s experience. The New York passages speak of the difficulties of coming to terms with the tragedy that was 9/11 — out of principle, I would not have chosen 9/11 as the inciting incident of my novel if I did not have first hand experience of the trauma which I recount.

EB: Thanks for saying that. I feel like there is a whole genre of 9/11 novels out there now and a lot of them make me uncomfortable because it feels like they are exploiting a tragedy. Dune Song did not feel that way to me. It felt genuine, like it was written by someone who had lived through it.

AMB: As for the desert passage that take place in Morocco, though I am extremely familiar with the Moroccan desert — and have traveled extensively from the dunes of Merzouga to the oasis of Zagora — this portion of the novel is totally fictional. That being said, I am one of those writers who rides the line between fiction and reality very closely, so if you ask me if I ever let myself be buried up to my neck in a dune, the answer would be: yes.

EB: How did the rest of the story come about? When and how did you decide to contrast the stories of the aftermath of 9/11 with human trafficking in the Moroccan desert?

AMB: Less than six months after 9/11, in March of 2002 I was invited back to Morocco by the Al Akhawayn University, an international university in the Atlas Mountains near the city of Fez. There I gave a talk which would ultimately provide me with the core of Dune Song: the chapter that takes place in the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, where following a mass in commemoration of the victims of the 9/11 attacks, an Imam from a Mosque in Queens was asked to recite a few verses from the Holy Quran. The Moroccan artists and academics present that day were deeply moved by my talk (which in fact simply recounted my lived experience); they told me that I should turn my talk into a novel. I thought the idea interesting and began to write, but within a year the Iraq War was launched and suddenly a story promoting dialogue and mutual understanding between the Islamic World and the West seemed to interest few, so I moved on to other things. Nonetheless, the core of Dune Song stayed with me.

Years later, as I re-examined that early draft, I realized that if I was to turn it into a novel, it had to transcend my life experience — and that is when I turned to my knowledge of the Moroccan desert and my longstanding interest in illegal trafficking across the Sahara desert. I returned to Morocco from the USA in 2003 thanks to Wellesley’s Mary Elvira Stevens Alumnae Traveling Fellowship to research what will soon be my second novel, but truth be told I got the grant on my second try. My first try in the mid-90s had been a proposal to explore the phenomenon of South-North migration across the Sahara and the Mediterranean. I remained an active observer of issues around Trans-Saharan migration, but I went to the desert three or four times on my return to Morocco before I understood that this was where Jeehan too must travel. My decision to bring Jeehan there probably emanated out of the serenity that I experienced when in the desert, but if Dune Song was to be more than just a cathartic work, I realized it should also attempt to draw a cartography of a better tomorrow — and so Jeehan would have to go to battle for others whose fate was in jeopardy because of a continued injustice overlooked by many. It seemed clear to me that Jeehan’s path and those of the victims of human trafficking had to cross. Her quest for meaning in the wake of the 9/11’s senseless loss of life depended on it.

EB: I really loved the structure of the book––the braided narratives, moving back and forth between New York and Morocco. How did you decide on this structure? And how and why did you choose to have the Morocco chapters move forward chronologically, while the New York chapters bounce around in time? To me it felt reflective of the way that we try to make sense of a traumatic event––rethinking and obsessing over small details, trying to make sense of chaos, all the pieces slowing coming together.

AMB: Fragmented narratives have always been my thing, probably because, as someone who straddles many cultures and who feels rooted in many geographies, I felt early on that fragmented forms leant themselves to the multi-layered stories that emanated out of me. My MFA thesis was an as-yet-unpublished novel entitled: Fragments from a Transparent Page (inspired by Jean Genet’s posthumous novel). Even my early work in experimental cinema was obsessed with fragmentation — in large part because I believe that though we experience life through the linear chronology of time, we remember our lives in far-less linear fashion. I agree with you that trauma further disrupts our attempts at streamlining memory. The manner in which we remember, and how the act of remembering — or forgetting — shapes the very content of our memory is essential to my work as a novelist, for I believe it is essential to our act of making meaning of our lived experience.

In Dune Song the reader watches Jeehan travel deep into the Moroccan desert. We also watch her remember what has come before. And we witness her struggle with her memories, which is why the New York chapters bounce around in time. The thing she is frightened of most — her memories of seeing the Towers crumble, knowing countless souls are being lost before her eyes — this she cannot remember, or refuses to remember clearly. And it is not until she is in the heart of the desert and is confronted with the images of the collapse of the WTC as beamed through a small TV screen in Fatima’s kitchen, that she takes the reader with her into the recollection of that trauma. Once that remembering is done, her healing can truly begin — and the time of the novel heads in a more chronological direction.

EB: While this is a work of fiction, I imagine that a significant amount of research went into writing this book, especially concerning the horrors of human trafficking. What sorts of research did you do for Dune Song?

AMB: As I mentioned earlier, beginning in the mid-nineties, the issue of human trafficking across the Sarah became a subject of academic and moral concern to me. But the fact that I grew up in Morocco, and spent many of my summers in my paternal grandmother’s house in Tangier, sensitized me to this topic very early on. Tangier, is located at the most northern-western tip of the African continent, and therefore it is a weigh station for many who aim to cross the Straits of Gibraltar with hopes of getting to Spain, to Europe. I recall a moment when as a teenager I gazed out over the Straits from the cliff of Café Hafa, where Paul Bowles used to write, and imagined that the body of water before me as a watery Berlin Wall. One of my unpublished screenplays, entitled Tangier, focused on the tragedy of those who risked their lives to cross the Straits. So, did I do research to write Dune Song? You bet — I folded into Dune Song topics that had been in the forefront of my consciousness for years.

EB: I know that Dune Song has been published in Morocco by Les Editions Le Fennec, published in the United Kingdom by Sandstone Press, published in France by Les Editions du Mauconduit, and published in the U.S.A. by Interlink Books. What was the experience like, having your book published in different languages and in different countries? Were any changes made to the novel between editions?

AMB: Dune Song was first published in Morocco in an early French translation. Initially this was out of desperation, not choice. I wrote Dune Song in English, and I shopped the English manuscript in the UK and the US to no avail. I was told by people who mattered in literary circles that the book was too transgressive to be published in either the US or UK markets. Suggestion was made to me that I remove all the New York passages from the book if I was to stand a chance of having it hit the English speaking market. I refused to do so and instead worked with my friend and translator, Laurence Larsen to come up with a French version. That being done, I shopped it around in France only to be told that a translation couldn’t be published before the original. Dismissively, I was told to seek-out who might benefit from an author like me existing. The comment hit me like a slap across the face, and I sincerely thought of giving up on the work all together — more than that, I thought I might give up on writing — but my students (who have always been a source of support for me — more on that later) convinced me not to trow in the towel. Once I had the courage to re-examine the question posed to me by the French, I realized that there was a viable answer: the Moroccans. That’s when I contacted Layla Chaouni, celebrated French-language publisher in Casablanca, and asked her if she might want to consider Dune Song for Le Fennec.

