#we as indigenous people have lost too many children to violence at schools

Text

Nex Benedict's death wasn't just for being transgender, it was for being native too. 2 Spirits are revered in many native cultures and it is a native-specific identity. This wasn't just a hate crime against trans & NB individuals, this was also a hate crime against Natives of Turtle Island.

You cannot separate Nex's trans identity from their native identity - this is a case of MMIWG2S (Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and 2 Spirits).

Native children being killed at school is nothing new, so it's equally important to talk about Nex's native identity and being intersectional, this is a devastating tragedy for indigenous people, the queer community & especially those of us who are both indigenous and queer.

May Nex rest in peace 🪶

#too many people are ignoring their indigenous identity and how that plays a role in what happened#because 2 spirit is a trans AND indigenous identity - you cannot separate the two#and it is a disservice to Nex and all other 2 spirit to do so#as a queer indigenous woman my heart aches for Nex and their family#we as indigenous people have lost too many children to violence at schools#and we as queer people have lost too many to the rise of transphobia and TERFs and their attitudes#nex benedict#mmiwg2s#2 spirit#indigenous#queer#indigenous & queer#intersectionality#racism#transphobia

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

Important Shit They Didn’t Teach Me At School

Education is, as we all know, a vital component in our lives. They do not call them our formative years for nothing. Yet, there are many things, those in charge of teaching, do not include in our learnings. The state or a particular religious organisation are most usually involved in defining the taught curriculum. Somehow, I find, there is always important shit they didn’t teach me at school. Stuff that they left out for reasons unbeknown to me but of which I am now willing to speculate upon. I have extended my research beyond just my own school days to include the experiences of others from different eras.

My School Education About Aboriginal Australia

In Australia, we are currently about to vote in a referendum about changing the Constitution to recognise First Nations people and to give them a voice to parliament in an advisory role. This has proven to be contentious with those unwilling to grant such recognition calling it divisive. These lively debates in the media have caused me to ponder upon my own education about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. I remember some pretty general historical stuff delivered from the colonising European’s perspective. Although, we had stopped calling them ‘savages’ by this time in the 1970’s the view was fairly bleak. Aborigines were painted as the race time forgot and their future, outside of assimilation, seemed questionable.

They Didn’t Teach Me About Genocide & Massacres In Australia

I did not learn at school that many native groups were massacred by both settlers and a native frontier police force. I did not learn that mass poisonings were pretty common, where settlers would add arsenic or strychnine to flour given to Aboriginal groups on their land or a water hole would be poisoned. The local Indigenous children, women, and men would die in agony from these crimes against humanity. Indeed, there was a complete absence of such truth telling in my secondary education at school. I canvassed my daughter on this same topic, as she grew up in Queensland where this behaviour by settlers was more prevalent in 19C Australia. Her secondary schooling was done by a Christian College on the Sunshine Coast in 2017-2021. My daughter has no recollection of such shocking historical facts being imparted to her in Australian history classes. Indeed, Aborigines played little part in this Christian based curriculum at all, according to her very recent recall on the matter.

Teaching & Whitewashing In Australia

I spoke with several acquaintances and friends from different age groups, some older and some younger, about these matters. I asked them to spend some time reviewing these things and to get back to me when convenient. None of them could recollect being taught about these heinous crimes being committed. Yes, references to massacres by gunfire were sketchily mentioned by a few teachers but these were usually pretty thin on details given. Whitewashing our colonial past would not be a too strong categorisation of this policy enacted by our education departments and those of the independent schools.

The upshot is that Australians do not know the true extent of what happened to First Nations people during colonisation in the 18C, 19C, and even into the early 20C.

Killing For Country: A White Agenda

David Marr, the respected journalist and writer, has recently published Killing For Country. This is an account of his forebears, who were involved in the Native Frontier Police, an official force tasked with killing native blacks. Marr estimates that they may have conservatively killed some 40, 000 First Nations people.

“David Marr was shocked to discover forebears who served with the brutal Native Police in the bloodiest years on the frontier. Killing for Country is the result – a soul-searching Australian history. This is a richly detailed saga of politics and power in the colonial world – of land seized, fortunes made and lost, and the violence let loose as squatters and their allies fought for possession of the country – a war still unresolved in today's Australia.

"This book is more than a personal reckoning with Marr's forebears and their crimes. It is an account of an Australian war fought here in our own country, with names, dates, crimes, body counts and the ghastly, remorseless views of the 'settlers'. Thank you, David."—Marcia Langton”

- (https://www.blackincbooks.com.au/books/killing-country)

What you get in modern Australia is a populace largely unaware of the true extent of the genocide that went on to establish a white Australia in a land that had been Aboriginal for around 70, 000 years. This is a direct result of the important shit they didn’t teach me at school. It spurs one to ponder what else was missing from my state run education?

Australia, through its less than honest account of its colonial past, has sought to minimise and normalise its treatment of First Nations people. Former PM, John Howard, would not say sorry, as a strategic position in defence of how Australian governments dealt with their Indigenous population. “It all happened a long time ago,” is the common refrain from those unwilling to acknowledge the sins of the past. Well, actually it was not all that long ago in the time frame of history, more generally. Modern Australia is a very young country. Killings were still happening around a hundred years ago. Aboriginal deaths in custody are still occurring at an alarming rate today. The genocide continues in some form or another.

“The frontier wars were a series of violent conflicts between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. While conflicts and skirmishes continued between European land holders and Traditional Owners, the military instrument of the Queensland Government was the Native Police.

The Native Police was a body of Aboriginal troopers that operated under the command of white officers on the Queensland frontier from 1849 to the 1920s. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men were often forcefully recruited from communities—already diminished due to colonisation—that were normally a great distance from the region in which they were to work. They were offered low pay, along with rations, firearms, a uniform and a horse. Many deserted.”

- (https://www.qld.gov.au/recreation/arts/heritage/archives/collection/war/frontier-wars)

You cannot mass murder a bunch of people and just move on. There are ramifications and consequences of such appalling behaviour long felt. Truth telling is the next stage in the Uluru Statement from the Heart process. If you do not know the real history of your country and community – you do not know yourself.

Was White Australia Born Out Of Biological Warfare?

There is credible speculation that the huge volume of mass Aboriginal deaths via disease around Port Jackson in the early years of British colonisation was due to small pox infection and was no accident. The first fleet were carrying vials of small pox in their cargo, according to the journals of Captain Watkin Tench. Plus, this form of biological warfare had been used on American Indians by the British. There were marines aboard who had been involved in those actions. The fleet were heavily outnumbered by the natives, running low on ammunition, and getting desperate for provisions to arrive. The military were, also, unhappy with the overly humanitarian leadership of Governor Arthur Philip in relation to dealing with the natives.

“In the 18th century, the use of smallpox by British forces was not unprecedented. This tactic was promoted by Major Robert Donkin and used by General Jeffrey Amherst in 1763, when smallpox-laden blankets and a handkerchief were distributed to Native Americans from Fort Pitt near the Great Lakes.

An outbreak of smallpox in Sydney in 1789 killed thousands of Aborigines and weakened resistance to white settlement. Chris Warren argues that the pandemic was no accident, but rather a deliberate act of biological warfare against Australia’s first inhabitants. In April 1789, a sudden, unusual, epidemic of smallpox was reported amongst the Port Jackson Aboriginal tribes who were actively resisting settlers from the First Fleet. This outbreak may have killed over 90 per cent of nearby native families and maybe three quarters or half of those between the Hawkesbury River and Port Hacking. It also killed an unknown number at Jervis Bay and west of the Blue Mountains.”

- (https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/ockhamsrazor/was-sydneys-smallpox-outbreak-an-act-of-biological-warfare/5395050)

The denial of these terrible truths about the birth of white Australia is apparent in the loud No Vote campaign. The awful Sky News Australia, with its tabloid style opinion based journalism (if you can call it journalism), bleats its badly informed and racist message across the airwaves. The Murdoch media empire makes its money from exploiting the likes and dislikes of the dominant white cohort. It appeals to their fears by dog whistling up bogus issues like Aboriginals taking their homes and money. Downward envy is their house speciality. This appalling family has been at the epicentre of the Australian media landscape for decades. The descendants of European invaders and in some cases murderers are thin skinned and sensitive to any perceived slights upon their family name or character. Saying sorry is a bridge too far for many of these folk.

