#yuan ji ink

Text

felt like practicing my

fancy stuff

thanks to @theshitpostcalligrapher posting a "no" the other day

311 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fashiontober Day 3 — Hisui

Ink: Yoseka x Ink Institute Yuan Ji Blue

#illustration#callingfeather ocs#my ocs#ocs#story#oc#original art#blue#inkdrawing#ink#drawing challenge#drawtober 2022#31 day challenge#pen drawing#cool guy#cool jacket#heart#lungs#ribs#fashiontober#fashion#yoseka#ink institute#fountain pen

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

How To Name Your Chinese Characters:

1) LAST NAMES:

I’ve pasted the Top 100 common last names in alphabetical order, and bolded the ones that appear in CQL:

B: 白 Bai

C: 蔡 Cai ; 曹 Cao ; 常 Chang ; 曾 Ceng ; 陈 Chen ; 程 Cheng ; 崔 Cui ;

D: 戴 Dai ; 邓 Deng ; 丁 Ding ; 董 Dong ; 杜 Du ;

F: 范 Fan ; 方 Fang ; 冯 Feng ; 付 Fu ;

G: 高 Gao ; 葛 Ge ; 龚 Gong ; 顾 Gu ; 郭 Guo ;

H: 韩 Han ; 何 He ; 贺 He 洪 Hong ; 侯 Hou ; 黄 Hua ; 胡 Hu ;

J: 贾 Jia ; 蒋 Jiang ; 姜 Jiang ; 江 Jiang ; 金 Jin ;

K: 康 Kang ;

L: 赖 Lai ; 李 Li ; 黎 Li ; 廖 Liao ; 梁 Liang ; 林 Lin ; 刘 Liu ; 陆 Lu ; 卢 Lu ; 路 Lu ; 吕 Lü ; 罗 Luo ;

M: 马 Ma ; 麦 Mai ; 毛 Mao ; 孟 Meng ;

N: 倪 Ni ; 牛 Niu ;

P: 潘 Pan ; 彭 Peng ;

Q: 钱 Qian ; 秦 Qin ; 邱 Qiu ;

R:任 Ren ;

S: 邵 Shao ; 沈 Sheng ; 史 Shi ; 石 Shi ; 施 Shi ; 宋 Song ; 苏 Su ; 孙 Sun ;

T: 陶 Tao ; 谭 Tan ; 唐 Tang ; 田 Tian ;

W: 万 Wan ; 王 Wang ; 汪 Wang ; 魏 Wei ; 吴 Wu ;

X: 邢 Xing ; 夏 Xia ; 蕭 Xiao ; 谢 Xie ; 徐 Xu ; 许 Xu ; 薛 Xue ;

Y: 阎 Yan ; 严 Yan ; 杨 Yang ; 姚 Yao ; 叶 Ye ; 余 Yu ; 于 Yu ; 袁 Yuan ;

Z: 张 Zhang ; 赵 Zhao ; 郑 Zheng ; 钟 Zhong ; 周 Zhou ; 朱 Zhu ; 庄 Zhuang ; 邹 Zou ;

Above are all single character last names, but there are some double character Chinese last names, seen below (list not exhaustive):

独孤 Du’Gu ;

公孙 Gong’Sun ;

南宫 Nan’Gong

欧阳 Ou’Yang ;

司马 Si’Ma ; 上官 Shang’Guan ;

宇文 Yu’Wen ;

长孙 Zhang’Sun ; 诸葛 Zhu’GE ;

2) GIVEN NAMES/COURTESY NAMES

《Elements》:

Light*: 光 (guāng) - light, 亮 liàng - bright / shine, 明 (míng) - bright, 曦 (xī) - early dawn, 昀 (yún) - daylight, 昭 (zhāo) - light, clear,照 (zhào) - to shine upon,

Fire: 焰 (yàn) - flames, 烟 (yān) - smoke,炎 (yán) - heat/burn, 烨 (yè) - dazzling light,

Water: also see “weather” OR “bodies of water” under nature; note the words below while are related to water have meanings that mean some kind of virtue: 清 (qīng) - clarity / purity, 澄 (chéng) - clarity/quiet, 澈 (chè) - clear/penetrating, 涟 (lián) - ripple, 漪 (yī) - ripple, 泓 (hóng) - vast water, 湛 (zhàn) - clear/crystal, 露 (lù) - dew, 泠 (líng) - cool, cold, 涛 (tāo) - big wave,泽 (zé),浩 hào - grand/vast (water),涵 (han) - deep submergence / tolerance / educated

Weather: 雨 (yǔ) - rain, 霖 (lín) - downpouring rain, 冰 (bīng) - ice, 雪 (xuě) - snow, 霜 (shuāng) - frost

Wind: 风 (fēng) - wind

* some “Light” words overlap in meaning with words that mean “sun/day”

《Nature》:

Season: 春 (chūn) - spring, 夏 (xià) - summer, 秋 (qíu) - aumtum, 冬 (dōng) - winter

Time of Day: 朝 (zhāo) - early morning / toward, 晨 (chén) - morning / dawn, 晓 (xiǎo) - morning, 旭 (xù) - dawn/rising sun,昼 (zhòu) - day,皖 (wǎn) - late evening,夜 (yè) - night

Star/Sky/Space: 云 (yún) - cloud,天 (tiān) - sky/ heaven,霞 (xiá) - afterglow of a rising or setting sun,月 (yuè) - moon,日 (ri) - day / sun,阳 (yáng) - sun,宇 (yǔ) - space,星 (xīng) - star

Birds: 燕 (yàn) - sparrow, 雁 (yàn) - loon, 莺 (yīng) - oriole, 鸢 (yuān) - kite bird (family Accipitridae),羽 (yǔ) - feather

Creatures: 龙 (lóng) - dragon/imperial

Plants/Flowers:* 兰 (lán) - orchids, 竹 (zhú) - bamboo, 筠 (yún) - tough exterior of bamboos, 萱 (xuān) - day-lily, 松 (sōng) - pine, 叶 (yè) - leaf, 枫 (fēng) - maple, 柏 bó/bǎi - cedar/cypress, 梅 (méi) - plum, 丹 (dān) - peony

Mountains: 山 (shān), 峰 (fēng) - summit, 峥 (zhēng),

Bodies of water: 江 (jiāng) - large river/straits, 河 (hé) - river, 湖 (hú) - lake, 海 (hǎi) - sea, 溪 (xī) - stream, 池 (chí) - pond, 潭 (tán) - larger pond, 洋 (yáng) - ocean

* I didn’t include a lot of flower names because it’s very easy to name a character with flowers that heavily implies she’s a prostitute.

《Virtues》:

Astuteness: 睿 ruì - astute / foresight, 智 (zhi), 慧 (hui), 哲 (zhé) - wise/philosophy,

Educated: 博 (bó) - extensively educated, 墨 (mo) - ink, 诗 (shi) - poetry / literature, 文 (wén) - language / gentle / literary, 学 (xue) - study, 彦 (yàn) - accomplished / knowledgeable, 知 (zhi) - to know, 斌 (bīn) - refined, 赋 (fù) - to be endowed with knowledge

Loyalty: 忠 (zhōng) - loyal, 真 (zhēn) - true

Bravery: 勇 (yǒng) - brave, 杰 (jié) - outstanding, hero

Determination/Perseverance: 毅 (yì) - resolute / brave, 恒 (héng) - everlasting, 衡 (héng) - across, to judge/evaluate,成 (chéng) - to succeed, 志 (zhì) - aspiration / the will

Goodness/Kindness: 嘉 (jiā) - excellent / auspicious,磊 (lěi) - rock / open & honest, 正 (zhèng) - straight / upright / principle,

Elegance: 雅 (yǎ) - elegant, 庄 (zhuāng) - respectful/formal/solemn, 彬 (bīn) - refined / polite,

Handsome: 俊 jùn - handsome/talented

Peace: 宁 (níng) - quietness/to pacify, 安 (ān) - peace, safety

Grandness/Excellence:宏 (hóng) - grand,豪 (háo) - grand, heroic,昊 (hào) - limitless / the vast sky,华 (huá) - magnificent, 赫 (hè) - red/famous/great, 隆 (lóng) - magnificent, 伟 (wěi) - greatness / large,轩 (xuān) - pavilion with a view/high,卓 (zhuó) - outstanding

Female Descriptor/Virtues/Beauty: 婉 (wǎn),惠 (huì), 妮 (nī), 娇 (jiāo), 娥 (é), 婵 (chán) (I didn’t include specific translations for these because they’re all adjectives for women meaning beauty or virtue)

《Descriptors》:

Adverbs: 如 (rú) - as,若 (ruò) - as, alike,宛 (wǎn) - like / as though,

Verbs: 飞 (fēi) - to fly, 顾 (gù) - to think/consider, 怀 (huái) - to miss, to possess, 落(luò) - to fall, to leave behind,梦 (mèng) - to dream, 思 (sī) - to consider / to miss (someone),忆 (yì) - memory, 希 (xī) - yearn / admire

Colours: 红 (hóng) - red, 赤 (chì) - crimson, 黄 (huàng) - yellow, 碧 (bì) - green,青(qīng) - azure,蓝 (lán) - blue, 紫 (zǐ) - violet ,玄 (xuán) - black, 白 (baí) - white

Number:一 (yī), 二 (er) - two, 三 (san) - three, 四 (si) - four, 五 (wu) - five, 六 (liu) - six, 七(qi) - seven, 八 (ba) - eight, 九 (jiu) - nine, 十 (shi) - ten

Direction: 东 (dōng) - east, 西 (xi) - west, 南 (nan) - south, 北 (bei) - north,

Other: 子 (zǐ) - child, 然 (rán) - correct / thusly

《Jade》: *there are SO MANY words that generally mean some kind of jade, bc when ppl put jade in their children’s name they don’t literally mean the rock, it’s used to symbolize purity, goodness, kindness, beauty, virtue etc*

琛 (chen), 瑶 (yao), 玥 (yue), 琪 (qi), 琳 (lin)

《Spirituality》

凡 (fan) - mortality

色 (se) - colour, beauty. In buddhism, “se” symbolizes everything secular

了 (liao) - finished, done, letting go

尘 (chen) - dust, I’m not… versed in buddhism enough to explain “chen”, it’s similar to “se”

悟 (wu) - knowing? Cognition? To understand a higher meaning

无 (wu) - nothing, the void, also part of like “letting go”

戒 (jie) - to “quit”, but not in a bad way. In buddhism, monks are supposed to “quit” their earthly desires.

