#south american insects

Text

What's this? A sabertooth longhorn beetle (Macrodontia cervicornis), which is native to South American rainforests. Bizarre and beautiful, yes?

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Common Drone Fly (Eristalis tenax)

Family: Hoverfly Family (Syrphidae)

IUCN Conservation Status: Least Concern

Present and abundant on every continent except Antarctica, the Common Drone Fly is one of several hoverfly species that exhibit Batesian mimicry (a form of mimicry in which a harmless species has evolved to mimic the appearance of a toxic or otherwise dangerous species,) with its fluffy body and yellow-and-black striped abdomen giving it a bee-like appearance that deters most would-be predators despite lacking any real defensive abilities itself - upon closer inspection, it can be easily distinguished from a true bee owing to its thick body (bees have a narrow "waist" between their thorax and abdomen,) short, stubby antennae (bees generally have longer, flexible antennae) and wings (bees have 4 overlapping wings, while flies have only two wings.) Feeding on nectar and pollen, males of this species claim small flower-filled areas as their territories and guard them fiercely, hovering in mid-air to survey their surroundings and chasing off any similarly-sized insects that come close. Females travel between these territories searching for food and mates, and after mating they lay clutches of sticky oval-shaped eggs near bodies of water; the larvae, known as rat-tailed maggots, are aquatic and feed on detritus and bacteria, breathing air through an extremely long tail-like structure that extends from their abdomen. After reaching a suitable size and age the larvae crawl onto land and pupate in sheltered areas, and upon reaching adulthood they may live for several years, hibernating in rocky cracks or rotting wood to survive the winter.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Image Source: https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/55719-Eristalis-tenax

#Common Drone Fly#drone fly#fly#flies#hoverfly#insect#insects#zoology#biology#entomology#animal#animals#African wildlife#european wildlife#Asian wildlife#Australian wildlife#North American wildlife#South American wildlife#cosmopolitan wildlife#wildlife

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lady Granville’s beetle parure and case, 1884–85.

Lady Granville’s beetle parure and case. Photograph: British Museum, London.

The Victorian obsession with colour led to some disturbing embellishment of natural wonders. This tiara, from the British Museum’s collection, contains the iridescent bodies of 46 South American weevils, gifted by the Portuguese ambassador to the British foreign secretary, Lord Granville.

#insects#beetles#jewelry#victorian#parure#british museum#london#tiara#south american weevil#lord granville#lady granville#insect jewelry#19th century

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

When people get weirded out by the most basic ass normal Chinese food and I’m like *laughs in Yunnan* they ain’t seen nothing yet

#Drop the Americans off in the south we’ll deal with them#Feeding them the hundred-insect feast and laughing evilly

1 note

·

View note

Text

I’ve found several cicadas out and about today, the screaming shall soon commence.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Interesting Wasps Were Imported to Weed Out Mole Crickets

Interesting Wasps Were Imported to Weed Out Mole Crickets shows readers some Larra bicolor wasps. These wasps were imported from South America to help control an invasive species of mole crickets.

Mole Cricket Hunter

Thursday afternoon was absolutely gorgeous here. The weather was unusually cool at about 75 degrees, the sun was out, and it wasn’t raining, so I absolutely had to take a short walk outside. My time was limited so I didn’t go to Gothe or any of the trails. I went into my own yard. It’s always surprising what you can find in your own yard if you keep your eyes open. In my…

View On WordPress

#bicolored insects#bicolored wasps#colorful insects#colorful wasps#Florida insects#Florida wasps#insect photographs#insect photography#insects#Larra bicolor#mole cricket hunters#non-native wasps#nonaggressive wasps#parasitic insects#parasitic wasps#parasitoids#photography#South American wasps#useful insects#useful wasps#wasp photographs#wasp photography#wasps

0 notes

Text

Animal of the Day!

Brazilian Treehopper (Bocydium globulare)

(Photo in Public Domain)

Conservation Status- Unlisted

Habitat- Africa; Asia; North American; South America; Australia

Size (Weight/Length)- 6 mm

Diet- Sap

Cool Facts- No, those aren’t eyes. The Brazilian treehopper has a distinct protrusion sticking out of their thorax called a helmet. Scientists don’t fully understand why the insects grow these outgrowths, but it could be for a bizarre form of camouflage or dissuading predation. Despite being able to fly, the treehoppers only do so when startled. They prefer to crawl on the underside of leaves as they search for sap. Females lay their eggs directly inside the tissue of a leaf and after a few weeks a nymph emerges. After only a month of life, the Brazilian treehopper is ready to have offspring of their own.

Rating- 12/10 (Of the 3,270 treehopper species, this may be the weirdest.)

#animal of the day#animals#insects#treehopper#friday#november 3#brazilian treehopper#biology#science#conservation#the more you know#cw: insects

517 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any cool facts about Missouri wildlife?

I'd love to share something with my Midwestern friends, and thank you for always updating this blog!

I don't know if i have any Missouri animal facts per se... but I can share some of the state symbols with everyone.

We moved around a lot when we first came to the U.S. and we lived briefly in Kansas City. I have great memories of going to the Ozarks at Christmas time (near Lake of the Ozarks). I specifically remember following woodpeckers and deer around the forest in the snow.

SOME MISSOURI STATE SYMBOLS:

STATE BIRD: Eastern Bluebird (Sialia sialis), family Turdidae, order Passeriformes, found across much of the central and Eastern U.S., SE Canada, and NW Mexico

Changes in land use lead to drastic declines in Eastern Bluebirds after the early 1900s. They have recovered in many places, due to "bluebird trails", reestablishing appropriate habitat and nest box campaigns for public and private property.

Find out more: NestWatch | Eastern Bluebird - NestWatch

Blue birds are in the thrush family, Turdidae, along with American Robins.

They eat mainly worms, insects, and other small invertebrates (but also take berries for part of the year).

Bluebirds are cavity nesters, nesting in tree holes usually, but will readily take to properly constructed and placed nest boxes.

Males (pictured) are brighter blue, and females are a more muted and faded blue or bluish gray.

photograph by Keith Kennedy

STATE AQUATIC ANIMAL: American Paddlefish (Polyodon spathula), family Polyodontidae, order Acipenseriformes, found in various parts of the Mississippi River basin

This species is the only member of this family that still exists. They are most closely related to sturgeons. This order, Acipenseriformes, is considered one of the most evolutionarily primitive groups of ray finned fishes.

They do not have scales, and their skeleton is mostly cartilaginous.

They are filter feeders. Their heads and rostrums are covered with thousands of sensory receptors, which help them locate zooplankton swarms.

They are considered "vulnerable" due to overfishing, habitat degradation and destruction, and pollution.

photograph via: US Fish & Wildlife Service

STATE ENDANGERED ANIMAL: Eastern Hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis), family Cryptobranchidae, eastern United States

The largest salamander in the Americas, it grows to a total maximum length of up to 40 cm (15.7 in).

