Text

Writing Unlikeable Characters

(Don’t get me wrong, I love Bakugo. This is for the purpose of this post.)

So you want readers to dislike a character.

It’s actually… a bit more difficult than you think. There are people out there who will latch onto just about anything or anyone, and sometimes the antagonistic characters become the most liked.

One major difference to understand: an antagonist is not always unlikeable. And you know that whole “square is a rectangle” thing? Kind of applies here, too. Unlikeable characters are not always antagonists.

How do we achieve the unlikeable character?

When we decide that we don’t like someone in real life, often it’s because we decide that we dislike them more than we dislike them. Does that mean your character has no likeable qualities? Probably not. However, there are many more reasons to dislike them than to like them, and those dislike reasons carry weight.

“My character doesn’t like coffee,” is not really a serious reason for someone to dislike a character. Jokingly is possible, but in a serious way is less probable. “My character commits felonies for fun,” carries a bit more weight, but already I’m thinking of ways readers might enjoy that. (It’s the chaos of it all, I think.)

Let’s look at our friend Bakugo here. We’re supposed to dislike him more than we like him, but he has a large fanbase. People like his persistence and his confidence, though it was written and portrayed as viciousness and arrogance. Notice: those are very different words.

What I’ll say here is that it comes down to two things, and you can only really control one. How do you portray this unlikeable quality in a way that creates actual dislike?

Sometimes it doesn’t… matter.

People and readers are naturally empathetic; that’s just how we are. We’ll love anything that shows even a hint of redemption quality, which is why the antagonists of many movies, shows, and books are so freaking popular.

What you should prioritize when it comes to unlikeable characters is the way you write their worst qualities. But sometimes even that has little impact on the dislike factor! (It’s like one of those 5,000 piece puzzles.) We can write arrogance as, “I’ll do this better and faster than any of you losers could,” and you’ll get someone adoring their confidence and self-assurance.

As someone who’s tried to write several unlikeable antagonists, there’s always something. Basically! Think about the balance, how they’re written, and what you want your unlikeable character to be disliked for. If you want to write an asshole, then write an asshole.

There are just going to be people who call them a loveable asshole.

You can support or commission me for a story, edit, or advice post on Ko-Fi!

Join my Discord server!

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Writing Teenagers is Hard

In reading about teenagers, and formulating my own plans for writing characters in that age group, there are observations I’ve made - not only about the characters, but about the way readers react to them. Whenever I’ve looked at reviews for YA books, or even classics like The Catcher in the Rye which feature teen protagonists, the same complaints come up.

Adults read the books, and then become upset when the teenagers they’re reading about act like…well, teenagers. Obviously, saying all teens are irresponsible, immature, or selfish is incorrect. These are the obvious stereotypes. That being said, many teenagers do act in ways which, when compared with adults, come across as childish or self centered.

A review for The Catcher in the Rye noted the reader’s problems with the character, the main being that Holden spent too much time feeling sorry for himself. If I’m being honest though, that’s what teenagers do. If you think back to your high school days, you can probably name several times you, or your friends, did something stupid. Honourable mentions for my cohorts include walking on ice (while poking at it with a massive branch), breaking three chairs by seating several people on one at once, and being reprimanded for doggy piling a friend so that he started crawling around like a worm, shouting, “Get away, get away!” Suffice it to say, we were banned from that area (but that’s grade nine for you).

Katniss has been generally well received by audiences, but some still complained that she spent too much time “mooning” over Gale and Peeta when she should have been focused on a war. For my part, I would have been surprised if, after spending several hours with both of these guys, she didn’t develop some kind of feelings for them. War or not, going through life or death situations with a couple of guys would absolutely make a teenager fall for them.

