#manuscript facsimiles

Text

Typography Tuesday

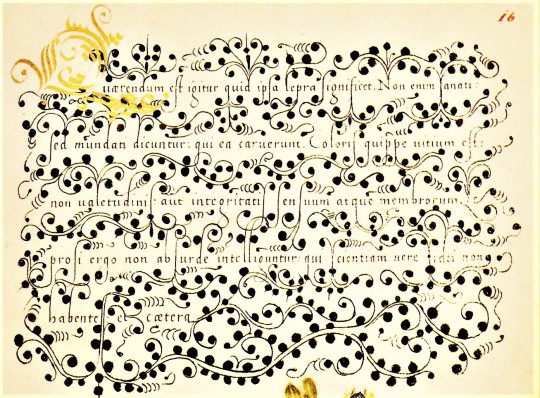

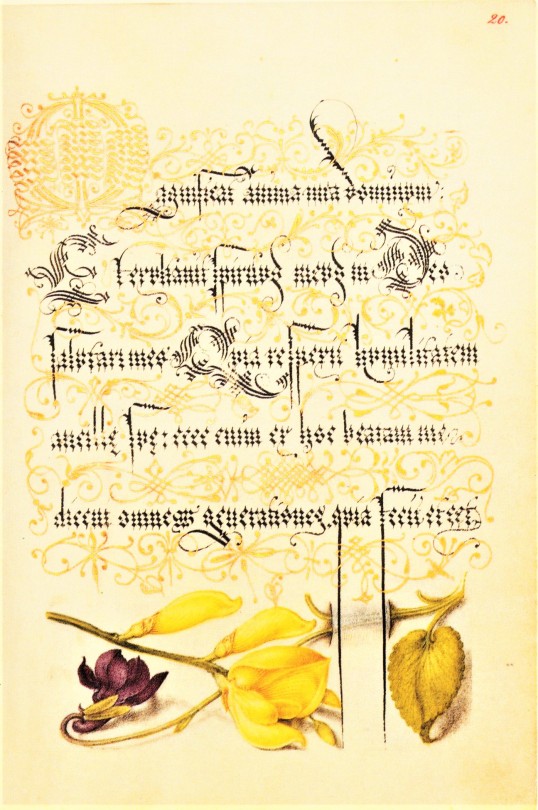

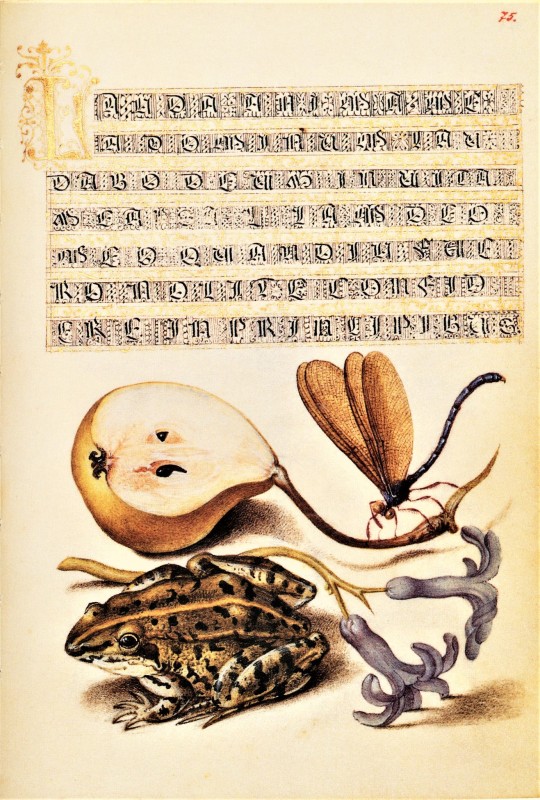

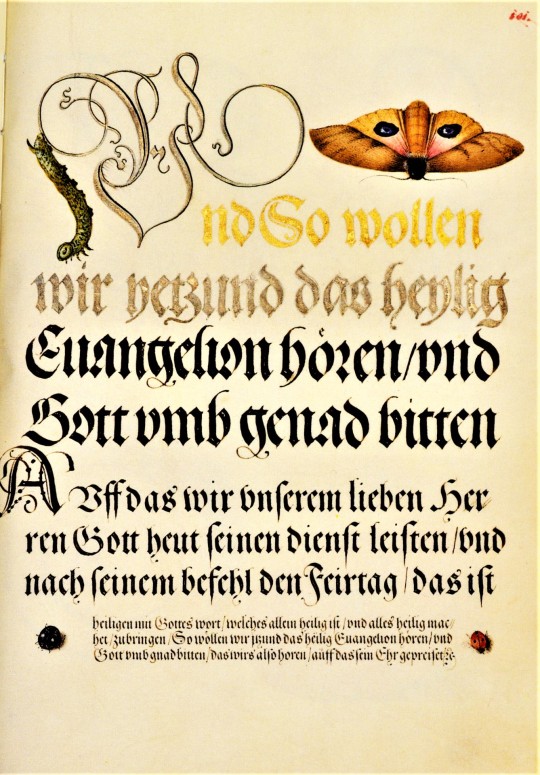

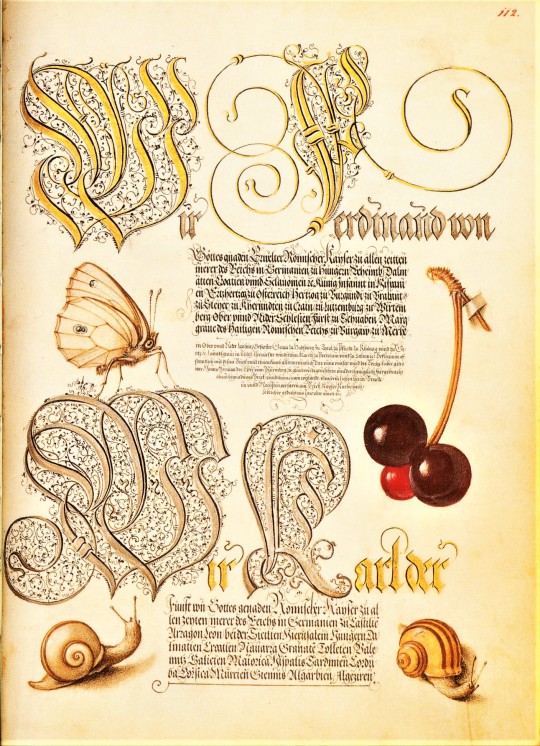

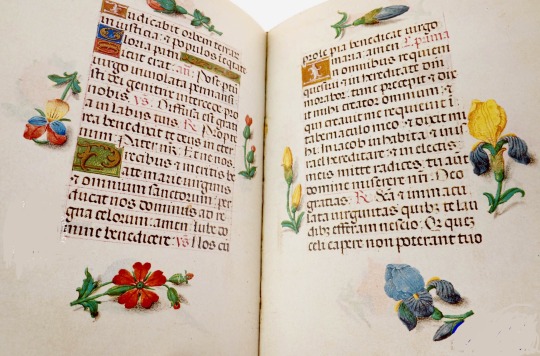

We return to our facsimile of a 16th-cnetury calligraphic manuscript, Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta, or Model Book of Calligraphy, written in 1561/62 by Georg Bocskay, the Croatian-born court secretary to the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I, and illuminated 30 years later by Flemish painter Joris Hoefnagel for the grandson of Ferdinand I, Emperor Rudolph II. The manuscript was produced by Bocskay in Vienna to demonstrate his technical mastery of the immense range of writing styles known to him. To complement and augment Bocskay's calligraphy, Hoefnagel added fruit, flowers, and insects to nearly every page, composing them so as to enhance the unity and balance of the page’s design. Although the two never met, the manuscript has an uncanny quality of collaboration about it.

Our facsimile was the first facsimile produced from the collection at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. It was printed in Lausanne, Switzerland by Imprimeries Reunies and published by Christopher Hudson in 1992.

View another post from Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta,

View more Typography Tuesday posts.

#Typography Tuesday#typetuesday#Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta#or Model Book of Calligraphy#Georg Bocskay#Joris Hoefnagel#illuminated manuscripts#manuscripts#manuscript facsimiles#facsimiles#calligraphy#letter forms#letters#J. Paul Getty Museum#Imprimeries Reunies#Christopher Hudson#Ferdinand I#Rudolph II

827 notes

·

View notes

Text

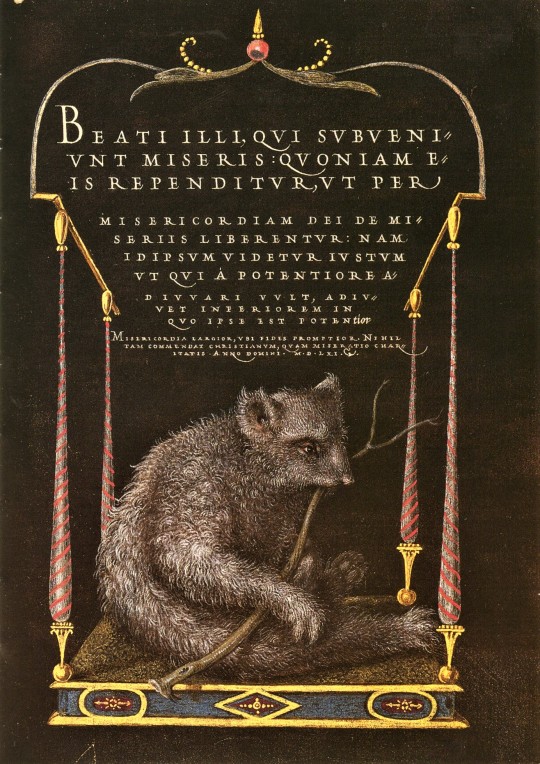

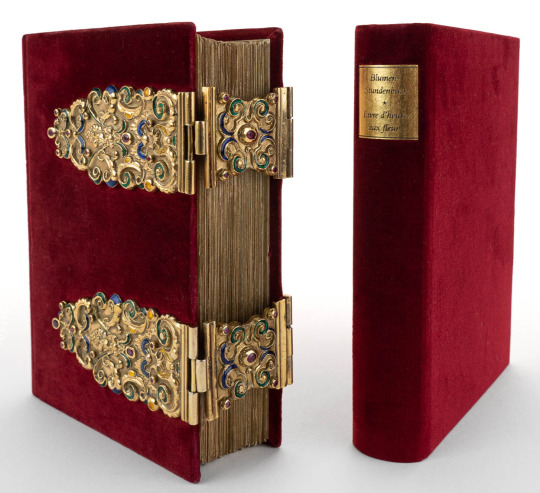

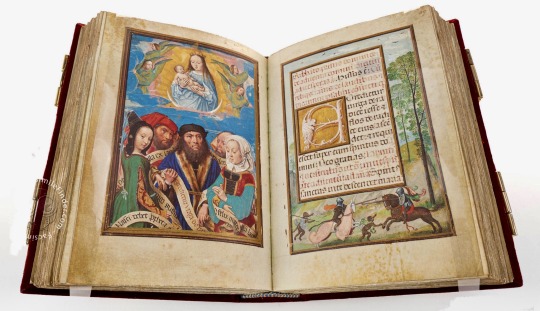

THE FLOWERS BOOK OF HOURS (aka LIVRE D’HEURES AUX FLEURS). (Ghent or Bruges: 1520-1525) Illuminated by Simon Bening.

The oversized clasps contain 64 gems and inlays on the front and 63 on the back. The book features a vivid palette and generous gold highlights. There are 16 full-page miniatures by Bening, one of the prime European artists of the 16th Century.

