#sharpe saturday

Text

Happy Sharpe Saturday

465 notes

·

View notes

Text

#detective conan#meitantei conan#名探偵コナン#dcmk#detco#polls#detco posting#i've been curious and i just... i guess i just want to see ppl's thoughts#and hear what they think#i don't think many ppl will see this but anyways#only those movies made it in here after some consideration that i like overall#so anything not here: i liked certain details in those but the whole or almost the whole movie#(i have a strange relationship with movie 13 bc of 1-2 details but overall? still awesome good watching experience)#anyway: PLS SHARE THOUGHTS I AM CURIOUS#reference for myself: posted saturday 12 sharp

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

you don't say.

#calling teeth “soft” is somehow creepier than calling them sharp#like imagine having marshmallow or jello for teeth#eugh#tmagp#the magnus protocol#tmagp spoilers#tmagp ep 10#tmagp saturday night#magnus protocol#the magnus protocol spoilers#mr bonzo

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

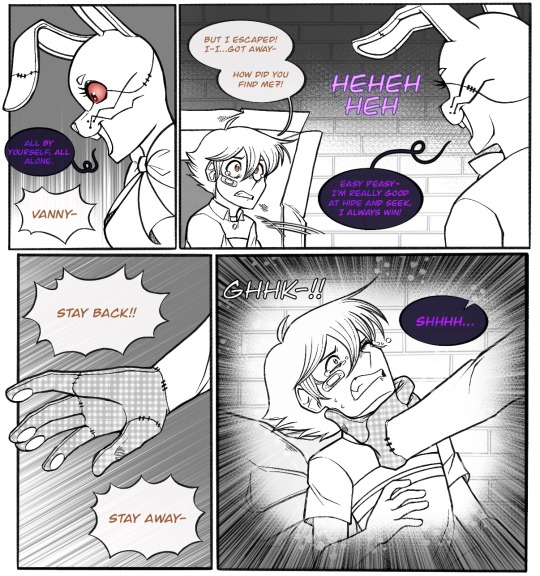

Page 21, I actually divided it into two pages I think I’ll just start making them shorter to be able to get to them more easily ^^ hopefully I’m not …. Getting too violent with children in my comics ><“

Previous - next- first

#my art#fnaf#five nights at freddy's#security breach#Vanny#gregory#fazbear frights#into the ballpit au#into the pit#yeahhhhhhhhhhh uhhhhhhmmmmmmmmmmmmm he’s fine Vanny’s hand is all plushy#she’s not …. -sigh- packs my bags and leaves because I am being too violent to children and there’s no excuse-#anyway#happy Saturday#I’ll be cleaning the house when this thing posts =w=#and yes Gregory has super sharp teeth he’s a gremlin ok#he needs to bite his way out of some situations

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

they passed art class 🥹🫶🏻

#firstkhao#firstkhaotung#first kanaphan#khaotung thanawat#gmmtv#they are 5yrs old when the cameras are not rolling#someone supervise them#don't let them play with scissors or sharp pencils#but also the way khao is holding his pen is making my hand hurt lmao#i used to write like that as a kid and my mom would get mad at me djkhfgd#but anyway#theyre my babes i love them more than anything#is it saturday yet???? 😩

132 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you seen the Frankenstein Chronicles? The first episode is full of Sharpe references. When he's unpacking his kit you see his greenjacket and sword, and when someone asks who he served with, he says 95th Rifles. And another character whistles Over the Hills in the background. I was giggling and kicking my feet the whole way through.

I had not heard of this show before and after a bit of a wikipedia wander I will Certainly be watching it, and not just for the Sharpe references...

given that this also has Necromantical-Science, A Weird Murder Mystery, Probably A Significant Amount of Meat, and Ada Lovelace, this sounds like the Perfect Show for me!

#answers from the cupola#em is posting about sharpe#(tangentially)#actually this show sounds a Lot like the wolf and the watchman and I had fun? there so I will probably have fun? here as well#...now I am thinking about what if you cast sean bean as mickel cardell. he could do that Maybe. Hmm.#this is a very amusing way to recommend me a show given that I was going to watch the 2005 p&p on saturday#just for playing spot the south essex lads!#(in the end none of the people I asked to join in were available to come with me so I watched the lighthouse by myself at home)

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

bigger idiots than me have done it. bigger idiots than me have done it. bigger idiots than me have done it. bigger idiots than me have done it. BIGGER IDIOTS THAN ME HAVE DONE IT. BIGGER IDIOTS THA-

#anyone else feeling like a teenage girl kendall on this fine saturday#succession#succession hbo#kendall roy#bigger idiots than me have done it#bigger idiots than you have done it#amy adams#sharp objects

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

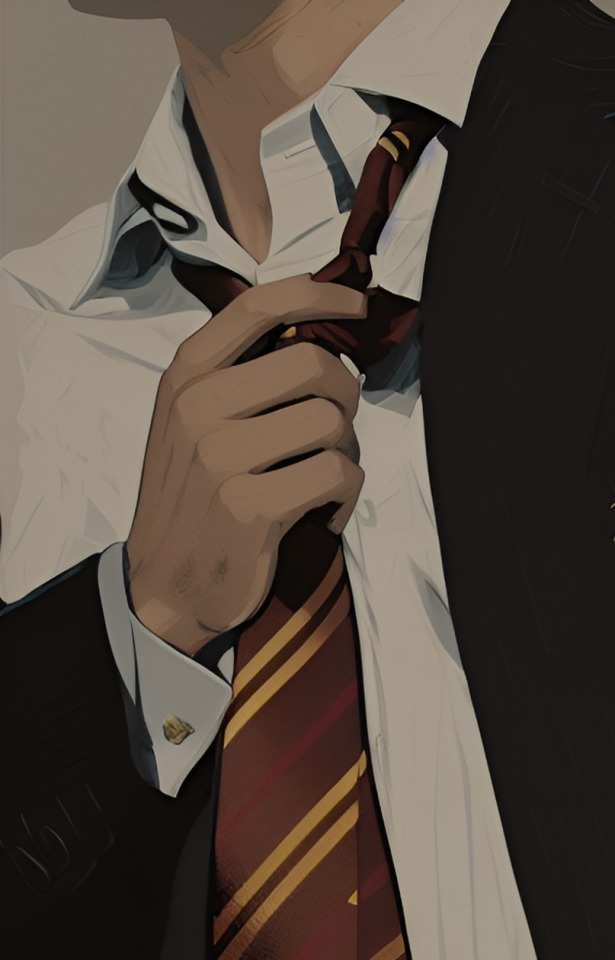

Aesop Sharp/Garreth Weasley 🙈🙈🙈

Ok, I know what you lot might be thinking, but HEAR ME OUT ON THIS ONE! Or just give this little mischievous story a read 🌝

NSFW 🔞 MDNI

Voyeurism | "Forbidden" love | Teacher/Student relationship

— Minus twenty points to Gryffindor, Mr. Weasley. And detention. Again.

