Note

Have you done anything regarding Lady of Legend yet? Beachy Head? I wonder if Lady still sees themselves as a 4900, or if Beachy Head has any fuzzy, vague memories of Great Northern days.

That's a great question, and one I answered (checks notes) 3 years ago.

The TLDR is that Lady of Legend is very mad about her current life circumstances and fully sees herself as a Hall-class, thanks very much.

As for Beachy Head... it's a bit harder to suss out. They used a lot of ex-GNR bits (and LBSCR bits too) but for those to still be usable today they basically would've had to machine the history out of them. Whether anything not of this time comes spilling forth out of Beachy is something that will only come out with time.

#ttte#sentient vehicle headcanon#ask response#no i'm not dead I just work for a living#I'm so tired#adulting is hard

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm just gonna reblog this for the 4th anniversary of COVID

An Ill Wind

Traintober Day 9 - Brace For Impact

So, this is the long one. There always has to be one. I hope this is the only one. As a note, this isn't horror, per se, but rather ominous dread at the most. At time of writing everyone reading this has lived through These Times. We all know what's coming.

-

As a housekeeping note - this story relies upon a lot of stuff I've previously written or it won't make much, if any, sense. I've tried to link everything in the first place it's mentioned. Please let me know if you're confused at any point.

-

This is also a very long story, with explanatory paragraphs that sometimes become Very Dense. I also wrote it exclusively between the hours of 11:00 PM and 4:00 AM over two consecutive nights. (A bad decision on my part - don't do that.) Please bear with me if there are any glaring errors - I did check this over but I'm not omniscient.

-

Summary - An ill wind blows from the East, and Sodor prepares for the oncoming storm.

-

Mid February - Tidmouth

“-and you’re sure that this isn’t an engine that British Rail… missed? Your father didn’t shove her behind a shed or something?” The insurance agent said, looking over his papers at Stephen. “Engines don’t appear from nowhere.”

“Tony, as much as I would like to believe you, in this case she did.” Stephen said seriously. “There are records of her being scrapped.”

“So you’ve showed me.” The agent was from Lloyds of London, and was used to people trying to ‘finesse’ their way out of a claim, but everything that he’d seen so far, and his many previous experiences with the NWR, was making this far more believable than he was comfortable with. “So I take it you didn’t pay for this engine?”

“No.”

“Of course. Do you have any idea of what something like Daphne would be valued at?”

A few papers were shuffled, and Stephen’s notepad emerged from the clutter on the desk. “I have tried to purchase several Deltics over the years. Depending on whether you wish to base the valuation on Alycidon, Tulyar, or Royal Scot’s Grey and Gordon Highlander together, Daphne is worth somewhere between fifteen million pounds, thirty million pounds, or, and I will quote directly here: ‘absolutely priceless, I will never sell either of them.’” He ran his finger down the paper. “He sold the two of them less than a month after I inquired. Everyone seems to think Jeremy Hoskings is a better owner than I am, to my continued bafflement.”

There was a snort from the insurance agent, followed by a sigh. “My department manager knows Hoskings. We’ll confirm the valuation with him, but for right now I’ll leave it at… twelve?”

“That sounds appropriate,” Stephen said, pleased that he’d come to more or less the same valuation before the meeting. “Is there anything else you need from us right now?”

“No, I can’t think of anything else at the moment.”

“Well then Mr. Kwon, we are done for now. You must excuse me for leaving so quickly, but my attention is needed all over the island. You do know your way out?”

“Yeah…” The insurance agent said, suddenly engrossed in his phone, papers half in his briefcase. “Excuse me.” He said, suddenly shoving everything into his case before bolting for the door. Stephen and his secretary watched as the man receded down the hallway, speaking rapidly into his cell phone in an unknown language.

“What was that all about?” His secretary asked, watching as the man vanished around the corner.

“I don’t know.” Stephen said as he shrugged into his overcoat. “Hopefully nothing.”

--

As it turns out, it wasn’t nothing. Stephen had a meeting with the Barrow City Council, and was making his way to the first class compartments of the Limited when he came across Tony Kwon in a coach vestibule. He was still talking into his phone, the language foreign but the tone urgent. He paid Stephen no mind, but when Stephen eventually reached his seat, he found the Insurance Agent’s case and coat sitting in the seat opposite his.

The train was almost to Kildane when Kwon eventually came back, his face flushed. “Is everything all right?” Stephen asked, concerned.

“No.” The man all but collapsed into the seat, as if the life had been drained from him. “My brother… he works for Toyota, in Yokohama. Last week he went out to China for a conference, and now fifteen of the people he went with have come down with this… strange pneumonia.” He tilted his head back to stare at the ceiling of the coach. “He’s a hypochondriac, so between that and the cruise ship I’m having to talk him off a ledge - metaphorically, of course.”

‘My goodness.” Stephen had no idea what to say to that, and offered some brief consoling words.

“Thanks, but there’s nothing you can do about this.” Tony blew out a breath resignedly. “Fuck, there’s nothing I can do.”

He looked like he wanted to say something else, but his phone rang, cutting him off. “クソ地獄, it’s my mother.”

He exited the compartment, and remained on the phone in the vestibule until the train reached Barrow.

Stephen left via a different door, and didn’t see the man again, but felt strangely ill-at-ease for the rest of the day.

----

A few days later - Near the Hatt Family Estate

The credit card machines at the petrol station were out, and Stephen was forced to go in and pay for his fuel in cash. As he waited in line, the rack of newspapers caught his eye; while the local Sodor papers were focused on the Lord Mayor of Suddery having some sort of extramarital affair, The Daily Mail featured a prominent picture of a cruise ship, with the equally bold headline of “PLAGUE SHIP”.

The woman in front of him seemed intent of paying for her petrol in pound coins, and Stephen tuned out the furor this was eliciting from the rest of the line of patrons, reaching for the newspaper.

The byline read ‘Yokohama, Japan’, and within a few sentences, alarm bells were ringing in the back of the Fat Controller’s head. He read through the rest of the article, and was only brought out of the paper by the clerk trying to get his attention. “Sir? We’ve run out of cash to make change, so right now, we’re-”

Stephen needed to be elsewhere, now, and he pressed a hundred-pound note into the clerk's hand before walking out, paper under his arm.

Something is happening. I can feel it.

-----

The next day - Tidmouth Station

The usual clutter on Stephen’s desk had been rather abruptly piled on the floor. In its place were newspapers and website printouts, their topics all on the eruption of a virus in Southeast Asia.

The Fat Controller himself was engrossed in a phone call when his secretary stuck her head in the door. “Rolf Tedfield to see you, sir.”

Still on the phone, Stephen waved at her to let in his visitor once the phone call was over. “-yes, Secretary, I understand but- no, I understand perfectly. Yes there is a problem! Mr. Secretary, Grant, for the love of god, do not brush this off! Something is happening! What proof do I have? THE NEWS! Good God man, just listen to the BBC! Or read the Guardian! Or the Financial Times! For god’s sake, I found an article about this next to a page three girl in The Sun!” There was a pause as the man on the other end of the call - The Secretary of State for Transport - said something, and Stephen’s head dropped almost to the desk. “It is not like Ebola. It will not go away on its own.”

There was another pause, and his head met his desk. “The position of the government is that this disease will not be a threat to the United Kingdom. Do you mind if I quote you on that? Considering that Hong Kong has a land border with China, I feel very differently. Yes, I am aware the border has been closed for a decade but considering there’s a steady stream of asylum-seekers going through there I feel like it may not- yes, Mr. Secretary, thank you, Mr. Secretary. Goodbye.”

He hung up the phone as gingerly as he could before staring at the ceiling and counting down from ten. When he reached zero he called in the visitor. “Rolf. What can I do for you?”

The manager of Crovan’s Gate works sat down with a distracted sigh, his eyes scanning the papers on the desk. “I think you’re already ahead of me.”

Stephen followed his gaze. “You’re following this too?”

“Aye. I’m from Hong Kong, got most of my family there still.”

“I didn’t know you were from there.”

“My parents went over from Pembrokeshire in ‘49. Anyways, my sister and my brother still live out there; few cousins too, and they’re scared, Stephen. Whatever this is, it hasn’t been sitting around at the Chinese border.” He tapped at his phone, and pulled up an image from a messaging application. It was taken from a high-rise building, showing a group of helicopters and rescue boats surrounding a ship. “Five days ago a Chinese trawler got run over by a ferry. Coast Guard went and picked up the crew, took ‘em to Queen Mary Hospital. Now the entire place is on lockdown. Everyone thinks it's SARS but… sir, from what I’m hearing it’s worse than that.”