Layla’s enthusiasm for the novel marked a huge shift in Dune Song’s fortunes: the book was published in Morocco, won the Special Jury Prize for the Prix Sofitel Tour Blanche, was selected to represent Morocco at the Paris Book fair in 2017, which then lead me (through my Wellesley connections) to gain representation by famed New York literary agent Claire Roberts. It was Claire who got me a contract with Sandstone as well as with Interlink and with Mauconduit — she has been an unconditional champion of my work, and for this I will be eternally grateful. It must be noted that when the book got to Sandstone, I believe it was ‘wounded’ — it had gone through many incarnations, but I was not thrilled with the final outcome. My editor at Sandstone, the fantastic Moria Forsyth gave me the space and guidance to “heal” the manuscript — that is, she identified what was not working and sent me off to fix things, with the promise of publication as a reward for this one last push. The result was the English version that everyone is reading today (published in the UK by Sandstone and in the US by Interlink Publishing). My translator, Laurence Larsen worked diligently to upgrade the French translation for Mauconduit.

It has been a long journey, at times dispiriting, at time exhilarating. I am terribly excited that today, my Dune Song has been published in four countries, and there is hope for more. In the darkest hours of the process, I gave myself permission to give up. “You’ve come to the end of the line,” I told myself, “it’s okay if your stop writing altogether.” In hindsight, hitting rock bottom was essential, because the answer that came back to me was NO. No, I won’t stop writing. I accepted that I might never be published, but I refused to stop writing, for to do so would be to give up on the one action that brought meaning to my life.

EB: You’ve mentioned that Dune Song was originally written in English, though I am guessing, based on your background and reading the book, that you also speak Arabic and French. How and why did you decide to write Dune Song in English? And did you translate the work yourself into the French edition?

AMB: Yes, Dune Song was originally written in English. Though I speak French and Moroccan Arabic (Darija) fluently, my imagination has always constructed itself in English. Growing up in Morocco as of the age of eight, I considered English to be my secret garden — the material of which my invented worlds were made. I had often thought that my return to the United States, at the age of 18 to attend Wellesley, was an attempt to find a home for my words. Even today, living in Paris, I continue to write in English.

I chose not to translate Dune Song into French myself, primarily because my French does not resemble my English — it exists in a different sphere belonging more to the spoken word. I wanted a translator to show me what my literary voice might sound like in French. I have done a fair amount of literary translation, but always from French into English, and not the other way around. Nonetheless, as you rightly noted, I have actively wanted to give my readers the illusion of hearing Arabic and French when reading Dune Song. I like to refer to this as creating Linguistic Polyphony: were the base language (in this case English) is made to sing in different cords. I think my French translator, Laurence Larsen was able to reverse this process and give the French text the illusion of hearing English and Arabic.

EB: In addition to your research, what other books influenced or inspired Dune Song? My fiancé, Richie, happened to be reading the Dune chronicles by Frank Herbert while I was reading your book, and then I laughed to myself when I saw you reference them on page 56.

AMB: The Dune Chronicles, of course! Picture this: a teenage me reading Frank Herbert’s Dune while waiting at the Odaïa Café on the old pirate ramparts of Rabat while my mother was shopping in the medina. I read twelve volumes of the Chronicles. Reading voraciously in English while growing up in Morocco was one of the ways for me to always ensure that my imagination was powering up in English. You’ll note that I give Jeehan this same passion for books. Many of the books that she turns to in her time of need are the books that have shaped who I am and how I see the world: Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, Allende’s House of Spirits, Okri’s The Famished Road, Calvino’s The Colven Vicount, Aristotle’s The Poetics, Edna St. Vincent Millay’s poetry…

EB: What are you currently reading, and/or what have you read recently that you’ve really enjoyed? What would you recommend we all read while laying low in quarantine?

AMB: I’m one of those people who reads many books (fiction, non-fiction, and poetry) at the same time. If I look at my night stand right now, here are the titles I see: in English — Hannah Assadi’s Sonora, Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing, Du Pontes Peebles’ The Air You Breathe, and Margo Berdeshevsky’s poetry collection: Before the Drought, in French — Santiago Amigorena’s Le Ghetto intérieur, and Mahi Binebine’s La Rue du pardon.

In quarantine, Margo’s poetry has provided me with a level of stillness and insight I did not realize I longed for — and has seemed prescient in its understanding of humanity’s relationship to our planet.

EB: On your website, you mention you are also a filmmaker, an artist, and an educator in addition to being a writer. How do you think working in those other fields/mediums influences your writing? How do you think being a writer influences those other pursuits?

AMB: Writing as an act of meaning making is the mantra I constantly recite to my students. In my moment of greatest despair, they echoed it back to me. Why do I allow myself this type of discourse with my students? Because as a high school teacher of English and Literature, my speciality is the teaching of writing. While at Columbia University, though enrolled in a Masters of Fine Arts in Fiction at the School of the Arts, I had a fellowship at Columbia Teachers College, specifically with The Writing Project lead by Lucy Calkins (today known as The Reading and Writing Project). There I worked as a staff developer in the NYC Public School system and conducted research that contributed to Lucy’s seminal text, The Art of Teaching Writing. Over the years my students have helped me realize why we bother to tell stories and how elemental writing is to our very humanity. I could never divorce my writing from the act of teaching.

Regarding cinema, as I mentioned earlier, my frustration with how to translate multi-lingual texts into one language is what originally drove me to experiment with film. What I discovered as I dove deeper into the medium, was how key images are to the act of storytelling. Once I returned to writing literature, I retained this awareness of the centrality images in the transmission of lived experience. I smile when readers of Dune Song point out how cinematic my writing is — film and fiction should not stand in opposition one to the other.

EB: Writing a book takes a really long time and can be a really lonely and frustrating experience. Who did you rely on for support during the process? Other writers? Family? Friends? Fellow Wellesley grads? What does your writing/artistic community look like?

AMB: It took me over ten years to write and publish Dune Song. The tale of how it came to be is almost worthy of a novel itself. When things were at their most arduous, I went back to reading Tillie Olsen’s Silences, about how challenging it is for women to write and publish — it was a book I had been asked to read the summer before my Freshman year. Though I won’t tell the full story here — I must acknowledge that without the support of my sister, Yasmina, and my parents, as well as essential and amazing women in my life, many of them from Wellesley, Dune Song would never have seen the light of day. Sally Katz ‘78, has been my fairy-godmother, all good things come to me from her, plus other members of the astounding Wellesley Club of France, especially its current president, my dear classmate, Pamela Boulet ‘87. I must thank my earliest Wellesley friend, Piya Chatterjee ’87, who plowed through voluminous and flawed drafts. Karen E. Smith ’87, who reminded me of my creative abilities when I seemed to have forgotten, and who brought her daughter to my London book launch. Dawn Norfleet ’87 who collaborated with me on my film work when we were both at Columbia, and Rebecca Gregory ’87, with who was first in line to buy Dune Song at WH Smith Rue de Rivoli, and Kimberly Dozier ’87, who raised a glass of champagne with me in Casablanca when the book first came back from the printers. The list of those who helped me get this far and who continue to help me as I forge ahead is long - and for this I am grateful… writing is a thrilling but difficult endeavor, and without community and friendship, it becomes harder.