Cressida hears the heavy sigh of the Potions Master and looks at her classmate with dislike. Stupid Garreth! For seven years, he hasn’t managed to learn just to follow the recipe, almost every lesson still ends with a nearly blown-up cauldron and a sigh from Professor Sharp. And how many points has Weasley cost Gryffindor over the years! It must have been because of him that her house hadn’t won the Hogwarts Cup for a long time. However, it doesn't matter anymore. Blume adjusts her round glasses with thick lenses and shakes her head. The last year. She should focus on her research!

Cressida proudly raises her head and walks towards one of the closed, "out of order" restrooms. She likes Hogwarts, but there is definitely not enough space for independent practice here. She has to be sneaky if she wants to continue testing her theories. Previously, Professor Sharp allowed her to use his office to practice potions additionally, but after the incident in the Great Hall, when Blume was training Depulso and accidentally sent a Yorkshire pudding right in the face of the Potions Master, he changed his views on favoring her. Oh boy, did it cost Gryffindor points back then!

Cressida importantly pushes the wooden door, muttering a spell of her own composition. No one would have been able to find her cauldron under these charms — the Gryffindor was insanely proud of herself, but so far she kept these achievements secret, trusting only her diary, which she also decided to enchant from prying eyes after a certain incident in the fifth year. A cauldron is bubbling in a narrow booth on a tiny station — lately, Blume has switched exclusively from spells to improving potions. And unlike restless Weasley’s concoctions, none of them have ever exploded. However, none of them have ever improved properly either. But Cressida did not despair and persevered in her experiments.

This time, the silvery flare on the walls is cast by an invisibility potion, the effect of which usually lasts for a very short time. Blume is determined to fix this glaring flaw and extend the effect. After many attempts, she finally calculated the necessary proportions and figured out what affects the duration. Now, with a sinking heart, she pours a not-at-all-hot, playfully bubbling liquid into a prepared vial.

The girl lifts the narrow tube to the light and carefully examines its color and consistency, nodding satisfactorily and ordering the quill to make notes. The potion in the vial sparkles invitingly and Cressida, crossing her fingers on her other hand, knocks the contents into herself. It's quite dangerous to test experimental potions right away, on yourself, but Blume is ready to do anything for the sake of research .

A second later, the girl notes with pleasure that the potion still performs its function — her arms and torso are now nothing more than a slight ripple in space, much less noticeable than the usual effect of the Disillusionment charm. For the beginning, everything is going pretty well, but Cressida does not allow herself to rejoice prematurely. She marks the time to assess how much the effect has been prolonged for — the enchanted hourglass, swaying with pot-bellied sides in the air, began counting down exactly at her command. The only thing left to do is to wait a little.

Ten minutes! This is already an incredible success, the Gryffindor describes her sensations, and the quill, obediently rustling on the parchment, writes down the data. Twenty minutes. Hour. One and a half. Cressida is still invisible, the sand in the clock has long ceased to fall, the quill hovering in the air in bewilderment. Something's wrong. For some reason, it lasts for too long. Blume, worried, raises her wand and, pointing at herself, confidently says “Finite Incantatem”. Zero effect. Of course, counter-curse usually works against other charms, not potions, but it was worth a try. The girl has a spare antidote, but she is clearly not poisoned — will it work?

Three hours. The Gryffindor begins to worry a lot and gives up in an internal struggle, takes the notes and a sample, and heads to the dungeons. It's very funny to watch how students behave without noticing her. Although not everything went strictly according to plan, Blume is still pleased with herself. Surely Professor Sharp will be impressed! Maybe even let her use the potions room again.

Having got close to the slightly open doors of the classroom, Cressida slips inside, intending to raise her voice — the only thing that can give away her presence, but freezes when she sees the familiar red hair. Of course, it's already evening, and Weasley has earned himself detention. There is no sign of Potions Master within her sight — it looks like he is rummaging in his small office, and Garreth, pushing the knot of his tie a little lower, unbuttoned the top buttons of his shirt, exposing a sharp Adam's apple. A mischievous thought flashes through Blume's head — to make fun of a fellow student by introducing herself as the voice of conscience in his head. The fact that there is no other voice of conscience there was absolutely undoubtful to her. Almost shrieking from her own brilliant idea, she sneaks up to Garreth, but the sound of creaking hinges makes her stop — the professor, without his usual jacket and coat, in only a shirt and vest, leaves his office, raising his eyebrows at the troublemaker.

“Mr. Weasley!” the teacher's voice is not as gloomy as usual, it even seems to Cressida that there is a hint of light sadism in it. “For several weeks, classes have been held without incident, I was hoping that I wouldn't have to leave you for detention anymore!”

Garreth turns to face the professor and squints, smiling slyly. What impudence! Cressida holds her breath, waiting for the Potions Master's reaction and completely forgetting why she came here. It is unlikely that the professor will appreciate the fact that she has been shamelessly eavesdropping, taking advantage of the situation. The girl is about to open her mouth to announce her presence, but Weasley is ahead of her, for some reason raising his wand and waving it somewhere to the side.

“It seems to me, Professor, you have never really regretted it,” the door of the Potions room closes with a soft knock, light sparks run along the ornate handle — the entrance is sealed. Cressida looks back at the scene unfolding in front of her with mouth open, trying not to breathe.

The Potions Master smiles like a predator and with a frolic that is difficult to expect from a person with his injury, shortens the distance between him and the student, grabbing Garreth by the bare neck with a sinewy hand and squeezes slightly, lifting student's chin up and forcing him to back away to the professor's desk. Weasley, resting his hips on the table, exhales with a strangled wheeze, teasingly looking into the teacher's eyes, literally devouring him.

Has Sharp just attacked a student? Blume can't even move, not knowing what to do: whether to grab a wand and help Garreth — no matter how much he annoys her, the guy clearly does not deserve such a fate! But she doesn’t even have time to put her hand in the pocket to find the usual rough shaft of the wand there, as the red-haired freckled devil does something that does not fit in the head of the seventh-year — sweeping away papers and bottles behind him with one hand, he jumps onto a round table, with the other hand pulling the professor by the edge of his vest closer, so that the groins of both touch, and wraps his legs around Sharp's hips, pressing even harder, forcing the professor to loom over him. Aesop is still squeezing the student's neck, rubbing his hips against Weasley's groin, breathing noisily, and glaring at Garreth's flushed cheeks with a clouded gaze.

“You're forcing me to take serious measures, Mr. Weasley," the professor mutters hoarsely, feeling a hard lump in the other’s trousers, but not taking his eyes off the cunning squint of the Gryffindor.

The student, fidgeting with his hips on the classroom table and still throwing his neck back, squeezed by Sharp's strong hand, with dexterous long fingers Garreth fumbles for the buttons of the professor's vest and releases them one by one, brazenly withstanding the gaze boring into him. When he is finished with the buttons, Weasley rises in one sharp movement, throwing an unnecessary garment off the teacher's hunched shoulders, and presses his body against the chest of the Potions Master.