Stephen felt suddenly sick, and then realized that he should probably start using a different expression. “When was this?”

“Last night, well, it was daytime there. We’ve not heard anything because it’s still the middle of the night there.”

“And they’ve only now locked down the hospital?”

“Yeah. For all the good that will do.” Rolf seemed to be on the same page. “S’like waiting until after the zombie bites you.”

The Fat Controller took a deep breath, and steadied his nerves. “Thank you for bringing this to my attention. As you might have heard before you came in, I was on the phone with the Transport Secretary trying to convince him of the seriousness of this, and I was not successful. I feel that we are going to have to act on our own.” He rose from the desk, already composing an email as he walked, and swung open the door to his office.

“Sir?”

“Rolf, I don’t know what I am going to do just yet, but I want you to - very quietly - start pulling all the coaches we have available in the out-of-use lines and the P-way trains and start making them habitable again. Interiors, then mechanicals. Focus on the buffet and sleeper cars first.”

“Yes sir. Why sir?”

“At the moment, I’m not sure yet, but I feel that having spare beds and hot meals will only help us. Aside from that, I want you to make sure that the works is stocked on spare parts and other consumables, and stop all new work on the engines and coaches.”

“Sir?”

“I mean it, Rolf. Finish everything that’s in progress as quickly as possible - use as much overtime as needed - but unless an engine catastrophically fails I don’t want anything or anyone in pieces right now. Something is happening. I’m just not sure how bad it will become.”

With that, Stephen left, his coat flapping out behind him dramatically as he marched towards the door to the station proper. Rolf watched him go, and blinked owlishly before pulling out his own cell phone, taking careful notes on what had just been said. “Did you get all of that?” He asked Stephen’s secretary, who was used to the Fat Controller’s occasionally abrupt departures.

Without a word, she shoved a piece of notebook paper into his hand. On it, in neat handwriting, was everything that had just been said.

“Thank you, Gladys.”

------

A few days later - Suddery

The Sodor Regional Council - the governmental board in charge of Island-wide affairs - met in a lecture hall at the city’s technical college. Usually they met inside Suddery’s Government Hall, but the short notice of their meeting meant that the hall was being used for other business. The atmosphere inside the room was decidedly tense - the unusual surrounds and urgent nature of the meeting meant that everyone was ill at ease even before the proceedings began.

The Mayor of Kirk Ronan spoke first. He was a svelte man of about forty, in his youth a multi-time gymnastics medalist at the Commonwealth Games. “Look, we all know why we’re here, and we all know what’s going on. Let’s dispense with the pleasantries and get down to it: There’s a sickness coming, from China, Japan, Iran, and now Italy from what I heard on the car ride here.”

A few murmurs came after that, and he held out his hands for quiet. “Now I’m sure that almost everyone here has called down to London at some point, and they’ve all said the same thing, haven’t they?”

“Yeah,” came one voice in particular - the Barrow Harbormaster, who watched five ferries a day pull into his port, each one loaded full with French and Irish passengers. “That we’s gonna ignore Hong Kong bein’ loike The Walkin’ Dead and just hope tha’ the Border Force can do bet’er wit’ t’is than theys do wit’ the moigrants.”

London seemed to think that, like Rabies, Termites, and asylum-seeking refugees, the width of the English Channel was all that was needed to keep the mysterious ‘asian flu’ out of the British Isles. Frustrated mumbles broke out as everyone tried to recount to their neighbor the lies that their contact in London had fed them.

“Thank you, thank you, I know what it was like, I phoned them too.” The mayor signaled again for quiet. “I know we are all frustrated. I know that we are all in the dark. I know that we’re all scared.” And for a moment he let his guard down, and showed his true emotions on his face, before continuing.

“But we aren’t some helpless home county who can’t do anything themselves. We’re Sodor, damnit. London hasn’t given a monkey’s arse about us in a thousand years and they’re not about to start now. So what are we going to do about it?”

Despite his best efforts, Stephen Hatt’s lifestyle and means of employment meant that “punctuality” was something he only ever chanced into, rather than it being a regular occurance. In this instance, James-related issues at Tidmouth had meant his arrival at the hall was almost ten minutes after the meeting’s already-delayed start time.

Fortunately, chance often smiled upon Stephen, and he hadn’t gotten this far in life without being quick on his feet. “If I may,” He called out as he strode through a side door near the lectern. “I do have some suggestions.”

--

Two hours later

The meeting had gone as well as a crisis planning session could go, and the participants filed out with brimming notebooks both physical and digital, their faces grim with worry or steeled against what would happen next.

The parking lot of the technical college backed up against the city marina, and a cold sea breeze whipped across the tarmac, rustling papers, tugging at clothes, and teasing hair. Stephen took refuge in an enclosed bus shelter to organize his notes, and was joined a moment later by a man he knew more from reputation than meeting - the head of Wellsworth’s St. Tibba’s Hospital, the largest and best hospital on the Island. Stepehen knew very little about the man - his first name, (Dembe), his nationality (English, to Ugandan parents), that he was a paediatrician by training, and that he’d been appointed head of St. Tibba’s over several local candidates whose CVs may as well have been written in crayon when compared to him. He’d sat through most of the meeting in complete silence, only answering questions when asked directly.

“Doctor.”

“Mister Hatt.”

There was silence, broken only by the doctor pulling out a carton of cigarettes and a silver lighter.

“Your ideas are sound.” The man said only after he’d puffed a Dunhill into life. “But it’s not going to be enough.”

“Do you really think that?” Stephen kept his expression neutral, staring out into Suddery Bay rather than at the other man. Fittingly, a storm was brewing on the horizon, huge clouds rising into the sky.

“I do.” The cigarette smoke came out in measured smoke rings. “We haven’t got enough beds.”

“Surely the-”

“It doesn’t matter how many train cars you give us, Stephen. It doesn’t matter if there’s a line of them going from one end of the Island to the other. We’ve only got two hundred fifty beds across the entire Island, and our staff levels reflect that.” Another, more violent puff of the cigarette followed. “Give us all the beds you want, but what we need is doctors. And you can’t build those out of an old train car.”

“What would you recommend we do then?” The storm was beginning to worsen, and lightning crackled across the high tops of the clouds.

“Honestly? Pray.” With that, the man raised his collar against the cold wind, and walked across the parking lot to a mid-sized saloon car at the back of the lot.

Stephen waited another moment, carefully adjusting the papers in his folio, before heading off.

He’d just opened the door to his Audi when his cell phone rang. He waited until he was inside the car before answering. Intriguingly, it was Louisa Duncan, Fergus Duncan’s daughter, and new controller of the Arlesdale Railway. She’d been in the meeting with him, and had left not even ten minutes prior.

As he answered, the skies opened up, and a torrential downpour thundered down onto his car. At first, it was hard to understand what Louisa had been saying; her voice was broken with tears and sobs.

By the time he understood, the rain was pounding hard enough that his own sobs couldn’t be heard.

Less than a month ago, on the fourth of February, Ivan Farrier, the Chief Mechanical Engineer of the Arlesdale, had gone on a long-awaited holiday to the Italian Alps with his wife Amanda.

It was now the twenty-seventh, and both of them were dead, killed by the ill wind from the far east.

---------------------------

March

For the next week or so, everything went quiet, but it did not go gentle.

In Crovan’s Gate, the works threw itself into overdrive; and seemingly every useful piece of rolling stock, from first class coaches to old General Use Vans left over from BR’s discontinuation of newspaper trains in the 1990s, were being scrubbed and painted to within an inch of their lives. Bafflingly (to them), once their interiors were refreshed, they were shoved outside, onto the storage tracks, while more coaches were pushed in to take their place. In the locomotive depots, the engines undergoing overhaul were suddenly being kept up at all hours of the day, as their repairs went on around the clock. Dane, one of the electric locomotives, would later remark that his overhaul was so quick it had taken three whole days off of the official Works record.

At Wellsworth, St. Tibba’s hospital was receiving deliveries of everything from life-saving medicine to whole hospital beds, much to the irritation of the higher-ups at the National Health Service, who were under orders from London to minimize any potential panic. The hospital director found himself keeping his supervisors at bay more and more. His usual tactic was forwarding them email chains and whatsapp screenshots from colleagues in Hong Kong, who had been caught effectively off-guard, and were now paying a heavy price. As the days went on though, he wasn’t sure if it was calming or terrifying that the complaints slowly trickled to a halt.