My advice when writing teens would be to be authentic. Look back at your own high school years. Read some Young Adult novels, or books featuring characters of those age. Study your younger teen sibling if you have to. You don’t want a character who’s too whiny, or insufferably obnoxious, but a teen character has the right to be a little whiny because that’s realistic. If your character is selfless and level headed, it might be better to just write an adult. It’s about balance. Many readers will still complain about your character being “angsty” or “rude,” but it will add a level of realism to the work - especially as the character in question grows or matures with time.

I feel Harry Potter struck a good balance. Harry could be irresponsible; he worried about girls, and what Cho thought of him; he was jealous towards Cedric; he joined Ron in faking his way through his divination homework; he sassed Snape; and he otherwise acted like a teenage boy, occasionally being insensitive (such as by ignoring his partner at the Yule Ball), or lazy (letting Hermione help him and Ron with their homework when they didn’t pay attention). These traits were coupled with Harry’s better qualities (bravery and compassion) to create a character who was still flawed, but believable as a teenager. Certainly the fight between Harry and Ron, because of how immature it actually was, might have annoyed readers…but if the pair had simply made up, they would have been exhibiting an unusual amount, dare I say an unrealistic amount, of maturity for two fourteen year olds.

Some teens are mature for their age, and it’s valid to show that, but don’t feel like you have to write that character. Write what feels real for you.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

ok but dismantle the idea that you should finish your writing as quick as possible. some of my favourite books (stand-alones. with series i cannot choose) were written over the span of many years. the secret history was written in 10 years and the same with the song of achilles. all the light we cannot see took 9 years to write. almost every fan fiction takes the span of a few months to create and even then they aren’t perfect. lotr took 16 years for tolkien to compose. jkr took six years to write the philosophers stone. victor hugo wrote les mis in the space of 12 years. yes, many good books and stories are written over the course of a few months, but everyone’s different and it might take some more time for you. all im saying is that all these amazing books have changed and shaped literature and they weren’t written in a day. so take your time, it dosent matter if your work dosent turn out to be a masterpiece, you can perfect it day by day until you’re satisfied. don’t feel compelled to rush

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

The good plot twists aren't the ones that are wild left turns out of nowhere, they're the ones that make all the other little things that didn't quite add up before suddenly click

116K notes

·

View notes

Text

wilf (wip i’d like to finish)

66K notes

·

View notes

Text

The White Savior Trope

After I posted my anti-SJM explanation, a lot of people asked what I meant by the white savior trope, and even though the trope isn’t nearly as prevalent in fiction as it was say ten years ago, it’s still prevalent enough for it to be a problem. This gives me the perfect opportunity to explain what the trope is and isn’t, and help give some advice to not write in in your story!. So, first thing’s first. I fucking hate this trope. Like reading this trope in a book will make me chuck it across the room immediately. BURN IT WITH FIRE AND NEVER BRING IT BACK. This trope is one of the most problematic things in literature, media, and the real world. This trope is so harmful to BIPOC people everywhere, and it needs to just die. So, we’re going to kill it. Also, just for reference I will be describing the experience of black characters for this post just because I am black and feel comfortable speaking about it, but the white savior trope can happen with any non-white character not just black people!

What Is The Trope?/Why Is It Problematic?

The White Savior Trope (abbreviated as WST from this point onward) is a trope used in fiction in which a white character (normally the protagonist of the story) rescues people of cover from their suffering or when a person of color needlessly sacrifices themselves in order for the white protagonist to realize their full potential. The white savior is normally portrayed as a god-like messiah in the story and as I said earlier, they normally learn something about themselves and realize their full potential in the process of it. Why is this problematic? For several different reasons, but let me say that even though the WST is inherently racist and based in racist stereotypes, the trope itself was not created to be a racist thing. And, I would bet that half of the white authors who write these tropes don’t intend to be racist, they just genuinely don’t understand the background or problematic nature of it. For me, the trope is problematic because it says, non-white people are helpless and need a white person to come and save them from their cruel, savage destiny or non-white people are only good when they give their life to help a white person’s cause. That is 100% not true, and it’s extremely problematic because unfortunately a lot of people think like this.