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#illustrated book#illuminated manuscript#facsimile#book binding#treasure bindings#book of hours

504 notes

·

View notes

Text

A new video facsimile! Ms. Codex 1640 is too tightly bound to be photographed in our studio, but we can take a video to give you a sense of the whole book. It's a 14th c. copy of Thomas of Ireland's Manipulus Florum, cover-to-cover, sped x20

On YouTube:

#medieval#manuscript#video#video facsimile#14th century#thomas of ireland#extracts#england#france#book history#rare books

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

My portfolio

#artwork#art#small artist#portfolio#school work#my art#stained glass#watercolor#oil painting#dry pastel#charcoal#book binding#own design#my artwork#illuminated manuscript#my portfolio#portrait#facsimile#inventive#edgar degas#oil on canvas#alfons mucha#still life#tempera painting

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

speccoll problems: when your department has been given the special collections exhibit case over Christmas on the strength of the exhibit you personally designed last Christmas, and you (personally) have been asked to put together the one for this year as well but you already used the best possible item last year

#i need to get something together by friday#idk what else we have that's christmassy#(we're a jesuit school they expect it)#we have a facsimile of the sir gawain and the green knight manuscript#but the trouble with that one is#it's very small#and rather grubby#the literary value of the original is of course beyond measure#but its visual appeal is not necessarily apparent to the uninitiated#also i don't think my supervisor wants me to use it for that reason#(i had originally floated it last year and he was not enthusiastic)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tulips

The tulips are too excitable, it is winter here.

Look how white everything is, how quiet, how snowed-in.

I am learning peacefulness, lying by myself quietly

As the light lies on these white walls, this bed, these hands.

I am nobody; I have nothing to do with explosions.

I have given my name and my day-clothes up to the nurses

And my history to the anesthetist and my body to surgeons.

