Text

On Walking Away or ‘I Guess It’s Fuck-This-Shit O’Clock’

Some stories need time before they can be told. In December 2018, I wrote a blog post that I never published. Here’s how it began:

Dear Nobody,

Sometimes you instinctively know when it’s time to leave—a place, a job, a relationship, anything, which isn’t working for you anymore. The triggers may come in different shapes and sizes. The decision to leave might be an impulsive one—maybe you were walking down the same street you’ve lived on since you were born, when you suddenly stopped in your tracks and realized that you’d like nothing more than to move to New Zealand. Or it could take weeks and years to arrive at that point, endlessly agonizing over pros and cons and what-ifs—maybe you know that you’re with the wrong person, but you wonder what would happen if you broke up and didn’t ever find the ‘right’ person. After many sleepless nights, you finally decide to take that chance. I like to refer to this decision point as fuck-this-shit o’clock. FTS o’clock is the point of no return. You can feel it in your bones. Every cell in your body will suddenly awaken to this new reality, where you know beyond all doubt that you cannot stay a second longer.

'It is so hard to leave—until you leave. And then it is the easiest goddamned thing in the world.' John Green

My internal clock struck FTS in October this year. It had been over two and a half years since I landed what I thought was my dream job, with a remarkable organization that does wildlife research and conservation in India.

There are parts of the original post that I do not wish to share, and this was, perhaps, the reason I never published this even back then. I love the organization and to date maintain a fierce sense of loyalty to the people and the work (I mean, I still end up saying ‘we’ when I talk about the ongoing projects). Anyway, I felt stuck in a rut and I felt more miserable the longer I stayed.

There were, however, good days too—days when I felt fortunate to be where I was and to be doing what I did. But those days were few and far between, and the rest of the time I felt like I was stuck in an elaborate nightmare that I couldn’t wake up from. I discovered the hard way that one of the occupational hazards of the job was that I would lose my fucking mind. After that, the beauty of the landscape, the wildlife, the fresh air and clean water ceased to matter as much. And yet, the decision to quit was a long-drawn process, a slow and silent build-up of discontent, disillusionment, and the sense that the job wasn’t quite the right fit for me. The feeling only grew with time, as inevitably as barnacles on a sunken ship. I took time off in August to feel better and clear my head, but returned worse off than before [I also lost a dear friend that month, which put things in perspective]. I was, to put it simply, a proper mess. I started seeing a therapist after that, paying a small fortune every month, to regain some sense of control over my life (even if all control is ultimately an illusion). Two months into therapy, it became clear to me that I had to quit—the personal cost (not to mention the financial cost, i.e., therapy) of staying was too high. The bells were ringin’ and there was no mistaking the time—it was fuck-this-shit o’clock. And I finally bridged the gap between conviction and action.

“Why not pause for an eternity when there is reason to pause? Why stay an extra minute when there is reason to leave?” asks a character in a book by Anuradha Roy. It isn’t uncommon for PhD students, during the course of their doctoral degree, to figure out what it is they really want to do. More often than not, it isn’t academia. The biggest reward from my current job was the realization that perhaps I should be doing something else.

[NB: I did go and do something else. I took a break to do another master’s and then landed my current job that I genuinely enjoy. But most often, the ability to walk away requires some level of privilege.]

Reading the original unpublished post some three years later now, I know that I wasn’t just talking about the job. It was also about the six-year-long relationship that I was in. It’s as clear as day to me now. Funny how our own minds deceive us. Yet, despite the self-deception, I knew in my bones that it was time to walk away. A convenient excuse / scapegoat at the time was another person whom I’d met and was somewhat interested in [it was nothing really, didn’t even last a few unremarkable weeks, but it was exactly what I needed]. I wouldn’t realize until six months after my long-term partner and I broke up that I had, in fact, been extremely unhappy for a long, long time. We did talk about it then, but it was too little, too late. The clock had struck FTS aeons before the fact and I was tired of pretending that I was happy, especially to myself. Or as my favourite queer abstract artist, Brit, put it:

“One day, the long and tangled story of reasons to go and reasons to stay loosened. I left because I wanted to. The evidence no longer mattered. There was no one who would see it all and simply rule in my favor. There was just me, and what I knew of myself, and what was in my power to do.“

In the end, I’m glad things worked out the way they did. Walking away from the job and the relationship were some of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do, but there was a whole world of genuine happiness to gain. I could finally stop shrinking myself to fit the wrong moulds and expand until I found the shapes that suited me best. All I had to do was pay attention to my inner clock.

Love,

D

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Medieval Torture Methods or ‘How Contact Lenses Scarred Me for Life’

Dear Nobody,

If the technology had existed back then, I’m pretty sure that attempting to wear contact lenses for the first time would have been a form of medieval torture. Once you do manage to learn how to put them in (if at all), there are a zillion things to remember. Always wash your hands with soap and dry them before touching the lenses, remove the lenses before going to bed, replace the cleaning solution in the lens case every 24 hours, replace the lenses after two/four weeks, replace the lens case every three months. Failure to do any of these could lead to severe eye infection (from bacteria and other microorganisms) and loss of vision. Why then would I—in the third decade of my life, after having worn glasses since I was seven years old—choose to put myself through it? As with most things in my life, the answer is simple: Ultimate frisbee.

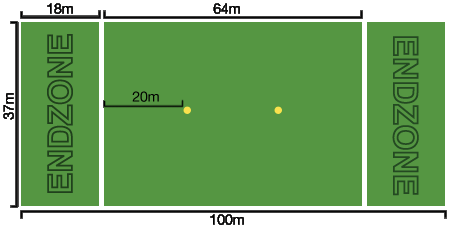

So, here’s the thing. I’m short-sighted and, as I mentioned already, have been bespectacled for most of my life. I’m meant to wear them all the time, but for several years now, I only use my glasses when I’m reading or writing. Which means that for the rest of the time, I can’t actually see very well. For the past six years, I’ve been playing Ultimate—a fast-paced, dynamic team sport—by guessing at where the disc is and who my teammates are from the colour of their jerseys. At the start of a defensive point, when we’re lined up at the opposite end of the field and across from the rival team, I can just about make out seven human-sized blurry shapes in the distance.

“Whom do you want to mark?” my teammates might ask.

“Uh…” I would say as I squint.

“Ok, you take L6,” they might say, to put me out of my misery. L6—the sixth player from the left. I can work with that. I just have to focus on that shape until the point begins and I’m able to get close enough to actually see who it is I’m supposed to be marking.

Ultimate frisbee field. Source: nicebristols.com (See how I didn’t miss an opportunity to impart frisbee knowledge?)

Wouldn’t my game improve if I just wore my glasses? Probably. But it can prove quite dangerous while playing (collisions might mean broken glasses and/or serious injuries to the eye), and is inconvenient to boot (they tend to fog up). This is where contact lenses come into the picture. After being put off by a failed attempt over a decade ago, I decided to give them another shot. I reckoned it may change my Ultimate life for the better.