"I'm ready to accept any punishment, Professor," Garreth breathes into the teacher's face, and the next second Cressida's eyes crawl to her forehead.

Professor Sharp, a Potions Master, and an ex-Auror, pulls her classmate by the neck closer, and furiously, greedily covers Weasley's lips with his own, keeping pushing his hips forward. Both are breathing heavily and moaning hollowly, not looking away from each other, aggressively kissing and burying themselves in each other's hair. Blume is still standing a little apart, not daring to budge and realizing that she shouldn't be seeing all this, but an unfortunate (or, on the contrary, rather fortunate) viewing angle lets her see almost every movement, touch and every glare in the crazy eyes of both. Their eyes are actually quite strange as if they both had too much firewhisky. Right, maybe it's some kind of hallucination? Of course, the professor realized long ago that she was here, and now he is punishing her for her mistake with some sophisticated potion that causes visions. But if so, why is that what she sees?

Garreth greedily penetrates the teacher's mouth with his tongue again and again, unbuttoning snow-white shirt of the professor with his hands now. Sharp pushes off with a groan, removing his fingers from the red curls, and puts his palms on both sides of the student's thighs, forcing the redhead to rub against his crotch with even louder moans.

"What are you saying, Mr. Weasley?" the professor exhales in his ear in a deep, soothing voice, allowing the student to undress him, biting the lobe of his ear and feeling a shiver pass through Gareth's body from his breathing and touch. “Do you repent of what you did?”

The Gryffindor raises his clouded green eyes to the teacher and smiles ecstatically, already running his fingers over ex-Auror's chest and collarbones, and stroking his broad shoulders. Aesop catches his every move, continuing to frantically squeeze his narrow hips.

“I think you'll have to punish me a little more,” Weasley's fingers got to the heavy buckle of the professor's trousers, and now they are in full possession, greedily touching hot sensitive flesh.

Sharp whines softly, throwing his head back, letting the student take control with teasing movements for a second, but very soon pulls himself together and, gripping the burgundy tie with golden stripes, pulls it behind Garreth's back, admiring the open, sparsely freckled neck. Weasley obediently follows the insistent movement of the teacher's hand and, throwing his head back again, trembles slightly when the hot tongue of the potion maker slides up his protruding Adam's apple, leaving shiny tracks, circles his chin and, again, penetrates into his mouth.

"You don't know when to stop, Mr. Weasley. I'm afraid I'll have to teach you a lesson," the ex-Auror mutters hoarsely, tearing himself away from his student's swollen, flushed thin lips, and suddenly pulling the ribbon of his tie even tighter, squeezes the lump in the other's pants.

Garreth lets out a hoarse moan.

“Yes,” he breathes out in euphoria, feeling a frenzied excitement from the manipulations of the teacher and from the silk strip pressing on his throat slightly. “Harder.”

Sharp, smiling smugly, pulls his tie even more down, listens attentively to every wheeze, and, squeezing Weasley's crotch tighter, feels that he can barely contain his excitement himself. Releasing the burgundy strip of fabric, he takes a couple of steps away, admiring the hot young body, and throws off his trousers, revealing an impressive rock-hard cock, covered with a net of swollen veins. Cressida, who has been on the verge of fainting for a long time, barely restrains herself from crying out, covering her mouth with a sweaty palm. At the bottom of her stomach, a feeling unfamiliar to her before pulls with heat, from which her heart starts pounding faster, and her breathing quickens. Fortunately, with all the loud sighs and groans that these two make, she is the only one who can hear her breathing.

The professor, wearing only an unbuttoned shirt now, sinks into his chair, spreading his legs wide, and, wrapping a tight ring of fingers around his penis and not taking his eyes off the student, begins to move them up and down. Weasley, catching his breath and jumping off the table, immediately puts himself next to the Potions Master and kneels in front of him, his face very close to Aesop's groin.

“Let me make it up for you, professor,” having slid with his palms from the knees to the bare thighs of the teacher, he suddenly swallows the bright pink shiny head and, repeating Sharp's movements before, with wet sounds starts sucking his organ in, helping with his tongue.

Aesop, allowing the student to caress him, leans back in his chair, rolling his eyes and breathing unevenly with a muffled whistle, squeezes the armrests of the chair so that the veins on his hands seem about to burst. Weasley, who seems to be doing this not for the first time, playfully draws circles around a sensitive penis with his tongue, rising from the bottom up, paying special attention to the head, and abruptly swallows the organ as deeply as he can, knocking out an indecently loud moan from the professor. Gasping, Garrett tries to free his airways, but Sharp grabs him by the hair and holds him there, thrusting his hips deeper into his throat. After a few seconds, during which he almost finishes, he lifts the student off himself, barely allowing him to take a deep breath, and immediately kisses him hotly on the lips, insistently groping for the tongue that has just almost brought him to orgasm. But the Potions Master knows what the red-haired devil is waiting for, and has long learned to control himself. They haven't finished yet.

“Well, Mr. Weasley, I must say that you definitely know how to make amends,” the teacher gets up from his chair and, again grabbing the student by the tie, slowly lifts him up and, as if by a leash, leads him back to the table. “But your punishment is still ahead.”

Garreth, excited and ready, jumps back on the table, allowing Aesop to pull off his trousers. Sharp spreads the student's legs slightly to the sides, almost licking his lips, examining the view in front of him. With a slight movement of his hand, he opens a drawer inside the table and takes out a small bottle with a translucent viscous liquid. Generously dripping the substance directly on the student's groin, the Potions Master runs his thumb down the scrotum with reddish hairs, distributing the lubricant around the heated hole. Weasley, leaning back on the table, trembles from the cold touches, but the professor, wrapping his other hand around the student's cock, begins to slowly drive over it, forcing Garreth to relax. Aesop gently circles the edges of the shrunken rim with his thumb and, not seizing to work with his other hand, gently inserts his fingers inside, forcing the Gryffindor to emit a guttural moan of pleasure. Careful at first, finger movements are accelerated, slightly stretching everything inside. Sharp can't stand it anymore, his fingers wrapped around Garreth's organ start flying faster on it, while the ex-Auror, helping himself with his other hand, finally gets his cock in, forcing Garreth's flexible narrow back to arch towards him. Aesop, at first cautiously, but increasingly confidently driving himself into a tight hot space, feverishly wanders with his eyes over the freckled face of Weasley, who, completely surrendering to the caresses of the professor, stands up on his elbows and trustfully pushes forward.

“Yes, Professor," he whines, feeling the approach of orgasm. “I am already…”

Sharp, having accelerated, feels the penis throbbing in his hand and erupting sperm in all directions, and, now grabbing Weasley's clenched thighs with both hands, impales him on himself in a few more strong thrusts, until with a long moan of happy devastation he starts to tremble all over, fingers digging into the student's skin, undoubtedly leaving traces on it.