Modern Australia Must Embrace Truth Telling To Know Itself

Modern Australia wants its children and citizens to refer to a particular interpretation of our history. It does not want the populace to consider the brutal realities of its colonial past. Indeed, for much of the brief history of white Australia the thinking was that Aborigines would die out and be assimilated into the larger pool of a national identity. Unfortunately for the social planners and their political masters this has not happened. Stubbornly, First Nations identities have stuck around despite the institutional racism over centuries. Indeed, generations of Indigenous Australians are taking great heart in their particular identities. Now, they want Constitutional recognition and a voice to parliament advising on those issues directly affecting them. The No Vote campaign is running messages of assimilation with bumper stickers saying, “One Voice, One Mob, One Nation.” This is a denial of Aboriginal culture and a call for Australian homogeneity. This is a campaign based on ignorance from a white population which has been cosseted and protected from the truth. If anything solid has come out of this referendum, whatever the result, it has been a refocusing on First Nations people in Australia. Perhaps, learning about what really occurred during the invasion and colonisation of this land. Maybe, deepening the understanding of the situation now and then.

Honest relationships are never built on brushing over the past. Truth telling and treaty are coming.

Returning to the theme of this article, the important shit they didn’t teach me at school, a society is controlled by what they know and don’t know. This is why education is so important and why we had the history wars back in the 1990’s. The denial of the dark past is just as important as the abuse and injustice that goes on today. It forms of a framework for current reality. “If you don’t know, vote No.” This sums it up because, most of us don’t know and that has been by design. Yes, I hate to say that it is a conspiracy, because there are so many misguided conspiracists out there in the biosphere, but the manipulation of history is always so. Those in power make every effort to control the version of history promulgated within a nation for very good reasons. Culture is moulded out of those voices emerging from history, which are enhanced and amplified according to the wishes of those in power today. The ANZAC myth is the loudest one playing in modern Australia. This heroic story of gallant defeat has become the foundational myth defining our character. White Australia marching to the rescue of the mother country a long way from home. ANZAC day, since John Howard’s time has been amped up unceasingly to become a state religious festival. The nation unifies around this narrative of courage under fire. Murdering Aborigines fades into an uncertain misty past in comparison to the fine upstanding state sanctioned memories of the ANZACS.

Vote Yes in the referendum on 14th October 2023 for a better, braver future for Australia. Compassion makes for bigger hearts and better human beings.

Robert Sudha Hamilton is the author of Money Matters: Navigating Credit, Debt, and Financial Freedom.

©WordsForWeb

Read the full article

#AborigianlAustralia#Australia#colonialism#DavidMarr#education#FirstNations#genocide#history#IndigenousAustralians#massacres#moralfailure#nativepolice#politics#Voicereferendum

0 notes

Text

Typing on my phone at 4:30 am, please forgive any mistakes.

Trigger Warning for Abuses mention and speaking about those damn Indigenous Boarding Schools.

I'm personally surprised and somewhat glad that Pope Francis is in Canada and made an apology to the tribes affected by the downright heinous cultural genocide and violence by the schools. Mass graves is already a tragic and unacceptable thing when so many people are dying at a given time. Sometimes the situation results in people resorting to such a thing. But these countless (as we don't know exact numbers) indigenous children being discarded into mass graves and hidden is beyond words in the English language. I don't think there is anything the Pope, Catholic Church, or Canadian Government can do to ever fully repair the damage done. These people will still have scars after healing. I hope that this begins a process where the information the tribes seek is honestly given. I hope my fellow white people sit down, shut up and listen, and let the mixed feelings and outright rage that all of these people are experiencing be felt. They have a right to their feelings and anger is a part of healing too. Not to mention it is extremely valid. Native communities appear to be resilient and strong to me and I am sure that they will heal together, but just because someone is tough does not mean that they have to 'grin and bear it' or that they can't have moments of vulnerability and/or pain. This wound is deep. But I hope this begins to staunch the free-flowing blood so that the wound can begin to heal. It is on us white immigrants to be there for any indigenous person who is hurting right now. We can start by listening and not telling them how they should or shouldn't feel. We can start by acknowledging the wretched facts and assisting if we can in their healing. I haven't seen footage of the Pope's apology and it does appear performative, it is my hope that action follows. Otherwise, the whole apology is pointless and he probably just upset many people by simply being there for no good reason. I also felt deeply uncomfortable when I saw him wearing that headdress. I don't know how that came to pass, I just know it didn't look or feel right. But I don't think my opinion matters.

I don't think there is much I can do right now for local indigenous communities as I literally have no money to give to support them financially. I'd have to look and see if there are other ways to get involved and further educated. I will still apologize even if it is meaningless because it is just one white person here saying it. But I mean it most sincerely when I say I see you and hear you. Your feelings and pain are valid, don't let anyone tell you otherwise. I'm truly sorry for the multitudinous and inhumane actions wrought upon your communities by white people. And I mean in both Americas (including the islands). This should never have happened and it should never be forgotten by us white people. I pray you know peace and I pray for those lost to the violence of forced assimilation and taking of land. Literally every incident or encounter seems to be a bloody or deceitful moment between white people and indigenous people. And we all know who the victims were in these moments. If anything I said is offensive or not correct, please let me know as I do not wish to cause further harm. 🧡 (is it okay for me to add the orange heart?)

#indigenous people#pope francis#canada#american history#canadian history#indigenous history#trauma#cultural genocide mention#child death mention#current events

