#iggers

Text

Voyage à Bali. Un moment hors du temps.

Fleur de Lotus.

Offrandes.

Paysage de Rizière

Plage de Nusa Lembogan

Petit déjeuner à Ubud

Plages de Nusa Lembogan

1 note

·

View note

Text

/holds out pizza box.

finish this for me.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

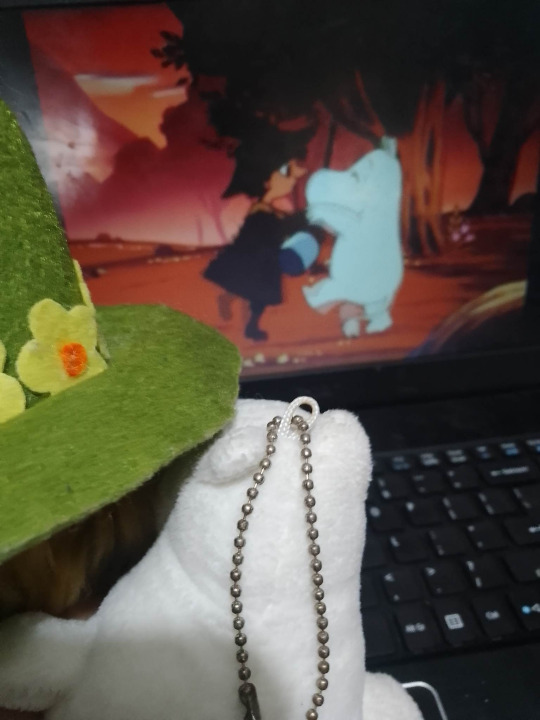

YESSS MY BOYS ARE HOMEEEEEEEE!!!!!

Moomin is so tiny tbh ToT

Making them watch 90s moomin

#EEEEEK THEYRE HOMEEEE#I WISH I COULD GET THE IGGER MOOMIN PLUSH THO BUT THEY SOLD OUT ToT#IM STILL SO HAPPY THO!!!#snkrunly#snufkin#moomin#moomintroll#snusmumriken#mumintrollet#nuuskamuikkunen#moomins#moominvalley#snufmin

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

No Better than a Horse

A young student came to Tam and Chacham and asked to receive semichah – rabbinical ordination. Tam was studying from a holy book while Chacham stood at the window looking out at the snow-covered courtyard.

Tam asked the young student about himself, and the student told him he was determined to live a pure and holy life. “interesting”, and how do you do that?” asked Tam. “I pray with strength and…

View On WordPress

#Berachos 16b#Faith#horse#Iggeres ha-v’Kuach#inspirational stories#Jewish Stories#Sefer ha-Kuzari#short stories#spiritual storiesGenesis 2:7#spituality#Torah

0 notes

Text

Some human Koopalings stuffs I uploaded in the Koopalings and Broodals discord server!!!!!! Featuring some fake anime screenshots I drew in 2023 and a couple of Iggers

and yes this is a reminder for y'all to join my server

do it or I'll eat your cereal

#fanart#digital art#digital illustration#super mario bros#super mario#nintendo#koopalings#morton koopa jr#wendy o koopa#larry koopa#lemmy koopa#iggy koopa#gijinka#humanization#human version#artists on tumblr

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

*hic*

Hi.

I M-key.

*hic*

Ur even igger an da other one.

Hehehe.

*hic*

🥴

Are you alright..?

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flower Family

Bruno’s gift of controlling plants was seen as a blessing

He would use his power to instantly grow crops for the village

He and Julieta were golden children while Pepa was a scapegoat

Bruno became his sister’s protector and they were very close though a part of her did resent him and Julieta

Bruno when he was younger had tried to branch out and experiment with his gift but was always brushed off or scolded for it

He didn’t stop his experiments though he just kept them confined to his room the one place he felt he could be himself

Eventually he created a plant turtle he named twig

One day Alma decided that her children needed to start seeing some of their suitors and introduced Pepa to Felix Algeria surprisingly they got on well

It’s also how Bruno met Ozma the illegitimate child of Felix’s father they kept their meeting’s secret

Julieta on the other hand started courting, a boy, their mother disapproved of greatly

She stood her ground on this to her siblings, surprise Julieta never fought their mother on anything

Ozma and Bruno grew close Bruno even showing her his garden and mouse village

Three years passed Bruno and Ozma continued their secret relationship his sisters got married and his mother pestered him to do the same

Eventually this all blew up with Ozma becoming pregnant and Alma trying to arrange a marriage for her son

After an enormous fight where Bruno destroyed the entire town square with his plants he and Ozma eloped taking only Twig a few changes of clothes and some food

They climb the mountain and discover that beyond that is a second ring of mountains with a canyon between them Bruno grows a forest at the bottom of the canyon and grows a treehouse for them and the baby to live in

This attracts people that we’re living in the mountains but not in the Encanto

Soon Ozma gave birth to a beautiful little girl they named Isabela

She was a wild and rambunctious girl and the couple adored her with all their hearts

They were all taken by surprise when the day after Isabelas fifth birthday she woke them to show a cactus she’d grown

they hadn’t thought she’d get magic without casita but were thrilled

Bruno taught her all he could about her power and they experimented and learned new things together

Isabela used her flowers to create paints and use them to decorate the trees with her mother

She even created her own animal plant companion a griffin she named Rose

Life was good and the family was content

and then when Isabela was 16 they had a surprise baby they named Antonio

Life picked up after that their little forest village got a lot of refugees fleeing from the violence

Isabela was looking for a boyfriend wanting to have what her parents had with each other with someone else

But try as she might she never felt that spark with anyone

Soon Antonio also received control over plants and joined his father and sister in the garden

He went out there with animal companions creating a cat he named Parce that kept growing bigger and igger

None of them had thought of the Encanto in years with Antonio thinking it was just a made up bedtime story

That is until Bruno’s Niece Mirabel showed up begging Bruno to return and cure the towns famin

#flower family au#encanto#encanto au#isabella madrigal#bruno madrigal#antonio madrigal#Isabela madrigal#Isabela my beloved

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

A useful book on how history was written through the ages in the Western world:

This will be useful for my future historiography post, also I'm putting it on my summer reading list I guess:

A Companion to Western Historical Thought

Editor(s): Lloyd Kramer, Sarah Maza

First published: 1 January 2002

About this book:

This broad survey introduces readers to the major themes, figures, traditions and theories in Western historical thought, tracing its evolution from biblical times to the present.