Though nationally it is considered to be just "vulnerable", in some states (like Missouri), it is "endangered".

photograph by Mark Tegges

STATE REPTILE: Three-toed Box Turtle (Terrapene triunguis), family Emydidae, found in the South-central and Southeastern U.S.

This specie shas been considered to be a subspecies of the Eastern Box Turtle, T. carolina (and still is by some herpetologists).

These turtles are terrestrial, but are not closely related to tortoises. They are in the same family as aquatic sliders, pond turtles, cooters, map turtles, and painted turtles.

photograph by Noppadol Paothong

STATE FISH: Channel Catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), family Ictaluridae, order Siluriformes, found in freshwater habitats in the eastern and southern US, southern Canada, and northern Mexico

They are widely caught, and have been introduced into waterways in other parts of North America and around the world. (In some places they are considered an invasive species).

photograph via: Missouri Dept. of Conservation

photograph by Brian.gratwicke

#Acipenseriformes#paddlefish#fish#ichthyology#box turtle turtle reptile#herpetology#bluebird#thrush#bird#ornithology#north america#hellbender#salamander#amphibian#animals#nature#catfish

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jungle Fantasies (18+)

2007!Leonardo x reader

Takes place before Leo becomes the Ghost of the Jungle, and before he decides to stay in South America. Leo has been in the jungle for a few weeks and just can’t stop thinking about you.

Warnings: Masturbation, descriptions of sex, gradually getting more and more desperate in nature, spelling.

------------------------------

Leonardo walked alone through the heart of the South American jungle, surrounded by the symphony of chirping insects and rustling leaves. The humid air clung to him like a second skin as he moved through the forest, the rhythmic swish of his katana cutting through the stillness of the night and the plants in his way, as he made his way to his hideout.

The jungles of South America offered a stark contrast to the urban landscape of New York City, where you, his constant muse, navigated the bustling streets. As Leonardo honed his skills under the dense canopy that made up forest above his head, he couldn't escape the persistent thoughts of you that tugged at the corners of his mind. It had only been a few weeks and he already missed you as if it had been years.

In the daytime, as the sun filtered through the lush foliage, Leonardo's training sessions were filled with the echoing memories of your laughter and the gentle brush of your fingers against his skin. The longing for the simple joys of holding you close and feeling the warmth of your embrace lingered in his every movement. It was usually with his longing he would write his letters to you. Telling you how much he was thinking about you, and how he was already dreaming of the day he would be home with you again.

But nighttime brought with it a different kind of struggle. Alone in the vast wilderness, Leonardo's thoughts took a more suggestive turn. The distant sounds of nocturnal creatures became a backdrop to his fantasies, where the intimacy he craved with you played out in his mind. And as he let those fantasies play out in his mind, he felt the growing need and longing for you. Not just in his heart and soul, but in his loins. A need that had been growing ever since he first arrived in South America, causing conflict in his mind. It was a battle between his commitment to training and the yearning for the physical connection he had left behind. It was in these moments he thought of abandoning his training, just so he could spend one more night in your bed, feeling you hug every inch of him. But Leo stayed in the jungle, determined to become the leader his brothers needed.

To cope with the loneliness and in an attempt to suppress his needs, Leonardo began to document his thoughts and feelings in a worn journal. Each page was a canvas for his emotions, a testament to the dichotomy of his desires. He sketched images of the jungle at the corners of his letters, just so he could somehow share the jungle and its wildlife with you. You in turn would do the same in your letters to him, adding small sketches of your life. But none of it stopped Leo’s longing to be with you again. It only made it stronger.

One day, as he sat on a moss-covered rock beneath a waterfall, Leonardo traced the flow of the waterfall at the bottom of his newest letter to you. The cascading water mirrored the rush of emotions within him, the sound a soothing melody that seemed to carry the whispers of your name through the dense foliage.

One evening, as the sun dipped below the horizon, casting hues of orange and pink across the sky, Leonardo retreated to the cave he had been calling home for the last few weeks. The makeshift shelter, hidden among the roots of ancient trees, became a sanctuary where his thoughts and emotions unraveled in the quiet solitude.

Inside the cave, the air was cool and damp, and the distant sounds of the jungle served as a gentle lullaby. Lying on a bed of moss, Leonardo stared up at the patch of sky visible through the entrance. The twinkling stars seemed to reflect the countless thoughts that danced in his mind, each one a testament to his longing for you.

As fatigue settled into his muscles, Leonardo closed his eyes, attempting to surrender to the embrace of sleep. However, the tranquility of the jungle only heightened his awareness of the emptiness beside him. His thoughts circled back to the intimate moments he had left behind - the shared laughter, the stolen glances, and the simple joy of having you by his side.

In the darkness of the cave, Leonardo's mind painted vivid scenes of cuddling with you. He could almost feel the softness of your presence, your warmth seeping into every crevice of his being. The imaginary touch of your fingers tracing patterns on his shell brought a comforting ache to his heart.

A sigh escaped Leonardo's lips as he yearned for the weight of your head on his plastron, the closeness that transcended the physical and delved into the realm of emotional intimacy. His mind danced on the edge of fantasy, exploring the idea of shared warmth beneath the celestial canvas of a starlit night. The gentle rise and fall of your breath and the soothing cadence of your heartbeat. Leonardo's mind drifted to the gentle caress of your fingers along the edges of his shell, a sensation that lingered in his muscle memory. As he lay on the mossy surface, thoughts of cuddling with you took on a more nuanced flavor. Leonardo envisioned the curve of your body fitting seamlessly against his, the space between you shrinking until it was nonexistent.

As Leo’s thoughts played out, he felt the need in his cloaca grow even further. Frustrated, he ran his hands over his face before casting a glance down to his crutch. Pulsating, aching to drop. How Leo wished you were there with him. Outside of his mating season, he was not used to this aching feeling. Hell, he had not had a painful mating season ever since he started dating you…

Leo closed his eyes, once again imagining you were cuddled close against his side, already naked from activities he only wished the two of you had been up to. He imagined the need in your eyes, as he pictured your hand sliding down his plastron instead of his own. As his hand got closer to his cloaca he felt himself drop, just like he had promised himself he would only drop for you.

In his mind it was your hand that held on to his erection as your lips met his. He felt the pre cum on his head, using it lather up his hand, before ever so slowly moving his hand up and down his rod. He could see and hear you in front of him, whispering and telling him how much you had missed him, all while your hand started working faster on him. He imagined that his own hand, the one that had been wrapped around you holding you to his side, made its way down your back, grabbing your ass before sliding even further, until he found your wet entrance. Your moans were clear in his mind as he played with your soaked slit, before pushing a finger into you.

