#''wrote a poem. the poem was influenced by kalevala''

Text

A fantasy read-list: A-2

Fantasy read-list

Part A: Ancient fantasy

2) Mythological fantasy (other mythologies)

Beyond the Greco-Roman mythology, which remained the main source and main influence over European literature for millenia, two other main groups of myths had a huge influence over the later “fantasy” genres.

# On one side, the mythology of Northern Europe (Nordic/Scandinavian, Germanic, but also other ones such as Finnish). When it comes to Norse mythology, two works are the first names that pop-up: the Eddas. Compilations of old legends and mythical poems, they form the main sources of Norse myths. The oldest of the two is the Poetic Edda, or Elder Edda, an ancient compilation of Norse myths and legends in verse. The second Edda is the Prose Edda, so called because it was written in prose by the Icelandic scholar Snorri Sturluson (alternate names being Snorri’s Edda or the Younger Edda). Sorri Sturluson also wrote numerous other works of great importance, such as Heimskringla (a historical saga depicting the dynasties of Norse kings, starting with tales intermingled with Norse mythology, before growing increasingly “historically-accurate”) or the Ynglinga saga - some also attributed to him the Egil’s Saga.

Other “tales of the North” include, of course, Beowulf, one of the oldest English poems of history, and the most famous version of the old Germanic legend of the hero Beowulf ; the Germanic Völsunga saga and Nibelungenlied ; as well as the Kalevala - which is a bit late, I’ll admit, it was compiled in the 19th century, so it is from a very different time than the other works listed here, but it is the most complete and influential attempt at recreating the old Finnish mythology.

# On the other side, the Celtic mythologies. The two most famous are, of course, the Welsh and the Irish mythologies (the third main branch of Celtic religion, the Gaul mythology, was not recorded in texts).

For Welsh mythology, there is one work to go: the Mabinogion. It is one of the most complete collections of Welsh folktales and legends, and the earliest surviving Welsh prose stories - though a late record feeling the influence of Christianization over the late. It is also one of the earliest appearances of the figure of King Arthur, making it part of the “Matter of Britain”, we’ll talk about later.

For Irish mythology, we have much, MUCH more texts, but hopefully they were already sorted in “series” forming the various “cycles” of Irish mythologies. In order we have: The Mythological Cycle, or Cycle of the Gods. The Book of Invasions, the Battle of Moytura, the Children of Lir and the Wooing of Etain. The Ulster Cycle, mostly told through the epic The Cattle-Raid of Cooley. The Fianna Cycle, or Fenian Cycle, whose most important work would be Tales of the Elders of Ireland. And finally the Kings’ Cycle, with the famous trilogy of The Madness of Suibhne, The Feast of Dun na nGed, and The Battle of Mag Rath.

Another famous Irish tale not part of these old mythological cycles, but still defining the early/medieval Irish literature is The Voyage of Bran.

# While the trio of Greco-Roman, Nordic (Norse/Germanic) and Celtic mythologies were the most influential over the “fantasy literature” as a we know it today, other mythologies should be talked about - due to them either having temporary influences over the history of “supernatural literature” (such as through specific “fashions”), having smaller influences over fantasy works, or being used today to renew the fantasy genre.

The Vedas form the oldest religious texts of Hinduism, and the oldest texts of Sanskrit literature. They are the four sacred books of the early Hinduist religion: the Rigveda, the Yajurveda, the Samaveda and the Atharvaveda. What is very interesting is that the Vedas are tied to what is called the “Vedic Hinduism”, an ancient, old form of Hinduism, which was centered around a pantheon of deities not too dissimilar to the pantheons of the Greeks, Norse or Celts - the Vedas reflect the form of Hinduist religion and mythology that was still close to its “Indo-European” mythology roots, a “cousin religion” to those of European Antiquity. Afterward, there was a big change in Hinduism, leading to the rise of a new form of the religion (usually called Puranic if my memory serves me well), this time focused on the famous trinity of deities we know today: Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva.