They have propped my head between the pillow and the sheet-cuff

Like an eye between two white lids that will not shut.

Stupid pupil, it has to take everything in.

The nurses pass and pass, they are no trouble,

They pass the way gulls pass inland in their white caps,

Doing things with their hands, one just the same as another,

So it is impossible to tell how many there are.

My body is a pebble to them, they tend it as water

Tends to the pebbles it must run over, smoothing them gently.

They bring me numbness in their bright needles, they bring me sleep.

Now I have lost myself I am sick of baggage—

My patent leather overnight case like a black pillbox,

My husband and child smiling out of the family photo;

Their smiles catch onto my skin, little smiling hooks.

I have let things slip, a thirty-year-old cargo boat

Stubbornly hanging on to my name and address.

They have swabbed me clear of my loving associations.

Scared and bare on the green plastic-pillowed trolley

I watched my teaset, my bureaus of linen, my books

Sink out of sight, and the water went over my head.

I am a nun now, I have never been so pure.

I didn’t want any flowers, I only wanted

To lie with my hands turned up and be utterly empty.

How free it is, you have no idea how free—

The peacefulness is so big it dazes you,

And it asks nothing, a name tag, a few trinkets.

It is what the dead close on, finally; I imagine them

Shutting their mouths on it, like a Communion tablet.

The tulips are too red in the first place, they hurt me.

Even through the gift paper I could hear them breathe

Lightly, through their white swaddlings, like an awful baby.

Their redness talks to my wound, it corresponds.

They are subtle: they seem to float, though they weigh me down,

Upsetting me with their sudden tongues and their color,

A dozen red lead sinkers round my neck.

Nobody watched me before, now I am watched.

The tulips turn to me, and the window behind me

Where once a day the light slowly widens and slowly thins,

And I see myself, flat, ridiculous, a cut-paper shadow

Between the eye of the sun and the eyes of the tulips,

And I have no face, I have wanted to efface myself.

The vivid tulips eat my oxygen.

Before they came the air was calm enough,

Coming and going, breath by breath, without any fuss.

Then the tulips filled it up like a loud noise.

Now the air snags and eddies round them the way a river

Snags and eddies round a sunken rust-red engine.

They concentrate my attention, that was happy

Playing and resting without committing itself.

The walls, also, seem to be warming themselves.

The tulips should be behind bars like dangerous animals;

They are opening like the mouth of some great African cat,

And I am aware of my heart: it opens and closes

Its bowl of red blooms out of sheer love of me.

The water I taste is warm and salt, like the sea,

And comes from a country far away as health.

Sylvia Plath, Ariel: The Restored Edition: A Facsimile of Plath’s Manuscript, Reinstating Her Original Selection and Arrangement (HarperCollins, 2004)

#sylvia plath#tulips#ariel#ariel: the restored edition#ariel: the restored edition: a facsimile of plath's manuscript reinstating her original selection and arrangement#poetry#hospitals for ts

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

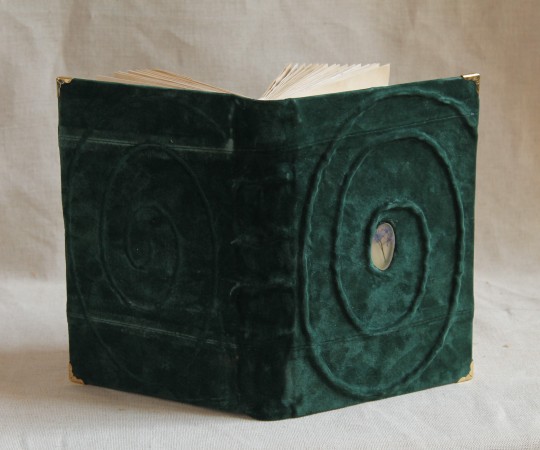

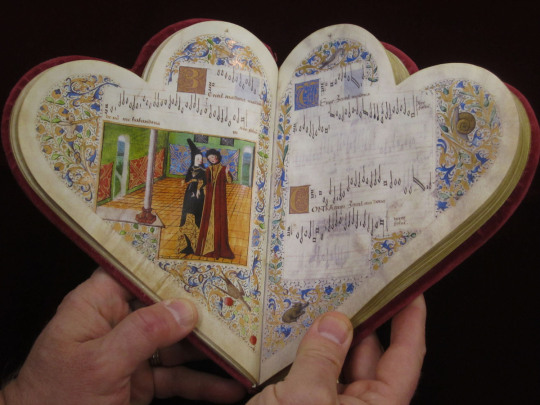

Le Chansonnier Cordiforme, c. 1470, music manuscript

― facsimile by Vicent García Editores of Valencia, Spain

#art history#medieval#medieval art#manuscript#illuminated manuscript#music manuscript#1470s#1470s art#le chansonnier cordiforme#Jean de Montchenu#Bibliothèque de France#Vicent García Editores#ah

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

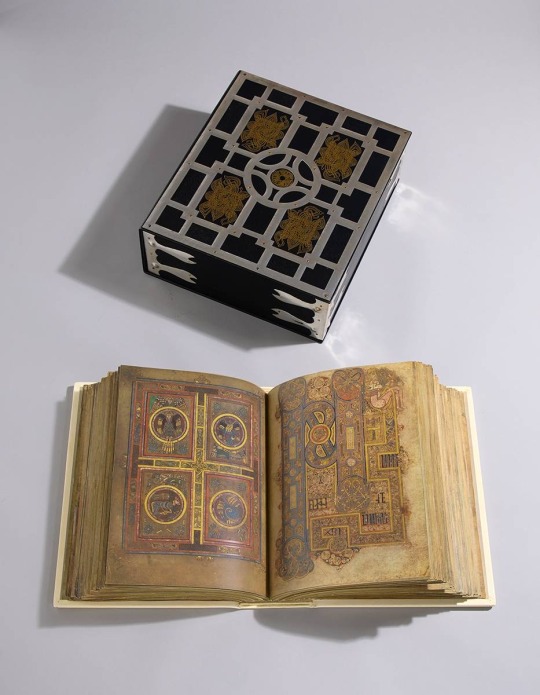

The Book of Kells. A special facsimile.

Faksimile Verlag, Luzern, 1990. The Book of Kells, the most precious illuminated European manuscript of the early Middle Ages, now reproduced, the first and only complete facsimile, published by Authority of the Board of Trinity College, Dublin. Large folio, Luzern 1990, Number 1,304 of 1,480, fine white tawed leather over wooden boards. Contained in a specially created presentation box, the embossed surface with blind & gilt tooled Celtic decoration and silver and brass mounts. Together with a commentary volume with illustrations, 'The Official Guide to The Book of Kells' by Dr Bernard Meehan, former Keeper of Manuscripts at Trinity College, Dublin. A rare opportunity to acquire a complete facsimile of one of the World's greatest Art Treasures.