Like this, they stand for a few more minutes, recovering their breath. Aesop, wiping the sweat off his forehead, comes out of Garreth and, helping him up, pulls him by the hand, this time gently catching his lips. He steps aside, picks up the wand that has rolled to the side, and directs it to the sperm spreading over the sunken stomach with a few ginger hairs in the bottom. Weasley, rising after him, busily pulls on his clothes. The Potions Master, still breathing heavily, sinks into a chair, watching as the student tucks his shirt into his trousers with an expression of pleasant fatigue.

"Garreth, I'm certainly very flattered that you so often look for an excuse to get a detention with me, but maybe we should be careful," Sharp says softly, thoughtfully lowering his chin on his fist. “Let's have a couple of classes without incidents, okay?”

Weasley, pushing back the red curls stuck to his forehead with his palm, approaches the professor and, lifting his stubble-covered chin, kisses him again, slowly and sensually.

“As you say, Professor," he replies with a mischievous twinkle in his eyes, hastily adding. “But this time the explosion was unintentional – it turned out that adding pickled growths of Murtlap to the Forgetfulness Potion was a bad idea.”

Sharp shakes his head kindly and watches the student's back. Cressida, flushed and pressed against the wall, prays only for the dust, that has been tickling her nostrils for several minutes now, not to make her sneeze, giving away her presence. What will the Potions Master do to her if he finds out, that she witnessed his secret meetings? At best, he will put an Obliviate on her. However, Blume would probably gladly prefer to forget about what she just saw.

After regaining his breath, the professor rises and with a wave of his wand beckons the clothes scattered on the floor to him, and returns the documents dropped by Garreth to their usual places. For a second, Cressida thinks his gaze is directed right at her, but Aesop calmly walks towards his chair again, pulls on his trousers, and heads back to his office. Seizing the moment, she takes off from her hiding place and runs out of the classroom, finding herself at the other end of the castle in a matter of minutes. It's a miracle that the ex-Auror did not notice her presence — for sure, he was too caught up in other thoughts. Cressida is still invisible, and it seems that another visit to the professor is inevitable.

But there's nothing wrong with staying invisible for a little longer. As long as she doesn’t get to witness somebody else’s secret. As for this one – she will just try to forget about it, and will definitely not tell anyone. Except for maybe her diary.

Ok, so if you got to this point, please let me know what you think, so I don't die of embarrassment 🌚🌚🌚

#hogwarts legacy#hogwarts legacy fanfic#fanfic#aesop sharp#professor aesop sharp#daddy sharp#garreth weasley#weasley wednesday#sharp saturday#garreth x aesop#aesop x garreth#garraesop#??#aesarreth#???#omfg#cressida blume#pwp fics#voyerurism#hl fanfiction#ai artwork#ai art

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

YALL, ITS UP!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

ok i survived yom kippur. but it took every single scrap of strength in my body and i’m not completely better yet

#purrs#food#ask to tag#got my period thursday… bad cramps friday and saturday to the point where i had to go home early saturday (we were working lol 🤪)…. woke up#sunday with a. headache that got worse and worse throughout the day… 5-6 hours into the fast was in agony and felt like i was going to ****#so i… broke the fast and ate something at like 1am. then woke up in agony at 5am and then again at 9am and had a breakdown / fight with my#mom and then spend the whole rest of the fast deathly nauseous and my head hurting worse than ever. broke the fast an hour before everyone#else did (only ate a tiny bit) and then during the fast breaking dinner i started freaking out bc eating wasn’t making my head hurt less so#my grandpa told me to go lie down with a heating pad on my head and i did and slept for like 2 hours and it helped. finally feel better but#my head still hurts faintly and im scared it’ll come back. also i didn’t do my homework and missed class today to fast so im fucked#ive had headaches like this before but this is the worst one in a LONG time. it wasn’t a migraine bc those are in one specific spot iirc but#this was like… my ENTIRE face and the source of the pain migrated from my jaw to my temple to the bridge of my nose to the back of my head#etc etc and it kept moving around and was so sharp i didn’t even have the strength to open my eyes or walk around. and i think it was making#me interpret hunger as nausea. also i took my temperature bc i was flashing hot and cold and was like 2 degrees under normal body temp and#felt so weak and shaky and had body aches too. lol 😍 hpefully the worst of it is over but my head still hurts a little and im so scared itll#happen again. that was by far my worst fasting experience ever#delete later

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The amount of crappy AUs I’ve made out of sheer denial of a character’s death is insane

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inspiration Saturday

A late entry for what’s inspiring my writing today. How about you @shortsighted-owl @stereopticons @blackandwhiteandrose @lizzie-bennetdarcy @rmd-writes @ajunerose @apothecarose @elvensorceress ?

#inspiration saturday#picking suits for the boys#they’re gonna be so sharp#thank you to BWR for the snazzy options#buck x eddie#fic: whatever may come

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

#baby haim#what sharp teeth you have …#saturday mornings#pencil drawing#hamish linklater#hamfam#drawing#doddle

28 notes

·

View notes

Link

I had forgotten today was Small Business Saturday! In lieu of that, I’m having a sale of everything is 25% off in my store if you use the coupon SYRUP25 at checkout! If you spend $200+, you get a free Chonk D20!

#handmade dice#dice maker#dice goblin#polyhedral dice#ttrpg dice#dnd dice#d&d dice#dice set#sharp edge dice#dice#small business saturday#small business

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Politics of Ian McEwan’s ‘Saturday’

[One of my fav reviews I read way back in the elder days of blogs…that is, February 5, 2005. I’ve realized that some of the formative pieces of reviews I read when a much more callow youth are disappearing or already disappeared from the internet, so I’ve decided to start saving them on here for my own memory. This critique of Ian McEwan’s Saturday by the experimental British writer Ellis Sharp, whose blogs Barbaric Document and The Sharp Side are long consigned to Wayback Machine passes, definitely started the process of eroding my interest in mainstream literary fiction. Barbaric Document was last updated July 5, 2011, though Sharp is still writing novels.]

This is a novel which is set entirely on 15 February 2003, the day of the great London anti-war march.

Not a single character in this novel goes on the march.

Although most of them live and work in central London, they are all doing something else that day. The march only exists filtered through the consciousness of Henry Perowne, the brain surgeon protagonist. He catches glimpses of it from a distance. He sees it on the TV news. From time to time he comments on the marchers.

Perowne is off to play squash, and, as a result of the road closures that day, gets involved in a car crash with a sinister thug named Baxter. Henry is “ambivalent” about the war, as a result of knowing an Iraqi torture victim. And this torture victim would not approve of the anti-war march; from his perspective, “Across Europe,, and all around the world, people are gathering to express their preference for peace and torture.” (p. 126) Perowne thinks that “the humanitarian reasons for war” is “the only case worth making” (p. 69). He doesn’t like the anti-war marchers. He thinks they are frivolous. He complains that they are too cheerful:

“All this happiness on display is suspect. Everyone is thrilled to be together on the streets – people are hugging themselves, it seems, as well as each other. If they think – and they could be right – that continued torture and summary executions, ethnic cleansing and occasional genocide are preferable to an invasion, they should be sombre in their view.” (pp. 69-70)

Nowhere in Saturday is there the perception that the forces pressing for war are precisely the same forces which subsidised, protected and armed the regime which carried out those atrocities. As a novel about politics, history and medicine, it suffers from its own unspoken narrative malady: amnesia.