You moaned out, your face falling to his shoulder and your breast pressed against his plastron. Fuck how he missed that feeling. The thought only made his hand work faster on his member. He bit his lip, holding back a moan, dreaming of your lips making their way down his front, all while he still had his finger pumping into your pussy. He could still remember the sound from last time he did so to you.

Leo buckled his hip at the thought of his member in your mouth. “Fuck…”, he breathed out, wishing he could hold onto your head so he could thrust into your mouth. If you were there with him, he would have taken you over and over again, every single day.

Leonardo turned over in the moss bed, closing his eyes, imagining you were laying beneath him, begging for him to bury his cock deep inside of you. Normally he would tease you with it, rubbing his head against your clit, even eat you out til you were almost screaming for him to fuck you. But there, alone in the cave, Leo was the one that was about to scream for you. Frantically he grinded his hips against his makeshift bed, chasing the release he had been suppressing for so long.

The moss felt nothing like you, but at that moment Leo did not care. He just wanted to cum with the picture of you in his mind, sprawled out underneath him, needing him just as much as he needed you.

Normally Leo would be whispering all sorts of dirty things to you, like how good you were taking him or what a good girl you were for him. But that was not what Leo did in that cave. He was a moaning, whimpering mess, calling out your name over and over again as he chased his high.

Leo’s head fell to where he imagined your neck would be, lightly biting onto your skin to muffle his moans. But instead of the skin of your neck, it was the skin of his upper arm.

As Leo felt his high coming closer, he imagined you holding on to his shoulders, crying out as you were about to cum. Leo felt his head spin as he was about to cum, dreaming of your high pitch moans in his ear.

Leo came unto his moss bed moaning out your name, imagining you tighten around him as you came yourself. Your expression of pleasure as clear in his head as it was the night he gave you a proper goodbye.

With shaking breath Leo turned onto his back, staring up at the cave ceiling. His member softened ever so slowly as he tried calming his breath. Leo closed his eyes once more. Normally this would be the time for aftercare. Either you and Leo would take a shower together, or you would cuddle close until you fell asleep. But in the cold damp cave none of those things felt right without you. Without your soft warm body next to him, calming down from the pleasure he had just given you.

Leo tugged himself away, getting up to do a quick cleaning of his moss bed, before getting ready to sleep for the night. As sleep claimed him, he couldn’t stop himself from dreaming about you one last time. He pictured you next to him, already asleep, hair a mess, your cheeks pink and your face at peace. The image of you nestled in the crook of his arm became the anchor that tethered him to the promise of a future where the distance would be nothing more than a fleeting memory. The day he had finished his training and would come home to you again.

#tmnt#teenage mutant ninja turtles#tmnt leonardo#tmnt x y/n#tmnt x reader#tmnt x you#tmnt donatello#tmnt raphael#tmnt michelangelo#tmnt raph#tmnt leo#tmnt donnie#tmnt mikey#tmnt 2007#tmnt 2k7#tmnt 2007 x reader#tmnt 2k7 x reader#tmnt 2007 leonardo#tmnt 2007 leo#tmnt 2007 leonardo x reader#tmnt 2007 leo x reader#tmnt smut#tmnt leonardo smut#tmtn leo x reader#tmnt leonardo x reader#leonardo tmnt#leonardo#donatello#michelangelo#raphael

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quechuavis van Els et al., 2023 (new genus)

(An individual of Quechuavis decussata, photographed by christian_nunes, under CC BY-NC 4.0)

Meaning of name: Quechuavis = Quechua bird [in Latin]

Species included: Q. decussata (Tschudi's nightjar, type species, previously in Systellura)

Age: Holocene (Meghalayan), extant

Where found: Arid, open habitats in western Peru and northern Chile

Notes: Quechuavis decussata is a nightjar, a group of nocturnal, insect-eating birds. Nightjars typically spend the day camouflaged against the ground and use their wide mouths to capture flying insects at night. The Tschudi's nightjar was formerly considered a subspecies of the band-winged nightjar (Systellura longirostris), and even after being recognized as a separate species, has generally still been classified in the genus Systellura. However, genetic studies have shown that it is not closely related to members of the genus Systellura, nor does it appear to have any particularly close relatives among other South American nightjars. As a result, a new study reassigns the Tschudi's nightjar to a unique new genus.

Reference: Costa, T.V.V., P. van Els, M.J. Braun, B.M. Whitney, N. Cleere, S. Sigurðsson, and L.F. Silveira. 2023. Systematic revision and generic classification of a clade of New World nightjars (Caprimulgidae), with descriptions of new genera from South America. Avian Systematics 1: 55–99.

242 notes

·

View notes

Text

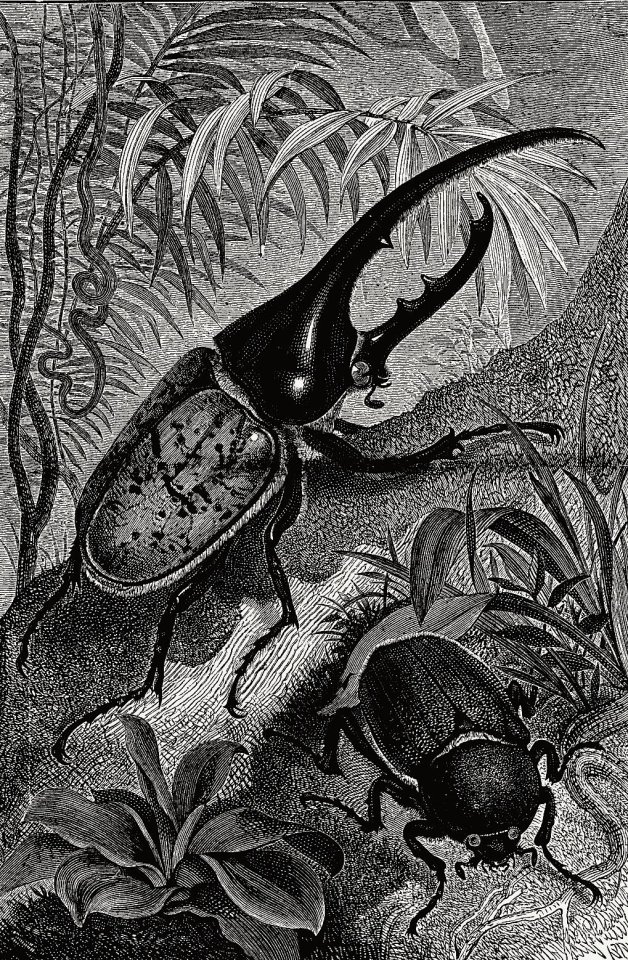

Жук-геркулес – необычное насекомое, которые встречается на берегах Карибского моря, на территориях Центральной Америки и южноамериканского континента. При среднем размере тела более 16 см. он считается одним из самых крупных жуков на планете. При этом размах крыльев у самцов редко бывает меньше 20 сантиметров. Самочки мельче самцов и могут достигать в длину не более 8 см. и у них нет рогов. Свое название этот жук получил благодаря известному древнегреческому герою Гераклу (по лат. Herculēs), который прославился своей невероятной силой. Жуки-геркулесы— «тяжелоатлеты» и способны переносить тяжести, в 850 раз превышающие их собственный вес.

