Photo

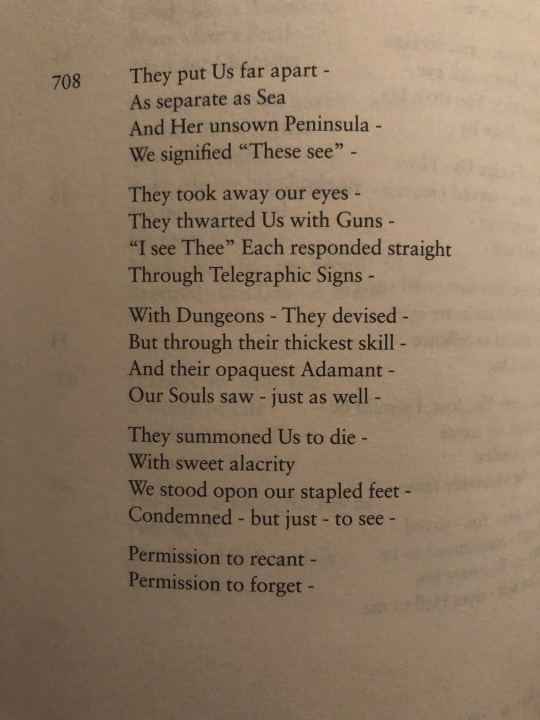

Emily Dickinson (1863), from The Poems of Emily Dickinson (Belknap, 1999)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weekend Reads—10 July 2020

Demi Moore’s bathroom really is quite … different, and welcome to The Immense Journey.

After a brief hiatus due to computer malfunction, I’m back. Check out some of my thoughts on alienation and ambivalence, illness as metaphor, and masks as metaphor that I’ve published since the previous Weekend Reads.

And, oh, how things have gone from bad to worse, especially in the United States, since last I surveyed the COVID-19 numbers.

Today, the World Health Organization reported 12,102,328 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 551,046 deaths. The United States, Brazil, and India recorded the largest rises in confirmed cases over the last seven days. Deaths were highest over the last week in Brazil, Mexico, and the US.

I won’t spend time analyzing the situation in the US. This evening’s Politico Nightly newsletter offers some insights on the virus, which is “raging out of control in regions across the country.”

As much as Trump’s popularity, particularly for his handling of the coronacrisis, is in decline, the mediocrity of Joe Biden is as sure as the sun rising in the east.

Amid an acute pandemic and the largest economic collapse since the Great Depression, the presumptive Democratic nominee told Ady Barkan, an advocate for Medicare for All living with ALS, that he remains committed to America’s for-profit model.

"It's no secret that I support Medicare for All," said Barkan, to which Biden interjected: "I don't."

Fortunately, I live in a non-competitive state, so I don’t have to bring myself to voting for Biden. My sympathy, though, for those of you who live in battleground states and have to drag yourselves to your polling place and cast a vote for him.

Just one reading recommendation to send you into the weekend.

Amia Srinivasan is among the two writers I’ve come to absolutely love in the past couple of months. (Here's the other.) She has a wonderful exploration in the London Review of Books of the use and meaning of pronouns. And she offers one of the best opening paragraphs I’ve read in quite a while:

I’ve had the wrong pronouns used for me – ‘he/him’ instead of ‘she/her’ – by two people, as far as I know. One of them was an editor at this paper, who I am told used to refer to me as ‘he’ when my pieces passed through the office. In his mind only men were philosophers. The other was Judith Butler. I had written a commentary on one of her books, and she wrote a reply to be published along with it. In the draft of her response, she referred to me by my surname and, once, as ‘he’. Just a few lines later she wrote: ‘It is surely important to refer to others in ways that they ask for. Learning the right pronoun ... [is] crucial as we seek to offer and gain recognition.’ I wrote her a meek email – this was, after all, Judith Butler – pointing out the error. She replied not twenty minutes later: ‘Sorry Amia! I always did have trouble with gender.’ Swoon.

Swoon, indeed. Read the full, 7,355-word piece here.

That’s it for this week.

Follow me on Twitter and sign up for my occasional newsletter (to be launched soon! Really.). And if you enjoyed it, consider forwarding this post to someone you know.