Why do writers use this trope?

Truthfully, I don’t know. I think I as a black person immediately see this trope as problematic, but I can understand how some white people, especially those not exposed to non-white people, could see the trope as okay. I also think that Christianity has not helped this trope, and I’m Catholic. I can’t tell you how many people I know who have gone on mission trips to Africa and call it the most fulfilling experience of their life because they genuinely feel as though they completely changed the life of some poor little black kid in one one week visit. And, I’m really conflicted on how I feel about mission trips, but that’s a different post. Anyways, I also think that people use the WST to try and play on our natural human empathy, especially for white audiences. When we see someone different from us, our first instinct is to distrust them, but if we see someone who relates to us leading the mysterious people, we are much more likely to empathize them. That’s just biology. This is the problem with a lot of fiction still being written solely for white audiences. They tend to exclude the rest of the audience. If a somewhat racist person finishes a book or movie using the WST, they will feel good about themselves. They don’t hate non-white people. They loved this book where White Character swopped in, recked the culture of the Non-White Characters, and saved them since they’re so poor and helpless. After reading that same book or watching that same, Non-White people will probably end up feeling dehumanized or infantilized because they’ll feel as though they can only be saved by white people. I hope that makes sense!

Signs Of The WST In Fiction

The white person saves the black person multiple times

The black character is passive in the story

The black character has no personality other than supporting their white friend

the white character has to speak up for the ‘voiceless’ black people

the black character dies in order to motivate the white character

the white character becomes the leader of the black people for absolutely no reason at all

After one conversation with a black person, the white character has an instant redemption arc and is no longer racist

Remember, I just used black because I am black, but that can be exchanged for any non-white person. And, I’m sure there are a lot more signs than that, those are just the ones I see the most often in fiction.

How To Prevent It

I can already feel someone going to comment, “oh, so you think white people can’t be heroes?” No, I never said that, and if you got that from this post, then idk what to say fam. Obviously, white people can be heroes (but would it hurt our world to have more BIPOC heroes?). If your protagonist is white, make sure that any non-white characters around them are proactive and have their own personalities outside of the white protagonist. Their sole focus in life shouldn’t be helping the white person defeat evil. I would also make sure that the white protagonist does not become the face of the black power movement or whatever is happening in their story. Can they save the day? Of course! But, they shouldn’t have a population of only non-white people or somehow end the oppression of all of the non-white people in the land. If the white character starts out with any prejudices, please give them a genuine redemption arc. I actually like seeing characters unlearn racist ideology, kind of like Matthias in SoC, but that doesn’t happen overnight. No one changes their mind about anything in the blink of an eye, especially with something as serious and heavy as racism.

I hope that helped! Please DM or comment any questions!

271 notes

·

View notes

Text

and if you ever doubt yourself or your ability to write a good story please know that the world is lucky to have you and you deserve to tell the story you want to tell regardless of the skill you possess

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Injury Plots: The Immediate Treatment

(This post is an excerpt from Maim Your Characters, which is out this week!)

The Immediate Treatment phase of the injury plot is fairly straightforward: it is anything your characters do in the moments following an injury in order to feel better and to get to safety.

Oftentimes, this is instinctive. If someone is punched in the face hard enough to break the nose, for example, the first response is to shield the nose by protecting it with the hands. This is part and parcel of the Immediate Treatment – as is the tissue (or tampon) in the nostril to stop the bleeding.

But so are fighting back and running away.

In fact, according to Tactical Combat Casualty Care, the standard course for combat and SWAT medics, the first duty of a medic treating a downed comrade isn’t to treat the wounded. Their first duty is to return fire, because that’s how the group – and the medic themself – stays safe. So the Immediate Treatment of an injury may be to inflict further injuries to the opposing party!

So let’s look at a few examples of some Immediate Treatments, shall we?

Example: Misery

In Misery, Paul Sheldon’s Immediate Treatment is a simple act of rescue.