And since the book has been published, the Wellesley community has been there for me in ways big and small, even in this time of COVID. Out in Los Angeles, Judy Lee ’87 inspired her fellow alums to read Dune Song by raffling a copy off a year ago — and now, they have invited me to speak to their club on a Zoom get-together in June!

EB: Speaking of Wellesley, and since this is an interview for Wellesley Underground, were there any Wellesley professors or staff or courses that were particularly formative to you as a writer? Anyone you want to shout out here?

AMB: When a student at Wellesley, a number of Professors where particularly supportive of me and my work. At the time, I was a Political Science and Anthropology major; Linda Miller and Lois Wasserspring of the Poli-Sci department were influential and present even long after I graduated, and Sally Merri and Anne Marie Shimony of the Anthropology department helped shape the way I see the world.

Any mention of my early Wellesley influences must include Sylvia Heistand, at Salter International Center, and my Wellesley host-mother, Helen O’Connor — who still stands in for my mother when needed!

More recently, Selwyn Cudjoe and the entire Africana Studies Department, have become champions of my work. Thanks to their enthusiasm for Dune Song, I was able to present the novel at Harambee House last October and engage in dialogue about my work with current Wellesley students and faculty. This was a remarkable experience which gave me a beautiful sense of closure regarding the ten-year project that has been Dune Song. Merci Selwyn!

I speak of closure, but my Dune Song journey continues, just before the pandemic, thanks to the Wellesley Club of France and Laura Adamczyk ’87, I was able to meet President Johnson and give her a copy of Dune Song!

EB: Is there anything else you’d like the Wellesley community to know about Dune Song, your other projects, or you in general?

AMB: Way back at the start of the millennium, when the Wellesley awarded me the Mary Elvira Stevens Traveling Fellowship, I set out to excavate family secrets and explore the non-verbal ways in which generation upon generation of mothers transmit traumatic memories to their daughters. My research took me many more years than expected, but I am now in the process of writing that novel, along with a doctoral thesis on Trauma and Memory.

In conjunction with this second novel, I am working with Rebecca Gregory ’87, to produce a large-scale installation piece exploring the manner in which the stories of women’s lives are measured and told.

EB: Thank you for being part of Wellesley Writes It!

#wellesley writes it#wellesleywritesit#Anissa M. Bouziane#Anissa Bouziane#class of 1987#EB Bartels#E.B. Bartels#class of 2020#wellesley#wellesley college#Dune Song#France#Morocco#New York#USA#book#books#novel#novels#wellesley '87#wellesley '10

1 note

·

View note

Text

Featured Author Interview: Rob Shackleford

Tell us about yourself and your books.:

Hi, My name is Rob Shackleford and I live on the Gold Coast in Australia with Deborah-Jane, my partner. We each have a son and a daughter and, because they are living away from home and have not yet decided to have kids, we are in that sweet spot in time when we can, and do, travel when we can.

I have written a few books but I have only one, Traveller Inceptio, that is published so far.

Traveller Inceptio is a blend of Science Fiction and Historical Fiction which examines what could really happen if we placed 21st Century researchers into 11th Century Saxon England. If you were placed there, would you survive? How do you think you would fare with the food, the clothes, the language or the superstitions? What about the lack of law and order and the threat of violence?

My inspiration came after I was ripped off by a dishonest business partner and I sat on the beach and was forced to look at my options. While there I looked at the buildings around me and imagined what the location would look like 100 years in the past, then 200 years when white explorers first arrived, then 1000 years ago. A story began to form, which became Traveller Inceptio. Inceptio means "Beginning" in Latin, the religious language spoken in the time. I had to add that part of the title because, have you seen how many books there are with the title, 'Traveller'? Dozens!

Do you have any unusual writing habits?

I generally write in the morning. If I have a flash of inspiration, that means I can get up as early as 4am. After a few hours we go for a walk and a coffee. By midday I gym and then sometimes play the Play Station while I think about my research or seek inspiration while I am killing zombies or whatever.

I do research a lot! With Traveller Inceptio I lacked the confidence to write so I thoroughly researched for about a year before I dared write anything. I live in terror of having wrong information, of a historian saying - "Oh, this is rubbish because xyz!" My local library banned me at one stage as I had a really good book on Saxon history out for 6 months.

The most unusual thing is how sometimes I can write and it doesn't feel like I am writing, where the story develops in ways I had not anticipated, where I go, "Wow! I didn't know that was going to happen!"

What authors have influenced you?

There are so many!

I admire the beautiful descriptive writing of 'The Life of Pi's Yann Martel, 'Shantaram's Gregory David Roberts, or Colleen McCullough's superb series of novels on Rome.

I love brilliant imagination and the ability to story-tell as shown in the warped imagination of Steven King, Tolkien and even the simplicity of 'The Martian's Andy Weir.

I am also astounded by the pure brilliance of the research undertaken by historian Simon Sebag Montfiore and his range of excellent novels, and of course Bernard Cornwell.

Last but not least I adore the Science Fiction greats - Arthur C Clarke, Frank Herbert, Robert Heinlein, Greg Bear and so many others who make our imaginations soar beyond the stars.

And these are but a few. I will post this and then say - "How could I have forgotten ...?"

Do you have any advice for new authors?

1. Persist. I heard a cheesy saying from an author I can't recall, which goes: "The successful Author is the one who persisted." Take some hope in that most authors have had to scarper naked through the valley of death.

2. Being an author is about being commercially viable. Modern publishers want to make money off you, web sites want to make money off you, the various nebulous publishing services do too. Be judicious about where you spend your money and understand this is a business like the music industry. In the end you will have to watch out!

3. Be true to yourself. You work is your work, but also accept that sometimes a suggestion might be good for you. The first time I had Traveller Inceptio edited it was by a grumpy old bastard of an Englishman who tore off my arm and beat me over the head with it. Thanks to his bemoaning of my abilities I was compelled to relook at what was written, removed some chapters, cut the length of my manuscript, and essentially was forced to concede that I had a lot to learn. He also hated one of my characters as it reminded him of a kid who bullied him when he was at school, which was brilliant! It meant my character development touched a chord in him, even though it might have been negative.

4. Each literary masterpiece started with the first written word. Start your work and don't be too hard on yourself. Let the work emerge when it will, but write something! It is easier to edit than to make the first utterance. Good luck and have fun!!

What is the best advice you have ever heard?

Don't believe everything you think!

What are you reading now?

I am about to embark on a journey in India, so I am reading "The Story of India" by Michael Wood while delving into the darkly realistic world view of Chris Hedges in his brilliant "America - The Farewell Tour."

What's your biggest weakness?

I have a tendency to self-criticism / self deprecation that can lead to negativity when it concerns me. Perhaps not the smartest weakness for a self-motivated author.

What is your favorite book of all time?

No fair!

I like too many books to make such a distinction.

Some fav's are "Dune" by Frank Herbert, The Harry Potter Books, The Lord of the Rings set.

