Text

Fellow White Christians:

This is the Babe born in Bethlehem.

This is the Squirming Infant that Simeon called the Salvation of God.

This is the Child that challenged religious authorities in his Father’s house.

This is the Beloved Son that was baptized by John.

This is the Wedding Guest of Cana.

This is the Calmer of the sea.

This is the Multiplier of bread and fish.

This is the One who raised Lazarus.

This is the King riding on a donkey.

This is the Cleanser of the Temple.

This is the Teacher and Preacher of God’s perfect Law.

This is the Host of the Last Supper.

This is the Mourner weeping in the Garden.

This is the Scourged, the Bruised, and the Afflicted.

This is the Crucified Criminal on Golgotha’s mountaintop.

This is the Innocent Victim buried in an unfinished tomb.

This is the Destroyer of Hell.

This is the Man who defied death by rising from the dead.

This is the Resurrection and the Life.

This is Jesus, the Christ of God.

Notice, Church, that this very same Jesus is not wrapped in white skin and crowned with long golden locks. Notice how his skin is Brown, his hair is thick and curly, his non-blue eyes.

THIS is our salvation. We find life and life more abundantly in a Brown body, and for his sake we ought to do what we can and more to defend, protect, and empower bodies that are Brown and Black like his.

1 note

·

View note

Text

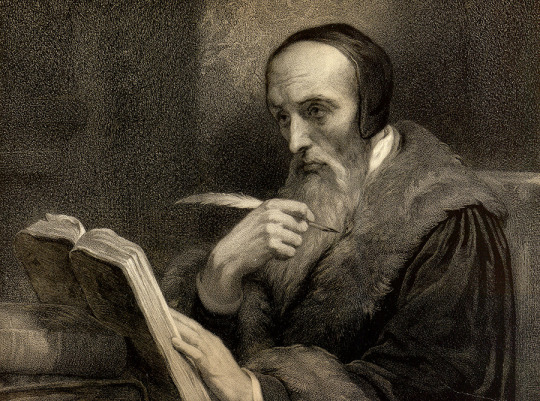

On this day 456 years ago, Protestant Reformer and Genevan statesman John Calvin went home to be with the Lord he sought to glorify and magnify.

For those of you who know me, you will know that I am tremendously indebted to this man. My theology is built upon the groundwork he laid out nearly 500 years ago and I worship in the liturgical tradition he and his followers built. His theological project brought new life to my Christian faith, and I would not be where I am or who I am without his presence in my life.

Sovereign and holy God, you brought John Calvin from a study of legal systems to understand the godliness of your divine laws as revealed in Scripture: Fill your Church with a like zeal to teach and preach your Word, that the whole world may come to know your Son Jesus Christ, the true Word and Wisdom; who with you and the Holy Spirit lives and reigns, ever one God, in glory everlasting. Amen.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

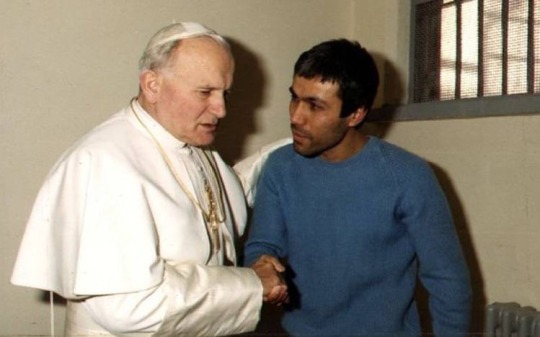

Pope John Paul ll with Mehmet Ali Ağca. Mehmet attempted to assassinate the Pope on the 13th of May in 1981

297 notes

·

View notes

Text

Study Spaces I miss 3/?: Scott Commons, University of Virginia Law School

The color scheme reminds me of the Gita.

103 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Deir Mar Lichaa (the Monastery of the Prophet Elisha) in the Qadisha Valley, Lebanon.