McEwan dances away from troublesome specifics. We’re told that Perowne has a great relationship with his son and that “They’ve never talked so much before” (p. 34) Among the topics of discussion are “Israel and Palestine, dictators, democracy”. A bit vague, wouldn’t you say? Pleasantly vague. Evasively vague.

Perowne’s squash partner is pro-war and has to abandon his car south of the river and jog to the squash court. Perowne’s wife is a high flying lawyer who is absent all day, tied up at the High Court fighting for press freedom. Alas, the judge (sympathetic to her press freedom argument) is delayed by the demonstration. Perowne’s father-in-law, a famous poet, is flying in from France for a Saturday night family get-together.

Perowne has two fabulously talented kids – so talented you wouldn’t want to receive a Christmas round robin letter from the Perownes, and if you got one you’d want to forward it to Simon Hoggart. Perowne’s daughter, a stunningly talented young poet about to be published by Faber, is flying in from Paris, where she is currently living. Perowne’s son, Theo, a hugely talented 18 year old blues guitarist, is against invading Iraq, but he’s not on the march either:

“His attitude is as strong and pure as his bones and skin. So strong he doesn’t feel much need to go tramping through the streets to make his point.”

(p. 151)

I’m still trying (and failing) to make sense of that fuzzy logic. And I don’t find it remotely plausible that a cool young dude who was passionately against the war and lived just a few hundred metres from the start of the march would think: Nah, I’m not going on it, it’s a complete waste of time.

McEwan does permit an anti-war voice to enter his narrative, on p. 185, when Perowne’s daughter Daisy arrives from Paris and on the way home from the airport stops by at Hyde Park to hear some of the speeches. She and her father proceed to have an argument about the war, with Perowne (sometimes almost verbatim) expressing McEwan’s own published reservations.

Daisy, aged 18, is a tremendous fan of Philip Larkin, who is her favourite poet. “Apparently, not many young women loved Philip Larkin the way she did.” (p. 56) True enough: 18 year old girls probably prefer Snow Patrol to Philip Larkin. But probably not many anti-war protesters were into Larkin either, one suspects, bearing in mind Larkins’ racism, sexism and miserabilist verse which yearns for a fantasy pre-First World War England, mocks and stereotypes the ghastly vulgar working classes and has a gloomy fixation on the inevitability of death (written in his younger days – ironically when he grew old his poetry dried up and he retreated into booze and singing jolly racist chants with his charmless alcoholic lover). As Tom Paulin somewhere remarks, underneath the Larkin monument runs a stinking sewer. But McEwan himself evidently likes Larkin, whose verse is the only copyright material cited in Saturday.

The argument between father and daughter rages on, until Perowne stops it with a bet:

‘My fifty pounds says three months after the invasion there’ll be a free press in Iraq, and unmonitored Internet access too. The reformers in Iran will be encouraged, those Syrian and Saudi and Libyan potentates will be getting the jitters.’

Daisy says, ‘Fine. And my fifty says it’ll be a mess and even you will wish it never happened.’ (p. 192)

McEwan finished writing Saturday in the second half of 2004. This allowed him the wisdom of hindsight. (At one point – p. 151 - there’s a careless reference to “the war in Iraq” – but of course the war hadn’t yet started. What McEwan should have written was “the war ON Iraq” or “war WITH Iraq”.) By fixing Perowne’s bet on the state of affairs in Iraq three months after the invasion, McEwan allows both sides to be at least partly right. Yes, there was a free press! Yes, there was unmonitored Internet access! But, yes, it was a bit of a mess too!

If he’d fixed his bet one year after the invasion, Perowne would have lost and the absurdity of his liberal humanism been glaringly exposed. Just after the fall of Baghdad, polls suggested that Iraqis were evenly divided on whether or not they felt liberated or occupied. By the time the USA pretended to hand over power in the summer of 2004, only 2 per cent of Arab Iraqis supported the occupation. As for the free press – Al Jazeera was booted out by the Vichy regime, anxious to stifle an independent Arab media outlet loathed by the US government.

It’s noticeable that McEwan’s position has shifted from that which he put forward in January 2003. “I was against it,” he now asserts, when asked about the war (interview with Boyd Tonkin, The Independent, 28 January 2005). But of course, “not as passionately as many friends and colleagues.” McEwan now claims that Daisy expresses his anti-war feelings just as much as Perowne embodies his own ambivalence, but Daisy’s assertion that “there’s nothing linking Iraq to nine eleven, or to Al-Qaeda generally, and no really scary evidence of WMD” (p. 191) is at odds with McEwan’s former belief that it did not seem “outlandish, the possibility of Saddam Hussein passing on weapons of mass destruction to the enemy of his enemies.”

In January 2003 McEwan defended Blair from the charge that he was Bush’s poodle and saw him as a committed humanitarian. Disillusionment has evidently now set in. McEwan’s shift of position seems to me to parallel that of Greg Dyke, who confides, “I understand what Gordon Brown means when he says he finds it difficult to believe a word that Blair says, which is odd because I didn’t feel that a year ago when I was forced out. It was the publication last summer of the Butler report which changed everything for me.” (Independent, 28 January 2005, p. 9)

In Saturday McEwan twice mocks Blair. There’s a reference to the science of the human smile: “In the smile of a self-conscious liar certain muscle groups in the face are not activated” but “the first and best unconscious move of a dedicated liar is to persuade himself he’s sincere. And once he’s sincere, all deception vanishes.”

Reprising that episode when the protagonist of ‘The Child in Time’ has a surreal encounter with Margaret Thatcher, Perowne remembers a comic encounter with Blair at the opening party for the Tate Modern gallery. Blair, we learn, mistook him for a painter and, when told of his error, saved face by continuing to congratulate him on his artistry. McEwan, I think we can safely conclude, like Greg Dyke, feels very, very let down by Tony and no longer trusts him.

That sense of disappointment is transmitted in the scene where Perowne sees Blair on TV:

“The Prime Minister is giving his Glasgow speech. Perowne touches the control in time to hear him say that the number of marchers today has been exceeded by the number of deaths caused by Saddam. A clever point, the only case to make, but it should have been made from the start. Too late now. After Blix it looks tactical.” (p. 178)

It is characteristic of the narrative that these cloudy sentences are never subjected to irony or sceptical enquiry. In what sense is it “A clever point” or “the only case to make”? Far from being “clever” isn’t it just meaningless? Isn’t it as fatuous as saying something like, “No matter how many people in Britain went to services of remembrance on Holocaust Memorial Day that will still be less than the number of people who died in the death camps!” No mention, either, of the fact that Blair brought forward his speech by several hours, in order to dodge thousands of Scottish demonstrators who were going to march on the venue where he was due to speak.