At Tidmouth, strategy meetings were being held seemingly every hour. No detail was left to chance, with the limited information they knew being factored into their plans for the future. Engine cabs were being measured, much to the confusion of the engines themselves, platform signage was reassessed, and staffing requirements were being examined with a fine-toothed comb. A huge sum of money was spent from the company’s discretionary fund, and arrived in the form of a heavy goods vehicle, which backed up to the station’s sole loading dock and disgorged pallet after pallet of masks, gloves, soap, and disinfectant, to be distributed as needed.

In one of the upstairs conference rooms, a pair of 70-inch televisions sat on one wall, the joined displays mostly empty. They displayed the master list of scheduled trains for the railway, a vast, spreadsheet-like document that documented every train movement on the railway’s February-May spring timetable. Daily trains were often “booked” months in advance, and the chosen rolling stock was altered as required. In an ordinary March, trains would already be scheduled out until the end of the spring timetable in May. Now, only train 3B00 - the Flying Kipper - was scheduled beyond the end of the month, its nocturnal run sitting alone on several score of date markers, going all the way to the bottom-right corner of the screen: MAY-1-2020.

-

In the sheds, the engines grew more and more concerned. The “minor virus”, as London still called it, was now making the headlines of every television, newspaper, and social media platform in the country. While the general public still viewed it as something that was happening to other people, there were many in the NWR fleet who remembered the Spanish Flu of 1918, or, more recently, the mass hysteria that had surrounded the SARS outbreak in 2002.

“Something vicious this way comes.” Edward muttered one morning in the sheds, as the news showed the ever-unconcerned Prime Minister giving a news conference on the state of the lockdown in Hong Kong.

“It’s not coming,” Thomas said grimly. He was old enough to remember 1918, and even if he hadn’t, Tornado was connected to the Internet, and found increasingly-distressing posts about the disease on social media with every passing day. “It’s already here.”

-

Meanwhile, on the main line, one green engine came to another.

“You’ve heard about the virus?” Tornado asked, trying her hardest to be subtle and discreet.

“Yes..?” BoCo answered. “So has everyone else. Why are you whispering?”

“There’s something I wanna talk to you about.”

“Oh?”

“I hear they’re holding a diesel gala at the Crewe museum next month.”

“Tornado, there’s not going to be a next month at this rate.”

“That’s not what I meant.”

“Okay…”

“They’re taking diesels from all over the country for this - they wanna show off engines that need restoration funds.”

“Oh good, a sideshow. How modern and progressive of them. I’m sure PT Barnum would be honored.”

“Who?”

“Nevermind. Is there a point?”

“You’ve been seeing how the economy is going away again?”

“Yes.”

“Well nobody’s gonna have any money to fix them, innit?”

“And..?”

“We’ve gotta do something!”

“About what? The virus? The economy? Tornado, we’re engines!”

“Not that! Our brothers!”

“What?” BoCo’s mind spun for a second.

“They’re bringing your brother, 05, down to Crewe for this gala - he might already be there, and they’ve got Peter, my brother, there too.” Tornado looked more scared than BoCo had ever seen. “If they run out of money… they’re never gonna get fixed up.”

“What do you propose we do?”

A mischievous glint filled her eyes, and a pit suddenly opened up in BoCo’s crankcase. “There’s a container train going to the Crewe Freightliner yard right down the tracks every Wednesday and Sunday. I say we get on that train and steal them!”

--------------------

Two Weeks Into March

The Prime Minister had finally started to show concern whenever he appeared on the telly. Mass panic in Hong Kong forced the Queen to make an address to the nation. On Sodor, the early stages of the Regional Council’s plans started to come into effect, and public events were canceled or majorly curtailed by government order. Supermarkets began self-imposing purchase limits, and all Universities on the Island began transitioning to online-only classes, with the local school authorities following in their wake.

Slowly, the NWR began to cancel off-peak trains, and office staff began figuring out how to take their work home with them. In the midst of it, someone made a “meme” - a form of image-based joke - about the drivers taking their work home with them, using an image of Thomas’ infamous crash into the Ffarquhar stationmaster’s house. (In a sign of how deathly serious the times were becoming, even Thomas himself found it funny.) The harbours at Knapford and Tidmouth, which were controlled by the NWR, began influencing quarantine protocols on incoming freighters, and several cruise ships were denied entry. The harbourmasters at Kirk Ronan, Barrow, and Tidmouth began impressing upon the ferry companies the importance of canceling their services, to limited success; the international ferry services from France and Ireland stopped, but Northern Irish and Manx ferries all continued with minimal delays or curtailments. The airport at Dryaw, however, was more than willing to comply, and all but two passenger flights to the Island stopped before the 14th, with cancellations lasting for two weeks. All cargo flights, save for the mail, stopped as well.

In all, it seemed like the Island was weathering the oncoming storm well, and those in seats of government - who had been expecting criticism for their overly cautious approach - were instead receiving praise from London. If the entire country acted like they did, they were told, this whole thing may blow over in a month!

-

Then the wheels came off.

-

It started in the United States. President Trump declared a state of national emergency on Friday, and state-by-state declarations of emergency put nearly the entire country in lockdown by the end of the weekend. The already-down global financial markets fell through the floor on Monday morning.

In the United Kingdom, those who watched the Prime Minister’s daily briefings on the virus swore up and down that they could see him sweating, and later on in the same address, he announced a recommendation to avoid unnecessary travel.

And on Sodor, the tipping point was reached.

Several days earlier, an outbreak occurred in a council estate in Slough. The source, or ‘index case,’ of the outbreak was found to be a Polish truck driver, who lived in Ireland but had decided to ride out the impending quarantine at his British girlfriend’s flat. He’d picked up a load bound for England in County Kildare, presumably contracting the virus at the same time, entered the UK through the Northern Irish border, and then boarded the Tidmouth ferry.

According to all the contact tracing done in those frenzied days before the world came to a stop, he had been aware that he may be contagious, and had worn a mask and gloves the entire time. He didn’t leave the cab of his lorry, nor did he stop for fuel or food until he was well east of Barrow.

But he was contagious.

And that’s all that mattered to the people of Sodor. To them, Pestilence, the first horseman of the apocalypse, had come through their land riding not a horse, but a shining white mechanical steed with the name of Scania.

This was someone that they knew about. And he’d tried to minimize his risk. They were a tourism and travel hub for the entire North-West of England and with the rest of society only now seeming to realize that anything was wrong, if nothing was done, the people of Sodor would soon be at the mercy of not international lorry drivers, nor the general public, but the worst, most careless form of humanity known to exist in the United Kingdom: The British Holidaymaker.

The end times were clearly upon them, and the Island reacted accordingly.

-----------

The Ides of March

The container train rumbled into Crewe at half past ‘fuck-me-it’s-late’ in the evening, long past dark, but still before the start of a new day. “Signaling issues” was the official excuse given by the train - some nonsense that would have Network Rail crews working all morning and into the afternoon to solve a problem that didn’t exist.

The electric engines in the yard were fast asleep, and few, if any of the people on the platform at Crewe station were aware of the engines that had led the train in.

BoCo, quite honestly, couldn’t believe that anyone had believed them at any point, but wasn’t about to quarrel with a trouble-free journey. Once the very tired crews from Freightliner had uncoupled them from their train, he and Tornado slipped across the main line into the old diesel works. It was now a heritage steam facility, owned by a very rich businessman, and the Fat Controller had a contract with them to supply his engines with coal, water, and fuel when they took trains to Crewe.

Being railway enthusiasts, they were overjoyed to see BoCo, and thrilled beyond reason to see Tornado, and many selfies were taken before the refueling was done. All at once, someone (Definitely not an employee who was also an A1 trust volunteer, who most certainly hadn’t been sent an email by Tornado, asking them to be at this place at this time, not at all.) remembered that, wouldn’t you know it, Blue Peter, the only other Peppercorn-designed locomotive in existence, was in the works right now! It was quickly asked if he’d like to see Tornado, and before anyone could say anything else, Tornado had pulled her brother out of the workshop and proceeded to start crying hysterically, claiming that she missed him. This put somewhat of a damper on the jubilant attitude of the staff, and they made themselves very scarce, very quickly.

The instant they were gone, the waterworks stopped, and Tornado beamed at Blue Peter, who was quite surprised at both the sudden start and abrupt end of the hysterics.