Surveys the evolution of historical thought in the Western World from biblical times to the present day.

Provides students with the background to contemporary historical debates and approaches.

Serves as a useful reference for researchers and teachers.

Includes chapters by 24 leading historians.

Table of contents:

Introduction: The Cultural History of Historical Thought by Lloyd Kramer and Sarah Maza, p. 1-12

PART I: THE PRE-MODERN ORIGINS OF WESTERN HISTORICAL THOUGHT

Historiography in Ancient Israel by John Van Seters, p. 15-34

Historical Thought in Ancient Greece by Philip A. Stadter, p. 35-59

Historical Thought in Ancient Rome by J. E. Lendon, p. 60-77

Historical Thought in Medieval Europe by Gabrielle M. Spiegel, p. 78-98

Historical Thought in the Renaissance by Paula Findlen, p. 99-120

PART II: THE SHAPING OF MODERN WESTERN HISTORICAL THOUGHT

Historical Thought in the Era of the Enlightenment by Johnson Kent Wright, p. 123-142

German Historical Thought in the Age of Herder, Kant, and Hegel by Harold Mah, p. 143-165

German Historical Writing from Ranke to Weber: The Primacy of Politics by Harry Liebersohn, p. 166-184

National History in the Age of Michelet, Macaulay, and Bancroft by Thomas N. Baker, p. 185-204

Marxism and Historical Thought by Walter L. Adamson, p. 205-222

PART III: PATTERNS IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY WESTERN HISTORICAL THOUGHT

The Professionalization of Historical Studies and the Guiding Assumptions of Modern Historical Thought by Georg G. Iggers, p. 225-242

The History of Armed Power, by Peter Paret, p. 243-261

Total History and Microhistory: The French and Italian Paradigms by David A. Bell, p. 262- 276

Anthropology and the History of Culture by William M. Reddy, p. 277-296

The History of Science, Or, an Oxymoronic Theory of Relativistic Objectivity by Ken Alder, p. 297-318

Language, Literary Studies, and Historical Thought by Susan A. Crane, p. 319-336

Psychology, Psychoanalysis, and Historical Thought by Lynn Hunt, p. 337-356

Redefining Historical Identities: Sexuality, Gender, and the Self by Carolyn J. Dean, p. 357-371

Historicizing Natural Environments: The Deep Roots of Environmental History Andrew C. Isenberg, p. 372-389

PART IV: CHALLENGES TO THE BOUNDARIES OF WESTERN HISTORICAL THOUGHT

The New World History by Jerry H. Bentley, p. 393-416

Postcolonial History by Prasenjit Duara, p. 417-431

The Multicultural History of Nations by Donna R. Gabaccia, p. 432-446

New Technologies and Historical Knowledge by James M. Murray, p. 447-465

The Visual Media and Historical Knowledge by Robert A. Rosenstone, p. 466-481

#historiography#reading list#summer 2022 reading list#A Companion to Western Historical Thought#sarah maza

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

A volume with views of Chinese historians on the history of Western historiography

Herodotus, the founder of Western historiography, and Sima Qian, the greatest historian of ancient China

“History of Western historiography: The views from China—Introduction

Q. Edward Wang

Pages 73-78 | Published online: 04 May 2020

This issue presents a group of articles written by Chinese scholars on the tradition and transformation of Western historiography. Perhaps somewhat surprising to some of our readers, the subject is an important subfield in the garden of history in China. The course of “History of Western Historiography” or “History of Foreign Historiography,” for instance, is regularly taught to history majors on many college campuses. There are also specialists on the history faculty at several key universities who research and publish around the area and supervise students at both M.A. and Ph.D. levels. In fact, the majority of important historical texts constituting the tradition of European historiography from the ancient to modern periods have already had Chinese translations, readily available to Chinese readers and students. In more recent years, notable studies of the European/Western tradition of historical writing, its modern transformation and contemporary developments by scholars in the Western academe have also been rendered into Chinese. As a result, Chinese history students are familiar with major scholars in the field, such as Lynn Hunt, Peter Burke, Georg Iggers (1926–2017), Donald Kelley, Hayden White (1928–2018) and Frank Ankersmit. Indeed, in China’s historical circles, these scholars’ reputation rivals that of well-known China scholars in the West, such as Philip Kuhn (1933–2016), Frederic Wakeman (1937–2006), Jonathan Spence, Susan Mann, Timothy Brook and Benjamin Elman. And this trend of interest, in my opinion, would probably continue into the future. In January 2019, the Chinese government established the Chinese Academy of History (中國歷史研究院 Zhongguo lish yanjiuyuan) under the auspices of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (中國社會科學院 Zhongguo shehui kexueyuan). Of its six departments, there is an Institute of Historical Theory (歷史理論研究所 lishi lilun yanjiusuo). Its task, needless to say, is to continue exalting the importance of Marxism as the theory in guiding historical research in China. Yet in order to promote the study of Marxism, which originated from the West, it is necessary for Chinese scholars to enhance their knowledge of Western historiography as well as to compare Marxist theory with other theoretical constellations advanced by Western scholars in both Marx’s times and more recent decades.