0 notes

Text

Finding Refuge in Alienation and Ambivalence

Perhaps it's due to the combination of the intensity of NYC's COVID-19 crisis in the spring and America's politics as usual—police killings, white supremacists, libertarian mask-rejectors, irate people throwing objects in retail spaces, mediocre Democrats, an approaching hurricane season amid persistent inaction on confronting the climate crisis, etc.—but I'm finding it difficult to get through Deaths of Despair. It's as though I've arrived at, for the first time, a previously untransgressed limit to my witnessing and consuming information about the utter depravity of America.

Since my late teens, I've been continuously engaged in political agitation of some sort or in journalism. This isn't new terrain for me. But whether it's the intensity of the past few months or the cumulative experience of a lifetime, the ugliness of American society, the vitality of resistance in the streets and organizing among those seeking a more-just world not withstanding, feels as if it’s becoming overwhelming.

As much as I'm acutely aware of the power of prose—it's why I became a writer, after all—it feels shallow to admit that a book, an academic one no less, is the red light flashing on and off signaling "change direction," which in this circumstance means turning to a Rachel Cusk novel about the much more comfortable themes to me of alienation and ambivalence toward the world.

I cannot recall ever averting my gaze from something or from feeling as though I wasn’t prepared to grapple with the sheer brutality of living in America. I avoided footage of Islamic State torture and killings, but watching those images in 2015, say, felt gratuitous rather than deeply affecting.

I can already hear the critique: privilege. Who does he think he is, in other words, expressing a hard limit on the emotional exposure to the cruel society that is so much crueler to other people than him and who cannot take a time out? That argument, though, only allows the most abused—and it could be only one person—to claim authenticity to feeling the blunt end of America’s brutality and raising their hand to say, “I’ve had enough.” It also ignores my own experiences, which I refuse to offer an account of in an effort to claim the right to take a break from Deaths of Despair—or despair in general. And, besides, my turn to Cusk will certainly not change in any way my material conditions. It allows me only brief emotional respite, which, I argue, is not an insignificant necessity to live.

What matters, after all, isn’t how high or low my threshold for consuming representations of American depravity may be, or whether I’ve stared down the barrel of a police officer’s gun or faced the humiliation of being laid off. What matters is the strength and sustainability of my commitment—the commitment from each of us for that matter—to changing the disparities in power between workers and bosses, members of society and the men and women with guns who police them without accountability, those in need of health care and those that profit from denying care, the refugee and the official who calls in the airstrikes.

And that commitment, at least for me at the moment, needs the girding of Cusk’s ambivalence about the world. Retreating into the comfort of quotidian alienation—and because it's autofiction, Cusk’s ambiguous genre form—means I can sustain the will to remain an anti-capitalist dissident in a very cruel America.

0 notes

Text

More on Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor—Liberal-Offender Edition

One final thought, at least for the foreseeable future, on Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor.

Her critique, or rather her effort at working “against interpretation” by not imbuing literature with meaning, but instead seeking to “deprive something of meaning,” yields some great insights on our contemporary coronacrisis.

Among the most easily discerned is Trump’s racism and xenophobia. Sontag, writing in the 1980s, highlights the long-standing practice of casting disease—syphilis, cholera, influenza, AIDS—as emanating from outsiders.

Sontag says:

One feature of the usual script for plague: the disease invariably comes from somewhere else. The names for syphilis, when it began its epidemic sweep through Europe in the last decade of the fifteenth century, are an exemplary illustration of the need to make a dreaded disease foreign. It was the “French pox” to the English, morbus Germanicus to the Parisians, the Naples sickness to the Florentines, the Chinese disease to the Japanese. But what may seem like a joke about the inevitability of chauvinism reveals a more important truth: that there is a link between imagining disease and imagining foreignness.

Trump tweeted 16 March:

“The United States will be powerfully supporting those industries, like Airlines and others, that are particularly affected by the Chinese Virus. We will be stronger than ever before!”

At his Tulsa rally on 20 June, Trump said:

By the way, it's a disease, without question, has more names than any other in history. I can name, kung flu, I can name, 19 different versions of names. Many call it a virus, which it is, many call it a flu, what difference, I think we have 19 or 20 versions of the name.

