Text

The Long Shadow review – a shattering serial killer drama that breaks all the rules

A mighty cast including Katherine Kelly and Toby Jones tells the stories of the women murdered by Peter Sutcliffe. Finally, the focus is on the victims

By the end of the first two of the seven episodes of ITV’s new drama about the Yorkshire Ripper made available for review, Peter Sutcliffe has barely been glimpsed. This alone marks it out from the herd of serial killer dramas, let alone documentaries, of which every streaming platform has a full quota. The general rule is that, however much the makers stress that their creation will centre the victims instead of the perpetrator of the crimes, they somehow all end up in thrall to precisely that person. Even when there really are intentions otherwise, the perpetrator inevitably becomes the dramatic focus and the narrative engine.

The Long Shadow – so far, at least, which is already further than most – shatters the general rule. Written by George Kay (whose last outing was the very different, very fun Hijack starring Idris Elba) and directed by Lewis Arnold (Sherwood, Time, Des – the Dennis Nilsen drama starring David Tennant), it is based on Michael Bilton’s book Wicked Beyond Belief, plus additional research and with the consultation and blessing of the families.

More than any rendering of a notorious case that I can remember, the attention is on the women. Specifically, the living women. And, when they are gone, the people they leave behind. After Wilma McCann’s (Gemma Laurie) murder, and the investigation that will take five years to apprehend Sutcliffe despite the police interviewing him nine times, the focus moves to Emily Jackson (Katherine Kelly). The opening episodes concentrate on presenting her situation to us in the round, as dire financial straits drive the embattled wife and mother to sell sex and put her fatally in Sutcliffe’s sights.

The Long Shadow deals in details. It is not simply poverty that leads the Jacksons to extreme solutions, but the social pressures and the desire not to lose face in front of the neighbours are all carefully and accurately drawn. So too are the subtle prejudices that nudge Irene Richardson (Molly Vevers) out of the chance of a job as a nanny that might have saved her from becoming Sutcliffe’s third murder victim.

After her, there is Marcella Claxton (Jasmine Lee-Jones), who survives a hammer attack by the man who will soon be tagged “the Yorkshire Ripper” by the media, though the moniker – hated by the families – is barely used in The Long Shadow. She miscarries at four months as a result of the attack. Back home from hospital, we see her gently touching her terrible head wound, trying to see it in the mirror and gauge its extent, with the empty cot in the background – a moving evocation of the literal and metaphorical extent of trauma; how much we want to find its boundaries and how impossible it can be to do so.

The police investigation weaves round the women’s stories, and although it hits many familiar beats, the quality of the writing and presence of the likes of Toby Jones, David Morrissey and Lee Ingleby as the various detectives in charge over the years means that this too is better done than usual. We have come to expect virulent misogyny and racism to be on show in dramas set in earlier decades and involving the police – or any other unwieldy, male-dominated institution – but The Long Shadow succeeds in embedding it more quietly but firmly. It is a way of life, a way of thinking rather than a succession of big instances (though it still has its moments, such as when the detectives’ hospital interview with Claxton turns into an interrogation, as their engineered politeness in front of a black woman begins to fail).

This all means that we better understand how the investigation went so wrong so many times, with even “the good guys” believing that the deaths of sex workers (and assuming that any woman near a known streetwalking area was one) were not worth much effort, or that any woman drunk and out after dark got what was coming to her. And it means we can better see its descendant attitudes now and how insidiously they still work against women. Big, sexist/racist set pieces or a clear divide between bad cops and the angelic few who have managed to transcend their eras allow us to believe that things are different now. The Long Shadow’s subtlety and care denies us such mistaken comfort.

The Long Shadow is on ITV and ITVX in the UK, and on Stan in Australia

==

I hope one day they do the same with the Whitechapel Victims... RIP.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Because tumblr is very picky with which content is appropiate and which not, and because it flags posts for no reason and even if you appeal they have the last input, we have created a blog on blogspot for our Tumblr blog Victorian Whitechapel.

We are not going to delete the tumblr blog but we have the one in blogspot as a back-up, in case any of the posts on tumblr are flagged just because.

We will be updating it little by little, on the important dates (anniversaries, etc) so feel free to check whenever you want, subscribe, etc.

I hope you enjoy it!

#victorian era#victims#victorian#victorian whitechapel#jack the ripper#1880s#our sites#links#blogspot#tumblr#19th century#follow#like#join#share#link#my blog

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elizabeth “Lizzie” Jackson

Elizabeth Jackson (aka Lizzie)

Birth date: March 18, 1865 Killed and found (age): Ca. June 3rd 1889, June 5th 1889 (24)

Complexion: Fair Eyes colour: ? Hair colour: Sandy, light red or auburn Height: 5’5” (165 cm) Occupation: domestic servant

Clothes at the time of murder/discovery: Grey Ulster’s coat, black dress button, brown linsey dress, burgundy skirt with red selvedge, blue-and-white waistband/drawers bearing the name of L. E. Fisher, ?

Resting place: ?

***

Early life

Elizabeth Jackson, also known as Lizzie, was born on 18 March 1865 in the neighbourhood of Chenie-place, Pimlico (City of Westminster). She was the daughter of John Jackson, a stonemason who was born in County Tipperary, Ireland, and his wife Catherine, who was also born in Ireland but hailed from County Cork. She was the youngest of three daughters, the others were Annie and May, and she also had a brother, James. When she was about twelve she had an accident with a vase leaving her a scar in her left forearm.

In 1881, when she was sixteen, she had gone out to work as a domestic servant in the neighbourhood of Chelsea. She had been described as “of excellent character” until, in November 1888, something happened which occasioned her leaving both her job and her home. Thereafter, she had been living in various common lodging houses in the vicinity of Chelsea. Her last known address was 14 Turk’s Row, which was near Chelsea Barracks. It was there when Lizzie and her sister Anne had a nasty row, as the latter accused the former of picking up men for immoral purposes.

Later months

In November 1888 she was well known to the local police, and she took up with a casually met Cambridgeshire man, a thirty-seven-year-old millstone grinder named John Fairclough (born March 1853), with whom she moved to Ipswich in January 1889. He said they met in a public house at the corner of Turk’s Row. She had told him she had been living with a man named Charlie but the relationship was over. She bought a pair of drawers bearing the name “L.E. Fisher” at a lodging-house at Ipswich, they had belonged originally to a domestic servant at Kirkley, near Lowestoft, and had been sold as old rags by her mother while staying near her daughter in November 1888. Elizabeth and John were in Colchester on March 30th 1889 and, unable to find work there, walked all the way back to London where they settled into lodgings in Manilla Street, Millwall, taking a room at four Schillings a week, with a Mrs. Kate Pane, who would afterwards testify that Fairclough was violent in his treatment of Elizabeth, knocking her about, irrespective of her being five months pregnant.

The pair parted on 28th April, Fairclough going off to Croydon in search of a job. Mary Minter, a family friend of Elizabeth’s, gave her an Ulster’s coat not long before she disappeared. On May 31st Catherine Jackson saw his daughter only one day or two before she was murdered in Queen’s Road, Chelsea, and the two spent the time together. Lizzie was a 24 year-old homeless prostitute about eight months pregnant, and living in London’s Soho Square at the time of her murder in early June 1889.

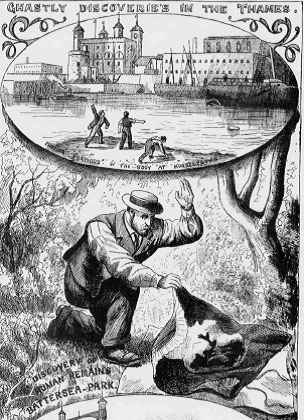

Discovery

On Tuesday 4th June 1889 in the morning, one package containing portions of a woman’s body was found by two boys, as witnessed by waterside labourer John Regan at George’s Stairs, Horselydown (just below London Bridge). At 10:00am, standing along the bank of the Thames, Regan noticed a couple of boys “throwing stones at an object in the water”. When one of the boys pulled the package out of the water, and realizing the contents of the package were that of human remains, contacted the Thames River police division. These remains were taken to Wapping police station by Alfred Freshwater of the Thames Police. Several experienced Scotland Yard detectives and Dr. Thomas Bond, the chief surgeon to the Metropolitan police, proceeded to Wapping (a district in East London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets) to commence investigations. Among the first detectives and police at the scene was Melville Macnaghten, the newly appointed Assistant Chief Constable of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID).

The remains were the lower part of a female body; and she had evidently not been dead long as Dr. Bond noticed a slight ooze of blood from the ragged edges of the cut parts of flesh. Dr Bond was instantly of the opinion that the body part was that of a young woman and that an attempt had been made to carry out an illegal operation, which had been successful. None of the press reports described exactly what was found within this parcel to draw these conclusions from, but according to the medical jurisprudence book ’A system of legal medicine’, which contains details from some of Dr. Bond’s cases, there were flaps of abdominal skin and the uterus of the victim, complete with cord and placenta, “… The skin was fair, and the mons veneris was covered with light sandy hair…”

Almost simultaneous to the discovery by the two boys, was the finding of another parcel by fifteen-year-old Isaac Brett, of 7 Lawrence Street in Chelsea, who earned his living as a wood cutter. When taking a walk near the Albert Bridge, Battersea (South West London, within the London Borough of Wandsworth, about 5 miles from the spot of the first discovery), Brett decided to take a bath. Upon submerging he noticed a strange object being nudged by the tide against the muddy foreshore and tied with a bootlace. He took it ashore but didn’t open it. Upon the advice of a passing stranger, he took it straight to the Battersea Police Station, where sergeant William Briggs of V division opened it. The assistant divisional surgeon for Battersea, Dr. Felix Charles Kempster, was called in. He declared it to be a portion of a human thigh from hip to knee; his opinion was that the limb had not been in the water above 24 hours. The white cloth was the right leg of a pair of drawers, on the waistband (an item of ladies underclothing) of which had the name L.E. Fisher written in black ink along it. Fastened to another portion of the material was a piece of tweed seemingly torn from the right breast area of a lady’s long Ulster coat.