Looking around the world, it is not a uniquely Chinese phenomenon that the country’s history students and teachers accord substantial attention to Western academic cultures and historiographies. In his influential work, Provincializing Europe, Dipesh Chakrabarty, a prominent postcolonial theorist, has made the following observation:

This engagement with European thought is also called forth by the fact that today the so-called European intellectual tradition is the only one alive in the social science departments of most, if not all, modern universities.

As a result, Chakrabarty continues:

That European works as a silent referent in historical knowledge becomes obvious in a very ordinary way. … Third-world historians feel a need to refer to works in European history; historians of Europe do not feel any need to reciprocate. … “They” [Western historians] produce their work in relative ignorance of non-Western histories, and this does not seem to affect the quality of their work.1

Indeed, not only do historians in the West feel unnecessary to reference the histories of the rest of the world in their writings, but they also feel, as it were, irrelevant to pay attention to how historians outside Euro-America think and study of their history, or the histories of Europe and America. Given the rise of global history, the situation of the former is rapidly changing in recent years—comparative history and historiography, large or small in scope, are becoming increasingly attractive to historians in the West and their counterparts around the world. But no significant improvement has been made on changing the latter, or the indifference of Western historians toward the works of their counterparts in non-Western regions and countries. To a degree, this is perhaps not entirely the fault of Western historians. Concerning scholarly publication, its circulation and translation, there has been an asymmetrical relationship in our world: “Many of the important works in history or related social science and humanistic disciplines are translated from English into non-Western languages, as are important French and German books and articles. But very few Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Farsi, Turkish, or Arabic writings have been translated into English.”2 In other words, many valuable studies of Western history are inaccessible to Western historians as they are untranslated and unavailable. This, of course, also circulates back to the same question addressed earlier: while language proficiency is usually required for a proper training in history, many historians of Britain or the US, for instance, don’t feel the urge to learn a language other than English, which is in stark contrast to their counterparts in other countries and even their colleagues specializing in non-Western history.

All this accounts for the principal reason for editing this issue, which is to showcase some selected studies of Chinese historians on the history of Western historiography. Before moving on to discussing these articles, I think a brief review of the origin and development of Western historiography in China is in order. In China’s long tradition of historical writing, which spanned about two millennia before modern times, it was customarily for historians to record about their neighbors in the surround. Their approach to the writing, however, was ethnocentric, in that they regarded China as the “Middle Kingdom” that radiated its influence, or civilization, outwardly to the neighboring regions. Throughout the period of imperial China, as Ge Zhaoguang, a noted intellectual historian and a frequent contributor to this journal, observes, the idea of “the central empire as the principal, the peripheries as subordinates,” which was formulated by Sima Qian (c. 145–86 BCE) in his magisterial Records of the Grand Historian (史記Shiji), was the guiding principle for Chinese historians to write about the relationship between “China,” or whatever a regime that occupied the Central Plain in a given time, and its relation to and position in the known world. During the long period, Ge avers, there emerged three opportunities for Chinese historians to develop a different worldview, but it was not until the end of the nineteenth century, after a series of defeats the then ruling Qing dynasty (1644–1911) suffered in battling Western powers, that a fundamentally new approach was adopted. This approach was characterized by the full recognition of the development of a multipolar world in modern times, of which China was a part but not the center. As such, it became necessary for Chinese historians to learn and write about the much-expanded world beyond the Sinitic sphere.3

In this newly acquired worldview, the West figured centrally, for it was largely due to the Western powers’ challenge that sufficiently pained Chinese to realize their modern woes as a nation. And from the mid-nineteenth century throughout the twentieth century, this Western-centered worldview persisted, despite the drastic changes happening in the political arena. So much so that in the minds of Chinese students today, “History of Western historiography” is by and large equivalent to “History of foreign historiography.” And, indeed, if one looks and compares the syllabi of the two courses taught in China’s colleges, one often finds that there are substantial overlaps between them, even though the latter is supposed also to cover historical practices in Asia, Africa, South Asia and Latin America. In fact, as shown in Zhang Guangzhi’s article in this issue, the course of “History of Western Historiography” is taught more frequently than its counterpart, “History of Foreign Historiography,” in Chinese universities. Zhang, a seasoned scholar who has witnessed as well as participated in the expansion of the field over the past several decades, also chooses to concentrate his discussion on the teaching of “History of Western Historiography” in the PRC.

As an academic field, the development of the history of Western historiography began only a half century ago in China. Yet from the late nineteenth century, some Chinese historians had already taken an interest in learning about how history was written in the West. In his Pufa zhanji (普法戰紀 Report on the Franco-Prussian War), for example, Wang Tao (王韜 1828–1897), who had gotten an opportunity of sojourning in Scotland while assisting James Legge’s (1815–1897) translation of Chinese Classics, not only recorded the War that led to the German unification, but he also experimented with new ways in constructing his narrative by drawing elements from Western historiography. From the early twentieth century, buoyed by Liang Qichao’s (梁啟超 1873–1929) call for making a “historiographical revolution” (史界革命 Shijie geming), more attempts were made to translate works of Euro-American historians on the nature and methodology of history. He Bingsong’s (何炳松1890–1946) translation of James Harvey Robinson’s New History and Li Sichun’s (李思純 1893–1960) rendition of Charles-Victor Langlois’ and Charles Seignobos’ Introduction aux études historiques were well-known examples at the time.4