Off to my ophthalmologist I went, filled with newfound optimism. She was held up with a surgery the evening my customised lenses (since I have both spherical and cylindrical power) arrived at the clinic, but said that her assistants would teach me how to insert them. I was quite nervous, but they reassured me. “Oh, don’t worry. It’s really easy! It only takes a second after you’ve learnt how to do it.”

We washed our hands with soap and water. Careful not to touch anything, I sat myself in front of a mirror that was placed on a table. “I’ll put the lenses in for you the first time, and after that, you can give it a try,” one of them said. Let’s call her Ugh. And so, Ugh proceeded to pry the lids of my right eye open, while the other assistant—let’s call her Sympathy—shone a torch directly into it. It was a Clockwork Orange moment. I panicked.

“You’re closing your eyes!” exclaimed Ugh.

“You’re literally preventing me from doing that,” I moaned through my mask (we all had masks on the whole time).

“Your eyes are too watery,” she complained, as tears streamed down my face and were absorbed by the mask. “Here, dab them with this tissue.”

By now, my nose had started to run as well, and I had to go wash my hands every time I blew into a tissue. I could already tell that we would be here for a while.

20 minutes later, Ugh still hadn’t managed to put in a single lens. “This isn’t going to work,” she declared. Sympathy, the other assistant, was then relieved from torch shining duty and recruited to keep my eyelids propped open, as Ugh poured all of her energy into jabbing my eye.

“Open your eyes!” she commanded. “Stop blinking!”

This reflex was the product of millions of years of evolution, how was I supposed to kick it in half an hour? I kept that thought to myself, not wanting to antagonize her further.

After what seemed like an eternity, Ugh finally succeeded in her mission. I was instructed to go wait outside, while my poor cornea got used to having a circular bit of plastic stuck to it. And then it was time for the real test. When I returned to my seat in front of the mirror, I was asked to remove the lenses and then reinsert them. The former involves holding your eyelids wide open, while pinching the contact lens between your thumb and forefinger. Following the sore abuse earlier, this part didn’t seem so hard. But re-inserting the lens? All by myself? Oh boy…

The first step was learning how to clean the lens with a few drops of multi-purpose solution in the palm of my non-dominant hand. Next, you place it on the dry part of the palm, and pick it up gently, such that the lens maintains its convex shape and is balanced on your fingertip. Sounds easy enough, right? What happened instead is that I pushed the lens around my palm, attempting to pick it up. When I managed to do it after many tries, the shape of the lens had become distorted, so I had to add a few more drops of lens solution and start all over again.

Ugh was not having it. “Your fingertips are too narrow!” she said. Dafuq was I supposed I do about that? Thankfully, I managed to pick up the lens again before I could melt under her glare. But as if on cue, my eyes started to tear up in anticipation of what lay ahead, and soon enough, my rebellious nose started running like water. I’ve never been more grateful for a face mask. I had my hands full—holding the lens up with one, and pulling my lower eyelid down with the other, while Ugh very helpfully manhandled the upper eyelid—and so, I had no choice but to cringe internally as my mask became damper and damper from absorbing tears and snot. It wasn’t my proudest moment as an adult.

I would like to think that I might have been more successful with the lens if I hadn’t been preoccupied with my bodily fluids. As it stood, I was having even more trouble than Ugh had had. I would touch the lens to my cornea, but instead of sticking, it would fall on to the table or the convex shape of the lens would get inverted.

“Don’t let the lenses drop to the ground,” Ugh warned. “You’ll have to get rid of them and order a new pair. But it’s ok if it falls on a sanitized table, you just have to rinse with the solution before putting it in again.”

“What happens if it falls in the sink?” I asked, genuinely concerned. Apparently, asking questions only served to rile her up some more, so I kept going. “And how do people cry with lenses on? And can you rub your eyes when they’re in? I tend to rub them a lot. What happens if an insect flies into my eye?”

I braced myself for a second attempt. This time, I actually managed to keep my eyes open AND get the lens to stick. “Look up, now look right,” Ugh said. “No, right, right, right.”

“I AM looking to the right.”

“Left, left, left.”

The ordeal took the rest of the hour. I put the lenses in, took them out, and put them back in three times. It didn’t get any easier. Besides, would I always need someone to peel back my upper eyelid? Before leaving the clinic, I took out the lenses one last time and stuck them in the case (you have to be careful not to interchange the right and left lenses when you return them to the lens case if your power varies, like mine). My eyes ached. I haven’t had my eyes gouged out, but I imagined this was how it would feel after.

Now, if an insect so much as flutters anywhere within my range of vision, I squeeze my eyes tightly shut and keel over, whimpering softly. I never again want to have anything in my eye. We just aren’t meant to routinely prod our corneas, you know. I think I’ll continue playing Ultimate with my compromised vision.

Love,

D

P.S. Somewhat unsurprisingly, I did mix up the lenses while putting them in the case. This meant visiting the clinic again the following day. The doctor was in this time, and she taught me how to insert the lenses again. It went much smoother. In fact, it took her under five seconds to put them in. And with her supervision, I was able to do it far more easily than the previous evening with her assistants.

0 notes

Text

On Human Connections or ‘Why You Should Let Your Kids Talk to Strangers’

Dear Nobody,

If you’re a parent, I implore you to teach your kids that not all strangers are to be feared. In December 2012, I spent the night at a hotel room in Frankurt with a stranger I met at the Charles de Gaulle airport, Paris. My parents, like all good parents, had drilled it into my head from an early age that strangers weren’t to be trusted or spoken to. If only they knew at the time! I later sent my sister a Whatsapp message after connecting to the WiFi in the lobby. “Don’t panic,” I said, “But I met this French girl and we’re sharing a hotel room because we’re on the same flight to Chennai tomorrow morning.” “Are you crazy?” came her frantic reply, “What if she steals your passport and wallet and leaves you stranded in Germany? You don’t even know her!” While this thought had briefly flitted through my mind, I’d spoken to enough strangers all my life (I’m sorry, dad!) to know that it would be alright. It turned out to be one of the most memorable experiences of my trip around the sun so far.

As Anne and I had stood in line at the check-in counter in Paris, she turned around to ask if I was going to Chennai. “Do you also have a 10-hour layover in Frankfurt?” she asked. I did, so we grabbed lunch together before boarding the flight, having decided to meet up once we landed. When we managed to find each other amidst the mass of people in the arrivals hall, we were all set to find an unoccupied corner to bed down for the night with our respective backpacks. Except that we crossed a counter for reservations at hotels close to the airport and realized that if we shared a room, we could save ourselves the stiff neck and the back ache that follow from slouching/sleeping on airport floors, at an affordable price… with breakfast included! We took the room.