极 (ji) - greatness, also related to the state of nirvana (? I think?)

#cql#the untamed#because i have gotten many many many asks about how to name characters#language#master list

11K notes

·

View notes

Photo

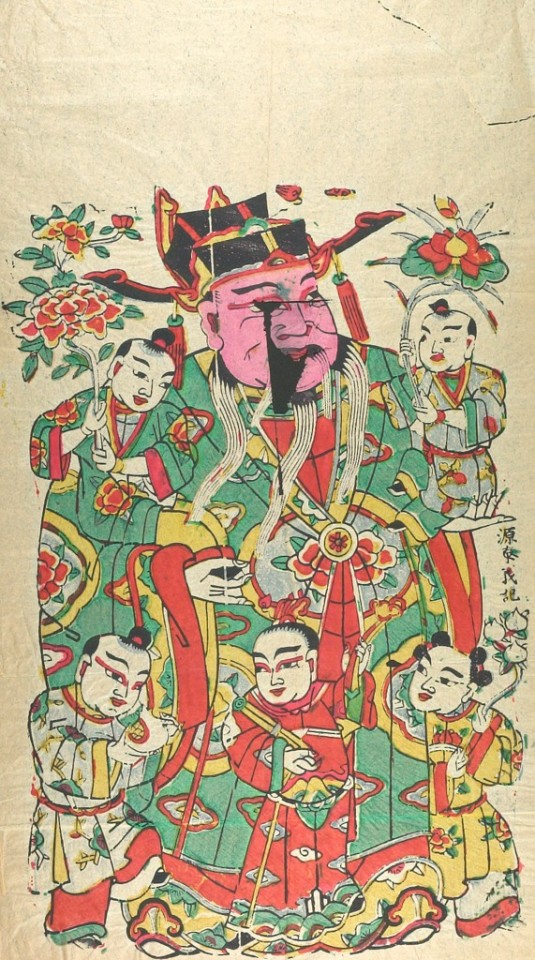

Door God: Heavenly Official with Five Sons, early 20th century, Harvard Art Museums: Prints

Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of Langdon Warner

Size: paper: 71.2 x 41 cm (28 1/16 x 16 1/8 in.)

Medium: Woodblock print; ink and color on paper; with printed shop inscription reading "Yuan Tai Yi Ji" (probably the print shop name). Probably from Xinjiang, Shanxi; possible pair with 1935.36.1.

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/206303

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Happy Lunar New Year!

To celebrate the Lunar New Year, we’re presenting a banquet scene from a facsimile scroll titled "Night Revels of Han Xizai (韩熙载夜宴图)"

韓熙載夜宴圖

Han Xizai ye yan tu

顧閎中 ; [北京汲鼎文化发展有限公司复制].

Gu Hongzhong ; [Beijing ji ding wen hua fa zhan you xian gong si fu zhi].

Author / Creator

顧閎中, active 10th century, artist.

Gu, Hongzhong, active 10th century [artist]

[北京] : [北京汲鼎文化发展有限公司], [2017?]

[Beijing] : [Beijing ji ding wen hua fa zhan you xian gong si], [2017?]

1 scroll : color illustrations ; painting 28.7 x 335.5 cm, mounting 28.7 x 691 cm, rolled to 29 x 8 cm in diameter, box 8.5 x 10.5 x 33 cm

Chinese

"Zhongguo li dai chuan shi shu hua jing pin dian cang shou juan wu dai gu hong zhong" --case.

Original owning institution: Beijing gu gong bo wu yuan.

East Asian binding [juan zhou zhuang], in case.

Handscroll, Ink and colors on silk, wrapped in satin and kept in a woodern box.

HOLLIS number: 990153149680203941

#lunarnewyear#chineseart#facsimile#scroll#harvardfineartslibrary#harvardfineartslib#fineartslibrary#Harvard#harvard library#HarvardLibrary

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Annals of Zhengshi 2 (505)

[From WS008. Including the adventures of Wang Zu.]

[Zhengshi 2, 19 February 505 – 8 February 506]

2nd Year, Spring, 1st Month, bingzi [23 February], used the Heir to the state of Dangchang, Liang Mibo, as the King of his state.

The state of Dengzhi dispatched envoys to court with tribute.

2nd Month [21 March – 18 April], the Di of Liang# province rebelled and cut off Hanzhong's transport roads. The Inspector Xing Luan again and again greatly routed them.

Summer, 4th Month, jiwei [6 June], the King of Chengyang, Luan, passed away.

On yichou [12 June], a decree said:

Relying on the worthy to clarify good order has been passed through in the counsels from the past. Circulating their manners to help in applying themselves in truth are indeed the many gentlemen. Yet [those] assessed by the Central Correctors only live inside gates and mansions, the personnel section's moral laws and human relationships still do not bring up talent. Thereupon they make the gallant and virtuous scarcely promoted, and the ministers apply themselves to many blockages. Not concentrating on their selection, how might they examine their progress? The Eight Seats can thoroughly discuss former eras' methods for commending gentlemen, and framework for drawing up the worthy, and certainly cause the talented and schooled to equally stretch out.

On bingyin [13 June], since the Di of Chouchi were rebellious, decreed the Brilliantly Blessed Grandee Yang Chun as provisional General who Pacifies the West, to lead the multitudes to chastise them.

Xing Luan dispatched the Army Director Wang Zu on a western offensive. He again and again routed Xiao Yan's various armies, and thereupon entered Jiange. He seized Yan's General Fan Shi'nan, and sent him off to the Imperial City.

5th Month, xinsi [28 June], the Di thief [lacuna] Hu led the multitudes to surrender.

6th Month, jichou [6 July? In the 5thMonth], a decree said:

The previous court's merited subjects sometimes personally had the misfortune to be reprimanded and demoted, their sons and grandsons were sunk and obstructed. Sometimes the route of officialdom neglected the sequence, and was putting aside the old flow. To follow that and not select, how then to encourage and motivate?

When talking of and recalling previous achievements, [we] feel there are those close and those far apart. For the [imperial] lineage and commoner families, those whose grandfathers and great grandfathers' merits and achievements can be chronicled but have no court offices, and those who have offices and talent and ability are copiously brought forth, pursue talent when assessing conferrals.

On jiayin [31 July], Xiao Yan's General of the Best of the Army, Li Tian, and others set up camps east of Shiping commandery and north of Fu River. Wang Zu confronted, struck, and defeated them. He beheaded Yan's General of the Best of the Army, Zhang Tang, General who Assists the State, Ma Shi, Generals who Soothes the Boreal, Li Dang and Jiang Jianzu, General who Assists the State, Feng Wenhao, Dragon Prancing General, He Yingzhi, and others.

On jiazi [10 August], decreed the Master of Writing Li Chong, the Grand Treasurer Vassal Yu Zhong, the Cavalier Regular Attendant You Zhao, the Remonstrating Consultant Grandee Deng Xian; that Chong and Zhong [being] Envoys Holding the Tally and also Combined Palace Attendants, Xian Combined Yellow Gates, everyone to be Great Envoys, and bring together and pass judgement on the outer provinces and inside of the imperial demesne. If there were those of their groups of wardens and prefects who were blamed for neglecting to clearly display and lay bare, they were to readily carry out judgement. Provinces and garrisons with heavy duties were to take heed to make it known.

On yichou [11 August], Xiao Yan's General of the Best of the Army, Wang Jingyin, General who Assists the State, Lu Fangda, and others attacked Zhuting. Wang Zu greatly routed them, and beheaded their General who Assists the State, Wang Jingyin, and Dragon Prancing General Zhang Fangchi.

On dingmao [13 August], the Inspector of Yang province, Xue Zhendu, greatly routed Xiao Yan's general Wang Chaozong, and took prisoner and beheaded 3 000.

On wuchen [14 August], Xiao Yan's general Lu Fangda stationed at Shuxin City [?]. Zu again dispatched the Army Director Lu Zuqian and others to strike and defeat him. They beheaded Yan's General of the Best of the Army Yang Boren and General who Soothes the Boreal, Ren Anding.

Autumn, 7th Month, jiaxu [20 August], a decree said:

Us succeeding to steering the treasured series is now in the 7thyear. Virtue and beneficence is not yet spreading, and discernment does not illuminate the distant. A person's illness from injustice is what is still propagating. And yet the litigations from investigations and examinations are not unimpeded among the subordinates, the worthy and stupid are not separated, ink-black and white are equally threaded together, not the means by which to change the people's ears and eyes, and make good and evil encourage their hearts.

Now allot and dispatch the Great Envoys, to scrutinize the regions, tour and investigate. In due course, if their mistakes and demerits and the sound of their manners are fitting together, then rectify and demote, to thereby clarify the awesomeness of a thunderclap, and to unroll the elevation of the yak-tail coach. Following that, on observing the manners and telling apart customs, gather and inquire into merits and transgressions, praise and award the worthy, investigate and penalize the excessive and depraved, attend to the poor and care for the ill-treated, and so declare Our heart.

On wuzi [3 September], Wang Zu struck and routed Xiao Yan's army, and beheaded his Dragon-Prancing General Yu Zenghui, General who Soothes the Boreal Ku Baoshou, General who Assists the State Lu Tianhui, General who Establishes the Martial Wang Wenbiao.

Wang Zu pressured Fucheng.

On renchen [7 September], Xiao Yan's Grand Warden of Baxi Yu Yu, General of the Best of the Army and Master of Army Directors Li Tian, and others confronted him in battle. Zu struck and routed him. The prisoners and beheaded numbered a thousand.

8th Month, renyin [17 September], decreed the King of Zhongshan, Ying, to go south and chastise Xiang and Mian.

On gengxu [25 September]. Wang Zu dispatched the Army Directors Ji Hongya and Lu Zuqian and others to attack and rout Yan's army. They beheaded his Inspector of Qin and Liang# provinces, Lu Fangda and others, fifteen people.

On renzi [27 September], Wang ZU again dispatched Army Director Lu Zuqian and others to rout Yan's army. They beheaded his Chief Controller and General of the Best of the Army, the State-Founding Count ofZitong county, Wang Jingyin, Liu Da, and others, twenty-four generals.