Annie Wilkes is driving down the road when she comes across Paul’s car. She checks on the driver and immediately recognizes him – she is his Number One Fan, after all. She hauls him out of the wreck – I believe the words sack of potatoes are used; Annie is a strong, sturdy woman – and she throws him in her truck, covers him in blankets, and drives him to her house.

Note that we don’t see any care addressed to his actual wounds in this case!

Example: Men of Honor

Carl Brashear’s Immediate Treatment is mostly overlooked in this film, which is, in my thinking, a mistake. (His story parallels that of another character – more about this later – and that character is short-shifted on his Immediate Treatment phase, too. It’s the one downfall of that injury arc.)

What we see is Carl lying on the deck of the ship, screaming in pain, as men swarm to come to him. His leg is mangled, bent at a horrible angle away from his body, and blood is pouring onto the deck. Someone calls for a medic (an inaccuracy; in the Navy it should have been corpsman.) But we cut away before we see anyone attempt to render first aid.

Example: The Empire Strikes Back

Luke Skywalker’s Immediate Treatment may be the most interesting of these three examples. Luke’s hand is gone, but the lightsaber did him one small favor on the way past: it cauterized his wound. Where a sword injury like this would be causing a severe bleed, Luke doesn’t have one.

Instead, we see Luke squirming on the catwalk to get away from his assailant – who reveals, in one of the most misquoted lines in movie history, that I am your father.

But we also see Luke protecting his stump. He keeps the stump of his missing hand tucked in the armpit of the other arm, trying desperately to keep it safe from further harm.

(Ultimately, Luke jumps off the edge of the catwalk and somehow winds up landing safely, because The Force. While this is a form of escape, and therefor falls into this section, it’s a little bit… hand-wavy.)

Homebrew Example: Billy Badbones

Billy’s bike goes down alright, and he’s trapped underneath.

For a moment it’s just Billy, with his arm and his leg all jacked up, his bike still trapping him. As the adrenaline fades, the pain ramps up and up. He’s been shot twice before, but nothing has hurt like this.

He looks up to find a concerned man standing over him. Despite Billy’s most fervent hope, the man asks the most useless question in history (and one of the most common):

“Are you okay?”

Billy is not okay.

He’s had a minute to think and take stock. His arm is a ruined mess, his leg is still pinned by the bike. There’s pain, not just from the road rash and the broken bones, but from the scorching-hot engine that’s lying on his leg. Cars have stopped in a jagged line, too close for comfort. He doesn’t like looking up at the axles underneath them.

“Get it off me,” he says. With help from two other motorists, the man manages to move the bike.

Billy tries to sit up, but he can’t move. He hears the wail of sirens in the distance.

When the medics arrive, they carefully move Billy to the stretcher and load him into the ambulance. One asks questions that seem inane to Billy, while the other begins to cut his clothing off. Their shears aren’t adequate for the thick biker’s leather, and sweat drips from the medic’s brow. Billy could swear. New leathers alone will cost him a thousand dollars he doesn’t have.

Then they’re splinting his leg, splinting his arm. Cold packs. An IV. Finally the merciful, beautiful moment when the medic pushes “a little something for the pain.”

It doesn’t fix everything, but it fixes enough to make it bearable.

So let’s unpack this a little bit. Billy gets some treatment from the motorists – they rescue him from being under the bike with its burning-hot engine. They also call for an ambulance (requesting help is still a treatment!), and from the medics he also receives care: splints, an IV, morphine.

Even though this all probably takes about half an hour, it’s still Immediate Treatment. It’s within the first few hours of the injury, but it’s also not entirely Definitive. Splints will do a little, but Billy will need more care before he’s back to being a road warrior.