What has inspired you and your writing style?

I do like books that have me engrossed in the world the author creates. As I am a lover of History and Science Fiction, it perhaps was logical that I would find joy in blending the genres.

But I don't have a calculated, premeditated style where the story is already know. The first draft of my books is essentially a story I am telling. The frequent rewrites then allow me to better define my language and the imagery I hope allows the reader to become immersed into the universe I have created.

My inspiration can be attributed in part to the great authors I read and to my love of the topic on hand.

What are you working on now?

Traveller Inceptio lends itself to a sequel, so I have completed Traveller Probo - to Prove - which delves more into the political machinations that would eventuate in the world with the Transporter - the device that allows researchers to be sent back 1000 years. there are more locations, some of the old characters, and what I believe would be the logical continuation of the story.

Traveller Probo has been polished to be worthy of an editor, while part 3 - Traveller Manifesto - is the conclusion (!?) and is also under final review by me.

I have also written a couple of novels that are not part of the Traveller universe which are under review and edit.

What is your method for promoting your work?

I have a Publisher - Austin Macauley - and to a certain extent I rely on their promotion of my work.

Alas, modern publishing also relies on the efforts of the author, so I am compelled to engage in Social Media, where I must engage daily in Instagram, Facebook, Linked In, Twitter and Pinterest.

Perhaps most beneficial is my engagement with almost 1000 literary bloggers in whom I have trusted to review Traveller Inceptio. That has been an interest process of highs and lows, for no work will satisfy everyone who agrees to review it. Yes, there have been tears, but I have also received validation that my work is good enough to withstand commercial scrutiny.

Next step: Looking for a Literary Agent!

What's next for you as a writer?

Next is the commercially positive outcome for Traveller Inceptio that will allow the publication of Book 2 - Traveller Probo.

Meanwhile I will continue to market, engage in book signings, and write. I am not sure of there is room for a 4th Traveller novel - I am thinking a set of short stories from the universe - so I will analyse that while I engage in other projects.

How well do you work under pressure?

I place myself under pressure but prefer the pressure not to be external. In the creative field of literary writing / storytelling I prefer to let myself be the taskmaster.

The best motivation for me would be to be assured my work would receive a welcome review.

How do you decide what tone to use with a particular piece of writing?

I try to be realistic in my tone - which means the tone would vary with the circumstances. Most humans tend to have a sense of humor, so the most serious of circumstance could have the note of light-hearted banter.

In times of fear, violence, or despair the tone becomes shorter and sharper, for the human mind has little need or patience for frivolity. These moments are reflected in my mood and I find I become upset and even angry when faced with violence, especially against women.

Author Websites and Profiles

Rob Shackleford Website

Rob Shackleford Amazon Profile

Rob Shackleford's Social Media Links

Facebook Profile

Twitter Account

Instagram Account

Pinterest Account

YouTube Account

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Star Control II

In this vaguely disturbing picture of Toys for Bob from 1994, Paul Reiche is at center and Fred Ford to the right. Ken Ford, who joined shortly after Star Control II was completed, is to the left.

There must have been something in the games industry’s water circa 1992 when it came to the subject of sequels. Instead of adhering to the traditional guidelines — more of the same, perhaps a little bigger — the sequels of that year had a habit of departing radically from their predecessors in form and spirit. For example, we’ve recently seen how Virgin Games released a Dune II from Westwood Studios that had absolutely nothing to do with the same year’s Dune I, from Cryo Interactive. But just as pronounced is the case of Accolade’s Star Control II, a sequel which came from the same creative team as Star Control I, yet which was so much more involved and ambitious as to relegate most of what its predecessor had to offer to the status of a mere minigame within its larger whole. In doing so, it made gaming history. While Star Control I is remembered today as little more than a footnote to its more illustrious successor, Star Control II remains as passionately loved as any game from its decade, a game which still turns up regularly on lists of the very best games ever made.

Like those of many other people, Paul Reiche III’s life was irrevocably altered by his first encounter with Dungeons & Dragons in the 1970s. “I was in high school,” he remembers, “and went into chemistry class, and there was this dude with glasses who had these strange fantasy illustrations in front of him in these booklets. It was sort of a Napoleon Dynamite moment. Am I repulsed or attracted to this? I went with attracted to it.”

In those days, when the entire published corpus of Dungeons & Dragons consisted of three slim, sketchy booklets, being a player all but demanded that one become a creator — a sort of co-designer, if you will — as well. Reiche and his friends around Berkeley, California, went yet one step further, becoming one of a considerable number of such folks who decided to self-publish their creative efforts. Their most popular product, typed out by Reiche’s mother on a Selectric typewriter and copied at Kinko’s, was a book of new spells called The Necromican.

That venture eventually crashed and burned when it ran afoul of that bane of all semi-amateur businesses, the Internal Revenue Service. It did, however, help to secure for Reiche what seemed the ultimate dream job to a young nerd like him: working for TSR itself, the creator of Dungeons & Dragons, in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. He contributed to various products there, but soon grew disillusioned by the way that his own miserable pay contrasted with the rampant waste and mismanagement around him, which even a starry-eyed teenage RPG fanatic like him couldn’t fail to notice. The end came when he spoke up in a meeting to question the purchase of a Porsche as an executive’s company car. That got him “unemployed pretty dang fast,” he says.

So, he wound up back home, attending the University of California, Berkeley, as a geology major. But by now, it was the 1980s, and home computers — and computer games — were making their presence felt among the same sorts of people who tended to play Dungeons & Dragons. In fact, Reiche had been friends for some time already with one of the most prominent designers in the new field: Jon Freeman of Automated Simulations, designer of Temple of Apshai, the most sophisticated of the very early proto-CRPGs. Reiche got his first digital-game credit by designing The Keys of Acheron, an “expansion pack” for Temple of Apshai‘s sequel Hellfire Warrior, for Freeman and Automated. Not long after, Freeman had a falling-out with his partner and left Automated to form Free Fall Associates with his wife, programmer Anne Westfall. He soon asked Reiche to join them. It wasn’t a hard decision to make: compared to the tabletop industry, Reiche remembers, “there was about ten times the money in computer games and one-tenth the number of people.”

Freeman, Westfall, and Reiche made a big splash very quickly, when they were signed as one of the first group of “electronic artists” to join a new publisher known as Electronic Arts. Free Fall could count not one but two titles among EA’s debut portfolio in 1983: Archon, a chess-like game where the pieces fought it out with one another, arcade-style, under the players’ control; and Murder on the Zinderneuf, an innovative if not entirely satisfying procedurally-generated murder-mystery game. While the latter proved to be a slight commercial disappointment, the former more than made up for it by becoming a big hit, prompting the trio to make a somewhat less successful sequel in 1984.

After that, Reiche parted ways with Free Fall to become a sort of cleanup hitter of a designer for EA, working on whatever projects they felt needed some additional design input. With Evan and Nicky Robinson, he put together Mail Order Monsters, an evolution of an old Automated Simulations game of monster-movie mayhem, and World Tour Golf, an allegedly straight golf simulation to which the ever-whimsical Reiche couldn’t resist adding a real live dinosaur as the mother of all hazards on one of the courses. Betwixt and between these big projects, he also lent a helping hand to other games: helping to shape the editor in Adventure Construction Set, making some additional levels for Ultimate Wizard.