Sontag highlighted the tendency of European writers, mostly, through the ages to attribute illness to lesser, foreign people, which results in affliction in the enlightened, worthy members of a given society.

But not all metaphors are “equally unsavory or distorting,” she said. “The one I am most eager to see retired—more than ever since the emergence of AIDS—is the military metaphor. … It overmobilizes, it overdescribes, and it powerfully contributes to the excommunicating and stigmatizing of the ill.”

It’s worth recalling that there hasn’t been a war in modern history that liberals didn’t love. Vietnam. The Cold War. Iraq, round 1, 2, or the death brought about by Americans upon Iraqis in between. The former Yugoslavia. Syria. Yemen. Libya.

And, so, the war metaphor comes easily to liberals.

“When did America start losing its war against the coronavirus?” Paul Krugman began his 6 July NY Times op-ed.

“About that metaphor, the military one,” Sontag said. “I would say, if I may paraphrase Lucretius: Give it back to the war-makers.”

In America, though, it's difficult to find the peacemakers.

0 notes

Photo

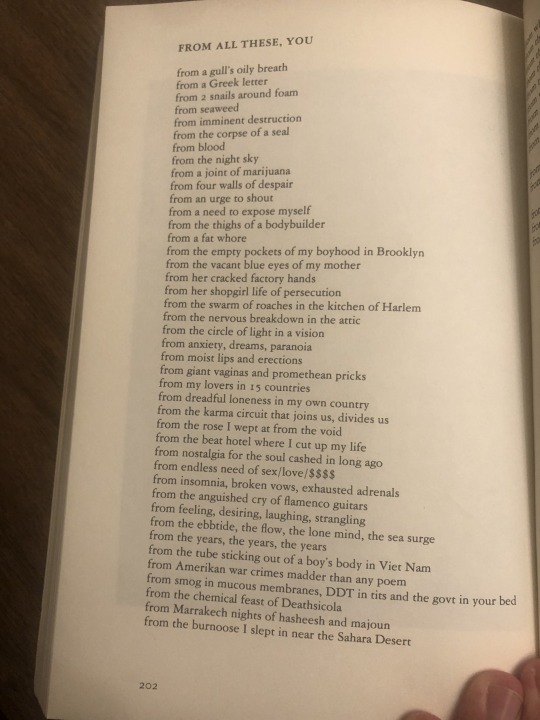

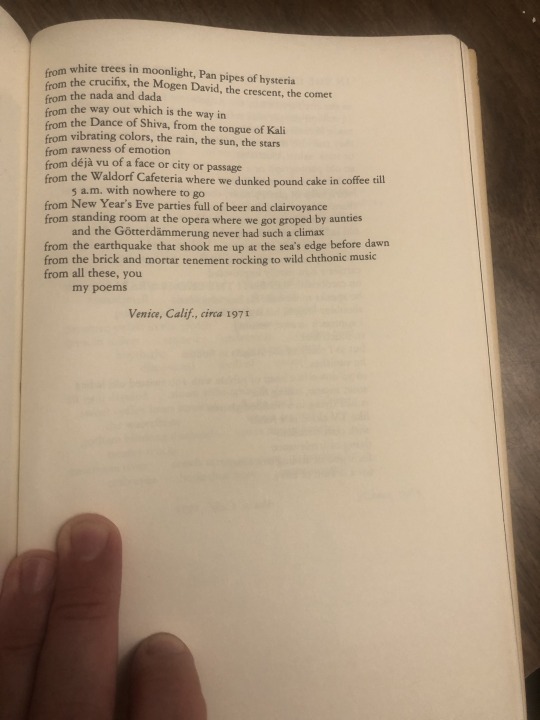

"From All These, You" by Harold Norse, from Carnivorous Saint (Gay Sunshine Press, 1977). Norse was born 6 July 1916. See more about his life and work here.