“Come on,” she whispered quietly. “We’ve got to go.”

“Go?” The older pacific asked, quite confused. “Go where?”

“Sodor, Silly!” she said, in a voice that she probably thought was secretive. “We’re breaking you out of here!”

“What? Why?”

“Haven’t you heard the news?” BoCo broke in. “The world is ending.”

“wha-I, when… it is?”

Blue Peter looked entirely too overwhelmed by the deluge of information, but managed to stutter out. “Ye-yes. They took him up the line to the museum for storage.”

“Yes, quite soon too. We’re taking you back to Sodor and by the by have you happened to see an engine that looks identical to me, by chance?”

BoCo’s face fell. “ That’s on the other side of the station. Damn it, how will we get him out of there?”

“Don’t worry,” Tornado’s eyes fairly twinkled as she said that, and both BoCo and Blue Peter began to think that they really should. “I can take care of that, but let’s go before anyone sees us!”

“Wait,” Said BoCo. “What about the couplings?”

Their crew had quite graciously agreed to see nothing and hear nothing in the Freightliner crew break room until it was time to leave. (Tornado may have annoyed them into submission. Maybe. Possibly. Yes, she did, and BoCo helped.) However this meant that they’d be unable to couple or uncouple anything once they left the depot. Fortunately, Tornado Had A Plan.

“Oi,” she whispered to the A1 trust volunteer. “Wanna have the night of your life?”

(BoCo and Blue Peter both nearly had their eyes pop out of their sockets. Tornado ignored them.)

The young man spluttered out a yes before he even thought to ask any follow-up questions, and very quickly coupled the three engines together, with Tornado and Blue Peter bracketing BoCo. He climbed into Blue Peter’s cab, and as soon as the dispatcher granted Tornado permission, the cavalcade was across the West Coast Main Line and into the Freightliner yard again.

Quickly stopping on their assigned road, Blue Peter was positioned at the rear of the container train, while Tornado and BoCo ran around to the front of the train, the young volunteer helpfully throwing switches (and returning them to the position they had been in afterwards) as needed. BoCo was now at the front of their odd little consist, and the volunteer had to stand in his cab with a radio to tell Tornado what signals were ahead, once she’d lied to ‘control’ about why she needed to go out on the main line again.

Unlike the heritage depot, the Crewe Heritage Centre was empty, it being long past their business hours. What little security there was, was focused inwards, not expecting sneak thieves to use the rails.

The museum grounds were small, nestled in between the V of two converging lines. Historic diesels in varying states of disrepair were scattered about the facility’s tracks. A small banner above the entranceway of the site’s sole building read “DIESEL DAYS - COMING 13 APRIL!”

BoCo’s brother - D5705, was easily visible from the tracks, parked next to a line of yellow, white, and red coaches that had clearly seen better days. An eye slowly opened as Tornado ‘peeped’ her whistle as quietly as possible. “I see that the Final Train has a sense of humour.” He rasped, his voice shaky and uneven. “Is it finally my time?”

“No!” BoCo said, much more firmly than he’d been intending. “It’s me, Fives. This is a jailbreak.”

The other eye slowly opened, the ruined diesel coming to wakefulness. “What odd company you keep, Two, and strange timing you have. But I will not be opposed to your plan.”

The Volunteer (who hadn’t introduced himself to BoCo, claiming that “the less you know, the better” like this was an actual criminal enterprise) hopped down, and quickly made the necessary connections.

“Go. Go with glory and make your life fruitful, oh-five.” Groaned a voice from the next track over.

The Volunteer looked around the diesels and his eyebrows shot into his hairline. “Oh wow! I forgot you were here!”

BoCo looked around his brother, and an eyebrow rose in surprise. “You’re not Ward… and what are you doing here?”

“I beg your pardon?” The partial APT-P set said, blinking the sleep from his eyes.

-

Ten minutes later, and a very chilly trainspotter with a cell phone arrived at Crewe station. He’d received a text from a friend - apparently the NWR had sent down a diesel and a steam engine on a container train to Basford. Hopefully he’d be able to get them when they-

A single solitary ‘peep’, and the sound of chuffing steam was the only notice he had the train was coming, and he almost fell off the platform when he spun around to see 60163 Tornado, 28 002 BoCo, D5705, and an ATP(?!) rolling quietly through the station.

Hie tried desperately to fumble for his phone’s camera app, but the dark conditions and poor-quality camera on his phone meant that he got a blurry, dark, and grainy smear of an image that showed nothing comprehensible at all.

He still tried to tell his mates, and posted the picture online, but nobody believed him - some laughed at him, and it was quickly forgotten about.

Tornado and BoCo had performed their heist without a hitch.

-----------

The Ides of March, Plus One Day

Bloomer was a notoriously slow riser. Even with a full head of steam, there would be mornings where he would have to be roused multiple times before he was fully awake. The crews got around this by just moving him while he was still asleep, and the old engine didn’t find it unusual to be finally woken up by the stationmaster “accidentally” spraying him with water while watering the plants on the platforms.

This morning, however, he was woken by an unfamiliar sound,and cracked one eye open to find himself in the yard - and it was in total disarray. “Land sakes!” He croaked as he woke up fully. “Lad! What’ve you done!”

In an effort to help out heritage rail organizations, the Fat Controller leased older engines from their owners for duties that the NWR had on the mainland. For example, the Barrow yard shunter was a revolving door of small shunters that came from various preserved lines across the country. For the past month, a quiet but dedicated class 06 had been doing exemplary work, and it seemed likely that his contract would be renewed for a few more months.

“It wasnae me!” The shunter protested, and Bloomer had to blink more than once to confirm what he was seeing. The shunter was chained down to the top of a low loader wagon, ready for transport back to his home railway. “They said Ah’m a-goin and quick! It’s the yon diesel tha’s makin the muckle disaster!”

A growl answered this, and a red Class 60 emerged from the depths of the yard, a line of stone hoppers trailing behind her. She was a low-numbered 60, number 003, and a nameplate was affixed to her cabs: PRAETOR. “Ignosce. I am not well suited to such tight confines. Would I happily leave the duties to this peritissimus faciens, but alas I must convey him home with the speed of Mercurius.” Her expression darkened. “There is an ill wind coming, and we all must seek safe harbor.”

She’d stopped to allow the yard crews to hand throw a switch, and the instant they finished, she pulled away out of sight, giving both Bloomer and the shunter the distinct feeling that they’d just been dismissed.

“Alrigh’,” Bloomer blinked again. “Ignoring that, they’re really sending you home?”

“Aye,” The shunter answered, grunting slightly as his flat car rocked - the 60 had taken the line of hoppers and backed them down onto his low-loader. The guard was already affixing a rear lamp to the flat wagon, indicating that the train was getting ready to depart. “An’ it’s no just me - they’s sending everyone home - ye as well. Something’s going doon, an’ it’s happenin’ now laddie.”

With a stately horn blast, the 60 set off as soon as the colour light signal changed to green, and within a few moments the train had vanished from sight.

“What does he mean? I am home.” Bloomer said somewhat indignantly to his driver.

“It’s not like that Blooms,” the man said. “You know that virus thing we’re all panicking about? It’s happening now. Mr. Hatt is packing up everything in the yard and I mean everything.”

“Surely you jest!” Bloomer retorted.

“Don’t believe me? Wait ‘til the yard empties a little more and we’ll get our train. Then you’ll see.” He said ominously, before leaving the cab and walking across the sleepers to the station building, leaving Bloomer alone in the yard as he built up steam.

With the outbound track now empty, Bloomer had a prime viewpoint of the yard, and what he saw began to confirm his growing fears.

The trains were arriving, and were doing so out of order.

Usually, at midday on a monday, the only inbound mainland train (other than the odd slow goods train that wasn’t on the schedule) was the Scottish Motorail, which took automobiles and their drivers on a non-stop trip from Edinburgh all the way to the ferry docks at Kirk Ronan. The next several hours were mostly goods trains which ran as far as Barrow, before leaving their trains for Sodor engines to take later; the last of which was a container train from the Freightliner yard in Crewe. The Sodor Motorail came after that - it ran out of London a few hours ahead of the night express, with auto carriers bound for Barrow, Kirk Ronan, and Kildane; it would drop the Barrow and Kirk Ronan cars at the special motorail platform just outside of the station, and continue on down the mainline, while another engine would come up the line and pick up the cars for Kirk Ronan. Finally, just before dark, the evening Express, with Pip and Emma powering it, would glide into the station, stop to pick up and let off passengers, and depart as fast as it arrived.