On jiayin [29 September], Yang province struck Yan's general Jiang Qingzhen at Yangshi, and routed him.

This Month [14 September – 13 October], Yan's Grand Warden of Miandong, Tian Qingxi, led 7 commanderies, 31 counties, and 10 090 households to adhere within.

9th Month, jisi [14 October], the Inspector of Yang province, Yuan Song, struck and routed Yan's Inspector of Xiang province, Yang Gongze, and others, and beheaded and captured several thousand.

Winter, 11th Month, wuchen, New Moon [12 December], the King of the state of Wuxing, Yang Shaoxian's junior uncle Jiqi planned rebellion. Decreed the Brilliantly Blessed Grandee Yang Chun to chastise him.

Wang Zu besieged Fucheng. The various commanderies and defence posts in Yi province who surrendered were twenty-three, the people who sent off their records and registers were more than 50 000 households. Then Zu pulled in the army and withdrew.

12th Month, gengshen [2 February], also decreed the Great General of Agile Cavalry, Yuan Huan to be careful, and ordered him to chastise the rebelling Di of Wuxing.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Basically an Essay about Lian Song, Shhhhhhhhh.

Lian Song’s age, why he’s the youngest son of Tianjun, how Donghua referred to him as a prodigy

At the start of Lotus Step Lian Song is 40,000 years old, which to give a timeline for this is post Mo Yuan’s “death” by 20,000 years, set a bit after the failed arranged marriage between his second brother now former crown prince Sang Ji and Bai Qian, and 50,000 years before the current timeline of Ten Miles of Peach Blossoms and The Pillowbook.

The official youngest child of The Heavenly King Tianjun, his father had decided by the influence of Donghua that Lian Song would be his final child as Donghua said he would not end up with any smarter a child and thus viewed the perfect son by Tianjun. He is also the favorite of Tianjun, which gives Lian Song some wiggle room but also places a lot of pressure on him at times to continue being the perfect son. Clashing as sons and fathers do when Lian Song’s beliefs on a certain topic begin to shift leads them to entering a bet that can determine his livelihood and where his life progressed from there. Tianjun only did it for Lian Song to learn a lesson if he’s wrong because he wants the best for him, while Lian Song enters it for a somewhat selfless reason and to prove to Tianjun his conclusion is accurate.

Lian Song spent years essentially sleeping in Donghua Dijun’s library, and Donghua calls him a prodigy as time goes, with good reason. Because while Sang Ji was thought to be the most intelligent, Lian Song hadn’t messed up a spell since the age of 10,000, which roughly in mortal age for an immortal is about 5 or 6 years old. It’s likely he achieved his first lightning at some point before the age of 40,000 to hold the role of the Water God, while his great skill in battle makes Tianjun want him to take up the role of God of War left vacant by Mo Yuan at that time.

And so, for those who he deems suitable to entrust great work to, his first lesson for them must be how to be an unfeeling god. It was perhaps for this reason that Tianjun privately favored His Third Highness a little.

Straight-laced and serious first prince and upright and honest second prince seemed to be unfeeling people, but in truth had much feeling, and the unserious third prince seemed to be a man of great feeling, but never thought much of feeling and was then the most unfeeling person.

This naturally gifted youngest son, a young god who has never lost on the battlefield - even though he was a bit idle, and one could never tell what went on in his head all day, he was strong and smart, and the most remarkable thing was that there was no emotion in the world that could move him, that could bother him. To be the war god that protected the realm seemed to be the very reason for his birth.

Lian Song and his perfectionist tendencies, that Good Old Depression Mood (™), his three million hobbies.

Because of him perfecting spells by a young age, it kept the pressure on him to continuously stay at that level and beyond to his greatest ability. He always searches out knowledge, going through all the materials in Donghua’s library and what he can get his hands on, though for his own learning purposes or other reasons, it doesn’t seem to matter. Lian Song will look for it.

While some of Lian Song’s tone and words align with Buddhist beliefs --- it also reads a bit depression-like or how one might describe depression for them, where everything feels sort of void and empty and nothing quite has much meaning. He tends to come off bored, and constantly learning new things and cycling through hobbies (painting, carving, making things akin to music boxes, makes jewelry, learns how to cook during his time in the mortal realm, researching, and more) putting things down but eventually picking them up again. It’s endless but it gives him something to do.

"Everything in the world had its ebb and flow, life and death, and there is no occurrence that is permanent, no thing that is permanent, no feeling that is permanent. Everything is inconstant, and so must become nothing, and yet from nothingness is born other things, and so it must again become something, but in this ebb and flow and life and death there is nothing to hold on to, to make permanent - that is emptiness."

She didn't understand, looking at the not so distant, beautiful goddess, asking lightly: "So this moment is also empty to Your Highness? Emptiness - isn't it tedious? Does Your Highness think this moment is tedious?"

His Third Highness answered her absently as he dipped his pen into the ink: "Emptiness makes one feel tedious?" He smiled, a smile that held a hint of boredom, hanging faintly at the corners of his lips: "Not tedious," he said. "Emptiness makes one feel desolate."

His playboy life and how he Somehow No Like Touchy-Touchy. And How He Is Developing Them Emos, in which Cheng Yu is definitely different to him than other female mortals and goddesses.

The perspective of Tianbu, Lian Song’s kind of a glorified immortal housekeeper I guess you can call her, it is said for the past 10,000 years beauties and goddesses have come and gone from Lian Song’s palace, which places the third prince started his playboy days back when he was the equivalent of a mortal’s age of 15. This is the same age Bai Feng Jiu is when entangled with Donghua, which gives an interesting insight when remembering 90,000 year old Lian Song worries about what his best friend’s intentions are for the young Qingqiu princess.

He doesn’t appear too much of an active party with the goddesses or other beauties we see him interact with. It’s possible he kind of dead fished his way through things, while still both treating the women coolly yet nicely enough. A strange combo, especially when learning Lian Song does not like to be touched and best to stay several feet away.

It’s funny as he is quite touchy with Cheng Yu, in fact he does a lot of things with and for Cheng Yu that he wouldn’t normally do. Even as far as questioning himself for why he feels a desire to basically take care of her.

Lian Song also starts feeling emotions he never felt before. Unlike Yehua and Donghua who had their consciousness to the realms sealed off during their times in the mortal realm, he is immersed in his role as a human. And Cheng Yu somehow causes emotions to start blooming in his heart, not just love but immense patience, anger, sorrow, a sense of fear when he is performing a little magic for her (the small part of his powers his father couldn’t seal off) and messing up his spell to the point his hands were shaking. Cheng Yu has a definite impact on him that no one ever has before.

The slight tickling feeling made his heart move, the right hand that had been casting the spell trembling uncontrollably.

His Third Highness hadn't made a mistake casting a spell in thirty thousand or so years, not to mention, on such a simple trick.

And one mistake created a spectacle.

He [Lian Song] saw her tears rolling down to the ground, and she [Cheng Yu] cried very sadly, but those tears seemed to not sink into the ground, but sink into his heart. He couldn’t think if it was also empty, her tears were so real, and when they melted into his heart, he felt warm. He had never had such an experience.

Then an abrupt laugh was heard from Lian San. "Yes," he said. After a moment, he continued. "I do miss her very much, but I can control it and not see her. So perhaps I don't like her that much after all."

#Eternal Love#Three Lives Three Worlds#Eternal Love of Dream#three lives three worlds the pillow book#Lotus Step#Three Lives Three Worlds The Lotus Step#Lian Song#(posted by admin lin)#(translation by admin ro)#(admin ro is such a boo to translate. i love her omg)#(also im so sorry for this but also im not. lET ME LOVE THIS BOI)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

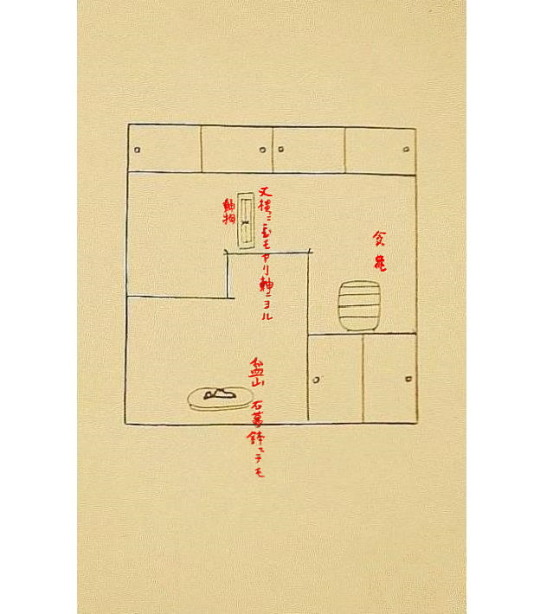

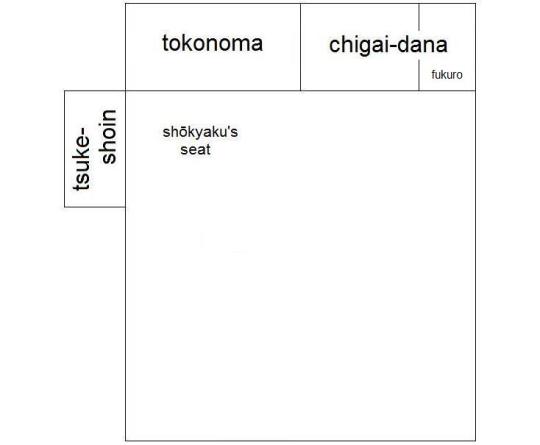

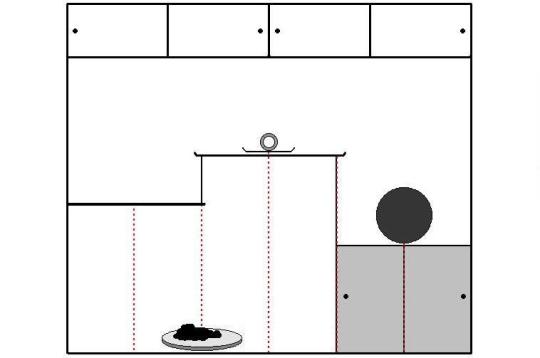

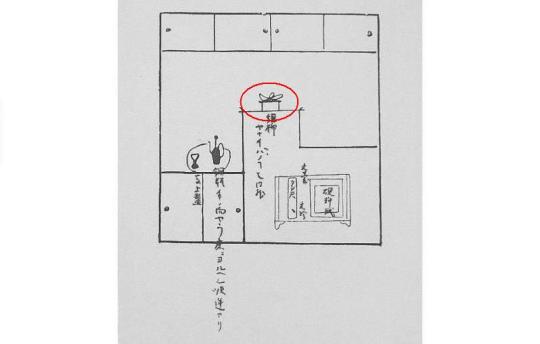

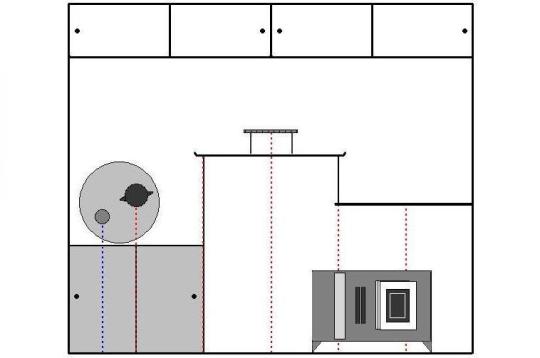

Nampō Roku, Book 4 (23.1): Six Arrangements for the Chigai-dana [違棚], Part 1.