0 notes

Text

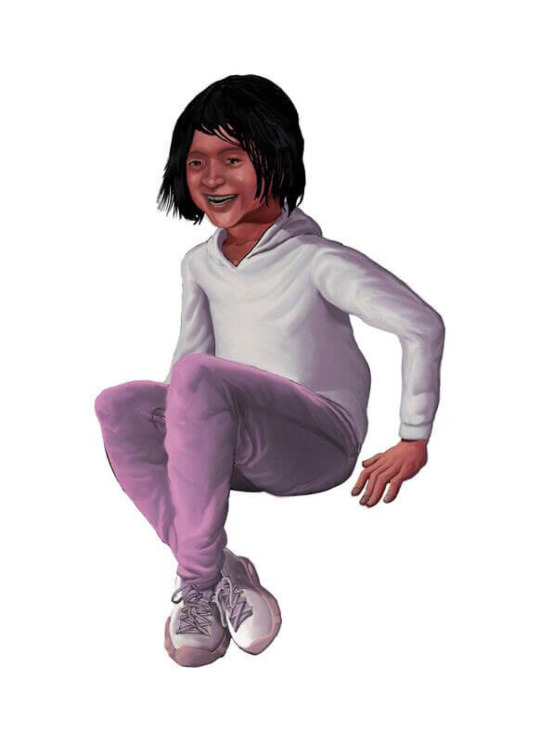

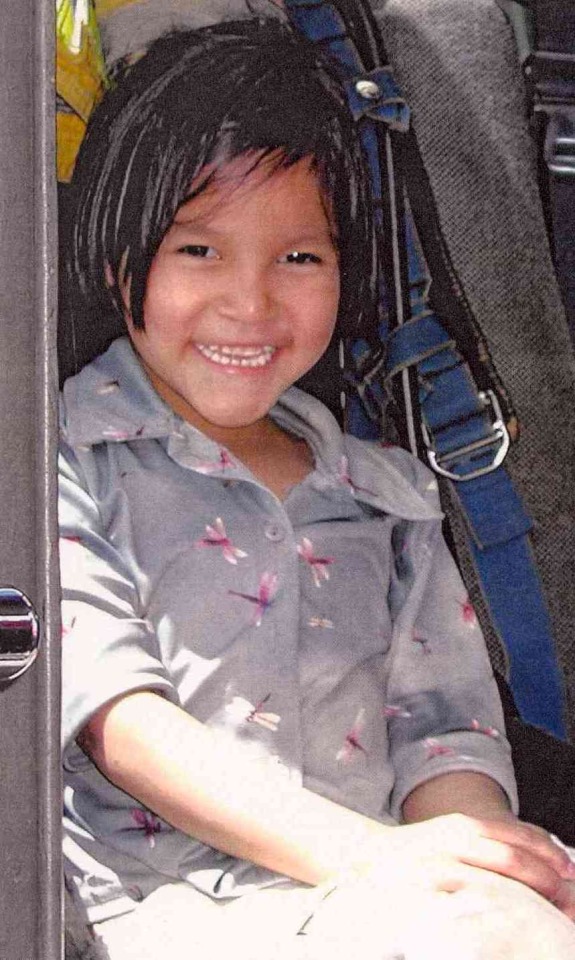

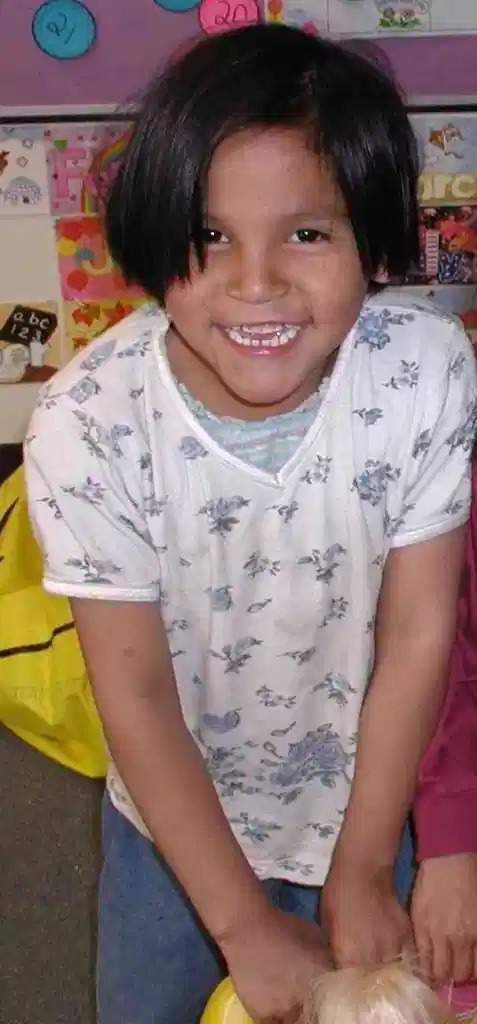

TAMRA JEWEL KEEPNESS.

FEW CHILDREN IN CANADA JUST VANISH. Fewer still stay gone for longer than a couple of days. Some are found alive, others are hurt or killed, but rarely does a child simply disappear. The RCMP’s National Centre for Missing Persons and Unidentified Remains database lists 147 missing children, in a country of more than 35 million people. Of the sixty children under the age of twelve, a quarter are thought to have been abducted by their parents. A large portion of the others were lost to apparent accidents or misadventure, falling through ice or swept away in the pull of wild rivers, their bodies never recovered. The database shows twenty-four children in the past sixty years who have inexplicably disappeared. Because there are so few, we know them. In Edmonton, there is Tania Murrell, six when she vanished while walking home from school for lunch in January 1983. In Toronto, Nicole Morin, eight when she disappeared from a condominium building in July 1985. Michael Dunahee was four years old when he went missing from a playground in Victoria in 1991. In Regina, there is only Tamra Keepness.

THE LAST TIME anyone saw Tamra, she was five years old, with bobbed black hair and soft, round cheeks. In one picture, she wears a T-shirt dotted with flowers, standing against the colourful collage of a classroom wall. Her smile is broad and open, her eyes lively. She was so smart that her mother called her “my little Einstein,” so feisty that when a little boy pushed her once, Tamra shoved him right back, and harder. She liked playing Mario Kart on Nintendo and climbing her favourite tree, down the block from her house.

July 6, 2004, was the first time Sergeant Ron Weir would hear Tamra’s name. He was getting ready to leave on vacation that day when he got an urgent call back to the police station. Weir was a veteran cop with the Regina Police Service and head of emergency services, which included search and rescue. In a meeting, officers from the major crimes unit laid out what they knew: sometime between the night of Monday, July 5, and the morning of Tuesday, July 6, a five-year-old girl had gone missing from her home in central Regina.

Weir had been a police officer for twenty years. He knew that kids often went missing and turned up safe a short time later. Sixty-five percent of missing children and teens are located within the first day, and almost 90 percent within the first week. But Weir also knew that Tamra was too young to get far as a runaway. Patrol officers had already checked the neighbourhood to make sure Tamra hadn’t wandered away or ended up at the house of a playmate or relative, as was often the case with missing children. They’d found nothing. Even in the early hours of the investigation, Weir suspected this case would be different.

TAMRA LIVED with her mother, stepfather, and five siblings at 1834 Ottawa Street, a shabby brown-and-white two-storey with a windowed porch at the front. The house stood between 11th and 12th avenues, just east of downtown Regina. The neighbourhood was a mix of long-time elderly residents, young families drawn by low prices for heritage houses, and ramshackle homes where residents struggled with poverty and addiction. The area was sometimes known as the “low stroll,” a place where women and girls sold their bodies for drugs or booze and men drove around looking to buy them, circling the neighbourhood in trucks and station wagons. Many of the women and girls who lived or worked in the area were First Nations, like Tamra. Long before calls for a federal inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women would dominate the political conversation, women were going missing from those streets. It was from that same area that nineteen-year-old Annette Kelly Peigan disappeared in 1983, followed by eighteen-year-old Patsy Favel in 1984 and Joyce Tillotson in 1993. Two years later, two young white men picked up a woman named Pamela George, sexually assaulted her, and beat her to death.

The last public development came in November 2014, when a Reddit user posted to the website a scrawled map with the words: “Location of Tamra Keepness, check the wells.”

Tamra’s house was less than a block from the Oskana Centre, a halfway house for federal parolees, and not far from the Salvation Army’s Waterston House, a residence and shelter inhabited by former inmates and men struggling with drugs, alcohol, and psychiatric issues. Residents of both facilities had been responsible for serious attacks in the past. Just four months earlier, convicted violent sex offender Randy Burgmann had lured a woman into his room at Waterston House with alcohol, before violently sexually assaulting her and leaving her beside a dumpster to die. The Oskana Centre had previously been home to both serial rapist Larry Deckert and Billy John Francis Whitedeer, who began committing violent sexual offences on children when he was ten years old. A few blocks farther was the Ehrle Hotel, one of the worst bars in town, from which patrons spilled soggy and staggering onto the sidewalk, and which appeared regularly in police reports and court testimony.

Police also had serious questions about what was happening at 1834 Ottawa Street. There was a broken window and blood spatter in the porch. Social Services had been involved with the family since not long after the oldest child was born in 1993, and there had been more than fifty reports made to crisis workers, most often about Tamra’s mother’s use of alcohol and drugs, and neglect of the children. Her mother’s boyfriend had a history of violence and domestic assault. In most cases, investigators knew, children are hurt by people closest to them.

POLICE STARTED with a thorough search of the area immediately around the home, then cast their efforts outward in an expanding grid. As the sun rose on the morning of July 7, 2004, the search effort intensified. First, there were ten officers, then twenty, then more. Some officers accompanied trained volunteer search teams; others questioned family members and potential witnesses, going door-to-door gathering leads or chasing down tips. The RCMP training academy provided cadets, and members of the public soon began arriving on their own to help.

Police set up a command-centre bus in the parking lot of a nearby church, from which Weir co-ordinated the search. Though it was an urban environment, the terrain posed serious challenges. The area was filled with overgrown yards, empty houses, piles of garbage. Tamra weighed forty pounds, and stood three foot five. There were so many places a child could hide or get trapped or be held, where a child’s body could be concealed or dumped. Searchers in orange vests worked in grids, knocking on doors, inspecting junked cars and crumbling garages, peering under discarded mattresses and piles of wood, looking down manholes. Police stopped garbage pickups, checking all the bins in the neighbourhood, the trash putrid and reeking in the summer heat. Some bins had already been emptied, so plans were made to search the dump as well.

And what if she had been taken farther? Not far away were industrial areas, large abandoned lots and buildings, Wascana Creek, and beyond that, the vast Prairie. With a thirteen-hour head start, someone in a vehicle could have had Tamra in Vancouver before she was reported missing.

When they were not speaking to police, members of Tamra’s family waited anxiously on the fringes, watching the searchers, eyeing the growing assembly of reporters and news crews holding out microphones and pointing camera lenses. “It’s not like her to go off by herself,” said Tamra’s father, Troy Keepness, sitting on the front steps of his ex-wife’s house, his voice tight with worry. “We’re trying to do our best to get her back.”

Weir worked in the command-centre bus, surrounded by maps and whiteboards. A scribe logged every aspect of the search in real time, recording ideas and progress. No one wanted to break, not for food or rest. Everyone knew the situation grew more serious with every passing hour. As the heat of the day gave way to evening, Weir stood outside and looked up. A strong wind had come in, and storm clouds were spreading, darkening the Prairie sky.

The next day, police strung crime-scene tape around Tamra’s house and the one next door, drawing it through the back alley and across six garages, long slashes of yellow dividing the street. Officers guarded the perimeter while forensic investigators went in and out of the house in boots and masks. “While we don’t have any direct evidence that Tamra has come to any harm, we also don’t know where she is,” police spokeswoman Elizabeth Popowich told reporters. “And if, in fact, this comes to a point where we determine that she’s come to some harm and it’s because of a criminal act, this location could potentially be the scene of some evidence.”