*

There is nothing in Saturday that seems likely seriously to damage McEwan’s popularity with his American readership. The novel is prefaced by a quote from Saul Bellow’s ‘Herzog'. Bellow is another liberal realist whose trajectory over the years has been from fiery young lefty to elderly reactionary. Ironically, the language of the Bellow epigraph is far more sparky, animated and stylistically daring than anything in the buttoned-up, over-wrought, mannered prose of Saturday. At times McEwan’s style is fussily Edwardian. Whereas the average realist novelist would write “at the end of the week he was unusually tired”, McEwan writes “he finished the week in a state of unusual depletion” (p. 5).

The ravages of US foreign policy never feature in Perowne’s consciousness, other than in the vaguest of ways. There are harsh words for torture regimes, but Israel is not included in the list. The nearest thing to criticism is when Daisy says:

‘You hate Saddam, but he’s a creation of the Americans. They backed him, and armed him.’

‘Yes, and the French, and Russians and British did too. A big mistake. The Iraqis were betrayed, especially in 1991 when they were encouraged to rise against the Ba’athists who cut them down. This could be a chance to put that right.’

‘So you’re for the war?’

‘I’m not for any war. But this one could be the lesser evil. In five years time we’ll know.’ (p. 187)

The only American in the novel is Jay Strauss, a big, tough, warm-hearted consultant anaesthetist. A patient, a stroppy black 14 year old girl from Brixton, vexes the hospital staff by her difficult behaviour. She’s a bully. When a nurse is reduced to tears only tough Jay Strauss can deal with the situation. In the face of his tough, firm no-nonsense attitude the girl’s hostility collapses and by the end of the novel, her operation a success, she wants to become a brain surgeon herself. (There’s a sub-text there, oh yes. But you can work it out for yourself.)

Strauss is also a brilliant anaesthetist: “As far as Henry is concerned, Jay is the key to the success of his firm.” (p. 101) Perowne’s ‘firm’ is his team. And this is a novel in part about having a good team spirit. Perowne and Strauss play squash (for 16 pages – a tour de force of narrative description or a bloody tedious read - you decide). They both get ratty about losing, but at work they rise above such petty irritability, as good professionals should. (Team spirit, I’m afraid, always makes me think of that brilliant moment at the end of the movie I’ll Never Forget Whatshisname where surly Oliver Reed screams that it was team spirit that gave us the Nazi death camps.)

Strauss is also pro-war: “Iraq is a rotten state, a natural ally of terrorists, bound to cause mischief at some point and may as well be taken out now while the US military is feeling perky after Afghanistan. And by taken out, he insists that he means liberated and democratised. The USA has to atone for its previous disastrous policies – at the very least it owes this to the Iraqi people.” (p. 100)

War for the purest motives, you see – a position not really any different to Perowne’s, even though McEwan terminates this paragraph with the sentence: “Whenever he talks to Jay, Henry finds himself tending towards the anti-war camp.”

“Tending towards” is a revealing way of putting it – this is a mind that seems to flutter towards one political position, then to flutter to its opposite, but in actuality stays firmly lodged in the centre right, aligning itself with the argument that the forthcoming war on Iraq has a sound humanitarian basis and will be good for the Iraqi people. And throughout this novel there is a fastidious disdain for those dimly glimpsed, marginalised 2 million marchers.

A minor character, Rodney Browne, a neurosurgical registrar, is also against the war, but when Jay Strauss “has been holding forth on the necessity of the coming war” Browne is “reluctant to voice his pacifist views for fear of being taken apart”. (p. 248)

But this suggestion of balance is all a sleight of hand. The argument that it might be a war for oil is mentioned only in passing. The thrust of the novel is to make the reader sympathise with Perowne, the decent, hard-working, agonized, ambivalent liberal.

The climax of the novel subverts the pacifism of Daisy and her brother. When Baxter and an associate force their way into the house they force Daisy to strip naked before them. She is threatened with rape. In the face of violence the representatives of civilized decency are themselves forced to resort to violence, and Perowne and Theo end up fighting Baxter and throwing him down the stairs. It’s a parable of sorts. At the height of the terror Perowne hears the police helicopter as it monitors the dispersal of the protesters from Hyde Park. It’s a moment calculated to appeal to Daily Mail readers – police resources taken up by a left-wing demonstration while an affluent middle-class household is broken into by a pair of violent, terrifying working class thugs with knives.

In a twist of fate (one of the many implausible aspects of a supposedly realistic narrative), Perowne is asked to operate on Baxter, who has suffered a serious head injury. Perowne does so, successfully, afterwards deciding that he will decide not to press charges, even though Baxter has broken Perowne’s father-in-law’s nose, slashed Perowne’s expensive Knoll sofa, held a knife to his wife’s throat, and forced his daughter to strip, then threatened her with rape. Perowne represents decency and liberal humanity; Baxter has a rare genetic condition and is biologically doomed – that is punishment enough, he decides.

On his way to the hospital Perowne encounters the cleaning-up operation after the great march:

“the debris has a certain archaeological interest – a Not in My Name with a broken stalk lies among polystyrene cups and abandoned hamburgers and pristine fliers for the British Association of Muslims. On a pile he steps round are a slab of pizza with pineapple slices, beer cans in a tartan motif, a denim jacket, empty milk cartons and three unopened tins of sweetcorn.” (p. 243)

This is the final mention of the march in the novel (which continues for another 36 pages), and it takes us back to Perowne’s encounter with the marchers in Chapter Two:

‘“Not in My Name” goes past a dozen times. Its cloying self-regard suggests a bright new world of protest, with the fussy consumers of shampoos and soft drinks demanding to feel good, or nice… A placard of one of the organizing groups goes by — the British Association of Muslims. Henry remembers that outfit well. It explained recently in its newspaper that apostasy from Islam was an offence punishable by death.” (p. 72)

Perowne’s final encounter with the detritus of the march reinforces his earlier perception of these gullible, muddle-headed peaceniks as self-centred consumers, enjoying the good life of western capitalism while cheerily aligning themselves with the dark force of Islamic extremism. Perowne, in other words, is right all along. (And for Daily Mail readers there is, I suppose, the added bonus that these lefty anti-war marchers are a scruffy lot who drop tons of litter.)

This is more sleight of hand, of course. Those who take the trouble to travel to central London and march against the war are self-centred consumers. Those who spend that Saturday doing other things like playing squash or shopping or playing their guitars are not self-centred but superior creatures possessed of a more complex inner life.

The final 34 pages of the novel describe Perowne’s operation on Baxter and his return home, where he has sex with his wife for the second time that day and finally goes to sleep. The biggest protest march in British history is simply erased from existence – a non-event, really, remote from the central drama of Henry Perowne’s mind and life.