The local police immediately alerted Scotland Yard and Inspector John Bennett Tonbridge or Tunbridge of the criminal investigation department alerted Dr. Bond, who concluded that the two body parts corresponded and there were no doubts that they belonged to the same body, further proof that backed this up came from the fact the parcel found at Horselydown was wrapped in a portion of underwear identical to the portion found with the thigh section at the Albert bridge and also contained another portion of the bottom left hand side of a woman’s Ulster coat. The whole parcel had been tied up with mohair boot laces and was slightly stained with blood. Further examinations of the thigh, by Dr. Kempster and Mr. Athelstan Braxton Hicks found it to be the left one, and most likely that of a young woman within the 20 to 30 age range. Bruises made by finger marks were also found upon the thigh, and these were concluded to have been made before death.

On Wednesday 5th June 1889, the coroner of East Middlesex Wynne Edwin Baxter, who had presided over the inquests of Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman and Elizabeth Stride, opened an inquest at the Vestry hall, Wapping, into the remains found at Horselydown. He expressed doubts as to whether it was a proper case for an inquiry as it was difficult to draw the line as to what part of a body was sufficient enough to warrant an inquest. However, he had decided that an inquiry should be held and he summoned a jury. John Regan and Alfred Freshwater gave evidence at the inquest and repeated their stories. The inquest was then adjourned until the 3rd of July.

On Thursday 6th June, in the afternoon, Joseph Davis, a gardener at Battersea Park, was at work near some greenery rhododendron shrubbery when he noticed a parcel laying on the ground in an area that was closed to the public. The shrubbery was situated about 200 yards from the shore of the Thames and was a place not frequented usually by the public or employed staff at the park. On nearing the bundle, that was rides with white Venetian blind cord, he noticed an unpleasant smell emanating from it. Upon open it, Davis threw the thing in shock, horrified to recognise parcelled therein bits and pieces from a human body wrapped in a burgundy-coloured skirt. Off he shot in a desperate dash in search of one of the patrolling park policemen. He found police constable Walter Augier of V division, and conveyed the parcel to Battersea police station by means of a garden basket. Dr Kempster, whose surgery was only a few yards from the police station, was alerted to the find by Sergeants Viney and Briggs, Viney being in charge of local inquires into the case. Telegrams were despatched to police headquarters describing the remains found as thus: the upper part of a woman’s trunk, probably a portion of other human remains found in the Thames. The chest cavity was empty but among the remains were the spleen, both kidneys, a portion of the intestines and a portion of the stomach. There was also a portion of midriff and both breasts present. The chest had been cut through the centre, thought to have possibly been done by a saw. Kempster was of the opinion that due to the state of decomposure, they were probably looking at another portion of the same remains previously found in the Thames, and that the murder might have taken place as early as June 2nd.

That same Thursday afternoon, around 4pm, Charles Marlow, a man working on a barge at Covington’s Wharf adjacent to the London, Brighton and South Coast railway at Battersea and coincidentally, almost immediately opposite the spot where an arm belonging to the ’Whitehall torso’ was found in the previous year, noticed a parcel floating up the river, he fished the bundle, wrapped in portions of a woman’s dark coloured skirt and tied with ordinary string, out with a broom. Once again a passing Thames police boat was flagged down and Inspector William Law of the Thames division took possession of it at Waterloo Pier, and was conveyed to Battersea police station to await the scrutiny of Dr. Kempster. This latest find was the upper part of a woman’s trunk, the arms had been taken off cleanly at the shoulder joints and the head separated from the body close to the shoulders. The chest had been cut down the centre in a similar fashion to the other portion of the trunk. A portion of the windpipe remained within the trunk but the lungs were missing. An earlier supposition that the victim had light red or auburn hair was substantiated on the finding on this portion of the body.

The doctors and police were now gradually building up a physical description of the woman, based on measurements of the various body parts already found and this description was widely circulated. The police regarded the name of L.E. Fisher, stencilled into the underwear found wrapping parts of the body, as an important clue that may lead to her identification. Several people reported missing female relatives that fitted the description.

By Friday 7th June several other missing portions of the body began to be discovered. A section of the lower right leg and foot were picked up by gyspy Solomon Hearne on the foreshore near Wandsworth Bridge in Fulham (an area of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham in South West London), wrapped in the same tweed Ulster coat fragments as the previous finds. The left leg and foot were found near Limehouse (district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in East London) by lighterman Edward Stanton, this piece was wrapped in the sleeve of the same Ulster. A liver and other portions of supposed abdominal flesh, were also found around this time in the Thames by nitric acid maker David Goodman and the Inspector Hodson of the Thames Division dully passed it on to Dr. Kempster to be analysed and assessed as to whether they came from the same body or not. The police and large numbers of volunteers, including the Royal Humane society, were engaged in searches and dredging along the river in the Battersea area. A portion of lung was discovered at Palace Wharf, Vauxhall (Surrey, Central London) and brought to Dr Kempster at Battersea, all the found pieces were preserved in spirits and doctors were of the opinion that there was no doubt they all belonged to the same body. Portions of the clothing that accompanied the finds were taken along to the Bridge Road police station at Battersea in order that they could be inspected by anyone who may have been missing a female friend or relative fitting the description. An inquest was also held at Pimlico (City of Westminster) concerning the body of a newborn female child found bundled in ragged, filthy clothing and bedding and dumped in an underground station near Edbury Bridge. There was some suspicion that this may have connection with the case under investigation, based on some press reports that the victim found in the Thames had been delivered of a child recently. The cause of death of this child could not be ascertained however.

On Friday 8th June the left arm and hand turned up in the river Thames off Bankside. Dr Kempster described the hands as pale delicate and genteel and evidently that of a person who was in a superior position in life, although the nails had been bitten down to the quick. There were marks from a ring being removed later discovered on the left hand, indicating the deceased had probably been married. Vaccination marks were also found upon the arm. This time the limb was wrapped in brown paper and tied up with string.

On the Saturday afternoon the buttocks and the bony pelvis, with all the organs missing, were picked up near Battersea steam boat pier. These parts were all found to correspond with other parts found among the first discoveries at Horselydown a few days earlier. The bladder was said to have been cut through in the pubic arch. According to the Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper of Sunday 9th June, a strange discovery was made on examining the buttocks closer. A fine piece of linen, approximately 9.5in. by 8in., possibly a handkerchief, was found rolled up and pushed into the back passage: “The third portion of the trunk consisted of the pelvis from below the third lumbar vertebra. The thighs had been taken off opposite The hip joints by long, sweeping incisions through the skin, muscles and tissues down to the joint, the heads of the bones neatly disarticulated… The pelvis contained the lower part of the vagina and the lower part of the rectum, the front part of the bladder including the urethra…”

The right thigh was also found the same day in the garden of the poet Sir Percy Byshee Shelley’s Chelsea house, which was being rented out to another occupier at the time. It was very much decomposed and wrapped in some more portions of the now familiar Ulster coat as well as what appeared to be the coarse fabric pocket of an apron, similar to those used by meat or fish salesman or costermongers.

On the 10th June the right arm and hand were found floating in the Thames off Newton’s Wharf near Blackfriars Bridge. The only portions of the body still missing were the heart, lungs, head and neck and the intestines. By Tuesday the 11th June no further human remains had been discovered and it was doubted whether any further portions would turn up, although on the 12th June the remains of a male foetus, of approximately 5 or 6 months gestation, was found floating in the river near Whitehall, in a jar similar to the ones used for pickles, the doctors were undecided if this had any connection to the case in hand.

Drs Bond, Charles A. Hebbert and Kempster then made their final examination of all the remains at the Battersea mortuary in preparation for making their final report to the Commissioners of Police. It was conclusively established that the remains were that of a woman under the age range of twenty five, and approximately 5ft. 5 in. tall with bright reddish-golden hair. It was believed from the condition of the hands, showing no signs of hard labour or manual work, that the murdered woman had occupied a better position in life than was indicated by the clothing found with the body.

‘The Times’ of 13th June reported that the body was accompanied by “an old brown linsey dress, red selvedge, two flounces round the bottom, waistband made of small blue-and-white check material like duster clothe, a piece of canvas roughly sewn on the end of the band, a large brass pin in the skirt and a black dress button, about the size of a threepenny piece, with lines across in the pocket.” The torn pieces of Ulster’s coat was get with a black cross-hatching pattern forming a check design. The material was of good quality but old.

