#turgenev

Text

Heliotrope no Koi by Mizuno Hideko (1969)

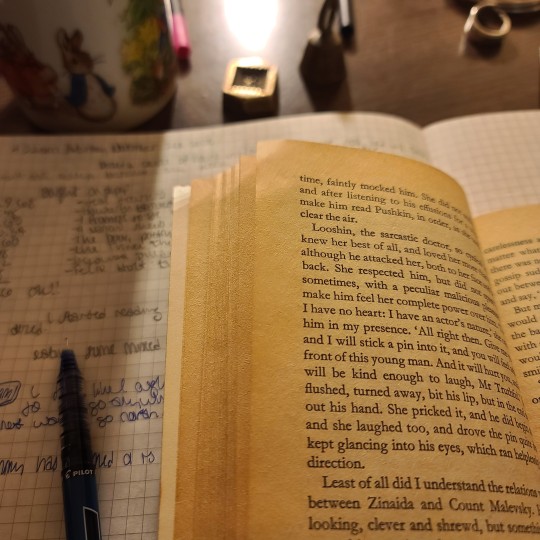

What can I say? It is known that I am weak for Russian literature and character who run towards their ruin at full speed, so I had to do this Mizuno one shot too... Here is another story by Turgenev, like the previous First Love, to give you some feelings on this cold weekend. Heliotrope Love, was adapted from his Smoke, and I strongly recommend that you read it. Here are some parts that I loved, but that were sadly weren't included in the limited page count of the manga, so I'll leave them here:

‘But I can’t live without you, Irina,’ Litvinov interrupted, in a whisper now; ‘I am yours for ever and always, since yesterday.... I can only breathe at your feet....’

...As though I could complain when you love me, Irina! I wanted only to tell you that, of all this dead past, all those hopes and efforts, turned to smoke and ashes, there is only one thing left living, invincible, my love for you. Except that love, nothing is left for me; to say it is the sole thing precious to me, would be too little; I live wholly in that love; that love is my whole being; in it are my future, my career, my vocation, my country! You know me, Irina; you know that fine talk of any sort is foreign to my nature, hateful to me, and however strong the words in which I try to express my feelings, you will have no doubts of their sincerity, you will not suppose them exaggerated. I’m not a boy, in the impulse of momentary ecstasy, lisping unreflecting vows to you, but a man of matured age—simply and plainly, almost with terror, telling you what he has recognised for unmistakable truth. Yes, your love has replaced everything for me—everything, everything!

God I wish I could love someone like that/someone loved me like that.

DDL

MangaDex

This manga was originally published in Monthly Seventeen's issues 30-36 in 1969. I must say all Seventeen manga might be just to my taste.

Thanks go to 5MENP for splitting Edelweiss with me, to phuji and shielshi, my dear Seldom gang, for making this project see the light of day.

And of course, thank you, Attolia, for giving me the push I needed to translate this. I've missed you <3

#mizuno hideko#hideko mizuno#水野英子#ヘリオトロープの恋#heliotrope no koi#heliotrope love#turgenev#ivan turgenev#smoke#Дым#russian literature#vintage shoujo#retro manga#retro shoujo#60s manga#60s shoujo#seventeen#セブンティーン