This post is an excerpt from Maim Your Characters, out TODAY from Even Keel Press. If you’d like to read a 100-page sample of the book, [click here]. If you’d like to order a print copy, it’s available [via Amazon.com], and digital copies are available from [a slew of retailers].

xoxo, Aunt Scripty

227 notes

·

View notes

Text

Naming Chapters

I personally think naming chapters beyond the standard “1”/ “I”/“One” is an art we lose after middle school chapter books. And while I do think the minimal numbering fits certain books, I also think detailed chapter names fit others. So how do you name a chapter (and how do you know if it fits your story)?

1. Chapter names can be much longer and break the more strict nature of book titles

Chapter names can be a single word all the way up to a full sentence while still being manageable. They also don’t have to be as catchy or marketable as a book title. This means you have tons more freedom in the name. Which is really fun.

2. How to Name a Chapter

What kind of tone the chapter title evokes is important. It doesn’t have to match the overall tone, but it should mirror the one within the chapter. Just like the book title, you’re telling your readers what to expect. Here are some ways to find a chapter name (P.S. All the examples are made up):

Within the text

Ex. The sentence “The morning was awash with simple pleasures.” can turn into the title “Awash with Simple Pleasures”

Name of a side character who gets their moment in the chapter

Ex. “About Emily”

A question the reader and/or MC may have about their circumstances

Ex. “What Do You Do When the World Ends?”

A chapter’s motif

Ex. If the chapter revolves around a character getting the MC a pearl necklace, the title could be “Pearls”, “A Girl’s Best Friend”, etc.

An allusion

This could really be anything. Some of the most common allusions refer to Shakespeare, mythology, old songs, famous poems, and classic literary works. Of course, you could make an allusion to something niche (or otherwise unknown) that relates directly to the story.

Ex. “Et tu, Brute?” (referring to Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar) could a title after the reveal of a betrayal

An utterance

Anything your MC would think or say, given the opportunity to break the 4th wall, bridges the gap between character and reader a little. It’s not something they’ve said to anyone in the story. And it has an air of self-awareness.

Ex. “So This is Where We Are Now”, “This Wasn’t Supposed to Happen”

Foreshadowing

Use this sparingly and carefully, but you can plant clues and things similar in nature in the title

Ex. The chapter ends with the abrupt murder of a character using a coffee pot that was previously inconspicuous. The tile is “Coffee Pot”.

3. The “Other” Kind of Chapter (AKA The Part)

There are two main ways to split up a novel. The chapter and the part. Chapters are usually a given and can work concurrently with the story also being split into parts. If you read The Hunger Games, among many others, you’ve seen this in practice.

The parts of a novel are usually in 3s. This can (indirectly or inexplicitly) mark beginning/middle/end or childhood/adulthood/elderhood. Or it can mark more story-specific events, like The Hunger Games and its sequels. You mostly see this in sci-fi/fantasy novels, but they can go anywhere.

The titles of these parts are usually short and correlate with each other (similarly to how book titles in series can correlate).

Ex. “The Dawn”, “The Day”, “The Dusk”

Ex. “Spark”, “Flame”, “Wildfire”

Ex. “The Test”, “The Proof”, “The Job”

Ex. “4″, “16″, “25″

Where you place these divisions is up to you. It works best if it feels natural and fits in well with the pacing. You can plot your story around these parts, or add them in later. Either way, whether they work or not is going to be subjective and you might need beta readers/a critique partner to help you out.

4. So, is it right for my story?

That’s totally up to you and all I can really give you for an answer is my opinion. I think chapter titles are a given for stories with a comedic tone. There’s an easy sense of irreverence or goofiness that comes with it when used right.

Other stories can be tricky, though. I think unless your story is super serious (like a thriller), you can effectively use chapter titling. With serious stories, it might be a bit more tricky to maintain the stricter tone with title, but it’s accomplishable.

And of course, you don’t have to add titling. Sometimes the minimalistic nature of “One”/”I”/”1” fits a story better than any other title could.