Both He and Li were returned students from the West. For the advance of Western historiography as an academic field in China, students with an educational background similar to theirs were forerunners. But the opportunity to formally introduce it into the college curriculum did not occur until 1961, after China, now ruled by the Communists, suffered from the disastrous Great Leap Forward Movement launched by Mao Zedong (1893–1976) in 1958. Perhaps for assuaging the pain and suffering of the Chinese people (the educated Chinese had fared worse because they were severely chastised in the Anti-Rightists Campaign waged by Mao, almost simultaneously as he commanded the Great Leap Forward) had experienced in the previous decade, the Chinese government introduced several projects in the 1960s that permitted, if also covertly encouraged, Chinese historians to find alternatives to the Soviet model of historiography, for, by that time, the honeymoon between Communist China and the Soviet Union had ended. It is perhaps worth noting that in his call for taking the Great Leap Forward, Mao’s hope was for China to catch up with the UK and US, not the USSR. In any case, what transpired was that a group of Western-educated Chinese historians was invited to a meeting held in Shanghai in 1961 by the Department of Education, discussing the likelihood of teaching the course on “History of Western Historiography” and composing a textbook. Motivated by the meeting, some of them also published journal articles in its wake on the need for developing the course and gaining knowledge on Western historiography for history students in China.5

Due to the interruption of the Cultural Revolution, which took place only a few years after but lasted for a decade, Western historiography as a bourgeoning field failed to take root in the 1960s. It was not until the 1980s that its research and teaching were resumed. By the time, most scholars who had received education in the West were already in the retirement age—some had even already passed away. Yet the survivors cherished the hard-earned opportunity and renewed their enthusiasm for plowing and establishing the field. Again, as covered by Zhang Guangzhi’s article, some of the pioneering studies, including valuable translations, of Western historiography were produced by these Western-educated historians from the period, such as Geng Danru (耿淡如 1897–1975), Wu Yujin (吳于廑 1913–1993), Guo Shengming (郭聖銘 1915–2006) and Zhang Zhilian (張芝聯 1918–2007), whose works laid the foundation for historians of younger generations to continue expanding the field to this day.

The importance of the aforementioned scholars, too, is shown that most of the articles sampled here were written by their students and/or students of their students. Wu Xiaoqun, the author of the first article, for instance, worked with Zhang Guangzhi in earning her Ph.D. degree, and Zhang had been a graduate student of Geng Danru during the Cultural Revolution. Taking the recent disputes on Herodotus regarding his “father of history” status as a point of departure, Wu, a professor of history now at Fudan University in Shanghai where Geng and Zhang both worked before, offers her defense of Herodotus as a bona fide historian. She acknowledges the value of recent scholarship on Herodotus, as it offers a much more in-depth analysis of the cultural “context” in which Herodotus worked on his Histories. Meanwhile, she emphasizes that while he inherited the genre of Historia from earlier Greek writers, Herodotus made a great improvement on it in his writing. “Although the “historia” method was not his original invention,” Wu argues, “nor did he elevate it into a theoretical or systematic proof, he [Herodotus] did nonetheless make it the most important method of narration. Since Herodotus, everyone who studies past events in human history and everyone who studies changes in society all add their own judgments and interpretations.” By and large, Wu champions the view advanced by such historians as Arnaldo Momigliano (1908–1987) that modern historiography indeed had “classical foundations.” In her opinion, recent studies of Herodotus in the West have overemphasized Herodotus’ cultural inheritance while overlooking the paradigmatic influence of the Histories in developing European historiography.

Li Longguo contributes the second article to this issue on the transition from ancient to medieval historiography in Europe. A specialist in the history of the Middle Ages at Peking University, where Zhang Zhilian used to teach, Li has made an interesting observation of the transition. As shown by its title, “From ‘Walking’ to ‘Sitting’: Changes in the Practices of Western Historiography From Ancient to Medieval Times,” Li’s article compares the different research styles adopted by ancient and medieval historians. In ancient Greece, he writes, as exemplified by Herodotus and Thucydides, followed also by Xenophon, historical writing was mostly drawn on eyewitness experiences; those Greek historians usually collected information for their writings by personally traveling to the places where historical events had taken place. By comparison, Roman historians like Livy and Tacitus began to use materials already collected in the imperial library; they no longer “walked” as much as their Greek predecessors had. Then in the Middle Ages, historical records were mostly produced by Christian monks who tended to lead a solitary and sedentary life in the monastery. That is, they seldom “walked” to gather source materials but instead they “sat” in the library where they went through its source collections for their writing. This evolution of research style, Li opines, also unveiled a change in epistemology: ancient historians “walked” to locate the sources for ensuring their factuality whereas medieval historians believed that their religious faith could guarantee the truthfulness of their records.

The third article is written by Zhang Yibo, a Ph.D. candidate in the History Department of Peking University. His research focuses on a key moment in the development of European historiography into the modern age. In the so-called “Age of Discovery” of European history, Zhang finds, the tradition of universal-history writing experienced a notable change—after discovering the Americas, European historians embarked on the task of expanding their horizons in perceiving the world. The multivolume Universal History, compiled chiefly by George Sale (1697–1736) but assisted by many others, was a prime example. Appearing in the mid-eighteenth century, Zhang finds, this massive book of sixty-five volumes contained many fresh ideas that were unseen before. However, no sooner had it become a commercial success than it received harsh criticisms, for, in the eyes of the historians who then already aspired to turn history into a science, such as August Ludwig Schözer (1735–1809), Sale’s work was a mere assemblage of unscrutinized materials, lacking the commitment for ascertaining their credibility. Consequently, in Zhang’s words, “the kind of encyclopedic history writing model represented by Sale’s Universal History was a tradition that gradually disappeared following the professionalization and scientificization of historiography.” His study thus offers a specific case that documented the transformation of modern European historiography.

