#zombie tramp

Text

Zombie Tramp

408 notes

·

View notes

Text

So many monster fuckers here but none of yall post about zombie tramp

It’s a comic series featuring a zombie hooker, there’s another comic involving her where she’s a hero with other skimpy characters that’s called Danger dolls and I love both so much

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

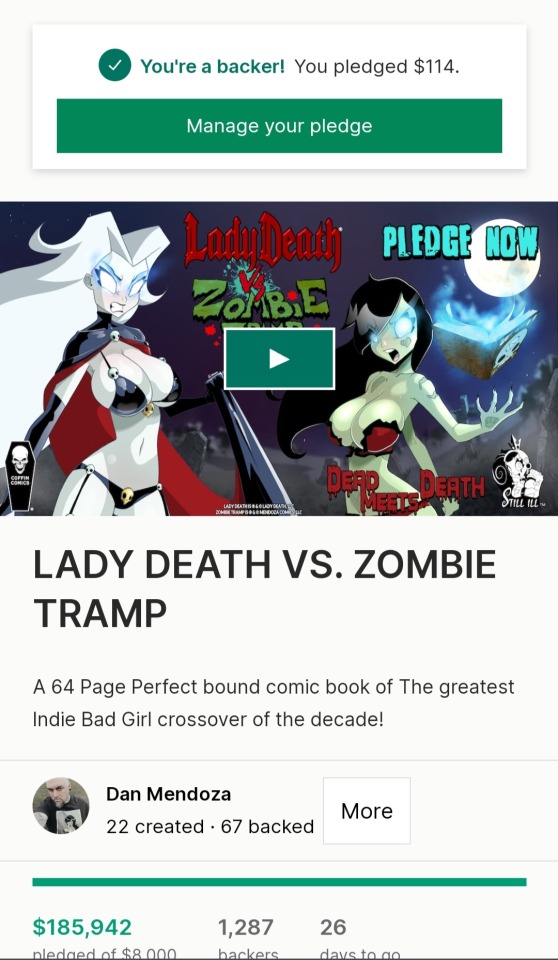

Lady Death and Zombie Tramp by Bill McKay

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

search

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

deliverer of dismay; WOMAN

#aesthetic#gothic#dark acadamia aesthetic#dark acamedia#woman#goth woman#zombie tramp#dark aesthetic#seductress#alternative#dark woman#angel of death#dark fantasy#fantasy woman#comics#female artwork#female art#evil woman#I just <3 woman#vampire aesthetic#vampire kin#vampire#comic art#bats#badass women#skulls#mortal kombat#femme fatale

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

。.:*☆ LIKE + REBLOG IF USED # . * 🫁

#living dead girl#zombie#zombie girl#messy layout#messy layouts#twitter packs#icons#headers#banners#dividers#lollipop chainsaw#zombie tramp#zombie land saga