[The writing¹ reads (from right to left, above then below): jikirō (食籠)²; mata yoko ni oki mo ari, jiku ni yoru (又横ニ置モアリ、軸ニヨル)³; jiku-mono (軸物)⁴; bon-san (盆山)⁵; sekishō-bachi ni te mo (石菖鉢ニテモ)⁶,]

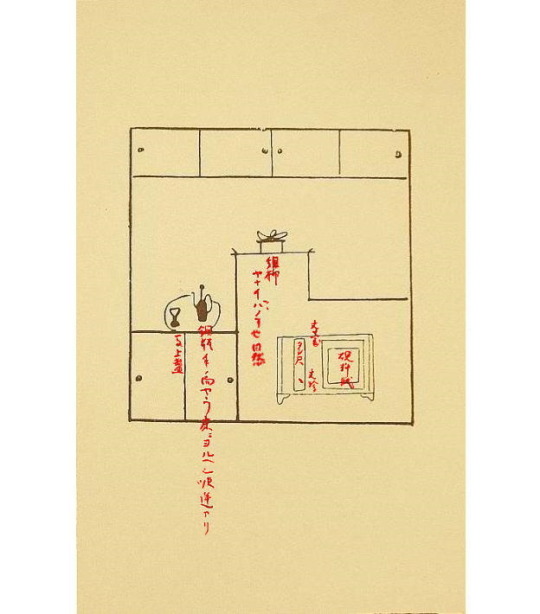

[The writing reads (from right to left): suzuri・ryōshi (硯・料紙)⁷; bun-dai (文臺)⁸; bun-chin (文珍)⁹; tanzaku (タン尺)¹⁰; kumi-yanai・yanai-ba no koto nari dōzen (組柳・ヤナイバノ事也 同然)¹¹; dō-bin・te no muki-yō toko ni yoru-beshi, jun-gyaku ari (銅瓶・手ノ向ヤウ床ニヨルヘシ、順逆アリ)¹²; bajō-san (馬上盞)¹³.]

_________________________

¹It is not entirely clear why the writing on this (and the following) sketch is in red*. Red ink was generally used to show that something was important; but heretofore only red dots have been added to indicate important words and phrases. Nevertheless, for whatever reason, from here to the end of Book Four, all of the kaki-ire [書入] were added in red ink. These sketches, the originals of which appear to have been made by Jōō, would have been part of the memorandum (based on a discussion that he overheard at one of the Shino family’s incense gatherings), which dates from near the beginning of his public career; the kaki-ire, meanwhile, clearly date from a later period.

___________

*Regarding this question, Tanaka Senshō comments: kono zu ni oite mo kō-sei no kaki-ire ōshi [此図に於ても後世の書入多し], which means “in these sketches, there are numerous kaki-ire that were added [onto the sketches] in later periods.” The implication being that most, if not all, of these apparently spurious incorporations were added to the sketches long after Jōō’s and Rikyū’s time -- and possibly even after Jitsuzan presented his manuscript to the Enkaku-ji (in which case, by members of the group of Nampō Roku scholars who congregated at that temple). That these notes are also found in the original copies of this collection, which remained in the possession of Jitsuzan’s family, is not significant, since any annotations found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript were routinely transferred to Jitsuzan’s original copy by his descendants, without comment.

At any rate, Tanaka provides us with a logical reason why these comments were written in red -- and why that practice deviates from the rest of the entries not only in this book, but in the Nampō Roku as a whole.

²Jikirō [食籠].

A jikirō [食籠] is a lidded container for food. Originally a lacquered basket (as the name suggests), jikirō ultimately came to be made of both lacquered wood and ceramics.

Classical continental examples of the jikirō are mostly carved lacquer (from China) and mother-of-pearl inlay (from Korea), probably because of considerations of weight and breakability during their journey to Japan; ceramic versions were mostly made in Japan.

The jikirō -- which had anywhere from a single to several boxes stacked on top of each other -- would have contained sweets (often dried fruit) or other foods intended as side-dishes, to be consumed when drinking tea or sake.

³Mata yoko ni oki mo ari, jiku ni yoru [又横ニ置モアリ、軸ニヨル].

The scroll could be displayed vertically or horizontally on the shelf. Orientation was determined based on the way the gedai [外題] (the paper label, pasted to the back of the scroll, indicating the name of the artist or calligrapher, and sometimes a title for the work as well) had been written*, but also because the scroll should not project over the edge of the shelf.

___________

*The primary reason why a rolled-up scroll was displayed on the chigai-dana -- other than when it was a horizontal scroll that could not be hung up in the toko -- was so that the guests could inspect the gedai. Scrolls from the Higashiyama collection usually featured gedai written by one of the great dōbō -- since these scrolls sometimes lacked an actual signature or name-seals, and so the gedai provided the only identification of the artist. Scrolls that came to be used for chanoyu later (especially calligraphic works of the bokuseki [墨跡] variety), naturally have gedai provided by other people -- some notables (such as the gedai shown below, which was written by the famous Momoyama period monk Shun-oku Sōen [春屋宗園; 1529 ~ 1611]), and some simply the original owner of the scroll.

[A scroll written by the Yuan period Chán monk Dōngyáng Déhuī (東陽德輝; dates of birth and death unknown, though his name is found in several Chán documents dated 1329, 1330, and 1335: his name is pronounced Tōyō Tehi in Japan), with the gedai, by the Japanese monk Shun-oku Sōen, shown on the right. Here, the rarely seen kanji “輝” was interpreted to be “煇” by Shun-oku oshō-sama.]

The gedai were usually marked by the seal of the person responsible for the identification (as can be seen in the above example, where Shun-oku’s seal was impressed below the name of the monk who actually wrote the document that has been mounted as a scroll) , and the dimensions of the gedai were prescribed according to a secret formula -- which is explained in the Chanoyu san-byak’ka jō [茶湯三百箇條] -- allowing an informed viewer to ascertain whether the gedai, even if authentic, had actually been made for the specific scroll to which it was attached (or made for some other and then unscrupulously moved to a different scroll when the original had suffered some sort of irreparable damage).

The text on the gedai could be written top-to-bottom (as shown in the above example), or right-to-left. In either case, it was supposed to be displayed in such a way that it was easy to read (if a vertically written inscription was displayed horizontally, the top of the text would have been on the right).

⁴Jiku-mono [軸物].

One of the generic names, in Japanese, for a scroll. In addition to kakemono [掛物], which were vertical scrolls (whether long or wide) that were intended to be hung up on the wall, the term also includes makimono [巻物], horizontal scrolls that were supposed to be opened while resting on a table, or on the floor, and usually contained a series of paintings interspersed with text.

⁵Bon-san [盆山].

A bon-san [盆山] (which means “a mountain in a tray”) is a “viewing stone” -- a natural stone that resembles a distant mountain or otherwise suggests a scene from nature. It was arranged in a shallow tray of granitic sand, which was arranged so as to enhance the impression of the scene which the stone’s natural shape suggested.

Ashikaga Yoshimasa’s treasured viewing stone known as Zan-setsu [殘雪] (“lingering snow” -- so called because of the areas of white stone found in depressions in the dark matrix), placed on the Korean sawari tray that accompanied it from the continent (albeit without any sand -- probably because granitic sand is very abrasive, and the curators did not wish to risk inflicting any further damage to the tray) is shown above.

⁶Sekishō-bachi ni te mo [石菖鉢ニテモ].

Sekishō [石菖] (Acorus gramineus) is a grass-like plant, usually known as the sweet flag in English, which naturally lives in boggy ground near the banks of streams and ponds. The original variety measures about 30 cm tall; the flower is a fairly insignificant cream-colored spathe hidden amongst the leaves. When growing in water, the roots give off a pleasantly sweet aroma when pulled out into the air, and this aroma had been considered to have purificatory properties since ancient times (the so-called “Iris Festival,” on the fifth day of the Fifth Lunar Month, was originally devoted to the appreciation of the roots of the sweet flag and their aroma, with contests held to judge the finest of these, which were then celebrated in poetry: the plants were subsequently hung up, upside down, to perfume the nobleman’s mi-chōdai during the rainy season).

Due to its presumed air-purifying properties, sekishō planted in decorative flower-pots, were frequently displayed in the shoin, especially at night (when the room is lit by candles and oil-lamps). These plants were originally cultivated in rather deep pots, of the sort commonly used for oriental miniature Cymbidium orchids today, on account of their long roots.

During the fifteenth century, a miniature variety of sekishō (A. gramineus var. pusillus) was introduced from Korea (it was native to the southern Korean island of Jeju-do [제주도 = 濟州島]). This form lends itself to being grown in shallow pots, as well as planted in pockets on volcanic stones (the semi-porous nature of which allows them to draw up water easily), such as seen above. As a result, the original species of sekishō is virtually unknown to chajin today -- since most references from the time of Yoshimasa, and after, refer to the display of the miniature variety.