The Monastery of Elisha is a picturesque site of ancient Christian monasticism built upon the cliff wall of the Qadisha Valley. The Monastery is rich in history and is the birthplace of the Maronite Church’s eminent monastic order – the Lebanese Maronite Order. Several chapels were built into the valley’s natural caves, providing monks and hermits inhospitable conditions to live out a life of solitude. The last hermit of Mar Lichaa, Antonios Tarabay, passed away in 1998 and is now venerated by thousands of Maronites.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remember the time you thought you never could survive?

You did, and you can do it again.

43K notes

·

View notes

Text

Deborah:

Preacher of God

Deborah’s story is found in the fourth and fifth chapters of the book of Judges. Her account begins with the death of Ehud and the takeover of their land by Jabin, king of Canaan. Sisera, his military commander, is stationed in Harosheth Haggoyim. Conditions under Jabin’s reign were horrid, thus prompting the Israelites to “cry to the LORD for help” (Judges 4:3, New Revised Standard Version). The Lord responded to their outcry by equipping a woman—Deborah—to lead the charge against Jabin and Sisera.

Deborah is in a unique position in Israel. She is a judge: a military hero who, for her service, was entrusted with the powers of government during her lifetime (New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha: Expanded Edition, Revised Standard Version). The office of judge was established by Moses—by the recommendation of Jethro—during the wilderness journey. The book of Exodus records Jethro as saying:

“What you are doing is not good. You will surely wear yourself out, both you and these people with you. For the task is too heavy for you; you cannot do it alone. Now listen to me. I will give you counsel, and God be with you! You should represent the people before God, and you should bring their cases before God; teach them the statutes and instructions and make known to them the way they are to go and the things they are to do. You should also look for able men among all the people, men who fear God, are trustworthy, and hate dishonest gain; set such men over them as officers over thousands, hundreds, fifties, and tens. Let them sit as judges for the people at all times; let them bring every important case to you,but decide every minor case themselves. So it will be easier for you, and they will bear the burden with you. If you do this, and God so commands you, then you will be able to endure, and all these people will go to their home in peace.” (Exodus 18:17-23, New Revised Standard Version, emphasis my own)

Alongside being a military commander, Deborah is to preside over legal disputes that may arise within her community and the larger Israelite community. What is remarkable about this is the fact that she is a woman serving in a governmental and judicial capacity. Moses, under the influence of Jethro, originally established the office of judge to be a male-oriented position. “Get such men,” Jethro tells Moses. Yet Deborah defies this patriarchal expectation by serving as a judge.

Deborah is also a prophet: “At that time Deborah, a prophetess, wife of Lappidoth, was judging Israel” (Judges 4:4, New Revised Standard Version). As a prophet, Deborah represented God as an ambassador and a messenger (Storms). She oversees relating God’s word to God’s people, and when God’s people turn away from God’s word she is to critique and rebuke God’s people. She functions as a preacher, a teacher, and a pastor over Israel. All of Israel, including the men. Her authority as a prophet subjects men to her revelations.

The story of Deborah becomes even more important when examining the question of women’s ordination in Christian churches today. The Christian New Testament as a collection would not be recognized as both binding and authoritative on the whole Church until the Synod of Hippo in 393 CE (Metzger), so the early Christians drew on the scriptures of their forefathers and foremothers. A woman in the First Century would had both admired and viewed Deborah the Judge as a symbol of empowerment, and in her would have found justification for her own calling into ministry.

0 notes

Text

“‘Before I am delivered to them, let us sing a hymn to the Father and so go to meet what lies before us.’ So he commanded us to make a circle, holding one another’s hands, and he himself stood in the middle. He said, ‘Respond Amen to me.’”

Within Gnostic communities, the Lord’s Supper was performed in a similar fashion. The celebrant would stand in the center being circled by dancing and singing communicants. The celebrant would hold the Eucharistic elements and say:

“Fain would I be saved: And fain would I save.