Anne was one of those people whom you instantly become friends with. We talked the entire taxi ride to the hotel and then after we checked into our room. We talked while she sat on a cosy chair and I on the carpeted floor, wolfing down our takeaway dinner from the airport. We shared music and movies (Noir Désir is still one of my favourite bands!). We watched a film. We talked some more. She showed me videos of her performing music. When we left for the airport the next morning (passport and wallet intact), after getting only two hours of sleep, you’d have thought we had known each other for years! It’s not often that you make human connections like that, but it never would have happened if I hadn’t defied my upbringing.

An unexpected new friend in Frankfurt

I have tons of stories about strangers who’ve turned into friends, and each of them is special because they capture a moment of vulnerability in which two people decide to take a chance. When I first discovered the Internet in school, I worried my family by talking to plenty of strangers I met online. They strictly forbade me from doing it, so I obviously did what any kid would do – I not only chatted with strangers on the sly, I even met up with a few of them. A whole bunch of people who are my good friends now are those I met online over a decade ago in a few chatrooms and on social media websites (you know who you are – thank you for not being serial killers or lunatics).

I don’t know what it is about talking to strangers. There’s a certain allure to them, in the endless possibilities they offer, in the potential to forge a new relationship, a chance to drop your mask and be yourself. But at the heart of these interactions always lies one implicit factor – trust. I only truly understood this when I started Couchsurfing during my two years in Europe. Have you heard of CS? It’s a social networking website for travellers, essentially built on a two-way trust system between local hosts and travellers, both of whom are complete strangers. Backpacking on a shoestring budget became much easier and way more fun when I stayed with generous local hosts whom I met on CS (their tag line is now ‘Travel like a local’). I hosted travellers when I could or showed them around/hung out with them if I couldn’t, which was my way of giving back to the community. “How can you allow a stranger into your home based on a profile and a few messages you exchange?” my sister, ever the voice of reason, had asked. “Well do whatever you want while you’re in Europe, but when/if you live with me again, I’m not having any of this.” (She will vehemently disagree with my version of things, of course.)

But you know, thanks to CS, my friends Pam and Dom got married a few days ago in Mexico. I take full credit for introducing them to each other! Pam was my masters coursemate, while Dom was a Couchsurfer I was hosting for a few days in England, while he looked for a place to rent. When he was staying with me, I took him along to Pam’s birthday party, where they met for the first time, and the rest is history. That’s a relationship that might have never been, if it wasn’t for a two-way leap of faith and a website that tries to ‘connect people all over the world for inspiring experiences that create understanding, personal growth and trust’.

I strongly believe that there’s magic waiting to be found, if we would only allow ourselves to believe in the innate decency of other human beings. I want my niece and nephew to grow up knowing that not everyone is out to hurt you, that there are nice people out there in the big, bad world. Instead of teaching them not to talk to strangers, I would perhaps try to teach them how to do so responsibly, in a manner which doesn’t end up hurting them.

Love,

D

P.S. Here’s a song for you.

youtube

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Coercive Dancing or ‘Shut Up and Leave Me Alone’

Dear Nobody,

There are two kinds of people in this world: those who love to dance and those who don’t. Amongst those who love it, there are two sub-categories: those who leave non-dancers alone and those who don’t. There are no further sub-types of people in the latter, they’re all fucking idiots.

I’ve had a lot of time to think about this between the many songs I’ve been forced to dance to at parties I’ve been forced to go to. Sometimes I don’t know what’s worse, them insisting that ‘everyone can dance’ while beaming positively at my foot-tapping or them trying to prove their point by taking hold of my arms and swinging them around wildly. Bleeding idiots, really.

I appreciate dance as an artform, I really do. I wish I could do it, but I can’t and I’m ok with that. I don’t mind settling for buying tickets to watch a performance or being an appreciative audience on a crowded dancefloor, in awe of the fluid grace and confidence of people with some level of brain-body coordination. But please don’t tell me that ‘everyone can dance’, because there are some people who just cannot (and will not). And puh-lease, your idea of having a good time is being part of a writhing mass of inebriated bodies, singing and dancing along to music which is an insult to the millions of years of evolution it took to form the modern human brain. Your opinions are invalid.

There’s this routine I follow when I’m forced to dance. First, I shuffle my weight from one foot to the other, then I curl up my fists and move them up and down, while I silently wish that everyone around me would drop dead. Sometimes I even bob my head, if I’m feeling a little cheerful and/or if I’m drunk. But usually, I try to smile throughout the duration of the well-meaning torture, so that people don’t realize how grumpy I truly am or how badly I want the world to end. If you haven’t maintained a fake smile for as long as I’ve had to sometimes, you’ll never know how much your cheeks begin to hurt from the effort. But I’d like to think that I’ve perfected at least that art by now.

Then there are those who’ll say “Just let go. Forget the past. Live in the moment.” That sort of thing, which is great if you’re running a wholesale business that prints quotes on t-shirts back in the 90s or whenever the hell that shit was popular. If the music is loud enough, which it usually is, I will reply “This is awful. You’re annoying me. I hope one of us dies so this can finally stop.” That sort of thing. And the whole time, I would have been wondering how on earth this is even supposed to be fun.

Are we human or are we dancer?

Love,

D

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Matters of the Heart or ‘Why I Stopped Playing Ultimate Frisbee’

Dear Nobody,

You might not have heard of Ultimate frisbee, but it’s one of the best things that has ever happened to me. It’s a team sport which I discovered in 2015. Until then, I hadn’t realized that I could play a sport. Soon, love quickly turned to manic addiction. Family and friends would groan at the mention of the F word, which in this case referred to the combination of football, basketball and rugby, with a frisbee thrown in the mix for fun. For a blissful two years, not much else existed for me. I would miss birthday parties, family dinners, and drinks with friends, just so I could chase after a 175g plastic disc. I don’t know what it is about a frisbee sailing through the air, its path determined by the presumably complicated physics of angular momentum, gravity and prevailing environmental conditions – but it’s always a moment of pure abandon, an exhilarating feeling as you bound after it, mind completely blank.

You know what made Ultimate frisbee so special though? It was the people I got to play it with. For the longest time after I returned home from a masters abroad, I found it hard to make new friends or connect with the ones I already had. This was because my masters coursemates had set the bar too high for most other people. But in discovering Ultimate, starting a team in Bangalore and interacting with the larger community, I felt like a polar bear who’d found an intact sheet of sea-ice in the Arctic (i.e., thrilled, what with climate change and its impact on our planet). My point is that I finally felt at home for the first time in two years, part of a cult (as my friends still adamantly maintain) and amongst a diverse set of like-minded people. My team, which we fatefully christened after a spinal cord injury that I would suffer from a few months later, meant the world to me. If I wasn’t at team practice on weekday evenings or on weekends, then I was at some team dinner or Ultimate tournament or post-tournament party or the other. I had found my paradise.