Окраска жука зависит от влажности окружающей среды. Геркулес имеет жесткие надкрылья. Они могут быть темно-оливкового, желтого, желто-оливкового цвета и даже черными. Тело покрыто редкими рыжими волосками. На голове у жука находятся 2 рога, один большой сверху и второй, поменьше, ниже. Верхний рог имеет несколько зубцов.

Геркулесы – летающие жуки, однако крылья применяют лишь по мере необходимости. Благодаря цепким лапкам эти жуки отлично передвигаются по деревьям, цепляясь за кору.Жуки-геркулесы абсолютно безвредны для людей. Они не несут угрозу и сельскохозяйственной деятельности человека.Жуки-геркулесы питаются опавшей листвой, старой древесиной и древесным соком, а также перезревшими фруктами и ягодами. Продолжительность жизни имаго, так называется взрослое насекомое, равна 6 месяцев.

The Hercules beetle is an unusual insect found on the shores of the Caribbean Sea, Central America and the South American continent. With an average body size of more than 16 cm, it is considered one of the largest beetles on the planet. At the same time, the wingspan of males is rarely less than 20 centimeters. Females are smaller than males and can reach a length of no more than 8 cm. and they do not have horns. This beetle got its name thanks to the famous ancient Greek hero Hercules (Latin: Herculēs), who was famous for his incredible strength. Hercules beetles are "weightlifters" and are able to carry weights 850 times their own weight.

The color of the beetle depends on the humidity of the environment. Hercules has rigid elytra. They can be dark olive, yellow, yellow-olive and even black. The body is covered with sparse red hairs. The beetle has 2 horns on its head, one large on top and the second, smaller, below. The upper horn has several teeth.

Hercules are flying beetles, but wings are used only as needed. Thanks to their tenacious paws, these beetles move perfectly through trees, clinging to the bark.Hercules beetles are absolutely harmless to humans. They also do not pose a threat to human agricultural activities.Hercules beetles feed on fallen leaves, old wood and tree sap, as well as overripe fruits and berries. The life span of an imago, as an adult insect is called, is 6 months.

Источник:/www.zoopicture.ru/zhuk-gerkules/, /beatlename.ru/beatle18=zhuk-gerkules, /wildfauna.ru/zhuk-gerkules, /zenun.ru/zhuk-gerkules/,/redbook.su/nasekomye/zhuk-gerkules, /kartinki.pics/pics/697-zhuk-gerkules-art.html.

#nature#video#insect video#insect photography#beetle#Hercules beetle#plants#flowers#macro photo#drowing#illustration#природа#видео#фото насекомых#насекомые#жук#Жук-геркулес#растения#цветы#макрофото#арт#иллюстрация

134 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What’s this? A leaf wing butterfly (Zaretis itys). Weird and wonderful, yes?

#Animals#camouflage#amazing insects#bizarre creatures#leaf wing#unusual butterflies#Mexican wildlife#South American wildlife

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Making Better State Insects

So at some point I stumbled across a list of State Insects. Honestly I wasn't even aware states had "state insects", but as I looked down the list my disappointment grew. A vast majority of states had selected the European honeybee (which is not even native) as their state insect, with monarch butterflies and ladybugs being the two runner ups. I thought this was a damn shame because there's so many interesting insects in the US, so I'm making a better official new list of state insects.

For this list my criteria are:

Insect must be native to the state

No repeats

Insect must be easily observable to the naked eye

I also had general guidelines of picking insects that were relatively common (based on inaturalist heat maps of observation) and picking insects that were cool or interesting. Some of these insects I picked because I thought they were important parts of the areas culture and experience (lovebugs, toebiters, and periodical cicadas) and some insects I picked just to raise awareness that they exist in the US.

I also don't think I gave anyone huge L's, no mosquitoes, louses, cockroaches, ect, because my goal of this list is to get people interested in their native insects and I want it to be fun to find and observe your state insect.

Also some states get gold stars for picking state insects that already meet these criteria and are cool so they get to keep theirs. Some states also have "state butterflies" or "state agricultural insect" which for this list I'm ignoring, you can keep those I'm just focused on state insects. Slight disclaimer also, I've only ever lived in California, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, and South Carolina, and all these states are keeping their original state insect. So all the insects I'm choosing are for states I haven't lived in. Also I'm not including photos in this post just for my own sanity.

List under the cut!

Alabama

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: Giant Leaf-footed Bug (Acanthocephala declivis)

Leaf-footed bugs are cute, they're big, they're stanced up, the males have big back legs, you've probably seen them. Being true bugs they have piercing mouthparts and suck plant juices.

Alaska

Four-spot Skimmer (Libellula quadrimaculata)

Alaska gets to keep their old state insect, it's a cool dragonfly and apparently was partially chosen to honor bush pilots who fly to deliver supplies in the Alaskan wilderness, so really cool!

Arizona

Two-tailed swallowtail butterfly (Papilio multicaudata)

Arizona also gets to keep their state insect. Kind of a shame because Arizona has a lot of cool species, but it did meet my requirements and they get points for choosing a different kind of butterfly.

Arkansas

Old: European honeybee

New: North American Wheel Bug (Arilus cristatus)

One of the largest assassin bugs in the US, these guys are appreciated by gardeners for their environmentally friendly pest control. They also look badass.

California

California Dogface Butterfly (Zerene eurydice)

Endemic to California and on a stamp! Again, kind of a shame because there's a lot of cool insects in California, but I respect this choice, especially since California was the first state to designate a state insect (1929).

Colorado

Colorado Hairstreak Butterfly (Hypaurotis crysalus)

Same deal as California, the state's name is in the common name, unique butterfly found in the four corners region. Just get a stamp or something soon!

Connecticut

Old: European Praying Mantis

New: Cecropia Moth (Hyalophora cecropia)

You picked a state insect no one else had but went with a nonnative mantis? Here's an insect that'll make you stand out and it's a native species. Lesser known than some of the other giant silk moths, the Cecropia moth is the largest native moth and has some truly stunning colors.

Delaware

Old: Convergent Ladybeetle

New: Periodical Cicada (Magicicada septendecim)

Cicada's had to be somewhere on this list and Delaware was one of the main hotspots for brood X, one of the largest broods of the multiple staggered brood cycles. Hey, they have a lot of history in America. Accounts go back as early as 1733, with Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin making a note of them.

District of Columbia

Old: None

New: Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus)

The Entomological Society of America is trying to get the Monarch Butterfly added as our national insect, so I think that's reason enough to let DOC claim it.