*

In reality Saturday is far less about 15 February 2003 than about 11 September 2001. From his published comments, it appears that McEwan experienced that event as something of a personal trauma. He subscribes to the US-centric ‘world was changed forever by 9/11’ thesis. After 9/11 McEwan abandoned writing fiction for six months. No public event in his writing career had touched him so deeply. The violent death of 3000 people, mostly Americans, was a horror much greater than all those millions upon millions who died from malnutrition, disease, torture, massacre or war in the 27 years of his career as a published writer. But then they died off-camera, and almost none of them were white middle class professionals and they were just statistics, not individuals with life stories that interested the media.

What you don’t get in Saturday and what you’ll never get in McEwan’s fiction is the kind of perception of the main character in Iain Banks’s novel ‘Dead Air’ (2002), who comments:

“every twenty-four hours about thirty-four thousand children die in the world from the effects of poverty; from malnutrition and disease, basically. Thirty-four thousand, from a world, a world-society, that could feed and clothe and treat them all, with a workably different allocation of resources. Meanwhile, the latest estimate is that two-thousand eight hundred people died in the Twin Towers, so it’s like that image, that ghastly, grey-billowing, double-barrelled fall, repeated twelve times every single fucking day; twenty-four towers, one per hour, throughout each day and night. Full of children.”

McEwan’s trauma was, I suspect, partly the shock of seeing something that was personally important under attack. “From the vantage point of the Brooklyn Heights, we saw Lower Manhattan disappear into dust,” he wrote in The Guardian on 12 September 2001, from the viewpoint of someone familiar with New York. “Yesterday afternoon, for a dreamlike, immeasurable period, the appearance was of total war, and of the world's mightiest empire in ruins.” There was also, perhaps, the disturbing thought that it could so easily have been him on one of those planes, “crouching in the brushed-steel lavatory at the rear of the plane, whispering a final message”.

McEwan complained that the hijackers lacked empathy for their victims:

“If the hijackers had been able to imagine themselves into the thoughts and feelings of the passengers, they would have been unable to proceed. It is hard to be cruel once you permit yourself to enter the mind of your victim. Imagining what it is like to be someone other than yourself is at the core of our humanity. It is the essence of compassion, and it is the beginning of morality.” (The Guardian, 15 September 2001)

This is perfectly true. But it is a point that could also be made against members of the US army or RAF bomber pilots.

McEwan asserted that, “The hijackers used fanatical certainty, misplaced religious faith, and dehumanising hatred to purge themselves of the human instinct for empathy. Among their crimes was a failure of the imagination.”

In one sense, he was extraordinarily wrong. The hijackers had the perceptions of literary critics. They did not lack imagination. They were interested in symbolism. The pentagon represented the US military war machine and the twin towers represented US commerce. There was an additional cultural spin-off. What the hijackers did by demolishing the twin towers was to mock American cultural hegemony in a curiously deadly way. Suddenly all those cinematic images of New York became an ironic comment on their own complacent self-regard. The twin towers are everywhere in that hegemonic imagery. The re-make of King Kong, the Hollywood Godzilla, old episodes of Friends, innumerable Hollywood movies, Spielberg’s AI, Schwarzenegger’s End of Days – the twin towers are always there, somewhere. And, seeing them after 9/11, you can’t help thinking of what is to come. History intrudes on fiction. 9/11 re-imagined the past. It mocked the staple convention of the disaster movie – a good American always, at the last moment, prevents disaster. 9/11 mocked America’s image of the future. Hollywood imagined the twin towers would be there forever. It was wrong. In that most visual of cultures, partly because of the accident of a fine, clear sunlit day, partly because of the presence of a French film crew, 9/11 supplied a visual feast.

Saturday is a parable of the ideas that McEwan put forward in his two Guardian pieces on 9/11. Perowne’s day begins with him looking out of the window of his central London home and seeing a plane on fire coming in to Heathrow. He wonders if it is another 9/11 style hijacking. That possibility evaporates. Instead a worse, more personal crisis follows later in the day. The knife wielding Baxter and his accomplice who burst in and threaten Perowne, his wife, his daughter, his son, and his father-in-law, represent a version of the 9/11 hijackers. Baxter is like a suicidal terrorist: Perowne identifies him as “a man who believes he has no future and is therefore free of consequences.” (p. 210)

Baxter is, metaphorically, an Arab extremist. His genetic defect is also, arguably, a displaced version of that popular reactionary concept, the criminal gene (which is paralleled by the poverty gene and the homelessness gene, and all those other bogus genes which offer a soothing pseudo-scientific explanation for the consequences of the inequalities of capitalist society).

But what stops a dangerous and dreadful situation – the impending rape of Daisy - is the benign force of the human imagination. Baxter engages in a conversation with his intended victim (a plot device straight out of James Bond – the villain unfolds his fiendish plans but the delay this involves provides a way out of an apparently hopeless situation). He orders her to read from her book of poems. In a state of shock Daisy is able only to recite an old favourite, Matthew Arnold’s ‘Dover Beach’. Baxter likes it so much he asks her to recite it again, then sobs, ‘It’s beautiful’, adding ‘It makes me think of where I grew up.’ (p. 222) So Baxter, unlike the 9/11 hijackers, does not lack imagination. He is redeemable. He loses all interest in raping Daisy. He isn’t an Arab after all!

The message of the poem ‘Dover Beach’ is also the message of Saturday. The world is a truly dreadful place full of nastiness and very, very confusing. God is dead. Nothing makes sense any more. Therefore retreat into the personal and ‘be true’ to your lover. Or as Lennon and McCartney put it: All you need is love.

Saturday, then, a novel about anxiety. It is in the great tradition of the nineteenth century bourgeois liberal novel, when affluent, talented writers were terrified of the idea that their whole way of life was under threat by dark, destructive forces. Back then the threat was from working-class radicalism. The image of workers gathered together for political purposes sent a shiver down the spine of novelists like George Eliot, whose vision of the proletariat was that of a terrifying mob, a “mass of wild chaotic desires and impulses”. Dickens in Hard Times suggested that those who suffered under capitalism should respond with dignified restraint, in heroic isolation. Nothing as vulgar as politics should intrude. Henry James in The Princess Casamassima proposed that the major motive of political radicals was envy and suggested that the only decent destiny of a thinking militant was to see through the sham of revolutionary politics and commit suicide. (Thanks, Henry.) The actions of Al-Qaeda have, alas, soured the agreeable quality of suicide as an apt political destiny, and even when liberals with a capital ‘L’ do something so liberal as to empathise with the state of mind of Palestinians who detonate themselves beside Israelis, they quickly find, as Jenny Tonge did, that the liberal – or Liberal - imagination is suddenly a very narrow and slyly calculating one.