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

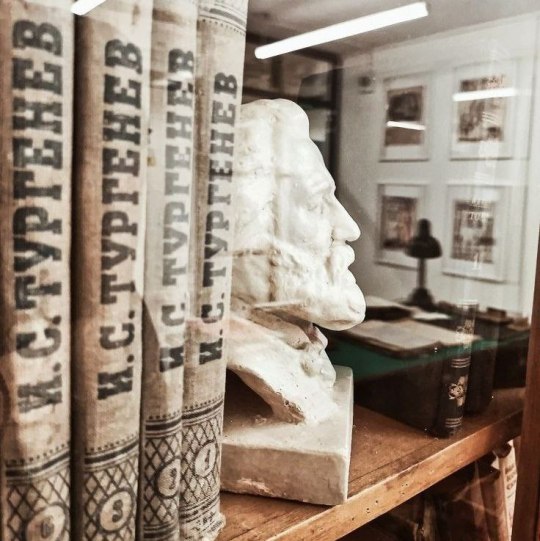

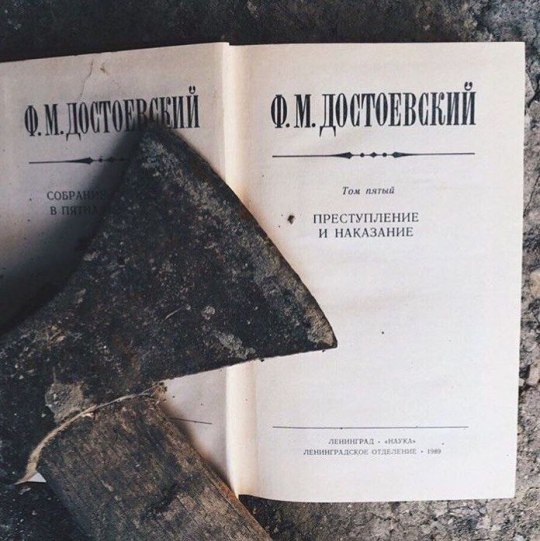

Turgenev and Dostoevsky: the conflict of two great Russian writers

At their first meeting Turgenev and Dostoevsky had a mutual sympathy; both recognised each other's brilliant abilities.

However, around other writers Dostoevsky behaved excessively arrogant. Turgenev and another Russian writer, Nekrasov, wrote an epigram which offended Dostoevsky seriously.

When Dostoevsky was exiled to forced-labor camp, relations between the writers improved, they corresponded: Turgenev was worried about his health.

Dostoevsky spoke highly of Fathers and Sons: he wrote that Turgenev had grasped social tendencies perfectly. Turgenev, on the contrary, criticised Crime and Punishment, calling it a "prolonged cholera colic".

The ideological contradiction was also the reason for the conflict: Dostoevsky was a devout monarchist and believed that Russia had a unique path to follow; Turgenev was oriented on values of West Europe. In 1867 friends-enemies met in Baden-Baden. Earlier that year, Turgenev's satirical novel Smoke was published; the author points out both the failure of revolutionaries and the ineptitude of upper class. The novel angered everyone and was severely criticised.

In a private conversation about this novel, Dostoevsky and Turgenev had a final confrontation. We know Dostoevsky's version of events from his letters: he claimed that Turgenev had denied God and called Russia's original path "a foolishness". At the same time, Dostoevsky advised Turgenev to buy a telescope, so that it would be more convenient to view the life Russia from faraway Europe where Turgenev spent a lot of time.

Later Dostoevsky in his novel The Demons made a comic figure out of Turgenev. The character Karmazinov tried to please representatives of all political directions (Turgenev was accused of the same thing). Karmazinov also created an alleged farewell manuscript, Merci (after the storm of criticism of Fathers and Sons, Turgenev wrote work Enough and announced that he was quitting literature, but after that he wrote lots of novels); finally, Karmazinov had a shrill voice (Turgenev had a rather high voice).

Turgenev could not bear such an offence. The writers remained in quarrel for the rest of their lives. Even after Dostoevsky's death, Turgenev compared him to the Marquis de Sade because of his morbid attraction to suffering.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comme il faut

Tanto voi quanto io siamo gente come si deve, cioè degli egoisti; a voi non importa niente di me, né a me di voi; non è forse così?