THERE WERE three adults in the house that evening: the children’s mother, Lorena Keepness; her boyfriend, Dean McArthur; and a family friend named Russell Sheepskin, who had been staying with the family. All three had come and gone during the night, and investigators were starting to question their movements. There were no signs of forced entry to the house, and there were gaps, inconsistencies in their timelines that didn’t make sense to investigators.

The story the three told publicly, compiled from various interviews, was that Lorena and McArthur got into an argument while watching a movie on Monday evening, and McArthur and Sheepskin left the house around 8:30 p.m. to go drinking. The men returned briefly to drop off a bottle of formula for the baby, then left again. Lorena went out around 11 p.m, kissing Tamra goodbye before she went. The oldest child in the house was ten-year-old Summer, the youngest was Lorena and McArthur’s nine-month-old baby. Lorena returned briefly to check on the children and then left again around midnight. At about 3 a.m., Sheepskin returned home drunk and saw Tamra sleeping on the couch. Not long after, McArthur got back to the house and assaulted Sheepskin on the porch, punching him through a window and then stomping on his head. (Both men later said the fight had nothing to do with Tamra.) Sheepskin walked alone to the hospital to get stitches, and McArthur went to stay at his aunt’s house a few blocks away. Though it should have been a short walk, he said he got lost and kept passing out as he walked there. He didn’t arrive for at least two hours, until 5 or 5:30 a.m. Meanwhile, Lorena got home around 3:15 or 3:30 a.m., climbed in through a window, and passed out on the couch. She said that she got up to undo the latch on the door for her mother around 8 or 9 a.m. and that the two eldest children, Summer and Rayne, left on their own in the morning to attend a summer day-camp. Lorena didn’t realize Tamra wasn’t there until about three hours later, when the five-year-old didn’t come downstairs. At 12:16 p.m., a family member called the police and told them Tamra was missing.

Rayne, who was eight, said he had gone to bed squeezed into the space between the wall and mattresses piled on the floor in an upstairs bedroom. He told his mother he felt Tamra get up at some point, the slight movement of a child’s weight. All he could remember was that it was light outside.

FRIDAY WAS hot again and wet from the previous night’s rain. An odour of decay hung in the air around Ottawa Street. Tamra had been gone three full days and become national news. Her picture seemed to be everywhere, hanging on street poles and store windows. In news stories, she became “missing five-year-old Tamra Keepness,” but more often she was just Tamra, as if we knew her. The front page of the Regina Leader-Post spoke directly to her, asking, “Tamra, Where Did You Go?”

Tips flooded in to police. On the street, there were rumours that Tamra had been seen at a dollar store with an older woman. Business owners in the neighbourhood said detectives had been looking for a middle-aged white man named Roch or Rocky, but police wouldn’t confirm whether that was related to the search. Lorena and McArthur said they gave police the names of five people they thought could be suspects, including a man who had befriended Tamra and later been discovered to be a pedophile. For a while, there was even a theory that Tamra had never existed at all, that she had been a scam to get extra money from Social Services. (Hospital records proved that was not the case.)

Searchers were coming from around the province to volunteer, streaming into the city from towns and First Nations communities, motivated by the faces of their own children or grandchildren to help in whatever way they could. “I’ve got a boy, and he’s twenty-one,” said Jerry Scott, one of the volunteers who joined the search. “And if he left, I’d go nuts, too.” Around the city, people organized vigils and barbecues, brought water and snacks for the searchers, wrapped ribbons around trees to show their support. Some left teddy bears and angels on the steps of Tamra’s house. Days of intensive searches had turned up lots of items that seemed as though they could be connected—clothing, a child’s shoe—but none of it belonged to Tamra. “I’m starting to go on different conclusions, like maybe someone took her, I don’t know,” Troy Keepness said. “I just hope nobody would hurt my daughter.”

WHEN Tamra had been gone a week, police announced they were suspending the ground searches. At a press conference, Regina police chief Cal Johnston announced a $25,000 reward for information and vowed, “We will find Tamra.” Police questioned sex offenders living in the area and obtained surveillance tapes from convenience stores, bars, gas stations, and the Greyhound bus depot nearby. Johnston confirmed that “criminal interference with Tamra is a distinct possibility” and drew attention back to Tamra’s house and family. “There were comings and goings from the house that night that remain not fully explained to our satisfaction, and we continue to ask those questions,” he told reporters. He would not elaborate.

Tamra’s family was growing increasingly angry at the police, and the strain of the situation was starting to show. Lorena told reporters she’d signed consent forms for police to search her house and had given her DNA, but still she felt as if they were focusing too much on her family and not enough on trying to find Tamra. She was angry that police hadn’t closed the highways out of the city and that there was no Amber Alert because police said it didn’t meet the criteria. “I’m fed up,” she told reporters. “They are wasting time. This is my little girl we’re talking about.”

The family was growing frustrated with the media, too. Lorena’s mother yelled obscenities at reporters one day, and on another, members of the family nearly came to blows with a TV reporter doing a live update from the front lawn. They had been watching the news inside the house when they heard the reporter imply what many in the city were already wondering: If not someone in that house, then who?

On July 19, two weeks after Tamra had been reported missing, police charged McArthur with assaulting Sheepskin the night Tamra disappeared. McArthur told reporters he had been interrogated for twenty hours, not about the assault, but about Tamra and about what had gone on inside the house that night. “It was always the same questions, and they were assuming that I knew the answers to those questions, but I didn’t know the answers, and I still don’t know the answers,” he said. “I would never hurt a hair on that little girl’s head.”

Two days later, Tamra’s brothers and sisters were removed from the home by child-protection officers. Tamra’s twin sister wore messy pigtails and clutched a colouring book and a yellow blanket as two women led the children away down the front steps of the house. Neither government officials nor police would say whether the children’s seizure was related to Tamra’s disappearance. When the children were gone, police searched the house again.

One night late that summer, Tamra’s father, Troy, showed up at the house with a baseball bat and confronted her stepfather, McArthur. Troy was charged with assault, though McArthur later said police “got things misunderstood.” “Everybody’s looking for answers,” he said. “We more or less talked.”

LORENA KEEPNESS was fourteen years old when she ran away from her home on the White Bear First Nation, 200 kilometres southeast of Regina. She had been in residential school for about three months, but that wasn’t what did it. For her, it was the same ugly stuff at home. She found her way to Regina. When her mom tried to take her home, Lorena wouldn’t go. She lived on the streets instead.

She had her daughter Summer Wind when she was twenty, her son Rayne Dance not long after. It was after the ultrasound for her third baby that she walked home in a daze and told her husband, Troy, “We’re having twins.” She kept repeating it until it sunk in, and then they just stood together in the kitchen and laughed. Her mother said “Way to go!” but Lorena told her, “They came from God. Not like I planted those in me.”

The babies were born on September 1, 1998. Fraternal twin girls, each weighing more than six pounds, carried almost right to term and curved around one another like pieces of a puzzle. Lorena and Troy split up when the twins were little, and after that, the girls stayed sometimes with their mother, sometimes with their father or with other relatives. Lorena and Troy each struggled with substance abuse, and their lives were sometimes too troubled and unstable to have the children with them. At five, Tamra was bold and courageous, and protective of her twin sister. Once, Lorena heard a soft knock in the middle of the night and opened the door to find the twins standing there. The children had left their father’s house and walked four blocks back to Lorena’s in the middle of the night, Tamra leading her sister by the hand as they found their way through the dark. REGINA POLICE received more than a thousand tips in the first six weeks after Tamra’s disappearance. At one point, a Volkswagen van that had been stolen the night Tamra disappeared was found burned outside the city. A jail guard told police she and a former inmate had stolen it, picked up Tamra, and then dumped the child’s body in a ravine on the Muscowpetung First Nation. Ron Weir led a week-long search on Muscowpetung, draining multiple beaver dams with compressor pumps, while searchers slogged through water up to their hips. The jail guard later confessed she had made up the story. She was charged with mischief and wrote a letter apologizing to the police. In court, her lawyer said she had been trying to get her abusive boyfriend locked up again.

Returning from medical leave to the police department in the fall of 2004, superintendent Troy Hagen could feel how Tamra’s disappearance was weighing on his colleagues. Hagen noticed it in everyone he spoke to, from the police chief down, whether they were involved with the case or not. Sergeant Rod Buckingham, one of the lead investigators, was among those who felt the growing frustration. “It’s a mystery,” he would say. “And I don’t like mysteries.”

Officers had spoken with more than 6,000 people by then, but there had been no arrests, and leads were drying up. Shortly after, a special task force was struck to re-examine the case, to see whether anything had been missed. The name of the project was iskwesis ayishowak e mamayahi, a Cree term meaning “little girl bring people together.”