Fain would I be released: And fain would I release.

Fain would I be pierced: And fain would I pierce.

Fain would I be borne: Fain would I bear.

Fain would I eat: Fain would I be eaten.

Fain would I hearken: Fain would I be heard.

Fain would I be cleansed. Fain would I cleanse.

I am Mind of all. Fain would I be known. Amen.”

Despite this book not being preserved in the canon (thanks be to God!), I think there’s beauty here that we should appreciate.

One: This text, being written in the early second century, provides an additional source for the historicity of Jesus’ existence, as it’s pulling from material unknown to the canonical authors.

Two: There’s something beautiful about the liturgy. It presents the Crucifixion of Jesus—presented in the canonical Gospels as a cruel, abhorrent, and grotesque event (and rightfully so)—as an occasion of joy. There’s singing and dancing and celebration before the Lord’s death.

We should have that same attitude. Christ Jesus laid in death’s strong bands, as Luther put it, and we should find joy among the macabre. For by His death He trampled death under His feet.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Two Adams:

Irenaeus’ Recapitulation Theory of the Atonement

Sin. This short, three-letter word is the foundation of Irenaeus’ theological framework of the atonement, known affectionately to us as the Recapitulation Theory. Sin is an infection that stains our soul and causes us to not only miss the mark, but to misdirect our footsteps from the path of God’s favor and causes us to stumble into the outer darkness of God’s condemnation. Sin has held our very nature ensnared, and it is not until the Incarnation of the Second Adam that the bars of this spiritual prison is broken. Irenaeus writes, “Redeeming us by [Christ’s] blood in accordance with His reasonable nature, He gave Himself a ransom for those who had been led into captivity” (Early Church Fathers, 385).

Sin is something foreign to human nature. Human beings were not created by the Father as inherently sinful; after all, human beings were made in the Imago Dei, God’s very own image. Human beings have free will, as Irenaeus would write in book four of his Against Heresies, “God made man a free [being] from the beginning, possessing his own power, even as he does his own soul, to obey the behests of God voluntarily, and not by compulsion of God. For there is no coercion with God, but a good will [towards us] is present with Him continually. And therefore does He give good counsel to all” (www.harvardicthus.org). Adam has complete sovereignty over his actions and chose on his own accord to backslide into the snares of the Accuser. This action changed the very fabric of his nature, and by extension changed ours since we are all children of the First Parents. As punishment, God had placed a limitation on the human life span. “For the wages of sin is death,” writes St. Paul (Romans 6:23, NRSV) and so we have reaped the harvest of Adam’s transgression by receiving the curse of death.

Yet God is loyal and true and does not abandon God’s creation. St. Paul writes, “But when the fullness of time had come, God sent his Son, born of a woman, born under the law, in order to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as children” (Galatians 4:4-5, NRSV). This verse is critical for understanding Irenaeus’ Recapitulation Theory because it lays out Who exactly Irenaeus thinks Jesus Christ is.

Christ is the bridge that gaps the massive canyon between the Creator and the creation while paradoxically being the Creator and a product of creation simultaneously. Irenaeus assumes that Christ is the Hypostatic Union: the hand of God presses against the hand of humanity with one not overpowering the other. For Irenaeus, God condescends from the divine threshold into the domain of God’s creation. In other words, divinity is lowered and humanity is lifted up, and where the two points meet is Jesus Christ. Irenaeus writes, “[The] Lord redeemed us . . . and poured out the Spirit of the Father to bring about the communion of God and man—bringing God down to man by [the working of] the Spirit, and raising man to God by His incarnation” (Early Church Fathers, 386).