My dearest Nobody, when I started writing this letter to you in December 2017, I knew it was going to be a sad, melancholy one. We’re now in April of the following year, but it seems like this letter will still be sad and melancholy, however, with a faint glimmer of hope. Maybe. Let’s see.

As I was saying, I had found my paradise, but not for long. In mid-2016, I landed what I thought was my dream job with a dream organization. It required me to spend nine months with a few short breaks at a field site in a remote part of the country surrounded by forests and wildlife (I have written about this here). I arrived at the stipulated location with my bag and a burning love for Ultimate. Is that how evangelists feel? I had brought a few frisbees with me and it wasn’t long before I started terrorizing the village kids. Yikes, is that also how evangelists feel? Through my proselytizing, I met a young girl (now a good friend), who was a brilliant football player. She took to the sport like a bear to honey. Pretty soon, when I began to teach Ultimate at local schools, she was my assistant coach. Outside of Ultimate, she was my coach, always motivating me to go running with her at unearthly hours on cold, dark winter mornings, ensuring that I stretched afterwards. Despite all my mock protests, I was glad to be whipped into shape, because I knew that I had to go back for tournaments and I couldn’t, or rather wouldn’t, let my team down (out of touch maybe, but certainly not out of shape, I’d say to myself sometimes). It was difficult getting out of my field site and all the way across the country to national tournaments (not to mention expensive AF), but there was never a question about not making it. That first field season, despite the endless challenges it posed with regard to working with local communities for wildlife conservation, was glorious. I loved village life on the forest fringe, watching hornbills at their nests during the breeding season, having new experiences practically every day – it was all very exciting. I even ploughed through the few crazy months that I had to spend alone in the field, always keeping sight of the silver lining. And then after the field season ended, I went back to Bangalore, which happens to be home and also where our office is located and where my Ultimate team is based. Three months later, I was back in the field but this time around something had changed.

When my second field season/exile to the field began, I sensed something amiss but struggled to put a finger on it. I was more acutely aware of the sacrifices I was making to be here, far, far away from my family, friends and team, knowing fully well that their lives would go on without me, as it had before, and that I would miss watching my niece and nephew grow up, that I wouldn’t be able to improve my game at team practice sessions, that I would miss almost everything that added meaning to my life. Before I landed this job, I had missed many social gatherings and family visits for Ultimate, so this shouldn’t have been a revelation to me, yet not having a choice in the matter seemed to make all the difference. I felt like my life was on pause when I was in the field, resuming only when I went home. The only problem was that only my life had been on hold, and I was constantly trying to catch up with those around me who’d moved on. I stopped going for morning runs with my local friend. I had already missed one tournament in Chennai when I left for the field and I wasn’t going to be able to make it for the one in Surat later in December, so I surmised that there wasn’t any point in working on my fitness (my only motivation to stay fit has always been so that I can play Ultimate). I missed my team terribly. I couldn’t bring myself to do throws with either my friend or the other village kids. I completely stopped teaching Ultimate in schools in my free time (much to the disappointment of some of the kids, unfortunately). I was suffering from intense nostalgia (the Portuguese word ‘saudade’ comes to mind) and also what is referred to in the digital age as FOMO or ‘fear of missing out’.

After three months of not throwing or working out, I went home for Christmas. It was a relief, to say the least, and I tried to play as much Ultimate as I could manage. The next national tournament was scheduled to happen in Ahmedabad at the end of January, but there was no way I could have stayed on that long. With a renewed sense of determination, I decided to play that tournament no matter what. I knew that it would be a long journey, travelling the entire breadth of the country from the easternmost state to the westernmost one. Even the staggering costs of air travel (from the nearest airport, which is in the neighbouring state, and with multiple connecting flights thereafter) couldn’t deter me. And so I played Ahmedabad Ultimate Open with my team, who had travelled together from Bangalore. Perhaps because of expectations I had from previous tournaments we’d played together for two years, I was a little disenchanted. Ours being a university team, there’s a huge turnover of players and the team composition inevitably changes as players come and go. I wasn’t used to playing with many of the newer players (to put it technically, we didn’t have ‘chemistry’ which is built over time as you practice together) and I was extremely rusty. It was a frustrating three days for me. My body wasn’t coping well with the physical abuse that comes with tournaments, my game was shit, and I missed some of the older players who I was used to playing with. But while my fantasy on the tournament field was shattered, off the field, I had a great time getting to know the new players and reconnecting with the few old ones, exploring Ahmedabad’s crazy street food scene and playing ridiculous games until late each night with the team. It was almost like old times. I was sad to leave because I didn’t know when I would get to play another tournament again, even as I realized that there was probably no point playing unless I had been able to practice with the team – I wasn’t going to be able to contribute much on the field otherwise and might even get in the way, especially if new strategies that I was unaware of were being executed.

With the tournament behind me, I did have one thing to look forward to though. Two of my friends/teammates were accompanying me back to my field site and would spend a few days there. It turned out to be a really great trip and on the eve of their departure, we played an impromptu Ultimate match with my friend and a bunch of village kids who were playing football when we invaded their ground. This rekindled my love for Ultimate and after they left, I resumed my fitness routine in part, if not fully. I was starting to feel good again and things only got better when I got selected to attend a workshop in Bangalore, after which I spent a few days working from the office and going for team practice sessions on alternate evenings. When I left for the field once more, it was with a conviction that things would be different this time around and that I would struggle to stay positive and motivated.

As I finish writing this letter to you, my friend, it’s with a stinging realization that tomorrow, my teammates will leave for Kodaikanal, where a special tournament of great sentimental value is happening for the first time in over six years. I won’t be joining them because I have to be an adult who can’t shirk work responsibilities, especially at a crucial time when we are in the process of shifting base camps and bang in the middle of the hornbill breeding season. Life seems bleak once more. I know that my heart will sink a little when I see team photos and there will be a tight knot of sadness in the pit of my stomach when I read about games and exciting plays on our Whatsapp group. Thanks to advances in modern communication, I can at least live these experiences vicariously, but it’s times like these that make me wonder at opportunity costs and whether any of this is worth it. I guess that glimmer of hope was just that – an illusion.

Love,

D

New beginnings: Our first Ultimate frisbee tournament, Bangalore Ultimate Open, June 2015. We were all glad to get a new jersey designed immediately after, but this yellow-green one still holds immense sentimental value to the squad who played that first tournament.

Standard practice: Team huddle before every match.