Inquest

On Saturday the 15th June, the inquest on the circumstances surrounding the death of the woman whose mutilated remains were found over a 12 day period in June, in and around the Thames, was opened at The Star and Garter Battersea by Mr A. Braxton Hicks, coroner for Mid Surrey. No less than 23 witnesses were in attendance that day. Dr Thomas Bond handed the coroner a lengthy report on the medical findings and the description of the woman was again repeated including the fact that she was pregnant by about seven to eight months and undelivered at the time of her death, the unborn child having been removed, by an incision into the uterus after the mother’s death. Dr Bond went on to state that as part of the stomach was missing there was no way of knowing if the victim had been administered drugs of any kind, but he had seen no trace of instruments having been used for an unlawful purpose. The cause of death could not be determined as the head, throat, lungs and heart had never been recovered, although attempts had been made to recover the head using the dog, Smoker, who had been successful at discovering missing parts in the Whitehall case. He also stated that the medical men had concluded that “the division of the parts showed skill and design: not, however, the anatomical skill of a surgeon, but the practical knowledge of a butcher or a knacker. There was a great similarity between the condition, as regarded cutting up, of the remains and that of those found at Rainham, and at the new police building on the Thames Embankment.”

Various witness testimonies were then heard, describing the finding of the various portions of the body, including the testimony of Joseph Churcher, sub inspector of the Thames police, who had found the buttocks and pelvis. He repeated the fact, that this portion of the body had a piece of linen placed inside it. The full details as reported in the earlier Lloyd’s article were not however mentioned in the inquest press reports. At this point it was stated that the identification of the victim was still a mystery and very few people had been to view the remains or clothing by that time. The inquest was then adjourned for two weeks.

On June the 26th, via the central news agency and coinciding with fresh reports that the victim had now been possibly identified as an unfortunate named Elizabeth Jackson, came news of previously undisclosed information that ‘various circumstances connected with the fate of this victim had led to a belief that she was really a victim of the Whitechapel fiend, Jack the Ripper.’ It was reported that this information involved “a nameless indignity inflicted upon the corpse, which it was then considered advisable to suppress in the published reports. That indignity was of a character instinctively to suggest the handiwork of the most brutal of murderers”.

In the 11 days since the last inquest, the Metropolitan police, acting on information received, had been investigating the possibility that the victim was a missing homeless unfortunate named Elizabeth Jackson. She had not been seen by most family or friends since the end of May and her father had expressed concern in a letter to another of his daughters, that the Thames victim may have been his missing daughter Elizabeth.

The identification came about by means of the clothing of the victim, her description, pregnant condition at the time of her disappearance and also the fact that Elizabeth had a scar on her wrist as a result of a childhood accident. This was investigated by the doctors and by lifting away a small amount of skin from the slightly decomposed arm of the victim they were able to locate traces of similar scar on the wrist.

The police traced Elizabeth’s movements up until the time of her disappearance. She had been a frequenter of common lodging houses in the Chelsea area and was last known to have lived at a house in Turk’s Row, close to the Chelsea Barracks. Police discovered she had not been seen in any of her usual haunts or been an inmate of any casual wards, workhouses or hospitals in London since her disappearance. Given that she was destitute, the only option if she had left the London area would have been for her to tramp on foot, but because of her physical condition, police thought this would have been difficult for her and most unlikely. The lodging houses that Elizabeth had lodged from time to time and the areas she promenaded at night were all within a short distance of Battersea Bridge, the area where it was believed that the lighter parts of the body were disposed of from.

Elizabeth had boasted to friends, in particular a close friend nicknamed ‘Ginger Nell,’ that she had been in the habit of remaining in Battersea Park, the area where the upper portion of her trunk had been discovered, after the park gates had been closed to the public. The park was also known to be one of the areas the unfortunate 'promenaded.’ This information gave rise in some newspapers to the theory that Elizabeth had been accosted, murdered and dismembered in the park itself, and that there were serious grounds for connecting the murder of Elizabeth Jackson with the Whitechapel atrocities.

Other reports suggested the idea that there were two main theories connected with this case. One being the abortion theory, the other one being the fact that Elizabeth had been in the habit of sleeping outdoors on the Chelsea Embankment and on disclosure of this fact had been warned, again by her friend 'Ginger Nell,’ that she should be wary of the rough character of the waterside labourers and their treatment of homeless unfortunates. It was believed she may have fallen victim to one of these rough characters that frequented the areas around the Thames and may have been murdered outdoors alongside the Thames or else met her death on board a vessel there.

On Monday July 1st the inquest into the death was resumed before Mr. Braxton Hicks. Elizabeth Jackson’s mother, sisters and various friends and acquaintances of Elizabeth’s were present and gave witness testimony to the effect that they were convinced beyond doubt of the identification of the body found in the Thames as that of Elizabeth Jackson, only Elizabeth’s brother expressed any doubts as to the identification, on account of the description of the 'genteel’ hands. Mention was also made of John Faircloth, who up until that point had remained untraced. Police expressed their eagerness to interview him, whose photograph was in the process of being circulated around various parts of the country, with a view to locating him. Faircloth, a former soldier and punished deserter from the 3rd battalion Grenadier Guards, was said to have been the father of Elizabeth’s child and she had passed herself off as his wife, even wearing a cheap brass ring to carry this off. Police also made it known that the deceased had been seen alive and in the company of a man a little over twenty four hours previous to the first discoveries in the Thames. The inquiry was then adjourned again until Faircloth, and the man seen with Elizabeth on the alleged night of her death could be located by police, descriptions were given of both men. The inquest ended with the coroner making an order for the remains to be buried in the name of Elizabeth Jackson.

By July 8th came news from Scotland Yard that a man named John Faircloth, fitting the description of the paramour of Elizabeth Jackson had been located in Tipton St John, Devon. Sergeant Pope of the Devonshire constabulary communicated with Scotland Yard and Inspector Tunbridge of the Criminal Investigation Department was sent to Tipton to find Faircloth and bring him back to London. Faircloth was found and proved to be the man wanted to help with inquiries into Elizabeth’s death. He proceeded willingly and voluntarily back to London, stating that he had heard no news whatsoever of Elizabeth’s death, and being an illiterate man, had been unable to read anything of the matter. He was however, willing to answer any questions he could to help in the inquiry and would give a full account of his life with Elizabeth and their subsequent split.

As a result of Faircloth’s return to London, the previously adjourned inquest was resumed earlier than had been scheduled. On Monday 8th July Faircloth was the main witness at the inquest. His life with Elizabeth and his whereabouts at the time of her death, and since, were discussed in great detail. The inquest was then adjourned again until the 25th July so as to allow the police to thoroughly check out Faircloth’s story and continue with their investigations.

On July the 17th, between these two inquests, came the reports of the murder of Alice Mckenzie in Castle Alley, Whitechapel. These reports again included comment from The Central News Agency that it was thought by not a few people, that the Thames mystery was also the work of the wretch, believed to have left off after the Mary Jane Kelly murder of 9th November 1888. This was owed principally to the fact that the various portions of the body found, seemed to show that the murderer had taken a fiendish delight in performing mutilations upon it.

On the 25th July, Mr. Braxton Hicks opened his very last enquiry into the circumstances surrounding the death of Elizabeth Jackson. Inspector Tunbridge stated that after exhaustive and thorough efforts by police, the exact whereabouts of the man Faircloth, at the time of the murder of Elizabeth Jackson had been confirmed without a doubt. He was found to have been nowhere in the vicinity of London or within travelling distance for a period of time before the murder. Faircloth had a solid and witnessed alibi for the days leading up to the murder of Elizabeth. The Coroner then stated that was all the evidence. He remarked that this case was somewhat different to the cases that had unfortunately occurred in Whitechapel. This was a case in which a woman had died under circumstances that in themselves were excessively suspicious. He went on to say that everything on the body pointed to the conclusion that the body was that of Elizabeth Jackson and suggested to the jury that a verdict of wilful murder, by some person or persons unknown should be returned. A verdict in accordance with the coroner’s direction was reached and the jury complemented the police engaged on the case on their vigilance and the ability they had shown in bringing the matter to an issue.

Aftermath

The previous press claims that the murder of Elizabeth Jackson could be linked to the Whitechapel fiend; Jack the Ripper soon lost their momentum. By the time of the discovery of the Pinchin Street torso in Whitechapel in September 1889, the press were linking the murder of Elizabeth Jackson to this more recent murder. The two murders were also linked by the press to the previous Rainham and Whitehall mysteries. Inspector Tunbridge, who had been in charge of the Jackson murder investigation, was brought in to view the Pinchin Street torso, along with detectives who had been involved in the other similar cases. It was reported that the general opinion of these detectives was that the mode of dismemberment in all these cases was strikingly similar and there was also an opinion expressed that these murders were of a 'different origin’ to the Whitechapel atrocities.

***

TO KNOW MORE:

Casebook Website – Casebook Message Boards – Debra Arif report on Casebook – Casebook Forums - Dr. Hebberd’s reports on Elizabeth Jackson and the Whitehall Mystery – Casebook Forums - Elizabeth’s location in Battersea Park – Casebook Forums - was Elizabeth’s murder related to abortion? – Casebook Message Boards - L. E. Fisher

JTR Forums - Elizabeth Jackson – JTR Forums - Elizabeth Jackson’s press reports – JTR Forums - Elizabeth Jackson’s as Whitechapel Murders’ victim

Jack The Ripper Tour

Thomas Bond page

Wiki Visually

Red Jack Blogspot (in Italian)

Jack The Ripper German Forum (in German)

BEGG, Paul & BENNETT, John (2014): The forgotten victims.

BEGG, Paul; FIDO, Martin & SKINNER, Keith (1996): The Jack The Ripper A – Z.

BROWNING, Corey (2010): The Darker Side of Evolution, in The Casebook Examiner, NUM. 5, December.

EDDLESTON, John J. (2001): Jack the Ripper: An Encyclopedia.

GORDON, R. Michael (2015): The Thames Torso Murders of Victorian London.

HAMILTON, Allan McLane & GODKIN, Edwin Lawrence (1894): A System of Legal Medicine.