Whytes

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

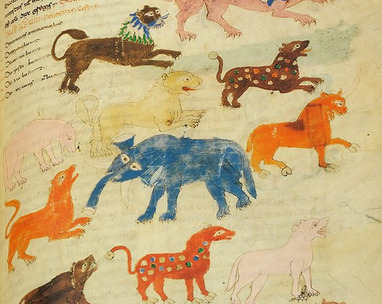

Feeling blue?

1000 years before the blue elephant emoji was added to phones, some Italian monks drew this elephant and friends in a manuscript for Abbot Theobald of Monte Cassino. Monte Cassino was an important monastery and home to St Benedict whose rule is the basis for the Benedictine Order of monks and nuns that still exists today.

This manuscript contains an abbreviation of Hrabanus Maurus's De Rerum Naturis (On the Natures of Things). Hrabanus Maurus (d. 856) was archbishop of Mainz. In addition to encyclodpedia-like works sucha as De Rerum Naturis, he wrote Biblical commentaries, grammars, teaching texts and poems with complex palindromes. He wrote so much that his surviving writings fill about 6 modern type-set volumes.

Materials: parchment, pigments, ink

Contents: Hrabanus Maurus, De Rerum Naturis

Date: 1022-1032

Now Archivio dell'Abbazia, Montecassino, MS 132 (image from a facsimile)

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

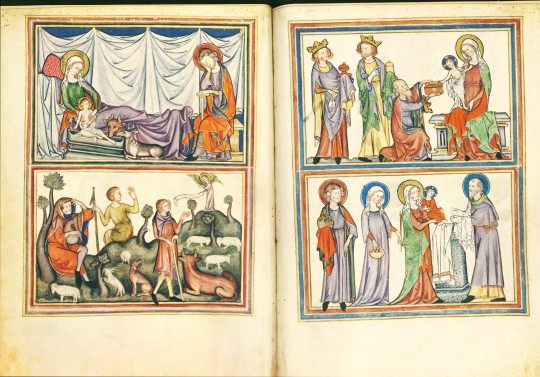

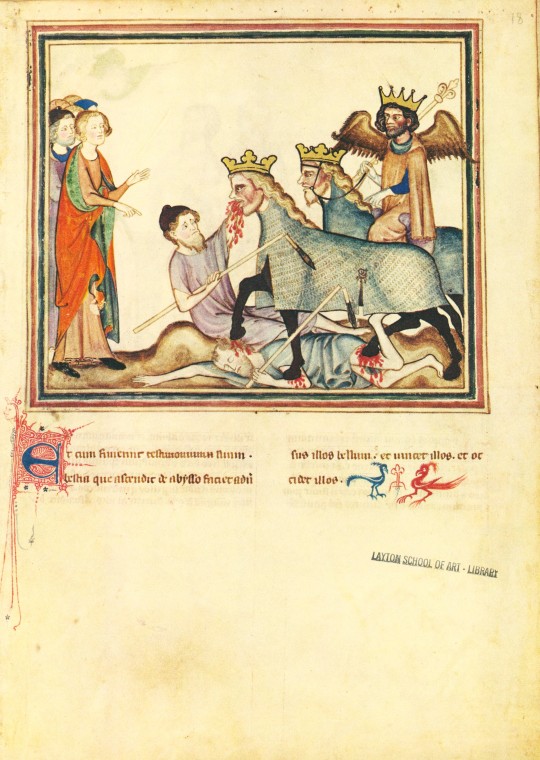

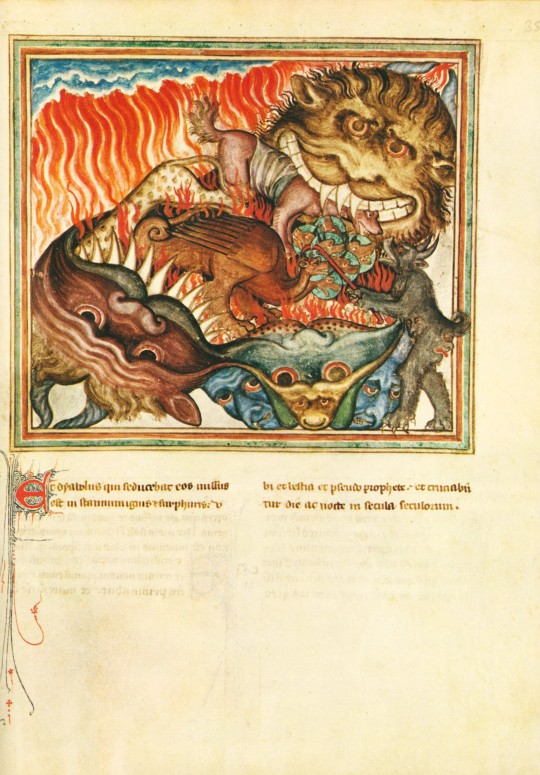

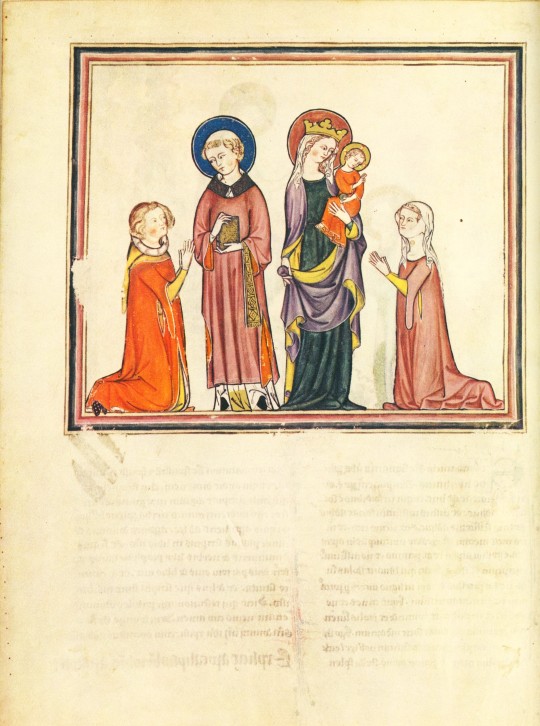

An Apocalyptic Manuscript Monday

This week we present our facsimile of the 14th-century Cloisters Apocalypse, published in 1971 by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. As described in the introduction to the commentary about the manuscript, “[famine], pestilence, strife, and untimely death inspired apocalyptic fantasies and movements in Europe throughout the Middle Ages” (page 9), and this environmental influence led to the popularity of apocalyptic manuscripts like this French Apocalypse. Made in the 1330s for a Norman aristocratic couple, this manuscript has a few interesting details that set it apart from other Apocalypses, especially in relation to two other manuscripts in London (British Library, Add. Ms. 17333) and Paris (Bibliothèque Nationale, ms. Lat. 14410) that share similar formats, styles, and sequences with the Cloisters manuscript.