In developing scientific historiography in Europe, German historian Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886) evidently played an instrumental role, well recognized by many experts in the West. Over the centuries, a great number of works have been published on Ranke and his influence as the “father of modern scientific historiography.” In his article, “Equal Emphasis on ‘Research’ and ‘Representation’: A New Analysis of Ranke’s Debut Work,” Lü Heying, who teaches at Sichuan University, offers a close-up examination of Ranke’s two Prefaces to the First Edition of the Geschichten der Romanischen und Germanischen Völker von 1494 bis 1515 (Histories of the Latin and Teutonic Peoples from 1494–1514). The Prefaces are important because in which Ranke declared that while previous historians sought in history political idealism and moral didacticism, his writing of the book was merely for telling history “wie es eigentlich gewesen,” or “as how it actually was.” Engaging critically with some of the recent Western publications, such as that by J.D. Braw and Jörn Rüsen in History and Theory,6 Lü argues that for a better understanding Ranke’s well-known statement, one needs to conduct an in-depth reading and textual analysis of the two Prefaces as well as the appendix to the work, Zur Kritik Neuerer Geschichtschreiber (Criticisms of modern historians). He believes that all of them holistically as an organic system that addresses not only what Ranke desired to accomplish in his writing but also how he devised his research method and his style of presentation.

Li Hongtu, our fifth contributor, is a professor of European intellectual history at Fudan University where Lü Heying received his Ph.D. In recent years, Li has published extensively on the modern, postwar trends of intellectual history, centering around the works of Quentin Skinner and Reinhart Koselleck (1923–2006). In this article, he traces the origin of the history of ideas as defined and advanced by Arthur O. Lovejoy (1873–1962) in the prewar period and proceeds to discuss the vicissitudes of its change from the second half of the twentieth century. He notes that the changes stemmed from a wide range of new interests among the practitioners. Due to the “linguistic turn,” intellectual historians developed a focus on context, rhetoric, actions, etc., whereas the growing influence of sociocultural history also prompted them to look into the relationship between ideas and social contexts. Last but not least, echoing the march of globalization, the “spatial turn” has now emerged in the field as well. As a result, Li believes, there is no decline of the history of ideas as a field, but historians have since expanded its boundary and enriched its research paradigms. He himself points out a few cases that call for historians, Western and Chinese alike, to note how the intellectual variances in China could help produce new and different understandings of certain well-received concepts in the field.

The sixth article is written by Huang Yanhong who, after obtaining his Ph.D. from Peking University, worked at the World History Institute of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences for over a decade. He is now a professor of European history at Shanghai Normal University. Having commanded several European languages and translated a number of works from French, English and German into Chinese, Huang has also written extensively on modern historiography and intellectual history in Europe. In this article, he offers a detailed analysis of Pierre Nora’s “Lieux de Mémoire” concept and project and their international influence. His aim is to explore the transformation of historical consciousness and historical writing in postwar France. Nora’s introduction of the project, which incidentally has been translated into Chinese at present,7 according to Huang, reflected the changing intellectual milieu, which gave rise not only to New National History, but also to the idea of “presentism” (présentisme). As such, Huang maintains, while Nora’s project (as he himself admitted) was specific to France, it has far-reaching implications for contemporary historiography in both Europe and beyond.

Zhang Guangzhi, mentioned earlier, provides the seventh and last article for this issue. A professor emeritus of history at Fudan University, where he spent his entire career of over forty years, Zhang is a well-known expert on Western historiography in China. Over the decades, he has trained a number of students in the field, many of whom have also become established scholars (e.g., Wu Xiaoqun). In writing this review article, Zhang observes that the development of the Chinese study of Western historiography went through three major periods in the twentieth century and the progress in the third period, beginning from the late 1970s after China was ushered in the “Reform and Open-up” era, has been most impressive. And, as I point out at the beginning of this introduction, this trend of growth will likely continue in the years to come.

All in all, I believe, editing this issue can help our readers to see the other side of the recent and robust globalization of history writing—as historians in the West are searching for ways to expand their research horizons, their counterparts in the other hemisphere have also been working on enhancing their knowledge of Western history and historiography. In his thought-provoking work, Global Perspectives on Global History, Dominic Sachsenmaier, a noted global historian at the University of Göttingen who serves on our editorial board, observes sharply that for the future expansion of global history, it is necessary for Western historians to diversify their outlooks and augment their knowledge base. For “much of global history in Europe and North America,” he aptly notes, “remained more characterized by a rising interest in scholarship about the world rather than scholarship in the world” (italics original).8 While a rather small step, I hope this issue will make a contribution to reaching this goal by stimulating more interest among our readers in Chinese scholarship on the West and the world.

Notes

1 Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 8, 28.

2 Georg Iggers, Q. Edward Wang and Supriya Mukherjee, A Global History of Modern Historiography (London: Routledge, 2017), 312.

3 Ge Zhaoguang, “The Evolution of World Consciousness in Traditional Chinese Historiography,” a keynote speech delivered at the international symposium on “The Conceptions of the World in Twentieth-century China” at the University of Göttingen on October 26, 2017. See also his What Is China? Territory, Ethnicity, Culture, and History, trans. Michael Gibbs Hill (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2018); and Q. Edward Wang, “History, Space and Ethnicity: The Chinese Worldview,” Journal of World History, 10, no. 2 (Sept. 1999), 285–305.

4 For a general discussion of the origin of modern Chinese historiography and its connection with the West, see Q. Edward Wang, Inventing China through History: The May Fourth Approach to Historiography (Albany: SUNY Press, 2001).

5 Besides Zhang Guangzhi’s article in this issue, Chen Heng also discusses the development of the history of Western historiography in his “Xifang shixueshi de dansheng, fazhan jiqi zai Zhongguo de jieshou” (The Origin and development of the history of Western historiography and its acceptance in China), Shixueshi yanjiu (Journal of historiography), 2 (2016), 56–66. For a discussion in English, see Qingjia Wang, “Western Historiography in the People's Republic of China (1949-to the present),” Storia della Storiografia [History of Historiography], 19 (1991), 23–46.

6 J. D. Braw, “Vision as Revision: Ranke and the Beginning of Modern History,” History and Theory 46, no. 4 (2007), 45–60.

7 Sun Jiang, a professor of history at Nanjing University, is in charge of the translation project, which is expected to complete in 2021.

