Text

Poem for a Suicide

by Matthew Zapruder

The yellow flowers on the grave

make an arch, they lie

on a black stone that lies on the ground

like a black door that will always

remain closed down into the earth,

into it is etched the name

of a great poet who believed

he had nothing more to say,

he threw himself into literal water

and everyone has done their mourning

and been mourned over, and we all

went on with our shopping,

I stare at this photograph of that grave

and think you died like him,

like all the others,

and the yellow flowers

seem angry, they seem to want to refuse

to be placed anywhere but in a vase

next to the living, someday

all of us will have our names

etched where we cannot read them,

she who sealed her envelopes

full of poems about doubt with flowers

called it her “granite lip,” I want mine

to say Lucky Life, and what would

a perfect elegy do? place the flowers

back in the ground? take me

where I can watch him sit eternally

dreaming over his typewriter?

then, at last, will I finally unlearn

everything? and I admit that yes,

while I could never leave

everyone, here at last

I understand these yellow flowers,

the names, the black door

he held open

and you walked through.

0 notes

Text

Behind us lies a vast hinterland of lost histories: events, objects and lives which have passed unrecorded, or unwitnessed, or whose witnesses have been consumed. The perfect crime is, by definition, an untellable event. But it is not unimaginable. The historian must stop where the evidence gives out, but stories can be told beyond the evidential limits, of pasts too distant or too close. The ‘Once upon a time’ boar and the ‘Not yet’ boar can be hunted and pursued to the dark and silent spaces which are their lairs. A cave, a chamber, a silent apartment overlooking the Pont Mirabeau. Here is such a place (from Fadensonnen, 1968, translated by Joris).

Kleide die Worthöhlen aus

mit Pantherhäuten,

erweitere sie, fellhin und fellher

Line the word-caves

with panther-skins,

widen them, pelt-to and pelt-fro

These words have accreted meanings. The image of the panther appeared in a prose poem written by Celan in Bucharest in 1947. A German translation of the original Romanian (‘und der silberne Panther zerfleischte die Morgenröte, die auf mich lauerte’) offers a ‘silver panther’ and a punning ‘syllable panther’. Whether Celan’s Germanic mother tongue operates with sufficient insistence beneath the poem’s Romanian surface to allow this fleeting play on words to be claimed is questionable, although ‘cette belle saison de calembours’ was how Celan later characterised his time in Bucharest (‘what a wonderful time for puns’). Perhaps one can hear the distant echo of Celan’s between-ness and encavedness in Paris, his ‘entre’ and ‘antre’, in ‘Panther’. Here, it is the lair rather than its creature which is worded. Rilke’s famous panther, observed in the Jardin des Plantes in Paris in 1903, has bequeathed only his fur and the motion which seemed to animate him: ‘pelt-to and pelt-fro’. Some of the word-cave’s darkness is Rilke’s too, from ‘Schwarze Katze’.

aber da, an diesem schwarzen Felle

wird dein stärkstes Schauen aufgelöst

but there, in this dark pelt

Your most piercing gaze will be lost

Nothing and no one is visible here. The imperative mood conjures no dramatic situation. No one is asking anyone else to ‘widen’ the confines of the poem; the verb uncoils relations within the image rather than drawing them together. The particular space and time invoked in these lines is sprung between outward dissolution and inward collapse. The imperative has no tense. There isn’t anywhere this image can happen. There isn’t any ‘when’ either.

Rilke’s negatively capable leap into the dark pelt of the panther is, for Celan, the point of departure. Celan’s word-cave is built – impossibly – from the inside. Why should he choose to construct about himself a contracting darkness? Why should he write his poem at the very point of its collapse? The answer begins in a recognition that Celan chose neither the straitened confines of the word-cave nor the belated entanglement of its history. He was there, and then, of necessity.

— Lawrence Norfolk, “Thoughts about Boars and Paul Celan”

#Thoughts about Boars and Paul Celan#Lawrence Norfolk#prose#article#on Paul Celan#Kleide die Worthöhlen aus#Pierre Joris#Fadensonnen#Rainer Maria Rilker#by Paul Celan

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Behind us lies a vast hinterland of lost histories: events, objects and lives which have passed unrecorded, or unwitnessed, or whose witnesses have been consumed. The perfect crime is, by definition, an untellable event. But it is not unimaginable. The historian must stop where the evidence gives out, but stories can be told beyond the evidential limits, of pasts too distant or too close.