MACNAGHTEN, Sir Melville L. (1914): Days of My Years.

TROW, Meirion James (2011): The Thames Torso Murders.

WHITTINGTON-EGAN, Richard (2015): Mr Atherstone Leaves the Stage. The Battersea Murder Mystery: A Twisting and Tragic Tale of Love, Jealousy and Violence in the age of Vaudeville.

#Elizabeth Jackson#victim#murder victim#victorian women#Violence against women#happy heavenly birthday#Gone But Not Forgotten#1865#1860s#victims#timeline#John Jackson#Catherine Jackson#John Fairclough#1870s#1877#1880s#1888#1889#Mary Minter#Smoker#Smoker the dog#Dr Hibbert#Ginger Nell#Wynne Edwin Baxter#Dr Athelstan Braxton Hicks

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

International Women’s Day (IWD) is celebrated on the 8th of March every year. It is a focal point in the movement for woman’s rights. German revolutionary Clara Zetkin proposed at the 1910 International Socialist Woman’s Conference that 8 March be honored as a day annually in memory of working women. The day has been celebrated as International Women’s Day or International Working Women’s Day ever since.

Women’s rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide, and which formed the basis for the women’s rights movement in the 19th century and feminist movement during the 20th century. Issues commonly associated with notions of women’s rights include the right to bodily integrity and autonomy; to be free from sexual violence; to vote; to hold public office; to enter into legal contracts; to have equal rights in family law; to work; to fair wages or equal pay; to have reproductive rights; to own property; to education.

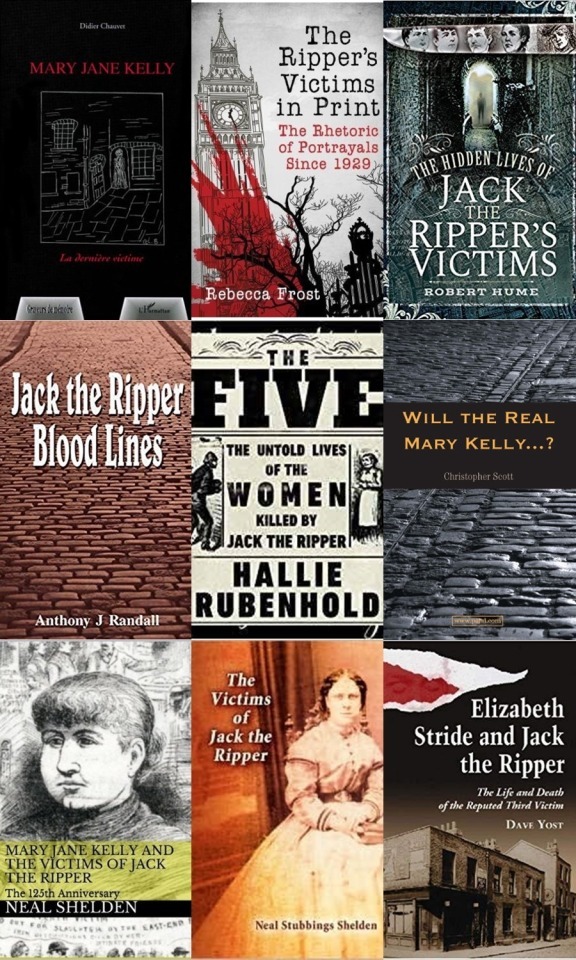

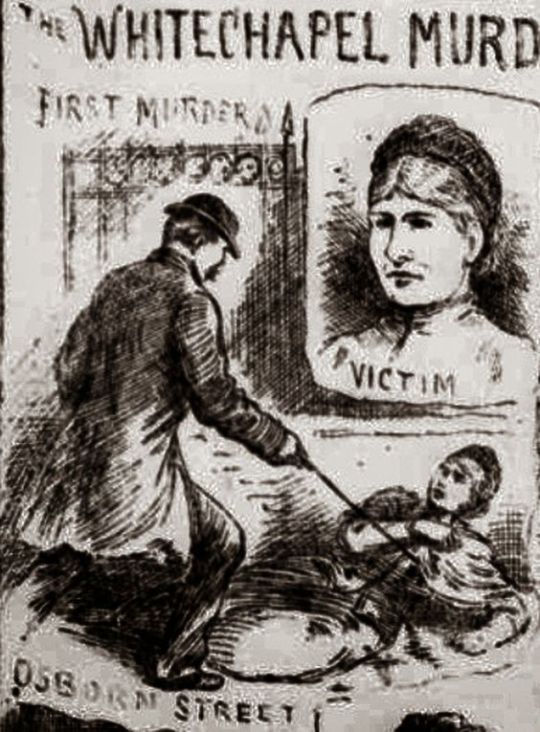

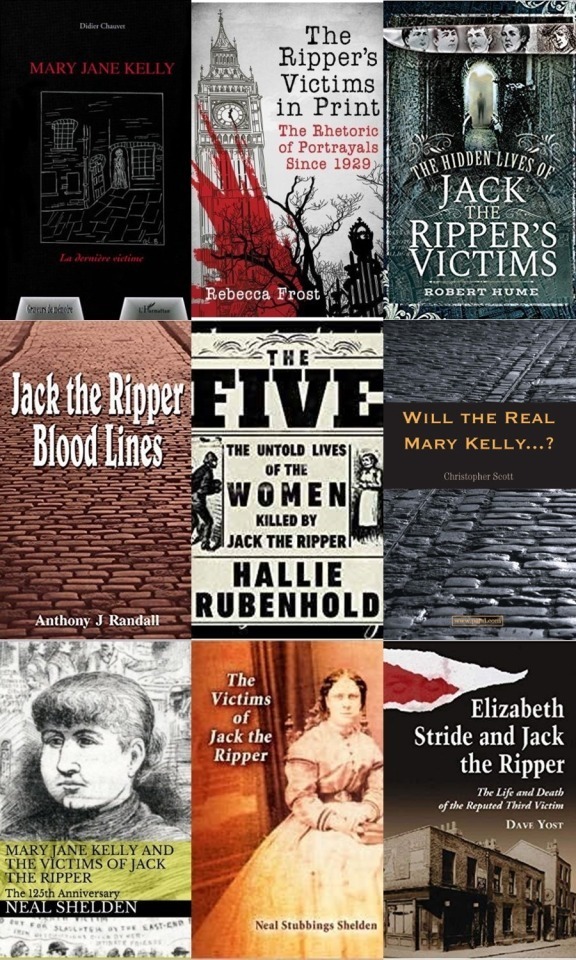

Between 1873 and 1891 eleven poor and working class women (pictured, Ada Wilson, Emma Elizabeth Smith, Martha Tabram, Annie Chapman, Mary Ann Nichols, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, Mary Jane Kelly, Rose Mylett, Alice McKenzie and Frances Coles) were attacked and murdered in London’s East End by a killer(s) who was never caught, and other 7 (including Annie Millwood and Elizabeth Jackson, and 5 unidentified ones) suffered a similar fate. They were murdered just because they were women and their murderer(s) was a misogynistic psycho.

While the killer(s) went onto have a large amount of tours and walks, studies and published works (regarding who he might was, different theories as why he did it), the victims were divided in categories and some of them completely forgotten. So here you find a list of research/non-fiction books about these women if you are interested to know more about them (the list is going to be updated when new books are published, thanks).

· BEGG, Paul & BENNETT, John (2014): The forgotten victims.

· CHAUVET, Didier (2002): Mary Jane Kelly: La dernière victime.

· FROST, Rebecca (2018): The Ripper’s Victims in Print. The Rethoric Portrayals Since 1929.

· HUME, Robert (2019): The hidden lives of Jack the Ripper’s victims.

· KEEFE, John. E. (2010, revisited 2012): Carroty Nell. The last victim of Jack the Ripper.

· RANDALL, Anthony J. (2013): Jack the Ripper. Blood lines.

· RUBENHOLD, Hallie (2019): The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women killed by Jack the Ripper / The Five: The Lives of Jack the Ripper’s Women.

· SCOTT, Chris (2005): Will the real Mary Kelly…?.

· SHELDEN, Neal E. (2013): Mary Jane Kelly and the Victims of Jack the Ripper: The 125th Anniversary.

· SHELDEN STUBBINGS, Neal (2007): The Victims of Jack the Ripper.

· WHITTINGTON-EGAN, Richard (2015): Mr Atherstone Leaves the Stage. The Battersea Murder Mystery: A Twisting and Tragic Tale of Love, Jealousy and Violence in the age of Vaudeville.

· YOST, Dave (2008): Elizabeth Stride and Jack The Ripper.

**

You may be interested in the “A Hidden History of Women in the East End: The Alternative Jack the Ripper tour” to know how these women lived in Victorian Whitechapel.

May they never be forgotten.

**

Please note, if you have/know about more books about these women’s LIVES, you may contact me here. Thank you very much.

#International Women’s Day#Women's Day#Working Women's Day#Victorian Women#Violence Against Women#Special Dates#March 8#women's rights#Ada Wilson#Mary Kelly#Frances Coles#Alice McKenzie#Elizabeth Jackson#Elizabeth Stride#Catherine Eddowes#Martha Tabram#Mary Ann Nichols#Annie Chapman#Annie Millwood#Emily Horsnell#Margaret Hames#Rose Mylett#victorian women#whitechapel murders#Women's history#women's history month

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alice “Clay Pipe” McKenzie

Alice McKenzie (b. Alice Pitts, aka Alice Kinsey, “Clay Pipe” Alice, Alice Bryant, Kelly)

Birth date: March 8, 1845 Attacked and killed (age): July 17, 1889 (44)

Complexion: Freckle-faced Eyes colour: Hazel Hair colour: Auburn Height: 5′4″ (163 cm) Ocupation: Washerwoman and charwoman

Clothes at the time of murder/discovery: A black coat; a brown/black staff skirt; a red staff bodice; a linsey petticoat; black stockings; buttoned boots; a Paisley shawl.