TWELVE YEARS LATER, Lorena Keepness spends her days doing odd jobs and picking bottles, trading them in at the depot for cash. She is forty-three and lives with her eldest son in a rundown shack of a house on Victoria Avenue, a fifteen-minute walk from Ottawa Street. Lorena’s children were never permanently returned to her custody after the disappearance, and the three babies she had after that were all taken by Social Services, too. Tamra’s twin sister is seventeen now. Lorena says she is an athlete, smart and beautiful. Lorena lost her family pictures when someone threw all her stuff in the garbage a few years ago. The only photos she has of Tamra now are the ones on missing-child posters.

Tamra’s twin and her older sister, Summer, don’t want to be interviewed. Neither does Tamra’s father, Troy. McArthur couldn’t be reached. Lorena needs a six-pack of Black Ice beer to talk. She doesn’t really want to be interviewed either. She has never liked reporters or their questions, and it hurts to talk about that time. “But part of me wants to,” she says, as her face crumples. “Part of me needs to share what the fuck happened. Someone stole my child.”

Lorena has heard many theories about what happened to her daughter. Some believe Tamra wandered away and was abducted by a driver cruising the area or that she got lost, then crawled in somewhere so small she has never been found. Other theories focus on the adults in the house that night. Some officers will say off-the-record that they think Tamra is in the dump but that they just couldn’t find her in the mountains of debris. Many in the city believe that Lorena and McArthur sold or traded Tamra to pay off a cocaine debt. Lorena has heard that one the most. One night, she was at a bar and heard some women talking, loud enough so she could hear. “Yeah, she sold her kid for dope. She has a whole bunch of babies. She has kids just to sell them for drugs.” Her friend told her not to listen, but Lorena couldn’t ignore it. She swore at the women, promised she would get them for even thinking she could do that to her child. They met at the same bar again the next day, and that time they fought, a tangle of hair and fists. One of them had a knife and slashed her twice on the back of her arm. More scars to wear for life. It wasn’t the only time. One night, she was attacked in Moose Jaw. Not long ago, a woman shouted “Baby killer!” at her across the street.

Lorena and Dean McArthur are still together, on and off—“more on than off,” she says. Police tried hard to turn them against each other, but she always believed him in the end. He may be all kinds of things, she says, but he’s not a baby killer. “If I thought he did something to my daughter, I would have killed him myself,” she says. “I think the police were just so sure. They figured, ‘These guys are a bunch of nobodies. She did her own child.’ They already had their conclusions drawn before they even tried to look for anything.”

The suggestion she could have had something to do with her daughter’s disappearance still pushes Lorena to the point of violence. You can see her eyes flash, her muscles tighten at the question. But she holds back— it’s not worth going to jail. She’s had enough of the police, has grown used to the accusations. In the past twelve years, she’s repeated her story publicly many times, and it has never really changed.

REGINA POLICE have never released full details about the investigation into Tamra’s disappearance, on the grounds that it remains an open case that they still hope to solve. In an interview, Troy Hagen, now Regina’s police chief, would not speak about any working theories or confirm any specifics of the investigation, including whether one of the people questioned about Tamra’s disappearance had failed a polygraph test. Instead, Hagen echoed what police have said since the beginning: That there remain important unanswered questions about the comings and goings from the house on Ottawa Street that night. That they will continue to investigate every tip. That they won’t stop looking for Tamra until they find her. He pointed to cases in the United States where children have been gone for years, sometimes decades, and then been found alive. In Canada, twelve-year-old Abby Drover was held in an underground bunker in Port Moody, British Columbia, for six months after being abducted by her neighbour in 1976. There was an intensive search of her community—including by her abductor—but she had been only feet away from her house the entire time. She was found alive. It seems impossible, but it happens. “I refuse to lose hope,” Hagen says.

The years since Tamra’s disappearance have exposed the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada. Suspected serial killers are facing charges in the Prairies, but there has been no public indication that Tamra’s disappearance may be connected to any of those cases. Hagen said police have also explored a possible connection with thirteen-year-old Courtney Struble, who disappeared from Estevan, a city 200 kilometres from Regina, four days after Tamra was last seen. Investigators initially believed that Struble was a runaway, and she had been gone for seven years before RCMP announced that her case had become a homicide investigation. No one has ever been charged, and her remains have never been located. Hagen says it’s strange to have two unsolved missing-children cases linked so closely in time and geographic proximity. He says the possibility of a connection was “very much” explored by police, but there doesn’t appear to be a correlation. The police investigation into Tamra’s disappearance is one of the largest and costliest in Regina’s history, but Hagen says it has never been about the money. If there were more leads or work for investigators, the police chief says he would reconvene the task force “in a heartbeat.” But the flood of tips has slowed. The reward for information that leads to finding her, now $50,000, sits unclaimed. The last public development came in November 2014, when a Reddit user with the name MySecretIsOut posted a scrawled map with the words: “Location of Tamra Keepness, check the wells.” The person later wrote that the map belonged to their grandmother and had come from a great-aunt who had visited an inmate in Alberta. “We, like many others, haven’t forgotten about you, Tamra, and continue to search and hope you are found,” the person posted. Police searched twenty-one wells around Muscowpetung but found nothing.

Sheepskin died on January 1, 2009, “with his family by his side,” according to his obituary. Many of the police officers who worked on Tamra’s case have retired or moved from the department to other jobs. Hagen says he thinks of Tamra whenever he is walking through the forest, not looking for her but always half expecting to see her there. Sometimes he looks at people he passes on the street, examining their faces and imagining what Tamra might look like now.

THROUGH THE YEARS, Lorena has developed her own theories about what happened to her daughter. These days, she mainly wonders about a drifter who used to stay with them, a woman Lorena knew from when she was a girl. A woman who sometimes told people she was pregnant even though she wasn’t, who Lorena knew by one name but whose medical documents said something else. The woman was around so much that Lorena’s children called her Big Auntie. Big Auntie had been staying at the house before Tamra disappeared, but left after she and Lorena had a falling out. Lorena says it took a long time to realize Big Auntie wasn’t coming around any more. When she did, she put word out on the streets, but no one there had seen her either. Big Auntie didn’t even show up for her own sister’s funeral in Regina a few years back. Lorena says she told the police about Big Auntie many times, but doesn’t know whether they ever found her, or whether they even looked. “She’s just gone now,” Lorena says. “Same time as my child.” Maybe it’s something. Or maybe Big Auntie is missing, too.

When I ask Lorena whether she thinks Tamra will ever be found, she struggles for an answer. “I don’t know,” she says. “But can I tell you about a dream I had?” There are two, both so vivid it’s as if they were real. In one, Tamra is inside a big house in a city Lorena has never seen. There are silk clothes draped around, and broad windows, and Tamra is upstairs, sitting on the edge of a bathtub putting on stockings. She is grown, with dark, shiny hair like her mother’s but cut straight all around. In the other dream, Tamra is still a little girl, running into her mother’s arms. “There you are!” Lorena says. “There you are!” She picks up her child and holds her, until Tamra wriggles free and is lost again.

#indigenous#native#first nations#firstnations#aboriginal#firstpeoples#native american#canada#native canadian#indigenous people in canada#native canada#ndn#native people#ndn tumblr#northern indigenous#mmiwawareness#mmiw#mmiwg#Tamra Keepness#missing and murdered indigenous women and girls#missing and murdered indigenous women#north america#missing#no more stolen sisters#stolenland#canadian#indigenous lives matter#native lives matter#native issues#n8v tumblr

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prayers for This Threshold

This homily was given to the UU Church of Silver Spring on June 7, 2020. A video version is available at https://youtu.be/_KXZ0SGpaGk

John O’Donohue (in “To Bless the Space Between Us”) writes that a phase of life that is passing away “intensifies toward the end into a real frontier that cannot be crossed without the heart being passionately engaged and woken up.” I hope that is true. I hope it is true that the intensity we are now feeling -- the anger at police violence and other forms of white supremacy, the deep grief over lives lost, the disgust at blatant appeals toward fascism -- I hope that intensity means we are heading into a mass awakening of the mind, heart, and soul that will settle for nothing less that collective liberation.

We are, indeed, surrounded by and filled with complex and overwhelming emotion. I don’t know about you, but I can barely contain my rage and sadness. I have a hard time concentrating. And I can only imagine what my beloveds who are Black, Indigenous, and/or People of Color are feeling, how being both used to the persistence of white supremacy and yet being traumatized anew by recent events weigh on these friends and family. I am praying with and for you, for your safety, for your families, for you to be held in love. As I said in my pastoral letter last Sunday, A white supremacist system is working through humans to rob our beloveds of the breath of life. It is our moral and spiritual responsibility to respond to the deadly evil of racism.