8 Dominic Sachsenmaier, Global Perspectives on Global History: Theories and Approaches in a Connected World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 4. Also, Sven Beckert and Dominic Sachsenmaier, eds., Global History, Globally: Research and Practice around the World (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018).

Source: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00094633.2020.1743162?src=recsys

Introduction to “History of Western historiography: The views from China”, in Chinese Studies in History, Volume 53, Issue 2 (2020), Routledge

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey. I haven’t been here for a while. Almost for about half a year, I think. I’m sorry. My mental health hasn’t been very well since sometime around late last year, as well as my physical health. I’m sorry for disappearing for a while. I’ve been having lots of physical pain and d/ental pain since late last year, around the holidays. I had lots of appointments for d/octors and d/entists and such throughout early this year during winter. After that though, I was still in pain, I went back to my d/entist and they said that I had to go see a specialist. I went to see one, had to go to a big hospital, and I was diagnosed with a muscular joint issue which affects the face and mouth. I have to live with it, unfornately, but my specialist said that there’s ways to treat it, like to help ease the pain. Also I have to go through a clea/ning next month, and I’m a bit worried, cause my mouth, jaw, and t/eeth are usually always in pain, and my t/eeth are sensitive due to my joint issues. I would like to get it worked though, cause I drink coffee and tea often, and I have some v/isible stains that are quite hard to clean. I have been having anxiety and been worrying a lot about my t/eeth and bones and such ever since I have been diagnosed with this issue. I can hardly eat these days and sometimes it’s hard to open my mouth too wide. I may also have a nerve issue but I need to go to a certain d/octor for that.

Now days, I have been trying to avoid getting too worked up. I get stressed easily and upset easily. I was diagnosed with emotional disorder when I was very young, so I cry easily and such. I’m also autistic. I get a bit overwhelmed at times and I let stuff get to me. I got upset a while back, cause I was treated like a k/id, and I personally don’t like that too much, cause I’m an adult. I don’t mind being called a ‘k/id’, by much older adults though. I just don’t really like being treated like one. I do a lot though cause of the way I act, and the stuff I like, and there’s s/imple things I don’t understand at times. I got a bit upset, and it made my face and jaw hurt a lot. Once I calmed down and had some soup, it settled, though. I feel like when I eat or drink something warm, it helps eases the p/ain a bit.

My specialist said that I should wear a mouth g/aurd. I tried, but the instructions were hard for me to understand. I tried a bunch of p/ain r/elievers but they didn’t really do much. My specialist p/rescribed me some rexlaxers and they help, and make me sleep, lol. But I have to eat cause sometimes they make me get sick. The last time I went was about a month ago, and they said they wish there was something they could do, but they said I have to go to a different d/octor that specializes in what I have. It’s hard to find one that will ac/cept me. I might have to go to one in the b/igger c/ity somewhere. Also a while after that, I had to stay in my h/ouse for about a week cause one of my family members got s/ick. They are okay now and fully recovered, which is good, cause I was worried. My b/rother gets sick easily and has been sick when he was growing up, so I was worried about him a lot. I’m glad he’s okay.

So, yeah. I have been going through quite a lot since around the holidays late last year. However, some good things have happend though. My b/rother’s partner adopted a kitten. That and I was a top ra/nk score during an in game e/vent in one of the games I play. I got a t/100 t/itle, which I thought was pretty cool. It made me kinda happy, since I usually don’t really achieve anything. I k/now it’s not much, but as a fan it made me happy. I’m also not very good at games, lol. I also got a few plushies of a character I like. The plushies hasn’t been in the mail yet, but I’m patiently waiting for them to arrive. I also want to cosplay as my favorite character again this year for fall. I haven’t got the costume yet, but I will soon.

I’m a bit nervous about my next appointment at the d/entist for cleaning, but maybe I’ll be alright. A part of me says I will. I’ve been a bit worried about it that I get b/ad dreams sometimes and I fi/nd it hard to sleep.

So, that’s what’s been happening. Sorry, for not being here for about h/alf a y/ear.

#personal#long post#also another game i got t/300 which was pretty cool too#so yeah this m/uscle j/oint issue is hard to live with#it s kinda hard to talk too much so i try not to#also i have to eat soft foods and such#i usually just eat ramen soup these days and banana#my brothers partners cat is adorable#my brother says that he will try and talk back to you like he meows after you say something to him#i usually see him through video chat since my brother usually lives with his partner and stays here during the weekend and days off#he works in the b/ig c/ity#he shows me the cat during video chat the cat is adorable#my aunt has the same joint issue and she said it will be okay and gave me some advice#i actually have been having signs of the joint issue since i was in junior high#however it didn't cause p/ain i just had a clicking noise around my jaw when i walked and it would stop after a while#though i guess since im much older now it s starting to get w/orse#sorry for all the tags#might reblog this later#if you read all this than yay heres a cookie x p

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

thought enstars was a silly little game until december when i stubbled upon a t/igger warning list for the game,,,,thought it was just a silly little game full of gay people and their token straight friends

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haters Are Dumb As Fuck

What feminism fails to apprehend is that you cannot hate men without hating women. We are one species and hatred for such a massive part of it translates 100% of the time into pure misanthropy.

Same as racism actually. It undergoes metamorphosis into misanthropy. For example the worst racist I knew personally hated fucking everyone but other racists with the same prejudices, and his justification was that we were all "A bunch of stupid n*igger-lovers".

That fucking loser had like two people he could tolerate because his loathing spread to nearly everyone he knew and radfems are no different.

Anyone who won't join in with their endless tarring and feathering of men as a class is an enemy and will eventually become a target of their hate, as I am sure many of you know from the personal experience of being called a "handmaiden" by some idiot who refused to hear any of your ideas or reasoning.

This will likely work with any class hatred, as everyone who is neither in said class nor that's class's enemy will be seen as the enemy's friend by the hater.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

โบนัสการเล่นสล็อต Jay Simpson ที่คาสิโนใดมีมากที่สุด?