I. Turgenev, [Записки охотника, Zapiski ochotnika, 1874], Memorie di un cacciatore, Novara, De Agostini, 1983 [Trad. G. Pacini]

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

pavel petrovich: stop dating my nephew!

bazarov: you know what? i’m gonna start dating him even harder

#fathers ans sons#fathers and children#ivan turgenev#turgenev#russian literature#bazarov#отцы и дети#тургенев#базаров#evgeny bazarov#arkady kirsanov#ruslit

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dostoevsky vs. Turgenev

"The worldly ease with which [Turgenev] behaved, and the comfort and opulence in which he lived in Baden-Baden after he became rich, excited the envy and disapproval of many Russians and inflamed their xenophobic tendencies. No one more so than Dostoevsky, who visited Turgenev when he came to Baden on one of his gambling sprees, and deeply resented the polite but somewhat distant treatment he received. No emotional embraces and endless confabulations à la russe. Dostoevsky revenged himself by portraying Turgenev as Karmazinov in Demons, an exquisite and fastidious expatriate author whose sense of style was a byword in European literary circles, and who excelled especially in the description of delicate botanical details, always knowing the name of some obscure little flower and finding the right word for the exact shade of its sepals. Dostoevsky's treatment is devastatingly funny but totally unfair, and it wounded Turgenev deeply."

John Bayley's introduction to Fathers and Children, by Ivan Turgenev

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

turgenev, publishing yet another novel:

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Turgenev wasn't so great.]

7 notes

·

View notes

Quote

You are not an ordinary man; you are still young—all life is before you. What are you preparing yourself for? What future is awaiting you? I mean to say—what object do you want to attain? What are you going forward to? What is in your heart? In short, who are you, what are you?

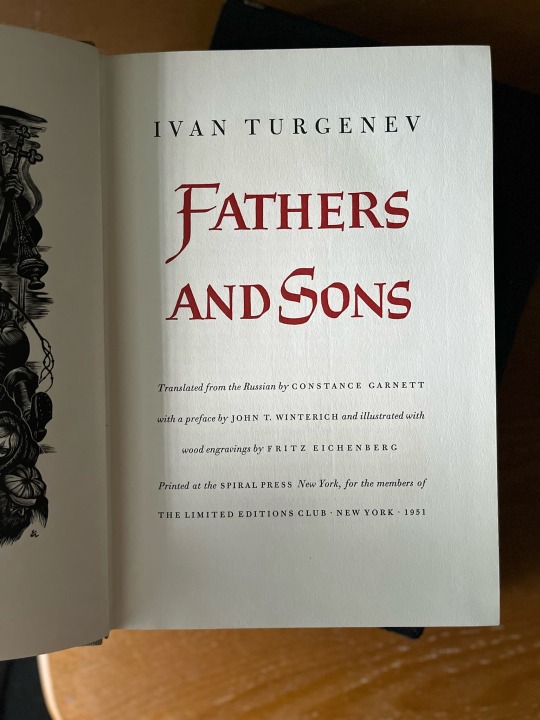

Ivan Turgenev, from “Fathers and Sons” (trans. Constance Garnett)

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The conversation turned on one of the neighbouring landowners. "Rotten aristocratic snob," observed Bazarov indifferently. He had met him in Petersburg.

"Allow me to ask you," began Pavel Petrovitch, and his lips were trembling, "according to your ideas, have the words 'rotten' and 'aristocrat' the same meaning?"

"I said 'aristocratic snob,'" replied Bazarov, lazily swallowing a sip of tea.

"Precisely so; but I imagine you have the same opinion of aristocrats as of aristocratic snobs. I think it my duty to inform you that I do not share that opinion. I venture to assert that every one knows me for a man of liberal ideas and devoted to progress; but, exactly for that reason, I respect aristocrats - real aristocrats. Kindly remember, sir" (at these words Bazarov lifted his eyes and looked at Pavel Petrovitch), "kindly remember, sir," he repeated, with acrimony - “the English aristocracy. They do not abate one iota of their rights, and for that reason they respect the rights of others; they demand the performance of what is due to them, and for that reason they perform their own duties. The aristocracy has given freedom to England, and maintains it for her."

"We've heard that story a good many times," replied Bazarov; "but what are you trying to prove by that?"