Lawrence Norfolk, “Thoughts about Boars and Paul Celan”

1 note

·

View note

Quote

If not the whole boar, at least his parts penetrated the text of the earlier poem: his tusks and taste for bitter nuts, weight and gait, his grunt. That poem swerves and accelerates. It jinks. Here the boar is long gone. Only his mark and a scattering of the earlier poem’s materials remain. The ‘bitter nut’ which was raked up and became a ‘wept’ stone reappears: the petrified tear is disinterred now as a ‘petrified blessing’. The ground in which the speaker must dig for it is a grave. The ‘four-finger-furrow’ derives from an image sometimes carved into headstones in Jewish cemeteries. The question of what this poem means is superseded by when it means it. We are very late on the scene.

Lawrence Norfolk, “Thoughts about Boars and Paul Celan”

#Thoughts about Boars and Paul Celan#Lawrence Norfolk#prose#article#on Paul Celan#Wege im Schatten Gebräch#Atemwende#In der Gestalt eines Ebers#Von Schwelle zu Schwelle

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Wherever this poem is going, it is going there with great insistence. Wherever it has come from it has come from there with great force. In transit from one to the other of these notional places, just as insistent and forceful as the poem which reaches between them, there is a seeming-boar. A dream-boar, or the furrow left by his passage: the shape of a boar. The poem happens within the animal even while describing him. But the boar is not here.

Lawrence Norfolk, “Thoughts about Boars and Paul Celan”

#Thoughts about Boars and Paul Celan#Lawrence Norfolk#prose#article#on Paul Celan#In der Gestalt eines Ebers#Von Schwelle zu Schwelle

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

a barbarous world deserves a brutal poetry.

Becca Rothfeld, “The Thousand Darknesses of Murderous Speech”

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

But a barbarous world deserves a brutal poetry. A language so mangled can never be wholly redeemed. Celan’s poems are not intended as consolations. The words he grafts onto each other are not intended to fuse. He once warned sternly that German “wants to locate even its ‘musicality’ in such a way that it has nothing in common with the ‘euphony’ which more or less blithely continued to sound alongside the greatest horrors.” In other words, German poetry is not supposed to be beautiful. We read on without hope and without revelation, digging and digging, knowing that we may never reach anything, that there may be nothing it is still possible for anyone to reach.

Becca Rothfeld, “The Thousand Darknesses of Murderous Speech”

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Celan never acknowledged that his poetry is demanding, sometimes even antagonistic. On the contrary, he repeated over and over that his work was essentially communicative in spirit. He likened a poem not only to a handshake but also to “a letter in a bottle thrown out to sea with the—surely not always strong—hope that it may somehow wash up somewhere, perhaps on a shoreline of the heart.” Many of his poems, both early and late, are addressed to an unidentified “you,” perhaps in virtue of his belief that any “instance of language” is “essentially dialogue” (and almost certainly in reference to the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber, who understood the self as an “I” existing only in relation to a “you”).

Becca Rothfeld, “The Thousand Darknesses of Murderous Speech”

#The Thousand Darknesses of Murderous Speech#prose#nonfiction#Becca Rothfeld#m#on Paul Celan#Martin Buber

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

And so on and on. The poem is devoid of punctuation. Nothing halts its lethal momentum, and it proceeds at a frantic clip. There is a whiff of oneiric narrative: a commandant “calls out play death more sweetly death is a master from Deutschland / he calls scrape those fiddles more darkly then as smoke you’ll rise in the air.” But centrally there is black milk in the mornings, at dawn and at night, at noon and in the eternal evenings, black milk and black milk again. By the end of “Deathfuge” the opening invocations of black milk jostle with other lines that have been echoed and re-echoed throughout, in particular the chilling “death is a master from Deutschland” (der Tod ist ein Meister aus Deutschland). In recordings of Celan reading the poem, his voice is suffused with an eerie and awful force, as if he is possessed.