The amazing Indian Ultimate frisbee community. Photo courtesy: Ultimate Players Association of India

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

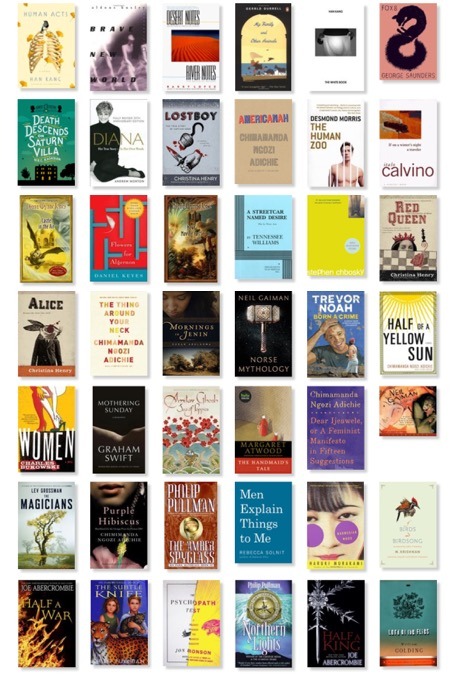

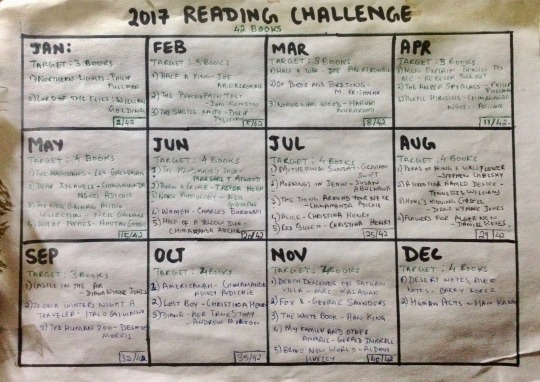

My Year in Books

Dear Nobody

When asked if I’ve read a particular book, often all I would have to offer on the subject is a simple yes or no and perhaps whether I liked it or not. The interrogator might proceed to throw questions at me or share details about the book, which are usually met with a blank expression and/or a shrug. And as is usually the case, I will then be asked why I read so much if I can’t remember a thing about the book afterwards. I suppose I read purely for pleasure. I read so that I can lead many lives, look through new eyes, walk in someone else’s shoes, experience a range of emotions that I normally wouldn’t in my day-to-day life. I read so that I can learn new things. I read so that I can transcend myself. I internalize elements that I like in the books I read and then let them go. I don’t read to remember, although if something does stick in my memory, that’s great too.

Since 2014, I’ve set myself a Reading Challenge on GoodReads at the start of every year. It was this blog post by scientist and role model, TR Shankar Raman, that inspired me and continues to do so. Some years I complete the challenge, some years I don’t, depending on where I happen to be in my life at that point, both physically and metaphorically. It turns out that extended breaks in between jobs are great for reading, especially because one finds oneself broke and at home a lot.

Most of 2017 was spent at my field site in a remote corner of Arunachal Pradesh with atrocious cellphone connectivity. I had to come up with a way to keep track of my reading challenge without GoodReads.

This year’s challenge was a modest 42 books, which I’m happy to report I completed earlier this month! Overall, it was a fun year for reading. I surprised myself by reading far less Fantasy & Sci-Fi than I usually do. Not at all by design, I ended up reading quite a few works of fiction and one memoir written by people from non-Western regions of the world – India, Nigeria, South Africa, Palestine, South Korea, Japan – and I’m glad for it because I feel like I have delved a little into the history and culture of these places, carrying them around like a collection of mental postcards wherever I go.

I first discovered Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie when I watched her TED talk ‘The Danger of a Single Story’ back in 2009, making a mental note to read her first novel Purple Hibiscus. I finally got around to it this year (Procrastination 101) and boy, I fell in love with the narrative, the characters, the way Adichie doesn’t tell you what to think but describes everything in beautiful detail (never failing to activate all the senses) and allows you to arrive at your own conclusions. I then went on to read her other books – Half of a Yellow Sun, Americanah, The Thing Around Your Neck, Dear Ijeawele Or a Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions – in quick succession. Through her writing, I learnt about the Biafran War (which I’d never heard of until that point), Nigerian cuisine (ah, I could almost taste some of it!), attire, what life is like growing up in a university campus in Nsukka or as a ‘Big Man’ in Lagos. I got a glimpse of sexism, religion, and the political history of the country that was forced into being by the British Empire. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is one of the three people I would love to write like, the other two being Vladimir Nabokov and William Dalrymple.

My book of the year was Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes, one that I would wholeheartedly recommend to just about anyone. Because it doesn’t matter who you are or where you’re from or what genre you stubbornly adhere to, this book will pluck at your heartstrings. A warning at the outset – it will not be easy, you will explore the dark side of human nature, the book will become a mirror that shows you parts of yourself that you would rather not acknowledge. You will never truly recover from the reading experience. But I can assure you that you won’t regret it. The book is in the form of progress reports written by Charlie Gordon, a borderline mentally disabled person with an IQ of 68 who works in a bakery. He has signed up for an experiment which, having been successfully carried out on a mouse named Algernon, is to be tested on humans for the first time. If successful, this scientific breakthrough will increase his intelligence by manifold. Charlie is excited about the prospect of becoming smart like his friends at the bakery. Reading through his progress reports, you are part of the process as Charlie begins to change, slowly at first and then in leaps and bounds. You watch as his relationships with the people around him change, as they start to treat him differently and he starts to realize the cruelty he was subject to. We also get glimpses of his painful past as his childhood memories resurface. In the meanwhile, at the peak of Charlie’s intelligence, Algernon has begun a sudden and unexpected deterioration, and eventually dies. What does this mean for Charlie? Ah, how can I possibly explain the range of emotions that this book evokes! It’s a journey of the soul.

Alice by Christina Henry was another great find this year. It’s a dark retelling of Alice in Wonderland, all the more delightful for being gory and macabre. Alice finds herself locked away in an asylum, but she can’t remember what happened to her or how she landed up there. She only remembers a man with rabbit ears. I won’t say any more about it – you’ll just have to see for yourself! After the spectacular first book, I was quite disappointed to read Red Queen, which I thought failed on many fronts but mainly in terms of plot. But if you like Henry’s style as much as I do, you could skip the second book and move on to the morbid world of Peter Pan in Lost Boy instead.

Other books I would recommend are Born a Crime by Trevor Noah (hilarious, charming and eye-opening account of his childhood in South Africa in the post-apartheid era), Diana: Her True Story in Her Own Words by Andrew Morton (biography of Princess Diana, which I read only because I knew nothing about the Royal Family, it was an interesting read), Howl’s Moving Castle by Diana Wynne Jones (so much fun!), Women by Charles Bukowski (for his style), and The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky (better than the movie).