"I am tryin' to prove by that, sir" (when Pavel Petrovitch was angry he intentionally clipped his words in this way, though, of course, he knew very well that such forms are not strictly grammatical. In this fashionable whim could be discerned a survival of the habits of the times of Alexander. The exquisites of those days, on the rare occasions when they spoke their own language, made use of such slipshod forms; as much as to say, "We, of course, are born Russians, at the same time we are great swells, who are at liberty to neglect the rules of scholars"); "I am tryin' to prove by that, sir, that without the sense of personal dignity, without self-respect - and these two sentiments are well developed in the aristocrat - there is no secure foundation for the social ... bien public... the social fabric. Personal character, sir - that is the chief thing; a man's personal character must be firm as a rock, since everything is built on it. I am very well aware, for instance, that you are pleased to consider my habits, my dress, my refinements, in fact, ridiculous; but all that proceeds from a sense of self-respect, from a sense of duty - yes, indeed, of duty.I live in the country, in the wilds, but I will not lower myself. I respect the dignity of man in myself."

"Let me ask you, Pavel Petrovitch," commented Bazarov; “you respect yourself, and sit with your hands folded; what sort of benefit does that do to the bien public? If you didn't respect yourself, you'd do just the same."

Pavel Petrovitch turned white. "That's a different question. It's absolutely unnecessary for me to explain to you now why I sit with folded hands, as you are pleased to express yourself. I wish only to tell you that aristocracy is a principle, and in our days none but immoral or silly people can live without principles. I said that to Arkady the day after he came home, and I repeat it now. Isn't it so, Nikolai?"

Nikolai Petrovitch nodded his head. "Aristocracy, Liberalism, progress, principles," Bazarov was saying meanwhile; "if you think of it, what a lot of foreign . . . and useless words! To a Russian they're good for nothing."

"What is good for something according to you? If we listen to you, we shall find ourselves outside humanity, outside its laws. Come - the logic of history demands . . . “

"But what's that logic to us? We can get on without that too."

"How do you mean?"

"Why, this. You don't need logic, I hope, to put a bit of bread in your mouth when you're hungry. What's the object of these abstractions to us?"

Pavel Petrovitch raised his hands in horror.

"I don't understand you, after that. You insult the Russian people. I don't understand how it's possible not to acknowledge principles, rules! By virtue of what do you act then?"

“I’ve told you already, uncle, that we don't accept any authorities," put in Arkady.

"We act by virtue of what we recognise as beneficial," observed Bazarov. "At the present time, negation is the most beneficial of all - and we deny - “

"Everything?"

"Everything!"

"What, not only art and poetry . .. but even . . . horrible to say . . .”

"Everything," repeated Bazarov, with indescribable composure.

Pavel Petrovitch stared at him. He had not expected this; while Arkady fairly blushed with delight.

"Allow me, though," began Nikolai Petrovitch. "You deny everything; or, speaking more precisely, you destroy everything. . . . But one must construct too, you know."

“That's not our business now. . . The ground wants clearing first."

"The present condition of the people requires it," added Arkady with dignity; "we are bound to carry out these requirements, we have no right to yield to the satisfaction of our personal egoism."

This last phrase obviously displeased Bazarov; there was a flavour of philosophy, that is to say, romanticism about it, for Bazarov called philosophy, too, romanticism, but he did not think it necessary to correct his young disciple.

"No, no!" cried Pavel Petrovitch, with sudden energy. "I'm not willing to believe that you, young men, know the Russian people really, that you are the representatives of their requirements, their efforts! No; the Russian people is not what you imagine it. Tradition it holds sacred; it is a patriarchal people; it cannot live without faith. . .”

"I'm not going to dispute that," Bazarov interrupted. "I'm even ready to agree that in that you're right."

"But if I am right . . . "

"And, all the same, that proves nothing."

"It just proves nothing," repeated Arkady, with the confidence of a practised chess-player, who has foreseen an apparently dangerous move on the part of his adversary, and so is not at all taken aback by it.

“How does it prove nothing?" muttered Pavel Petrovitch, astounded. "You must be going against the people then?"