Florida

Zebra Butterfly (Heliconius charithonia)

Florida gets to keep their state butterfly, but the populations that have existed in Florida are in steep decline. Ideally I would want being the official state insect to come with some protections, hopefully people can get invested in reintroducing them.

Georgia

Old: European Honeybee

New: Horned Passalus Beetle (Odontotaenius disjunctus)

Also called bess beetles or patent-leather beetles, these cute guys are important for forest systems because they eat decaying wood, helping to break down felled trees. They're cute beetles that squeak when disturbed.

Hawaii

Kamehameha Butterfly (Vanessa tameamea)

An endemic Hawaiian butterfly named after a ruling dynasty of Hawaii. Their population is under threat, as with a lot of native Hawaiian species, so I think this is a good state insect to build protections and activism around.

Idaho

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: Ice Crawler (Grylloblatta sp. "Polaris Peak")

Look Idaho, I have to admit that even though I've traveled extensively through WA, OR, CA, and NV I've never stepped foot in Idaho and I don't intend to. Your state exists in a weird liminal zone, not really the pacific northwest but not really whatever Montana is either. Your state isn't even all in one time zone. So look, I really wanted ice crawlers to be on this list, but they're exclusively found on mountains in the pacific northwest and Sierra Nevadas. Normally I would've given them to Washington or Oregon, but those states already have state insects that work for them. So your state gets ice crawlers, and they do exist in Idaho in the panhandle. It's not an L, ice crawlers are amazing extremophiles that crawl over snow in high elevation mountain peaks. They exist in their own unique order and theres only one genus in the US, with different species being region locked, sometimes onto specific mountains. Their thermoregulation is so delicate, the warmth of someones hand holding them causes them to over heat and die. They're cool, unique, and weird, and let's face it so is your state. At least I didn't take a cop out by picking the potato bug.

Illinois

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: Red-banded Leafhopper (Graphocephala coccinea)

Leafhopper done Chicago style.

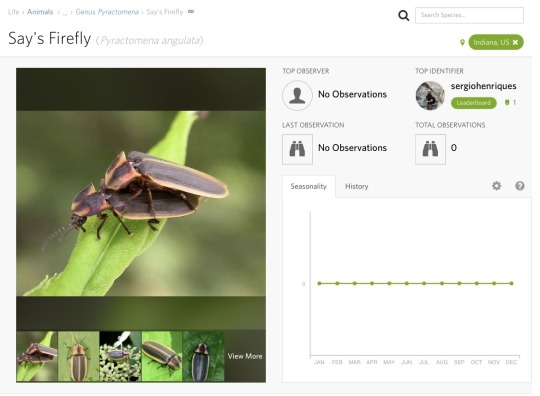

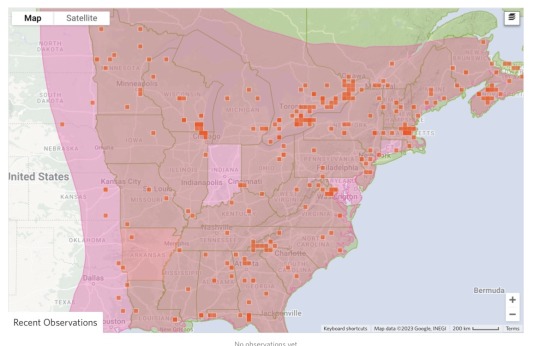

Indiana

Old: Say's Firefly

New: Common True Katydid (Pterophylla camellifolia)

I wanted to give you Say's Firefly. I really did. But when I looked on Inaturalist not A SINGLE OBSERVATION was listed for the species in Indiana. I'm even going to post pictures.

So even though this is extremely funny I'm giving your state the Common True Katydid instead. Large, loud, and easy to spot, these guys can frequently be heard chirping in trees. Not only do different populations have different rates of chirp, but the rate of chirp is also so predictably dependent on temperature that you could make an equation to tell the temperature based on chirp rate.

Iowa

Old: None

New: Westfall's Snaketail (Ophiogomphus westfalli)

Really cool clubtail dragonfly that's almost exclusively found in Iowa, Missouri, and Arkansas.

Kansas

Old: European Honeybee

New: Rainbow Scarab (Phanaeus vindex)

A kind of true dung beetle, they play an important role in removing waste. And although they don't roll waste like the stereotypical dung beetles, they are extremely pretty.

Kentucky

Viceroy Butterfly (Limenitis archippus)

This is fine.

Louisiana

Old: European Honeybee

New: Lovebug (Plecia nearartica)

Look, one of the southern states was going to get this one and Louisiana has a majority of the observations for them. Although annoying, it's things like having to scrape thousands of flies off your car that makes the Southern experience. Embrace it!

Maine

Old: European Honeybee

New: Brown Wasp Mantidfly (Climaciella brunnea)

I really wanted these guys to be somewhere on the list. Neither a wasp, mantis, or fly, these are predatory neuropterans related to lacewings. They have raptorial front legs (resembling a mantis) and their coloration resembles paper wasps that they live alongside. Weird, unique, and wonderful!

Maryland

Baltimore Checkerspot Butterfly (Euphydryas phaeton)

This butterfly might've been picked for the resemblance of the state flag. It's in decline in it's native range, so hopefully more awareness and consideration to state insects will help push conservation efforts.

Massachusetts

Old: Ladybug

New: Hornet Clearwing Moth (Paranthrene simulans)

Hornet mimic moth, the caterpillars feed on chestnuts and oaks. All lepidopterans (moths and butterflies) have modified hairs on their wings that form the "scales" that give this order their name. For this moth though, parts of it's wings don't have any scales so it more convincingly resembles a hornet. Underneath the scales, butterfly and moth wings look pretty much like any other insect's wing. Cool!

Michigan

Old: None

New: American Salmonfly (Pteronarcys dorsata)

The biggest salmonfly in North America. They make excellent fishing bait, and several fly fisherman use salmonfly lures to catch trout. Their nymphs are also an important indicator of water quality, with them being one of the first species to disappear in the presence of pollution or contaminants.

Minnesota

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: American Giant Water Bug (Lethocerus americanus)

Also one of the ones that had to be on the list somewhere, and the Inat heatmap says Minnesota. Toebiters are part of the experience, and they are cool and ferocious looking.

Mississippi

Old: European Honeybee

New: Eastern Eyed Click Beetle (Alaus oculatus)

Click beetles have a cool adaption that allows them to launch themselves in the air to avoid predators. This makes an audible sound, hence their common name. The Eastern Eyed Click Beetle is one of the largest and most striking click beetles in the US, with large false eyespots on their thorax.

Missouri

Old: European Honeybee

New: Goldenrod Soldier Beetle (Chauliognathus pensylvanicus)

A soldier beetle that feeds on aphids and small plant pests, these beetles also eat pollen and nectar from flowers. They don't harm the flower, and though their common name reflects their preference for goldenrod flowers, they're also an important pollinator of the prairie onion (Allium stellatum). This is a native species of onion that grows from Minnesota to Arkansas.