Another of these short-term consulting gigs took him to a little outfit called Binary Systems, whose Starflight, an insanely expansive game of interstellar adventure, had been in production for a couple of years already and showed no sign of being finished anytime soon. This meeting would, almost as much as his first encounter with Dungeons & Dragons, shape the future course of Reiche’s career, but its full import wouldn’t become clear until years later. For now, he spent two weeks immersed in the problems and promise of arguably the most ambitious computer game yet proposed, a unique game in EA’s portfolio in that it was being developed exclusively for the usually business-oriented MS-DOS platform rather than a more typical — and in many ways more limited — gaming computer. He bonded particularly with Starflight‘s scenario designer, an endlessly clever writer and artist named Greg Johnson, who was happily filling his galaxy with memorable and often hilarious aliens to meet, greet, and sometimes beat in battle.

Reiche’s assigned task was to help the Starflight team develop a workable conversation model for interacting with all these aliens. Still, he was thoroughly intrigued with all aspects of the project, so much so that he had to be fairly dragged away kicking and screaming by EA’s management when his allotted tenure with Binary Systems had expired. Even then, he kept tabs on the game right up until its release in 1986, and was as pleased as anyone when it became an industry landmark, a proof of what could be accomplished when designers and programmers had a bigger, more powerful computer at their disposal — and a proof that owners of said computers would actually buy games for them if they were compelling enough. In these respects, Starflight served as nothing less than a harbinger of computer gaming’s future. At the same, though, it was so far out in front of said future that it would stand virtually alone for some years to come. Even its sequel, released in 1989, somehow failed to recapture the grandeur of its predecessor, despite running in the same engine and having been created by largely the same team (including Greg Johnson, and with Paul Reiche once again helping out as a special advisor).

Well before Starflight II‘s release, Reiche left EA. He was tired of working on other people’s ideas, ready to take full control of his own creative output for the first time since his independent tabletop work as a teenager a decade before. With a friend named Fred Ford, who was the excellent programmer Reiche most definitely wasn’t, he formed a tiny studio — more of a partnership, really — called Toys for Bob. The unusual name came courtesy of Reiche’s wife, a poet who knew the value of words. She said, correctly, that it couldn’t help but raise the sort of interesting questions that would make people want to look closer — like, for instance, the question of just who Bob was. When it was posed to him, Reiche liked to say that everyone who worked on a Toys for Bob game should have his own Bob in mind, serving as an ideal audience of one to be surprised and delighted.

Reiche and Ford planned to keep their company deliberately tiny, signing only short-term contracts with outsiders to do the work that they couldn’t manage on their own. “We’re just people getting a job done,” Reiche said. “There are no politics between [us]. Once you start having art departments and music departments and this department and that department, the organization gets a life of its own.” They would manage to maintain this approach for a long time to come, in defiance of all the winds of change blowing through the industry; as late as 1994, Toys for Bob would permanently employ only three people.

Yet Reiche and Ford balanced this small-is-beautiful philosophy with a determination to avoid the insularity that could all too easily result. They made it a policy to show Toys for Bob’s designs-in-progress to many others throughout their evolution, and to allow the contracters they hired to work on them the chance to make their own substantive creative inputs. For the first few years, Toys for Bob actually shared their offices with another little collective who called themselves Johnson-Voorsanger Productions. They included in their ranks Greg Johnson of Starflight fame and one Robert Leyland, whom Reiche had first met when he did the programming for Murder on the Zinderneuf — Anne Westfall had had her hands full with Archon — back in the Free Fall days. Toys for Bob and Johnson-Voorsanger, these two supposedly separate entities, cross-pollinated one another to such an extent that they might almost be better viewed as one. When the latter’s first game, the cult-classic Sega Genesis action-adventure ToeJam & Earl, was released in 1991, Reiche and Ford made the credits for “Invaluable Aid.” And the influence which Leyland and particularly Johnson would have on Toys for Bob’s games would be if anything even more pronounced.

Toys for Bob’s first game, which they developed for the publisher Accolade, was called Star Control. With it, Reiche looked all the way back to the very dawn of digital gaming — to the original Spacewar!, the canonical first full-fledged videogame ever, developed on a DEC PDP-1 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology circa 1962. In Star Control as in Spacewar!, two players — ideally, two humans, but potentially one human and one computer player, or even two computer players if the “Cyborg Mode” is turned on — fight it out in an environment that simulates proper Newtonian physics, meaning objects in motion stay in motion until a counter-thrust is applied. Players also have to contend with the gravity wells of the planets around them — these in place of the single star which affects the players’ ships in Spacewar! — as they try to blow one another up. But Star Control adds to this formula a wide variety of ships with markedly differing weaponry, defensive systems, sizes, and maneuvering characteristics. In best rock-paper-scissors fashion, certain units have massive advantages over others and vice versa, meaning that a big part of the challenge is that of maneuvering the right units into battle against the enemy’s. As in real wars, most of the battles are won or lost before the shooting ever begins, being decided by the asymmetries of the forces the players manage to bring to bear against one another. Reiche:

It was important to us that each alien ship was highly differentiated. What it means is, unlike, say, Street Fighter, where your characters are supposedly balanced with one another, our ships weren’t balanced at all, one on one. One could be very weak, and one could be very strong, but the idea was, your fleet of ships, your selection of ships in total, was as strong as someone else’s, and then it came down to which match-up did you find. One game reviewer called it, “Rock, Scissors, Vapor,” which I thought was a great expression.

Of course, even the worst match-ups leave a sliver of hope that a brilliant, valorous performance on the field of battle can yet save the day.

You can play Star Control in “Melee” mode as a straight-up free-for-all. Each player gets seven unique ships from the fourteen in the game, from which she gets to choose one for each battle. First player to destroy all of her opponent’s ships wins. But real strategy — that is to say, strategy beyond the logic of rock-paper-scissors match-ups — comes into play only with the full game, which takes the form of a collection of scenarios where each player must deploy her fleet over a galactic map. In the more complex scenarios, controlling more star systems means more resources at one’s disposal, which can be used to build more and better ships at a player’s home starbase; this part of the game draws heavily from the beloved old Atari 8-bit classic Star Raiders. A scenario editor is also included for players who get bored with the nine scenarios that come with the game.

Star Control strains nobly to accommodate many different play styles and preferences. Just as it’s possible to turn on Cyborg Mode in the strategy game and let the computer do the fighting, it’s also possible to turn on “Psytron Mode” and let the computer do the strategy while you concentrate on blowing stuff up.

Star Control in action. The red ship is the infamous Syreen Penetrator.