The classic epics and supernatural novels of China have been a source of inspiration for more Asian-influenced fantasy genres. Heavily influenced and shaped by the various mythologies and religions co-existing in China, they include: the Epic of Darkness, the Investiture of the Gods, Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, or What the Master does not Speak of - as well as the most famous of them all, THE great epic of China, Journey to the West. If you want less fictionized, more ancient sources, of course the “Five Classics” of Confucianism should be talked about: Classic of Poetry, Book of Documents, Book of Rites, Book of Changes, as well as Spring and Autumn Annals (though the Classic of Poetry and Book of Documents would be the more interesting one, as they contain more mythological texts and subtones - the Book of Changes is about a divination system, the Book of Rites about religious rites and courtly customs, and the Annals is a historical record). And, of course, let’s not forget to mention the “Four Great Folktales” of China: the Legend of the White Snake, the Butterfly Lovers, the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl, as well as Lady Meng Jiang.

# As for Japanese mythology, there are three main sources of information that form the main corpus of legends and stories of Japan. The Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters), a chronicle in which numerous myths, legends and folktales are collected, and which is considered the oldest literary work of Japan ; the Nihon Shoki, which is one of the oldest chronicles of the history of Japan, and thus a mostly historical document, but which begins with the Japanese creation myths and several Japanese legends found or modified from the Kojiki ; and finally the Fudoki, which are a series of reports of the 8th century that collected the various oral traditions and local legends of each of the Japanese provinces.

# The Mesopotamian mythologies are another group not to be ignored, as they form the oldest piece of literature of history! The legends of Sumer, Akkadia and Babylon can be summed up in a handful of epics and sacred texts - the first of all epics!. You have the three “rival” creation myths: the Atra-Hasis epic for the Akkadians, the Eridu Genesis for the Sumerians and the Enuma Elish story for the Babylonians. And to these three creation myths you should had the two hero-epics of Mesopotamian literature: on one side the story of Adapa and the South Wind, on the other the one and only, most famous of all tales, the Epic of Gilgamesh.

# And of course, this read-list must include... The Bible. Beyond the numerous mythologies of Antiquity with their polytheistic pantheons and complex set of legends, there is one book that is at the root of the European imagination and has influenced so deeply European culture it is intertwined with it... The Bible. European literary works are imbued with Judeo-Christianity, and as such fantasy works are also deeply reflective of Judeo-Christian themes, legends, motifs and characters. So you have on one side the Ancient Testament, the part of the Bible that the Christians have in common with the Jews (though in Judaism the Ancient Testament is called the “Torah”) - the most famous and influential parts of the Ancient Testament/Torah being the first two books, Genesis (the creation myth) and Exodus (the legend of Moses). And on the other side you have the exclusively Christian part of the Bible, the New Testament - with its two most influential parts being the Gospels (the four canonical records of the life of Jesus, the Christ) and The Book of Revelation (the one people tend to know by its flashier name... The Apocalypse).

#read-list#fantasy#fantasy read-list#mythology#mythologies#celtic mythology#norse mythology#japanese mythology#chinese mythology#mesopotamian mythology#books#references#book references#sources