"And what if we are?" shouted Bazaroy. "The people imagine him; when it thunders, the prophet Ilya's riding across the sky in his chariot. What then? Are we to agree with them? Besides, the people's Russian; but am I not Russian, too?"

"No, you are not Russian, after all you have just been saying! I can't acknowledge you as Russian."

"My grandfather ploughed the land," answered Bazarov with haughty pride. "Ask any one of your peasants which of us - you or me - he'd more readily acknowledge as a fellow-countryman. You don't even know how to talk to them."

"While you talk to him and despise him at the same time."

"Well, suppose he deserves contempt. You find fault with my attitude, but how do you know that I have got it by chance, that it's not a product of that very national spirit, in the name of which you wage war on it?"

"What an idea! Much use in nihilists!"

"Whether they're of use or not, is not for us to decide. Why, even you suppose you're not a useless person."

"Gentlemen, gentlemen, no personalities, please!" cried Nikolai Petrovitch, getting up.

Pavel Petrovitch smiled, and laying his hand on his brother's shoulder, forced him to sit down again.

"Don't be uneasy," he said; "I shall not forget myself, just through that sense of dignity which is made fun of so mercilessly by our friend - our friend, the doctor. Let me ask, he resumed, turning again to Bazarov; "you suppose, possibly, that your doctrine is a novelty? That is quite a mistake. The materialism you advocate has been more than once in vogue already, and has always proved insufficient . . . ”

"A foreign word again!" broke in Bazarov. He was beginning to feel vicious, and his face assumed a peculiar coarse coppery hue. "In the first place, we advocate nothing; that's not our way.”

"What do you do, then?"

"I’ll tell you what we do. Not long ago we used to say that our officials took bribes, that we had no roads, no commerce, no real justice . . . “

"Oh, I see, you are reformers - that's what that's called, I fancy. I too should agree to many of your reforms, but . . . “

"Then we suspected that talk, perpetual talk, and nothing but talk, about our social diseases, was not worth while, that it all led to nothing but superficiality and pedantry; we saw that our leading men, so-called advanced people and reformers, are no good; that we busy ourselves over foolery, talk rubbish about art, unconscious creativeness, parliamentarism, trial by jury, and the deuce knows what all; while, all the while, it's a question of getting bread to eat, while we're stifling under the grossest superstition, while all our enterprises come to grief, simply because there aren't honest men enough to carry them on, while the very emancipation our Government's busy upon will hardly come to any good, because peasants are glad to rob even themselves to get drunk at the gin-shop."

"Yes," interposed Pavel Petrovitch, "yes; you were convinced of all this, and decided not to undertake anything seriously, yourselves."

"We decided not to undertake anything," repeated Bazarov grimly. He suddenly felt vexed with himself for having, without reason, been so expansive before this gentleman.

"But to confine yourselves to abuse?"

"To confine ourselves to abuse.”

"And that is called nihilism?"

"And that's called nihilism," Bazarov repeated again, this time with peculiar rudeness.

Pavel Petrovitch puckered up his face a little. "So that's it!" he observed in a strangely composed voice. "Nihilism is to cure all our woes, and you, you are our heroes and saviours. But why do you abuse others, those reformers even? Don't you do as much talking as every one else?"

"Whatever faults we have, we do not err in that way," Bazarov muttered between his teeth.

"What, then? Do you act, or what? Are you preparing for action?"

Bazarov made no answer. Something like a tremor passed over Pavel Petrovitch, but he at once regained control of himself.

“Hm! . . . Action, destruction . . . " he went on. "But how destroy without even knowing why?"

“We shall destroy, because we are a force," observed Arkady.” (pages 53 - 58)

“The book caused a furor upon its publication. Young radicals felt targeted by the portrayal of Bazarov; liberals felt that the book gave the radicals too much credit; reactionaries believed that Turgenev had permanently discredited the revolutionaries. Turgenev found himself defending the book, in countless letters and conversations, against criticism from all sides. Meanwhile, St. Petersburg, then the capital, was burning. In May of 1862, just a few months after the publication of “Fathers and Sons,” a series of fires engulfed the city. The government blamed Turgenev’s nihilists; a number of young people, including some of those with whom he had sparred in print, were arrested. Some thought that Turgenev had in effect denounced them. He had been spending long stretches in Europe; now, embarrassed and discouraged, he decided to return there. In the years to come, he spent less and less time in his native land.