0 notes

Text

Masks as Metaphor

I began rereading recently Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor. I wondered what insights it might provide on representations of COVID-19. In case you’re unfamiliar, in it, Sontag looks at the ways in which tuberculosis and cancer were interpreted in literature and film through the ages. The book was published in the late 70s and updated in the 80s in the wake of a new illness that was frequently used metaphorically—AIDS.

I realized quickly that it’s probably too soon to look for metaphors in depictions of COVID-19. Perhaps more astute observers of American culture can find them.

But one metaphor has emerged that I think is worth noting—masks.

Wearing one and—more significantly, I think—not wearing one has quickly become a metaphor. Many people who refuse to wear one allege that they’re standing against tyranny, citing a tradition going back at least to America’s declaration of independence from England and running through anti-Communism, resistance to Obamacare, and embrace of conspiracy theories. While mask wearing is pretty ubiquitous from where I'm writing—Brooklyn, NY—and has become second nature for most people I know, refusing to wear a mask as taken on acute political urgency among libertarians, Trump supporters, conspiracy theorists, and some just-plain-old-selfish people.

The benefits of mask wearing are robust. I’m not going to argue for their usefulness here; that’s not my point.

Masks have clearly become a metaphor, though, for one’s notions of society, the individual, the role of government in peoples’ lives, masculinity, submissiveness and dominance, allegiance to Trump and freedom. The shadow that masks cast over our lives has quickly taken on significance akin to Sontag’s observations about tubercular coughs, contracting rectal cancer, or the supposedly immoral roots of AIDS transmission.

The mask, in other words, has become the Bolshevik in the bathroom. It’s become a not-so-secret handshake between minions of collectivism and their leaders on high. There’s plenty of anecdotal evidence. I can’t seem to get online these days without finding videos on Twitter or Facebook comments agonizing over the maskification of America.

There’s plenty of research that also bears out the mask as metaphor.

Psychologists at the University of Kent found last week that collectivists are “more likely to display adaptive responses during times of crisis.”

What’s to be done?

Julia Marcus argues for empathy for the men that won't wear masks. Some will never don a mask, she says, but some might. She points to condom distribution during the AIDS epidemic as evidence for the benefit of coaxing skeptics rather than shaming them.

Richard Kim disagrees. In an insightful Twitter thread, he argues that empathy helped, but so too did shaming.

A thread : More than anyone else, @JuliaLMarcus, writing in @TheAtlantic & drawing on her HIV work, has convincingly argued for a harm-reduction approach to coronavirus, quarantine and mask wearing. It's an extremely important intervention. But...

— Richard Kim (@RichardKimNYC) June 30, 2020

I interpret Bernie Sanders’s loss in the Democratic Party primary as being, in part, due to voter skepticism of his broad social platform—doubt born of America’s deeply entrenched notions of individualism, which have been reinforced and amplified by recent decades of neoliberal doctrine.

The UK researchers said their findings suggest that “promoting collectivism may be a way to increase engagement with efforts to reduce the spread of COVID‐19.”

It might also help puncture the metaphorical illness of American notions of individual liberty.

In the meantime, I, for one, am not against shaming. A few weeks ago, I was having drinks outside of a neighborhood bar. A pair of other patrons were lingering without masks. A front page photo from the NY Post etched into my consciousness, I confronted both. Both shrugged off my criticism, as did a few of their mask-wearing friends. One of the non-masked men accused me of “mask shaming.”

Guilty as charged.

Two nights ago, I saw that guy wearing a mask. I don’t claim responsibility, but I also don’t reject the notion that I helped promote a central, Sanders notion, a central collectivist notion: Not me, us.

Masks are metaphor. They’re also a crucial terrain of struggle.

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; } /* Add your own Mailchimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block. We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */

Subscribe to The Immense Journey

0 notes

Text

Weekend Reads—13 June 2020

The number of COVID-19 cases worldwide, according to the Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University, is, at publication time, 7,669,872. That’s up from 6,112,902 two weeks ago and 4,658,651 three weeks ago. Deaths number 426,185, which is up from 370,416 two weeks ago and 338,762 three weeks ago.

Florida and Texas reported this week record daily highs in new cases.

Trump cancelled yesterday a campaign rally planned for June 19 in Tulsa, Oklahoma, saying it was out of respect for Juneteenth, the annual commemoration of the end of slavery in the United States.