Resting place: Plaistow Cemetery, Bromley.

***

Early Life

Alice McKenzie was born Alice Pitts on March 8th 1845 in the Precincts of Peterborough Minster (Cathedral), Cambridgeshire (England) to Charles Pitts, a post office messenger, and Martha, neé Watson. She had four older siblings, William, John, Martha and Jane, and two younger brothers, Charles and Thomas.

Around 1860, when she was 15, Alice worked for Mrs Strickland in her refreshment rooms in St. John Street, Peterborough. In 1861, aged 17, Alice no longer lived with her family, but in the household of a master brazier named Edward Miller in High Cross Street, Leicester where she was employed as a house servant.

On October 11th1863 Alice Pitts marries Joseph Kinsey or McKenzie, a chair and cabinet maker at All Saints Church, Leicester. Three years later, on 21st July 1866 they became parents of Joseph James at Freeman’s Common, St Mary, Leicester. Sadly, on October 12th of the same year baby Joseph James died of ‘marasmus’ (a form of malnutrition) at 4 Joseph Street, St. Mary, Leicester. The informant was his mother, Alice, who was present at the death. The following year, on 18thFebruary 1867 Joseph Kinsey died aged 25 of tuberculosis at the same place. The informant was Alice Kinsey, then aged around 22, who was present at the death. Notices of Joseph’s death were printed in several local newspapers.

On 31st October 1873, a 27-year-old laundress named Alice McKenzie, widow of carpenter Joseph McKenzie was convicted of ’D & R’ at Southwark police court. She was fined 10s and sentenced to 7 days imprisonment with hard labour, which she served in Wandsworth Prison. She was described as 5ft 4 ½ ins tall, with Auburn hair, hazel eyes and pale complexion. She was released on 6th November, 1873. Prior to that, she had already been convicted, but the details haven’t arrived to this day.

Later life

She was later to move into the East End of London sometime before 1874. On August 13th 1875 she was admitted to the Whitechapel Infirmary from Leman Street police station because she was ‘Ill and destitute’. She was discharged on 20thAugust, 1875. She went there again on June 14th 1877 due to an ulcer and stayed until the 23rd. On August 1st she was admitted to the St George Workhouse, Mint Street, Southwark having been charged with being drunk but was discharged the same day.

On March 1878 her father Charles Pitts died in Peterborough, aged 74. On June 26th, a 32-year-old laundress and hawker was convicted at Southwark police court of being ‘drunk in a thoro'fare’. She was fined 5s and sentenced to 7 days imprisonment with hard labour, which she served in Wandsworth Prison. She was released on 2nd July, 1878.

From 1883 Alice lived, off and on, with an Irishman named John McCormack (also Bryant) who was in the employ of some Jewish tailors in Hamburg Street as a porter, at various East End common lodging and doss-houses. On August 11th, aged 37, she was admitted to the Whitechapel Infirmary due to an ulcer and she was discharged on 24th August. From November 5th to 16th she was admitted to the workhouse infirmary by a policeman who found her drunk in ‘Dorset Street’. On December 20th another policeman brought her to the Whitechapel Infirmary for alcoholism and fits. She was discharged on 23rd December.

On December 1885 her mother Martha Pitts died in Peterborough, aged 74.

Last months and murder

On January 1889 Alice was arrested for causing a disturbance in a butcher’s shop in Long Causeway, Peterborough, very near the Minster Precincts. Besides that, Alice worked for her Jewish neighbours as a washerwoman and charwoman, and from April she resided with John McCormack mainly at Mr. Tenpenny’s common lodging house, 52 Gun Street, Spitalfields. It was managed by Mrs. Elizabeth Ryder, wife of Richard John Ryder. At this time, Alice was around 43 years of age, described as a freckle-faced woman with a penchant for both smoke and drink. She preferred the smoke of a pipe, which was soon to grant her the name “Clay Pipe” Alice by her friends and acquaintances. Her left thumb was also injured in what was no doubt some sort of industrial accident.

On Tuesday 16th July 1889 she spent the day at the common lodging house but the evening possibly at the Cambridge Music Hall with a blind boy. From 11:30pm to midnight, Alice chatted with three women, Margaret Franklin, Catherine Hughes and Sarah Marney in Flower and Dean Street, and then left alone toward Whitechapel.

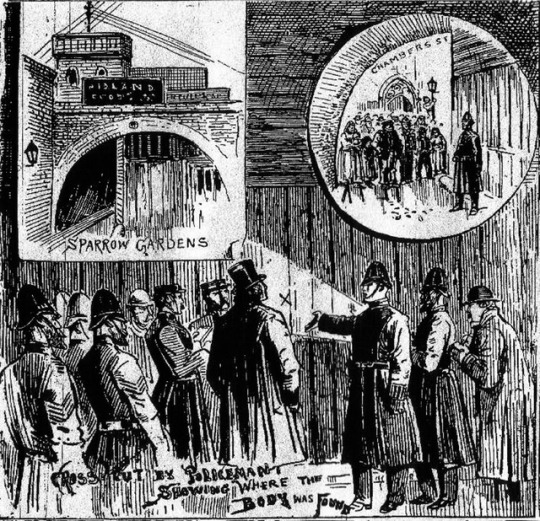

On Wednesday 17th July, at 12:15am Police Constable Joseph Allen took a break under a street lamp in Castle Alley, a dark and dismal snickleway that led off Whitechapel High Street, for a bite to eat. The narrowness and overall dismalness of this alley had, for several years prior, been the subject of much comment in the local press, and this latest Whitechapel murder led to calls for the local authority to “do something” about its condition. According to Allen the alley was completely deserted. After about five minutes, Allen noticed another constable entering the alley. It was P.C. Walter Andrews, who remained in the alley for about three minutes. He saw nothing of a suspicious nature.

At about 12:25am, Sarah Smith, deputy of the Whitechapel Baths and Washhouses (which lined Castle Alley) retired to her room. She began reading in bed, the closed window of her room overlooking the entire alley. Sarah later testified she heard nothing suspicious until she heard the blow of Andrews’ whistle.

At 12:45am it began to rain in Whitechapel. Five minutes later, P.C. Andrews returned to Castle Alley on his regular beat, about twenty-seven minutes having passed since he left the area. This time, however, he discovered the body of a woman lying on the pavement, her head angled toward the curb and her feet toward the wall. Blood flowed from two stabs in the left side of her neck and her skirts had been lifted, revealing blood across her abdomen, which had been mutilated.

The pavement beneath the body of Alice was still dry, placing her death sometime after 12:25am and before 12:45am, when it began to rain. In her possession were found a clay pipe often referred to as a ‘nose warmer’ and a bronze farthing. She was noticed to have been wearing some ‘odd stockings.’ P.C. Andrews heard someone approaching the alley soon after, it was Isaac Lewis Jacobs, of Old Castle-street, who was running home when the police-constable came towards him and asked him “for God’s sake” to go to the woman and stand by while he called assistance. Lewis went to the spot while the constable was blowing his whistle. At 1:10am Inspector Edmund Reid arrived only moments before the Divisional Police Surgeon, Dr George Bagster Philips, and noted that blood was still flowing, but by when Philips arrived, about 1:12am, he pronounced life extinct.

It would be several hours before the body was identified, in the meantime a description was circulated to the newspapers, with one peculiarity: part of the nail on the thumb on the left hand was deficient. The papers also mentioned the clay pipe found near the body. Several hours elapsed before the woman was identified, but John McCormack came forward during the day and recognised her. He stated that he did not know whether the deceased had been married, and that the reason of her going out last night was that they had had a slight quarrel, and that she had never, to his knowledge, been out late at night previously. He also said that she was a hard-working woman and was very much upset about her fate. He also identified the clay pipe as belonging to her.

Investigation

Dr. Philips performed the post-mortem and declared that the cause of death was from severance of the left carotid artery. She also suffered two stabs in the left side of the neck , some bruising on chest and five bruises or marks on left side of abdomen. Cut was made from left to right, apparently while McKenzie was on the ground. The body also presented a long (seven-inch) ‘but not unduly deep’ wound from the bottom of the left breast to the navel, seven or eight scratches beginning at the navel and pointing toward the genitalia and small cut across the mons veneris. Dr. Phillips believed there was a degree of anatomical knowledge necessary to have committed the atrocities to McKenzie.

The mutilations committed upon McKenzie were mostly superficial in manner, the deepest of which opened neither the abdominal cavity nor the muscular structure. The wounds also suggested that the killer was left-handed (as opposed to the Ripper being right-handed). Phillips suggested the five marks on the left side of her body were an imprint of the killer’s right hand, which left only his left hand to facilitate the injuries. Dr. Thomas Bond disagreed, claiming there was no evidence to support the theory that those marks were made through such processes (admittedly, Bond saw the body the day after the post mortem, and it had already begun to decompose). The weapon was agreed upon to have been a ‘sharp- pointed weapon,’ although it could be smaller than the one used by the Ripper.