Tall, handsome, rich, and easygoing—“Nature has refused him nothing,” was how Dostoyevsky put it—Turgenev was also indecisive, inconstant, maybe even a bit unreliable. More than any other figure in Russian literary history, he embodied the tragedy of the middle, the failure of the golden mean ever to take root on Russian soil. Both conservatives (including Dostoyevsky) and radicals despised him for his watery European ideals. He quarrelled constantly with Tolstoy, despite many ties of family and friendship. Because of his willingness to coöperate with a government investigation of émigré radicals, he was estranged for years from his old friend Alexander Herzen. His ability to see the many facets of every person and every issue—“He felt and understood the opposite sides of life,” in the words of Henry James, who got to know him in Paris—served him well as a novelist. But this ability was less desirable in a political ally, or even in a pal.

(…)

These years, in the eighteen-forties, were difficult ones, Turgenev later recalled; censors would leave writers’ proofs marked up with red ink, “as if bloodied.” The start of Nicholas I’s reign, in 1825, had been met by a failed uprising of Army officers who came to be known as the Decembrists; its ending, three decades later, was accompanied by the humiliating Russian defeat in the Crimean War. The intervening years were a period of intense repression and censorship. The generation that came of age with Turgenev was aware of Russian backwardness and subjugation, but did not know what to do about it, or even, under conditions of police surveillance, how to talk about it.

(…)

Turgenev’s first sustained effort in prose, “A Hunter’s Notebook,” usually translated as “A Sportsman’s Sketches,” begun in 1846 and published as a book in 1852, showed the imprint of Belinsky’s ideas as filtered through the mind of a born aesthete. It recorded the stories Turgenev had witnessed or heard as he tramped about the countryside near his family estate, shooting birds. A number of the stories are about the relations between serfs and their masters. Without ever saying so outright, Turgenev makes it plain that most of the masters are self-satisfied and ignorant brutes, while the serfs are ordinary people trying to go about the business of life.

(…)

Turgenev was advancing, novelistically, a line of thought that runs through all his work. Beliefs are admirable, strong beliefs perhaps even more so. But there is a point at which belief can tip over into fanaticism. Turgenev had seen this with Belinsky, and in Bazarov he re-created and dramatized it. Bazarov loves nature but turns it into a science project, loves Odintsova but feels bad about it, and loves his parents but refuses to indulge this affection by spending time with them. All of this, from Turgenev’s perspective, is a mistake. It’s well and good, in other words, to talk about the existence of God and the future of the revolution, but you need to take a break for lunch.

The profound ambiguity of Bazarov’s character opened him to multiple interpretations. Most of the radicals were insulted by the way he was depicted—by his failure in love, and his flaws, and the fact that, in dying, he ends up being no more effective than the liberal fathers he disdains. “He is represented as a vulgar male animal,” one radical wrote, “who cannot keep his hands off any presentable woman.” Reactionaries, including the secret police, were delighted by what they saw as Turgenev’s biting satire. He has “branded our adolescent revolutionaries with the caustic name of ‘Nihilists,’ ” one agent cheered in a report to his superiors. But there were some radicals, like the essayist Dmitry Pisarev, who embraced the label and Turgenev’s depiction, calling themselves nihilists from there on out. Turgenev found limited understanding among his literary peers, but one notable figure, Dostoyevsky, was very taken with the portrayal of Bazarov. He wrote Turgenev to praise the book and later created an extreme version of Bazarov in the character of Raskolnikov, who murders a pawnbroker and her sister in “Crime and Punishment.”