God needs to be Incarnated into a physical body for the Recapitulation Theory of the Atonement to work. Flesh, blood, and bones were assumed by God to redeem our flesh, our blood, and our bones. In this physical body God adopted all the frailties of the body, including the ability to fall into sin. The Gospel of St. Matthew illustrates this point in its fourth chapter. Jesus, being in the wilderness, was tempted by the Tempter to abandon His ministry of saving the world and, in return, gain the world. Metaphorically, Satan was luring Jesus with forbidden fruit. Had Jesus forsaken His divine mission and taken up the Devil’s offer, Jesus would had rejected the One Who sent him. The Creator of the entire universe, wrapped in a body made of the same materials that ours are made from, would had paradoxically forsaken Himself and worshipped the embodiment of evil and the cause of sin. “Again, the devil took him to a very high mountain and showed him all the kingdoms of the world and their splendor; and he said to Him, ‘All these I will give You, if You will fall down and worship me’” (Matthew 4:8, NRSV). Jesus did not fall into this trap. Instead, in His humanity Christ obeyed and taught the Law perfectly.

In His submission to the Father, Christ went willingly to the cross and there died in the flesh. Irenaeus sees the obedience of the Son to the Father by being crucified as reversing the failures of creation itself. The cross replaces the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. The Corpus Christi hangs from the cross as the redeemed fruit. His enthroned glory reverses our shame. His victory reverses our defeat.

It is fitting that the Son of Man die in the flesh to reverse death itself. Three days after His death Jesus rose from the dead triumphant over death, the very thing we are cursed with. Jesus took on our full humanity and had the capacity to sin; instead, He went to the cross to reverse the fall and rose from death to redeem us from death. The complete restoration of our failures can be found in the God-Man alone, as Irenaeus writes, “Therefore He renews these things to Himself” (Early Church Fathers, 390). This renewal of humanity unleashes us from original sin and fills our lungs with new life.

0 notes

Text

The Apostle Paul and Slavery:

How the Epistle to Philemon is Liberationist

Out of all the books within the entire biblical corpus, Philemon tends to make me the most uncomfortable. Even Joshua, full of genocide and gore, pales in comparison to the level of discomfort I have when reading the third shortest book within the Bible. Upon the surface, the epistle to Philemon has Paul, an apostle of the Lord Jesus Christ, the apostle to the Gentiles (and therefore my apostle), commanding the slave Onesimus to return to his master Philemon. The American Church has used this shallow reading of the text to justify her complacency in the sin of racism and, in the American South, her direct support of the inhumane practice. What’s more, the shallow reading of the text is a valid reading. Unlike Joshua, which can be whisked away by being contextualized to the Babylonian Captivity, Philemon is firmly locked within the First Century and has a confirmed author and a confirmed audience.

Not content with the reading presented above, I chose Philemon as my exegetical text in order to liberate the epistle from the colonial eisegesis so that the epistle can speak freely from its context to ours. The findings were quite shocking; Philemon is not a text about bondage, but freedom, and Paul is subtly urging Philemon to release Onesimus from the yoke of slavery.

Before the pericope above is addressed, the context of the entire epistle is needed else the exegete risks divorcing the pericope from its historical context.

The epistle to Philemon was written after Paul was placed under house arrest in the city of Rome (Metzger et al, 1453). This information can be gathered from verse ten of the epistle: “I appeal to you for my son Onesimus, who became my son while I was in chains”. Since Paul is writing to Philemon after Onesimus was converted, and Onesimus was converted while Paul was imprisoned, it can be deducted that the letter was probably written between 61-63 CE (Metzger et al, 1453).

Philemon is the sister epistle to Colossians, as both epistles were sent to the faithful in Colossae. In fact, within the epistle to the Colossians, one can find a reference to our enslaved protagonist. “[Tychius] is coming with Onesimus, our faithful and dear brother, who is one of you. They will tell you everything that is happening here,” Paul writes (Colossians 4:9). In fact, the epistle to the Colossians could have also been intended for Philemon. Within the epistle to Philemon, Paul highlights that Philemon had a congregation that met regularly in his house. It is an important enough detail that Paul included it as part of the epistolary opening. “And to the church that meets in your home” is the last addressee (Philemon 2).