In the midst of this violence, in the midst of racist rhetoric, in the midst of peaceful medics and clergy being driven away from a church so that the occupant of the White House can pose for a photo that makes a mockery of faith, in the midst of militarized response to people exercising their right to protest, in the midst of our own Governor sending National Guard troops to DC to attack their fellow citizens, we keep moving across other thresholds.

This year’s graduates from high schools, colleges, and other institutions find themselves marking the occasion like no other class in history, and they face challenges that echo but are not quite like any other class in history. I wish those of us who graduated some time ago could have prepared a more hospitable world by now, but I am glad this year’s class is here, ready for the world as it is and will be, already involved in the struggle for a just and sustainable society.

So many among us and around us keep adapting to changes in our calling, our vocation, our ways of paying the bills and getting by. I am thinking of hospital workers - nurses, doctors, techs, custodians, everyone who creates an environment for healing - and how they have patched together personal protective equipment from wherever they can find it, workers who know that they won’t get a raise or a bonus for their heroic work and may even be laid off thanks to our for-profit healthcare system. And then we look at the tax money being fired out of tear gas canisters and rubber bullet launchers, a seemingly endless supply of resources when the purpose is repression rather than health and well-being. The way medical staff go to work has changed. They are on the brink of something new, too. The way we do our jobs has changed for so many people, and has not changed enough for some of the most vulnerable workers. And who has a job has changed a lot in the last five months. These passages deserve noticing. Major thresholds should involve some ritual.

People keep moving, some people many miles away. Veronika spoke about her upcoming move to Florida, and how she will need to find new ways of saying goodbye, new ways of staying connected, new ways of creating a life for herself. She reminds us to keep an eye out for people who might need a friend, to ask “when can I drop off these groceries” instead of “let me know if there’s anything I can do.” Worship services may be online for some time; it is important to consider as a community what it means to welcome the stranger, what it would mean to harbor someone, how to be a place of hope and healing when a new person enters in a new way during this time of doing everything differently. As you prepare to welcome Rev. Kristin in August, the beginning of that relationship is another one that will require new rituals, new ways of marking thresholds.

Through all of this, loved ones are dying. Tanya spoke about the loss of her uncle, a revered elder in her family and in her community. According to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, we have lost over 110,000 Americans to the virus. That is 110,000 uncles, aunts, parents, children, spouses, people who were loved and valued, people who probably did not get a chance to say goodbye to their loved ones in person before they crossed the threshold. Families are finding ways to mark the passage, finding ways to connect with loved ones around the globe in their grief and to honor the life that has passed. We need these rituals, and we also need national rituals of mourning. We need to commit to each other’s well-being in solidarity with the families who grieve, and to prevent as many future deaths as possible.

Many of us are not covering a lot of distance these days in terms of miles (some of us are), but all of us are travelers. Some of us have rougher terrain than others, especially in this time of blatantly violent white supremacy, this time of undisguised ableism, this time when property gets more respect than people. Our journeys are not equal, yet they have in common the need for our attention.

We are gathered on a threshold. The voice that calls to us will ask something different of each person. We may not have chosen to be at a turning point. We do have some choices about how to understand and act on our response. The voice that is calling us forward asks us to live by our values. Let us engage and awaken our passionate hearts. The time has come to cross.

So be it. Blessed be. Amen.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I need to vent. I'm aware this will probably cause some controversy. Please know that I am open to any and all interpretation and constructive criticism so please feel free to message me with ANY questions or concerns you have! I mean it when I say that I am here for you, even if you just need a shoulder to cry on or another human to vent to.

Here are some facts that I know to be true. I am white. I am an American citizen. I am a mother. I am a grandmother. I am a person who has lost someone who died from cancer. I am a recovering drug addict. I am a wife. I am bisexual. I am a Christian. I like to think of myself as a realist. I realize that white privilege exists. Do I claim to be knowledgeable of all things controversial? ABSOLUTELY NOT! Do I want to educate myself and try to learn all that I can about said controversies? ABSOLUTLEY YES!

I saw a post earlier that said, "can y'all stop reblogging those “i am not black, but i see you” post like im begging...." I consider myself to be an ally of many people and many causes including Black Lives Matter. As I stated earlier, I am white, which obviously means I'm not black. Does that mean I cannot get behind the Black Lives Matter cause? If this is the case then logically it would make sense for me to say hey you can't support ovarian cancer awareness because your mom didn't die from ovarian cancer. Right?

Listen, I know what it feels like to be in a minority. NOT in the black minority, but a minority nonetheless. I grew up on the Flathead Indian Reservation. There were 6 other white people in my high school and 2 of them were my brothers. I don't say this to gain sympathy or in any way compare it to being in a black minority. I am just saying that I had many friends that were kind to me and supported me even though we were of a different race. It's hard to be in a minority. It's very comforting when you are a minority to know that someone else supports you and cares about you despite your differences, your skin color, your customs or beliefs, your heritage and your history.

We all belong to the human race. In my heart of hearts I feel like I would categorize myself as an introvert. I often make up excuses and cancel plans so I don't have to interact with other people. I hate this about myself and it's something I am continually working on. Because I tend to isolate and use various "crutches" to escape and numb out (pills, fan fiction, food, sleep, books, movies/tv shows etc.,), it's nice to know that someone else has your back and sees you and wants to help you. It's comforting to have a cheerleader; someone who cheers you on from the sidelines and believes in you, your dreams, aspirations and potential. It's healthy and normal for us as humans to crave interaction, kindness, attention, validation, support and love.

You don't know if I have two first cousins who are married to black people and have black children who I have personally reached out to by phone and verbally voiced my support. (I do and I have.) You don't know if I have donated money to several different Black Lives Matter causes. (I have.) You don't know if I volunteered my time one Saturday afternoon at The Navajo Nation food bank in Salt Lake City. (I did.) You don't know if I own a hijab that I can wear when I visit the local Muslim Temple with my friend. (I do.) You don't know if I actively vocalize my belief that children DO NOT belong on motorcycle or ATVS; no exceptions. (I do.) *This one gets my blood boiling. I held my best friend in my arms as her 2 year old son lie dead in a little blue coffin because his father thought it would be fun to take him on a ride on his motorcycle around the block. I will not make any exceptions to this. It's not cute. It's not safe. It's not fun. Don't do it.*

You're a Catholic? GREAT! I'll quit eating candy for 40 days with you to make Lent a little less lonely. You're a Muslim? AWESOME! I'll cover your shift while you go do salat. You're a native from India? SUPER! I won't eat beef in front you because I wouldn't want to make you uncomfortable. You're a Jew? FANTASTIC! I'll help you make challah for Rosh Hashanah. You're a Native American? AMAZING! Please let me vocally support Indigenous People's Day instead of Columbus Day. You're a recovering/ active addict? REMARKABLE! Me too! Please tell me if I say or do anything that triggers you.

Do you understand what I am trying to say? We are all members of the human race. No one wants to be alone in this journey called life. It's nice to have someone there in your corner, cheering you on, whether they are quiet about it or choose to shout it from the rooftops. Call me naive, but I believe that we can COEXIST.

It all boils down to the first and great commandment....LOVE ONE ANOTHER. Even if you don't believe in God, I think we can all get behind this mantra. Just be a good human. Treat people with kindness. Choose love. Be nice to nice. Don't stand idly by while a fellow member of the human race is suffering. Do something. Say something. Stand for something. Educate yourself.

In conclusion, I will support you. Unless it is something inherently evil that you actively and vocally support, ie: nazis, white supremacy, homicide, rape, child pornography, domestic violence, etc., I will be there. In whatever capacity is comfortable for you, I will be there.

Take care my fellow humans. In my heart of hearts I choose to believe that Good will ALWAYS conquer Evil.