Becca Rothfeld, “The Thousand Darknesses of Murderous Speech”

#The Thousand Darknesses of Murderous Speech#prose#nonfiction#Becca Rothfeld#m#Todesfuge#Paul Celan#on Paul Celan

1 note

·

View note

Link

0 notes

Text

Whitegray of

shafted, steep

feeling.

Landinward, hither

drifted sea oats blow

sand patterns over

the smoke of wellchants.

An ear, severed, listens.

An eye, cut in strips,

does justice to all this.

Strandhafer | sea oats: A psammophylic (sand-loving) species of grass in the Poaceae family, Leymus arenarius, is commonly known as sea lyme grass, or simply lyme grass. It could also be of the genus Uniola, that is, the species U. Paniculata, which we call sea oats. Both are strong grasses that consolidate seaside sand dunes, thus reducing land erosion. I prefer the literal translation “sea oats” here to “lyme grass,” for being closer to the original. See also the poems “Vom Anblick der Amseln” | “From beholding the blackbirds” and “Wir, die wie der Strandhafer Wahren” | “We who like the sea oats guard” (pp. 94 and 432) and their respective commentaries (pp. 497 and 619).

ein Ohr, abgetrennt | an ear, severed: Reference to Van Gogh. See also the poem “Mächte, Gewalten” | “Principalities, powers” (p. 204).

Ein Aug, in Streifen geschnitten | An eye, cut in strips: Brings to mind a core image in Buñuel’s film Un chien andalou.

— Paul Celan, translated and annotated by Pierre Joris, from Breathturn into Timestead: The Collected Later Poetry

#m#Weissgrau#Atemwende#Pierre Joris#breathturn into timestead: the collected later poetry#Un chien andalou#Luis Buñuel#botany#film#Vincent van Gogh#art#by Paul Celan#commentary

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weissgrau

von Paul Celan

Weissgrau aus-

geschachteten steilen

Gefühls.

Landeinwärts, hierher-

verwehter Strandhafer bläst

Sandmuster über

den Rauch von Brunnengesängen.

Ein Ohr, abgetrennt, lauscht.

Ein Aug, in Streifen geschnitten,

wird all dem gerecht.

1 note

·

View note

Text

In den Flüssen nördlich der Zukunft

werf ich das Netz aus, das du

zögernd beschwerst

mit von Steinen geschriebenen

Schatten.

In the rivers north of the future

I cast the net, which you

hesitantly weight

with shadows stones

wrote.

translated by Pierre Joris

October 16, 1963. The north is for Celan associated with ice and snow, and thus landscapes of death and desolation. Useful here may be to remember that the ur-mythologies the Nazi system misused were such Nordic settings and heroes, as Friedrich Nietzsche postulated, for example, in the opening paragraph of his Antichrist, worth quoting here in full (in H. L. Mencken’s translation):

Let us look each other in the face. We are Hyperboreans—we know well enough how remote our place is. “Neither by land nor by water will you find the road to the Hyperboreans”: even Pindar, in his day, knew that much about us. Beyond the North, beyond the ice, beyond death—our life, our happiness … We have discovered that happiness; we know the way; we got our knowledge of it from thousands of years in the labyrinth. Who else has found it?—The man of today?—“I don’t know either the way out or the way in; I am whatever doesn’t know either the way out or the way in”—so sighs the man of today … This is the sort of modernity that made us ill,—we sickened on lazy peace, cowardly compromise, the whole virtuous dirtiness of the modern Yea and Nay. This tolerance and largeur of the heart that “forgives” everything because it “understands” everything is a sirocco to us. Rather live amid the ice than among modern virtues and other such south-winds!… We were brave enough; we spared neither ourselves nor others; but we were a long time finding out where to direct our courage. We grew dismal; they called us fatalists. Our fate—it was the fulness, the tension, the storing up of powers. We thirsted for the lightnings and great deeds; we kept as far as possible from the happiness of the weakling, from “resignation” … There was thunder in our air; nature, as we embodied it, became overcast—for we had not yet found the way. The formula of our happiness: a Yea, a Nay, a straight line, a goal.