If you feel so inclined to title your chapters, it can add a whole new layer of mechanics to better tell and represent your story that you can experiment with. And if you don’t feel inclined, don’t worry about it! It’s a personal choice, not something you’re missing out on. And isn’t that what your writing is? Your own style based on what you do and don’t add?

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Me: *sits down to write*

Me: *rereads old writing for several hours and doesn’t get any writing done*

Me:

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

When the scene isn’t turning out like it’s supposed to but at least you’re writing

44K notes

·

View notes

Text

I have come to the conclusion that redemption/not-actively-being-a-villain-anymore arcs basically come in 3 forms

1) the character starts off believing that they're doing the right thing and changes sides when they realize they aren't

2) the character starts off knowing and/or not caring that what they're doing is wrong but eventually comes to care about the morality of their actions and switches sides

3) the character knows and/or doesn't care that what they're doing is wrong but decides to act less immorally because it's pragmatic or more enjoyable — they still don't necessarily care about morality; doing the right (or less wrong) thing just happens to be more fun or convenient

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey guess what I actually have writing advice for once.

The use of tapes is an amazing literary technique. You can catch up characters on past events while also emotionally devastating them for things that happened when they weren't there. And you can also use a tape to remind a character of something they've said in the past, driving development.

Examples of tapes in media:

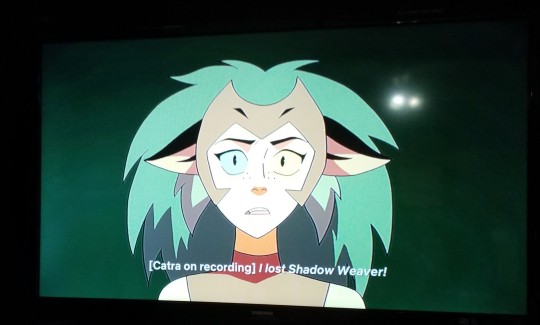

1. In SheRa 2018, season 2 is ended by Hordak's little Imp child recording Catra's, "I lost Shadow Weaver!", and playing it back to her. You can just see the utter fear on Catra's face as her secret as revealed:

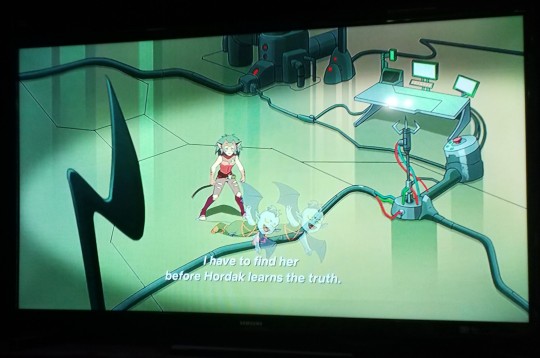

2. This technique is used again, to stimulate Catra's redemption arc:

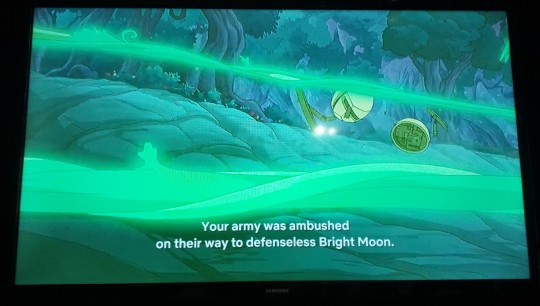

3. In Zootopia, the use of the carrot pen is set up as a joke, but ends up coming into play later to activate both the emotions of Judy and Nick:

Yes, I am using this in my AU! Here, have some sketches:

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

WRITING LOVABLE VILLAINS:

Villains. We hate to love them. They’re one of the most important characters in a story, and having an interesting, fleshed-out villain is much for fun than having a bland, flat one, which brings the question: How do we create lovable villains?

Well, what makes a lovable character? Their presence makes the story interesting. Their attributes and traits, everything about them makes the story feel real and makes the story interesting. They make it fun. So, a lovable villain must do the same.