I have this strange compulsion to finish any book I start, no matter how awful. If you suffer from the same disorder, then I would advise against picking up the following books: The Magicians by Lev Grossman (the characters suck, the plot sucks, the writing sucks – apparently it’s a trilogy, I steered clear of the second book), Half a King by Joe Abercrombie (didn’t find much to like, but started the second book to see if it could get any worse, then finished it before I realized I’d been reading the third book, so I accidentally read the trilogy – sort of), Brave New World by Aldous Huxley (mmm, I didn’t enjoy it one bit, I think I only like his writing when he’s on mescaline).

2017 was also a year for audiobooks. Up until now, I was on the fence about them. Would my mind drift while listening to a recording of someone reading a story? What if I didn't like the narrator? And since I like reading, re-reading, and mulling over particularly well-written lines, I dreaded the thought of having to navigate my way through the forward-back controls and the minutes and seconds of the aural world. Despite these concerns, I downloaded Philip Pullman’s triology, His Dark Materials. All three audiobooks were fantastic and I had a great time listening to them. I also found that audiobooks are a great companion to have when you can't read (easily) - in the shower, while exercising or doing the laundry, while commuting, you name it. And of course, there's nothing like snuggling up under the blankets and falling asleep to a bedtime story.

I’m currently reading The God of Small Things by Arundathi Roy and wondering about what my target should be for next year’s Reading Challenge. In the meanwhile, do you have any recommendations for me to add to my 2018 shelf?

Love,

D

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Mysterious Affair of Women’s Undergarments

Dear Nobody,

You would think that the simple act of hanging your laundry out to dry would be a no-brainer. And it is, but mostly only if you’re a man. When you’re a woman in India, some minor considerations come into play. First off, you would stop to wonder if you can put your undies and bras out with the rest of your clothes. To answer this, you would have to set the context in your head. Where are you - rural India? Best to play it safe, after all, damp undergarments that haven’t seen the light of day have never really killed anyone. And even if you did die of a fungal infection, at least there was one less topic for the village to gossip about when you were alive. Urban India? Hmm, do you have neighbours? Are they weird? What are the population demographics like – all male? Are your undies too lacy? Are your bras too colourful and flashy? Do they attract too much attention? What is that nosy woman across the road going to think? Or that creepy middle-aged man who keeps staring at you from his balcony?

Illustration by Saniya Chaplod

If you’re a guy and reading this, you probably think I’m exaggerating, but you only have to check with the nearest woman to know that it’s true. Women are conditioned to think about all kinds of bullshit from an early age, so much so that it becomes hardwired into your thought process. I too have been similarly conditioned. The only reason the absurdity of the stigma associated with women’s undergarments dawned on me was because of something that happened recently. Along with some of our staff, I was conducting nature camps for school children at a beautiful location inside the nearby Tiger Reserve. It was an intense period when the only personal time we got was an evening every three days, when one batch of kids would leave and before the next batch arrived the following morning. On one such evening, I had a quick bath (the water was freezing) and hurriedly washed my clothes so that they could catch at least an hour of daylight before the sun set. Our only other female staff member seemed to have had the same idea, since her laundry was already hanging on the line outside. I began to move her clothes towards one end of the line, in order to make space for mine, when I discovered that she’d concealed her undergarments under some t-shirts of hers.

As ubiquitous as this phenomenon is, I was surprised because this was happening in Arunachal Pradesh, one of the seven states in Northeast India, generally a great place for women. Apart from being safe (where women don’t have to constantly look over their shoulder every time they step out alone or after dark, as you do in other parts of the country), the various tribal societies are largely egalitarian, in some cases even matriarchal. I’m not claiming that sexism and double standards do not exist here – they do, but they are far more subtle and definitely not even 1.5% as bad as elsewhere in the country. And yet, this incident made me realize how widespread and insidious some social norms are, especially when you don’t stop to question them. Why is there such a stupid stigma associated with women’s undergarments anyway? Why are we taught to hide them from the ‘male gaze’? Will men go crazy at the sight of a bra or what? Why aren’t boys conditioned from a young age to understand that bras are like any other article of clothing that need to washed and put out to dry? With the taboo and secrecy surrounding the issue of what women wear under their clothes, if an alien were to find itself on Indian soil, you might forgive it for assuming that women don’t wear any undergarments at all.

Like my hero Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, I too am trying to unlearn the lessons of gender that I internalized when I was growing up. I think I have a fundamental right to hang my undergarments out to dry with the rest of my clothes. Don’t you?

Love,

D

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Shifting Baselines or ‘I Don’t Even Know What’s Normal Anymore’

Dear Nobody,

Life in the field is certainly not for the fainthearted. This is not to say that I’m especially brave or that I was prepared for the sort of chaos that ensues on a daily basis here, but that after over a year of living in Arunachal Pradesh, I’ve entirely surrendered any illusion of control. Murphy’s Law is something we live by here – if anything can go wrong, it most certainly will. I’ve had to deal with more situations than I could have ever imagined.

A normal workday in Bangalore (the few months in the year when I’m based out of there) would begin with snoozing my alarm five times before rolling out of bed to get ready for work. I would then have a perfunctory bowl of cereal and hitch a ride with a colleague. At the office, time is spent checking Whatsapp, Facebook, occasionally the news, and emails (usually in that order), before staring at a screen and typing furiously every now and then, pretending to be productive. Lunch time usually sneaks up on me before I’ve managed to check off the first two things on my to-do list, after which there are only 2-3 hours before it’s time to pack up my things and leave. Then, I would spend a considerable amount of time commuting from Point A to B (either home or Ultimate Frisbee practice) in bumper-to-bumper traffic. There might be a few changes here and there, but the routine, for most part, stays the same.

Now let’s take a regular day in the field. We deal with so many variables – weather, staff, logistics, supernatural powers, to name a few – that it’s hard to make a plan in advance. But eternal optimists that we are, we will make one the previous evening anyway and hope for the best. We’ll call this Plan A. And for simplicity, we’ll assume we only have to co-ordinate work amongst 3 people. Persons 1 and 2 will go to the Tiger Reserve on the other side of the river to complete Task X. Person 3 will go to such-and-such village for Tasks Y and Z. There’s only one field vehicle, these places are too far apart and everyone needs to leave around the same time. So, Person 3 will take the vehicle while the other two cycle or walk. Pretty straightforward so far? It’s 4.30 AM the next day, Person 3 is ready to leave, but Person 1 is waiting for Person 2 to show up, since it’s not safe going into the forest alone. At 4.45 AM, there’s no sign of him/her and it’s getting light outside. So, Person 1 and 3 drive to Person 2’s house in the village, only to find that s/he had been binge-drinking all night and is in no state to put one foot in front of the other. What happens next? It depends. This was an extremely tame example but a fairly common occurrence – if not binge-drinking, it’ll be something else.