The first unique detail is the prefatory cycle of the life of Jesus in the introductory folios (1-2 verso). Since the Apocalypse of St. John the Divine (also known as the book of Revelation) was written by a titular St. John, prefatory cycles in Apocalypses usually consist of his life, rather than Christ’s. The other aspect of this manuscript that makes it distinct amongst its sister manuscripts is the addition of a dedication page on folio 38 verso. This page shows a man and woman kneeling in front of a tonsured saint and the Virgin and Child, respectively, representing the people for whom this manuscript was originally made for.

Interestingly, this manuscript also has multiple pages added to the original manuscript. Pasted on the inside front cover are handwritten provenance notes. The manuscript also did not originally include chapters and verses 16:14 through 20:3, and pages with this text were later added to the manuscript after the dedication page.

The materials used to create this manuscript include tempera, gold, silver, and ink on parchment with a later leather binding. If you are interested in seeing this unique Apocalypse manuscript, you can either use our facsimile, visit Gallery 13 of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Cloisters where the original is on display, or view their digital presentation of the manuscript.

View other posts on our facsimiles of illuminated manuscripts.

– Sarah S., Special Collections Graduate Intern

#manuscript monday#apocalypse#cloisters apocalypse#the cloisters#met#the metropolitan museum of art#manuscripts#illuminated manuscripts#french manuscripts#book of revelation#Revelation of St. John#facsimiles#manuscript facsimiles#Sarah S.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

the sun is also a star, p.3.

summary: this is a continuation of the mhin and li necromancy au!!!

notes: 1.3k words, part one + two, necromancy + consequences of that, (light) body horror, obsessive/unhealthy relationships

v. The Mind Forgets but the Body Always Remembers

Everyday, Li’s body falls apart, piece by piece.

The joints are easiest to sew back on, stitching fingers and knees back into their proper position. When the bones fall out of order, it takes them a little longer to reposition them, but it’s still manageable to cut Li’s skin open and slot them back in place. But it’s the other delicate parts, the rotting flesh that they cut out to preserve on ice, the damaged hair that won’t stay put, the fingernails that slide out uselessly, that are harder to fix.

“I’m sorry,” Li tells them every morning, her new greeting for the past few weeks.

“It’s okay,” they tell her curtly. “What happened now?”

And there is always, always a new problem to fix, some part of her body that has forgotten where it should be. Their day is devoted to obsessively cataloging every miscellaneous repair that Li’s body requires. Without their constant vigilance, she’ll fall apart, and the damage will be worse if they’re not there to catch the issues immediately.

When their work bears fruit and her body maintains the semblance of normality again, they run their hands over her body, counting the outline of each bone which protrudes from her skin. 206. 206. 206. All of them in their proper place, in the proper order. Right where they should be.

When they count, Li’s eyes are half-lidded as if she doesn’t know how to close them. She doesn’t need to sleep, not anymore, but Mhin will still tenderly smooth down her eyelids, to grant her the facsimile of rest. And she’ll keep them closed, for an half hour or so, before they begin to drift open again.

Her body is easy to take care of. They know where each muscle and sinew and bone connect. They’ve lovingly outlined a diagram of her body, knowing intimately where each organ is and should be.

Her body is easy, but it’s her mind that’s more difficult to manage. It tumbles away, like a dream slipping through their fingers, and once it goes, it never returns. No, they can’t bring back her lost mind in the same way they can sew her arms into place. There are no manuscripts for that, no matter how obsessively they catalog her body.

The immaterial, the intangible: it’s Mhin’s worst nightmare. There’s no guidelines or charts on how to keep hold of memories, of the electrical impulses in her brain that make her who she is.

“What’s your name?” Mhin asks. It’s a routine integration, but they’ve increased the frequency from once to several times per day.

“Li.”

“What do you know about who you are?”

“I…” she frowns. “I’m…” Her eyes drift vacantly, her hands colder than stone in her lap.

“You’re mine,” Mhin tells her. “And I’m yours. And we’re always going to be together.”

“Mhin,” she says hesitantly.

“Yes.”

“Mhin,” she repeats, mumbling their name as slowly and often as she can, until their name turns to nonsensical ramblings on her tongue.

Mhin lets out a breath. It’ll be okay. If Li forgets, then they’ll remember for her. If Li’s body breaks down, then they’ll repair it. And if Li slips away, they’ll chain her right back down to earth.

They keep the apartment curtains closed, now, to prevent sunlight from leaking in. It ruins Li’s skin, causing it to rot faster. And Li gets clumsy, forgetful, when they’re not around, so it’s easier to stick around by her side instead, to be right there when another piece of her body falls apart. They’ve never much enjoyed the company of others, anyways.

Li sits, more quietly than a doll. She doesn’t move unless they encourage her to, doesn’t speak unless it’s on command. But it’s her. It’s still her. She’s still here, right where they can reach and touch and hold. And that’s enough. It’s what they’ve worked so hard for, to keep her close to them, in any form possible.

Mhin likes to kneel at her feet, with their head in her lap, eyes closed. Like she’s a god, and they’re a dog sleeping by the foot of her shrine. In their small world, the only people who need to exist are the two of them, and no one else.

No matter what it takes. No matter what they have to do, or who tries to get in their way. They’ll bring her back, as many times as they need to, until the rest of the world has decayed and they’re the last two people alive.

This will be a paradise all of their own.

vi. Your Past Sins Cling to You and Won’t Wash Away

Li doesn’t remember who she is.

No, that’s not quite right. She might not remember, but the person taking care of her does. They’re infinitely patient and gentle, prompting her every day to recall her name, their relationship, her past. Even when she stutters, when her brain falters, gaps in her mind where memory should be, they guide her with their voice.

“You’re mine, and I’m yours. We’re always going to be together.” It’s an unfamiliar promise, but one she repeats back anyways.

She doesn’t remember, but they remember for her. And the sketch of herself they present to her is one she doesn’t recognize. Yes, that’s it. She is given memories, but she doesn’t know them, not really.

Her name is supposed to be Li.

Li, Li, Li. Like the fruit, sweet as springtime on expectant lips. That’s how they call her name, a rich harvest of plums in their voice.

And this person is supposed to be important to her. And they are, even before they told her who she was to them, because even though her heart beats slowly and her mind swims sluggishly, struggling to retain every new bit of knowledge that person gives her, there’s a burning in her chest when they talk.

Their face, wane and pale, a full moon in her vision. They’re beautiful, and it seems they’re always close by her side. There’s never an instant in which she can’t see their hair fluttering out of the corner of her eye, their hands ready with thread and needle when some piece of her decays.