Phillips ultimately claimed that McKenzie’s death was not attributable to the Ripper. Dr. Thomas Bond chose the opposite conclusion, telling Sir Robert Anderson he believed it was indeed a Ripper killing, but Anderson himself disagreed, writing: “I am here assuming that the murder of Alice McKenzie on the 17th of July 1889, was by another hand. I was absent from London when it occurred, but the Chief Commissioner investigated the case on the spot and decided it was an ordinary murder, and not the work of a sexual maniac.” Inspector Frederick Abberline also believed this was not a Ripper murder.

Commissioner James Monro, who had replaced Sir Charles Warren in the position, was on duty during the investigation since Anderson was on leave at the time, and disagreed: “I need not say that every effort will be made by the police to discover the murderer, who, I am inclined to believe, is identical with the notorious Jack the Ripper of last year.” In fact, on the day of the murder, Monro deployed 3 sergeants and 39 constables on duty in Whitechapel, increasing the force with 22 extra men.

At the inquest, which was held on July 17th and 19th, and later adjourned to August 14th, Coroner Wynne Edwin Baxter acknowledged that Alice could have been either killed by the Ripper or another killer, and concluded: “There is great similarity between this and the other class of cases, which have happened in this neighbourhood, and if the same person has not committed this crime, it is clearly an imitation of the other cases.” The conclusion was the all too familiar ‘murder by a person or persons unknown.’

Aftermath

The Scotland Yard Files pertaining to the McKenzie murder detail an interesting sidebar concerning an individual named William Wallace Brodie, who confessed to murdering the woman. It was earlier printed in the Kimberley Advertiser of June 29th, 1889 that Brodie had confessed to all the Whitechapel murders while in a drunken stupor. His statement was forwarded by Chief Inspector Henry Moore, but Superintendent Thomas Arnold gave instructions to dismiss Brodie as of unsound mind. Scotland Yard gave the same prognosis: “Let him be charged as a lunatic.” It was soon discovered that Brodie had a conviction for larceny, and just to be sure, enquiries were made into his character and location during the Whitechapel Murders. It was found that he was in South Africa between September 6th, 1888 and July 15th, 1889. Ultimately, Brodie was released from custody, but was almost immediately rearrested for fraud.

Alice was buried in Plaistow Cemetery (East London) on Wednesday 24th July, 1889.

***

To know more:

Wikipedia

Casebook website – Casebook Forum – Casebook Wiki

Jack The Ripper.org

Jack The Ripper Tour

JTR Forums (where all her family and early years information comes from!)

Jack The Ripper Map

Historic Mysteries

BEGG, Paul (2013): Jack The Ripper. The Facts.

BEGG, Paul & BENNETT, John (2014): The forgotten victims.

BEGG, Paul; FIDO, Martin & SKINNER, Keith (1996): The Jack The Ripper A – Z.

EDDLESTON, John J. (2001): Jack the Ripper: An Encyclopedia.

EVANS, Stewart P. & RUMBELOW, Donald (2006): Jack the Ripper: Scotland Yard Investigates.

EVANS, Stewart P. & SKINNER, Keith (2001): Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell.

GRAY, Drew D. (2010): London’s Shadows. The Dark Side of the Victorian City

JAKUBOWSKI, Maxim & BRAUND, Nathan (1999): The Mammoth Book of Jack The Ripper.

MARRIOTT, Trevor (2005): Jack the Ripper: The 21st Century Investigation.

PRIESTLEY, Mick P. (2018): One Autumn in Whitechapel.

RUMBELOW, Donald (2004): The Complete Jack the Ripper: Fully Revised and Updated.

TROW, M. J. (2009): Jack The Ripper: Quest for a Killer.

#Alice McKenzie#happy heavenly birthday#1840s#1845#victim#victims#victorian women#Violence against women#timeline#Charles Pitts#Martha Pitts#family#1860s#1860#Mrs Strickland#1861#Edward Miller#1863#Joseph Kinsey#1866#Joseph James Kinsey#1867#1870s#1873#1875#1877#1878#1880s#1883#John McCormark

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Valentine’s Day

Valentine’s Day, also called Saint Valentine’s Day or the Feast of Saint Valentine, is celebrated annually on February 14. It originated as a Western Christian feast day honouring one or two early Christian martyrs named Saint Valentine and is recognized as a significant cultural, religious, and commercial celebration of romance and love in many regions of the world.

As it is still widely but wrongly believed that the Whitechapel murder victims of the late Victorian era were prostitutes, we want to list all the men who loved them and who were loved by them. Some of these relationships, specially the later ones, were casual or marked by abuse. Nonetheless, they defined these women, so we will list all the known facts here:

• Margaret Hames: m. John Hames (his death).

• Annie Chapman: m. John Chapman (1869 - 1884), r. John Sivvey (1886 - 1887), r. Edward Stanley (1888).

• Catherine Eddowes: r. Thomas Conway (1862 - 1881), r. John Kelly (1881 - 1888, her murder).

• Elizabeth Stride: r. Unknown policeman (late 1860s), m. John Thomas Stride (1869 - 1881), r. Michael Kidney (1885 - 1888).

• Emily Horsnell: m. Alfred Horsnell (1880 ~ 1886).

• Alice McKenzie: m. Joseph Kinsey (1863 - 1867, his death), r. John McCormack (1883 - 1889, her murder).

• Mary Ann Nichols: m. William Nichols (1861 - 1881), r. George Crawshaw (1881 - 1882), Thomas Stuart Dew (1884 - 1887).

• Martha Tabram: m. Henry Samuel Tabram (1865 - 1875), r. Henry Turner (1876 - 1888).

• Annie Millwood: m. Richard Millwood (his death).

• Frances Coles: r. James Murray (1883 ~ 1886), r. James Thomas Sadler (1889 - 1891, her murder).

• Rose Mylett: m. Thomas Davis (1880 ~ 1888), r. Benjamin Goodson (1888, her murder).

• Mary Kelly: m. Unknown name Davies (1879 ~ 1881, his death), r. Joseph Fleming (1886 - 1887), Joe Barnett (1887 - 1888).

• Ada Wilson: m. Samuel Wilson (1888 ~ 1891).

• Elizabeth Jackson: r. Charlie Uknown surname (unknown), r. John Fairclough (1888 - 1889).

NOTE: r = relationship, m = married.

#Valentine's Day#February 14#love#victorian women#Special Dates#Margaret Hames#Annie Chapman#Catherine Eddowes#Elizabeth Stride#Emily Horsnell#alice McKenzie#Mary Ann Nichols#Martha Tabram#Annie Millwood#Frances Coles#Rose Mylett#Mary Kelly#Ada Wilson#Elizabeth Jackson#relationship#partner#Valentines

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Frances Coles

Part 1

Frances Coles was 5" (152 cm), slender, with dark brown hair, brown eyes and fair complexion. She was wearing a second-hand black diagonal jacket, a black dress given by her sister that reached to her ankles, and a black velvet ribbon around her neck. Gloves were a luxury she couldn’t afford, but she also wore a black bonnet trimmed with beads. It would have been unladylike to step outside without any kind of hat, specially after dark.

Last hours and murder

Thursday February 12, 1891:

4:00 PM: Around 4:00 Frances and James Thomas Sadler went into a pub called The Bell, at Middlesex Street, at the City. He ordered 2 glasses of gin and gave one to Frances, who told him she needed a new bonnet. After some words, finally Sadler told her that she could look for one later, that he would pay it. They were there for about an hour, and when they left, they went on separate ways.

5:00 PM: Frances walked around the corner to Shuttleworth’s Coffee House on Wentworth Street, Whitechapel, and ordered a cup of tea. 20 minutes later Sadler came and joined her. Anne Shuttleworth, the owner’s wife, later testified at the coroner’s inquest that both were perfectly sober. They left about quarter to six. Sadler gave her a penny to buy a pair of cheap earrings made from vulcanite (a hard ebony-coloured rubber) as they had passed a peddler’s shop in Brick Lane. Their next stop was a pub called The Marlborough Head on Brick Lane. Sadler bought drinks for some of the customers and bought some lottery tickets. There is some question as to exactly what he and Frances had to drink as the witnesses at the inquest didn’t agree, but Sadler himself testified he was becoming quite drunk.

7:00 PM: Sometime around 7:00~7:30PM, Frances went to a ladies’ hat shop at 25 Nottingham Street, Bethnal Green, and purchased a new black crépe hat with the 2s. 6d. Sadler had given her some hours before. Peter Hawkes, the owner’s son and the man who sold the hat to Frances, later commented to police that she was “three sheets in the wind.” She looked at several hats before deciding which one to choose, and when he told her the price, she stepped outside and spoke to Sadler and then payed for the hat. For the price of the hat she could have gotten almost 6 nights lodging in a doss house. She took her old hat with her. Sadler told her to throw the old one, but she wanted to keep it so she pinned it under her long skirt.

8:00 PM - 9:00 PM: At some point in this interval, Sadler told her he was going to meet a friend on Spital Street and gave her a Schilling and told her to pick some drinks and go back to Spitalfields Chambers and get a double bed. She went with him part on the way, but when he turned to start walking on Thrawl Street she tugged on his arm. It was a very dangerous Street and she knew it because she had lived there for almost 8 years. “Don’t go that way,” she said. “ The street is full of thieves. They wouldn’t think anything about robbing a sailor.” to which Sadler replied: “I’ve travelled all over the world, and in all kinds of company, and I’ve never yet turned back on anything. I ain’t going to fence this street.” and kept on walking. He should have listened to her. He hadn’t gone 50 yards before a woman in a red shawl came up behind him and hit him over the head with a folded umbrella. He fell on the ground and two men came from the shadows and began to kick him in the ribs. They took his wallet and his swatch. When Sadler got up he suddenly became extremely angry at Frances. “You’re a pretty pal, to see me knocked about like this and not do anything for me,” he said. She was stunned. “How could I, Jim? You know if I’d lifted a finger for you I would have been marked by those people, and they’d pay me out when they got the opportunity”. “I was then penniless,” he said, “and I had a row with Frances for I thought she might have helped me when I was down.” They went separate ways.