Two friends visited me in the field a few months ago. The afternoon that they were to arrive, I was called away on an emergency because a Wreathed Hornbill (magnificent birds, endangered, ecologically and culturally important) had been found dead near a village with a bullet wound at the base of one wing. Bacteria had been happily engaged in the decomposition process for at least a day or two, judging by the stench. But even so, he was a majestic specimen – three wreaths on his beak, an adult male. It was heartbreaking to watch the mandatory autopsy, to see such a beautiful animal butchered like poultry (not to demean the death of any living being, mind you). The cause of death, although obvious from the start, was determined to be the fatal injury caused by the bullet, fragments of which were embedded in the eye and the gular pouch as well. There was a hurried burial, the hornbill’s grave dug up right next to the equally majestic sambar that was found killed the previous week. It was only when I reported the events of the afternoon in a matter-of-fact way to my newly arrived friends and saw their raised eyebrows that I realized my baseline for a normal workday had shifted quite dramatically. It certainly wasn’t the last time it happened during their stay (I should actually ask them to contribute an article, perhaps!).

Portrait of a Wreathed Hornbill by Sartaj Ghuman

While we’re on the topic of autopsies. What’s the worst stench you’ve ever come across in your life? I bet a dead elephant trumps that by infinity. Once, I’d gone out to check some hornbill nests in the forest surrounding a far-off village with two of our staff. To get there, we had to crisscross a river multiple times and trek up a steep slope. On our way back, the wind direction had changed and we got a whiff of rotting carcass – probably a deer or something, we thought. Curiosity unabated by the fact that we had to hold our breaths, we followed the trail until it led us to a massive elephant-shaped carcass writhing with maggots. We reported the incident to the Forest Department, who then promptly asked us to lead them to the location. I think that was my first autopsy in the field, in fact. It’s hard to keep track.

And while we’re on the topic of elephants. This one time, I was heading to yet another far-off village to check on hornbill nests in the forests surrounding that area. It was 5 AM and not even halfway there, a small group of people stopped our vehicle. “You wildlife people,” they said. “There’s an elephant calf stranded in the water tank on the other side of that hill and the mother has been desperately trying to get it out for many hours. Do something.” We got out of our jeep to investigate, climbed up the hill, and all of a sudden came face to face with an angry adult female elephant. I say face to face because we were at the top of this tiny hill and she was at the bottom on the other side, and due to the difference in our respective heights, we were a standing a little above her eye level. Her calf couldn’t have been more than 2 months old, it was clumsily trying and failing to get out of the open water tank it had fallen into. The mother looked right at us and trumpeted once. Loudly. It was all the indication we needed to scamper back down the hill and back to the jeep. “We’ll call the Forest Department,” we shouted, as we stepped on the gas and fled the area, hearts thumping wildly. We were stopped once again on our way. Bad news again. One of our staff from another village, a young chap of 29 who suffered from chronic alcoholism, had died in a hospital in Itanagar a few hours earlier after his organs failed. His relatives were bringing his body back. Thoroughly shocked, we spent the next 4 hours helping out with funeral arrangements. On our way back to the base camp (with all plans of fieldwork abandoned, naturally), we stopped at the place where the elephant calf had fallen into the water tank. There was a huge crowd dotting every inch of the hill. The Forest Department had tranquilized the mother, while a JCB was brought in to break the tank and rescue the calf. At least one story that day had a happy ending.

There are countless stories to tell. Like the time I thought I would bleed to death after I got three Tiger leech bites on my butt which bled profusely for 8 hours, or the time we had to rescue a King Cobra from someone’s house in the village, or the rescue operations we’ve had to plan and execute when our staff get stranded for days deep inside the Tiger Reserve in the middle of the monsoon with no road or cellphone connectivity, or the expedition I had to plan once when we went in search of nests of the rare and highly endangered Rufous-Necked Hornbill, or the politics in this crazy place. I could potentially go on and on and on and on and on and on and on.. you get the point. All manner of utterly crazy shit happens here in the span of 24 hours, but at least there’s never a dull moment. That’s a good thing… right?

Love,

D

0 notes

Text

On Great Conversations or ‘Why Talking to Most People Makes My Brain Hurt’

Adapted from an actual letter I wrote to somebody - pen on paper and all.

Dear S,

A friend visited my field site recently. On his last night here, we sat outside the field station, moonlight bathing us and the surrounding paddy fields in a pearly glow, as we talked. It was the most enjoyable conversation I’d had in a long time. I can barely recall what it was exactly that we talked about, but it ranged from the difference between prose and poetry, books we had read, people we had met, difficult decisions we had made and what that said about us, why beauty is so important to us as human beings, transformation, the Doors of Perception, an essay about a bat. After this friend and other colleagues who were here for a short while left, I was once again on my own. But that one winding, interesting conversation stayed with me. It made me wonder about the sort of conversations I have grown to cherish, the people I’ve had them with, and more importantly, about why these are so few and far between. What did these people have in common, I wondered? Well, here’s a list I came up with, though it is by no means exhaustive.

1. Their names tend to begin with an S (yours included, obviously), though not always. My housemates in the UK, for instance, whom I’ve had many stimulating discussions with when we lived together, do not have names that begin with that letter. But it’s interesting to note this strange coincidence. And I remember when you and I first met in real life. We instantly launched into a conversation with complete ease, as if we’d known each other for years, rather than having only exchanged a handful of messages on CS. And I recall how every subsequent meeting thereafter resulted in us being completely lost in conversation, losing track of time, forgetting about all the other places we had to be and the people we had to meet.

2. They read voraciously and widely, and have varied interests, which automatically makes for great conversations. I don’t care much for current affairs, politics, small talk and mundane gossip (the latter especially makes my neurons want to crawl out of my nose). What I do enjoy discussing is ideas. I love making associations between disjointed thoughts and impressions in my head, a phenomenon which is fueled by interesting conversations. It’s like putting together pieces in a giant jigsaw puzzle, gradually watching the bigger picture take shape. I suspect this is the reason I binge-watch TED talks. I love expanding my mind to accommodate new ideas and perspectives. There’s always something to learn, even from the terrible talks. And it’s such a joy to share ideas with people of the same wavelength.

3. They are well-travelled and have an open mind (possibly attributable to the former). There’s a certain aura that this kind of people give out, which I have an instant affinity for. And I’m not referring to the kind of travellers who jet set around the world in their designer clothes and expensive shades. My travellers are often shoestring-budget backpackers, the kind that travel to experience a place, its culture, its people, rather than to ‘see a place’ as an outsider looking in. I took to you immediately. Even before you told me about how you ended up choosing the position in India, when you could have easily picked something in a place that was more familiar. I just knew!

4. They aren’t afraid of failing, which naturally means that they are always ready to step outside of their comfort zones and try their hand at something new. Remember that time I convinced you to play Ultimate Frisbee with my team before we were meant to leave for that party? Haha. You were always such a sport!