This person. Mhin. They’re called Mhin, and she doesn’t want to forget that. She doesn’t want to forget them, as it seems she’s done already, when they brought her back to them.

Mhin. Mhin, Mhin, Mhin. Her lips are too slow for her to say their name as often as she would like, so Li can only savor it in her head. Mhin. Mhin. Mhin. Like a wish, she sounds their name again and again, longing for something she can’t describe.

To be with them. To drag them close to her. To sink her fingers into their skin, to pull apart flesh and muscle until she can curl up in the hollow cavity of their rib cage forever.

Because she can feel it, too. An incessant tugging at the back of her mind, a knot and rope forming somewhere near the base of her neck, a reminder that she doesn’t belong here. That she needs to go back. That her body is only temporary, and this hollow shell can no longer contain who she is.

The pull gets stronger with each day, death’s voice growing louder from the other side of the shore where she stands, water lapping at her ankles.

But she turns away each time, even when the knot and rope tighten painfully, strangling her memories and mind. Because, here on this side, is where they are.

She has to stay. She– Li– must stay here, where they are. Because this is a truth older than memory, deeper than knowledge, an understanding built into the bones they enchanted back to life.

Mhin. Mhin. Mhin. In this world, she doesn’t need to know herself. She only needs to know them, and she will never let them go.

#liya writes#liya’s ocs#touchstarved#mhin#li#touchstarved fanfic#touchstarved game#tucks hair behind my hair cutely#sorry guys I just really needed to get this out I was possessed by my demons

38 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey there! I have a question about Halachic requirements, and you’ve posted some about being raised Orthodox and still being observant so I thought I might ask you. Yesterday while scrolling through Tumblr, I found an image of a Jewish illuminated manuscript, and was so enraptured by the dragons in the marginalia that I decided to find where the image was actually from. After some poking around online, it turns out that the picture is actually from a facsimile of the original text (which was itself a collection of texts for Pesach). I looked through the website’s description of how the facsimile was made, and way down at the bottom it said that only 500 copies were made, and the “printing plates were destroyed (in accordance with Halachic requirements).” I know that there are some rules around writing holy texts with the treatment of the Torah and writing the Tetragrammaton, but I’m not familiar with Halachic requirements as a whole and am wondering which requirements are being referenced here.

(Here’s a link to the website if you want to take a look—it is extremely out of the price range of everyone I know , but the pictures are still really neat: https://facsimile-editions.com/bh/)

What is likely being referred to in this case isn't "requirements to destroy the plates" but rather "requirements regarding the destruction of the plates". Because the plates contained the written name of G-d, they are considered holy, and therefore cannot be disposed of normally. The name of G-d generally cannot be erased, and so any texts or objects containing the name of G-d are buried. Most synagogues have a geniza pile collecting all the old holy objects that periodically gets buried, either in a Jewish cemetery or in the foundation of a new Jewish school or synagogue. Historic geniza piles actually offer a wealth of information for archaeologists, most famously, the Cairo Geniza has yielded so much insight into Jewish medieval life.

So, these printing plates were either destroyed in a way that wouldn't violate the prohibition against the desecration of the name of G-d, or they were buried along with other geniza items.

Further reading:

Proper Disposal of Ritual Objects

Burying Religious Articles

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Facsimile of the original manuscripts of Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo by Jose Rizal.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

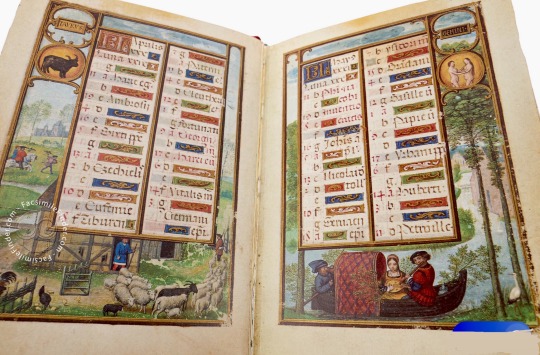

In 2014 I made a few cover-to-cover video facsimiles of a few manuscripts from our collections, as an experiment. One of them is for Ms. Codex 1566, a book of hours, use of Metz, written in the last quarter of the 14th c. This version is sped up x20, you can watch the 19-minute version on YouTube:

You can also see the catalog record here.

#medieval#manuscript#book of hours#illuminated#illustrated#video#video facsimile#metz#france#book history#rare books

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

An AMENDED Rundown on the Absolute Chaos That is First Quarto Hamlet

O, gather round me, my dear Shakespeare friends

And let me tell to ye a tale of woe.

It was a dark and drizzly winter night,

When I discovered my life was a lie...

This tale is a tragedy, one of Shakespeare sources turned into gardening websites, "misdated" quartos, and failed internet archives. It is also a story of the quarto itself, an early printing of our beloved Danish Prince's play, including an implied Hamlet/Horatio coffee date, weird and extremely short soliloquies, and Gertrude with a hint of motivation and autonomy.

But let us start from the beginning. Long ago, in the year of our lord 2022, I pulled a Christmas Eve all-nighter to bring you this post: https://www.tumblr.com/withasideofshakespeare/704686395278622720/a-rundown-on-the-absolute-chaos-that-is-first?source=share

It was popularish in Shakespeare circles, which is why I am amending it now! I returned to it tonight, only to discover a few problems with my dates and, more importantly, a mystery in which one of my sources miraculously turned into a link to a gardening website...

Anyhow, let us begin with the quarto!

TL;DR: Multiple versions of Hamlet were printed between 1603 and 1637 (yes, post-folio) with major character and plot differences between them. The first quarto (aka Q1) is best known for its particular brand of chaos with brief soliloquies, an extra-sad Hamlet, some mother-son bonding, weird early modern spelling, and deleted/adapted scenes with major influences on the plot of the play!

A long rundown is included below the cut, including new and improved sources, lore, direct quotes, and my own interpretations. Skip what bores you!

And continue... if thou darest!

What is the First Quarto? Actually, what is a quarto?

Excellent questions, brave Hamlet fan!

A quarto is a pamphlet created by printing something onto a large sheet of paper and then folding it to get a smaller pamphlet with more pages per big sheet (1).

First Quarto Hamlet was published in 1603 and then promptly lost for an entire two centuries until it was rediscovered in 1823 in the library of Sir Henry Bunbury. Rather than printed from a manuscript of Shakespeare, Q1 seems like it may be a memorial reconstruction of the play by the actor who played Marcellus (imagine being in a movie, memorizing the script to the best of your ability, writing it down, and then selling "your" script off to the print shop), but scholars are still out on this (2).

Are you saying that Hamlet comes with the stageplay equivalent of a “deleted scenes and extra credits” movie disc?