Yet the aspect of Star Control that most players seem to remember best has nothing to do with any of these efforts to be all things to all players. At some point in the development process, Reiche and Ford realized they needed a context for all this interstellar violence. They came up with an “Alliance of Free Stars” — which included Earthlings among its numbers — fighting a war against the evil “Ur-Quan Heirarchy.” Each group of allies/thralls conveniently consists of seven species, each with their own unique model of spaceship. Not being inclined to take any of this too seriously, Toys for Bob let their whimsy run wild in creating all these aliens, enlisting Greg Johnson — the creator of the similarly winsome and hilarious aliens who inhabit the galaxy of Starflight — to add his input as well. The rogue’s gallery of misfits, reprobates, and genetic oddities that resulted can’t help but make you smile, even if they are more fleshed-out in the manual rather than on the screen.

Reiche on the origins of the Illwrath, a race of arachnid fundamentalists who “receive spiritual endorsement in the accomplishment of vicious surprise attacks”:

The name “Illwrath” comes from an envelope I saw at the post office, which was being sent to a Ms. McIlwrath in Glasgow, Scotland. I didn’t see the “Mc” at first, and I swear, my first thought was that they must be sending that envelope to an alien. I am sure that somewhere there is a nice little Scottish lady laughing and saying, “Oh, those crazy Americans! Here’s one now calling me an evil, giant, religiously-intolerant space spider — ha, ha, ha, how cute!” Hmm… on second thought, if I am ever found beaten with bagpipes or poisoned with haggis, please contact the authorities.

Around the office, Fred Ford liked to say that the Illwrath had become so darn evil by first becoming too darn righteous, wrapping right around the righteousness scale and yielding results akin to all those old computer games which suddenly started showing negative statistics if you built up your numbers too far. (Personally, I favor this idea greatly, and, indeed, even believe it might serve as an explanation for certain forces in contemporary American politics.)

Reiche on the Mmrnmhrm, an “almost interesting robot race” who “fear vowels almost as much as they do a Dreadnought closing in at full bore”:

When I first named the Mmrnmhrm, they actually had a pronounceable name, with vowels and everything. Then, in a sketch for the captain’s window illustration, I forgot to give them a mouth. Later, someone saw the sketch and asked me how they talked, so I clamped my lips shut and said something like, “Mrrk nsss,” thereby instituting a taboo on vowels in anything related to the race. Though the Mmrnmhrm ended up looking more like Daleks than Humans, the name stuck.

Reiche on the Syreen, a group of “humanoid females” who embody — knowingly, one likes to believe — every cliché about troglodyte gamers and the fairer sex, right down to their bulbous breasts that look like they’re filled with sand (their origin story also involves the San Francisco earthquake of 1989):

It was an afternoon late last October in San Francisco when Fred Ford, Greg Johnson, and I sat around a monitor trying to name the latest ship design for our new game. The space vessel on the computer screen looked like a copper-plated cross between Tin Tin’s Destination Moon rocketship and a ribbed condom. Needless to say, we felt compelled to christen this ship carefully, with due consideration for our customers’ sensibilities as well as our artistic integrity. “How about the Syreen Penetrator?” Fred suggested without hesitation. Instantly, the ground did truly rise up and smite us! WHAM-rumble-rumble-WHAM! We were thrown around our office like the bridge crew of the starship Enterprise when under fire by the Klingons. I dimly remember standing in a doorframe, watching the room flex like a cheap cardboard box and shouting, “Maybe that’s not such a great name!” and “Gee, do you think San Francisco’s still standing?” Of course, once the earth stopped moving, we blithely ignored the dire portent, and the Syreen’s ship name, “The Penetrator,” was graven in code.

Since then, we haven’t had a single problem. I mean, everyone has a disk crash two nights before a program is final, right? And hey, accidents happen. Brake pads just don’t last forever! My limp is really not that bad, and Greg is almost speaking normally these days.

Star Control was released in 1990 to cautiously positive reviews and reasonable sales. For all its good humor, it proved a rather polarizing experience. The crazily fast-paced action game at its heart was something that about one-third of players seemed to take to and love, while the rest found it totally baffling, being left blinking and wondering what had just happened as the pieces of their exploded ship drifted off the screen about five seconds after a fight had begun. For these people, Star Control was a hard sell: the strategic game just wasn’t deep enough to stand on its own for long, and, while the aliens described in the manual were certainly entertaining, this was a computer game, not a Douglas Adams book.

Still, the game did sufficiently well that Accolade was willing to fund a sequel. And it was at this juncture that, as I noted at the beginning of this article, Reiche and Ford and their associates went kind of nuts. They threw out the less-than-entrancing strategy part of the first game, kept the action part and all those wonderful aliens, and stuck it all into a grand adventure in interstellar space that owed an awful lot to Starflight — more, one might even say, than it owed to Star Control I.

As in Starflight, you roam the galaxy in Star Control II: The Ur-Quan Masters to avert an apocalyptic threat, collecting precious resources and even more precious clues from the planets you land on, negotiating with the many aliens you meet and sometimes, when negotiations break down, blowing them away. The only substantial aspect of the older game that’s missing from its spiritual successor is the need to manage a bridge crew who come complete with CRPG-style statistics. Otherwise, Star Control II does everything Starflight does and more. The minigame of resource collection on planets’ surfaces, dodging earthquakes and lightning strikes and hostile lifeforms, is back, but now it’s faster paced, with a whole range of upgrades you can add to your landing craft in order to visit more dangerous planets. Ditto space combat, which is now of the arcade style from Star Control I — if, that is, you don’t have Cyborg Mode turned on, which is truly a godsend, the only thing that makes the game playable for many of us. You still need to upgrade your ship as you go along to fight bigger and badder enemies and range faster and farther across space, but now you also can collect a whole fleet of support ships to accompany you on your travels (thus preserving the rock-paper-scissors aspect of Star Control I). I’m not sure that any of these elements could quite carry a game alone, but together they’re dynamite. Much as I hate to employ a tired reviewer’s cliché like “more than the sum of its parts,” this game makes it all but unavoidable.

And yet the single most memorable part of the experience for many or most of us remains all those wonderful aliens, who have been imported from Star Control I and, even better, moved from the pages of the manual into the game proper. Arguably the most indelible of them all, the one group of aliens that absolutely no one ever seems to forget, are the Spathi, a race of “panicked mollusks” who have elevated self-preservation into a religious creed. Like most of their peers, they were present in the first Star Control but really come into their own here, being oddly lovable despite starting the game on the side of the evil Ur-Quan. The Spathi owe more than a little something to the Spemin, Starflight‘s requisite species of cowardly aliens, but are based at least as much, Reiche admits a little sheepishly, on his own aversion to physical danger. Their idea of the perfect life was taken almost verbatim from a conversation about same that Reiche and Ford once had over Chinese food at the office. Here, then, is Reiche and the Spathi’s version of the American Dream:

I knew that someday I would be vastly rich, wealthy enough to afford a large, well-fortified mansion. Surrounding my mansion would be vast tracts of land, through which I could slide at any time I wished! Of course, one can never be too sure that there aren’t monsters hiding just behind the next bush, so I would plant trees to climb at regular, easy-to-reach intervals. And being a Spathi of the world, I would know that some monsters climb trees, though often not well, so I would have my servants place in each tree a basket of perfect stones. Not too heavy, not too light — just the right size for throwing at monsters.