Montana

Old: Mourning Cloak

New: Western Sheep Moth (Hemileuca eglanterina)

Mourning Cloak butterflies do technically work for my criteria, but I wanted to showcase some more regional insects in this as well, as Mourning Cloaks are found throughout North America and Eurasia. The Western Sheep Moth is an absolutely stunning giant silk moth, found throughout the western United States. Although not as big as some other silk moths, the bold orange and black coloration on these make them absolutely stand out.

Nebraska

Old: European Honeybee

New: Blowout Tiger Beetle (Cicindela lengi)

A tiger beetle with unique patterns, these guys are active predators and are particularly difficult to spot because they run extremely quickly. They seem to be pretty cold tolerant and exist from Colorado up into Canada.

Nevada

Vivid Dancer Damselfly (Argia Vivida)

This damselfly was picked as Nevada's state insect because it's widespread throughout the state and matches the state colors, silver and blue. That gets my seal of approval!

New Hampshire

Two-spotted Lady Beetle (Adalia bipunctata)

This is fine.

New Jersey

Old: European Honeybee

New: Margined Calligrapher (Toxomerus marginatus)

A pretty hoverfly, they strongly resemble bees in both looks and behavior. Larvae feed on common plant pests such as thrips and aphids, while the adults sip nectar and pollinate flowers. These helpful attributes make it something the Garden State can appreciate!

New Mexico

Tarantula Hawk (Pepsis grossa)

New Mexico wins the official state insect list by a landslide. Not only is the tarantula hawk a super cool and formidable insect to showcase, but New Mexico's state butterfly (Sandia Hairstreak) was discovered in New Mexico. No notes 10/10!

New York

Nine-spotted Lady Beetle (Coccinella novemnotata)

A native species of lady beetle that's been in decline in recent years, New York is one of the last remaining states where they've been spotted. I also appreciate that New York designated a specific ladybug species instead of just saying "Coccinellidae species".

North Carolina

Old: European Honeybee

New: Eastern Rhinoceros Beetle (Xyloryctes jamaicensis)

A large native species of rhinoceros beetle. They breed in ash trees, and are under threat due to competition from the Emerald Ash Borer.

North Dakota

Old: None

New: Nuttall's Blister Beetle (Lytta nuttalli)

As with all blister beetles, these guys have a chemical defense. Unlike the more famous Bombardier Beetle thought, instead of being black and red they are iridescent red/purple and green.

Ohio

Old: Ladybug

New: Bald-faced Hornet (Dolichovespula maculata)

Look, when the one thing everyone knows about your state is that it sucks, it's time to lean into it. Bald-faced hornets, everyone knows them, everyone has opinions about them, and they get a lot of attention. I don't think I have to explain this one anymore.

Oklahoma

Old: European Honeybee

New: Giant Walking Stick (Megaphasma denticrus)

The largest insect in the United States. Being a native walking stick, they're less damaging than the imported invasive walking sticks that are heavily controlled.

Oregon

Oregon Swallowtail Butterfly (Papilio oregonius)

Oregon in the common name and in the species name, and also has a stamp!

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania Firefly (Photuris pensylvanica)

Pennsylvania in the common name and species name. If fireflies weren't already on this list I would've made sure to include them somewhere.

Rhode Island

American Burying Beetle (Nicrophorus americanus)

When I saw this on the list I was worried. American Burying Beetles are one of my favorite insects, but they're extremely endangered now. I also thought they existed more in the midwest, so I was worried I would have to change this one because it violated the "native to the region" rule. But! To my pleasant surprise, not only did their historic range extend to Rhode Island, but there is actually a carefully maintained wild population on Block Island. They estimate between 750-1000 individuals live there, making it one of the few remaining places where the American Burying Beetle still exists. Excellent work Rhode Island!

South Carolina

Carolina Mantis (Stagmomantis carolina)

This is fine. I wanted to give South Carolina the Palmetto bug but they're actually not native.

South Dakota

Old: European Honeybee

New: Golden Northern Bumble Bee (Bombus fervidus)

"Save the bees" should really be focused on native pollinators, many of whom are in decline. There are a lot of species of native bee you can feature as a state insect, with the Golden Northern Bumble Bee being a particularly large and striking species.

Tennessee

Old: Firefly and ladybug

New: Black-waved Flannel Moth (Megalopyge crispata)

Seriously look them up, these guys are adorable.

Texas

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: Rainbow Grasshopper (Dactylotum bicolor)

It was really hard to pick an insect for your state. The Texas Unicorn Mantis was a contender but I eliminated it because it's really only found in the southern part of Texas, so it was between the Rainbow Grasshopper and the Eastern Velvet Ant (or Cow Killer). I went with the Rainbow Grasshopper because it's more wide spread and common, and occurs everywhere except the east part of Texas. But the Eastern Velvet Ant only occurs on the east part of Texas, maybe you should get an East and West Texas insect? I also thought more people have probably already heard of the Eastern Velvet Ant than the Rainbow Grasshopper, which is a shame because they're super interesting to look at.

Utah

Old: European Honeybee

New: Mormon Cricket (Anabrus simplex)

Mormon Crickets are not true crickets, and instead closer related to katydids. Their common name comes from an early account of Latter-day Saint settlers in Utah. In 1848, a swarm of Mormon Crickets decimated the settler's crops, so the legend goes that they prayed for relief from this plague of insects. Later that year, a swarm of gulls appeared and ate the crickets, thus saving the crops. This is recounted in the "miracle of the gulls" story. To recognize their contributions, the California Gull is commemorated as Utah's state bird. I thought it was fitting then that the Mormon Cricket be recognized as your state insect.

Vermont

Old: European Honeybee

New: Long-tailed Giant Ichneumon Wasp (Megarhyssa macrurus)

A pretty wasp with an extremely long ovipositor, these wasps are common in deciduous forests across the eastern United States. They can't sting, and instead use their long ovipositor to stab into tree bark and deposit eggs on the horntail larvae that burrow into the trees.

Virginia

Old: Eastern Tiger Swallowtail Butterfly

New: Giant Stag Beetle (Lucanus elaphus)

A large stag beetle native to the Eastern United States. Although not as well known as their similar looking fellow stag beetles from Japan, these guys are a lovely chocolate brown instead of solid black. Like most stag beetles, they breed in decaying wood.

Washington

Green Darner Dragonfly (Anax junius)

I imagine this was chosen because it matches the flag.

West Virginia

Old: European Honeybee

New: Appalachian Tiger Beetle (Cicindela ancocisconensis)

This tiger beetle likes hilly terrain. As with all tiger beetles, they can be hard to spot because they run across the ground in search of prey. They are fast! But this can make it more rewarding when you finally catch up to one.