[Jean-Pierre] Lefebvre also points to Henri Michaux’s poem “Icebergs” and its hyperborean landscapes; the second stanza reads: “Icebergs, icebergs, cathedrals without religion of the eternal winter, wrapped in the glacial icecap of planet Earth.

— Paul Celan, translated and annotated by Pierre Joris, from Breathturn into Timestead: The Collected Later Poetry

#m#In den Flüssen#Pierre Joris#Atemwende#breathturn#breathturn into timestead: the collected later poetry#Friedrich Nietzsche#Antichrist#H. L. Mencken#Jean Pierre Lefebvre#North#Henri Michaux#translations#commentary

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

In den Flüssen

von Paul Celan

In den Flüssen nördlich der Zukunft

werf ich das Netz aus, das du

zögernd beschwerst

mit von Steinen geschriebenen

Schatten.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Todtnauberg

von Paul Celan

Arnika, Augentrost, der

Trunk aus dem Brunnen mit dem

Sternwürfel drauf,

in der

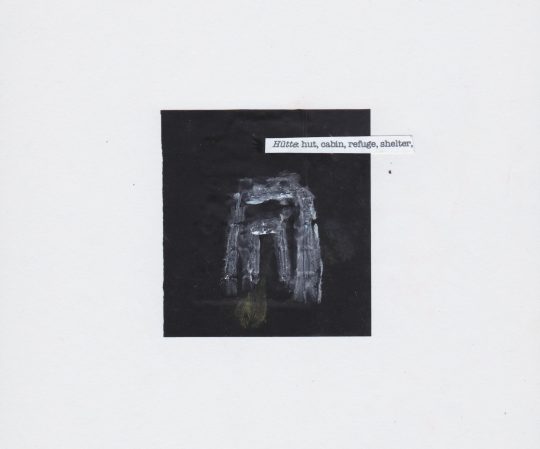

Hütte,

die in das Buch

– wessen Namen nahms auf

vor dem meinen? –,

die in dies Buch

geschriebene Zeile von

einer Hoffnung, heute,

auf eines Denkenden

kommendes

Wort

im Herzen,

Waldwasen, uneingeebnet,

Orchis und Orchis, einzeln,

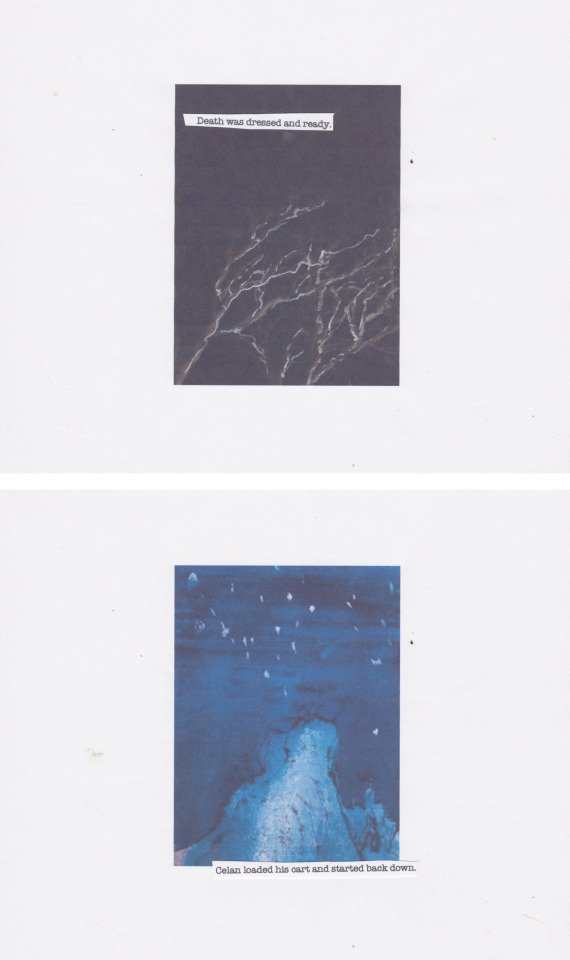

Krudes, später, im Fahren,

deutlich,

der uns fährt, der Mensch,

der’s mit anhört,

die halb-

beschrittenen Knüppel-

pfade im Hochmoor,

Feuchtes,

viel.

2 notes

·

View notes