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

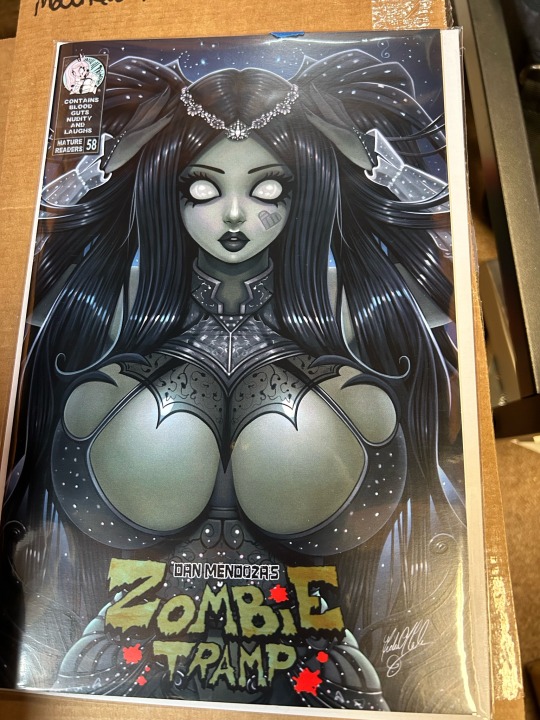

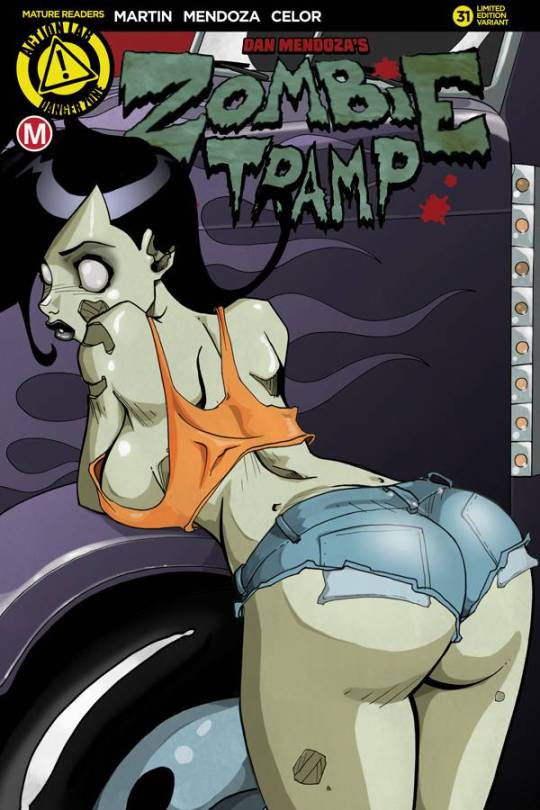

Zombie Tramp Varient

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝔧𝔞𝔫𝔢𝔶 𝔟𝔢𝔩𝔩𝔢 𝔦𝔠𝔬𝔫𝔰 🔪

𝔩𝔦𝔨𝔢 𝔬𝔯 𝔯𝔟 𝔦𝔣 𝔶𝔬𝔲 𝔲𝔰𝔢/𝔰𝔞𝔳𝔢

#zombie tramp#zombie tramp icons#janey belle#janey belle icons#dan mendoza#bill mckay#horror#2000s#2010s#alt#gothic#grunge#emo#goth#rockabilly#horror punk#horror icons

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#insane clown posse#violent j#shaggy 2 dope#icp#xpw#zombie tramp#action lab comics#danger zone#dan mendoza#x-men#marvel comics#vampblade#witchblade#top cow comics#chaos comics

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zombie Tramp #58 Kickstarter goodies

#zombietramp#zombie tramp#zombie tramp 58#zombie tramp Kickstarter#comic#indie comics#Kickstarter comics#kickstarter goodies

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

ZOMBIE TRAMP ONGOING #42

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lady Death and Zombie Tramp by Bill McKay

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

I couldn't help myself

0 notes

Text

Cartoon depictions of the homeless increasingly reflect the hostility of today’s political leaders toward people on the streets. We’ve gone from images of charming hobos with bindles to zombies taking over cities.

If you consume any news at all, you’ve probably noticed that the United States is pathologically cruel to its homeless citizens. This May, the brutal killing of Jordan Neely—who was strangled to death, at the age of 30, simply because he was unhoused and shouting on the Manhattan subway—captured the national spotlight, but it was just one of many such cases of unprovoked violence. In January, two cops reportedly kidnapped a homeless man in Hialeah, Florida, drove him to an “isolated and dark location,” and beat him unconscious. That same month, art dealer Shannon Collier Gwin faced battery charges after he sprayed a homeless woman with a hose outside his San Francisco gallery, barking “Move! Move!” at her. (Predictably, Gwin got a lenient plea deal of just 35 hours of community service.) Elsewhere in the city, homeless San Franciscans have been attacked with chemical bear spray on at least eight occasions. Other assaults have been more impersonal but no less vicious. On July 14, the city of Houston abruptly closed its only public cooling center in the downtown area, potentially condemning anyone without shelter to suffer heatstroke in 90-degree weather. Among the property-owning class, the phenomenon of hostile architecture—sidewalks with spikes that stab anyone who tries to sleep, benches with iron bars, and the like—has become de rigueur. The widespread callousness and lack of compassion are both infuriating and hard to comprehend. How on Earth, we might ask, did things get this bad? [...]