In the early twentieth century it became fashionable to grow this kind of sekishō on pieces of charcoal (the piece of charcoal known as the kōgō-dai [香合台] being especially popular, since this piece was not usually used during the sumi-temae, yet a new one was provided in every commercially prepared set of cut charcoal), which were then displayed in the toko resting in a hai-ki partially filled with water (the charcoal acts like a volcanic stone, drawing water upward to the roots of the plant). In the period when the material on which Book Four of the Nampō Roku was written, however, sekishō was always planted in soil and grown in pots -- which, like most else at that time, were costly pieces imported from the continent.

The point of this note is to indicate that, while the bon-san was the preferred oki-mono during the day, it might be better to replace it with a sekishō-bachi at night.

——————————————–———-—————————————————

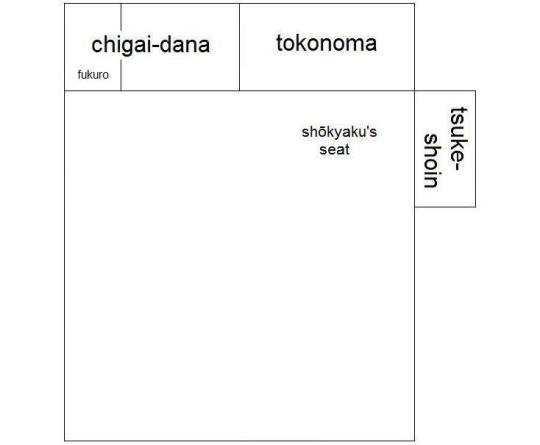

Shibayama Fugen points out that this is the proper arrangement for a mitsu-dana [三ツ棚] -- a chigai-dana with three shelves. And that we need to be aware of the jun-gyaku [順逆]* aspect of the orientation: in the case of a mitsu-dana, the fukuro-dana should be found on the lower side of the chigai-dana (that is, the side farthest away from the toko) -- this detail indicating that the orientation of the room depicted in Jitsuzan’s sketch would be as shown in the following sketch (which is in the gyaku orientation†).

Likewise, Shibayama also reminds us that the scroll is resting on a tray, as described earlier in Book Four.

Turning now to Tanaka Senshō’s commentary, after remarking on the spurious nature of the things that were written on the sketch in red ink, Tanaka discusses the content of the sketch briefly. “In certain [versions] of this book it is stated, ‘with respect to the jiku being horizontal or vertical, that this is the same as when the scroll is placed in the toko‡’ and so forth -- the argument is set out in that way.

“Likewise, in some, after it says ‘and again, there is also the case where it is placed horizontally**,’ are added the words ‘depending on the jiku††’ and so on -- these comments have also been recorded.

“In every case, the original version [of this sketch] presumably had none of this.

“If the way to place the scroll was explained in a ku-den, then that secret teaching would have stated that the jiku-mono and the jikirō should be placed on the central kane on each of their respective shelves; the bon-seki [is displayed] in the place below the shelves, with [that space] divided by kane into thirds‡‡.

“Furthermore, the ku-den concludes with the statement that nothing should be placed on the shelf above [the bon-seki]."

__________

*Jun-gyaku [順逆] refers to the orientation of the room, which is determined by the location of the tokonoma. A toko found on the guests’ right, is the jun [順] orientation; when the toko is located on their left, the room is said to have a gyaku [逆] orientation.

The toko on the guests’ right is also called a hon-doko [本床] or kami-za toko [上座床]; that on their left is likewise known as a ge-za or shita-za toko [下座床].

†The reader should remember that the terms jun-gatte [順勝手] and gyaku-gatte [逆勝手] reflect relatively modern conventions (these terms -- and the preferred orientation which the expression “jun-gatte” implies -- seem to have been defined in this way so as to reflect Hideyoshi’s desires).

Originally -- as shown in the way the Dōjin-sai [同仁齋] (above: the 2-mat tsugi-no-ma, on the right, featured an o-chanoyu-dana [御茶湯棚] for hakobi-date service, while the daisu was used when tea was prepared in the 4.5-mat shoin itself, seen on the left) was set up -- the orientation of the room where the guests sat on the host’s left was preferred. This was derived from the traditional Buddhist temple, and the arrangement of the images on the Buddhist altar, where Yakushi nyorai [藥師如來] is seated on the Buddha’s left (our right). The daisu was set up in front of the image of Yakushi nyorai (who is the patron saint of chanoyu), and the tea was placed out to the celebrant’s left, so that it could be conveyed to the altar, where it was offered to the image of Shakamuni (before being drink by one of the people present in the room, so it would not go to waste).

The picking of tea for matcha was traditionally done in the 10 days before, and the 10 days following the feast day of Yakushi nyorai (on the 88th day of the Lunar Year).

‡Kono jiku yoko tate no koto kono aida moshi age-sōrō, toko ni kakemono oki dō-zen [此軸横竪の事此間申上候、床に掛物置同然].

**Mata yoko ni oki mo ari [又横ニ置モアリ]. This is a quotation of what was presumed to be the original (or at least an earlier version of the) text.

††Jiku ni yori [軸ニヨリ]. “Depending on the jiku.” These words are found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript.

‡‡Bon-seki ha tana shita mitsu-wari no kane ni shite [盆石は棚下三ツ割の曲尺にして]. This means that “the space below the shelves is divided by three kane, with the bon-seki [placed] on one of these” -- though Tanaka does not say which one. Thus, his wording is confusing -- and suggests that he was simply repeating something that was told to him without clearly understanding the reasoning behind it. According to all of the sketches in the various manuscript copies of Book Four of the Nampō Roku, it appears that the bon-san was supposed to be centered in the space beneath the shelves (a position which corresponds to its being directly below the point where the two hanging shelves overlap), and this is how I have represented the arrangement in my sketch (above).

Now, in an attempt to clarify the confusion caused by Tanaka’s commentary: the entire recess occupied by the chigai-dana (which, in this case, includes the fukuro-dana on the right -- since, as Shibayama Fugen pointed out, this is an arrangement for a mitsu-dana [三ツ棚] -- a chigai-dana with shelves on three levels) is divided by five kane. Since the three shelves (which include the shelf formed by the roof of the fukuro-dana) are of equal length, kane are found in the middle of each shelf, as well as running through the legs that support the pair of suspended shelves (the kane are indicated by the dashed red lines in my sketch). Consequently, the middle of each of the shelves, along with the point immediately beneath the leg that connects the two suspended shelves, all match with one of the kane. The oki-mono should be distributed on these points. Nothing is placed on the left-most of the shelves because that would make the area seem filled -- and also because doing so would impact on the kane-count (presently, the three oki-mono give a han [半] -- a yang or odd -- count; adding one more object would change that count to chō [調], which is yin, or even).

That said, Shibayama Fugen has also included the following statement in his commentary: kono kazari no kane ha uwa-dana no jiku-mono ha jiku-bon ni nosete chū-ō no kane ni ari. Jikirō ha hidari-za no hashi-gane ni shite, bonsan ha ji-ita ni migi-za dai-ichi no kane ni ari [此ノ飾ノ矩ハ上棚ノ軸物ハ軸盆ニ載セテ中央ノ矩ニアリ。食籠ハ左座ノ端矩ニシテ、盆山ハ地板ニ右座第一ノ矩ニアリ], which means “with respect to this arrangement’s kane, the scroll, resting on on the upper shelf a jiku-bon, is placed on the middle kane. The jiki-rō is placed on the end-most kane on the left side; and the bon-san, on the right side of the arrangement on the ji-ita is placed on the first kane.” Thus, it appears that he seems to prefer that the bon-san be displayed on the first kane (as shown above), rather than the second (the middle one of the three found under the suspended shelves). It is impossible to reconcile this with what is shown in all of the known versions of this sketch (which show the bon-san directly beneath the place where the two suspended shelves overlap) -- though none of the sketches is accompanied by any sort of comment that confirms what is shown in the drawings to be accurate. However, it is important to note, this is also true of the sketch that accompanies Shibayama’s own commentary.

Nevertheless, Shibayama Fugen has also not offered any further explanation for this apparent discrepancy, and so it is possible that he has made a mistake when naming the kane. (In general, the classical rules for kane-wari prefer centering things within a given space -- the various ways in which an object can correspond to its kane aside -- rather than associating them with the kane on one side of the space, at least without a specific reason for needing to do so.)

——————————————–———-—————————————————

⁷Suzuri ・ ryōshi [硯・料紙].

A suzuri [硯] is an ink-stone. The kind worthy of display had usually been imported from the continent.

Ryōshi [料紙] is a pack of high-quality writing paper, gently folded in half (so that the inner pages will not be strongly creased). As with the suzuri, this paper was usually imported from the continent.

⁸Bun-dai [文臺].

A bun-dai is a low writing table -- usually with a raised rim (at least on the left and right), which prevented writing brushes from rolling onto the floor.

In addition to its use when writing, bun-dai were also used when reading* -- with (horizontal) hand-scrolls unrolled across their surface.

___________

*Since the table’s top was an appropriate distance from the eyes to make these activities visually comfortable (in the period before eye-glasses had been introduced from Europe).

⁹Bun-chin [文珍].

This appears to be a mistaken attempt* to write the homophonous bun-chin [文鎮], which is a sort of elongated paper-weight.

While the example shown above is made of bronze, various other materials (including non-metals such as ebony) were used to produce bun-chin.

Generally a pair of bun-chin were used, with one placed at either end of the piece of paper on which one was writing, to keep the surface flat and smooth.

Perhaps in the interests of clarity†, the pair of bun-chin have been replaced, in the sketch, by their name.

___________

*The second kanji could also be a hentai-gana -- though a mistake seems more likely (given the complexity of the kanji in question).

†It is also possible that bun-chin simply were not present in the original sketch, and that the name was added later to make up for what was presumed to be an omission.

However, whereas the suzuri, ryōshi, and tanzaku have been displayed on the bun-dai, writing brushes and ink are also missing, meaning that the bun-dai could not be used as it is, to do any writing, in any case. Thus the absence of the bun-chin may have been intentional (on the part of the person -- believed to be Jōō -- responsible for the original sketch): while a piece of ryōshi would have been spread out on the bun-dai before writing, tanzaku are usually stiff enough that they can even be held in the hand while writing out ones poem, meaning that bun-chin would not be needed.