10:00 PM: Frances is drunk when returns to their lodgings at Spitalfields Chambers in White’s Row, according to the 34 year-old night Watchman Charles Guiver. She sits at a bench in the kitchen, rests her head on her arms, and quickly falls asleep.

11:30 PM: Sadler soon returns, face bloodied and bruised, and in a belligerent mood. “I have been robbed,” he says, “and if I knew who had done it I would do for them.” He asked Frances if she had the money he gave her for their bed, but she replied she didn’t have it, and drifted back to sleep on the table. Sadler thought they may would trust her for one night. Although Sadler had no money, he was also owed four pounds and fifteen Schillings for the seven weeks he worked since the S. S. Fez sailed on December 24, but he planned on collecting the money the following morning. Guiver helped Sadler wash up in the back yard but was forced to ask him to leave as he hadn’t the money for a room.

Friday February 13, 1891:

12:00 AM: James Sadler leaves the Spitalfields Chambers. Frances remains on the bench at the table, fast asleep.

12:30 AM: Frances wakes up, according to lodger Samuel Harris, and leaves White’s Row since she also lacks her doss money. Sarah Fleming, the lodging house deputy wathed her leave too and said it was just after midnight. According to watchman Guiver, however, Frances wasn’t to leave until around 1:30 or 1:45 AM.

1:30 AM: Joseph Haswell, an employee in Shuttleworth’s eating house in Wentworth Street, is asked by Frances Coles for three halfpenceworth of mutton and some bread. She eats her meal alone in the corner, remaining there for some fifteen minutes. Hassell asks her to leave three times, but Frances refuses, telling Haswell, ‘Mind your own business!“ She finally leaves about 1:45 AM and headed toward the direction of Brick Lane through Commercial Street.

1:45 AM: Frances bumps into fellow prostitute Ellen Callana (also Calana, Colanna, Callaran, Callaron, Callagher, Callaghan, O’Connor) on Commercial Street. Soon afterward a short “violent man in a cheesecutter hat”, with a dark moustache approached Calana, took her to one side and and solicited her. He was wearing a pea jacket, a cheese cutter hat, dark blue trousers and “shiny boots” according to Callana. Calana decided to refuse his offer. The man punched her in the face, giving her a black eye, then walked over to Frances, who was standing about ten or twelve feet away. Ignoring Calana’s advice, Frances walks away with the stranger, headed in the direction of the Minories.

1:50 AM: James Sadler got into his third brawl of the night with some dockworkers at St. Katharine Dock as he tried to force his way back onto the S.S. Fez, from which he had been discharged two days before. He was left bleeding from a rather sizable wound in the scalp after calling his attackers “dock rats.” He then made two attempts to enter a lodging house in East Smithfield, but was refused. Around ten minutes later, Sadler was seen drunken and bloodied on the pavement outside the Mint by a Sergeant Edwards. He was ’decidedly drunk’ at the time.

2:00 AM - 2:12 AM: Carmen William Friday (also known as ‘Jumbo’) and two brothers named Knapton walked through Swallow Gardens, a railway arch. They saw nothing out of the ordinary, only a man and a woman at the Royal Mint Street corner of Swallow Gardens. One of the Knapton brothers shouted “Good night” to the couple but received no response. 'Jumbo’ Friday was later to say that the man looked like a ship’s fireman, and that the woman was wearing a round bonnet.

2:15 AM: P.C. Ernest Thompson 240H was on his beat along Chamber Street, only minutes away from Leman Street Police Station. He had been on the police force less than two months, and this was his first night on the beat alone. Thomspon heard the retreating footsteps of a man in the distance, apparently heading toward Mansell Street. Only a few seconds later he turned his vision to the darkest corner of Swallow Gardens and shined his lamp upon the body of Frances Coles. Blood was flowing profusely from her throat, and to Thompson’s horror, he saw her open and shut one eye. Since the then unidentified woman was still alive, police procedure dictated that Thompson remain with the body – his inability to follow the retreating footsteps of the man he believed to have been her killer would haunt him for the rest of his days. Thompson was later stabbed to death in 1900 when trying to clear a brawl at a coffeehouse by a man named Barnett Abrahams.

2:25 AM: PC Frederick Hyde 161H was the first to come to Thompson’s assistance, followed by plain-clothesman George Elliott. They found a local doctor, Dr. Frederick Oxley and rushed him to the scene. Chief Inspectors Donald Swanson and Henry Moore would later arrive around 5:00 AM, with Robert Anderson and Melville Macnaghten following later that morning.

3:00 AM: Sadler returned to the lodging house at 8 White’s Row, heavily bloodstained from being robbed in Ratcliff Highway. The deputy, Sarah Fleming, turned him out, noticing he was so drunk he could barely stand or speak. He protested. “You are a very hard-hearted woman. I have been robbed of my money, of my tackle and half a chain.”

5:00 AM: Sadler’s injuries from his many fights the previous night finally catch up to him and he admitted himself into the London Hospital for brief treatment.

10:15 AM: Duncan Campbell, a seaman at the Sailor’s Home in Wells Street, allegedly purchased a knife from Sadler for the price of a shilling and a piece of tobacco. The knife was blunt. In fact, Thomas Robinson, a marine stores dealer who later purchased the knife from Campbell, testified that the knife was so blunt that he had to sharpen it before he could use it at dinner.

February 27, 1891:

The jury returned a verdict of “Willful Murder against some person or persons unknown” on February 27, and four days later the Thames Magistrate’s Court dropped all charges against Sadler. As he left the court, crowds of people cheered his release.

Many people at Scotland Yard, and even Sir Melville Macnaghten continued to press the belief that Sadler was guilty of the murder of Frances Coles, and the sides are split among contemporary researchers whether or not Sadler was the killer.

Photos from Escrito con Sangre blog.

Source: Casebook

BEGG, Paul (2013): Jack The Ripper. The Facts.

BEGG, Paul & BENNETT, John (2014): The forgotten victims.

BEGG, Paul; FIDO, Martin & SKINNER, Keith (1996): The Jack The Ripper A – Z.

BROWN, Bernie: My funny Valentine, in Ripperologist No. 27, February 2000.

COOK, Andrew (2009). Jack the Ripper.

EDDLESTON, John J. (2001): Jack the Ripper: An Encyclopedia.

EVANS, Stewart P. & RUMBELOW, Donald (2006). Jack the Ripper: Scotland Yard Investigates.

EVANS, Stewart P. & SKINNER, Keith (2000). The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook: An Illustrated Encyclopedia.

FIDO, Martin (1987). The Crimes, Death and Detection of Jack the Ripper.

JAKUBOWSKI, Maxim & BRAUND, Nathan (1999): The Mammoth Book of Jack The Ripper.

KEEFE, John. E. (2010, revisited 2012): Carroty Nell. The last victim of Jack the Ripper.

MAGELLAN, Karyo (2005): By Ear and Eyes: The Witechapel Murders, Jack the Ripper and the Murder of Mary Kelly.

NELSON, Scott: Coles, Kosminski and Levi – Was There a Victim/Suspect/Witness connection?, in Ripperologist, 2001.

PRIESTLEY, Mick P. (2018): One Autumn in Whitechapel.

SCOTT, Christopher (2004): Jack The Ripper. A cast of Thousands.

#Frances Coles#Carroty Nell#victim#victims#violence against women#victorian women#on this day#otd#1891#1890s#victorian clothes#victorian clothing#possessions#gone but not forgotten#gone but never forgotten#rest in peace#victorian women's fashion#James Thomas Sadler#James Sadler#Anne Shuttleworth#Peter Hawkes#Ellen Callana#PC Ernest Thompson#Donald Swanson#Henry Moore#Melville Macnaghten

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Global Movie Day

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences established Global Movie Day, a day for film fans around the world to celebrate their favorite movies and engage with Academy members and filmmakers across social media. The inaugural holiday was held last year (the day before the 92nd Oscars).

The second annual Global Movie Day was held on Saturday, February 13, 2021.

On Victorian times movies were in their infancy, but there are some movies and films that portrayed the Whitechapel Murder Victims. As away of tributing these women, we decided to celebrate Global Movie Day by posting films that featured them.

A Study in Terror (1965)

In this story about Sherlock Holmes against Jack The Ripper, Kay Walsh played the role of Catherine Eddowes:

Mary Ann Nichols was played by Christiane Maybach:

Barbara Windsor played Annie Chapman, Edina Ronay played Mary Kelly and Norma Foster played Elizabeth Stride:

Murder By Decree (1979)

In this new Sherlock Holmes against Jack the Ripper film, Susan Clark was Mary Kelly:

Other actresses in this short are: June Brown as Annie Chapman, Hilary Sesta as Catherine Eddowes, and Iris Fry as Elizabeth Stride.

From Hell (2001)

In this film based on Alan Moore's graphic novel of the same name, Annabelle Apsion was Mary Ann 'Polly' Nichols, Lesley Sharp was Catherine Eddowes, Katrin Cartlidge was Annie Chapman, Heather Graham was Mary Jane Kelly, Samantha Spiro was Martha Tabram, and Susan Lynch was Elizabeth "Long Liz" Stride

Ginger (2016)

In the 2016 short "Ginger", Katie Jarvis plays the role of Mary Kelly:

Other actresses in this short are: Karen Brace as Annie Chapman, Lena Margareta as Elizabeth Stride, and Tracy-Lee Gardener as Catherine Eddowes.