#i hope i was able to convey my feelings without offending anyone#although deep down i know people will always find offense in many things if it doesn't line up with their core beliefs#i am praying for all the families that have been affected by this ugly preventable tragedy#blm#may god have mercy on us all#george floyd#tpwk#eat the apple#let it burn#speak your truth#validate and accept#show respect#stand and deliver#lead me guide me walk beside me#help me find the way#speak up. speak out. speak your truth.#say my name#coexist#life's a dance#tread lightly#be gentle and humble and aware and polite and selfless and compassionate and kind and respectful and empathetic#just be a good human and do what you can in regards to your own individual situation#thank you for listening to my sincere and heartfelt opinion#✌🤟🙏🥰😘😇#if you are a person who prays i encourage you to pray for a resolution to the tragic and unfortunate circumstances that are affecting us all#i love you. i see you. i stand with you.#i bless it#all the love - liesl/lou/luna 💝#you can make a difference

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

A SPECIAL JOURNAL REPORT: Family still seeking justice one year after Macy woman's death Galen and Tillie Aldrich hold a photograph of their daughter, Ashlea Aldrich, whose lifeless body was found in a farm field on the Omaha Indian Reservation. Galen Aldrich speaks at a memorial service for his daughter, Ashlea Aldrich, at the Walthill Fire Hall on Jan. 7. Ashlea Aldrich was found dead a year before on that date. Galen and Tillie Aldrich talk about the death of their daughter, Ashlea Aldrich, during an interview in their rural Walthill, Nebraska, home in January 2020. The naked body of Ashlea Aldrich, a 29-year-old mother of two, was found in a farm field on the Omaha Indian Reservation. The Aldriches say her death was the result of domestic violence. Tillie Aldrich, center, and Galen Aldrich, right, give gifts to family members at a memorial service for their daughter, Ashlea Aldrich. Tillie Aldrich, right, and Galen Aldrich, left, give gifts to family members at a memorial service for their daughter, Ashlea Aldrich, at the Walthill Fire Hall in Walthill, Nebraska, on Jan. 7. Ashlea Aldrich was found dead one year ago on this day. MACY, Neb. — Framed inspirational quotes decorated Galen and Tillie Aldrich’s home on a bitter cold day in January 2020. Photos of their youngest daughter, Ashlea, once hung in their places on the light-beige walls. After the 29-year-old mother’s lifeless body was found lying muddy and naked in a cornfield on the Omaha Indian Reservation two weeks earlier, her photos were packed away and her clothes were bundled up in a gray star quilt. In keeping with tribal tradition, Galen then took the quilt to the old Cook homestead north of Macy, said a prayer and hung it in a tree. “It’s like our mourning process,” he explained. “We keep her for four days and then we send her off to heaven. If we cry too much or keep some of her photographs and clothes, that might stop her from going. Her spirit will just wander around here.” The Aldrich family holds a memorial service at the Walthill Fire Hall for Ashlea Aldrich who was found dead a year ago in January 2020. The Aldriches claim Ashlea lost her life because of domestic violence. But no charges have been filed in federal court against anyone in connection with her death. Since 2013, the Aldriches say they have called tribal police dozens of times after Ashlea’s longtime boyfriend assaulted her. Native American women experience disproportionately high rates of violence, with more than 55 percent reporting that intimate partners have committed physical violence against them, according to a 2016 National Institute of Justice-funded study. “The court system and our law enforcement never protected my daughter. I’m going to make sure nobody ever forgets what happened to her,” Galen said. Last month, The Journal obtained a copy of Ashlea’s death certificate from Nebraska’s Office of Vital Records. The document, filed on Jan. 17, 2020, lists the immediate cause of death as “hypothermia complicating acute alcohol toxicity” and the manner of death is listed as an “accident.” Ashlea was “found deceased after she wandered off.” The time of death is unknown, according to the document. The FBI has not made public information about how Ashlea died. When The Journal asked about Ashlea’s cause of death, Amy Adams, a spokeswoman for the FBI’s Omaha office responded, “The FBI can neither confirm nor deny an investigation.” After the Douglas County Coroner in Omaha performed an autopsy, Ashlea’s parents said they viewed her body at Munderloh-Smith Funeral Home in Pender. Before the viewing, Galen said he met with an FBI agent who told him there was no evidence that his daughter had been strangled or sexually assaulted and there was no bruising on her body. “She had a black eye, her nose was swollen and there were little welts all over her,” Galen told The Journal in January 2020. After the viewing, Galen said he called an FBI agent and told him about the injuries he observed on his daughter’s body. He said the agent attributed the marks to the way Ashlea’s body was lying on the ground. Galen said he disagreed with that assessment and told the agent so. Ashlea Aldrich is shown in a photograph that was printed on the front of her funeral program. Her mother said she was creative and liked to do hair and makeup. Aldrich family photo During the interview, Tillie said Ashlea was found with no clothing, socks or shoes, less than a quarter mile from where she lived with her boyfriend. Tillie said Ashlea’s sister, Alyssa, who discovered Ashlea lying in the field, observed mud all over Ashlea’s back, which stretched down to her calves. However, Tillie said an FBI agent later told her Ashlea had no soil or abrasions on her feet. “It was hard to even wrap my head around anything,” she said at the time. After receiving Ashlea’s death certificate last month, The Journal contacted Tillie. She said she feels “betrayed and neglected by the FBI.” “The agent who originally investigated was negligent and clearly wanted a quick, closed case. There are too many unanswered questions,” she said. On Jan. 7, 2021, the first anniversary of when Ashlea’s body was found, dozens gathered at the Walthill Fire Hall and a bridge near the site to pray, sing and remember her. “Even we couldn’t protect her,” Tillie said at the fire hall. “The law enforcement can’t protect her. None of our laws can protect her. That’s what we’re fighting for. We’re fighting for justice, so that we’ll never have another Ashlea. I can’t bear any of my tribal members to go through what I went through this last year.” Over the past year, candlelight vigils have been held in Ashlea’s memory on the reservation and in Lincoln, Nebraska. In a display of solidarity, a group of Walthill High School cheerleaders even stood with red handprints painted across their mouths during a basketball game. Red handprints have come to symbolize missing and murdered Indigenous women and relatives. Judi gaiashkibos, executive director of the Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs (NCIA), stated in a report published May 21 that the reservation saw a “wave of suicides among teenagers” in the aftermath of Ashlea’s death. “This was a clear sign of the desperation that can rise up during times of tragedy in a profound and dangerous way in communities that feel isolated and hopeless,” she wrote in the report, which was the result of an NCIA and Nebraska State Patrol study on the prevalence of missing Native American women and children in the state. Gwen Porter, a member of the Omaha Tribal Council, acknowledged that the tribe has faced one crisis after another, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, with methamphetamine, suicide and domestic violence. “It hasn’t broken us, but we’ve been dealing with it. Having people and other communities to reach out and support us during our time of need is what has gotten us through,” she said. ‘Fully investigated and prosecuted’ When Ashlea’s body was found on the reservation, the Thurston County Sheriff’s Office said federal authorities were in charge of the investigation. Although the FBI had a team onsite, they would not confirm that they were investigating a death or the location. More than nine months later, when The Journal asked her if the FBI was investigating Ashlea’s death, Adams responded, “The FBI investigates cases in tandem with the Omaha tribal police. The FBI has spoken directly to Ashlea Aldrich’s family with respect to the outcome of our investigation.” According to a background inquiry filed Feb. 10, 2020, in Omaha Tribal Court, three days after Ashlea’s body was found, her boyfriend was charged with criminal homicide, criminal contempt, and duty to give information and render aid. Tillie said he was held at the tribe’s detention facility in Macy, but then, in April, he was released. The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Nebraska has jurisdiction over major crimes committed on the Omaha, Winnebago and Santee Sioux reservations. While Assistant U.S. Attorney Michael Norris told The Journal he cannot comment on specific cases and investigations, he said his office is “confident” that the homicides that have occurred on Nebraska reservations were “fully investigated and prosecuted.” “We are not aware of any homicides that were not investigated or not prosecuted,” he said. “We can’t ethically file charges when the evidence does not support a charge of homicide.” Porter said she feels “there was due process” concerning Ashlea’s boyfriend, but she said “there’s a lot of unanswered questions.” She said the situation has been difficult for her, since she has close ties to both Ashlea and her boyfriend. “I grew up with Ashlea. She was a niece. Her auntie is my best friend, so I babysat Ashlea. We’ve had outings together. We went to birthday parties and went to the lake,” she said. “For the (boyfriend), I also babysat him, too. He’s my nephew, distantly. We all know each other. We’re all connected in one way or another.” Tillie described Ashlea as shy, but always smiling and happy. “She was just a