The book’s publication right as the radical movement reached its early apogee, as well as Turgenev’s remarkable quality of insight, gives it an uncanny position in Russian literature and life. In the period of reaction that followed the fires of 1862, the revolutionaries whom Turgenev had in mind when he wrote the book were crushed. Chernyshevsky and Pisarev were both arrested and sent to prison, as Dobrolyubov no doubt would also have been, if he’d lived; Pisarev drowned, possibly on purpose, not long after his release, and Chernyshevsky, banished to Siberia for two decades, became a broken man. When their mantle was picked up by, among other people, Vladimir Lenin, it was with a more conspiratorial, more determined flavor. Lenin worshipped Dobrolyubov and Pisarev for their iconoclasm and admired Chernyshevsky’s novel “What Is to Be Done?,” written in prison in response to “Fathers and Sons.” He had nothing but contempt for Turgenev. But think of Lenin’s famous remark about music—that he loved listening to it but tried not to listen too much, since it made him want to pet people on the head, whereas now was a time to smash people’s heads. Was he echoing Pisarev, or Chernyshevsky, or, in fact, Bazarov, who gives his final verdict on the liberal gentry in his farewell to Arkady?

(…)

Turgenev never got over the stormy reception accorded “Fathers and Sons” in Russia. He was abroad when it was published and afterward returned rarely. After the publication of his next novel, “Smoke,” in 1867, a mild love story in which one of the characters is a fervently anti-Russian Russian émigré, he had a final falling-out with Dostoyevsky, who came to see him in Baden-Baden and then told friends that Turgenev had declared himself a German. Turgenev spent most of the eighteen-seventies in Paris, where he became close to Flaubert. He was always welcomed and admired in Europe, seen as the representative there of all Russian literature. But in Russia itself, for nearly two decades, he was out of favor.

Only toward the end of his life, when tastes back home began to change and some of the old arguments were forgotten, did Turgenev find a gentler reception on his infrequent trips to Russia. Students held celebratory banquets for him; two young men recognized him at a train station and bowed to him on behalf of the Russian people for his authorship of “A Sportsman’s Sketches.” He died in France in 1883. Henry James attended the farewell ceremony at Gare du Nord, before Turgenev’s body was sent back to Russia. Two years earlier, revolutionary terrorists had finally succeeded in assassinating Alexander II. Turgenev’s funeral, in St. Petersburg, was a major cultural event, for which the police made scrupulous preparations, in case the creator of Bazarov might bring out a crowd of Bazarovs and cause a fuss.”