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

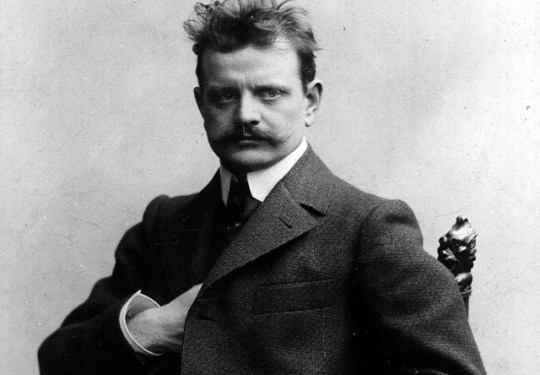

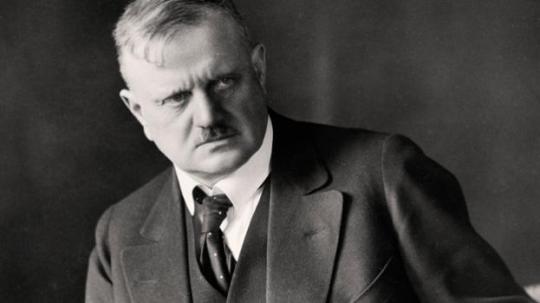

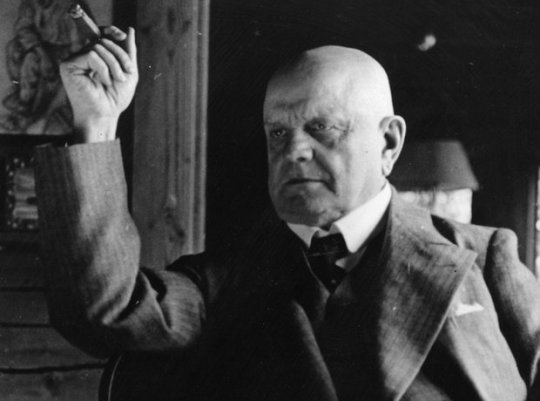

Jean SIBELIUS (1865-1957)

When the great Finnish composer Jean Sibelius met his Austrian contemporary Gustav Mahler in 1907, the two discussed symphonic form. Sibelius stated that what he admired most was the “profound logic” by which the symphony connected musical ideas. Mahler disagreed. The symphony, he insisted, must be like the world: “It must embrace everything”. Yet just as Mahler valued logic more than he cared to admit, Sibelius’s symphonies chart a very personal journey, and reflect an enduring love of nature. He called them “confessions of faith from the different stages of my life”.

[Yazının Türkçe çevirisi]

Sibelius was born to a cultivated, middle-class, Swedish-speaking family in a provincial garrison town. He only began to learn Finnish when his mother enrolled him at a Finnish-speaking grammar school - the country’s first - at the age of 11. He was soon enthralled by the Nordic poets Johan Runeberg and Viktor Rydberg’s stories from the national folk epic, the Kalevala. He also fell in love with the spacious Finnish landscape, with its seemingly endless forests and lakes.

He showed early promise as a composer and violinist. At the Helsinki Conservatory there was talk of him becoming a concert soloist. However, he suffered a crisis of confidence and abandoned the idea of a virtuoso career, not without lasting regret. Some of his later diary entries suggest that he saw composition as a second-best option. Even so, his development as a composer was impressive. While studying in Vienna he had the first ideas for what was to become his programmatic symphony Kullervo, based on a story from the Kalevala. Encounters with Finnish folk singing in its purest, most ancient “runic” form also had a galvanising effect.

The premiere of Kullervo in Helsinki in 1892 was a sensation. Sibelius was established overnight as a major cultural force in Finland. Sibelius’s musical contributions to a series of defiantly Finnish historical pageants elevated him to the status of national hero in a period when the Russian authorities were highly sensitive to nationalist stirrings. Another Kalevala-inspired work of the 1890s was the four-movement Lemminkäinen Suite, including the atmospheric “Swan of Tuonela”. The symphonic poem Finlandia (1899-1900) was so overt in its nationalist agenda that it was performed under a series of alias titles. Nonetheless, his name was now established internationally.

With his First Symphony (1899), Sibelius began to separate the symphony from the tone poem. From then on he refused to concede that his symphonies were “about” anything other than music. Still many heard the Second Symphony (1901-02) as a “symphony of liberation”, even though its slow movement had started life as a tone poem about Don Juan and Death. Commitment to “absolute music” came in his Third Symphony, completed in 1907. It was partly influenced by the concept of “Youthful Classicism” developed by his friend, the composer-pianist Feruccio Busoni. But something new was born here. In this symphony the finale doesn’t so much follow on from the scherzo as emerge from it.

The idea of seamless organic transition increasingly preoccupied Sibelius. In the Fifth Symphony (completed 1919) it is hard to say where the moderately paced first movement gives way to an accelerating scherzo. Sibelius wrote that he saw the symphony as a form “like a river”. In the first movement the experience is like slipping gradually from a steady current into white-water rapids.