“Running and away and throwing rocks,” explains Reiche, “extrapolated in all ways, has been one of my life strategies.”

The Yehat, who breed like rabbits. Put the one remaining female in the galaxy together with the one remaining male, wait a couple of years… and poof, you have an army of fuzzy little warmongers on your side. They fight with the same enthusiasm they have for… no, we won’t go there.

My personal favorite aliens, however, are the bird-like Pkunk, a peaceful, benevolent, deeply philosophical race whose ships are nevertheless fueled by the insults they spew at their enemies during battle. They are, of course, merely endeavoring to make sure that their morality doesn’t wrap back around to zero and turn them evil like the Illwrath. “Never be too good,” says Reiche. “Insults, pinching people when they aren’t looking… that’ll keep you safe.”

In light of the aliens Greg Johnson had already created for Starflight, not to mention the similarities between Starflight‘s Spemin and Star Control‘s Spathi, there’s been an occasional tendency to perhaps over-credit his contribution — valuable though it certainly was — to Toy’s for Bob’s own space epic. Yet one listen to Reiche and Ford in interviews should immediately disabuse anyone of the notion that the brilliantly original and funny aliens in Star Control II are there entirely thanks to Johnson. After listening to Reiche in particular for a few minutes, it really is blindingly obvious that this is the sense of humor behind the Spathi and so many others. Indeed, anyone who has played the game can get a sense of this just from reading some of his quotes in this very article.

There’s a rich vein of story and humor running through even the most practical aspects of Star Control II, as in this report from a planet’s surface. The two complement one another rather than clashing, perhaps because Toys for Bob is clever enough to understand that less is sometimes more. Who are the Lieberman triplets? Who knows? But the line makes you laugh, and that’s the important thing. When a different development team took the reins to make a Star Control III, Reiche’s first piece of advice to them was, “For God’s sake, don’t try to explain everything.” Many a lore-obsessed modern game could afford to take the same advice to heart.

Long after every other aspect of the game has faded from memory, its great good humor, embodied in all those crazy aliens, will remain. It may be about averting a deadly serious intergalactic apocalypse, but, for all that, Star Control II is as warm and fuzzy a space opera as you’ll ever see.

Which isn’t to say that it doesn’t go in for plot. In fact, the sequel’s plot is as elaborate as its predecessor’s was thin; the backstory alone takes up some twenty pages in the manual. The war which was depicted in Star Control I, it turns out, didn’t go so well for the good guys; the sequel begins with you entering our solar system in command of the last combat-worthy craft among a shattered and defeated Alliance of Free Stars. The Ur-Quan soon get wind of your ship’s existence and the last spark of defiance against their rule that it represents, and send a battlefleet toward Earth to snuff it out. And so the race is on to rebuild the Alliance and assemble a fleet of your own before the Ur-Quan arrive. How you do so is entirely up to you. Suffice to say that Earth’s old allies are out there. It’s up to you to find the aliens and convince them to join you in whatever sequence seems best, while finding the resources you need to fuel and upgrade your spaceship and juggling a whole lot of other problems at the same time. This game is as nonlinear as they come.

Star Control II takes itself seriously in the places where it’s important to do so, but never too seriously. Anyone bored with the self-consciously “dark” fictions that so often dominate in our current era of media will find much to appreciate here.

When asked to define what makes a good game, Paul Reiche once said that it “has to have a fun core, which is a one-sentence description of why it’s fun.” Ironically, Star Control II is an abject failure by this standard, pulling in so many directions as to defy any such holistic description. It’s a strategy game of ship and resource management; it’s an action game of ship-versus-ship combat; it’s an adventure game of puzzle-solving and clue-tracking. Few cross-genre games have ever been quite so cross-genre as this one. It really shouldn’t work, but, for the most part anyway, it does. If you’re a person whose ideal game lets you do many completely different things at every session, this might just be your dream game. It really is an experience of enormous richness and variety, truly a game like no other. Small wonder that it’s attracted a cult of players who will happily declare it to be nothing less than the best game ever made.

For my part, I have a few too many reservations to go quite that far. Before I get to them, though, I’d like to let Reiche speak one more time. Close to the time of Star Control II‘s release, he outlined his four guiding principles of game design. Star Control II conforms much better to these metrics than it does to that of the “one-sentence description.”

First, [games should be] fun, with no excuses about how the game simulates the agony and dreariness of the real world (as though this was somehow good for you). Second, they [should] be challenging over a long period of time, preferably with a few ability “plateaus” that let me feel in control for a period of time, then blow me out of the water. Third, they [should] be attractive. I am a sucker for a nice illustration or a funky riff. Finally, I want my games to be conceptually interesting and thought-provoking, so one can discuss the game with an adult and not feel silly.

It’s in the intersection between Reiche’s first and second principles that I have my quibbles with Star Control II. It’s a rather complicated, difficult game by design, which is fair enough as long as it’s complex and difficult in a fun way. Some of its difficulty, however, really doesn’t strike me as being all that much fun at all. Those of you who’ve been reading this blog for a while know that I place enormous weight on fairness and solubility when it comes to the games I review, and don’t tend to cut much slack to those that can only be enjoyed and/or solved with a walkthrough or FAQ to hand. On this front, Star Control II is a bit problematic, due largely to one questionable design choice.

Star Control II, you see, has a deadline. You have about five years before Earth is wiped out by the Ur-Quan (more precisely, by the eviller of the two factions of the Ur-Quan, but we won’t get into that here). Fans will tell you, by no means entirely without justification, that this is an essential part of the game. One of the great attractions of Star Control II is its dynamic universe which just keeps evolving, with or without your intervention: alien spaceships travel around the galaxy just like yours is doing, alien races conquer others and are themselves conquered, etc.

All of this is undoubtedly impressive from a game of any vintage, let alone one as old and technologically limited as this one. And the feeling of inhabiting such a dynamic universe is undoubtedly bracing for anyone used to the more static norm, where things only happen when you push them to happen. Yet it also has its drawbacks, the most unfortunate of which is the crushing sense of futility that comes after putting dozens of hours into the game only to lose it irrevocably. The try-and-try-again approach can work in small, focused games that don’t take long to play and replay, such as the early mysteries of Infocom. In a sprawling epic like this, however… well, does anyone really want to put those dozens of hours in all over again, clicking through page after page of the same text?

Star Control II‘s interface felt like something of a throwback even in its own time. By 1992, computer games had almost universally moved to the mouse-driven point-and-click model. Yet this game relies entirely on multiple-choice menus, activated by the cursor keys and/or a joystick. Toys for Bob was clearly designing with possible console ports in mind. (Star Control was ported to the Sega Genesis, but, as it happened, Star Control II would never get the same honor, perhaps because its sales didn’t quite justify the expense and/or because its complexity was judged unsuited to the console market.) Still, for all that it’s a little odd, the interface is well thought-through, and you get used to it quickly.