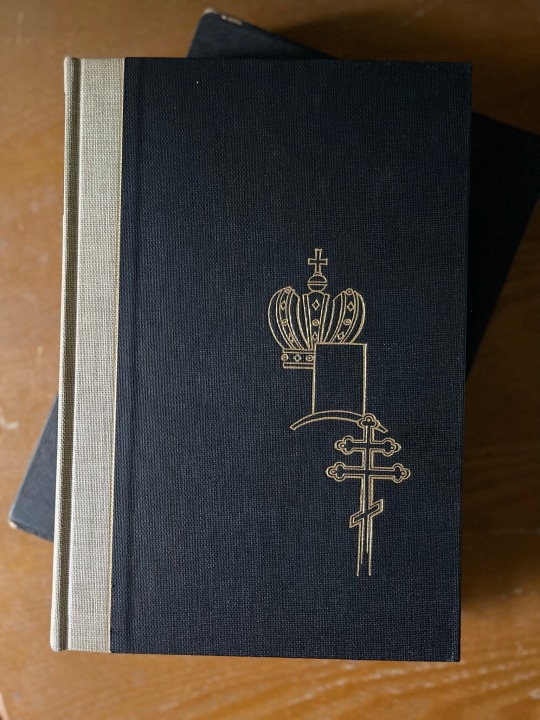

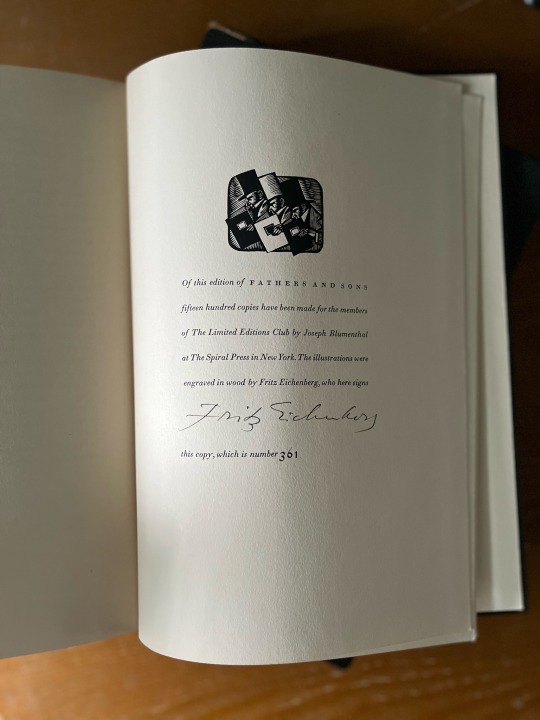

#turgenev#ivan turgenev#fathers and sons#russia#russian literature#nihilism#tradition#books#book lover#limited edition society#fritz eichenberg

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

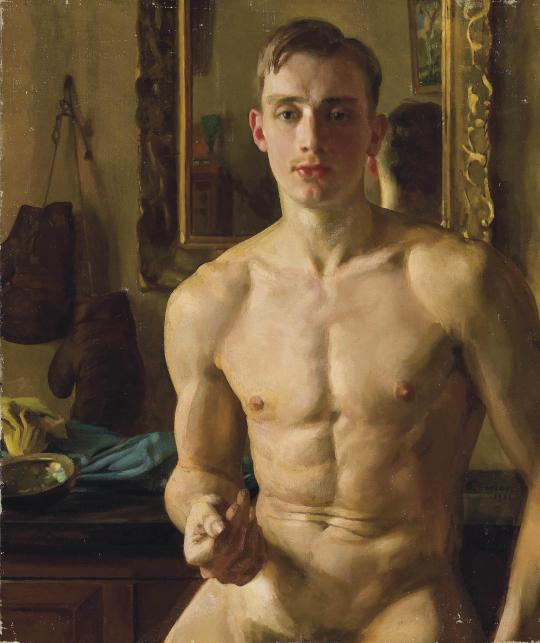

Picture : Konstantin Somov

“The misfortune of solitary and timid people - who are timid from self-consciousness - is just that, though they have eyes and indeed open them wide, they see nothing, or see everything in a false light, as though through coloured spectacles.” - “Diary of a Superfluous Man” by Turgenev

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Niente croccantini

Ermolaj non gli dava mai nulla da mangiare.

- Non ci mancherebbe altro che gli dessi da mangiare, - diceva Ermolaj. - Il cane è una bestia intelligente e saprà trovarsi da solo il cibo che gli occorre.

I. Turgenev, [Записки охотника, Zapiski ochotnika, 1874], Memorie di un cacciatore, Novara, De Agostini, 1983 [Trad. G. Pacini]

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

some rainy day turgenev doodles

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is extant of Part Two of Dead Souls "contains in embryonic form most major Russian fiction of the rest of the nineteenth century - Goncharov's Oblomov, Turgenev's Rudin, Dostoevsky's penitent criminals and Tolstoy's heart-searching landowners."

Donald Rayfield, from his introduction to Dead Souls, by Nikolai Gogol.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

i am reading articles about the relations between french and russian literature and the way turgenev just so passionately hates hugo is a delight

#i find turgenev has cringe opinions on many many issues and his writing can be so (gestures to his parody in the demons)#but the way he drags hugo... wow#he's not even wrong on that actually at least i think his criticism has merits#'he is so fake' yeah tell him ivan sergeevič!!#notes of a countryside dandy#turgenev#hugo

13 notes

·

View notes