That was the usual order of things.

Today, the Scottish Motorail pulled into the station right on time at 11:55, with a single Class 37 leading it. The engine was tuxedo black, with yellow warning panels and small leasing company logos by the cab doors, a serious expression on his face. Curiously, the train didn’t continue on to the Motorail platforms, and instead stopped in the station’s run-through track.

Bloomer expected the train to continue on at any moment, and was baffled when over a half hour passed with no movement. “Signal troubles?” He called over to the 37.

“No.” The engine called back, his London accent fit for the BBC. “We await another train. The ferries will hold for us, don’t worry.”

Bloomer eyed the large number of automobiles lining up at the Motorail terminal, but said nothing.

A further half hour after that, one of the platform signals dropped, and Bloomer’s eyes almost popped out of his head as Pip appeared in the distance. “Aye?!” He spluttered as the HST screeched to a stop at the platforms. Unlike the usual song and dance of disembarkation, where passengers departed the train and transferred to semi-fast trains for their final destinations, or took the pedestrian underpasses to the exits into Barrow, there was instead what could only be referred to as a stampede, as passengers - many wearing clothes over their faces and mouths - stormed off the train en masse, charging down the platform stairs to the underpasses with a clatter of voices and luggage. The instant the last ones had gone (a group of wheelchair users who were herded off the train and into an electric cart brought out by the station staff), the doors to the station waiting room opened, and an identical exodus of people came charging down the platform - easily two or three trains worth of people, who crammed into the coaches while mumbling about ‘distancing’. They were heavy enough that some of the coaches groaned from the strain, and when Pip and Emma set off again, their engines howled from the excess load.

“It’s bad out there!” Emma called as the train cleared the platform. “Euston’s a ghost town! We’re one of the only trains with passengers!”

A tight ball of worry had begun to form in Bloomer’s firebox, and with this it just grew larger.

As soon as the train cleared the bridge, the signals dropped and then rose again, to ‘slow ahead’. With a ‘peep peep’ that caused Bloomer to swear in surprise, Henry slowly rolled through the station tender first, a short line of wagons used for transporting steel coils following behind him.

The stationmaster met the train on the platform as it rolled through without stopping. “You get them all?”

“Yes,” Henry said he counted the trucks again - yes, they were all here. “They found one of them in the far sidings, but we checked thoroughly before we set off.”

“There’s nobody else!” The lead wagon confirmed. “And I’s not just sayin’ that. Everyone else belongs to the Shipyard, not Sodor!”

“All right,” The stationmaster said. “You’re going to Ballahoo - they’ve got enough space in the goods shed for this lot.”

“Right!” Henry whistled as he picked up speed, and soon crossed the bridge.

As soon as he cleared, the signals dropped and rose for the third time in a row - this time with an added signal for the goods yard - and a horn sounded in the distance, followed immediately by a steam whistle. “What now?!” Bloomer asked himself in frustration and worry.

‘What’ in this case turned out to be the container train, which had BoCo leading, and Tornado not only as the second engine, but facing backwards to boot. They led the train into the far side of the yard and stopped just long enough for BoCo to get pulled off the train.

Almost immediately, the freight yard staff sprung into action and pulled the couplings for the first ten container wagons, which were bound for Barrow. Tornado quickly puffed away with them to the unloading tracks, where they were set upon by the yard’s container handlers.

In the meantime, BoCo reversed away to the fuel track, which was close enough to Bloomer for him to ask questions. “What in the name of god are you doing?” He hissed to the diesel. “The world is apparently ending and you both go gallivanting off to the mainland?”

BoCo was unphased as the fuel was hurriedly piped into his tanks. “We’re fine, Bloomer. I’ll explain later.”

“You had better!” Bloomer wanted to question more, but the signals dropped and rose for a fourth time, and finally, the Sodor Motorail clattered in.

If the double-header of BoCo and Tornado was unusual, this train was downright startling, as both Daphne and Delta were pulling hard as they rumbled into view.

It was easy to see why Sodor’s two strongest diesels were needed for this train - the Motorail operations required some extra rolling stock to be kept at the terminal in London for emergencies, and it seemed like all of the emergency stock, along with every other motorail wagon that wasn’t on the Scottish Motorail, were on this train.

And they were full.

Not a single space was to be seen on any of the open wagons, and every passenger coach was filled to standing with passengers. The train was so long that when it pulled ahead of the switches to the Motorail terminal, it was not only on the bridge to Sodor, but Daphne and Delta were actually on Sodor proper before they backed the train into the terminal.

The motorail trains set down coaches and wagons here, with the car wagons on one platform and the coaches on another. With so many coaches and car wagons on this train, neither rake fit into the platform, and stuck out over the edge quite considerably.

Not that the passengers noticed or cared. Much like the Express, they streamed out of the coaches that were on the platform like rats from a sinking ship, and swarmed the station building to pick up their cars. As each wagon was unloaded by the stewards, people would hurry to their cars, oftentimes wielding cleaning wipes or disinfecting spray, and then leave the station so quickly that the tires chirped. One young man was reunited with his fluorescent green motorcycle, and proceeded to leave the station grounds with his front wheel in the air, before vanishing into the distance at assuredly unsafe speeds, his bike’s engine almost louder than Daphne’s motor.

Speaking of Daphne (and Delta), once the last passengers had disembarked, they quickly pulled forward, taking about half of the coaches with them, and then backed down to pick up half of the car wagons - only the rear half of the train was for Barrow or Kirk Ronan, with the forward section going to Kildane. The guard blew his whistle, and the two diesels roared onto Sudrian soil and quickly disappeared into the distance.

“People need to get home.” BoCo, who had been watching the proceedings with Bloomer, remarked simply.

“What?”

“It’s the last Motorail to Sodor - there’s no more trains after today.”

“Good lord.” Bloomer’s eyes widened as the full weight of the situation came down on him. “How bad is it supposed to be?”

“Edward says it’s like the early days of the Spanish Flu.”

“Half the world got that!”

“I’ve heard worse.” Called the 37 as he carefully shunted the Scottish Motorail into the platforms. Fortunately, the train had been put together in such a way that automobiles could travel down the length of the car wagons with the use of gangplanks between wagons, otherwise the train would have been much more difficult to put together. “The rumour up north is that the government has been deliberately under-reporting numbers so as not to cause a panic.”

“I’d say they didn’t succeed there…” Bloomer scowled as the doors to the station opened, and passengers swarmed the train. There was pushing, shoving, and shouting, and it took longer than usual to get everyone corralled into the lengthy train.

There was a whistle behind Bloomer and BoCo, and Tornado appeared, still running backwards. “Right, I’m off! Best of luck!” Behind her, the ten container wagons and another fifty empty flatbeds, hoppers, vans and tankers clattered behind her - just about every truck and wagon left in the yard. With great care, she threaded her train around the Motorail, and into the distance.

Bloomer was still goggling at the sheer length of the train when the end of it came by. “Eh?”

“I will tell you, later.” BoCo hissed as the rear of the train, which consisted of a brake van, a steam engine that looked a lot like Tornado, a diesel that looked exactly like BoCo, and… “Ward? What are you doing here?”, passed by.

“Who is Ward?” Asked the electric intercity train as he disappeared into the distance on the end of the train, a red lamp dangling off of his face.

There was a long pause as both Bloomer and the 37 on the Motorail absorbed what they just saw. “BoCo… did you and Tornado…” Bloomer began, but when he looked over to where the secretive diesel had been, he found that BoCo had driven away!

“Be seeing you! Stay safe!” The green diesel called from the yard, as he was quickly connected to the remaining container wagons, before powering across the bridge as soon as the signalman would let him.

“Thieving youngsters...” Bloomer grumbled to himself as the red lamp at the end of the container train vanished from sight.

“Very crafty, elder.” The 37 whispered respectfully, as the last of the cars were loaded into the wagons.

As the 37 started reassembling his train, Bloomer’s driver re-emerged from the station, fireman in tow. “Right-ho, we’ve got a few pickups to make and then we’re off.”

“Pickups?” Bloomer looked around the yard. “There’s nothing left!”

As it turned out, there was, just a bit. On Sundays, the railroad ran ‘period’ excursion trains down the main line, and they’d procured a pair of reproduction LNWR open carriages for when it was Bloomer’s turn. The coaches were expectant, apparently having been told what was happening by the shed staff. “Quickly please!” Maribel, the lead coach said. “We don’t want to get left behind!”