Yep, pretty much! In fact, there are even more of these! Q2 was printed in 1604 and it seems to have made use of Shakespeare's own drafts, and rather than being pirated like Q1, it was probably printed more or less with permission. Three more subsequent quartos were published between 1611 and 1637, but they share much in common with Q2.

The First Folio (F1) was published in 1623 and its copy of Hamlet was either based on another (possibly cleaner but likely farther removed from Shakespeare's own text) playhouse manuscript (2, 3). It was an early "collected works" of sorts--although missing a few plays that we now consider canon--and is the main source used today for many of the plays!

The versions of the play that we read usually include elements from both Q2 and F1.

So... Q1? How is it any different from the version we all know (and love, of course)? What do the differences mean for the plot?

We’ll start with minor differences and build up to the big ones.

Names and spellings

Most of the versions of Shakespeare's plays that we read today have updated spellings in modern English, but a true facsimile (a near-exact reprint of a text) maintains the early modern English spellings found in the original text.

For example, here is the second line of the play transcribed from F1:

Francisco: Nay answer me: stand and vnfold your selfe.

For the most part, however, the names of the characters in these later versions (ex: F1) are spelled more or less how we would spell them today. This is not so in Q1.

Laertes is “Leartes”, Ophelia is “Ofelia”, Gertrude is “Gertred” (or sometimes “Gerterd”), Rosencrantz is “Rossencraft”, Guildenstern is “Gilderstone”, and my favorite, Polonius gets a completely different name: Corambis.

(This goes on for minor characters, too. Sentinel Barnardo is “Bernardo”, Prince Fortinbras of Norway is “Fortenbrasse”, Voltemand and Cornelius--the Danish ambassadors to Norway--are “Voltemar” and “Cornelia” (genderbent Cornelius?), Osric doesn’t even get a name- he is called “the Bragart Gentleman”, the Gravediggers are called clowns, and Reynaldo (Polonius’s spy) gets a whole different name--“Montano”.)

2. Stage directions

Some of Q1's stage directions are more detailed and some are simply non-existent. For instance, when Ophelia enters singing, the direction is:

Enter Ofelia playing on a Lute, and her haire downe singing.

But when Horatio is called to assist Hamlet in spying on Claudius during the play, he has no direction to enter, instead opting to just appear magically on stage. Hamlet also doesn't even say his name, so apparently his Hamlet sense was tingling?

3. Act 3 scene reordering

Claudius and Polonius go through with the plan to have Ophelia break up with Hamlet immediately after they make it (typically, the plan is made in early II.ii and gone through with in III.i, with the players showing up and reciting Hecuba between the two events). In this version, the player scene (and Hamlet’s conversation with Polonius) happen after ‘to be or not to be’ and ‘get thee to a nunnery.’ I’m not sure if this makes more or less sense. Either way, it has a relatively minimal impact on the story.

4. Shortened lines and straightforwardness

Many lines, especially after Act 1, are significantly shortened, including some of the play's most famous speeches.

Laertes’ usually long-winded I.iii lecture on love to Ophelia is shortened to just ten lines (as opposed to the typical 40+). Polonius (er... Corambis) is still annoying and incapable of brevity, but less so than usual. His lecture on love is also cut significantly!

Hamlet’s usual assailing of Danish drinking customs (I.iv) is cut off by the ghost’s arrival. He’s still the most talkative character, but his lines are almost entirely different in some monologues, including ‘to be or not to be’! In other spots, however, (ex: get thee to a nunnery!) the lines are near-identical. There doesn’t seem to be much rhyme or reason to where things diverge linguistically, except that when Marcellus speaks, his lines are always correct. Hm...

5. The BIG differences: Gertrude’s promise to aid Hamlet in taking revenge

Act 3, scene 4 goes about the same as usual with one major difference: Hamlet finishes off not with his usual declaration that he’s to be sent for England but with an absolutely heart-wrenching callback to act 1, in which he echoes the ghost’s lines and pleads his mother to aid him in revenge. And she agrees. Here is that scene:

Note that "U"s are sometimes "V"s and there are lots of extra "E"s!

Queene Alas, it is the weakenesse of thy braine,

Which makes thy tongue to blazon thy hearts griefe:

But as I haue a soule, I sweare by heauen,

I neuer knew of this most horride murder:

But Hamlet, this is onely fantasie,

And for my loue forget these idle fits.

Ham. Idle, no mother, my pulse doth beate like yours,

It is not madnesse that possesseth Hamlet.

O mother, if euer you did my deare father loue,

Forbeare the adulterous bed to night,

And win your selfe by little as you may,

In time it may be you wil lothe him quite:

And mother, but assist mee in reuenge,

And in his death your infamy shall die.

Queene Hamlet, I vow by that maiesty,

That knowes our thoughts, and lookes into our hearts,

I will conceale, consent, and doe my best,

What stratagem soe're thou shalt deuise.

Ham. It is enough, mother good night:

Come sir, I'le prouide for you a graue,

Who was in life a foolish prating knaue.

Exit Hamlet with [Corambis/Polonius'] dead body.

(Internet Shakespeare, Source #4)

Despite having seemingly major consequences for the plot, this is never discussed again. Gertrude tells Claudius in the next scene that it was Hamlet who killed Polonius (Corambis, whatever!), seemingly betraying her promise.

However, Gertrude’s admission of Hamlet’s guilt (and thus, betrayal) could come down to the circumstance she finds herself in as the next scene begins. There is no stage direction denoting her exit, so the entrance of Claudius in scene 5 may be into her room, where he would find her beside a puddle of blood, evidence of the murder. There’s no talking your way out of that one…

6. The BIGGEST difference: The added scene

After Act 4, Scene 6, (but before 4.7) comes this scene, in which Horatio informs Gertrude that Hamlet was to be executed in England but escaped:

Enter Horatio and the Queene.

Hor. Madame, your sonne is safe arriv'de in Denmarke,

This letter I euen now receiv'd of him,

Whereas he writes how he escap't the danger,

And subtle treason that the king had plotted,

Being crossed by the contention of the windes,

He found the Packet sent to the king of England,

Wherein he saw himselfe betray'd to death,

As at his next conuersion with your grace,

He will relate the circumstance at full.

Queene Then I perceiue there's treason in his lookes

That seem'd to sugar o're his villanie:

But I will soothe and please him for a time,

For murderous mindes are alwayes jealous,

But know not you Horatio where he is?

Hor. Yes Madame, and he hath appoynted me

To meete him on the east side of the Cittie

To morrow morning.

Queene O faile not, good Horatio, and withall, commend me

A mothers care to him, bid him a while

Be wary of his presence, lest that he

Faile in that he goes about.

Hor. Madam, neuer make doubt of that:

I thinke by this the news be come to court:

He is arriv'de, obserue the king, and you shall

Quickely finde, Hamlet being here,

Things fell not to his minde.

Queene But what became of Gilderstone and Rossencraft?