Wisconsin

Old: European Honeybee

New: Phantom Crane Fly (Bittacomorpha clavipes)

Don't believe old wive's tales about crane flies drinking gallons of blood, they are nonbiting. Those striking black and white legs are hollow, and are held out when they fly, making an extremely distinct sight that's been likened to sparklers or snowflakes.

Wyoming

Sheridan's Hairstreak (Callophrys sheridanii)

This is fine.

#insect#insects#state insect#long post#list#text post#entomology#bugblr#invertebrates#invertiblr#inverts#invert

190 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Groove-Billed Ani (Crotophaga sulcirostris)

Family: Cuckoo Family (Cuculidae)

IUCN Conservation Status: Least Concerned

While many species of cuckoos are brood parasites that trick other birds into incubating their eggs and raising their young, the 3 species of large-billed, black-feathered cuckoos in the genus Crotophaga, known collectively as Anis, are not, and the Groove-Billed Ani (notable for being possibly the most common Ani species) is no exception: every Groove-Billed Ani lives in a small social group consisting of 4-10 individuals, with the number of individuals in a group always being even. This even numbering is the result of the way the flock is organised, as each flock is made up of 2-5 pairs of mates, and while each individual will only breed with their mate all individuals in the group work to establish and defend a shared territory and to construct a large, cup-shaped shared nest into which every female in the flock will lay eggs. Found in grasslands, shrublands and other open habitats, the Grooved-Billed Ani is native to much of northern South America and southern North America (although on occasion it may be observed as far south as northern Argentina and as far north as Canada as a vagrant) and feeds on fruits, seeds, insects and small vertebrates, with its large and extremely powerful beak being well suited to breaking hard seed shells as well as the exoskeletons and bones of prey. Throughout the majority of its range this species is resident (non-migratory), but in the northernmost extremes of its North American range it may seasonally travel south to avoid cold weather and low resource availability during the winter.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Image Source: https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/1972-Crotophaga-sulcirostris

#Groove-Billed Ani#ani#anis#cuckoo#cuckoos#bird#birds#zoology#biology#ornithology#animal#animals#wildlife#South American wildlife#North American wildlife

932 notes

·

View notes

Text

oh here comes a bat fact:

Bats are extremely important to nature as a whole, they are crucial both to ecology and economy actually. First of all there are species of bats that eat fruit or nectar, which in turn means several fruit have evolved to be pollinated by mostly or even only bats. They’re important to south asian fruit industry that way, being responsible for stuff like mango and durian fruit being able to even bear any to begin with. In south America they pollinate agave which means syrup and tequila can’t be made without them. In some areas the decline of bats leads to fruit not being eaten which attracts pests. And in Australia flying foxes are crucial pollinators for the lumber industry

In places like the South American rainforest the fruit they eat leads to seed being spread, and bats are the first line of reintroducing trees to areas that have suffered deforestation.

In a slightly less direct way bats also eat a ton of insects and pests that would otherwise go eat crops. I’ve only seen numbers for America, but a single specific bat population eats about 10.000 pounds of insects a night, and I saw researchers estimate that bats save farmers several billion dollars worth of pesticide just by eating as normal. In an environment where bat habitat isn’t damaged and humans don’t encroach into their space too much, healthy bats are also likely helping reduce the number of insects that carry disease. I’ve only seen one article mentioning that specifically though, and I suppose you’d need a ton of bats to reduce the number of insects to the point of no disease at all.

anyway, say thank you to your neighbourhood bats as they’re probably waking up in the northern hemisphere, and blow them a kiss

66 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! SUPER interesting excerpt on ants and empire; adding it to my reading list. have you ever read "mosquito empires," by john mcneill?

Yea, I've read it. (Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620-1914, basically about influence of environment and specifically insect-borne disease on colonial/imperial projects. Kinda brings to mind Centering Animals in Latin American History [Few and Tortorici, 2013] and the exploration of the centrality of ecology/plants to colonialism in Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World [Schiebinger, 2007].)

If you're interested: So, in the article we're discussing, Rohan Deb Roy shows how Victorian/Edwardian British scientists, naturalists, academics, administrators, etc., used language/rhetoric to reinforce colonialism while characterizing insects, especially termites in India and elsewhere in the tropics, as "Goths"; "arch scourge of humanity"; "blight of learning"; "destroying hordes"; and "the foe of civilization". [Rohan Deb Roy. “White ants, empire, and entomo-politics in South Asia.” The Historical Journal. October 2019.] He explores how academic and pop-sci literature in the US and Britain participated in racist dehumanization of non-European people by characterizing them as "uncivilized", as insects/animals. (This sort of stuff is summarized by Neel Ahuja, describing interplay of race, gender, class, imperialism, disease/health, anthropomorphism. See Ahuja's “Postcolonial Critique in a Multispecies World.”)

In a different 2018 article on "decolonizing science," Deb Roy also moves closer to the issue of mosquitoes, disease, hygiene, etc. explored in Mosquito Empires. Deb Roy writes: 'Sir Ronald Ross had just returned from an expedition to Sierra Leone. The British doctor had been leading efforts to tackle the malaria that so often killed English colonists in the country, and in December 1899 he gave a lecture to the Liverpool Chamber of Commerce [...]. [H]e argued that "in the coming century, the success of imperialism will depend largely upon success with the microscope."''

Deb Roy also writes elsewhere about "nonhuman empire" and how Empire/colonialism brutalizes, conscripts, employs, narrates other-than-human creatures. See his book Malarial Subjects: Empire, Medicine and Nonhumans in British India, 1820-1909 (published 2017).

---

Like Rohan Deb Roy, Jonathan Saha is another scholar with a similar focus (relationship of other-than-human creatures with British Empire's projects in Asia). Among his articles: "Accumulations and Cascades: Burmese Elephants and the Ecological Impact of British Imperialism." Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 2022. /// “Colonizing elephants: animal agency, undead capital and imperial science in British Burma.” BJHS Themes. British Society for the History of Science. 2017. /// "Among the Beasts of Burma: Animals and the Politics of Colonial Sensibilities, c. 1840-1940." Journal of Social History. 2015. /// And his book Colonizing Animals: Interspecies Empire in Myanmar (published 2021).

---

Related spirit/focus. If you liked the termite/India excerpt, you might enjoy checking out this similar exploration of political/imperial imagery of bugs a bit later in the twentieth century: Fahim Amir. “Cloudy Swords” e-flux Journal Issue #115. February 2021.