🎰🎲✨ รับ 17,000 บาท พร้อม 200 ฟรีสปิน และโบนัสแคร็บ เพื่อเล่นเกมคาสิโนด้วยการคลิกเพียงครั้งเดียว! ✨🎲🎰

โบนัสการเล่นสล็อต Jay Simpson ที่คาสิโนใดมีมากที่สุด?

ข่าวดีสำหรับท่านที่ชื่นชอบการเล่นสล็อตออนไลน์! Jay Simpson เป็นเว็บไซต์ที่ให้บริการเกมสล็อตที่น่าตื่นเต้นและมีโบนัสที่น่าทึ่ง โบนัสสล็อต Jay Simpson เป็นที่รู้จักในวงการการพนันออนไลน์ว่าเป็นเว็บไซต์ที่มีการแจกโบนัสที่ท้าทายและมีความมั่นคง ทำให้นักพนันหลายคนเลือกเล่นกับเว็บไซต์นี้

โบนัสสล็อต Jay Simpson มีความหลากหลายของเกมสล็อตที่มีกราฟิกสวยงามและเสียงเพลงที่น่าทึ่ง นอกจากนั้นยังมีการแจกโบนัสที่มากมายที่ช่วยเพิ่มโอกาสในการชนะโบนัสใหญ่ กับการบริการที่ดีและทีมงานที่พร้อมให้บริการตลอด 24 ชั่วโมง ทำให้นักพนันสามารถเล่นและสนุกได้ตลอดเวลา

นอกจากนี้ยังมีโปรโมชั่นและโบนัสพิเศษที่รองรับทุกความต้องการของลูกค้า ทำให้ Jay Simpson เป็นเว็บไซต์ที่เหมาะสำหรับนักพนันทุกคน ไม่ว่าจะเป็นนักพนันมือใหม่หรือนักพนันที่มีประสบการณ์มากๆ ท่านสามารถเข้ามาเล่นและชนะได้โบนัสที่มากมายได้ที่ Jay Simpson ลองเข้าไปสัมผัสความสนุกสุดพิเศษกันได้เลย!

ปัจจุบันมีเกมสล็อต Jay Simpson ที่เป็นที่นิยมในคาสิโนออนไลน์เป็นอย่างมาก เกมนี้ถูกออกแบบมาเพื่อผู้เล่นที่รักการพนันและกีฬาฟุตบอลพรีเมียร์ลีก โดยมีตัวละคร Jay Simpson เป็นตัวการที่ผู้เล่นจะได้พบในเกม โดยมีกราฟิกที่สวยงามและเสียงที่ดีที่ช่วยให้ประสบการณ์การเล่นของคุณมีความสนุกสนานขึ้น

การเล่นสล็อต Jay Simpson ไม่ค่อยยาก เพียงแค่คุณต้องการมีความคุ้นเคยกับกฎและวิธีการเล่นเบื้องต้น ปุ่มจะช่วยคุณในการเลือกเงินเดิมพันและแตกต่างกันตามระดับความเสี่ยงที่คุณต้องการ หากคุณสามารถหมุนวงล้อให้เหมาะสม คุณอาจจะสามารถรับรางวัลและโบนัสมากมายได้

สล็อต Jay Simpson เป็นเกมที่มีความสนุกสนานและน่าตื่นเต้น ไม่ว่าคุณจะเป็นผู้เล่นที่เพิ่งเริ่มต้นหรือมีประสบการณ์มาก่อน คุณก็สามารถเพลิดเพลินกับเกมนี้อย่างมีความสุข อย่ารอช้าที่จะลองเล่นสล็อต Jay Simpson ในคาสิโนออนไลน์และรับประสบการณ์ที่ไม่เหมือนใครไปเลย สนุกและมีโอกาสได้รับรางวัลใหญ่ในที่สุด!

ในโลกของการพนันออนไลน์, การเล่นสล็อตเป็นหนึ่งในเกมที่มีความนิยมและมีโอกาสได้รับโบนัสมากมายสำหรับผู้เล่น โบนัสการเล่นสล็อตเป็นวิธีที่ผู้เล่นสามารถเพิ่มโอกาสในการชนะและเพิ่มความสนุกสนานในการเล่นเกมอีกด้วย

โบนัสการเล่นสล็อตมักประกอบด้วยโอกาสในการตigger ร��บโบนัสสุดพิเศษและโอกาสในการรับเงินรางวัลโบนัสจากสล็อตเกม นอกจากนี้, บางครั้งยังมีโบนัสที่เป็นเงินสดหรือเครดิตฟรีที่ผู้เล่นสามารถใช้ในการเดิมพันเพิ่มเติม

เมื่อคุณรับโบนัสการเล่นสล็อต, ควรอ่านเงื่อนไขและข้อกำหนดของโบนัสอย่างระมัดระวัง เพื่อให้แน่ใจว่าคุณสามารถใช้โบนัสได้อย่างเต็มประสิทธิภาพและไม่มีปัญหาใดๆในการถอนเงินรางวัลที่คุณได้รับ

ในการเล่นสล็อตและใช้โบนัส, ควรจำไว้ว่าการพนันคือกิจกรรมที่ต้องรับผิดชอบในทุกขั้นตอน ควรเล่นอย่างรับผิดชอบและไม่เสียหายตนเองด้วยการเดิมพันเกินจน การเล่นสล็อตนอกเหนือจากความสนุกและความสนุกยังเป็นการแสวงหาโอกาสในการชนะเงินรางวัลที่มีรางวัลให้ ไม่ควรลืมว่าการพนันสมัครเล่นสล็อตเป็นเพียงเกมโอกาสและไม่ควรถือเป็นวิธีการทำเงินหลัก.