The economy and discipline of Sibelius’s compositions were not matched in the man himself. Insecure and prone to extreme mood-swings, he became alarmingly dependent on alcohol. After an operation to remove a throat tumour in 1909 he managed to stay sober for a while. But the withdrawal symptoms were dreadful for him and his heroically devoted wife Aino. From this difficult period emerges one of his supreme masterpieces, the Fourth Symphony (1910-11). The need to come to terms with personal crisis pushed the composer to extend his stylistic resources. The harmonic language of the symphony is often very dissonant. And in the slow movement Sibelius effectively creates a new musical form: variation-like, but with a theme that grows from, and eventually collapses back into, a tiny motivic seed.

In the mid-1920s Sibelius produced three masterpieces in the forms he had made his own: theatre music for The Tempest, his Seventh Symphony and perhaps his greatest tone poem, Tapiola. Although he lived for another three decades, he never released another major work. It now seems more than likely that he finished an Eighth Symphony some time around 1930. If so, he destroyed it, possibly in the same bonfire on which he sacrificed several other significant scores.

It has been suggested that Aino’s efforts to curb Sibelius’s drinking eventually deprived him of the means to silence the harsh critic in his own head. Whatever the case, one of Sibelius’s daughters stated that once he stopped composing he became more at peace with himself. In any case we can be grateful that he left so much fine music, some of it, like the tone poem The Wood Nymph (1895), only recently rediscovered. Apart from the symphonies, tone poems and theatre scores, Sibelius composed a large number of beautiful and powerful songs, some of which exist in alternative versions with accompaniment for piano or orchestra.

In the years after World War Two, Sibelius was dismissed by many as a Romantic reactionary, clinging on to outmoded forms and harmonic language. But his popularity never dwindled in the concert hall. And in the late 1970s he also began to be seen as intellectually respectable once more. Sibelius’s exploratory, organic attitude to form and orchestral sound, and his complex “layered” musical textures have been an inspiration for many of today’s younger composers. This is important, but his enduring popularity owes at least as much to his powerful lyricism, rooted deep in his country’s musical soil.

source: Sinfini Music

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Magical summer: Väinämöinen

VÄINÄMÖINEN

Category: The Kalevala / Finnish mythology

“The Kalevala” is a great epic considered to be one of the greatest works of literature of Finland and its national epic, the very heart of its mythology. But it might surprise you to know that The Kalevala is actually not an ancient text, but a quite recent one: it was written in the 19th century by Elias Lönnrot. You see, Lönnrot was a folkloristic who kept collecting the folklore, tales and legends of both Finnish and Karelian culture. We are not quite well-informed about what Finnish mythology was originally, before Christianity came over and conquered the land, due to Finnish legends being mostly oral – with only pieces of texts, old fairytales and fragments of belief surviving to this point. There were several folklorists who worked hard to collect ancient tales and rebuild the old mythology, but Lönnrot went one step further. After collecting enough material, he decided to give Finland a great national epic, the same way the Greeks had Homer’s work or the Norse the Edda. So he recreated one great story from all the bits and pieces he had, and wrote this story in a total of 50 poems, gathered together as the “Kalevala”. It might be an artificial patchwork of legends and old tales with some inventions thrown in it (Lönnrot did place in his work his personal theories and invented some characters to fill the holes that he had discovered), but its impact on Finnish culture was HUGE. It is still to this day a work that all those that study Finnish mythology use as a reference ; it was the work that recreated a passion for the Old Finnish language and started movement that preserved the language as it was about to fade away ; it became part of what would later be Finland’s own national identity – and in a way it was said that this work moved so much the national spirit that it actually might have played a key part in how Finland finally got its independence as a country from Russia in 1917. And even beyond Finland, The Kalevala influenced many great authors and artists : J. R. R. Tolkien was greatly inspired by it, Michael Moorcock also used this work as an inspiration, and it was also one of the favorite works of none other than Don Rosa!