If that is true, then it could be concluded that Philemon is a leader within the early Church. As a house owner, he was more than likely a wealthy First Century man. And, as a wealthy person, Philemon was more than likely able to afford education, thereby making him literate. He probably the capacity to read and could expound on the Scriptures proclaimed. In addition, Church tradition makes Philemon a bishop of Gaza; Dorotheus of Tyre lists Philemon in his list of seventy apostles (www.orthodox.net).

In addition to owning his own house, Philemon was a slave master. This information can obviously be gleamed just by skimming the epistle that bears his name. His position as slave master is key to understanding the liberative nature of the epistle to Philemon because it places Christian social ethics on the line. Philemon has been wronged by Onesimus, as it was illegal for slaves to run away from their masters in the First Century and, if caught, the slave could be severely punished (Newsom et al, 362). How are Christians to respond to being wronged personally and being embarrassed socially?

Notice how Paul refers to Onesimus by a term of affection. Our runaway protagonist is called “my child” by the Apostle. Onesimus is called useful and the very heart of Paul. Paul is lifting Onesimus out of the categories of property and into a category of familial love. Onesimus is to be returned to Philemon, not as a slave; nay, something much more than a slave. Onesimus is to be viewed as a loving brother.

By making this categorical shift, Paul is placing Onesimus under the ethical protection of Christ’s Sermon on the Mount. Expounding on the Sixth Commandment, Jesus is recorded as saying, “But I say to you that if you are angry with a brother or sister, you will be liable to judgment; and if you insult a brother or sister, you will be liable to the council; and if you say, ‘You fool,’ you will be liable to the hell of fire. So when you are offering your gift at the altar, if you remember that your brother or sister has something against you, leave your gift there before the altar and go; first be reconciled to your brother or sister and then come and offer your gift. Come to terms quickly with your accuser while you are on the way to court with him, or your accuser may hand you over to the judge, and the judge to the guard, and you will be thrown into prison. Truly I tell you, you will never get out until you have paid the last penny” (Matthew 5:2-26, New Revised Standard Version). In a subtle way, Paul is placing boundaries around how Philemon can react and still be called a follower of the Way.

Paul was not trying to completely uproot slavery from society (Levine et al, 457). However, it could be argued that Paul expected Philemon to release Onesimus. Paul does hint that Philemon will go above and beyond what was expected of him; namely, that Paul knows Philemon will release Onesimus from the yoke of slavery because Paul “called Philemon out”, so to speak. Paul called into question Philemon’s character and reputation by saying he knows Philemon will go above and beyond what was “suggested” (more like rebuked) in his epistle.

This is furthered by Paul saying that any wrongdoing done by Onesimus was placed on Paul’s account. Paul was Philemon’s superior; it was Paul that brought Philemon to the Way, and, more than likely, it was Paul that ordered Philemon as a presbyter, or elder. It would be foolish to think that Philemon would try to do anything after Paul linked himself to Onesimus since Onesimus now has apostolic protection. Onesimus was untouchable; Philemon had no choice but to forgive his slave and set him free.

This is why this epistle is so important. This is why the early Church preserved this epistle and placed it within the cannon of the New Testament. Through our justification, through the atoning sacrifice of Christ Jesus, we are to grow in our sanctification. We are to bear fruit worthy of the Lord. And what does this fruit look like? It looks like defending those that cannot defend themselves. It looks like defying social norms. It looks like calling out oppression and sin. It looks like taking care of the least of these.

#new testament#apostle paul#philemon#onesimus#biblical studies#first century#roman society#history#slavery#jesuschrist

0 notes

Text

The Meal of the Bull and the Supper of the Lamb:

Exploring the Similarities and Differences Between the Mithraic Mysteries and the Christian Eucharist

Introduction

“Which the wicked devils have imitated in the mysteries of Mithras, commanding the same thing to be done” (www.logoslibrary.org). These are the words penned by Justin Martyr, a Christian saint who lived between 100-165 CE. Martyr, a Christian apologist, noted the similarity between the Eucharist and the Mithraic Mysteries and used these words to write them off, so to speak. The Devil is in the details here, subverting the central event in the life of the Church by replacing it with a demon instead of the glorified and risen Christ.