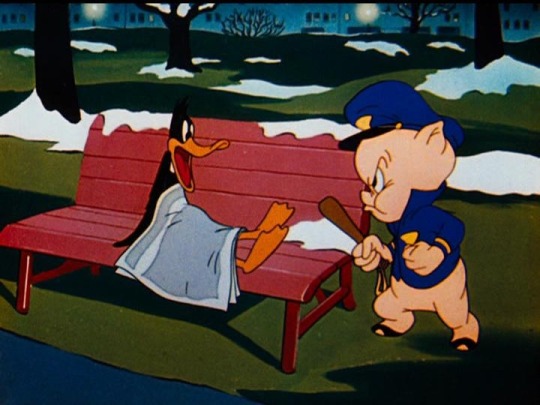

Looking back at older cartoons, one of the things that stands out immediately is the absence of negative attitudes toward the homeless. In fact, during the Golden Age of animation, creators seemed to have had a real affinity for the poor and unhoused, often placing their most iconic characters in that role. There’s a wonderful 1948 Warner Bros. short called “Riff Raffy Daffy,” in which Daffy Duck is looking for a place to sleep—first on a park bench, then a trash can, and finally a furniture display in a shop window—and has to dodge the harassment of the police, as represented by Porky Pig in a little blue uniform. (Literally, the cop is a pig!) Or, in the 1950 cartoon “Homeless Hare,” Bugs Bunny’s rabbit hole is destroyed by a new construction project, leading him to unleash his usual slapstick mayhem against the developers until they put it back. In these cartoons, homelessness is something inflicted on people by outside forces—gentrification and the real estate business, in Bugs’ case—and something which can be successfully resisted.

Even Disney cast a homeless dog as a romantic lead in 1955’s Lady and the Tramp, contrasting Lady’s sheltered naivety with Tramp’s superior knowledge of the world. The title invokes the memory of Charlie Chaplin’s “Tramp” films, which similarly brought dignity and humanity to the role of a homeless man. (Bugs Bunny, too, takes inspiration from Chaplin, and multiple Warner animators have drawn him as the Tramp.) In 1961, Hanna-Barbera’s profoundly underrated Top Cat followed the adventures of a gang of wisecracking Manhattan alley cats, who, like Daffy, are always outwitting a meddling policeman. At worst, classic cartoons may trivialize the suffering and danger associated with homelessness—there’s a certain recurring image of the carefree hobo carrying a bindle, which paints the whole subject in a romanticized light—but the homeless themselves are rarely disparaged or made the butt of the joke. Quite the opposite.

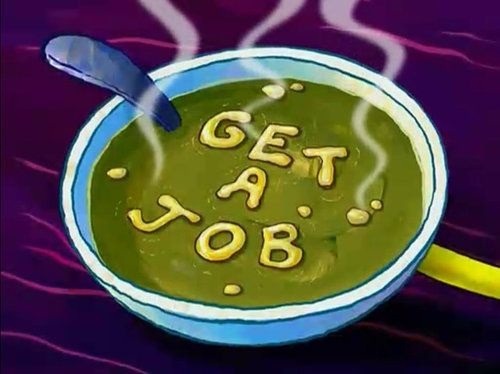

It took a few years, but cartoons caught up to the Reaganite turn. In episodes from the ’90s and early 2000s, there’s a palpable shift in the way homeless characters appear compared to earlier decades. The perspective is different: we’re now seeing them through the eyes of comfortably housed characters, rather than their own. Often they don’t even get proper names. [...] This trajectory leads us, perhaps inevitably, to SpongeBob SquarePants. [..] Squidward gets accused of stealing a dime by his comically greedy boss, Mr. Krabs, and quits his job in a fit of outrage. We then flash forward to see Squidward, now bedraggled and unshaven, living in a cardboard box on the street and begging for change. [...] Mercifully, the ever-cheerful SpongeBob gives Squidward a place to stay—but the moment he’s safely off the street, Squidward turns from a sympathetic victim of circumstance into a lazy, entitled freeloader, straight out of a Reagan speech. He makes no effort to find work and loafs around SpongeBob’s house for ages. [...] Eventually, an exasperated SpongeBob writes “GET A JOB” in his alphabet soup, before shoving him (bed and all) back to work at the Krusty Krab. [...]

Worst of all, though, the episode suggests that homelessness can be solved on an individual basis if the people in question simply stop being lazy and “GET A JOB.” This is the biggest myth of all. In 2021, a statistical analysis by the University of Chicago found that 53 percent of people in homeless shelters, and 40.4 percent of unsheltered people, do have jobs. The problem is that their wages are too low, and rents are too high. According to statistics from the same year, it’s impossible for someone working a full-time, minimum-wage job to afford a single-bedroom apartment in 93 percent of U.S. counties, and there are no states in which someone can rent a two-bedroom space on the current federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour. In other words, homelessness has little or nothing to do with personal responsibility, or lack thereof. It’s a consequence of large-scale economic decisions made by landlords and bosses. [...]

— Alex Skopic

839 notes

·

View notes