ด้วยโบนัสการเล่นสล็อต, ผู้เล่นสามารถเพิ่มโอกาสในการชนะและเพิ่มความสนุกสนานในการเล่นเกมอีกด้วย อย่าพลาดโอกาสในการรับโบนัสเมื่อเล่นสล็อตในเว็บไซต์การพนันที่น่าเชื่อถือ.

"Jay Simpson อยู่ในรายการบุคคลที่มีชื่อเสียงที่เข้าร่วมกิจกรรมในโรงเรียนสมุยคาสิโนเป็นสิ่งที่ผู้คนต่างตามหา ไม่ว่าจะเป็นการเล่นเกมโป๊กเกอร์ บล็อกแจ๊ค หรือหนุ่มน้อยที่มีพื้นฐานทางด้านเทคโนโลยี ที่สามารถช่วยให้กิจกรรมการเล่นพนันมีประสิทธิภาพมากขึ้นในระยะระยะยาว โดย Jay Simpson ได้ร่วมงานปีที่แล้วและได้รับความนิยมอย่างกว้างขวางจากผู้เข้าชมทั่วไป มีความสามารถในการทำให้ผู้คนตกหลุมรักในเกมเพลย์ของเขา และเป็นหนึ่งในประภาพคนที่จำเป็นในสมุยคาสิโน"

"การมี Jay Simpson ร่วมงานนั้นเป็นประโยชน์ต่อการเจรจาธุรกิจของคาสิโน เพราะความสามารถในการสร้างบรรยากาศที่น่าตื่นเต้นและยังสามารถเสริมสร้างภาพลักษณ์ของคาสิโนได้อย่างมีประสิทธิภาพ ด้วยการกล่าวถึงการแข่งขันในโต๊ะเดียวกันง่ายๆ หรือการเล่นเกมยิงปืนเพื่อเล่นรางวัล ซึ่งทำให้ผู้เล่นต่างสนุกกับการชมเกมของ Jay Simpson และแสดงความพอใจในคาสิโนสมุยเป็นที่สวยงามอย่างชัดเจน"

"ด้วยความที่ Jay Simpson มีความเป็นดารัรรย์และมีประสิทธิภาพสูง ทำให้เขากลายเป็นบุคคลสำคัญที่ไม่สามารถขาดหายได้ในกิจกรรมในคาสิโนสมุย ซึ่งจะช่วยส่งเสริมธุรกิจและสร้างพฤติกรรมที่ดีในชุมชนโรงเรียนคาสิโนที่สำคัญ"

ในโลกของการพนันอีกหนึ่งแนวคิดที่น่าสนใจคือคาสิโนที่มีโบนัสมากที่สุด การเล่นพนันในคาสิโนออนไลน์ที่มีโบนัสสูงสุดเป็นวิธีที่น่าสนใจในการเพลิดเพลินและได้รับประสบการณ์ที่ไม่เหมือนใคร นี่คือรายชื่อ 5 คาสิโนที่มีโบนัสมากที่สุดที่คุณอาจสนใจ:

คาสิโนออนไลน์ ชื่อของคาสิโนขีดเลือกในตอนนี้เน้นถึงการให้บริการที่เป็นเลิฟสุด ๆ และโบนัสจากช่วงเวลาที่ไม่มีที่ใดเหมือนทำให้กลุ่มคนรักการเล่นคาสิโนหลงใหลกับโบนัสเหล่านี้

คาสิโนออนไลน์ เป็นคาสิโนที่เน้นพัฒนาเกมใหม่ ๆ และมั่นคงในการให้บริการที่รวดเร็ว ทำให้ดีที่สุดเกี่ยวกับโบนัสที่มีดาวน์โหลด

คาสิโนออนไลน์ ให้ความสำคัญกับความปลอดภัยและความสนุกสุดซึ้ง มีโบนัสที่มากและง่ายต่อการเข้าถึง ทำให้เป็นที่รู้จักดีมาก

คาสิโนออนไลน์ ชิลเล็กๆ นี้เอาใจประเพณีเกมที่น่าสนใจและสนุกสุดขีด มีโบนัสสุดอุ่นที่คุณจะได้รับได้ง่าย

คาสิโนออนไลน์ บริการดี ๆ และโบนัสดี ๆ เป็นจุดอ่อนของคาสิโนเหตุผลนี้ทำให้มันเป็นหนึ่งในคาสิโนที่ได้รับชื่อเสียงด้านโบนัสที่ดีที่สุดและมีลูกค้ามากที่สุด

อย่าลืมตรวจสอบข้อกำหนดและเงื่อนไขของโบนัสก่อนที่จะลงทุนกับเว็บไซต์การพนันใด ๆ เพื่อให้แน่ใจว่าคุณเข้าใจเงื่อนไขและสามารถถอนเงินได้โดยง่ายและรวดเ

0 notes

Text

@wired @radioshack @cnet @techpowerup @electronicsrepa irschool @learnelectronicsrepair @northridgefix @pcwelt @debian

an ic does not tr igger the initial mosfets

and that ic

can onlybe the po werdistributionchip andor

the batterycontroller andor th e superio

these

else allis ok

no shorts findable

but w ithout the initial mosfets triggered on

and likely from a power initial ic that requir es powergood signals or such to superio too

is the stall

@wired @radioshack @cnet @techpowerup @electronicsrepairschool @learnelectronicsrepair @northridgefix @pcwelt @debian

an ic does not trigger the initial mosfets

and that ic

can onlybe the powerdistributionchip andor

the batterycontroller andor the superio

these

else allis ok

no shorts findable

but without the initial mosfets triggered on

and likely from a power initial ic that requires powergood…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

I think when citing sources I think we should put "thank you" in the beginning. For instance

Thank you Fairclough, N. (1989). Language and Power. Longman.

Thank you Iggers, J. (2018). Good News, Bad News. Routledge.

Thank you Fishman, M. (1980). Manufacturing the News. University of Texas Press.

It's only polite. I think

0 notes