Amir explores not only insect imagery, specifically caricatures of termites in discourse about civilization (like the Deb Roy article about termites in India), but Amir also explores the mosquito/disease aspect invoked by your message (Mosquito Empires) by discussing racially segregated city planning and anti-mosquito architecture in British West Africa and Belgian Congo, as well as anti-mosquito campaigns of fascist Italy and the ascendant US empire. German cities began experiencing a non-native termite infestation problem shortly after German forces participated in violent suppression of resistance in colonial Africa. Meanwhile, during anti-mosquito campaigns in the Panama Canal zone, US authorities imposed forced medical testing of women suspected of carrying disease. Article features interesting statements like: 'The history of the struggle against the [...] mosquito reads like the history of capitalism in the twentieth century: after imperial, colonial, and nationalistic periods of combatting mosquitoes, we are now in the NGO phase, characterized by shrinking [...] health care budgets, privatization [...].' I've shared/posted excerpts before, which I introduce with my added summary of some of the insect-related imagery: “Thousands of tiny Bakunins”. Insects "colonize the colonizers". The German Empire fights bugs. Fascist ants, communist termites, and the “collectivism of shit-eating”. Insects speak, scream, and “go on rampage”.

---

In that Deb Roy article, there is a section where we see that some Victorian writers pontificated on how "ants have colonies and they're quite hard workers, just like us!" or "bugs have their own imperium/domain, like us!" So that bugs can be both reviled and also admired. On a similar note, in the popular imagination, about anthropomorphism of Victorian bugs, and the "celebrated" "industriousness" and "cleverness" of spiders, there is: Claire Charlotte McKechnie. “Spiders, Horror, and Animal Others in Late Victorian Empire Fiction.” Journal of Victorian Culture. December 2012. She also addresses how Victorian literature uses natural science and science fiction to process anxiety about imperialism. This British/Victorian excitement at encountering "exotic" creatures of Empire, and popular discourse which engaged in anthropormorphism, is explored by Eileen Crist's Images of Animals: Anthropomorphism and Animal Mind and O'Connor's The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802-1856.

Related anthologies include a look at other-than-humans in literature and popular discourse: Gothic Animals: Uncanny Otherness and the Animal With-Out (Heholt and Edmunson, 2020). There are a few studies/scholars which look specifically at "monstrous plants" in the Victorian imagination. Anxiety about gender and imperialism produced caricatures of woman as exotic anthropomorphic plants, as in: “Murderous plants: Victorian Gothic, Darwin and modern insights into vegetable carnivory" (Chase et al., Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 2009). Special mention for the work of Anna Boswell, which explores the British anxiety about imperialism reflected in their relationships with and perceptions of "strange" creatures and "alien" ecosystems, especially in Aotearoa. (Check out her “Anamorphic Ecology, or the Return of the Possum.” Transformations. 2018.)

And then bridging the Victorian anthropomorphism of bugs with twentieth-century hygiene campaigns, exploring "domestic sanitation" there is: David Hollingshead. “Women, insects, modernity: American domestic ecologies in the late nineteenth century.” Feminist Modernist Studies. August 2020. (About the cultural/social pressure to protect "the home" from bugs, disease, and "invasion".)

---

In fields like geography, history of science, etc., much has been said/written about how botany was the key imperial science/field, and there is the classic quintessential tale of the British pursuit of cinchona from Latin America, to treat mosquito-borne disease among its colonial administrators in Africa, India, and Southeast Asia. In other words: Colonialism, insects, plants in the West Indies shaped and influenced Empire and ecosystems in the East Indies, and vice versa. One overview of this issue from Early Modern era through the Edwardian era, focused on Britain and cinchona: Zaheer Baber. "The Plants of Empire: Botanic Gardens, Colonial Power and Botanical Knowledge." May 2016. Elizabeth DeLoughrey and other scholars of the Caribbean, "the postcolonial," revolutionary Black Atlantic, etc. have written about how plantation slavery in the Caribbean provided a sort of bounded laboratory space. (See Britt Rusert's "Plantation Ecologies: The Experiential Plantation [...].") The argument is that plantations were already of course a sort of botanical laboratory for naturalizing and cultivating valuable commodity plants, but they were also laboratories to observe disease spread and to practice containment/surveillance of slaves and laborers. See also Chakrabarti's Bacteriology in British India: laboratory medicine and the tropics (2012). Sharae Deckard looks at natural history in imperial/colonial imagination and discourse (especially involving the Caribbean, plantations, the sea, and the tropics) looking at "the ecogothic/eco-Gothic", Edenic "nature", monstrous creatures, exoticism, etc. Kinda like Grove's discussion of "tropical Edens" in the colonial imagination of Green Imperialism.

Dante Furioso's article "Sanitary Imperialism" (from e-flux's Sick Architecture series) provides a summary of US entomology and anti-mosquito campaigns in the Caribbean, and how "US imperial concepts about the tropics" and racist pathologization helped influence anti-mosquito campaigns that imposed racial segregation in the midst of hard labor, gendered violence, and surveillance in the Panama Canal zone. A similar look at manipulation of mosquito-borne disease in building empire: Gregg Mitman. “Forgotten Paths of Empire: Ecology, Disease, and Commerce in the Making of Liberia’s Plantation Economy.” Environmental History. 2017. (Basically, some prominent medical schools/departments evolved directly out of US military occupation and industrial plantations of fruit/rubber/sugar corporations; faculty were employed sometimes simultaneously by fruit companies, the military, and academic institutions.) This issue is also addressed by Pratik Chakrabarti in Medicine and Empire, 1600-1960 (2014).

---

Meanwhile, there are some other studies that use non-human creatures (like a mosquito) to frame imperialism. Some other stuff that comes to mind about multispecies relationships to empire:

Lawrence H. Kessler. “Entomology and Empire: Settler Colonial Science and the Campaign for Hawaiian Annexation.” Arcadia (Spring 2017)

No Wood, No Kingdom: Political Ecology in the English Atlantic (Keith Pluymers)

Archie Davies. "The racial division of nature: Making land in Recife". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers Volume 46, Issue 2, pp. 270-283. November 2020.

Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans (Urmi Engineer Willoughby, 2017)

Pasteur’s Empire: Bacteriology and Politics in France, Its Colonies, and the World (Aro Velmet, 2022)

Tom Brooking and Eric Pawson. “Silences of Grass: Retrieving the Role of Pasture Plants in the Development of New Zealand and the British Empire.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. August 2007.

Under Osman's Tree: The Ottoman Empire, Egypt, and Environmental History (Alan Mikhail)

The Herds Shot Round the World: Native Breeds and the British Empire, 1800-1900 (Rebecca J.H. Woods, 2017)

Imperial Bodies in London: Empire, Mobility, and the Making of British Medicine, 1880-1914 (Kristen Hussey, 2021)

Red Coats and Wild Birds: How Military Ornithologists and Migrant Birds Shaped Empire (Kirsten Greer, 2020)

Animality and Colonial Subjecthood in Africa: The Human and Nonhuman Creatures of Nigeria (Saheed Aderinto, 2022)

Imperial Creatures: Humans and Other Animals in Colonial Singapore, 1819-1942 (Timothy P. Barnard, 2019)

Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890-1950 (Jeannie N. Shinozuka)

85 notes

·

View notes