While Martyr’s language is pointed, to say the least, he is on to something. The nature between the two rites is extremely similar. Both took place in the context of a communal meal, both involved bread and wine, and both connected the meal with sacrifice. What’s more, the two religions spring out of the First-Century Mediterranean world; more specifically, both are rooted within a Roman context.

Ultimately, though, the similarities stop there. The Christian Church did not copy the rites of Mithraism, nor did the cult of Mithras steal the Church’s liturgy in order to compete with the Church for proselytes. The central rites of Mithraism and Christianity, despite similar in form and function, differ in content, purpose, and propitiation and therefore cannot be equated.

The Mithraic Mysteries

The Mithraic Mysteries can be found in a document called the Great Magical Papyrus of Paris. It is important to note that this document comes from the Fourth Century CE, but the liturgy it contains is possibly traced back to the Second Century CE (Meyer, 182). The document more than likely comes from Egypt, a region that hardly had any Mithraic activity (Alvar, 532).

After the worshippers gathered in their Mithraea, an underground sanctuary that is rectangular in shape and is centered around a pedestal-shaped altar located in an apse in the back of the sanctuary, the ceremony begins.

The celebrant opens with a litany-like prayer that ascends the soul out of the body and into the spiritual plane, and while the celebrant is listing the deities being invoked, the communicants would draw onomatopoeic phrases from their mouths, such as hisses or hums or stringing the Greek vowels together (Meyer, 183). What is interesting about the opening is that it is summoning the four elements—wind (spirit is what Meyer has, but pneuma can be translated as breath or air), fire, water, and earth. After invoking the four elements, the celebrant asks the elements to be “[given] over to immortal birth and . . . undying nature, so that after the present need which is pressing [the celebrant] sorely, [he] may gaze upon the immortal spirit, with the immortal water, with the most steadfast air, that [he] may be born again in thought, that the sacred spirit may breathe in [him], that [he] may wonder at the sacred fire, that [the celebrant] may gaze upon the unfathomable, awesome water of the dawn, and the vivifying and encircling ether may hear [him]” (Meyer, 183-84).

After invoking the primordial elements, the celebrant summons what are called the Lower Powers of the Air and, at this point, will be completely cut off from reality. Now the celebrant slips into an ecstatic state, “[not] hear[ing anything from] either humanity or of any other living thing” (Meyer, 184). These beings that are summoned during this trance are lower deities or angelic beings that have a more direct role in human affairs. What is strange is that the text has these beings “rushing” towards the congregation, but after the celebrant says the incantation of silence and asks for protection from the “symbol of the living, incorruptible god”, the beings stop and go about their business (Meyer, 185).

At that moment the sun disk opens and Aion, the son of the virgin Kore and a Hellenistic god of time, appears. What is fascinating about this figure is that the responsory of the congregation uses a version of the Tetragrammaton, or the unspeakable name of the Hebrew God: Iao. The language suggests that Aion is, in fact, Yahweh, and it appears that Mithraism held Yahweh within its belief system. What is interesting is Yahweh is not the highest deity in the pantheon (Meyer, 186).

While Aion is present, the celebrant invokes “the immortal names” of the “seven gods of the universe” in order to pass over from the realm of fire to the doorway of the realm of the gods. The celebrant enters, greets the god Helios and the seven goddesses of fate, and bids the seven pole gods to sit. And then, at last, the celebrant stands before the god Mithras (Meyer, 186-188).