If you believe that, I’ve got a Nascar driver you should put some money on.

Trump’s concern about rising COVID-19 numbers in the state—and in Tulsa County, specifically—might have more to do with the cancellation. After all, before the rally was cancelled, attendees were required to sign a waiver acknowledging that the campaign was not liable if attendees contracted COVID-19.

Trump’s popularity is falling, while support for Black Lives Matter is ascendant. Support for burning down police stations is also high.

America surprises me sometimes, but I’m still going to move to Sweden. Welcome to the Immense Journey.

Just one recommendation this week.

Princeton historian Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, in “How Do We Change America?,” argues that the current uprisings across the country emerged from a half-century of growing resentment at increasing investment in cops under both Republican and Democratic administrations—with the presumptive Democratic Party nominee for president playing a starring role.

Taylor sees the ascendency of a new iteration of the Black Lives Matter movement, combined with growing precarity and frustration among young Whites, particularly, as a force that might, perhaps, achieve institutional change, such as defunding the police or eliminating cops altogether.

I thought Taylor provided an informative dose of history, while offering some insightful comments on where Left political struggle sits today. Check it out.

Follow me on Twitter and sign up for my occasional newsletter. And if you enjoyed it, consider forwarding this post to someone you know.

0 notes

Text

Dream Poem Erasure: 12 June 2020

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Surprising Sources of Optimism

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, in her essay "How Do We Change America?," says:

The protests are building on the incredible groundwork of a previous iteration of the Black Lives Matter movement. Today, young white people are compelled to protest not only because of their anxieties about the instability of this country and their compromised futures in it but also because of a revulsion against white supremacy and the rot of racism. Their outlooks have been shaped during the past several years by the anti-racist politics of the B.L.M. movement, which move beyond seeing racism as interpersonal or attitudinal, to understanding that it is deeply rooted in the country’s institutions and organizations.

The protests I've attended in Brooklyn have remained laser-focused on the police killings of Blacks in America, particularly of George Floyd, but also Breonna Taylor and Eric Garner, as well as Ahmaud Arbery, who was hunted down and killed while jogging in Georgia by white gunmen.

I grew up, though, in a quasi-rural, quasi-suburban county north of Philadelphia. When I took the school bus in the morning, I would join children whose parents worked in factories that manufactured automobile parts. But there were also kids who lived on working farms. The region had yet to be overrun with the low-quality, over-priced housing developments that have blanketed the previously tranquil landscape.

I don't recall demonstrations ever occurring, whether during economic recessions or following the dozens of military strikes or invasions the United States has carried out in the last 40 years. I recall some picket lines, but there most definitely weren’t protests defending Black lives and against police violence. It was a place that was more than happy to accommodate racism and subordinate itself to authority, no matter how unjust.

Yet in the past week, at least three demonstrations, in Landsdale, Souderton, and Perkasie, took place in the wake of George Floyd’s killing. And more protests are planned. The shift appears to be a phenomenon across America, where protests are occurring in unanticipated places. The area is less white than it once was, but that doesn't explain the sheer number of people and the diversity.

What’s different? I suspect the combination, like Taylor suggests, of deeply felt anxieties across a wide segment of the population—particularly among the young people that made up the overwhelming ranks of the demonstrators—and outrage at the racial violence bound up in America’s institutions.

The combination could prove to be a very potent mix that brings about transformative change and, unlike past iterations, resists co-optation by centrist Democrats and the nonprofit industrial complex.

I adhere to a pessimism of the intellect.* But if outraged people in Bucks and Montgomery County, Pennsylvania are taking to the streets, I'll allow myself a dose of optimism.

(It's late, and the cliché-alert tool is broken on my computer. So please, dear, observant reader, allow me this transgression.)

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; } /* Add your own Mailchimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block. We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */

Subscribe to The Immense Journey

0 notes

Text

Emily Dickinson (1862), from The Poems of Emily Dickinson (Belknap, 1999)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Vulnerability of Seemingly Unassailable Logic

During the COVID-19 shutdown I took to taking evening walks around Prospect Park to somehow make up for the exercise and mental respite that swimming once provided. The city’s recreation centers, where I’ve tended to swim, have been closed, so I do my laps, so to speak, through the Long Meadow, around Quaker Hill, across Nethermead, Midwood, and Sullivan Hill.