Here are a few tips:

Give them a backstory, a reason for what they’re doing. Give them a cause, a motivator. Are they doing bad things for the right reason? Are they misunderstood?

Let them have fun. It’s fun to watch other people have fun. I mean, make them cool. Give them interesting traits and characteristics.

Another way to have the readers root for your villain, is to make them an underdog-someone thought to have little to no chance at winning. People love to side with the underdog; they want them to win, to prove everyone wrong.

Or, they’re a good opponent. They match the hero’s wits. They might be even better, even stronger. They’re smart, they’re competent. They’re dangerous.

They have a sense of humor. This one seems pretty self explanatory.

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think the most exciting thing about writing is that you never actually know what's going to happen next. even when you plot things, there are always plot twists you didn't see coming and lines of dialogue you didn't expect and you do genius things accidentally and it's like no matter how much you write, you never run out of ideas.

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS IS YOUR WRITING CHECKPOINT

Stop. Stop scrolling!

You should be WRITING

Open that damn document and write a couple lines of your book. Idc what or where.

Done? Okay, now reward yourself with a coffee and return to whatever you were doing.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Advice from a real life trans guy

Hello! I am here to talk to you about fan fiction and trans characters within it! If you want to make a character (or more!) trans, I give you the thumbs up of approval!

However, there are a few pet peeves that I want to point out. Some might be geared towards specific fandoms, so buckle up kiddos!

1. NAMES. I know I sound like a broken record, but it is IRRITATING beyond belief when I see a trans guy named Michael’s dead name be Michaela. NO!! That’s not how it works! Dead names are just that. DEAD. We want NOTHING to do with ‘em.

If it helps, imagine that someone close to you just died. It can be a pet, though that’s more painful, in my personal opinion. Imagine that you cannot, under ANY circumstances, remind people of this name. NO ONE likes this name.

Make it Trump, if you’re like me and want to trek to another country when you heard the name. Yucky man.

THAT’S how dead names work. No one wants to think of the name. It’s painful and it feels like your heart is shattering in your chest when you hear it.

TL;DR DON’T MAKE DEAD NAMES SIMILAR TO CHOSEN NAMES.

2. Whenever I read stories of a trans (male) character written by a straight, cis girl, there’s always a weird fascination with the chest of the male. Like male authors describing female breasts. Yeah. It’s that bad.

Do our chests annoy us, as trans guys? Yep, it irritates the bejeezus out of us. I jokingly mutter “begone, thots” when I bind. But, to all writers, don’t focus on it. A quick mention of a binder? Cool! A quick explanation of why the guy isn’t binding? Cool! Going on and on about how terrible and awful boobs are? Same, but not cool. Actually, quite dysphoria-inducing. Not fun.

3. Okay. This one trope I, admittedly, wrote for a while until one of my friends told me no.

TRANS. GUYS. DON’T. MENSTRUATE. EVERY. MONTH. ON. TESTOSTERONE.

Once you’re on T (testosterone) for a while, your period can go on long vacations. As in, after two years or so, it stops. Completely. Bye bye. There’s also a surgery that can stop it, but I don’t know the name.

When trans dudes do get their periods, its lighter than what another person would experience when not on T. It’s a pre-T guy’s dream.

4. Now, it’s 3 am and I am writing this is a fit of ungodly energy. But my fourth and final point is… (drum roll please)

NOT ALL TRANS GUYS ARE DEPRESSED AND/OR HAVE ANXIETY!!

Are those two disorders very widespread? Yup. Do they affect a lot of people? Absolutely. Does every single trans guy have one or the other or a hellish mixture of both? Nope.

Do you want to project? Go ahead! But it’s annoying to see generalizations in fandoms where “soft boy [enter name here] is depressed!! Protecc!!” And yikes.

Thanks for reading! If you want to add more (or, if any trans ladies or non-binary folks want to join in,) go right ahead!!

981 notes

·

View notes