Hor. He being set ashore, they went for England,

And in the Packet there writ down that doome

To be perform'd on them poynted for him:

And by great chance he had his fathers Seale,

So all was done without discouerie.

Queene Thankes be to heauen for blessing of the prince,

Horatio once againe I take my leaue,

With thowsand mothers blessings to my sonne.

Horat. Madam adue.

(Internet Shakespeare, Source #4)

First of all, the implication of Hamlet and Horatio's little date in the city is adorable ("Yes Madame, and he hath appoynted me / To meete him on the east side of the Cittie / To morrow morning.") It reads like they're going out for coffee!

And perhaps more plot relevant: if Gertrude knows of Claudius’s treachery ("there's treason in his lookes"), her death at the end of the play does not look like much of an accident. She is aware that Claudius killed her husband and is actively trying to kill her son and she still drinks the wine meant for Hamlet!

Now, the moment we’ve all been waiting for! My thoughts! Yippee!

On Gertrude:

WOW! I’m convinced that she is done dirty by F1and Q2! She and Hamlet have a much better relationship (Gertrude genuinely worries about his well-being throughout the play.) She has an actual personality that is tied into her role in the story and as a mother. I love Q1 Gertrude even though in the end, there’s nothing she can do to save Hamlet from being found out in the murder of Polonius and eventually dying in the duel. Her drinking the poisoned wine seems like an act of desperation (or sacrifice? she never asks Hamlet to drink!) rather than an accident.

On the language:

I think Q1′s biggest shortcoming is its comparatively simplistic language, especially in 'to be or not to be,' which is written like this in the quarto:

Ham. To be, or not to be, I there's the point,

To Die, to sleepe, is that all? I all:

No, to sleepe, to dreame, I mary there it goes,

For in that dreame of death, when wee awake,

And borne before an euerlasting Iudge [judge],

From whence no passenger euer retur'nd,

The vndiscouered country, at whose sight

The happy smile, and the accursed damn'd.

But for this, the ioyfull hope of this,

Whol'd beare the scornes and flattery of the world,

Scorned by the right rich, the rich curssed of the poore?

The widow being oppressed, the orphan wrong'd,

The taste of hunger, or a tirants raigne,

And thousand more calamities besides,

To grunt and sweate vnder this weary life,

When that he may his full Quietus make,

With a bare bodkin, who would this indure,

But for a hope of something after death?

Which pusles [puzzles] the braine, and doth confound the sence,

Which makes vs rather beare those euilles we haue,

Than flie to others that we know not of.

I that, O this conscience makes cowardes of vs all,

Lady in thy orizons, be all my sinnes remembred.

(Internet Shakespeare, Source #4)

The verse is actually closer to perfect iambic pentameter (meaning more lines have exactly ten syllables and consist entirely of iambs--"da-DUM") than in the Folio, which includes many 11-syllable lines. The result of this, however, is that Hamlet comes across here as considerably less frantic (those too-long verse lines in F1 make it feel like he is shoving words into too short a time, which is so very on-theme for him) and more... sad. Somehow, Q1 Hamlet manages to deserve a hug even MORE than F1 Hamlet!

Nevertheless, this speech doesn't hit the way it does in later printings and I have to say I prefer the Folio here.

On the ending:

The ending suffers from the same effect ‘to be or not to be’ does--it is simpler and (imo) lacks some of the emotion that F1 emphasizes. Hamlet’s final speech is significantly cut down and Horatio’s last lines aren’t quite so potent--although they’re still sweet!

Horatio. Content your selues, Ile shew to all, the ground,

The first beginning of this Tragedy:

Let there a scaffold be rearde vp in the market place,

And let the State of the world be there:

Where you shall heare such a sad story tolde,

That neuer mortall man could more vnfolde.

(Internet Shakespeare, Source #4)

Horatio generally is a more active character in Q1 Hamlet. This ending suits this characterization. He will tell Hamlet’s story, tragic as it may be. It reminds me a bit of We Raise Our Cups from Hadestown. I appreciate that this isn't a request but a command: put up a stage, I will tell this story.

Closing notes:

After over a year, it was due time this post received an update. My main revisions were in regard to source verification. Somehow, in the last year or so, one of my old sources went from linking to a PDF of Q1 to a garden website (???) and some citations were missing from the get-go as a result of this being an independently researched post that involved pulling an all-nighter on Christmas Eve (but no excuses, we need sources!)

I have also corrected some badly worded commentary implying that the Folio's verse is more iambic pentameter-y (it's not; in fact, Q1 tends to "normalize" its verse to make it fit a typical blank verse scheme better than the Folio's does--the lines actually flow better, typically have exactly ten syllables, and use more iambs than Q1's) as well as that the spelling in the Folio is any more modern than those in Q1 (they're both in early modern English; I was mistakenly reading a modernized Folio and assuming it to be a transcription--nice one, 17-year-old Dianthus!) Additionally, I corrected the line breaks in my verse transcriptions and returned the block quotations to their original early modern English, which feels more authentic to what was actually written. A few other details and notes were added here and there, but the majority of the substance is the same.

Overall, if you still haven't read Q1, you absolutely should! Once you struggle through the spelling for a while, you'll get used to it and it'll be just as easy as modern English! If you'd prefer to just start with the modern English, I have also linked a modern translation below (source 5).

And finally, my sources!

Not up to citation standards but very user-friendly I hope...

1. Oxford English Dictionary

2. Internet Shakespeare, Hamlet, "The Texts", David Bevington (https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/Ham_TextIntro/index.html)

3. The Riverside Shakespeare (pub. Houghton Mifflin Company; G.B. Evans, et al.)

4. Internet Shakespeare, First Quarto (facsimile--in early modern English) (https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/Ham_Q1/complete/index.html)

5. Internet Shakespeare, First Quarto (modern English) (https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/Ham_Q1M/index.html)

And here conclude we our scholarly tale,

Of sources, citation, and Christmastime too,

Go read the First Quarto! And here, I leave you.

#shakespeare#hamlet#first quarto#first quarto hamlet#classic literature#revisions#hey look at me#having some scholarly merit#i have so much left to learn#which is a darn good thing#how else would i spend my evenings?#the worst part about this#is that it all started because i thought a got a date wrong#but it turns out i didn't#so HA!#but then i realized i got everything else wrong so....#corrections it is!

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The forgery thing was legitimately ongoing for years. Once I made a facsimile of a manuscript page from our Special Collections: parchment, iron gall ink that I made myself, pigment in egg tempera for the initials, the works. When my paleography professor saw it she was so impressed and said that the only reason she knew it wasn't actually from the 12th Century was that it wasn't faded like she'd expect. I told my mom about this and she immediately scolded me for not devoting my life to Manuscript Crimes.

67 notes

·

View notes