I’ve tried during these strolls to pay closer attention to the flora and fauna of the park—its richness of birds, especially—as well as appreciate the quietude that has emerged in the wake of drastically fewer vehicles on the road and people out and about, although the warming weather, falling number of COVID-19 cases, and loosening of restrictions are slowly, but noticeably, cancelling out the tranquility.

Sometimes, though, the quiet bores me. So I listen to podcasts, the London Review of Books among them. University of Oxford geographer Danny Dorling appeared in a recent episode, commenting, within a broader discussion about notions of wellbeing and happiness, on what might explain resistance to social distancing, mask-wearing, closures of public institutions and businesses.

Speaking at the outset in the voice of an archetypal opponent to government intervention, Dorling says:

[W]orrying about the wellbeing and the happiness of people is the beginnings of the root of damnation. We’ll become a weak country. You need the cold showers. You need the early morning runs.

…

And this soft, lily-liver stuff about worrying about people’s well-being is not the right way, and I think you can begin to look at this and say: It’s not your fault you believe that. You grew up in a country which had a particularly empire-mentality which could only produce people who could go out and be colonial officers if we dehumanize them enough to be able to send them out and behave that way.

The nation, in other words, demands personal sacrifice from its citizens. The workers in the meatpacking plants die for their country. The EMTs and doctors in the hospitals die for their country. The nail salons and barbershops must remain open—for the nation—and nevermind the number of sick or the lives lost. It’s a death cult.

“But that time has come to an end,” Dorling says. “We no longer have an empire; we no longer need quite so brutal and uncaring a set of men. And it’s particular men that have those particular attitudes.”

Dorling, I believe, is not saying the “brutal and uncaring” outlook was ever legitimate; rather he’s arguing that even on its own terms it doesn’t make sense anymore. Its logic, however, endures, and that's an obstacle that society needs to overcome.

And, oh, how quickly unassailable logic seems to be called into question. The COVID-19 crisis exposed the damage wrought by decades of austerity—in Dorling's UK and here in the United States. Political movements provided foreshadowing. But the failures of the status quo are hard to ignore.

In the US, a Democratic and Republican consensus over the last several decades has enabled enormous growth in police budgets while other public services—education, health, environmental protections, housing—wither on the vine. The killing of George Floyd last month by Minneapolis police has triggered a popular rethinking of what constitutes public safety—often narrowly viewed as a matter for the cops.

Although not without notable geographic variability, crime rates have fallen over the past quarter century, which is not to suggest that high crime rates are best addressed by ballooning police budgets. But even on its own terms, America's emphasis on policing doesn't make sense. Its time has come to an end.

Its time won't come soon enough.

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; } /* Add your own Mailchimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block. We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */

Subscribe to The Immense Journey

0 notes

Text

“Epitaph on a Tyrant” by W.H. Auden (Vintage, 2007)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weekend Reads—Late-Sunday, Police-Violence Edition—31 May 2020

To paraphrase Jelani Cobb, you know some extraordinary history is unfolding when something that happened in Minneapolis triggers protests and burning cars in … Salt Lake City, Utah.

Welcome to The Immense Journey.

I’ll return to the protests momentarily. But first, a quick rundown of the numbers.

The number of COVID-19 cases worldwide, according to the Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University, is, at publication time, 6,112,902, up from 5,240,905 a week ago and 4,658,651 the week before. Deaths number 370,416, which is up from 338,762 last week and 312,239 two weeks ago.

Because of highly variable rates of reporting on COVID-19 from place to place and uncertainty over whether deaths are properly attributed to COVID-19, comparing excess deaths this year compared to a historical average from previous years provides a potentially more accurate picture of the impacts of the epidemic.

The Financial Times provides some figures on excess deaths.

Let’s dig into the other pandemic killing people in America—police violence.