¹⁰Tanzaku [タン尺]*.

A tanzaku is a “poetry card,” measuring 1-shaku 2-sun long by 2-sun wide, traditionally made from high-quality paper†. The reason for this specific size (as well as the other terms employed in this part of the post) is explained in the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 4 (16): Rikyū's Account of the Display of the Bun-dai [文臺] Beneath the Chigai-dana [違棚]‡.

___________

*The name tanzaku [タン尺] appears to be a phonetic rendering. The correct kanji-name is, of course, tanzaku [短冊].

†And sometimes even featuring a hand-painted sketch, created by a renowned artist. If the paper is thin (Chinese paper was often similar to tissue paper), then it was usually glued to a thin piece of cardboard to stiffen it (often this had already been done on the continent).

‡The URL for that post is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/190330994020/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-4-16-riky%C5%ABs-account-of-the

¹¹Kumi-yanai ・ yanai-ba no koto nari dōzen [組柳・ヤナイバノ事也 同然].

Kumi-yanai [組柳] is another name for a yanai-bako [柳箱] (which is what the statement means).

Yanai-ba no koto [ヤナイバノ事]: this seems to be a miscopying -- the kana “ko” [コ] has been lost from the word (which should be yanai-bako [ヤナイバコ = 柳箱], the other, and more usual, name for what is called a kumi-yanai [組柳] in Book Four of the Nampō Roku).

The history of this term is explained in the post that was mentioned under the previous footnote. Here, kumi-yanai / yanai-bako refers to a sort of shallow tray, elevated on a pair of slat-legs to create a sort of small table or stand (resembling an oshiki [折敷] -- though sometimes the legs were even higher), used when passing something (such as a tanzaku) back and forth to a noble guest.

With respect to Jitsuzan’s sketch, it is unclear what he has depicted resting on the yanai-bako.

This particular detail is not found in any of the other versions of the sketch.

¹²Dō-bin・te no muki-yō toko ni yoru-beshi, jun-gyaku ari [銅瓶・手ノ向ヤウ床ニヨルヘシ、順逆アリ].

“Dō-bin: the direction in which the handle faces depends on the toko -- since there is a jun and a gyaku way [to orient the handle].”

A dō-bin [銅瓶] is a sort of pitcher, made of bronze (dō [銅]). It was used to serve heated liquids.

According to Shibayama Fugen’s commentary, the orientation of a pitcher of this sort is similar to the way to orient an incense burner that is shaped like a bird (or some other animal), in that the handle of the pitcher should face in the direction where the toko-bashira is located. Thus, in the jun [逆] setting, when displayed on the chigai-dana, the handle of the dō-bin will face to the right*, and in a gyaku [逆] setting, the handle should point toward the left.

___________

*It must be remembered that the chigai-dana is located to the left of the tokonoma in a jun room, and to the right of the toko in a gyaku room. (The gyaku setting is shown above, in the comments that address the first sketch; while the jun setting is shown below, in the commentary on the second sketch.)

¹³Bajō-san [馬上盞].

This is a sakazuki [盞] with a long stem, originally made for drinking while seated on horseback. This kind of sakazuki was usually made of glazed ceramic.

——————————————–———-—————————————————

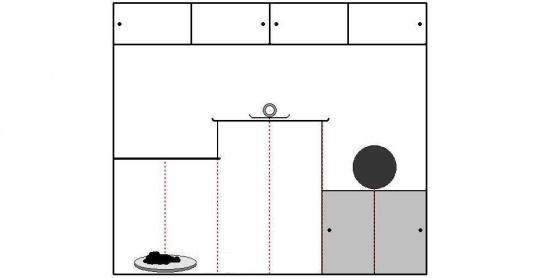

To begin with, it must be understood that the present sketch shows the arrangement in a room with the jun [順] orientation -- the toko is located on the guests’ right, and the room opens to the south. This setting is shown below.

Thus, the second sketch illustrates another example of a mitsu-dana [三ツ棚], albeit in a jun-gatte setting.

In his commentary, Shibayama Fugen notes that the yanai-bako is placed on the upper shelf of the chigai-dana, while the tray, with the dō-bin and bajō-san are placed on the left-most shelf, with the dō-bin (with the handle on the right, which would be in the direction of the toko-bashira, since the toko would be located on the right side of the recess in which the chigai-dana is found) centered on the left-most yang kane, and the bajō-san centered on the left-most yin kane (as shown)*, The bun-dai, beneath the chigai-dana, is placed so that it lies atop two kane.

___________

*Though Tanaka Senshō (whose comments on this sketch are very brief, and mostly repeat things that I have covered in the footnotes, with respect to identifying some of the objects displayed on the chigai-dana) notes that this kind of correspondence is not important, since the tray rests on a yang-kane -- making the tray (and everything it contains) yang. Since both men were quoting their sources, certain scholars affiliated with the Enkaku-ji in Fukuoka, this reveals the general state of understanding (or confusion) over this basic concept, which underpins most of the theorizing in the Nampō Roku.

1 note

·

View note

Text

FSYY 1 001 - King Zhou and the Goddess Nu Wa

The Shang Dynasty replaced the Xia Dynasty and ruled China for nearly 650 years. The Shang court produced twenty-eight kings of whom King Zhou was the last.

Before King Zhou ascended the throne, he and his father, King Di Yi, and many civil and military officials were walking in the royal garden one day, viewing the blooming peonies, when suddenly the Flying Cloud Pavilion collapsed and a beam flew towards them. Rushing forward, King Zhou or then Prince Shou, caught the beam and replaced it in a display of miraculous strength. Deeply impressed, Prime Minister Shang Rong and Supreme Mei Bo advised King Di Yi to name him Crown Prince.

When King Di Yi passed away after thirty years on the throne, Crown Prince Shou was immediately crowned king to rule the country in his father's place. King Zhou established his capital at Zhaoge, a metropolis on the Yellow River. The king appointed Grand Tutor Wen Zhong to be in charge of civil affairs and Huang Feihu, Prince for National Pacification and of Military Prowess, to supervise military affairs. In this way, the king hoped the nation would live in peace under a civil administration backed up by the military. The king placed Queen Jiang in the Central Palace; Concubine Huang in the West Palace and Concubine Yang in the Fragrant Palace. They were all virtuous and chaste in their behavior and mild and gentle in manner.

King Zhou ruled his country in peace, and was respected by the neighboring states. His people worked happily in their different professions, and his peasants were especially blessed by favorable winds and rains. There were 800 marquises in the country who offered their allegiance to four dukes, each of whom ruled over 200 of these marquises on behalf of King Zhou. There four dukes were: the East Grand Duke Jiang Huanchu, the South Grand Duke E Chongyu, the West Grand Duke Ji Chang and the North Grand Duke Chong Houhu.

In the second month of the seventh year of the reign of King Zhou, a report reached Zhaoge of a rebellion of seventy-two marquises in the North Sea district, and the grand Tutor Wen Zhong was immediately ordered to lead a strong army to suppress the rebels. One day when King Zhou was holding court, Shang Rong stepped out from the right row, knelt and said, “Your humble Prime Minister Shang Rong begs to report something urgent to Your Majesty. Tomorrow is the 15th day of the third month, the birthday of the Goddess Nu Wa, and Your Majesty should honor her and hold a ceremony at her temple.”

“What has Goddess Nu Wa done that a great king such as myself is obliged to go to her temple and worship her?” King Zhou asked.

“Goddess Nu Wa's been a great goddess since ancient time and possesses saintly virtues. When the enraged demon Gong Gong knocked his head against Buzhou Mountain, the northwest section of Heaven collapsed and the earth sunk down in the southeast. At this critical moment, Nu Wa came to the rescue and mended Heaven with multi-colored stones she obtained and refined from a mountain,” Shang Rong explained. “She's performed this great service of the people, who've built temples to honor her in gratitude. Zhaoge in fortune to have the change to worship this kind goddess. She'll ensure peace and health tot he people and prosperity to the country; she'll bring us timely wind and rain and keep us free from famine and war. She's the proper guardian angel for both the people and the nation. So I make bold to suggest that Your Majesty honor her tomorrow.”

“You're right, Prime Minister. I'll do as you advise.”

Returning to his residential palace, King Zhou ordered a notion be issued that His Majesty, together with his civil and military officials, were to make a pilgrimage to worship Goddess Nu Wa at her temple the next day.

It would have been better if he hadn't gone at all, for it was this very pilgrimage that caused the fall of the Shang Dynasty, making it impossible for the people to live in peace. It was as if the king had tossed a fishing line in to a big river and unexpectedly caught numerous disaster leading to the loss of both his throne and his life.

The king and his entourage left the palace and made their way through the south gate of the capital. Every house they passes was decorated with bright silk, and the sheets were scented for ht eking by burning incense. The king was accompanied by 3,000 cavalrymen and 800 royal guards under the command of General Huang Feihu, Prince for National Pacification and of Military Prowess and followed by all the officials of the royal court.

Reaching the Temple of Goddess Nu Wa, King Zhou left his royal carriage and went to the main hall, where he burned incense sticks, bowed low with his ministers and offered prayers. King Zhou then wandered about the hall, finding it splendidly decorated in gold and other colors. Before the statue of the goddess stood golden lads holding pennants, and the jade lasses holding S-shaped jade ornaments which symbolized peace and happiness. The jade hooks on the curtain hung obliquely, like new crescent moons suspended in the air, and hundreds of fine phoenixes embroidered on the curtain appeared to be flying towards the North Pole. Beside the altar of the goddess, made of fragrant wood, cranes and dragons were dancing in the scented smoke rising from the gold incense burners and the sparkling flames of the silvery candles.

As King Zhou was admiring the splendors of the hall, a whirlwinds suddenly blew up, rolling back the curtain and exposing the image oft he goddess to all. She was extremely beautiful, much more than flowers, more than the fairy in the moon palace, and certainly more than any woman in the world. She looked quite alive, smiling sweetly at the king and staring at him with joy in her eyes.

Her utter beauty bewitched King Zhou, setting him on fire with lust. He desired to possess her, and thought to himself in frustration, “Through I'm wealthy and powerful and have concubines and maid servants filling my palace, there‘s none as beautiful land charming as this goddess." He ordered his attendants to bring brush and ink and wrote a poem on the wall near the image of the goddess to express his admiration and deep love for her. The poem ran like this:

The scene is gay with phoenixes and dragons,

But they are only clay and golden colors.