little scrapper,” Tillie said with a chuckle, as she sat at her kitchen table behind a flickering purple candle on Jan. 21, 2020, just a couple weeks after Ashlea’s death, thinking about Ashlea as a child. “She was just aggressive when it came to her sisters, because she was so tiny. She always fought harder when they wrestled or did anything.” Tillie said her daughter was also very creative and artistic. Ashlea liked to draw and do hair and makeup. After graduating from Omaha Nation High School in 2009, Ashlea studied cosmetology at La James International College in Fremont, Nebraska. She received her diploma from La James in 2010. The following year, Tillie was diagnosed with breast cancer and the Aldriches also lost their home to flooding. They moved to a small three-bedroom apartment in the middle of Macy. “We all struggled through that,” Tillie said. “I think that’s when I started to lose her. When I was busy fighting cancer, she was drifting away and getting into a relationship.” Tillie Aldrich, at home with her husband Galen, said she feels “betrayed and neglected by the FBI.” Tim Hynds, Sioux City Journal Support Local Journalism Your membership makes our reporting possible. featured_button_text Ashlea reconnected with her boyfriend, whom she had dated in high school. They had two sons, but their relationship was marred by violence, according to the Aldriches, who approached the Omaha Tribal Council about the matter. In an email sent June 9, 2017, to council members, Tillie detailed a June 3 incident in which she found Ashlea standing in the shower of the apartment where she lived with her boyfriend fully clothed and covered in blood. Tillie wrote that the couch was also “soaked with blood” and that there were “splatters on the wall and mattress.” According to the background inquiry, Ashlea’s boyfriend was charged in Omaha Tribal Court with domestic disturbance and two counts of endangering the welfare of a child on June 3, 2017. Those charges were dismissed later that August. The document also lists four domestic abuse charges for four separate incidents that occurred in 2013, 2014 and 2016. It is unknown from the document whether any of those cases involved Ashlea. The charges were either dismissed, reduced or, in one instance, the boyfriend was found not guilty. “As many times as we’ve turned him in, nothing has ever happened to him,” Tillie said. Since Ashlea’s death, Porter said roles have changed on the reservation. The tribe has a new attorney general, prosecutor and chief of police. She said the tribe is reviewing its judicial system and providing community training to respond to incidents of domestic violence. “It has our attention. We’ve been taking action,” she said. The Aldriches said they made it clear to Ashlea they would be there for her no matter what and she always had a room in their home. Galen said Ashlea struggled with alcohol use the last two years of her life. He said she was drinking daily and losing a lot of weight. During the summer of 2019, Tillie noticed that when her daughter would leave her boyfriend and come home, each time, she was staying longer. Ashlea laid on the floor and read books with her sons, who have been in the Aldriches’ care since July 2018, or worked on jigsaw puzzles with them. “(Ashlea) was always so content with them,” Tillie said, voice quaking, as tears streamed down her cheeks. “That was her happiness. She didn’t even need anything else.” Tillie Aldrich, right, hugs Aurelia Robinson during a memorial service for Aldrich’s daughter, Ashlea Aldrich. Jesse Brothers That September, Tillie took her daughter to New Town, North Dakota, where her sister lives. During the visit, Ashlea conquered her fear of heights. She sent her mother a photo of her standing on a ledge overlooking a lake. “She was just proud of the picture. ‘I did it, Mom. I faced the fear. I feel so much better,'” Tillie recalled. Before Thanksgiving, Ashlea went to a detox center in Omaha. She stayed four days and then sought a bed at an inpatient treatment facility. But, Galen said she never got into treatment because of the long waiting list. Ashlea returned to the reservation. Not long after Thanksgiving, Tillie heard Ashlea had been hurt. She said she called the tribal police department and was told Ashlea had been taken to Twelve Clans Unity Hospital’s emergency department in Winnebago. When Tillie saw Ashlea at the hospital, she said Ashlea’s fingers were purple and that one of her fingernails was coming off. She said Ashlea told her her hand was slammed in a vehicle’s door. Ashlea stayed at her parents’ home most of December. On Christmas Eve, Ashlea’s boyfriend came by to give her a mobile phone. Tillie told her daughter the gift was his way of keeping track of her. Ashlea was excited about the phone, nonetheless. Another present she really liked was a forest green winter coat with brown fur that her father picked out for her. “She put it on and she fit it just right. She was just happy with it,” Tillie said. Around 2:30 a.m. on Dec. 26, Tillie said Ashlea came into the living room and put on the coat. As Ashlea was about to go outside to smoke a cigarette, Tillie told her daughter, “Ashlea, don’t leave.” Not long after Ashlea walked out the back door, Tillie saw the headlights of a vehicle. Ashlea was gone. Tillie quickly got in her black Kia Sportage and headed to Macy, where she found Ashlea and her boyfriend. She said she told Ashlea she was scared for her safety, but Ashlea reassured her she was OK. Ashlea stood by the front passenger door of Tillie’s vehicle and said through the rolled-down window, “I love you, Mom.” Tillie replied, “I love you, Ash,” and then drove away. The evening of Monday, Jan. 6, Tillie couldn’t stop thinking and worrying about Ashlea on her way to work in West Point, Nebraska. Earlier, she received a text from Alyssa, informing her that someone saw Ashlea “beat-up” in the passenger seat of her boyfriend’s SUV on Sunday. As the setting sun painted the sky a blaze of orange, purple and pink, Tillie, who works as a certified nursing assistant, stopped her car, took some sage out of the glove compartment, burned it and said a prayer for her daughter. She asked God to watch over Ashlea and keep her safe. The next day, Galen said he was performing tribal home maintenance work, when he spotted the SUV that Ashlea’s boyfriend drove parked in a cornfield in the area of Main Street and Blackbird Creek, just south of Macy. He said he looked inside the vehicle and walked around it. “I could see her tracks where she got out kind of going around the front of the truck. I could see his tracks, but I really couldn’t tell which way they went,” he said. “Then, I had that feeling – I knew something was wrong.” Galen Aldrich said he is going to make sure that no one forgets what happened to his daughter, Ashlea Aldrich. Jesse Brothers, Sioux City Journal Galen went over to a nearby concrete bridge. He walked underneath the bridge, and, when he came back up, he said he saw Ashlea’s boyfriend pull up in a vehicle. He asked, “Where’s my daughter? When’s the last time you’ve seen her?” Galen said Ashlea’s boyfriend told him he hadn’t seen her since Sunday, when his SUV got stuck in the mud. Ashlea allegedly went to find help, while he stayed in the SUV. After the encounter with Ashlea’s boyfriend, Galen headed to the tribal police department to speak with then-Omaha Nation Police Captain Ed Tyndall. While he was there, he heard a dispatcher call for officers to respond to a female screaming for help south of town. He immediately took off for the site. Just minutes earlier, at roughly 3 p.m., Alyssa was looking for her sister when she spotted the SUV Ashlea’s boyfriend drove parked in the field. Tillie said Alyssa looked around the SUV, but then she began walking toward an opening in the trees. That’s when she saw Ashlea’s long black hair blowing in the wind. Tillie said Alyssa ran to her sister’s naked body, which was lying facedown on the ground more than 100 yards north of the SUV. Alyssa tried to rouse Ashlea, but she was cold and stiff. She took off her coat, placed it over her sister and laid next to her until law enforcement arrived. When Tillie reached Macy, she saw squad cars, the SUV parked in the field and a white cover lying on the ground. She screamed and ran toward the white cover, until Tyndall stopped her. “I said, ‘Is that my baby?’ He said, ‘Tillie, you can’t come here. This is a crime scene,'” Tillie recalled Tyndall telling her. “He kept pushing me back and I kept fighting it.” Tillie said the FBI collected soil from her daughter’s body and the ground she laid on. She said those samples were sent to the FBI’s crime laboratory in Quantico, Virginia, along with Ashlea’s fingernail clippings. “I voiced my concern to deaf ears,” she said. “If anybody listened then, I believe my daughter would still be here.” A SPECIAL JOURNAL REPORT: Native women face epidemic of violence A SPECIAL JOURNAL REPORT: Questions surrounding death of Omaha Nation woman remain Dialysis unit slated to open in Walthill Twelve Clans Unity Hospital offering inpatient care Subscribe to our Daily Headlines newsletter. Source link Orbem News #Alyssa #anatomy #ashleaaldrich #Charge #criminallaw #Death #domesticviolence #Family #full-longform #galenaldrich #gwenporter #Journal #Justice #Law #lawenforcement #macy #Medicine #mmiw #omahatribeofnebraska #Report #seeking #special #SUV #suvashlea #tilliealdrich #womans #Year

0 notes

Text

INTEGRITY: The imperfect path toward a more perfect union starts at home

In January of 2020, students at Darien High School entered faculty offices on a Saturday and took photos of answers to two sophomore exams, one in English and one in Social Studies. The information was then widely distributed over social media, implicating about 300 students.

In December of 2020, 73 cadets at West Point were accused of cheating on a calculus exam at the US Military Academy, where an honor code requires students to pledge that they “will not lie, cheat, steal, or tolerate those who do.” The majority of the students involved (55 of them) had actually been enrolled in a program designed to be an “honor code boot camp” as a second chance.