Mithras is described as a “god immensely great, with a bright appearance, youthful, golden-haired, wearing a white tunic, a golden crown, and trousers, and holding in his shoulder a golden right shoulder of a young bull” (Meyer, 189). The last descriptor is particularly important, because the Mithraic Mysteries invite the participants to partake of Mithras’ sacrifice of the bull. It is the central act of the entire religion, for when the congregants partake of the sacred meal, they are eating the sacrificed flesh and drinking the sacrificed blood of the bull (Beck, 27-28).

The celebrant then invites Mithras to inhabit his soul, and after uttering a revelation from Mithras, the celebrant initiates the sacred meal of wine and cake made from lotus pulp and honey (Meyer, 190).

The Christian Eucharist

The Christian Eucharist, like the Mithraic Mysteries, was historically connected to an actual meal. The author of Jude, while critiquing antinomians, writes, “These are blemishes on your love-feasts, while they feast with you without fear, feeding themselves” (Jude 1:12, New Revised Standard Version). And, like the Mithraic Mysteries, the Eucharist involves bread and wine.

However, the liturgy is vastly different than that of the Mithraic Mysteries. The Mithraic Mysteries involve spiritual ecstasy and transcending physicality in order to become spiritually united with Mithras. The Christian Eucharist is nothing like that. In the New Testament, the Apostle Paul writes, “For I received from the Lord what I also handed on to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took a loaf of bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and said, ‘This is my body that is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.’ In the same way he took the cup also, after supper, saying, ‘This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in rememberence of me.’ For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes” (1 Corinthians 11:23-26, New Revised Standard Version). The Eucharist does not involve any sort of physical transcendence. Rather, it celebrates physicality; in some circumstance—be it corporeally, spiritually, or memorially—Jesus becomes present. There is no disconnecting from the body or from reality in the Eucharist.

Also, examining the 1 Corinthians text, the focus between the two rites is vastly different. The Mithraic Mysteries are focused on the slaughter of the bull by the hands of Mithras. The Eucharist is focused on an entirely different sacrifice, that of Jesus himself. And the Eucharist conveys a different kind of sacrifice than that of the Mithraic Mysteries; while the Mysteries are concerned with the slaughter of a bull for sport, the Eucharist presents Christ as being given over to death for sin.

The person to whom the oblation is made differs between Mithraism and Christianity. In the Mithraic Mysteries, Iao—Yahweh—is the gatekeeper for the doorway into the realm of the gods. Within the Christian context, Yahweh the Father is who the perfect and complete sacrifice of Christ the Son is offered. It is God doing the sacrificing, and it is God who the sacrifice is pleasing. The Eucharist is simply the participation—be it corporeally, spiritually, or metaphorically—of Christ’s once and for all sacrifice.

The concept of time ought to be explored. Between the two liturgies, the perpetuation of the rite differs. Eschatologically speaking, the Mithraic Mysteries continue without any restraint in time. For the Christian Eucharist, the Supper is only a temporary rite until Jesus returns. “For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes,” Paul writes to the church in Corinth. The celebration of the Eucharist stops once the eschaton—the end of time—is fully realized.

The social contexts in which these liturgies would be celebrated is important note. The Mithraic Mysteries would have been celebrated on the behalf of and for the Roman upper class. It was a cult that had a massive following among the Roman soldiers and noblemen. Christianity, on the other hand, appealed to the working class and to the poor; early Christians were known for offering material and financial support to the outcasts of society, as well as allowed women to partake of the central rites of the faith. The cult of Mithras was exclusionary; only men were allowed to worship Mithras.

Conclusion

The Mithraic Mysteries and the Christian Eucharist do have things in common. Both are connected to Yahweh, involve some sort of propitiation, and feast upon flesh and blood. But the two liturgical meals cannot be seen as plagiarisms of each other. The theologies that both present are too distinct, and the audiences are too vastly different.

#mithraism#biblical studies#new testament#history#first-century#apostle paul#liturgy#eucharist#yahweh#jesuschrist#earlychristianity

2 notes

·

View notes