Brows like winding hills in jade green,

Sleeves like graceful clouds, you're

As pear blossoms soaked with raindrops,

Charming as peonies enveloped in mist.

I pray that you come alive,

With sweet voice and gentle movements,

And I'll bring you along to my palace.

When he finished writing, Prime Minister Shang Rong approached him. “Nu Wa's been a proper goddess and the guardian angel for Zhaoge, I only suggested that you worship her so that she would continue to bless the people with timely rains and favorable winds and ensure that they'll continue to live in peace. Bur with this poem, you've not only shown tour lack on sincerity on this trip but have insulted her as well.” He demanded, “This isn't the way a king should behave. I pray you wash this blasphemous poem off the wall, lest you be condemned by the people for your immortality.”

“I found Goddess Nu Wa so beautiful that I wrote a poem in praise of her, and that’s all. Hold your tongue. Don’t forget that I am the king. People will be only too glad to read the poem I wrote in my own hand, for it enables them to identify the true beauty of the goddess.”

King Zhou dismissed him lightly. The other civil and military officials remained silent, no one daring to utter a word. They then returned tot he capital. The king went directly to the Dragon Virtue Court, where he met his queens and con in a happy reunion.

On her birthday, Goddess Nu Wa had left her palace and paid her respects to the three emperors, Fu Xi, Shen Nong and Xuan Yuan. She then returned to her temple, seated herself in the main hall, and received greetings from the golden lads and jade lasses.

Looking up, she saw the poem on the wall. “That wicked king!” She flew in to a rage. “He doesn't think how to protect his country with virtue and mortality. On the contrary, he shows no fear of Heaven and insults me with this dirty poem. How vile he is! The Shang Dynasty's already ruled for over 600 years and is coming to an end. I must take my revenge on him if I'm to assuage my own conscience.”

She took action at once. She mounted a phoenix and headed for Zhaoge.

King Zhou had two sons. One was Yin Jiao, who later became the “Star God Presiding over the Year," and the other Xin Hong, who later became the "God of Grain." As the two gods paid their respects to their father, two red divine beams rose from the tops of their heads and soared high in the sky, blocking the way of the goddess. Looking down through the clouds, Nu Wa at once realized realized King Zhou had still twenty-eight years to go before his downfall. She also realized that she could do nothing about it at this moment. Since that would go against the will of Heaven.

The goddess returned to her temple, highly displeased. Back in her palace, Goddess Nu Wa ordered a young maidservant to fetch a golden gourd and put it on the Cinnabar Terrace outside her court. When its stopper was removed, Nu Wa pointed at the gourd with one finger and suddenly a thick beam of brilliant white light rose from the mouth of the gourd and shot up fifty feet into the air. Hanging from the beam was a multi-colored flag called the Demon Summoning Pennant. As soon as this pennant made its appearance, glittering high up in the sky, all demons and evil sprites, no matter where they were, would gather round.

Moments later, dark winds began to bowl, eerie fogs enveloped the earth, and vicious-looking clouds gathered in the sky. All the demons in the world had arrived to receive her command Nu Wa gave orders that all the demons return home except the three sprites that dwelt in the grave of Emperor Xuan Yuan.

Who were these three sprites? The first was a thousand—year-old female fox sprite; the second was a female pheasant sprite with nine heads; and the third was a jade lute sprite.

“May you live eternally, dear goddess!” the three sprites greeted Nu Wa, kowtowing on the Cinnabar Terrace.

“Listen carefully to my secret orders. The Shang Dynasty's destined to end soon. The singing of the phoenix at Mount Qi augurs the birth of a new ruler in West Qi. This has all been determined by the will of Heaven, and no one has the power to change what must happen. You may transform yourselves into beauties, enter the palace, and distract King Zhou from state affairs. You’ll be richly rewarded forgiving the new dynasty an auspicious start and helping the old one to its downfall. However, you mustn‘t bring harm to the people.”

at the end of her order, the three spirits kowtowed, turned themselves into winds, and flew away.

Since his visit to the Temple of the Goddess Nu Wa, King Zhou had sunk into a deep depression. He ardently admired the beauty of the goddess and, yearning for her day and night, lost all desire to eat and drink. He had no passion for his queen, his concubines, or the numerous maids in his palace. They now all appeared to him like lumps of clay. He would not be bothered with state affairs.

One day, he remembered Fei Zhong and You Hun, two minion courtiers who would flatter and slander as he pleased. King Zhou sent for Fei Zhong, and the latter appeared in no time.

“I went to worship Goddess Nu Wa recently,” King Zhou began. “She’s so beautiful I believe she has no rival in the world, and none of my concubines is to be compared with her. I’m head over heels in love, and feel very sad as I cannot get her. Have you any ideas with which to comfort me?”

“Your Majesty! With all your honor and dignity, you're the most powerful and the richest man in the world. You possess all the wealth within the four seas, and are virtuous as the sage emperors Yao and Shun. You may have anything you wish for, and you should have no difficulty in satisfying your desires. You can issue an order tomorrow demanding 100 beauties from the grand dukes. You’ll then have no trouble finding one as beautiful as Goddess Nu Wa,” Fei Zhong suggested. King Zhou was delighted. He said, “Your suggestion appeals to me greatly. I’ll issue the order tomorrow. You may return home for the time being. ”He then left the throne hall and returned to his royal chambers to rest.

If you wish to know what happened thereafter, please read the following chapter.

#fsyy vol1#fengshen yanyi#rip the ocr of my phone app sucks i had to format and spell check this entire thing lmao#unsure of when i'll be done with the second chapter#the last sentence of please read the following chapter is literally in the book lol i dont know why

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Yun-Fei Ji James Cohan Gallery

Amid lush landscapes, bundles of household goods and furniture await removal in Yun-Fei Ji’s watercolor paintings of rural China. As the government relocates huge numbers of country-dwellers to urban areas, the artist zeros in on individuals and their belongings in the process of being uprooted. (On view at James Cohan Gallery’s Lower East Side location through June 16th). Yun-Fei Ji, detail of The Family Belongings, watercolor and ink on Yuan paper mounted on silk, 15 ½ x 26 ¼ (unframed), 2011.

1 note

·

View note

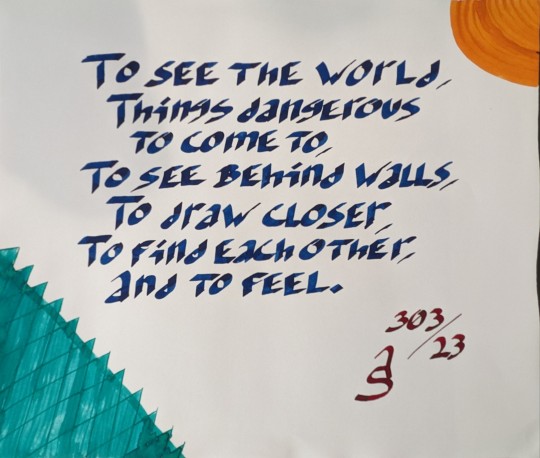

Text

redid one of the first projects i felt proud of last night during @theshitpostcalligrapher stream.

i'm still happy enough with the old one but it's nice to look at both and see how much more consistent i am about letter heights, baselines not shifting, and general "smoothness" of my pen strokes. wish i had put a date on the old one though so i could tell how long ago it was done!

the new one is above, the old one below.

#calligraphy#old work#redo#practice#progress#the secret life of walter mitty#the movie. not the book#i should probably learn how to compose for watercolor since i kinda treat embellishments like they are anyways#tsavorite ink#crab nebula ink#yuan ji ink#romania red ink#so many inks...

83 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you think of Cao Hong? Was he really as bold and impulsive as he's depicted in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms? And is it true that Sun Ce was against witchcraft (in whatever form it was believed to exist)?

Cao Hong was great, aside from his inability to control his subordinates. He was bold, but I wouldn’t say impulsive. He was brave but not reckless. He was never afraid to be on the front lines, and at one point personally saved Cao Cao’s life at great risk to his own. He had an impressive record, winning a number of battles by himself and playing a crucial role in most of the ones that Cao Cao personally commanded. I’d say he was equal to Xiahou Yuan. The only problem with Cao Hong was that he was a poor commander off of the battlefield. His subordinates were unruly and unlawful, and a number of them had to be executed for their crimes. While Cao Hong wasn’t part of their criminal activity, his failure to control them is certainly a flaw.

The Jiangbiao Zhuan contains the story of Sun Ce and the mystic Gan Ji. In it, Sun Ce does express a disdain for mysticism - mostly because it accomplishes nothing.

A short time ago, Zhang Jin of Nanyang became Inspector of Jiao province. He set aside the precepts of the wise men of the past and he rejected the law codes of the house of Han. He wore a red cloth about his head, he had drums and flutes played, he burnt incense and he read the false books of the Taoists. This, he said, would help in his administration. In the end, however, he was killed by the local barbarians. All this sort of thing is completely useless, and yet you people have failed to recognise the fact. That fellow Gan Ji is already numbered among the dead; don't waste any more paper or ink upon him.

He didn’t kill Gan Ji out of any particular hatred of mysticism, though. Rather, it was because he worried that Gan Ji had too much influence over his army and could become a rival for power if he wasn’t dealt with.

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

Tugh Temuiir's appearance in the newly fashioned imperial costume took place at the Kuizhangge, a new government organ that functioned somewhat like a private library. Several scholarly studies of the Kuizhangge provide us with a rich picture of its history and organization; research by Chiang I-han, Fu Shen, Marsha Weidner [Haufler], and Kanda Kiichiro has resulted in the partial reconstruction of the art collection stored there.6 These researchers' inventories consist of both surviving artworks bearing Tugh Temiir's seals and/or inscriptions by Kuizhangge personnel, as well as paintings associated with the Kuizhangge only in textual sources. Poetic inscriptions for particular paintings in his collection appear in Yuan collectanea (wenji) under titles that explicitly state that they were written at Tugh Temiir's command (yingzhi). These surviving poems contain rich iconographic readings of the paintings and point to the essential functions of collecting and "enjoying" art at Tugh Temiur's court; however, no extended analysis of the paintings or inscriptions has been published. This article aims to fill that gap.