Perowne is an anxious man. “He bought Fred Halliday’s book”, we’re told (p. 32) and having read it frets that “the New York attacks precipitated a global crisis that would, if we were lucky, take a hundred years to resolve.” Frightening stuff, eh? Later Perowne convinces himself that the crisis will fade, like all the ones before it. But that still leaves him with lots of other anxieties. But these are the anxieties of an affluent professional enjoying a very agreeable lifestyle. He lives in a large house in central London. He drives a Mercedes which he houses in a nearby mews. He enjoys fine food and wine. What haunts him is the threat of Islamic extremism. He fears another 9/11 style hijacking. He worries about the shoe bomber. He worries that there will be a major terrorist attack on his city. And the problem is ideology, which makes fanatics do terrible things. Perowne concludes (much in the manner of George Eliot): “No more big ideas. The world must improve, if at all, by tiny steps.” (p. 74) Perowne even has an example. The design of kettles has much improved over the years: “The world should take note: not everything is getting worse.” (p. 69)

Perowne is not entirely McEwan. His views on literature are different, and there are various jokes for the literati. Perowne doesn’t like McEwan’s The Child in Time or Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses. His poet father-in-law is envious of McEwan’s great friend Craig Raine. He is not well up on his Matthew Arnold. If Perowne has one shortcoming it is that his grasp of literature is weak and he does not read novels with a proper sense of appreciation – an irony which flatters the ego of the reader of Saturday.

The BBC has treated the publication of Saturday as a newsworthy event. A feature on the ‘Today’ programme (February 1st) called it “Ulysses-like”. Well, yes, it’s set on a single day but apart from that it is entirely unlike Joyce’s novel, which is massively radical and ambitious in its language and form. ‘Ulysses’ is a difficult, stubborn, challenging read.

Saturday is the kind of novel Joyce set out to annihilate. It has solid characters, a suspenseful plot and uses the conventions of realism to portray an affluent middle class social world. As a product it is easy reading, shiny, highly processed. It presents itself (as realism always does) as a transparent window through which to observe a real world. Its artifice and partiality goes as unacknowledged as the shared values of a BBC news team. It emanates the stale authority of omniscience, treating its readers to little nuggets of wisdom. Here’s a good example of the style: “Sex is a different medium, refracting time and sense, a biological hyperspace as remote from conscious existence as dreams, or as water is from air.” (p. 51) The reader is required to nod wisely in agreement at this profundity.

Apparently McEwan wants us to think that Perowne’s fence-sitting on the war is akin to “Hamlet-like indecision” – a cultural analogy which strikes me as preposterous. Hamlet had to decide if the ghost was a demon or a truth-teller, if his father had really been murdered, and whether or not to kill the king – rather substantial personal anxieties, with potentially lethal consequences. Perowne’s banal equivocations about the rights and wrongs of war on Iraq have no personal consequences at all.

Equivocation – havng your cake and eating it – is a noticeable narrative strategy in Saturday. Perowne owns a Mercedes (as does, or did, McEwan – I have a hazy memory of reading some years ago a profile of the novelist which referred to his Mercedes parked in the drive of his Oxford home). Perowne has a memory of seeing his parked car “a hundred yards away, parked at an angle on a rise of the track, picked out in soft light against a backdrop of birch, flowering heather and thunderous black sky” – then adds: “the realisation of an ad man’s vision”. But though the description is lightly mocked, it is not seriously challenged. Seeing his car like this, Perowne experiences “a gentle, swooning joy of possession” (p. 76).

Boyd Tonkin complains that books as a cultural form don’t get enough attention from TV (Independent, 4 February 2005), but he adds:

“On the credit side, an item about Ian McEwan’s Saturday made the principal BBC evening news this Monday. This was not because it grabbed a gong or stirred a quarrel or triggered a fatwa, but simply because a world-ranking novelist had brought out a landmark work.”

But I can’t think of anything more characteristic of the news values of the BBC than that it should choose to privilege the publication of ‘Saturday’ as deserving of respectful attention as ‘news’. Saturday is ideologically kin to those values. It’s a novel which adopts a reverent attitude to affluence. A Mercedes is a lovely car. Squash is a splendid game. It’s nice to have a big house in central London. A war on Iraq will get rid of a disgusting torture regime.

Saturday is a novel for liberals who didn’t go on the march (and I have yet to read a review of the novel or hear or watch a discussion of it that engages with the question of whether or not the critic participated in that march. My guess is that probably not a single one of them did.) It’s a bourgeois novel in the sense that it celebrates a bourgeois life style and worries about the threats to that way of life. At the end of the novel Perowne stands at the window, back where his day began:

“A hundred years ago, a middle-aged doctor standing at this window in his silk dressing gown, less than two hours before a winter’s dawn, might have pondered the new century’s future. February 1903. You might envy this Edwardian gent all he didn’t yet know. If he had young boys, he could lose them within a dozen years, at the Somme. And what was their body count, Hitler, Stalin, Mao? Fifty million, a hundred? If you described the hell that lay ahead, if you warned him, the good doctor – an affable product of prosperity and decades of peace – would not believe you. Beware the utopianists, zealous men certain of the path to an ideal social order. Here they are again, totalitarians in different form, still scattered and weak, but growing, and angry, and thirsty for another mass killing. A hundred years to resolve. But this may be an indulgence, an idle, overblown fantasy, a night-thought about a passing disturbance that time and good sense will settle and rearrange.” (pp. 276-7)

As usual, McEwan has his cake and eats it. He equivocates. But these parallel nightmare visions are questionable on other grounds than that the second, twenty-first century one might not come to pass. If the twentieth century was hell, what was the nineteenth century? Paradise? What was the body count of the British Empire? And if Hitler, Stalin and Mao racked up 100 million dead, what about the 17 million who die every year on our planet from disease, malnutrition, filthy water and suchlike? What’s the body count resulting from US foreign policy? If it was hell in the Gulags or the death camps, was it more agreeable being a Kikuyu in Kenya in the 1950s? As for those "zealous men" of the twenty-first century, what is it exactly that makes them "angry"? Perowne is supposed to represent civilised values but one of the many absences from his sensitive conscience is global warming and the link with personal consumption, car driving, air travel and all those other ingredients of an agreeable middle class lifestyle.

But that’s quite enough from me. I finish this week in a state of unusual depletion. I’m off for another listen to that timeless classic, Phil Ochs singing ‘Love Me, I’m a Liberal.’

#ian mcewan#saturday#bourgeois novel#literary fiction#book review#critical review#iraq war#middle class fiction#middle class ideology#anti-war protests#ellis sharp#barbaric document#centrism#liberalism#blogspot#elder days of blogs

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

rough day

#em draws stuff#the flight of the heron#ewen cameron#blood#got asked what happened to his face in the last drawing I did of him and thought I'd answer visually#the sharp-eyed among you may notice that he picks up a cheek scar in art that takes place post-culloden#saturday's drawing is set while he's still in recovery mode so I thought I'd take the opportunity to add a little detail there#I've seen (forgotten exactly where) reference to black silk being used in an early form of more adhesive bandage about that time#and while I'm not precisely sure on what it would have looked like I found it kind of aesthetically neat#and speaking of aesthetically neat boy did I ever get carried away with the background flourish on this one!#actually remembered to look up your weird-shaped european oak leaves this time so I hope I've got that correct at least...

20 notes

·

View notes