“Nobody is going to leave anyone behind!” Bloomer said firmly, ignoring a creeping sense of being ‘out of the loop’ - this was not the first time that someone had been worried about being left behind, as if the drawbridge were going to collapse or somesuch. He worried he was missing something important.

Following them was Lilly, a former passenger coach that had been turned into the kitchen coach for the Permanent Way train. She was a full sized Mark 2, and was now laden down with literal tons of kitchen equipment. Bloomer groaned a little as his coupling stretched out under her weight. “Too small for this nonsense…” He grumbled. “Should’ve had the thieving idiot do it.”

Next was a piece of little-used rolling stock: the railway’s scale test car. Named Ingot due to his weight and shape, he sat behind the shed unless a yard needed to re-calibrate a weighbridge used for weighing goods wagons. “This must be serious if you’re taking me with you.” He said as Bloomer dragged him out of his weed-covered siding.

“Steel, actually.”

“It, erf, seems, agh, that way!” Bloomer gasped as he lugged the heavy wagon into motion. “Do they fill you with lead?”

“Agh.”

Then, there was a very long trek out of the yard, (“Heavy, fucking train..”) across the station throat, (“Look Blooms, the Motorail left a wagon behind for us.” “Oh. Joy.”) and back down a track that ran around to the far side of the station, (“When did this get put here?”) a little used siding that P-way trains sometimes parked in… oh dear.

“Oh thank goodness!” Marion the steam shovel gushed as Bloomer pulled up to her. “I thought I’d be left here!”

Bloomer ignored her, staring at the siding in disbelief. “You all do see my driving wheels? How there’s only two of them?” He glared at the yardmaster and the stationmaster, who looked at him like he was the mad one.

There were four cranes/shovels - Marion, Eh & Bee the breakdown cranes, and Jebediah - a diesel crane who worked with the P-way team. Each one of them was a heavy beast in their own right, and Bloomer would probably wear a groove in the rails before he got them moving, let alone Ingot and Lilly.

“Don’t worry, we’ve got it covered.” The yardmaster said, climbing into Jebediah’s cab.

“What’s he gonna do? Push?”

“Yes, actually.” Jebediah glared. “I’m self-propelled and mighty strong, you’ll do well to note.”

Bloomer was entirely too out of his depth at this point, and mumbled a thanks as the already heavy train was coupled to the line of cranes. Blowing his whistle, he pulled away slowly, expecting his couplings to go tight and stay that way, but he was pleasantly surprised to hear Jebediah’s motor rev up, and then feel the weight go from “immovable” to “manageable.”

They made for a bizarre sight as they rolled out of the siding and backed into the station. When they first got moving, Bloomer had felt ridiculous and vaguely self-conscious, but that faded as he stared out over the yard, and found it totally empty. Between all the frantic train shuffling, and the reduction in traffic over the last week, there wasn’t a wagon, coach, or engine to be seen anywhere.

It was honestly quite spooky, and that was before he looked into the station building, which was empty as a tomb despite it being the middle of the day. Only the staff were left at this point, and they were leaving the station too, carrying personal belongings and certain company items.

Somewhere in Barrow proper, a clocktower bell chimed twice, and everyone looked towards it. “I didn’t know there was a bell in the town.” Lilly murmured.

“It’s because usually you can’t hear it.” The stationmaster said as he shoved a porter’s trolley loaded with cases of company documents and the cashboxes from the ticket booths into the Kitchen coach. “S’not supposed to be this quiet ‘ere.”

Bloomer had thought that the full severity of the events unfolding around him had sunk in, but as he listened to the tolling bell, while also watching the assistant station master lock the doors of the station, he suddenly felt like the world was ending.

Honk-honk

The spell was broken by a horn sounding from the junction behind them, and everyone who could do so whirled around to see a small diesel multiple unit roll into the station.

“What in the absolute fucking hell is that doing here?!” The stationmaster swore as the train came to a complete stop next to Bloomer.

“Hi.” Said the DMU - her number identified her as 170 640 - with some amount of embarrassment. “Sorry I’m late. Signaling issues.”

At this point there was some amount of shouting. It turned out that this train was the 0910 service from Manchester to Norramby, and was supposed to have already departed Sodor in the other direction by now. In fact, it had been so long, with so little notice given about it, that both the NWR signalman and the Barrow stationmaster had assumed the train had been cancelled.

When the multiple unit meekly said that her railway always got the train there, no matter what, there was a further round of shouting about blasted Open-Access Operators!

Like every other train that day, she was heavily laden with passengers, and the station staff had to guide everyone who wished to depart the train through a side gate on the platform end as the stationmaster stomped up and down the platform, bellowing into his phone at someone.

This turned out to be most of the people on the train, and once the stationmaster calmed down a little, he addressed the multiple unit and her driver. “Alright, here’s the skinny - you go over that bridge, there ain’t a promise you’re coming back over any time soon. The whole Island is locking down tonight. Unless you can get there and back in the next thirty minutes, you’re up without a paddle.”

“Well I suppose there’s nothing else for it,” The 170 said, her weak voice surprisingly steely.

“Yeah.” Said her driver.

“We’re going over.” | “We’re dumping them here.”

“WHAT?”

Man and DMU stared at each other for a moment, and then there was more shouting and arguing, this time about cowardice and stupidity. It went on for some time, until eventually the DMU had tears at the corners of her eyes, and the driver was storming off down the station road in search of alternative transport back home.

Bloomer looked at the little multiple unit with newfound respect. “That took some nerve. Good lass.”

“Thanks.” She sniffed weakly. “I can’t just leave - what would that make me?”

“A Bad Engine.” The coaches and cranes, and P-Way equipment said firmly. Bloomer and the station staff still on the platform looked at each other for a moment at that, suddenly confident that wherever this unit ended up getting stored until she could be sent back, she would be well cared for.

The last passenger - a man on crutches - was escorted out of the station on an electric cart, and with that the station doors were securely locked. A spare driver had been part of the station staff, and he hopped into the DMU, taking her across the bridge just before the clock tower tolled 2:30.

“Hopefully this all blows over!” She called to Bloomer as she receded into the distance.

“I can only hope…” Bloomer said as his odd train set off for its last stop.

There was a single Motorail wagon left on the platforms. He was an older flat wagon, with Whitewall stenciled on his front end. The electric cart from the station bounced across the staff crossings with a porter at the wheel, and its charger cable bouncing around in the cargo tray. It joined a Mercedes Unimog lettered for the P-Way gang, the stationmaster’s personal car, a huge porter’s trolley the size of a Mini, and a few motorbikes and bicycles belonging to the station staff on the back of the wagon. Staff jumped out of the coaches and quickly strapped down the cart and went around checking the other straps. A few of the Motorail staff came over and boarded the train as well, while one man (who shouted that he lived in Barrow when asked why he wasn’t boarding) locked up the station and dragged a gate across the automobile entrance before walking off towards the city bus stop on the corner.

The stationmaster got out of his seat in Maribel, and marched forward to take a spot in Bloomer’s cab. “Go forward nice and slow. We’re stopping once we clear the switch.”

“Sorry?”

“Just a few more people.”

Orders now given, Bloomer and Jebediah slowly pulled and pushed the train out of the motorail siding and onto the main line. Once Whitewall had cleared the switches, they clunked into place, and Bloomer and the rest of the train watched in astonishment as every signal in the yard and the main line dropped to red. Soon thereafter, the signalbox door opened, and the signalman came out, a bag over his shoulder and his face hidden behind a paper mask. He turned off the lights in the box and locked the door, before coming up to Bloomer. “You’re the only train for two miles. Treat everything between here and the bridge as green.”

For effect, he unfurled a green flag, waved it, and then clambered onto the train, sitting as far away from everyone else as he possibly could in the crowded open air carriages.

Once again, Bloomer was struck with the sudden sensation that the world as he knew it was coming to an end. With a subdued whistle, he set off again, leaving Barrow-in-Furness station and yard as quiet and empty as a tomb.

The train slowly rolled over the bridge, and Bloomer gasped as he saw the difference between the island and the mainland. Sodor was quiet, the streets of Vicarstown still except for a bus and a police car driving along the waterfront. A few people with cameras were in the park by the station, photographing his approach.