Alex Vitale, writing in the Guardian, points out that the police department in Minneapolis, where George Floyd was killed, has spent millions of dollars on reforms, including adopting body cameras, creating tighter use-of-force procedures, and trainings in de-escalation and mindfulness.

“None of it worked,” he says.

Vitale, echoing a growing demand among protesters, calls for defunding police departments. Cities are deploying cops for virtually any problem that arises in poor and working-class communities. It's enormously expensive, as well as frequently deadly. Thirty-percent of Minneapolis's city budget goes to the police. New York City spends $5 billion annually on policing. Instead, that money could address problems of public safety by providing investment in housing, employment, and healthcare.

Steven W. Thrasher, writing for Slate, provides a defense of property destruction, particularly of police precincts, which were torched in Minneapolis.

“You can agree with or disagree with the action,” he writes. “But you cannot deny that there is a logic in targeting a police station after the police have lynched a man in broad daylight, on video. It’s an attempt to create a different order in the society.”

And, like Vitale, Thrasher says defunding police departments, which serve to uphold a status-quo protecting the privileged and strangle civic life, will help to acheive that different order.

That’s it for this week.

Follow me on Twitter and sign up for my occasional newsletter. (To be launched soon! Really.) And if you enjoyed it, consider forwarding this post to someone you know.

Say his name. George Floyd!

0 notes

Text

Dream Poem Erasure: 28 May 2020

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Countdown

What will happen first: The lift-off of SpaceX's mission to the International Space Station or the US surpassing 100,000 COVID-19 deaths?

US COVID-19 deaths are currently, according to Johns Hopkins, 99,724. SpaceX liftoff is scheduled for 4:33 pm Eastern Time.

UPDATE 16:24h Eastern Time: SpaceX mission was scrubbed ~17 minutes prior to launch. The tally of COVID-19 deaths, however, continues to rise.

0 notes

Text

Weekend Reads—US Constitution Edition—23 May 2020

The number of COVID-19 cases worldwide, according to the Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University, is, at publication time, 5,240,905, up from 4,658,651 last week. Deaths number 338,762, an increase from 312,239 a week ago.

Because of highly variable rates of reporting on COVID-19 from place to place and uncertainty over whether deaths are properly attributed to COVID-19, comparing excess deaths this year compared to a historical average from previous years provides a potentially more accurate picture of the impacts of the epidemic.

The Financial Times provides some figures.

In an alternative universe, rather than the COVID-19 outbreak, we’d be discussing the Jia Tolentino controversy. If you know, you know, and this is The Immense Journey.

Let’s dig in.

Two recommendations this week, both on the topic of that horrid document the US Constitution. Citizens of some countries, France comes to mind, hold a certain pride in their nation’s capacity to toss tradition into the dustbin and rewrite their foundational documents.

Not the United States, where the Constitution would likely only be pulled from many people’s “cold, dead hands.”

Writing in the London Review of Books, Columbia University historian Eric Foner surveys two new books looking specifically at the Electoral College. It bears saying explicitly: Despite American hubris about the supremacy of its democracy, we do not elect our president by popular vote. Twice in recent history the top vote-getter did not win the election: Three million more people voted in 2016 for Hillary Clinton than Donald Trump and Al Gore received half a million more votes than George W. Bush in 2000.

The most common misconception is that the Electoral College—which, by the way, virtually no layperson can explain—protects the interests of small states. But, as Foner describes, the opposite is the case. Because of its winner-take-all quality, populous states become the object of candidates’ interests because winning them by even small margins yields a delegate bonanza. The result: US elections are determined by a handful of battleground states—Pennsylvania, Florida, Michigan, Arizona, North Carolina—while solidly blue or red states go uncontested.

“Rooted in distrust of ordinary citizens and, like so many other features of American life, in the institution of slavery,” Foner says, “the electoral college is a relic of a past the United States should have abandoned long ago.”

Over at The New Republic, Matt Ford takes a look at not only America’s anti-democratic method for selecting it’s federal executive, but also at the anti-majoritarian aspects of Congress, the Supreme Court, and the Bill of Rights.