And the main character of The Kalevala is none other than Väinämöinen…

Väinämöinen is born from Ilmatar, a primordial female spirit that played a key part in the creation of the world. Descended from the air, Ilmatar went to the sea (because at the time there was only the air and the sea) and became pregnant from it, but she could not give birth and she had to wait in the waters for seven hundred and thirty years – until a duck laid eggs on the goddess’ knees, and she broke them, the shells becoming the earth and the sky, the whites the moon and the stars, the yolk the sun. Then, she could give birth to Väinämöinen, who was the first man, and swam to the land. (Well technically speaking, it was Väinämöinen that got tired of being in his mother’s womb and prayed to the celestial bodies to be released).

I am not going to cover the entirety of the Kalevala because it is an ENORMOUS work with a lot of things in it.

As I said, Väinämöinen is one of the main characters of the Kalevala, opening and closing the book and his adventures forming the bulk of it. He is a sort of demigod, born of a goddess with magical powers but still considered a man and human. He is usually depicted as an old man, because due to the very long pregnancy he was born already adult – not just adult, but also very wise, because staying for centuries in his mother’s womb caused him to learn all sorts of things, more than any regular man would know. He is remembered nowadays as a “sorcerer” or “wizard”, though it is incorrect. Väinämöinen is indeed a magic-user and spell-caster, but is true nature is between a “shamanic hero” (he is a man who happens to be in contact and good pal with numerous forces of nature, and his numerous journeys are typically shamanic in nature, he can talk to the trees or summon the gods) and the “eternal bard”. You see, Väinämöinen is primarily a story-teller and singer, always bringing with him his kantele, but this is precisely what makes him a “wizard”. In Finnish mythology, spells are actually songs, and magic is cast by telling stories. If you want for example to appease the sea or split it into two or anything like that, you have to sing the story of (for example) how the sea was created, or how the sea was tamed, and the magic will work. (In fact, in real-life there were “magic contests” between bards-sorcerers in Finland, where the contestants had to throw as much “spells” to each other as possible – in practice, each one had to tell and sing as many stories as they could remember, and the one with the most won. Magic is all a question of memorization, story-telling and good singing). And so Väinämöinen, simply by telling the story of how iron was born or how the first tree was cut, can have boats sail on their own without wind, entire kingdoms put to sleep, or dry out waterfalls.

Väinämöinen is a bringer of order over the chaos, who at the beginning of times worked actively with another mythological character, “Sampsa Pellervoinen, the architect of forests” to sow trees, help plant life grow and make the once-barren earth fertile. Väinämöinen is also a monster fighter : to create his kantele (the first in the world), he killed a gigantic pike, and to learn more spells he had to fight a giant that swallowed him whole (but he managed to escape by using harmful spells from inside the giants’ belly). “The Kalevala” gets its name from the main kingdom and country where the story takes place, the kingdom of Kalevala in which Väinämöinen lives (and that he helped create) – and many of the stories are about the tense and often warful relationships between Kalevala and its many male heroes, wizards and warriors, and the northern kingdom of Pohjola over which reigns the witch-queen Louhi, a rival and mirror image of Väinämöinen.

Originally the two weren’t truly enemies – in fact, in the beginning of the story Louhi rescued the eternal-bard from an angry and arrogant man who wanted to kill him; but in exchange she had him help her trick a mythical smith into creating the Sampo, a magical item of abundance (similar to the Cornucopia). This would prove a dreadful mistake, as the Sampo would become an object of war and desire between Pohjola and Kalevala, resulting in many battles between the two kingdoms until finally the object ends up destroyed by the feud. Louhi also gets into numerous conflicts with the Kalevala men because they keep falling in love with her daughters, and the possessive and greedy witch-queen keeps asking the suitors for impossible and deadly tasks – and Väinämöinen is one of the numerous suitors that tried to woo a daughter of Louhi.