Barrow was alive and noisy. Traffic rumbled and roared, the sound of people talking and chatting from bus stations and bike baths was audible even over his own chuffing. In the distance, the Jubilee Bridge was choked with traffic - police cars on the Sodor side of the bridge were stopping each car, and forcing most to turn around and leave. Those allowed through the bridge were almost all cars with license plates from Sodor or the Isle of Man - any one without had a large sticker applied to the back, although what it meant wasn’t immediately obvious. As the train went by, a flurry of radio calls, some of which were audible on the cab radio - meaning the railway’s dispatch was involved to some degree - went through. On the road bridge, the police began waving through what traffic there was - it seemed like most, if not all of the Sodor-plated automobiles had gotten through already - and then made some kind of waving motion to the bridge operator. Red lights began to flash, and the road bridge began to raise, cutting off Sodor’s road network from the mainland.

Meanwhile on the railway bridge, a man stood aside the tracks, a yellow flag in his hand. It was the bridge operator, and he hopped onto the footplate as Bloomer steamed by, a bag in his hand.

“Thanks.” was all he said, and Bloomer had another pit-of-his-firebox moment as he realized that he had been out of the loop, somewhat badly.

The bridge control cabin was on the mainland side of the bridge, but there was a small emergency panel on the Sodor side. The driver applied the brakes, but didn’t stop, as the train drove by the small electrical box. The bridge operator jumped down, ran to the box, wrenched it open, and in one smooth motion jammed a key into it, turned it, and pushed a yellow and black striped button, before removing the key and slamming the box closed. He was so quick that he was able to clamber onto Jebiediah’s cab steps as the diesel crane rolled by.

Behind him, a klaxon sounded in the distant bridge cabin, and an automated gate closed over the tracks. A pair of massive locks proceeded to open, and with slow mechanical precision, the Walney Channel railway bridge began to cycle open, severing the last link between the mainland and the Island of Sodor.

Bloomer, pulling what the media would later refer to as “The Last Train,” felt a chill go down his boiler as the massive bridge span locked into the upright position. The world has just changed, He thought. And it won’t be for the better.

------

A few days later, as the Virus hit the mainland in force through packed Chunnel trains and repatriation flights, and as the first few cases sprung up inside the Island’s hospitals, Bloomer knew he was right.

youtube

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

Yes! To all of those

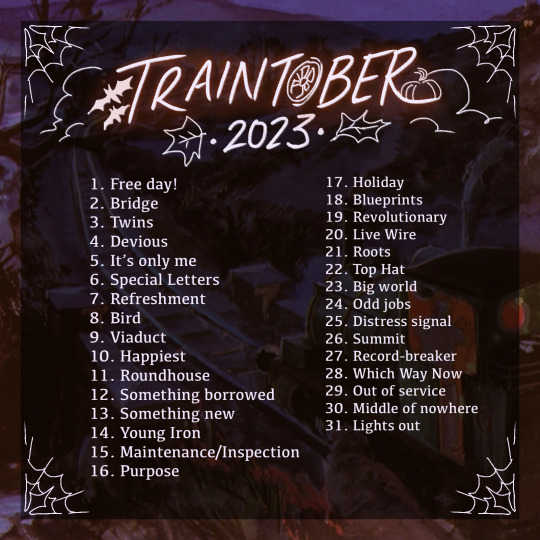

Scotty and Dennis (Pendennis Castle) painted Australia red with their "longest thousand miles", (which lasted considerably longer than that distance) and made friends and "friends" up and down Australia.

Not a steam engine alive during that time period (and quite a few diesels and electrics too!) doesn't have at least one story of the "world's longest lads trip" as it roared across the continent.

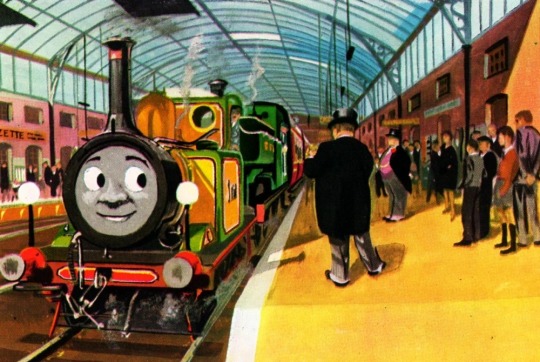

Pictured: Two lads in search of a good time

Ships for Flying Scotsman?

I really never think about Flying Scotsman tbh

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

"Because they make me laugh" is the best compliment I could ever receive.

Ships for Flying Scotsman?

I really never think about Flying Scotsman tbh

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

"Look, I'm a streamliner!"

"No, you're just annoying."

"Is somebody mad that they can't run off the trolley wires?"

"Shut the [horn honk] up."

For Silver and Black, any headcanons about the other engines at the IRM? I wonder if Pilot, 1630, and the electroliner get along since they’re the ‘faces’ of the museum. There’s also that Q Hudson, 504, 9925 and 9976. They probably all hang out as the Q club lol. I wonder if they like the BN units?

The IRM is practically a chronic and compulsive character designer's dream. I could spend the rest of my life making little guys out of their roster and probably not ever get bored, so you can bet DJ (@greatwesternway) and I have spent the past 13 months doing exactly that lol.

1630 was absolutely one of the first ones we worked on after Pilot, given that she's so iconic and important to the IRM. Engines with stories are far and away the easiest to write for, and 1630 has a great one. Plus, she's a face as you say! I like to characterize her as a bold and confident problem solver, especially having read some of the old Rail & Wires from the time period when she was undergoing restoration. Her first trial run went so well they had her pulling trains even though she was supposed to just be fired for testing, and that to me informs so much of her personality. She was ready to work from the jump! She's obviously besties with Shay 5, being that they've worked together for so many years, and I like to think they're sort of the de facto ambassadors for the steam department with the rest of the museum.

The Electroliner, I'm a little embarrassed to say, I only got around to learning about recently even though I was struck immediately by the design. I like to picture her as a more blue-collar version of the Zephyrs, streamlined and modern but still very much of the people. I haven't explored her history that much since we haven't gotten there in the letters yet, but I'm excited to learn more! I think she and Pilot get along really well, but that's sort of a given since Pilot gets along with everybody.

Some other characters at the IRM that get some play in the discussion are The Goddesses, who all have unique personalities and have been cropping up more frequently in the letters. We've also casually written some thoughts down about the other Pullman streamlined cars (Birmingham and Loch Sloy) as well as quite a few of the diesel shunters, since they're literally always out doing stuff at the IRM, and it's easy to fall in love with the engines that are constantly out there working. Our favorite so far is the Commonwealth Edison 15 shunter because he's grey and the last time I saw it out, it was switching the aforementioned Pullman cars around and @joezworld joked that he was going, "Look! I'm a streamliner!" and that has since become basically canon.

I don't have much for the Q steam engines although they're definitely on the list. I'm very interested in the BNs 1, 2, and 3 because I think their story is going to be interesting but I also haven't put much time in on their history yet. Since the museum's roster is so extensive (especially compared to the MSI), we've just been letting the stories inspire us as we learn about them organically. DJ's been adding new entries to the timeline from the IRM's photohistory book, and that alone has sewn some ideas we're definitely going to revisit later, if not in the letters than possibly in some other stories or just for our own amusement.

These questions are *so* good by the way, I'm absolutely loving being able to answer these! Thanks so much!

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey I did a thing for the first time in fucking forever. It's on A03 because something that long on Tumblr is not great for reading.

Remember how I said I don't do humanizations? Yeah I still don't but @littlewestern and @greatwesternway have done some work that really sticks in my head so now it's all your problems.

Shockingly this is my first fic on A03 so if the formatting is messed up blame that.

This took way too long and I have vanishingly little free time or brain power so I don't know when the next thing is gonna come out.

I might start migrating stuff over to A03 as a backup for Tumblr so keep an eye out.

#sentient vehicle headcanon#sentient vehicles#real trains#sentient trains#sentient planes#planes#aircraft#original fiction

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

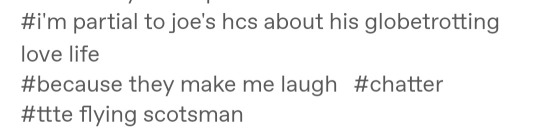

Traintober day 25

Hey guys,

I know I said I wasn't going to really participate in this year's traintober, but I ended up writing something over the last few weeks and figured I'd post it here. I'm a freelance contributor to Trains.com, the web arm of Trains Magazine, (you can read my IRL work here) and I wrote this for that. However, they have a maximum of about 4,000 words for print and 600-1,000 words for web, and this is past 7,000. So even if it makes it into print, it's not going to in its original form. So I'm giving it to you guys. Everything you're about to read is real. There's even an NTSB report on it.