5. Maybe it’s because they read a lot, perhaps it’s because they travel - I don’t know - but these people tend to have truckloads of empathy. They can easily relate to people from completely different backgrounds, who have had unimaginably different life experiences from them. I’ve always found it easy to connect to them on a much deeper level than I do with the rest of humanity.

6. They’re great listeners! To be a great conversationalist (is that even a word?), I think you also need to be a good listener. This amazing insight comes from having been at the wrong end of many monologues.

7. They tend to be introverted and don’t feel the need to be the centre of attention all the time. I've also noticed that I can maintain a comfortable silence with them for long stretches of time.

8. They go out of their way to talk to strangers, which is, incidentally, how I end up meeting a lot of them as well (Exhibit A!).

But what is it about these characteristics that makes them so wonderful to talk to?? I don’t think I’ll ever figure it out. I’m just glad that these people do exist. Life would be rather dull otherwise.

Love,

D

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Unusual Career Choices or ‘WTF Am I Doing Anyway?’

Dear Nobody,

October 31, 2017: I’m writing this from my field station, far from home, in a remote village in the far-flung state of Arunachal Pradesh, India. I first arrived here in October last year, where I then spent the next nine months managing a wildlife conservation program that involves the local tribal community. I’m back here again until next July. The past one year has been one crazy adventure, with all the trials and tribulations that come with living and working in the field for such long periods of time. I get so caught up with day-to-day life that I barely spend any time reflecting on the vast majority of these experiences. I would like to take some time out to do this before it all fades from memory, and I would like to share my thoughts with you. Having someone listen to you sometimes validates your experiences. So, while I know this is a selfish gesture - because I’m writing more for myself than for you - I do hope that it will prompt you to share things with me in return, if you should feel like it.

I’m going to start by telling you how to get to our field station located in this remote village in Arunachal Pradesh. It is, after all, the first hurdle. The easy part is the direct flight to Guwahati, the capital of the neighbouring state of Assam. Once you land, the quickest and most convenient option is to take a taxi to our destination, which is 6-7 hours (about 260 km) away by road. However, since this taxi ride costs as much as the airfare to Guwahati, you will often take the other more painful route. First, you take an Uber from the airport to a location 25 km away from the city. Here you’ll find a big government interstate bus stand and further down, another unofficial (basically illegal) stop with a line of tempo travellers. You head for the latter. But brace yourself because there will be a crowd of young men here, all talking at you in rapid Assamese, tugging at the suitcase or backpack you might be carrying, insisting that you get on board their traveller. Beware because they will tell you anything you want to hear. “Are you going to Place X?” “Yes, yes, madam, of course.” A few hours later, you may find yourself and your luggage on the highway, waiting for another mode of transport because apparently the traveller you took was going to Place Y. Assuming you took the right traveller though, you will reach Place X, a busy township. You then shoulder your massive backpack or drag your heavy suitcase a little way down the road and across a major intersection, get on another traveller which passes by Place Z. If you make all the connections in time, you will get off at Place Z and might be able to take the bus which goes to our destination. If not, you’ll be stuck haggling with a few local taxi drivers until they’re willing to take you down the terrible 20 km stretch of road to our village for a reasonable price. Once you get to the check gate at the border of Assam and Arunachal, you will see a looming, rather un-aesthetic archway that says ‘Welcome to Place XYZ’, where the driver will pay Rs. 50 so that his Assam registered car can enter Arunachal without a permit (a bribe, in other words). If you’re unwilling to cover this ‘extra charge’, then you’ll be dropped off unceremoniously at the check gate, walking the remaining 1.5 km to our field station in the village, luggage in tow. This entire journey from home, starting with the commute to the airport, until you arrive at the field station may take about 12 hours, if all goes well.

You might wonder why anyone who isn’t a masochist would endure such a journey and to what end? In one of his papers, Nigel J. Collar, one of the inspiring wildlife conservationists of our times had this to say about our kind – “[conservationists are] widely perceived as benign and generous people, committing their careers to a regime of low pay, long hours, high stress and worthy — even if, in some estimations, essentially lost — causes.” However, as noble as our cause may seem, it doesn’t make much sense to a vast majority of the population who are preoccupied with the accumulation of wealth or material possessions. Hence, it isn’t surprising that my parents aren’t the only people who ask me why I do what I do. I get it all the time with tones ranging from utter disbelief to genuine bafflement. Why would I leave the convenience and comfort of the city to live in a tiny village of 50 houses and to carry out fieldwork in the forest in some isolated part of the country that nobody’s even heard of? Why would I leave behind my family, friends, Ultimate frisbee, cellphone network, hot water baths, chocolate cake and venture out so far? And just to save some endangered species - never mind that nature in all its glory and wrath needs no ‘saving’, it’s our own skins that we’re really trying to save.

In the past, I have warded off these questions by saying that wildlife conservation is my passion, that I want to be working in these challenging landscapes. But more recently, I’ve started to wonder at the truth in these statements. Passion is a word that’s thrown around too loosely in SOPs and CVs, in conversations with new acquaintances and old friends alike. ‘Bellydancing is my passion’, ‘chemical engineering is my passion’, ‘changing babies’ diapers is my passion’, whatever. I’ve started to really dislike that word. Passion implies a gravity that I simply don’t feel for anything, not even for Ultimate frisbee, a sport which I’m completely addicted to. Why then did I set myself on this strange career path (ignoring the fact that I think ‘careers’ are a ridiculous concept to start with)? More often than not, wildlife conservation is futile and frustrating. You’re up against economic forces and selfish human interests that you can’t possibly hope to reason with. There are many mornings when I wake up and wonder what the fuck (excuse my French) I’m doing with my life. I constantly question the point of any of it. And yet, for reasons unknown even to myself, I persist. I would pick this thankless, gruelling job over a 9-to-5 in front of a computer screen any day. So, the honest answer to my parents and the puzzled circle of friends and relatives is that I’m not sure.

While I can’t answer the ‘why’ of my choice of career, I know that the how of it plays a pivotal role in enabling this choice. What I mean is this – I can afford to go off the radar and live in the middle of nowhere because I have an older sister who valiantly shoulders all the adult responsibilities that I shirked off when I decided to come here, the care of our aging parents being just one tiny example. She was also the reason I got to go off and do a master’s abroad (the first in my family) in something as obscure as ecology, without having to worry about whether I’d be able to find a job after graduation. If it hadn’t been for the constant support and backing of my family, if it weren’t for all the privileges I’ve been fortunate enough to enjoy (sometimes without even realizing it – take this quiz), I doubt I would have been able to choose such a career. I think that when a lot of people in underpaid (and often glorified) jobs, like conservation or journalism, say that they aren’t doing it for the money, it often means that they don’t have to (here’s a link to an article about conservation careers and privilege – stop kidding yourself).

Do you ever guess at your true motivations for doing things?

Until next time,

D

0 notes