“Past generations of Americans improved and repaired the Constitution by amending it piece by piece,” Ford says. “But there is no single reform that can cure what now ails the republic. What’s required instead is a top-to-bottom overhaul of our basic constitutional machinery: how our lawmakers are elected, how our presidents exercise their immense power, and how our judges and justices are placed upon our highest courts.”

That’s it for this week.

Follow me on Twitter and sign up for my newsletter. (To be launched soon! Really.) And if you enjoyed it, consider forwarding this post to someone you know.

Enjoy your weekend.

0 notes

Text

Exhilaration

Some days my words are too self-indulgent. They probably shouldn't see the light of day—today or maybe ever. At the very least, the lines of writing need to steep longer in the soupiness of thought, where more time in the cooker, so to speak, and some stirring of the pot might render flavor and texture worthwhile for consumption in the wider world. Today is one of those days when the words need to simmer.

I began this morning by writing about the exhilaration of the past couple of months. Challenging, economically and emotionally? Of course. Felt within the maw of widespread death and suffering? Yes, I’m fully aware. But even the most familiar vistas, literal or figurative, have been transformed. They bristle with consequence, with an intensity that I haven’t felt in years.

How to describe, though, the deeply felt, the raw, personal vitality of the moment, while being mindful of others’ loss, whether of income, or life, or flexibility in their day, which might now be severely constrained because of kids or illness or eviction?

Free of that self-consciousness, I wrote that these days are made for travelers—not simply those able to contend with the newness of a place but those who thrive within the mystery and unknown that unfolds over a path never before taken. Emily Dickinson captured it:

Exultation is the going

Of an inland soul to sea -

Past the Houses -

Past the Headlands -

Into deep Eternity -

Bred as we, among the mountains,

Can the sailor understand

The divine intoxication

Of the first league out from Land?

Yes, stepping from early March, when the first cases were reported in New York City, into April under stay-at-home orders felt like I was a land-bound person taking to sea for the first time. The parade of sirens and daily headlines about the epidemic cast a morbid shadow. January felt like a cul de sac, though, so I appreciated whatever steered me out of the suburbia of my soul. The first league out from Land was most definitely divine intoxication.

I empathize with the anxiety of those bristling at the closures and desperately grasping for a return to normal. What I’m feeling as exhilaration—the newfangledness, the uncertainty—sits, I suspect, like bricks on the minds and shoulders of many others. I’m not talking of the Koch-funded gun-nuts converging on state capitol buildings, demanding haircuts and the right to spread disease. I’m talking about the workers denied unemployment benefits, the parents working from home while caring for bored or curious children, those that feel the new, the unknown, as the precipice of potential demise. I feel exhilarated; I suspect they may not.

And in writing that paragraph, perhaps, I found a way out of my morning impasse, my self-indulgence. My exhilaration arises, in part, from my material conditions, which are relatively sound—I say relatively because I’m a writer, after all.

I can pay my rent and bills—for now. I can afford booze—for now—on the days when I need to take the edge off of my anxiety or to turn the volume up on these feelings of relative enchantment with the world. I may not have a long-term future—who does working in journalism—but for the moment, I’m not on the precipice of material neglect. I have the means and the mental bandwidth, in other words, to feel exhilarated.

An all-too-frequent misinterpretation of that very fine and often-cantankerous 19th-century visionary Karl Marx suggests that he was unconcerned with the needs and desires of the individual. It’s simply not true. He focused on the broad context of society in order to understand the conditions that constrain individuals and limit the possibility of achieving personal liberty.

“The human being,” he wrote, “is in the most literal sense a [political animal], not merely a gregarious animal, but an animal which can individuate itself only in the midst of society.”

Society shapes, constrains the individual. It can also set the conditions for individual flourishing. The realm of freedom comes, Marx described, when the realm of necessity and the mundane is left behind.

I’m hardly free of society’s material constraints—and I certainly have to navigate the mundane all too often. But I’m doing okay enough to feel some exhilaration.

So I've spent most of my day considering the need to destroy the impediments to achieving the divine intoxication described by Dickinson. Imagining a universal right to exhilaration still doesn't feel selfless enough.

Perhaps, though, the thoughts need more time to simmer.

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; } /* Add your own Mailchimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block. We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */

Subscribe

2 notes

·

View notes