Negligence and Gravity: The Story of a Train Wreck

Prologue

November 17, 1980

Cima, California - a barely inhabited place on a barely used road. A one horse town where the horse had run off. It sits at the intersection of two empty roads, with nothing to show for it but a general store-slash-post office. A true speck on the map, it likely would have been abandoned long ago had it not been for the presence of the Union Pacific Railroad, which sent dozens of trains each day past the ramshackle post office. Many trains rolled right on by, but more and more stopped, checking their brakes, cooling their wheels, or manually setting air brake retainers on each car of their trains.

They did so with good reason; stretching out beyond the post office towards the west, and paralleling the only main road, was a railroad line some twenty miles long. Part of the UP California subdivision that stretches from Las Vegas to Yermo, and then on to Los Angeles, it descends two thousand and six feet between Cima and Kelso, another barely-there town in the California desert. It was and still is one of the steepest portions of the Union Pacific system - accounting for curves and uneven geography, the UP considered the line to be a sustained 2.20% gradient. Any train that exceeded certain weight, braking force, or locomotive limitations was required to stop at Cima, and manually set brake retainers, before continuing down the hill.

As the clock ticked towards 1:50 in the afternoon, three trains entered this tale much like characters in a Shakespearean tragedy.

On the southern passing track is a long grain train, Extra 3135 West. 73 hoppers trail behind a lashup of SD40s, with dash-2 model 3135 on point. The air above the locomotives shimmers and ripples as heat from the motors, exhaust vents, and dynamic brake blisters radiates off into the mild November air.

In the center, a van train rolls past. The train, officially known as both 2-VAN-16 and Extra 8044 West, slows but doesn’t stop as it reaches the summit. Union Pacific has deemed this train capable of descending the grade with no extra precaution, and with good reason. Five locomotives are leashed to the front of this 49 car merchandise train, four SD40-2s trailing behind UP 6946 - the youngest member of the road’s 47-strong class of beastly 6,600 horsepower DDA40Xs. It’s an 8-axle titan in its last months of regular operation, with almost two million miles under its belt. The hot air from Extra 3135 mixes and whirls with the exhaust from the van train as it rolls by, the slab sides of the hoppers amplifying the bangs and squeals from 49 autoracks and piggyback flats. The noise increases as the train nears the end of the yard, the dynamic brakes already coming online as the train crests the summit. The engineer gives a blast from the horn as he passes the head end of the stopped trains, and then the van train is on its way down the hill. The caboose clears the track circuit at the far end of the passing sidings, and recedes into the distance. Within a few minutes the train is a distant shimmer as it snakes its way down the hill, an 8 million dollar steel serpent, bound for the hustle and bustle of Los Angeles.

Finally, there is the train on the northern passing siding. Extra 3119 West is not like the other two - there aren’t four or five locomotives hitched to a gargantuan train, one that stretches into the distance for a thousand feet or more. Instead, there’s a short consist of twenty cars, sandwiched between a single locomotive and a caboose. The cars are piled high with crossties, almost 11,000 of them, urgently needed by a tie gang at Yermo. So urgently, in fact, that if it hadn’t needed to stop and pin down its brakes, this lowly work train would’ve been rolling down the hill ahead of the high-priority van train.

Extra 3119 West, headed by the SD40 of the same number, has been in Cima for just under half an hour. In that time the crew had applied all the brake retainers, checked for defects, and otherwise readied their train for the descent into Kelso. Stopping meant that they’d be following the van train the whole way down, and so once the van train had gotten sufficiently small in the distance, the radio crackles. It’s dispatch, asking quite insistently if they were ready to go. They were, the engineer replies, and without any more to-do, the switch clunks into place, and the signal goes green. A double blast on the horn heralds the train’s departure, followed by the quiet squeal of brake shoes on steel wheels. There is no increased engine noise from the dynamic brakes. The train slips onto the main line, speed increasing slowly. By the time the caboose enters the main line, things are already going disastrously wrong.

Shortly thereafter, Extra 3135 powers up its train and descends the hill in a much more controlled fashion. Silence falls over Cima.

-

Negligence

November 13, 1980

The tale of negligence started three days earlier, at the Union Pacific tie plant in The Dalles, Oregon. Nestled in the valley of the Columbia River, The Dalles is nowadays best known for being the site of the worst bioterrorism attack in the United States, when members of the Rajneeshee religious organization poisoned several local restaurants with Salmonella in an attempt to influence local election turnout. However, that event is still four years into the future at this point, and the big news items in town are the May renumbering of Interstate 80N to I-84, and the March eruption of Mount St. Helens, some 65 miles away.

The Union Pacific tie plant, located between the west side of town and the newly-renumbered I-84, received an urgent order: 20 cars of 9-foot ties, urgently needed in Yermo, California. A mechanized tie gang working in the high desert is running low. Any delay will mean millions of dollars in wasted man-hours. The ties, estimated to number between 10 and 11 thousand, were hurriedly loaded into a series of F-70-1 bulkhead flatcars, modified for crosstie carriage with the addition of steel stakes down each side to prevent shifting. In addition to the 20 cars for Yermo, another group of 5 F-70-1s were being loaded with lighter 8-foot yard ties for renewal elsewhere on the California Subdivision. Inside the plant office, waybills for the 25 cars are being filled out, by hand. One of the most routine and mundane portions of loading railcars, the staff at the tie plant had made strides to simplify their workload; each waybill had been pre-filled with a seemingly appropriate weight figure: “about 60,000 pounds,” done in neat typewritten letters. This saved time, as it meant that tie cars didn’t have to be weighed, and exact quantities of loaded ties did not have to be known. Simple addition of this number to the known light weight of an F-70-1 flatcar (80,000 pounds), gave an estimated weight of 140,000 pounds per car. To the staff of the tie plant, complacent and ignorant, this seemed reasonable. They couldn’t know, because they didn’t want to, that the average per car weight of the 20 cars for Yermo was over 200,000 pounds.

-

November 17, 1980

“Urgent” might have been an understatement, when describing the journey these cars took. It took three days for the 25 flatbeds and their thousands of crossties to travel 1,260 miles across the Union Pacific system. They rolled into Las Vegas just before 1 AM on a manifest train; somehow, despite leaving The Dalles as a single block, a car containing beer had been inserted into the middle, with fifteen cars on one side and ten on the other. The how and why did not matter to the Las Vegas yard crews, who had been informed of the expedited nature of this train. Within minutes, the 26 cars had been taken off the manifest and were being shoved against a caboose that was already waiting. A third shift yard crew made quick work of the beer car and the five cars containing yard ties, but “disaster” struck when it was discovered that the caboose’s electrical system was non-functional. Somehow, despite having a major rail yard at their disposal, no other caboose could be found, and the issue could not be remedied. UP regulations forbade trains from running without rear lights between sundown and sun-up, so the highly expedited train was suddenly forced to cool its heels in the yard until lighting conditions improved.

With the delay, the new crew was scheduled to go on-duty at 8:05 AM, but just twenty minutes before, at 7:45, the Terminal Superintendent was informed that actually, the third shift crew had accidentally cut out the wrong cars - five cars of the 9-foot ties, not the five cars of 8-foot ties - and Extra 3119 West was about to set off with the wrong load. He responded with the unbelievable phrase of “Ties are ties”, and refused to have the incorrect cars set out, before reversing his decision some minutes later. While no other quotes are attributed to him in the subsequent NTSB report, his insistence on having the nearest yard crew drop what they were doing and fix the issue while he personally inspected the re-switching of the train speaks volumes on his mood at the time.

Not that he was of any help. During this frenzied switching, one car of 8-foot ties remained in the train. Its number - UP 913035 - was confused with another flatcar in the train - UP 913015. While minor in the overall sense, this slip-up shows exactly how quickly Las Vegas yard was working to get Extra 3119 West to its destination. When the train was finally ready, there were 19 cars of 9-foot ties behind locomotive 3119, and one car of 8-foot ties. As a car inspector was found, the final lading documents and waybills were presented to the engineer and conductor. Based on the flawed math of the tie plant, the train should have weighed 1,421.25 tons, however the final waybill read 1,495 tons exactly. Aside from being incorrect even against the tie plant’s figures, this weight was exactly five tons less than an internal UP tonnage/horsepower ratio that would determine whether or not the train would have to stop at Cima to apply brake retainers - with a 3,000 HP SD40, the train could not exceed 1,500 tons without incurring serious delays.