Ankeney Weitz, Art and Politics at the Mongol Court of China: Tugh Temür's Collection of Chinese Paintings, Artibus Asiae, Vol. 64, No. 2 (2004), pp. 243-280.

Art historians have generally taken a somewhat narrow view of the Kuizhangge, seeing it simply as a center for the promotion of Chinese art and culture at the Mongol court. In recent literature, the Kuizhangge has been depicted as a latter-day equivalent of Song Emperor Huizong's (I082-II35) famous art studio and library, the Xuanhedian.7 Indeed, allusions to Emperor Huizong and his art pepper the documentary history of the Kuizhangge, and the fourteenth-century scholars intentionally invoked Huizong as an imperial model in order to position the viewing of paintings as a leisure activity, a diversion from the more serious business of collating thejingshi dadian, an 880-volume tome documenting the administrative acts of the previous Yuan emperors.8

Nonetheless, these same scholars functioned in an environment of political instability. Mid-Yuan court politics were plagued with factional tensions between groups of bureaucrats (of all ethnicities - Chinese, Mongolian, and various Central Asian groups), "usually in alliance with groups of imperial [Mongol] princes. "9 During Tugh Temiir's reign, two senior officials, the Qipchaq El Temtir (d. I333) and his ally Bayan of the Merkid tribe (d. 1340), deftly manipulated the frictions between the various groups, thereby weakening the factions' power and increasing their own dominance. By arrogating most of the power in their own hands, the two turned Tugh Temiir into a figurehead, an imperial symbol whose integrity needed to be manifest to keep the empire intact.10 The loyal officials of the Kuizhangge were called upon to create an image of imperial legitimacy, a service they performed through cultural endeavors, including the appreciation of paintings.

[...]

The coup d'etat and civil war that brought Tugh Temtir to the throne in 1328 had a direct bearing on the construction and development of his imperialp ersona.1T2 he seeds of the conflict originated in the 1307 succession struggle between Khubilai Khan's (Shizu, r. I260-1I294) two great-grandsons, Khaishan (Wuzong, r. I307-I31I, Tugh Temiir's father) and Ayurbarwada (Renzong, r. 1311-1320, his uncle). The ultimate selection of Khaishan, "a military hero from the steppes ... [who] behaved like a nomadic chieftain,"13ca me with the proviso that his younger brother,A yurbarwada,b e designated heir apparent. Thus, upon the death of Khaishani n 1311A, yurbarwadap eaceablya scendedt he throne. The agreement of I307, however, had not clearly specified the line of succession after Ayurbarwada, and soon several contenders and their supporters began maneuvering for position.

For the next twelve years Ayurbarwada and his descendents ruled the country, and they successfully removed Khaishan's sons - Khoshila (Mingzong, r. I329) and his younger brother Tugh Temtir - from the political scene by banishing them to distant corners of the empire. In 1316, Khoshila was exiled to the southwestern hinterlands in Yunnan Province; however, he managed to escape to the northern steppe where he lived as a political refugee at the court of the Chaghatai Khanate. Five years later, the reigning emperor sent Tugh Temiir to Hainan, a subtropical island off the southern coast of China. From these remote outposts, they witnessed the murder of Ayurbarwada's son (Shidebala, Yingzong, r. 132I-I323) by a disgruntled group of Central Asian aristocrats and Mongol princes. His successor, Yesun Temiir (r. 1323-1328) attempted to appease his imperial relatives by bestowing gifts and land. He also recalled Tugh Temtir from Hainan.

[...]

In 1328, Yesun Temiir died, and El Temiir staged the coup that successfully installed Tugh Temuir on the throne. This audacious move touched off a short, but bitter, civil war that effectively consolidated E1Tl emtir's power.15A s E1Tl emuir'sp uppet, Tugh Temiir "controlled"t he seals of the imperial office; however, his older brother, Khoshila, still held a competing claim to the throne. Seeking to avoid a direct confrontation with Khoshila, Tugh Temiir abdicated in his brother's favor in the second month of I329, an act that later served as an example of Tugh Temiir's Confucian piety.

Six months later, in the eighth month of I329, the two long-estranged brothers met in Inner Mongolia and held a great banquet to celebrate the occasion. Four days later, Khoshila was dead. The official annals cite unnatural events as the cause of his demise, and most historians have presumed that El Temiir poisoned him. For his part, Tugh Temiir wasted no time in ascending the throne once more, and his sponsors (El Temiir and Bayan) never bothered to call the traditional assembly of Mongol princes (khuriltai) to decide the rightful succession.16 El Temiir's military successes had made this fundamental Mongolian institution obsolete.

Tugh Temiir's climb to the throne over his brother's dead body and without princely sanction was untenable in both the Chinese Confucian tradition of statecraft and in the Mongolian military-political order.17 Power struggles plagued his reign; his supporters uncovered eight plots on his life led by rival factions in the imperial family. Langlois contends that Tugh Temiir's urgent need of the "veneer of legitimacy" was answered by El Temiir's creation of an ambitious campaign to endow Tugh Temuir with a new persona: enlightened Confucian sage ruler.18T his choice was almost inevitable, since not only had El Temiir thrown in his lot with a large "Confucian" bureaucratic faction in order to win its support for the coup, but Tugh Temiir's own residence in southern China had instilled in him Chinese cultural habits (later encouraged by his wife and mother-in-law) and Confucian ideals of statecraft. The use of Confucianv alues by the "restoration"f action both elicited the continued support of the bureaucracya nd provided Tugh Temiir's court with useful symbolic tools. For instance, in a series of memorials his officials drew attention to his earlier abdication in Khoshila's favor as proof of his familial loyalty and brotherly humility.19 In studying these texts, Langlois argues that the invocation of Confucian vocabulary and institutions at Tugh Temiir's court was largely propaganda designed to legitimate the emperor's authority.20

[...]

Yu Ji, a major figure in the Kuizhangge, elaborated on the emperor's edict, announcing that the Kuizhangge scholars should:

provide explanations about the learnsa nd the ways of rkeiansgosn, s the for prosperity and failure, for attainment and loss, so that [these things] could serve as admonishments [for the emperor] .27 [Text B ]

The Kuizhangge scholars churned out reams of Confucian materials - edicts written on behalf of the emperor, memorials, translations, records, and poems - designed in large part to convince the bureaucracy of the legitimacy of the imperial succession.28

To disseminate the carefully constructed imperial image, the Kuizhangge hired stone carvers to engrave the most important documents on steles; for instance, officials snatched up ink rubbings of Yu Ji's laudatory "Record of the Kuizhangge, " said to be written out by Tugh Temiir himself.29 The recipients of the officially printed Kuizhangge "propaganda" consisted of members of the court, as well as the greater bureaucracy. In a number of public documents circulating during and after Tugh Temiir's reign, Chinese officials represented the emperor's cultural leanings as a sign of his sage administration. 30U nofficial rumorsa bout the emperor'sa ctivities in the Kuizhangge also spreadt he desired representation of Tugh Temiir as a morally righteous ruler.31

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Swiss luxury watch brand Constance launched four new heartbeat [email protected]

Swiss luxury watch brand Constance launched four new heartbeat automatic watch (Ladies Automatic Heart Beat), the disk 12 o’clock position are equipped with brand logo circular hollow window, shining fine, to the wearer to explore the watch Mechanical mystery of the sincere offer.

Pearl mother of pearl dial was Cartier Replica Love Ring silver and white tone, engraved complex Ji Lou decoration, equipped with eight diamond studs and Arabic numerals when the standard. Through the sapphire crystal table, you can see the FC-310 automatic winding mechanical movement of the precise operation. The movement of the number of stones 26, vibration frequency 28,800 times / hour (4 Hz), can provide 38 hours power storage. Case diameter 34 mm, thickness 9.9 mm, equipped with arc sapphire crystal and 2-O-Rings crown, waterproof depth of up to 60 meters. Time, minutes, seconds can be adjusted through the crown.

Since 2004, Cartier Juste un Clou Ring Copy Constance has been dedicated to supporting charity. Constance promised to donate $ 50 to the heart, children and women’s charity every sale of a women’s automatic watch. Constance is the actual action interpretation of “Live your passion” (live your passion) brand slogan.

Roger Doubi first launch round table knight watch is in 2013, when the launch of a sensation, the bezel is one of the most talked about the topic, inspired by the legend of Arthur’s legend, the biggest feature of the watch is 12 Hand knight sword round table knight out of a perfect round shape, with twelve knights to replace the traditional time scale display. In the new watch, the watch shows a stunning miniature process, today’s watch home for everyone to bring Roger Doppe Excalibur senior watch series automatic watch, watch the official model: RDDBEX0495.

King Arthur and the story of the round table knight believe that we know more or less, the legendary, the first unified Fake Amulette de Cartier Ring British King Arthur’s arm, the most powerful and most loyal knight, and King Arthur has a total of a banquet party honor. These King Arthur’s closest subordinates are round table knights. Arthur’s father, King Uther Pendragon, had a large round table for the knights of his knight, and Arthur got the table and the warrior from his father-in-law at the time of marriage. At that time the round table knight became Arthur King under the command of the knight hero group. They come from different countries, and even have different beliefs. The meaning of the round table is equal and the world. All the knights of the round table are equal to each other and are partners.

18K white gold case material to create

In 2013, Roger Doubi on the exit of 18 rose gold round table Knight watch, the Roger Doubi with bronze round table knight and ink jade disk interpretation of the world for the legend of the legend, the use of 18K white gold case material Build.

Watch more fine attention to art

In 2015 Roger Cheap Trinity de Cartier Ring Dube has launched a round table Knight watch, can also be an indirect description of the release in 2013 18K rose gold version of the round table Knight watch sales are very good, so in 2015 and launched a new round table Knight wrist table. More fine and more attention to art.

Watch used for the design of Mu Yu dial

The new round table knight watch used for the design of the Muyu dial, to reflect the round table of ink to the decision from the desktop itself in the carving level of complexity, but the result is quite perfect success. Mo Yu has always been regarded as a body gem, a symbol of strength, wisdom and self-control ability. When people are cautious in the face of financial or social, that the ink can prevent those who are prone to irritability and violence.

The first use of bronze material for micro-carving works