There’s an undeniable tension between this rich galaxy, full of unusual sights and entertaining aliens to discover, and the need to stay relentlessly on-mission if you hope to win in the end. I submit that the failure to address this tension is, at bottom, a failure of game design. There’s much that could have been done. One solution might have been to tie the evolving galaxy to the player’s progress through the plot rather than the wall clock, a technique pioneered in Infocom’s Ballyhoo back in 1986 and used in countless narrative-oriented games since. It can convey the impression of rising danger and a skin-of-the-teeth victory every time without ever having to send the player back to square one. In the end, the player doesn’t care whether the exhilarating experience she’s just had is the result of a meticulous simulation coincidentally falling into place just so, or of a carefully manipulated sleight of hand. She just remembers the subjective experience.

But if such a step is judged too radical — too counter to the design ethos of the game — other remedies could have been employed. To name the most obvious, the time limit could have been made more generous; Starflight as well has a theoretical time limit, but few ever come close to reaching it. Or the question of time could have been left to the player — seldom a bad strategy in game design — by letting her choose from a generous, moderate, and challenging time limit before starting the game. (This approach was used to good effect by the CRPG The Magic Candle among plenty of other titles over the years.)

Instead of remedying the situation, however, Reiche and his associates seemed actively determined to make it worse with some of their other choices. To have any hope of finishing the game in time, you need to gain access to a new method of getting around the galaxy, known as “quad-space,” as quickly as possible. Yet the method of learning about quad-space is one of the more obscure puzzles in the game, mentioned only in passing by a couple of the aliens you meet, all too easy to overlook entirely. Without access to quad-space, Star Control II soon starts to feel like a fundamentally broken, unbalanced game. You trundle around the galaxy in your truck of a spaceship, taking months to reach your destinations and months more to return to Earth, burning up all of the minerals you can mine just to feed your engines. And then your time runs out and you lose, never having figured out what you did wrong. This is not, needless to say, a very friendly way to design a game. Had a few clues early on shouted, “You need to get into quad-space and you may be able to do so here!” just a little more loudly, I may not have felt the need to write any of the last several paragraphs.

I won’t belabor the point any more, lest the mob of Star Control II zealots I can sense lurking in the background, sharpening their pitchforks, should pounce. I’ll say only that this game is, for all its multifaceted brilliance, also a product of its time — a time when games were often hard in time-extending but not terribly satisfying ways, when serious discussions about what constituted fair and unfair treatment of the player were only just beginning to be had in some quarters of the industry.

Searching a planet’s surface for minerals, lifeforms, and clues. Anyone who has played Starflight will feel right at home with this part of the game in particular.

Certainly, whatever our opinion of the time limit and the game’s overall fairness, we have to recognize what a labor of love Star Control II was for Paul Reiche, Fred Ford, and everyone who helped bring it to fruition, from Greg Johnson and Robert Leyland to all of the other writers and artists and testers who lent it their talents. Unsurprisingly given its ambition, the project went way beyond the year or so Accolade had budgeted for it. When their publisher put their foot down and said no more money would be forthcoming, Reiche and Ford reached deep into their own pockets to carry it through the final six months.

As the project was being wrapped up, Reiche realized he still had no music, and only about $1500 left for acquiring some. His solution was classic Toys for Bob: he ran an online contest for catchy tunes, with prizes of $25, $50, and $100 — in addition to the opportunity to hear one’s music in (hopefully) a hit game, of course. The so-called “tracker” scene in Europe stepped up with music created on Commodore Amigas, a platform for which the game itself would never be released. “These guys in Europe [had] just built all these ricky-tink programs to play samples out,” says Reiche. “They just kept feeding samples, really amazing soundtracks, out into the net just for kicks. I can’t imagine any of these people were any older than twenty. It makes me feel like I’m part of a bigger place.”

Upon its release on November 30, 1992 — coincidentally, the very same day as Dune II, its companion in mislabeled sequels — Star Control II was greeted with excellent reviews, whose enthusiasm was blunted only by the game’s sheer unclassifiability. Questbusters called it “as funny a parody of science-fiction role-playing as it is a well-designed and fun-to-play RPG,” and named it “Best RPG of the Year” despite it not really being a CRPG at all by most people’s definitions. Computer Gaming World placed it on “this reviewer’s top-ten list of all time” as “one of the most enjoyable games to review all year,” and awarded it “Adventure Game of the Year” alongside Legend Entertainment’s far more traditional adventure Eric the Unready.

Sales too were solid, if not so enormous as Star Control II‘s staying power in gamers’ collective memory might suggest. Like Dune II, it was probably hurt by being billed as a sequel to a game likely to appeal most to an entirely different type of player, as it was by the seeming indifference of Accolade. In the eyes of Toys for Bob, the developer/publisher relationship was summed up by the sticker the latter started putting on the box after Star Control II had collected its awards: “Best Sports Game of 1992.” Accolade was putting almost all of their energy into sports games during this period, didn’t have stickers handy for anything else, and just couldn’t be bothered to print up some new ones.

Still, the game did well enough that Toys for Bob, after having been acquired by a new CD-ROM specialist of a publisher called Crystal Dynamics, ported it to the 3DO console in 1994. This version added some eight hours of spoken dialog, but cut a considerable amount of content that the voice-acting budget wouldn’t cover. Later, a third Star Control would get made — albeit not by Toys for Bob but by Legend Entertainment, through a series of intellectual-property convolutions we won’t go into in this article.

Toys for Bob themselves have continued to exist right up to the present day, a long run indeed in games-industry terms, albeit without ever managing to return to the Star Control universe. They’re no longer a two-man operation, but do still have Paul Reiche III and Fred Ford in control.

To this day, Star Control II remains as unique an experience as it was in 1992. You’ve never played a game quite like this one, no matter how many other games you’ve played in your time. Don’t even try to categorize it. Just play it, and see what’s possible when a talented design team throws out all the rules. But before you do, let me share just one piece of advice: when an alien mentions something about a strange stellar formation near the Chandrasekhar constellation, pay attention! Trust me, it will save you from a world of pain…

(Sources: Compute!’s Gazette of November 1984; Compute! of January 1992 and January 1993; Computer Gaming World of November 1990, December 1990, March 1993, and August 1993; InterActivity of November/December 1994; Questbusters of January 1993; Electronic Gaming Monthly of May 1991; Sega Visions of June 1992; Retro Gamer 14 and 15. Online sources include Ars Technica‘s video interview with Paul Reiche III and Fred Ford; Matt Barton’s interviews with the same pair in Matt Chat 95, 96, and 97; Grognardia‘s interview with Reiche; The Escapist‘s interview with Reiche; GameSpot‘s interview with Reiche.

There’s a rather depressing pitched legal dispute swirling around the Star Control intellectual property at the moment, which has apparently led to Star Control I and II being pulled from digital-download stores. Your best option to experience Star Control II is thus probably The Ur-Quan Masters, a loving open-source re-creation based on Toys for Bob’s 3DO source code. Or go hunt down the original on some shadowy corner of the interwebs. I won’t say anything if you don’t.)

source http://reposts.ciathyza.com/star-control-ii/

1 note

·

View note