#Global movie day#Special Dates#Movie#Film#Short#A Study in Terror#Kay Walsh#Catherine Eddowes#Mary Ann Nichols#Christiane Maybach#barbara windsor#Annie Chapman#edina ronay#mary kelly#norma foster#elizabeth stride#Murder By Decree#Susan Clark#Annabelle Apsion#Lesley Sharp#Katrin Cartlidge#Heather Graham#Samantha Spiro#Martha Tabram#Susan Lynch#Ginger 2016#Katie Jarvis#popular culture#movie#film

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ada Wilson

Ada Wilson (b. Zoa Ada Bisdey Elbury)

Birth date: 1863 Attacked: March, 1888 (ca. 25, survived) & 25th June 1891 (ca. 28, survived) Death (age): August 24th 1952 (aged 89)

Complexion: ? Eyes colour: ? Hair colour: ? Height: ? Ocupation: Seamstress, tailoress, waterproof hand clothes making.

Resting place: ?

***

Early life

Zoa Ada Bisdey Elbury was born in 1863 in Bristol, to Henry Edwin Elbury and Emma Fry. They married shortly before she was born. He had been born and bred in Bristol, and she was from Somerset. Henry’s father and elder brother were both stoneware potters – he followed them into this occupation, and seemed to do reasonably well. By 1871, Henry and Emma had been married for eight years, and had three children – Ada, Charles and Henry – and a servant. They lived in what seems to have been reasonable comfort on Clarence Square, in Bedminster, Bristol.

In the circumstances, it is hard to know whether the family’s next appearance in the census – at 39 Stratfield Road, in Bromley St Leonard, signified a reversal of fortunes. If guests and auxiliaries were anything to go by, then they had a lodger in 1881, rather than a servant. There were more mouths to feed (Rose, Emma and Thomas) and Ada, now 17, was earning her living – as a tailoress.

1888 Attack

Ada Wilson lived at 9 Maidman Street, Burdett road, a small thoroughfare lying midway between the East India Dock and Bow roads in Bow, a district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in East London. On March 28, 1888, at 12:30am while she was at home she was attacked by a man of about 30 years of age, 5ft 6ins in height, with a sunburnt face and a fair moustache. He was wearing a dark coat, light trousers and a wide awake hat. According to Ada, the man was a completely unknown, and forced his way into the room and demanded money, and when she refused he stabbed her twice in the throat with a clasp knife and ran, leaving her for dead. It is reported that nearby neighbours almost captured the man, but he found his escape.

Witness and neighbour Rose Bierman, a young Jewess who lived upstairs with her mother at the same building as Ada, explained that she knew Ada was married but didn’t know her husband, and that she was always getting visitors. About the man who attacked her she said that “whether he was her husband or not I could not say.(…) Well, I don’t know who the young man was, but about midnight I heard the most terrible screams one can imagine. Running downstairs I saw Mrs. Wilson, partially dressed, wringing her hands and crying, ‘Stop that man for cutting my throat! He has stabbed me!’ She then fell fainting in the passage. I saw all that as I was coming downstairs, but as soon as I commenced to descend I noticed a young fair man rush to the front door and let himself out. He did not seem somehow to unfasten the catch as if he had been accustomed to do so before. He had a light coat on, I believe. I don’t know what kind of wound Mrs. Wilson has received, but it must have been deep, I should say, from the quantity of blood in the passage. I do not know what I shall do myself. I am now ‘keeping the feast,’ and how can I do so with what has occurred here? I am now going to remove to other lodgings.“

A couple of young women rushed up to two police-constables on duty outside the Royal Hotel, and said that a woman was being murdered. The two constables, Ronald Saw and Thomas Longhurst, immediately ran to the house indicated, and there found Ada Wilson lying in the passage, bleeding profusely from a fearful wound in the throat. Doctor Wheeler, from the Mile End road, was instantly sent for, who, after binding up the woman’s wounds, sent her to the London Hospital (Sophia Ward), Whitechapel, where Dr William Rawes ascertained that she was in a very critical condition.

Detective-Inspectors Wildey and Dillworth had charge of the case, and looked for the attacker. Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, April 1, 1888 issue reports that “subsequent enquiries … revealed the fact that a dispute arose between the woman and a man who she states is her husband … He was pursued for some distance by a neighbour … But the would-be murderer sharply turned a corner, and was soon lost in the labyrinth of streets.” No conviction was ever obtained. By the time Ada Wilson returned home from the hospital, on April 27 1888, all hope of finding her attacker – or of proving anything in a court of law – seemed to have disappeared.

Authorities at the time of the 1888 Whitechapel murders made no link between her attack and those murders and she never was questioned again.

Mrs Wilson

On 2 January 1889, a little over eight months after returning from the hospital, she married Samuel Wilson (she was already using his surname as many women did when lived with their common-law husband but weren’t legally married) at the registry office in Bristol. Samuel was older than Ada: he said that he was thirty-three on his marriage certificate. He described himself as an engine fitter. He abandoned Ada in or around February 1891; she returned to her parents’ house in time for the 1891 census, at which point the family resided at 78 Rounton Road, Bromley St Leonard. According to the enumerator’s records, Ada was married, twenty-seven years of age, and a “waterproof hand” – making waterproof clothing from India rubber. This profession – lightly skilled, but perhaps quick to be picked up once one had the job – perhaps suggested a degree of specialisation, but Ada was still firmly in the clothing-manufacturing trade.

Ada was attacked by her husband again on June 25 1891. He was drunk and asked her money, which she didn’t have, and he asked to live with Ada again, but the proposition failed to appeal to her. “Go to work,” she said, “and be different”. He was arrested. According to the Daily News, July 8, 1891 issue, “Samuel Wilson, 40, was indicted for maliciously wounding Ada Wilson, his wife” who was also injured with a knife on her neck. Her parents were also assaulted. When the case came to the Quarter Sessions at Clerkenwell on 7 July 1891, Samuel Wilson defended himself. The chairman Mr. Richard Loveland-Loveland, said that “the prisoner was a very dangerous character, and therefore he would be sentenced to six months’ imprisonment with hard labour.” She asked for a separation.

Little more is seen of Samuel, or Ada. Whether they ever took out their separation order is not known. In December 1898 Ada’s brother Henry had a daughter and named her Zoa Lavinia Elbury.

Later life

Zoa Ada Wilson died on August 24th 1952, aged 89 of a pneumonia, at the Whipps Cross Hospital in Leytonstone, London; she was the widow of engineer Samuel Wilson.

Aftermath

Authorities at the time of the murders made no link between her attacks and the Whitechapel murders. Samuel Wilson was never arrested for those crimes.

***

To know more:

Casebook website - Casebook Message Boards - Press report (from Casebook) - Press report (from Casebook) - Press report (from Casebook) - Biographic details from Casebook website - Wiki Casebook - Casebook Forums

JTR Forums

Jack The Ripper.org - Press reports (from Jack The Ripper.org)

Jack The Ripper Tour

The Jack The Ripper Tour

Jack The Ripper Map

Crimenes de Whitechapel (Spanish)

Jack El Destripador (Spanish)

Red Jack (Italian)

BEGG, Paul (2013): Jack The Ripper. The Facts.

BEGG, Paul & BENNETT, John (2014): The forgotten victims.

BEGG, Paul; FIDO, Martin & SKINNER, Keith (1996): The Jack The Ripper A – Z.

EDDLESTON, John J. (2001): Jack the Ripper: An Encyclopedia.

FIDO, Martin (1987, 1993): The Crimes, Detection and Death of Jack The Ripper.

HINTON, Bob (1998): From Hell… The Jack The Ripper Mystery.

JAKUBOWSKI, Maxim & BRAUND, Nathan (1999): The Mammoth Book of Jack The Ripper.

MATTHEWS, Rupert (2013): Jack the Ripper’s Street of Terror: Life during the reign of Victorian London’s most brutal killer.

RIPPER, Mark: Ada Wilson. Doubly Unfortunate, in Ripperologist no. 125, April 2012.

SCOTT, Christopher (2004): Jack the Ripper: A Cast of Thousands.

SUDGEN, Phillip (1994): The Complete History of Jack The Ripper.

#Ada Wilson#happy heavenly birthday#1863#1860s#timeline#violence against women#victorian women#women's history#Henry Edwin Elbury#Emma Fry#family#Charles Elbury#Henry Elbury#Rose Elbury#Emma Elbury#Thomas Elbury#Samuel Wilson#1870s#1871#1880s#1881

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Annie Millwood

Annie Millwood or Millward

Birth date: Ca. 1850 Attacked: February 25, 1888 Died (age): March 31, 1888 (38)

Complexion: ? Eyes colour: ? Hair colour: ? Height: ? Ocupation: ?

Clothes at the time of murder/discovery: ?

Resting place: ?

***

~ LIFE ~

Annie Millwood, or Millward, was 38 and the widow of a soldier named Richard Millwood in 1888. She was living in a doss at Spitalfields Chambers, 8 White’s Row, a narrow, dingy thoroughfare that ran parallel to Dorset Street. Frances Coles, who would be murdered in 1891, had been “an occasional lodger staying there a night at a time”, and “would sometimes (stay at the house) twice a week, then not come for a time.”

~ ASSAULT ~