It all culminates in one last attack: Louhi, enraged after the Sampo’s destruction during a war between her army and the Kalevala’s, ends up launching a massive magic attack on her rival kingdom. She sends all sorts of diseases, upon it (actually each disease a child of Loviatar, an evil goddess of death, decay and pestilence), but Väinämöinen heals them all ; she sends a gigantic destructive bear to kill all the cattle, but Väinämöinen appease it and tames it by singing his birth story and singing the peace and prosperity of his people ; and finally Louhi steals away the sun, the moon and the fire to plunge the world into darkness – but Väinämöinen recreates fire, and takes back the sun and the moon from Louhi – finally the witch-queen admits she is vanquished and lets Väinämöinen, with his songs of peace, prosperity, light, health and order, win over her own powers of greed, cold, darkness and disease.

However, despite being the main hero and protagonist, as well as a force of good, Väinämöinen is not actually a man without flaw, or a being of pure morality. He has various vices, and committed mistakes in his life – growing as foolish and arrogant as those he had to fight. And the end of the poem is also the end of the shamanic bard. In the last poem, Väinämöinen is asked to check on a mysterious and bizarre baby that was born when a maiden ate a talking cowberry. The child is to be baptized, but only if he is deemed “good” and “worthy” – the old bard-sorcerer examines it, and declares the child is wrong, unfit for anything, and should be put to death. But as soon as he says that, the baby starts speaking and declares that Väinämöinen is visibly a bad judge of character, and is now too foolish and rash in his decisions – and despite being just two weeks old, the babe starts listing all the past mistakes and sins of Väinämöinen, reminding him of all his crimes and shortcomings. He notably recalls one incident at the very beginning of the Kalevala: remember the arrogant young man that wanted to kill the bard? Originally the young man was just a rude and foolish boy who was envious of the old man’s power, but after being defeated by him in a contest he had to promise to give him his sister in marriage. Now the man’s sister did NOT want to marry Väinämöinen, and she made it quite clear – but despite her refusal, the wizard did not flinch and insist that she was to be his wife. Desperate, she decided to drown herself to escape the marriage – and as the baby points out, Väinämöinen could have used his powers to save her, or mercy to deliver her from her bonds, but he did nothing and let the maiden kill herself in the sea. This incident actually did haunt before Väinämöinen, as the maiden returned under the shape of a perch to haunt and taunt the sorcerer some times before – but hearing a baby (a thing still pure and innocent) remind him of that, and many other flaws… It is the end for Väinämöinen.

He realizes and accepts that he has been growing old, that his powers and hold on the land have been weakening, that he is not as wise, important and powerful as he used to be – he can be beaten by a mere baby, who turns out to be more intelligent and honorable than him! Filled with sadness and anger, Väinämöinen goes to the seashore and summons a magical boat of copper that will take him far, far away from the land of the humans: he will leave Finland, abandoning behind his kantele and his numerous songs and poems as a “gift” to the rest of humanity. His time has passed and he is retiring – but before leaving he makes one last prophecy/promise: that he will return when his craft and powers are the most needed, when the sun and moon will disappear from the sky and when the air shall contain no more joy.

- - -

The last part of the Kalevala is of course an attempt to show the arrival of Christianity in Finland replacing the old religion (Vainamoinen being chased away from Finland by a newly baptized baby). And the old shaman's promise to return is typical of the myth of the "returning king", a legend that has many variations but is most exemplified by the legend of King Arthur, the "king sleeping under hill" - according to which King Arthur is not dead but in an endless sleep somewhere under a hill, and when England will be in its most dire time and in great danger he will wake up and return to the world to save it.

Now this is the version of Väinämöinen in the Kalevala. However one thing Lönnrot did was remove all the divinity from him. You see, before the publication of the Kalevala and in most of the old folklore and texts we have... well Väinämöinen was a god. More precisely he was the god of songs and poetry, the bard-god. It notably explains why he has such enormous powers and why he is part of the myth of the creation of the world. But Lönntor didn't like the idea of Väinämöinen being a god, so he made him much more mortal and human like: he was convinced that he was a great hero or shaman that ended up being divinized through time, so for his "Kalevala" he decided to turn the "eternal bard" into a powerful demigod, a Finnish cross between Orpheus and Merlin.

44 notes

·

View notes